Abstract

Fermentation of hyaluronan (HA) by Streptococcus zooepidemicus was carried out in a 10-L fermentor. When the medium pH was controlled at 7.0 and the temperature was maintained at 38°C for 12 h followed by 35°C for 8 h, the yield of HA was 4.83 g/L with a molecular weight of 1,890 kDa. After the cells were removed by centrifugation from the fermentation broth, HA was slowly degraded to low molecular weight HA by hyaluronidase at a suitable temperature without a decrease in HA concentration. If the time and temperature for enzymatic degradation were controlled, the desired low molecular weight HA could be obtained by in situ degradation in the fermentation broth. The method does not require the addition of exogenous hyaluronidase, and is a simple way to produce low molecular weight HA.

1 Introduction

Hyaluronan (HA) has a wide range of applications in the fields of medicine and cosmetics, including osteoarthritis treatment, ophthalmic surgery, plastic surgery, drug delivery, skin moisturizers, and wound healing (1,2). Depending on its molecular weight, HA may be used in different applications. HA with high molecular weight (> 2,000 kDa) is usually applied in the pharmaceutical field while HA with low molecular weight (< 1,000 kDa) is generally applied in the cosmetics and food industries (3). Generally, the molecular weight of HA extracted from rooster comb can be as high as 5,000-6,000 kDa, and is between 500 and 2,000 kDa from microbial fermentation (4). In recent years, the demand for low molecular weight HA has increased because of its widespread use in cosmetics.

At present, low molecular weight HA is primarily obtained by hydrolyzing macromolecular HA by physical, chemical, and enzymatic degradation. Physical degradation usually involves heating, mechanical shearing, γ-ray irradiation, ultrasonication and/or ultraviolet treatment. Chemical degradation agents are divided into those that function by acidic or alkaline hydrolysis and those that function by oxidant hydrolysis. Enzymatic degradation is mainly through the action of hyaluronidase (5). Generally, enzymatic degradation has advantages of high efficiency, specificity for substrates within a narrow range of molecular weights and mild reaction conditions. However, application of commercial hyaluronidase extracted from bovine testes (6) or recombinant leech hyaluronidase (7) for enzymatic production of low molecular weight HA has some disadvantages, such as a high price and a requirement for complex manipulation, which have limited its industrial applications (8).

Microbial fermentation has gradually become the main method of HA production (9,10). In the HA fermentation process, we observed that after the HA concentration reached a maximum value, if the cultivation time was extended longer, the concentration and molecular weight of HA both decreased because of the hyaluronidase originating from the bacterial cells. Other studies have found the same phenomenon (11, 12, 13). This supports the idea that preparation of low molecular weight HA can be achieved by hyaluronidase hydrolysis in fermentation broth. This method would not require additional hyaluronidase and thus, would avoid the need for costly enzyme in the production of low molecular weight HA.

2 Experimental

2.1 Microorganism and media

Streptococcus zooepidemicus GDMCC 60146 (stored at Guangdong Microbial Culture Center, Guangdong, China) was used in this study. It was obtained from the wild strain GIM 1.437 after UV and γ-ray mutation.

Fresh slants were cultured at 37°C for 12 h and used for inoculation. Seed culture medium contained 2.0 g/L glucose, 5.0 g/L beef extract, 5.0 g/L peptone, 2.0 g/L yeast extract, 2.5 g/L K2HPO4, and 1.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O at pH 7.0. The fermentation medium contained 13.8 g/L glucose, 11.2 g/L beef extract, 10.4 g/L peptone, 4 g/L yeast extract, 4.5 g/L K2HPO4, 2.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, and 0.5 g/L antifoaming agent.

2.2 Batch fermentation in a 10-L fermentor

A total of 120 mL of the seed culture was inoculated into a 10-L aeration-agitation type fermentor (Model FUS-10L, Shanghai Guoqiang Bioengineering Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) containing 6.0 L of fermentation medium. Agitation was supplied by two four-bladed disk turbines at a speed of 300-500 r/min, and the aeration rate was 0.6-1.0 v/v·min. Dissolved oxygen saturation (DO) was maintained at ≥50% by adjusting the agitation speed or aeration rate. The pH was automatically controlled at 7.0 by adding a 2 mol/L NaOH solution. The temperature was maintained at 38°C for 12 h, and then was maintained at 35°C until the end of fermentation.

2.3 Determination of the concentration and molecular weight of HA

The fermentation broth was diluted with an equal volume of 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 10 min to free the capsular HA and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min to pellet the HA-free cells. The supernatant was used to estimate the concentration and molecular weight of HA. The pellet was washed with 0.85% NaCl solution twice and weighed after drying at 105°C.

HA in the supernatant was precipitated with five volumes of ethanol and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 5000×g for 10 min, and then re-dissolved in an equal volume of distilled water. These steps were repeated three times. The concentration of HA was measured using the modified carbazole method (14). The molecular weight of HA was determined according to the viscosity method developed by Laurent (15).

2.4 Measurement of hyaluronidase activity

Hyaluronidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically using a turbidity reduction assay (16). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that reduced the absorbance by 0.1 at 600 nm in 30 min at 37°C, pH 7.0.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effects of temperature on HA fermentation

After Streptococcus zooepidemicus GDMCC 60146 was cultured in the fermentation medium at 38°C for 12 h, the temperature was lowered to 33°C, 34°C, 35°C, 36°C and 37°C. After cultivation continued for 8 h, the results of the concentration and molecular weight determination of HA are shown in Figure 1.

Changes in the concentration and molecular weight of hyaluronan when the temperature was lowered in the second stage of the fermentation. ■ HA concentration, ▴ molecular weight of HA. HA = hyaluronan; MW = molecular weight.

As shown in Figure 1, a high concentration and molecular weight of HA was obtained when the temperature of fermentation in the second stage was lowered to 35°C. If the fermentation temperature was kept constant at 38°C, the molecular weight of HA was generally less than 1,000 kDa, much lower than that obtained by varying the temperature of the fermentation. To obtain a high yield of HA with a relatively high molecular weight, isothermal fermentation temperature was preferred for the fermentation.

3.2 Effects of pH on HA fermentation

During the fermentation of HA, the medium pH drops quickly due to the synthesis of lactic acid, which is related to oxygen deprivation because of fast cell growth (13). Low pH is disadvantageous to the cell growth and HA synthesis. 2 mol/L NaOH was added to control the medium pH to 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5 and 8.0. The results of the concentration and molecular weight determination of HA under varying pH are shown in Figure 2.

Changes in the concentration and molecular weight of hyaluronan when the medium pH was controlled at different pH values. ■ HA concentration, ▴ molecular weight of HA. HA = hyaluronan; MW = molecular weight.

As shown in Figure 2, low pH was not suitable to increase the concentration and molecular weight of HA, and high pH is not suitable to increase the concentration of HA, but suitable to increase the molecular weight of HA. The highest concentration and molecular weight of HA were obtained when the medium pH was controlled at 7.0. To obtain a high molecular weight HA, the optimal medium pH should be controlled at 7.0 throughout the entire fermentation process.

3.3 Batch fermentation of HA in a 10-L fermentor

The results of batch fermentation of HA in a 10-L fermentor by GDMCC 60146 are shown in Figure 3. As illustrated in Figure 3, the cells started exponential growth after about 6 h of the lag phase and the biomass reached the highest value of 7.88 g/L at 18 h. After 20 h, the biomass began to decrease a little. The synthesis of HA was almost simultaneous with cell growth and its concentration reached the maximum at 20 h, about 2 h later than the time the maximum biomass appeared. Under a constant pH of 7.0 and isothermal conditions, 4.83 g/L of HA was obtained with an average molecular weight of 1,890 kDa in the batch fermentation carried out in 10-L fermentor.

Time course of hyaluronan concentration and biomass in the batch fermentation of HA by S. zooepidemicus GDMCC 60146. ■ HA concentration, ♦ biomass. HA = hyaluronan.

Enzymatic measurement of the cell lysates and the culture supernatants revealed that 23.2 U/mL of the total activity was associated with the cell pellet, and 61.5 U/mL of the total activity was in the culture supernatant accounting for 27.4% and 72.6% of the total activity, respectively. The enzyme distribution was different from Allen’s research (17), in which all of the hyaluronidase activity from Streptococcus suis was in the culture supernatant. These differences may be explained by the fact that different strains vary in the way they secrete enzymes.

3.4 Production of low molecular weight HA by hyaluronidase degradation

HA in the fermentation broth can be hydrolyzed by hyaluronidase from cells and the supernatant. The

concentration and molecular weight of HA in the fermentation broth containing cells and supernatant changed over time as shown in Figure 4. Both the concentration and molecular weight of HA in the fermentation broth containing cells decreased rapidly after incubation at 37°C. In contrast, after removing the cells by centrifugation, the hydrolysis rate of HA was much slower than that without centrifugation. Within 72 h, the concentration of HA in the supernatant did not significantly decrease, but the molecular weight of HA gradually decreased to a low of 125 kDa.

Changes in the concentration and molecular weight of hyaluronan. ● HA concentration in the fermentation broth with cells, ○ HA concentration in the fermentation broth without cells, ♦ molecular weight of HA in the fermentation broth with cells, ◊ molecular weight of HA in the fermentation broth without cells. HA = hyaluronan; MW = molecular weight.

Although the hyaluronidase carried by the cells was only about one third of the total enzyme activity, the removal of cells not only removed some enzymes, but also stopped the regeneration of the enzyme when the cells were incubated in the nutrient containing fermentation broth at 37°C. The degradation of HA involves two steps. First, it is degraded into short-chain HA and then in the second step, it is degraded into monosaccharide units. Under the conditions of low enzyme activity and limited time, HA was not completely degraded, resulting in low molecular weight HA.

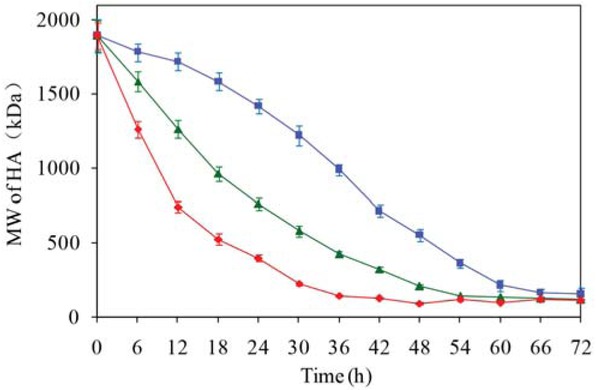

After centrifugation, the pH of the supernatant was about 7.0, and the activity of hyaluronidase was about 60 U/mL. Under this condition, temperature is the key factor that affects the rate of enzymatic degradation. As shown in Figure 5, with the decrease of temperature, the rate of HA degradation decreased accordingly. This suggested that choice of an appropriate low temperature for enzymatic degradation will allow the preparation of low molecular weight HA to be more controllable.

Changes in the molecular weight of hyaluronan in the fermentation supernatant incubated at different temperatures. ■ 34°C, ▴ 37°C, ♦ 40°C. HA = hyaluronan; MW = molecular weight.

4 Conclusions

In the batch fermentation, using a constant pH of 7.0, a temperature of 38°C for 12 h followed by a temperature of 35°C for 8 h, a high yield of HA with a relatively high molecular weight was obtained. After the cells were removed by centrifugation from the fermentation broth, the hyaluronidase activity in the supernatant was about 60 U/mL, and HA was slowly degraded to low molecular weight HA by hyaluronidase at a suitable temperature without a significant decrease of HA concentration. If the time and temperature for enzymatic degradation are controlled, the desired low molecular weight HA can be obtained by in situ degradation. The method does not require the exogenous addition of hyaluronidase and is a simple way to produce low molecular weight HA.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Zhejiang Food and Drug Administration, China (Grant No. 2018014). We thank Renee Mosi, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China, for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

References

1 Robert L., Hyaluronan, a truly “youthful” polysaccharide. Its medical applications. Pathol. Biol., 2015, 63, 32-34.10.1016/j.patbio.2014.05.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Bukhari S.N.A., Roswandi N.L., Waqas M., Habib H., Hussain F., Khan S., et al., Hyaluronic acid, a promising skin rejuvenating biomedicine: A review of recent updates and pre-clinical and clinical investigations on cosmetic and nutricosmetic effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2018, 120, 1682-1695.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.188Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Ferguson E.L., Roberts J.L., Moseley R., Griffiths P.C., Thomas D.W., Evaluation of the physical and biological properties of hyaluronan and hyaluronan fragments. Int. J. Pharmaceut., 2011, 420, 84-92.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Marcellin E., Steen J.A., Nielsen L.K., Insight into hyaluronic acid molecular weight control. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2014, 98, 6947-6956.10.1007/s00253-014-5853-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

5 Stern R., Kogan G., Jedrzejas M.J., Soltes L., The many ways to cleave hyaluronan. Biotechnol. Adv., 2007, 25, 537-557.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.07.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Chen F., Kakizaki I., Yamaguchi M., Kojima K., Takagaki K., Endo M., Novel products in hyaluronan digested by bovine testicular hyaluronidase. Glycoconj. J., 2009, 26, 559-566.10.1007/s10719-008-9200-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Yuan P.H., Lv M.X., Jin P., Wang M., Du G.H., Chen J., et al., Enzymatic production of specifically distributed hyaluronan oligosaccharides. Carbohyd. Polym., 2015, 129, 194-200.10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.04.068Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8 El-Safory N.S., Fazary A.E., Lee C.K., Hyaluronidases, a group of glycosidases: Current and future perspectives. Carbohyd. Polym., 2010, 81, 165-181.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.02.047Search in Google Scholar

9 Liu L., Liu Y.F., Li J.H., Du G.C., Chen J., Microbial production of hyaluronic acid: current state, challenges, and perspectives. Microb. Cell. Fact., 2011, 10, 99.10.1186/1475-2859-10-99Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Sze J.H., Brownlie J.C., Love C.A., Biotechnological production of hyaluronic acid: a mini review. 3 Biotech., 2016, 6, 67.10.1007/s13205-016-0379-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11 Huang W.C., Chen S.J., Chen T.L., Production of hyaluronic acid by repeated batch fermentation. Biochem. Eng. J., 2008, 40, 460-464.10.1016/j.bej.2008.01.021Search in Google Scholar

12 Don M.M., Shoparwe N.F., Kinetics of hyaluronic acid production by Streptococcus zooepidemicus considering the effect of glucose. Biochem. Eng. J., 2010, 49, 95-103.10.1016/j.bej.2009.12.001Search in Google Scholar

13 Liu L., Wang M., Du G., Chen J., Enhanced hyaluronic acid production of Streptococcus zooepidemicus by an intermittent alkaline-stress strategy. Lett. Appl. Microbiol., 2008, 46, 383-388.10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02325.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Bitter T., Muir H.M., A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal. Biochem., 1962, 4, 330-334.10.1016/0003-2697(62)90095-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Laurent T.C., Ryan M., Pietruszkiewicz A., Fractionation of hyaluronic acid the polydispersity of hyaluronic acid from the bovine vitreous body. BBA-Bioenergetics, 1960, 42, 476-485.10.1016/0006-3002(60)90826-XSearch in Google Scholar

16 Sahoo S., Panda P.K., Mishra S.R., Nayak A., Dash S.K., Ellaiah P., Optimization of physical and nutritional parameters for hyaluronidase production by Streptococcus mitis Indian J. Pharm. Sci., 2008, 70, 661-664.10.4103/0250-474X.45412Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Allen A.G., Lindsay H., Seilly D., Bolitho S., Peters S.E., Maskell D.J., Identification and characterisation of hyaluronate lyase from Streptococcus suis Microb. Pathogenesis, 2004, 36, 327-335.10.1016/j.micpath.2004.02.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Mei et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die