Abstract

Modern technological evolution witnesses a fast-paced progress in the design, science, and technology of light-driven micro/nanomachines in the recent past. These micromachines have found enormous applications as micro/nanoscale manipulators, micromachined space exploration components, nano-sized cell positioning and control, and micro/nanorobots for drug delivery to name a few. This is not only due to their smaller size but also due to an ever-demanding necessity of micro/nanoscale functionalities with touch-free optimum control incorporating features such as propulsion, self-powered and controlled activation, energy efficiency, intelligence, navigation, and tracking. It also motivates one for biomimicking the functionalities of several living organisms to mold the ideas into micro/nanorobots to understand their properties and the underlying physics. Incorporating the magical functionalities enabled by nano/micro photonics answer many a challenge while they also open a wide range of possibilities ahead. Here, we present light-driven micro/nanorobots (µn-Bots) whose robotic features and functionalities are envisaged to have potential applications in medicine, industry, rescue, and strategic deterrence, pertaining to all walks of life and spectrums. After giving a comparative as well as the state of art outline on advances on the diverse technological innovations of µn-Bots in general, we comprehensively go through the light-driven micro/nanorobot designs and explore their functionalities, materials, and micro/nanofabrication techniques concerning their recent advances and multifaceted applications. On the other hand, we also give an analysis on the performance matrix of the reported light-driven micro/nanorobots explicitly studied in the recent past and give an outlook on the future roadmap and trends.

1 Introduction

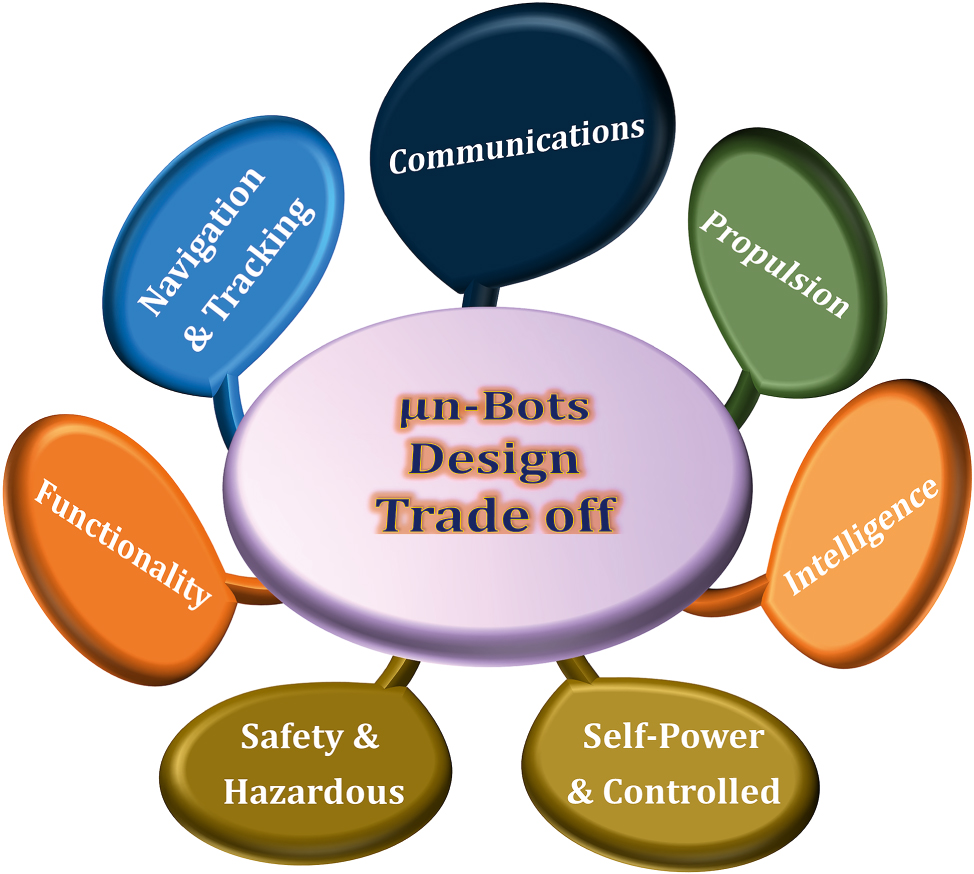

Miniaturization and automation are ever evolving technological innovation in all fields of engineering and science. So, it is true also in the field of robotic control and structural modules because of fast paced progress in micro/nanofabrication and enabling robotic technologies. Diverse types of micro/nanobots (µn-Bots) have been reported in the recent past for their distinct propulsion and ability to perform various functions in response to an external stimulus for carrying out the repetitive or hazardous tasks of our daily lives. Significant efforts in the development of μn-Bots have been made with diverse materials, control methods, and manufacturing techniques in order to evolve and optimize appropriate micro/nanoscale functionalities by incorporating features such as propulsion, self-powered and controlled activation, energy efficiency, intelligence, navigation, and tracking reported in the literature to be considered as µn-Bots design trade-offs being shown in Figure 1.

Micro/nanobots (µn-Bots) design trade off.

Nature-inspired innovations have been pursued to build µn-Bots. For example, inspiration from the natural movement of a biological microorganism caused by the hydrolysis of bioenergy, such as the swim propulsion of sperm and bacteria induced by the deformation of their bodies into an oar-like or screw-like shape, respectively, could lead to the motivation for the development of µn-Bots driven by chemical reactions [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Although any µn-Bot, whether human-controlled or self-driven, requires a power source to move at the either microscopic or nanoscopic scale, which further involve a design trade-off concerning their size and weight. However, such design trade-off between the power, size, and weight become severe in µn-Bots that can address with the utilization of soft materials or smart material like liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], shape memory alloy (SMA) [10], liquid crystal polymer (LCP) [9], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], hydrogel [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], liquid metal [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], and many other. The µn-Bots with soft materials can be also driven by verities of external stimuli, including magnetic fields [39], [40], electric fields [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], temperature gradients [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], chemical reactions [52], [53], [54], [55], acoustic fields [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], and light fields [4], [5], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], which is primarily background for their classification. Light, a potent and renewable source energy, plays a pivotal role in the very existence of life on earth [61], [69]. Nowadays, the potential of light will be seen in diverse areas, including integrated photonics circuits, micro/nanofabrication, material processing, information processing, quantum computing, single-molecule detection, and many more [62], [63]. So, to actuate and regulate the micro and nano-scaled structures with the light is not surprising. In this back drop, the technology has witnessed an evolution of light-driven micro/nanomachines in the recent past due to their enormous applications in micro/nanoscale manipulators, micromachined space exploration components, nano-sized cell positioning and control, micro/nanorobots for drug delivery, etc. Such µn-Bots not only have an attribute of their size but are also attributed to an escalating need for micro/nanoscale functionalities with touch-free optimum control, including propulsion, self-powered and controlled activation, energy efficiency, intelligence, navigation, and tracking [64], [65].

The general driving/actuation mechanism of the soft µn-Bots is classified here in the perspective of optical light functionality rather than the convention classification used previously into the nonoptical and optical actuation mechanisms discussed in detail at Section 2. However, optically triggered µn-Bots also have another classification based on their propulsion mechanism, which includes optical tweezers [66], [67], photochemical [68], photothermal [70], photomechanical [71], [72], and many other propulsion mechanisms. We present the design tradeoff, fabrication techniques, materials, and applications of optically triggered µn-Bots over other actuation methods.

The paper consists mainly of seven different sections, where the first section gives an introduction to the motivation for its latest research trends in general. The second section is more about the various actuation mechanisms of µn-Bots and why light actuation is gaining popularity in their design. Section 3 mainly discusses the numerous types of soft materials employed in designing nonoptical triggered µn-Bots prototypes for specific applications. Several optically induced techniques for the realization of µn-Bots are described in Section 4. Section 5 is mainly about the optically driven µn-Bots prototypes, which attract the research community and industry to quite a few interesting applications, including terrestrial micro/nanorobots, grabbing and transporting objects, environmental restoration and surface cleaning, bionic technology, biomedical applications, and biocompatibility insight in soft bio µn-Bots. Section 6 explores the potential and challenges of a multimodal collaborative control strategy combining optical actuation with another actuation mechanism. Finally, the challenges and advantages are summarized in Section 7 as a conclusion. So, the advances in optically driven µn-Bots aim to fascinate and motivate through their innovative design, functionalization, fabrication, and application in a broad horizon.

2 General actuation mechanism in soft µn-Bots

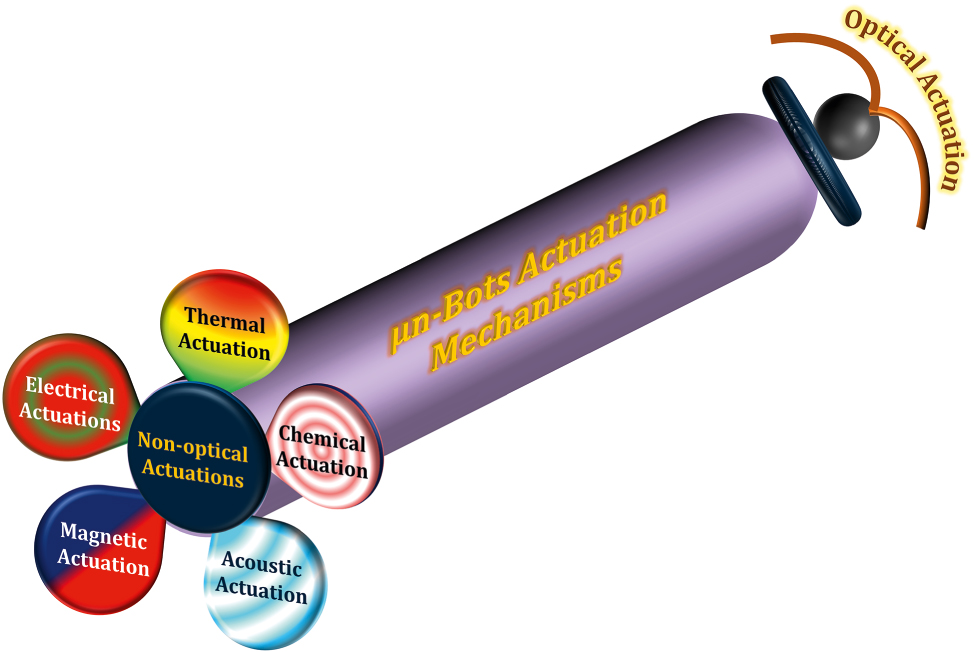

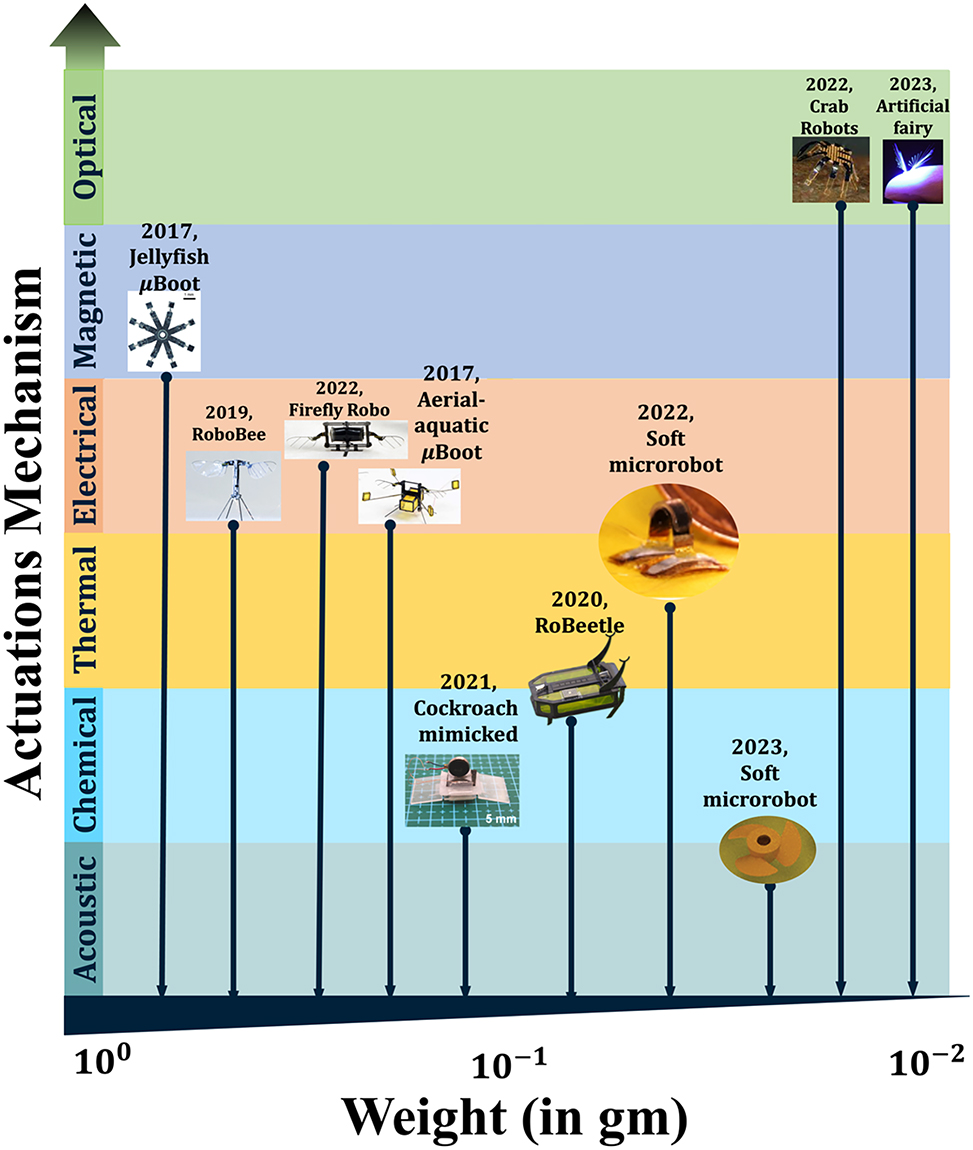

Unlike their macro counter parts, micro/nanorobots rely heavily on their activation/driving mechanisms. The functional material body of the micro/nanomachine and its excitation signal plays a crucial role in the whole functioning and localized control of the device. So, for the ease of understanding, from the perspective of the present study on light-driven micro/nanorobots, the soft µn-Bots are categorized in general based on their activation/driving mechanisms whether they rely on nonoptical methods or that of optical actuation mechanisms illustrated in Figure 2. We have also tabulated the same in Table 1 for a quick comprehension. The nonoptical actuation mechanism mainly covers actuation due to stimuli other than light, including magnetic, electric, thermal, acoustic, and chemical. However, the optical actuation mechanism is preliminarily driven by the light–matter interaction that triggers one of the following: the chemical reaction, mechanical force, deformation, etc., and accordingly it could further subcategorized as shown in Figure 3.

Actuation mechanism of soft µn-Bots.

General actuation mechanism of µn-Bots.

| Actuation mechanism | Material type | Applications | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic actuation | Magnetoactive elastomer polymer | Soft microrobot, microgripper, origami folding | [73], [74], [75] | |

| Ferromagnetic | Ferromagnetic soft catheter robot | [73], [76] | ||

| Paramagnetic (NdFeB) | Millimeter untethered swimmers, microwire steering, and origami fish steering | [77] | ||

| Magnetic microparticles | Microrobot, microgripper, helical microrobot | [74] | ||

| Magnetized nanocomposite hydrogel | Actuators | [76] | ||

| Magnetic liquid metal | Biomimetic soft robots, reconfigurable actuators | [31] | ||

| Electrical actuation | Silicon | Solar powered microrobot, energy harvesting, sensor and actuators | – | |

| Metal | Drug delivery, sensor, and actuators for robotics. | – | ||

| Piezoelectric | Sensor, actuator, energy harvesting and robot propulsion | [44] | ||

| Conductive polymer | Actuator, soft artificial muscles | [42], [43] | ||

| Dielectric elastomer | Actuator, soft artificial muscles, and microrobots | [78], [79], [80], [81] | ||

| Liquid metal | Soft robotics, micromotors | [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38] | ||

| Thermal actuation | SMA | Soft robotics and actuators | [10], [82] | |

| Bimetallic strips | Multi DOF robot | – | ||

| Metals | Thermal actuator for robotic propulsion | – | ||

| Polymer | Soft robotics and actuators | [48], [49], [50], [51] | ||

| Chemical actuation | Polymer | Soft material, complex shape molding, microfluidic channel, and biocompatible shape modeling | – | |

| Hydrogel | Drug delivery release and control | [83] | ||

| Shape memory polymer | Sensor application | – | ||

| Metal | Catalyst for chemical reactions | [82], [83], [84] | ||

| Liquid metal | Self-propelled micro/nanorobot | [29] | ||

| Acoustic actuation | Piezoelectric | Acoustic actuator and sensor | [85], [86], [87] | |

| Polymer | Complex shape molding, drug delivery, and biocompatible shape modeling | [85], [86], [87] | ||

| Fluid | Propulsion medium | [58], [59], [60], [85], [86], [87] | ||

| Optical actuation | Photo sensing material | Self-diffusion propulsion | [88], [89], [90] | |

| Organic compound material | Surface topography, cell capturing, and microprobe | [91], [92] | ||

| Photocatalytic material | Self-electrophoretic propulsion | [93], [94] | ||

| Photothermal material | Photoacoustic tomography, cargo transport, water treatment, and swarming of micro/nanorobot | [7], [8], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99] | ||

| Photo deformable material | Liquid crystal polymer | Programmable actuators and crawler | [9], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20] | |

| Hydrogel | Thermal responsive actuator, light-driven actuators | [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27] | ||

| Liquid metal | Opto-thermophoretic propulsion, opto-electrophoretic propulsion | [28], [30], [100] | ||

Classification of optically actuated soft µn-Bots.

2.1 Magnetic field–based excitation

The magnetic field–driven soft µn-Bots achieve propulsion by converting magnetic energy into mechanical energy, which is very prevalent, simple to make, and easy to use [39], [40]. Typically, magnetic material is incorporated on the surface of the soft µn-Bots or embedded inside the soft µn-Bots body to interact with externally controlled magnetic fields. However, the required magnetic field strength may change depending on the environment in which the soft µn-Bots need to move. For example, a soft body such as hydrogel can behave as a microrobot by incorporating ferromagnetic material evenly distributed on the actuating part or suspended in its body, whose orientation and strength are adjusted at the time of microfabrication using a permanent magnet or an electromagnet [76]. The propulsion of such a soft µn-Bots is controlled by an external magnetic field induced by a magnetic field generator, either an electromagnet or a permanent magnet. Precise movement of the soft µn-Bots is achieved by controlling the magnetic field strength and orientation without physical contact. This is a significant advantage where physical contact is susceptible to damaging the µn-Bots or its surrounding environment. It offers exceptional potential in medical applications because its penetration depth inside the nonpenetrating tissue is excellent, and it is commonly used for drug delivery [101], target therapy [102], [103], cargo transport [40], [104], and environmental remediation [105]. However, several challenges, such as magnetization, film coating, and fabrication methods, are encountered in the development of magnetically driven soft µn-Bots. Furthermore, magnetic actuation is ideal for driving soft µn-Bots with sizes ranging from tens to hundreds of microns. However, significant limitations in driving microrobots with sizes of several microns, particularly in magnetic actuation, necessitate more sophisticated auxiliary drive and control equipment, which in turn necessitate a complex hardware system.

2.2 Electrical actuation mechanism

Electrically powered µn-Bots are predominantly characterized by the properties that include charge, conductivity, and a semi-conductive nature that interacts with the activating electric field [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. The orientation, position, and speed of such µn-Bots are efficiently manipulated with the control of the applied electric field [42], [43], [44]. The electric field gradient in µn-Bots is harvested with numerous methods, such as applying the required voltage to an electrode, piezoelectric actuator, or using a microfabricated structure [42], [43], [44]. However, µn-Bots can be remotely controlled by electrorotation, electro-percolation, and electrophoretic motion, which are the foundations of wireless control driven by AC and DC electric fields [45], [46]. However, it needs a special buffer and has a significant compatibility issue with bio samples and highly ionic media. In addition, such µn-Bots movement is limited because the electric field’s strength decays rapidly with increasing distance. Microgripper, microsurgery [44], microassembly [42], and microfluidics [45], [46] are a few examples of the electrical control of µn-Bots utilized in manipulating biological cells or assembling microscale components in a controlled way.

2.3 Thermally driven µn-Bots

Thermal actuation is another method that uses heat to regulate the motion of µn-Bots. Thermally actuated µn-Bots, also known as thermos-bots or micro thermomechanical systems (MTMS), are tiny machines that use heat energy to operate. Typically, it is constructed from materials having both thermal and mechanical properties. Thermally sensitive materials like shape memory polymers or metals are utilized that involve heating or cooling a particular regime of the µn-Bots, causing it to expand or compress to produce motion. The benefit of thermal actuation in the µn-Bots is the fast response time that can be achieved by readily applying or withdrawing heat using various methods, such as joule heating, infrared radiation, or laser heating. It can provide a straightforward and effective way of controlling motion. Furthermore, complicated motion patterns can be produced using thermal actuation by meticulously regulating the temperature distribution across the microrobot. Microgripper, drug delivery, and microsurgery are just a few of the thermally actuated µn-Bots or thermo-bots. For instance, a thermos-bot can be used to assemble microscale parts, transport medications to specific areas of the body, or carry out minute surgical procedures [47], [48], [49], [50], [51].

2.4 Chemical actuation of µn-Bots

The chemical reaction is especially advantageous for µn-Bots propulsion intended to operate in fluid environments, such as the human body, over other actuation techniques because it enables motion generation without external forces or power sources. Such µn-Bots movements and motion are controlled through chemical processes induced by chemical reactions to produce gas or a change in solubility. It can offer a reasonably straightforward and affordable way of controlling motion, which is a key benefit, and can be used to accomplish particular motion patterns and reactions, such as reacting to pH or temperature changes. The microtubular jet microrobots [52], catalytic micro/nanomotors [53], and electro-osmotic microswimmers [54], [55] are a few examples of chemically actuated µn-Bots whose motion is mainly regulated by the involved reaction rates. Diverse chemically actuated µn-Bots are utilized in applications such as medication administration, environmental tracking, and microfluidics. It can be widely used to regulate fluid movement in microchannels, transport medications to particular body parts, and observe the environment in real time [52], [53], [54], [55].

2.5 Acoustic actuation mechanism

Acoustic field-propelled µn-Bots, also known as acousto-bots or micro-acousto-fluidic systems, have great compatibility with biological environments because they require on-demand and noninvasive motions. Such µn-Bots are driven by employing the acoustic field distribution, which can be altered through amplitude, frequency, and phase using the interference principle. In acoustic actuation, sound waves produce pressures that work on the structure of the µn-Bots, propelling them in one direction or allowing them to carry out a particular job. Different methods, such as acoustic streaming, radiation pressure, or acoustic levitation, can be used to accomplish acoustic actuation. Acoustic streaming happens when sound waves cause vortices to form in a fluid setting. These vortices then combine to form a net fluid flow, which powers the µn-Bots. The force that sound waves apply to the surface of the µn-Bots, known as radiation pressure, propels them in the direction of the auditory source. So, such µn-Bots can be captured and operated in a precise way using acoustic propulsion. Microbead rotation and metal nanowire propulsion are a few examples of µn-Bots driven by the acoustic field [56], [57], [106], but they are limited in many applications because of their low resolution. One benefit of acoustic actuation is that it can be used to concurrently operate many µn-Bots, which is challenging to accomplish with other actuation techniques. Acoustic actuation is a potential method for µn-Bots use in medicine, such as medication administration or targeted treatment, because acoustic waves can also enter deeply into tissues [58], [59], [60], [107].

2.6 Optical actuation and manipulation of µn-Bots

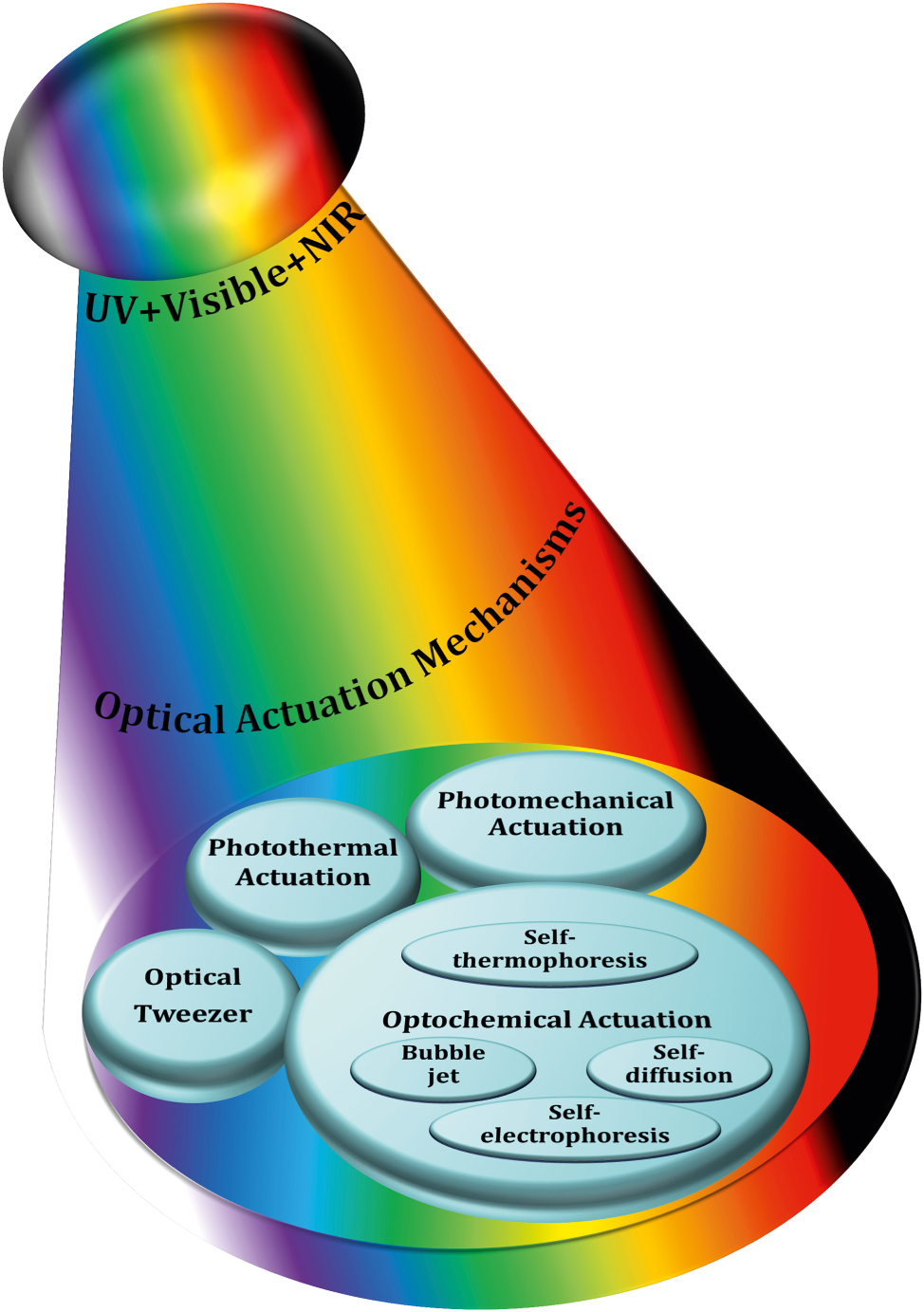

Light–matter interaction is the key in the optical actuation of µn-Bots that further depends on the operational wavelength regimes of light such as UV, visible, and IR and photosensitive properties of the functional material used for the fabrication of µn-Bots.

Here, we classify the principles and mechanisms of light-driven µn-Bots into primarily the categories of rigid type and nonrigid type. The rigid type soft µn-Bots typically has no deformation during the operation and manipulation. Also, it can be mostly driven with an optical tweezer, optical trapping, momentum transfer method, photochemical reaction, etc. However, the nonrigid type soft µn-Bots tend to deform during any operation, even during propulsion. Such nonrigid type soft µn-Bots can be designed in a materialistic way that is further controlled by light actuation, including the photothermal effect and photomechanical effect. The detailed classification of optical actuation schemes being reported in the literature, including an optical tweezer [69], [91], [92], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], optochemical reaction [88], [89], [90], [93], [94], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], photothermal [7], [8], [9], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [141], photomechanical [97], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], etc., is depicted in Figure 3.

Among all the above driving categories of µn-Bots, optical tweezers are one of the first µn-Bots propulsion mechanisms that are commonly used to control and manipulate the movement of 3D-printed rigid polymeric µn-Bots. It utilizes forces generated by highly focused light with steep intensity gradients, allowing for precise and noninvasive manipulation and actuation of tiny objects suspended in either air or liquid. It can serve as a tool for single-cell capture or as detecting probes for the object in the surface topography. However, the µn-Bots driven by optochemical actuation mechanisms are made with photoactive material, which often includes structures like Janus spheres, hollow tubes, and rods. It functioned with optochemical reactions such as photochromic and photocatalytic effects, converting chemical energy into motion. Such µn-Bots have potential applications for water purification and drug delivery in environmental protection and biomedical industries. On the other hand, optomechanical mechanisms are primarily used to drive nonrigid type µn-Bots made of soft materials like liquid crystal polymers (LCP). Also, photothermal actuation mechanisms can be used to drive optomechanical soft microrobots, optochemical microrobots, and 3D-printed hard polymeric microrobots, so they can be used to power a variety of µn-Bots, such as ones that pick up and place objects, mimic flowers, and act as fly traps. Section 4 will outline the working mechanisms and foundational principles behind such light-driven µn-Bots and their strengths and limitations.

We have summarized in general in Table 1, though it may not be all-exhaustive, the materials in the design of soft µn-Bots and their actuation/driving mechanisms. However, several materials show both the characteristics that make used to achieve additional features in soft µn-Bots designs. The material, which response either of the magnetic, electrical, thermal, chemical, or acoustic field, considered as the nonoptical actuations. However, optically triggered µn-Bots are a fascinating and rapidly developing field of research that holds promise for a wide range of applications. Several types of optical materials are commonly used to develop light-driven soft µn-Bots, including photo-sensing, photocatalytic, photothermal, and photo-deformable materials. Based on the studies of various nonoptical and optical materials, Table 2 summarized the optimum materials that can be utilized for the design of µn-Bots in the optical and nonoptical actuations methods.

Materials in µn-Bots actuation.

| Materials | µn-Bots actuation mechanism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical | Nonoptical | |||||

| Magnetic | Electrical | Thermal | Chemical | Acoustic | ||

| Metal thin film/nanoparticles |

|

|

|

|

||

| Liquid metal |

|

|

|

|

||

| SMA |

|

|

|

|||

| Photoresists |

|

|

||||

| Polymers |

|

|

||||

| Photo sensing materials |

|

|||||

| Organic compound materials |

|

|||||

| Photocatalytic materials |

|

|

||||

| Photothermal materials |

|

|||||

| Liquid crystal polymer |

|

|||||

| Hydrogel |

|

|

||||

| Silicone/PDMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| Silicon |

|

|||||

| Conductive polymers |

|

|||||

| Carbon nanotubes |

|

|||||

| Bimetallic strips |

|

|||||

| Ceramics |

|

|

||||

| Piezoelectric materials |

|

|

||||

| Microbeads |

|

|||||

| Fluids |

|

|||||

| Magnetic microparticles |

|

|||||

| Magnetoactive polymers |

|

|||||

| Magnetized nanocomposite hydrogels |

|

|||||

| Paramagnetic (NdFeB) |

|

|||||

| Ferromagnetic |

|

|||||

3 Nonoptical actuation mechanism in soft µn-Bots: applications

Here, we outline in detail the state of art in the design of various soft µn-Bots by utilizing the nonoptical actuation methods includes magnetic, electric, thermal, chemical, and acoustic actuation. Also, it infers the advantages of soft material even in the other nonoptical actuation methods in the improvement of the power to weight trade-off, efficiency, size, and weights.

3.1 Magnetic field–driven soft µn-Bots

A unique method for manufacturing flexible, untethered, fast-transforming soft miniature robots by 3D printing ferromagnetic domains onto elastomers using Magnetic Field Assisted Projection Printing (M-FAPP) [73]. While printing, a magnetic field is applied to the dispensing nozzle to reorient the particle to achieve patterned magnetic polarity, which has better power density and actuation speed compared to existing active 3D-printed materials. This technique can be utilized for reconfigurable flexible soft electronics, enabling the soft robot to roll, crawl, transport drugs, and microgripping. The structure’s fold is encoded with alternating oblique patterns of ferromagnetic domains, hollow cross encoded with alternating ferromagnetic domains along the perimeter, quadrupedal and hexa-pedal structures enabled by folding of the magnetically active segments surrounding the magnetically inactive segments. A hexa-pedal structure demonstrated wrapping an oblong pharmaceutical pill, and a horizontal leap of a 3D auxetic structure upon sudden reversal of the applied magnetic field direction while attenuating the field strength by rotating a permanent magnet by 90° as shown in Figure 4(A). Another approach has been proposed to develop small-scale, flexible robots capable of fine control and diverse locomotion. This has potential applications in object manipulation, drug delivery, and minimally invasive procedures. The robot is made by patterning magnetic microparticles in an elastomer matrix. The control of magnetic particle reorientation and encoding can be done using selective UV lithography. This magnetization profile allows multiaxis and higher order bending at large angles. The physics-based model accurately predicts the change in shape due to magnetic actuation [74]. The study presents a system for patterning discrete 3D magnetization using a UV-curable elastomeric matrix composite. The materials are about 80 μm thick and have an actuating magnetic field of 200 mT for the “accordion” and less than 20 mT for all others. The schematic of an untethered multi-arm magnetic microgripper, magnetization profile, and working mechanism is shown in Figure 4(B){i}. Also, the conceptual model of a cargo transportation task is illustrated in Figure 4(B){ii}. The locomotion of the microrobot is demonstrated in silicone oil, as shown in Figure 4(B){iii}, which lifts the body weight and slows down shape changes of the gripper in response to an open-loop controlled magnetic field. Also, microrobot locomotion and velocity are slower compared to water environments. An untethered jellyfish-inspired soft miniature robot has multiple functionalities by generating a controlled flow of fluid around its body using elastomer lappets, which are magnetic composite [75]. These elastomer lappets are actuated in response to external oscillating magnetic fields. Predation-inspired manipulation of objects was achieved by the physical interaction of the soft microrobot’s motion and incurred fluidic flow due to it. The study explores the design and behavior of a jellyfish-inspired swimming soft millirobot, which mimics the deep clefts between two adjacent lappets. Kinematics and flow structures are achieved with the motion sequence, velocity and vorticity fields, and wake structures visualized by fluorescein dye. The robot and animal were compared in two kinematic metrics: bell fineness and lappet velocity, as shown in Figure 4(C).

![Figure 4:

Magnetic field–driven soft bots. (A) Locomotion of hexapedal structure under a rotating magnetic field through a permanent magnet. Reproduced with copyright permission from [73]. (B) (i) Schematic, magnetization profile, and principle mechanism of a magnetic microgripper. (ii) Cargo transportation task. (iii) Cargo transportation in silicone oil environment. Reproduced with copyright permission from [74]. (C) (i) Schematic of jellyfish-inspired soft magnetic microrobot made of magnetic elastomer composites. (ii) Microrobot locomotion in the contraction and recovery phase. Reproduced with copyright permission from [75]. (D) (i) Bioprinted ferromagnetic soft catheter robot inside the human body through small incisions. (ii) Comparison of traditional printing systems with rigid nozzles and a soft polymer matrix with hard-magnetic particles and polylactide mesh. (iii) FSCR fabrication overview. (iv) Translational and rotational motion using four permanent magnets. Reproduced with copyright permission from [76]. (E) Conceptual model of magnetically actuated quadruped soft bionic microrobot locomotion includes walking, gripping, and transport in gastric biopsy. Reproduced with copyright permission from [149]. (F) (i) Self-folding catheter tool using MaSoChain. (ii) Fabrication and components of MaSoChain. (iii) Push out and pull back mechanism of the MaSoChain inside the sheathing tube. (iv) Demonstration of MaSoChain folding in the human body, such as heart ventricles, colon, stomach, and bladder. Reproduced with copyright permission from [77].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_004.jpg)

Magnetic field–driven soft bots. (A) Locomotion of hexapedal structure under a rotating magnetic field through a permanent magnet. Reproduced with copyright permission from [73]. (B) (i) Schematic, magnetization profile, and principle mechanism of a magnetic microgripper. (ii) Cargo transportation task. (iii) Cargo transportation in silicone oil environment. Reproduced with copyright permission from [74]. (C) (i) Schematic of jellyfish-inspired soft magnetic microrobot made of magnetic elastomer composites. (ii) Microrobot locomotion in the contraction and recovery phase. Reproduced with copyright permission from [75]. (D) (i) Bioprinted ferromagnetic soft catheter robot inside the human body through small incisions. (ii) Comparison of traditional printing systems with rigid nozzles and a soft polymer matrix with hard-magnetic particles and polylactide mesh. (iii) FSCR fabrication overview. (iv) Translational and rotational motion using four permanent magnets. Reproduced with copyright permission from [76]. (E) Conceptual model of magnetically actuated quadruped soft bionic microrobot locomotion includes walking, gripping, and transport in gastric biopsy. Reproduced with copyright permission from [149]. (F) (i) Self-folding catheter tool using MaSoChain. (ii) Fabrication and components of MaSoChain. (iii) Push out and pull back mechanism of the MaSoChain inside the sheathing tube. (iv) Demonstration of MaSoChain folding in the human body, such as heart ventricles, colon, stomach, and bladder. Reproduced with copyright permission from [77].

Furthermore, a bioprinting method has been employed to fabricate a soft catheter ferromagnetic robot (FSCR) capable of minimally invasive in-the-place bioprinting based on computer-controlled magnetic actuation [76]. This robot is designed by dispersing ferromagnetic particles in a polymer fiber–reinforced matrix. It can be driven by a magnetic field, which is superimposed to get controlled and precise printing. Multiple patterns are printed on a planar surface, and minimally invasive hydrogel bioprinting is demonstrated on a rat model considering the natural organ’s nonplanar surface. The FSCR comprises a soft polymer matrix with dispersed hard-magnetic particles and a polylactide (PLA) reinforcing mesh with magnetic polarity programmed along its axial direction. Digital data instruct the numerical control strategy of the FSCR, and operations are instructed via the rotation and translation of four permanent magnets. In vitro, minimally invasive bioprinting of conducting hydrogel on porcine tissue surfaces is explored. The 3D scan and reconstruction of the curved surface of porcine tissue are conducted, and the 3D spiral printing path is designed on the reconstructed surface. Images of the minimally invasive bioprinting process of conducting hydrogel on porcine tissue at various times are shown in Figure 4(D). An untethered soft, quadruped, thin-film magnetic microrobot has been demonstrated for biomedical applications and small-scale micromanipulation [149]. The soft material makes it deformable and minimally invasive. This robot has four flexible magnetic legs and a nonmagnetic body that achieves controllable locomotion in an external magnetic field, which gives it the walking ability to cross obstacles in the stomach model. Gripping, transportation, and release of a microbead were demonstrated by controlling the conical angle of the externally applied magnetic field, as shown in Figure 4(E). A chain of magnetic soft robots that can form large assemblies by self-folding using a combination of magnetic and elastic energies in a stable configuration has been presented [77]. Repeated disassembly and assembly with programmable functions and shapes are achieved by pulling and pushing the soft robotic chain with respect to the catheter sheath. These chains are compatible with magnetic navigation and produce desirable functions and features that are difficult to obtain with surgical tools. The basic self-folding unit of MaSoChains is composed of rigid segments connected by soft segments, with small NdFeB magnets embedded at the same height as the surrounding surface. The folding process is initiated when a new segment is pushed out of the sheathing tube, where elastic and magnetic energies are stored. The MaSoChain is disassembled by pulling back with the guiding of the fixed tube. The three-segment MaSoChain structure is a foldable endoscope designed with three functional segments: the camera module, the magnet module with a large steering magnet, and the channel module through which a biopsy gripper can pass. The capsule endoscope can be actively steered using an external magnetic field. The process includes complete assembly, magnetic navigation, locking on the target, insertion of biopsy forceps, performing a biopsy, and retraction of the capsule, as shown in Figure 4(F). In addition to the above, the magnetic composite liquid metal droplet (LMD) was demonstrated by immersing a Galinstan liquid metal droplet in HCL, mixing it with 50 μm mesh-sized Fe powder, and gently stirring it at room temperature for 3 min. Such composite magnetic LMDs have reversible deformation, stretchability, and motion in response to applied magnetic fields. The composite magnetic LMD appeals to the potential application in reconfigurable electronics, soft µn-Bots, and micromotors [31]. Recently, a new class of magnetically controlled microscopic robots “diffractive robots” has been introduced that function at the visible light diffraction limit. The untethered microbots incorporated the nanometer-thick mechanical membranes, programmable nanomagnets, and diffractive optical elements to enable visible light diffraction and complex reconfigurations under millitesla scale magnetic fields. Such microbots demonstrated applications include subdiffraction imaging, tunable optical beam steering and focusing, and highly sensitive force sensing [150].

3.2 Electrically actuated soft µn-Bots

A 175-mg hybrid aquatic and aerial multimodal miniature-scale robot with versatile propulsion was developed to use the multimodal flapping technique to transition between aquatic and aerial environments [78]. Climbing and turning speeds achieved by them on acrylic surfaces are 0.3 cm/s and 23.6°/s, respectively. However, on a 30° inclined acrylic surface, its speed was 0.04 cm/s. This robot is lightweight, stable, equipped with controllable adhesion, and has limited sensing and actuation capabilities. The titanium top plate of the chamber includes porous apertures, while the sparking plate is made up of stainless-steel plates and a copper sparker. The robot is capable of aerial hovering, air-to-water transition, swimming, water-to-air transition, impulsive takeoff, and landing. It can transition from air to water, swim to the water surface, emerge from the water surface by capturing gas from electrolysis, and takeoff and landing as shown in Figure 5(A). The locomotion of a small-scale quadrupedal robot weighing 1.4 g attached to a 47 mg adhesion pad was demonstrated on inclined and inverted surfaces [79]. It measures 4 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm and weighs 47 mg with a compliant adhesive pad. A robot climbing a 30-degree gradient is demonstrated with an average speed of 0.04 cm/s, the robot climbs 13 cm in 311 s. The robot dragged down a horizontal surface while remaining attached via capillary adhesion. On a dry surface, the robot is pulled at 0.6 cm/s.

![Figure 5:

Electrically actuated soft bots. (A) (i) Schematic of a hybrid aquatic and aerial multimodal miniature-scale robot. (ii) Demonstration of robot locomotion, such as aerial hovering, air-to-water transition, swimming, water-to-air transition, impulsive take off, and landing. Reproduced with copyright permission from [78]. (B) (i) A CAD model of a flapping-wing robot, driven by a DEA. (ii) The unstable lift-off of a 155-mg robot driven by one DEA, which flips upside down due to unstable body pitch rotation. Reproduced with copyright permission from [80]. (C) (i) The perspective view of a flying insect-inspired miniature robot using two DEAs. (ii) Independent motion of two DEAs in either forewings or hindwings on condition. Reproduced with copyright permission from [81].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_005.jpg)

Electrically actuated soft bots. (A) (i) Schematic of a hybrid aquatic and aerial multimodal miniature-scale robot. (ii) Demonstration of robot locomotion, such as aerial hovering, air-to-water transition, swimming, water-to-air transition, impulsive take off, and landing. Reproduced with copyright permission from [78]. (B) (i) A CAD model of a flapping-wing robot, driven by a DEA. (ii) The unstable lift-off of a 155-mg robot driven by one DEA, which flips upside down due to unstable body pitch rotation. Reproduced with copyright permission from [80]. (C) (i) The perspective view of a flying insect-inspired miniature robot using two DEAs. (ii) Independent motion of two DEAs in either forewings or hindwings on condition. Reproduced with copyright permission from [81].

Recently, a flying insect–inspired miniature robot developed with the dielectric elastomer actuator (DEA)-based soft artificial muscle flapping–wing robot as shown in Figure 5(B){i}, which contains an actuator, connector, four-bar transmission, wing, and hinge capable of large deformation in an open-loop condition, showed relatively stable behavior [80]. This multilayer DEA has a power density of 600 W/kg and a resonance working frequency of 500 Hz, weighing 100 mg. When connected to the robot’s transmissions, the DEA is prestrained by 2 %, resulting in a static stroke angle bias of about 15°. The rotary wing stroke motion is translated from the DEA extension and contraction. The active and passive wing strokes and pitch motion of the robot are depicted in Figure 5(B){ii}. The flapping wing action is carried out at a frequency of 280 Hz, with time normalized to a flapping period. The passive wing pitch rotation is caused by the left-wing stroke rotation. The robot is tethered, requiring off-board amplifiers and external image processing to control flight. Utilizing such 4-DEA flapping wings as shown in Figure 5(C){i} demonstrates that the dragonfly-inspired aerial maneuvering robot weights 317 mg with a maximum lift-to-weight ratio of 1.49 at a 350 Hz operating frequency [81]. An at-scale soft robotic dragonfly is designed with two DEAs that individually drive a pair of wings. In reaction to a high-voltage driving signal, the DEA expands or contracts, connecting to linear four-bar transmissions. The DEA’s translational motion is turned into a rotating wing stroke action. The DEA directly controls the wing stroke action, while a compliant wing hinge passively mediates the wing pitch rotation. High-speed camera shots show tests with either the forewings or the hindwings turned on, as shown in Figure 5(C){ii}.

Subsequently, low voltage and high endurance flight for power-dense DEA-based soft miniature robots were demonstrated. It showed that a 143 mg DEA generates 1.15 mm displacement at 0.36 N force when operated at 400 Hz and achieved a lift-to-weight ratio of 3.7 at 500 V. Such DEA requires a high driving voltage compared to electromagnetic motors and piezoelectric bimorphs [151]. Also, the electro-luminance property was introduced into DEA to realize the concept of Firefly, which has the additional benefit of communication and motion tracking for such an aerial microrobot [152]. It consists of highly transparent electroluminescent particles embedded in four DEA, which light up simultaneously when electro-luminance particles are excited with a high-frequency electric field (>40 V/μm) generated at 400 Hz during the flying condition. The electrostatic flexible film actuator-based millimeter-scale robot was demonstrated in Figure 19(E) [153]. This, being robust and compact, has a power density of 61 W/kg. These actuators are like biological muscles, have a hierarchical structure with components ranging from electrodes to arrays to laminates, and are often constructed of flexible materials. As a result, these actuators may be designed to perform a wide range of manipulation and movement activities similar to actual muscle while being robust and compact. A typical actuator can provide 85 mN of force with a 15 mm stroke, a size of 28 × 5.7 × 0.3 mm3, and a weight of 92 mg. Two millimeters-sized robots, an ultra-thin earthworm-inspired robot, and an intestinal muscle-inspired endoscopic device for tissue excision demonstrate the use of these actuators. The earthworm robot conducts inspections in a small area with an onboard camera. They also performed tissue-cutting and piercing tasks, as shown in Figure 5(E){ii}. Furthermore, in recent years, electrical actuation techniques of soft materials like LMD (Galinstan, E-Galinstan) have been demonstrated for several applications, including microactuators, micromixers, micropumps, and tunable antennas [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. An innovative composite LMDs based soft µn-Bots have been demonstrated by engulfing a functional magnetic framework into an LMD. The propulsion of LMD is based on the Marangoni effect, in which liquid metal experiences motion in an immersed NaOH solution due to the surface tension gradient formed on the LMD surface due to the applied electrical stimulus. LMD has been entrusted with actuating and enhancing cargo-carrying capability without destroying the intrinsic properties of LMD. An external electric or magnetic field can assemble or disassemble the magnetic framework from the LMD. Complex motions of liquid metal marble, like climbing, jumping, and rotation, have been demonstrated in NaOH solution environments with the applied electrical stimulus. Also, these LMD are loaded with drugs that can be released by laser heating [37]. Apart from above, a pioneering design of tiny motors based on LMD has been demonstrated to offer significant benefits, including ease of fabrication, maintenance-free, and relatively low cost over conventional motor technology. This technology holds immense potential in a wide range of fields, including soft electronics, soft robotics, microelectromechanical systems, and microfluidics [38].

3.3 Thermally actuated soft µn-Bots

An untethered microscale system is developed to combine multiple functionalities such as actuation, motion, and communication has potential applications in drug delivery and robotics [84]. The system comprises flexible and rigid components, including sensors, actuators, microelectronic circuits, power supplies, engines, and controllers integrated into one platform. This flexible microsystem can control actuation and locomotion, driven by wireless power. The microsystem called the motile twin-jet-engine microsystem (MTJEMS) consists of two catalytic micro-engines shaped in tubes connected by a flat polymeric structure, as shown in Figure 6(A){i}. A square coil integrated into the platform receives inductive power through inductive coupling. The direction of the motion is controlled by locally heating the catalytic engine. This platform can also integrate LEDs and a thermos-responsive micro-arm to perform grasping and releasing tasks. MTJEMS are made in several steps, such as strained polymeric layer stacks joined by a polyimide layer, symmetric MTJEMS with a power receiver coil, heater wires, and symmetric Pt catalyst pads, and asymmetric MTJEMS with a power receiver coil, heater wires, and asymmetric Pt catalyst pads. The study explores the local heating effect of the MTJEMS, a catalytic engine, through wireless energy transfer and locomotion. Heating the Pt area in one catalytic engine results in a faster emission rate of O2 gas bubbles. Figure 6(A){ii} shows bubble generation without wireless energy transfer and with wireless energy transfer (voltage of transmitter coil, 12 V). The complex trajectory of the asymmetric MTJEMS for different voltages of the transmitter coil is also examined in Figure 6(A){iii}. The inductive heating of coils enables remote control of the opening and closing of the soft micro-arm on the MTJEMS. As for mechanical performance, the MTJEMS can also recover shape by squeezing its shape with a tweezer in the DI water environment depicted in Figure 6(A){iv}. The results provide insights into the catalytic engine’s performance and potential applications in various fields.

![Figure 6:

Thermally actuated soft bots. (A) (i) Design schematic and components of the MTJEMS. (ii) Trajectory of MTJEMS with 12 V supply. (iii) Trajectory of MTJEMS with different supply voltages. (iv) Shape recovery of MTJEMS. (v) Switching of micro-arm from “closed” to “open” with the remote-controlled inductive heating. Reproduced with copyright permission from [84]. (B) (i) Conceptual design and working mechanism of soft climbing microrobot. (ii) Soft microrobot capability of climbing on various surfaces, flipping on the surface, and transitioning between them. Reproduced with copyright permission from [6].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_006.jpg)

Thermally actuated soft bots. (A) (i) Design schematic and components of the MTJEMS. (ii) Trajectory of MTJEMS with 12 V supply. (iii) Trajectory of MTJEMS with different supply voltages. (iv) Shape recovery of MTJEMS. (v) Switching of micro-arm from “closed” to “open” with the remote-controlled inductive heating. Reproduced with copyright permission from [84]. (B) (i) Conceptual design and working mechanism of soft climbing microrobot. (ii) Soft microrobot capability of climbing on various surfaces, flipping on the surface, and transitioning between them. Reproduced with copyright permission from [6].

Researchers have developed another unique thermally actuated design for microrobots by integrating highly malleable 3D actuators capable of climbing and transitioning on complex surfaces or rough terrains [6]. This small-scale voltage-driven soft actuator consists of liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs) and a bending 3D assembly that measures 10 mm and weighs up to 3 gm. It is capable of achieving an angle greater than 200° due to thermal effects. However, for climbing, it has a footpad with electro-adhesive properties. The conceptual design and illustrations of soft microrobots capable of climbing on both planar and curved surfaces are shown in Figure 6(B){i}. Their body length is approximately 6 mm. The microrobot can climb on various surfaces, flip over barriers, and transition between different surfaces, as shown in Figure 6(B){ii}, including climbing on glass ceilings, PI cylinders, glass spheres, and E. aureum leaves. It also shows three locomotion gaits: stepping gait on the same surface, transition-type flipping gait for transition, and forward-type flipping gait. Potential applications of these microrobots include search and rescue, environmental monitoring, and industrial inspection.

3.4 Chemical reaction driven soft µn-Bots

An 88 mg insect-sized crawling autonomous robot called RoBeetle was developed and powered by methanol’s catalytic combustion, which has 20 MJ/kg specific energy. The design consists of catalytic artificial micromuscles based on controllable Niti-Pt integrated with mm-scale mechanical control, as shown in Figure 7(A){i–ii}. The catalytic combustion of methanol under a Pt catalyst given below produces heat to raise the temperature of the nitinol SMA material, enabling martensite to undergo an austenite phase transformation.

![Figure 7:

Chemical reaction driven soft bots. (A) (i) Exploded view of the RoBeetle’s assembly. (ii) Schematic diagram of robotic actuation mechanism. (iii) Crawling on the sliding surface. (iv) Crawling with payloads. (v) Crawling on glass, pacopad, and polyurethane charcoal foam surfaces. Reproduced with copyright permission from [82].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_007.jpg)

Chemical reaction driven soft bots. (A) (i) Exploded view of the RoBeetle’s assembly. (ii) Schematic diagram of robotic actuation mechanism. (iii) Crawling on the sliding surface. (iv) Crawling with payloads. (v) Crawling on glass, pacopad, and polyurethane charcoal foam surfaces. Reproduced with copyright permission from [82].

The contraction occurs when fuel contacts the catalytic surface of the Nitinol-Pt composite wire, enabling microrobot actuation. Microrobot crawling was successfully demonstrated on different surfaces (such as glass, pacopad, and polyurethane charcoal foam) under different atmospheric conditions, climbing on inclines of different slopes, transporting payloads, and engaging in outdoor locomotion, as shown in Figure 7(A){iii–v}. Also, a writable 6-mg radio-frequency identification (RFID) chip and a booster antenna were put on the robot to enable simple interactions and identification in the environment through a microcontroller [82].

Recently, another moisture-induced electric power insect-scale untethered robot inspired by cockroach locomotion has been demonstrated. The design, assembly, and working mechanism of a microrobot powered by moisture, along with a comparison of the mass path of a cockroach with the robot’s center, are shown in Figure 7(B){i}. However, the moisture-based energy harvesting device also examines their electrical output characteristics under different RH conditions. Under various atmospheric conditions, the robot captures atmospheric water using a hygroscopic gel and utilizes a redox reaction to generate electricity of around 1.4 V voltage and 43 mA current. The energy-harvesting device embedded in the microrobot became a battery-less, self-powered microrobot whose asymmetric structural design enables forward locomotion with an average speed of around 4 cm/s [83]. Also, a biomimetic self-power LMD motor inspired by mollusk has been demonstrated [29] and can be subsequently moved by eating the aluminum flakes in the NaOH solutions. Without external energy input, the LMD motor maintains its autonomous and rapid motion for over an hour. The pliable LMD allows the motor to self-deform in response to varying conditions, enhancing its adaptability for specific tasks. This self-powered LMD motor holds significant potential to advance the domains of self-motion in robotic design, microfluidic systems, and reconfigurable intelligent devices in the foreseeable future.

3.5 Acoustic field–driven soft µn-Bots

A unique method for regulating the motion of microswimmers using sound waves is “acoustophoretic actuation,” which produces controlled fluid flows that can be used to push and manipulate them selectively [85]. The oscillatory motion of the trapped air bubble inside the polymer body of the swimmer propels it at resonance, enabling controlled, rapid rotational, and translational motion even in highly viscous liquids. A group of microswimmers can also be achieved by incorporating unique bubble sizes with resonance frequencies. The microswimmers were developed by exposing a PEG solution containing a photosensitive initiator called an oligomer solution to UV light through the swimmer’s mask. Also, the swimmers’ geometries and conical indents were controlled through UV exposure duration. The geometry and experimental design of acoustic microswimmers are emphasized by different types of swimmers: linear, rotational, and directional as shown in Figure 8(A){i}. A piezoelectric transducer delivers acoustic energy into a fluid-filled container lined with an acoustically absorbent putty surrounded by glass slides shown in Figure 8{A}{ii}. However, Figure 8(A){iii} depicts the acoustic oscillation of microswimmer bubbles causes significant acoustic microstreaming in water.

![Figure 8:

Acoustic field–driven soft µn-bots. (A) (i) Fluorescent images microswimmer. (ii) Microswimmer experimental demonstration with a piezoelectric transducer. (iii) Acoustic oscillation of microswimmer bubbles results in significant acoustic microstreaming in water. Reproduced with copyright permission from [85]. (B) (i) Nanoprinted microrobot on a glass slide. (ii) Nanoprinted microrobot propulsion mechanism under acoustic waves. (iii) SEM image of fully anisotropic and symmetric microrobot. (iii) Trochoidal random propulsion and directional forward motion of microrobots under ultrasound. Reproduced with copyright permission from [86]. (C) (i) Drug encapsulated 3D printed microrobot within its polymer matrix during cross-linking. (ii) Fluorescent microscope & SEM images of 3D-printed microrobot. (iii) Influence of asymmetric fins on the microrobots propulsion trajectories in response to acoustic waves. (iv) Demonstration of drug-loaded microrobots propulsion in mouse bladder excited by ultrasound. Reproduced with copyright permission from [87].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_008.jpg)

Acoustic field–driven soft µn-bots. (A) (i) Fluorescent images microswimmer. (ii) Microswimmer experimental demonstration with a piezoelectric transducer. (iii) Acoustic oscillation of microswimmer bubbles results in significant acoustic microstreaming in water. Reproduced with copyright permission from [85]. (B) (i) Nanoprinted microrobot on a glass slide. (ii) Nanoprinted microrobot propulsion mechanism under acoustic waves. (iii) SEM image of fully anisotropic and symmetric microrobot. (iii) Trochoidal random propulsion and directional forward motion of microrobots under ultrasound. Reproduced with copyright permission from [86]. (C) (i) Drug encapsulated 3D printed microrobot within its polymer matrix during cross-linking. (ii) Fluorescent microscope & SEM images of 3D-printed microrobot. (iii) Influence of asymmetric fins on the microrobots propulsion trajectories in response to acoustic waves. (iv) Demonstration of drug-loaded microrobots propulsion in mouse bladder excited by ultrasound. Reproduced with copyright permission from [87].

Another untethered, acoustically powered 3D-printed bullet-shaped microrobot was developed in which spherical air bubbles are trapped inside the body cavity resonated according to acoustic waves. The net fluidic flow steers the microrobot and induces attractive force toward the wall. A small fin is attached to the cylindrical body to enable unidirectional locomotion. Anisotropic coating with a soft magnetic nanofilm layer allows motion direction control under a uniform magnetic field. The combination of magnetic steering and acoustic power enables it to navigate and actuate the microrobot in hard-to-reach. confined areas minimally invasively [86]. The microrobots were built with two-photon lithography and displayed in water. Asymmetric microstreaming patterns formed by the pulsating microbubble and the planned “fin” structure were used to model the robot’s propulsion depicted in Figure 8(B){i–ii}. The totally symmetric and anisotropic designs were studied using scanning electron microscope images depicted in Figure 8(B){iii}. Under ultrasonic actuation, the symmetric microrobot’s trochoidal random propulsion path was observed, while the directional forward motion of the microrobot with a fin structure was detected. The fin structure was critical in establishing flow asymmetry, which allowed for unidirectional motion. The research looks at the resonance frequency of microbubbles trapped in the chamber of a robot. It consists of a microrobot array, a confocal image of the shell, and a microstreaming pattern with resonance frequency of f res = 237 kHz. The microrobot is submerged in a fluid medium, and an acoustic pressure map is displayed. The researchers also measured the average speeds of 2 μm tracer particles at various frequencies, normalized by the piezoelectric sensor voltage depicted in Figure 8(B){iv}. Another novel approach using bubble-based microrobots with complex geometries can efficiently swim with nonlinear trajectories in a mouse bladder, pin to the epithelium, and release therapeutic drugs slowly [87]. The asymmetric fins on the exterior bodies enable rapid rotational motions, and the encapsulation of dexamethasone in the microrobots tempers inflammation. These drugs carrying microrobots are 3D-printed with individual air bubbles using two-photon lithography depicted in Figure 8(C){i–ii}. Microrobots were stimulated with an acoustic traveling wave using a silicone spacer between the transducer and sensor. PBS was used as the propulsion medium, increasing air bubble stability due to increased surface tension. A sinusoidal AC signal was applied to the piezoelectric transducer, causing the microrobots to reorient, resulting in an air/liquid interface parallel to the substrate. This reorientation is due to secondary Bjerknes forces, which are attractive between the air bubble and the substrate depicted in Figure 8(C){iii}. Asymmetric fins aid in a variety of propulsion trajectories. Drug-loaded microrobots reduce inflammation in bladder tissue depicted in Figure 8(C){iv}. When stimulated by ultrasound, the bubble-based microrobots migrate through a mouse bladder until they come into contact with the bladder wall. Fins on the microrobots strengthen their pinning on the wall, allowing the drug to be gradually released to treat immune cells indefinitely. This system has the potential to provide an efficient medication delivery strategy in complex biological contexts.

4 Optically driven soft µn-Bots: principle & mechanisms

In the continuance of Section 2.6, this section explores the principles and mechanisms of light-driven soft µn-Bots that are categorized primarily into rigid and nonrigid types. The rigid type soft µn-Bots are typically driven with an optical tweezer, optical trapping, momentum transfer method, optochemical reaction, etc. However, the nonrigid type soft µn-Bots have the tendency to deform, including the photothermal effect and photomechanical effect.

4.1 Optically driven rigid µn-Bots

4.1.1 Two-photon polymerization technology for the fabrication of rigid µn-Bots

The two-photon polymerization (2 PP) technology is the most prevalent method for fabricating 3D-printed rigid microrobots. In 1931, Goppert-Mayer et al. first explained 2 PP theoretically [154], and Kaiser et al. experimentally validated it theoretically 30 years later [155], [156].

Typically, 2 PP is a micromachining technology that depends on the nonlinear interaction of photosensitive resin and a femtosecond light pulse [157]. Figure 9(A) shows single-photon polymerization (SPP) and two-photon polymerization (2 PP) [158]. Unlike standard single-photon polymerization, the 3D printing method is similar to 2 PP laser direct writing and also involves the 2 PP principle mechanism. 2 PP techniques involve the photopolymerization phenomenon caused by the two-photon absorption of the material. Two-photon absorption (TPA) occurs when a material molecule absorbs two photons at the same instant in time, which involves two absorption processes: sequential absorption and simultaneous absorption. Figure 9(B){i} shows the sequential absorption process that involves the transition of an electron from the intermediate state to the excited state. The first photon absorption transforms the absorbing material into an intermediate state, and then the second photon absorption transforms it into an excited state. The other simultaneous absorption process is also shown in Figure 9(B){i}, where the electron absorbs two photons of quantum states at the same time and is excited to a higher state without undergoing an intermediate state.

![Figure 9:

Polymerization mechanism. (A) Conceptual diagram of single-photon polymerization (SPP) and two-photon polymerization (2 PP). Reproduced with copyright permission from [158]. (B) (i) Two photon absorption mechanisms. (ii) Process steps for 2 PP. (c) Schematic of 2 PP device setups. Reproduced with copyright permission from [159].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_009.jpg)

Polymerization mechanism. (A) Conceptual diagram of single-photon polymerization (SPP) and two-photon polymerization (2 PP). Reproduced with copyright permission from [158]. (B) (i) Two photon absorption mechanisms. (ii) Process steps for 2 PP. (c) Schematic of 2 PP device setups. Reproduced with copyright permission from [159].

Figure 9(B){ii–iii} shows the primary mechanisms and processes involved in 2 PP technology, which have been recently used in the micromachining of 3D-printed rigid polymeric microrobots [159]. The light-driven lobed micropump fabricated through 2 PP techniques can be used for fluid delivery by controlling two rotors with laser light [160]. A lightweight turbine similar to a micromotor, through the 2 PP techniques, efficiently transforms light energy into driving torque compared to earlier reported rotors and can be potentially used in the applications of fluid pumping and mixing [161].

4.1.2 Optical tweezer enabled rigid µn-Bots

In 1970, Ashkin et al. pioneered optical trapping, which became a burgeoning field that was accredited with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics [162]. Optical trapping showed the capability of precisely manipulating differently shaped micro/nanoscale objects and materials like living cells, polymerized microspheres, and metal nanoparticles. So, the microrobot examples covered in this section are all controlled by optical trapping or optical tweezers (OT).

The generic OT system is developed with a laser, a microscope, and a pair of optical devices. Figure 10(A) shows that the schematics OT utilizes a strongly focused Gaussian beam to generate the optical operational force to operate and control the 3D-printed hard microrobots made of 2 PP technology [108]. However, the spheroid noticed by the researcher is the most stable capture, which has been validated through the use of beads of different materials and sizes; further, such shapes and structures could be utilized as handles, probes, and many more. The OT shown in Figure 10(B) ensures the momentum transfer between the photons and particles through the light–matter interactions [109]. Near the focus, the laser beams generate a well that induces potential due to repulsive and gravitational force interactions. A high refractive index (RI) object can be grabbed near the beam focus with the application of a strong gradient force. A 3D trapped OT was developed with the individually tunable 3D helical pattern designed by superposition of multiple plane waves that can be phase-engineered with a programmable spatial light modulator, as shown in Figure 10(C){i} [110]. Figure 10(C){ii} shows the simulated profile of the rotating phase and intensity of the triple arm rotor trap induced by a 3D helical pattern. Such an optical tweezer can be utilized for optical trapping and helically stacked micromotors. A few examples of OT-driven 3D-printed hard microrobots are shown in Figure 11, which are mostly fabricated with 2 PP techniques and typically small in size. The first probe designed for the surface topography analysis consists of four cylindrical capture handles that could be driven themselves and manipulated through OT as shown in Figure 11(A) [111]. In the surface topography measurement of the sample, the probe tip is close to the sample, where the tip trajectory is evaluated from its transverse scanning. After 1 year, an OT-driven probe was also developed for scanning the profile morphology of the samples [91]. A microtool-like probe was devised to detect the cotton fibers vibrations floating on water, as shown in Figure 11(B) [112]. It may be used in the identification of yeast, bacteria, and other self-vibrating specimens. A probe for cell elasticity measurement was developed, and their experiment schematic is depicted in Figure 11(C), where the probe detected the lateral growth of endothelial cells on the vertical polymer wall [113]. The obtained value of elastic modulus in this experiment is similar to other reported methods. Also, the probe prevents cell damage in the optical capturing process by using a spherical light capture point. Instead of serving as a probe, OT drives could use 3D-printed hard microrobots to capture the target objects. The OT-driven microrotor depicted in Figure 11(D) shows the capture of a single target object with the formation of six traps by utilizing two OT-driven microrotors [92]. Also, it can be repositioned in a 2D plane in any direction, with the direction and rotation rate of the microrotor controlled through the OT. However, the multiple target object capture relies on five OT-driven microrotors that limit the four DOFs of the target object for their capture. An OT-driven clamp was developed to capture live cells. It comprises a fork to clamp the cells and a sphere for optical capture, and Figure 11(E) shows that the cells can be captured by the OT-controlled forked clamp [114]. The indirect manipulation of biological particles with the hard microrobot avoids cell damage from the optical tweezer. Also, it has limitations on translational and rotational motion in two dimensions only, whereas rotation in three dimensions is a critical requirement in many cell operations. So, an OT-driven articulated microrobot was developed, as shown in Figure 11(F), which can spin at a different angle under the control of OT and is also capable of cell manipulation [115]. That makes it useful in sophisticated biological applications that need three-dimensional spatial control, such as nuclear transfer, embryo injection, single-cell analysis, and others. The OT-driven microrotor has four optical capture points for moving, capturing, and screwing the nuts, as shown in Figure 11(G) [116]. Also, this technique could be helpful in a microfluidic chip for fluid mixing and pumping. 3D optical twister-assisted reconfigurable helically stacked microrotors demonstrated through the light field generated with the interference of phase-engineered multiple plane waves [110], as shown in Figure 11(H){i}. Figure 11(H){ii–iii} demonstrates the trapping of 2 μm silica particles and the rotational locomotions of stacked helical microrotors with the 3D optical twister, respectively. Further, the multiple OT-driven microrotors are generated in rows, as shown in Figure 6(H){iv}, and in two rows, where their rotation directions are opposite each other, as shown in Figure 11(H){v}. Such microrotors have numerous applications, including micropumps, micromixers, microfluidics, and particle sorting. Similarly, 3D optical twister–assisted dynamic and reconfigurable optical trapping of microparticles was also demonstrated [117]. The experimental setup of dynamic and reconfigurable optical trapping is shown in Figure 11(I){i}. Figure 11(I){ii} demonstrates the trapping of the 2 μm silica beads and 0.5 μm polystyrene spheres in various lattice patterns. Such optical trapping can be efficiently utilized in biomedical applications, including kidney stone removal, drug delivery, etc. OT is easy to control and has potential applications in biomedicine. Also, it can precisely control the microrobot’s position within a position error of 20 nm. Typically, light-induced force in OT is in the order of pico-newton (pN), which effectively drives only tiny objects, so the perspective of microrobots is constrained by the material, structure, shape, and their applications. In addition, OT could be able to control numerous microrobots simultaneously, resulting in complex functionality and making it costlier due to the necessity of the hardware for beam modification and a software controller. To circumvent these constraints, the researchers introduce other light-induced driving mechanisms, including photo-induced dielectric electrophoresis, the photothermal effect, and a momentum transfer drive mechanism, to power the microrobot.

![Figure 10:

Fundamentals of optical tweezer mechanism. (A) Particles trapping through OT assisted strongly focused Gaussian beam [108]. (B) Illustration of momentum transfer between photon to particles and ray optics model for the gradient of forces due to light. Reproduced with copyright permission from [109]. (C) 3D OT demonstration induced by multiple plane waves. (D) Simulated profile for rotation phase and intensity of 3D OT. Reproduced with copyright permission from [110].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_010.jpg)

Fundamentals of optical tweezer mechanism. (A) Particles trapping through OT assisted strongly focused Gaussian beam [108]. (B) Illustration of momentum transfer between photon to particles and ray optics model for the gradient of forces due to light. Reproduced with copyright permission from [109]. (C) 3D OT demonstration induced by multiple plane waves. (D) Simulated profile for rotation phase and intensity of 3D OT. Reproduced with copyright permission from [110].

![Figure 11:

OT-driven rigid µn-Bots. (A) SEM image of 2 PP structured cylindrical probes. Reproduced with copyright permission from [111]. (B) Probe for the vibration measurement of floating cotton fibers in water. Reproduced with copyright permission from [112]. (C) Probe for the elasticity modulus measurement of cell membrane. Reproduced with copyright permission from [113]. (D) Microrotor to capture single target object. Reproduced with copyright permission from [92]. (E) Fabricated microclamp and their capturing process of cells. Reproduced with copyright permission from [114]. (F) Articulated microrobot motion and manipulation at several angles. Reproduced with copyright permission from [115]. (G) Structure, capture, movement and assembly of micro screw & nuts. Reproduced with copyright permission from [116]. (H) (i) Schematic of helical stacked microrotors profile. (ii) Tapping. (iii) Rotational locomotions. (iv-v) Multiple microrotor locomotions. Reproduced with copyright permission from [110]. (I) (i) Experimental setup of 3D OT. (ii) Optical trapping of in various lattice patterns. Reproduced with copyright permission from [117].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_011.jpg)

OT-driven rigid µn-Bots. (A) SEM image of 2 PP structured cylindrical probes. Reproduced with copyright permission from [111]. (B) Probe for the vibration measurement of floating cotton fibers in water. Reproduced with copyright permission from [112]. (C) Probe for the elasticity modulus measurement of cell membrane. Reproduced with copyright permission from [113]. (D) Microrotor to capture single target object. Reproduced with copyright permission from [92]. (E) Fabricated microclamp and their capturing process of cells. Reproduced with copyright permission from [114]. (F) Articulated microrobot motion and manipulation at several angles. Reproduced with copyright permission from [115]. (G) Structure, capture, movement and assembly of micro screw & nuts. Reproduced with copyright permission from [116]. (H) (i) Schematic of helical stacked microrotors profile. (ii) Tapping. (iii) Rotational locomotions. (iv-v) Multiple microrotor locomotions. Reproduced with copyright permission from [110]. (I) (i) Experimental setup of 3D OT. (ii) Optical trapping of in various lattice patterns. Reproduced with copyright permission from [117].

4.1.3 OET-assisted rigid µn-Bots

In 2005, Chiou et al. discovered the opto-induced electrophoretic technique (OET), which gained notable interest and has become a promising technology in µn-Bots design [118]. The µn-Bots driven with OET utilized the opto-induced DEP forces that integrate together the features of optics and electronics in the programming and contactless driving of µn-Bots. Compared to the OT system, the light source used in the OET system does not have a strange requirement, so an LED source with a digital micromirror device (DMD) can be used as a light source. The OET mechanism depends mainly on the distinctive properties of photoconductive substrates, which have a high impedance similar to resistors in the dark. However, when the photoconductive substrate is exposed to light, its impedance substantially decreases, and it becomes analogous to the conductor. So, Figure 12(A){i} shows an induced asymmetrical electric field in a liquid medium on the photoconductive substrate caused by a photoactivated virtual electrode developed through the dark and light patches created on the photoconductive substrate [119]. The device used in the OET drive, as shown in Figure 12(A){ii}, is easy to operate and can drive a large microrobot with a strong control force compared to OT.

![Figure 12:

OET-assisted rigid µn-Bots. (A) (i) Generic diagram of OETs indicating asymmetrical distribution of electric field. (ii) Device required for OET setups. Reproduced with copyright permission from [119]. (B) OET device setup for the manipulation of star shaped hydrogel microstructure manipulation. Reproduced with copyright permission from [120].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0152/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2025-0152_fig_012.jpg)

OET-assisted rigid µn-Bots. (A) (i) Generic diagram of OETs indicating asymmetrical distribution of electric field. (ii) Device required for OET setups. Reproduced with copyright permission from [119]. (B) OET device setup for the manipulation of star shaped hydrogel microstructure manipulation. Reproduced with copyright permission from [120].

Figure 12(B) shows a star-shaped hydrogel microrobot that utilized OET for transportation [120]. Also, the Tetris architecture has been made of a swarm of hydrogel microrobots that use assembly and manipulation through OET. Due to the biocompatible nature of hydrogel, hydrogel microrobots can encapsulate various cells. Also, it can be grouped into structures of desired shapes and sizes, which is extremely valuable in the application of microscale tissue engineering. The OET offers the benefits of rich biocompatibility, flexibility, and high efficiency. The OET-based system is able to sense complicated operations and causes numerous µn-Bots to work in tandem and autonomously. Such a system requires less equipment and can be implemented even with a basic microscope and low-cost optical projector. Such technology will greatly benefit the field of biological sciences.

4.1.4 Momentum-assisted rigid µn-Bots

Momentum is a physical quantity that quantifies the motion attributes, motion capabilities, and motion state of an object. It includes motion properties such as magnitude and direction that can be transferred from one object to another. The researcher has explored the potential to drive the micro/nano-object with photon momentum transfer [163]. A light-driven, reflective, surface-coated micron-shaped wedge can use the momentum of incident photons as a driving force to drive itself [69]. When the surface of the top wedge is illuminated by NIR laser light, the deflection of light from its reflected surface causes a change in momentum, resulting in the movement of the wedge in a particular direction. Micromotor rotational motion with laser light has been demonstrated with the nanoscale gold motor sandwiched between SiO2 square microdisk that can be spun by laser light [121]. It rotates by transforming the photon’s angular momentum into torque.

The optical metasurface-powered microscopic metavehicles have been designed to operate in water through 1,064 nm plane-wave illumination [164]. These metavehicles harness the momentum of light for propulsion and steering, showcasing the integration of metasurface design with light-driven motion at the microscale for complex patterns, self-correcting motion, and an application as transport vehicles for microscopic cargoes, which include unicellular organisms. Furthermore, light-driven microdrones equipped with individually addressable chiral plasmonic nanomotors as shown in Figure 13(A) have been designed, where two unfocused, circularly polarized beams at distinct wavelengths (830 nm and 980 nm) can be precisely controlled into two dimensions with all three independent degrees of freedom [165]. The approach, mimicking macroscopic quadcopters, overcame the limitations of optical gradient traps by enabling orientation-independent actuation using photon recoil from circular polarization. Recently, a gold cross antenna-based plasmonic nano-tweezer integrated into a microdrone transformed it into a microrobot capable of precise optical trapping and manipulating single nanoparticles as shown in Figure 13(B) [166]. The motors and tweezers were powered simultaneously by circularly polarized light, enabling seamless trap-transport-release cycles of fluorescent nanodiamonds, a feat unattainable with traditional optical tweezers. This advancement underscores the synergy between propulsion and functional manipulation in light-actuated µn-Bots.