Abstract

Cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles were synthesized via distillation precipitation polymerization of acrylic acid and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate withdifferent molar ratios. Spherical nanoparticles with diameters between 75 and 122 nm were synthesized and exhibited temperature and pH-responsive behaviors. However, this behavior was less pronounced for samples with higher cross-linking degrees. The potential of all nanoparticles as carriers for controlled release of doxorubicin (DOX) anti-cancer drug was examined at pH values of 1.2, 5.3 and 7.4. An obvious alleviation in burst release behavior and the amount of cumulative drug release was seen for all nanoparticles as the pH of the medium and the cross-linking degree of nanoparticle increased. Also kinetics of drug release was studied using mathematical models of zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas and Hixson-Crowell, where Higuchi and Korsmeyer-Peppas models best defined the kinetics of drug release.

1 Introduction

Synthetic polymer nanoparticles in the field of nanomedicines can act either as just drug carriers, hence they need to be water-soluble and safe to body, or they can actively corporate to the drug release process, hence they should be stimuli-responsive (1, 2, 3, 4). Applying external stimuli including changes in pH, temperature, ionic strength, oxidation/reduction potential, light and electric or magnetic fields, responses may occur as changes in conformation, swelling/collapsing, dissolution/precipitation, etc. (5, 6, 7, 8). However, the most attention has been given to temperature- and pH-responsive polymers such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) (9,10) and poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) (11,12), poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) (13,14) and poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA) (15,16). PAA as a hydrophilic biocompatible polyacid has distinguished pH-responsive properties due to its ionizable carboxyl groups which make it a suitable choice as a carrier in drug delivery systems (17,18). Although acid dissociation constant of PAA has been reported in the literature (pKa = 4.2) (19), the pH-responsive behavior of PAA needs to be studied for its cross-linked particulate form. Moreover, no mentionable report exists on the temperature-sensitivity of cross-linked PAA as an individual nanoparticle. PAA shows a response to temperature, even not necessarily sharp, because of change in hydrogen bonding, dispersive forces, etc. resulted in agglomeration of polymer chains and so on (20,21). Disruption of hydrogen bonding by temperature is not of importance for linear PAA which is a water-soluble polyanion, while it becomes important when segments of a hydrophobic cross-linker as comonomer are present in the PAA nanoparticle structure. This temperature-sensitivity is therefore expected to be affected by the amount of hydrophobicity of the cross-linker comonomer, degree of cross-linking and also pH of the medium.

Distillation precipitation polymerization (DPP) is a time-saving colloidal polymerization method which yields micro/nanospheres with a uniform size distribution without using surfactants or stabilizers (22,23). This favors the polymerization of many common monomers as reported in the literature, especially for drug release applications where the monodispersity of carriers and absence of toxic additional chemicals are important (24,25). In the present work, cross-linked PAA nanoparticles with uniform size distributions are fabricated via DPP. Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) is used as cross-linker and different monomer to cross-linker molar ratios are chosen to study the effect of degree of cross-linking on stimuli-responsive properties of synthesized nanoparticles. Synthesized nanoparticles are used as carriers of DOX as anti-cancer drug and release behaviors are investigated in different conditions. Finally, mathematical release models including zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas and Hixson-Crowell are fitted to the drug release data to explain release mechanism.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

Acrylic acid (AA, Merck, 99%) and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, Merck, 98%) as monomers were passed through alumina column to remove inhibitor before use. Acetonitrile (Merck, 99.9%) was used without further purification. 2,2ʹ-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, Acros, 99%) as initiator in distillation precipitation polymerization, was recrystallized from ethanol. Sodium chloride (NaCl) (Merck, 99.5%), potassium chloride (KCl) (Merck, 99.5%), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) (Merck, 99.5%) and di-sodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate (Na2HPO4⋅12H2O) (Merck, 99%) were used to prepare phosphate buffer saline (PBS) with distilled water for drug loading and release experiments. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (Adrimycin ®CS, Pfizer, 2mg/mL solution) was used as model drug. Cellulose membrane dialysis tube with molecular weight cut-off of 14,000 (Sigma-Aldrich, D9652) was used after careful washing to remove glycerol and sulfur compounds to carry out the drug release experiments.

2.2 Synthesis of cross-linked PAA nanoparticles

Cross-linked PAA nanoparticles were fabricated via DPP of AA and EGDMA with different molar ratios of monomer and cross-linker (90:10, 80:20, 70:30 and 60:40). As an example, a 100-mL two-necked flask containing 80 mL acetonitrile equipped with a Liebig condenser and a receiver was heated to 50°C. The monomers were added to the flask in appropriate ratios (2.5 vol% with respect to total volume of the mixture) under N2 atmosphere. AIBN (1 mol% of total monomer content) was added and the reaction stared to progress by heating to boiling point of acetonitrile. When half of the solvent was collected in the receiver, the reaction was stopped by adding a trace amount of hydroquinone solution. The product was separated and washed with acetonitrile by several times of centrifugation and re-dispersion. It was dried in vacuum oven at 100 mbar and 50°C overnight. Total monomer conversions were measured by gravimetry as 41.7, 52.3, 45.4 and 44.7% for 90:10, 80:20, 70:30 and 60:40 samples respectively.

2.3 Investigation of stimuli-responsive behavior of nanoparticles

pH- and temperature-responsive behaviors of the nanoparticles were investigated using UV-visible spectrometer at 600 nm. A 0.1 mg/mL aqueous dispersion of each nanoparticle was prepared at pH values between 2 and 10 for pH-sensitive studies at 24°C. Same dispersions at pH = 1.2, 7.4 and 10 were heated from 15 to 51°C with 3°C steps and 20 min time of equilibrium at each step for temperature-responsive studies.

2.4 DOX loading and release experiments

Loading of DOX into nanoparticles was carried out for 20 mg samples in 6 mL aqueous drug solutions with concentration of 1 mg/mL. pH was adjusted to 8 to ensure that DOX is not charged regarding its isoelectric point (pI = 8.25) (26). Loading was accomplished by stirring at room temperature and dark for 48 h. Drug loading capacity (DLC) was calculated according to Eq. 1 (27) at λ = 480 nm to measure the concentration of DOX solution after the separation of nanoparticles by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min.

An absorbance- concentration calibration curve was prepared in advance. To remove the surface adsorbed DOX molecules, the loaded nanoparticles were washed once before drying in vacuum oven at room temperature.

In vitro drug release behaviors were investigated in different pH conditions at 37°C. 1 mL of a 4 mg/mL dispersion of each nanoparticle was poured into dialysis tubes and immersed into 80 mL buffer solutions at pH = 1.2, 5.3 and 7.4. As a comparison, a same release experiment was performed for free drug. Concentration of the dialysate was measured at pre-determined time intervals using UV-visible spectrometer.

2.5 Characterizations

Morphology of nanoparticles was characterized with a TESCAN MIRA3 FE-SEM at 15 kV. All the samples were prepared by drop-dry method either on a simple glass lamellae. The specimens were prepared by coating a thin layer on a mica surface using a spin coater. UV-visible absorption at λmax = 480 nm for doxorubicin hydrochloride was measured with Perkin-Elmer Lambda 45 UV/VIS spectrophotometer. 1H NMR (400 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer using deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of synthesized nanoparticles

Chemical structure of the crosslinked PAA samples was studied using 1H-NMR spectra (Figures S1-S4). Chemical shifts at 0.99-1.05, 1.67 and 4.35 belong to the protons of PEGDMA (a: —CH3, b: —CH2— and c: —O—CH2—respectively) (28) and those at 1.67, and 1.87 represent the protons of PAA (d: —CH2— and e: —CH—) (29). The spectra prove the existence of both monomers in the structure of all products revealing that the copolymerization has been done successfully. The amount of cross-linker in each sample can be calculated by Eq. 2 based on the peak area of protons individually represent monomers in polymer structure.

Obtained cross-linker contents in terms of mol% are given in Table 1 where higher amount of EGDMA in feed results in higher amount of crosslinker in particle structure. However, due to the decrease in activity ratio of EGDMA with conversion against AA, for which the activity ratio remains almost constant, the cross-linker contents are lower in the products compared to those in the feeds

Characteristics of the synthesized PAA nanoparticles.

| PAA nanoparticle | Cross-linker content (mol. %) | Number average diameter (nm) | PDI | DLC (mg drug/g nanoparticle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90:10 | 11.3 | 122.4 | 0.114 | 217 |

| 80:20 | 13.5 | 110.2 | 0.120 | 220 |

| 70:30 | 13.7 | 113.6 | 0.125 | 222 |

| 60:40 | 14.0 | 75.4 | 0.119 | 224 |

(30). Also, lower boiling point of EGDMA (98-100°C) than AA (141°C) can be another reason to explain such a phenomenon where partially evaporation of EGDMA along with acetonitrile during DPP process decreases its concentration in polymerization medium.

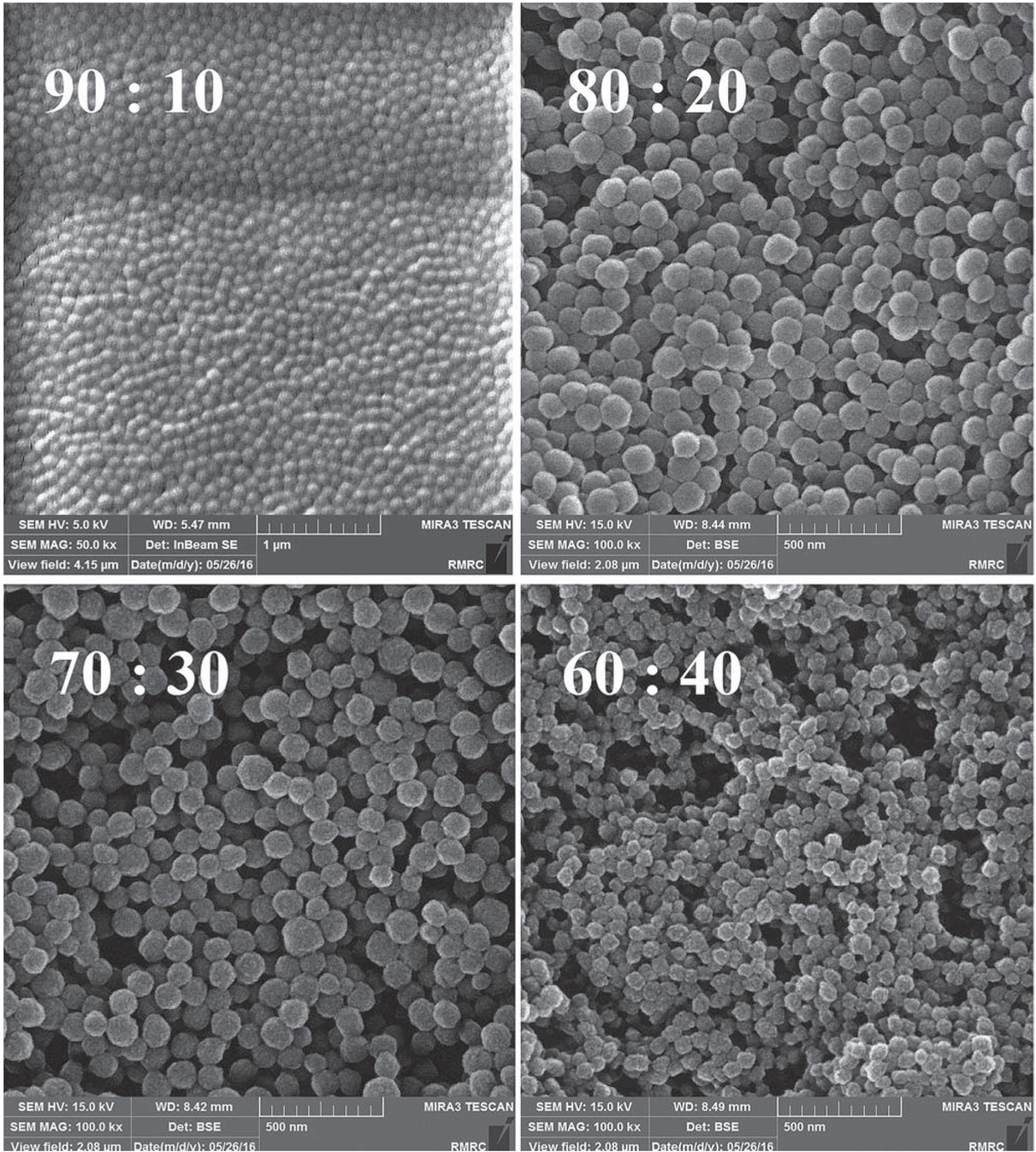

FE-SEM images of PAA nanoparticles are shown in Figure 1. According to the results, well-shaped spherical nanoparticles with a uniform size distribution were fabricated where increase in cross-linker ratio resulted in a decrease in particle size. Results of image analysis based on at least 100 particles are shown in Table 1 (calculations are described in section S4). The relatively small PDI values for all nanoparticles revealed the successful application of DPP method as mentioned before. The fact that the smallest particle size was obtained for the sample with the highest cross-linker amount is explained based on the rigidity of the newly-formed particles in the mid stages of the polymerization process where little amount of monomer can enter the particles and instead more number of particles are formed (higher nucleation) and grow thereafter (31).

FE-SEM images of PAA nanoparticles with different AA: EGDMA molar ratios.

3.2 Stimuli-responsive behavior of PAA nanoparticles

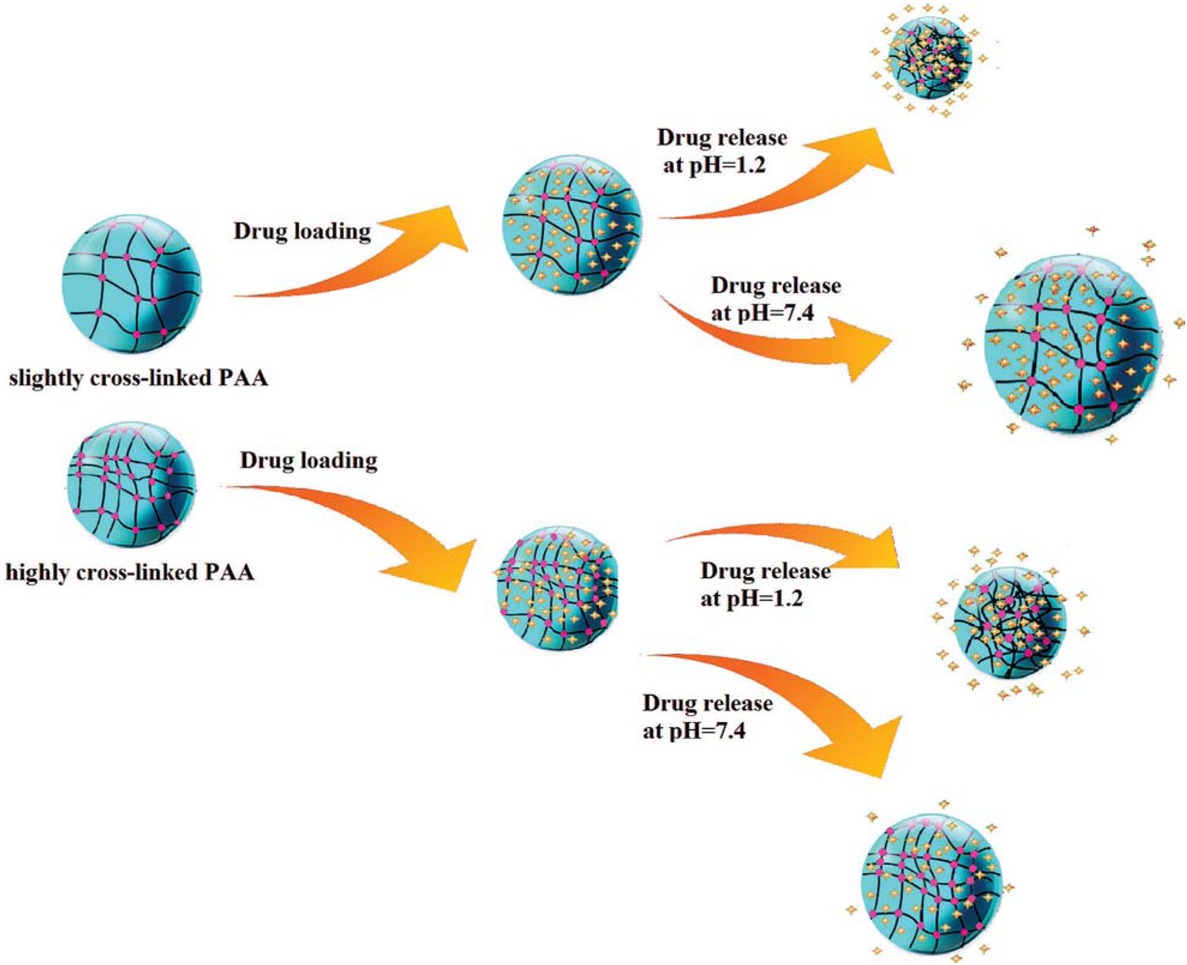

pH-responsive behavior of PAA nanoparticles with different cross-linker contents is illustrated in Scheme 1 which shows that less pH-sensitivity, i.e., change in hydrodynamic diameter of the particle as response to pH variations is expected from the PAA nanoparticle with higher cross-linker content.

pH-responsive behavior of PAA nanoparticles with high and low AA: EGDMA molar ratios and its effect on drug release behavior at 37°C.

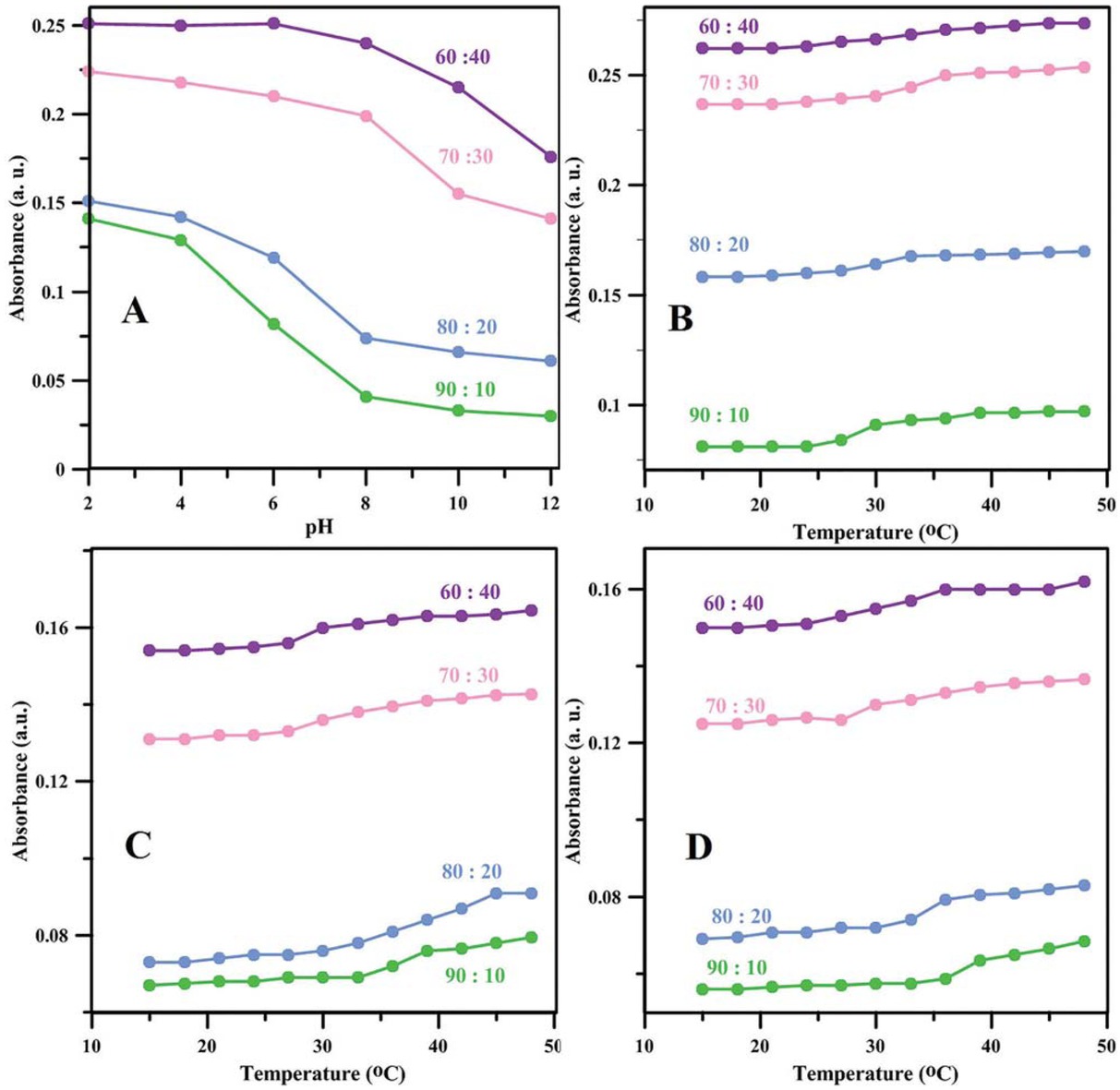

Responses of the PAA nanoparticles to pH and temperature are investigated separately and results are given in Figure 2. Since pH-responsive behaviors for nanoparticles with different monomer to cross-linker ratios are studied at room temperature, the magnitude of hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces remains the same for all samples while the electrostatic repulsions originating from the negatively-charged hydrophilic carboxyl anions of PAA after deprotonation become

pH-responsive behavior at 24°C (a), and temperature-responsive behavior of synthesized nanoparticles at pH values of (b) 1.2, (c) 7.4 and (d) 10.

stronger because of increasing pH (32). Therefore, a continuous decrease in UV absorbance correlated with increase in hydrodynamic diameter of the nanoparticles versus increase in pH is observed in Figure 2a for all samples. However, the magnitude of hydrophobic forces originating from hydrophobic EGDMA segments in the copolymer structure is not similar for all the samples; the sample with the highest cross-linker content, namely 60:40, shows a weaker response to pH which means that the sharp decrease in pH happens at higher pH values. Besides, UV-visible absorbance is the highest for this sample. Also, the sample with the lowest cross-linker content, 90:10, shows the strongest response to pH variations; the sharp decrease in pH happens at lower pH.

These could be attributed to the more rigid structure of the nanoparticle with higher cross-linker content for which the access of medium to carboxyl groups of PAA segments is restricted and consequently, the deprotonation becomes more difficult (33). Even if sufficient deprotonation takes place, there would be a prohibition against electrostatic repulsions exerted by cross-linkages. For all PAA samples, a thermo-responsive behavior, in the form of gradual increase in absorbance versus temperature was also observed, as seen in Figures 2b-d. This is attributed to the disappearance of hydrogen bonding by increasing in temperature (34). Decreasing cross-linker content at a specific pH led to shifting the volume phase transition temperature (VPTT) to higher values. This difference was actually less pronounced at pH = 1.2 where all the nanoparticles were already sufficiently hydrophobic. Similarly, at a specific cross-linker content, increase in pH led to more hydrophilic nature of the nanoparticles and therefore, the VPTT was expectedly shifted to higher values.

3.3 Drug loading and drug release studies

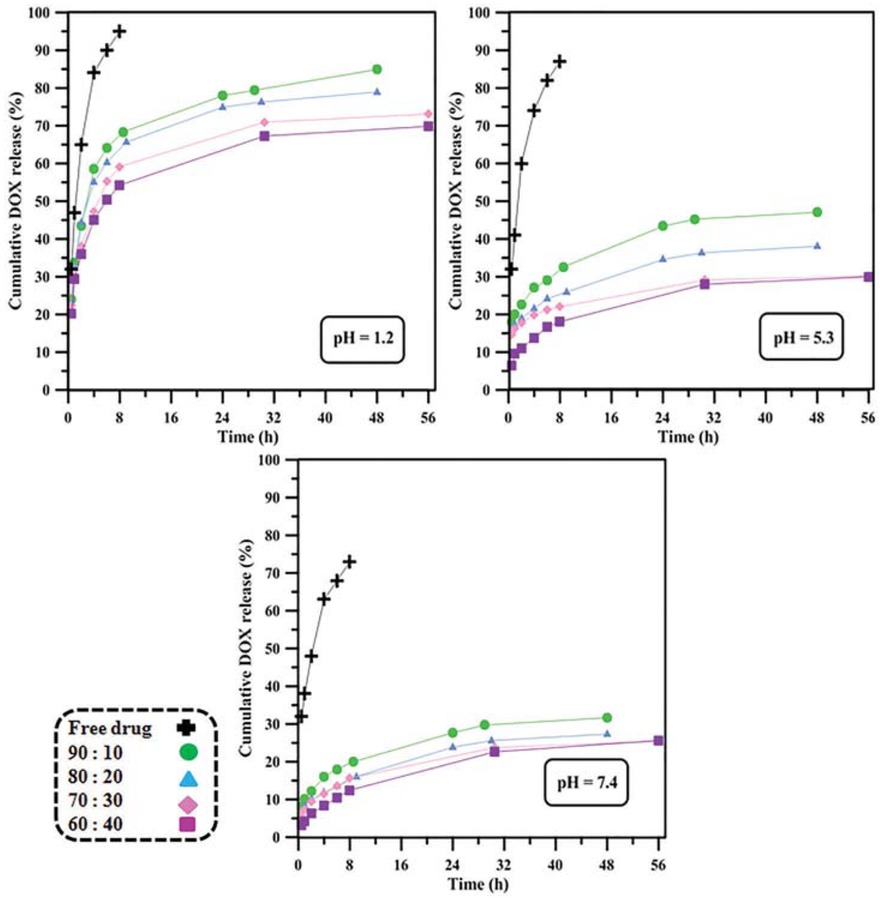

Stimuli-responsive PAA nanoparticles were examined as carriers of DOX as a anti-cancer (35) model drug. A high DLC of about 220 mg g-1 was obtained for all samples as given in Table 1 which is dominated by physical interactions at pH around 8 which is close to its isoelectric point (pI = 8.25) where the drug molecule is not charged. The difference in release behavior of samples with high and low cross-linker contents is schematically shown in Scheme 1. Three different pH values were selected which simulate pH in blood (7.4), slightly acidic pH condition as limit for assimilating vitamins or minerals (5.3) and highly acidic pH condition in stomach (1.2). Since DOX is a basic

drug, its solubility in water increases at low pH values (36). Results for In-vitro release profile from drug-loaded PAA samples at 37°C are shown in Figure 3. A release experiment was also conducted for pure drug as 1 mg/mL solution for comparison. According to results, an obvious burst release behavior was seen for pure drug at all pH values as expected. This immediate release behavior is modified to different extents for nanoparticles with different cross-linker contents and in media with different pH values. Loading the drug into particles alleviates the burst release, since cavities in the cross-linked nanoparticle act as drug storage leading to a timed-release behavior (37,38). The lower amount of cumulative release and reduced immediate release for all nanoparticles at all pH values compared to pure drug confirms this expectation. No burst release was seen for PAA samples at pH = 7.4 and more rapid and higher cumulative release was observed at pH = 5.3. This is due to the higher solubility of DOX at lower pH which increases the tendency of drug molecules to leave the nanoparticle toward the aqueous medium (39). Lowering the pH to 1.2 results in a significantly higher cumulative release and a more obvious burst release. This can be ascribed tohydrophilic nature of DOX at low pH values. The other effective factor is the shrinkage of the PAA segments in response to pH reduction. This particle shrinkage exerts a force which further drives the drug molecules outside the nanoparticle (40). In this sense, the degree of cross-linking of the nanoparticles plays a role; as the cross-linker content increases, the drug molecules are faced a greater prevention against diffusion outside the particle due to more rigid structure of the nanoparticle. Moreover, the higher cross-linking degree results in lower degree of pH-responsivity as stated earlier and shown in Scheme 1. Therefore, the 60:40 nanoparticle at pH = 7.4 shows the most controlled release behavior among all nanoparticles and at all pH values.

Drug release behavior of nanoparticles at 37°C and pH values of 1.2, 5.3 and 7.4.

3.4 Kinetics of drug release

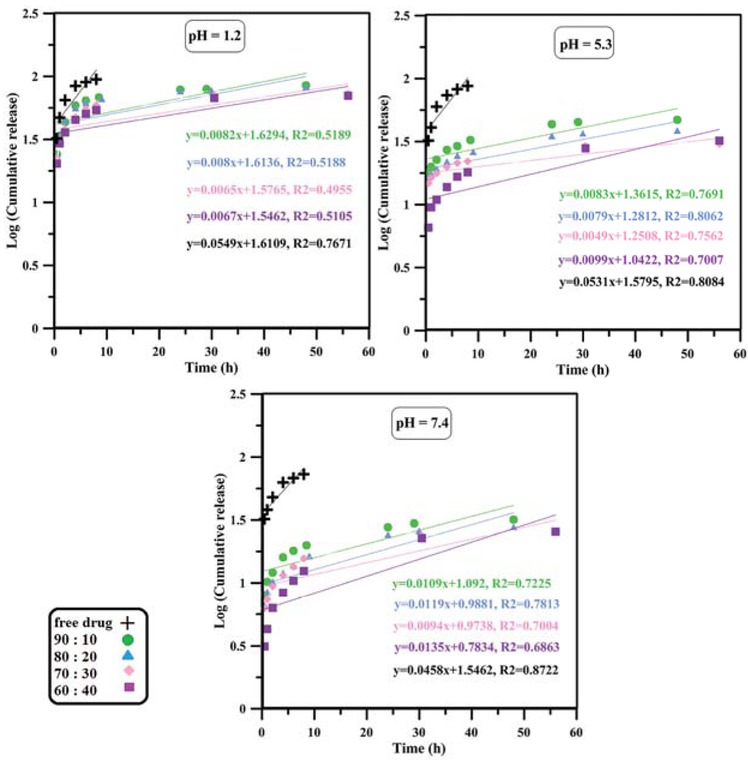

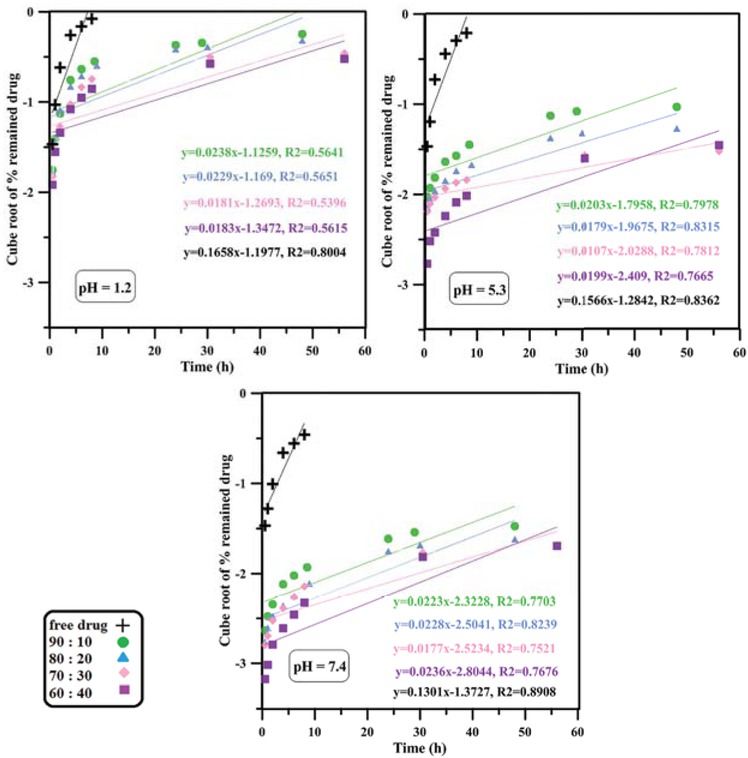

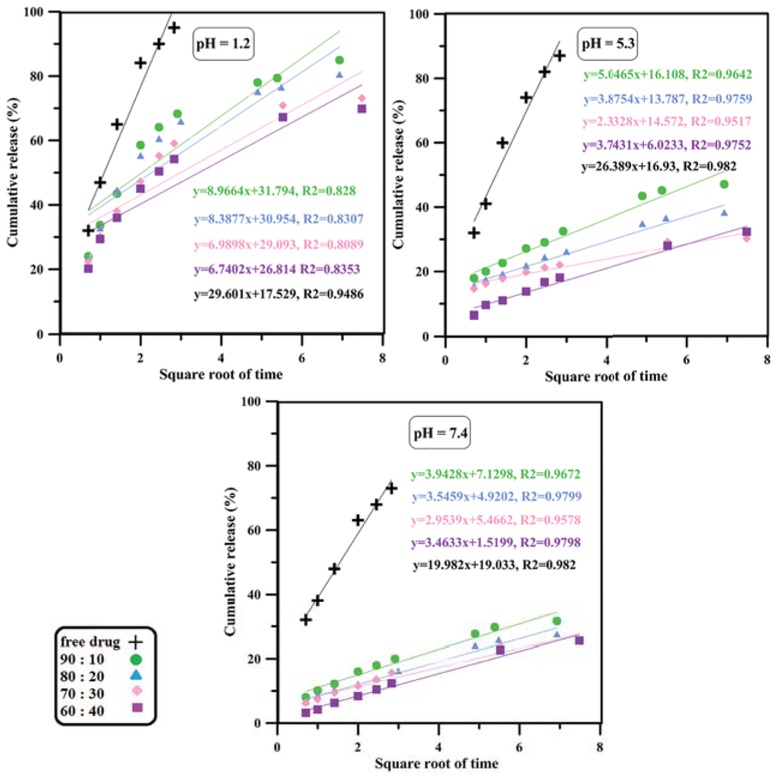

Kinetics of drug release was studied using the most well-known mathematical models such as zero-order, first-order, Hixson-Crowell, Higuchi and Korsmeyer-Peppas (41,42). The models were fitted to the data by linear regression with R2 as correlation coefficient and fitting parameters are shown in Table 2 and Figures 4-8. According to the results, it seems that zero-order, first-order and Hixson-Crowell models are insufficient to define the release kinetics as they do not fit the data properly. Zero-order model is used for slow drug release kinetics as for matrices containing low solubility drugs which is not the case for relatively rapid release of doxorubicin hydrochloride from pH-responsive PAA nanoparticles. First-order model mostly applies to porous matrices and hence cannot describe drug release from our system well. Moreover, Hixson-Crowell model applies to systems where the surface area of drug carrier diminishes gradually as result of dissolution, while the PAA nanoparticles studied in this paper do not dissolve since they are partially cross-linked. In contrast, a relatively good correlation seems to exist between experimental data and regression lines obtained from Higuchi and

The curve of zero-order model mechanism of drug release.

Drug release kinetic model parameters for nanoparticles with different AA : EGDMA ratios.

| Kinetic models | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | First-order | Hixson-Crowell | Higuchi | Korsmeyer-Peppas | |||||||||

| pH | Samples | Qt =Q 0+ KOt | ft =KH t1/2 | Mt/M∞ =atn | |||||||||

| R2 | Ko | R2 | K | R2 | k | R2 | KH | R2 | am∞ | n | |||

| Free drug | 0.859 | 7.896 | 0.767 | 0.121 | 0.800 | 0.166 | 0.949 | 29.60 | 0.972 | 45.53 | 0.393 | ||

| 90:10 | 0.652 | 1.050 | 0.519 | 0.018 | 0.564 | 0.024 | 0.830 | 8.966 | 0.924 | 34.666 | 0.266 | ||

| 1.2 | 80:20 | 0.655 | 0.982 | 0.519 | 0.018 | 0.565 | 0.023 | 0.831 | 8.388 | 0.922 | 33.582 | 0.260 | |

| 70:30 | 0.625 | 0.739 | 0.496 | 0.014 | 0.540 | 0.018 | 0.809 | 6.990 | 0.930 | 30.960 | 0.252 | ||

| 60:40 | 0.659 | 0.720 | 0.511 | 0.015 | 0.562 | 0.018 | 0.835 | 6.740 | 0.934 | 28.874 | 0.255 | ||

| Free drug | 0.886 | 7.095 | 0.8084 | 0.117 | 0.836 | 0.157 | 0.964 | 26.39 | 0.982 | 42.49 | 0.372 | ||

| 90:10 | 0.847 | 0.624 | 0.769 | 0.018 | 0.798 | 0.020 | 0.964 | 5.047 | 0.990 | 20.012 | 0.229 | ||

| 5.3 | 80:20 | 0.875 | 0.484 | 0.8062 | 0.017 | 0.832 | 0.018 | 0.976 | 3.875 | 0.986 | 16.932 | 0.211 | |

| 70:30 | 0.826 | 0.261 | 0.756 | 0.011 | 0.781 | 0.011 | 0.952 | 2.333 | 0.992 | 16.136 | 0.160 | ||

| 60:40 | 0.871 | 0.426 | 0.701 | 0.022 | 0.761 | 0.020 | 0.975 | 3.743 | 0.992 | 8.837 | 0.333 | ||

| Free drug | 0.923 | 5.433 | 0.872 | 0.101 | 0.891 | 0.130 | 0.982 | 19.98 | 0.993 | 39.093 | 0.310 | ||

| 90:10 | 0.850 | 0.488 | 0.723 | 0.024 | 0.770 | 0.022 | 0.967 | 3.943 | 0.996 | 10.121 | 0.311 | ||

| 7.4 | 80:20 | 0.889 | 0.445 | 0.781 | 0.026 | 0.824 | 0.023 | 0.967 | 3.546 | 0.992 | 1.232 | 0.325 | |

| 70:30 | 0.837 | 0.332 | 0.700 | 0.021 | 0.752 | 0.018 | 0.958 | 2.954 | 0.993 | 7.637 | 0.316 | ||

| 60:40 | 0.885 | 0.396 | 0.686 | 0.030 | 0.768 | 0.024 | 0.980 | 3.463 | 0.994 | 4.455 | 0 .460 | ||

The curve of first-order model mechanism of drug release.

The curve of Higuchi model mechanism of drug release.

The curve of Korsmeyer-Peppas model mechanism of drug release.

The curve of Hixson-Crowell model mechanism of drug release.

Korsmeyer-Peppas models which can be attributed to the application of the former model to systems with water-soluble drugs and the latter to drug release from polymer matrices (43,44). The value of n parameter in Korsmeyer-Peppas model corresponds to release mechanism; since n < 0.45 for almost all nanoparticles at any pH condition, a Fickian diffusion mechanism of drug outward the nanoparticles was suggested.

4 Conclusions

PAA nanoparticles with four different monomer to cross-linker molar ratios, 90:10, 80:20, 70:30 and 60:40 where fabricated via DPP method. All nanoparticles showed response to pH and temperature variations; a relatively sharp decrease in UV absorbance as response to pH increase and a gradual increase in UV absorbance with increase in temperature were observed as result of electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged PAA carboxyl anions and disappearance of hydrogen bonds, respectively. Higher cross-linker contents led to weaker pH response and lower VPTT. Profiles of release for DOX as model drug from the nanoparticles were investigated showing a modified release behavior with lowered burst release as the cross-linker content and pH of the release medium increased. The 60:40 sample showed the most desirable controlled release behavior. Kinetics of drug release was studied using mathematical models such as zero-order, first-order, Hixson-Crowell, Higuchi and Korsmeyer-Peppas, where Higuchi and Korsmeyer-Peppas best fitted the release data since the former applies to water-soluble drugs and the latter applies to release from polymer matrices.

Supplementary material1H NMR results; Particle size analysis.

References

1 Calderó G., Montes R., Llinàs M., García-Celma M.J., Porras M., Solans C., Studies on the formation of polymeric nano-emulsions obtained via low-energy emulsification and their use as templates for drug delivery nanoparticle dispersions. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2016, 145, 922-931.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.06.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Golshan M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Mirshekarpour M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Mohammadi M., Synthesis and characterization of poly(propylene imine)-dendrimer-grafted gold nanoparticles as nanocarriers of doxorubicin. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2017, 155, 257-265.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.04.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Zhang Z., Zhang D., Wei L., Wang X., Xu Y, Li H.-W., et al., Temperature responsive fluorescent polymer nanoparticles (TRFNPs) for cellular imaging and controlled releasing of drug to living cells. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2017, 159, 905-912.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.08.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Nikravan G., Haddadi-Asl V., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis of dual temperature– and pH-responsive yolk-shell nanoparticles by conventional etching and new deswelling approaches: DOX release behavior. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2018, 165, 1-8.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.02.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5 Aydınoğlu D., Investigation of pH-dependent swelling behavior and kinetic parameters of novel poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels with spirulina. e-Polymers, 2015, 15, 81-93.10.1515/epoly-2014-0170Search in Google Scholar

6 Samadaei F., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Grafting of Poly(Acrylic Acid) onto Poly(amidoamine)-Functionalized Graphene Oxide via Surface-mediated Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer Polymerization. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater, 2016, 65, 302-309.10.1080/00914037.2015.1119686Search in Google Scholar

7 Haqani M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis of dual-sensitive nanocrystalline cellulose-grafted block copolymers of N-isopropylacrylamide and acrylic acid by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Cellulose, 2017, 24, 2241-2254.10.1007/s10570-017-1249-2Search in Google Scholar

8 Abdollahi E., Abdouss M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Mohammadi A., Molecular Recognition Ability of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nano- and Micro-Particles by Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer Polymerization. Polym Rev, 2016, 56, 557-583.10.1080/15583724.2015.1119162Search in Google Scholar

9 De Santis S., La Mesa C., Masci G., On the upper critical solution temperature of PNIPAAM in an ionic liquid: Effect of molecular weight, tacticity and water. Polymer, 2017, 120, 52-58.10.1016/j.polymer.2017.05.059Search in Google Scholar

10 Nasiri S.-S., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Dehghani E., Stimuli-responsive behavior of smart copolymers-grafted magnetic nanoparticles: Effect of sequence of copolymer blocks. Inorg Chim Acta, 2018, 476, 83-92.10.1016/j.ica.2018.02.027Search in Google Scholar

11 Nikdel M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Hosseini M.S., Dual thermo-and pH-sensitive poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-acrylic acid)-grafted graphene oxide. Colloid Polym Sci, 2014, 292, 2599-2610.10.1007/s00396-014-3313-xSearch in Google Scholar

12 Schöttner S., Schaffrath H.-J., Gallei M., Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-Based Amphiphilic Block Copolymers for High Water Flux Membranes and Ceramic Templates. Macromolecules, 2016, 49, 7286-7295.10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01803Search in Google Scholar

13 Nikravan G., Haddadi-Asl V., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis of pH-responsive magnetic yolk-shell nanoparticles: a comparison between the conventional etching and new deswelling approaches. Appl Organometal Chem, 2018, 32, e4272.10.1002/aoc.4272Search in Google Scholar

14 Cheng W.-M., Hu X.-M., Zhao Y.-Y., Wu M.-Y., Hu Z.-X., Yu X.-T., Preparation and swelling properties of poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) composite hydrogels. e-Polymers, 2017, 17, 95-106.10.1515/epoly-2016-0250Search in Google Scholar

15 Mohammadi M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Golshan M., Effect of molecular weight and polymer concentration on the triple temperature/pH/ionic strength-sensitive behavior of poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate). Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater, 2017, 66, 455-461.10.1080/00914037.2016.1236340Search in Google Scholar

16 Rehman S., Khan A.R., Shah A., Badshah A., Siddiq M., Preparation and characterization of poly(N-isoproylacrylamide-co-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) microgels and their composites of gold nanoparticles. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp, 2017, 520, 826-833.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.02.060Search in Google Scholar

17 Panahian P., Salami-Kalajahi M., Hosseini M.S., Synthesis of Dual Thermosensitive and pH-Sensitive Hollow Nanospheres Based on Poly(acrylic acid-b-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) via an Atom Transfer Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Radical Process. Ind Eng Chem Res, 2014, 53, 8079-8086.10.1021/ie500892bSearch in Google Scholar

18 Ding H., Zhang X.N., Zheng S.Y., Song Y., Wu Z.L., Zheng Q., Hydrogen bond reinforced poly(1-vinylimidazole-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels with high toughness, fast self-recovery, and dual pH-responsiveness. Polymer, 2017, 131, 95-103.10.1016/j.polymer.2017.09.044Search in Google Scholar

19 Wiśniewska M., Urban T., Grządka E., Zarko V., Gunsko V.M., Comparison of adsorption affinity of polyacrylic acid for surfaces of mixed silica–alumina. Colloid Polym Sci, 2014, 292, 699-705.10.1007/s00396-013-3103-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20 Panahian P., Salami-Kalajahi M., Hosseini M.S., Synthesis of dual thermoresponsive and pH-sensitive hollow nanospheres by atom transfer radical polymerization. J Polym Res, 2014, 21, 455.10.1007/s10965-014-0455-ySearch in Google Scholar

21 Szabó Á., Szanka I., Tolnai G., Szarka G., Iván B., LCST-type thermoresponsive behaviour of interpolymer complexes of well-defined poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate)s and poly(acrylic acid) synthesized by ATRP. Polymer, 2017, 111, 61-66.10.1016/j.polymer.2017.01.018Search in Google Scholar

22 Modarresi-Saryazdi S.M., Haddadi-Asl V., Salami-Kalajahi M., N,N’-methylenebis(acrylamide)-crosslinked poly(acrylic acid) particles as doxorubicin carriers: A comparison between release behavior of physically loaded drug and conjugated drug via acid-labile hydrazone linkage. J Biomed Mater Res A, 2018, 106, 342-348.10.1002/jbm.a.36240Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23 Liu L., Zeng J., Zhao X., Tian K., Liu P., Independent temperature and pH dual-responsive PMAA/PNIPAM microgels as drug delivery system: Effect of swelling behavior of the core and shell materials in fabrication process. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp, 2017, 526, 48-55.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.11.007Search in Google Scholar

24 Torkpur-Biglarianzadeh M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Multilayer fluorescent magnetic nanoparticles with dual thermoresponsive and pH-sensitive polymeric nanolayers as anti-cancer drug carriers. RSC Adv, 2015, 5, 29653-29662.10.1039/C5RA01444ASearch in Google Scholar

25 Gong C., Shan M., Li B., Wu G., A pH and redox dual stimuli-responsive poly(amino acid) derivative for controlled drug release. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2016, 146, 396-405.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.06.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26 Fallahi-Sambaran M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Dehghani E., Abbasi F., Investigation of different core-shell toward Janus morphologies by variation of surfactant and feeding composition: A study on the kinetics of DOX release. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2018, 170, 578-587.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.06.064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Noein L., Haddadi-Asl V., Salami-Kalajahi M., Grafting of pH-sensitive poly (N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate-co-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) onto HNTS via surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization for controllable drug release. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater, 2017, 66, 123-131.10.1080/00914037.2016.1190927Search in Google Scholar

28 Safajou-Jahankhanemlou M., Abbasi F., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis and characterization of thermally expandable PMMA-based microcapsules with different cross-linking density. Colloid Polym Sci, 2016, 294, 1055-1064.10.1007/s00396-016-3862-2Search in Google Scholar

29 Nikdel M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Hosseini M.S., Synthesis of Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate-co-Acrylic Acid)-Grafted Graphene Oxide Nanosheets via Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer Polymerizations. RSC Adv, 2014, 4, 16743-16750.10.1039/c4ra01701cSearch in Google Scholar

30 Emaldi I., Hamzehlou S., Sanchez-Dolado J., Leiza J.R., Kinetics of the Aqueous-Phase Copolymerization of MAA and PEGMA Macromonomer: Influence of Monomer Concentration and Side Chain Length of PEGMA. Processes, 2017, 5, 19.10.3390/pr5020019Search in Google Scholar

31 McCann J., Thaiboonrod S., Ulijn R.V., Saunders B.R., Effects of crosslinker on the morphology and properties of microgels containing N-vinylformamide, glycidylmethacrylate and vinylamine. J Colloid Interface Sci, 2014, 415, 151-158.10.1016/j.jcis.2013.09.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Mohammadi M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Golshan M., Synthesis and investigation of dual pH- and temperature-responsive behaviour of poly[2-(dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate)-grafted gold nanoparticles. Appl Organometal Chem, 2017, 31, e3702.10.1002/aoc.3702Search in Google Scholar

33 Sheikholeslami Z.S., Salimi-Kenari H., Imani M., Atai M., Nodehi A., Exploring the effect of formulation parameters on the particle size of carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles prepared via reverse micellar crosslinking. J Microencapsul, 2017, 34, 270-279.10.1080/02652048.2017.1321047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34 Banaei M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-grafted poly(aminoamide) dendrimers as polymeric nanostructures. Colloid Polym Sci, 2015, 293, 1553-1559.10.1007/s00396-015-3559-ySearch in Google Scholar

35 Villarreal-Gómez L.J., Serrano-Medina A., Torres-Martínez E.J., Perez-González G.L., Cornejo-Bravo J.M., Polymeric advanced delivery systems for antineoplasic drugs: doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil. e-Polymers, 2018, 18, 359-372.10.1515/epoly-2017-0202Search in Google Scholar

36 Golshan M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Mohammadi M., Synthesis of poly(propylene imine) dendrimers via homogeneous reduction process using lithium aluminium hydride: Bioconjugation with folic acid and doxorubicin release kinetics. Appl Organometal Chem, 2017, 31, e3789.10.1002/aoc.3789Search in Google Scholar

37 Ebrahimi R., Salavaty M., Controlled drug delivery of ciprofloxacin from ultrasonic hydrogel. e-Polymers, 2018, 18, 187-195.10.1515/epoly-2017-0123Search in Google Scholar

38 Abdollahi E., Khalafi-Nezhad A., Mohammadi A., Abdouss M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Synthesis of new molecularly imprinted polymer via reversible addition fragmentation transfer polymerization as a drug delivery system. Polymer, 2018, 143, 245-257.10.1016/j.polymer.2018.03.058Search in Google Scholar

39 Dehghani E., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Simultaneous two drugs release form Janus particles prepared via polymerization-induced phase separation approach. Colloids Surf B-Biointerfaces, 2018, 170, 85-91.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40 Yaroslavov A., Panova I., Sybachin A., Spiridonov V., Zezin A., Mergel O., et al., Payload release by liposome burst: Thermal collapse of microgels induces satellite destruction. Nanomedicine, 2017, 33, 1491-1494.10.1016/j.nano.2017.02.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41 Tao L., Chan W., Uhrich K.E., Drug loading and release kinetics in polymeric micelles: Comparing dynamic versus unimolecular sugar-based micelles for controlled release. J Bioact Compat Polym, 2016, 31, 227-241.10.1177/0883911515609814Search in Google Scholar

42 Fu Y., Kao W.J., Drug Release Kinetics and Transport Mechanisms of Non-degradable and Degradable Polymeric Delivery Systems. Expert Opin Drug Deliv, 2010, 7, 429-444.10.1517/17425241003602259Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43 Golshan M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Roghani-Mamaqani H., Mohammadi M., Poly(propylene imine) dendrimer-grafted nanocrystalline cellulose: Doxorubicin loading and release behavior. Polymer, 2017, 117, 287-294.10.1016/j.polymer.2017.04.047Search in Google Scholar

44 Jin Z., Wu K., Hou J., Yu K., Shen Y., Guo S., A PTX/nitinol stent combination with temperature-responsive phase-change 1-hexadecanol for magnetocaloric drug delivery: Magnetocaloric drug release and esophagus tissue penetration. Biomaterials, 2018, 153, 49-58.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Nikravan et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die