Abstract

A new conductive composite composed of nanoscale carbon black (CB) and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) was prepared by a simple in-situ polymerization. The morphology of the composite was characterized by scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. The structure and thermal stability were examined by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and thermal gravimetric analysis, respectively. The results indicated that the addition of CB improved the agglomerated state of PEDOT. On the one hand, CB effectively hindered the agglomeration of PEDOT during the polymerization. Thus, the obtained CB-PEDOT composite dispersed well in solution, which can facilitate the reprocessing of CB-PEDOT. On the other hand, CB covered most of the surface of PEDOT, which enhanced the electrical conductivity of CB-PEDOT. Furthermore, the interfacial interaction between CB and PEDOT improved the thermal stability of CB-PEDOT. The findings of this research suggest that CB can replace polyelectrolyte poly(styrenesulfonic acid) (PSS) to achieve reprocessable materials for certain applications.

1 Introduction

Printing is an innovative and advantageous technique to manufacture electronics compared to conventional photolithographic, electroplating and etching methods, due to its low cost, high efficiency, flexible operation and environment friendly nature (1,2). Various types of electronics such as thin film transistors, solar cells, RFIDs, antennas, sensors and displays can also be printed by using conductive ink (3). Among the commercially available conductive inks, gold, silver, copper, carbon and polymer-based inks are promising for printing circuits, electrodes, electroplated substrates and keyboard contacts with high electrical conductivity (4,5). However, these conductive inks are usually expensive, like gold and silver-based inks, or easily oxidized, like copper-based conductive inks (6). Particularly, when the printed electronics are used in food packaging and medicine packaging, the use of heavy metals such as gold, silver, and copper is restricted for safety reasons. Therefore, conductive polymers, without heavy metal pollution, are promising with unique physicochemical properties. Among the conductive polymers, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) and its derivatives exhibit excellent stability, and desirable chemical and physical properties (7, 8, 9) compared to polypyrrole and polyaniline (10). Recently, PEDOT and its derivatives have been widely used in light-emitting diodes, gas sensors, antistatic materials, passive components, display devices, electromagnetic shielding and other electronics due to their high conductivity, environmentally-friendly nature, excellent thermal stability, low band gap and high transparency (11, 12, 13).

It is worth noting that pure PEDOT cannot dissolve in any solution and suffers from serious aggregation during conventional polymerization reaction in the absence of a template (carrier) (14,15). As a result, the obtained PEDOT cannot be reprocessed and cannot be used in conductive inks. In order to improve the solubility and dispersibility, a water-soluble polyelectrolyte, such as poly(styrenesulfonic acid) (PSS), is generally introduced as a charge balancing dopant to form a hybrid PEDOT:PSS (16), which can be dissolved in water. The reason that PEDOT: PSS can be dissolved is due to the sulfonate groups (SO3–) and sulfonic acid groups (SO3– H+) in PSS. It is the sulfonic acid groups (SO3– H+) that induce the formation of aqueous colloidal dispersion (17). For this reason, PEDOT: PSS is widely used in organic photoelectric devices (18, 19, 20, 21). Despite its relatively high transparency in the doped state and good mechanical flexibility, the introduction of non-conductive PSS decreases the conductivity of PEDOT, which is detrimental to its applications in printed electronics. For improving the conductivity of PEDOT:PSS, one alternative strategy is to incorporate PEDOT:PSS into conducting carbon-based materials (22, 23, 24, 25). In particular, carbon-based materials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes have been used in the design of PEDOT:PSS hybrid materials through surface modification (26) and stabilization techniques (27) in recent years. Several reports have demonstrated the successful incorporation of graphene into PEDOT:PSS to produce novel nanocomposite materials (28, 29, 30, 31). For example, Zhu Xueqiao et al. (32) performed in-situ polymerization of EDOT in aqueous graphene dispersion to form a PEDOT:PSS-graphene nanocomposite. Using a high concentration graphene (G) dispersion assisted by sulfonated carbon nanotube (SCNT), Ji Ting et al. (33) successfully obtained a conductive G:SCNT material with an interconnected network. Coated by this G:SCNT, PEDOT: PSS displayed outstanding film-forming property and excellent conductivity (2645 S/cm).

Carbon black (CB) is an important, industry relevant product (34), which is ubiquitous in countless applications such as reinforcing filler for tires and other rubber products, pigment for printing inks, coatings, conductive inks, plastics, etc. According to the specific applications, different grades, qualities and grain sizes of CB are available (35,36). Recently, nanoscale carbon black has attracted considerable research interest due to its large surface area and fluffy morphology (1). It can be used in many technological fields such as nanoelectronics. Due to its high conductivity and high specific surface area, nanoscale CB was selected in this study to improve the electrical conductivity and aggregation structure of PEDOT, without the addition of PSS. Firstly, CB nanoparticles were dispersed into EDOT and then in-situ polymerized into a composite material, CB-PEDOT. The composite material obtained in this way was expected to improve the dispersibility and electrical conductivity of PEDOT. Finally, the structure and morphology of CB-PEDOT were investigated by using scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR). Furthermore, its thermal stability and electrical conductivity were evaluated by a thermal gravimetric analyzer and a four-point probe, respectively.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) of 99.9% purity was obtained from Shanghai Herochem Co., Ltd. Carbon Black (CB) with average particle size of 18 nm (diameter) was obtained from Hangzhou Juy New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. The oil absorption of di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) is about 170 mL/100 g and its pH is 7.5. Ammonium persulfate (APS) of analytical purity was obtained from Shanghai Vita Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Iron trichloride (FeCl3) was purchased from Guangdong Weng Jiang Reagent Co., Ltd, and ethanol was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory.

2.2 Nanocomposite preparation

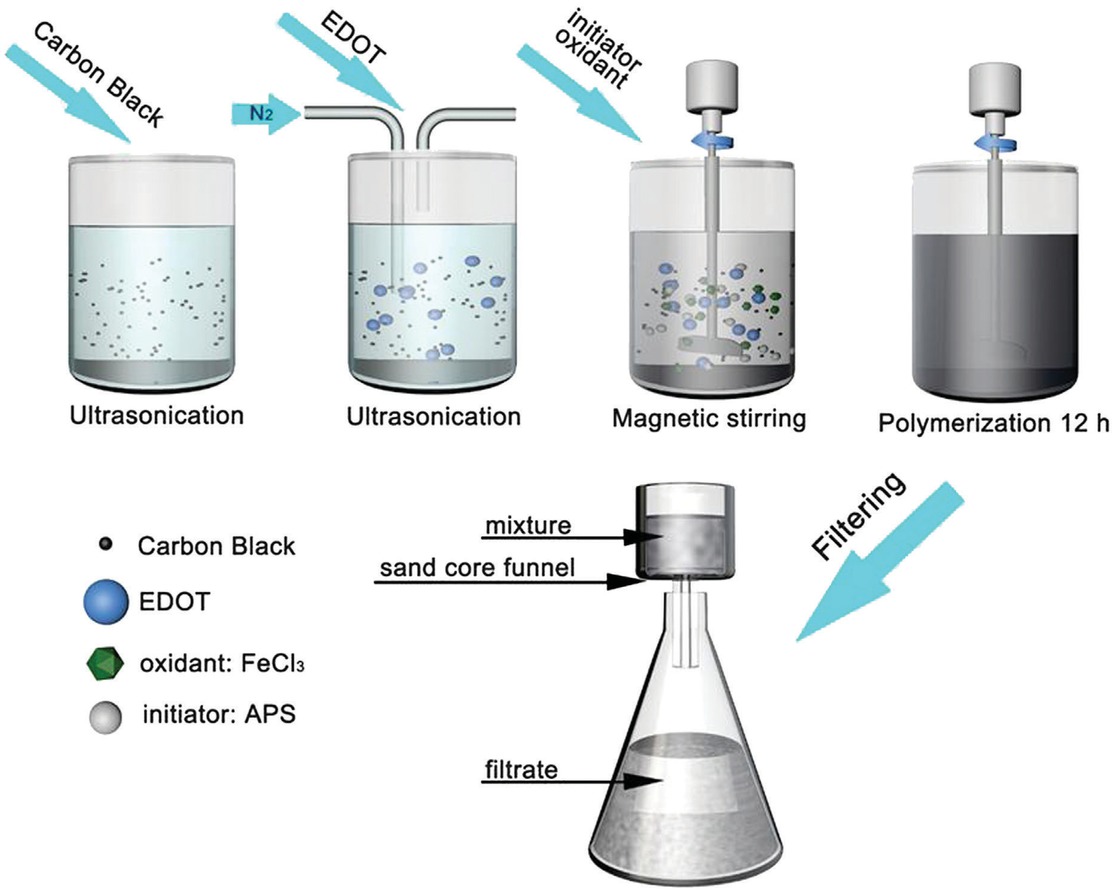

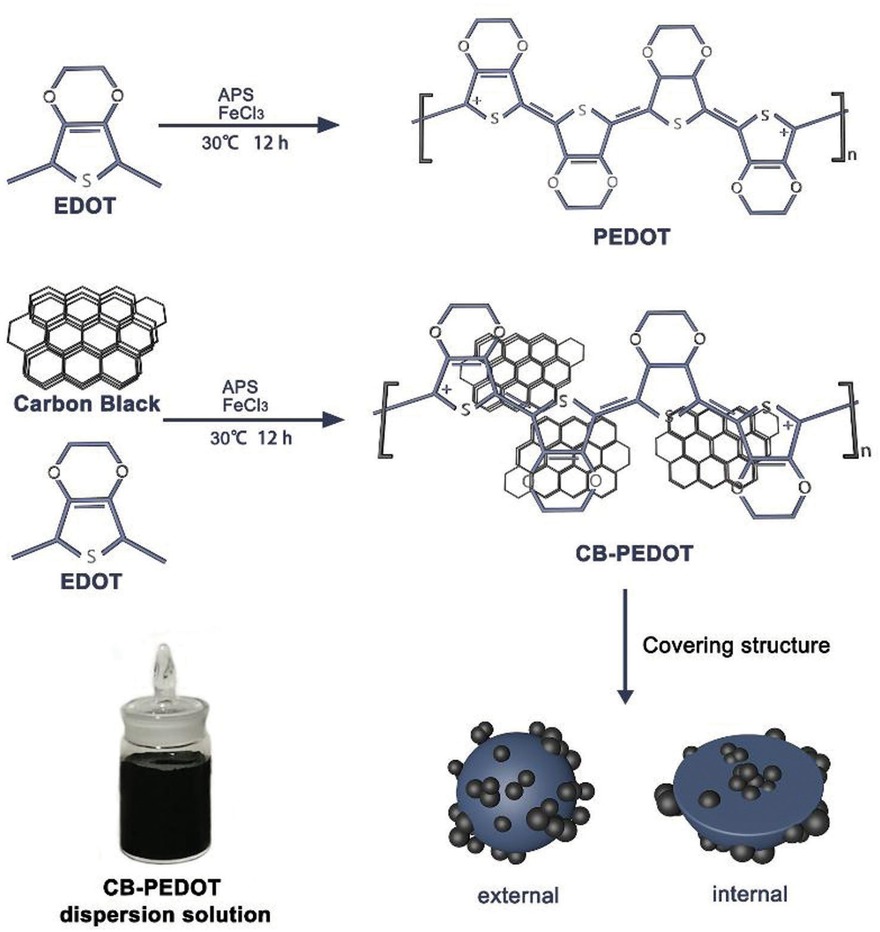

The preparation process of CB-PEDOT composite is shown in Figure 1. CB was dispersed in a mixed solution of DI-water and ethanol (20 vol% of DI-water), and then the mixture was sonicated for 20 min to form a suspension. Subsequently, the EDOT monomer was added into the suspension and sonicated for 20 min to achieve a uniform dispersed system. The dispersed system was bubbled with nitrogen gas for 10 min to remove dissolved oxygen to avoid over-oxidation of EDOT monomer. Specific amounts of aqueous APS solution and aqueous ferric chloride solution were then added dropwise into the aforementioned dispersed system as in-situ polymerization initiators. Subsequently, the dispersed system was magnetically stirred in a water bath at 30°C for 12 h under closed conditions. The system changed from milky white to clear at first, and then gradually turned black after 20 min of the polymerization reaction, which indicated the formation of CB-PEDOT. The dispersed system was subjected to suction filtration with water and absolute ethanol several times to remove the excess APS and the unreacted EDOT monomer. The final polymerization product was dried in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 12 h.

Experimental procedure for preparation of CB-PEDOT composite.

For comparison, pure PEDOT was also synthesized using the same method. The structures of pure PEDOT and CB-PEDOT were characterized by FTIR and TGA.

2.3 Composite characterization

The morphologies of PEDOT and CB-PEDOT composite were observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Quanta-200, FEI, USA). The difference in the morphology of pure PEDOT and CB-PEDOT composite was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEM-2100F, JEOL, Japan). Using the potassium bromide (KBr) disc technique, the FTIR spectra of the samples with the same amount were obtained using FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet, 380, Thermo, USA). Spectra were obtained between 4000 and 400 cm-1. Specific spectral peaks were identified and assigned to functional groups. The thermal properties were examined by TGA (Q50, TA Instruments, USA), where the samples were heated from room temperature to 600°C in N2. The electrical conductivity was measured by using four-probe tester (RTS-8, Probes Tech, China).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology of CB-PEDOT

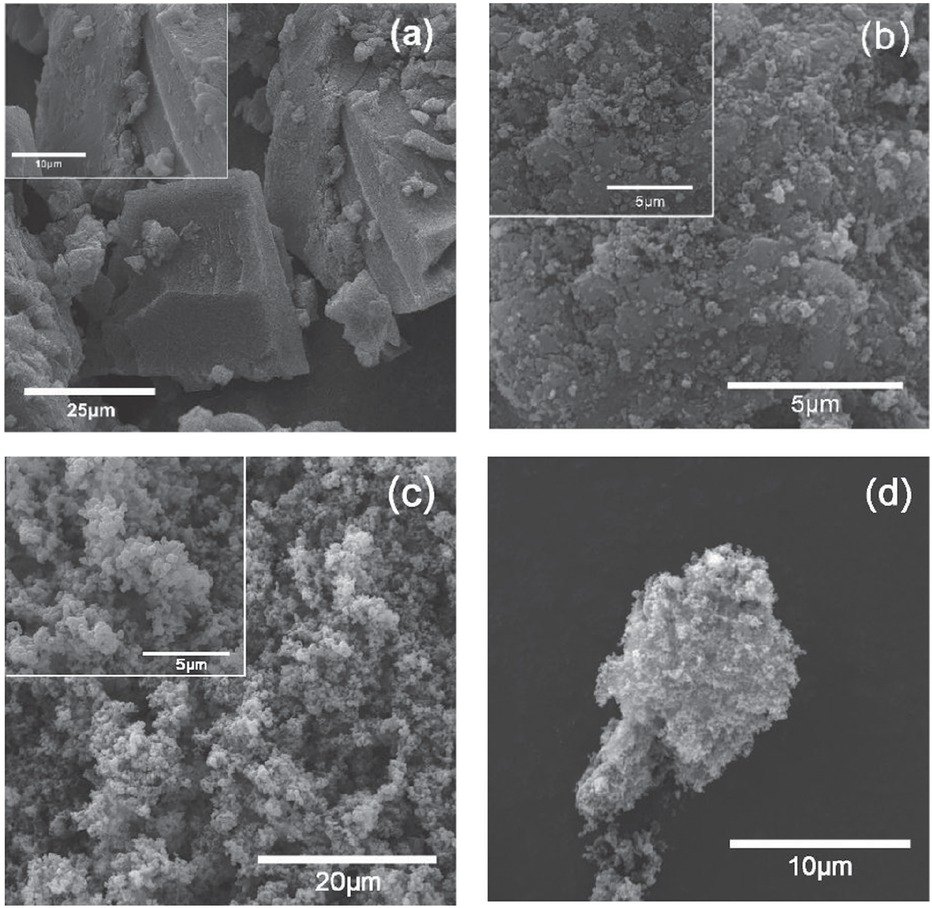

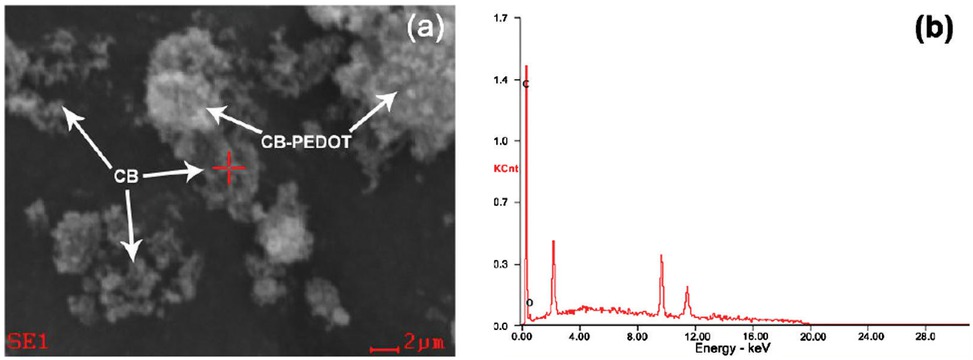

The morphology of CB-PEDOT was observed via scanning electron microscopy (Figure 2). As can be seen from Figure 2a, pure PEDOT displayed an aggregate morphology. The aggregated PEDOT cannot be easily reprocessed, which restricts its application in many fields. When the nanoscale CB was added into the EDOT monomer, a porous and spongy structure was achieved. Figure 2b-d shows the morphology of the composite CB-PEDOT. It can be clearly seen that the composite structure had a coarse morphology with many pores. Based on the difference between the morphologies in Figure 2a and Figure 2b-d, it can be concluded that nanoscale CB hindered the agglomeration of PEDOT through polymerization. As a result, the processability of PEDOT was improved significantly. This deduction was confirmed by the EDS analysis. Figure 3 and Table 1 are the EDS analysis results of CB-PEDOT. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, element C was 93.84% in weight, which came from carbon black nanoparticles. This indicated that most of the carbon black nanoparticles were adhered to the surface of PEDOT. Obviously, the addition of carbon black nanoparticles increased the

SEM morphologies of (a) pure PEDOT; and (b, c, d) CB-PEDOT.

EDS analysis results of the surface of CB-PEDOT composite (CB:PEDOT=2:1).

Element proportion of the surface of CB-PEDOT composite.

| Element | wt% | at% |

|---|---|---|

| CK | 93.84 | 95.30 |

| OK | 06.16 | 04.70 |

| Matrix | Correction | ZAF |

spaces between PEDOT molecules. Consequently, the agglomeration of PEDOT molecules decreased and the processability was improved. At the same time, the porous and spongy structure increased the specific surface area, which could be helpful to enhance the energy storage density of the material.

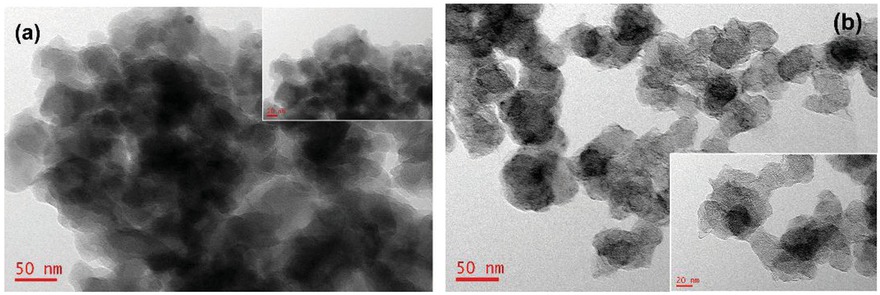

The above results were also confirmed by the results of transmission electron microscopy (Figure 4). Figure 4a shows that pure PEDOT was easily agglomerated through polymerization. After doping with nanoscale carbon black, the molecular chains of PEDOT were extended more freely (Figure 4b). Consequently, the new CB-PEDOT composite was easily dispersed in solutions. It can be coated on and adhere to the surface of other suitable materials.

TEM morphologies of (a) pure PEDOT; and (b) CB-PEDOT.

3.2 Structural analysis of CB-PEDOT

The chemical structures of carbon black nanoparticles, PEDOT and CB-PEDOT were examined by FTIR spectroscopy (Figure 5). In the FTIR spectrum of CB, there was a strong absorption peak near 3440 cm−1 which corresponded to the stretching vibration of -OH. The absorption peak at 1629 cm−1 was assigned to the bending vibration of C-OH, and the peak at 1110 cm−1 was attributed to the vibrational absorption of C-O-C. These characteristic peaks indicated that carbon black contained a large number of oxygen-containing groups, which is consistent with previous reports (37).

FTIR spectra of pure PEDOT, CB and CB-PEDOT (over the range of 400 - 4000 cm-1).

In the FTIR spectrum of CB-PEDOT, the absorption bands at 1484 and 1396 cm−1 were assigned to C=C and C-C stretching vibrations of the thiophene ring, respectively (14). The characteristic peaks in the spectrum at 984 cm−1, 844 cm−1 and 693 cm−1 corresponded to C-S stretching mode (38). The absorption peak at 1215 cm−1 was attributed to the C-O-C stretching vibration. The absorption peak at 2850-2980 cm−1 was due to the stretching vibration of -CH2 in the thiophene heterocycle. These peaks shifted toward higher wavenumber (so-called blue shift) by about 4~6 cm−1 compared to the bands in pure PEDOT. The shift indicated that a certain interfacial interaction existed between the molecular chains of PEDOT and CB. This interaction stabilized the composite and the energy required for vibration became higher. Thus, the groups tended to be more stable, which caused blue shift of the absorption bands (39,40). However, it is difficult to accurately examine the interfacial interaction between the outer CB layer and the inner PEDOT in the composites by FTIR analysis alone (41,42).

According to the above analysis, EDOT underwent oxidative polymerization in water/ ethanol to form oligomeric free radicals under the action of initiator (APS) and oxidant (FeCl3) (Figure 6). It is believed that during the PEDOT polymerization process, a small amount of carbon black nanoparticles were encapsulated by PEDOT. However, the CB nanoparticles covered most of the surface of PEDOT, which effectively hindered the agglomeration of PEDOT during polymerization. Thereby, the dispersibility of PEDOT in solution was increased. Figure 6 shows that the prepared CB-PEDOT composite can be stably dispersed in a water/ alcohol solution.

Schematic of polymerization and structure of the CB-PEDOT composite.

3.3 Thermal stability of CB-PEDOT

The thermal stability of a hybrid is critical for its potential applications. Therefore, the thermal stability of CB-PEDOT was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The thermal stability and the mass loss

of CB-PEDOT nanocomposite were examined by TGA at a heating rate of 5°C/min from room temperature to 600°C under a nitrogen atmosphere. Figure 7 shows the TGA results of pure PEDOT and CB-PEDOT. As can be seen from Figure 7, there was a slight mass loss before 100°C which could be ascribed to the adsorbed moisture in the material. Due to the decomposition of oxygen functional groups on the PEDOT surface, the second mass loss was observed at 200 to 400°C. This mass loss was followed by a slight continuous mass loss up to ∼600°C, which can be attributed to the decomposition of residual polymer components. With the increase in proportion of carbon black, the mass loss decreased. The TGA curve of pure PEDOT showed a significant drop at 200°C due to the burning and elimination of organic polymer components (43). However, when the ratio of carbon black to PEDOT was 3:5, the TGA curve of the composite material showed a significant decrease from about 230°C. This indicated that the thermal stability of composite material increased due to the addition of carbon black.

TGA analysis of pure PEDOT and CB-PEDOT (a) thermal weight loss ratio, (b) derivative change rate.

Based on the TGA results, it is evident that the CB-PEDOT nanocomposite was successfully synthesized, and the thermal stability of CB-PEDOT was improved compared to pure PEDOT.

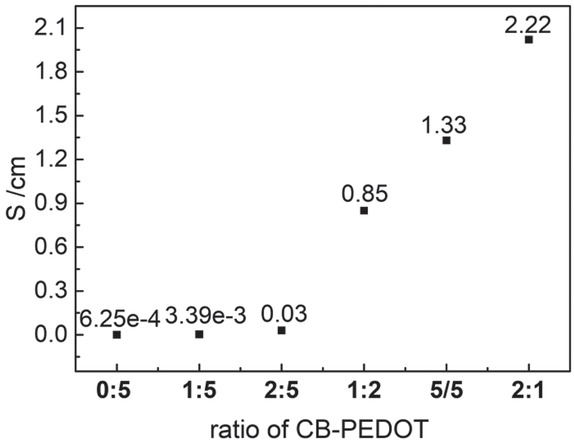

3.4 Electrical properties of CB-PEDOT

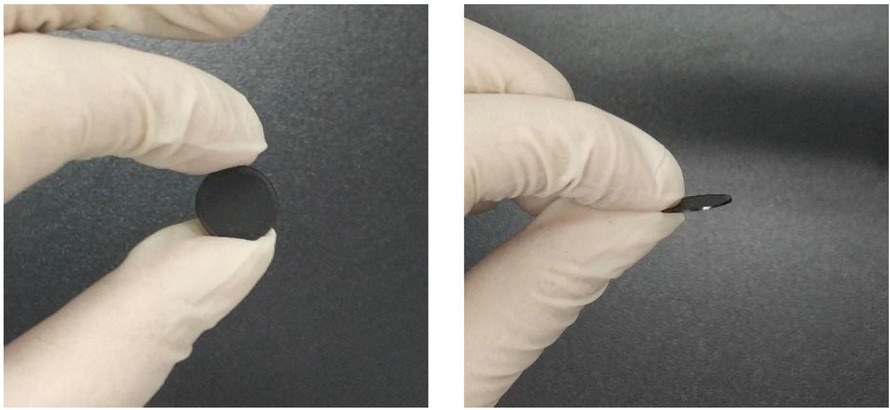

The CB-PEDOT composite was tableted to obtain a disc with a diameter of about 10 mm and a thickness of 500±100 μm (Figure 8) (44). The electrical conductivity of CB-PEDOT was tested using a Four-probe tester. As can be seen from Figure 9, conductive carbon black exerted a significant influence on the electrical conductivity of the composite. When the ratio of carbon black to PEDOT was below 2:5, the electrical conductivity was no more than 0.03 S/cm. With further increase in the ratio, the electrical conductivity increased in a linear manner. When the ratio was 5:5, the electrical conductivity was as high as 1.33 S/cm.

Discs having a diameter of about 10 mm and a thickness of 500±100 μm using the method of infrared compression.

The electrical conductivity of CB-PEDOT at different ratios.

The electrical conductivity of the new CB-PEDOT was significantly higher than that of PEDOT (Laboratory Preparation, 6.25e-4 S/cm). In addition, according to the conductivity of the commercialized PEDOT:PSS product reported in literature (Clevios TM P AI 4083, 10-5∼10-6 S/m) (45), the effect of carbon black on conductivity can be further confirmed. When more carbon black was added, the electrical conductivity was higher. However, when the ratio between carbon black and PEDOT was higher than 5:5, there was less bonding between carbon black and PEDOT. It can be seen in Figure 3a, superfluous CB would exist at a form of isolated particles which is detrimental to the stability of the composite CB-PEDOT. It is also unfavorable for forming a coating structure. According to the EDS analysis of Figure 3, most of the carbon black and PEDOT were adhered to the surface of PEDOT. At the same time, some small carbon black particles are isolated in composites. It is believed that excess addition of CB may hinder the polymerization of EDOT, which would be detrimental to the application of PEDOT. However, Carbon black can also form an effective thermal barrier around the center PEDOT, which improves the stability of the composites to a certain extent.

4 Conclusion

In summary, a new CB-PEDOT composite was successfully synthesized via an in-situ oxidative polymerization process. The addition of CB improved the electrical conductivity and restricted the aggregation behavior of PEDOT without adding PSS. As a result, the processability and dispersibility of PEDOT were improved significantly. Furthermore, the porous and spongy structure of the composite increased the specific surface area, which could help enhance the energy storage density. The results revealed that the CB-PEDOT prepared by in-situ polymerization possessed higher electrical conductivity and thermal stability compared to pure PEDOT. It should be noted that the proportion of CB and PEDOT had an important effect on the electrical conductivity of the composite. When the ratio was 5:5, the electrical conductivity was as high as 1.33 S/cm. The promising CB-PEDOT composite prepared by this method could be potentially applied for the preparation of polymer-based conductive inks.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2015JJ5010), the National Science Foundation of China (No. 61170101), the Packaging Advertising Research Base Project of China (17JDXMA01, 17JDXMB08), Green Packaging and Security Special Research Fund of China Packaging Federation (2016ZBLY06) and the National College Student Innovation Training Program (201711535001) for their financial support of this work.

References

1 Cinti S., Neagu D., Carbone M., Cacciotti I., Moscone D., Arduini F., Novel carbon black-cobalt phthalocyanine nanocomposite as sensing platform to detect organophosphorus pollutants at screen-printed electrode. Electrochim Acta, 2016, 188, 574-581.10.1016/j.electacta.2015.11.069Suche in Google Scholar

2 Santhiago M., Côrrea C.C., Bernardes J.S., Pereira M.P., Ljm O., Strauss M., et al., Flexible and Foldable Fully-Printed Carbon Black Conductive Nanostructures on Paper for High-Performance Electronic, Electrochemical, and Wearable Devices. ACS Appl Mater Inter, 2017, 9.10.1021/acsami.7b06598Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Lee M.Y., Lee M.W., Park J.E., Park J.S., Song C.K., A printing technology combining screen-printing with a wet-etching process for the gate electrodes of organic thin film transistors on a plastic substrate. Microelectron Eng, 2010, 87, 1922-1926.10.1016/j.mee.2009.11.073Suche in Google Scholar

4 Son Y., Printed Circuit Patterns of Conducting Polymer. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst, 2007, 472, 113-122.10.1080/15421400701545254Suche in Google Scholar

5 Sjöberg P., Määttänen A., Vanamo U., Novell M., Ihalainen P., Andrade F.J., et al., Paper-based potentiometric ion sensors constructed on ink-jet printed gold electrodes. Sensor Actuat-B Chem, 2016, 224, 325-332.10.1016/j.snb.2015.10.051Suche in Google Scholar

6 Wei H.E., Yang Y., Wang S., Bo H.E., Ke H.U., Preparation Technology and Application Progress of Conductive Inks. Mat Rev, 2009, 23, 30-33.Suche in Google Scholar

7 Bai X., Hu X., Zhou S., Yan J., Sun C., Chen P., et al., Controlled fabrication of highly conductive three-dimensional flowerlike poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanostructures. J Mat Chem, 2011, 21, 7123-7129.10.1039/c1jm10335kSuche in Google Scholar

8 Gonçalves V.C., Balogh D.T., Optical chemical sensors using polythiophene derivatives as active layer for detection of volatile organic compounds. Sensor Actuat-B Chem, 2012, 162, 307-312.10.1016/j.snb.2011.12.084Suche in Google Scholar

9 Heywang G., Jonas F., Poly(alkylenedioxythiophene)s—new, very stable conducting polymers. Adv Mat, 2010, 4, 116-118.10.1002/adma.19920040213Suche in Google Scholar

10 Kim B.H., Kim M.S., Park K.T., Lee J.K., Park D.H., Joo J., et al., Characteristics and field emission of conducting poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanowires. Appl Phys Lett, 2003, 83, 539-541.10.1063/1.1592004Suche in Google Scholar

11 Lee C.H., Chuang W.Y., Lin S.H., Wu W.J., Lin C.T., A Printable Humidity Sensing Material Based on Conductive Polymer and Nanoparticles Composites, Jpn J Appl Phys, 2013, 52, 492-494.10.7567/JJAP.52.05DA08Suche in Google Scholar

12 Guo X., Jian J., Lin L., Zhu H., Zhu S., O2 plasma-functionalized SWCNTs and PEDOT/PSS composite film assembled by dielectrophoresis for ultrasensitive trimethylamine gas sensor. Analyst, 2013, 138, 5265-5273.10.1039/c3an36690aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

13 Diggikar R., Kulkarni M., Kale G., Kale B., Formation of multifunctional nanocomposites with ultrathin layers of polyaniline (PANI) on silver vanadium oxide (SVO) nanospheres by in situ polymerization. J Mater Chem A, 2013, 1, 3992-4001.10.1039/c3ta01662eSuche in Google Scholar

14 Han Y., Shen M., Wu Y., Zhu J., Ding B., Tong H., et al., Preparation and electrochemical performances of PEDOT/sulfonic acid-functionalized graphene composite hydrogel. Synthetic Met, 2013, 172, 21-27.10.1016/j.synthmet.2013.04.001Suche in Google Scholar

15 Zhou H., Liu G., Liu J., Wang Y., Ai Q., Huang J., et al., Effective Network Formation of PEDOT by in-situ Polymerization Using Novel Organic Template and Nanocomposite Supercapacitor. Electrochim Acta, 2017, 247, 871-879.10.1016/j.electacta.2017.07.078Suche in Google Scholar

16 Dohyuk Y., Jeonghun K., Hyun K.J., Direct synthesis of highly conductive poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(4-styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS)/graphene composites and their applications in energy harvesting systems. Nano Res, 2014, 7, 717-730.10.1007/s12274-014-0433-zSuche in Google Scholar

17 Sun K., Zhang S., Li P., Xia Y., Zhang X., Du D., et al., Review on application of PEDOTs and PEDOT:PSS in energy conversion and storage devices. J Mater Sci-Mater El, 2015, 26, 4438-4462.10.1007/s10854-015-2895-5Suche in Google Scholar

18 Giuri A., Masi S., Colella S., Kovtun A., Dell’Elce S., Treossi E., et al., Cooperative Effect of GO and Glucose on PEDOT:PSS for High VOC and Hysteresis‐Free Solution‐Processed Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv Funct Mater, 2016, 26, 6985-6994.10.1002/adfm.201603023Suche in Google Scholar

19 Zhang Y., Cui W., Zhu Y., Zu F., Liao L., Lee S.T., et al., High efficiency hybrid PEDOT:PSS/nanostructured silicon Schottky junction solar cells by doping-free rear contact. Energ Environ Sci, 2010, 8, 297-302.10.1039/C4EE02282CSuche in Google Scholar

20 Kim N., Kee S., Lee S.H., Lee B.H., Kahng Y.H., Jo Y.R., et al., Highly Conductive PEDOT:PSS Nanofibrils Induced by Solution‐Processed Crystallization. Adv Mat, 2014, 26, 2268-2272.10.1002/adma.201304611Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Zhang Y., Peng Z., Cai C., Liu Z., Lin Y., Zheng W., et al., Colorful semitransparent polymer solar cells employing a bottom periodic one-dimensional photonic crystal and a top conductive PEDOT:PSS layer. J Mater Chem A, 2016, 4.10.1039/C6TA05249ESuche in Google Scholar

22 Fang X., Liu J., Wang J., Zhao H., Ren H., Li Z., Dual signal amplification strategy of Au nanopaticles/ZnO nanorods hybridized reduced graphene nanosheet and multienzyme functionalized Au@ZnO composites for ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of tumor biomarker. Biosens Bioelectron, 2017, 97, 218-225.10.1016/j.bios.2017.05.055Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23 Qian T., Wu S., Shen J., Facilely prepared polypyrrole-reduced graphite oxide core-shell microspheres with high dispersibility for electrochemical detection of dopamine. Chem Commun, 2013, 49, 4610-4612.10.1039/c3cc00276dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

24 Wang H., Yong Z., Wang Y., Ma H., Du B., Qin W., Facile synthesis of cuprous oxide nanowires decorated graphene oxide nanosheets nanocomposites and its application in label-free electrochemical immunosensor. Biosens Bioelectron, 2017, 87, 745-751.10.1016/j.bios.2016.09.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Park J., Lee A., Yim Y., Han E., Electrical and thermal properties of PEDOT:PSS films doped with carbon nanotubes. Synthetic Met, 2011, 161, 523-527.10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.01.006Suche in Google Scholar

26 Chu C.Y., Tsai J.T., Sun C.L., Synthesis of PEDOT-modified graphene composite materials as flexible electrodes for energy storage and conversion applications. Int J Hydrogen Energ, 2012, 37, 13880-13886.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.05.017Suche in Google Scholar

27 Tung T.T., Kim T.Y., Shim J.P., Yang W.S., Kim H., Suh K.S., Poly(ionic liquid)-stabilized graphene sheets and their hybrid with poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Org Electron, 2011, 12, 2215-2224.10.1016/j.orgel.2011.09.012Suche in Google Scholar

28 Karuwan C., Sriprachuabwong C., Wisitsoraat A., Phokharatkul D., Sritongkham P., Tuantranont A., Inkjet-printed graphene-poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene-sulfonate) modified on screen printed carbon electrode for electrochemical sensing of salbutamol. Sensor Actuat B-Chem, 2012, 161, 549-555.10.1016/j.snb.2011.10.074Suche in Google Scholar

29 Khatri I., Imamura T., Uehara A., Ishikawa R., Ueno K., Shirai H., Chemical mist deposition of graphene oxide and PEDOT:PSS films for crystalline Si/organic heterojunction solar cells. Phys Status Solidi, 2012, 9, 2134-2137.10.1002/pssc.201200132Suche in Google Scholar

30 Peng Y., Zhong J., Wang K., Xue B., Cheng Y.B., A printable graphene enhanced composite counter electrode for flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Energy, 2013, 2, 235-240.10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.08.010Suche in Google Scholar

31 Lu L., Zhang O., Xu J., Wen Y., Duan X., Yu H., et al., A facile one-step redox route for the synthesis of graphene/poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanocomposite and their applications in biosensing. Sensor Actuat B-Chem, 2013, 181, 567-574.10.1016/j.snb.2013.02.024Suche in Google Scholar

32 Zhu X., Zhao N., Luo Y., Du J., Influence of graphene oxide with different degrees of oxidation on the conductivity of graphene/ poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(styrenesulfonate) composites. Fuller Nanotub Car N, 2017, 25, 652-660.10.1080/1536383X.2017.1378644Suche in Google Scholar

33 Ji T., Tan L., Bai J., Hu X., Xiao S., Chen Y., Synergistic dispersible graphene: Sulfonated carbon nanotubes integrated with PEDOT for large-scale transparent conductive electrodes. Carbon, 2016, 98, 15-23.10.1016/j.carbon.2015.10.079Suche in Google Scholar

34 Voll M., Kleinschmit P., Carbon, 6. Carbon Black. Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co, KGaA, 2010.10.1002/14356007.n05_n05Suche in Google Scholar

35 Alexander L.E., Sommer E.C., Systematic Analysis of Carbon Black Structures. J Phys Chem, 1956, 60, 1646-1649.10.1021/j150546a011Suche in Google Scholar

36 Donnet J.B., Fifty years of research and progress on carbon black. Carbon, 1994, 32, 1305-1310.10.1016/0008-6223(94)90116-3Suche in Google Scholar

37 Si Y., Samulski E.T., Synthesis of water soluble graphene. Nano Lett, 2008, 8, 1679.10.1021/nl080604hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

38 Han M.G., Foulger S.H., 1-Dimensional structures of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT): a chemical route to tubes, rods, thimbles, and belts. Chem Commun, 2005, 1, 3092-3094.10.1039/b504727gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

39 Song J.Z., He Y., Zhu D., Chen J., Pei C.L., Wang J.A., Polymer/ ZnO Micro-Nano Array Composites for Light-Emitting Layer of Flexible Optoelectronic Devices. Acta Phys-Chim Sin, 2011, 27, 1207-1213.10.3866/PKU.WHXB20110435Suche in Google Scholar

40 Zhang S.P., Layer-aligned Polyethylene Glycol/Functionalized Graphene Composites with Improved Thermal Stability. Acta Chim Sinica, 2012, 70, 1394.10.6023/A1201101Suche in Google Scholar

41 Yang X., Li L., Shang S., Tao X.M., Synthesis and characterization of layer-aligned poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene nanocomposites. Polymer, 2010, 51, 3431-3435.10.1016/j.polymer.2010.05.034Suche in Google Scholar

42 Zhang Z., Chen G., Wang H., Li X., Template‐Directed In Situ Polymerization Preparation of Nanocomposites of PEDOT:PSS‐Coated Multi‐Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Enhanced Thermoelectric Property. Chem-Asian J, 2015, 10, 149.10.1002/asia.201403100Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43 Zhan L., Song Z., Zhang J., Tang J., Zhan H., Zhou Y., et al., PEDOT: Cathode active material with high specific capacity in novel electrolyte system. Electrochim Acta, 2008, 53, 8319-8323.10.1016/j.electacta.2008.06.053Suche in Google Scholar

44 Wang F., Zhang X., Ma Y., Yang W., Synthesis of HNTs@PEDOT Composites via in situ Chemical Oxidative Polymerization and Their Application in Electrode Materials. Appl Surf Sci, 2018, 427.10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.155Suche in Google Scholar

45 Xu Y., Wang Y., Liang J., Huang Y., Ma Y., Wan X., et al., A hybrid material of graphene and poly (3,4-ethyldioxythiophene) with high conductivity, flexibility, and transparency. Nano Res, 2009, 2, 343-348.10.1007/s12274-009-9032-9Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Xie et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die