Abstract

The effects of phosphate nucleating agent (NA), carboxylate nucleating agent (MD), rosin type nucleating agent (WA) and sorbitol nucleating agent (NX) on crystallization behavior of isotactic polypropylene were investigated by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and polarized light microscopy (PLM). The results showed that different structure nucleating agents significantly affected the crystallization kinetics, rate and temperature of polypropylene. Among them, half crystallization time of NX nucleating agent was the shortest, which was 53.4 seconds, and the crystallization temperature was the highest, reaching 129.8°C.

1 Introduction

Polypropylene (PP) has good physical & mechanical properties and excellent processing performance, and has become the most developed and fastest growing polymer of the five general synthetic ones. Because polypropylene is a semi-crystalline polymer, people usually add a certain amount of nucleating agent to improve its crystalline morphology, and realize its functionalization. At present, nucleating agent can be divided into alpha, beta and gamma nucleating agent (1, 2, 3), according to the crystal form. Different kinds of nucleating agents can improve the crystallization rate of polypropylene in the forming process and refine the crystallization, thus improving the comprehensive properties of the material such as toughness, transparency and glossiness. The formation of network structure of sorbitol, which is one of the most common nucleating agents (4, 5), can induce the crystallization of polypropylene.

At present, some researchers have studied crystallization behavior, crystal forms, crystal morphology, and solar reflectance of polypropylene (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). At the same time, the effect of non-isothermal crystallization kinetics, isothermal crystallization kinetics and crystallization rate of PP, has also been investigated to a certain extent (15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

In this works, the effects of phosphate nucleating agent (NA), carboxylate nucleating agent (MD), rosin nucleating agent (WA) and sorbitol nucleating agent (NX) on the crystallization kinetics, rate and temperature of PP were studied. The morphology of nucleated polypropylene was investigated by polarizing microscope.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Homogeneous PP powder (Daqing petrochemical company, China) was blended with different kinds of nucleating agent. Carboxylate nucleating agent (MD), rosin nucleating agent (WA), Sorbitol nucleating agent (NX) and Phosphate nucleating agent (NA), were purchased from Mudanjiang Beida fine chemical plant (China), Zhejiang Wanan plastic co., ltd. (China), American Milliken chemical company (America) and Asahi chemical co., ltd. (Japan), respectively.

2.2 Preparation of sample

Polypropylene powder and four different kinds of nucleating agents were respectively added into a high-speed mixer according to a fixed proportion for mixing. The mixture was melt extrude and pelletized in TSSL-25 corotating twin-screw extruder with a diameter of 25 mm and a length/diameter ratio of 36/1. The screw configuration was designed to provide better mixing and refining dispersion. The barrel temperatures from the feed zone to the die one were set as follows: 190, 210, 220, 220, 220, 220, 210, 200 and 195°C. The screw rate and feed rate were kept constant at 65 rpm and 21 rpm, respectively. The sample sheet with a specified thickness of 1 mm was prepared on a flat vulcanizing machine for mechanical property testing.

2.3 Charaterization

The infrared spectrum in the range of 600~4000 cm-1 was recorded by a FTIR spectrometer (Mod. SPECTRUM GX 2000, Perkin/Elmer Ltd., Beacons-field, Buckshire, UK), and the resolution was 4 cm-1. Samples for FTIR measurements were prepared by realizing films of PP pellets, which were 30 um thick by hot pressing at 210°C. According to the FTIR spectrum, the crystallinity can be calculated with the Eq. 1, wherein k is a constant, and for convenience of comparison, k is set to 1, and a crystallization spectrum band 998 cm-1 and an amorphous spectrum band 1460 cm-1 related to a long spiral segment are selected as internal standards for measuring the crystallinity of the PP film, and A998 and A1460 is at the wave numbers 998 cm-1 and 1460 cm-1, respectively (20).

At room temperature, a wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) measurement was performed by the D/max-2500/PC X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan), which used CuKα radiation operated at 35 kV and 50 mA. The data were collected from 6° to 50° at 3°/min scanning rate. All samples were treated uniformly before testing. According to the XRD spectrum, the integral strength of all crystal sharp diffraction peaks and amorphous diffuse scattering peaks can be calculated by using a computer peak splitting program, and the crystallinity can be calculated according to Eq. 2, wherein Xc represents the crystallinity, Ic represents the integral strength of crystal sharp diffraction peak, and Ia represents the integral strength of amorphous diffuse scattering peak (21).

For the calorimetric investigation, about 6 mg of PP sample was weighed in Sealed aluminum foil, which is then heated from 50°C to 200°C using a Perkin - Elmer Pxrisl type differential scanning calorimeter under N2 (50ml / min of gas flow), and kept at 200°C for 5 min (to eliminate thermal history and make it completely molten), and then DSC curves of various polypropylene samples at 10°C/min were obtained. The degree of crystallinity of PP was calculated by the Eq. 3, wherein Xc represents the crystallinity, wherein △Hm represents the melting enthalpy of PP samples, △H0 represents the melting enthalpy of PP samples with crystallinity of 100% ( 207 J/g) (22).

For the isothermal crystallization: about 6 mg of PP sample was weighed in a crucible, and the sample was rapidly heated from 50°C to 200°C using a Perkin - Elmer Pxrisl type differential scanning calorimeter under N2 (50ml / min of gas flow), and kept at 200°C for 5 min (to eliminate heat history and make it completely molten), and quickly cooled sample to a set temperature (110-140°C), and kept at the constant temperature until crystallization was completed, and then DSC curves of various polypropylene samples were obtained.

There are many other equations able to perform kinetics studies on the crystallization of polymer as shown in Eq. 4, in which Xt represents the relative crystallinity of the crystallization time of t, Zt is the crystallization rate constant, which is related to nucleation rate and crystallization rate, n is Avrami index, which represents the crystallization nucleation and growth mechanism of the polymer.

The logarithm of the above formula is taken to obtain Eq. 5.

According to the plot of 1n(-1n(1-Xt)) and 1nt, the linear slope n and intercept 1nZt can be calculated by the linear equation, and the values of n and Zt can also be calculated, thus obtaining the information on the crystallization growth of polypropylene.

According to the non-isothermal crystallization DSC curve, the relative crystallinity Xt at any crystallization temperature can be calculated by Eq. 6. In the Eq. 6, T0 represents the temperature at the beginning of crystallization, T∞ represents the temperature at the completion of crystallization, T represents the crystallization temperature, and H represents the enthalpy of crystallization. By time-temperature conversion, the Avrami equation can be used to calculate the relationship between the non-isothermal crystallization time t and the relative crystallinity Xt (23, 24).

For isothermal crystallization kinetics, Xt is defined as Eq. 7 (25, 26, 27).

dH/dt is the heat flow rate and Xt is the crystallinity at time t. The relationship between the relative crystallinity t and Xt can be obtained by integrating the DSC curve with the crystallization time t. Using 1n(-1n(1-Xt)) to plot 1nt, the linear slope n and intercept 1nZt can be obtained from the linear equation, and then the values of Zt and n can be obtained.

PLM polarizing microscope measurements were performed by XP-201 polarization microscope test. Firstly, the prepared 0.5 mm sheet was placed on a constant temperature slide of an electric furnace at 260°C, and the cover slide was added after melting, and the temperature was kept for 1 minute, and then the 0.5 mm sheet was quickly put into an oven at 140°C, and crystallized for 1 h, and then taken out.

According to X-ray diffraction theory, the crystal size can be calculated by Debye-Scherrer formula (Eq. 8 and 9) (28), as shown in Eq. 8, where λ = incident wavelength, D = grain diameter, βhkl = half peak width of diffraction peak, θ = diffraction angle, wherein λ is 0.15406 nm, k = 0.9, βhkl = β*2π/360 (converted to radians).

Crystal nucleus density, which is a physical quantity to express the size of polymer spherulites, refers to the number of crystal nuclei in the unit volume, can be calculated directly from the average spherical crystal diameter. The calculation Eq. 10 is:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of nucleating agent on crystallinity of polypropylene

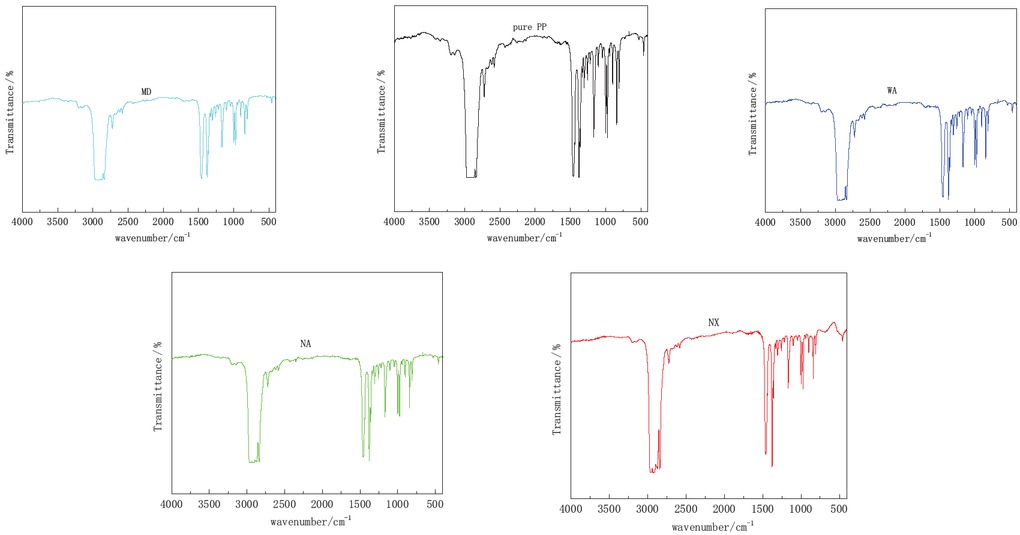

Four modified polypropylene samples were tested by FTIR (as shown in Figure 1), XRD (as shown in Figure 2) and DSC. DSC melt enthalpy data of four modified PP were shown in Table 1. According to Eq. 1-3, the respective crystallinity was calculated.

Infrared spectra of modified PP.

XRD spectra of modified PP.

Melting enthalpy data of modified PP.

| No | Pure PP | NX | NA | WA | MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| △Hm/Jg-1 | 90.11 | 95.98 | 94.33 | 93.59 | 90.99 |

The crystallinity calculated by various test methods is shown in Table 2. Four nucleating agents make the crystalline core of PP easier to form, and significantly increase the crystallinity of PP, in which the crystallinity of the modified PP prepared with NX nucleating agent increased greatly.

The crystallinity of PP.

| No | Nucleating agent | Infrared/% | XRD/% | DSC/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pure pp | 39.65 | 36.22 | 43.53 |

| 2 | NX | 47.44 | 63.25 | 46.37 |

| 3 | NA | 45.27 | 55.69 | 45.57 |

| 4 | WA | 43.68 | 54.17 | 45.21 |

| 5 | MD | 41.55 | 41.14 | 43.95 |

3.2 Effect of nucleating agent on non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of polypropylene

According to the non-isothermal crystallization DSC curves (as shown in Figure 3, the cooling rate was 10°C/min), the relative crystallinity Xt at any crystallization temperature can be calculated by Eq. 6. By time-temperature conversion, the Avrami equation can be used to calculate the relationship between the non-isothermal crystallization time t and the relative crystallinity Xt, as shown in Figure 4.

Non-isothermal crystallization DSC curve of nucleated polypropylene.

Non-isothermal crystallization curve relative crystallinity fraction.

According to Eq. 4 and 5, 1nt is plotted with n(-1n(1-Xt)), and the curve relationship is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen from the figure that 1n(-1n(1-Xt)) has a good linear relationship with 1nt, only at high crystallinity, the data points deviate from the linear law. The rate constants Zt and Avrami exponent n are calculated by slope and intercept. According to the correction of cooling rate, that is, lnZc = lnZt/φ, the rate constant Zc of the non-isothermal crystallization process can be calculated, and the calculation results are shown in Table 1. When Xt = 50%, the half crystallization time t1/2 can also be calculated according to the calculation formula t1/2 = (ln2/Zt)1/n.

Non-isothermal crystallization ln (-ln (1-Xt)) on a linear relationship lnt.

Zc is a non-isothermal crystallization kinetic rate constant, and the larger the value, the faster the crystallization rate of polypropylene is. It can be seen from Table 3, the n value of each modified polypropylene is not different, which indicates that each nucleating agent makes the polypropylene exhibit heterogeneous crystallization, and changes the crystallization nucleation and growth mode of the polypropylene. Compared with other nucleating agents, NX nucleating agents significantly increase the crystallization rate of polypropylene.

3.3 Effect of nucleating agent on isothermal crystallization kinetics of polypropylene

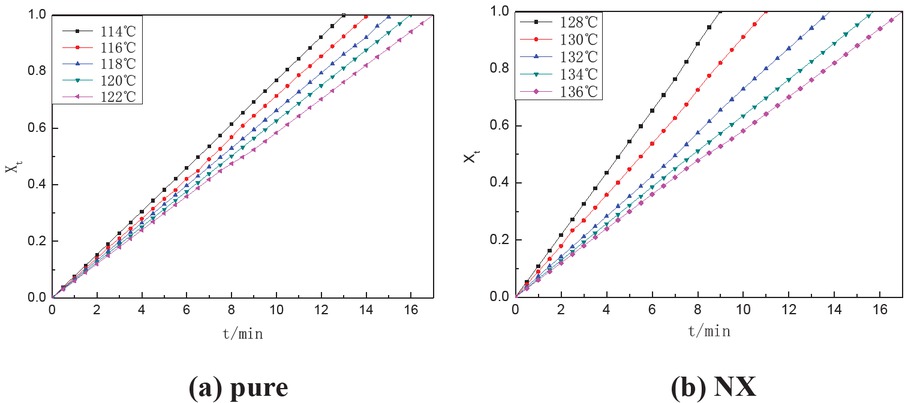

According to isothermal crystallization curve and Eq. 7, the relationships between crystallization time t at different crystallization temperatures and relative crystallinity Xt can be obtained by integrating DSC curves of different nucleating agents modified polypropylene (Figure 6)

Parameters of non-isothermal crystallization kinetics.

| n | lnZt | Zc | Zt/min-n | t1/2/ sec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PP | 1.22 | -0.61 | 0.9403 | 0.5406 | 73.2 |

| NX | 1.13 | -0.23 | 0.9764 | 0.7875 | 53.4 |

| NA | 1.09 | -0.46 | 0.9547 | 0.6288 | 65.4 |

| WA | 1.11 | -0.48 | 0.9527 | 0.6151 | 66.6 |

| MD | 1.29 | -0.55 | 0.9460 | 0.5738 | 69.0 |

Isothermal crystallization relative crystallinity fraction curve.

The crystallization time of modified polypropylene increases with the increase of crystallization temperature, which indicates that the crystallization rate of modified PP decreases gradually. Meanwhile, compared with pure PP, nucleating agent can greatly reduce the semi-crystallization time and increase the crystallization rate of polypropylene, thus shortening the forming and processing period of the product. According to Eq. 5, ln(-ln(1-Xt)) was plotted as shown in Figure 7.

Isothermal crystallization ln (-ln (1-Xt)) on a linear relationship lnt.

There is a good linear relationship between ln(-ln(1-Xt)) and lnt. The rate constants Zt and Avrami exponent n can be obtained from the intercept and slope of the curve, so that Xt = 50%, and the half crystallization time t1/2 can be calculated. The specific numerical values are shown in Table 4.

Isothermal crystallization kinetics parameters.

| Tc/°C | n | lnZt | Zt/min-n | t1/2/sec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PP | 114 | 1.37 | -2.73 | 0.065 | 30.9 |

| 116 | 1.36 | -2.82 | 0.059 | 37.5 | |

| 118 | 1.34 | -2.89 | 0.055 | 43.4 | |

| 120 | 1.30 | -2.92 | 0.054 | 49.4 | |

| 122 | 1.29 | -2.97 | 0.051 | 56.0 | |

| NX | 128 | 1.32 | -2.23 | 0.106 | 17.0 |

| 130 | 1.32 | -2.48 | 0.084 | 24.2 | |

| 132 | 1.33 | -2.77 | 0.062 | 37.3 | |

| 134 | 1.32 | -2.90 | 0.055 | 46.1 | |

| 136 | 1.29 | -2.96 | 0.051 | 56.4 | |

| NA | 128 | 1.38 | -2.40 | 0.090 | 19.1 |

| 130 | 1.33 | -2.73 | 0.065 | 34.6 | |

| 132 | 1.32 | -2.76 | 0.063 | 36.8 | |

| 134 | 1.34 | -2.92 | 0.054 | 44.4 | |

| 136 | 1.29 | -2.98 | 0.051 | 55.7 | |

| WA | 126 | 1.32 | -2.39 | 0.091 | 21.3 |

| 128 | 1.32 | -2.43 | 0.088 | 22.4 | |

| 130 | 1.32 | -2.64 | 0.071 | 31.2 | |

| 132 | 1.30 | -2.82 | 0.059 | 43.3 | |

| 134 | 1.29 | -2.96 | 0.051 | 56.6 | |

| MD | 128 | 1.32 | -2.70 | 0.068 | 33.2 |

| 130 | 1.33 | -2.86 | 0.057 | 42.4 | |

| 132 | 1.32 | -2.95 | 0.052 | 50.4 | |

| 134 | 1.28 | -2.95 | 0.052 | 55.7 | |

Table 4 that Avrami index has little change at different temperatures, indicating that nucleating agent has little effect on the crystallization mode of polypropylene. The crystallization rate constant Z t decreases with the increase of crystallization temperature, which indicates that the crystallization temperature increases, and the growth rate and nucleation rate both decrease. In addition, the addition of nucleating agent shortens the semi-crystallization time, in which the semi-crystallization time of NX-modified polypropylene is 4.12 min, and the kinetic constant Zt value is 0.106, which indicates that NX-nucleating agent has good nucleating effect.

3.4 Effect of nucleating agent on crystallization rate of polypropylene

At present, the crystallization rate is characterized by t1/2 (semi-crystallization time), △Tc (difference between initial

crystallization temperature Tcon and peak temperature Tcp), and S (initial slope of crystallization peak). These three kinetic rate parameters are obtained by DSC test. t1/2 is calculated by avramni equation. According to Figure 3, t1/2, △Tc, S and other parameters are shown in Table 5.

The effect of nucleating agent on polypropylene crystallization rate.

| NO | Type of nucleating agent | Tcon/°C | TcP/°C | △Tc/°C | S | t1/2/sec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pure PP | 125.8 | 115.8 | 10.0 | 0.23 | 73.2 |

| 2 | NX | 135.7 | 129.8 | 5.9 | 0.31 | 53.4 |

| 3 | NA | 134.2 | 127.1 | 7.1 | 0.29 | 65.4 |

| 4 | WA | 133.7 | 125.9 | 7.8 | 0.27 | 66.6 |

| 5 | MD | 129.7 | 120.3 | 9.4 | 0.24 | 69.0 |

△Tc value represents the crystallization rate. The smaller the value is, the faster the crystallization rate goes. From Table 5, the crystallization parameters of the modified

polypropylene such as Tcon, TcP, S values are significantly improved, where the S value represents the initial nucleation rate, and the larger the absolute value is, the faster the crystallization rate goes. By comparison, NX nucleating agent has the best effect on increasing crystallization rate, the △Tc value is the smallest, the S value is the largest, and the semi-crystallization time is the shortest.

3.5 Effect of nucleating agent on crystallization temperature of polypropylene

The melting and crystallization behavior of polypropylene were measured by DSC method. The melting temperature Tm and crystallization temperature Tc of modified PP are shown in Table 6.

The crystallization temperature and melting temperature.

| No | Type of nucleating agent | Tc/°C | Tm/°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pure PP | 115.8 | 165.1 |

| 2 | NX | 129.8 | 166.7 |

| 3 | NA | 127.1 | 165.3 |

| 4 | WA | 125.9 | 166.1 |

| 5 | MD | 120.3 | 165.9 |

Nucleating agents significantly increases the crystallization temperature of polypropylene (Table 6). In addition, because the nucleating agent reduces the nucleation free energy, the polypropylene is crystallized at a high temperature, the crystallization is more perfect, and the crystallization melting point is higher, wherein the nucleating agent NX has better effect on improving the crystallization and melting temperature of the polypropylene.

3.6 Effect of nucleating agent on spherulite size of polypropylene

In order to verify the change of nucleating agent on the spherulite size of polypropylene, the crystal size was characterized by XRD.

The average grain diameter size of each PP and nucleated PP was calculated according to the above Eq. 8 and 9, as shown in Table 7.

X-ray diffraction and calculating spherulite nucleating diameter.

| No | Peak position | Diffraction angle (2θ)/° | half-peak width (β)/° | cos (θ) | crystal grain diameter (D)/nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PP | 1 | 13.98 | 0.32 | 0.992 | 24.34 |

| 2 | 16.77 | 0.54 | 0.989 | 14.66 | |

| 3 | 18.49 | 0.45 | 0.987 | 17.77 | |

| 4 | 21.02 | 0.29 | 0.983 | 27.59 | |

| 5 | 21.75 | 0.53 | 0.982 | 15.01 | |

| Average | 19.87 | ||||

| NX | 1 | 13.96 | 0.58 | 0.992 | 13.66 |

| 2 | 16.75 | 0.47 | 0.989 | 16.94 | |

| 3 | 18.52 | 0.87 | 0.986 | 9.20 | |

| 4 | 21.01 | 0.62 | 0.983 | 12.85 | |

| 5 | 21.76 | 0.55 | 0.982 | 14.68 | |

| Average | 13.47 | ||||

| NA | 1 | 13.92 | 0.69 | 0.992 | 11.58 |

| 2 | 16.73 | 0.41 | 0.989 | 19.21 | |

| 3 | 18.54 | 0.79 | 0.986 | 10.15 | |

| 4 | 21.00 | 0.30 | 0.983 | 26.59 | |

| 5 | 21.71 | 0.64 | 0.982 | 12.56 | |

| Average | 16.02 | ||||

| WA | 1 | 13.92 | 0.70 | 0.992 | 11.34 |

| 2 | 16.73 | 0.44 | 0.989 | 18.01 | |

| 3 | 18.51 | 0.68 | 0.986 | 11.74 | |

| 4 | 21.00 | 0.31 | 0.983 | 25.50 | |

| 5 | 21.68 | 0.68 | 0.982 | 11.86 | |

| Average | 15.69 | ||||

| MD | 1 | 14.24 | 1.76 | 0.992 | 4.54 |

| 2 | 15.89 | 0.34 | 0.990 | 23.12 | |

| 3 | 16.72 | 0.41 | 0.989 | 19.17 | |

| 4 | 20.96 | 0.33 | 0.983 | 23.91 | |

| Average | 17.69 | ||||

Nucleating agent can change the spherulite size of polypropylene, increase the crystallization rate and decrease the spherulite size.

According to Eq. 10, crystal nucleus density of polypropylene were calculated, as shown in Table 8.

Nucleated PP spherulite size and nucleation density.

| No | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of nucleating agent | Pure PP | NX | NA | WA | MD |

| Spherulite size /nm | 87.59 | 40.36 | 57.22 | 66.55 | 75.69 |

| Crystal nucleus density × 1012/cm-3 | 2.84 | 29.06 | 10.19 | 6.48 | 4.40 |

From Table 8 (nucleated PP spherulite size and nucleation density), we can see the crystal nucleus density of the modified polypropylene increases and

the spherulite size decreases. The nucleating agent NX modified polypropylene has the smallest spherulite size and the largest crystal nucleus density, which indicates that the nucleating effect is the best.

4 Conclusions

Different kinds of nucleating agents have great influence on the crystallization kinetics, the crystalline morphology and crystallinity of polypropylene. Since NX nucleating agent structure is similar to the size of the propylene, the crystallization time and crystallization temperature of polypropylene reach the highest, 53.4 seconds and 129.8°C respectively. At the same time, nucleating agent significantly reduces the nucleation free energy of polypropylene and the sperodidal size, and promotes the high temperature crystallization of polypropylene. According to XRD calculation, NX nucleating agent is the best, and the spherulite size is the smallest, which is 40.36 nm.

References

1 Mathieu C., Thierry A., Wittmann J.C., Lotz B., “Multiple” nucleation of the (010) contact face of isotactic polypropylene, α phase. Polymer, 2000, 41(19), 7241-7253.10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00062-8Suche in Google Scholar

2 Stocker W., Schumacher M., Graff S., Thierry A., Wittmann J.C., Lotz B., Epitaxial crystallization and AFM investigation of a frustrated polymer structure: Isotactic poly(propylene), β-phase. Macromolecules, 1998, 31(3), 807-814.10.1021/ma971345dSuche in Google Scholar

3 Dorset D.L., McCourt M.P., Kopp S., Schumacher M., Okihara T., Lotz B., Isotactic polypropylene, β-phase: A study in frustration. Polymer, 1998, 39(25), 6331-6337.10.1016/S0032-3861(97)10160-4Suche in Google Scholar

4 Thierry A., Straupe C., Lotz B., Wittmann J.C., Physical gelation: Apath towards ideal dispersion of additives in polymers. Polym Commun, 1990, 31(8), 299-301.Suche in Google Scholar

5 Fillon B., Lotz B., Thierry A., Wittmann J.C., Self-nucleation andenhanced nucleation of polymers. Definition of a convenientcalorimetric “efficiency scale” and evaluation of nucleatingadditives in isotactic polypropylene(αphase). J Polym Sci Pol Phys, 1993, 31(10), 1395-1405.10.1002/polb.1993.090311014Suche in Google Scholar

6 Xu Z.Q., Influence of α-nucleating agents on crystallization behavior of ultra-high impact polypropylene and its composites. Plastics Science and Technology, 2016, 44(2), 21-24.Suche in Google Scholar

7 Qian W., Guo S.H., Wang J.Q., et al., Preparation of imide β-nucleating agent and effect on properties of polypropylene. Plastics, 2016, 45(2), 30-33.Suche in Google Scholar

8 Papageorgiou D.G., Chrissafis K., Bikiaris D.N., β-Nucleated polypropylene processing properties and nanocomposites. Polym Rev, 2015, 55, 1-34.10.1080/15583724.2015.1019136Suche in Google Scholar

9 Zhang X.L., Zhang P.S., Zhu B.C., et al., Research progress in the β nucleating agent for potypropylene. China Synthetic Resin and Plastics, 2015, 32(5), 68-76.10.1002/iub.1455Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Dou G.R., Dou Q., Melting crystallization behaviors and mechanical properties of IPP modified by β nucleating agents. Modern Plastics Processing and Applications, 2015, 27(2), 39-42.Suche in Google Scholar

11 Huo H., Jiang S., An L., Influence of shear on crystallization behavior of the β phase in isotactic polypropylene with β-nucleating agent. Macromolecules, 2004, 37, 2478-2483.10.1021/ma0358531Suche in Google Scholar

12 Song S., Feng J., Wu P., Yang Y., Shear-enhanced crystallization in impact-resistant polypropylene copolymer: influence of compositional heterogeneity and phase structure. Macromolecules, 2009, 42, 7067-7078.10.1021/ma9004764Suche in Google Scholar

13 Kristiansen M., Werner M., Tervoort T., Smith P., The binary system isotactic polypropylene/bis(3,4-dimethylbenzylidene) sorbitol: phase behavior, nucleation, and optical properties. Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 5150-5156.10.1021/ma030146tSuche in Google Scholar

14 Wang S.C., Zhang J., Effect of nucleating agent on the crystallization behavior, crystal form and solar reflectance of polypropylene. Sol Energ Mater Sol C, 2013, 117, 577-584.10.1016/j.solmat.2013.07.033Suche in Google Scholar

15 Zhang X.J., Zhang D., Liu T., Influence of Nucleating Agent on Properties of Isotactic Polypropylene. Energy Proced, 2012, 17(B), 1829-1835.10.1016/j.egypro.2012.02.319Suche in Google Scholar

16 Gomes Simanke A., de Azeredo A.P., de Lemos C., Santos Mauler R., Influence of nucleating agent on the crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene. Polímeros, 2016, 26(2), 1678-5169.10.1590/0104-1428.2053Suche in Google Scholar

17 Dolgopolsky I., Silberman A., Kenig S., The effect of nucleating-agents on the crystallization kinetics of polypropylene. Polymer for Advanced Technologies, 1995, 6(10), 653-661.10.1002/pat.1995.220061003Suche in Google Scholar

18 Blanco I., Abate L., Antonelli M.L., The regression of isothermal thermogravimetric data to evaluate degradation Ea values of polymers: A comparison with literature methods and an evaluation of lifetime prediction reliability. Polym Degrad Stabil, 2011, 96(11), 1947-1954.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2011.08.005Suche in Google Scholar

19 Supaphol P., Charoenphol P., Junkasem J., Effect of nucleating agents on crystallization and melting behavior and mechanical properties of nucleated syndiotactic poly(propylene). Macromol Mater Eng, 2004, 289(9), 818-827.10.1002/mame.200400102Suche in Google Scholar

20 Deyan S., Application of infrared spectroscopy in polymer research. Beijing Science Press, 1982, 163-165.Suche in Google Scholar

21 Xingrong Z., Polymer modern test and analysis technology. Guangzhou South China University of Technology Press, 2007, 295-296.Suche in Google Scholar

22 Bu H.S., Wunderlich B., et al., Macromol Chem Rapid Commun, 1988, 76.Suche in Google Scholar

23 Jeziorny A., Parameters characterizing the kinetics of the nonisothermal crystallization of poly(ethylene terephthalate) determined by d.s.c. Polymer, 1978, 19, 1142.10.1016/0032-3861(78)90060-5Suche in Google Scholar

24 Xu X.R., Xu J.T., Chen L.S., Liu R.W., Feng L.X., Nonisothermal crystallization kinetics of ethylene-butene copolymer/ low-density polyethylene blends. J Appl Polym Sci, 2001, 80, 124.10.1002/1097-4628(20010411)80:2<123::AID-APP1080>3.0.CO;2-FSuche in Google Scholar

25 Avrami M., Kinetics of Phase Change I General Theory. J Chem Phys, 1939, 7, 1103-1112.10.1063/1.1750380Suche in Google Scholar

26 Avrami M., Kinetics of phase change II Transformation-timerelations for random distribution of nuclei melvin avrami. J Chem Phys, 1940, 8, 212-224.10.1063/1.1750631Suche in Google Scholar

27 Avrami M., Kinetics of Phase Change III Phase change and microstructure. J Chem Phys, 1941, 9, 177-184.10.1063/1.1750872Suche in Google Scholar

28 Williamson G.K., Hall W.H., X-Ray Line Broa Dening from Filed Aluminium and Wolfram. Acta Metall, 1953, 1, 22-31.10.1016/0001-6160(53)90006-6Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 An et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die