Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

-

Heng-Yang Luo

, Tie-Fu Li

, Jia-Fu Wang

, Yu-Xiang Jia

, Rui-Chao Zhu

Abstract

Achieving high electromagnetic (EM) wave transmission with excellent angular stability is crucial for communication, detection, and guidance but remains challenging, especially when integrating other functions like out-of-band radar cross-section (RCS) reduction, which often degrades transmission. In this work, we propose to solve this problem by utilizing the longitudinal design freedom of metasurface. To this end, a typical longitudinally-coupled structure is proposed as the meta-atom for designing metasurfaces, which is composed of one layer of metallic meshes and one layer of metallic patch. By leveraging the synergistic effect of the plasma oscillation of the metallic mesh and the Lorentz resonance effect of the metal patch within meta-atom, we obtain a dual-polarization angle stable EM window (0°–80°) within the operating band. On this basis, without altering the structural parameters of the meta-atom, we utilize the longitudinal dimension to encode the reflection phases of out-of-band EM waves by flipping the meta-atom structure longitudinally, which can integrate out-of-band radar cross-section (RCS) reduction function without affecting the in-band transmission performance. To demonstrate this idea, prototypes were designed, fabricated and measured. Fabricated prototypes show good agreement between measurements and simulations, validating the method. This opens new paths for multifunctional EM windows in next-gen communication and radar systems.

1 Introduction

Electromagnetic (EM) waves will be reflected at the two interfaces due to impedance mismatch, which leads to poor transmission performance, enhanced reflected signals, and further increases the reflection of radar waves, especially for two materials with a large difference in dielectric constant. To enhance the transmission performance, the antenna radome usually adopts the half-wave wall design method [1], [2], [3], [4]. However, the half-wave wall limits the thickness and the transmission efficiency drops sharply when the angle increases. For TM polarized waves, they have a Brewster angle that can increase the transmission effect, while this is not applicable to TE polarized waves [5], [6], [7]. Therefore, in practical application scenarios, in addition to meeting the requirement of good transmission effect, it is crucial to ensure the wide angle domain angular stability under the two polarization modes (TE polarization and TM polarization). Since its inception, the metasurface has demonstrated excellent electromagnetic regulation capabilities and has played a significant role in addressing the aforementioned challenges [8], [9], [10]. Meanwhile, the suppression of reflected wave signals also deserves key attention.

It is precisely due to the critical role of electromagnetic transmission enhancement technology and the impetus from urgent practical application demands that many researchers have conducted relevant studies. Yongzhi Li et al. achieved an enhancement of TE-polarized transmittance by loading long metal strips in the fiber antireflection ceramic material plate [11]. Yuchu He et al. designed a double-layered fishnet antireflection structure which achieves excellent antireflection effects for both TE and TM polarizations [12]. Fengyuan Yang et al. designed a cascaded antireflection metamaterial which achieves high transmission of EM waves from air to water within the target band [13]. In order to expand polarization, Nima Bayat-Makou et al. designed a dual-polarization antireflection structure which can adjust its structural parameters according to the wave impedance of the medium within the target band to achieve efficient transmission of EM waves [14]. With the deepening development of information warfare, it is not only essential to achieve efficient electromagnetic transmission within the band but also crucial to consider stealth performance outside the band. Since its inception, metasurface technology has demonstrated an inherent capability to flexibly control EM waves [15], [16], [17], attributed to its exceptional electromagnetic properties.

It is already highly challenging to achieve EM waves transmission with exceptional angular stability. Furthermore, this capability plays a crucial and broad role in practical applications such as communication, detection, and guidance [18], [19]. If additional electromagnetic functionalities are integrated, it could potentially compromise the performance of EM waves transmission. Additionally, one of the most significant branches within the field of electromagnetic functions is radar cross section (RCS) reduction. The most basic way to reduce the RCS of a radome is to use the exterior design to reflect out-of-band EM waves away from the direction of the incoming waves [20], [21]. However, with the development of anti-stealth technology and the improvement of radar detection capabilities, relying solely on exterior design is no longer sufficient for radome to meet the survival conditions in complex EM environments. Later, researchers developed a method to reduce the RCS of the radome by loading absorbing materials [22], [23], [24], [25], while this method would add extra weight, hindering its application in the aircraft field. In addition, the absorbing materials loaded would seriously affect the transmission performance of the original radome, resulting in the inability to solve the compatibility of high transmission and out of band stealth through traditional methods. Therefore, there is an urgent need for metasurface designs that combines the functions of enhancing transmission in the wide angle domain within the band and reducing the radar cross-section (RCS) out of the band.

As early as in 2014, Professor Tiejun Cui’s team proposed the concept of coding metasurface, which reduces RCS by using the reflection phase difference between different unit cells to scatter reflected waves in different directions in space [26]. In 2017, they also proposed to encode the metasurface consisting of lossy structures, which further improved the RCS reduction performance of the coding metasurface [27]. With the development of coding metasurfaces, they have special research significance in beam regulation [28], achieving polarization insensitivity [29], and independently controlling the transmitting and receiving channels [30]. On this basis, scholars have gradually realized that, in addition to the control of reflection or radiation characteristics, the coding regulation of transmission waves also holds significant theoretical value and application potential. Later, scholars began to pay attention to the effect of coding on transmitted waves. In 2021, Hongchen Chu’s team proposed a kind of coding metasurface that can realize one-way perspective of human eyes in the visible frequency band based on the principle of reciprocity [31]. In 2022, they demonstrated that the design of metasurfaces based on reciprocity is also applicable to the microwave frequency band [32]. As shown in Figure 1, the multi-layer cascade metasurface is composed of several identical atomic units but with different orientations.

Schematic of this work. The cascading metasurface forms a stable wide-angle-domain electromagnetic window under dual polarization through the synergistic action of the plasma effect of the metal mesh and the Lorentz resonance effect of the metal patch. Its function is further expanded by breaking up the reflected waves through coding, thereby reducing the RCS.

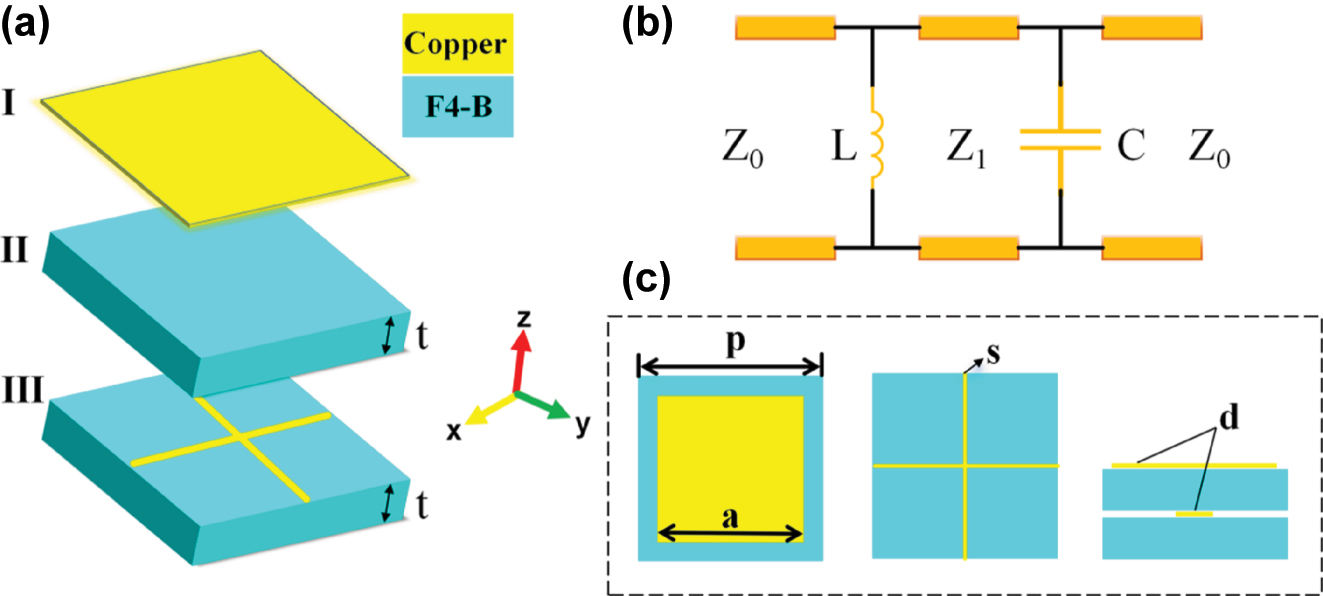

Inspired by the above work, different from the traditional methods that often utilize the changes of metamaterial structure parameters in the transverse dimension to regulate electromagnetic characteristics, we propose an electromagnetic window design scheme based on longitudinally flipped encoded metasurfaces. This scheme can simultaneously achieve the reduction of out-of-band RCS and the wide-angle domain angle transmission performance in band. First, we design the initial cascade metasurface with band-pass performance around 1.6 GHz by equivalent circuit analysis. As shown in Figure 2(a), the cascade metasurface is composed of a layer of square metallic patches, a layer of metallic meshes and two poly tetra fluoro ethylene (PTFE) substrates. This asymmetric structure design results in significant changes in the reflection phase of meta-atom before and after flipping, which makes preparation for subsequent coding processing. Subsequently, based on the design principle of coding metasurface, the meta-atoms with the metallic patch on the lower surface is defined as “low” meta-atoms, the ones with the metallic patch on the upper surface is defined as “up” meta-atoms (flip the “low” meta-atom to get the “up” meta-atom), and 4 same meta-atoms arranged by 2 × 2 arrays are defined as a “0” or “1” lattice. Then we use 010101 and 001011 sequences to encode the initial cascade metasurface. Considering the reflection phases of the two distinct meta-atoms exhibit a certain degree of difference, the reflected waves from the cascade metasurface are dispersed in multiple directions after encoding, thereby reducing the RCS. Owing to the principle of reciprocity, the transmission phase of the two meta-atoms remains identical, ensuring that the transmitted wave from the cascade metasurface remains unchanged after encoding, thereby preserving the initial transmission performance. After a series of simulations in CST Microwave Studio, a set of proof-of-principle prototypes were designed, fabricated and measured. The experimental results are almost identical with the simulation results and they all confirm the correctness of our strategy. This research introduces a novel approach for electromagnetic windows that combines the functions of in-band wide-angle domain transmission enhancement and out-of-band radar cross-section (RCS) reduction, which has significant potential application value in various application scenarios.

The structural parameters of the cascade metasurface meta-atom. (a) The thickness of the substrates t = 4 mm. (b) The equivalent circuit of the cascade metasurface. (c) The period p = 12 mm, the line width of the metallic mesh is s = 0.05 mm, the side length of a square metallic patch a = 11.9 mm, and the thickness d of all metallic structure is 0.02 mm.

2 Theory and design

The initial cascade metasurface comprises a layer of square metallic patches, a layer of metallic mesh and two PTFE substrates. The meta-atom and the relevant structural parameters are shown in Figure 2(a) and (c), where the relative dielectric constant of the substrate is ɛ

r

= 2.65. As shown in Figure 2(b), the cascade metasurface can be equivalent to a parallel LC resonant circuit, in which the gap between the metallic patches can induce the equivalent capacitance, and the metallic mesh forms the equivalent inductance. The free space in the side and two substrates can be equivalent to the resistance, whose impedance is expressed as Z

0 = 377 Ω and

The capacitance value is determined by the periodic size p, the metallic patch size a and the equivalent dielectric constant of the substrate ɛ r . Increasing p and a will increase C. The equivalent inductance L can be expressed as Eq. (2).

The equivalent inductance value is determined by the periodic size p and the line width of the metallic mesh s. Increasing the p and decreasing s will increase L. A certain mutual capacitance exists between the metal meshes and the metal patches. According to the definition of capacitance C = ɛ

0

ɛ

r

S/d, the mutual capacitance C

m

between the metal patches and the metal meshes can be derived, which primarily depends on the overlapping area of the two metallic structures and the distance d between them. Due to the relatively large separation between the metal patches and the metal meshes, the resulting mutual capacitance C

m

is small and can be neglected. Therefore, the overall capacitance of the system can be regarded as solely arising from the mutual capacitance C between the metal patches. According to the parallel resonant circuit

According to Snell’s law [34], [35], [36], [37], as shown in Figure 3(a), the transmission efficiency is maximized when the impedance of air matches that of the cascade metasurface. Here, η

0 and η

1 respectively denote the intrinsic wave impedances of air and the cascade metasurface. θ

i

and θ

t

respectively represent the incident angle and the refraction angle; μ

0 and ɛ

0 represent the magnetic permeability and dielectric constant of air, while μ

1 and ɛ

1, respectively, denote the effective magnetic permeability and effective dielectric constant of the cascade metasurface.

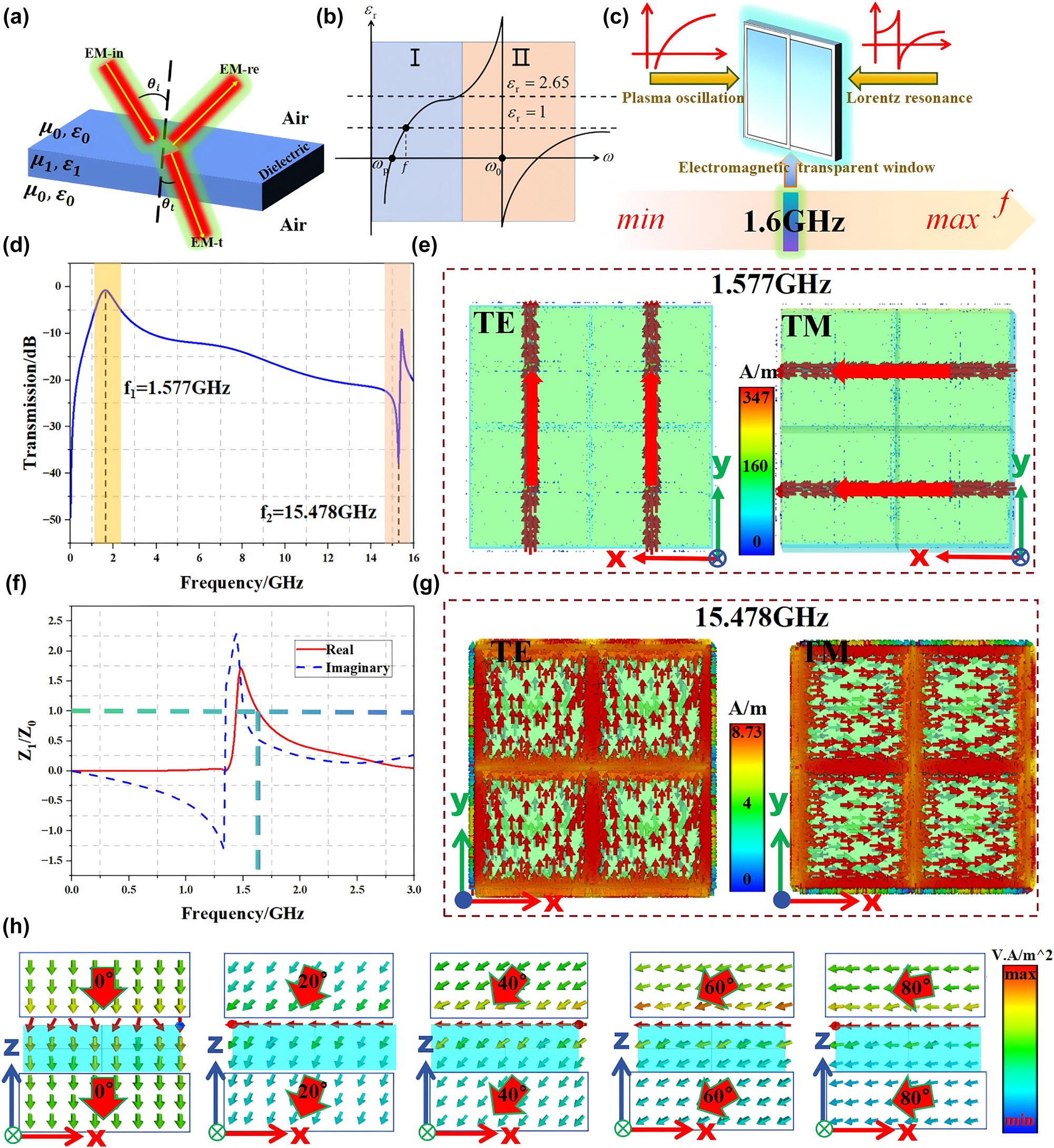

Physical background and the principle of antireflection spectroscopy. (a) A schematic diagram illustrating the reflection of EM waves when they enter a dielectric plate from air. (b) The variation of the relative permittivity of the substrate loaded with metal mesh-like lines and metal patch structures with frequency. (c) Schematic diagram of the principle of forming an electromagnetic transparent window. (d) Transmission spectra after loading both the metal mesh-like lines and the metal patch structures simultaneously. (e) Surface current distribution under TE and TM polarization at 1.577 GHz. (f) The real part and the imaginary part of the relative equivalent impedance of the substrate under TE polarization after loading metal mesh lines and metal patch structures at an incident angle of 0°. (g) Surface current distribution under TE and TM polarization at 15.478 GHz. (h) The energy flow within the substrate when TE or TM polarized waves are incident at five different angles.

When TE or TM waves are incident on the cascade metasurface, the localized electrons within the metal mesh lines will generate plasma oscillations, and the equivalent dielectric constant of the cascade metasurface will change. The metal mesh-like line causes the equivalent dielectric constant of the substrate to vary with frequency due to plasma resonance is shown in Figure 3(b).I, which conforms to the Drude model. The equivalent dielectric constant of the substrate no longer remains constant but increases nonlinearly with frequency (from less than 0 to the dielectric constant of the bare substrate itself). The trend of the equivalent dielectric constant of the substrate with respect to frequency caused by Lorentz resonance of the metal patch is shown in Figure 3(b).II, which conforms to the Lorentz model. Among them, the so-called plasma frequency ω p represents that the dielectric constant of the substrate as a whole is exactly equal to zero, and the dispersion characteristics of the substrate will change. As shown in Figure 3(c), when metal mesh and metal patch are added to the substrate, the resonant frequency of the metal patch and the plasma frequency of the metal mesh are jointly regulated and acted on the parameter f through the coupling effect, so that the wave transmission window is stabilized at f.

In order to further analyze the aforementioned coupling effects, we separately analyzed the interaction between the metal meshes and the metal patches. When metal meshes are introduced onto the metal patches, the plasma oscillation induced by the meshes follows the Drude model [38], which reduces the effective permittivity of the substrate at the high-frequency end. As a result, the wavelength corresponding to the Lorentz resonance decreases, leading to a shift of the resonant frequency toward higher values. Similarly, when metal patches are added to the metal meshes, the Lorentz resonance effect introduced by the patches conforms to the Lorentz model [38], which increases the effective permittivity of the substrate at the low-frequency end. This causes an increase in the wavelength corresponding to the plasma frequency, thereby shifting the plasma frequency toward lower values. As the plasma frequency shifts downward, the frequency f corresponding to impedance matching also shifts accordingly to a lower frequency. Therefore, it can be concluded that the transmission window observed at frequency f results from the combined action of both the metal meshes and the metal patches.

At this time, the overall equivalent dielectric constant of the cascaded metasurface is exactly one. As shown in Figure 3(f), at this time, a good impedance matching is formed between the cascade metasurface and the air on 1.6 GHz. According to formula (3)–(7), we can obtain:

As shown in Figure 3(d), a transmission channel is formed not only at 1.6 GHz but also at 15.47 GHz, although with weaker transmission strength. This channel corresponds to the Lorentz resonance mode of the metasurface unit structure. Unlike the dominant mode responsible for transmission at 1.57 GHz, the Lorentz resonance mode typically exhibits more complex field distributions and distinct characteristics. The operating frequency of the Lorentz resonance mode (15.47 GHz) is much higher than that of the mode at 1.57 GHz. According to the skin effect theory, the skin depth

To further analyze the frequency selection principle of cascade metasurface, as shown in Figure 3(d), we selected two frequency points of 1.577 GHz and 15.478 GHz as the monitoring objects. The surface currents of TE and TM polarized waves at the incident angle of 0° were observed in CST. According to Figure 3(e) and (g), it can be seen that there are strong surface currents on the metal mesh-like line structure at low frequencies, while the currents on the metal patch is relatively weak. This indicates that at the low-frequency end, the plasma resonance effect of the metal mesh-like line structure plays a role in regulating the frequency point f. At the high-frequency region, the metal patch has a relatively strong surface current, while the current on the metal meshes are relatively weak. This indicates that at the high-frequency end, the Lorenz resonance effect of the metal patch plays a role in regulating the frequency point f. Therefore, metal meshes and metal patch structures can be utilized to enhance the impedance matching of cascade metasurface at the frequency f, thereby enabling the realization of the transmission characteristics at this frequency point. Furthermore, we continue to analyze the energy flow distribution of the upper and lower surfaces of cascade metasurface at frequency f based on the 0° reference point. Measurements are taken every 20°. As can be seen from Figure 3(h), when the EM waves passes through the cascade metasurface, there is no obvious deflection on the upper and lower surfaces of the cascade metasurface. Moreover, it passes through the substrate along a smooth path (the refractive angle is almost equal to the incident angle), and the energy flow magnitudes on both sides of the cascade metasurface are basically the same. This indicates that the impedance matching between the cascade metasurface and the air is good, and the EM waves transmission rate is high.

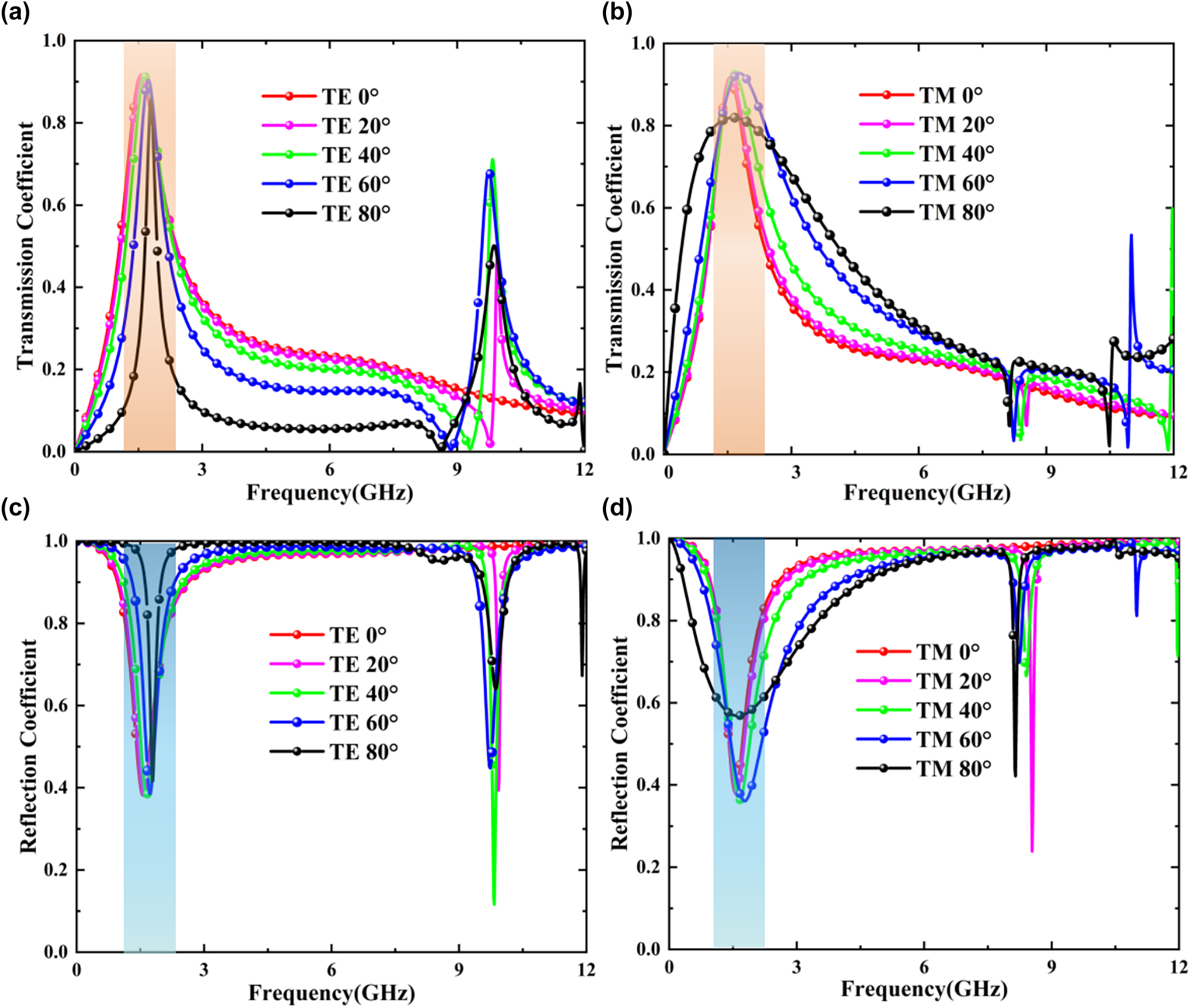

According to this rule, relevant dimension parameters are adjusted, and the “unit cell” boundary and frequency domain solver of CST microwave studio is used for simulation calculation, and the results obtained are shown in Figure 4. It can be observed that the initial cascade metasurface exhibits excellent band-pass performance for both TE- and TM-polarized electromagnetic (EM) waves around 1.6 GHz. However, nearly all EM waves outside the passband are reflected. Therefore, although the transmission performance of cascade metasurface is very good, it has a large out-of-band RCS.

Transmission and reflection spectra under dual polarization. (a) and (b) The transmission coefficient of the EM waves under TE-polarization and TM-polarization. (c) and (d) The reflection coefficient of the EM waves under TE-and TM-polarization.

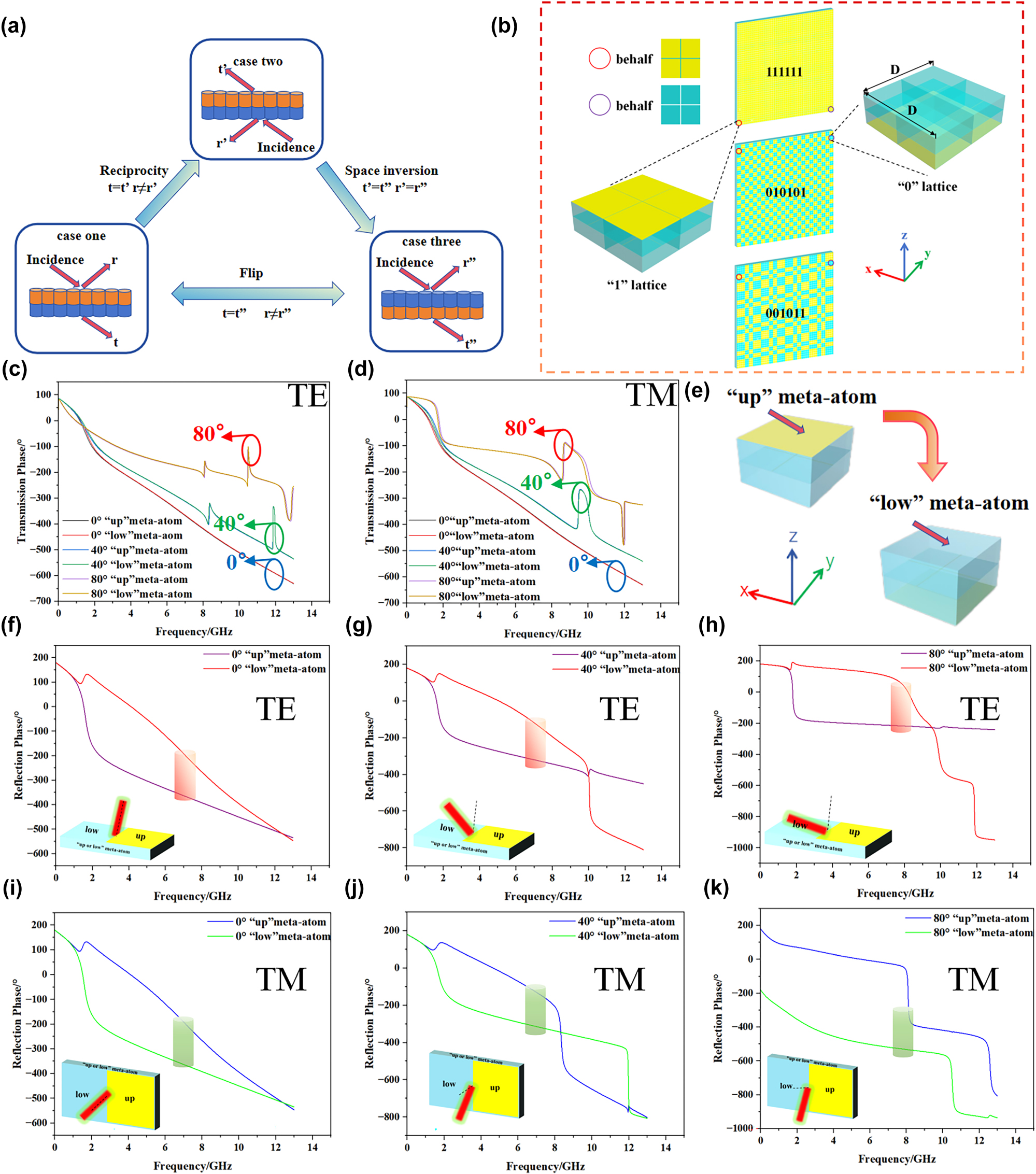

With a high-performing initial cascade metasurface in place, we commence to flip coding it. As shown in Figure 5(e), we define “low” meta-atom for the metallic patch on the lower surface of the substrate and “up” meta-atom for the metallic patch on the upper surface of the substrate, the “up” meta-atom can be regarded as the “low” meta-atom flipped 180°. Then, in CST, we incident TE-polarized waves along the negative direction of z-axis, and simulated the cascade metasurface formed by the two-dimensional periodic extension of two different meta-atoms. As shown in Figure 5, it is evident that the reflection phase of the “low” meta-atom and the “up” meta-atom differs due to the distinct positions of the metallic patch. However, the transmission phase of both meta-atoms remains identical.

The underlying mechanism of the reciprocity theorem and its specific application to the subscript form of coding. (a) The reciprocity principle and space-inversion invariance jointly guarantee the unchanged transmission under the flip operation for the same incidence while the reflections can be distinctly different, r and t respectively represent the reflection waves and the transmission waves. (b) The “0” lattice and “1” lattice with sides of length D = 24 mm, and the flip coded cascade metasurface with the periodic sequence of 111111, 010101 and 001011. (c) and (d) Transmission phases of TE/TM polarization at 0°, 40° and 80°. (e) The two types of meta-atoms are related to each other by the space-inversion (flip) operation. (f), (g) and (h) Reflection phases of TE polarization at 0°, 40° and 80°. (i), (j) and (k) Reflection phases of TM polarization at 0°, 40° and 80°.

As shown in Figure 5(a) case one, when an EM wave is incident from the top onto a plate composed of up-down asymmetric elements, Snell’s law dictates that, in the absence of energy loss, a portion of the wave is reflected while the remainder is transmitted. When the electromagnetic wave is incident from the bottom of the plate at the same angle (as shown in Figure 5(a) case two, the phase of the reflected wave changes, whereas the phase of the transmitted wave remains unchanged). Consequently, r ≠ r′, while t = t′. Similarly, as shown in Figure 5(a) case three, if the wave remains incident from the top of the plate but the plate is rotated by 180°, the phase of the reflected wave will exhibit the same change, whereas the phase of the transmitted wave will remain unchanged. Consequently, r ≠ r″, and t = t″. When the spatial configuration and direction are reversed, as shown in Figure 5(c) and (d), the transmission phases of the three characteristic angles remain basically unchanged under TE and TM polarization, which provides a basis for maintaining the stability of the transmission effect by using the reciprocity theorem in the subsequent process. As shown in Figure 5(f)–(h), under TE polarization, the reflection phases of the three characteristic angles differ by 180° near 7 GHz. As shown in Figure 5(i)–(k), under TM polarization, the reflection phases of the three characteristic angles also differ by 180° near 7 GHz. This is for the subsequent dispersion of the reflected waves using the differences in the reflection phases. Moreover, the variation laws governing the reflection phase and the incident phase differ. This phenomenon is consistent with the reciprocity principle [39], [40], which forms the theoretical foundation for our subsequent encoding of cascade metasurface.

The main function of coding metasurface is to disperse the reflected EM wave to different directions in space to achieve RCS reduction, requiring a key element which must have a reflection phase difference [26], [27]. As shown in Figure 5(f)–(k), we have verified that the reflection phase of “low” meta-atom and “up” meta-atom has a difference, and the difference is exactly 180° near 7 GHz, which fully meets the requirements of coding metasurface. And as shown in Figure 5(a), we also verify that the reciprocity principle is true for the initial cascade metasurface, which means that ideally if we code the initial cascade metasurface with “low” meta-atom and “up” meta-atom as the encoding elements, we can not only break the reflected wave but also keep the transmitted wave unchanged. It not only maintains the transmission performance of cascade metasurface but also reduces its RCS.

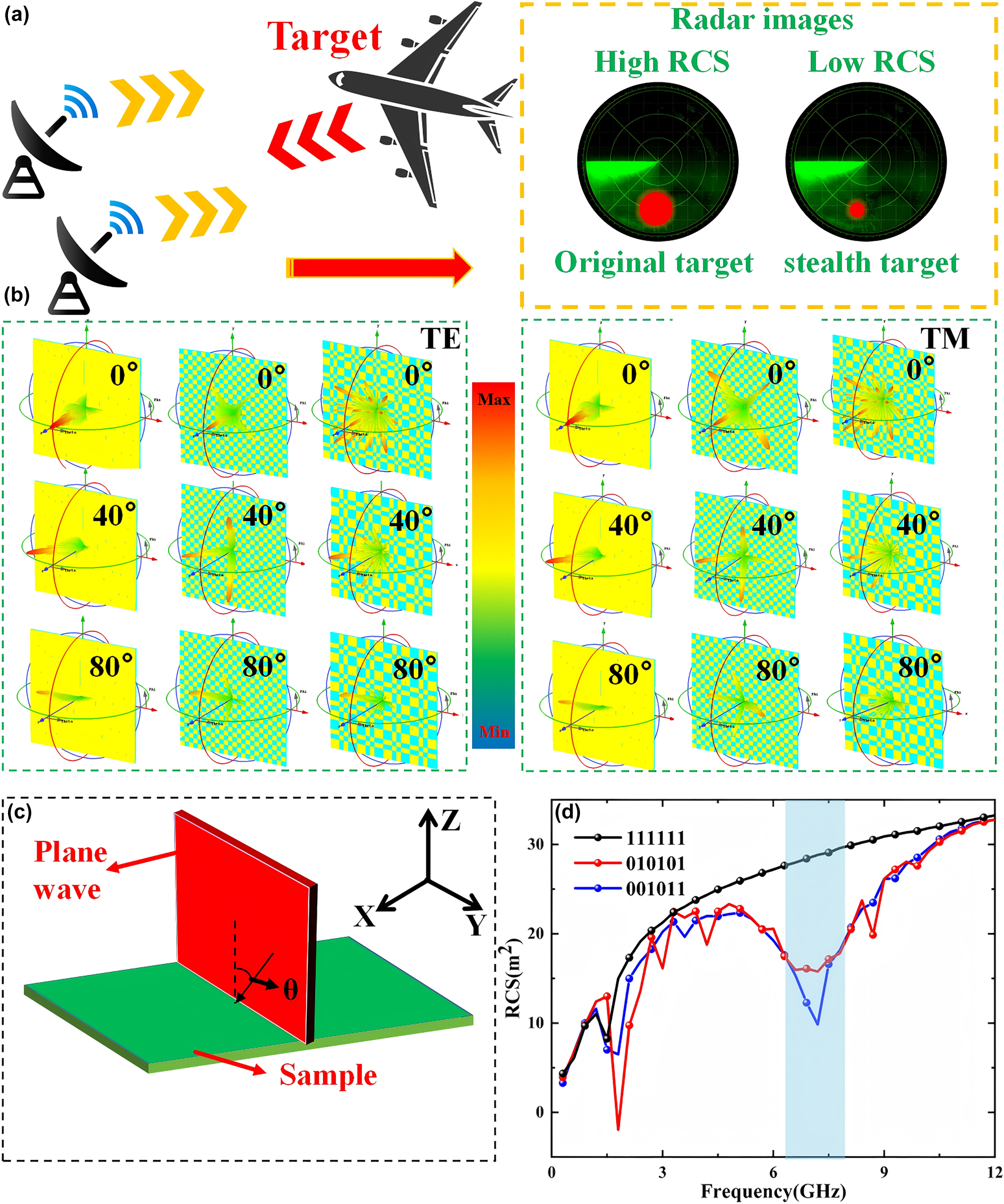

As shown in Figure 5(b), according to the design criteria of coding metasurface [41], we arrange 4 “low” meta-atoms in a 2 × 2 array to form a “0” lattice and arrange 4 “up” meta-atom in the same way to form a “1” lattice. The side length of the lattices D = 24 mm. We then arrange the designed lattice in particular periodic sequences to form the flip coding cascade metasurface. Following the above, we now discuss the strengths of the different encoding approaches in Figure 5(b). The 010101 and 001011 coding sequences produce significantly different scattering patterns. We define “0” to represent a phase of 0° and “1” to represent a phase of 180° after longitudinal flipping. Due to the 180° phase difference between the two differently arranged unit types, destructive interference occurs across the surface structure, thereby weakening the reflected wave. From the perspective of the law of energy conservation, the cancelled energy is not lost but is redistributed, forming weaker, more dispersed scattering lobes. As shown in Figure 7(b) for the 111111 coding sequence, all units have identical phases. Consequently, no mutual interference occurs among the reflected waves, resulting in a far-field pattern where energy is highly concentrated in the direction of the incident electromagnetic wave. In contrast, the 010101 coding sequence shown in Figure 7(b), while still a periodically arranged structure, introduces a 180° phase-flipped unit adjacent to each original unit. The far-field simulation reveals the presence of relatively strong sidelobes in its radiation pattern, while a significant reduction in RCS is achieved in the specular direction. Regarding the 001011 sequence in Figure 7(b), this coding sequence is introduced to design an unconventional, aperiodic arrangement that incorporates randomness. By designing such a sequence for effective comparison with the two aforementioned types, its far-field pattern demonstrates that the scattered energy is dispersed into various directions in space, achieving a distribution of scattering energy that is as flat and uniform as possible.

3 Simulation results

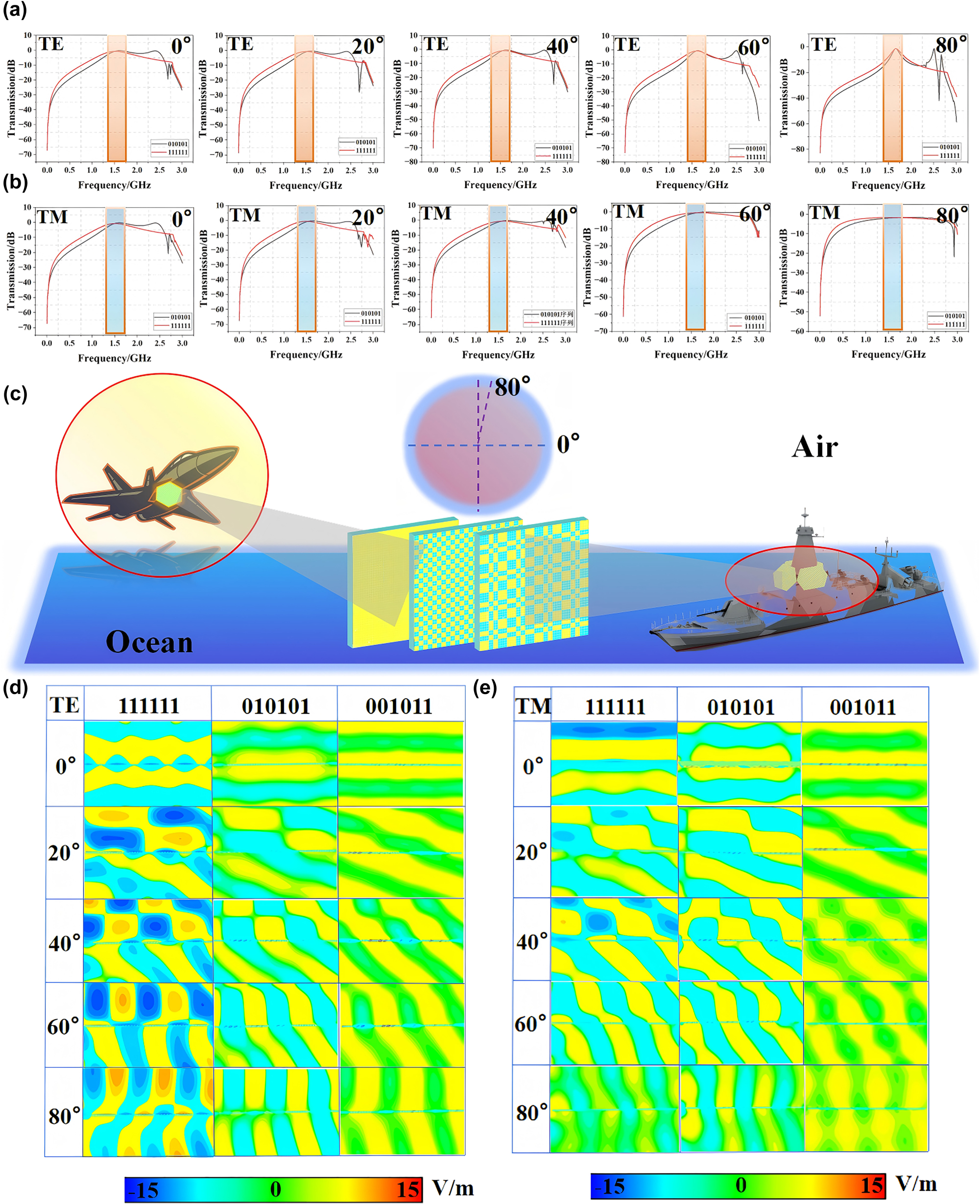

In CST, we test the transmittance of two sequences 111111 and 010101 under different polarizations through frequency domain solver, and set the incidence angles to 0°, 20°, 40°, 60° and 80°, so as to simulate the actual situation of various incidence angles. The simulation test diagram is shown in Figure 6(a) and (b). We use −1 dB as the standard to divide the bandwidth, and it can be seen from the figure that the best transmission effect is concentrated around 1.6 GHz. In order to further observe the transmission effect of 001011 sequence at 1.6 GHz, we used time domain solver to conduct electric field simulation test, and compared the results with the two sequences 111111 and 010101. The results are shown in Figure 6(d) and (e). It can be seen from the figure that EM waves can pass almost without loss through the metasurface of the three coding sequences. According to the above simulation results, it can be seen that when electromagnetic waves are incident at a large incident angle under TM polarization, their high selectivity is somewhat lacking. The reason for this is that under TM polarization, the Brewster effect exists, which causes the reflected waves to disappear, thus achieving complete transmission.

Verification and test results of the anti-reflection principle of three sequences at all angles under dual polarization. (a) and (b) Under TE or TM polarization, the transmittance of 111111 and 010101 sequences corresponds to the incidence angle of 0°–80°. (c) Schematic diagram of the incident angle of the flat antenna radome on the simulated ship or aircraft. (d) and (e) Electric field distribution of three sequences 111111, 010101 and 001011 under TE or TM polarization.

In CST, we modeled the flip coding cascade metasurface with the periodic sequences of 111111, 010101 and 001011, all of the dimensions of 576 mm × 576 mm (the initial cascade metasurface can be regarded as the flip coding cascade metasurface with the periodic sequence of 111111). We configured the plane wave in the direction of electric field always along the y-axis normally incident on the established cascade metasurface along the negative direction of the z-axis, and the boundary conditions in the three directions were set as “open add space”. Subsequently, as shown in Figure 7(c), the time-domain solver was employed to solve the problem, and the RCS values of the three cascade metasurface structures were obtained, as shown in Figure 7(d). It can be clearly seen that compared with the initial cascade metasurface, the RCS of the coding cascade metasurface around 7 GHz is significantly reduced, but the bandwidth is relatively narrow. To expand the bandwidth, we can introduce absorbing materials on the basis of the above structure, thereby achieving a reduction in broadband RCS. On the basis of maintaining the reduction of broadband RCS, it is more meaningful to achieve a transmission band with stable angles. Although this article has achieved in-band transmission enhancement and out-of-band RCS reduction efficiency, there is still some room for improvement. While ensuring the stability of the transmission channel angle, achieving a wider RCS reduction has a better application space for practical effects. Therefore, we have concluded that on the basis of this article, appropriate absorbing materials can be added to achieve a wider RCS reduction without affecting the efficient transmission within the band.

The effect diagram of RCS reduction and the far-field simulation test diagram. (a) Schematic representation of the interaction between simulated radar-emitted EM waves and the target. (b) Far-field simulation results for the three sequences 1111110, 10101, and 001011 under TE or TM polarization with incident angles ranging from 0° to 80°. (c) Far-field measurement models for the three sequence samples were conducted using plane wave illumination. (d) Linear plots depicting the RCS characterization of the three sequences at a 0-degree incidence angle.

In order to further verify our design scheme and confirm that the transmitted wave of cascade metasurface has not changed after coding, we respectively monitored the far-field energy distribution of cascade metasurface at 7 GHz, and the results are shown in Figure 7(b). It can be clearly seen that compared with the initial cascade metasurface, the reflected waves of the flipped coding cascade metasurface are dispersed in different directions.

4 Experiment

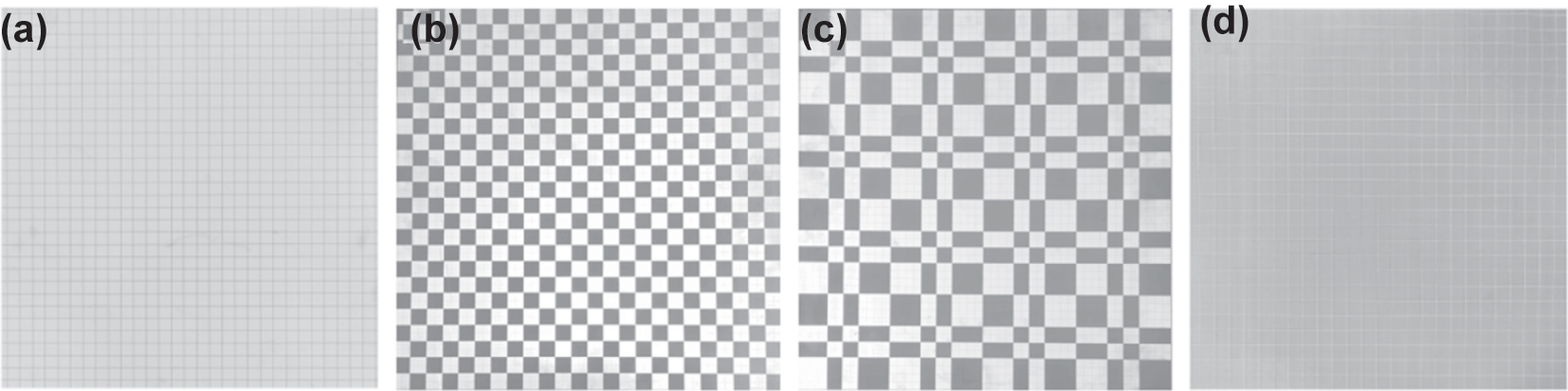

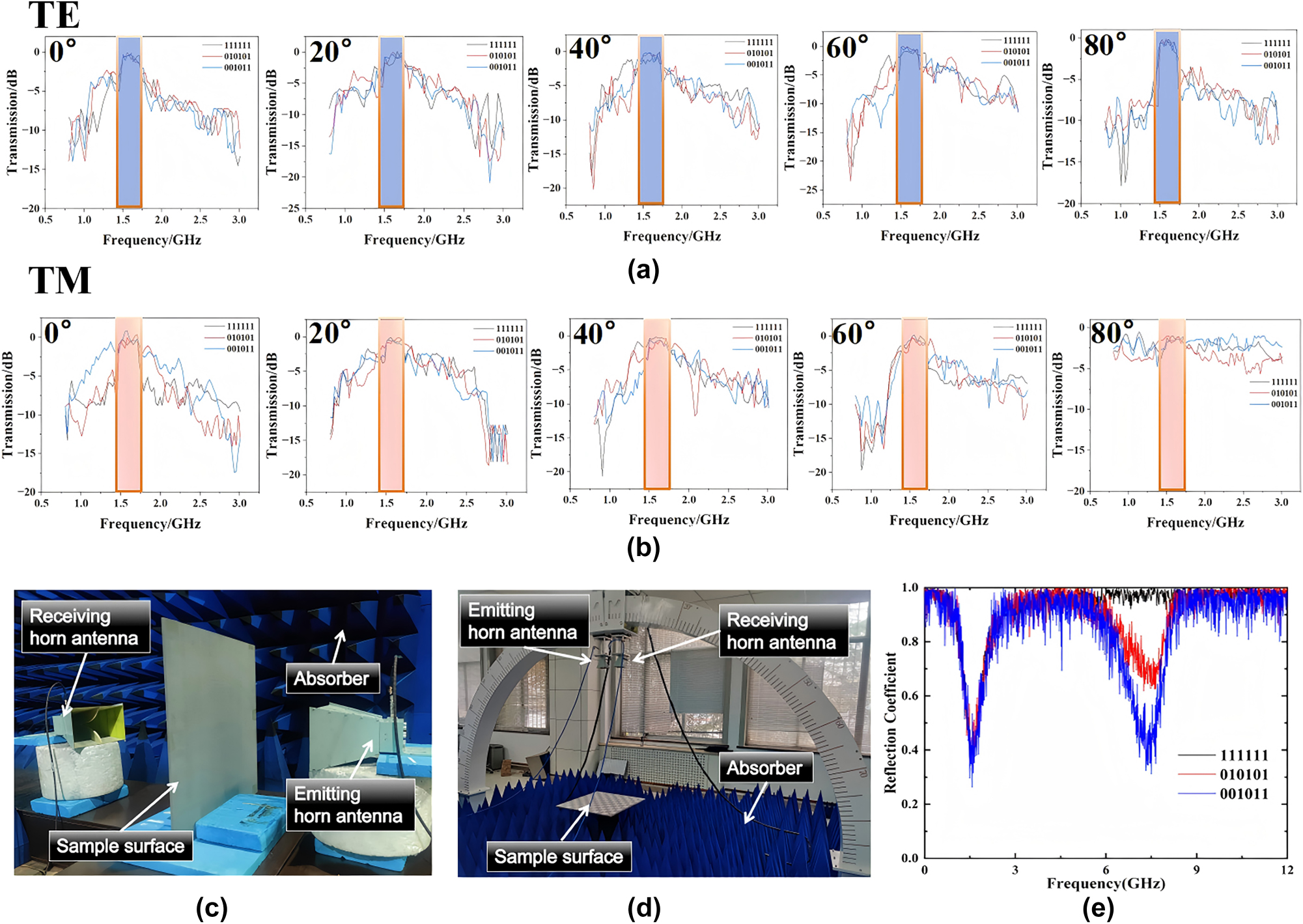

To verify our design scheme we fabricated a set of prototypes and measured them. As shown in Figure 8 we fabricated 4 mm thick PTFE plates with size of 576 mm × 576 mm and etched metallic meshes or metallic patch arranged according to different coding sequences on its surface with printed circuit technology (PCT). The structural parameters of the patch and meshes were the same as those in Figure 2(a). As shown in Figure 8, two plates were assembled to reconstruct the designed cascade metasurface structures. The transmission and reflection characteristics of the prototype were measured separately by using horn antennas within an electromagnetic anechoic chamber and an arched frame.

Experimental test substrates for three sequences. (a), (b) and (c) Metallic patch arranged by sequences of 111111, 010101, and 001011 are etched on one side of the PTEF plate. (d) Etch the metallic mesh on the other side of the PTEF plate.

To ensure the accuracy of the experimental test, each time we measure the wave transmission test at different angles under different polarizations, we will perform calibration and normalization tests to avoid accidental errors. Secondly, for each measurement result, we conducted multiple repeated experiments. Moreover, our testing environment is carried out in a microwave anechoic chamber. The absorbing sponge in the anechoic chamber can absorb most of the clutter signals, effectively preventing these signals from affecting the experimental tests. Measured results are shown in Figure 9. Compared with 111111 sequence, flip coding cascade metasurfaces with 010101 or 001011 sequence has significantly lower reflection but basically the same transmission. Since the physical significance of RCS and reflection is basically the same at 0° incident angle, the decrease of reflection can indirectly indicate the decrease of RCS. Our measured results deviate from the ideal situation mainly because there are some errors in the fabricating and there is also a small amount of clutter in the dark room. This causes a certain degree of jitters in the test results, but the above-mentioned jitters noise can be effectively filtered by adding a time domain gate. Even so, the measured results still prove the correctness and performance of our scheme.

Schematic diagram of the transmission and RCS experimental test results of the three sequences under dual polarization. (a) Under TE polarization, 0°–80° 111111, 010101 and 001011 transmission lines of three coding sequences. (b) Under TM polarization, 0°–80° 111111, 010101 and 001011 transmission lines of three coding sequences. (c) Measured the transmission of the prototype in an EM dark room. (d) Measured the reflection of the prototype in an arched frame. (e) The reflection coefficient of coding cascade metasurfaces with periodic sequences of 111111, 010101, and 001011.

5 Conclusions

This paper presents a design scheme for an electromagnetic transparent window based on the flipping of coding element surfaces. This approach enables the simultaneous achievement of stable wave transmission across wide angles within the band and the reduction of radar cross-section (RCS) out of the band. First, the initial band-pass cascade element surface is designed. Subsequently, the cascade element surface is flipped and encoded by using periodic sequences of “010101” and “001011”. Owing to the protection provided by the reciprocity principle, the reflected wave is scattered while the transmitted wave remains unaffected. This not only effectively reduces the radar cross-section (RCS) but also preserves the original transmission performance. Thus, the simultaneous resolution of compatibility issues between electromagnetic communication and electromagnetic stealth has been achieved through the longitudinal freedom design of a single structure. To validate our design scheme, we conducted simulation experiments by using CST to obtain the RCS of cascade metasurfaces with different coding sequences and monitored their far-field energy distribution at 7 GHz. A series of proof-of-principle prototypes were designed, fabricated, and measured to validate this scheme. The measured results are in agreement with the simulation results, thereby validating both the correctness and performance of this scheme. This work introduces a novel approach to designing metasurface with low RCS, which holds significant. This work paves a new route to multi-functional EM windows and may find wide applications in new-generation communication, radar systems and others.

Funding source: Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: No.2024JC-YBQN-0617

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: Nos. 62401617

Award Identifier / Grant number: U24A20224

Funding source: Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. GZC20233577

Award Identifier / Grant number: No.2023M744291

-

Research funding: National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62401617); The Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program under Grant (No. 2024JC-YBQN-0617); The Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China under Grant (No. 2023M744291); The National Funded Postdoctoral Researcher Program under Grant (No. GZC20233577); Joint fund for regional innovation and development of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20224).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. H-YL: investigation, data curation, writing - original draft. T-FL: methodology, formal analysis, validation. J-FW(*): conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing - review & editing. Y-XJ(*): conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, writing - review & editing. R-CZ: software, visualization. X-LL: resources, validation. Z-HZ: formal analysis, investigation. MZ: investigation, data curation. S-BQ: supervision, writing - review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] S. P. Huber, R. W. E. van de Kruijs, A. E. Yakshin, E. Zoethout, K. J. Boller, and F. Bijkerk, “Subwavelength single layer absorption resonance antireflection coatings,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 490–497, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.000490.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] H. Liu et al.., “Strong interference-based ultrathin conductive anti-reflection coating on metal substrates for optoelectronic,” NPG Asia Mater., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 309–317, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-018-0011-z.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] H. Selj et al.., “Reduction of optical losses in colored solar cells with multilayer antireflection coatings,” Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell., vol. 95, no. 9, pp. 2576–2582, 2011.10.1016/j.solmat.2011.03.005Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Y. Matsuoka, P. Semtsiv, M. Peters seven, and W. Ted Masselink, “Broadband multilayer antireflection coating for quantum cascade laser facets,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, no. 19, pp. 4723–4726, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.004723.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] C. Du et al.., “Radiofrequency transparent uniaxial dual‐polarized metasurface with ultrawide brewster angle stability,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 19, no. 16, p. 2500190, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202500190.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] P. Li et al.., “Controlling the TE-TM splitting of topological photonic interface states by precise incident angle adjustment,” Commun. Phys., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 201, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01695-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] J. Tang et al.., “Omnidirectional absorber for dual polarizations based on generalized brewster effect in highly dissipative metasurface,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., pp. 1–1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2025.3604957.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] S. Hui et al.., “Noninvasive inset-integrated meta-atom for achieving single-layer metasurface simultaneously with coded microwave reflectivity and digitalized infrared emissivity,” Nanophotonics, vol. 13, no. 17, pp. 3113–3122, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2024-0098.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] S. Hui et al.., “Microwave-infrared-compatibility enhancement of metasurfaces by decoupling Lorentz resonance of meta-atoms,” Photon. Res., vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 1800–1809, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.555317.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] S. Hui et al.., “Multi-physics metasurface with reduced characteristic scales simultaneously for microwave, infrared, and acoustic compatibility,” Photon. Res., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 263–273, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.536697.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Y. Li et al.., “Wide-angle transmission enhancement of metamaterial-doped fiber-reinforced polymers,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 76042–76048, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2019.2920901.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Y. He and G. V. Eleftheriades, “A thin double-mesh metamaterial radome for wide-angle and broadband applications at millimeter-wave frequencies,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 2176–2185, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2019.2951491.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] F. Yang et al.., “Antireflection and wavefront manipulation with cascaded metasurfaces,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 14, no. 6, p. 064044, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.14.064044.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] N. Bayat-Makou and G. V. Eleftheriades, “Omega bianisotropic huygens’ metamaterial lens for matching improvement of W-Band substrate integrated E-Plane horn,” in 2021 15th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–4.10.23919/EuCAP51087.2021.9410910Suche in Google Scholar

[15] T. Cai et al.., “High-efficiency and full-space manipulation of electromagnetic wave fronts with metasurfaces,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 034033, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.8.034033.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] G. Jiang et al.., “Abnormal beam steering with kirigami reconfigurable metasurfaces,” Nat. Commun., vol. 16, p. 1660, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56211-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] H. Guo et al.., “Flat optical transparent window: mechanism and realization based on metasurfaces,” J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., vol. 51, no. 7, p. 074001, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aaa451.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Y. Chen, W. Yu, Y. Du, W. Wang, L. Liu, and G. Q. Luo, “Dual-polarization wideband bandpass absorptive frequency selective structure with high angular stability,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., pp. 1–5, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2025.3570019.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Z. Wang et al.., “Four-mode switchable frequency-selective surface featuring wideband and angular stability,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 3009–3013, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2024.3418195.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] J. Yang et al.., “Reducing out-of-band radar cross-section of metasurface-based radome composites via beam-scattering mechanism,” Mater. Des., vol. 244, p. 113150, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.113150.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Q. Jiang, H. Fu, J. Duan, L. Zheng, J. Jiang, and L. Wu, “Achieving RCS reduction via scattering and absorption mechanisms using a chessboard structured composite,” Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 275, p. 111312, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111312.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] C. Wang et al.., “The EM property of chemically reduced graphene oxide and its application as microwave absorbing material,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 98, no. 7, p. 072906, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3555436.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] T. Liu, X. Xie, Y. Pang, and S. Kobayashi, “Co/C nanoparticles with low graphitization degree: a high performance microwave-absorbing material,” J. Mater. Chem. C, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 1727–1735, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5tc03874j.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Y. Zheng et al.., “Research and application of kapok fiber as an absorbing material: a mini review,” J. Environ. Sci., vol. 27, pp. 21–32, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2014.09.026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Y. F. Fu, J. D. Ji, Y. J. Wang, F. K. Zhou, C. Wang, and P. Chen, “Broadband radar cross section reduction binary metasurface with a high-efficiency intraband transmission window,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 878–882, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2022.3149930.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] T. J. Cui, M. Q. Qi, W. Xiang, J. Zhao, and Q. Cheng, “Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials,” Light: Sci. Appl., vol. 3, no. 10, p. e218, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2014.99.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] L. Li et al.., “EM reprogrammable coding-metasurface holograms,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2017.10.1038/s41467-017-00164-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] S. Taravati, “Three-dimensional nonreciprocal Beamsteering-Amplifying coding metasurface,” in 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and INC/USNC‐URSI Radio Science Meeting (AP-S/INC-USNC-URSI), IEEE, 2024.10.1109/AP-S/INC-USNC-URSI52054.2024.10687221Suche in Google Scholar

[29] W. Li et al.., “Magneto-optical chiral metasurfaces for achieving polarization-independent nonreciprocal transmission,” Sci. Adv., vol. 10, no. 31, p. eadm7458, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adm7458.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] H. Li et al.., “Independent manipulations of transmitting and receiving channels by nonreciprocal programmable metasurface,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 5234–5244, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c14945.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] H. Chu et al.., “Diffuse reflection and reciprocity-protected transmission via a random-flip metasurface,” Sci. Adv., vol. 7, no. 37, p. eabj0935, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj0935.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] H. Chu et al.., “Flip-component metasurfaces for camouflaged meta-domes,” Opt. Express, vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 17321–17331, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.456655.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] O. Luukkonen et al.., “Simple and accurate analytical model of planar grids and high-impedance surfaces comprising metal strips or patches,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 56, no. 6, pp. 1624–1632, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2008.923327.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] L. Piechocki and W. Li, “De Broglie Wave’s Snell’s law, Fresnel equations, and Brewster’s angle,” Micro Nanostruct., vol. 199, p. 208075, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micrna.2025.208075.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] P. González, L. Mariano, and J. L. F. Martínez, “Generalization of Snell’s Law for the propagation of acoustic waves in elliptically anisotropic media,” Aims Math., vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 14997–15007, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3934/math. 2024726.10.3934/math.2024726Suche in Google Scholar

[36] J. Stigloher et al.., “Snell’s law for spin waves,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 117, no. 3, p. 37204, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.117.037204.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] S. Kumar, P. C. Pal, and S. Majhi, “Reflection and transmission of plane SH-Waves through an anisotropic magnetoelastic layer sandwiched between two semi-infinite inhomogeneous viscoelastic half-spaces,” Pure Appl. Geophys., vol. 172, no. 10, pp. 2621–2634, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-015-1048-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] I. Ben Soltane, F. Dierick, B. Stout, and N. Bonod, “Generalized Drude–Lorentz model complying with the singularity expansion method,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 12, no. 12, p. 2400093, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202400093.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] J. Wang, Q. Ji, M. Kadic, and C. Wang, “Engineering static non-reciprocity in mechanical metamaterials,” Thin-Walled Struct., vol. 205, p. 112373, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112373.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] C. A. Dirdal et al.., “Reversal asymmetry of reciprocal metasurface enables ultra‐compact varifocal reflective lens,” Laser Photon. Rev., p. e01196, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202501196.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] L. Su et al.., “Design and on-chip measurement of CMOS infrared frequency-selective-surface absorbers for thermoelectric energy harvesting,” in Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference 2011, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011, pp. 461–464.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry