Abstract

This study reports quantitative findings from a study of 205 Hebrew request for confirmation (RfC) sequences, as part of a comparative Pragmatic Typological project across ten languages. Based on video recordings of casual conversation, this is the first systematic survey of such sequences in Hebrew. We examine linguistic and embodied resources for making an RfC (syntactic and prosodic design; polarity; use of modulation, inference marking, connectives, and tag questions) and for responding to it (response type; use, type, and position of response tokens (RTs); (non)minimal responses; repeat strategies; nodding and headshakes). We find that Hebrew RfCs lack interrogative syntax and are overwhelmingly marked by rising final intonation, frequently marked as inferences, rich in types of connectives and modulators, but infrequently feature tag questions. In responses to RfCs, Hebrew presents a comparatively high rate of disconfirmation, which is often also relatively unmitigated, corroborating Linguistic Anthropological descriptions of Hebrew conversational style. RTs are used in over half of responses, while full repeats are relatively rare. Occasionally, nods and headshakes are found unaccompanied by speech, as exclusively embodied responses. We expand on two negating RTs: the dental click (an areal feature) and the forceful ma pit'om ‘of course not’ (lit. ‘what suddenly’).

1 Introduction

This study surveys request for confirmation (RfC) sequences in Hebrew, analyzing 205 requests and responses in casual spoken Hebrew conversation. As described in the introduction to this special issue (König and Pfeiffer forthcoming), RfCs are turns that introduce a proposition and make (dis)confirmation by another participant relevant. They manifest a relatively flat, recipient-tilted epistemic gradient (Heritage and Raymond 2012, 180), in which the speaker claims partial knowledge concerning the confirmable but treats the addressee as having better access or more rights to knowledge about the matter at hand.

In Section 2, we review previous studies related to Hebrew RfC sequences. Section 3 presents our data. Section 4 surveys the linguistic resources used to build RfCs, whereas Section 5 outlines the linguistic resources used to build responses to these requests. The analyses follow the guidelines provided for all articles in this Special Issue (König and Pfeiffer forthcoming) and highlight what is particular to Hebrew RfC sequences from a comparative perspective, in light of the nine other languages investigated in the larger project of which this study is a part. Section 6 summarizes the main findings and discusses possibilities for future research on Hebrew RfCs.

2 Literature review

This is the first dedicated study of Hebrew RfCs. We know of only one published study of Hebrew polar interrogative forms based on spoken data, which is Cohen’s (2004, 2009) description of the intonation of interrogatives in a small corpus of spontaneous spoken interaction. She describes the use of rising final intonation as the main formal characteristic[1] of Hebrew polar interrogatives.[2]

The earliest effort to describe the usage of interrogatives in Hebrew based on interactional principles was the pioneering study by Du-Nour (1987, Sections 3.3.1 and 4.2.4), who dealt briefly with both polar interrogatives and tag questions. However, Du-Nour’s description was based on the representation of dialogue in plays. Burstein (2021) is a general survey of questions and answers in written Hebrew, but the analysis there is primarily syntactic, and not based on interactional linguistic principles. Even more so than Du-Nour’s work, the relation between Burstein’s data and spoken language is complicated, since her sources include high-register fiction alongside journalistic interviews, emulating speech to different degrees (ibid., 17). We will therefore briefly present Burstein’s and Du-Nour’s main findings related to RfCs below, where relevant, and compare them to our spoken data findings.

There are several studies concerning particles that are central to the design of Hebrew polar questions and their responses, and therefore significant for the description of RfCs, as response tokens (RTs, Section 5.2) and/or tag questions (Section 4.6). Miller Shapiro (2012) and Maschler and Miller Shapiro (2016) describe the uses of naxon ‘right’ as both RT and tag, and how these uses have grammaticized from the original verbal meaning, ‘to be established, strong, ready’. Michalovich and Netz (2018) describe the use of naxon as a tag in the classroom. Shor (2018, 2020) describes the use of lo ‘no’ as an RT and tag question. Ben-Moshe and Maschler (forthcoming) describe the use of dental clicks as RTs. Bardenstein (2020, 77–9) describes the development of ma pit'om (lit. ‘what suddenly’) from a rhetorical question into an exclamation of strong disagreement. Inbar (2021, 408–9) discusses the use of 'o mašehu ‘or something’, which may be used as a tag question. Miller (2010) studied the epistemic uses of repetition in Hebrew talk-in-interaction, which bears upon its use in responses to RfCs.

All of these constructions are described as part of wider research projects, and not specifically in RfCs. In what follows, we refer to these studies, and others, when relevant in the analysis sections. The only study contrasting several forms in a paradigm is Greenberg and Wolf’s (2019) study of ken ‘yes’, naxon ‘right’, and legamrey ‘totally’ as RTs; however, their approach is entirely introspective, and not useful for our purposes.

3 Description of dataset

The data for this study were selected from the Haifa Multimodal Corpus of Spoken Hebrew (Maschler et al. 2023), which consists of video recordings of adult native speakers of Hebrew, in casual conversation among friends and family. This is a dynamic corpus, currently composed of over 20 h of transcribed video; we used a small part in order to collect 205 tokens of RfC sequences, which we then coded according to the guidelines of the larger comparative project (König et al. forthcoming). In total, we reviewed 2:44 h from 11 different recordings. The median recording provided 17 examples over 12:13 min. The collection involved 32 participants in total, 2–6 per recording. The recordings used were made in the years 2016–2019.

The data were transcribed and segmented into intonation units (Chafe 1994), following Du Bois et al. (1992) and Du Bois (unpublished manuscript 2012), as adapted for Hebrew (Maschler 2017). Each numbered line in the excerpts below represents an intonation unit. Multimodal transcription generally follows Mondada (2019). Further information about transcription conventions is found in the Appendix.

We collected our Hebrew examples by looking for instances of the type of action defined above – introducing a proposition and making (dis)confirmation by another participant relevant – regardless of the formal characteristics of the turn implementing it. For example, our collection includes RfCs that are not marked as questions by their intonation contour but exhibit the interactional structure we looked for. Note, however, that RfCs may also serve as ‘vehicles’ for implementing additional actions, such as proposing a course of action, or raising a new topic (König et al. forthcoming). RfC sequences were analyzed following the methodology of Interactional Linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018).

4 Resources for requesting confirmation in Hebrew

4.1 Syntactic design

The syntactic design of a Hebrew RfC predominantly consists of a finite clause (N = 153; 75%). Phrases (N = 48; 23%) are much less common (Table 1). The great majority of RfCs (N = 144; 70%) consist of simple independent clauses; 9 (4%) consist of subordinate clauses, mostly causal or temporal adverbial clauses (Excerpt 6 ‘False Self’ below); 2 more (1%) manifest non-finite verbs, namely infinitival phrases.[3]

Syntactic design of RfCs in Hebrew

| Syntactic complexity | N (% of RfCs) |

|---|---|

| Independent clause | 144 (70%) |

| Phrase | 48 (23%) |

| Subordinate clause | 9 (4%) |

| Non-finite verb phrase | 2 (1%) |

| Other | 2 (1%) |

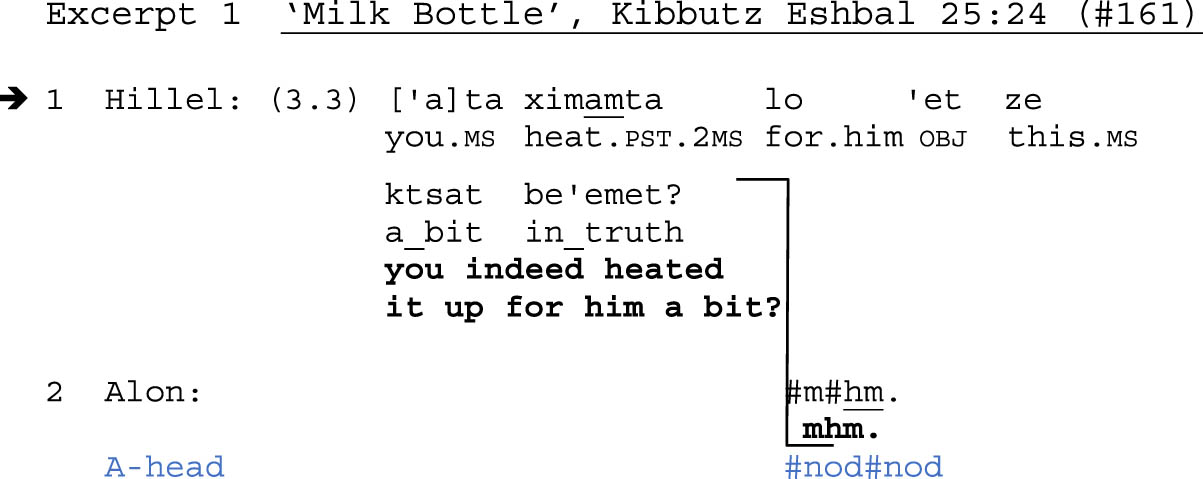

Excerpt 1 ‘Milk Bottle’ illustrates an RfC consisting of a simple independent clause. Preceding this excerpt, Alon and Hillel, a gay couple, have been wondering whether their baby is hungry, and whether to heat up a bottle for him. Some moments later, Alon, having returned from the kitchen with a bottle of milk for the baby, is feeding the baby, and Hillel asks him whether he had indeed heated up the milk:

Hillel’s RfC 'ata ximamta lo 'et ze ktsat be'emet? ‘you indeed heated it up for him a bit?’ consists of a simple independent clause. Hebrew is generally an SVO language (but see Auer and Maschler 2013), and yes–no interrogatives are not distinguished by a characteristic word order. The interrogative is communicated here solely via the rising intonation. The modulator be'emet (Section 4.3), which might be translated here by ‘indeed’, refers back to the men’s preceding debate concerning whether or not to go heat up the bottle, ratifying their previous stance (Maschler and Estlein 2008) of planning to do so.

A phrasal RfC is illustrated in Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’. Eyal is explaining to his friend Mika how to prepare a curry sauce. Mika wants to know specifically what spices he adds:

When Eyal lists ‘ginger’ as one of the ingredients (l. 204), Mika requests confirmation concerning the type of ginger he uses via the noun phrase jinjer t 'e‐‐h taxun? ‘g u‐‐h ground ginger?’ followed by the conjunction 'o ‘or’ (l. 206–209); this can be understood as a tag question (Section 4.6), or as the beginning of an alternative, such as ‘grated ginger’. Due to the overlap with Eyal’s embodied and verbal response (l. 210), there is no way of telling which interpretation was originally intended. In fact, even if she did intend to produce an alternative, Mika may have adapted her construction to the needs of the interaction, recasting it into another RfC shortly thereafter (l. 211). The first RfC is answered in the negative, while Eyal depicts the correct answer with his hands (l. 210); the second is answered by Eyal’s nod (l. 211).

Hebrew adjectives follow the noun they modify: Mika’s noun phrase is produced incrementally here, the disfluencies t and 'e‐‐h ‘u‐‐h’ (l. 206–207) attesting the cognitive difficulties involved in searching for the adjective taxun ‘ground’ (Chafe 1994). Phrasal RfCs in our data generally accomplish understanding checks, clarification requests or, as here, requests for further elaboration. The majority constitute prepositional phrases (20) or noun phrases (16), as in Excerpt 2; fewer constitute adjectival phrases (7) or adverbial phrases (5).

4.2 Polarity

The polarity of Hebrew RfCs is overwhelmingly positive (N = 177; 86%), as seen, for example, in Excerpts 1 ‘Milk Bottle’ and 2 ‘Curry Spices’. Negative polarity is far less frequent (N = 28; 14%) and is expressed in Hebrew predominantly via the negator lo ‘no’ (N = 26; cf. Glinert 1989, 271; see examples in Excerpts 8 ‘Wrapping Up’ and 12 ‘Bitter’ below). The negative existential 'en ‘there isn’t’ is used twice throughout our data, and the negator 'i is used once, as part of the construction 'i 'efshar ‘not possible’ (cf. Shor 2020, Section 3).

As in several other languages compared in this project, such as English (Heritage 2002) and German (Deppermann et al. 2024), some negatively formatted Hebrew RfCs are not treated as suggesting a negative-polarity confirmable; instead, participants treat them as suggesting the corresponding positive-polarity confirmable. In such cases, we interpret the negation as a form of modulation, signaling matters of epistemic stance – either increased (Heritage 2002) or decreased certainty (Koshik 2002). This is the case in a majority (N = 19; 68%) of negative-polarity RfCs in our collection.[4] This will be further discussed in Section 5.2.1 ‘Responses to negative-polarity RfCs’.

4.3 Modulation

The category of modulation involves the lexical, morphological, and syntactic resources that the person making an RfC uses in order to position themselves vis-à-vis the assumed validity of the confirmable – whether mitigating, reinforcing, or taking some other epistemic stance regarding the confirmable. Forty-one RfC tokens (20% of all RfCs) involve some sort of modulation, which places Hebrew near the middle in comparison to the nine other languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). The variety of Hebrew RfC modulators is great, as shown in Table 2, consisting mostly of negation, epistemic verb phrases[5] – first- or second-person forms of mental or perception verbs (e.g., know, think, understand, consider, assume, and worry) – adverbs, and particles. These resources express mostly certainty, doubt, or possibility. Resources were sometimes employed in conjunction with another modulation resource; each component was counted separately.

Modulators in Hebrew RfCs

| Grammatical form | N (% of modu- lated RfCs) | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Negation | 19 (46%) | lo ‘neg’ 18, 'i ('efshar) ‘not (possible)’ 1 |

| Epistemic verb phrase | 9 (22%) | 'at betuxa še- ‘[are] you sure [f] that’ 1, 'ata lo do'eg še- ‘[are] you not worried [m] that’ 1, 'ata yodea ‘you know [m]’ 1, hevanti ‘I understood’ 1, lo yoda'at ‘I dunno [f]’ 1, nagid ‘let’s say’ 2, taxshov še- … naniax … nagid hipotetit ‘consider that … let’s assume … let’s say hypothetically’ 1, xashavti ‘I thought’ 1 |

| Adverb | 8 (20%) | 'ulay ‘perhaps’ 2, be'emet ‘really, indeed’ 2, be'etsem ‘in fact’ 1, betax ‘surely’ 1, nagid hipotetit ‘let’s say hypothetically’ 1, siryesli ‘seriously’ 1 |

| Particle | 7 (17%) | kaze ‘sort of’ 5, kaze, ve-ze, ‘sort of and all that’ 1, ke'ilu ‘like’ 1 |

| Other | 6 (15%) | 'im conditional clause 1, ('i) 'efshar ‘(not) possible’ 1, hayta 'amura ‘was supposed to [f]’ 1, rov hasikuyim ‘most likely’ [lit. ‘most chances’] 1, vedvarim ka'ele ‘and things like that’ 1, passive verbal pattern (nif'al) indicating possibility (nimrax ‘smearable, might smear’) 1 |

Negation in negative polarity RfCs (Section 5.2.1) is the most common form of modulation (N = 19, 46% of modulated RfCs), indicating epistemic stance. Negation sometimes appears alongside other means of modulation.

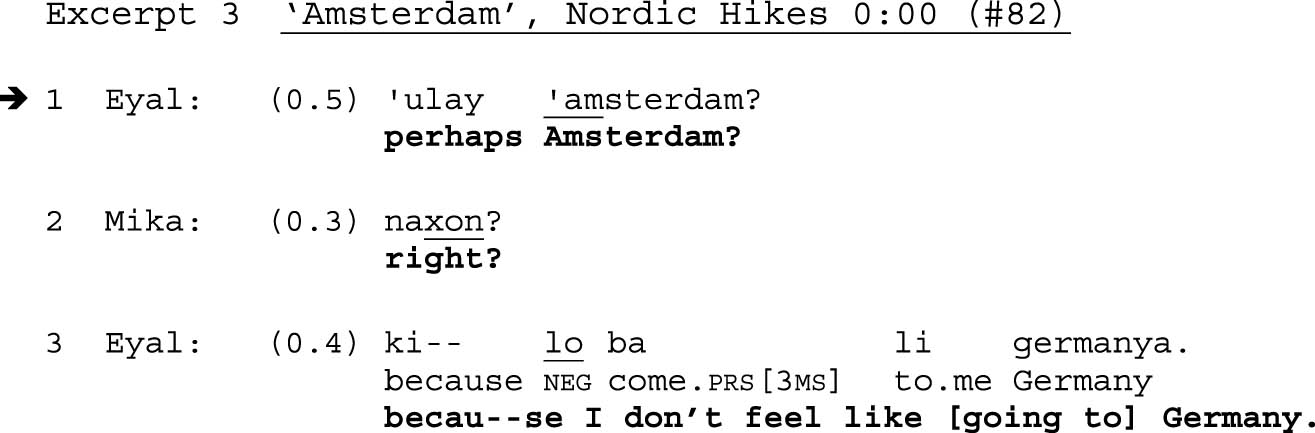

Other than the negator lo ‘no’ and the hedge kaze ‘like’ (lit. ‘like this’; Ziv 1998, Henkin 1999, Maschler 2001), most modulators are found only once or twice throughout our collection. An example of another hedge, ke’ilu ‘like’ (lit. ‘as if’, Maschler 2002), is shown in Excerpt 12 ‘Bitter’ below. As for adverbial modulators, we have seen an example involving the epistemic adverb be'emet ‘indeed’ in Excerpt 1 ‘Milk Bottle’. An example of 'ulay ‘perhaps’ is given in Excerpt 3 ‘Amsterdam’, in which Eyal and Mika are talking about possible places to move to in Europe. Mika’s partner has been living in Amsterdam for the past several years, and so she often goes there:

Eyal’s 'ulay 'amsterdam? ‘perhaps Amsterdam?’ requests confirmation concerning whether his moving to Amsterdam with his partner is a good idea. According to Livnat (2001, Section 3.2.2), 'ulay can convey deontic modality, thus marking this RfC as a suggestion. Recall, however, that it is not Mika who will go there, but rather Eyal – Eyal is not asking her to accept, but to confirm whether Amsterdam is a good choice, since she has first-hand experience. She indeed confirms with the RT naxon? ‘right?’ (Section 5.2). Mika’s use of rising intonation in the RT is unusual (Section 5.2) and a fairly new development in Hebrew. It assigns this confirmation RT an additional function – that of an appeal (Du Bois et al. 1992), inviting Eyal to agree in turn with the confirmable that he himself has put forward. Eyal replies with a reason to prefer Amsterdam – he doesn’t feel like moving to Germany (l. 3).

Another adverbial modulator, the borrowed siryesli ‘seriously’, can be seen in Excerpt 13 ‘Divorce Karma’.

4.4 Inference marking

Speakers sometimes present confirmables as inferences from prior talk. However, in only 19% of the cases (N = 39), they deploy a specific lexical resource for marking the inference. This places Hebrew closer to the upper range among the 10 languages investigated in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). The inventory of inference markers is given in Table 3. Inference markers occasionally appear in clusters; each component in the cluster was counted separately.[6]

Inference markers in Hebrew RfCs

| Inference marker | N (% of RfCs marked as inferences) | Variants and clusters |

|---|---|---|

| 'ah ‘oh’ | 14 (36%) | 'ah. 1, 'ah, 10, 'ah ken, ‘oh yes,’ 1, 'ah, 'oy va'avoy. ‘oh, oh no.’ 1, prosodically integrated 1 |

| 'az ‘so, then’ | 12 (31%) | 'az, 1, 'az ma? ‘so what?’ 2, ve-'az ‘and then’ 2, ve-'az ma? ‘and then what’ 1, prosodically integrated 6 |

| ke'ilu ‘like’ | 7 (18%) | ke'ilu, 2, maztomeret? ke'ilu ‘what do you mean? like’ 1, prosodically integrated 4 |

| 'amar ‘to say’ | 3 (8%) | 'ata 'omer ‘you’re saying [m]’ 1, 'at 'omeret. ‘you’re saying. [f]’ 1, maztomeret? ke'ilu ‘what do you mean? like’ 1 |

| 'oy ‘oh no’ | 2 (5%) | 'oy, 1, 'ah, 'oy va’avoy. ‘oh, oh no.’ 1 |

| zehu ‘that’s it’ | 2 (5%) | zehu, 1, zehu? 1 |

| 'okey ‘okay’ | 1 (3%) | 'okey, 1 |

| ken ‘yes’ | 1 (3%) | 'ah ken, ‘oh yes,’ 1 |

We illustrate the three most frequent inference markers in our database, 'ah ‘oh’, 'az ‘so’, and ke'ilu ‘like’.

The most frequent inference marker (N = 14; 36% of RfCs marked as inferences) is the change-of-state token (Heritage 1984) 'ah, the Hebrew ‘equivalent’ of English oh (Maschler 1994). Hebrew has a diverse inventory of change-of-state tokens (Ben-Moshe 2022), but 'ah is the most common and unmarked one (the others generally marking some accompanying affective stance, like 'oy ‘oh no’, which appears twice in our collection). In Excerpt 4 ‘Japanese Duolingo’, Dotan has been complaining to Alex about the difficulty of learning the Japanese writing system:

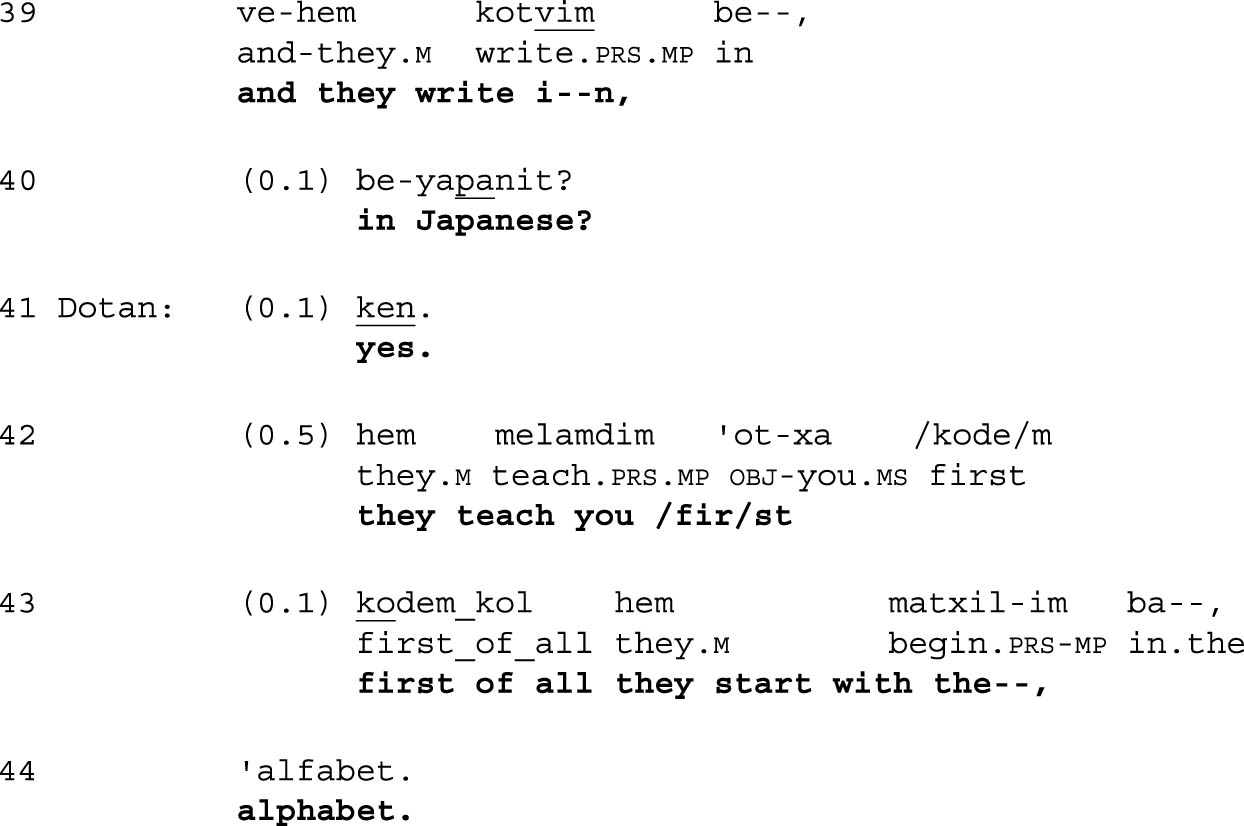

Alex suggests that Dotan learn to speak before he learns to read (l. 33–34), but Dotan explains that ‘tha‐‐t’s, [the way it’s done on] Duolingo.’ (l. 35–36). Following a long pause, Alex first acknowledges this (l. 37) and after another long pause asks Dotan to confirm his understanding that Duolingo lessons employ Japanese orthography with ve-hem kotvim be‐‐, be-yapanit? ‘and they write i‐‐n, in Japanese?’ (l. 38–40), and Dotan confirms (l. 41–44). Alex’s RfC is prefaced by 'ah (l. 38), a change-of-state token, introducing the confirmable as recently inferred from Dotan’s immediately prior utterance (l. 35–36). Another example of 'ah can be seen in Excerpt 14 ‘Surprise Party’ below.

The second most frequent inference marker in our collection (N = 12; 31%) is Hebrew 'az ‘then/so’, a temporal adverb which may also be deployed as a conjunction and a discourse marker (Maschler 1994, 1997, Yatziv and Livnat 2007, Livnat 2009, cf. Schiffrin 1987 for English then). Excerpt 5 ‘Black Speck’ is taken from a family dinner. Dad is telling the rest of the family about an incident that happened at his new workplace, a quality control lab at a sugar factory. The lab workers are investigating a complaint from a baby formula manufacturer, who had purchased some sugar from the factory and found black specks in it. Our excerpt begins as Dad is describing one of the workers indeed finding a black speck in the sugar:

While Dad describes the finding of the speck (l. 38–41), Mom displays engagement by opening her eyes wide (l. 39) and leaning forward (l. 41). Dad takes over a second to continue his telling, though during this time he gestures with his left hand in a way that projects further talk (l. 42–43). In overlap with Dad’s specification that it was a single speck (l. 43), Mom attempts to provide the continuation of the story herself in the form of an RfC – 'az lakaxtem 'oto? ‘so you took it?’ (l. 42) – in another display of engagement.

Mom’s RfC is prefaced by the discourse marker 'az ‘so’, introducing the next narrative action as deduced from the previous one (Maschler 1994, 338). Dad does not confirm the RfC, but he does align with Mom’s action of continuing the story by moving on to the next narrative event, as reflected by his echoing of 'az within the discourse marker cluster ve-'az ‘and then’ (l. 44–45).

The third most frequent inference marker found in our database (N = 7; 18%) is the discourse marker ke'ilu ‘like’ (Maschler 2002, 2009). Excerpt 6 ‘False Self’ begins with Hilla asking Gaya for clarification of a term she has just used, 'išiyut kozevet ‘false self’:

Gaya attempts to clarify the concept by giving the example of Omer’s brother, who apparently always tries ‘to please everyone’, not letting his true self ‘come out’ (l. 3–4, 6–10). Gaya begins an account with ki ‘because’ (l. 11), but Hilla interrupts requesting confirmation by rephrasing Gaya’s explanation: ke'ilu, še-'en lexa 'išiyut. ‘like, you don’t have a self.’ (l. 12–13). The discourse marker ke'ilu here projects the following discourse as a rephrasal (Maschler 2002) inferred from the preceding talk, reusing the term 'išiyut ‘persona, self’. Gaya confirms this rephrasal (l. 14). This is also an example of an RfC involving a formally subordinate clause (Section 4.1) (beginning with the general Hebrew subordinator še- ‘that’, l. 13), which is here employed as an insubordinate (Evans 2007) clause (cf. Maschler 2018, 2020).

4.5 Connectives

Speakers often use a connective device to mark the link of the RfC to the preceding talk. The category of ‘connectives’ is broadly understood here, encompassing conjunctions (e.g., ve- ‘and’, 'az ‘then/so’, 'aval ‘but’, and ki ‘because’) and discourse markers (e.g., ke'ilu ‘like’, 'ah ‘oh’, rega ‘just a moment’, and ma ‘what’), among other resources.[7] Connectives were employed in 41% (N = 83) of RfCs in our collection. This places Hebrew closer to the upper range among the ten languages investigated in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). Table 4 lists the great variety of Hebrew connectives found throughout our database. Connectives commonly appear in clusters (cf. Maschler 1994); each component in the cluster was counted separately.

Inventory of connectives in Hebrew RfCs

| Connective | N (% of connected RfCs) | Variants and clusters |

|---|---|---|

| ve- ‘and’ | 20 (24%) | 'ah, ve- ‘oh, and’ 1, 'az ma? ve- ‘so what? and’ 1, rega, šniya, šniya, 'av[al] … ve- ‘just a moment, just a sec, just a sec, bu[t] … and’ 1, ke'ilu, ve-zehu? ve- ‘like, and that’s it? and’ 1, tsk nu, ve- ‘tsk c’mon, and’ 1, ve-'az ‘and then’ 1, ve-'az gam ‘and then also’ 1, ve-'az ma? ‘and then what?’ 1, ve-ma? ‘and what’ 2, prosodically integrated 10 |

| ma ‘what’ | 17 (21%) | ma, ‘what,’ 1, 'az ma? ‘so what?’ 1, 'az ma? ve- ‘so what? and’ 1, ma 'aval, ‘what but,’ 1, ma, še- ‘what, that’ 1, ve-'az ma? ‘and then what?’ 1, ve-ma, ‘and what,’ 1, ve-ma? ‘and what?’ 1, prosodically integrated 9 |

| 'az ‘so’ | 14 (17%) | 'az, 1, 'ah. 'az ‘oh. so’ 1, 'az basof, ‘so in the end,’ 1, 'az ma? ‘so what?’ 1, 'az ma? ve- ‘so what? and’ 1, kitser, 'az ‘anyway, so’ 1, ve-'az ‘and then’ 1, ve-'az gam ‘and then also’ 1, ve-'az ma? ‘and then what?’ 1, prosodically integrated 5 |

| 'ah ‘oh’ | 14 (17%) | 'ah. 1, 'ah, 6, 'ah. 'az ‘oh. so’ 1, 'ah, 'oy va'avoy. ‘oh, oh no.’ 1, 'ah ken, ‘oh yeah,’ 1, 'ah, ki ‘oh, because’ 1, 'ah, kše- ‘oh, when’ 1, 'ah, ve- ‘oh, and’ 1, prosodically integrated 1 |

| 'aval ‘but’ | 10 (12%) | 'oy, 'aval ‘oh no, but’ 1, 'aval, … tagid li, ‘but, … tell me,’ 1, ma 'aval, ‘what but,’ 1, rega, 'aval ke'ilu ‘just a moment, but like’, rega, šniya, šniya, 'av[al] … ve- ‘just a moment, just a sec, just a sec, bu[t] … and’ 1, prosodically integrated 5, turn-final 1 |

| ke'ilu ‘like’ | 8 (10%) | ke'ilu, 1, ke'ilu, ve-zehu? ve- ‘like, and that’s it?, and’ 1, ke'ilu, še- ‘like, that’ 1, maztomeret? ke'ilu ‘what do you mean? like’ 1, rega, 'aval ke'ilu ‘just a moment, but like’ 1, prosodically integrated 3 |

| rega ‘just a moment’ | 7 (8%) | rega, 5, rega, 'aval ke'ilu ‘just a moment, but like’ 1, rega, šniya šniya, 'av[al] … ve- ‘just a moment, just a sec, just a sec, bu[t] … and’ 1 |

| ki ‘because’ | 3 (4%) | 'ah, ki ‘oh, because’ 1, prosodically integrated 2 |

| še- ‘that’ | 3 (4%) | ma, še- ‘what, that’ 1, ke'ilu, še- ‘like, that’ 1, prosodically integrated 1 |

| 'oy ‘oh no’ | 2 (2%) | 'ah, 'oy va'avoy ‘oh, oh no’ 1, 'oy, 'aval ‘oh no, but’ 1 |

| zehu ‘that’s it’ | 2 (2%) | zehu, 1, ke'ilu, ve-zehu? ve- ‘like, and that’s it?, and’ 1 |

| 'okey ‘okay’ | 1 (1%) | ‘okey, 1 |

| basof ‘in the end’ | 1 (1%) | 'az basof, ‘so in the end,’ 1 |

| hey ‘hey’ | 1 (1%) | hey, 1 |

| ken ‘yeah’ | 1 (1%) | 'ah ken, ‘oh yeah,’ 1 |

| kitser ‘anyway’ | 1 (1%) | kitser, 'az ‘anyway, so’ 1 |

| kše- ‘when’ | 1 (1%) | 'ah, kše- ‘oh, when’ 1 |

| lo ‘no’ | 1 (1%) | lo, 1 |

| m‐‐ ‘mm’ | 1 (1%) | m‐‐. 1 |

| šniya ‘just a sec’ | 1 (1%) | rega, šniya, šniya, 'av[al] … ve- ‘just a moment, just a sec, just a sec, bu[t] … and’ 1 |

| tagid li ‘tell me’ | 1 (1%) | 'aval, … tagid li, ‘but, … tell me,’ |

| maztomeret? ‘what do you mean?’ | 1 (1%) | maztomeret? ke'ilu ‘what do you mean? like’ 1 |

We have already seen an example of the most frequent connective in the Hebrew collection, ve- ‘and’ (N = 20, 24% of all RfCs manifesting connectives) in Excerpt 4 ‘Japanese Duolingo’. Following the realization that his interlocutor is learning Japanese on Duolingo, marked by the inference marker 'ah, the speaker adds the RfC ve-hem kotvim be‐‐, be-yapanit? ‘and they write i‐‐n, in Japanese?’ (l. 38–40). The maximally general conjunction ve- is employed as a discourse marker here, adding the following action – in this case, an RfC – in the least marked way (Maschler 1994). It is therefore not surprising that ve- is the most frequent connective in our data. In this particular instance, it also functions much like the English and-preface (Bolden 2010), making an RfC by offering a candidate understanding of the addressee’s preceding informing turn and articulating a ‘missing’ element of that turn.

We have also seen examples of the connectives 'az ‘then/so’ (Excerpt 5 ‘Black Speck’), ke'ilu ‘like’ (Excerpt 6 ‘False Self’), and še- ‘that’ (Excerpt 6 ‘False Self’). The second most frequent Hebrew connective in our collection is the discourse marker ma ‘what’ (N = 17, 21%), which has been analyzed as “pointing out a potential inconsistency between incoming information and (assumed) shared knowledge” (Ziv 2008, 356), or as expressing “an evaluation of some currently salient discourse representation as incredible” (Ariel 2010, 194). Prefacing polar questions, it has been shown to mark amazement (Maschler 1997) or ‘incredulity’ (Lambrecht 1990), and to request confirmation of a suggested clarification (Maschler and Nir 2014, 546) when employed in final high-rising intonation (Matalon 2023, forthcoming). In Excerpt 7 ‘Just Visiting’, a conversation among five women in their sixties, Shula has been telling about her cousin who is visiting Israel from the USA after a 50-year absence:

Noa tells her friends that her cousin has arrived after a 50-year absence and is returning to the USA next week (l. 1–3). The final intonation contour of this segment is level, indicating that Noa is not done, and the others let her have the floor, but she delays for over a second (l. 4). At this point, Shula steps in and requests confirmation concerning whether the cousin has come ‘only for a visit’ ma, hi ba'a rak lebikur? ‘what, she came only for a visit?’ (l. 5–6). This is a request for clarification, but it carries an implied expectation marked by rak ‘only’, that following such a long absence, a person would come for more than ‘just a visit’, perhaps for a longer stretch of time. Indeed, Noa responds that she has come for a visit and also to see her very sick mother (l. 7–12). The incompatibility with Shula’s expectations (Ziv 2006, Ariel 2010, Section 7.4) is additionally marked by ma, also expressing the speaker’s incredulity or amazement (Maschler 1997; Maschler and Nir 2014).

4.6 Tag questions

Hebrew employs tags relatively infrequently (N = 22; 11%) compared to the nine other languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). Only Korean and Yurakaré manifest a lower frequency of tags than Hebrew. Hebrew tags are generally not integrated prosodically into the intonation unit constituting the RfC, with only a single case showing prosodic integration. The inventory of Hebrew tags is given in Table 5.

Inventory of tag questions

| Tag | N (% of tags) | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| naxon ‘right’ | 8 (36%) | naxon? 8 |

| lo ‘no’ | 6 (27%) | lo? 6 |

| 'o ‘or’ | 4 (18%) | 'o, 1, 'o ma. ‘or what.’ 1, 'o mashehu? ‘or something?’ 1, 'o mashehu kaze? ‘or something like that?’ 1 |

| ken ‘yes’ | 3 (14%) | ken. 1, ken? 2 |

| betax ‘surely’ | 1 (5%) | betax? 1 |

| Total | 22 (100%) |

Most Hebrew tags consist of lexemes which may also be employed as RTs (Section 5.2), three of them positive (naxon ‘right’, ken ‘yes’, and betax ‘surely’), and one negative (lo ‘no’). A third variety consists of the conjunction 'o ‘or’ (Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’, l. 209), often in combination with another item (ma ‘what’, mashehu ‘something’, mashehu kaze ‘something like that’). Inbar (2021, 408–9) discusses the use of 'o mašehu ‘or something’ as a marker of hedging and uncertainty, though she does not differentiate between its use in tag questions and elsewhere as a general extender (Overstreet and Yule 2021).[8] There are probably differences of meaning between the different tags beginning with 'o, but additional data are required to make reliable generalizations.

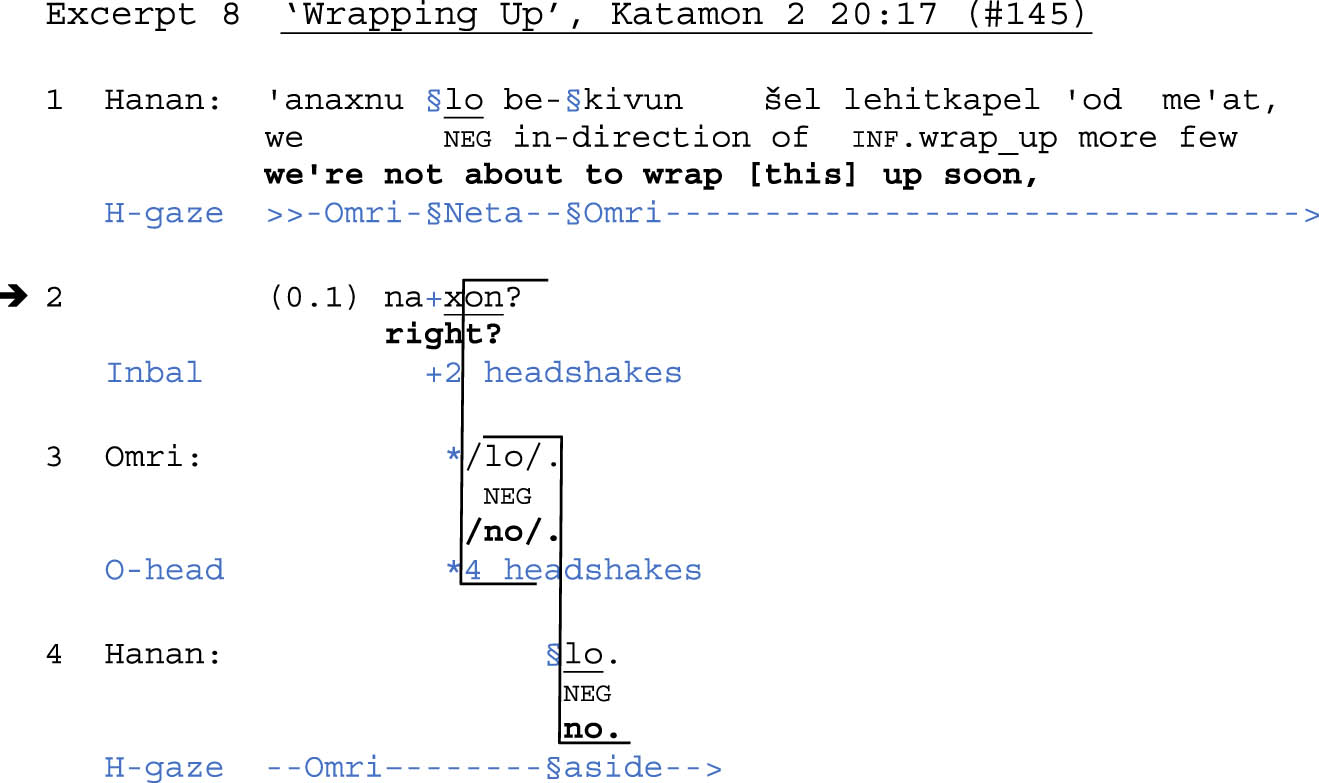

In what follows, we illustrate the two most common Hebrew tags – naxon ‘right’ and lo ‘no’. The most common tag is naxon, as illustrated in Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’, a get-together among five friends, in which Hanan is on the phone with his wife, who is planning to come over. Hanan is making sure that the evening isn’t about to end before she arrives (or shortly thereafter). It is the two hosts, Inbal and Omri, who reply to his question. The two other guests, Ya’ir and Neta, are engaged in an overlapping exchange, which is omitted from this transcription.

Gazing at Omri while on the phone with his wife, Hanan produces an RfC: 'anaxnu lo be-kivun šel lehitkapel 'od me’at, ‘we’re not about to wrap [this] up soon,’ (l. 1) in level intonation, followed by the tag naxon? ‘right?’ (l. 2). In this genre of casual conversation among friends, tag naxon? (Miller Shapiro 2012, Maschler and Miller Shapiro 2016) indexes the speaker’s epistemic stance of uncertainty, thereby establishing Omri, the gaze-selected recipient (Auer 2018), as the epistemic authority on the matter (Heritage 2002, Heritage and Raymond 2005). As hosts, the epistemic gradient is indeed tilted toward Inbal and Omri in the first place in the matter at hand. Inbal confirms this negative polarity RfC via two headshakes in overlap with the final vowel of the tag (l. 2). Her choice of a non-verbal response may be influenced by her not being selected by Hanan’s gaze, and by her mouth being full at the moment. Omri likewise confirms, almost simultaneously with her, with the response particle lo ‘no’ accompanied by four headshakes (l. 3), upon which Hanan breaks eye contact and reports the answer to his wife on the phone (l. 4).

The second most frequent tag is lo? ‘no?’. In contrast to naxon?, which may follow both positive- and negative-polarity RfCs, Burstein (2021, 361) observed that tag lo? appeared in her corpus of written Hebrew always following questions of positive polarity. The six tokens in our collection all follow positive polarity RfCs as well, as in Excerpt 9 ‘Winter Break’, in which Mika is suggesting that Eyal and his partner take a vacation in Amsterdam (in continuation of Excerpt 3 ‘Amsterdam’ above):

Mika suggests that Eyal and his partner buy flight tickets to Amsterdam for the semester break (l. 38–39), which in Israel generally begins in January. Eyal pauses and looks up, displaying a ‘thinking face’ (Harness Goodwin and Goodwin 1986), and then rejects the suggestion with a lo ‘no’ (l. 40), providing an account (Pomerantz 1984, Sacks 1987, Robinson 2016, Inbar and Maschler 2023): 'aval 'az ze xoref. ‘but then it’s winter.’ (l. 41). Apparently, visiting Northern Europe in the winter does not seem attractive to Eyal. After a pause of a full second, Eyal’s assertion is confirmed by Mika with a naxon ‘right’ (l. 42). Almost simultaneously with the beginning of Mika’s delayed response, in pursuit of response (Jefferson 1981), Eyal transforms his account (l. 41) into an RfC by adding the tag lo? ‘no?’ (l. 43) (cf. Miller 2010, 56, Shor 2019, 145), and Mika reconfirms with a ken ‘yes’ (l. 44). The nuances expressed by the choice of lo? rather than naxon? await further study.

This is the only case in our collection where the tag is used to transform a previous action into an RfC. As discussed below, it was more common to find tags as part of the original design of the turn, as seen in Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’. However, we have two more cases of tag questions following a pause longer than 0.1 s, in both of which the tag likewise functions to pursue a response.

4.7 Prosodic design

Hebrew RfCs are overwhelmingly produced with rising final intonation (N = 165; 81%), which is the main formal characteristic of polar questions in spoken Hebrew (Glinert 1989, 270–1, Cohen 2009, 41, Burstein 2021, 57–8). This is likely related to the lack of syntactic or lexical marking of most interrogatives in Hebrew[9] (cf. Section 4.1). Indeed, Hebrew has a higher percentage of rising intonation in the confirmable than any other language surveyed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). In this respect, Korean is the most similar to Hebrew among the languages compared. Examples can be seen in Excerpts 1–5, 7. This finding supports Ozerov’s (2019) suggestion that prosody marks Hebrew interrogatives in general rather than lexical means, in a way that is not typical in other languages.

RfCs produced in falling intonation (N = 21; 10%) are primarily rephrasals or candidate understandings of the preceding utterance (Excerpt 6 ‘False Self’, and Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’, l. 211). Level intonation (N = 16; 8%), on the other hand, is almost exclusively found before tags. Out of 22 tags throughout our database, only one is integrated into the intonation unit of the confirmable. Table 6 presents the prosodic design of all confirmables, of confirmables before a non-integrated tag, and of the non-integrated tags.

Prosodic design

| Final intonation contour | Confirmable (% of RfCs) | Confirmable before non-integrated tag (% of non-int. tags) | Non-integrated tag (% of non-int. tags) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rise | 165 (81%) | 7 (33%) | 18 (86%) |

| Fall | 21 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

| Level | 16 (8%) | 13 (62%) | 1 (5%) |

| Truncated | 3 (2%) | — | — |

| Total | 205 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 21 (100%) |

The final intonation of tags follows the same trends as that of RfCs in general – both are typically produced with rising intonation (86 and 81%, respectively). Non-integrated tags are most commonly (N = 13; 62% of non-integrated tags) found following level intonation, which indicates simply that the turn is not complete at the end of the confirmable, but rather the tag is part of its design, as seen in Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’. The single case of falling intonation before a tag (5%) was shown in Excerpt 9 ‘Winter Break’, in which the original turn is not designed as an RfC, and the tag recompletes the turn and retroactively transforms it into an RfC. Tags following a confirmable produced in rising intonation (N = 7; 33%) seem to be similar to the one following falling intonation, in that they constitute recompletions – though in this case, of a preceding turn designed already as an RfC. Regardless of the intonation contour of the confirmable, however, in most cases (N = 17; 77%), there was no intervening pause whatsoever between the confirmable and the tag.

5 Resources for responses to RfCs in Hebrew

5.1 (Dis)Confirmation

Hebrew RfCs are rarely left unresponded (N = 7; 3% of all RfCs; e.g., Excerpt 10 ‘Mamma Mia’, l. 3 below). The following sections will thus be based on the 198 RfC tokens (97%) that did receive a response. The responses provided are most often confirmations (N = 91; 46% of responses). Both of these findings are in line with the figures found for the other nine languages in this project, as well as with general cross-linguistic trends (Stivers 2022, 16, 18). However, the rate of confirmation in Hebrew is the lowest among all the languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). In Hebrew, the rate of responses that neither confirm nor disconfirm (N = 44; 22%, as in Excerpts 5 ‘Black Speck’ and 7 ‘Just Visiting’) is closer to the upper range compared to the other nine languages. Significantly, Hebrew manifests the highest rate of disconfirmation (N = 63, 32%).

Furthermore, the strategies of disconfirmation employed in Hebrew can be very direct and unmitigated, and the responder may even take the opportunity of disconfirmation to criticize or ridicule the confirmable offered up. This is despite – or perhaps because of – the fact that our data come from conversations between close friends and family members. This corroborates earlier Linguistic Anthropological studies of Hebrew discourse, such as Katriel’s (1986, 2004) or Blum-Kulka’s (1992), that claim a high tolerance for disagreement in Israeli Hebrew, as well as relatively little concern with recipient face wants (cf. earlier evidence by Levenston 1968).

It is important to clarify that although Hebrew interaction features more disconfirmation and less mitigation of disconfirmation, this is not to say that disconfirmation is the preferred response type, or that it is on par with confirmation. Confirmation remains the most common and preferred response in Hebrew interaction, as in all other languages surveyed; disconfirmation remains dispreferred and more likely to be followed by an account (Section 5.4). This naturally raises the question of which contexts license or favor unmitigated disconfirmations, defying the general preference structure – a fascinating topic for further research.

We provide below two examples of such unmitigated disconfirmation. Excerpt 10 ‘Mamma Mia’, from the same interaction as Excerpt 7 ‘Just Visiting’, involves five close friends, older women who have been meeting once a week for many years. Noa raises a new topic about a movie she recently saw.

Noa’s gaze when raising the topic is at Tsila (l. 1), who indeed responds by asking which movie this was (l. 2). Noa delays her answer, first verifying which of her recipients has already heard this information. Initially, she addresses Tsila with an RfC (l. 3), but before receiving a response, she follows this with a question to the entire group (l. 4), and provides an answer herself (l. 5). By pointing her chin at Irit while saying ‘[it was] you I told’ (l. 5), overlapping Irit’s ‘me’ (l. 6), she establishes that Irit is in the know concerning which movie Noa saw.

Tsila pursues an answer to her earlier question by raising a candidate movie in the form of an RfC: ‘Mamma Mia?’ (l. 7). Noa claps a hand on her knee in time for a response (l. 8), possibly the beginning of an enthusiastic telling about the movie she saw, but the floor is taken by Irit (who is, as mentioned, in the know) responding to Tsila’s candidate answer: lo, mama miya, yeš 'al ze‐‐, bikoret kaša. ‘no, Mamma Mia, tha‐‐t’s gotten, harsh reviews’ (l. 8–11). Irit’s response is an unmitigated disconfirmation with the RT lo ‘no’, in continuing intonation, followed by taking issue with the suggestion that Mamma Mia is even worth watching.

Irit then launches into a story about how she got free tickets to the movie, to account for her negative assessment of it (l. 12, 14), but Noa and Tsila both interrupt to object to Irit’s negative assessment and demand more details (l. 13, 15). They can be heard as defending the legitimacy of Tsila’s candidate movie. At the same time, however, they are acknowledging Irit’s epistemic right to disconfirm the suggestion, and later on, they will accept Irit’s negative assessment of Mamma Mia. Despite the lack of softening of Irit’s disconfirmation, and despite her harsh criticism of the confirmable, the interaction continues without any display that some norm of conduct was breached.

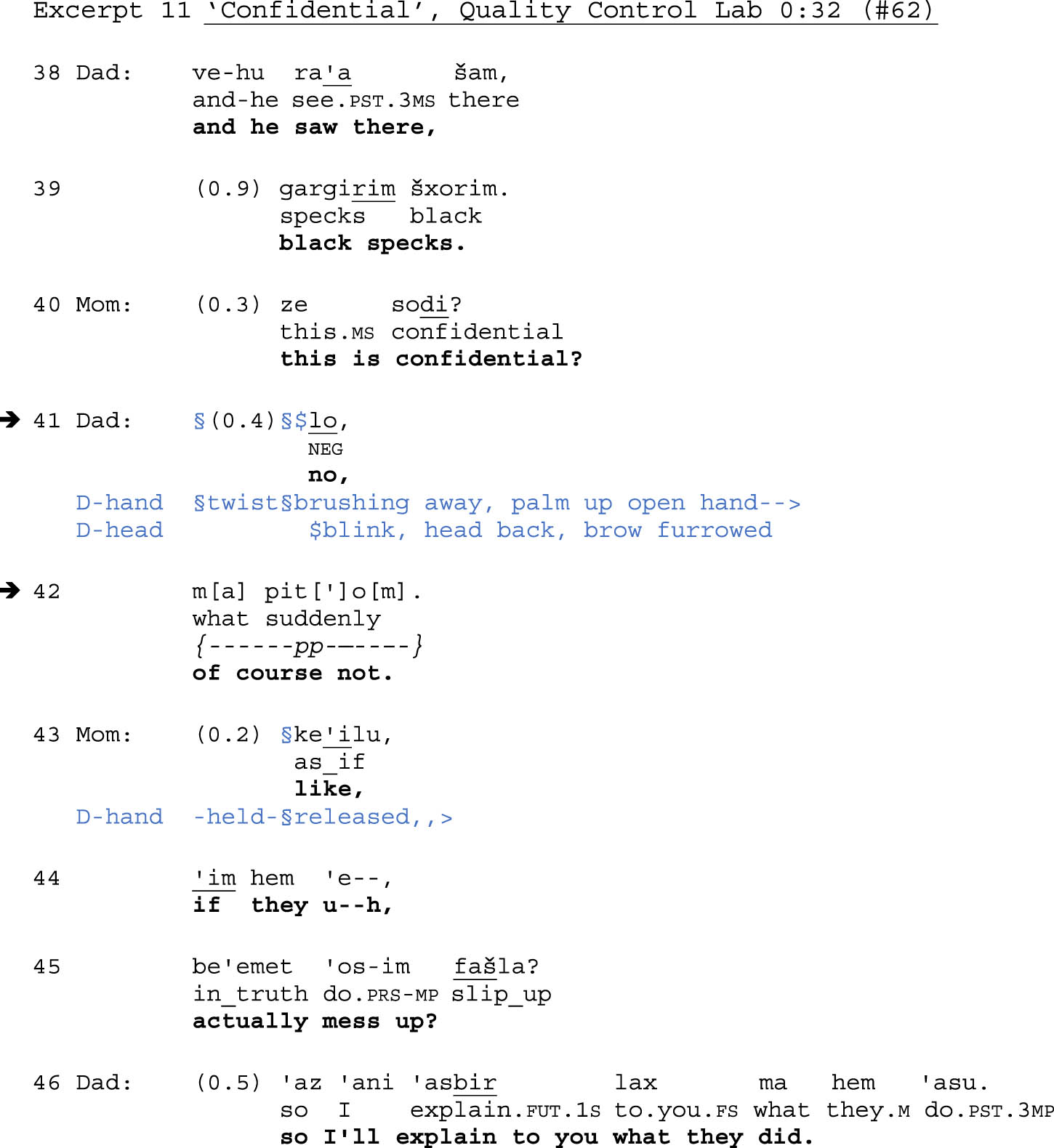

Another example of unmitigated disconfirmation is shown in Excerpt 11 ‘Confidential’, from earlier on in the family interaction from Excerpt 5 ‘Black Speck’. Dad is describing the baby formula manufacturer finding black specks in his sugar delivery.

Mom responds to Dad’s telling (l. 38–39) with an RfC: ze sodi? ‘this is confidential?’ (l. 40). Presumably, it seems to her that the baby formula company should hush up such problems. The reason to this is mentioned a few seconds after this excerpt: the ‘Remedia affair’ a few years back, when a lack of vitamins in a brand of baby formula caused the death of five babies and harmed many others. Dad’s answer is a strong, unmitigated negation followed by a dismissal of his partner’s RfC. We see here, besides the common negative RT lo ‘no’ (l. 41), a dedicated RT, ma pit'om (l. 42), which has been analyzed as a discourse marker expressing strong disagreement (Maschler 2009, 23, Bardenstein 2020, 77–9) and carrying a strong epistemic stance of certainty (Miller 2010, 349). We argue that here it carries also a quality of dismissal, challenging the ‘askability’ of the question (Stivers 2011). We support this interpretation observing Dad’s accompanying embodied behavior: furrowed eyebrows, or frowns (Ekman 1979), which were found to be associated with disaffiliative actions that are at odds with a preceding action expressed by the interlocutor (Kaukomaa et al. 2014), and a brushing away Palm-Up Open-Hand gesture, which has been associated with obviousness (Marrese et al. 2021, Inbar and Maschler 2023).

The expression ma pit'om has no exact English equivalent (the translation ‘of course not’ does not do it justice). Literally, it means ‘what suddenly’, as in ‘where did this question come from, all of a sudden?’. This has crystallized as a discourse marker and is here very much semantically bleached and phonetically reduced (cf. Hopper 1991, Traugott 1995) – Dad produces it very softly, with devoiced vowels, [m̩pi̥to̥]. Such dismissals of other participants’ assumptions are common enough in Hebrew discourse that an RT dedicated to just this type of move – ma pit'om – has emerged in the language (cf. comment on the rarity of epistemically upgraded negative responses in English by Stivers 2011: 88, fn. 6).

In response, following ke'ilu ‘like’, Mom begins to elaborate on her previous utterance (Maschler 2002), smiling, that if the sugar factory had actually messed up, they probably wouldn’t want it published, in an attempt to justify the confirmable she has put forward (l. 43–45). Dad promises to explain and proceeds with the telling (l. 46). Again, the interaction continues without any display of some norm of conduct having been breached.

Nevertheless, both here and in the previous excerpt, the speakers do address in some way the disalignment created by the unmitigated disconfirmation – with an account by the disconfirmer in the previous case, and here through an expansion by the disconfirmer (l. 46 ff.). These efforts show that the speakers do strive for alignment and social cohesion, as generally reflected in the organization of dispreferred responses.

5.2 RTs

An RT is defined in this project as the minimal conventionalized form of a language that can be employed for (dis)confirmation. It is a “dedicated answer form … which [does] not assert a proposition in and of [itself] but [does] confirm one” (Enfield et al. 2019, 288). RTs are used in 60% of Hebrew verbal responses (N = 113); this is a moderate amount in comparison to the other languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming).

Responses are often accompanied by nodding or headshakes (e.g., Excerpts 1 and 8, l. 3), but in Hebrew, it is also possible to indicate (dis)confirmation solely through a nod or headshake, as seen in the nodding of Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’, l. 211 and the headshake of Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’, l. 2 (cf. Du-Nour 1987, 180). This strategy is used infrequently in our collection: we found ten cases of solely non-verbal responses (5% of all responses). In the examples above, the circumstances seem to license the non-verbal response: in Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’, the nod is found at the end of a sequence of phrasal RfCs, when the knowledge gap between speakers has been almost entirely bridged; in Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’, the headshake is used by a non-selected speaker, preoccupied with chewing. Further study is needed to generalize in which circumstances speakers tend to use non-verbal formats, but it seems likely that they are used in somewhat different interactional circumstances than verbal RTs (pace Enfield et al. 2019).

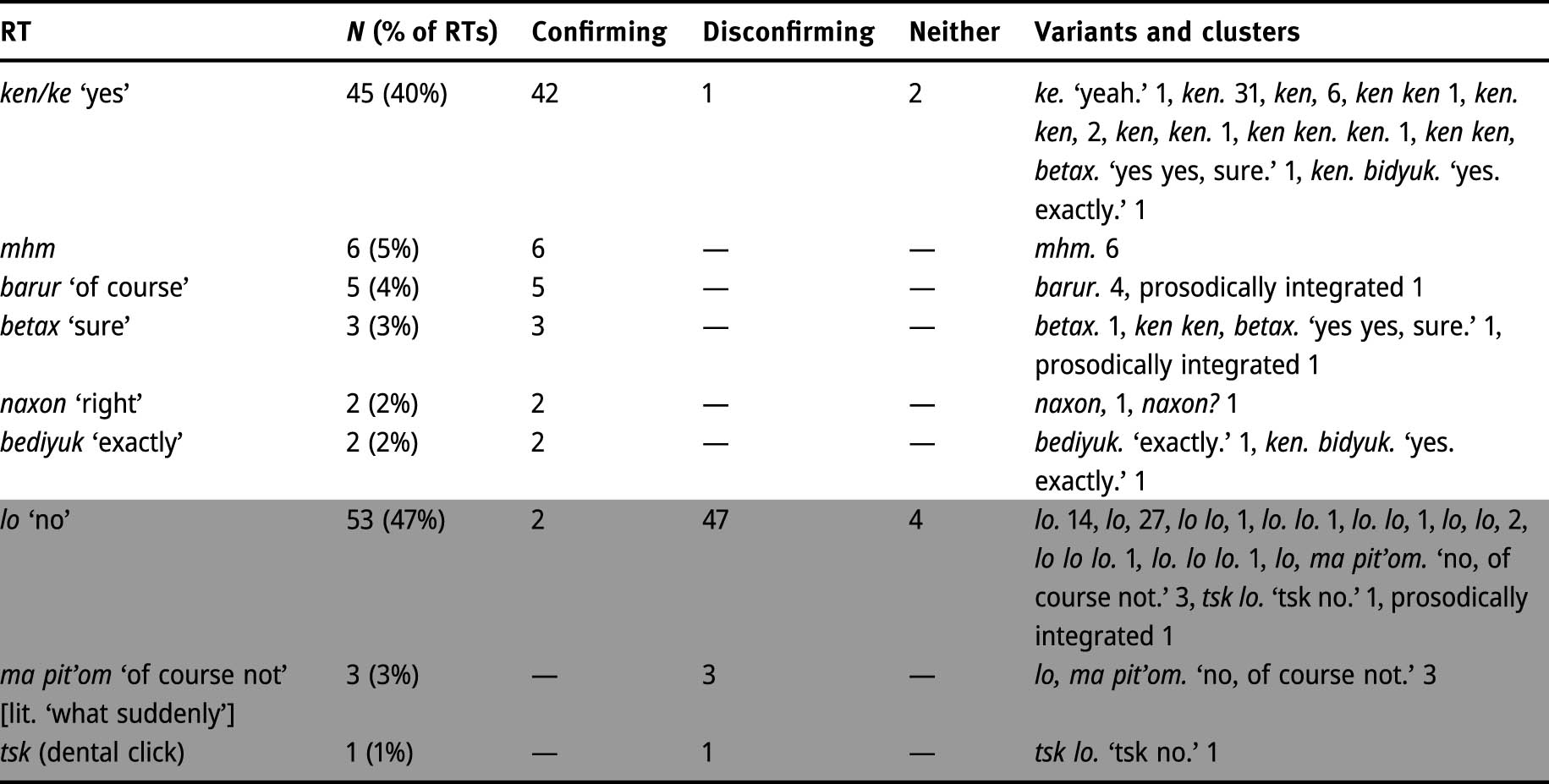

The inventory of Hebrew RTs is provided in Table 7. Negative RTs are differentiated by a grey background. RTs sometimes appear in clusters; each component in the cluster was counted separately. Table 7 shows that Hebrew speakers employ ken ‘yes’ (N = 45; 40% of all RTs) and lo ‘no’ (N = 53; 47%), which have been illustrated in several instances above (Excerpts 2, 4, 6, 8–11), as the unmarked confirming and disconfirming RTs, respectively.[10] Interestingly, the unmarked disconfirming RT lo is more frequent in our database (N = 53) in comparison to the unmarked confirming RT ken (N = 45). This is, of course, related to the fact that the rate of disconfirmation in Hebrew is very high (Section 5.1), but it is also due to the fact that in our collection lo appears in every disconfirming response performed with RTs, while there are 15 cases of confirming responses that employ confirming RTs other than ken.

RTs in Hebrew RfC sequences

|

Another contributing factor is that in Hebrew, negative polarity RfCs are, depending on context and turn design, confirmed by RTs of either the same or the opposite polarity (see Section 5.2.1). Table 7 reflects this in that the unmarked confirming RT ken is occasionally employed for disconfirmation (N = 1), whereas the unmarked disconfirming RT lo is occasionally employed for confirmation (N = 2). Both of these eventualities happen in the case of negative polarity RfCs.

Finally, besides its use to disconfirm (cf. Shor 2018, 110), our collection includes also four cases where lo is used in responses that neither confirm nor disconfirm, negating not the request as such but implications or expectations included in it (cf. Ziv 2007, Shor 2020).

5.2.1 Responses to negative-polarity RfCs

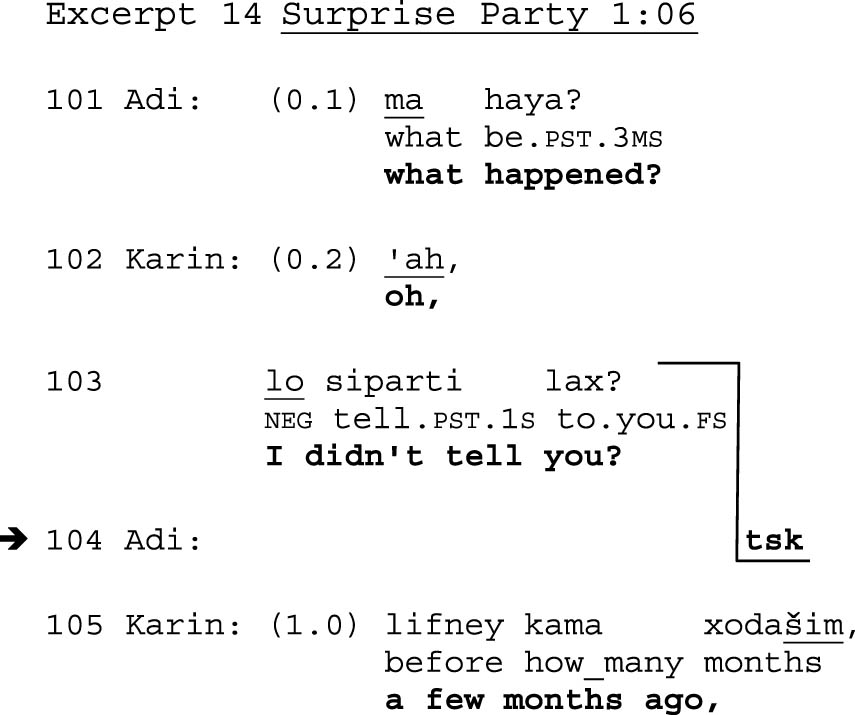

As discussed in Section 4.2, some negative-polarity RfCs are interpreted literally and make relevant a matching negative-polarity response. An example of this is shown in Excerpt 8 ‘Wrapping Up’: The RfC 'anaxnu lo be-kivun shel lehitkapel 'od me'at. naxon? ‘we’re not about to wrap [this] up soon. right?’ (l. 1–2) is confirmed by the negative RT lo ‘no’ (l. 3). A similar case can be seen in Excerpt 14 ‘Surprise Party’ below, confirmed by a dental click.

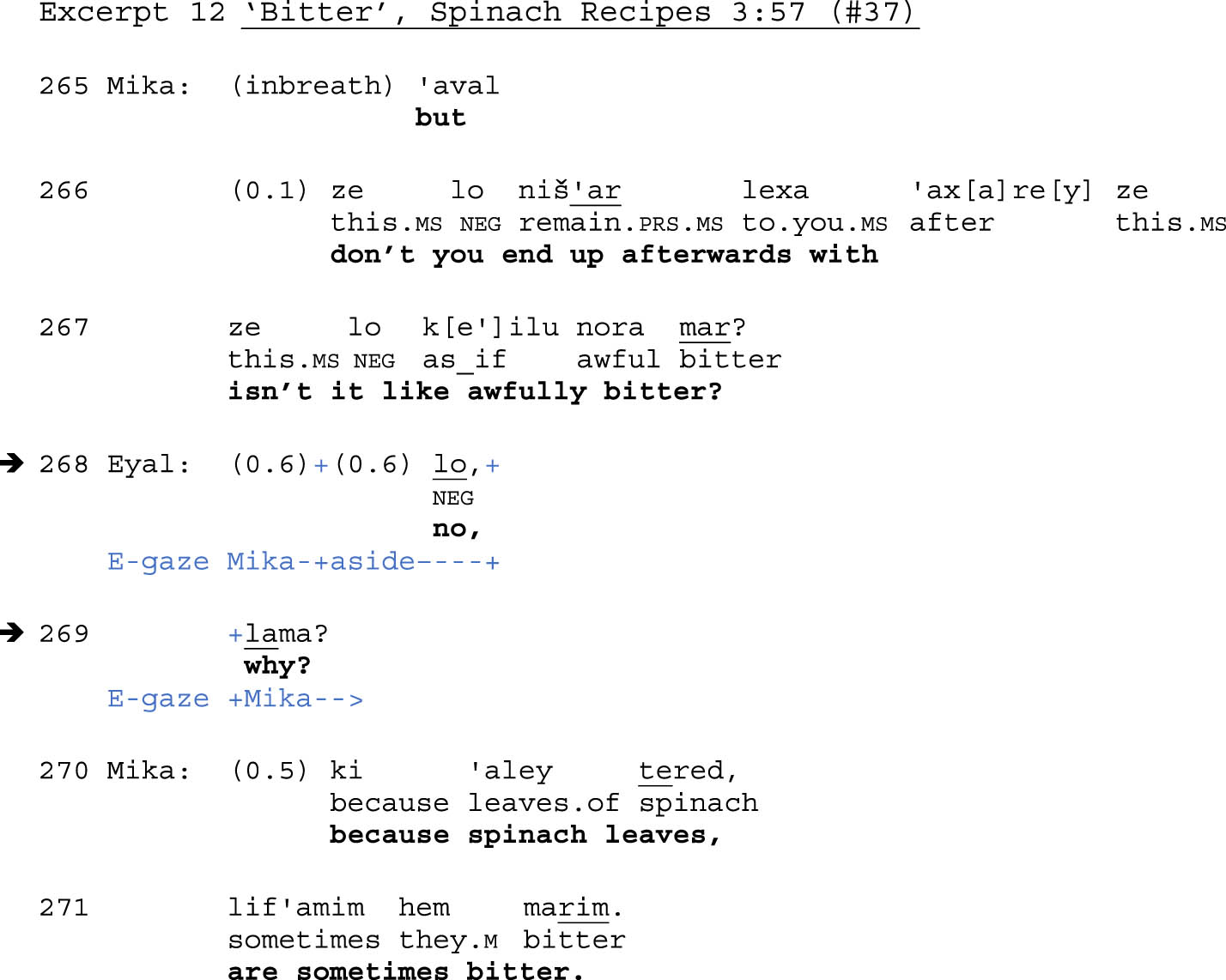

On the other hand, in some negative-polarity RfCs, the negation is interpreted as an indication of stance, and these RfCs make relevant a reversed-polarity, positive response. This is seen in Excerpt 12 ‘Bitter’, which features a negative polarity RfC disconfirmed by lo ‘no’:

Preceding this excerpt, Eyal is recounting the benefits of making a curry with fresh spinach leaves, as discussed in Excerpt 2 ‘Curry Spices’. Employing the negative polarity RfC ze lo ke'ilu nora mar? ‘isn’t it like awfully bitter?’, Mika presents a counter-argument (employing DM 'aval ‘but’, l. 265) for using spinach, asking whether this doesn’t leave a very bitter taste in the mouth (l. 266–267). This is apparently Mika’s experience with spinach (l. 270–271), but the epistemic gradient is tilted toward Eyal, the expert on this type of curry.

In contrast to the negative polarity RfCs of Excerpts 8 ‘Wrapping Up’ and 14 ‘Surprise Party’, which make relevant a negative polarity response, and thus receive a minimal negative-semantics RT, with no delay, as a confirmation, Mika’s RfC makes relevant an answer of the opposite polarity (cf. Koshik 2002), based on its position in the sequence in which it occurs (Schegloff 1997) and possibly also on prosodic design.[11] We interpret Mika’s negation as indicating her epistemic stance of uncertainty, similarly to the co-occurring hedge k[e']ilu ‘like’. Both serve to soften the action Mika is performing, ensuring that she is interpreted as deferring to Eyal and not criticizing his cooking. Eyal appropriately delays his response, looking aside to display a ‘thinking face’ (Harness Goodwin and Goodwin 1986; l. 268), before he disconfirms with the negative semantics RT lo ‘no’ (l. 268), and expands his dispreferred response (Pomerantz 1984) with an invitation for further elaboration from Mika (l. 269).

5.2.2 Clusters of RTs

RTs are often found in clusters. For the purposes of the cross-linguistic comparison, clusters were coded only if the tokens occurred within a single intonation unit (N = 6, 5% of RTs); the only RTs in our collection appearing in such clusters are ken ken and lo lo (cf. Shor 2020, 592).[12] However, RTs appeared much more frequently in clusters in consecutive intonation units (N = 17, 15%) (cf. Maschler 1994). Across intonation units, clusters are more varied: the first token is usually still the unmarked ken or lo, followed by an RT with a more specialized function, such as ma pit'om ‘of course not’ (Excerpt 11 ‘Confidential’). There are only five such clusters involving multiple RTs in our collection, but the tendency to open clusters with ken/lo is corroborated by examples from written Hebrew (Burstein 2021, 125).

5.2.3 Confirming RTs

In Excerpt 1 ‘Milk Bottle’, we showed an example of the RT mhm – which is not as frequent in Hebrew as in many of the other languages analyzed in this project (N = 6; 5% of all RTs). In Excerpt 3 ‘Amsterdam’, we discussed naxon? ‘right?’ – the only RT realized in rising intonation in our corpus (cf. Japanese deshoo?, Suzuki 2019) – which marks confirmation while also inviting the interlocutor to agree in turn with the RfC that they themselves have in fact put forward in the first place. The RT naxon is much more frequent in falling or level intonation. Previous studies (Miller 2012, 2010, 163–7, Maschler and Miller Shapiro 2016) have shown that it marks also epistemic independence (Heritage 2002) with regard to the matter under discussion.

The next most frequent confirming RT following ken ‘yes’ and mhm is barur ‘of course’ (lit. ‘clear’), which carries a strong epistemic stance of certainty (Miller 2010). Barur appears to be similar to marked, upgraded forms in other languages (Stivers 2011, 2022, 99) in challenging the ‘askability’ of the question – indicating that the question is morally problematic or that the answer should be available to the asker. In Excerpt 13 ‘Divorce Karma’, Mika is telling Eyal about deterring her partner from buying a used bed that belonged to his ex-wife’s sister, who is also getting a divorce. Mika reports asking her partner whether he thinks sleeping on a bed involving so much ‘divorce karma’ is a good idea:

Eyal initially responds to Mika’s karma argument with laughter (l. 233, 236). However, as she begins to move on to the next narrative event (l. 242–243), he overlaps with the RfC siryesli, ze mafria lax? ‘seriously, this bothers you?’ (l. 244–245). Apparently, this seems ridiculous to him, but Mika is of course the epistemic authority regarding her own preferences. By confirming this RfC with barur (l. 246), she claims a high degree of certainty and presents the confirmable as obvious, refusing to entertain the implied criticism in Eyal’s question, that ‘divorce karma’ is not a legitimate concern.

5.2.4 Disconfirming RTs

Above we have shown an example of the disconfirming RT ma pit'om (Excerpt 11 ‘Confidential’). Another interesting feature of Hebrew is the use of clicks as disconfirming RTs. Like many other languages from the Mediterranean to South Asia (Gil 2013), Hebrew employs a dental click to signify disconfirmation (Ben-Moshe and Maschler forthcoming). Since the sole negating click in this collection is in a cluster with lo, we illustrate with an example from a part of our corpus which was not used for the comparative project. In Excerpt 14 ‘Surprise Party’, Karin is trying, unsuccessfully, to remind Adi of an incident involving a sauna.

When Adi asks what happened (l. 101), Karin realizes (as evidenced by the particle 'ah in l. 102, cf. Section 4.4) that Adi hasn’t heard about the incident in the first place, and she asks Adi if this is the case employing the negative polarity RfC lo siparti lax? ‘I didn’t tell you?’ (l. 103). Adi responds immediately with a single click (l. 104) – that this is treated as a negative response is shown by Karin’s following turn (l. 105), where she begins to recount the incident.

5.3 Position of RTs within the responsive turn

The great majority of RTs in our collection are turn-initial (N = 105, 93%). Only two final RTs were found (2%) – this is the lowest rate among all languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). Our collection exhibits a few turn-medial RTs (N = 6, 5%). In most of them, the speaker accomplishes another action related to the RfC – co-constructing, repairing, verifying, or displaying the processing of the RfC – before (dis)confirming it with the RT.

5.4 (Non)minimal responses

In 38 of the cases (20% of verbal responses), Hebrew responses are minimal, consisting of an RT or cluster of RTs alone (e.g., Excerpts 1–3, 6, 8, 9, 11, and 13). This places Hebrew closer to the lower end among the ten languages analyzed in this project (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). In 75 cases (40%), the response is expanded past the RT (cluster) (e.g., Excerpts 4 ‘Japanese Duolingo’, 10 ‘Mamma Mia’, and 12 ‘Bitter’).

Responses involving affirmative RTs such as ken ‘yes’ were minimal 43% of the time, whereas those involving negative RTs such as lo ‘no’ were minimal only 23% of the time. Thus, lo is much less likely to be the only component of a response compared to ken, showing that disconfirming responses tend to be elaborated and mitigated in Hebrew as well – a language featuring more disconfirmation and less mitigation of disconfirmation – and lending support to theories of preference structure (e.g., Pomerantz 1984). This is illustrated in the expansion past the RT in the dispreferred response of Excerpt 12 ‘Bitter’, where Eyal disconfirms and then expands the dispreferred response by inviting the interlocutor to further elaborate on her RfC.

Expansions past preferred responses are generally deployed for elaboration (e.g., Excerpt 4 ‘Japanese Duolingo’), but they can also be employed for other actions, such as joking, or, when prefaced by 'aval ‘but’, as part of a concessive construction, in which the speaker first acknowledges the validity of the confirmable but then detracts from the acknowledgement (e.g., Couper-Kuhlen and Thompson 2000). In other cases, the (dis)confirmer responds with an RT and proceeds to immediately continue the action they were engaged in before the RfC sequence (in which case it can be considered an insertion sequence).

5.5 Responding by repeat of the RfC

Responses to Hebrew RfCs may include repetition of verbal material from the request (N = 64, 34% of verbal responses). In the majority of these, 46 cases (25% of verbal responses), only part of the request was repeated. We have seen examples of this above in Excerpts 7 ‘Just Visiting’, 10 ‘Mamma Mia’, and 5 ‘Black Speck’ (ordered from the most to the least repeated content). Burstein (2021, 135–40, 148, 151–4, 182, 184–5) reviews a variety of repeats answering polar questions in written Hebrew, and concludes that answers most commonly repeat the predicate, and that other constituents may be repeated for further specification. Miller (2010, Section 3.4) describes the use of repetition in Hebrew conversation to express an epistemic stance of increased certainty or to establish independent epistemic authority – as seen, for example, in Excerpt 10 ‘Mamma Mia’, l. 9.

In 11 cases (6% of verbal responses), the request was repeated in full and mostly unchanged.[13] In seven more cases (4% of verbal responses), the request is repeated in full and further expanded. The rate of full repeats in Hebrew is in the lower range in relation to that of the other languages compared in this project, and it is significantly lower than the two languages which truly favor this strategy, Low German and Yurakaré (Pfeiffer et al. forthcoming). In our collection, all full repeats – both the repeated part of the confirmable and its repetition – consist of a single intonation unit. However, these intonation units are typically syntactically complex: most full repeats consist of full clauses (N = 9); only two consist of phrases (similarly, the ‘full expanded’ repeats included 7 full clauses and only 1 phrase).

In Hebrew, repeats can be used to express not only epistemic but also affective stance. In Excerpt 15 ‘Parade’, Dotan has been telling Alex about a group of Australian tourists that he led, ridiculing them for considering the day they saw Prime Minister Netanyahu at some lackluster ceremony (involving 2.5 h of waiting) to be the height of their 3-week visit to the Holy Land:

Alex affiliates with Dotan’s ridiculing stance by smiling throughout (l. 168–169, 173). The ceremony also included a parade, and Alex responds by laughingly requesting confirmation regarding this feature of the event which might justify the tourists’ excitement – hem hayu bamits'ad? ‘they were at the parade?’ (l. 174). Dotan confirms with a repeat[14] – ve-hem hayu bamits'ad., ‘and they were at the parade’ (l. 176) – but this repeated material is recontextualized not just as a confirmation, but also as a stance display. This is evidenced by Dotan’s accompanying embodied behavior: gaze withdrawal (cf. Kendon 1967, 48, Haddington 2006, Robinson 2020, Pekarek Doehler et al. 2021) and a gesture of throwing away something behind his shoulder (l. 176), which we interpret as expressing dismissal.

This stance is underscored by the following b[e]seder lit. ‘alright’ (l. 177), which Shefer (2021, 17) analyzes as a discourse marker of acceptance which may at the same time express “discontent, even sarcasm …, roughly paraphrased as a dismissing ‘whatever’.” Dotan follows this with yet another repetition of the word mits'ad ‘parade’ (l. 178), this time in a separate intonation unit and in marked prosody, consisting of lower pitch, a fall-to-low pitch movement, and a slightly decreased intensity (cf. Shor and Marmorstein 2024, Section 4.5). This type of repetition highlights the apparent ridiculousness of the original mits'ad formulation, suggesting that the event they saw isn’t fit for the term (cf. Raymond 2016, 121), thereby again expressing disdain for the tourists’ experience on that day.

Full repeats in our data are similar in that they allow the speaker to recast the repeated material, e.g., adding stance, claiming independent epistemic access, or prosodically singling out a portion for repair (in disconfirmations) or upgrading (in confirmations).

6 Conclusion

Our study of Hebrew RfC sequences can only provide a general quantitative comparison with the nine other languages investigated in this special issue. It constitutes a starting point for in-depth studies of a variety of features involved in these sequences.

Formally, Hebrew relies on intonation for marking the request more so than any of the other languages analyzed in this project (Section 4.7) – a fact no doubt related to the lack of syntactic marking of interrogatives in Hebrew polar questions. The language makes little use of tag questions (Section 4.6), but relatively often employs inference markers (Section 4.4) and connectives (Section 4.5), which often appear in clusters. Hebrew is rich in types of connectives and modulators (Section 4.3), but the latter appears only moderately in our data in relation to modulators in the other languages analyzed in this project (Section 4.3). The most frequent modulator is the use of negation to indicate epistemic stance (Section 5.2.1).

One of the most intriguing features of the Hebrew language and culture is the high rate of disconfirmation (Section 5.1). The frequent lack of mitigation and accompanying dismissive stance are related prominent characteristics. Affective stance plays a role also in repeats, which responders use to recontextualize parts of the question while (dis)confirming (Section 5.5). However, full repeats are a minor strategy in comparison with RTs, which appear in over half of the responses in our collection. Hebrew is placed in the middle range among the languages investigated in this project with respect to RT employment. In particular, it features two fascinating negative RTs: the dental click, which is shared by many neighboring languages (Section 5.3.4); and ma pit'om ‘of course not’ (lit. ‘what suddenly’, Section 5.1), attesting the license for forceful and unmitigated disconfirmation in Hebrew.

A particularly fruitful avenue for future research seems to us to be the possibility of negative polarity RfCs to make relevant both confirmation and disconfirmation employing the same, unmarked negative RT lo ‘no’. We suspect that not only sequential position but also prosody – in particular placement of the primary stress of the intonation unit comprising the request – plays a crucial role in determining whether a particular negative-polarity RfC makes relevant a positive- or negative-polarity response as confirmation.

Each one of the particular resources composing the practice of requesting confirmation – modulators, inference markers, connectives, tag questions, RTs, and prosody – awaits detailed investigation. Nonetheless, the methodology employed in the larger project of which this study is a part yielded a refreshing comparative perspective on Hebrew. We hope to have shed some light on the particularities of the ways Hebrew speakers request confirmation and respond to such requests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Katharina König, Martin Pfeiffer, Mira Ariel and another anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. We would also like to thank all of the members of the Interactional Linguistics network, and particularly Katharina König and Martin Pfeiffer, for making this stimulating research project possible.

-

Funding information: This article was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) project number 413161127 – Scientific Network “Interactional Linguistics – Discourse particles from a cross-linguistic perspective” led by Martin Pfeiffer and Katharina König. This research was generously supported by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF grant No. 941/20 to Yael Maschler).

-

Author contributions: Both authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Both authors analyzed the data and wrote the paper together.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix: Transcription Conventions

Glosses throughout the article are composed of groups of up to five types of lines. The first line is a transcription, generally following standard Hebrew orthography; elements that are not pronounced are enclosed in square brackets (e.g., ['a]ta). We use conventional IPA values, except for y for /j/, š for /ʃ/, and an uninverted quotation mark (') for the glottal stop phoneme.

The transcription conventions of the Haifa Corpus of Spoken Hebrew are based on those of the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English (Du Bois et al. (1992), Du Bois (unpublished manuscript, 2012)), as adapted for Hebrew (Maschler 2017). Each numbered paragraph denotes a single intonation unit (Chafe 1994):

, – comma at end of line – mid-level, mid-rise, mid-fall intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as “more to come”

, – period at end of line – low fall intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as final

? – question mark at end of the line – high rising intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as final and seeking a response from interlocutor (‘appeal’)

?, – a question mark followed by a comma – rising intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as projecting ‘more to come’ while seeking (minimal) response from interlocutor

! – exclamation mark at end of the line – final exclamatory intonation

ø – lack of punctuation at end of the line – a fragmentary intonation unit, one which never reached completion.

‐‐ – two hyphens – elongation of preceding sound.

underlined syllable – primary stress of intonation unit.

@ – a burst of laughter (each additional @ symbol denotes an additional burst).

☺bab☺ – text bracketed by smileys is produced with a smile.

(in regular brackets) – nonverbal action constituting a turn.

/words within slashes/ indicate uncertain transcription.

/????/– indecipherable utterance.

a square bracket to the left of two consecutive lines indicates the beginning of overlapping speech, two speakers talking at once.

alignment such that the right of the top line is placed over the left of the bottom line indicates latching, no interturn pause.

The second (optional) line is a gloss, following the Leipzig Glossing Rules (www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php), with the exception of gender and number being glossed only on verbs and pronouns, not nouns or adjectives, in the interest of legibility. Person, gender, and number are abbreviated into single, unseparated letters, such as 3fs – third person feminine singular, 1s – first person singular (not marked for gender). Square brackets in the gloss line indicate a Ø morpheme, such as matxil ‘begin.prs[ms]’.

Other abbreviations used are fut – future, inf – infinitive, obj – object, prs – present, psn – personal name, pst – past, neg – negation.

The third (optional) line indicates prosody {in italic curly brackets}, using musical notation, e.g., {pp} for pianissimo (very soft), or transcriber’s comments.

The fourth line contains an English translation.

Finally, one or more (optional) lines indicate multimodal aspects of interaction in blue font, following Mondada 2019:

+nod A punctual embodied action is described following a single symbol in the following line (one symbol per participant and per type of conduct), synchronized with corresponding stretches of talk.

§pointing§ Prolonged embodied actions are described between two identical symbols.

----> Described embodied conduct continues across subsequent lines

----# until the same symbol is reached.

>>--- Described embodied conduct begins before the line’s beginning.

Participants are identified by the first letter of their name followed by the part of their body that is transcribed, e.g., A-face and A-hands for Alex.

References

Ariel, Mira. 2010. Defining Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511777912Suche in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter. 2018. “Gaze, Addressee Selection and Turn-Taking in Three-Party Interaction.” In Eye-Tracking in Interaction: Studies on the Role of Eye Gaze in Dialogue, edited by Geert Brône and Bert Oben, 197–232. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ais.10.09aueSuche in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter and Yael Maschler. 2013. “Discourse or Grammar? VS Patterns in Spoken Hebrew and Spoken German Narratives.” Language Sciences 37: 147–81. 10.1016/j.langsci.2012.08.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Bardenstein, Ruti. 2020. “תהליך ההידקדקות של שאלות רטוריות [The grammaticalization path of rhetorical questions].” Balshanut 'Ivrit [Hebrew Linguistics] 83: 73–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Moshe, Yotam Michael. 2022. “The Many Faces of Hebrew way: A Cognitive and Affective Change-of-State Token.” Presented at the Workshop on Interactional Linguistics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, June 8.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Moshe, Yotam Michael and Yael Maschler. Forthcoming. “Hebrew Clicks and their Evolution from Byproducts into Linguistic Signs.”Suche in Google Scholar

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1992. “The Metapragmatics of Politeness in Israeli Society.” In Politeness in Language: Studies in its History, Theory and Practice, edited by Richard J. Watts, Sachiko Ide, and Konrad Ehlich, 255–80. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110886542.Suche in Google Scholar

Bolden, Galina. 2010. “‘Articulating the unsaid’ via and-prefaced formulations of others’ talk.” Discourse Studies 12: 5–32. 10.1177/1461445609346770.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, Ruth. 2021. משפטי השאלה ומשפטי התשובה בעברית בת-ימינו: עיון תחבירי, סמנטי ופרגמטי [Interrogative and Responsive Sentences in Contemporary Hebrew: A Syntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic Study]. Tel Aviv: The MOFET Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Chafe, Wallace L. 1994. Discourse, Consciousness, and Time: The Flow and Displacement of Conscious Experience in Speaking and Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, Smadar. 2004. “ושאינו יודע לשאול - מה הוא אומר?: דרכי השאלה בעברית המדוברת [And he who does not know how to ask - what does he say? Ways of asking questions in spontaneous spoken Hebrew].” MA thesis. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, Israel.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, Smadar. 2009. “ושיודע לשאול - מה הוא אומר?: דרכי השאלה בעברית המדוברת [And he who knows how to ask - what does he say? Ways of asking questions in spontaneous spoken Hebrew].” Balshanut 'Ivrit [Hebrew Linguistics] 62–63: 35–47.Suche in Google Scholar

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth and Margret Selting. 2018. Interactional Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781139507318.Suche in Google Scholar

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth and Sandra A. Thompson. 2000. “Concessive Patterns in Conversation.” In Cause - Condition - Concession - Contrast: Cognitive and Discourse Perspectives, edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Bernd Kortmann, 381–410. Berlin: De Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110219043.Suche in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf, Alexandra Gubina, Katharina König, and Martin Pfeiffer. 2024. “Request for Confirmation Sequences in German.” Open Linguistics 10 (1): 20240008. 10.1515/opli-2024-0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Du Bois, John W. 2012. “Representing Discourse.” Unpublished manuscript, Linguistics Department, University of California at Santa Barbara (Fall 2012 version). https://www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/research/santa-barbara-corpus.Suche in Google Scholar

Du Bois, John W., Susanna Cumming, Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, and Danae Paolino. 1992. Discourse Transcription. Santa Barbara Papers in Linguistics 4. Santa Barbara: Department of Linguistics, University of California, Santa Barbara.Suche in Google Scholar

Du-Nour, Miryam. 1987. “עיון במבנה הדיאלוג של מחזות עבריים לאור תורות חקר השיחה: עפ“י כמה ממחזותיו של חנוך לוין [Studies in the structure of dialogue in Hebrew plays by means of conversational analysis].” PhD thesis. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.Suche in Google Scholar

Ekman, Paul. 1979. “About Brows: Emotional and Conversational Signals.” In Human Ethology: Claims and limits of a new discipline, edited by Mario von Cranach, Klaus Foppa, Wolf Lepenies, and Detlev Ploog, 169–248. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Enfield, Nick J., Tanya Stivers, Penelope Brown, Christina Englert, Katariina Harjunpää, Makoto Hayashi, Trine Heinemann, et al. 2019. “Polar Answers.” Journal of Linguistics 55 (2): 277–304. 10.1017/S0022226718000336.Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, Nicholas. 2007. “Insubordination and its Uses.” In Finiteness: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations, edited by Irina Nikolaeva, 366–431. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199213733.003.0011Suche in Google Scholar

Gil, David. 2013. “Para-linguistic Usages of Clicks.” In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online, edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/chapter/142.Suche in Google Scholar

Glinert, Lewis. 1989. The Grammar of Modern Hebrew. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Greenberg, Yael and Lavi Wolf. 2019. “Intensified Response Particles to Assertions and Polar Questions: The Case of Hebrew legamrey.” In Proceedings of NELS 49, edited by Maggie Baird and Jonathan Pesetsky, vol. 2, 61–70. Amherst: GLSA.Suche in Google Scholar

Haddington, Pentti. 2006. “The Organization of Gaze and Assessments as Resources for Stance Taking.” Text & Talk 26 (3): 281–328. 10.1515/TEXT.2006.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Harness Goodwin, Marjorie and Charles Goodwin. 1986. “Gesture and Coparticipation in the Activity of Searching for a Word.” Semiotica 62 (1–2): 51–76. 10.1515/semi.1986.62.1-2.51.Suche in Google Scholar

Henkin, Roni. 1999. “מה בין ׳השמים כחולים כאלה׳, ׳השמים כחולים כזה׳ ו׳השמים כחולים כאילו׳: על השימוש” בכינויי רמז משווים ויסודות אחרים להסתייגות [About the use of comparative demonstratives and other elements for hedging].” In Hebrew, A Living Language II, edited by Rina Ben-Shahar and Gideon Toury, 103–22. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad and the Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics, Tel Aviv University.Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John. 1984. “A Change-of-State Token and Aspects of its Sequential Placement.” In Structures of social action, edited by John Maxwell Atkinson and John Heritage, 299–345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511665868.Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John. 2002. “The Limits of Questioning: Negative Interrogatives and Hostile Question Content.” Journal of Pragmatics 34 (10–11): 1427–46. 10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00072-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John and Geoffrey Raymond. 2005. “The Terms of Agreement: Indexing Epistemic Authority and Subordination in Talk-in-Interaction.” Social Psychology Quarterly 68 (1): 15–38. 10.1177/019027250506800103.Suche in Google Scholar

Heritage, John and Geoffrey Raymond. 2012. “Navigating Epistemic Landscapes: Acquiesence, Agency and Resistance in Responses to Polar Questions.” In Questions: Formal, functional and interactional perspectives, edited by Jan P. de Ruiter, 179–92. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139045414.013Suche in Google Scholar

Hopper, Paul J. 1991. “On Some Principles of Grammaticization.” In Approaches to Grammaticalization: Volume I. Theoretical and Methodological Issues, edited by Elizabeth Closs Traugott and Bernd Heine, 17–35. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 10.1075/tsl.19.1.04hop.Suche in Google Scholar

Inbar, Anna. 2021. “הצירופים ׳וזה׳ ו׳או משהו׳ בעברית המדוברת בת־זמננו: היבטים קוגניטיביים, חברתיים ותרבותיים [The phrases ve-ze ‘and [all] that’ and 'o mašehu ‘or something’ in contemporary spoken Hebrew: A cognitive, social and cultural perspective].” Lĕšonénu [Our Language] 83 (4): 401–24.Suche in Google Scholar

Inbar, Anna, and Yael Maschler. 2023. “Shared Knowledge as an Account for Disaffiliative Moves: Hebrew ki ‘because’-clauses Accompanied by the Palm-Up Open-Hand gesture.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 56 (2): 141–64. 10.1080/08351813.2023.2205302.Suche in Google Scholar

Jefferson, Gail. 1981. “The Abominable Ne? An Exploration of Post-response Pursuit of Response.” In Dialogforschung, edited by Peter Schröder and Hugo Steger, 53–88. Sprache Der Gegenwart, Bd. 54. Düsseldorf: Pädagogischer Verlag Schwann.Suche in Google Scholar

Katriel, Tamar. 1986. Talking Straight: Dugri Speech in Israeli Sabra Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Katriel, Tamar. 2004. Dialogic Moments: From Soul Talks to Talk Radio in Israeli Culture. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaukomaa, Timo, Anssi Peräkylä, and Johanna Ruusuvuori. 2014. “Foreshadowing a Problem: Turn-opening Frowns in Conversation.” Journal of Pragmatics 71: 132–47. 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.08.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Kendon, Adam. 1967. “Some Functions of Gaze-direction in Social Interaction.” Acta Psychologica 26: 22–63. 10.1016/0001-6918(67)90005-4.Suche in Google Scholar

König, Katharina and Martin Pfeiffer. Forthcoming. “Introduction to Special Issue ‘Request for Confirmation Sequences Across Ten Languages.’” Open Linguistics.Suche in Google Scholar

König, Katharina, Martin Pfeiffer, and Kathrin Weber. Forthcoming. “A Coding Scheme for Request for Confirmation Sequences Across Languages.” Open Linguistics.Suche in Google Scholar

Koshik, Irene. 2002. “A Conversation Analytic Study of yes/no Questions which Convey Reversed Polarity Assertions.” Journal of Pragmatics 34 (12): 1851–77. 10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00057-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Lambrecht, Knud. 1990. “‘What, me Worry?’ – ‘Mad Magazine Sentences’ Revisited.” In Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, edited by Kira Hall, Jean-Pierre Koenig, Michael Meacham, Sondra Reinman, and Laurel A. Sutton, 215–28. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.10.3765/bls.v16i0.1730Suche in Google Scholar

Levenston, E. A. 1968. “Only for Telling a Man he was Wrong.” ELT Journal XXIII (1): 43–7. 10.1093/elt/XXIII.1.43.Suche in Google Scholar

Livnat, Zohar. 2001. “אולי from Biblical to Modern Hebrew: A Semantic-textual Approach.” Hebrew Studies 42: 81–104.10.1353/hbr.2001.0041Suche in Google Scholar

Livnat, Zohar. 2009. “סמני השיח בעברית של ימינו – מבט סינכרוני ודיאכרוני [Discourse markers in Modern Hebrew: Synchronic and diachronic aspects].” In Modern Hebrew: Two Hundred and Fifty Years, edited by Chaim E. Cohen, 211–27. Jerusalem: The Academy of the Hebrew Language.Suche in Google Scholar