Abstract

In the past few decades, stem cell transplantation has been generally accepted as an effective method on the treatment of tissue and organ injury. However, the insufficient number of transplanted stem cells and low survival rate that caused by series of negative conditions limit the therapeutic effect. In this contribution, we developed an injectable hydrogel composed of sodium alginate (SA) and Type I collagen (ColI), as the tissue scaffold to create better growth microenvironment for the stem cells. Compared the traditional SA scaffold, the ColI/SA hydrogel inherits its biomimetic properties, and simultaneously has shorter gelation time which means less loss of the transplanted stem cells. The mesenchyma stem cell (MSC) culture experiments indicated that the ColI/SA hydrogel could prevent the MSC apoptosis and contributed to faster MSC proliferation. It is highlighted that this ColI/SA hydrogel may have potential application for tissue regeneration and organ repair as the stem cell scaffold.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Stem cell transplantation is generally accepted as one of the most effective methods for the clinical treatment of tissue and organ injury currently (1). However, stem cells loss and low cell viability after stem cell transplantation will count against better therapeutic effect (2). Therefore, it is essential to build an appropriate microenvironment for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of transplanted stem cells. Tissue engineering scaffolds plays crucial roles on building the growth microenvironment (3, 4, 5), and preparing the tissue engineering scaffolds with series of molecules is a hot spot of research presently (6). This technology has many advantage, including degradability, appropriate water content and mechanical property, and good biocompatibility (7). In this work, two natural molecules, sodium alginate and Type I collagen, were chosen to prepare an injectable and biocompatible hydrogel as the tissue engineering scaffold to provide appropriate microenvironment for stem cells growth. Sodium alginate (SA) is a traditional material for the injectable hydrogel, and it can slow down the absorption of fatty sugar and bile salt, reduce the serum cholesterol, triglyceride and blood sugar, and prevent hypertension, diabetes, obesity and other diseases (8). Type I collagen (ColI) is a kind of polysaccharide protein, which contains a small amount of galactose and glucose, and it is the main component of the extracellular matrix that improves cell growth and migration (9,10). We hope this ColI/SA functional hydrogel as the tissue engineering scaffold may provide more potential application on tissue regeneration and organ repair.

2 Materials and methods

Preparation of the ColI/SA hydrogel: The ColI/SA hydrogel was prepared by the interaction of SA, CaCO3, and ColI: In brief, SA (Sigma, USA) was dissolved in deionized water (dH2O) to create 1% and 2% solution, while ColI (Sigma, USA) was dissolved in acetate buffer (1M) to create 0.5% solution (pH 7.2); Then the ColI and SA solution were mixed with concentration ratios of 1:4 (Samples were labeled as SA4ColI1) or 1:2 (Samples were labeled as SA2ColI1); Next, the CaCO3 suspension and Gluconic acid lactone (GDL, Sigma-Aldrich) solution were introduced in the ColI/SA mixture to start the gel process (6); Finally, the ColI/SA hydrogels were obtained after 15 min reaction, and the single SA hydrogel prepared with the 2% solution was used as control in this study.

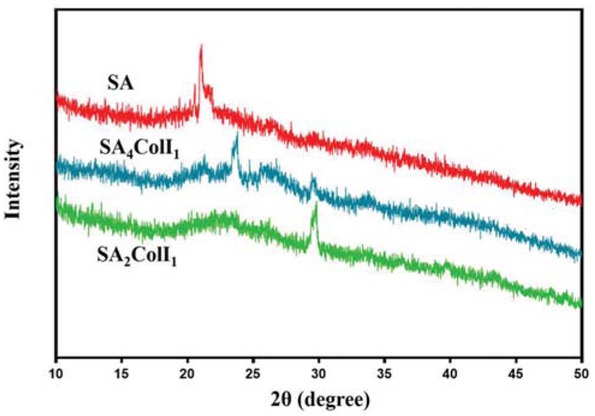

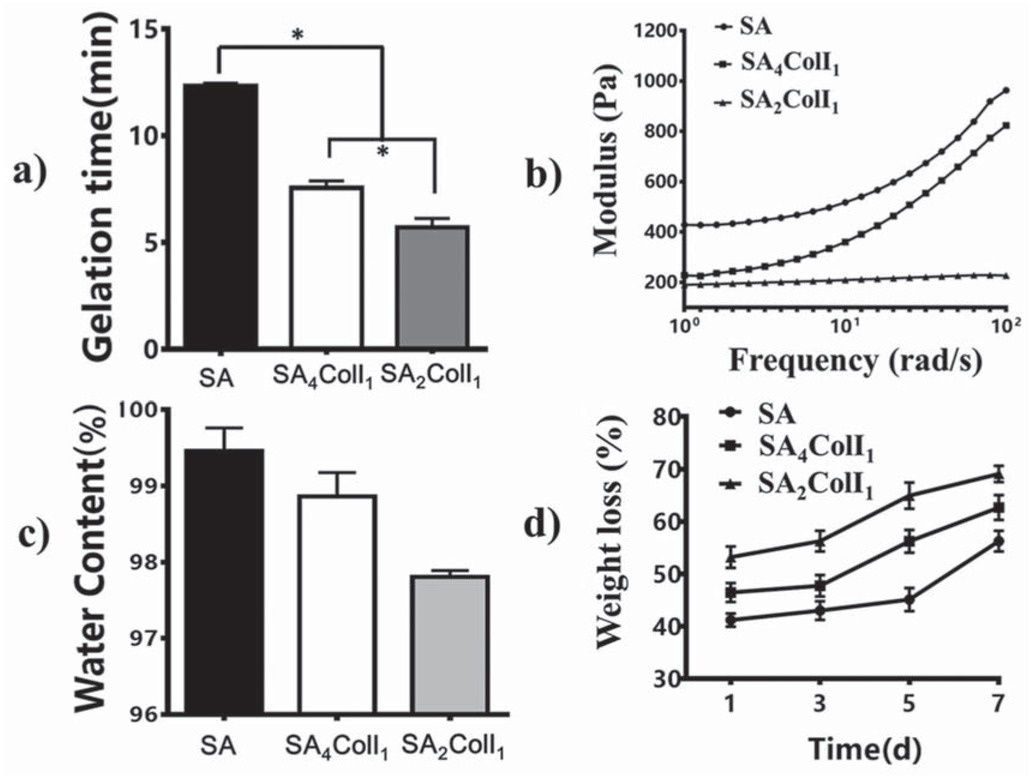

Characterization of ColI/SA hydrogel: The SA4ColI1, SA2ColI1 and SA hydrogels were photographed by a camera equipment to observe the whole object directly, and their morphology was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI quanta200, Netherlands) after freezing at -80°C, fully dried and gold spraying. The crystalline structure of each hydrogel was detected by an X-ray diffraction (XRD) characterization (4). The water contents, degradation performance, gelation time and rheological behavior of the hydrogels were also calculated as the previous work reported (8).

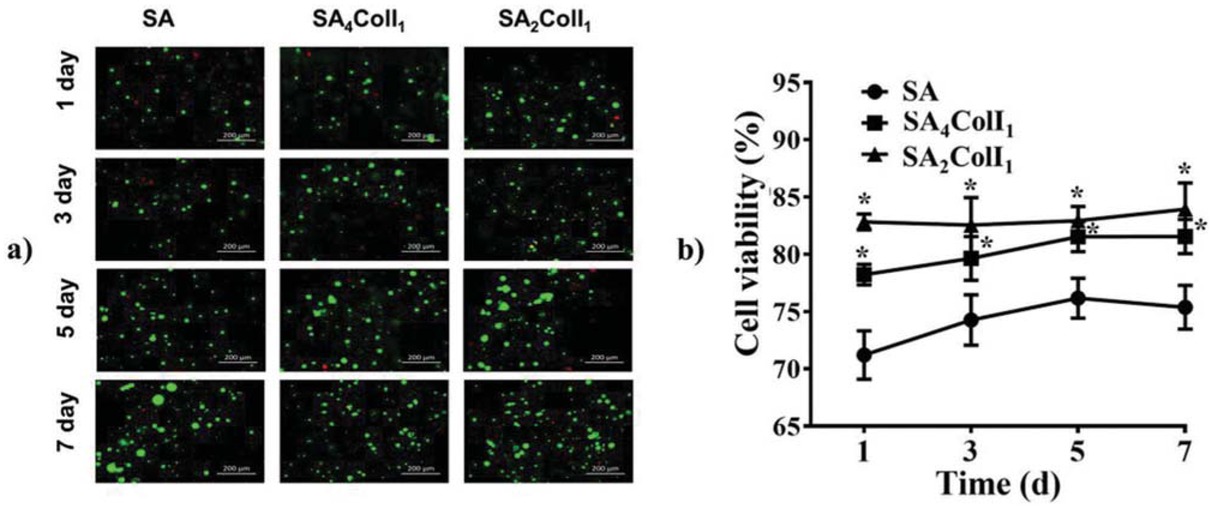

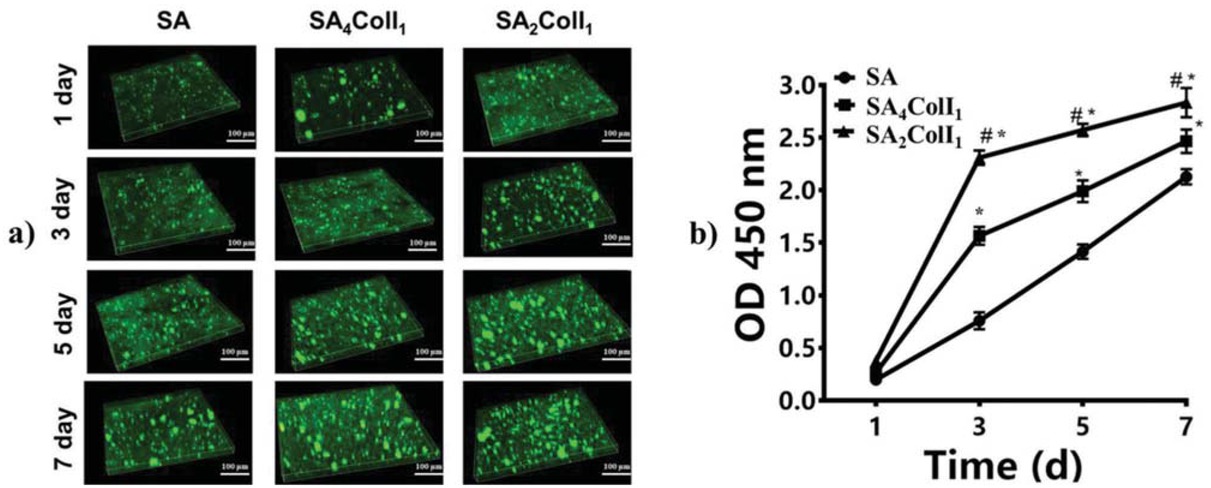

MSCs culture in the ColI/SA hydrogel: Mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (C57-170221I31) were purchased from Sayeye Biotech, China; the 3rd passage of MSCs was used to investigate the ColI/SA hydrogels’ function on creating better MSCs growth microenvironment, including the MSCs distribution, density, proliferation and viability in the hydrogels (8,11,12).

3 Results and discussion

Figure 1a showed that all the hydrogels were molded into a cylindrical shape with the diameters of 15.6 mm after filled into the single hole of the 24-culture-plate and gelation. The SEM displayed their porous structures and the clusters alternately linked in a continuous network (Figure 1b) Notably, the SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels exhibited different pore diameters: The SA showed its pore diameters ranged from 300 μm to 1000 μm, while the SA4ColI1 presented its diameters from 200 μm to 500 μm, and the SA2ColI1 possessed the values from about 50 μm to 100 μm. The MSCs usually maintain their sizes in dozens of microns, thus SA2ColI1 may make more contribution for the MSCs loading and protection (13).

The XRD spectrum of SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels was presented in Figure 2. In case of SA hydrogel, a broad peak around 2θ = 21° (characteristic amorphous peak) was observed which may be due to semi-crystalline structure of natural polysaccharide (SA). The small sharppeaks at diffraction angle (2θ) of 29° was observed when the ColI was introduced to the hydrogels to be cross-linked as the SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 samples. The more ColI added, the stronger the sharper peaks presented, but the weaker the broad peak at 2θ = 21° became. The XRD results further demonstrated successful preparation of the SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels.

(a) The photographs and (b) microstructure of the SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels.

XRD spectra of the SA, SA 4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels.

Figure 3a showed that the gelation time of each hydrogel exceeded 5 min, and this time point is the requirements of the injectable implants for experimental and clinical application. The shorter gelation time surely provides better protection for the loaded cells and markedly reduced the cell loss in vivo. Thus, the gelation time result indicated that the SA2ColI1 may reduce the MSCs loss and provide better protection compared with SA4ColI1 and SA. The rheological behavior of the hydrogels was investigated via detecting their modulus of elasticity, and the modulus values of all the hydrogels ranged from 200 Pa to 1000 Pa (Figure 3b) which were similar to the human body’s tissue modulus values, and this will contribute to the interaction of the implants and the focal tissue and improve the recovery of the damaged organs (14). Wherein, the SA2ColI1 presented a stable modulus values curve compared to SA4ColI1 and SA, which obviously made better matching degree for the tissues and may be more beneficial to the tissue repair and regeneration. All the hydrogels presented extremely high ratios of water content (higher than 95%, Figure 3c) creating a moist environment for cell loading and interaction, and the humid tissue scaffold also contributed to the factorsexchange and cell migration between the implants and the focal tissue. Figure 3d displayed the degradation performance of the SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels: Although all the hydrogels showed rapid degradation speeds within 7 days, there is still at least 30% mass left to protect the loaded cells and the degradation speeds could be controlled by regulating the ColI ratio according to the different tissues’ requirement.

(a) Gelation time, (b) modulus, (c) water content, and weight loss of each hydrogel (mean ± SD, n=3, *p < 0.05).

Figure 4 showed the MSCs viability in each hydrogel: Obviously, the SA2ColI1 hydrogel exhibited higher viability ratio compared with SA and SA4ColI1 hydrogels, and this embodied in more green dots and less red dots in Figure 4a More ColI and smaller pore diameters of SA2ColI1 hydrogel may be main contribution for the higher MSCs viability (8). In addition, the MSCs loading in the SA hydrogel presented a sharply declined viability ratio after the 5th days, and this period is the most crucial for the function recovery of the injury tissues, while the MSCs loading in the SA2ColI1 and SA4ColI1 hydrogels still maintained in the higher viability ratios within the first 7 days (> 80%) (Figure 4b) and this result also indirectly proved that the hydrogels degradation did not reduce the MSCs viability.

(a) Live/dead staining and (b) viability of MSCs loaded in each hydrogel (*p<0.05 compared with SA, mean ± SD, n=3).

The CLSM was applied in a Z axis direction mode to investigate the MSCs proliferation and distribution in the SA, SA4ColI1 and SA2ColI1 hydrogels (Figure 5a) and the MSCs quantitative characterization were

(a) CLSM images and (b) proliferation detection of MSCs distributed in each hydrogel (*p<0.001 compared with SA, #p<0.001 compared with SA4ColI1, mean ± SD, n=3).

also performed by a CCK-8 method (Figure 5b) From the CLSM images, MSCs homogeneously distributed in all the hydrogels, and the SA2ColI1 hydrogel showed higher MSCs density (more green dots) than the SA and SA4ColI1 hydrogels. The CCK-8 results also demonstrated that higher OD values (450 nm) appeared in the SA2ColI1 group at the 3rd day, 5th day, and 7th day although all the three curves displayed the upward trend, suggesting better ability on improving MSCs proliferation and activity.

4 Conclusions

In this contribution, we prepared an injectable hydrogel scaffold with Type I collagen (ColI) and sodium alginate (SA). The physical and chemical properties detection results indicated that the SA2ColI1 hydrogel had a shorter gelation time, which will provide better protection for the MSCs, and the SA2ColI1 hydrogel also showed more stable rheological behavior compared with the control, suggesting better contribution to the organization matching. All the hydrogels presented good water content and degradation performance. The living/dead staining results suggested that the MSCs in SA2ColI1 hydrogel possessed higher viability, and the CLSM images exhibited that the SA2ColI1 hydrogel displayed higher MSCs number and better proliferation compared to the controls. All these results suggest the feasibility of the SA2ColI1 hydrogel as a MSCs tissue engineering scaffold for the application on tissue repair and regeneration for its excellent ability to create better MSCs growth microenvironment.

Acknowledgements

We gratitude the financial supports from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M582206), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81471306), Key scientific research projects of higher education institutions in Henan province (16A430030), Key Project and Special Foundation of Research, Development and Promotion in Henan province (No. 182102310076), and the Joint Fund for Fostering Talents of NCIR-MMT & HNKL-MMT (No.MMT2017-01 and No.MMT2017-04).

Conflict of interest

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

1 Palumbo A., Anderson K., Medical Progress Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med, 2011, 64, 1046-1060.10.1056/NEJMra1011442Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Anonymous, Fetal stem cell transplants. Science, 2017, 357, 433-433.Suche in Google Scholar

3 Li J.A., Zhang K., Huang N., Engineering Cardiovascular Implant Surfaces to Create a Vascular Endothelial Growth Microenvironment. Biotechnol J, 2017, 12, 1600401.10.1002/biot.201600401Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Li K.K., Jiao T.F., Xing R.R., Zou G.D., Zhou J.X., Zhang L.X., et al., Fabrication of tunable hierarchical MXene@AuNPs nanocomposites constructed by self-reduction reactions with enhanced catalytic performances. Sci China Mater, 2018, 61 (5), 728-736.10.1007/s40843-017-9196-8Suche in Google Scholar

5 Liu Y.M., Ma K., Jiao T.F., Xing R.R., Shen G.Z., Yan X.H., Water-Insoluble Photosensitizer Nanocolloids Stabilized by Supramolecular Interfacial Assembly towards Photodynamic Therapy. Sci Rep-UK, 2017, 7, 42978.10.1038/srep42978Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Li J.A., Zhang K., Chen H.Q., Liu T., Yang P., Zhao Y.C., et al., A novel coating of type IV collagen and hyaluronic acid on stent material-titanium for promoting smooth muscle cells contractile phenotype. Mater Sci Eng C, 2014, 38, 235-243.10.1016/j.msec.2014.02.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Zarrintaj P., Manouchehri S., Ahmadi Z., Saeb M.R., Urbanska A.M., Kaplan D.L., et al., Agarose-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. Carbohyd Polym, 2018, 197, 66-84.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.060Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8 Zhang K., Shi Z.Q., Zhou J.K., Xing Q., Ma S.S., et al., Potential application of an injectable hydrogel screfold loaded with mesenchymal stem cells for treating traumatic brain injury. J Mater Chem B, 2018, 6, 2982-2992.10.1039/C7TB03213GSuche in Google Scholar

9 Stender C.J., Rust E., Martin P.T., Neumann E.E., Brown R.J., Lujan T.J., Modeling the effect of collagen fibril alignment on ligament mechanical behavior. Biomech Model Mechan, 2018, 17, 543-557.10.1007/s10237-017-0977-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Xing R.T., Liu K., Jiao T.F., Zhang N., Ma K., Zhang R.Y., et al., An Injectable Self-Assembling Collagen-Gold Hybrid Hydrogel for Combinatorial Antitumor Photothermal/Photodynamic Therapy. Adv Mater, 2016, 28 (19), 3669-3676.10.1002/adma.201600284Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Chen L., Li J.A., Chang J.W., Jin S.B., Wu D., Yan H.H., et al., Mg-Zn-Y-Nd coated with citric acid and dopamine by layer-by-layer self-assembly to improve surface biocompatibility. Sci China Technol Sc, 2018, 61 (8), 1228-1237.10.1007/s11431-017-9190-2Suche in Google Scholar

12 Zhang K., Wang X.F., Guan F.X., Li Q., Li J.A., Immobilization of Ophiopogonin D on stainless steel surfaces for improving surface endothelialization. RSC Adv, 2016, 6, 113893-113898.10.1039/C6RA17584HSuche in Google Scholar

13 Song J.W., Xing R.R., Jiao T.F., Peng Q.M., Yuan C.Q., Mohwald H., et al., Crystalline Dipeptide Nanobelts Based on Solid-Solid Phase Transformation Self-Assembly and Their Polarization Imaging of Cells. ACS Appl Mater Inter, 10, 2368-2376.10.1021/acsami.7b17933Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Lv H.W., Li L.S., Zhang Y., Chen Z.S., Sun M.Y., Xu T.K., et al., Union is strength: matrix elasticity and microenvironmental factors codetermine stem cell differentiation fate. Cell Tissue Res, 2015, 361, 657-668.10.1007/s00441-015-2190-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Zhou et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die