Abstract

In order to improve the compatibility of flame retardant and epoxy resin, a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent poly(p-xylylenediamine spirocyclic pentaerythritol bisphosphonate) (PPXSPB) was synthesized. FTIR, 1HNMR, and mass spectroscopy were used to identify the chemical structure of PPXSPB. Epoxy resin (E-44) and PPXSPB as the raw material, a series of thermosetting systems were prepared. The effects of PPXSPB on flame retardancy, water resistance, thermal degradation behavior, mechanical properties and the adhesive strength of EP/PPXSPB thermosets were investigated. The results show that with the increase of phosphorus content, the oxygen index and carbon residue of the system both increased significantly, and the heat release rate gradually decreased, which is of great significance in delaying the occurrence of fire. When the phosphorus content is 3.24% in EP/PPXSPB thermosets, EP-2 can successfully pass the UL94 V-0 flammability rating, the LOI value of EP-2 can reach 31.4%, the impact strength and tensile strength was 6.58 kJ/m2 and 47.10 MPa respectively, and the adhesive strength was 13.79 MPa, the system presents a good overall performance.

1 Introduction

Epoxy resin has excellent mechanical properties, electrical properties, bonding properties and so on. So many advantages make it widely used in the electrical and electronic, construction, chemicals, machinery, transportation, national defense construction, aerospace, optical instruments, sports equipment, and many other areas. In terms of its practical application, the epoxy resin is required to have better flame retardant properties, which have improved the development of the flame retardant epoxy resin (1, 2, 3).

Nowadays, the method of adding flame retardant by physical blending has still been widely used as its easy operation and low cost. Its flame retardant effects lessen rapidly as time passes by, especially in harsh environments, and because it is added as filler, it will have a certain impact on the mechanical properties of the material. Therefore, another method that incorporates flame retardant elements (P, N, Si, B, etc.) into polymer backbone or network chemical bonding is being extensively studied (4, 5, 6, 7). Phosphorus-containing flame retardant curing agents, a part of reactive flame retardant, have drawn people’s attention due to their advantages that they are halogen-free, low in toxicity and relatively efficient. There are many possibilities for phosphorus-containing chemical structures to be modified to adjust their different properties, such as ammonium polyphosphate (APP), 9,10-dihydro-9-oxa-10-phosphaphenanthrene-10-oxide (DOPO), which are used as an intermediate in phosphorus-containing flame retardants. Many different flame retardants have been synthesized, most of which have good flame retardancy (8, 9, 10, 11).

Phosphorus and nitrogen have been confirmed to have a synergistic effect during the burning process, which can improve the flame retardant effect (12, 13, 14). Thus a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent was synthesized in this study, where the nitrogen in the form of amino groups is used as crosslinking groups, and a series of flame retardant epoxy resin systems were prepared. The flame retardancy of EP/PPXSPB thermosets was investigated by limiting oxygen index (LOI) and vertical burning test (UL94), the thermal degradation behavior was tested by thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), and the mechanical properties were investigated by tensile strength and charpy impact strength tests and adhesive strength tests, respectively, and the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analysis the impact sections morphologies of EP/PPXSPB thermosets from impact tests and the char residues morphologies of the EP/PPXSPB thermosets.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

P-xylylenediamine (PXDA, chemically pure) were purchased from Shandong Xiya Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China), phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3, analytical reagent (AR)), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, AR), Pentaerythritol (PER, AR), acetonitrile (AR), chlorobenzene (AR), and dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, AR) were all purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The EP resin (bisphenol A diglycidyl ether, trade name E-44, EP equivalent = 210-240 g/eq) was purchased from Jinan Zhuopu Chemical Technology Co., Ltd (Jinan, China).

2.2 Synthesis

2.2.1 Synthesis of the SPDPC (pentaerythritol diphosphate diphosphoryl chloride)

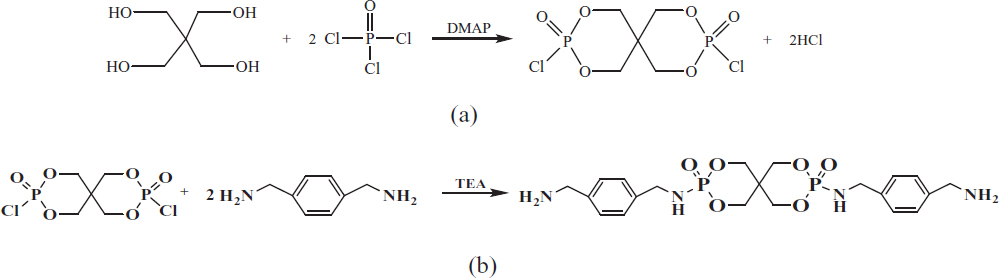

PER (13.61 g, 0.10 mol), POCl3 (46.01 g, 0.30 mol), and chlorobenzene (150 mL) were introduced into a 500 mL, three-neck and round-bottom glass flask equipped with a condenser, a dry N2 inlet, a thermometer, a magnetic stirrer, and a gas absorber. DMAP (0.13 g, 0.0011 mol) as catalyst was also added into the glass flask. The mixture was stirred at 60°C for 2 h and 80°C for 6 h. Then mixture continued to react at 95°C until no large amount of HCl gas was spilled over. All reactions were carried out under dry N2 atmosphere. The crude product was washed with CH2Cl2 and ethanol sequentially, and then dried it at 80°C for 12 h under vacuum until its quality does not change. The obtained white solid powder was SPDPC. Yield: 26.34 g (88.9%). Scheme 1a is the reaction formula.

2.2.2 Synthesis of the PPXSPB

PXDA (57.20 g, 0.42 mol) and acetonitrile (230 mL) were introduced into a 500 mL four-neck and round-bottom glass flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, reflux condenser, thermometer, and dry nitrogen inlet. The mixture was heated to 60°C under N2 atmosphere and stirred until PXDA dissolved completely. Then SPDPC (59.18 g, 0.2 mol) was added. The reaction was stirred under 60°C for 2 h. Then the reaction continued at 75°C for 6 h. The mixture was filtered hot to remove excessive PXDA and acetonitrile, the crude product was washed successively for 3 times with acetonitrile, and then vacuum-dried at 70°C for 12 h, and PPXSPB was the obtained white powder. Yield: 86.3 g (87.0%). Scheme 1b is the reaction formula.

2.3 Preparation of flame-retarded EP resin

PXDA was used as a pure sample curing agent which was used to compare with the flame retardant curing agent PPXSPB. The curing process of all flame retardant epoxy resin composites was under the same conditions. The mass ratios of all components are listed in Table 1. The mixture was stirred continuously by high speed disperser for 20 min at 90°C. When the mixture was mixed well, degassed it under vacuum for 30 min, then the mixture was poured into a preheated mold at 119°C. The samples were cured for 2 h at 119°C, 3 h at 146°C and then post-cured for 2 h at 178°C.

EP/PPXSPB flame retardant systems.

| Sample | E-44 (g) | PPXSPB (g) | PXDA (g) | P (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-0 | 100 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| EP-1 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 2.77 |

| EP-2 | 100 | 35 | 0 | 3.12 |

| EP-3 | 100 | 40 | 0 | 3.42 |

Note: The phosphorus content is calculated as: “P% = (PPXSPB mass / total mass of the system) × 12.01 wt% × 100%’’. (12% is the mass fraction of P in the PMXSPB, and phosphorus content is determined by ammonium molybdate spectrophotometric method)

Synthesis route of SPDPC (a) and PPXSPB (b).

2.4 Characterization

Phosphorus content was determined by 721 digitally visible spectrophotometer (Sanghai Jinghua, China) according to the GB/T11893-89, potassium persulfate was used as the oxidant to digest the solid sample.

FTIR analysis was performed using a Thermo Nicolet NEXUS-470 (Ramsey, Minnesota, USA) spectrometer by an attenuated total reflectance method. Each sample was scanned from 4000 to 400 cm−1.

1HNMR spectra and 31PNMR were recorded on an AVANCE III 500MHz spectrometer (Bruker, Switzerland). The chemical shifts relative to that of DMSO-d6 were recorded.

The molecular weight was determined by micrOTOF-Q 125 (Bruker Customer, Germany), with the sample dissolved in methanol.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were performed on a STA449C/41G thermal analyzer (NETZSCH, Germany). The mass of PPXSPB was 5 mg, and EP-0, EP-1, EP-2, EP-3 were the same, 4.5 mg. Each sample was tested from 30 to 800°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min under N2 or air atmosphere.

The limiting oxygen index (LOI) is used to indicate the concentration (volume fraction) of oxygen in a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen when it is just capable of supporting its combustion. LOI test was carried out according to the GB/T2406-1993. The LOI was measured using a JF-3 LOI chamber (Jiangning Analytical Instrument Factory, Nanjing, China), and according to the ASTM D2863 standard, the sample dimensions were 130 × 6.5 × 3.0 mm3.

The vertical burning tests (UL94) were measured by a CZF-3 instrument (Jiangning Analytical Instrument Factory, Nanjing, China), and according to the ASTM D3801 testing procedure, the sample dimensions were 130 × 13.0 × 3.0 mm3. The vertical burning categories are shown in Table 2 according to EN 60695-11-10:1999.

Vertical burning categories.

| Criteria | Category (see note) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| V-0 | V-1 | V-2 | |

| Individual test specimen afterflame time (t1 and t2) | ≤ 10s | ≤ 30s | ≤ 30s |

| Total set afterflame time tf for any conditioning | ≤ 50s | ≤ 250s | ≤ 250s |

| Individual test specimen afterflame plus afterglow time after the second application(t2+t3) | ≤ 30s | ≤ 60s | ≤ 60s |

| Did the afterflame and/or afterglow progress up to the holding clamp? | No | No | No |

| Was the cotton indicator pad ignited by flaming particles or drops? | No | No | Yes |

Note: If the test results are not in accordance with the specified criteria, the material cannot be categorized by this test method. Use the horizontal burning test method described in clause 8 to categorize the burning behavior of material.

For each set of five test specimens from the two conditional treatments, calculate the total afterflame time for the set tf in seconds, using the following equation:

where:

tf – the total afterflame time, in seconds;

t1,i – the first afterflame, in seconds, of the ith test specimen;

t2,i – the second afterflame, in seconds, of the ith test specimen.

The standard sample for LOI and vertical burning was dried to constant weight at 70°C, weighed and recorded as W0; it was placed in distilled water at 70°C for 168 h, and dried it at 70°C to constant weight, recorded as W1. The immersed samples were subjected to LOI and vertical burning tests. The mobility of the flame retardant in EP/PPXSPB flame retardant systems is calculated according to the formula:

Cone calorimeter test was carried out according to the ISO 5660-1 standard on a FTT cone calorimeter (Fire Testing Technology Co. Ltd. UK). Specimens with sheet dimensions of 100 × 100 × 3.0 mm3 were irradiated at a heat flux of 35 kW/ m2. Each sample was tested at least twice.

The tensile strength tests were performed according to the International Organization for Standardization ISO 527-2 standards using a TCS-2000 electric tensile tester (Gotech testing machines Inc., Taiwan), and the tests were performed at a speed of 10 mm‧min-1 at room temperature. Charpy impact tests were performed according to ISO 179-1 standard using a GT-7045-MDL Charpy impact tester (Taiwan). All of the listed results are the mean of five samples. The dumbbell sample dimension of tensile tests was 200 mm × 20 mm × 4 mm, and the size of the stretched part is 60 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm. The sample dimension of charpy impact tests was 80 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) testing by an S-3400N instrument (Hitachi, Japan) was used to investigate the combustion residues of burned samples from cone calorimeter tests.

The adhesive strength tests were performed according to GB/T 7124-2008 using electronic universal testing machine RGD-5 (Shenzhen, China). The stretching rate was 10 mm/min, Iron substrate 100 mm × 25 mm × 5 mm, sizing area of 12.5 mm × 25 mm, curing conditions of 119°C/2 h + 146°C/2 h + 178°C/2 h. The data was taken as the mean of five samples.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural characterization

The structure of PPXSPB was characterized by FTIR, 1HNMR, and mass spectroscopy. Figure 1 was the FTIR spectra of SPDPC and PPXSPB, as is shown in spectra of PPXSPB, the absorption peak of P=O appears at 1245 cm−1, 1022 cm−1 and 1074 cm−1 are the absorption peaks of P–O–C and P–N (15), respectively. Compared with SPDPC, the spectrum of PPXSPB shows the absorption peaks at 3380 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration absorptions of –NH2. The absorption peak at 838 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibration absorptions of –Ph. The absorption peaks at 1598 cm−1 is assigned to the variable angle vibration of –NH (16), and the absorption peak of P=Cl at 547 cm−1 disappeared.

FTIR spectra of SPDPC and PPXSPB.

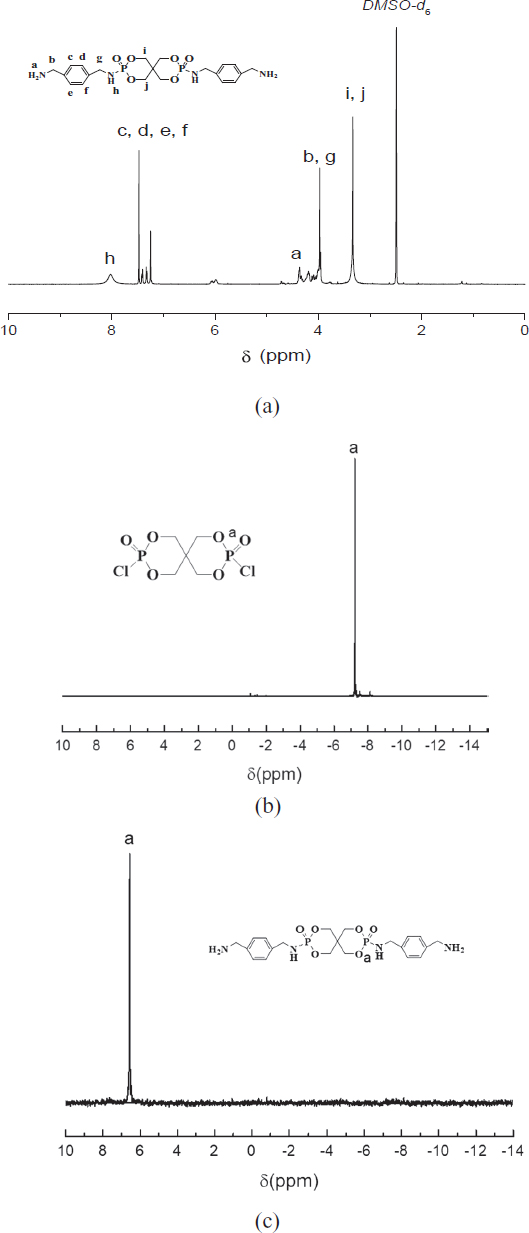

Figure 2 was the 1HNMR (a) and 31PNMR (c) spectra of PPXSPB and the 31PNMR (b) spectrum of SPDPC. As is shown in Figure 2a, the signal at 2.50 ppm is attributed to the DMSO-d6 protons. The chemical shift of protons (b), (g) of methylene between –NH2 and the aromatic ring is at 3.9 ppm, and methylene proton adjacent to P–O can be observed at 3.34 ppm. The chemical shifts of –NH2 adjacent to the aromatic ring is at 4.22 ppm, the chemical shifts of the protons (c), (d), (e) and (f) of the aromatic ring were observed at 7.15-7.56 ppm. The protons (h) of –NH between –P=O and the aromatic ring is shown at 8.07 ppm. The 31PNMR is shown in Figure 2c, the signal at 6.45 ppm is attributed to the P proton, compared with Figure 2b, the signal at 6.45 ppm disappeared, which proves that SPDPC has completely reacted.

1HNMR (a) and 31PNMR (c) spectra of PPXSPB and 31PNMR (b) spectra of SPDPC.

Mass spectrum of PPXSPB.

The mass spectrum of PPXSPB is shown in Figure 3. The m/z values 232.1, 429.1, 497.2, 609.1, 789.2 are correspond to 1/13 M8H+, 1/2M2H+, MH+, 1/2 M3H+, 1/2M4H+, respectively, while M is the repeating unit of PPXSPB.

3.2 Thermal stability of PPXSPB and EP/PPXSPB composite

Figure 4a is the TG and DTG curves of PPXSPB in air atmosphere. Epoxy resin will decompose at about 200°C in air (17), while PPXSPB starts to decompose at 250~300°C, which proves that it can adapt to the processing temperature of epoxy resin and may delay the decomposition of epoxy resin to some extent. The residual carbon content is 56.5% at 600°C, this indicates that it has good char formation, which may have potential promotion effect on the flame retardancy of the material (18, 19, 20, 21).

In order to study the thermal properties of the material degradation process, the thermal decomposition (TGA under nitrogen) and thermo-oxidate decompositon (TGA under air) of EP/PPXSPB composited are investigated. The TG and DTG curves of EP/PPXSPB composited with different contents of PPXSPB in nitrogen and in air are shown in Figures 4b and 4c. It can be seen that the initial decomposition temperature of the EP/PPXSPB system is slightly lower than that of the pure epoxy resin in the atmosphere of both air and nitrogen. This is perhaps due to the larger steric hindrance of PPXSPB which leads to low crosslink density of the EP/PPXSPB systems (22,23). As is shown in Figures 4b and 4c, the char yields around 480°C under air atmosphere are higher than which under nitrogen atmosphere. However, at 600°C and 800°C, the result is reversed where the char yield is lower in N2 atmosphere. So we can infer that an oxidative environment promotes the formation of a char layer earlier, it helps the substrate to fully oxidize and degrade at high temperatures.

However, it is noted that the residual carbon yield of the cured epoxy resin increases as phosphorus increases. The residual char yield of EP-1, EP-2, and EP-3 are 23%, 25%, and 27% respectively, while the residual char yield of EP-0 is only 5%. It means that the PPXSPB can improve the carbonization characteristics of the epoxy resin during combustion. As a result, it can be concluded that the phosphorus and nitrogen in the EP/PPXSPB system have a synergistic effect in the condensed phase to promote charring of epoxy resin (24,25).

3.3 Water resistance and flame resistance of EP/PPXSPB composite

The flame retardant and water resistance of the cured epoxy resins are listed in Table 3. As shown in Table 4, the LOI value of pure EP is only 18.0%, with the increase of phosphorus content, the LOI value of EP-1, EP-2 and EP-3 are increased to 28.8%, 31.4%, and 32.2%, respectively, which is due to the overall flame retardancy of the N-P synergistic flame retardant system (26,27). After immersion in water at 70°C for 168 h, the

Thermal analysis data of PPXSPB and EP/PPXSPB composites.

| Samples | Temperature of weight loss (°C) | Residue (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T5% | T5% | Tmax | Tmax | 600°C | 600°C | 800°C | 800°C | |

| (N) 2 | (Air) | (N) 2 | (Air) | (N) 2 | (Air) | (N) 2 | (Air) | |

| PPXSPB | / | 290 | / | 320 | / | 59.1 | / | 9 |

| EP-0 | 330 | 317 | 353 | 345 | 24.4 | 4.9 | 24.2 | 0.2 |

| EP-1 | 295 | 300 | 326 | 314 | 28.8 | 22.5 | 26.0 | 1.5 |

| EP-2 | 292 | 297 | 329 | 309 | 30.7 | 25.5 | 28.9 | 2.1 |

| EP-3 | 292 | 295 | 321 | 307 | 31.0 | 27.2 | 29.2 | 2.8 |

Flame retardance and water resistance of different simples.

| Sample | t(s) 1 | t(s) 2 | UL94 | LOI% | Dripping | M% | t’ (s) 1 | t’ (s) 2 | UL94 (after water immersion) | LOI% (after water immersion) | Dripping (after water immersion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-0 | 45 | 39 | Burning | 18.0 | No | 0.02 | 49 | 39 | Burning | 18 | No |

| EP-1 | 9 | 8 | V-0 | 28.8 | No | 0.11 | 20 | 12 | V-1 | 28.0 | No |

| EP-2 | 7 | 5 | V-0 | 31.4 | No | 0.18 | 9 | 7 | V-0 | 30.5 | No |

| EP-3 | 7 | 4 | V-0 | 32.2 | No | 0.27 | 9 | 4 | V-0 | 31.0 | No |

The TG and DTG curves of PPXSPB (a) and EP/PPXSPB composites (b,c): (a) in air atmosphere, (b) in nitrogen atmosphere, (c) in air atmosphere.

system shows a lower flame retardant migration rate. This is mainly due to the fact that PPXSPB forms a large number of chemical bond connections with epoxy, and the compatibility is greatly improved, thereby preventing the migration of the flame retardant to the surface of the material.

3.4 The cone calorimeter test

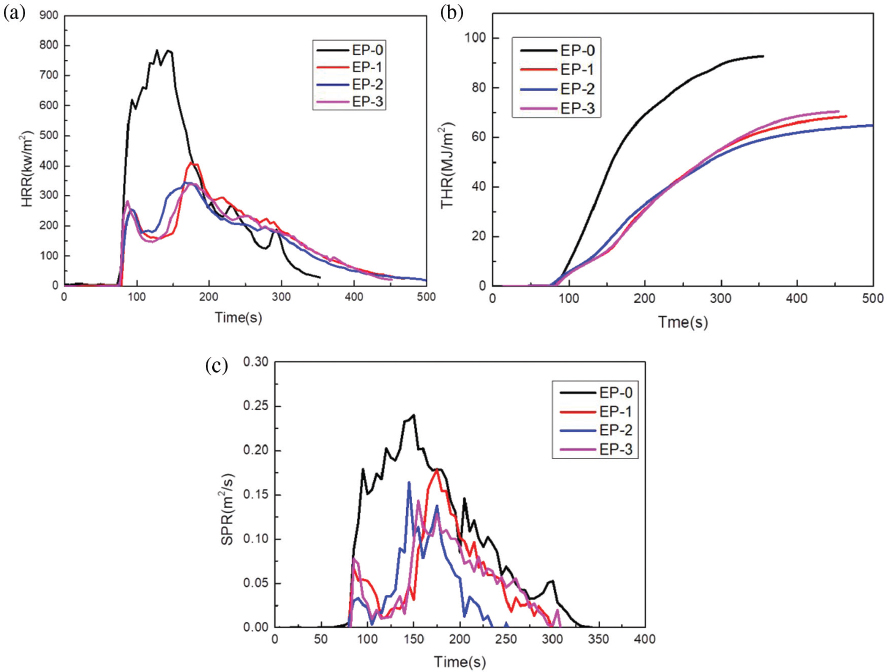

The fire hazard of materials is essentially a combination of thermal hazard and the smoke hazard. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the combustion characteristics of materials that cause thermal hazards and smoke hazards under fire conditions. Using the cone calorimeter is an effective way to measure these indicators. The heat release rate (HRR) is one of the most important effective evaluation parameters for thermal hazards in fire behavior, and the smoke produce rate (SPR) reflects the smoke hazard when the material is burning.

As is shown in Figures 5a-c, the peak heat release rate (PHRR), total heat release (THR) and smoke produce rate (SPR) of EP/PPXSPB composites are all lower than that of EP-0. This means that it can provide longer time for human escapes in the event of a fire. From the trend of HRR curve we can infer that after the flame retardant system begins to burn, the surface of the system rapidly forms a layer of carbon under the catalysis of the produced phosphoric acid, thereby causing a small decrease of HRR at the beginning of combustion.

HRR (a), THR (b), and SPR (c) curves of EP/PPXSPB composites.

SEM and digital images of the char residues after cone calorimeter test are revealed in Figure 6, combined with the residue which is showed in Table 5, it is obvious that after burning, EP-0 has only a small amount of residue, while the char of EP-2 was fully expanded and covered with small bubbles containing non-combustible gas. The surface of the system is heated to form an expanded carbon layer. On the one hand, external radiant heat is difficult to transfer to the inside, reducing the heat absorption value of the internal material and reducing the pyrolysis rate (28). On the other hand, it increases the time required for thermal degradation to release flammable volatiles. At the same time, the non-combustible gas released by the ruptured bubbles, such as NH3, H2O, etc., takes away the heat required for combustion, and the carbon layer formed on the surface can retard the contact speed of the material interior with oxygen to some extent, thereby delaying the burning of the materials (29).

Cone calorimeter data of EP/PPXSPB composites.

| Samples | TTI | PHRR | avHRR | THR | avEHC | avMLR | TSR | Residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (s) | (kW/m2) | (kW/m2) | (MJ/m2) | (MJ/kg) | (g/s) | (m2/m2) | (%) | |

| EP-0 | 79 | 785.54 | 335.44 | 92.25 | 23.20 | 0.128 | 3216.37 | 10.27 |

| EP-1 | 80 | 409.57 | 176.07 | 68.27 | 16.85 | 0.092 | 3003.04 | 25.83 |

| EP-2 | 81 | 344.52 | 146.06 | 65.00 | 16.29 | 0.075 | 2746.96 | 32.34 |

| EP-3 | 81 | 339.80 | 145.50 | 63.40 | 16.06 | 0.067 | 2549.81 | 32.50 |

3.5 Tensile strength, impact strength and adhesive strength of EP/PPXSPB composite

The tensile strength, impact strength and adhesive strength properties of different simples are shown in Table 6. The tensile strength and impact strength properties of EP/PPXSPB composite are reduced than EP-0. On the one hand, compared with the liquid curing agent used in EP-0, the solid curing agent used in this EP/PPXSPB composite is less likely to be evenly dispersed. During the mixing of the flame retardant system, some of the PPXSPB did not uniformly disperse, resulting in a slight agglomeration phenomenon, so that some PPXSPB cannot bond well with the epoxy resin and cause a slight gap in the system (30). Eventually, if there is external force contact, the system is unevenly stressed, and it is more prone to brittle fracture. On the other hand, steric hindrance is also one of the causes of the deterioration of the mechanical properties of the material. Larger steric hindrance of PPXSPB reduces the reactivity of PPXSPB, and some unreacted PPXSPB acts as a filler, thereby reducing the crosslink density of the system.

Tensile strength, impact strength and adhesive strength of EP/PPXSPB composite.

| Sample | P% | Tensile strength | Impact strength | Adhesive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (kJ/m2) | strength (MPa) | ||

| EP-0 | 0 | 64.97 ± 0.97 | 7.11 ± 0.91 | 13.0 ± 0.69 |

| EP-1 | 2.88 | 35.21 ± 0.87 | 4.86 ± 0.45 | 11.62 ± 0.34 |

| EP-2 | 3.24 | 47.10 ± 0.71 | 6.58 ± 0.68 | 13.79 ± 0.65 |

| EP-3 | 3.56 | 40.21 ± 0.99 | 5.92 ± 0.72 | 12.88 ± 0.59 |

SEM and digital images of the char residues after cone calorimeter test: (a) EP-0, (b) EP-0, (c) EP-0 magnification: 200 ×, (d) EP-2, (e) EP-2, (f) EP-2 magnification: 200 ×.

As for the adhesive strength of different simples, the adhesive strength of EP-2 increase 6% than that of EP-0. The main reason for this phenomenon is that the two curing agents have different internal stresses in the curing process. It is known that the use of a liquid curing agent will cause a certain degree of volume shrinkage of the curing system. When the internal stress is large, the adhesive strength will be significantly reduced. In addition, the stress distribution around the adhesive end or adhesive gap is not uniform, the resultant stress also increased the possibility of cracks appear. While PPXSPB is a solid curing agent, PPXSPB can partially act as filler during curing process, so the volume shrinkage of the cured product was reduced (31). At the same time, when the cured material containing the filler subject to the stress, the stress will be uniformly transferred to the surface of the filler particles. The filler takes most of the stress and played a role in the uniform distribution of stress. So there is a higher adhesive strength. However, too much excessive PPXSPB is equivalent to add an excessive amount of filler into the system. Excessive filler will reduce the degree of crosslinking of the system, and result in a decrease in adhesive strength.

4 Conclusions

A phosphorus-nitrogen flame-retardant curing agent PPXSPB was successfully synthesized. The impact of PPXSPB on the properties of the epoxy resin (E-44) was discussed. The results show that with the increase of phosphorus content, the flame retardant effect of the system is getting better and better. As a reactive flame retardant curing agent, it has excellent water resistance and is difficult to migrate. When the phosphorus content is 3.24%, the comprehensive performance of the system is best. The LOI value is 31.4%, impact strength is 6.58 kJ/m2, tensile strength is 47.10 MPa and the adhesive strength is 13.79 MPa.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from Shenyang Science and Technology plan 2017 project (17-9-6-00).

References

1 Zhang X., He Q., Gu H., Henry A.C., Wei S.Y., Guo Z.H., Flame-retardant electrical conductive nanopolymers based on bisphenol F epoxy resin reinforced with nano polyanilines. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf., 2013, 5, 898-910.10.1021/am302563wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Weil E., Levchik S., A review of current flame retardant systems for epoxy resins. J. Fire Sci., 2004, 22, 1-25.10.1177/0734904104038107Suche in Google Scholar

3 Zhao W., Liu J., Peng H., Liao J.Y., Wang X.J., Synthesis of a PEPA-substituted polyphosphoramide with high char residues and its performance as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resins. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2015, 118, 120-129.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.04.023Suche in Google Scholar

4 Xiao L., Sun D., Niu T., Yao Y.W., Syntheses and characterization of two 9,10-dihydro-9-oxa-10-phosphaphenanthrene-10-oxide-based flame retardants for epoxy resin. High Perform. Polym., 2014, 26, 52-59.10.1177/0954008313495064Suche in Google Scholar

5 Deng J., Shi W.F., Synthesis and effect of hyperbranched (3-hydroxyphenly) phosphate as a curing agent on the thermal and combustion behaviors of novolac epoxy resin. Eur. Polym. J., 2004, 40, 1137-1143.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2003.12.015Suche in Google Scholar

6 Kalali E.N., Wang X., Wang D.Y., Functionalized layered double hydroxide-based epoxy nanocomposites with improved flame retardancy and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 6819-6826.10.1039/C5TA00010FSuche in Google Scholar

7 Xu G.R., Xu M.J., Li B., Synthesis and characterization of a epoxy resin based on cyclotriphosphazene and its thermal degradation and flammability performance. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2014, 109, 240-248.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.07.020Suche in Google Scholar

8 Yuan Y., Yang H., Yu B., Shi Y.Q., Wang W., Song L., et al., Phosphorus and Nitrogen-Containing Polyols: Synergistic Effect on the Thermal Property and Flame Retardancy of Rigid Polyurethane Foam Composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2016, 55, 10813-10822.10.1021/acs.iecr.6b02942Suche in Google Scholar

9 Li Z.S., Song T., Liu J.A., Yan Y., Thermal and combustion behavior of phosphorus–nitrogen and phosphorus–silicon retarded epoxy. Iran. Polym. J., 2017, 26, 21-30.10.1007/s13726-016-0495-8Suche in Google Scholar

10 Lin Y., Sun J., Zhao Q., Zhou Q.Y., Synthesis and properties of a flame-retardant epoxy resin containing biphenylyl/phenyl phosphonic moieties. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng., 2012, 51, 896-903.10.1080/03602559.2012.671424Suche in Google Scholar

11 Müller P., Schartel B., Melamine poly(metal phosphates) as flame retardant in epoxy resin: performance, modes of action and synergy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2016, 133, 43549.10.1002/app.43549Suche in Google Scholar

12 Toldy A., Anna P., Csontos I., Marosi G., Intrinsically flame retardant epoxy resin-Fire performance and background – Part I. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2007, 92, 2223-2230.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.04.017Suche in Google Scholar

13 Ma H.Y., Li F.T., Xu Z.B., Fang Z.P., Jin Y.M., Lu F.Z., A noval intumescent flame retardant: Synthesis and application in ABS copolymer. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2007, 92, 720-726.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2006.12.009Suche in Google Scholar

14 Wang Q., Chen Y.H., Liu Y., Wang Q., Yin H., Aelmans N., et al., Performance of intumescent flame retardant master batch synthesized through twin-screw reactively extruding technology: effect of component ratio. Polym. Int., 2004, 53, 439-448.10.1002/pi.1394Suche in Google Scholar

15 Yang X.J., Wang C.P., Xia J.L., Mao W., Li S.H., Study on synthesis of phosphorus-containing flame retardant epoxy curing agents from renewable resources and the comprehensive properties of their combined cured products. Prog. Org. Coat., 2017, 110, 195-203.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.01.012Suche in Google Scholar

16 Li Q., Jiang P.K., Wei P., Synthesis characteristic and application of new flame retardant containing phosphorus nitrogen and silicon. Polym. Eng. Sci., 2006, 46, 344-350.10.1002/pen.20472Suche in Google Scholar

17 Qian X.D., Song L., Hu Y., Richard K.K.Y., Chen L.J., Guo Y.Q., et al., Combustion and Thermal Degradation Mechanism of a Intumescent Flame Retardant for Epoxy Acrylate Containing Phosphorus and Nitrogen. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2011, 50, 1881-1892.10.1021/ie102196kSuche in Google Scholar

18 Ren R., Sun J.Z., Wu B.J., Zhou Q.Y., Synthesis and properties of aphosphorus-containing flame retardant epoxy resin based on bis-phenoxy (3-hydroxy) phenyl phosphine oxide. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2007, 92, 956-961.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

19 Gao J.G., Li D.L., Shen S.G. Liu G.D., Curing kinetics and thermal property characterization of a bisphenol-F epoxy resin and DDO system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2002, 83, 1586-1595.10.1002/app.10139Suche in Google Scholar

20 Parveen K., Agarwal S., Naarual A.K., Choudhary V., Studies on the curing and thermal behavior of DGEBA in the presence of bis(4-carboxyphenyl) dimethyl silane. Polym. Int., 2003, 52, 908-917.10.1002/pi.1128Suche in Google Scholar

21 Frabcis B., Poel G.V., Posada F., Cure kinetics and morphology of composites of epoxy resin with poly (ether ether ketone) containing pendant tertiary butyl groups. Polymer, 2003, 44, 3687-3699.10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00296-9Suche in Google Scholar

22 Dong C.L., Wirasaputra A., Luo Q.Q., Liu S.M., Yuan Y.C., Zhou J.Q., et al., Intrinsic Flame-Retardant and Thermally Stable Epoxy Endowed by a Highly Efficient, Multifunctional Curing Agent. Materials, 2016, 9, 1-15.10.3390/ma9121008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Lu L.G., Qian X.D., Zeng Z.J., Yang S.S., Shao G.S., Wang H.Y., et al., phosphorus-based flame retardants containing 4-tert-butylcalix[4]arene: Preparation and application for the fire safety of epoxy resins. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2017, 134, 45105.10.1002/app.45105Suche in Google Scholar

24 You Y.G., Cheng Z.Q., Peng H., He H.W., Synthesis and performance of a nitrogen-containing cyclic phosphate for intumescent flame retardant and its application in epoxy resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2015, 132, 41859.10.1002/app.41859Suche in Google Scholar

25 Liang H.B., Ding J., Shi W.F., Kinetics and mechanism of thermal oxidative degradation of UV cured epoxy acrylate/ phosphate triacrylate blends. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2004, 86, 217-223.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2004.04.014Suche in Google Scholar

26 Liu Z.Y., Xu M.J., Wang Q., Bin L., A durable flame retardant cotton fabric produced by surface chemical grafting of phosphorus- and nitrogencontaining compounds. Cellulose, 2017, 24, 4069-4081.10.1007/s10570-017-1391-xSuche in Google Scholar

27 Liu H., Wang X.D., Wu D.Z., Synthesis of a linear polyphos-phazene-based epoxy resin and its application in halogen-free flame-resistant thermosetting systems. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2015, 118, 45-58.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.04.009Suche in Google Scholar

28 Luo Q.Q., Yuan Y.C., Dong C.L., Huang H.H., Liu S.M., Zhou J.Q., Highly Elective Flame Retardancy of a DPPA-Based Curing Agent for DGEBA Epoxy Resin. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2016, 55, 10880-10888.10.1021/acs.iecr.6b02083Suche in Google Scholar

29 You G.Y., Cheng Z.Q., Tang Y.Y., He H.W., Functional Group Effect on Char Formation, Flame Retardancy and Mechanical Properties of Phosphonate-Triazine-based Compound as Flame Retardant in Epoxy Resin. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2015, 54, 7309-7319.10.1021/acs.iecr.5b00315Suche in Google Scholar

30 Liang B., Wang G., Hong X., Long J.P., Noritatsu T., Synthesis and properties of a new halogen-free flame-retardant epoxy resin curing agent. High Perform. Polym., 2016, 28, 110-118.10.1177/0954008315604036Suche in Google Scholar

31 Liu X.L., Liang B., Impact of a phosphorus-nitrogen flame retardant curing agent on the properties of epoxy resin. Mater. Res. Express, 2017, 4, 125103.10.1088/2053-1591/aa9dbaSuche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die