Abstract

In generative syntax, two major types of proposals – syntax-oriented and semantics-oriented proposals – have been used to examine adverbs and adverbials. Despite these proposals explaining the remarkable properties of adverb positioning, this class of words is heterogeneous and problematic in terms of their displacement. This study adopts scopal theories and proposes a partial semantic analysis using phases to describe adverbial positioning in Modern Standard Arabic. We argue that the semantic scope and the modification domain are the main determinants of adverbial position, which can best be analysed in terms of phases. In this regard, adverbials are classified into lower and higher adverbials. Lower adverbials have a narrow semantic scope and modification domain. They include subject-oriented and verb-oriented modifiers and freely adjoin the vP layer. Higher adverbials have a wider scope and modification domain. They include discourse-oriented modifiers and tend to attach to the Complementiser Phrase layer. In terms of their hierarchical order, discourse-oriented adverbials are higher than subject-oriented and verb-oriented modifiers in the articulated clause structure. This conclusion suggests that scopal theories along with language-specific rules may provide a unified generalization and straightforward account of the cross-linguistic distribution of adverbs and adverbials.

1 Introduction

There is an abundance of literature on the structure and semantic scope of adverbs in Germanic and Romance languages in the generative framework (Belletti 1990, 1994, Costa 2000, Cinque 1994, 1999, 2004, Ernst 1984, 1998, 2002, 2004, 2014, 2020, Jackendoff 1972, Pollock 1997, Travis 1988). Since Jackendoff (1972), the focus on the syntax and semantics of adverbs in the generative linguistics has increased. Jackendoff’s semantic or scopal approach laid the theoretical foundations for this field of study. His proposal was later extended by numerous scholars (cf. Ernst 2002, 2009, Frey and Pittner 1999, Haider 2000, 2004, amongst others). The main objective of this proposal was to correlate the semantic scope of adverbials with their syntactic positions. Thus, based on this assumption, Jackendoff (1972) divided adverbs in English into sentence-initial adverbs, sentence-final adverbs, and adverbs that are positioned between the subject and the main verb. A further cartographic approach or syntax-driven theory was introduced by Cinque (1999) to describe the distribution of adverbs based on their positions. This syntactic-driven approach was based on Kayne’s influential Linear Correspondence Axiom (LCA) and the Split Complementiser Phrase (CP) of Rizzi (1997). Similar proposals are also available in Alexiadou (1997, 2004), Laenzlinger (2004), and Haumann (2007). According to this influential approach, the hierarchy of adverbials is encoded by a universal hierarchy of functional heads, in which adverbials are designated as the specifiers of functional heads. Although other proposals are available (cf. Potsdam 1998, Costa 2004), these two are the standard ones used in this field, and they are further discussed below. Examining the data from Standard Arabic, this article extends the notion of phases as outlined in Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2008) and offers a phasal analysis to describe the distributional characteristics of adverbials. In this study, adverb refers to the lexical class, and adverbial to the functional class that modifies the predicate or the whole proposition.

The organization of this article is as follows. Section 2 gives an overview of the two most influential proposals adopted to account for the behaviour of adverbs, Section 3 outlines the underlying theoretical assumptions adopted in this article, Section 4 reviews existing studies on adverbs and adverbials in Arabic in general, Section 5 explains the methodology, Section 6 presents the analysis of adverbs and adverbials in Arabic, and Section 7 provides the concluding remarks.

2 Two major proposals

2.1 Syntax-driven approach

The feature-based approach, also known as the cartographic theory, as proposed by Cinque (1994), is essentially based on the works of Kayne (1994) and Rizzi (1997) and relies mostly on syntactic mechanisms. Kayne (1994), in his well-known LCA, argued that a linear representation is derived from a hierarchical representation via the asymmetric c-command relation (pp. 5–12). According to this proposal, the head can only take one specifier, while the adjunction is blocked or not allowed.

In relation, Cinque (1999) assumed a universal hierarchy of adverbs, which argues that adverbs have a fixed order as specifiers of functional heads (aspecto-temporal or modal) rather than adjuncts. This conclusion was based on data from various languages, including English, French, Hebrew, and Chinese. Adverbs, according to this proposal, are structurally classified into lower adverbs and higher adverbs. He further posited that lower adverbs appear in the lower parts of a sentence, usually in the position before the verb, whereas the higher adverbs appear in a higher position, close to the functional heads. Since auxiliaries can also have a rigid order, this cartographic approach expects a rigid order among adverbs and these auxiliaries in the canonical structure. To account for other surface orders, this approach adopts three types of movements (Ernst 2014). The first movement involves the movement of adverbs to sentence-initial positions, such as topic, focus, or other pragmatic-related processes. The second movement is the head movement. The third type of movement is more complex (roll-up movement, in Ernst’s term) to some extent, because it requires multiple movements to derive the surface structure of rigid orders. Therefore, the work of Cinque (1999) and relevant studies accounted for post-verbal adverbs. However, participant preposition phrases (PPs) are less clarified, although, in Cinque (2004) and Schweikert (2005), these participant PPs are treated as normal adverbs licensed by fixed functional heads in relation to particular adverbial meanings.

Cinque’s (1999, 2004) proposal is systematically tested against adverbs displacement in various languages, e.g. Brazilian Portuguese (Tescari Neto 2013), English (Zyman 2012, Payne 2018), Hindi (Bhatia 2006), and Turkish (Wilson and Saygın 2001). However, there noted several empirical problems against this proposal. For instance, based on corpus data and large-scale acceptability judgements, Payne (2018) observed that Cinque’s (1999) hierarchy lacks some crucial ordering. Based on semantic categories, Payne (2018) proposed five classes of adverb hierarchy to account for such orderings. These classes are as follows: evaluative/speaker-oriented adverbs (apparently and frankly), epistemic adverbs (probably and perhaps), tense & aspectual adverbs (already, no longer, still, almost and once), frequency & degree adverbs (always, never, rarely, actually, really and very), and manner adverbs (neatly and quickly) (p. 17).

Ernst (2014) did a two-fold summary of the main critique against the Cinquean approach. (a) The notion of a universal mandatory order of functional heads does not predict the zones of adverbs. This notion is not based on any empirical grounds. For example, in Cinque (1999), modal heads precede aspectual heads, and two of these heads precede the heads that host manner and degree adverbs, which thus, might be ordered differently. There is no common generalization about the scope of behaviour for adverbs allowing free alternate zones, and the same applies to the free order of participant PPs (Ernst 2002). (b) Another major critique against cartographic theories comes from the roll-up movement, as argued by Ernst (2014). According to Bobaljik (2002), Bobaljik and Jonas (1996), and Ernst (2002), this movement does not guarantee the derivation of underlying structures without the loss of restrictiveness (p. 120). As it is commonly assumed in generative syntax, the movement of any constituent outside its domain requires empty functional heads that create a landing site for feature-checking requirements, which in turn, provide a specifier position as the targeted position. Overall, considering the wide variety of adverb orders across languages, studies based on the Kaynean proposal may not account for such a flexible variation. Such studies mostly proliferated the functional heads (Cinque’s (1999) proposal as an example), such as a Functional Phrase or Word order Phrase, to account for the flexible distribution of adverbs. If these functional projections corresponded to certain morphological or phonological requirements, then these heads must be specified (Kremers 2005, 2009). These points were addressed in Ernst (2002, 2014, 2020) and were the points of departure for the current proposal. The most direct question to be addressed is how to account for the flexible order of adverbials in Arabic without proliferating unspecified heads or assuming unnecessary movements. More precisely, how and where different types of adverbials in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) are introduced into syntactic structures.

2.2 Semantics-driven approach

The semantics-driven approach, also known as the scopal approach or adjunction approach, was initially proposed by Jackendoff (1972) and was later extended by Bellert (1977), Ernst (1984, 2002, 2007, 2009), Haider (2000, 2004), Kaufman (2006), and Alexiadou et al. (2009), amongst others. The core notion of scopal theories is that adverbials of all types adjoin freely (except the negative adverb, not) in phrase structures as far as the syntax is concerned, or else, their distribution is determined by their semantic and morphological (prosody and length, for example) constraints (Ernst 2002, Haider 2000). Under this free adjunction, their possible positions (zones) are determined by the semantics and their weight[1] (heavy or light). Ernst (2002, 2009, 2014) argued that the structure and meaning of adverbials are governed by the “Fact Event Object[2]” calculus of the Logical Form (LF), in which the lexicosemantic requirements of adverbs are specified. Thus, adverbs are classified into predicational adverbs, functional adverbs, and participant adverbials. Accordingly, Ernst proposed the following five-level hierarchy, as in (1), while Haider suggested the three-level hierarchy, as in (2).

| (1) | Speech act > fact > proposition > event > specified event (Ernst 2014, 121). |

| (2) | Proposition > event > process (Haider 2000, 26). |

The significant generalisation derived from (1) and (2) is that verb-oriented modifiers must merge with verbs before moving to subject-oriented or other event-modifier positions and that sentence-oriented modifiers are only possible when this stage is completed (Ernst 2014). In this way, a rigid order can be accounted for by specifying zones for different types of adverbs, although there is a distinct possibility of two adverbs of the same type occurring in the same zone, for example, ‘occasionally’ and ‘willingly’, as in (3).

| (3) | (Occasionally,) they willingly have (occasionally) been paying for catering help (occasionally). (Ernst 2014, 113) |

Weight considerations are also used in some scopal analyses to account for restrictions in terms of ‘heavy and light’ semantic scope. Heavy adverbs tend to appear in the right periphery, following the verbs in head-initial languages, while light adverbs cannot (Ernst 2014). The same goes for reorderable post-verbal adverbs, in which heavier elements tend to be in the right when more than one adverb has a similar semantic function as in the following (4).

| (4) | |

| a) They jump often on the bed as quickly as they feel sleepy. | |

| b) They jump quickly on the bed usually when they finally feel sleepy at night. |

The general notion of free adjunction allows adverbials to be either in a complementary or in a specifier direction of the head via the head-direction parameter (Ernst 2002), thereby suggesting that adverbials are pre-verbal adjuncts in OV languages and are pre-verbal or post-verbal in VO languages (Ernst 2002); however, Haider (2004) claimed the opposite for VO languages.

Movement is another syntactic mechanism that affects adverbs. In simple cases, head movement is allowed, while for discourse purposes, Aʹ-movement is allowed, although other versions of scopal theories permit the right adjunction to account for the word order, concentric scope, and concentric constituency of sentences directly in the phrase structure, without movements (Ernst 2014, 122). The free adjunction noted above also suggests that verb-modifying adverbials may have the order as in (5), wherein the adverb can optionally precede or follow the verb, while sentence-modifying adverbs appear at the leftmost of the sentence, as in (6).

| (5) | [VP (Adv) [V (NP)] [(Adv)]]. |

| (6) | [CP [CP Adv [TP…]]. |

Scopal theories have outlined many generalisations concerning the distribution of adverbials without movements, proliferated projections, and stipulated parameters on movement. The difference between a rigid and flexible order in scopal theories is accounted for similarly by the semantic properties of the adverbs. Thus, alternative orders may result if the scope constraints, selection requirements, or further semantic properties are not violated, although this alternative order may present different readings. Some versions of scopal theories that adopt the right adjunction have outlined a straightforward account that predicts the constituent structure more directly. Maienborn and Schäfer (2019) classified adverbials based on their semantics into predicational, participant, and functional adverbs. Predicational adverbs include sentential and verb-oriented adverbs. Sentential adverbs, in turn, include subject-oriented, speaker-oriented, and domain/frame adverbs. Speaker-oriented adverbs include speech-act, epistemic, and evaluative adverbs (Maienborn and Schäfer 2019, 13).

3 Theoretical assumptions

This article adopts the scopal theories as outlined above and applies a phase analysis to account for the distribution of adverbials in Arabic. Phase is first introduced in Chomsky’s (2000) ‘Minimalist Inquiries’, also discussed in greater detail in Chomsky (2001, 2008), whereby a phase is defined as a syntactic object derived by lexical sub-arrays (2000, 106). Such characterisation is relative to the propositional status or completeness. Others characterised phase in terms of its head properties, in which a phase head is assumed being the loci of uninterpretable features (cf. Gallego 2010, Legate 2012), or in terms of the interface status, whereby a phase is a convergent object that determines points of Transfer (cf. Citko 2014, Matushansky 2005). Phases play a central role in the derivation of syntactic structures in the framework of a minimalist program, in which structures are formed derivationally phase by phase.

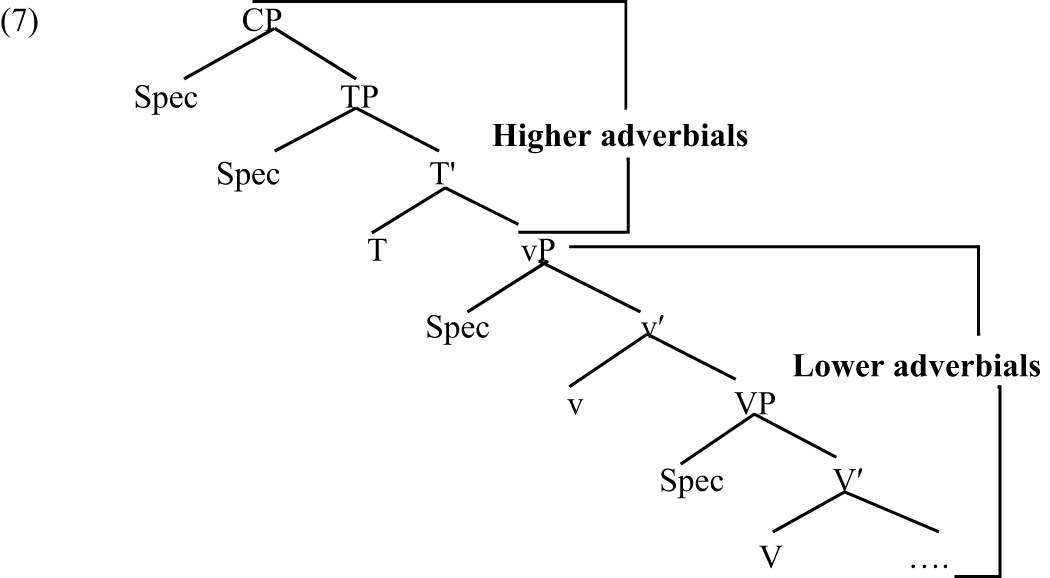

In relation, Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2008) argued that there is a single computational cycle that constructs the derivation until the phase is established through numerous applications of Merge, Move, and Spell out processes (see also, Carnie 2021, Carnie and Barss 2006, Adger 2003, 2010, among others). Once the phase is established, it is transferred to the LF and Phonetic Form (PF) for a proper interpretation (Frank 2004, Grohmann 2009, Freidin 2016). The existence of three core symmetrical functional categories (i.e. C, T, and v) in the derivation was one of the significant problems in the definition of the phase.[3] Chomsky (2008) defined the phase as a single unit of syntactic computation, the head of which is responsible for triggering syntactic operations. Chomsky (2001, 2008) posited that the functional phases CP and v*P are the only single phases. The functional head C, according to Rizzi (1997), represents the left periphery, and v* represents the functional heads that are associated with the argument/thematic structure. Since the CP is higher in the hierarchy than the vP in the articulated clause structure of Rizzi, we further argue that the adjunction points of adverbials can be regulated by their semantics and modification scope, where adverbials can be divided into higher or lower adverbials, depending on the points in which they adjoin. Higher adverbials have a wide semantic and modification scope and appear higher than the vP phase, while lower adverbials have a narrow semantic and modification scope and appear within the vP phase. The following is the cartographic structure assumed in this study, where the adjunction field for each type is identified.

The structure in (7) illustrates that CP is the adjunction site of the higher adverbials, while the lower adverbials adjoin vP. The division of adverbials into higher and lower adverbials comes from the fact that the CP phase is hierarchically higher than the vP phase. This notion of phrasal zones or regions is implicitly reflected in many scopal theories, and this was taken as a point of departure for our proposal. The previous proposals are summarised below, where CP is commonly assumed to include its complement, TP, and vP to include its complement, VP.

| (8) | Adjunction sites of adverbials in previous proposals |

| Proposal | CP | vP |

|---|---|---|

| Jackendoff (1972) | Speaker-oriented | Subject-oriented, Manner |

| Quirk et al. (1972) | Conjunct, disjunct | Process, Adjunct |

| McConnell-Ginet (1982) | Sentential adverbs | Verb-oriented adverbs |

| Frey and Pittner (1999) | Frame, proposition | Event, Process |

| Ernst (2002) | Speech act, proposition | Event, Specified Event |

| Haider (1998, 2000) | Proposition | Event, Process |

According to the cartographic approach of Rizzi (1997, 2004), the CP, TP, and VP are not single projections, but instead, they can further split into different functional projections. CP can split into Force, Topic, Focus, and Finite; while TP can split into Mood, Tense, and Aspect (Pollock 1989, Chomsky 1991), while VP can split into the functional head, vP, and lexical head, VP (Koizumi 1995, Radford 2009). Chomsky (1995, 1998, 2001, 2004) posited that the derivation converges only if the PF and LF interfaces satisfy the inclusiveness condition, which blocks the introduction of any new features.

Earlier versions of Phrase Structure Grammar, in particular, the X-bar theory, distinguished between two sets of mergers, namely, argument and adjunction mergers. An argument is merged as the projection of the head, while an adjunction is not. For example, if an AdvP is adjoined to XP, the constituent structure looks like [AdvP, XP], in which XP retains all its properties, and there are no semantic selective relations between them. In some earlier models of generative syntax, set-merge and pair-merge are used to distinguish between the two. The former is the property of an argument, while the latter is the property of an adjunction (Chomsky 1998, 2004), whereby an adjunction is assumed to be a separate attachment. These two terms (set-merge and pair-merge) are roughly used in the Government and Binding theory and early minimalist program to correspond to ‘substitution’ and ‘adjunction’ (Chomsky 1998, 2004). The relevant theoretical question about adjunctions is about how they work empirically. Chomsky (2004) posited that it is necessary to identify the way that relations and operations take place to derive structures that involve adjunction. He argues that an adjunction applies cyclically in overt syntax in which the c-command relation is preserved.

Having outlined the theoretical background, the semantic-based theories along with Chomsky's (2000, 2001, 2008) notion of phases are adopted to propose a phasal account to describe the distribution of adverbials in Arabic according to the proposed principle of phase-based adverbial positioning, outlined as follows.

| (9) | Adverbial positioning |

| Speech act and proposition-modifying adverbials have a wider semantic scope and modification domain; thus, they attach to the higher layer above vP, while subject-modifying and verb-modifying adverbials have a narrow semantic scope and modification domain; thus, they attach to the vP layer. |

Essential to our proposal, are the semantics, the categorial status, and the prosodic[4] structure of the adverbial which predicts the displacement points (lower or higher) of adverbs and adverbials. More discussion with empirical evidence on this proposal is provided in Section 6.

4 Previous analyses of adverbials in Arabic

There are several studies on the description of adverbs in Arabic (Al Aqad 2013, Al-Bom and Jarrah 2020, Al-Ghamdi 2018, Al-Shammiry 2016, Fehri 1993, 1997, 1998, 2003, Al-Shurafa 2005, Sulayman 2021). All these studies advocated that in Arabic, adverbs function as adjuncts and appear in various positions, such as pre-verbal, post-verbal, and sentence-initial positions. In Arabic, adverbials add information about the degree, time, manner, or place of the meanings of verbs or sentences. Adverbs can also modify adjectives or other adverbs (Ryding 2005, 276). The literature on the Arabic language also shows that this class of words is heterogeneous and can appear in different positions (Badawi et al. 2015), for instance, before or after a verb phrase or in a sentence-initial position (Fehri 1998). Few studies in Arabic have analysed the structure and scope of adverbs, and most of these studies either adopted or testified Cinque’s (1999) proposal (Fehri 1997, Al-Shammiry 2016, Al-Ghamdi 2018, Al-Bom and Jarrah 2020). This section reviews the existing studies on the structure and scope of adverbs in general including those examined MSA.[5]

Adverbials in Arabic are typically expressed in three syntactic categories: as Adjective Phrases (APs), Noun Phrases (NPs), or Prepositional Phrases (PPs, Fehri 1998, Al-Shurafa 2005) as follows:[6]

| (10) | raʔay-tu | l-walad-a | jayyid-an. | (AP) | |

| saw-I | the-boy-Acc | perfect-Acc | |||

| “I saw the boy perfectly.” | |||||

| (11) | nasiya | l-mudarris-u | ħageeba-ta-hu | tamaam-an. | (NP) |

| forgot | the-teacher-Nom | bag-Acc-his | completely-Acc | ||

| “The teacher forgot his bag completely.” | |||||

| (12) | nasiya | l-mudarris-u | ħageeba-ta-hu | l-baariħat-a. | (NP) |

| forgot | the-teacher-Nom | bag-Acc-his | the-yesterday-Acc | ||

| “The teacher forgot his bag yesterday.” | |||||

| (13) | kataba | r-rajul-u | bi-surʕat-in. | (PP) | |

| wrote | the-man-Nom | with-rapidly-Gen | |||

| “The man wrote rapidly.” | |||||

As can be noted from (10) to (13), the adverbials jayyid-an ‘perfectly’, tamaam-an ‘completely’, l-baariħat-a ‘yesterday’, and bi-surʕat-in ‘rapidly’ belong to different syntactic classes. In (10) jayyid-an is an AP that functions as an intensifier adverbial, tamaam-an in (11) is an NP that characterises the degree of the event described by the verb took place, l-baariħat-a in (12) is an NP that denotes the time of the event, and bi-surʕat-in in (13) is a PP that specifies manner of the event.

In terms of their distribution, Fehri (1998) argued that adverbs in Standard Arabic are base-generated in the final positions of the sentence, after the verb, subject, and object. Moreover, he claimed that based on Cinque’s (1999) proposal, adverbs in Arabic undergo movement to a higher position to the left periphery of the clause adjoining the specifier positions of Aspect, Tense, and Modality. Fehri classified adverbs into three groups, based on their distribution: (1) adverbs that occur after or before the object, but cannot occur higher than the predicate, (2) adverbs that can occur higher than TP, (3) and sentential adverbs that can be in the sentence-initial position, as follows:

| (14) | ʔkaltu | t-tuffaħat-a | tamaam-an. | ||||

| ate-I | the-apple-Acc | complete-Acc | |||||

| “I ate the apple completely.” | |||||||

| (15) | lam | yakun | r-rajul-u | gablu | qad | ʔakala | 1-tuffaaħ-a. |

| not | is | the-man-Nom | before | indeed | ate | the-apple-Acc | |

| “The man had not really eaten apples before.” | |||||||

| (16) | saraaħat-an | intahaa | kull-u | šayʔ-in. | |||

| frankly -Acc | end.past | every-Nom | thing-Gen | ||||

| “Frankly, everything has ended.” | |||||||

Similar to Cinque (1996), Fehri (1998) argued that the hierarchy, the fixed order, and the scope of adverbs follow the universal hierarchy of functional heads.

In contrast, despite the spoken dialectal varieties of Arabic being part of general Arabic, they are different in various grammatical aspects. Based on the findings of Jackendoff (1972), Al-Shurafa (2005) asserted that adverbs in both Palestinian Arabic and Hijazi Arabic can be classified into verbal adverbs and sentential adverbs. Verbal adverbs can either occur before or after the verb, while sentential adverbs can either occur in the sentence-initial or final position. In another dialectal variety of Arabic, similar to Cinque (1999), Sulayman (2021) argued that adverbs in Iraqi Arabic are specifiers of the functional heads. However, he argued that Cinque’s model cannot fully predict the distribution of adverbs in Iraqi. In Jordanian Arabic, however, Al-Bom and Jarrah (2020) showed that Cinque’s (1999) proposal can successfully explain the distribution of adverbs.

In a separate study, Al Aqad (2013) applied the X-bar theory to contrast the structure of adverbs in English and Arabic. He concluded that an adverb in Arabic can appear in multiple positions, for instance, at the beginning of the sentence, middle of the sentence between the verb and the object, and at the end of the sentence. He further argues that the meaning of the sentence changes as the position of the adverb changes, with no further explanation whether it’s in terms of syntax or semantics. Similar to Al-Shurafa’s (2005) basis for the distribution of adverbs, Al-Shammiry (2016) concluded that adverbs in the Saudi Northern Region Dialect of Arabic can be classified into pre-verbal adverbs and post-verbal adverbs based on their position. In other Saudi dialects of Arabic, Al-Ghamdi (2018) contended that neither the feature-based theory of Cinque (1999) nor the scope-based theory of Ernst (2002) can adequately account for the hierarchy of adverbs in Ghamdi Arabic. Instead, he suggested a free adjunction analysis to account for adverbs’ position in Ghamdi Arabic. This argument stems from the fact that Ghamdi Arabic shows flexible and interchangeable ordering and scope of adverbs. Adverbs can have interchangeable hierarchies without affecting the grammaticality of the sentence, but their semantics follow the FEO calculus of Ernst’s (2002) proposal. He particularly pointed out the limitation of Cinque’s (1999) universal hierarchy to explain such a phenomenon. Observe the following pair in (17).

| (17) | a) | Mohammad | mɑ | ʕɑd | mafiːh | daim | jifɔːz. | ||

| Mohammad | NEG | has | no longer | always | win | ||||

| “Mohammad has no longer always won.” | |||||||||

| b) | Mohammad | daim | mɑ | ʕɑd | mafiːh | jifɔːz. | |||

| Mohammad | always | NEG | has | no longer | win | ||||

| “Mohammad has always no longer won.” | |||||||||

| (Al-Ghamdi 2018, 25) | |||||||||

In (17), two different hierarchies of adverbs are observed. In (17a), the ordering is in line with Cinque’s hierarchy in which the negation element ma ‘not’ precedes both mafiːh ‘no longer’ and daim ‘always.’ In contrast, (17b) is against Cinque’s hierarchy in which daim precedes the negation and mafiːh, although both are grammatical. On the other hand, there are instances in Ghamdi Arabic where speech-oriented and evaluative adverbs, although they belong to the same semantic class as discourse-oriented adverbs, can have an alternating hierarchy, as noted in the following (18).

| (18) | a) | bisˤarah | ʕala-ħaðˤik | int | inqabalt. | |

| frankly | luckily | you | were accepted.PAST | |||

| “Frankly, luckily you were accepted.” | ||||||

| b) | ʕala-ħaðˤik | bisˤarah | int | inqabalt. | ||

| luckily | frankly | you | were accepted.PAST | |||

| “Luckily, frankly you were accepted.” | ||||||

| c) | bisˤarah | int | inqabalt | ʕala-ħaðˤik. | ||

| frankly | you | were accepted | luckily. | |||

| “Frankly, you were accepted luckily.” | ||||||

| (Al-Ghamdi 2018, 33–4) | ||||||

To account for such issues, Al-Ghamdi (2018) suggested free adjunction analysis of the structure of adverbs in Ghamdi Arabic. However, no further discussion was provided by Al-Ghamdi (2018) on such variability, whether it is random or rule-governed. Overall, the above discussion suggests that while Cinque’s (1999) and Ernst’s (2002) proposals predicted many of the acceptable adverb orders in Arabic, there are some constraints to predict all of them. Thus, alternative models are needed that can predict the displacement of adverbs in Arabic, particularly in MSA.

5 Methodology

This article is based on an exploratory research design due to the limitation of sources in relation to the description of adverbials in Standard Arabic. By adopting a qualitative method, an in-depth examination of the syntax and semantics of adverbs from secondary data was undertaken. Secondary data were collected from existing sources, namely, peer-reviewed journals and books that focused on the description of adverbials in Standard Arabic. As the matter of fact, Arabic speakers do not use MSA in their everyday conversations, they rather use their own dialectical varieties, such as Egyptian Arabic, Sudanese Arabic, Saudi Arabic, etc. Therefore, it is quite challenging to collect primary data on MSA from nowadays Arabic speakers. As debated in Gadamer (2004), secondary data can better explain and solve the undergoing problem without requiring a more expensive stage of primary data. Accordingly, this study was aimed at providing a unified analysis of the syntax and semantics of adverbs in MSA from the theoretical perspective of the minimalist program, as outlined in Chomsky (2001, 2008) and subsequent works.

6 Analysis of adverbials

The most common definition of adverbs is found in Hurford (1994) in which adverbs in general add specific information about time, manner, and place; they may also add information to adjectives and other adverbs (p. 10). Thus, they are additives – the optional elements of the core proposition (Stubbs 1991). The definition of adverbs in Arabic is constrained by their adverbial status (their syntactic function). These linguistic expressions are heterogeneous and can be distinguished by their syntactic category and semantic interpretation concerning the elements they modify (Pittner et al. 2015). The traditional semantically based classification of adverbials according to the degree, time, manner, place, etc. is reflected in the literature on the traditional description of adverbs. Since there are no unified morphosyntactic characteristics of adverbials in Arabic as in some other languages, it is important to distinguish between lexical adverbs and functional adverbials. Adverb refers to the lexical class, and adverbial to the functional class that modifies the predicate or the whole proposition. Adverbials are heterogeneous forms when it comes to their composition. They can be single words as in ʔbad-an ‘never’ or with phrases ʔilaa Hadd-in maa ‘to a certain extent’. This linguistic class in Arabic includes other grammatical structures, for instance, the cognate accusative, adverbial accusatives of cause or reason, the accusative of specification, and circumstantial phrases (Ryding 2005, 276–7). This study deals with all these types of adverbials and aims to provide a semantic-phrasal account of their displacement in the articulated clause structure of MSA.

The cross-linguistic semantic classification of adverbials into predicational adverbials, participant adverbials, functional adverbials, domain adverbials, and adverbial CPs (as noted in Ernst (2002, 2020), or predicate adverbials and sentence adverbials (as indicated in Costa (2008) partially predicts the zones of their adjunction. Like Ernst (2002, 2004, 2009) and Frey (2003), this study argues that the position of adverbials is mostly determined by their semantics scope and modification domain. The modification here involves three components: semantic, syntax, and discourse; it is defined as an expression that is generated due to a modifier introduction into the expression. The outcome of the syntactic component retains the formal properties of the modified element, the outcome of the semantic component shows some changes in the meaning between the modifier and the resulting expression, despite the meaning remaining of the same kind, and the outcome of the discourse component is the function that the semantic element takes (Hallonsten Halling 2018, 39). The following examples show these modification properties.

| (19) | a) | jaaʔa | al-walad-u. | |

| came | the-boy-Nom | |||

| “The boy came.” | ||||

| [VP jaaʔa al-walad-u] | ||||

| b) | jaaʔa | al-walad-u | musriʕ-an. | |

| came | the-boy-Nom | fast-Acc | ||

| “The boy came quickly.” | ||||

| c) | [VP [VP jaaʔa al-walad-u] AdvP musriʕa]]. | |||

The syntactic properties of the examples in (19a) and (19b) remain the same before and after the modifier musrʕ-an ‘quickly’ was introduced. In (19b), jaaʔa musriʕa ‘came quickly’ is still a verb phrase. Semantically, in the example in (19b), the modified element still belongs to the same domain of jaaʔa ‘come’ indicating different ways of coming.

Extending Chomsky’s view of phases, this study further assumed that the highness of adverbials in Arabic could best be analysed in terms of lower adverbials and higher adverbials, based on their adjunction site (whether they are adjoined to the vP layer or the CP layer) in the articulated cartographic structure. Their adjunction sites are partially predicted from their semantic scope and modification domain. The class of adverbials traditionally referred to as subject-modifying and verb-modifying adverbials (Ernst 2009, 2014, Fehri 1998, Cinque 1996, 1999, among others) are lower adverbials in MSA because of their narrow semantic scope, they usually tend to adjoin the vP phase. On the other hand, sentence-modifying adverbials are higher adverbials because of their wider semantic scope, they attach to positions that are higher than the vP, hence, sentence-initial position, or positions higher than vP, particularly within the CP phase. These assumptions will be discussed and supported by empirical evidence to show how a semantic-based analysis can offer a reasonable account of the distribution of adverbs and adverbials in Arabic. Before discussing adverbial placement, it is important to discuss the semantic classes of adverbials in Arabic followed by the discussion on their semantic scope and modification domain.

6.1 Adverb classification in Arabic and their semantic scope

In this subsection, we provide linguistic data on how the traditional semantic classification in Arabic partially established the relationship between the semantics and the syntax. The majority of the literature on adverbs and adverbials classifies adverbials in Arabic into four classes. These four groups include degree, manner, time, and place adverbials (Ryding 2005, Al-hawary 2011, Schulz 2004). Degree adverbials, also known as degree modifiers or intensifiers, are adverbs or adverbial phrases that modify adjectives, adverbs, or other expressions to indicate the intensity, extent, or degree of something. They typically express how much or to what extent a quality or action occurs. They always tend to occur towards the end of the clause or the phrase they modify. Examples of such a semantic class of adverbials are faqaT ‘only’, jidd-an ‘very’, kathiir-an ‘much’, tamaam-an ‘completely’, etc.

| (20) | Kaanat | Haflatu | takhriij-in | faqaT. |

| was | ceremony | graduation-Gen | only | |

| “It was a graduation ceremony only.” | ||||

| (21) | Jalas-tu | li-waqt-in | Tawiil-in | jidd-an. |

| sit-down-I | for-time-Dat | long-Gen | very | |

| “I sit down for a very long time.” | ||||

Manner adverbials describe the manner, the state, the circumstances, or the condition, in which something takes place, therefore providing more options for describing these aspects. The semantic class of manner adverbials include demonstrative pronouns such as haakadhaa ‘thus; in such a way; and so’, nouns and adjectives in accusative case form such as fawr-an ‘immediately’, jamiiʕ-an ‘together’, circumstantial accusative such as musriʕ-an ‘quickly’, cognate accusative such as faraH-an shadiid-an ‘extremely happy’ and some prepositional phrases which function as adverbials such as bi-surʕat-in ‘quickly’. All these manner adverbials follow their modified elements except demonstrative pronouns which precede their modified elements as follows. Structurally, manner adverbials usually follow the predicate and thus fall within the vP layer or any other predicate phrase below CP.

| (22) | jaaʔa | musriʕ-an. | ||

| came.Past.Masc | quickly | |||

| “He came quickly.” | ||||

| (23) | naHnu | jamiiʕ-an | naʕmalu | li-ssalaam. |

| we | together | work | for-peace | |

| “We are all working together for peace.” | ||||

| (24) | Haakadhaa | farih-at | aT-Taaliba-t-a | bi n-natiijat-i |

| thus | happy-Fem | the-student-Fem-Acc | with the-result-Gen | |

| “Thus, the student was happy with the result.” | ||||

Adverbials of place in Arabic include deictic locatives such as hunaa ‘here’ and its variants which generally indicate locative, direction, and existence. This class of adverbials also includes hayth-u ‘where’ which is used to connect one clause with another to indicate the concept of ‘where; in which’ in relation to the clause it modifies. It also includes accusative adverbial of place that typically denote direction or location such as yamiin-an ‘right’, yasaar-an ‘left’, and other locative adverbs such as taHt-a ‘under’. Adverbials of place in Arabic tend to appear towards the end of the phase or the clause. However, they can appear at the beginning of the sentences in the topic structures.

| (25) | ʔataa | min | hunaa/k. |

| came | from | here/there | |

| “He came from here/there.” | |||

| (26) | ittajaha-t | shamaal-an. | |

| headed-Fem | North | ||

| “She headed towards the north.” | |||

Adverbials of time indicate the time frame and come in four categories: adverbs of time, accusative nouns and adjectives, time demonstrative expressions, and other adverbial phrases. Examples of adverbs of time include amss ‘yesterday’, alʔaan-a ‘now’, baʕd-u ‘still; yet’, examples of accusative nouns and adjectives such as ʔabad-an ‘never’, Hadiith-an ‘recently’, respectively. Time demonstrative expressions include dhaak-a ‘that’ and its variants such as ʔaan-a dhaak-a ‘at that time’, ʔidhin ‘that’ and its variants such as yawm-a ʔidhin ‘on that day’.

In fact, many more classes of adverbials do not fit into these four traditional classes of adverbials. These include, first, numerical adverbials such as ʔawwala-n ‘first; firstly’ and all sequence points expressions. Second, adverbials of specification (al-tamyiiz in Arabic term) such as siyaasiy-an ‘politically’, third, adverbials of motion, cause, or reason such as natiijat-an ‘as a result’, and last, speech act adverbs such as marHab-an ‘hello’. Therefore, the traditional semantic categories of adverbs and adverbials in Arabic partially predict places of adverbials. Similarly, Sawaie (2015) found that adverbs of different types in Arabic generally occur after or close to the verb they modify. However, they are quite free in terms of their mobility for stylistic and highlighting purposes. Note the following example for emphasis variation.

| (27) | a) | inTalaqat | sayyaarat-u | al-shurTat-i | bi-surʕat-in | kabiirat-in. | [Manner adverbial] |

| set-out | car-Nom | the-police | speed-Gen | high-Gen | |||

| “the ploice car set out at high speed.” | |||||||

| b) | bi-surʕat-in | kabiirat-in | inTalaqat | sayyaarat-u | al-shurTat-i. | [Focused element] | |

| speed-Gen | high-Gen | set-out | car-Nom | the-police-Gen | |||

| “the police cas set out at high speed.” | |||||||

| (Sawaie 2015, 65) | |||||||

6.2 Adverbial modification domain

Before we discuss these two proposed classes of adverbials in Arabic, in the following examples, we show how the modification domain[7] can give some partial information about their attachment sites in the structure of the clause or the phrase.

6.2.1 Lower adverbial

| (28) | ||||

| a) | ʔakaltu | at-tuffaahata | tamaam-an. | |

| ate.I | the-apple | completely | ||

| “I ate the apple completely.” | ||||

| b) | [TP [VP [VP ʔakaltu at-tuffaahata [AdvP tamaam-an]]]]. | |||

6.2.2 Higher adverbial

| (29) | |||||

| a) | Saraahat-an , | ma zaala | al-waqtu | mubakkir-an. | |

| Frankly-Acc, | not yet | the-time | early | ||

| “Frankly, it is still early.” | |||||

| b) | [CP Saraahat-an [CP ma zaala al-wagtu mubakkir-an]]. | ||||

In (28) the adverbial tamaam-an modifies the predicate, while in (29), the adverbial saraahat-an modifies the whole proposition. However, the domain of modification does not correlate with their interpretation. This is because adverbials in some languages (Indo-European) within a single modification domain may have different interpretations as in the following examples from European Portuguese (Costa 2008).

| (30) | |||

| a) | Estupidamente , o João respondeu à pergunta. | [Subject-oriented reading] | |

| “Stupidly, João answered the question.” | |||

| b) | Matematicamente , isso é absurdo. | [Domain-oriented reading] | |

| “Mathematically, that is absurd.” | |||

| c) | F rancamente , eu tenho fome. | [Speaker-oriented reading] | |

| “Frankly, I am hungry.” | |||

| (Costa 2008, 14–5) | |||

Similar instances are noted in French, especially within manner adverbials. Duplâtre and Modicom (2022) showed that this class of adverbials tends to modify the illocutionary layer of the clause instead of the predication. The following examples show this case.

| (31) | ||

| a) | Bêtement , il a répondu au juge. | |

| “Stupidly, he gave an answer to the judge.” | ||

| b) | Il a répondu bêtement au juge. | |

| “He gave a stupid answer to the judge.” | ||

| (Duplâtre and Modicom 2022, 11) |

In (31a), bêtement is an evaluative adverbial with a wide semantic scope, thus modifying the overall proposition. While bêtement is a manner adverbial with a narrow semantic scope, therefore modifying the object. However, Arabic does not show these illocutionary modification properties, for instance, a manner adverbial cannot modify a proposition despite having a different semantic scope, as discussed in the following section.

6.3 Lower adverbials

The class lower adverbials include subject-modifying, verb-modifying, or any other adverbial type that has a narrow scope and adjoins the vP layer of the articulated clausal structure. Subject-modifying adverbials describe the speaker’s evaluation of some quality about the subject referent or indicate the subject’s mental attitude (Ernst 2002, 2014, Frey 2003). Their attachment is partly free, either before or after the verb. Thus, they are held to be vP layers or predicational adverbials. Verb-modifying adverbials are process or event modifiers. They can be further subdivided semantically into frequency, degree, and manner. Examples of verb-modifying and subject-modifying adverbials are given in (32).

| (32) | ||

| a) | Verb-modifying adverbials : tamaam-an ‘completely’, jayyid-an ‘perfectly’, kathiir-an ‘a lot’, jidd-an ‘very’, faqaT ‘only.’ | |

| b) | Subject-modifying adverbials : ʔabad-an ‘ever’, ʕamd-an ‘deliberately’, haqiiqat-an ‘indeed’, ʕumuum-an ‘generally’, daaʔim-an ‘always.’ | |

Despite verb-oriented and subject-oriented being distinguishable in terms of their semantic scope; they both belong to the same class as lower (vP) adverbials, from the fact they both cannot climb over the vP layer to the higher layer. We used the X-bar theoretic schema to distinguish between set-merge – argument-merge and pair-merge – adjunction. In other words, the distinction is made between the specifier, complement, and adjunct merger using the notions of the X-bar theory. Although different accounts have been used for this type of distinction (whether adjuncts attached to XP or Xʹs), there is a common consensus that the output of the adjunction keeps the labeling or the constituency intact. This entails that adverbial attaches to the maximal projection rather than any other projection. For a concrete discussion, note the difference between an adjunction and a merge in the following (33).

The schematic representation in (33a) demonstrates the following standard properties of adverbials’ adjunction. First, their adjunction preserves intact the information related to intermediate-level (bar-level) and maximal projections, categories, and headedness, while a complement does not. Second, the adverbial modifiers receive intermediate-level information about the structure it modifies. Finally, the number of adverbial adjuncts is not limited (Hornstein 2009, Hornstein and Nunes 2008). Van de Koot (1994), Adger (2003), Ackema (2015), and Barbu and Toivonen (2016) provided more discussion on the differences between adjunct and argument mergers. Since there is no limitation on the number of adverbial adjuncts, the adjunction of lower adverbials is partly free within their modification domain. Their free attachment within the zones noted in (7) and the recursion that they allow are the common properties of adjuncts. Lower adverbials attach to pre or post-object (34) and (35) or adjectival positions as in (36) and (37).

| (34) | samiʕ-tu | jayyid-an | l-tilaawat-a. |

| listened-i | perfect-Acc | the-recitation-Acc | |

| “I listened to the recitation perfectly.” | |||

| (35) | samiʕ-tu | l-tilaawat-a | jayyid-an. |

| listened-i | the-recitation-Acc | perfect-Acc | |

| “I listened to the recitation perfectly.” | |||

| (36) | huwa | ɣaaʔib-un | tamaam-an. |

| he | absent-Nom | completely | |

| “He is completely absent.” | |||

| (37) | huwa | tamaam-an | ɣaaʔib-un. |

| he | completely | absent-Nom | |

| “He is absent completely.” | |||

The manner adverbial jayyidan ‘perfectly’ in (34) and (35) and the degree adverbial tamaam-an ‘completely’ in (36) and (37) are distributed in two different positions, before the object and at the end of the sentence following the object or the adjective. However, jayyidan and tamaam-an have the same semantic scope, in that they both modify the verb or the adjective. It is in these positions that these adverbials receive their Case and interpretation via the c-command relation (Fehri 1997, 1998), in which the adjunction can be to the right or the left. It was also observed in Jackendoff (1972) that these lower adverbials in some other languages can occur in different orders with different meanings and perhaps scopes. This is commonly noted in English and other European languages as follows (Ernst 2002, 42).

| (38) | ||

| a) | Mary has answered their questions cleverly . | |

| b) | Mary cleverly has answered their questions. | |

| c) | Mary has cleverly answered their questions. |

The semantics of the adverbial cleverly in (38) is ambiguous to some extent in that it has both the manner and subject-oriented reading in each of the referred examples. Adverbials in Arabic, however, do not show this ambiguous characteristic. A lower adverbial, as suggested in this study, can be either a subject-oriented modifier or a manner modifier, but not a mixture of both (Fehri 1998, Ryding 2005 for further discussion). Contrast the following examples.

| (39) | ||||

| a) | darast-u | l-kitaab-a | jayyid-an. | |

| study.past-I | the-book-Acc | perfect-Acc | ||

| “I studied the book perfectly.” | ||||

| b) | darast-u | jayyid-an | l-kitaab-a. | |

| study.past-I | perfect-Acc | the-book-Acc | ||

| “I studied the book perfectly.” | ||||

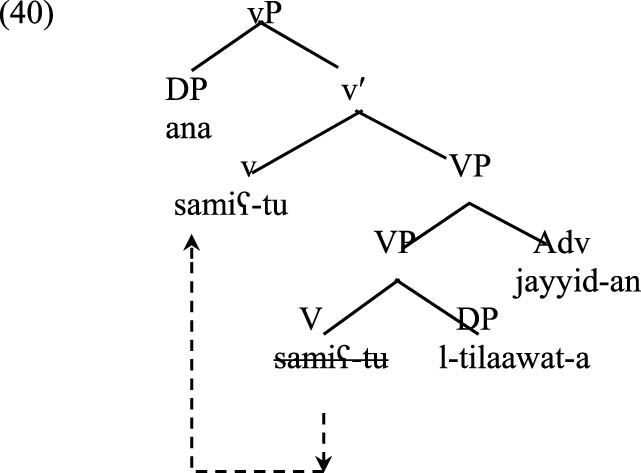

The manner adverbial jayyidan ‘perfectly’ in (39a) means that the speaker has studied every part of the book, whereas the alternative order in (39b) means that he/she has studied some part of the book (not necessarily the entire book). Thus, (39a) has the English paraphrased version as “the speaker studies the entire book” while (39b) can be paraphrased as “the speaker studied some parts of the book” (Fehri 1997, 19). Both instances indicate the manner of study, whether it’s partially or completely. Such a stylistic variation is also noted between (36) and (37), in which (36) entails a complete absent and (37) a partial absent at least at the time of the speech. In this case, the variation in the interpretation is the main determinant of its position. The association between the semantic scope of the adverb and its syntactic position, especially within the lower class is also noted by (Morzycki 2016). Thus, in Arabic, subject-oriented adverbials are hierarchically higher than manner adverbials. As noted above, lower adverbials are distributed freely within the vP phase and, thus, have different structures. The structure in (40) is proposed for post-object adverbials like the one in (35), with its counterpart labelled bracketing of the vP shell in (41), which shows that lower adverbials are vP-internal adverbs.

| (41) | [vP ana [vʹ] [V samiʕ-tu [VP [VP [V [DP l-tilaawat-a] [Adv jayyid-an]]]]. |

Given the structure in (40), a reasonable question would be concerning how the structure building would proceed. Following Larson (1988, 1990), Hale and Keyser (1991, 1993a, 1993b, 1994), and Chomsky (1995), the derivation in (40) would proceed as follows. The verb, samiʕ-tu ‘listened’ is merged with its internal argument, l-tilaawat-a ‘the recitation’ to form the VP, samiʕ-tu l-tilaawat-a ‘listened to the recitation’, the manner adverbial, jayyid-an ‘perfectly’ adjoins the VP to form another VP, samiʕ-tu l-tilaawat-a jayyid-an ‘listened to the recitation perfectly’. It is in this position that the adverbial jayyid-an receives its accusative case licensed by FEO as defended in Ernst (2002, 36–8). The resulting VP is then merged with the light abstract v, which has to do reading. This light abstract verb has a strong V-feature, triggering the lexical verb samiʕ-tu ‘listened’ to move via head-to-head movement to form the v-bar, samiʕ-tu + do l-tilaawat-a samiʕ-tu jayyid-an ‘did listen to the recitation perfectly’. The resulting v-bar is then merged with the external argument, the DP ana ‘I’, which is assigned an agent theta role by the verb to form the complex vP shell, samiʕ-tu l-tilaawat-a jayyid-an ‘I listened to the recitation perfectly’. At this point, the tree in (40) correctly predicted the order of (35), samiʕ-tu l-tilaawat-a jayyid-an and distinguished between the merger and adjunction,[8] in the sense that a merger expands different syntactic objects into a larger projection, (e.g. the merge of

V

samiʕ-tu ‘listened’ with DP

l-tilaawat-a ‘the recitation’ to the VP), while an adjunction, by contrast, expands the same syntactic object into a larger projection (e.g. the adjunction of Adv

jayyid-an ‘perfectly’ to VP

samiʕ-tu l-tilaawat-a ‘listened to the recitation’ yields another VP).

In contrast to Stepanov (2001) and Lebeaux (1988, 1991, and 2000), where the adjunction is assumed to be merged late (post-cyclically), this study claimed the standard assumption of a Bare Phrase Structure within the minimalist program (Chomsky 1995), and argues that an adjunction is a cyclic merger and that the adjunction of the adverbial jayyid-an ‘perfectly’ to the VP does not change the selective or interpretive properties of the VP, which is interpreted as being set-merged.

A similar account is generalised to circumstantial adverbials in Arabic. Circumstantial adverbs in Arabic refer to structures that express a certain range of circumstances under which an event takes place (Ryding 2005). Circumstantial adverbs appear in a similar position as manner adverbials. However, they are distinguishable from normal adverbials in that their order is fixed at the end of the sentence, and they typically are PPs or NPs except manner circumstantial adverbials. Moreover, they do not show a flexible order and cannot skip over the object to the positions available for other adverbials. This fact supports our hypothesis that lower adverbials are attached to the lower phase of the clause. Semantically, this subclass is different from adverbials in that they modify the predicate of an underlying event, but not the operators (Fehri 1998, Abu-Chacra 2007), as shown in the following:

| (42) | a) | kaana | r-rajul-u | yazuur-u | sadiiqa-hu | bi-stimraar-in. (PP) |

| was | the-man-Nom | visit-Nom | friend-his | with-constancy | ||

| “The man was visiting his friend constantly.” | ||||||

| b) | *kaana r-rajul-u | (* bi-stimraar-in ) | yazuur-u (* bi-stimraar-in ) | sadiiqa-hu. | ||

| was the-man-Nom | (with-constancy) | visit-Nom (with-constancy) | friend-his | |||

| “The man was visiting his friend constantly.” | ||||||

| c) | bi-stimraar-in kaana | r-rajul-u | yazuur-u | sadiiqa-hu. | (Focused) | |

| with-constancy was | the-man-Nom | visit-Nom | friend-his | |||

| “The man was visiting his friend constantly.” | ||||||

| (43) | a) | jaaʔa | l-mabʕuuthu | wahdahu. | (NP) | |

| came | the-delegate | alone | ||||

| “The delegate came alone.” | ||||||

| (* wahdahu) | jaaʔa | (* wahdahu) | l-mabʕuuthu. | |||

| alone | came | (alone) | the-delegate | |||

| “The delegate came alone.” | ||||||

As noted in (42) and (43), the adjunction site of circumstantial adverbs in Arabic is fixed and designated at the rightmost edge of the vP phase. However, PP circumstantial adverbs can appear in sentence-initial position as focused elements, not as adverbials as noted in (42c). Thus, circumstantial adverbials constitute a substantial class of their own in this respect, in that they do not characterise heterogeneous order.

Subject-oriented adverbials are another class of lower adverbials. In some languages this class has a unifying morphological characteristic, making them a distinguished class from others. For instance, Jackendoff (1972), Ernst (2002), Matsuoka (2013), Morzycki (2016) among others noted that nearly all adverbs in English end with -ly and take an event and a participant in the event as their complements. However, in Arabic, there is no unifying morphological characteristic for all classes of adverbials. Subject-oriented adverbials in Arabic occur between the subject and the main verb, as in (44) or between the subject and its adjective complement as in (45). The following structure in (46) is proposed to account for such type of adverbial.

| (44) | Al-rajul-u | ʕumuum-an | yaʔtii | mutaʔakhkhiran. |

| The-man-Nom | generally | he.comes | late | |

| “The man generally comes late.” | ||||

| (45) | huwa | daaʔim-an | ɣaaʔib-un. | |

| he | always | absent-Nom | ||

| “He is always absent.” | ||||

| (47) | [vP DP [v’] [Adv v’ [v][VP V [Adv]]]. |

The derivation proceeds in the following fashion. First, the verb, yaʔtii ‘come’ is merged with the adverbial, mutaʔakhkhiran ‘late’ to form the VP, yaʔtii mutaʔakhiran ‘comes late’. The resulting VP is then merged with the light abstract verb v, which has strong V-features that affect the verb to move from the head of the inner VP shell to adjoin it to form v-bar, yaʔtii + do mutaʔakhkhiran ‘does comes late’. Second, the adverbial, ʕumuum-an ‘generally’ is then adjoined to the resulting v’ to form another v’, ʕumuum-an yaʔtii mutaʔakhkhiran ‘generally comes late’. This v’ is then merged with the DP subject, al-rajulu ‘the man’ to form the complex vP shell, al-rajul-u ʕumuum-an yaʔtii mutaʔakhkhiran ‘the man generally comes late’.

Another characteristic of the lower adverbials is that they cannot precede negation or skip over TP to adjoin positions that are higher than the vP layer or sentence-initial, as shown in the following (48)–(51).

| (48) | (* jayyid-an ) | samiʕ-tu | l-tilaawat-a. | |

| perfect-Acc | listened-i | the-recitation-Acc | ||

| “(*perfectly) I listened to the recitation.” | ||||

| (49) | (*jayyid-an) | lam | a-smaʕ | l-tilaawat-a. |

| Perfectly-Acc | not | I-listen.Past | the-recitation | |

| “(*perfectly) I did not listen to the recitation.” | ||||

| (50) | Kaana-t | (* ɣaalib-an ) | ta-murru | bi-jaara-ti-ha. |

| Was-Fem | often-Acc | Fem-passes | by-neighbour-Fem-her | |

| “She was (*often) passing by her neighbour.” | ||||

| (51) | (* ɣaalib-an ) | kaana-t | ta-murru | bi-jaara-t-ha. |

| often-Acc | was-Fem | Fem-passes | by-neighbour-Fem-her | |

| “(*often) she was passing by her neighbour.” | ||||

In contrast, subject-modifying adverbs in languages such as English and perhaps in many other Indo-European languages can precede negation, as in (52). These subject-oriented adverbs may follow negation in marked contexts, which are generally assumed to have different scopes and readings.

| (52) | The winners of the competition ( cleverly, bravely, stupidly ) | didn’t use ropes. |

| (Ernst 2014, 111) |

Following that, it is reasonable to assume that the semantic scope and the modification domain partially regulate the distribution of adverbs and adverbials at least in Arabic and that the lower adverbials are vP layer adjuncts. It is also well-documented that adverbs such as quickly, slowly, sadly, frequently, often, and soon in English can appear in initial, final, or preverbal positions (Jackendoff 1972, Ernst 2014, Payne 2018), but Arabic does not allow such variations, despite spoken dialects allow it (cf. Ghamdi Arabic). Lower adverbials cannot skip to higher positions above the vP layer as the following (53), which along with the discussion provided above, supports the assumption that lower adverbials are vP adjuncts.

| (53) | (*musriʕ-an) | jaaʔa | (* musriʕ-an) | al-rajul-u | musriʕ-an. |

| (quickly) | come.past | (quickly) | the-man-Nom | quickly.Acc | |

| “The man came quickly.” | |||||

The notion of phase-based analysis of adverbs is also proposed by Mizuno (2010) to account for speech-act adverbs and epistemic adverbs in English. Mizuno (2010) argued that these two classes of adverbs are locally commanded by their licensers within phases. Mizuno’s (2010) proposal is based on locality principals, but our proposal is based on the semantic scope and the modification domain of adverbials.

Temporal or time point adverbials such as al-ʔaana ‘now’ al-yauma ‘today’, ʔams ‘yesterday’ are sentence-final adverbials in Arabic; however, temporal can appear in the left periphery in the focus constructions, such as follows.

| (54) | |||||

| a) | tamma | iftitaaH | al-mʕradh | al-ʔaana. | |

| was | launched | the-exhibition | now | ||

| “The exhibition was launched now.” | |||||

| b) | ( al-ʔaana ) | tamma | iftitaaH | al-mʕradh. | |

| now | was | launched | the-exhibition | ||

| “Now, the exhibition was launched.” | |||||

| c) | [CP al-ʔaana i [TP tamma iftitaaH al-mʕradh …. t i]]. | ||||

The two instances of al-ʔaana ‘now’ have different readings. In (54a), al-ʔaana refers to the starting time point, in that the sentence can have an English translation as ‘the launching time starts from now’, while in (54b) it refers to a particular time point, equivalent to ‘at this time, the launching took place’. This is commonly related to the focus position of the adverb, which means NOW not BEFORE. Interestingly, lower adverbials follow a fixed hierarchical restriction. Subject-modifying adverbials precede verb-modifying adverbials which precede manner adverbials, in the manner given in (55) and exemplified in (56a).

| (55) | SUBJECT-MODIFYING > VERB-MODIFYING > MANNAR | |||||||||||

| (56) | ||||||||||||

| a) | yashrahu | l-muʕallim-u | ħaqiiqat-an | ( tamaam-an ) | kulla | šayʔ-in | jayyid-an. | |||||

| explain | the-teacher-Nom | indeed-Acc | (completely) | every | thing | perfect-Acc | ||||||

| “The teacher is indeed explaining everything perfectly.” | ||||||||||||

| b) | yashrahu | l-muʕallim-u | * jayyid-an | ⃰ tamaam-an | kulla | šayʔ-in | * ħaqiiqat-an. | |||||

| explain | the-teacher-Nom | perfect-Acc | completely | every | thing | always-Acc | ||||||

| “The teacher is indeed explaining everything perfectly.” | ||||||||||||

The sentence in (56) contains three adverbials: ħaqiiqat-an ‘indeed’, tamaam-an ‘completely’, and jayyidan ‘perfectly’. The adverbial, haqiiqat-an ‘indeed’ is hierarchically higher than tamaam-an ‘completely’ and jayyid-an ‘perfectly’ and not the opposite, as the ill-formed sentence in (56b) shows. However, such hierarchical restrictions within the lower adverbials are only applicable in multiple adverbials sentences. As for the sentences with one adverbial, this adverbial can appear in multiple positions within the lower zone as noted in (39). Such hierarchical constraints suggest that lower adverbials in Arabic follow a certain hierarchy, as defended by Jackendoff (1972), Ernst (2014), and Fehri (1998). Fehri (p. 17) suggested the following hierarchy for lower adverbials.

| (57) | ʕumuuman ‘generally’ > baʕdu ‘after’ (qaţţu ‘never’) > daaʔiman ‘always’ > ħaqiiqatan ‘really, indeed’ > tamaaman ‘completely’ > jayyidan ‘perfectly.’ |

Although the modification of (56) shows these adverbials are categorised as lower adverbials, the question arises as to how the derivation proceeds. In other words, which adjunct merges first, and why? Assuming that the structure was built from the bottom upwards, the adjunction of jayyidan ‘perfect’ was before the adjunction of ħaqiiqatan ‘indeed’ and the optional adverbial tamaaman ‘completely’ because the latter preceded the former linearly. Therefore, the linear order of adverbials in Arabic may indicate their semantic scope. Lower adverbials of all classes cannot skip over the verb phrase layer to higher positions.

The linear order in (56) will have the structure as in (58) (we will not show the adjunction of tamaaman ‘completely’ because it is optional) where both the emphatic adverbial, ħaqiiqatan ‘indeed’ and the manner adverbial, jayyidan ‘perfectly’ are structurally attached to the VP shell, although the former precedes the latter. The adverbial, jayyidan ‘perfectly’ adjoins the rightmost edge of the VP, and ħaqiiqatan ‘indeed’ precedes the object, kulla šayʔ-in ‘everything’. The adjunction of jayyidan ‘perfectly’ and ħaqiiqatan ‘indeed’ conserves intact the labelling and headedness information of the derivation, thereby supporting the assumption that they are vP layer adjuncts.

| (59) | [vP DP [v’][v [VP] Adv [VP DP [Vʹ [t V] [adv]]]]]. |

In this subsection, it was argued that lower adverbials are vP adjuncts. This assumption was discussed and exemplified along with their cartographic structure. The attachment points of lower adverbials are flexible (either pre- or post-verbal) within the vP phase. The next subsection discusses the higher adverbials.

6.4 Higher adverbials

The higher adverbials have a wider semantic scope and modification domain, and they are CP-related adverbials that modify the whole propositions or eventualities. This group of adverbials in Arabic includes discourse-oriented adverbials such as saraaħatan ‘frankly’, evaluative adverbials such as Tabʕ-an ‘evidently’, and epistemic adverbials such as rubbamaa ‘perhaps’. This class of adverbials describes speaker’s attitude towards the proposition (Ernst 2014, Carnie et al. 2014), and therefore, they are sometimes known as speaker-oriented or speech act or pragmatic adverbials. Examples of higher adverbials which include discourse-oriented, evaluative, and epistemic adverbials are given in (60).

| (60) | Higher Adverbials |

| a) Discourse-oriented: saraaħatan ‘frankly or honestly.’ | |

| b) Evaluative: Tabiiʕiyyan ‘naturally.’ | |

| c) Epistemic | |

| I. Modals: iħtimaal-an ‘probably’, rubbamaa ‘maybe/perhaps.’ | |

| II. Evidentials: taʕkiid-an ‘certainly’ tabʕan ‘evidently.’ |

These proposition-modifying adverbials commonly appear in the clause-initial position above those zones or fields identified for lower adverbials. Occasionally they may appear in the other normal positions for sentential adverbs, following or preceding the finite auxiliary as in the following example:

| (61) | saraaħatan | l-ʔawDaaʕ-u | ɣayru | mustaqirrat-in. | ||

| frankly | the-situation-Nom | not | stable-Gen | |||

| “Frankly, the situation is unstable.” | ||||||

| (62) | Tabʕan | yazuuru | mohammed-u | l-madiinat-a. | ||

| evidence-Acc | visits | mohammed-Nom | the-city-Acc | |||

| “Evidently, Mohammed visits the city.” | ||||||

| (63) | rubbamaa | tataɣayyar-u | l-ʔawDaaʕ. | |||

| perhaps | change-Nom | the-situation | ||||

| “Perhaps, the situation may change.” | ||||||

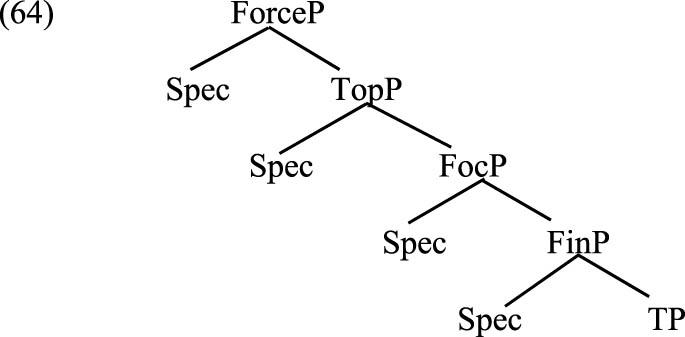

Traditionally, discourse-oriented adverbs are defined as functional lexemes that modify the content of a sentence (Ramat and Ricca 1998). Their classification into evaluative, modal, subject-disjuncts, and speech act adverbials is based on their modification status, i.e. whether they modify an event, proposition, or speech act (Swan 1988). The adverbials saraaħatan ‘frankly’ in (61), Tabʕan ‘evidently’ in (62), and rubbamaa ‘perhaps’ in (63) occur in a clause-initial position with pragmatic, evidential, and modal readings, respectively. These semantic interpretations, along with the modification domain they take, enable us to assume that these discourse-oriented adverbials are CP layer adjuncts, and thus, acquire the following structure, as in (64). Following Rizzi (1997), CP can further split into Force, Topic, Focus, and Finite in the manner shown in (65).

| (65) | [ForceP Force [TopP Topic [FocP Focus [FinP Fin [TP]]]]]. |

However, their adjunction is not always to the leftmost edge of the clause; they may attach to different zones within the CP layer or any zones above the vP layer, such as negation, auxiliaries, modals, TP, etc. In the following (66) and (67), for example, the adverbial qablu ‘before’ baʕdu ‘after’, respectively, appear above the perfective particle qad [9] ‘had’ and below the negation lam ‘not’, but still are located within the higher layer, because their attachment is above vP layer. Contrast the following examples.

| (66) | lam | yakun | mohammed-u | qablu | qad | zaara | l-madiinat-a. | |

| not | is | mohammed-Nom | before | had | visit | the-city-Acc | ||

| “Mohammed had not really visited the city before.” | ||||||||

| (67) | Lam | yakun | l-rajul-u | baʕdu | qad | waSal | l-qaryat-a. | |

| not | was | the-man-Nom | yet | has | arrived.past | the-village-Acc | ||

| “The man has not arrived in the village yet.” | ||||||||

| (68) | *( qablu ) | lam | yakun | mohammed-u | qad ( qablu ) | zaara | l-madiinat-a. | |

| (before) | not | is | mohammed-Nom | had (before) | visit | the-city-Acc | ||

| “Mohammed had not really visited the city before.” | ||||||||

| (69) | *(baʕdu) | Lam | yakun | l-rajul-u | qad | ( baʕdu ) | waSal | l-qaryat-a. |

| (yet) | not | was | the-man-Nom | has | yet | arrived.past | the-village-Acc | |

| “The man has not arrived in the village yet.” | ||||||||

It is natural to conclude that adverbials such as qablu ‘before’ in (66) and baʕdu ‘yet’ in (67) are higher adverbials, and they cannot precede the perfective particle, qad ‘has’ or skip over the negation, as in (68) and (69). This assumption is shown in the cartographic structure in (70).

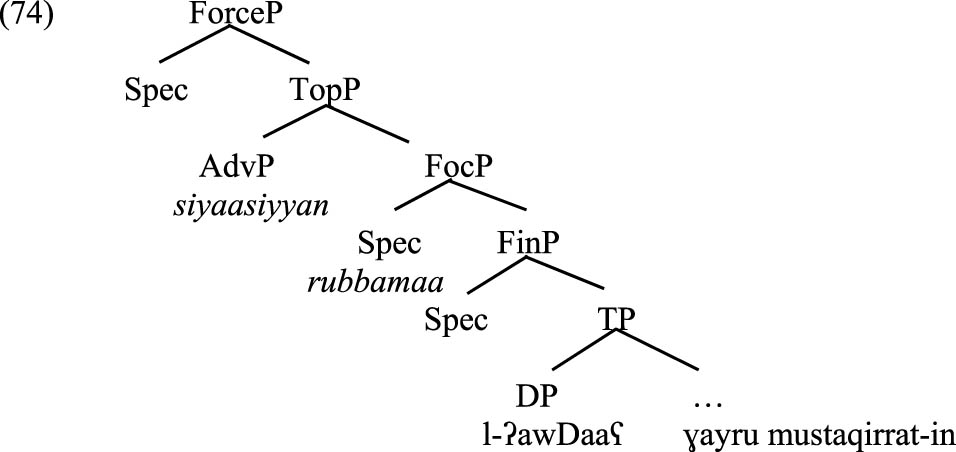

Interestingly, more than one higher adverbial can co-occur adjacently or non-adjacently in one sentence, as noted in (71). However, their order in terms of their hierarchy is constrained. Thus, higher adverbials in Arabic tend to follow the hierarchy given in (73).

| (71) | siyaasiyyan | rubbamaa | l-ʔawDaaʕ | ɣayru | mustaqirrat-in. |

| politically | maybe | the-situation | not | stable-Gen | |

| “Politically, the situation may not be stable.” | |||||

| (72) | (*rubbamaa) | siyaasiyyan | l-ʔawDaaʕ | ɣayru | mustaqirrat-in. |

| maybe | politically | the-situation | not | stable-Gen | |

| “(*Maybe) politically, the situation is not unstable.” | |||||

| (73) | DISCOURSE-ORIENTED > EVALUATIVE > EPISTEMIC. | ||||

The domain/frame adverbial, siyaasiyyan ‘politically’ tends to be higher than modal adverbial rubbamaa ‘maybe’, although they together constitute a single class of higher adverbials, as in (74).

Previous studies encountered theoretical problems in accounting for such a rigid distribution, as the one noted in (71). In cartographic theories (see, for example, Cinque (1999)), adverbials of all types have a fixed universal hierarchy as they are base-generated as specifiers of functional heads with a single position. In those instances where the same adverbial can appear in two different phases, such as ɣaaliban ‘often’ in (75) and (76), while these theories suggest the movement of heads around the adverbs or multiple positions of the same adverb, this study argued that its position is determined by the semantic scope and modification domain the adverbial.

| (75) | ɣaaliban | – maa | takuun | l-ʔawDaaʕ | ɣayru | mustaqirrat-in. |

| often | -that | is | the-situation | not | stable-Gen | |

| “It is often that the situation is unstable.” | ||||||

| (76) | ta-murru | ɣaalib-an | bi-jaara-t-ha. | |||

| she.pass | often-Acc | by-neighbour-Fem-her | ||||

| “She often passes by her neighbour.” | ||||||

The adverbial ɣaaliban ‘often’ appears in different positions and, eventually, with different meanings. In (75), ɣaaliban ‘often’ together with –maa ‘that’ is a discourse-oriented modifier, modifying the overall proposition, thus attached to a clause-initial position; the CP layer. While the indefinite form of ɣaaliban in (76), has a subject-oriented interpretation and modifies the vP phase. In this particular regard, it is reasonable to assume the –maa ‘that’ in Arabic functions as a focused morpheme when attached to some degree adverbials. Therefore, it is natural to conclude that the semantic scope and the modification domain of the adverbials in Arabic partially regulate their distribution.

7 Conclusion

Adverbs and adverbials in Arabic are flexible linguistic expressions that appear in the sentence-final position, sentence-initial position, or in the middle of a sentence. Their semantic scope and modification domain regulate their distribution. Although the phasal analysis used here correctly accommodates the attachment points of different classes of adverbials, the variations in the semantic properties and the weight (heavy or light) of the scope within the lower class or higher class of adverbials were beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, future studies may test the semantic constraints of adverbial positioning found in Arabic to other languages to find if they follow such restrictions or not.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions. Their comments and suggestions contributed remarkably to the improvement of the current version. All remaining issues are our own responsibility.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education with grant code: FRGS/1/2021/WAB10/UKM/02/2.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. All sections of this manuscript are prepared with contributions from both authors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Abu-Chacra, Faruk. 2007. Arabic: An Essential Grammar. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203088814Suche in Google Scholar

Ackema, Peter. 2015. “Arguments and Adjuncts.” In Syntax – Theory and Analysis: An International Handbook, edited by Tibor Kiss, and Artemis Alexiadou, no. 42, 246–73. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/433702.10.1515/9783110377408.246Suche in Google Scholar

Adger, David. 2010. “A Minimalist Theory of Feature Structure.” In Features: Perspectives on A Key Notion in Linguistics, edited by Anna Kibort and Greville G. Corbett, 185–218. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199577743.003.0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Adger, David. 2003. Core syntax: A Minimalist Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199243709.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Al Aqad, Mohammed. 2013. “Syntactic Analysis of Arabic Adverb’s between Arabic and English: X-bar Theory.” International Journal of Language and Linguistics 1 (3): 70–4. 10.11648/j.ijll.20130103.11.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Bom, Waleed and Marwan Jarrah. 2020. “The Adverb Hierarchy in Jordanian Arabic: A Cinquean Approach.” Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences 47 (1): 590–605. https://archives.ju.edu.jo/index.php/hum/article/view/104083.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Ghamdi, Afnan. 2018. “Hierarchy of Adverbs in Ghamdi Arabic.” PhD diss., California State University, Fresno.Suche in Google Scholar

Alexiadou, Artemis. 1997. Adverb Placement: A Case Study in Antisymmetric Syntax. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamin’s Publishing.10.1075/la.18Suche in Google Scholar

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2004. “Adverbs Across Frameworks.” Lingua 114 (6): 677–82. 10.1016/S0024-3841(03)00047-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Alexiadou, Artemis, T. Alan Hall, and Katalin É. Kiss, eds. 2009. Syntactic, Semantic, and Prosodic Factors Determining the Position of Adverbial Adjuncts. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110214802.bm.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-hawary, Mohammad. 2011. Modern Standard Arabic Grammar: A Learner’s Guide. UK: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Shammiry, Khalaf. 2016. “Adverbs in Saudi Northern Region Dialect of Arabic (SNRDA).” International Journal of English Linguistics 6 (1): 128–41. 10.5539/ijel.v6n1p128.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Shurafa, Nuha Suleiman. 2005. “Word Order, Functions and Morphosyntactic Features of Adverbs and Adverbials in Arabic.” Journal of King Saud University-Arts 18 (2): 85–100. https://arts.ksu.edu.sa/sites/arts.ksu.edu.sa/files/imce_images/v42m334r2586_0.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Stephen. 1972. “How to Get Even.” Language 48 (4): 893–906. 10.2307/411993.Suche in Google Scholar

Anghelescu, Nadia. 2013. “Modalities and Grammaticalization in Arabic.” In Arabic Grammar and Linguistics, edited by Yasir Suleiman, 130–42. London and New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Badawi, El Said, Michael Carter, and Adrian Gully. 2015. Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge.10.4324/9781315856155Suche in Google Scholar

Barbu, Roxana-Maria and Ida Toivonen. 2016. “Arguments and Adjuncts: at the Syntax-Semantics Interface.” Florida Linguistics Papers 3: 13–25. https://journals.flvc.org/floridalinguisticspapers/article/view/92469.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Archna. 2006. “Testing Cinque’s Hierarchy: Adverb Placement in Hindi.” Proceedings of the Workshop in General Linguistics, Vol. 6, 10–25. Linguistics Student Association, University of Wisconsin-Madison.Suche in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 1990. Generalized Verb Movement: Aspects of Verb Syntax. Torino, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier.Suche in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 1994. “Verb Positions: Evidence from Italian.” In Verb Movement, edited by David Lightfoot and Norbert Hornstein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511627705.003Suche in Google Scholar

Bellert, Irena. 1977. “On Semantic and Distributional Properties of Sentential Adverbs.” Linguistic Inquiry 8 (2): 337–51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4177988.Suche in Google Scholar

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2002. “A-Chains at the Pf-Interface: Copies and Covert Movement.” Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 20 (2): 197–267. 10.1023/A:1015059006439.Suche in Google Scholar

Bobaljik, Jonathan David and Dianne Jonas. 1996. “Subject Positions and the Roles of TP.” Linguistic Inquiry 27 (2): 195–236. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4178934.Suche in Google Scholar

Carnie, Andrew. 2021. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Carnie, Andrew, Yosuke Sato, and Daniel Siddiqi, eds. 2014. The Routledge Handbook of Syntax. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315796604Suche in Google Scholar

Carnie, Andrew and Andrew Barss. 2006. “Phases and Nominal Interpretation.” Research in Language (4): 127–32.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1991. “Some Notes on Economy of Derivation and Representation.” In Principles and Parameters in Comparative Grammar, edited by Robert Freidin, 417–54. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1998. “Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework.” In Step by Step: Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honor of Howard Lasnik Martin, edited by Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511811937Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. “Derivation by Phase.” In Ken Hale: A Life in Language, edited by M. Kenstowicz, 1–54. Cambridge: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4056.003.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. “Beyond Explanatory Adequacy.” In Structures and Beyond: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures, edited by Adriana Belletti, 104–31. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2007. “Approaching UG from Below.” In Interfaces + recursion = Language?: Chomsky’s Minimalism and the View From Syntax-Semantics, edited by Uli Sauerland and Hans-Martin Gärtner, 1–31. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110207552.1Suche in Google Scholar