Abstract

To exploit the application of calcium montmorillonite (CaMt) and improve the flame resistance of polystyrene (PS), two kinds of long carbon chain quaternary ammonium bromides with different spatial effect (i.e., cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and didodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB)) were used to intercalate CaMt for yielding corresponding organic calcium montmorillonite (CaOMt). The PS nanocomposites containing CaOMt (PS/CaOMt) were prepared by melt blending method. The effects of CaOMt on flame resistance, thermal stability, tensile properties and interfacial adhesion of PS/CaOMt were investigated. The results showed that both CTAB and DDAB were intercalated into CaMt to get CaOMt with an exfoliated/intercalated structure, which could endue good interfacial adhesion and thermal stability for PS/CaOMt. All peak values of flame resistance parameters of PS/CaOMt decreased and corresponding combustion times were postponed obviously. Moreover, Young’s modulus of DDAB-intercalated PS/CaOMt was improved by 49.1% while its tensile strength kept at the same level as PS.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Polystyrene (PS) is widely used in thermal insulation, construction products, consumer appliances, packaging and lighting indication, etc., owing to its excellent mechanical, clarity, solvent resistance, heat resistance, electrical insulation and convenience of processing and molding (1, 2, 3). However, PS is easy to be ignited and dripped seriously during combustion process, which limits its applications. Halogen-containing flame retardants could greatly improve the flame retardancy of PS, but its combustion products are harmful to environment and people health. Therefore, halogen-free flame retardants, including phosphorus-nitrogen compounds (4), metal hydroxides (5), carbon nanoadditives (6, 7, 8, 9) and layered materials (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17), have been developed extensively to enhance flame-retardant of polymer.

The Montmorillonite is a crystalline 2:1 layered clay mineral with high specific surface and a central alumina octahedral sheet sandwiched between two silica tetrahedral sheets. Many researchers have focused on sodium montmorillonite (NaMt) widely in improving the flame retardancy of polymers. However, the hydrophilic surface of NaMt leads to a poor dispersion in polymers (18). To improve the dispersibility of montmorillonite in polymers, organic alkyl ammonium or phosphonium salts have been usually used to obtain organic sodium montmorillonite (NaOMt) based on the exchangeable ions (19,20). Recently, the effects of NaOMt or organic iron montmorillonite (FeOMt) on the flame retardancy of polymers have been investigated (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). A PS/magnesium hydroxide/NaOMt composite was prepared by melt method, and such composite produced a more continuous and compact charred residue layer after combustion than PS/magnesium hydroxide composite (27). Also, a PS/NaOMt composite with well flame retardant and smoke suppressing performances was obtained (28). It was also found that FeOMt could improve the flame retardancy of polymer composites due to the free radical trapping effect of Fe3+. The influence of FeOMt on smoke suppression properties of flame-retardant epoxy was investigated and the results showed that the heat release rate (HRR) and smoke production rate (SPR) of samples decreased significantly with increasing the FeOMt contents (29). It should be noted that pristine calcium montmorillonite (CaMt) was a main forms of natured montmorillonite minerals, which is far more than sodium or iron montmorillonite. Until now, the CaMt is mainly used as the adsorbent (30,31), buffer materials (32), reinforcement filler (33), etc. A few efforts have tried to improve the flame retardancy of polymer composites by the CaMt. For example, the organic CaMt (CaOMt) was attempted to incorporate in the PS. However, the flame resistance of PS/CaOMt was slightly improved; meanwhile, the initial decomposition temperature of PS/CaOMt was very close to that of pure PS (34). Additionally, the influence of CaOMt on tensile properties of PS nanocomposites was not reported. Ammonium polyphosphate- modified CaMt (APP-CaMt) was incorporated into polypropylene (PP) to prepare a PP/APP-CaMt composite with good flame retardancy (35). However, no detail proofs on dispersion and exfoliation of the APP-CaMt and its interfacial adhesion in polymer were presented. Furthermore, the long chain quaternary ammonium salts with different spatial effect have not been mentioned in modifying CaMt in the above literatures also.

In this study, we are interested in using long chain quaternary ammonium salts with different spatial effect as an intercalator to get CaOMt and developing an application of CaOMt to improve the flame resistance of PS. For achieving these purposes, the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and didodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB) were used to modify CaMt to get corresponding CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, respectively. Subsequently, the dispersion and exfoliation of CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d in PS and the interfacial adhesion, thermal properties and flame resistance of corresponding PS/CaOMt nanocomposites were investigated in detail.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

CaMt (with methylene blue absorption > 37 mmol/100 g, purity about 85%) was supplied by Zhejiang Feng Hong New Materials Co. Ltd. The CTAB and DDAB were produced by Chengdu Ke Long Chemical Reagent Factory. PS resin (PG-383) was produced by Taiwan Chimei Industrial factory.

2.2 Preparation of the CaOMt

The preparation procedure of CaOMt (using CTAB as an example) was as follows.

First, CaMt (60 g) was added into distilled water (600 mL) and stirred at 80°C for 30 min to obtain the CaMt suspension. The CTAB (21.6 g) was dissolved in distilled water (120 mL) to obtain the CTAB solution, and such solution was added into the CaMt suspension, stirred at the rotor rate of 500 rpm for 2 h and then stood for 24 h. Subsequently, the precipitate was filtered and washed with ethanol until the CTAB was completely removed (no precipitation would yield when 0.1 mol/ L AgNO3 solution was added dropwise into the filtrate). After drying in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 72 h, the mixture was put into a ball mill (350 rpm) for 4 h (200 mesh) to obtain the CaOMt powders modified by CTAB, marked as CaOMt-c.

According to the similar conditions, 27.6 g DDAB was added into above CaMt suspensions, and the CaOMt powders modified by DDAB was prepared and marked as CaOMt-d.

2.3 Preparation of PS nanocomposites

The preparation procedure of PS nanocomposites containing CaOMt-c (PS/CaOMt-c), as an example, was as follows. First, CaOMt-c and PS were pre-dried at 80°C for 24 h and 1.5 h, respectively. Then the dried CaOMt-c (240 g) was mixed with the dried PS (4800 g), and the mixture was fed into the running rollers of the three-roll mill machine with the processing parameter set at 180°C and 45 rpm for 12 min. After several extrusions, a sheet of the PS/CaOMt-c with a good distribution of CaOMt-c was obtained.

Following the same procedure, the PS nanocomposites containing CaOMt-d (PS/CaOMt-d) or CaMt (PS/CaMt) were prepared, respectively.

2.4 Characterization

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Vertex 80v, Bruker, Germany) was employed to detect the changes of the functional groups on the CaOMt surface, and the wave numbers were recorded from 500 to 4000 cm−1. The structural changes of CaOMt and corresponding PS composites were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD; D8, Bruker, Germany) at room temperature with Cu-target Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm). The distribution of CaOMt in PS was characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-1400, JEOL, Japan) operated at 200 kV.

Tensile tests were conducted at room temperature with an electronic universal testing instrument (TCS-2000, Dongguan, China) according to ASTM D638. All of the material types were evaluated five times to reduce the experimental error. The thermal stability was verified by Netzsch STA409 PC thermo analyzer instrument under air. A temperature ramp experiment (10°C/min) was conducted from 30°C to 600°C. The combustion properties of the PS nanocomposites were evaluated with a cone calorimetry experiment. All of the samples (100 × 100 × 3 mm3) were exposed to a FTT 0007 cone calorimeter (FTT Company, England) under a heat flux of 50 KW/m2 according to ISO-5660 standard procedures. The temperature of conical head is at 720°C.

A field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S-4800, Hitachi, Japan) was used to examine the distribution state of CaOMt in the matrix and the structure morphology of the residues. The element analysis of char residues was evaluated by energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX; EX-250, Horiba, Japan). All the observed specimens were plated.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Modification and structure

3.1.1 Surface composition and structure of CaOMt

Long chain alkyl quaternary ammonium salt was used to intercalate CaMt and to improve its compatibility with PS. The surface compositions of the CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d were analyzed by FTIR spectra, as shown in Figure 1. The interlayer structures of the CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d were described by the (001) diffraction peaks (d001) and investigated by XRD patterns, as plotted in Figure 2. The spacing d001 values of CaOMt and their relative CaMt were calculated and listed in Table 1.

FTIR spectra of CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d.

XRD patterns of CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d.

The d 001 values of Mt powders and PS nanocomposites.

| Sample | Mt powders | PS nanocomposites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2π (°) | d001(nm) | 2π(°) | d001(nm) | |

| CaMt | 5.8 | 1.51 | 6.1 | 1.45 |

| CaOMt-c | 4.7 | 1.88 | 5.8 | 1.51 |

| CaOMt-d | − | − | 5.2 | 1.69 |

From Figure 1, the peaks at 2923 cm-1 and 2851 cm-1 are observed in CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, which are assigned to the asymmetric stretching and bending vibration peaks of -CH2- and CH3-; moreover, the peak at 1465 cm-1 observed only in CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d should be assigned to asymmetric bending vibration of CH3- and shear vibration of -CH2-. However, all the above peaks are not found in CaMt. These results indicated that the CaMt was successfully modified by CTAB or DDAB, and a hydrophobic surface was formed on the CaMt.

As seen in Figure 2, compared with initial CaMt, the diffraction angles (2θ) at d001 peaks of CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d are shifted to lower angles; especially, the diffraction peak of CaOMt-d disappears. These results demonstrated that both CTAB and DDAB were intercalated into CaMt successfully. The DDAB should be a better intercalation in CaMt than CTAB, due to two long alkyl chains of DDAB.

3.1.2 Structure and interface of the PS/CaOMt nanocomposites

To evaluate the structure of CaOMt in PS nanocomposites, XRD patterns of the PS, PS/CaMt and PS/CaOMt were plotted in Figure 3. The spacing d001 values of the PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d according Bragg Equation were calculated and recorded in Table 1.

XRD patterns of PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

From Figure 3 and Table 1, with the addition of CaMt, the d001 peak of PS/CaMt at 2θ is about 6.1°, and the corresponding d001 value is 1.45 nm, which is less than initial CaMt (1.51 nm). With the addition of CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, the 2θ at d001 peaks of PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are 5.8° and 5.2°, respectively, which are shifted to lower angles. The corresponding spacing d001 values of PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are 1.51 nm and 1.69 nm, respectively.

This result indicated that the spacing d001 values of PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d were lower than those of CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d. This should be due to more difficult dispersion of CaMt or CaOMt in melted PS and even be bound by the PS matrix, leading to the aggregation in matrix. Furthermore, the spacing d001 values of PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d were larger than that of original CaMt, suggesting the formation of an intercalated structure of CaOMt in the PS/CaOMt, especially for the PS/CaOMt-d.

3.2 Flame-retardant properties

A cone calorimeter is an effective bench-scale apparatus for studying the flammability properties of materials in simulating real fire scenarios. Heat release rate (HRR), smoke production rate (SPR), mass loss rate (MLR), carbonic oxide release rate (CORR), and time to ignition (TTI) are important hazardous indexes to evaluate the flammability of polymer composites.

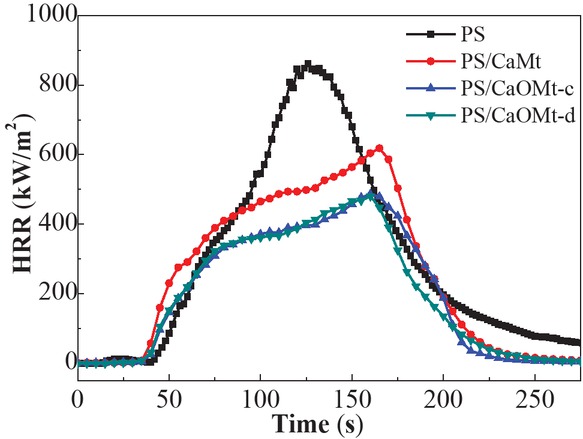

3.2.1 Heat release rate

The peak value of HRR (PHRR) can be usually considered as the driving force of the fire. Figure 4 shows the HRR curves of pure PS, PS/CaMt and PS/CaOMt nanocomposites as a function of time.

HRR curves of PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

As seen in Figure 4, the PHRR values of PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are reduced obviously by 26.5%, 42.2% and 42.9%, respectively, as compared with that of PS. Meanwhile, the combustion times reaching to the PHRR are postponed from 126 s for PS to about 162 s for other three PS nanocomposites, and a retardation of about 36 s is obtained. Furthermore, the total amount of heat release of three PS nanocomposites are smaller than PS; thereinto, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d nanocomposites exhibit lower total amount of heat release than PS/CaMt. This proved that either CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d could be helpful to depress the heat release of PS nanocomposites.

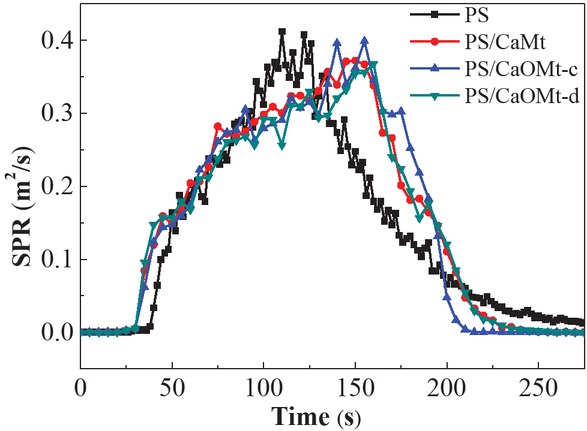

3.2.2 Smoke production rate

The SPR is one of the important indexes to reflect smoke suppression properties of polymer composites. Excellentsmoke suppression properties of materials play an important role in fire rescue. Figure 5 shows the SPR curves of pure PS and its nanocomposites with CaOMt or CaMt as a function of time.

SPR curves of PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

As observed in Figure 5, the PS/CaOMt or PS/CaMt nanocomposites have a slight drop in the peak value of SPR, in comparison to pure PS. The combustion time to peak SPR of PS/CaOMt-c or PS/CaOMt-d nanocomposites is postponed obviously from 110 s for the PS to about 160 s, corresponding delay times of about 50 s. Thereinto, the PS/CaOMt-d behaves a little better than the PS/CaOMt-c. On the whole, CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d could assist in improving the smoke suppression properties of PS nanocomposites.

3.2.3 CO release rate

The main reason of deaths in a fire is usually considered to be an inhalation of toxic gas rather than combustion itself. The CORR curves of pure PS, PS/CaMt and PS/CaOMt nanocomposites as a function of time are shown in Figure 6. It can be found in Figure 6 that the peak values of CORR of PS/CaMt and PS/CaOMt are decreased. Thereinto, a maximum drop is observed for PS/CaOMt-d, in comparison to that of the PS. Furthermore, the combustion times to peak CORR for PS/CaMt and PS/CaOMt are all postponed, compared with pure PS. Thereinto, the combustion times to peak value of the CO release rate are delayed by 44 s for PS/CaOMt-c and 55 s for PS/CaOMt-d, in comparison to pristine PS.

CORR curves of the PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

3.2.4 Time to ignition

Time to ignition (TTI) of a material is an important index in a cone test to evaluate a risk in a fire. All TTI data for pure PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are recorded in Table 2. It can be seen that with the addition of CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, the TTI data of PS nanocomposites are extended by 7 s∼14 s, compared with pure PS. The longest TTI is obtained for PS/CaOMt-d in all the cases.

Cone calorimeter data of PS and its nanocomposites.

| Sample | TTI | PHRR | PMLR | PSPR | PCORR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (s) | (kw/m2) | (g/s) | (m2/s) | (g/s) | |

| PS | 36 | 841.7 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.025 |

| PS/CaMt | 43 | 618.1 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.023 |

| PS/CaOMt-c | 45 | 486.2 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.023 |

| PS/CaOMt-d | 50 | 480.5 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.021 |

3.2.5 Mass loss rate

The thermal stability of a material is concerned with its MLR, which can reflect the burning rate of polymer composites. The MLR curves of pure PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d as a function of time were plotted in Figure 7.

MLR curves of the PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

From Figure 7, the wave curves at the front of the wave of MLR and the peak values for PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are all lower than those of pure PS. All the combustion times to peak MLR for PS nanocomposites containing CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d are delayed by about 44 s, as compared with that of pure PS.

Based on the above discuss by cone tests, it can be concluded that, (1) the flame retardancy of pure PS could be improved with the addition of CaMt or CaOMt, whether organically modified or not; (2) the CaOMt with organic modification was more beneficial than original CaMt in enhancing the flame retardancy of pure PS, owing to well distribution and effective intercalation of CaOMt in PS matrix; (3) the CaOMt-d with two long alkyl chains DDAB modifier could endow PS/CaOMt-d with an excellent flame retardancy.

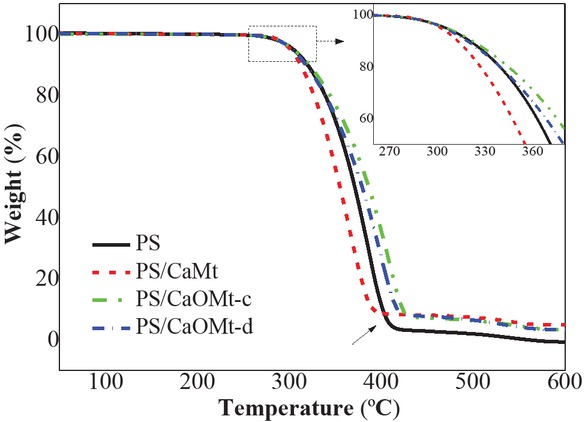

3.3 Thermo gravimetric analysis

To further testify the effect of the CaOMt on the thermal stability of PS nanocomposites, TGA curves of pure PS and its nanocomposites were tested and plotted in Figure 8. The relevant thermal decomposition temperatures were listed in Table 3, such as the onset decomposition temperature at 10% weight loss (T0.1), the final decomposition temperature at stable weight loss (Tf), and the char residues at 600°C.

TGA curves of PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

TGA data of the pure PS and the PS nanocomposites.

| Sample | Weight loss temperature (°C) | 600°C Char (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0.1 | Tf | ||

| PS | 318 | 415 | 1.4 |

| PS/CaMt | 311 | 394 | 4.6 |

| PS/CaOMt-c | 321 | 429 | 3.3 |

| PS/CaOMt-d | 327 | 422 | 2.8 |

The TGA curves show three weight loss stages in Figure 8. At the first stage, the weight loss is about 10% at T0.1, which is due to the volatilization of water existed in interlayer of montmorillonite and organic modifier. The second stage, the weight drops greatly in very short temperature range, because of the thermal decomposition of the PS. The last stage, the weight tends to a stable value at Tf.

As shown in Table 3, with the addition of CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, the T0.1 and Tf of corresponding PS nanocomposites increase. However, with the addition of CaMt, T0.1 and Tf of corresponding PS nanocomposites decrease, which may be owing to more water in interlayer of CaMt and more space in PS/CaMt. In addition, the char yield at 600°C of PS nanocomposites remains higher than that of PS.

3.4 Mechanical properties

To further evaluate the effect of nanofillers on mechanical properties of PS nanocomposites, the tensile strength and Young’s modulus of pure PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are shown in Figure 9.

(a) tensile strength and Young’s modulus and (b) elongation at break of PS, PS/CaMt, PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d.

Figure 9a shows that either CaMt or CaOMt can enhance Young’s modulus of corresponding PS nanocomposites, while the tensile strengths of PS nanocomposites with CaOMt are not reduced, compared with pure PS. Thereinto, Young’s modulus of PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d are improved by 31.3% and 49.1%, respectively; meanwhile, the tensile strength of PS/CaOMt-d keeps at the same level as pure PS. As shown in Figure 9b the elongation at break of PS nanocomposites is reduced due to the incorporation of CaMt and CaOMt. Thereinto, the elongation at break of PS/CaOMt-d reach maximum value of 8.5%. These results indicated that excellent dispersion of CaOMt-d in PS and outstanding adhesion in the PS/CaOMt-d could be expected.

3.5 Interfacial adhesion and flame retardant mechanism

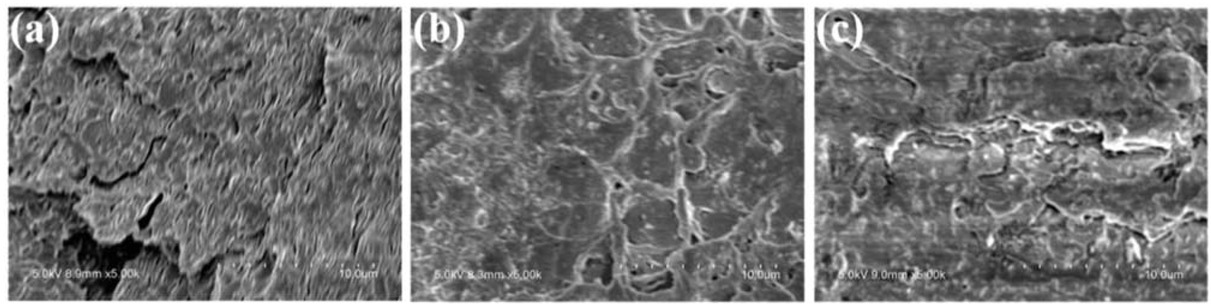

3.5.1 Interfacial adhesion

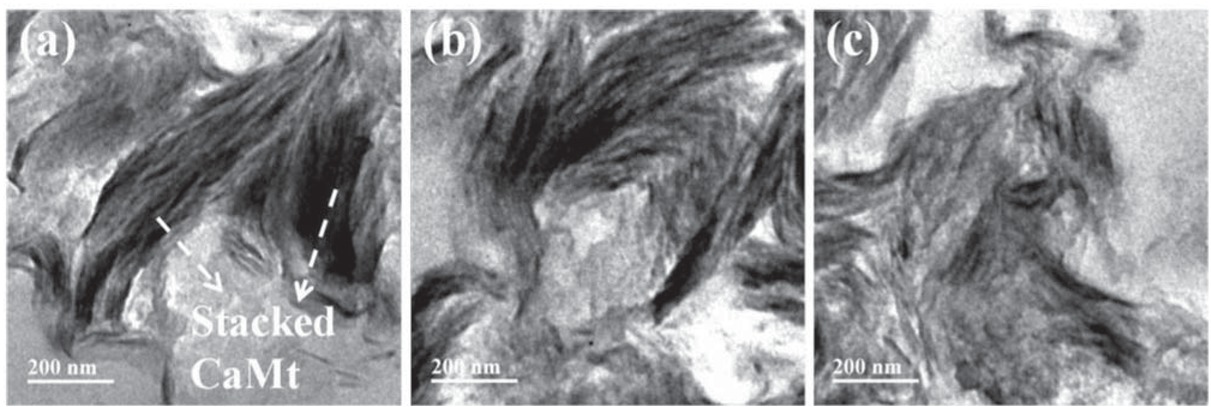

To further explain the dispersion and interfacial adhesion of CaMt, CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d with PS, the cross-section of corresponding PS nanocomposites after tensile tests were performed by SEM under a magnification of 5000 × and further observed by TEM, as shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively.

SEM images of (a) PS/CaMt; (b) PS/CaOMt-c; (c) PS/CaOMt-d.

TEM images of (a) PS/CaMt; (b)PS/CaOMt-c; (c)PS/CaOMt-d.

It is clearly observed that roughly coarse reticular structures are presented on the cross-section of PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d in Figures 10b and 10c especially for the PS/CaOMt-d with rough and irregular structures. However, the relatively smooth fine lines are observed on the cross-section of PS/CaMt in Figure 10a It showed that the CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d in the PS was of an exfoliated flake structure, good dispersion, and good interfacial adhesion with PS matrix.

The interlayer combination of PS/CaOMt-d is tougher than that of PS/CaOMt-c. As a comparison, the CaMt in the PS is stacked more seriously than the CaOMt-c or CaOMt-d. These results were verified further by TEM images in Figure 11. The CaMt stacks with the least tripped structure in Figure 11a compared with CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d. The CaOMt-d (Figure 11c) owns more sufficient tripping structure than the CaOMt-c (Figure 11b) These were also consistent with the conclusion from Figure 9 and the XRD analysis.

3.5.2 Flame retardant mechanism

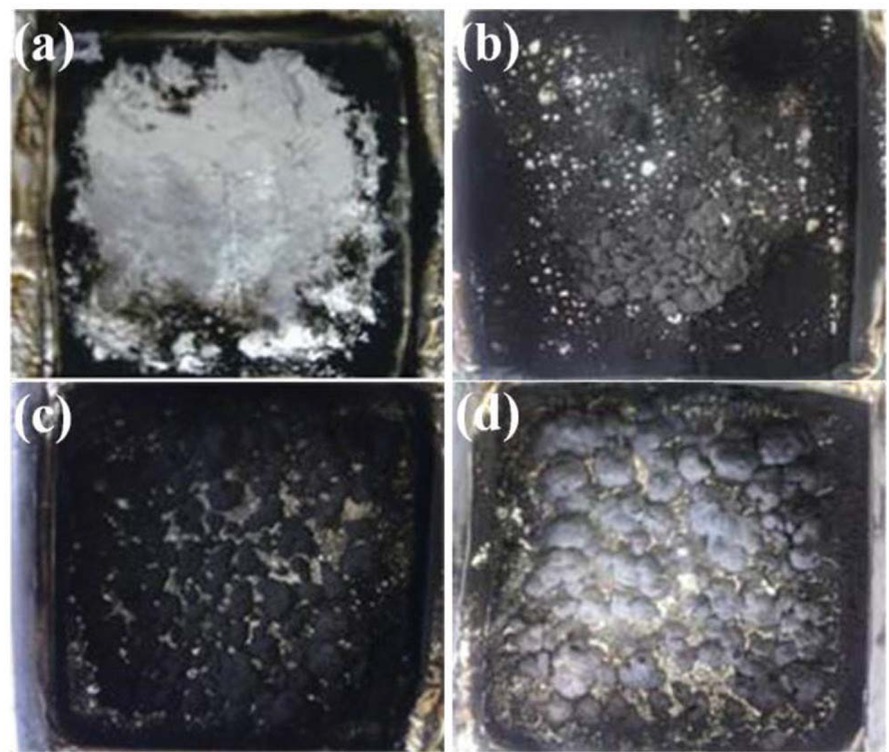

To further explore how the CaOMt or CaMt enhanced flame resistance of PS nanocomposites, the char residues of PS nanocomposites were collected after cone calorimetry test to discuss the relationship of the morphology and composition of char residues of CaOMt or CaMt with flame retardancy effect. Their macroscopic morphologies observed by digital camera were pictured in Figure 12. Their microscopic morphologies investigated by

Char residues of (a) PS; (b) PS/CaMt; (c) PS/CaOMt-c; (d) PS/CaOMt-d.

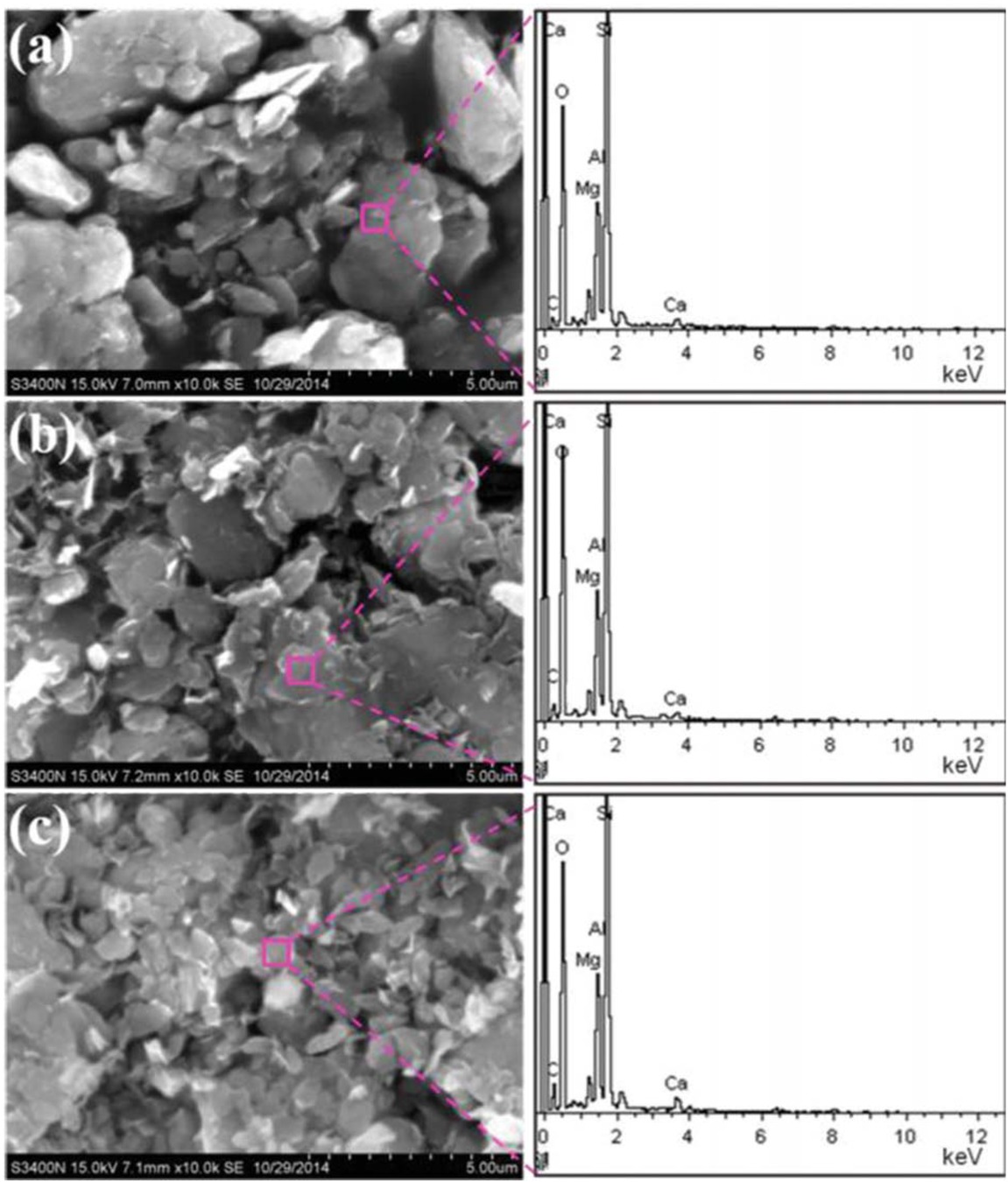

SEM under a magnification of 10,000 × were pictured in Figure 13 and corresponding elemental compositions were analyzed by EDX spectrums and collected in Table 4.

SEM images and EDX spectrums of char residues of (a) PS/CaMt; (b) PS/CaOMt-c; (c) PS/CaOMt-d.

EDX data of char residues of the PS nanocomposites.

| Sample | Mass fraction (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | Ca | Si | Al | Mg | |

| PS/CaMt | 5.87 | 49.14 | 1.39 | 30.55 | 10.27 | 2.78 |

| PS/CaOMt-c | 9.80 | 51.49 | 0.95 | 27.08 | 8.81 | 1.87 |

| PS/CaOMt-d | 11.99 | 49.74 | 2.02 | 25.45 | 8.98 | 1.82 |

It is found that some large granularity char residue granules are homogeneously scattered in Figures 12c and 12d, while some uneven fineness powders are shown in Figure 12b and complete combustion is observed in Figure 12a These results indicated that the CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d had good charring forming abilities and expandability.

To further understand the structure morphologies of these char residues, the SEM images were observed under a magnification of 10,000 × in Figure 13. It is found that all char residue granules in Figures 13a-c are of a lamellated structure, thereinto, the largest number lamellated structure for PS/CaOMt-d is found in Figure 13c followedby that for PS/CaOMt-c in Figure 13b Meanwhile, the accumulated bulky grains in Figure 13a are more than those in Figures 13b and 13c

From Table 4, it is found that both CTAB and DDAB can change the elemental composition of CaMt; the percentage of C in char residues of PS nanocomposites follows an order of PS/CaOMt-d > PS/CaOMt-c > PS/CaMt. The PS/CaOMt-d had the best incarbonization in all the cases. This is because the DDAB had two long carbon chains with obvious spatial effect and thus enlarged the interlayer spacing of CaMt effectively, resulting in the enhancement of flame resistance.

To summarize the above, flame retardant mechanism can be concluded that, (1) the lamellated structure (see Figure 13) could formed an impermeable char network as an insulating barrier, blocking the diffusion of heat or oxygen into the composites and decreasing the release of toxic gases in a fire; (2) the DDAB with obvious spatial effect was more helpful to make the pristine CaMt stripped and to get a sufficient ion exchange than the CTAB; (3) excellent peeling structure of CaOMt-d or CaOMt-c endow an improved flame resistance of PS nanocomposites.

4 Conclusions

In this study, two long chain alkyl quaternary ammonium salts (CTAB and DDAB) with different spatial effects were used to modify the CaMt, respectively. The corresponding PS/CaOMt-c and PS/CaOMt-d nanocomposites were prepared via melt blending process. The effects of CaOMt on the flame resistance, thermal stabilities, mechanical properties and interfacial adhesion were systematically evaluated. Some interesting findings have been obtained as follows:

Both CTAB and DDAB could be successfully intercalated into the interlayer of CaMt to get CaOMt with a mixed exfoliated/intercalated structure. Good dispersion and compatibility of the PS/CaOMt were achieved. The CaOMt-d was the best choice in improving the properties of PS nanocomposites.

All the peak values of HRR, SPR, MLR and CORR of PS/CaOMt decreased and their corresponding combustion times to peak values were postponed obviously. Thereinto, with the addition of CaOMt-d, the peak value of heat release rate for PS/CaOMt-d was reduced by 42.9%, and its combustion time to peak values was significantly delayed by 14 s, compared with pure PS.

Young’s modulus of the PS/CaOMt increased obviously, compared with pure PS. Thereinto, Young’s modulus of the PS/CaOMt-d was improved by 49.1%. Meanwhile, tensile strength kept at the same level as pure PS and the elongation at break of PS/CaOMt-d reached 8.5%. This indicated a good interfacial adhesion in PS/CaOMt-d.

Beside the lamellate structure and incarbonization of CaOMt-c and CaOMt-d, larger spatial effect of the DDAB also contributed to enhancing the flame resistance of PS nanocomposites effectively.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (grant number 2018B40814).

References

1 Ali W., Kausar A., Iqbal T., Reinforcement of high performance polystyrene/polyamide/ polythiophene with multi-walled carbon nanotube obtained through various routes. Compos Interface, 2015, 22(9), 885-897.10.1080/09276440.2015.1076251Suche in Google Scholar

2 Chylińska M., Zieglerborowska M., Kaczmarek H., Burkowska A., Walczak M., Kosobucki P., Synthesis and biocidal activity of novel N-halamine hydantoin-containing polystyrenes. e-Polymers, 2014, 14(1), 15-25.10.1515/epoly-2013-0010Suche in Google Scholar

3 Brostow W., Grguric T.H., Olea-Mejia O., Pietkiewicz D., Rek V., Polypropylene + Polystyrene Blends with a Compatibilizer. Part 2. Tribological and Mechanical Properties. e-Polymers, 2013, 8(1), 364-375.10.1515/epoly.2008.8.1.364Suche in Google Scholar

4 Liu J., Peng S., Zhang Y., Chang H., Yu Z., Pan B., et al., Influence of microencapsulated red phosphorus on the flame retardancy of high impact polystyrene/magnesium hydroxide composite and its mode of action. Polym Degrad Stabil, 2015, 121, 208-221.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.09.011Suche in Google Scholar

5 Yan Y.W., Huang J.G., Guan Y.H., Shang K., Jian R.K., Wang Y.Z., Flame retardance and thermal degradation mechanism of polystyrene modified with aluminum hypophosphite. Polym Degrad Stabil, 2014, 99(1), 35-42.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.12.014Suche in Google Scholar

6 Kausar A., Muhammad W.U., Bakhtiar, Processing and characterization of fire-retardant modified polystyrene/functional graphite composites. Compos Interface, 2015, (6), 517-530.10.1080/09276440.2015.1049860Suche in Google Scholar

7 Han Y., Wang T., Gao X., Li T., Zhang Q., Preparation of thermally reduced graphene oxide and the influence of its reduction temperature on the thermal, mechanical, flame retardant performances of PS nanocomposites. Compos Part A-Appl S, 2016, 84, 336-343.10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.02.007Suche in Google Scholar

8 Xing W., Wang X., Song L., Hu Y., Enhanced thermal stability and flame retardancy of polystyrene by incorporating titanium dioxide nanotubes via radical adsorption effect. Compos Sci Technol, 2016, 133, 15-22.10.1016/j.compscitech.2016.07.013Suche in Google Scholar

9 Zhou K., Gui Z., Hu Y., The influence of graphene based smoke suppression agents on reduced fire hazards of polystyrene composites. Compos Part A-Appl S, 2016, 80, 217-227.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.10.029Suche in Google Scholar

10 Lu C., Gao X.P., Yang D., Cao Q.Q., Huang X.H., Liu J.C., et al., Flame retardancy of polystyrene/nylon-6 blends with dispersion of clay at the interface. Polym Degrad Stabil, 2014, 107(4), 10-20.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.04.028Suche in Google Scholar

11 Nagendra B., Das A., Leuteritz A., Gowd E.B., Structure and crystallization behaviour of syndiotactic polystyrene/layered double hydroxide nanocomposites. Polym Int, 2016, 65(3), 299-307.10.1002/pi.5055Suche in Google Scholar

12 Ahmed L., Zhang B., Hawkins S., Mannan M.S., Cheng Z., Study of thermal and mechanical behaviors of flame retardant polystyrene-based nanocomposites prepared via in-situ polymerization method. J Loss Prevent Proc, 2017, 49.10.1016/j.jlp.2017.07.003Suche in Google Scholar

13 Zhou K., Tang G., Gao R., Guo H., Constructing hierarchical polymer@MoS2 core-shell structures for regulating thermal and fire safety properties of polystyrene nanocomposites. Compos Part A-Appl S, 2018, 107, 144-154.10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.12.026Suche in Google Scholar

14 Zhou K., Tang G., Gao R., Jiang S., In situ growth of 0D silica nanospheres on 2D molybdenum disulfide nanosheets: Towards reducing fire hazards of epoxy resin. J Hazard Mater, 2018, 344, 1078-1089.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.11.059Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Zhou K., Liu C., Gao R., Polyaniline: A novel bridge to reduce the fire hazards of epoxy composites. Compos Part A-Appl S, 2018, 112, 432-443.10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.06.031Suche in Google Scholar

16 Zhou K., Gao R., Qian X., Self-assembly of exfoliated molybdenum disulfide (MoS2 nanosheets and layered double hydroxide (LDH): Towards reducing fire hazards of epoxy. J Hazard Mater, 2017, 338, 343-355.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.05.046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17 Kong Q., Wu T., Zhang J., Wang D.Y., Simultaneously improving flame retardancy and dynamic mechanical properties of epoxy resin nanocomposites through layered copper phenylphosphate. Compos Sci Technol, 2018, 154, 136-144.10.1016/j.compscitech.2017.10.013Suche in Google Scholar

18 Tabsan N., Suchiva K., Wirasate S., Effect of montmorillonite on abrasion resistance of SiO2-filled polybutadiene. Compos Interface, 2012, 19(1), 1-13.10.1080/09276440.2012.687564Suche in Google Scholar

19 Zhang Z., Han Y., Li T., Wang T., Gao X., Liang Q., et al., Polyaniline/montmorillonite nanocomposites as an effective flame retardant and smoke suppressant for polystyrene. Synthetic Met, 2016, 221(Supplement C), 28-38.10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.10.009Suche in Google Scholar

20 Taheri N., Sayyahi S., Effect of clay loading on the structural and mechanical properties of organoclay/HDI-based thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposites. e-Polymers, 2016, 16(1), 65-73.10.1515/epoly-2015-0130Suche in Google Scholar

21 Wang J., Sun K., Hao W., Du Y., Pan C., Structure and properties research on montmorillonite modified by flame-retardant dendrimer. Appl Clay Sci, 2014, 90(Supplement C), 109-121.10.1016/j.clay.2014.01.001Suche in Google Scholar

22 Sanchez-Olivares G., Sanchez-Solis A., Calderas F., Medina-Torres L., Manero O., Di Blasio A., et al., Sodium montmorillonite effect on the morphology, thermal, flame retardant and mechanical properties of semi-finished leather. Appl Clay Sci, 2014, 102(Supplement C), 254-260.10.1016/j.clay.2014.10.007Suche in Google Scholar

23 Wang J., Su X., Mao Z., The flame retardancy and thermal property of poly (ethylene terephthalate)/cyclotriphosphazene modified by montmorillonite system. Polym Degrad Stabil, 2014, 109(Supplement C), 154-161.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.07.010Suche in Google Scholar

24 Chang M.K., Huang S.S., Liu S.P., Flame retardancy and thermal stability of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer nanocomposites with alumina trihydrate and montmorillonite. J Ind Eng Chem, 2014, 20(4), 1596-1601.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.08.004Suche in Google Scholar

25 Phua Y.J., Lau N.S., Sudesh K., Chow W.S., Ishak Z.M., A study on the effects of organoclay content and compatibilizer addition on the properties of biodegradable poly(butylene succinate) nanocomposites under natural weathering. Appl Compos Mater, 2015, 49(8).10.1177/0021998314527328Suche in Google Scholar

26 Han Y., Li T., Gao B., Gao L., Tian X., Zhang Q., et al., Synergistic effects of zinc oxide in montmorillonite flame-retardant polystyrene nanocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci, 2016.10.1002/app.43047Suche in Google Scholar

27 Liu J., Zhang Y., Yu Z., Yang W., Luo J., Pan B., et al., Enhancement of organoclay on thermal and flame retardant properties of polystyrene/magnesium hydroxide composite. Polym Composite, 2016, 37(3), 746-755.10.1002/pc.23231Suche in Google Scholar

28 Zhang Z., Han Y., Li T., Wang T., Gao X., Liang Q., et al., Polyaniline/montmorillonite nanocomposites as an effective flame retardant and smoke suppressant for polystyrene. Synthetic Met, 2016, 221, 28-38.10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.10.009Suche in Google Scholar

29 Chen X., Liu L., Zhuo J., Jiao C., Qian Y., Influence of organic-modified iron-montmorillonite on smoke-suppression properties and combustion behavior of intumescent flame-retardant epoxy composites. High Perform Polym, 2015, 27(2), 623-633.10.1177/0954008314544341Suche in Google Scholar

30 Parolo E., Avena M., Saviani M., Baschini M., Nicotra V., Adsorption and circular dichroism of tetracycline on sodium and;calcium-montmorillonites. Colloid Surface A, 2013, 417(417), 57-64.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.10.060Suche in Google Scholar

31 Shah J., Jan M.R., Adnan. Metal decorated montmorillonite as a catalyst for the degradation of polystyrene. J Taiwan Inst Chem E, 2017.10.1016/j.jtice.2017.07.026Suche in Google Scholar

32 Suuronen J.P., Matusewicz M., Olin M., Serimaa R., X-ray studies on the nano-and microscale anisotropy in compacted clays: Comparison of bentonite and purified calcium montmorillonite. Appl Clay Sci, 2014, 101(Supplement C), 401-408.10.1016/j.clay.2014.08.015Suche in Google Scholar

33 Zeng S., Shen M., Yang L., Xue Y., Lu F., Chen S., Self-assembled montmorillonite-carbon nanotube for epoxy composites with superior mechanical and thermal properties. Compos Sci Technol, 2018.10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.04.035Suche in Google Scholar

34 Xue Y., Shen M., Lu F., Han Y., Zeng S., Chen S., et al., Effects of heterionic montmorillonites on flame resistances of polystyrene nanocomposites and the flame retardant mechanism. J Compos Mater, 2017.10.1177/0021998317724861Suche in Google Scholar

35 Yi D., Ye C., Yang R., Ammonium Polyphosphate-Calcium Montmorillonite Nanocompounds Flame Retarded Polypropylene. Polym Mater Sci Eng, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Lu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die