Abstract

Polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives (PURHs) are frequently employed in industries; however, there is still a need to develop more sustainable and versatile methodologies to expand the functions and fabrication of these important materials. Renewable feedstock can give PURHs with new functions, and reduce environmental impact. This study focuses on synthesizing PURHs using polyols derived from biomass (plants) and greenhouse gas (CO2) resources. These PURHs were characterized by multiple techniques, including solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), a dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), single-lap adhesive joints strength of stainless steel, and hydrolytic ageing. The PURH film based on biomass poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (bio-PTMEG) exhibited better water vapor permeability, tensile strength, and adhesive joints properties than PURHs based on cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) polyester diol and poly(propylene carbonate)-poly(propylene glycol) (PPC-PPG) copolymer diol. The polyols blend of bio-PTMEG with biomass and CO2 based polycarbonate diols respectively provided PURHs films excellent hydrolysis resistance and adhesive strength on single-lap adhesively bonded stainless steel specimens. The work herein demonstrates that various renewable polyols can be employed in a sustainable fashion to optimize the structures and properties of PURHs for important applications.

1 Introduction

Polyurethanes reactive hot-melt adhesives (PURHs) are 100% solid, isocyanate-terminated urethane prepolymers that are synthesized by reacting polyols with excess isocyanate (Scheme 1) (1). PURHs are applied as adhesives in a molten state, cooled to solidify, and can be subsequently cured through the reaction of the isocyanate groups and ambient moisture (2). The moisture-cured mechanism is the isocyanate groups to react with moisture to form an unstable intermediate, carbamic acid. The unstable carbamic acid decomposes into carbon dioxide and an amine; then the amine reacts with isocyanate group to form a urea linkage (3). In adhesive joints application, the formula of PURHs contain crystalline and linear aliphatic polyester polyols can developed fast adhesive strength with increasing joined assemblies productivity (4). In contrast, polyether polyols, such as poly(propylene glycol) (PPG), are used to produce PURHs with low temperature flexibility and softness (5). Furthermore, PURHs made from poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (PTMEG) can exhibit better mechanical properties and hydrolytic stability than PPG (6,7).

Most of the polyester and polyether polyols currently used for PURHs are via from petroleum-based resource and has been extensively studied. In contrast, renewable resource makes it possible to develop the polyols with new functions, which are less accessible via petroleum-based products. These polyols derived from plant source (e.g., bio-based acids and diols, natural oil polyols, etc.) and carbon dioxide (CO2) can provide PURHs with novel properties and sustainable application (8, 9, 10). Earlier study has been done on the polyester polyols blend of bio-based 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PDO) backbone with petroleum-based 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BDO) backbone for 4, 4’-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI) based PURHs (11). The addition of bio-based 1,3-PDO backbone polyol in the PURHs, the molten viscosity could be lowered while retaining the adhesively bonded strength of stainless steel specimens, and humidity resistance as compared to petroleum-based 1,4-BDO backbone polyol PURHs. Another application to PURHs, the poly(propylene carbonate) polyols (PPC polyols) prepared via CO2 and epoxides copolymerization have been substituted some traditional transesterification process products as an inexpensive, abundant, nontoxic and renewable resource. The addition of PPC diols in the MDI based PURHs showed better adhesive strength than the petroleum-based polyols such as poly(1,6-hexamethylene adipate) and poly(1,4-butylene adipate) on metal (aluminum and stainless steel), plastic (poly(methyl methacrylate), polycarbonate), and leather to halogenated styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) joints of upper-sole bonding (12,13).

Scheme for the sythesis and moisture-curing processes of PURHs.

Although many studies have attempted to optimize and maximize the renewable resource polyols in PURHs as adhesive joints, little work had been done on expanding the functional applications of PURHs, such as their application in breathable clothing and biomedical materials (14,15). The aim of the present work is to develop PURHs based on biomass and CO2 derived polyols, and to examine the effects of PURH structure on surface charge, wettability, moisture permeability, tensile strength, adhesive joint strength, and hydrolysis resistance properties. In this study, the bio-based poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (bio-PTMEG) as a standard specimen to contrast cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) based polyester diol, the copolymer diol of CO2-based PPC and PPG, CO2-based PPC diol and biomass-based aliphatic polycarbonate diol on the PURHs properties.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

A biomass based poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (bio-PTMEG, bio-based PolyTHF® 1000) was obtained from BASF Co., Ltd., Taiwan. A cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) based polyester diol (Cardolite® NX-9203LP) was obtained from Cardolite Co., Ltd., China. A CO2-based polycarbonate polyol, poly(propylene carbonate) diol (PPC diol, Converge® polyol 212-10) and poly(propylene carbonate)-poly(propylene glycol) copolymer diol (PPC-PPG diol, Converge® polyol CPX-2501-56) were obtained from Aramco Co., Ltd., USA. A biomass based aliphatic polycarbonate diol, using decanediol from castor oil (bio-PCD, BENEBiOL™, NL1010DB) was obtained from Mitsubishi chemical Co., Ltd., Japan. The 4, 4’-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI, DESMODUR® 44 C FUSED) was obtained from Covestro Co., Ltd., China. The catalyst 2,2’-dimorpholinodiethylether (Jeffcat® DMDEE), was obtained from Huntsman Co., Ltd., Taiwan.

2.2 Synthesis of the isocyanate-terminated PURH prepolymers

The isocyanate-terminated PURH prepolymers (PURH prepolymers) were synthesized by the reaction between a polyol or polyol blends and an excess of diisocyanate (MDI). The synthesis molar ratio of NCO to OH groups was 1.4:1 and theoretical isocyanate content value (NCO wt%) was 2.5 (2,16). The compositions and nomenclature of the prepolymers are given in Table 1. The PURH prepolymers synthesis was carried out in a round-bottomed, four-necked liter flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a heating mantle and a thermometer. In the prepolymerization process, a selected polyol or polyol blends was added to the reactor and heating to 115 ± 5°C under a vacuum of less than 1 mm Hg for 1 h to remove the residual water. MDI was melted at 50°C and used after excluding white MDI dimer precipitates in the melt (17). After that, MDI and DMDEE were added sequentially into the reactor and stirred for 1.5 h at 115 ± 5°C until the desired NCO wt% was obtained.

Polyols properties and usage for the PURH prepolymers.

| Polyols properties | Prepolymers synthesis, feed by percent weight | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyols | Molecular weight | Characteristic | PUR-1 | PUR-2 | PUR-3 | PUR-4 | PUR-5 |

| (Trade name) | (g/mol) | (by DSC)* | |||||

| bio-based PolyTHF 1000 | 1,000 | Tm = 25°C | 74.03 | 37.03 | 37.03 | ||

| NX-9203LP | 1,050 | Tg = −68°C | 80.44 | ||||

| Converge CPX-2501-56 | 2,000 | Tg = −34°C | 82.28 | ||||

| Converge 212-10 | 1,000 | Tg = −3°C | 37.03 | ||||

| NL1010DB | 1,000 | Tm = 45°C | 37.03 | ||||

| MDI | 250 | Tm = 40°C | 25.95 | 19.56 | 17.72 | 25.95 | 25.95 |

| The NCO content (wt%) of prepolymers | 2.32 | 2.39 | 2.25 | 2.76 | 2.48 | ||

| The dynamic viscosity (cps, 115°C) of prepolymers | 4,383 | 725 | 2,475 | 11,630 | 7,625 | ||

*DSC (differential scanning calorimetry) was performed on a DSC204F1 (Netzsch Instrument Co., Ltd) at a heating rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere from −80°C to 100°C.

2.3 Preparation of moisture-cured PURHs films

The PURH prepolymers in molten state (115 ± 5°C), were coated on the release paper by a coating rod to form instruments analysis specimens. The thickness of the films obtained was approximately 0.2 mm. After that, let the films exposed the air for 15 days to obtain the moisturecured PURH films. The moisture-curing environment was kept at 25 ± 2°C and 80 ± 10% relative humidity. Each PURH film was confirmed by the ATR-FTIR spectra, the isocyanate group band stretch at 2270 cm–1 should disappeared after the moisture-curing reaction (18).

2.4 Single-lap shear adhesive joints preparation

Adhesive properties of moisture-cured PURHs were obtained single-lap shear adhesive joints that bonded stainless steel to stainless steel. 0.2 g PURH prepolymers (molten state, 115 ± 5°C) was applied to a square area (2.54 cm × 2.54 cm) of one substrate by a coating rod, and then immediately joined to another substrate. These single-lap shear adhesive joints were kept at 25 ± 2°C and 80 ± 10% relative humidity environment for 15 days moisture-curing reaction.

2.5 Characterization of PURH prepolymers

2.5.1 Dynamic viscosity of PURH prepolymers

The melt dynamic viscosity of the PURH prepolymers was determined at 115 ± 1°C by a Brookfield viscometer (DV2T), RV type (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories Inc., USA). The measurements were performed using the spindle No.27 (SC4-27, Brookfield spindle) at 20 rpm.

2.5.2 Isocyanate contents (NCO contents) in PURH prepolymers

The NCO contents of PURH prepolymers, by weight, (NCO wt%) were determined according to ASTM D 2572-91. The prepolymer was reacted with an excess of 0.5 N dibutylamine and then titrated (702 SM Titrino, Metrohm, Switzerland) with a standard 0.5N HCl solution. The NCO wt% values are given in Table 1.

2.6 Characterization of moisture-cured PURHs films

2.6.1 Solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis

The solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy of the PURHs film were performed on a Bruker AVANCE-400 spectrometer (Bruker Co., Germany); equipped with a Bruker 7 mm probe, operating at 100.6 MHz (9.4 Tesla magnetic field) and spinning speed at 5 kHz in a 25 ± 2°C environment.

2.6.2 Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) analysis

ATR-FTIR analysis of the PURHs film (the average thickness was 0.2 mm) were carried out in a Nicolet Avatar 360 spectrometer (Nicolet Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) with a horizontal plate ATR accessory. Each PURH film was scanned 64 times at a resolution of 4 cm–1 in a 25 ± 2°C environments. The curve fitting function was performed by using Origin® software program (OriginLab, USA). The absorption bands were deconvoluted by Gaussian function to get the Gaussian-fit peaks (19,20).

2.6.3 Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA)

The dynamic mechanical properties of the PURHs film were obtained by using a DMA (DMA 2980, TA Instruments Co., USA) in dual cantilever model at a frequency of 1 Hz, and with a heating rate of 3°C/min under nitrogen atmosphere. The temperature range was from –80°C to 80°C. These test specimens were 13.6 (length) × 6.53 (wide) × various PURHs film thickness (mm3).

2.6.4 Water vapor transmission rate (WVTR)

The WVTR of the PURHs film was measured with the water method according to the ASTM E96 procedure B. The PURHs film covered and fixed on a cylindrical aluminum jar, which filled with distilled water. The examined PURH film area was 10 cm2. The experimental conditions for all the examined PURH film were 23 ± 1°C and 60 ± 5% relative humidity for 24 h. WVTR is defined as the steady water vapor flow in unit of time through unit of area of a body, normal to specific parallel surfaces, under specific conditions of temperature and humidity at each surface. Since the thickness of the films varied, the WVTR was normalized to film thickness in order to obtain the specific water vapor transmission rate (film thickness × WVTR) with units of mil⋅g⋅m–2⋅h–1.

2.6.5 Wettability

A contact angle analyzer was used for static wettability measurement of PURHs film. (FTA 200, First Ten Angstroms Inc., USA). Distilled water was deposited on the surface of PURHs film and the contact angles were measured after 60 s, using a video-based optical contact angle measuring device equipped.

2.6.6 Surface zeta (ζ) potential determination

The surface charge of PURHs film were measured by surface zeta potential determination with an ELSZ-2000 (Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), which is based on electrophoretic light scattering.

2.6.7 Tensile properties

The tensile strength was carried out on a universal testing machine (AI-7000 M, Gotech test machines Inc., Taiwan) with dumbbell-shaped specimens as per ASTM D638 at 25 ± 1°C conditions with a speed of 500 mm/min.

2.6.8 Adhesive strength of single-lap shear joints test

The adhesive strength on single-lap adhesively bonded stainless steel specimens was measured according to ASTM D1002-05. A universal testing machine (AI-7000 M, Gotech test machines Inc., Taiwan) was performed the single-lap joints shear strength with using a crosshead speed of 1.3 mm/min.

2.6.9 Hydrolytic stability test

The hydrolytic stability of the PURHs films and adhesive joints was tested according to ASTM D 3690-02 in a humidity chamber at 70 ± 1°C and 95 ± 5% relative humidity for 30 days. The retention of tensile strength and adhesive joints were measured according to previous methods.

3 Results and discussion

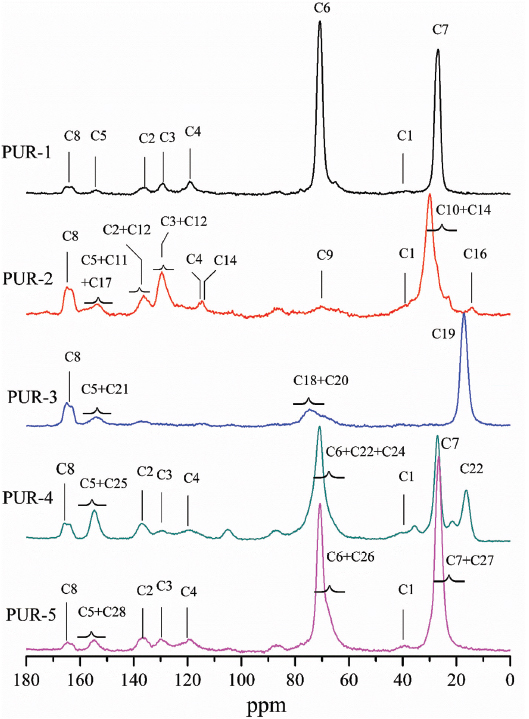

3.1 Solid-state 13C NMR analysis

The solid-state 13C NMR technique was used to determine the structure of moisture-cured PURHs with various polyols derived from biomass and CO2 (Scheme 1). As shown in Figure 1, the characteristic peak for MDI aromatic ring appeared at around 136.5, 129.2 and 119.1 ppm; the methylene carbon in the MDI appeared at around 40 ppm (21,22). The carbonyl groups assigned to the urethane and urea appeared around 154.6 and 164.2 ppm, respectively (23).

Solid-state 13C NMR spectra of moisture-cured PURHs.

In the PUR-1 spectrum, the peaks at 70.8 and 26.8 ppm were attributing to the methyleneoxy and methylene carbon groups of bio-PTMEG, respectively (24). In the PUR-2 spectrum, the aromatic carbon peaks in the range 112-128 ppm were also attributed to the cardanol based polyester diol. The peak at 156 ppm is for the aromatic carbon attached to the oxygen atom. The peaks at 14-30 and 114.3 ppm were attributing to the ethyl carbonate and olefins groups of the cardanol side chain, respectively (25). The peak at 153.5 ppm was attributed to carbonyl group due to ester linkage (26). In the PUR-3 spectrum, the peak at 17.1, 73.1, and 74.6 ppm were attributed to the carbon of methyl, methylene, and methane in PPC end-capped with propylene oxide segment (27). The peak at 153.7 ppm corresponds to the carbonyl carbon of the PPC (28). In the PUR-4 spectrum, the peak at around 70.6 ppm, which is ascribed to the methyleneoxy, methylene and methine carbon groups attached on the bio-PTMEG and PPC (29). The peak at 16.4 and 154.6 ppm were assigned the methyl and carbonyl groups to PPC. In the PUR-5 spectrum, the peak at around 70.6 and 26.7 ppm which were ascribed to the methyleneoxy and methylene groups attached on the bio-PTMEG and bio-mass based polycarbonate diol, respectively (30). The peak at 154.9 ppm due to carbon atom of carbonate groups (29).

3.2 ATR-FTIR analysis

ATR-FTIR was used to evaluate the hydrogen bonding characteristics in the microstructure of moisture-cured PURHs film. Figure 2a shows the ATR-FTIR spectroscopy absorption bands of PURHs, such as 3100 to 3500 cm–1 (N–H stretching vibrations), 1600 to 1800 cm–1 (C=O stretching vibrations), and 1110 cm–1 (C–O–C stretching vibration, ether group), which are the main characteristics for the urethane groups (31).

The deconvolution peak of the N–H stretching band can quantify the degree of N–H hydrogen bonded and free stretching vibration in the PURHs by curve fitting with Gaussian function (Figures 2b and 2c). In each spectrum, the N–H stretching vibration exhibited a strong absorption peak centered at around 3315 cm–1 arising from the hydrogen bonding of N–H, while the free N–H stretching vibration appears as a weak shoulder at around 3445 cm–1 (32). Table 2 shows that each PURH exhibited much higher relative area of N–H hydrogen bonding than free N–H stretching vibration, and PUR-1 was lower degree of the N–H hydrogen bonding among that of the others PURHs. The degree of N–H hydrogen bonding can be explained on the segregation or mixing of the hard segments (derived from the reaction of the NCO groups and water) and soft segments (derived from the polyols) in PURs (33). The hydrogen bonding of N–H stretching, absorption peak centered at around 3315 cm–1, was also assigned as N–H groups hydrogen bonded with C–O–C groups that suggests the mixing of hard segments and soft segments (34). Therefore, PUR-1 exhibited lower degree of the N–H hydrogen bonding among that of the others PURHs can be attributed to bio-PTMEG produced lower degree of microphase mixing than others polyols did. This behavior is primarily due to bio-PTMEG its lower polarity than that of the others polyester and polycarbonate based diols (34,35).

ATR-FTIR spectra deconvolution result of NH region in moisture-cured PURHs film.

| Specimen | Polyol usage | Bonded N–H | Free N–H |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak area (%)a | Peak area (%)a | ||

| PUR-1 | bio-PTMEG | 82.6 | 17.4 |

| PUR-2 | CNSL | 91.1 | 8.9 |

| PUR-3 | PPC-PPG | 95.0 | 5.0 |

| PUR-4 | bio-PTMEG/PPC | 90.1 | 9.9 |

| PUR-5 | bio-PTMEG/ | 91.8 | 8.2 |

| bio-PCD | |||

a The peak areas are based on total N-H stretching band area.

In the present work, we used the surface zeta potential determination to estimate polarity characteristics of PURH films. From Table 3, the bio-PTMEG based PURH exhibited closer to neutral value of surface zeta potential than that of the others polyols.

Properties of moisture-cured PURHs film.

| Specimen | Polyol usage | Tg | WVTR | Wetting tension | Contact angle | ζ potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (g‧mil‧m–2‧day–1) | (dyne/cm) | (°) | (mv) | ||

| PUR-1 | bio-PTMEG | −28 | 502 | 15 | 78.12 | −10.36 |

| PUR-2 | CNSL | 22 | 39 | 8 | 83.97 | −21.45 |

| PUR-3 | PPC-PPG | 18 | 169 | 10 | 82.10 | −21.89 |

| PUR-4 | bio-PTMEG/PPC | 49 | 155 | 17 | 76.53 | −17.71 |

| PUR-5 | bio-PTMEG/bio-PCD | −11 | 287 | 26 | 69.44 | −15.80 |

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra for moisture-cured PURHs film, (b) ATR-FTIR spectra deconvolution model of N–H stretching region, (c) ATR-FTIR spectra deconvolution results of N–H stretching region.

Hence, the degree of the N–H hydrogen bonding in PURH was related to polyols polarity which reflected in the surface zeta potential of PURH.

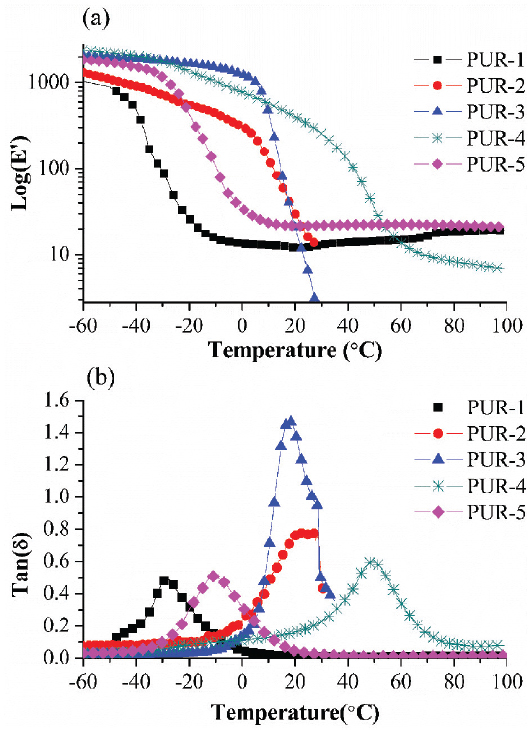

3.3 Dynamic mechanical properties

DMA was used to measure the viscoelastic characteristic and glass transition temperatures (Tg) of moisture-cured PURHs. Under tension deformation, the measured elastic component is referred to as the storage modulus (E’), while the measured viscous component is referred to as the loss modulus (E”). The ratio of the loss modulus to the storage modulus is referred to as the tan delta (tanδ). Tg of the PURHs is located as the temperature where tanδ is maximum (Table 3).

Before the temperature passed through the Tg of PUR-1, PUR-1 showed lower E’ value than those of others PURHs films (Figure 3), which may be due to bio-PTMEG based soft segments were more flexible than the others polyol. However, PUR-2, PUR-3 and PUR-4 were showed rapidly decline in the E’ than PUR-1 and PUR-5 when the temperature through their Tg. The rapidly decline for the E’ can be attributed to the CNSL based polyester diol and PPC-PPG copolymer block diol were amorphous structure; and further, the amorphous molecular chains shapes could not recovery during the tension acting of DMA test when the temperature passed through their Tg (36).

3.4 WVTR analysis

The WVTR of moisture-cured PURH film is a hydrophilic property at a given temperature. The WVTR depend on water vapor adsorbed on the surface of PURH film and then diffuses through the film (37). Furthermore, increasing of WVTR can satisfy the requirement for a coating on outdoor garments to maintain a constant body temperature (14). If the PURH film based on higher water wetting tension and closer to neutral zeta potential, the resulting PURH will has higher WVTR value and exhibit more hydrophilicity (15).

DMA analysis of moisture-cured PURHs film: (a) storage modulus (E’) and (b) Tan delta (Tanδ).

The WVTR decreased sequentially in the following order: PUR-1 (bio-PTMEG) > PUR-5 (bio-PTMEG/bio-PCD) > PUR-3 (PPC-PPG) > PUR-4 (bio-PTMEG/PPC) > PUR-2 (CNSL), as shown in Table 3. The PUR-1 film had the highest WVTR value; however, it was less related to the wettability and surface zeta potential value (Table 3). The highest WVTR value may be attributed to the Tg of PUR-1 was lower than the WVTR test temperature (23 ± 1°C) that resulted in the microstructures of PUR-1 exhibited more loose state, and consequently enhanced water vapor diffused through the PUR-1 film (38). Table 3 also shows most of WVTR value seemed inversely proportional to the Tg of PURHs except PUR-2. This result can be explained by the lower water wetting tension that reflected PUR-2 had less hydrophilic degree than the others PURHs film, which resulted from the CNSL based polyester diol with more hydrophobicity of cardanol backbone.

3.5 Tensile and adhesive properties of PURHs

Table 4 lists the tensile strength and single-lap shear joints adhesive strength of moisture-cured PURHs films. The single-lap shear joints of PURHs were obtained from stainless steel specimens (SS-to-SS).

Tensile strength of PURHs film and single-lap shear joint strength of moisture-cured PURHs.

| Specimens | PUR-1 | PUR-2 | PUR-3 | PUR-4 | PUR-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyol usage | bio-PTMEG | CNSL | PPC-PPG | bio-PTMEG/ PPC | bio-PTMEG/ bio-PCD |

| (a) Tensile strength (MPa) | |||||

| Strength for 15 days moisture-cured | 11.1 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 51.5 | 40.7 |

| Strength after 30 days hydrolytic aging | 7.1 | 8.0 | 3.5 | 28.9 | 28.0 |

| Retention of tensile strength (%) | 64 | 90 | 59 | 56 | 69 |

| (b) Single lap-shear joint strength of stainless steel to stainless steel (MPa) | |||||

| Strength for 15 days moisture-cured | 3.07 | 1.67 | 2.67 | 4.21 | 2.35 |

| Strength after 30 days hydrolytic aging | 2.70 | 0.81 | 2.10 | 3.1 | 2.12 |

| Retention of adhesion strength (%) | 88 | 49 | 79 | 74 | 90 |

In general, more amount of hydrogen bonding would improve the tensile strength for the PURH (39,40) (Table 2); however, PUR-1 showed higher tensile strength, and single-lap shear joint strength of SS-to-SS than PUR-2 and PUR-3. This result may be attributed to bio-PTMEG its crystallizable structure, which can increase higher degree of mechanical, and adhesive properties compared with the others amorphous polyols. Furthermore, the bio-PTMEG has lower molecular weight than the CNSL based polyester diol and PPC-PPG diol, which also made PURH molecule chains more rigid, and increased tensile strength for PUR-1 (41). On the other hand, PUR-1 exhibited higher water wetting tension than PUR-2 and PUR-3, which also contributed to greater contact area between adherend and adhesive, and then furthered the adhesive strength of SS-to-SS (42).

Both the addition of CO2 and biomass based polycarbonate diols in PUR-4 and PUR-5 were greatly increasing the tensile strength as compared with the bio-PTMEG based PUR-1. This result was due to the carbonate-urethane linkage producing better mechanical properties (43). For adhesive property, PUR-4 had better SS-to-SS joint adhesive strength than PUR-1 and PUR-5. This result may be attributed to the PPC diol provided PUR-4 with more polar groups than PUR-5 and PUR-1, which resulted from the PPC diol has higher O/C atom ratio than the bio-PTMEG and bio-PCD diol (44). This is also reflected in PUR-4 had the higher negative value of surface zeta potential than PUR-5 and PUR-1.

3.6 Hydrolysis resistance test of PURHs film and PURHs adhesive joints

The hydrolysis resistance test was to determine the resistance of moisture-cured PURHs films and the SS-to-SS adhesive joints subjected to a combination of an elevated temperature and high humidity. The results of hydrolysis resistance test of PURHs film on tensile strength and single-lap shear joints adhesive strength are presented in Table 4.

The retention of tensile strength of PURHs film decreased sequentially in the following order: PUR-2 (CNSL) > PUR-5 (bio-PTMEG/bio-PCD) > PUR-1 (bio-PTMEG) > PUR-3 (PPC-PPG) > PUR-4 (bio-PTMEG/PPC). PUR-2 had the highest hydrolysis resistance degree because of the CNSL based polyester diol contain aromaticity and long aliphatic chain delivers hydrolytic stability. The addition of polycarbonate diols in the PURHs, PUR-4 showed lower retention of tensile strength than PUR-5 after hydrolysis ageing; the lower degree of hydrolytic stability mainly due to the higher concentration of carbonate group of PPC diol which result from the shorter carbon chain in the repeating unit (45).

However, the tensile strength retention of PURHs was not directly proportional to the retention of single-lap shear adhesive joints strength after hydrolysis ageing. PUR-2, PUR-3 and PUR-4 showed lower retention degree of SS-to-SS joints adhesive strength than PUR-1 and PUR-5. In general, the more polar groups in adhesive implies a better adhere to smooth metal surfaces (46). A possible explanation for is that the ageing temperature caused part of molecular segments in PUR-1 and PUR-5 had more chance than the others PURHs to deform or rearrange which was due to their Tg were much lower than the ageing temperature. Furthermore, the movement of molecular segments spread the applied energy to the others molecular segments which contributed to increase the degree of ageing resistance or decrease interfacial adhesion failure between the PURH and stainless steel under the ageing impact (42).

4 Conclusions

A series of moisture-cured PURHs were synthesized from the biomass and CO2 based polyols, and examined these PURHs on chemical, physical, mechanical and adhesive joints properties. The usage of bio-PTMEG imparted the PURH with better wetting tension, WVTR, tensile strength and SS-to-SS joints adhesive strength than the CNSL based polyester diol and PPC-PPG copolymer diol be used for PURH. In contrast to bio-PTMEG, the PURH film based on CNSL diol showed more hydrophobic and better hydrolysis resistance than the others polyols. Both of the CO2 and biomass based polycarbonate diols added in the PURHs showed increasing of hydrophilicity, hydrogen bond interactions, tensile strength as well as SS-to-SS adhesive joints strength; especially, the biomass based polycarbonate diols showed excellent hydrolysis resistance on the SS-to-SS adhesive joints tests. The renewable resource polyols in this study were provided unique functional to PURHs, which was expected to inspire usage of renewable resource for environmental protection and sustainable development.

References

1 Randall D., Lee S., The polyurethanes book. Wiley, New York, 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

2 Szycher M., Szycher’s Handbook of polyurethanes. CRC Press, Bosa Roca, 2012.10.1201/b12343Suche in Google Scholar

3 Cho Y.B., Jeong H.M., Kim B.K., Reactive hot melt polyurethane adhesives modified by acrylic copolymer nanocomposites. Macromol. Res., 2009, 17, 879-885.10.1007/BF03218630Suche in Google Scholar

4 Sonnenschein M.F., Polyurethanes: Science, Technology, Markets, and Trends. Wiley, New Jersey, 2014.10.1002/9781118901274Suche in Google Scholar

5 Meier-Westhues U., Polyurethanes: coating, adhesives and sealants. Vincentz Network, Hannover, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

6 Chaudhury M., Pocius A.V., Adhesion science and engineering: surfaces, chemistry and applications. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2002.10.1016/B978-044451140-9/50000-7Suche in Google Scholar

7 Pizzi A., Mittal K.L., Handbook of adhesive technology, revised and expanded (2nd ed.). CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2002.10.1201/9780203912225Suche in Google Scholar

8 Sahoo S., Kalita H., Mohanty S., Nayak S.K., Synthesis and characterization of vegetable oil based polyurethane derived from low viscous bio aliphatic isocyanate: Adhesion strength to wood-wood substrate bonding. Macromol. Res., 2017, 25, 772-778.10.1007/s13233-017-5080-2Suche in Google Scholar

9 Li Y., Luo X., Hu S., Bio-based polyols and polyurethanes. Springer, New York, 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-21539-6Suche in Google Scholar

10 Taherimehr M., Pescarmona P.P., Green polycarbonates prepared by the copolymerization of CO2 with epoxides. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2014, 131, 41141-41158.10.1002/app.41141Suche in Google Scholar

11 Zahn J.A., Maximizing bio-based content and performance in reactive hot-melt adhesives. PU Magazine International, 2016, 13, 106-111.Suche in Google Scholar

12 Orgilés-Calpena E., Arán-Aís F., Torró-Palau A.M., Orgilés-Barceló C., Novel polyurethane reactive hot melt adhesives based on polycarbonate polyols derived from CO2 for the footwear industry. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes., 2016, 70, 218-224.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2016.07.009Suche in Google Scholar

13 Liu Z.H., Huang J.Q., Sun L.J., Lei D., Cao J., Chen S., et al., PPC-based reactive hot melt polyurethane adhesive (RHMPA)-Efficient glues for multiple types of substrates. Chinese J. Polym. Sci., 2018, 36, 58-64.10.1007/s10118-018-2011-4Suche in Google Scholar

14 Jeong J.H., Han Y., Yang J., Kwak D., Jeong H., Waterborne polyurethane modified with poly(ethylene glycol) macromer for waterproof breathable coating. Prog. Org. Coat., 2017, 103, 69-75.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2016.10.004Suche in Google Scholar

15 Zafar F., Sharmin E., Polyurethane: An Introduction. InTech, Croatia, 2012.10.5772/2416Suche in Google Scholar

16 Hepburn C., Polyurethane Elastomers. Springer, Netherlands, 1992.10.1007/978-94-011-2924-4Suche in Google Scholar

17 Jeong H.M., Ahn B.K., Cho S.M., Kim B.K., Water vapor permeability of shape memory polyurethane with amorphous reversible phase. J. Polym. Sci. B, 2000, 38, 3009-3017.10.1002/1099-0488(20001201)38:23<3009::AID-POLB30>3.0.CO;2-8Suche in Google Scholar

18 Li S., Vatanparast R., Vuorimaa E., Lemmetyinen H., Curing kinetics and glass-transition temperature of hexamethylene diisocyanate-based polyurethane. J. Polym. Sci. B, 2000, 38, 2213-2220.10.1002/1099-0488(20000901)38:17<2113::AID-POLB10>3.0.CO;2-KSuche in Google Scholar

19 Queiroz D.P., De Pinho, M.N., Dias C., ATR-FTIR studies of poly(propylene oxide)/polybutadiene bi-soft segment urethane/ urea membranes. Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 4195-4200.10.1021/ma034032tSuche in Google Scholar

20 Wang F.C., Feve M., Lam T.Y., Pascault J., FTIR analysis of hydrogen bonding in amorphous linear aromatic polyurethanes. I. Influence of temperature. J. Polym. Sci. B, 1994, 32, 1305-1313.10.1002/polb.1994.090320801Suche in Google Scholar

21 Lin C.L., Kao H.M., Wu R.R., Kuo P.L., Multinuclear solid-state NMR, DSC, and conductivity studies of solid polymer electrolytes based on polyurethane/poly(dimethylsiloxane) segmented copolymers. Macromolecules, 2002, 35, 3083-3096.10.1021/ma012012qSuche in Google Scholar

22 Stefanović I.S., Špírková M., Poręba R., Steinhart M., Ostojić S., Tešević V., et al., Study of the properties of urethane−siloxane copolymers based on Poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(dimethylsiloxane)-b-poly(propylene oxide) soft segments. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2016, 55, 3960-3973.10.1021/acs.iecr.5b04975Suche in Google Scholar

23 Kim M.G., No B.Y., Lee S.M., Nieh W.L., Examination of selected synthesis and room-temperature storage parameters for wood adhesive-type urea–formaldehyde resins by 13C-NMR spectroscopy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2003, 89, 1896-1917.10.1002/app.12367Suche in Google Scholar

24 Ishida M., Yoshinaga K., Solid-state 13C NMR analyses of the microphase-separated structure of polyurethane elastomer. Macromolecules, 1996, 29, 8824-8829.10.1021/ma960053uSuche in Google Scholar

25 Suresh K.I., Kishanprasad V.S., Synthesis, structure, and properties of novel polyols from cardanol and developed polyurethanes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2005, 44, 4504-4512.10.1021/ie0488750Suche in Google Scholar

26 Mishra V., Desai J., Patel K.I., (UV/Oxidative) dual curing polyurethane dispersion from cardanol based polyol: synthesis and characterization. Ind. Crop. Prod., 2018, 111, 165-178.10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.10.015Suche in Google Scholar

27 Mokeev M.V., Zuev V.V., Rigid phase domain sizes determination for poly(urethane–urea)s by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Correlation with mechanical properties. Eur. Polym. J., 2015, 71, 372-379.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.08.003Suche in Google Scholar

28 Phillips O., Schwartz J.M., Kohl P.A., Thermal decomposition of poly(propylene carbonate): End-capping, additives, and solvent effects. Polym. Degrad. Stab., 2016, 125, 129-139.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.01.004Suche in Google Scholar

29 Li H.C., Niu Y.S., Synthesis and characterization of amphiphilic block polymer poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(propylene carbonate)-poly(ethylene glycol) for drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C, 2018, 89, 160-165.10.1016/j.msec.2018.04.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Wong C.S., Badri K.H., Chemical analyses of palm kernel oil-based polyurethane prepolymer. Mater. Sci. Appl., 2012, 3, 78-86.10.4236/msa.2012.32012Suche in Google Scholar

31 Pereira I.M., Oréfice R.L., Study of the morphology exhibited by linear segmented polyurethanes. Macromol. Symp., 2011, 299/300, 190-198.10.1002/masy.200900080Suche in Google Scholar

32 Teo L.S., Chen C.Y., Kuo J.F, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study on effects of temperature on hydrogen bonding in amine-containing polyurethanes and poly(urethane-urea)s. Macromolecules, 1997, 30, 1793-1799.10.1021/ma961035fSuche in Google Scholar

33 Ren D., Frazier C.E., Structure–property behavior of moisturecure polyurethane wood adhesives: Influence of hard segment content. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes., 2013, 45, 118-124.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2013.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

34 Chattopadhyay D.K., Sreedhar B., Raju V.K., The phase mixing studies on moisture cured polyurethane-ureas during cure. Polymer, 2006, 47, 3814-3825.10.1016/j.polymer.2006.03.092Suche in Google Scholar

35 Cheremisinoff N.P., Handbook of polymer science and technology volume 2: performance properties of plastics and elastomers. CRC Press, Basel, 1989.Suche in Google Scholar

36 Gu S., Jana S., Effects of Polybenzoxazine on shape memory properties of polyurethanes with amorphous and crystalline soft segments. Polymer, 2014, 6, 1008-1025.10.3390/polym6041008Suche in Google Scholar

37 Yang J.M., Lin H.T., Yang S.J., Evaluation of poly(n-isopropylac-rylamide) modified hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene based polyurethane membrane. J. Membrane Sci., 2005, 258, 97-105.10.1016/j.memsci.2005.02.033Suche in Google Scholar

38 Meng Q.B., Lee S., Nah C., Lee Y., Preparation of waterborne polyurethanes using an amphiphilic diol for breathable waterproof textile coatings. Prog. Org. Coat., 2009, 66, 382-386.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2009.08.016Suche in Google Scholar

39 Jiang H., Zheng Z., Song W., Wang X., Moisture-cured polyurethane/polysiloxane copolymers: Effects of the structure of polyester diol and NCO/OH ratio. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2008, 108, 3644-3651.10.1002/app.27343Suche in Google Scholar

40 Tang Q., He J., Yang R., Ai Q., Study of the synthesis and bonding properties of reactive hot-melt polyurethane adhesive. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2013, 128, 2152-2161.10.1002/app.38415Suche in Google Scholar

41 Bajsic E.G., Rek V., Sendijarevic A., Sendijarevitfc V., Frish K.C., The effect of different molecular weight of soft segments in polyurethanes on photooxidative stability. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 1996, 52, 223-233.10.1016/0141-3910(95)00231-6Suche in Google Scholar

42 Petrie E.M., Handbook of adhesives and sealants. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

43 Tanaka H., Kunimura M., Mechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethanes containing aliphatic polycarbonate soft segments with different chemical structures. Polym. Eng. Sci., 2002, 42, 1333-1349.10.1002/pen.11035Suche in Google Scholar

44 García-Pacios V., Colera M., Iwata Y., Martin-Martinez J.M., Incidence of the polyol nature in waterborn polyurethane dispersions on their performance as coatings on stainless steel. Prog. Org. Coat., 2013, 76, 1726-1729.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2013.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

45 Kozakiewicz J., Rokicki G., Przybylski J., Sylwestrzak K., Studies of the hydrolytic stability of poly(urethaneeurea) elastomers synthesized from oligocarbonate diols. Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2010, 95, 2413-2420.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.08.017Suche in Google Scholar

46 Geiß P.L., Klingen J., Schröder B., Adhesive bonding materials, applications and technology. Wiley-VCH, Verlag, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Chung et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die