Abstract

The asymmetric star polymers are studied by coarse grain simulations. Each polymer chain is represented by number of consecutive soft blobs and additional uncrossability constraints are added to prevent chain crossings. In this work two types of asymmetric star polymers with different backbone lengths are structured. Their dynamical properties are discussed by comparisons with corresponding linear chains, the one covers chain length along with the asymmetric arm through the branch point to one of the symmetric arm, or the backbone chain between two symmetric arm ends, or the largest linear possesses the same molecular weight of the entire star. To reveal the influence of the asymmetric arm length on their relaxation decay times, the autocorrelation function of the vectors from each branching point to corresponding asymmetric arm end are calculated, results are compared with the symmetric star having the same backbone chain.

1 Introduction

Different types of architecture make polymers behave with various physical properties, such as the branched polymers have higher density compared with linear polymers, for the branches often make the chains too difficult to get close enough for having the intermolecular forces work effectively. Polymer chain dynamical and rheological properties corresponding to the topology differences have been found in plenty of experimental (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and theoretical investigations (6, 7, 8, 9). Besides, there are also many simulation works to reveal and predict the properties of polymer systems in different scales (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17).

Star polymers, with one branch point connecting to several linear arms are always of great interests. They can be creatively synthesized in laboratory or largely produced from industry (18,19). There are two main structures in terms of the arm length, symmetric star with all the arms having the equal length or asymmetric star at least contains one arm in different length to others. Having the simplest branch structure, both of the symmetric and asymmetric star polymers have been studied in many works extensively (9, 10, 11, 12,20).

Coarse graining method has been implemented to study the simplest architecture of symmetric three-arm star polymer (21,22). In this work, another member from the simplest architectures of linear or symmetric star polymer is investigated, namely three-arm asymmetric stars in which two of the arms have the same length and the third arm is relatively shorter or longer. One might expect that asymmetric three-arm star can cross over the behaviors between a symmetric star and a linear polymer of the same arm length as the length of the third arm is varied. Therefore the dynamics of asymmetric three-arm stars varying with the arm length is mainly studied.

2 Model and methods

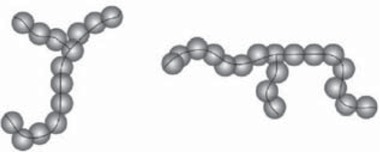

In this study, the TWENTANGLEMENT model has been used, briefly, each of the coarse-grained particle (blob) represents the center of mass of 20 consecutive monomers. Thus an entire 3-arm asymmetric star can be written as B(Bm)(Bn)2, where the first symbol B stands for the branching point, and the two terms (Bm) and (Bn)2, contribute to the description of one asymmetric and two symmetric linear arms. Subscripts m and n denote the number of blobs contained on each arm. In general, the 3-arm asymmetric stars can be built in two kinds of shape, taking B(B7)(B3)2 and B(B3)(B7)2 as examples shown in Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of 3-arm asymmetric star: B(B7)(B3)2 two short arms and one long arm in ‘Y’ shape; or B(B3)(B7)2 one short arm and two long arms in ‘T’ shape.

Because of the coarse-graining, the equation of motion of the position of the blobs can be described by the simple first order Langevin equation, which involves the conservative forces FC derived from the potential of mean force Φ,

as well as the blob fiction ξ and random forces FR with the usual statistical properties,

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem demands the relation between ξ and FR given in Eq. 3 as a condition for thermal equilibrium at the temperature of T = 450 K:

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, and

The potential of mean force can be approximately presented as a sum of three independent parts, ϕb, ϕθ, and ϕnb, with the usual meaning of bonded potential, angular potential and non-bonded or van der Waals potential separately. Using microscopic simulations (23,24), the distribution function between bonded and non-bonded blobs can be determined. Hence, the potential of mean force can be obtained by taking minus kBT times the logarithm of measured distributions of blobs, i.e.

In mesoscopic simulations, since each blob represents a large group of monomers, the interaction between blobs will become so weak that bond crossings may occur. To prevent such unrealistic event, an additional uncrossibility algorithm, called Twentanglement is developed (23). In short, this algorithm modifies the chain dynamics by introducing entanglement constraints on the crossing site of two elastic bonds. Because of the elasticity, the distance Ri,i+1 between two bonded consecutive blobs will be replaced by the path length Li,i+1. Through the path entanglement positions Xp are defined, and thus the path from blob i to blob i+1 can be updated as

with n the blob number and p the number of entanglements. Consequently, the expression of bonded attractive potential is now changed to be the function of path length. The entanglement positions are updated along with the moving of pair blobs and will be fixed at the points with the equilibrium of forces in the system. This is carried out by the minimization of total attractive potential energy for the given configuration Rn of the blobs,

In our algorithm, when an entanglement from one arm slips over a branch point, it is either annihilated, or locates on one of the correct arm of the other two, or gets entangled with both of the other two arms. Usually in the last case, one of the two is chosen randomly to entangle with and the other entanglement is ignored. All simulations were performed in cubic boxes with periodic boundary conditions. The mass density of polyethylene melt was kept constant as ρ = 0.761 g/cm3. All numerical results presented in this paper were obtained with ξ = 8.0 ps−1.

3 Results and discussion

In this work the asymmetric star properties are presented from the comparisons with those linear polymers: one has the same length as the asymmetric linear arm; one backbone between two ends of symmetric arms; one is from the end of asymmetric arm to either end of the symmetric arm; and another long one possesses the same molecular weight of entire star. In Figure 2 the square of end-to-end distance of those linear chains are plotted, and the scaling property is to the power of ~1 along with the increasing of chain molecular mass.

Linear chain end-to-end distance scaling property.

Compared with those linear chains, the properties of asymmetric stars will be discussed mainly from the following aspects. Firstly, in order to understand the influence of the asymmetric arm on the star size and confirm the equilibrium of arm relaxation, the time dependent autocorrelation functions (ACF) for the unit vectors directed from each branch point to the end-point of the star asymmetric arms are calculated

where Rb and Re are the positions of branch point and asymmetric arm end for each configuration of the star polymer chain separately. Moreover, in melt system, the diffusive property is considered as an important physical quantity. It can be qualified by the diffusion coefficient extracted from the mean square displacement:

where Rcmi(t) is the center of mass position of chain i at time t, and the pointy brackets denote an average running through all the times and molecules.

3.1 Y-shaped asymmetric stars

The Y-shaped asymmetric stars have two short symmetric arms and one long asymmetric arm in the length of about two times larger than the short ones. By decreasing the number of blobs on the asymmetric arm, the three arms will have the equal length to form a symmetric star again.

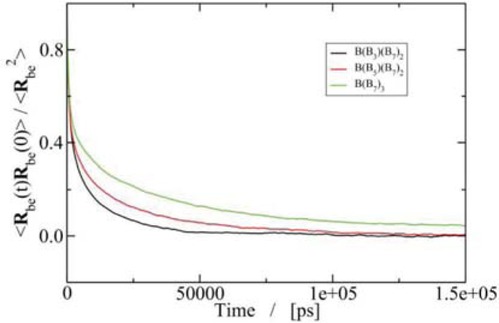

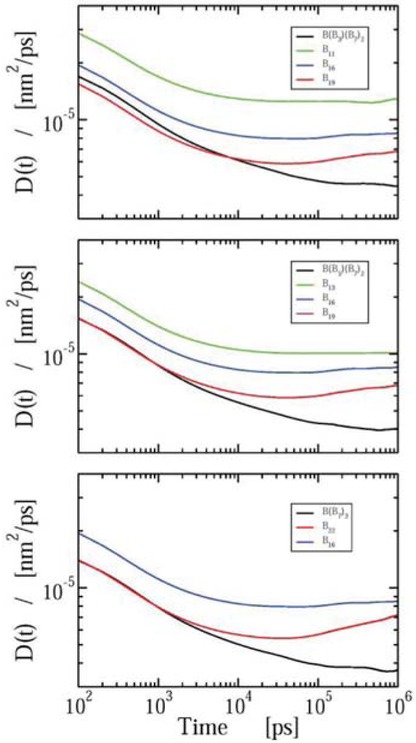

In Figure 3 the autocorrelation function for the vector of asymmetric arms are presented. It is clear from this plot that the decay of the branch-end vectors for the asymmetric star arms becomes slower along with the increasing of arm length. At runtime about 1.5 × 105 ps, all these three curves drop to almost zero which assures that our system is well equilibrated. The similar timescale may be drawn as well as from the extracted diffusion coefficient curves from mean square displacements, shown in Figure 4.

ACF for the unit vectors directed from the branch point to the end-points of the asymmetric arms of Y-shaped asymmetric stars.

Time-dependent diffusion coefficients for symmetric star B(B3)3 and two asymmetric stars with various asymmetric arms, compared with the corresponding linear chains indicated in Figure 2.

Taking the contract with linear chains, the diffusive property of the center of mass of symmetric star B(B3)3 has been found very close to the linear B11, which contains the similar molecular weight, and slower than the backbone chain linear B7 (21), displayed in the top plot of Figure 4. While increasing the asymmetric arm length, the branch point gradually exhibits a topology constraint and starts to slow down the diffusion, shown in the middle and bottom plots in Figure 4. However, due to the limit length of the backbone chain B7, both of diffusion properties of the two asymmetric star B(B5)(B3)2 and B(B7)(B3)2 are more or less following the same trend as the symmetric star, i.e. diffuse similarly as the linear chain B13 which has the same molecular weight.

3.2 T-shaped asymmetric stars

The second type of asymmetric star studied in this work is in T shape, having two long symmetric linear B7 arms as the backbone and one short asymmetric arm B3 with half of the length of the symmetric arm. In this case, a relatively large symmetric star B(B7)3 will be recovered by increasing the length of the short arm.

For the three stars with the same length of backbone chain, it is clear to be seen from Figure 5 that the third arm moves slower when having the arm length increased, arm B7 in symmetric star B(B7)3 decays in a very slow way compared with arm B3 and B5 in asymmetric stars B(B3) (B7)2 and B(B5)(B7)2 respectively. The same trend can be seen from the appearance of scaled star diffusive motions in Figure 6.

ACF for the unit vectors directed from the branch point to the end-points of the asymmetric arms of T-shaped asymmetric stars.

Time-dependent diffusion coefficients for symmetric star B(B7)3 and two asymmetric stars with various asymmetric arms, compared with the corresponding linear chains indicated in Figure 2.

From Figure 6, we can see that the diffusion coefficients for all the star polymers are the smallest on each figure from top to bottom. These stars move not only slower than their corresponding linear backbone chains but also after the linear chains with same molecular mass. This observation become clearer when we increase the asymmetric arm length from B3 to B5, and for the largest symmetric star B(B7)3 it moves the slowest beyond the time 105 ps.

4 Conclusions

The dynamical trend of asymmetric stars has been studied by using coarse graining method. Results are presented by the comparisons with both linear and symmetric star topologies. It is found that for asymmetric stars with the same backbone chain, by increasing the asymmetric arm length, stars feel more and more branch point constraints that they behave a slower diffusion than corresponding linear chains, this trend is shown clearer to the asymmetric star with longer backbone chain.

In this work, it is clear to see that within our current simulation runtime, the relatively long linear or star polymers with arms in high molecular mass are not fully diffused or well relaxed. Extra simulation times are still needed for those polymers to get better statistics.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant: 21704010), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant: 2015010217-301), and the European Union’s Seventh Frame-work Program (FP7) through the Marie Curie initial training network DYNamics of Architecturally Complex Polymers (Grant: 214627).

References

1 Pearson D.S., Ver Strate G., von Meerwall E., Schilling F.C., Viscosity and Self-Diffusion Coefficient of Linear Polyethylene. Macromolecules, 1987, 20, 1133-1141.10.1021/ma00171a044Search in Google Scholar

2 Pearson D.S., Fetters L.J., Graessley W.W., Ver Strate G., von Meerwall E., Viscosity and Self-Diffusion Coefficient of Hydrogenated Polybutadiene. Macromolecules, 1994, 27, 711-719.10.1021/ma00081a014Search in Google Scholar

3 Bartels C.R., Crist B., Fetters J., Graessley W.W., Self-diffusion in branched polymer melts. Macromolecules, 2002, 19(3), 4309-4311.10.1021/ma00157a050Search in Google Scholar

4 Pyckhout-Hintzen W., Allgaier J., Richter D., Recent developments in polymer dynamics investigations of architecturally complex systems. Eur. Polym. J., 2011, 47, 474-485.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2010.09.031Search in Google Scholar

5 Harmandaris V.A., Mavrantzas V.G., Theodorou D.N., Kröger M., Ramírez J., Öttinger H.C., et al., Crossover from the Rouse to the Entangled PolymerMelt Regime: Signals from Long, Detailed Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Supported by Rheological Experiments. Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 1376-1387.10.1021/ma020009gSearch in Google Scholar

6 Rouse P.E., A Theory of the Linear Viscoelastic Properties of Dilute Solutions of Coiling Polymers. J. Chem. Phys., 1998, 108, 4628-4633.10.1063/1.1699180Search in Google Scholar

7 De Gennes P.G., Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. Cornell University Press, New York, 1979.Search in Google Scholar

8 Doi M., Edwards S.F., The Theory of Polymers Dynamics. Oxford Science Publications, U.K., 1986.Search in Google Scholar

9 Frischknecht A.L., Milner S.T., Pryke A., Young R.N., Hawkins R., McLeish T.C.B., Rheology of Three-Arm Asymmetric Star Polymer Melts. Macromolecules, 2002, 35, 4801-4820.10.1021/ma0101411Search in Google Scholar

10 Brown S., Szamel G., Computer simulation of three-arm star polymers. Macromol. Theor. Simul., 2000, 9, 14-19.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3919(20000101)9:1<14::AID-MATS14>3.0.CO;2-6Search in Google Scholar

11 Masubuchi Y., Yaoita T., Matsumiya Y., Watanabe H., Primitive chain network simulations for asymmetric star polymers. J. Chem. Phys., 2011, 134, 775-S100.10.1063/1.3590276Search in Google Scholar

12 Zhou Q. Larson R.G., Direct Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Branch Point Motion in Asymmetric Star Polymer Melts. Macromolecules, 2007, 40, 3443-3449.10.1021/ma070072bSearch in Google Scholar

13 Liu X., Zhou C., Xia H., Zhou Y., Jiang W., Dissipative particle dynamics simulation on the self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers under rigid spherical confinements. e-Polymers, 2017, 17, 321-331.10.1515/epoly-2016-0306Search in Google Scholar

14 Padding J.T., Briels W.J., Systematic coarse-graining of the dynamics of entangled polymer melts: the road from chemistry to rheology. J. Phys.-Condens. Mat., 2011, 23, 233101.10.1088/0953-8984/23/23/233101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Hur K., Jeong C., Winkler R.G., Lacevic N., Hee R.H., Yoon D.Y., Chain Dynamics of Ring and Linear Polyethylene Melts from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Macromolecules, 2011, 44(7), 2311-2315.10.1021/ma102659xSearch in Google Scholar

16 Jabbarzadeh A., Atkinson J.D., Tanner R.I., Effect of Molecular Shape on Rheological Properties in Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Star, H, Comb, and Linear Polymer Melts. Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 5020-5031.10.1021/ma025782qSearch in Google Scholar

17 Karayiannis N.C., Mavrantzas V.G., Hierarchical Modelling of the Dynamics of Polymers with a Nonlinear Molecular Architecture: Calculation of Branch Point Friction and Chain Reptation Time of H-Shaped Polyethylene Melts from Long Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Macromolecules, 2005, 38, 8583-8596.10.1021/ma050989fSearch in Google Scholar

18 Agostini S., Hutchings L., Synthesis and temperature gradient interaction chromatography of model asymmetric star polymers by the macromonomer approach. Eur. Polym. J., 2013, 49, 2769-2784.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.06.021Search in Google Scholar

19 Hsu J., Li C., Sugiyama K., Mezzenga R., Hirao A., Chen W., Synthesis and morphology of new asymmetric star polymers of poly[4-(9,9-dihexylfloren-2-yl)styrene]-block-poly(2-vinylpyridine) and their non-volatile memory device applications. Soft Matter, 2011, 7, 8440-8449.10.1039/c1sm05792hSearch in Google Scholar

20 Grest G.S., Fetters L.J., Huang J. Richter S.D., Star Polymers: Experiment Theory and Simulation”. Adv. Chem. Phys.: Polymeric Systems, 1996, XCIV, 67-163.10.1002/9780470141533.ch2Search in Google Scholar

21 Liu L., Padding J.T., den Otter W.K., Briels W.J., Coarse-grained simulations of moderately entangled star polyethylene melts. J. Chem. Phys., 2013, 138, 925.10.1063/1.4811675Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Liu L., den Otter W.K., Briels W.J., Coarse-Grained Simulations of Three-Armed Star Polymer Melts and Comparison with Linear Chains. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2018, 122, 10210-10218.10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b03104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23 Padding J.T., Briels W.J., Uncrossability constraints in mesoscopic polymer melt simulations: Non-Rouse behavior of C 120H242 J. Chem. Phys., 2001, 115, 2846-2859.10.1063/1.1385162Search in Google Scholar

24 Reith D., Pütz M., Müller-Plathe F., Deriving Effective Mesoscale Potentials from Atomistic Simulations. J. Comput. Chem., 2010, 24, 1624-1636.10.1002/jcc.10307Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Fan and Liu, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die