Abstract

Recent studies on nonlocal metasurfaces have shown possibilities of optical image processing, such as edge detection, without the need for Fourier optics and have significantly reduced the form factor. However, the analog edge detection using nonlocal metasurfaces still requires the use of multiple lenses to image the edge-enhanced results, and the edge-detected image generally suffers from image distortion originating from the free space propagation before reaching the detector otherwise. In this work, we propose a nonlocal metasurface that not only enhances the edge features but also delivers them to the far-field with considerably less distortion by combining the conventional edge detection metasurface with a uniaxial slab that has a transfer function of the free space with a negative propagation length. This space expander cancels out the diffraction of the edge-enhanced image that occurs during the free space propagation, the thickness of which reaches several orders of magnitude larger than the slab thickness. This nonlocal metasurface for the far-field edge detection will open a path towards compact optical systems for high-quality analog image processing.

1 Introduction

Recent advances in nanotechnology have opened an era of flat optics, in which light can be tailored with extreme degrees of freedom while transmitting through thin planar structures [1]. Whereas the thickness of such structures is comparable to or even less than the wavelength, flat optics has successfully reproduced many optical phenomena and applications that have been otherwise achieved through propagation of bulk media, the thickness of which reaches several tens or hundreds of wavelengths [2], [3], [4]. The center of this reproduction is a metasurface, an array of subwavelength-scale antennas that are designed to selectively control various light properties such as amplitude [5], phase [6], [7], [8], polarization [9], [10], and temporal/spatial frequencies [11], [12]. Designs of such metasurfaces mostly rely on a local approximation that the transmission and reflection are fully determined by the position [13].

Recently, it has been pointed out that nonlocality, i.e., nonlocal manipulation of light, can expand the coverage of flat optics and further compactify optical systems [14], [15]. In this regime, transmitted or reflected light at a given point is not solely determined by the transmission/reflection and incident light at the point [16], [17], [18], but is affected by the angular transmission/reflection profiles of the entire metasurface mediated by, for example, laterally guided waves [19], [20], [21], [22]. As such, metasurfaces with strong nonlocality enable wave vector (k) space operations without the need for Fourier optics components [23], [24], [25], [26]. One representative example is analog optical edge detection [27], which features the high k components, i.e., the edges, of a given image using the k-dependent amplitude transfer function (ATF). Its linear or quadratic relation with respect to k provides spatial differentiation (∇) or Laplace (∇2) operations, respectively, in a purely analog manner in the speed of light [11], [28], [29]. The ATF that has a gradually decreasing amplitude as k decreases and vanishes as k → 0 eliminates the zero spatial frequency components and enhances the edges [28], [30], [31], [32]. With local metasurfaces [33], photonic crystals [29], and the spin Hall effect of light (SHEL) [34], [35], nonlocal metasurfaces open a new route toward compact, analog edge detection.

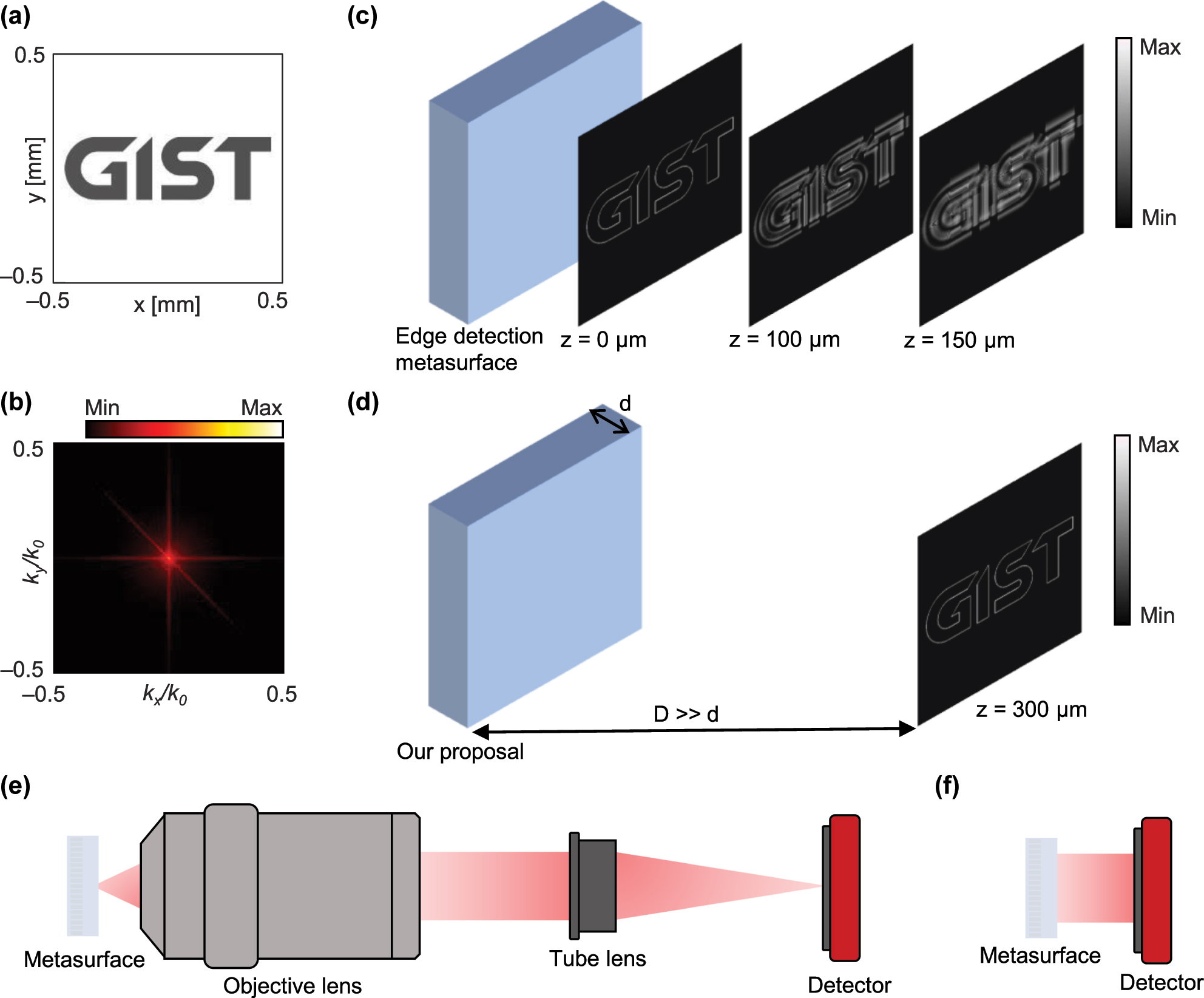

One problem with this edge detection using the nonlocal metasurface, however, is that the edge-enhanced image is generally formed right after the metasurface and is rapidly distorted during propagation because of its high k nature (Figure 1(a)–(c)). This requires the use of another imaging system comprising multiple lenses and free space between them (Figure 1(e)). Considering that the key merit of nonlocal metasurfaces for edge detection is the removal of traditional 4f systems [26], the necessity of an additional set of lenses is contradictory and undermines the advantage of metasurfaces, the compactness. However, a nonlocal metasurface that provides edge detection in the far-field has yet been reported. Here, we propose a nonlocal metasurface for the far-field edge detection by combining an edge detector and space expander, the reverse concept of recently proposed space compressors or spaceplates (Figure 1(d)) [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. The metasurface consists of an array of dielectric cylinders on a uniaxial slab with a negative refractive index. The ATF of the cylinder array has a quadratic amplitude profile for p polarization and blocks the transmission of s polarization and thus accentuates the edge features under unpolarized illumination. Meanwhile, the slab supports a quadratically increasing phase profile, which corresponds to the ATF phase of the free space with a negative propagation length that may reach several orders of magnitude thicker than the slab thickness. This unique optical property allows the edge-enhanced image to be delivered to the camera in the far-field without requiring additional optical setups such as infinity-corrected systems (Figure 1(f)). A lens may be added in front of the metasurface when required to alleviate these issues. We numerically demonstrate that the edge-enhanced image generated by our metasurface has a clear image with significantly less distortion in the far-field, whereas the edge-enhanced image of the conventional edge detection metasurface suffers from severe distortion during propagation. This edge detection in the far-field assisted by nonlocal metasurfaces will relieve the burden of placing optical components closely to the edge-detected images and compactify the analog image processing.

Schematic of edge detection and importance of far-field edge detection. (a) Input image and (b) its k space distribution. (c) Evolution of simulated edge-detected images during propagation using the conventional edge detection metasurface and (d) our metasurface designed for the far-field edge detection. Comparison between the optical setups of (e) conventional and (f) our metasurface for edge detection. All intensity distributions are shown on a logarithmic color scale.

2 Result and discussion

2.1 Space expander

Our metasurface for the far-field edge detection consists of two parts: an edge detector and a space expander. The main role of each part is to feature edges of a given image and to cancel out the free space propagation so that the edge-detected image can be delivered to the far-field without distortion, respectively. We discuss the space expander first in this section and introduce the edge detector in the preceding section.

A uniaxial slab, refractive index tensor of which is expressed as diag(n

⊥, n

⊥, n

‖) can operate as a two-dimensional space expander under p-polarized incidence if Re(n

⊥) < 0 and Im(n

⊥) > 0. Here, n

⊥ = n

x

= n

y

(n

‖ = n

z

) is the refractive index along the direction perpendicular (parallel) to the optic axis oriented along the z-axis (Figure 2(a)). The incident plane is the zx plane. We examine the ATF of a slab that has a finite thickness d and is embedded in a background medium with the index n

b

. We first consider the transmission of the slab with the following parameters: n

b

= 1.45, n

⊥ = −20 + 0.2i, n

‖ = 0.269, wavelength λ = 756 nm, and d = 1 µm. The results are obtained analytically by solving Maxwell equations at the boundaries and are confirmed by a full-wave simulation conducted using commercial software, COMSOL Multiphysics. The ATF of the slab has weak oscillating amplitude that originates from the thickness comparable to the wavelength (Figure 2(b)) and a quadratic phase profile with positive gradient (Figure 2(c)). It is opposed to the negative phase gradient of the general isotropic medium with a positive index. More specifically, we examine the optical path length of the slab qualitatively by fitting the phase with a curve −k

‖

D + ϕ

c

(Figure 2(c)). Here,

Space expander to deliver the edge-detected image to the far-field. (a) Uniaxial slab that has a negative refractive index along directions perpendicular to the wave propagation as a space expander. (b) Transmission amplitude and (c) phase under p-polarized incidence when n b = 1.45, n ⊥ = −20 + 0.2i, n ‖ = 0.269, λ = 756 nm, and d = 1 µm. (d) The expanded length D for various Re(n ⊥) and Re(n ‖) when Im(n ⊥) = 0.2. (e) Averaged transmission amplitude |t p | at 0 ≤ k ⊥/k 0 ≤ 0.6n ‖ for various Re(n ⊥) and Im(n ⊥) when n ‖ = 0.269. (f) D and averaged |t p | for various Re(n ⊥) when Im(n ⊥) = 0.2 and n ‖ = 0.269. (g) D and |t p | for various d when n ⊥ = −20 + 0.2i and n ‖ = 0.269. |t p | is plotted on a logarithmic scale, and the range between its maximum and minimum values is shaded.

The space expansion is also expected for an isotropic medium with a negative refractive index, for instance, for an isotropic material with an index of n ⊥. However, D in our uniaxial slab is a few orders of magnitude larger than that of the isotropic medium for the following reason. In a uniaxial medium, the wave vector in the slab along the propagation direction follows

where

where t

1 and r

1 are transmission and reflection coefficients from the superstrate to the slab, respectively, and t

2 and r

2 are transmission and reflection coefficients from the slab to the substrate, respectively. Eq. (1) indicates that below the cutoff frequency k

cutoff = k

0|n

‖|, k

s

has a negative real and a positive imaginary part, which induces a negative phase velocity and amplitude attenuation, respectively. As such,

This phase profile with negative propagation length is also achievable if the medium has a positive index with gain in the xy plane, that is, Re(n

⊥) > 0 and Im(n

⊥) < 0. Now k

s

in this gain slab is equal and opposite to k

s

in the lossy, negative index slab. The negative imaginary part of k

s

results in an amplitude of

To investigate the effect of refractive indices on space expansion, we examine D and the transmission amplitude |t p | averaged at 0 ≤ k ⊥ ≤ Rk cutoff, where R is chosen as 0.6, by varying n ⊥ and n ‖ (Figure 2(d) and (e)). Note that in all our work, the curve fitting is performed at 0 ≤ k ⊥ ≤ Rk cutoff because while the phase of t p has a positive gradient below the cutoff, its shape deviates from the quadratic characteristic at high k ⊥. Figure 2(d) demonstrates that a wide range of D can be reached, from a few micrometers to millimeters, by adjusting the real parts of the indices. Considering that the thickness of the slab is only a micrometer, the space expansion effect can be on several orders of magnitude. In particular, D increases as both Re(n ⊥) and Re(n ‖) decrease (Figure 2(d)). This agrees well with our previous observation that the gradient of k s with respect to β 2 approximately determines D. Indeed, Eq. (1) implies that the magnitude of the gradient can be magnified by increasing the absolute value of n ⊥ and by reducing n ‖. This can be explained qualitatively; from the curve-fitting equation, one can deduce that D is around

which shows a nice agreement with the calculated results. The corresponding results are provided in Supplementary Material Section S1. Figure 2(d) only shows for 0.15 < n ‖ < 0.5 for better visualization, but D keeps increasing as n ‖ approaches zero. While reducing n ‖ to an infinitesimal value significantly enhances D even to a meter scale (for example, D = 1 m when n ⊥ = −20 + 0.2i and n ‖ = 4.6 × 10−3), it simultaneously reduces k cutoff and limits this space expansion capability in a small angular regime.

Imaginary part, on the other hand, has less impact on D, but mainly affects |t p | (Figure 2(e)). It is consistent with our knowledge that a large imaginary part induces optical losses and thus reduces the total transmission. In addition, as the absolute value of Re(n ⊥) increases, |t p | decreases because the impedance mismatch becomes severe. For better understanding, D and |t p | for various Re(n ⊥) when Im(n ⊥) = 0.2 and n ‖ = 0.269 are shown in Figure 2(f). As Re(n ⊥) decreases, D increases linearly but |t p | also decreases, degrading the entire efficiency. Lastly, D and |t p | for various d are shown in Figure 2(g). As d increases, D increases linearly following the fitting equation D = 300.1d − 0.2 µm. This linear relation agrees well with Eq. (3) and indicates that a thicker free space can be canceled out by increasing the slab thickness at the expense of reduced transmittance.

While only a one-dimensional profile of ATF is shown in Figure 2(b) and (c), the slab is a rotational-symmetric ATF profile for its uniaxial nature (see Supplementary Material Section S2 for the two-dimensional ATF). This in-plane isotropy results in a two-dimensional, isotropic space expansion of the input image after propagation through D. Furthermore, since the sign of n ‖ has no effect on t p with the zero imaginary part (Im(n ‖) = 0), the space expansion is still achieved when Re(n ‖) < 0, showing a symmetric feature. This indicates that the only requirement of the space expander is to make the sign of the real and imaginary parts of n ⊥ opposite, allowing a wide range of indices along the direction of the optical axis. Previously reported metamaterials that exhibit a negative refractive index or support negative refraction may satisfy this requirement and thus operate as a space expander. For example, the fishnet metamaterial, a well-known negative refractive index metamaterial [42], shows the ATF phase with a positive gradient in the negative refraction regime (see Supplementary Material Section S3). This realistic negative index metamaterial can provide an alternative that replaces the uniaxial slab and enables space expansion. While the value of D of the metamaterial is on the order of its thickness and wavelength, this is due to a lack of optimization for space expansion, not because of an intrinsic limitation; D can be further increased by tailoring its optical response. In addition, note that our space expander is studied only for p-polarized incidence because it will be combined with an edge detector working for p polarization while suppressing the s polarized components in the following section. This uniaxial slab for the space expander is applicable not only to edge detection but can be combined with other optical elements or systems to cancel out the diffraction during free space propagation.

2.2 Combination of the space expander and edge detector

The requirements for the edge detection and space expansions are quadratic amplitude and phase profiles, respectively, which can be satisfied independently without affecting each other. Thus, by combining our space expander with previously reported edge detector designs, the far-field edge detection can be realized. We use the metasurface design reported in ref. [11] as the edge detector after minor modifications (Figure 3(a)). The geometric parameters are given as: periodicity p = 376 nm, height h = 280 nm, radius r = 96 nm. The unit cell is a silicon cylinder embedded in the background medium in a square lattice. The refractive index of the silicon and the background medium are given as 3.74 and 1.45, respectively. The transmission is calculated semi-analytically using a lab-built rigorous coupled-wave analysis code and is also confirmed by the full-wave simulation. This metasurface has a quadratic amplitude profile at low k, approximately |k

⊥/k

0| < 0.2, under p-polarized incidence and has a negligible transmission under s-polarized incidence, i.e.,

Metasurface design. (a) A metasurface designed for the near-field edge detection and (b) its amplitude and phase. The geometric parameters are given as: periodicity p = 376 nm, height h = 280 nm, radius r = 96 nm. (c) Our metasurface for the far-field edge detection and (d) its amplitude and phase under p polarization obtained analytically by assuming no coupling (black) and numerically (red). The phase is set to zero at k = 0 for better comparison.

To realize the far-field edge detection, the uniaxial slab that operates as a space expander is inserted below the cylinder array (Figure 3(c)). Transmission of this composite structure under p-polarized incidence is obtained using full-wave simulation. To alleviate the high computational cost originating from the large absolute value of the indices, different refractive indices are used: n ⊥ = −5 + 0.2i, n ‖ = 0.5. Other parameters are given as the same. The ATF has the amplitude that vanishes at k → 0 and oscillates at higher k until it reaches the cutoff (Figure 3(d), red). Below this cutoff frequency, the phase has a positive gradient, the unique feature of the uniaxial slab. The curve fitting of this phase profile shows that D = 24.76 µm.

The cylinder is separated from the slab by a distance of λ/2 to avoid coupling between the slab and the cylinder. If the coupling is indeed absent, the ATF of the whole structure is equal to the pointwise multiplication of the ATF of the cylinder array and that of the uniaxial slab in the k space, provided that the diffraction through the spacing is negligible. The analytic results under the coupling-free assumption (Figure 3(d), black) show nice agreement with that of the realistic structure (Figure 3(d), red). In addition, D obtained from the analytic ATF is 17 µm.

2.3 Comparison between conventional edge detection and our approach

To demonstrate the advantages of far-field edge detection, the evolution of edge-enhanced images generated by our metasurface during propagation is examined and compared with those generated by the conventional edge detection metasurface (Figure 4). For this calculation, we consider unpolarized incidence containing both p and s polarizations. All parameters are given as in Figure 2(b) and (c), and the corresponding D is 300 µm. Note that the analytic two-dimensional ATF is used for the computation (see Figure 3(d) for the validity of this analytic approach). The ATF of this combined structure shows four-fold rotational symmetry with quadratically increasing amplitude and phase profiles until the cutoff frequency for the p polarization and negligible amplitude for the s polarization (Supplementary Material Section S2).

Edge-detected images during propagation. Intensity of beams transmitted through (a) the edge detection metasurface (Figure 3(a)) and (b) our metasurface (Figure 3(c)) at z = 0 µm (top), z = 150 µm (middle), z = 300 µm (bottom). Inset in (a) shows the input image. One-dimensional intensity profiles of the edge-detected images using (c) edge detection metasurface and (d) our metasurface along the cyan lines at y = 0. The insets in (c) and (d) show magnified views of the central 10 µm region.

The conventional metasurface for edge detection provides a clear, edge-enhanced image immediately after the metasurface, i.e., when the propagation distance (z) is zero (Figure 4(a), top). The edge is composed of two lines (see inset of Figure 4(a), top), which corresponds to the second-order spatial differentiation of the original input, because of the quadratic amplitude profile (Figure 3(b)). However, the distance between these two line components increases during the propagation (Figure 4(a), middle and bottom), and the overall edge detection quality is degraded in the far-field.

In contrast, the metasurface consisting of the space expander and edge detector that is designed to deliver the edge-enhanced image to the far-field around z = 300 µm exhibits blurred images at z = 0 µm and z = 150 µm (Figure 4(b), top and middle) but provides clear edge features at the target distance (Figure 4(b), bottom). For better visualization, the cross-sectional profiles at y = 0 (Figure 4(a) and (b), cyan lines) at each image are shown in Figure 4(c) and (d). Slight degradation of the edge-detected image at z = 300 µm (Figure 4(b), bottom) is observed in comparison to the edge-detected image using conventional edge detection metasurface before propagation (Figure 4(a), top) because of the non-constant amplitude, the discrepancy between the ATF phase and its fitting curve, and the nonquadratic phase profile above the cutoff frequency (see Supplementary Material Section S6 for details). Nonetheless, these results confirm that the metasurface consisting of the space expander and edge detector successfully features the edge components and delivers them to the far-field with significantly less distortion. The imaging results at different propagation distances and different slab parameters can be found in Supplementary Material Sections S4 and S5, respectively. Finally, because both the space expander and the edge detector operate in two dimensions, far-field edge detection is enabled in all directions in the xy plane.

3 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have proposed a nonlocal metasurface composed of an edge detector and a space expander to project the edge-enhanced image to the far-field that reaches several orders of wavelengths. We discuss the principle of the uniaxial slab that operates as the space expander and demonstrate that the slab provides the space expansion effect by adjusting the refractive indices. In contrast to the rapid distortion of the edge-enhanced images generated by conventional edge detection metasurfaces during propagation, our metasurface for the far-field edge detection suppresses the image distortion to the target distance. The optical edge detection in the far-field realized by our metasurface abolishes the use of multiple lenses to deliver the edge-enhanced images to a detector and realizes a true compact, lensless analog image processing.

The far-field edge detection shown in our work is limited to unpolarized incidence because of the polarization dependent properties of the space expander and edge detector. The design of a metasurface that supports the edge detection and space expansion for both p and s polarizations will enable the edge detection under arbitrary polarization and broaden the applicability. The imaging setup with our metasurface does not require these additional lenses, but this may limit the magnification at the detector. Another limitation that should be solved in future studies is transmission efficiency. While the current metasurface exhibits relatively low transmittance due to the combined effects of edge detection and space expansion, searching for more efficient approaches would be promising. Potential future work will focus on enhancing transmittance and broadening the functionality, including polarization-insensitive operation.

Funding source: National Research Foundation of Korea

Award Identifier / Grant number: RS-2022-NR072263

Award Identifier / Grant number: RS-2025-00517462

Funding source: Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: Future-Leading Specialized Research Project grant

Funding source: Ministry of Science and ICT, South Korea

Award Identifier / Grant number: GIST InnoCORE KH0830

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant (RS-2022-NR072263) and the Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant (RS-2025-00517462) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Korean government and by the Future-Leading Specialized Research Project grant funded by the GIST in 2025. This work was also supported by the InnoCORE program of the Ministry of Science and ICT (GIST InnoCORE KH0830).

-

Author contributions: DL conducted the numerical simulations and drafted the manuscript. HLP conducted the negative-index metamaterial simulations. MK proposed the concept and edited the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] D. Lin, P. Fan, E. Hasman, and M. L. Brongersma, “Dielectric gradient metasurface optical elements,” Science, vol. 345, no. 6194, pp. 298–302, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1253213.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] S. Wang, et al.., “A broadband achromatic metalens in the visible,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 227–232, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-017-0052-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] W. T. Chen, et al.., “A broadband achromatic metalens for focusing and imaging in the visible,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 220–226, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-017-0034-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] R. J. Lin, et al.., “Achromatic metalens array for full-colour light-field imaging,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 227–231, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0347-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] X. Ni, A. V. Kildishev, and V. M. Shalaev, “Metasurface holograms for visible light,” Nat. Commun., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 2807, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3807.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] H. Liang, et al.., “Ultrahigh numerical aperture metalens at visible wavelengths,” Nano Lett., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 4460–4466, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01570.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Y. F. Yu, A. Y. Zhu, R. Paniagua-Domínguez, Y. H. Fu, B. Luk’yanchuk, and A. I. Kuznetsov, “High-transmission dielectric metasurface with 2π phase control at visible wavelengths,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 412–418, 2015.10.1002/lpor.201500041Suche in Google Scholar

[8] R. Paniagua-Dominguez, et al.., “A metalens with a near-unity numerical aperture,” Nano Lett., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 2124–2132, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00368.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] E. Arbabi, S. M. Kamali, A. Arbabi, and A. Faraon, “Full-Stokes imaging polarimetry using dielectric metasurfaces,” ACS Photonics, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 3132–3140, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00362.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] A. Arbabi, Y. Horie, M. Bagheri, and A. Faraon, “Dielectric metasurfaces for complete control of phase and polarization with subwavelength spatial resolution and high transmission,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 937–943, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.186.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Y. Zhou, H. Zheng, I. I. Kravchenko, and J. Valentine, “Flat optics for image differentiation,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 316–323, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-0591-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] G. Li, S. Zhang, and T. Zentgraf, “Nonlinear photonic metasurfaces,” Nat. Rev. Mater., vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 1–14, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2017.10.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] W. T. Chen, A. Y. Zhu, and F. Capasso, “Flat optics with dispersion-engineered metasurfaces,” Nat. Rev. Mater., vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 604–620, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-020-0203-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Y. Chen, R. Fleury, P. Seppecher, G. Hu, and M. Wegener, “Nonlocal metamaterials and metasurfaces,” Nat. Rev. Phys., vol. 7, pp. 299–312, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-025-00829-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] F. Monticone, et al.., “Nonlocality in photonic materials and metamaterials: roadmap,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 1544–1709, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.559374.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] N. Yu and F. Capasso, “Flat optics with designer metasurfaces,” Nat. Mater., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 139–150, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3839.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] A. Overvig and A. Alù, “Diffractive nonlocal metasurfaces,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 16, no. 8, 2022, Art. no. 2100633.10.1002/lpor.202100633Suche in Google Scholar

[18] K. Shastri and F. Monticone, “Nonlocal flat optics,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 36–47, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01098-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] S. Wang and R. Magnusson, “Theory and applications of guided-mode resonance filters,” Appl. Opt., vol. 32, no. 14, pp. 2606–2613, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.32.002606.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] A. Hessel and A. A. Oliner, “A new theory of wood’s anomalies on optical gratings,” Appl. Opt., vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 1275–1297, 1965. https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.4.001275.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] G. Quaranta, G. Basset, O. J. Martin, and B. Gallinet, “Recent advances in resonant waveguide gratings,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 12, no. 9, 2018, Art. no. 1800017. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201800017.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] L. Huang, et al.., “Ultrahigh-Q guided mode resonances in an all-dielectric metasurface,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 3433, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39227-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] J. W. Goodman and M. E. Cox, “Introduction to Fourier optics,” Phys. Today, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 97–101, 1969. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3035549.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] A. Silva, F. Monticone, G. Castaldi, V. Galdi, A. Alù, and N. Engheta, “Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials,” Science, vol. 343, no. 6167, pp. 160–163, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242818.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] F. Zangeneh-Nejad, D. L. Sounas, A. Alù, and R. Fleury, “Analogue computing with metamaterials,” Nat. Rev. Mater., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 207–225, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-020-00243-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] L. Wesemann, T. J. Davis, and A. Roberts, “Meta-optical and thin film devices for all-optical information processing,” Appl. Phys. Rev., vol. 8, no. 3, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0048758.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] E. N. Leith, “The evolution of information optics,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron., vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 1297–1304, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1109/2944.902181.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] H. Kwon, D. Sounas, A. Cordaro, A. Polman, and A. Alù, “Nonlocal metasurfaces for optical signal processing,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 121, no. 17, 2018, Art. no. 173004. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.121.173004.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] C. Guo, M. Xiao, M. Minkov, Y. Shi, and S. Fan, “Photonic crystal slab Laplace operator for image differentiation,” Optica, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 251–256, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.5.000251.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] M. Cotrufo, A. Arora, S. Singh, and A. Alù, “Dispersion engineered metasurfaces for broadband, high-NA, high-efficiency, dual-polarization analog image processing,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 7078, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42921-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] C. Jin and Y. Yang, “Transmissive nonlocal multilayer thin film optical filter for image differentiation,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 13, pp. 3519–3525, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0313.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] S. K. Chamoli, et al.., “Nonlocal flat optics for size-selective image processing and denoising,” Nat. Commun., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 4473, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59765-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] T. Badloe, et al.., “Bright-field and edge-enhanced imaging using an electrically tunable dual-mode metalens,” ACS Nano, vol. 17, no. 15, pp. 14678–14685, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c02471.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Y. Kim, et al.., “Topological vortex transition induced by spin Hall effect of light for tunable humidity sensing and imaging,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 19, no. e00581, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202500581.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] P. Tang, et al.., “Spin Hall effect of light in a Dichroic polarizer for multifunctional edge detection,” ACS Photonics, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 4170–4176, 2024.10.1021/acsphotonics.4c01058Suche in Google Scholar

[36] C. Guo, H. Wang, and S. Fan, “Squeeze free space with nonlocal flat optics,” Optica, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 1133–1138, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.392978.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] O. Reshef, et al.., “An optic to replace space and its application towards ultra-thin imaging systems,” Nat. Commun., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 3512, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23358-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] O. Y. Long, C. Guo, W. Jin, and S. Fan, “Polarization-independent isotropic nonlocal metasurfaces with wavelength-controlled functionality,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 17, no. 2, 2022, Art. no. 024029. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.17.024029.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] K. Shastri, O. Reshef, R. W. Boyd, J. S. Lundeen, and F. Monticone, “To what extent can space be compressed? Bandwidth limits of spaceplates,” Optica, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 738–745, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.455680.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] A. Chen and F. Monticone, “Dielectric nonlocal metasurfaces for fully solid-state ultrathin optical systems,” ACS Photonics, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 1439–1447, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.1c00189.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] M. Mrnka, et al.., “Space squeezing optics: performance limits and implementation at microwave frequencies,” APL Photonics, vol. 7, no. 7, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0095735.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] M. I. Aslam and D. Ö. Güney, “Dual-band, double-negative, polarization-independent metamaterial for the visible spectrum,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B, vol. 29, no. 10, pp. 2839–2847, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1364/josab.29.002839.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0373).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Light-driven micro/nanobots

- Tunable BIC metamaterials with Dirac semimetals

- Large-scale silicon photonics switches for AI/ML interconnections based on a 300-mm CMOS pilot line

- Perspective

- Density-functional tight binding meets Maxwell: unraveling the mysteries of (strong) light–matter coupling efficiently

- Letters

- Broadband on-chip spectral sensing via directly integrated narrowband plasmonic filters for computational multispectral imaging

- Sub-100 nm manipulation of blue light over a large field of view using Si nanolens array

- Tunable bound states in the continuum through hybridization of 1D and 2D metasurfaces

- Integrated array of coupled exciton–polariton condensates

- Disentangling the absorption lineshape of methylene blue for nanocavity strong coupling

- Research Articles

- Demonstration of multiple-wavelength-band photonic integrated circuits using a silicon and silicon nitride 2.5D integration method

- Inverse-designed gyrotropic scatterers for non-reciprocal analog computing

- Highly sensitive broadband photodetector based on PtSe2 photothermal effect and fiber harmonic Vernier effect

- Online training and pruning of multi-wavelength photonic neural networks

- Robust transport of high-speed data in a topological valley Hall insulator

- Engineering super- and sub-radiant hybrid plasmons in a tunable graphene frame-heptamer metasurface

- Near-unity fueling light into a single plasmonic nanocavity

- Polarization-dependent gain characterization in x-cut LNOI erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers

- Intramodal stimulated Brillouin scattering in suspended AlN waveguides

- Single-shot Stokes polarimetry of plasmon-coupled single-molecule fluorescence

- Metastructure-enabled scalable multiple mode-order converters: conceptual design and demonstration in direct-access add/drop multiplexing systems

- High-sensitivity U-shaped biosensor for rabbit IgG detection based on PDA/AuNPs/PDA sandwich structure

- Deep-learning-based polarization-dependent switching metasurface in dual-band for optical communication

- A nonlocal metasurface for optical edge detection in the far-field

- Coexistence of weak and strong coupling in a photonic molecule through dissipative coupling to a quantum dot

- Mitigate the variation of energy band gap with electric field induced by quantum confinement Stark effect via a gradient quantum system for frequency-stable laser diodes

- Orthogonal canalized polaritons via coupling graphene plasmon and phonon polaritons of hBN metasurface

- Dual-polarization electromagnetic window simultaneously with extreme in-band angle-stability and out-of-band RCS reduction empowered by flip-coding metasurface

- Record-level, exceptionally broadband borophene-based absorber with near-perfect absorption: design and comparison with a graphene-based counterpart

- Generalized non-Hermitian Hamiltonian for guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs

- A 10× continuously zoomable metalens system with super-wide field of view and near-diffraction–limited resolution

- Continuously tunable broadband adiabatic coupler for programmable photonic processors

- Diffraction order-engineered polarization-dependent silicon nano-antennas metagrating for compact subtissue Mueller microscopy

- Lithography-free subwavelength metacoatings for high thermal radiation background camouflage empowered by deep neural network

- Multicolor nanoring arrays with uniform and decoupled scattering for augmented reality displays

- Permittivity-asymmetric qBIC metasurfaces for refractive index sensing

- Theory of dynamical superradiance in organic materials

- Second-harmonic generation in NbOI2-integrated silicon nitride microdisk resonators

- A comprehensive study of plasmonic mode hybridization in gold nanoparticle-over-mirror (NPoM) arrays

- Foundry-enabled wafer-scale characterization and modeling of silicon photonic DWDM links

- Rough Fabry–Perot cavity: a vastly multi-scale numerical problem

- Classification of quantum-spin-hall topological phase in 2D photonic continuous media using electromagnetic parameters

- Light-guided spectral sculpting in chiral azobenzene-doped cholesteric liquid crystals for reconfigurable narrowband unpolarized light sources

- Modelling Purcell enhancement of metasurfaces supporting quasi-bound states in the continuum

- Ultranarrow polaritonic cavities formed by one-dimensional junctions of two-dimensional in-plane heterostructures

- Bridging the scalability gap in van der Waals light guiding with high refractive index MoTe2

- Ultrafast optical modulation of vibrational strong coupling in ReCl(CO)3(2,2-bipyridine)

- Chirality-driven all-optical image differentiation

- Wafer-scale CMOS foundry silicon-on-insulator devices for integrated temporal pulse compression

- Monolithic temperature-insensitive high-Q Ta2O5 microdisk resonator

- Nanogap-enhanced terahertz suppression of superconductivity

- Large-gap cascaded Moiré metasurfaces enabling switchable bright-field and phase-contrast imaging compatible with coherent and incoherent light

- Synergistic enhancement of magneto-optical response in cobalt-based metasurfaces via plasmonic, lattice, and cavity modes

- Scalable unitary computing using time-parallelized photonic lattices

- Diffusion model-based inverse design of photonic crystals for customized refraction

- Wafer-scale integration of photonic integrated circuits and atomic vapor cells

- Optical see-through augmented reality via inverse-designed waveguide couplers

- One-dimensional dielectric grating structure for plasmonic coupling and routing

- MCP-enabled LLM for meta-optics inverse design: leveraging differentiable solver without LLM expertise

- Broadband variable beamsplitter made of a subwavelength-thick metamaterial

- Scaling-dependent tunability of spin-driven photocurrents in magnetic metamaterials

- AI-based analysis algorithm incorporating nanoscale structural variations and measurement-angle misalignment in spectroscopic ellipsometry