Abstract

We propose and validate a method for designing a broadband variable beamsplitter using a metamaterial with subwavelength thickness. Through theoretical analysis and numerical simulations, we demonstrate that the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio of a single-layer resonant metamaterial at its resonance frequency can be controlled by varying the spatial arrangement of the constituent meta-atoms, without altering their individual structures. Building on this theory, we further conjecture a method for achieving a frequency-independent reflectance-to-transmittance ratio across a broad spectral range. Numerical results confirm that a metamaterial with subwavelength thickness can be engineered to function as a broadband variable beamsplitter using the proposed approach. These findings contribute to the advancement of techniques for splitting and combining electromagnetic waves in compact systems.

1 Introduction

There has been considerable interest in controlling electromagnetic waves using metasurfaces, which serve as the two-dimensional counterparts of metamaterials. Researchers have developed compact optical components for a wide range of applications, including wavefront control [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], dynamic manipulation of wave propagation [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], and efficient generation of nonlinear phenomena [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

While metasurfaces are essential for miniaturization of optical systems, it is important to note that not all functionalities can be realized using one single-layer planar metasurface, which supports only electric dipole responses. For instance, arbitrary complex reflectance or transmittance cannot generally be achieved with such structures [2], [32], [33]. To enable arbitrary control of complex reflectance, a ground plane must be added [34], [35], [36], whereas arbitrary control of complex transmittance requires the design of a Huygens metasurface [2], [3], [5], [8], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. Huygens metasurfaces typically consist of thick and/or multilayer structures and exhibit not only electric dipole responses but also magnetic dipole and high-order multipole responses. Another approach to overcoming the limitation on the properties of single-layer planar metasurfaces involves the steric arrangement of meta-atoms [47], [48].

As outlined above, arbitrary complex reflectance or transmittance can be achieved by stacking multiple metasurfaces, increasing their thickness, and/or sterically arranging the constituent meta-atoms. While previous studies have extensively explored the control of either complex reflectance or complex transmittance, the control of the ratio between reflectance and transmittance has received little attention. Beamsplitters are essential components in various applications, including interferometry, spectroscopy, and imaging systems. Therefore, developing techniques to control the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio using metasurfaces would be highly beneficial for advancing electromagnetic wave technologies.

To address this, we focus on the distinction between single-layer planar metasurfaces and Brewster metafilms developed in our previous studies [47], [49], [50]. Brewster metafilms are single-layer metamaterials composed of meta-atoms arranged such that the oscillation direction of the induced electric dipoles aligns with the propagation direction of the reflected wave. For planar metasurfaces, the incident wave is completely reflected at the resonance frequency [51]. In contrast, for Brewster metafilms, the incident wave is fully transmitted regardless of frequency. Although these two types of metamaterials exhibit markedly different reflectance and transmittance characteristics, the only difference in their microscopic responses lies in the oscillation direction of the induced electric dipoles.

This observation suggests that the optical properties of single-layer metamaterials can be tuned continuously from perfect reflection to perfect transmission solely by modifying the arrangement of the constituent meta-atoms. In this study, we theoretically and numerically demonstrate that the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio at the resonance frequency in single-layer resonant metamaterials can be arbitrarily controlled by adjusting the spatial configuration of meta-atoms. Furthermore, we propose a method for achieving a frequency-independent reflectance-to-transmittance ratio over a broad frequency range and numerically verify that a broadband variable beamsplitter can be designed using this approach.

2 Theory

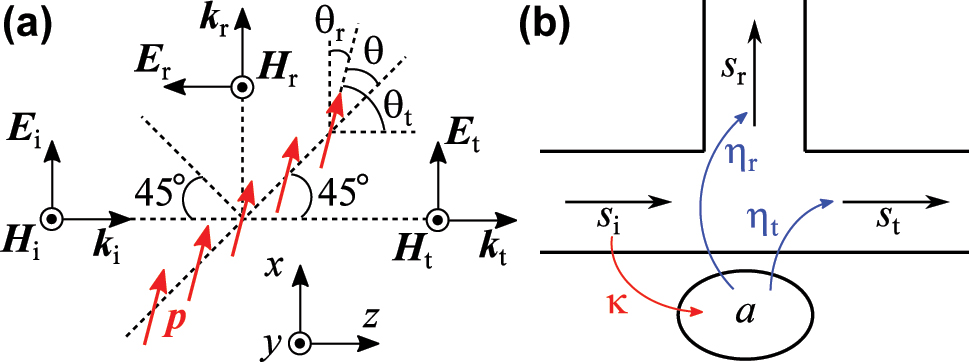

To construct a theoretical framework for controlling the ratio of the reflectance to the transmittance, we begin by analyzing the radiation from a single-layer metamaterial illuminated by a plane electromagnetic wave, as illustrated in Figure 1(a). The constituent meta-atoms are arranged periodically along the 45° direction relative to the z-axis and along the y-axis. Each meta-atom supports only an electric dipole, with its oscillation direction oriented at 45° + θ with respect to the z-axis. An x-polarized plane electromagnetic wave is incident from the −z direction at an angle of 45°. In this configuration, the metamaterial can radiate electromagnetic waves along both the x- and z-directions.

Theoretical model of the proposed variable beamsplitter. (a) Relationship between the oscillation direction of the electric dipole p induced in a single-layer metamaterial and the incident, reflected, and transmitted electromagnetic fields. (b) Schematic of a resonator system coupled to three propagation modes. The subscripts of “i,” “r,” and “t” indicate the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves, respectively.

For simplicity, we model the induced electric dipole infinitesimal. The radiation pattern of such a dipole is proportional to sin ϕ, where ϕ is the angle between the dipole’s oscillation direction and the propagation direction of the radiated wave [52]. Therefore, the ratio of the amplitude of the radiation in the x-direction to that in the z-direction is given by [53]:

where θ r and θ t are the angles between the oscillation direction of the induced electric dipoles and the propagation directions of the reflected and transmitted waves, respectively. When θ = 0°, k = 1, indicating equal amplitudes of radiation in the reflected and transmitted directions. This corresponds to single-layer planar metasurfaces, where electric dipoles oscillate within the metasurface plane. As θ increases, k decreases. At θ = 45°, k = 0, meaning no radiation occurs in the reflected direction – a characteristic of Brewster metafilms. Thus, by varying θ from 0° to 45°, k can be tuned continuously from 1 to 0.

Next, we analyze the reflectance and the transmittance of a single-layer resonant metamaterial using the model shown in Figure 1(b). In this model, a resonance mode is excited by an incident wave and radiates into both the reflected and transmitted directions. It is assumed that diffraction does not occur. According to temporal coupled-mode theory [54], [55], [56], the system dynamics are governed by:

where s i, s r, and s t denote the amplitudes corresponding, respectively, to the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves; a denotes the amplitude of the resonance mode; κ the coupling between the incident wave and the resonance mode; ω 0 the resonance angular frequency; η r and η t denote the couplings to the reflected and transmitted waves; γ r and γ nr the radiative and nonradiative losses of the resonance mode; and τ denotes time. From the previous definition, the ratio k is expressed as:

Before calculating reflectance and transmittance, we derive the relationship between γ

r and the coupling coefficients η

{r,t}. Assuming no incident wave (s

i = 0) and no nonradiative loss (γ

nr = 0), Eq. (2) yields a = A exp[(−iω

0 − γ

r)τ], where A is a constant. Since all the energy is radiated into the reflected and transmitted waves, energy conservation requires

Now, for a monochromatic incident wave with angular frequency of ω, Eq. (2) simplifies to a = {κ/[−i(ω − ω 0) + γ r + γ nr]}s i. Substituting into Eqs. (3) and (4), the complex reflectance r and the complex transmittance t are:

Assuming γ nr = 0, energy conservation requires |r|2 + |t|2 = 1, which leads to:

To satisfy this equation for all ω, Im(η t κ) = 0 must hold, implying η t κ is real. Thus, Eq. (9) reduces to:

where Eq. (6) is used. Substituting Eqs. (5) and (10) into Eq. (6), we obtain:

Finally, using Eqs. (5), (10), and (11), the reflectance and transmittance become:

Based on Eqs. (12) and (13), we develop a method for controlling the ratio of the reflectance to the transmittance at the resonance frequency. At resonance ω = ω 0, the reflectance and the transmittance simplify to:

To examine the dependence on k, we set γ nr = 0. When k = 1, r(ω 0) = −1 and t(ω 0) = 0, indicating total reflection. As k decreases, |r(ω 0)| decreases and |t(ω 0)| increases. At k = 0, r(ω 0) = 0 and t(ω 0) = −1 indicating total transmission. From Eq. (1), k varies from 1 to 0 as θ varies from 0° to 45°. Therefore, the ratio |r(ω 0)|/|t(ω 0)| can be arbitrarily controlled by tuning θ within this range.

Building on the above theory for controlling the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio at the resonance frequency, we propose a method for achieving a frequency-independent ratio across a broad frequency range. From the theoretical results, we infer that if a single-layer resonant metamaterial exhibits perfect reflection (perfect transmission) over a wide frequency band when θ = 0° (θ = 45°), then the reflectance within this band may be governed primarily by θ and not by frequency. Assuming the nonradiative loss of the metamaterial is negligible, the transmittance should likewise remain frequency-independent due to energy conservation. This suggests that broadband beamsplitters with tunable splitting ratios controlled by θ are feasible using a single-layer metamaterial that supports perfect reflection for θ = 0° and perfect transmission for θ = 45° over a broad spectral range.

3 Numerical simulation

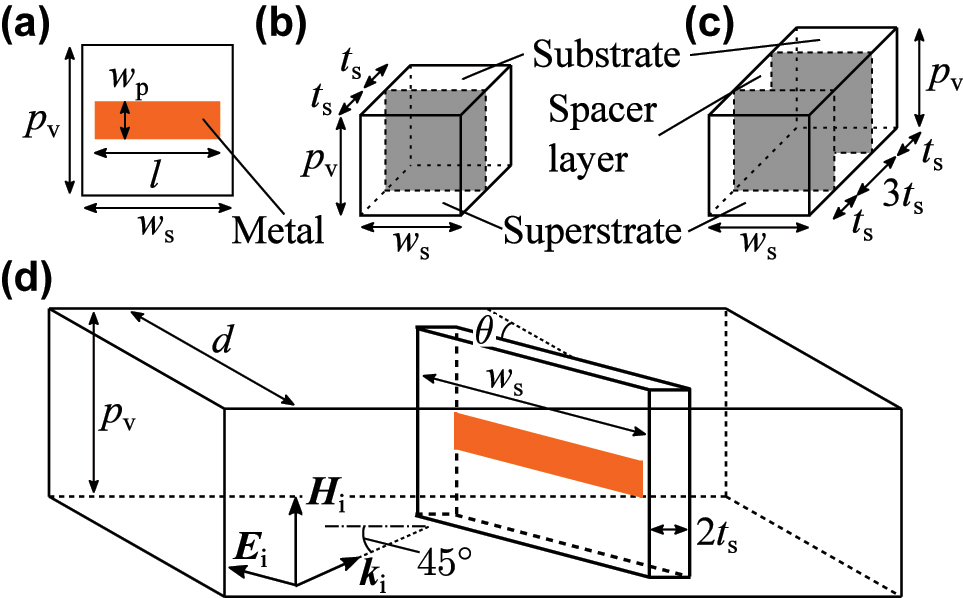

To verify the theoretical framework for controlling the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio at the resonance frequency, we numerically analyzed the dependence of reflection and transmission spectra on θ for a single-layer metamaterial. Any resonant structure exhibiting only an electric dipole response can serve as the constituent meta-atom; in this study, we employed a commonly used dipole resonator, as shown in Figure 2(a). When a horizontally polarized electromagnetic wave is incident on this structure, a horizontally oscillating electric dipole is induced. The dipole resonator has a relatively high radiative loss, which is advantageous in decreasing γ nr/γ r. The dipole resonator was assumed to be fabricated on a dielectric substrate and covered with the same dielectric material to realistically lower the resonance frequency. This structure can be fabricated using standard printed circuit board technology in the microwave region.

Geometry of the metamaterials and the simulation system. (a) Schematic of the structure of the dipole resonator. (b) A constituent element of the single-layer metamaterial. (c) A constituent element of the two-layer metamaterial. The dipole resonator is in the gray planes. (d) Simulation system for analyzing the reflectance and the transmittance of the metamaterials. This figure relates to the analysis of a single-layer metamaterial. The geometrical parameters used in the numerical simulation are as follows: w p = 0.5 mm, l = 14.0 mm, w s = 15.0 mm, t s = 0.8 mm, p v = 4.0 mm, and d = 16.0 mm. The relative permittivity of the substrate, superstrate, and spacer layer is taken to be 4.5(1 + i0.03).

We performed numerical simulations of the reflection and transmission spectra for the single-layer metamaterial composed of the structure shown in Figure 2(b), using COMSOL Multiphysics. The simulation setup is illustrated in Figure 2(d). The dipole resonator was modeled as a perfect electric conductor with negligible thickness. Both the substrate and superstrate were assumed to be FR-4, with a relative permittivity of 4.5(1 + i0.03). The dielectric loss of FR-4 is relatively high compared with that of the other low-loss printed circuit board substrates. For example, the dielectric loss tangent of polyphenylene ether is 0.005 and that of Rogers RT/duroid 5880 is 0.0009. This implies that we examine the influence of material loss on the reflection and transmission spectra by assuming that the substrate and superstrate have a relatively high dielectric loss. Periodic boundary conditions were applied along the horizontal boundaries to simulate periodic arrangement of the meta-atoms, as depicted in Figure 1(a). Perfectly matched layer boundary conditions were applied perpendicular to the horizontal direction. A p-polarized electromagnetic wave was incident at the incident angle of 45°, and reflection and transmission spectra were calculated for various values of θ.

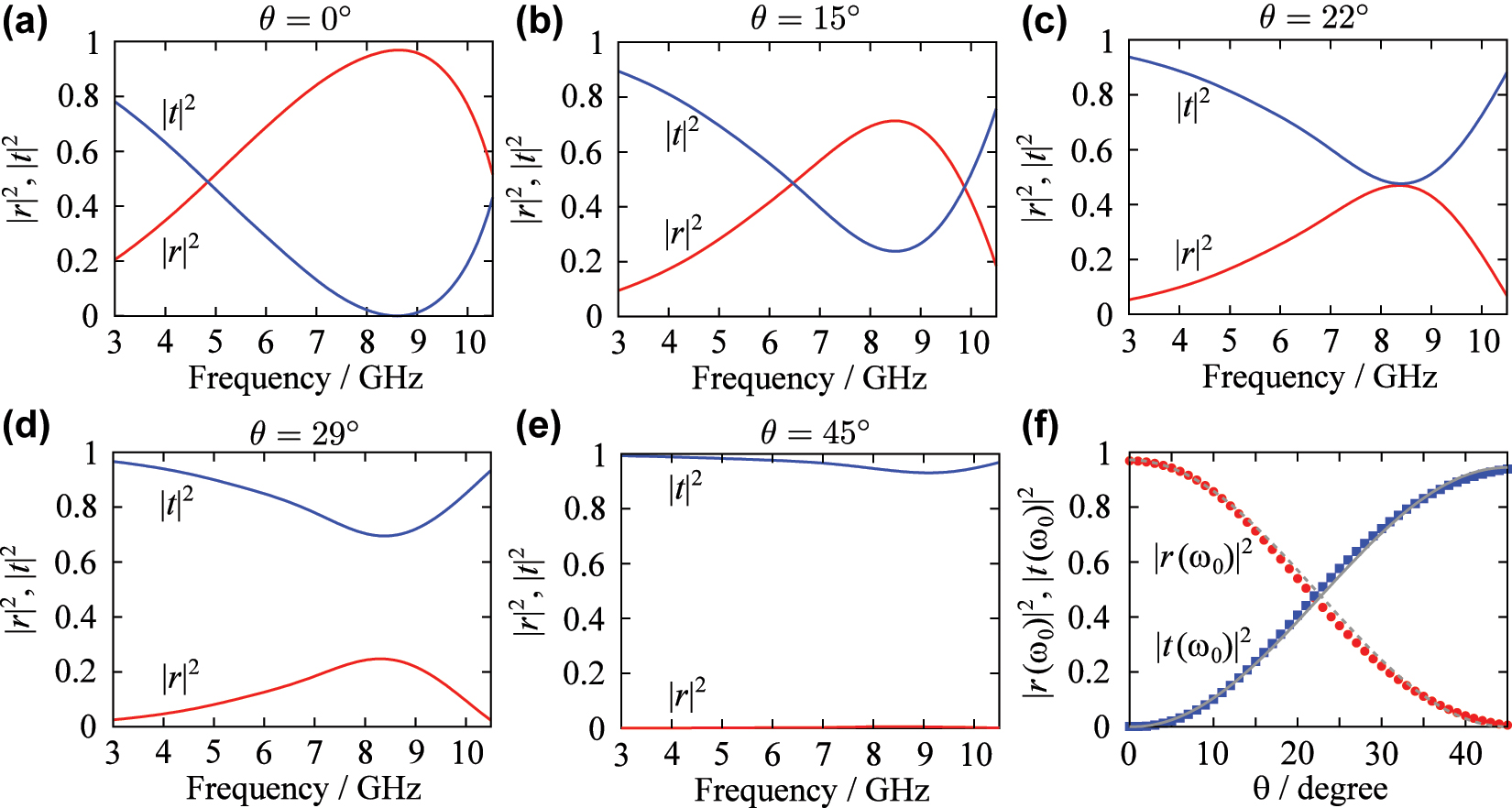

Figure 3(a)–(e) shows the numerically computed reflection and transmission spectra for θ = 0°, 15°, 22°, 29°, and 45°. For θ = 0°, the reflectance |r|2 nears unity and the transmittance |t|2 nears zero at the resonance frequency 8.64 GHz (defined here as the frequency at which the magnitude of the reflectance is maximized). As θ increases, the magnitude of the reflectance at the resonance frequency decreases while the transmittance increases. For θ = 45°, |r|2 approaches zero and |t|2 approaches unity, nearly independent of frequency. Figure 3(f) shows the dependence of |r|2 and |t|2 on θ at the resonance frequency, along with theoretical fits based on Eqs. (14) and (15). The numerical results show excellent agreements with the theoretical predictions. The best-fit value of the parameter γ nr/γ r is 1.42 × 10−2. It is confirmed from these results that the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio at resonance can be controlled by varying θ in a single-layer metamaterial and that γ nr/γ r can be decreased by using the dipole resonator as the constituent element even for the case where FR-4 is used as the substrate and superstrate.

Numerically calculated reflection and transmission spectra of the single-layer metamaterial for (a) θ = 0°, (b) 15°, (c) 22°, (d) 29°, and (e) 45°. (f) The θ dependences of reflectance and transmittance at the resonance frequency. The gray solid and dashed curves are theoretical fits. The best fit of the numerically calculated data to Eqs. (14) and (15) is for γ nr/γ r = 1.42 × 10−2.

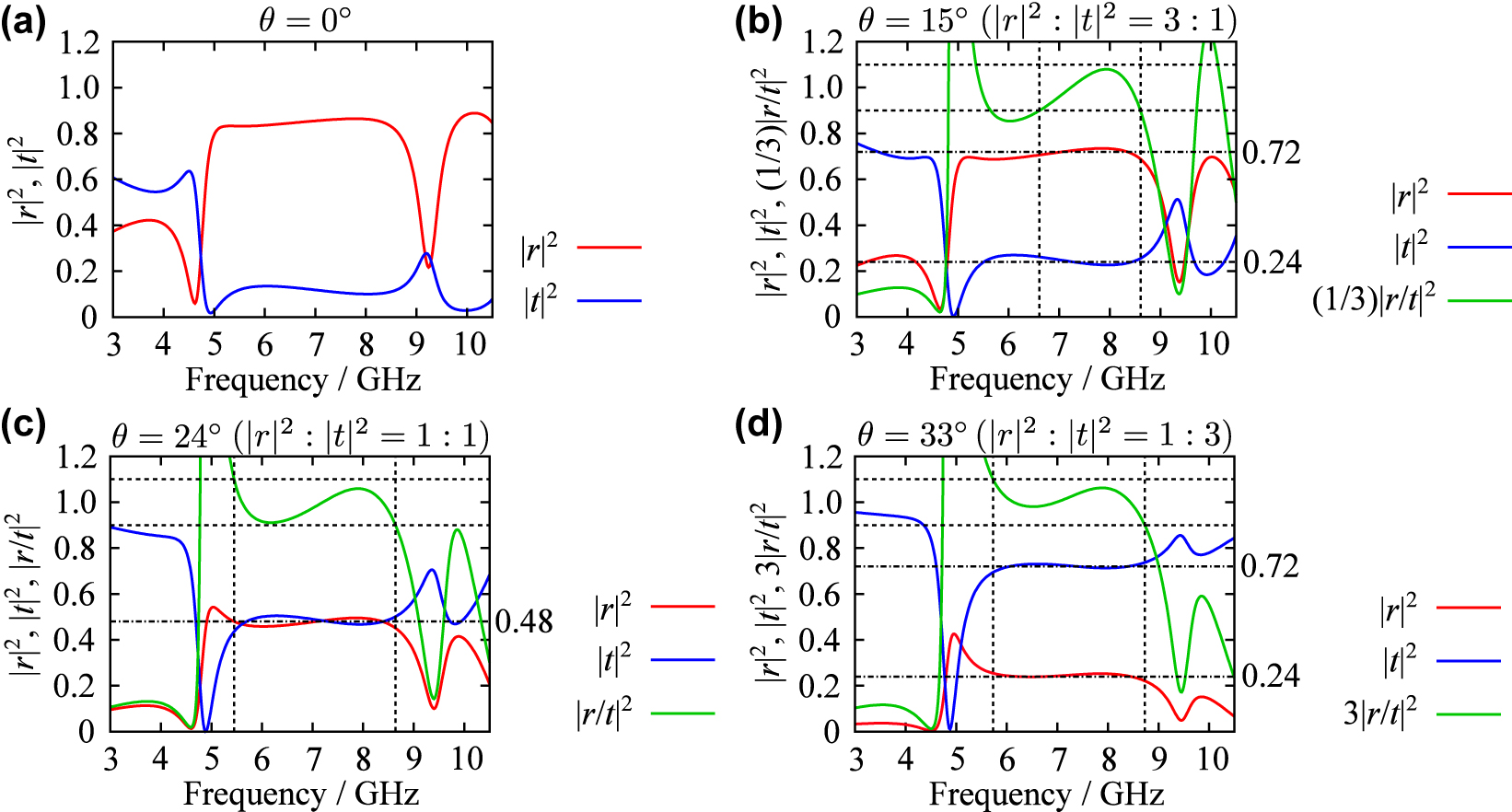

We next verify the conjectured method for achieving a frequency-independent reflectance-to-transmittance ratio across a broad frequency range. As discussed earlier, a broadband beamsplitter with a tunable splitting ratio may be realized using a single-layer metamaterial that exhibits perfect broadband reflection for θ = 0° and perfect broadband transmission for θ = 45°. To test this, we designed the structure shown in Figure 2(c) as a constituent element. The dipole resonator acts as a mirror at around the resonance frequency for θ = 0° as shown in Figure 3(a). Therefore, it is easy to realize broadband high reflection for θ = 0° using the structure shown in Figure 2(c) as long as this two-layer structure is designed so that the Fabry–Perot resonance does not occur [57]. Although the structure is visibly two-layer, we hypothesize that it behaves effectively as a single-layer structure, provided its thickness remains much smaller than the wavelength of the incident electromagnetic wave.

We numerically analyzed the reflection and transmission spectra of the metamaterial composed of this structure for various values of θ. Figure 4(a)–(d) shows the computed spectra for θ = 0°, 15°, 24°, and 33°. For θ = 0°, the reflectance |r|2 exceeds 0.8 across the frequency range from 5.01 GHz to 8.64 GHz. Although perfect reflection is not achieved, the reflectance remains high throughout this range. As θ increases, |r| decreases and |t| increases, consistent with the behavior observed in the single-layer metamaterial. The reflectance-to-transmittance ratios for θ = 15°, 24°, and 33° are approximately 3 ± 0.3 (6.61 GHz–8.61 GHz), 1 ± 0.1 (5.45 GHz–8.64 GHz), and 1/3 ± 1/30 (5.73 GHz–8.73 GHz), respectively. In these frequency ranges, the sum |r|2 + |t|2 is approximately 0.96, indicating low absorbance

Numerically calculated reflection and transmission spectra of the two-layer metamaterial for (a) θ = 0°, (b) 15°, (c) 24°, and (d) 33°. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the region where the deviation of the ratio of |r|2 to |t|2 from the intended value (shown above each graph) is less than 10 %, and the vertical dashed lines indicate the corresponding frequency range.

4 Conclusions

We have proposed and numerically validated using COMSOL Multiphysics that the reflectance-to-transmittance ratio of metamaterials with subwavelength thickness can be controlled by varying the spatial arrangement of the constituent elements, without altering their individual structures. The developed theory demonstrates that this ratio at the resonance frequency can be arbitrarily tuned by adjusting the parameter θ in single-layer metamaterials. Building on this result, we conjectured a method for realizing beamsplitters with a frequency-independent splitting ratio governed by θ, and numerically confirmed that a broadband variable beamsplitter can be realized using a two-layer metamaterial with subwavelength thickness.

We used a metamaterial composed of the two-layer structure to realize a broadband variable beamsplitter because it was easy to design a metamaterial that exhibits broadband high reflection for θ = 0° based on the two-layer structure. However, according to the proposed theory, the variable beamsplitter can be realized with the use of single-layer structures. For future work, it is essential to design a broadband variable beamsplitter composed of a single-layer structure that exhibits broadband high reflection for θ = 0°. In addition, it is necessary to develop a method for fabricating single-layer metamaterials with variably controllable θ. The value of θ can only be varied using mechanical methods; thus, the proposed variable beamsplitter could be fabricated in the frequency region up to, at most, terahertz frequencies.

Although this study was limited to configurations where diffraction does not occur, the concept may be extended to realize multiport variable beamsplitters by incorporating diffraction effects. The radiation from a metamaterial depends on the relationship between the radiation pattern and the phase distribution of the induced dipoles in the meta-atoms, which holds regardless of whether diffraction occurs or not. This implies that the port number of the variable beamsplitter could be increased by increasing the period of the metamaterial so that diffraction occurs. These findings contribute to the advancement of electromagnetic wave applications in areas such as information processing, precision measurement, and imaging.

Funding source: Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: JPMJCR2101

Funding source: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: JP21K04192

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Satoshi Tomita for helpful discussion.

-

Research funding: This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) under Grant JP21K04192 and by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (CREST JPMJCR2101).

-

Author contributions: YT conceived the idea and constructed the theory. YT and YS designed the metamaterial structures, numerically analyzed the properties of metamaterials, and carried out the data analysis. YT wrote the paper with input from YS. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] N. Yu, et al.., “Light propagation with phase discontinuities: Generalized laws of reflection and refraction,” Science, vol. 334, no. 6054, pp. 333–337, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1210713.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] F. Monticone, N. M. Estakhri, and A. Alù, “Full control of nanoscale optical transmission with a composite metascreen,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 110, no. 20, p. 203903, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.110.203903.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] C. Pfeiffer and A. Grbic, “Metamaterial Huygens’ surfaces: Tailoring wave fronts with reflectionless sheets,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 110, no. 19, p. 197401, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.110.197401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] L.-H. Gao et al.., “Broadband diffusion of terahertz waves by multi-bit coding metasurfaces,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 4, p. e324, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2015.97.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] K. E. Chong et al.., “Polarization-independent silicon metadevices for efficient optical wavefront control,” Nano Lett., vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 5369–5374, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01752.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] R. C. Devlin, A. Ambrosio, N. A. Rubin, J. P. B. Mueller, and F. Capasso, “Arbitrary spin-to–orbital angular momentum conversion of light,” Science, vol. 358, no. 6365, pp. 896–901, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao5392.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] W. T. Chen, A. Y. Zhu, J. Sisler, Z. Bharwani, and F. Capasso, “A broadband achromatic polarization-insensitive metalens consisting of anisotropic nanostructures,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, p. 355, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08305-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] A. A. Fathnan, M. Liu, and D. A. Powell, “Achromatic Huygens’ metalenses with deeply subwavelength thickness,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 8, no. 22, p. 2000754, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202000754.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] A. Zaidi, et al.., “Metasurface-enabled single-shot and complete Mueller matrix imaging,” Nat. Photon., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 704–712, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01426-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] L. Hou et al.., “High-efficiency broadband achromatic metalens in the visible,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 126, no. 10, p. 101704, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0240728.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] H.-T. Chen, W. J. Padilla, J. M. O. Zide, A. C. Gossard, A. J. Taylor, and R. D. Averitt, “Active terahertz metamaterial devices,” Nature, vol. 444, no. 7119, pp. 597–600, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05343.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] H.-T. Chen et al.., “Experimental demonstration of frequency-agile terahertz metamaterials,” Nat. Photon., vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 295–298, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2008.52.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] M. J. Dicken et al.., “Frequency tunable near-infrared metamaterials based on VO2 phase transition,” Opt. Express, vol. 17, no. 20, pp. 18 330–18 339, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.018330.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] C. Kurter et al.., “Classical analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency with a metal-superconductor hybrid metamaterial,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 107, no. 4, p. 043901, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.107.043901.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] N. Kanda, K. Konishi, and M. Kuwata-Gonokami, “All-photoinduced terahertz optical activity,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 11, pp. 3274–3277, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.003274.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] C. Huang, B. Sun, W. Pan, J. Cui, X. Wu, and X. Luo, “Dynamical beam manipulation based on 2-bit digitally-controlled coding metasurface,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, p. 42302, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42302.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] L. Li et al.., “Electromagnetic reprogrammable coding-metasurface holograms,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 197, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00164-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] W. X. Lim et al.., “Ultrafast all-optical switching of germanium-based flexible metaphotonic devices,” Adv. Mater., vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1705331–1–7, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705331.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] N. W. Almond et al.., “External cavity terahertz quantum cascade laser with a metamaterial/graphene optoelectronic mirror,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 117, no. 4, p. 041105, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0014251.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Y. Tamayama and K. Kanari, “Storage and release of electromagnetic waves using a Fabry-Perot resonator that includes an optically tunable metamirror,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 102, no. 3, p. 035162, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.102.035162.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] M. Y. Shalaginov et al.., “Reconfigurable all-dielectric metalens with diffraction-limited performance,” Nat. Commun., vol. 12, p. 1225, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21440-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] M. W. Klein, C. Enkrich, M. Wegener, and S. Linden, “Second-harmonic generation from magnetic metamaterials,” Science, vol. 313, no. 502, pp. 502–504, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1129198.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] M. Celebrano et al.., “Mode matching in multiresonant plasmonic nanoantennas for enhanced second harmonic generation,” Nat. Nano, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 412–417, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.69.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Y. Yang et al.., “Nonlinear Fano-resonant dielectric metasurfaces,” Nano Lett., vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 7388–7393, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02802.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Y. Wen and J. Zhou, “Artificial nonlinearity generated from electromagnetic coupling metamolecule,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 118, no. 16, p. 167401, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.118.167401.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Y. Tamayama and T. Yoshimura, “Frequency mixing at an electromagnetically induced transparency like metasurface loaded with gas as a nonlinear element,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 113, no. 6, p. 061901, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5045807.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] N. Bernhardt et al.., “Quasi-BIC resonant enhancement of second-harmonic generation in WS2 monolayers,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 5309–5314, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01603.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] A. P. Anthur et al.., “Continuous wave second harmonic generation enabled by quasi-bound-states in the continuum on gallium phosphide metasurfaces,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 8745–8751, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03601.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] G. Zograf et al.., “High-harmonic generation from resonant dielectric metasurfaces empowered by bound states in the continuum,” ACS Photonics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 567–574, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.1c01511.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] S. Xiao, M. Qin, J. Duan, F. Wu, and T. Liu, “Polarization-controlled dynamically switchable high-harmonic generation from all-dielectric metasurfaces governed by dual bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 105, no. 19, p. 195440, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.105.195440.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Y. Yi et al.., “Efficient chiral high harmonic generation in quasi-BIC silicon metasurface,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 126, no. 10, p. 101703, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0256542.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] D. Pozar, “Scattered and absorbed powers in receiving antennas,” IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag., vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 144–145, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1109/map.2004.1296172.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] S. Thongrattanasiri, F. H. L. Koppens, and F. J. García de Abajo, “Complete optical absorption in periodically patterned graphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, no. 4, p. 047401, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.108.047401.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] N. I. Landy, S. Sajuyigbe, J. J. Mock, D. R. Smith, and W. J. Padilla, “Perfect metamaterial absorber,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 100, no. 20, p. 207402, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.100.207402.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] X. Liu, T. Tyler, T. Starr, A. F. Starr, N. M. Jokerst, and W. J. Padilla, “Taming the blackbody with infrared metamaterials as selective thermal emitters,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 107, no. 4, p. 045901, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.107.045901.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] M. Kim, A. M. H. Wong, and G. V. Eleftheriades, “Optical Huygens’ metasurfaces with independent control of the magnitude and phase of the local reflection coefficients,” Phys. Rev. X, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 041042, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.4.041042.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] M. Decker et al.., “High-efficiency dielectric Huygens’ surfaces,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 813–820, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201400584.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] V. S. Asadchy, I. A. Faniayeu, Y. Ra’di, S. A. Khakhomov, I. V. Semchenko, and S. A. Tretyakov, “Broadband reflectionless metasheets: Frequency-selective transmission and perfect absorption,” Phys. Rev. X, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 031005, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.5.031005.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] A. Balmakou, M. Podalov, S. Khakhomov, D. Stavenga, and I. Semchenko, “Ground-plane-less bidirectional terahertz absorber based on omega resonators,” Opt. Lett., vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 2084–2087, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.40.002084.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] S. Kruk, B. Hopkins, I. I. Kravchenko, A. Miroshnichenko, D. N. Neshev, and Y. S. Kivshar, “Invited article: Broadband highly efficient dielectric metadevices for polarization control,” APL Photon., vol. 1, no. 3, p. 030801, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4949007.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] F. S. Cuesta, I. A. Faniayeu, V. S. Asadchy, and S. A. Tretyakov, “Planar broadband Huygens’ metasurfaces for wave manipulations,” IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag., vol. 66, no. 12, pp. 7117–7127, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2018.2869256.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] M. Londoño, A. Sayanskiy, J. L. Araque-Quijano, S. B. Glybovski, and J. D. Baena, “Broadband Huygens’ metasurface based on hybrid resonances,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 10, no. 3, p. 034026, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.10.034026.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] T. Feng, A. A. Potapov, Z. Liang, and Y. Xu, “Huygens metasurfaces based on congener dipole excitations,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 13, no. 2, p. 021002, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.13.021002.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] X. You et al.., “Broadband terahertz transmissive quarter-wave metasurface,” APL Photon., vol. 5, no. 9, p. 096108, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0017830.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] J. P. del Risco, et al.., “Optimal angular stability of reflectionless metasurface absorbers,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 103, no. 11, p. 115426, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.103.115426.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] D. Wang, S. Sun, Z. Feng, and W. Tan, “Complete terahertz polarization control with broadened bandwidth via dielectric metasurfaces,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 157, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-021-03614-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Y. Tamayama, “Design and analysis of frequency-independent reflectionless single-layer metafilms,” Opt. Lett., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 1102–1105, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.41.001102.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] T. Li, Y. Chen, Y. Wang, T. Zentgraf, and L. Huang, “Three-dimensional dipole momentum analog based on L-shape metasurface,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 122, no. 14, p. 141702, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0142389.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Y. Tamayama and H. Yamamoto, “Broadband control of group delay using the Brewster effect in metafilms,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 18, no. 1, p. 014029, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.18.014029.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Y. Tamayama and T. Hoshino, “Observation of zero-transmission dip in a single-layer electric metamaterial with finite non-radiative loss,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 125, no. 4, p. 041701, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0207068.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] S.-C. Jiang et al.., “Tuning the polarization state of light via time retardation with a microstructured surface,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 88, no. 16, p. 161104, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.161104.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] R. C. Johnson, Ed.in Antenna Engineering Handbook, 3rd ed., New York, McGrow-Hill, 1993.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Y. Tamayama and Y. Shibata, “Tunable beamsplitter based on continuous transition between a planar metasurface and a Brewster metafilm,” in Proceedings of 15th International Conference on Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals and Plasmonics (META2025), 2025, pp. 1070–1071.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] W. Suh, Z. Wang, and S. Fan, “Temporal coupled-mode theory and the presence of non-orthogonal modes in lossless multimode cavities,” IEEE J. Quantum Electron., vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 1511–1518, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1109/jqe.2004.834773.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Z. Ruan and S. Fan, “Temporal coupled-mode theory for Fano resonance in light scattering by a single obstacle,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 114, no. 16, pp. 7324–7329, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9089722.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] T. Christopoulos, O. Tsilipakos, and E. E. Kriezis, “Temporal coupled-mode theory in nonlinear resonant photonics: From basic principles to contemporary systems with 2D materials, dispersion, loss, and gain,” J. Appl. Phys., vol. 136, no. 1, p. 011101, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0190631.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] G. Alagappan, F. J. García-Vidal, and C. E. Png, “Fabry-Perot resonances in bilayer metasurfaces,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 133, no. 22, p. 226901, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.133.226901.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry