Abstract

The present study adopts a typological approach to investigate intersubjective uses of the Finnish clitic markers =hAn and =se, which are derived from third-person pronouns, within the emerging framework of engagement. The methods encompass two data gathering approaches: 1) a qualitative survey involving actual Finnish language users through a questionnaire to identify functions, and 2) a quantitative survey examining co-occurrences between the clitic markers and subject persons using the Suomi24 Sentences Corpus 2001–2020 for usage-based frequencies. The data analysis focuses on the interrelations with a subject person, drawing parallels with other languages which exhibit similar phenomena of pragmatic extension from referential uses towards engagement marking. The results reveal that the two Finnish clitics semantically inherit their referential meanings from their lexical forms and further extend them towards marking interlocutors’ intersubjectivity, enriching the engagement system of Finnish. A distinct difference related to the subject person becomes evident. On the one hand, =hAn as a recognitional marker more frequently co-occurs with first person, signalling the speaker’s involvement in epistemic management as a speech act participant responsible for managing inclusive attention and shared information with the hearer. On the other hand, =se as a contrastive marker co-occurs more frequently with third person in general and with second-person statements which involve the speaker’s observed information and its exclusivity.

1 Introduction

In modern standard Finnish, as described in the authoritative reference grammar (Hakulinen et al. 2004), the third person can be expressed by multiple pronouns, all of which etymologically derive from referential lexemes, demonstratives in particular. The system consists of a third-person pronoun hän ‘s/he’ and a tripartite demonstrative paradigm: tämä [proximal], tuo [distal], and se [medial]. Usage-wise, tämä and tuo more often introduce a new subject to the discourse, while hän and se usually appear as anaphoric devices, referring to a subject previously mentioned in the discourse. Between hän and se, the difference lies in logophoricity: hän logophorically refers to the main clause activity performer, while se can also exophorically refer to another person. In any case, the semantics of these third-person pronouns may not be as simple as generalised above, and a more detailed description will follow in subsequent sections.

Of particular interest in the present study are hän and se, which have evolved into clitic discourse markers =hAn and =se,[1] respectively. These clitic markers are employed in the clause-second position, following the same principle as Wackernagel’s law (1892), as given in Examples (1a) and (1b). In contrast, tämä and tuo are never used in this morphosyntactic context. Instead, they can rather serve in adverbial or filler functions, such as the inessive form of tämä, tässä ‘here’ (Etelämäki 2006); and the partitive form of tuo, tuota ‘well, erm’ (Priiki 2022).

| (1) | a. | Kalle=han | kalastel-i-kin | Kekkose-n | kanssa. |

| Kalle= han | fish-3sg.past-too | Kekkonen-gen | with | ||

| b. | Kalle=se | kalastel-i-kin | Kekkose-n | kanssa. | |

| Kalle= se | fish-3sg.past-too | Kekkonen-gen | with | ||

| Both: ‘Kalle did go fishing with Kekkonen [a former president of Finland].’ (Suomi24, 2009 sub-corpus) | |||||

While this pragmatic extension has been occurring, hän and se still maintain their original referential functions as independent third-person pronouns. This dual usage sets hän and se apart from other third-person pronouns, tämä and tuo, which cannot be used as clause-second clitics. Additionally, they differ from other modal clitics, such as -pA and -kin/-kAAn, which cannot appear as free morphemes. Due to their extended morphosyntactic behaviour, we focus our research on hän and se in the current study, as the understanding of their extended pragmatics can enhance our knowledge of functional extension patterns of referential devices.

Function-wise, these clitic markers serve both discourse-related functions and other uses related to intersubjectivity and stance-taking, as previously described for =hAn (Hakulinen et al. 2004, §830, with further description in Section 2). These functions are particularly evident in the domain of engagement, as the focus of the present study, which is suitable for investigating the interlocutors’ relative accessibility to an entity or state of affairs under discussion. In the actual language use, their use is morphosyntactically entirely optional (i.e. they never affect the grammaticality of sentences), they illustrate not-at-issue semantics (i.e. they do not change the proposition of the sentence), and they pragmatically display an array of interactional functions, as will be discussed in the subsequent sections of this study.

With the emerging trend, the concept of engagement has become a frequently discussed topic in the linguistic intersubjectivity studies of the 2020s, receiving increased attention from scholars who explore grammatical strategies to manage interlocutors’ interaction and epistemic perspectives in languages of the world (Evans et al. 2018a, b; and a collective volume edited by Bergqvist and Kittilä 2020a). It is a recently proposed concept which has enriched the discussion of communicative strategies and stance-taking, alongside other closely related concepts within the field of intersubjectivity studies, such as epistemicity, evidentiality, and egophoricity. All of these concepts are related to how interlocutors perceive and maintain the state of knowledge and attention in discourse, either explicitly by grammar in certain languages (as will be discussed in Section 2) or implicitly through context and inference in other languages (see interrelation between the mentioned concepts shown in the study by Bergqvist and Kittilä 2020b).

Taking a typological approach which emphasises linguistic diversity within its underlying universality, it is intriguing to explore various languages of the world to understand the grammatical, lexical, or pragmatic strategies which the speaker uses to encode engagement and how the hearer processes these messages. To ensure that similarities and differences between the two Finnish markers under focus can be functionally compared without the unnecessary need to label their uses as discourse particles, expletive subjects, or syntactically dislocated pronouns (cf. Hakulinen et al. 2004, §793, §915, §1018), our starting point is the construction of clause-second position. Such a construction-based approach has previously provided a more detailed description of equivalent markers in other Finnic languages and could more thoroughly extract their functional dimensions from the data (Yurayong 2020). Within this given morphosyntactic context, we set out to explore what kind of intersubjective aspects arise from their occurrence.

Linguistic typologists are also intrigued to discover the implications of how these strategies interact with other linguistic subsystems across semantic categories (Song 2018, 21–2). In the same spirit as previous typological studies on this topic (e.g. Knuchel 2019 for Kogi, and Bergqvist 2020 for Swedish), the present study aims to identify correlations observed between epistemic perspectives and grammatical categories, particularly intersubjective markers, and subject person. The reason for focusing on the subject person stems from the hypothesis that differences in referentiality and logophoricity between the two pronouns hän and se may explain constraints and preferences observed in their clitic usage with different activity performers. We thus pay special attention to the question of whether person plays a significant role in determining the selection of clitics in specific contexts. Our prediction is that there are clear correlations with person, which can be explained, for example, by epistemic authority; the speaker has epistemic authority about statements concerning themselves, while the epistemic authority lies with the second person in statements concerning the hearer and the referred third person. Therefore, we could predict, for instance, that =se is more common with second-person subjects, because with =se, epistemic authority is usually shared (see observations in Section 4.1.5 and discussion throughout Section 5).

Studies on these clitics, especially =se, hold significant importance and relevance in the field of Finnish linguistics, particularly because their use and occurrence in the actual language use have not been understood thoroughly from both grammatical and discourse-pragmatic perspectives. Traditional approaches in Finnish linguistics tend to categorise =se solely based on morphosyntactic criteria, often labelling it as a “resumptive pronoun” (Ojansuu 1922, 82, Itkonen 1966, 257, Larjavaara 1986, 307–10, Kiuru 1990, 289–90, Hakulinen 1999, 45, Vilkuna 1989, 145–7, Priiki 2015, 2017). The ambiguous status of =se is also reflected in the annotation solution observed in the main corpus data of the present study, the online social networking website Suomi24 Sentences Corpus 2001–2020 (Suomi24), in which the morphological analysis of =se is marked as ‘other unknown’ morpheme [OTHER_UNK]. In other words, its exact status has not been clear even to those responsible for building and analysing the corpus either. One of our objectives is to demonstrate that =se can be viewed as a discourse clitic expressing functions similar to those expressed by =hAn in many ways, although we will also show that =se is less grammaticalised as a genuine clitic than =hAn. At the same time, the investigation can also unveil some constraints and potential contexts of use for =hAn, which may have been overlooked in previous studies.

Regarding methodology, we employ two methods for data collection: 1) a questionnaire study and 2) a corpus search. These methods represent two distinct approaches to collecting data, typically used separately in different studies. However, in this study, combining them is a clear strength, given the goals of describing intersubjective uses. The questionnaire study is utilised for crowdsourcing potential functions of the two markers in the clause-second position, allowing for manipulation and surveying of diverse contexts of use. A subject person does not play a central role in the questionnaire study, but the functional range determined by actual Finnish language users is later used to explain varying frequencies of the two markers cooccurring with different subject persons, as quantitatively retrieved in the corpus search. The organisation of the article is as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of Finnish demonstratives and pronouns from a semantic and pragmatic perspective, focusing on the formal and functional differences between the two pronouns hän and se, as well as their respective clitic forms =hAn and =se. Section 3 delves into the notion of engagement in various languages, with a specific focus on the pragmatic extension observed in referential lexemes, equivalent to the Finnish pronoun-derived clitics =hAn and =se. In Section 4, the data collected through questionnaires and corpus studies in parallel reveal the interrelation between subject person and intersubjectivity marking in the usage of these clitics, the aspect not explicitly discussed in previous studies. The former qualitative approach, involving appropriateness judgement, accounts for the functions of the clitics, while the latter quantitative approach aims to detect correlations and significance in the frequencies of use. In Section 5, we synthesise the results and argue that different subject persons appearing in the discourse context may trigger the use of =hAn and =se in some cases, but the speaker’s choice, however, is not solely dependent on this grammatical category, as other semantic and pragmatic factors in some specific contexts may be more relevant, such as how the knowledge of a particular state of affairs is acquired and intended to be received by the hearer. Section 6 provides a summary of the findings and an evaluation of the method used in this study.

2 From pronouns hän and se to clitics =hAn and =se

This section discusses the two contexts of use, serving as a foundation for understanding the connections between the pronominal and clitic uses of hän and se. The introduction of the Finnish pronouns will highlight several corresponding characteristics, drawing from previous studies within the Finnish linguistics research tradition. Additionally, we make reference to the comparative studies of Uralic languages where relevant.

2.1 The Finnish demonstrative and personal pronoun system

The modern standard Finnish tripartite demonstrative system traces back to the reconstructed Proto-Finnic system reconstructed by Larjavaara (1986, 69–75), consisting of the following demonstrative paradigm, with the n-series being the plural forms: *tämä/*nämä(t) [proximal], *too/*noo(t) and *taa/*naa(t) [distal], and *se (< *śej)/*ne(t) [medial]. As introduced in Section 1, these demonstratives can also be used as third person pronouns alongside the primary third-person pronoun *hän. A consensus is that *hän likely goes back to the Proto-Uralic anaphoric pronoun *son, etymologically corresponding to Saami *sun and Mordvin *son ‘s/he’, for instance, even though the front-vowel harmony in Finnic *hän makes the case for a Proto-Uralic reconstruction rather controversial (SKES 1987[1955], 97–8, SSA 1992, 208). Alternatively, we can also consider that the reason for the front-vowel harmony in Finnic *hän is the result of analogy from the predominantly front-vowel pronoun paradigm, considering the symmetrical -e rhyme in the plural forms.

| 1sg | *minä | 1pl | *me |

| 2sg | *tinä | 2pl | *te |

| 3sg | *hän | 3pl | *he |

Regarding the semantics of the Finnish demonstratives, the classification may vary according to the research tradition. For instance, a spatiality-based approach (e.g. Diessel 2013) divides Finnish demonstratives into two distance categories: tämä as near to the speaker, while se and tuo as far from the speaker. Nevertheless, spatiality alone cannot explain the contrast between the non-proximal demonstratives se and tuo, because their difference is not exclusively based on the distance from origo, i.e. the speaker, but can also be alternatively classified based on logophoricity, i.e. how a referred entity is related to the speaker. Another interactional approach, meanwhile, rather pays attention to a discourse-sphere orientation: tämä for the speaker’s sphere, tuo for the remote sphere, and se for the hearer’s sphere (e.g. Laury 1997, 59–60). Lying between these two approaches, Larjavaara (1990, 95–100) illustrates that the three Finnish demonstratives can be classified on the basis of both spatiality and logophoricity: tämä as speaker-approximate, tuo as speaker-approximate and speaker-centred, and se as hearer-centred. In the current study oriented towards the emerging trend of engagement, our interpretation which we further use for analysing the clitic use of se is that se typically refers to a referent which is not in the speaker’s sphere, but the speaker uses it to draw the hearer’s attention and establish a joint attention (see also Evans et al. 2018b for the engagement-based approach to demonstratives).

When used as third-person pronouns, tämä and tuo, respectively, are referential devices referring to entities which are newly mentioned and currently being discussed. At the same time, se as well as hän have been analysed as referential devices serving an anaphoric function for an entity which is identifiable and mutually understood between the interlocutors (e.g. Etelämäki 2006, 14–5, 2009, Priiki 2017). Furthermore, previous studies have discussed the difference between hän and se, which relate to logophoricity (e.g. Saukkonen 1967, Laitinen 2002, 2005, Hakulinen et al. 2004, §1469, Priiki 2017). As illustrated in (2a) vs (2b), hän serves a logophoric function referring to a main clause activity performer, while se can also exophorically refer to another person.

| (2) | a. | Juhani | kerto-i | Marja-lle, | että | hän | tul-isi | sen | kanssa. |

| Juhani i | tell-pst.3sg | Marjaii-all | that | 3sg i | come-cond.3sg | 3sg ii .gen | with | ||

| ‘Juhani told Marja that he was coming with her.’ (Laitinen 2005, 76) | |||||||||

| b. | Juhani | kerto-i | Marja-lle, | että | se | tul-isi | hänen | kanssa. | |

| Juhani i | tell-pst.3sg | Marjaii-all | that | 3sg ii | come-cond.3sg | 3sg i .gen | with | ||

| ‘Juhani told Marja that she was coming with him.’ (Laitinen 2005, 76) | |||||||||

In (2a) and (2b), the logophoric hän refers to the main activity performer, Juhani, the opposite of which, Marja as the message recipient, is referred to with se (see also Ikola 1960, 19–63).

In any case, the functions of the two pronouns may vary across discourse situations and can sometimes overlap across contexts of use (Hakulinen et al. 2004, §1470). In narratives, for instance, the speaker uses hän to switch their role as narrator to the participant of the discourse and to express attitudinal functions when referring to a person with politeness, negligence, wonder, or suspicion (Vilppula 1989, 398–9). What is relevant for the analysis of their clitic uses is that hän refers to entities in a higher degree of the interlocutors’ attention with a broader range of epistemic status and speech acts, while se has a stronger referential force for capturing the hearer’s attention and managing contrast among identifiable entities.

2.2 Formal and functional comparison between =hAn and =se

The clitic uses of hän and se in the function of expressing interlocutors’ (inter)subjectivity show several differences when it comes to the questions of form and function. In the actual language use as described in the Finnish reference grammar (Hakulinen et al. 2004, §827, §830–2) and as observed in the Suomi24 corpus, formal differences between =hAn and =se can be generalised in the aspects described below. The generalisation in this section is supported by quantitative data from corpus search where relevant (see the full quantitative data later in Section 4.2).

In terms of morphology, =se may inflect for number in its plural form =ne from ne ‘those; they’, as being contrasted in Examples (3) and (4), while =hAn does not inflect in the plural form **=he, which would be the normal plural form of the pronoun hän:

| (3) | Meijän | poika=se | anto-i | tahto-nsa | vaimo-n | tasku-un! |

| our | boy= se | give-3sg.past | wish-poss.3 | wife-gen | pocket-ill | |

| ‘Our son gave up his wish for his wife!’ (Suomi24, 2005 sub-corpus) | ||||||

| (4) | Kato | pojat=ne | halua-a | viettää | tyttö-jen | ilta-a:D |

| look | boy= ne | want-3sg | spend | girl-pl.gen | evening-part | |

| ‘Look, boys want to spend a girls’ night:D’ (Suomi24, 2012 sub-corpus) | ||||||

Plural form =ne, however, occurs mainly with common nouns, as the plural form =ne does not co-occur with plural pronouns alone without =hAn although the frequencies are extremely low (see Appendix 1). In relation to subject persons, =se is sensitive to the person in the plural as the forms like me=se [2sg=se] (à 38/101,979 occurrences) or te=se [2pl=se] (à 61/109,972 occurrences) are rare but not impossible, as shown in Examples (5) and (6). Meanwhile, the occurrence of =hAn is not restricted by person in any way.

| (5) | Te=se (**Te=ne ) | tiedä-tte | mikä | on | totuus. |

| 2pl= se | know-3pl | what | be.3sg | truth | |

| ‘You know what the truth is.’ (Suomi24, 2002 sub-corpus) | |||||

| (6) | He=se (**He=ne ) | pyörittä-vät | Suome-a | sitten-kin | |

| 3pl= se | turn-3pl | Finland-part | then-too | ||

| kun | ole-t | vanha | ja […] | ||

| when | be-2sg | old | and | ||

| ‘They will run Finland then when you are old and […]’ (Suomi24, 2012 sub-corpus) | |||||

Regarding the host attachment, =hAn can co-occur with any part of speech, including adverbials (7) and verbs (8), while there are clear restrictions on the use of =se, such as after numeral **kolme=se [three=se].

| (7) | Sinulla=han | ol-i | se | kartta? |

| 2sg.ades= han | be-3sg.past | that | map | |

| ‘You had that map?’ (Suomi24, 2001 sub-corpus) | ||||

| (8) | Totta kai, | ole-t=han | Suome-n | paras | ajaja. |

| of_course | be-2sg= han | Finland-gen | best | driver | |

| ‘Of course, you are Finland’ best driver.’ (Suomi24, 2001 sub-corpus) | |||||

As for constituent order, =hAn always precedes =se if both simultaneously occur on a word, yielding a conjoint form =hAn=se as in Example (9) (see also Karttunen 1974 for the organisation of multiple clitics in Finnish).

| (9) | Te=hän=se | väitä-tte | ihmise-n | synty-ne-en | muda-sta. |

| 2pl= han = se | claim-2pl | human-gen | be_born-ptcp.past-gen | mud-elat | |

| ‘You claim that human was born from mud.’ (Suomi24, 2019 sub-corpus) | |||||

In orthography, =hAn is always written as a part of the host word minahän [1sg.han], which is not the case for =se almost exclusively written as a separate word. However, conjoint forms are also observed in the corpus: minäse [1sg.se] (à 9/101,979 occurrences), sinäse [2sg.se] (à 27/109,972 occurrences), and hänse [3sg.se] (à 31/120,386 occurrences), albeit the annotators of the Suomi24 corpus, interestingly, leave the morphological analysis of these forms undefined as ‘other unknown’ morpheme [OTHER_UNK].

Based on the observations above, it seems that =hAn has been grammaticalised and normativised as a genuine clitic to a larger extent (as recognised in Hakulinen et al. 2004, §830). The higher degree of grammaticalisation is manifested also in the fact that the form and function of =hAn have been studied more extensively (e.g. Liefländer-Koistinen 1989, Duvallon and Peltola 2012, 2013, Duvallon 2014), while there are practically no studies dedicated to the formal and functional description of =se. From the usage-based perspective, the frequency of use regarding the two clitics in the corpus also confirms this view, as =hAn appears in 85.83% of co-occurrence with personal pronouns, but only 11.06% for =se, and 3.11% for the conjoint form =hAn=se (see Section 4.2). Related to the last point in the observation above, the different degrees of grammaticalisation between the two clitics are also reflected in how Finnish language users spell out these in written forms, given that =se written as part of a word as sinäse [2sg.se] is very rare, as it is usually written separately from its host word as sinä se [2sg se].

In terms of functions, previous studies consider =hAn as the speaker’s stance-taking device which the speaker uses for drawing the hearer’s attention to a specific state of affairs (e.g. Halonen 1996, Hakulinen et al. 2004, §830–2, Duvallon and Peltola 2012, 2013, Duvallon 2014). This at least to some extent resembles the description of the Swedish ju (Bergqvist 2020). Typical context of the use of =hAn concerns statements about topics which are related to knowledge, view, or assumption on the given state of affairs, often being shared between the interlocutors and for which the speaker expects some feedback or following actions from the hearer. This concerns speech act functions, such as disagreement (10), seeking confirmation, reminder, or warning (11).

| (10) | A: | Norja | ei | ole | kallis | maa. |

| Norway | neg.3sg | be.cng | expensive | country | ||

| ‘Norway is not an expensive country.’ | ||||||

| B: | Norja=han | on | kallis | maa. | ||

| Norway= han | be.3sg | expensive | country | |||

| ‘Norway is an expensive country!’ [I do not agree with you!] (Elicitation) | ||||||

| (11) | Mitä! Oletko sinä syömässä tuota, ethän sinä voi, koska […] | |||

| ‘What! Are you going to eat that, you cannot, because […]’ | ||||

| Sinä=hän | ole-t | allerginen | kala-lle. | |

| 2sg= han | be-2sg | allergic | fish-ALL | |

| ‘You are allergic to fish.’ [mind you!] (Elicitation) | ||||

In contrast, there is previously no study specifically on functions of =se, but functions of its partitive form sitä have been discussed to a certain extent (Hakulinen 1975; Hakulinen et al. 2004, §827). As the use of sitä described in previous studies resembles the results obtained from the investigation of =se in the current study (Sections 4 and 5), we see a good reason to provide the following description which is applicable for both forms. Namely, they construct a claim based on concrete observable evidence, referring to a state of affairs which the speaker expected to occur (12a), against counter-expectation marked by =hAn in (12b), or bringing an inclusively or exclusively observed state of affairs to inclusive attention with the hearer (13). The Finnish linguistics literature also suggests several other affective meanings for sitä, which can express a playful or disapproval attitude.

| (12) | a. | Nyt=se | sataa. |

| now= se | rain.3sg | ||

| ‘Now it is raining’ [as I/we expected] (Elicitation) | |||

| b. | Nyt=hän | sataa. | |

| now= han | rain.3sg | ||

| ‘Now it is raining’ [I/we did not expect that coming] (Elicitation) | |||

| (13) | Räikkönen=se | vaan | tul-i | toise-na | maali-in!!!! |

| Räikkönen= se | only | come-3sg.past | second-ess | finish_line-ill | |

| ‘Räikkönen only finished second.’ [just as we saw in the race] (Suomi24, 2012 sub-corpus) | |||||

The marker =se (and its partitive form sitä), accordingly, behaves as a marker for confirming novel information or pointing out contrast against other alternatives, as is expected from its properties inherited from the demonstrative origin (Himmelmann 1996 discussed in Section 2.3).

The description of the two clitics will establish a baseline for exploring other potential functions of =hAn and =se using the data in Section 4, which will provide concrete evidence of functional resemblances between =se, described in this study, and sitä as discussed in the Finnish linguistics research literature. Before delving into the data analysis, Section 3 will discuss and establish the framework of engagement as a tool for subsequent analysis.

3 Previous accounts on the grammatical marking of engagement

This section introduces the framework of engagement (Section 3.1), within which a typology of epistemic perspectives and the interlocutors’ engagement has been developed (Section 3.2). We also discuss the pragmatic extension of referential lexemes towards markers of engagement, drawing insights from studies of several individual languages (Section 3.3).

3.1 Introduction of engagement as a functional category

The concept of engagement was introduced to describe a linguistic phenomenon of intersubjective and epistemic management involving the interlocutors’ knowledge and attention in the discourse, initially under the French term assertif by Landaburu (1979, 111–26, 2007) for Andoke, an Amazonian language spoken in Colombia. Andoke has four different verb prefixes for signalling contrastive configurations of the speaker’s (S) and the hearer’s (H) epistemic perspectives in terms of certainty towards a state of affairs (+ yes vs − no): 1) kē- = catégorique [S+H−], 2) b- = positif [S+H+], 3) k-/d- = non-savoir [S−H+], and 4) ma- = probable [S−H−] (see a further typological classification in Section 3.2).

The phenomenon is also observed in other Amazonian languages, such as Nambikwara and Kogi, as shown in Examples (14) and (15).

| Nambikwara (Nambikwaran: Western Brazil) | ||

| (14) | a. | wa 3 ko 3 n-a 1 -Ø-wa 2 |

| work-1- excl -impf | ||

| ‘I am working.’ [exclusive, S+H−] | ||

| b. | wa 3 ko 3 n-a 1 -ti 2 .tu 3 -wa 2 | |

| work-1- shrd -impf | ||

| ‘(You and I see that) I am working.’ [shared, S+H+] (Kroeker 2001, 63–4) | ||

| Kogi (Arwako: Colombia) | ||||

| (15) | a. | nas | hanchibé | sha-kwísa=tuk-(k)u. |

| 1sg.ind | good | adr.asym-dance=be.loc-1sg | ||

| ‘I am dancing well (don’t you think?)’ [in your opinion, S−H+] | ||||

| b. | kwisa-té | shi-ba-lox. | ||

| dance-impf | adr.sym-2sg-be.loc | |||

| ‘You are/were dancing (right?)’ [confirming, S+H+] (Evans et al. 2018b, 144) | ||||

In Nambikwara, an unmarked declarative utterance in (14a) may assume the speaker’s authority on a state of affairs, while the use of a morpheme -ti 2 .tu 3 - in (14b) marks the information as shared between both the speaker and the hearer. In (15a), in turn, the speaker expects the hearer to know x while the speaker is unaware of x, indicating hearer authority. Meanwhile, in (15b), the speaker expects the hearer to know x, and the speaker knows x too, pointing towards the interlocutors’ shared knowledge. The epistemic (a)symmetry between the speaker and hearer is thus encoded in Kogi morphologically with two distinct morphemes: sha- [asymmetrical] vs shi- [symmetrical]. Examples (14) and (15) bring into attention the two aspects of interlocutors’ intersubjectivity: 1) epistemic authority and 2) epistemic (a)symmetry (see the most recent view on these epistemic contexts in Section 3.2).

Observations of different strategies to code the distribution of knowledge between interlocutors in individual languages lead to a cross-linguistic studies and typological conceptualisation of engagement by Evans et al. (2018b).

Engagement refers to a grammatical system for encoding the relative accessibility of an entity or state of affairs to the speaker and addressee. (Evans et al. 2018b, 142)

In its intersubjective sense, engagement targets the epistemic perspectives of the speech act participants, signalling differences in the distribution of knowledge and attention between the speaker and the hearer (see also a similar concept of ‘territory of information’ in the study by Kamio 1997). As such, it specifies whether information is shared or exclusive to one of the speech act participants (Bergqvist and Kittilä 2020b), as illustrated in Nambikwara examples (14a) vs (14b).

Asymmetry evolving in the interlocutors’ states of knowledge and attention can also be utilised as a means for the speaker to take or give epistemic authority to the hearer (Evans et al. 2018a, 118), as is seen in Kogi Examples (15a) vs (15b). This phenomenon has some resemblances to the degree and hierarchy of accessibility and givenness observed in the use of (in)definite articles and possessive pronouns (see a synthesis shown in Abbott 2004, 122–4). From the perspective of intersubjectivity, (in)definite articles and possessive pronouns can express a neutral state (16a) or (a)symmetry of knowledge and attention between the interlocutors (16b, 16c).

| English (Germanic, Indo-European: United Kingdom, etc.) | ||

| (16) | a. | Get me a red jacket. |

| (Any jacket you can find.) | ||

| b. | Get me the red jacket. | |

| (That jacket which you have seen me wearing.) | ||

| c. | Get me my red jacket. | |

| (That jacket which you have seen me wearing and know it is mine.) (Ellicitation) | ||

The use of indefinite article in (16a) is inquired by the speaker that the mentioned entity is not in the hearer’s attention yet, while the use of definite article in (16b) presumes that the hearer is already aware of the entity being specific among other possible identifiable alternatives through presupposition from the earlier discourse context. The use of possessive pronoun in (16c), on the one hand, entails that the hearer has the mentioned entity in awareness and memory, but the speaker, on the other hand, ensures that the hearer can recognise this specific entity by using an explicit expression through possession.

3.2 Towards a typology of epistemic perspectives and the interlocutors’ engagement

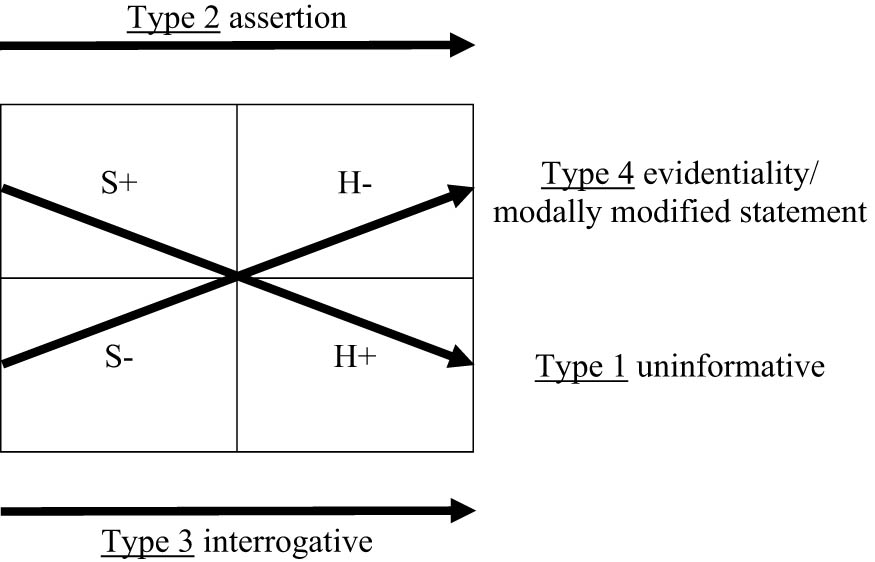

The attempt to typologise the engagement system based on epistemic perspectives between the interlocutors was already present as a quadripartite typology in the Andoke grammar by Landaburu (1979, 119, 2007) and has been recently put forward towards an operationalisation by Grzech (2022). The classification is based on how epistemic authority (+ yes vs − no) is distributed among the speaker (S) and the hearer (H), as mapped in Figure 1. Note that the original version by Grzech (2022) has A(ddressee) for the message receiver, instead of H(earer) used in the present study for the same purpose.

Knowledge distribution in interaction (adapted from the study by Grzech 2022).

Type 1 is labelled as ‘uninformative’ (positif in Landaburu 1979) which relatively well captures the informativeness status of the case, that is, an expressed proposition is not novel and provides no new information for either of the speech act participants [S+H+]. However, the rather uninformative nature of these statements does not mean that they are irrelevant to the discourse and would not be attested in normal language use. An example is provided, for example, by an evaluation scene where the two interlocutors have the same information, and they compare pieces of information with each other. No new information is provided, but the communication still has a clear goal.

Type 2, ‘assertion’ (catégorique in Landaburu 1979), is perhaps the most expected pattern of natural communication since the speaker holds the epistemic authority and informs the hearer of a novel piece of information [S+H−].

In Type 3, ‘interrogative’ (non-savoir in Landaburu 1979), the speaker is searching for information themselves and believes the hearer to have the required/necessary information [S−H+].

As for Type 4, ‘evidentiality’ (probable in Landaburu 1979), neither the speaker nor the hearer has epistemic authority [S−H−], which means that no real exchange of information takes place (neither provides, nor receives any novel information). However, the evidentiality type of context is also rather common and is attested in cases where the interlocutors speculate about possible outcomes of events. For example, before a (live) sport event, neither the speaker nor the hearer can actually know who is going to win the competition, but for the sake of interpersonal communication, it may nevertheless be interesting to speculate about the result. This type also shows that communication is not only for conveying (novel) information from the speaker to the hearer, but it has numerous other conversational functions.

In any case, not all languages have dedicated grammatical markers for all types of epistemic perspectives like Andoke (as described in Landaburu 1979, 2007), and some of them can be inferred from contexts. For instance, English speakers use tag questions for expressing Types 1 and 4, while Types 2 and 3 are interpreted from simple assertive and interrogative statements. Upper Napo Kichwa, in turn, has dedicated verb endings to express each of the types above, as shown in Example (17) where (17a) is a baseline context while the subsequent examples give extended epistemic contexts which may correspond to some of the types discussed above.

| Upper Napo Kichwa (Quechuan: Ecuador, Colombia, Peru) | |||||

| (17) | a. | Llaktay feria tiawn. | ‘There is a market going on in town.’ | Epistemic authority | Knowledge/awareness |

| b. | Llaktay feria tiawn-mi. | id. [and you did not expect that] | S+H− | S+H− | |

| c. | Llaktay feria tiawn-dá. | id. [as you suspected I would know] | S+H− | S+H+ | |

| d. | Llaktay feria tiawn-mari. | id. [as you should know] | S+H+ | S+H− | |

| e. | Llaktay feria tiawn-cha. | id. [possibly, I suspect/do not recall] | S+H−/ | S−H−/ | |

| (Adapted from Grzech 2016, 2022) | S−H+ | S+H+ | |||

As is shown in (17), the proposed framework based on epistemic authority and (a)symmetry allows for a more specific description of epistemic contexts across languages and for tracing the pragmatic extension of grammatical elements towards engagement.

3.3 A cross-linguistic view on pragmatic extension towards engagement

Observations on grammatical marking of interlocutors’ knowledge and attention in individual languages in an engagement-like fashion were made previously in connection to various domains of language structure and discourse, such as time (tense), attention (accessibility), knowledge (epistemic authority), and identifiability (determiner) (as given by Evans et al. 2018b, and see Grzech 2022 for epistemic authority). Given the intersubjective nature of engagement, the pragmatic extension towards engagement uses often involves constructions with etymologically referential lexemes, particularly deixis (Janssen 2002, Diessel 2006, Kratochvíl 2011) and person (Dahl 2000, Bergqvist and Knuchel 2017, Schultze-Berndt 2017, Knuchel 2019, Bergqvist 2020).

Such a tendency of referential elements becoming markers of engagement likely roots in deictic and anaphoric characteristics of these semantic categories, which have developed discourse-pragmatic uses as cognitively determining the positional engagement of speech act participants from the state of affairs involved. In other words, something that is deictically closer to the speaker can also be viewed as being cognitively closer to the speaker’s knowledge, attention, and stance. This has a close relation to what Himmelmann (1996) labels as a ‘recognitional use’ of demonstratives in the following principle.

Recognitional use … involves reference to entities assumed by the speaker to be established in the universe of discourse and serves to signal the hearer that the speaker is referring to specific, but presumably shared, knowledge. It invites the hearer to signal the need for further clarification regarding the intended referent or to acknowledge that he or she, in fact, knows what the speaker is talking about. (Himmelmann 1996, 240)

This is one clear instance of inherited semantics, which undergoes an extension towards more advanced pragmatic uses in the universe of discourse. Such a mechanism of pragmatic extension is the case for the Finnish clitics =hAn and =se investigated in the current study. In particular, hän as an anaphoric pronoun pointing to neither the speaker’s nor the hearer’s spheres makes it accessible to both speech act participants, corresponding to the recognitional characteristic described above.

Previous studies on the engagement-like uses of various etymologically referential words also report similar findings beyond the South American languages discussed in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, for instance, for Swedish particles ju and väl (Aijmer 1977, 1996, Eriksson 1988, Teleman et al. 1999); Spanish independent si conditional clause (Schwenter 1996); German modal particles ja, wohl, doch, and etwa (Waltereit 2001, Gast 2008); Abui free-standing demonstratives (Kratochvíl 2011); Vietnamese demonstrative-derived sentence-final particles (Lê 2002, Adachi 2016); and Finnic and North Russian postposed demonstratives, respectively, -se and -to (Yurayong 2020), among others. These studies have shown that the mentioned markers of engagement participate in the epistemic management of the availability and exclusivity of interlocutors’ knowledge and attention through inclusive and exclusive experiences.

Note that in some other languages, interlocutors’ engagement in the discourse, involving attitude and control of epistemic perspectives, can also be coded in verbal conjugation, distinguished between the interlocutors’ opinion (egophoric) and a matter of fact (allophoric) (Bergqvist and Knuchel 2017, 369). This has been initially reported as the case for Kathmandu Newar (Hargreaves 1991), and later scholars also make similar remarks in languages of their expertise, particularly South American and Sino-Tibetan languages (see the collective volume on egophoricity in Floyd et al. 2018). However, such grammatical strategies will not be discussed in the present study which exclusively focuses on grammatical elements derived from referential lexemes.

To discuss several significant case studies, investigation on the co-occurrences of intersubjective markers, derived from referential words and serving the function of expressing interlocutors’ engagement, has been previously conducted by Bergqvist (2020) for Swedish modal particles ju and väl, the basic functions of which are illustrated in Examples (18) to (20). Note that it is ju which is derived from an indexical element: Swedish ju ∼ Danish jo ← Middle Low German jo < Proto-Germanic *ja ‘thus, so’, while väl is a cognate to English well, sharing the same root as will, in the sense of ‘something desirable’.

| Swedish (Germanic, Indo-European; Sweden) | |||||||

| (18) | Din | bror | har | ju | varit | i | Kina. |

| your | brother | have.prs | ju | be.prf | in | China | |

| ‘Of course, your brother has been to China.’ [reminder] (Teleman et al. 1999, 114, as cited in Bergqvist 2020, 481) | |||||||

| (19) | Där | är | du | ju! |

| there | be.prs | you | ju | |

| ‘There you are!’ [mirative connotation] (Aijmer 1977, 210, as cited in Bergqvist 2020, 483) | ||||

| (20) | Den | där | klänning-en | var | väl | dyr? |

| dem | there | dress-def | be.past | väl | expensive | |

| ‘That dress was expensive, right?’ [confirmation of the known fact/shared knowledge] (Teleman et al. 1999, 114, as cited in Bergqvist 2020, 483) | ||||||

The results (Bergqvist 2020, 490) show that ju as a marker for epistemic asymmetry [S>H+] in (18) or lack of attention, i.e. mirative use [S−H−] in (19), co-occurs with subject persons in the following order from most to least frequently: third person (49%) > first person (37.5%) > second person (13.5%). Regarding väl in (20) as a marker for epistemic symmetry [S+H+], the order from most to least frequent co-occurrence is as follows: second person (39%) > third person (32%) > first person (28%). In this respect, there is a similar frequency trend between the Swedish väl and Finnish =se, which might be due to their functional similarity as markers of hearer-oriented shared stance, yielding epistemic symmetry between the interlocutors. At the same time, the frequencies point to the fact that the Swedish ju is more common with second and third persons than with first person (see similar results for Finnish in Section 4).

Another interesting parallel is Vietnamese sentence-final particles which derive from demonstratives. The spatial dimensions of demonstratives namely extend their indexical and referential uses to the discourse-pragmatic domain for expressing interlocutors’ engagement, the pragmatic extension previously discussed by Adachi (2016), as summarised in Table 1.

Pragmatic extension of Vietnamese demonstratives in the sentence-final use (based on Adachi 2016)

| Indexical and referential uses | Proximal | Medial | Medial | Distal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (independent) | (independent) | (adnominal) | (independent and adnominal) | |

| Form | đây | đấy | ấy/ | kia/ |

| ý (reduced form) | cơ (reduced form) | |||

| Sentence-final use | Speaker-centred | Hearer-oriented | Shared knowledge | Counter-expectation |

Differences in sentence-final uses of the demonstratives are given in Examples (21) to (24).

| Vietnamese (Vietic, Austroasiatic: Vietnam) | ||||

| (21) | An employee complains how difficult the assignment that she is working on is. | |||

| bài | này | khó | đây . | |

| assignment | dem.prox.adnom | difficult | dem.prox | |

| ‘This assignment is difficult as far as I can see.’ [speaker-centred] (Lê 2002, 60) | ||||

| (22) | The mother is telling a news to her daughter about her friend being transferred to another class, which the mother assumes that her daughter might not know about this. | ||||||

| à, | Hương, | nó | bị | chuyển | lớp | đấy. | |

| intj | Hương | she | pass | transfer_to | class | dem.med | |

| ‘Ah, Hương, she was transferred to another class which you may not know about, but may be interested to know.’ [hearer-oriented] (Adachi, 2016) | |||||||

| (23) | The mother is talking to the father about popular Vietnamese souvenirs among Japanese tourists. As they have many Japanese friends in common, she assumes that he will understand what she means. | |||||

| người | Nhật | thích | ăn | phở. | ||

| people | Japanese | like | eat | rice_noodle | ||

| phở | ăn | liền | ý. | |||

| rice_noodle | eat | instant | dem.med | |||

| ‘The Japanese like rice noodle, to be exact, instant rice noodle, you know.’ [shared knowledge] (Adachi, 2016) | ||||||

| (24) | The mother is telling the father about their mutual friend’s son going to New York and how expensive his parents had to pay for the flight tickets. | ||||

| cái | kia | đắt | lắm. | ||

| clf | dem.dist.adnom | expensive | very | ||

| những | hai | nghìn | mấy | cơ. | |

| some | two | thousand | several | dem.dist | |

| ‘(In fact,) that ticket was very expensive. It cost more than 2,000 (US dollars), more expensive than you would expect.’ [hearer’s counter-expectation] (Adachi, 2016) | |||||

The proximal đây in (21) recurs the statement to the employee’s attitude towards the difficulty of the assignment evolving from her direct experience [S+H−], whereas the medial đấy in (22) expresses the mother’s inference on the interest and relevance of the statement to her daughter [S<H+]. In (23), the other adnominal medial ý emphasises the sharedness of the knowledge between the two interlocutors [S+H+]. As for (24), the distal cơ expresses epistemic asymmetry between the speaker and hearer, with the speaker holding a higher degree of knowledge over what could be the hearer’s counter-expectation [S>H+], i.e. mirative use (DeLancey 1997).

Comparing the Vietnamese sentence-final demonstratives to the two Swedish particles, Vietnamese proximal đây and Swedish ju have some functional properties in common. For these speaker-oriented markers, all of them typically express the epistemic asymmetry between interlocutors often entailing the involvement of the first person as a speech act participant who takes their own stance [S+H−/S>H+]. In presenting the known fact about the third person to the hearer, however, the Swedish ju may also express the interlocutors’ symmetry of not having the authority and knowledge on a state of affairs in the mirative uses [S−H−], which would correspond to one of the functions of the Vietnamese distal kia/cơ (see remarks below).

In contrast, the Vietnamese medial adnominal ấy/ý is more comparable to the Swedish väl in the sense that they base the uttered statement on interlocutors’ shared knowledge yielding epistemic symmetry [S+H+], with a stronger orientation towards the hearer sphere. They more often appear in statements related to the second > third person, crucially not the speaker (i.e. first person), or to their joint knowledge and attention. For Vietnamese, this might result from the semantics of its lexical form as medial demonstrative, which can also be alternatively analysed as hearer-centred demonstratives, thereby signalling the involvement of the second person in the epistemic sphere of the discourse.

As for the Vietnamese medial đấy (independent), it differs from the medial adnominal ấy/ý and Swedish väl in that its intersubjective status is epistemic asymmetry with the hearer holding a stronger degree of epistemic authority and knowledge [S<H+]. Meanwhile, the distal kia/cơ differs from the proximal đây and Swedish ju in that it can point towards either symmetry or asymmetry and with no person orientation due to its original deictic distality, while the epistemicity degree can be absent in the case of mirative uses [S−H−], or higher towards the speaker when attempting at establishing joint attention [S>H+].

The comparison between Swedish and Vietnamese reveals that languages with a larger set of intersubjective markers, such as Vietnamese, can distribute dedicated engagement functions more specifically across various grammatical resources. In contrast, languages with less extensive intersubjectivity marking, like Swedish, may employ a single marker for multiple epistemic contexts. In such cases, the contextual interpretation, including interrogatives, becomes a factor when determining its function.

Next, we go beyond the epistemic (a)symmetry issues to explore in the Finnish data whether subject persons play any role similar to the description and specific Swedish and Vietnamese cases as discussed in this section.

4 Subject persons in the intersubjective uses of Finnish clitics =hAn and =se

This section presents results from the two data sources: 1) the questionnaire and 2) the corpus. The methodological choice stems from the previously mentioned fact that =se, in particular, has not been adequately described in previous research. To reduce the potential bias introduced by the authors’ language intuition and interpretation, the present study uses appropriateness judgement by language users and usage-based frequencies as criteria to maximise the identification of contexts of use. While frequency alone is not the sole criterion for determining grammaticalisation, we contend that it still provides a piece of evidence for the higher degree of grammaticalisation of =hAn over =se, as hypothesised in Section 3.

4.1 Appropriateness judgement by language users

Based on the observation of formal and functional differences presented in Section 3, we further examine the validity of interrelation between the clitics =hAn and =se, and other functional categories. The first part of the study is conducted through appropriateness judgement among 35 bachelor’s and master’s students at the Department of Languages, Faculty of Arts, University of Helsinki, who are L1 and L2 speakers of Finnish. The language of instruction in the course where the test was conducted is Finnish, which means that the level of command of Finnish of all participants is very high, although there were also a couple of non-native Finnish speakers in the teaching group.

The participants were asked to choose which of the two markers, =hAn or =se, fit better in given contexts of use. They could also voluntarily provide more specific explanations as to why one marker was more suitable in the context than the other. The questionnaire includes 40 questions, featuring very different kinds of scenarios with very different kinds of evidence. We chose both contexts which, in our own view, clearly favour =hAn and contexts, where, again based on our subjective evaluation, =se is clearly more appropriate. In addition, we also created scenarios, where both seem more or less equally likely and scenarios between all these types. The scenarios varied, for example, based on whether the evidence is concretely present or not and whether the speaker expects the hearer to share the given information or not. Moreover, the grammatical person varied between the scenarios.

Each question is given in the same format, starting with a given context and then the reaction in which the clause-second slot is left blank for the selection between =hAn and =se. This should make the genre of the questionnaire comparable to the corpus part of the study, based on the online social networking website Suomi24 used in Section 4.2, as the internet discussion is similarly structured in such a pattern in which the first post stimulates reactions from the audience.

Suomi24 discussion interface (https://keskustelu.suomi24.fi/t/17595758/olen-sekoillut-suomi24ssa).

The results show crowdsourced tendencies whether =hAn or =se is preferred in the given contexts. The answers from 35 participants are organised in a three-value-based form: =hAn = 0, both = 1, and =se = 2. The results are subsequently accumulated, according to which the use of =hAn is preferred among the participants when the average is closer to 0, and vice versa closer to 2 for =se. In this section, we discuss the occurrence of =hAn and =se in connection to different subject persons. We primarily provide quantitative results based on the frequency of uses with a brief summary of the participants’ comments on the appropriateness of the markers in given contexts, while the qualitative analysis of interrelation between markers of engagement and subject persons will follow in Sections 5 and 6.

4.1.1 Contexts with first person

First person means in the present context that a first-person referent appears in the actor or participant role on the reaction line. Two illustrative examples are provided in (25) and (26).

| (25) | Menet kaverisi kanssa ravintolaan ja huomaat, että sinulla on huomattavasti hienommat vaatteet kuin kaverilasi. Toteat hänelle: | Context |

| Q5 | ||

| ‘You go to a restaurant with a friend, and you notice that you are overdressed compared to your friend. You say to him/her’: | ||

| Meidän___ piti laittaa tänään hienot vaatteet päälle | Reaction | |

| ‘We___ were supposed to dress up tonight.’ | ||

| Average: 0 (=hAn exclusively preferred) | ||

| (26) | Olette kumppanisi kanssa miettineet omakotitalon ostamista, ja kumppanisi on löytänyt hienon ja halvan talon Sauvosta. Vaikka kumppanisi yrittää kertoa, kuinka hienoa olisi asua Sauvossa, hän ei saa sinua vakuutetuksi ja lopulta toteat: | Context |

| Q24 | ||

| ‘You and your spouse have been thinking about buying a house, and your spouse has found a nice and affordable house in Sauvo. Even though your spouse is trying to convince you of how wonderful it would be to live in Sauvo, s/he fails in convincing you and in the end, you say’: | ||

| Usko nyt jo, minä___ en minnekään takahikiälle muuta! | Reaction | |

| ‘Hear me out, I will___ not move to the middle of nowhere.’ | ||

| Average: 0.14 (=hAn strongly preferred) | ||

Across the contexts with the first person, =hAn is more common, with an average of 0.37. In most of the contexts given in the questionnaire, the subject is in the first-person singular minä, and the average for these cases is 0.43, while the average is 0 for the only case where the subject is first-person plural. This could also potentially be explained by the fact that it is not common for =se to co-occur with plural personal pronouns (as stated in Section 3.1).

4.1.2 Contexts with second person

In contrast to the first person, all the contexts with the second person in the questionnaire have the subject in singular sinä. Two examples are given in (27) and (28).

| (27) | Kaverisi haluaa välttämättä maistaa Carolina reaperia, maailman vahvinta chiliä, vaikka hän yleensä haukkoo henkeään, kun laittaa ruokaan hiukan Tabascoa. Yrität selittää hänelle, että Carolina reaper on noin 500–700 kertaa vahvempaa kuin Tabasco, mutta kaverisi kuitenkin väkisin maistaa sitä ja 20 sekunnin päästä hän haukkoo henkeään ja hikoilee punaisena. Sanot hänelle: | Context |

| Q25 | ||

| ‘Your friend insists on tasting Carolina Reaper, the hottest chili in the world, even though s/he usually has problems, whenever s/he puts some Tabasco in his/her food. You try to explain to him/her that Carolina reaper is round 500–700 hotter than Tabasco, but your friend nevertheless tastes the chili, and in 20 seconds s/he is all sweaty and out of breath. You say to him/her’: | ||

| Sinä___ et usko millään mitään | Reaction | |

| ‘You___ never believe anything.’ | ||

| Average: 1.83 (=se strongly preferred) | ||

| (28) | Mietitte sitä, kuka voisi käydä huomenna hakemassa työpaikallenne tilatun paketin. Toteat kollegallesi: | Context |

| Q7 | ||

| ‘You are thinking about who could pick up a packet ordered to your office tomorrow. You say to your colleague’: | ||

| Pekka, sinä___ asut lähellä Hakaniemeä | Reaction | |

| ‘Pekka, you___ live close to Hakaniemi.’ | ||

| Average: 0.03 (=hAn strongly preferred) | ||

As the averages show, the use of the studied clitics is very different in Examples (27) and (28). The general average for the second person is 0.87, which means that =hAn is still more common with the second person, as is also suspected in the first person, but the differences between the clitics are not as clear as for the first person. This implies that it is not only the second person which solely determines the use of either clitic.

4.1.3 Contexts with third person

Third person comprises here all the cases where the subject represents third person regardless of whether we are dealing with third-person pronouns or with nouns (which all naturally represent the third person). Two examples of third person are found in (29) and (30).

| (29) | Ystäväsi Liisa on hakenut professorin paikkaa, vaikka hän ei ole vielä tohtori. Toteat kaverillesi: | Context |

| Q33 | ||

| ‘Your close friend Lisa has applied to a professor position, even though she is not a doctor yet. You say to another friend’: | ||

| Liisa___ ei ole tohtori vielä | Reaction | |

| ‘Lisa___ is not a doctor yet.’ | ||

| Average: 0.09 (=hAn strongly preferred) | ||

| (30) | Kalle on haastanut Villen sulkapallopeliin seuraavan viikon lauantaina tietämättä sitä, että Ville on entinen sulkapalloammattilainen ja Kalle itse on pelannut peliä vasta viikon. Sanot kaverillesi: | Context |

| Q37 | ||

| ‘Carl has challenged Bill to a game of badminton next Saturday without knowing that Bill is a former badminton pro and Carl has played the game only for a week. You say to a friend’: | ||

| Kalle___ tulee saamaan kunnolla köniinsä ensi lauantaina. | Reaction | |

| ‘Carl___ will suffer a devastating loss next Saturday.’ | ||

| Average: 1.24 (=se preferred) | ||

In the two examples above, the averages are very different, as =hAn is clearly more common in (29), while =se is somewhat more common in (30). In any case, =se in general co-occurs slightly more frequently with the third person, the average being 1.11.

4.1.4 Contexts with impersonal construction

Impersonal constructions comprise here (and in general in linguistics) cases which lack a grammatical subject, such as weather verbs (see a typology of impersonal constructions in Malchukov and Ogawa 2011). Two examples of impersonal constructions are (31) and (32).

| (31) | Edellisenä päivänä on satanut paljon ja yöllä on ollut kunnolla pakkasta. Menet hakemaan postia ja palattuasi kerrot kumppanillesi: | Context |

| Q12 | ||

| ‘It has rained a lot the previous day, and it has been really cold the last night. You go out for the mail and when you get back, you say to your spouse’: | ||

| Siellä___ on liukasta. | Reaction | |

| ‘It is___ slippery out there.’ | ||

| Average: 0.06 (=hAn strongly preferred) | ||

| (32) | Olette menossa kumppanisi kanssa kävelylle ja katsot ulos ja huomaat, että ulkona paistaa aurinko. Pistätte päälle vaatteita melko vähän ja lähdette matkaan. Pian kuitenkin huomaatte, että ulkona ei olekaan kauhean lämmin. Toteat kumppanillesi: | Context |

| Q16 | ||

| ‘You are going out for a walk with your spouse. You look out and you notice that the Sun is shining. You dress lightly and go out. However, soon you notice that it is not very warm. You say to your spouse’: | ||

| Täällä___ on kylmä | Reaction | |

| ‘It is___ cold here’ | ||

| Average: 0 (=hAn strongly preferred) | ||

In both cases above, =hAn is unarguably more frequent than =se, which very well reflects the general tendency, with an average of 0.04 for impersonal constructions.

4.1.5 Summary of the questionnaire study results

The results of the questionnaire study show that =hAn is in general more common regardless of person, the reason being due to its higher overall frequency and the more grammaticalised nature of =hAn (as discussed in Section 3.1). In some cases, the two clitics are functionally rather close to each other, and it might be easier to choose the more frequent and natural clitic =hAn over =se in these cases. The overall result from the questionnaire is given in Table 2.

Appropriateness judgement averages for the uses of the clitics =hAn (≥0.00) and =se (≤2.00) with different subject persons

| First person | Second person | Third person | Impersonal | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.37 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 0.04 | 0.73 |

Some student participants further provide in their answers some qualitative information on subtle differences in the uses of both clitics. Furthermore, several students also give comments that in some cases, using the conjoint form =hAn=se would be possible or even more suitable for the specific given contexts. Below, we provide a summary of the participants’ comments, which will serve as qualitative evidence for further discussion in Section 5. As these comments provide valuable insights from language users, our summary here will focus only on a relevant question related to the interrelation with a subject person, with a primary emphasis on =se, the morphosyntactic behaviour and constraints of which have been significantly understudied.

Most comments go in line with our description in Section 2.2. First, the main distinction between the use of =hAn and =se is related to how evidence is acquired. While =hAn shows a recognitional use relying on the interlocutors’ shared experience and knowledge, =se is more often used when new evidence is exclusively or inclusively acquired in the discourse situation. Interaction-wise, the speaker uses =hAn when some reaction or feedback is expected from the hearer, while =se does not stimulate any interaction in the discourse.

Regarding specific comments on =se, few participants indicate that the use of =se does not fit well with the subject of a person in the plural. Morphology-wise, the subject case other than nominative seems to disfavour the use of =se, but some participants suggest that its partitive form sitä could be used instead for a subject person in locational cases, for instance. This corresponds to the description in the Finnish reference grammar (Hakulinen et al. 2004, §827) that the clause-second sitä is often used in impersonal constructions where the preceding clause-initial element is not a nominative subject. As for the subject person, several participants explicitly comment that =se suits better in contexts with second or third persons, the sphere of whom the speaker is orienting the hearer’s attention, while first person is appropriate in only a few contexts, such as in a contrasting function ‘someone else’ vs ‘me’. These several remarks may to a certain extent account for the degree of appropriateness in Table 2, as well as frequencies observed from the corpus (Section 4.2).

Supporting the status of =se as a discourse particle, numerous comments speak in favour of =se being grammaticalised towards a marker of discourse management, epistemicity, evidentiality and engagement. Namely, the clitic =se no longer purely serves the primary referential function of the demonstrative se, but can also be used to express the quality of information and acquisition of evidence presented to the hearer, as well as a wide range of evaluative functions related to affectedness and attitude, sarcasm and irony, impoliteness and rudeness, for instance.

4.2 Usage-based account on distribution among different subject persons in the use of =hAn and =se

As a second part of our study, the observations from crowdsourcing in Section 4.1 are tested against the actual language data retrieved from the Suomi24 Sentences Corpus 2001–2020 (Suomi24), using the Language Bank of Finland’s web interface, Korp, for searching. The corpus consists of 20 sub-corpora from each year’s version of the website Suomi24 from 2001 to 2020, including a total of 4,582,558,555 tokens and 391,965,356 sentences.

As mentioned in Section 4.1, the corpus is comparable to the contextual setting in the questionnaire part, as both involve situations in which a statement is given as a foregrounding context in which the audience reacts, as illustrated in Figure 2. Furthermore, Suomi24 is an open and anonymous platform, which often results in heated discussions. The data are thus biased towards certain genres, which may skew the results somewhat. However, despite these potential problems, we maintain that Suomi24 is a suitable corpus for the goals of the present article.

As for the search queries, the following filtering solutions are applied. The sample takes only contexts where first, second, and third person pronouns co-occur with =hAn and =se, or both in the respective sequence =hAn=se, and finite verbs agreeing in person and both numbers (singular and plural) with the pronouns. Note that the queries can capture formal variations of personal pronouns, e.g. minä, miä, mä, and mää for the first-person singular pronoun. This combination of morphemes gives a total of 28 search scenarios (the full list and CQP queries are shown in Appendix 1). The set of CQP queries employed in the data search aims at maximising recalls to achieve an overall picture of frequency and, therefore, may partially sacrifice the precision of the data received. For instance, a borderline case overlapping with a cleft construction and a fronted subject pronoun, such as hän=se on, joka … [3sg=se be.3sg rel] ‘it is him/her who […]’ (as described in the study by Hakulinen et al. 2004, §1383, §1388), may have been included in the recall to a small extent. In any case, the aim is more at giving rough numbers of occurrences for the sake of comparison and confirmation with the qualitative account in Section 4.1, considering also the note in Section 1 that =hAn and =se are both completely optional elements.

The results on the distribution of the clitics and their combination =hAn, =hAn=se, and =se across different subject persons are given in Table 3.

Co-occurrences of the clitics =hAn, =hAn=se, and =se with different subject persons

| =hAn | =hAn=se | =se | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First person | 92,296 | 90.50% | 2,606 | 2.56% | 7,077 | 6.94% | 101,979 |

| Second person | 87,915 | 79.94% | 6,202 | 5.63% | 15,855 | 14.42% | 109,972 |

| Third person | 105,038 | 87.25% | 1,524 | 1.27% | 13,824 | 11.48% | 120,386 |

| Total | 285,249 | 85.83% | 10,332 | 3.11% | 36,756 | 11.06% | 332,337 |

In general, the frequency of =hAn clearly outnumbers that of =se, which supports the implication about their degrees of grammaticalisation and naturalness (as discussed in Section 3.1). This stems from the idea that elements which can be used in more contexts have been grammaticalised to a larger extent than elements which can be used more restrictively in specific contexts. The results from the usage-based data show significant correlations with the results from the questionnaire data in that the use of =hAn is more frequent than =se overall, and in terms of person, =hAn co-occurs most often with the first person who usually holds the epistemic authority towards a given state of affairs. At the same time, =se occurs more frequently with the second person, which may be due to a difference in context settings, as the online social networking website often contains a discourse context where the statement about the first person in the opening turn is reacted to by repliers as the second person with expression confirming the shared knowledge (see the structure of Suomi24 discussion platform in Figure 2). Further discussion on the rationale behind the correlations with subject persons will be given in Section 6.

At this point, we can summarise the order of frequencies for the corpus data, as follows: =hAn, first person > third person > second person; and =se, second person > third person > first person. This result will be used as the basis for discussion in Section 5.

5 Discussion

The present study has discussed the uses of the Finnish clitics =hAn and =se as markers of different intersubjective and pragmatic uses and their relation to the category of person. The correlation between the clitics and subject persons has been investigated by two different methods: 1) qualitative through appropriateness judgement questionnaire and 2) quantitative through corpus. The former focuses on the functions of the clitics, while the latter accounts for usage-based frequencies (as shown in Section 4). Below we will discuss some general tendencies and the rationale behind them, focusing on three main issues: 1) nature of the data and methods, 2) the role of person in the intersubjective uses of the clitics =hAn and =se, and 3) other noteworthy observations from the data analysis.

5.1 Nature of the data and methods

The first two points of discussion concern the overall frequencies of use and the difference in contextual settings of the two methods employed in the current study. First, we should note that despite the very different nature and foci of the two methods employed, the correlations between the markers of engagement and subject persons show similar, yet not identical, tendencies. With all subject persons, =hAn is generally more common due to its significantly higher overall occurrence frequencies (as argued in Sections 3.1 and 4.1.5).

Second, the contexts have their effect observable in the use of =se, which is in general less common in the corpus-based study than in the questionnaire-based study. Again, this is probably not a coincidence, but these differences have good reasons. The most evident of these is found in the different nature and goals of the two studies focusing on functions and frequencies, respectively. For the questionnaire, we created scenarios in which either of the clitics, based on our own intuition, would be more normal, and for this, we also needed to include scenarios, where we could expect =se to be more common. This very naturally makes the occurrence of =se higher than in the normal language use observed in the corpus data which is more telling in this regard, and our findings lend further support to the claim that =hAn has been grammaticalised to a larger extent than =se (as proposed in Section 3.1). Furthermore, the fact that =se is not compatible with certain word classes may be responsible for the frequency differences here. It is naturally also possible that there are significantly fewer contexts where =se would be preferred in normal language use, but we leave this aspect for further studies in detail.

Another issue with the contextual settings is that =se is the most common with the third person in the questionnaire survey, while through the quantitative corpus-based method, =se occurs most often with the second person. As noted in Section 4.2, one of the reasons for the highest frequencies for co-occurrences of =se and the second person in the corpus may be found in the contextual structure of the online social networking platform in which many cases are such that someone states something, and someone else reacts to this. In other words, what is said first serves as a kind of concrete evidence, and the response is thus based on what was just said, and the nature of the evidence supports the use of =se as a reaction to the previous statement by the second person (Figure 2). Despite the frequency differences with regard to co-occurrences between markers of engagement and different subject persons observed in the two methods, the corpus serving as a primary representative data in the current study interestingly shows similar results with those of the corpus study of the Swedish modal particle pairs ju and väl by Bergqvist (2020, 486) discussed in Section 3.3.

As remarks on the data and methods, a more extensive cross-linguistic comparison, based on actual language use data as is done in the spirit of engagement research for Vietnamese (Adachi 2016), Swedish (Bergqvist 2020), and Finnish in the present study, can better shed light on distributional tendencies and an ultimate limit of engagement system in a language, and at a more general level improve the description and typologisation of engagement and linguistic intersubjectivity.

5.2 The role of person in the intersubjective uses of the clitics =hAn and =se

In contexts involving the first person, =hAn is more common and =se less common. There are at least three reasons for this (in addition to the general higher frequency of =hAn mentioned in Section 5.1). First, events where the speaker is basing their claim on actual concrete evidence may be rather few in number, which makes =se functionally less appropriate, as there is naturally less need for communicating something both the speaker and hearer can witness, i.e. uninformative statements (as defined in Sections 2.2 and 3.2). Second, the speaker is by default the epistemic authority (S+) with first-person statements, and this does not need to be stated explicitly, which makes it possible for the speaker to utilise engagement characteristics of =hAn to express the speaker-oriented epistemic asymmetry (as discussed in Section 5). Third, the lower frequency of =se with the first person may follow from the simple fact that person does not determine the use of the clitics to any large extent, but other epistemic-related factors discussed above are more relevant to this (see below).

As for the second person, despite the general higher tendency of =hAn, an explanation for the uses of both clitics is not as clear-cut as in the case of the first person. The main difference to the first person is that the involvement of the second person often entails the hearer authority (H+). However, =se, which favours epistemic symmetry between the interlocutors, more frequently occurs here than with the first person. This could be seen as somewhat unexpected, but there are also good reasons why =hAn is not as clearly the preferred choice as with the first person. First, =hAn is common in cases where the speaker expects the hearer to have epistemic authority, but the speaker, at the same time, also has a hunch about what they are talking about. For example, =hAn is common when the speaker tries to stimulate interaction with the hearer and expect some feedback, looking for a confirmation for what they believe to be the case, as is the case in (28). Second, it is more common that the speaker somehow reacts to what someone has stated earlier, and the previous utterance involving an interlocutor who will become the second person in the reaction turn can be viewed as a kind of concrete evidence for the one performing reaction, which would explain why =hAn does not dominate as clearly as with the first person (see the points on contextual settings made in Section 4.1).

In the questionnaire study, =se is somewhat more frequent with the third person than =hAn. The main difference between the first and second persons is that with the third-person involvement, neither the speaker nor the hearer is by default the epistemic authority, but this varies more based on who has better access to knowledge (see the comparison with non-person-oriented engagement of distal demonstratives in Section 3.3). This may be highly relevant to the more frequent occurrence of =se. First, as the interlocutors are not dealing with evidence that would inherently be more accessible to either the speaker or the hearer, the speaker tends to choose =se rather than the recognitional =hAn. Closely related to this, the interlocutors are more dependent on concrete evidence typically expressed by =se, because one cannot use their own general knowledge of the world as a basis for their claim. Second, as the epistemic authority does not inherently belong to either of the speech act participants, the speaker has more freedom to choose which of the two clitics they will use, and they may opt more often for =se for stimulating interaction, establishing joint attention with the hearer in the described situation. It is interesting to note also that the overall numbers of the clitics are highest for the third persons (as shown in Table 3 in Section 4.2), although the common nouns were not included in the quantitative study. The differences are statistically not very significant, which again affirms that person does not determine the general use of the clitics in any stringent way. However, we may perhaps note also here that with the third-person epistemic authority is not set automatically by the asymmetry of knowledge distribution between speech act participants. Consequently, we may claim that it is slightly more relevant to mark the access to knowledge, epistemic authority, and intersubjectivity with the third person, even though the differences are not very significant.

Impersonal constructions have been surveyed only through questionnaire, but we consider it worth mentioning our findings here. Namely, the very clear dominance of =hAn with impersonal constructions can be viewed as rather unexpected if we consider the dominance of =se with third person. In both cases, the third person and impersonal, epistemic authority does not inherently belong to either of the speech act participants. However, the occurrence of =hAn is clearly more common in the questionnaire than in the third person. We may speculate that with impersonal constructions, especially with those expressions describing weather conditions, humans cannot have any control over what happens, which completely excludes (personal) epistemic authority from the speech act participants and thus makes =hAn more common. In other words, despite not having the knowledge, the interlocutors are rightful to have their own opinions about what has happened, and the best they can do is to compare opinions with each other, yielding a symmetric (S−H−) situation in the evidentiality type of context where =hAn is clearly suitable (as stated in Section 3.2). In any case, it might be that since epistemic authority does not inherently belong to any of the speech act participants, other factors possibly play a more important role and instead of person we would need to look for complementing explanations elsewhere. For example, the use of certain modal verbs (e.g. pitää ‘have to’ as in (25)), the use of the imperative form, affective lexical elements (e.g. takahikiä), temporal particles, the use of exclamation mark (all as present in (26)), the use of discourse particles (nyt, sit(ten) and kyllä, as in (27)) may affect the choice of the appropriate particle. However, in this article, the focus was solely on the effects of the subject person.