Abstract

A new type of octa polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (Octa DMS-POSS) has been obtained. The synthesized Octa DMS-POSS is further modified with vinyl acetate in order to obtain a vinyl acetate-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (VAPOSS) with a better potential to absorb CO2. The effect of reaction temperature, reaction time, and solvent type is optimized by testing the product yield. The effect of vinyl acetate molar ratio on the crystalline, thermal stability, and contact angle is measured through the X-ray diffraction, differential scanning calorimeter, and contact angle tests. CO2 adsorption measurements at 273.0 K were carried out in order to evaluate its potential application in CO2 capture. Optimal preparation conditions are the reaction temperature 25 °C, reaction time 12 h, reaction solvent DMF. The highest yield is 80 %. The addition of VAc appears to interfere with the formation of new crystalline structures. As the VAc content increased, the melting temperatures showed an upward trend, and the contact angle first increased and then decreased slightly. The CO2 uptakes VAPOSS3 were found to be 1.46 mmol⋅g−1 (6.42 wt%). As the molar ratio of VAc to POSS increased, the adsorption capacity increased.

1 Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of industrialization, the consumption of fossil fuel energy has increased and the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere has consequently increased [1], 2]. CO2 has been linked to a more aggressive global climate change on the earth, which comprises around 78 % of greenhouse gas production and is primarily emitted as the result of the combustion of fossil fuels, from natural gas sweetening, the production of synthesis gas, and in certain chemical plants [3]. Moreover, as climate change becomes an increasingly environmental, industrial, and political issue, it is desirable to develop technologies capable of economically separating and sequestering large amounts of CO2.

Among the various post-combustion capture strategies-including absorption, membrane separation, cryogenic distillation, and adsorption. Adsorption processes have garnered significant attention due to their lower energy penalties for sorbent regeneration, potential for automation, and reusability of adsorbent materials [4]. A wide range of solid adsorbents has been investigated for CO2 capture, such as zeolites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), activated carbons (ACs), silica-based materials, and porous organic polymers [5]. Each class offers distinct advantages, for instance, zeolites exhibit high selectivity but are sensitive to moisture, while MOFs possess tunable porosity and high surface areas but often face challenges regarding stability and cost. Activated carbons are cost-effective and widely available but may exhibit moderate CO2 capacities and selectivity under post-combustion conditions.

Hybrid organic-inorganic nanomaterials like polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) have emerged as promising building blocks for constructing advanced adsorbents. POSS, nano-sized stable three-dimensional architectures that consist of alternate Si–O bonds to form cage structures with Si atoms as vertices, is one of the silsesquioxane molecules, which is inorganic-organic hybrid cage structures [6], 7]. The structures may generally have 8, 10 or 12 Si atoms and the chemical formula is RnSinO1.5n, where R represents hydrogen or functional or nonfunctional organic group such as alkyl, alkylene, aryl, acrylate, amine, hydroxyl, epoxide, etc. [8], [9], [10].

Due to the types of functional or non-functional organic groups and inorganic (silica) in the structure of the POSS cage, the POSS has been used as a building block for the preparation and construction of many hybrid polymers, such as luminescent hybrid microporous polymers, polybenzoxazine/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanocomposites, mesoporous poly(cyanate ester) featuring a polyhedral silsesquioxane framework, and amine postfunctionalized porous polymers based on POSS [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. The cubic silica cores are completely defined as ‘hard particles’ and include peripheral organic units. The hybrid polymers are suitable for a variety of interesting applications, such as nanofillers [16], dendrimers, and coatings [17], 18]. Furthermore, POSS molecules with different reactivities used for polymer blend or copolymerization can be formed by varying these functional groups attached to Si atoms [19]. Their functional organic groups allow them to interact with polymer chains, which increases their compatibility with the polymer matrix, providing a better distribution of POSS within the polymer. These functional groups are diversified to allow the reactivity of POSS so that they can be used for polymerization [18]. Notably, POSS-based porous polymers have demonstrated potential in gas storage and separation applications due to their high surface areas and the ability to incorporate specific functional groups that interact favorably with CO2 molecules [20]. Mohamed et al. demonstrated the successful synthesis of POSS-TPP and POSS-TPE via Friedel-Crafts polymerization using octavinylsilsesquioxane (OVS) as a building block. Notably, POSS-TPP showed a remarkable CO2 uptake capacity of 1.63 mmol/g at 298 K and 2.88 mmol/g at 273 K, outperforming many previously reported porous polymers [21].

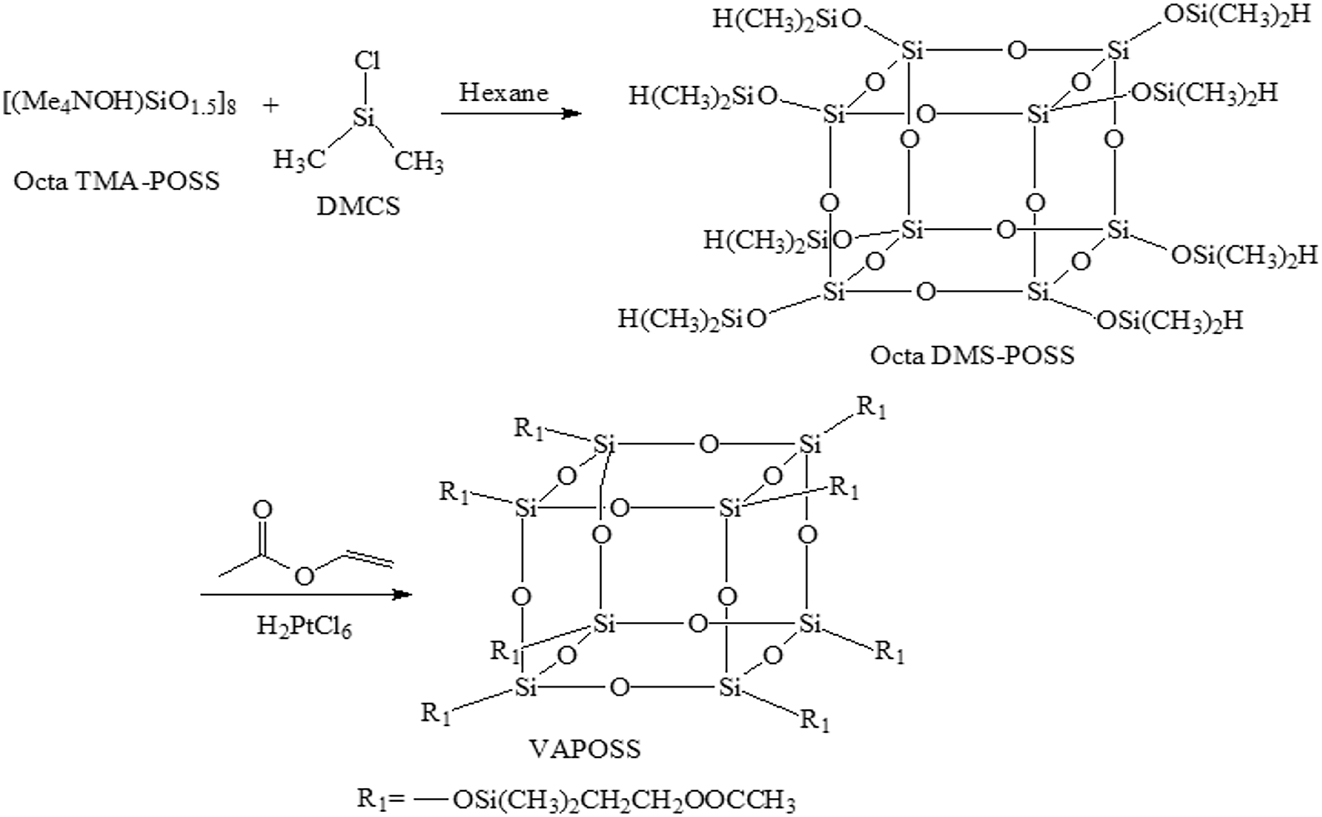

In this current work, the cage-like octa polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (Octa DMS-POSS) was synthesized, and followed by modifying POSS with vinyl acetate as a functional group to form a new type of POSS, vinyl acetate-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (VAPOSS). The effect of preparation conditions is optimized by varying the reaction conditions like reaction temperature, reaction time, and solvent type. The structure of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS is characterized by the attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance. The effect of vinyl acetate molar ratio on the crystalline, thermal stability, and contact angle is measured through the X-ray diffraction, differential scanning calorimeter and contact angle tests.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Dimethylchlorosilane (DMCS) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Octa tetramethylammonium-POSS (Octa TMA-POSS) was supplied by Shanghai Enchem Industry Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Vinyl acetate (VAc) was obtained from Jinan Yucai Chemical Co., Ltd., Shandong, China. Hexane was supplied by Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Ethanol was purchased from Nantong Reform Petro-Chemical Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) was supplied by Guangzhou Zhongye Chemical Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China. Methanol was supplied by Tianli Chemical Regent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Chloroplatinic acid was produced by Hongyan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China.

2.2 Preparation of vinyl acetate modified polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (VAPOSS)

The starting material, Octa TMA-POSS, is a well-known POSS cage with a siloxane core (SiO1.5)8 surrounded by eight tetramethylammonium groups. The subsequent reaction with DMCS replaces these organic cations with -Si(CH3)2H groups, yielding the key intermediate Octa DMS-POSS, which possesses the reactive Si–H bonds necessary for the subsequent functionalization with vinyl acetate.

2.2.1 Preparation of octa dimethylsilane-POSS (Octa DMS-POSS)

Briefly, a 100 ml round-bottomed four-necked flask was equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a thermometer, and a nitrogen-gas inlet. Octa DMS-POSS based on Octa TMA-POSS were prepared with the organic solvent. 0.003 mol Octa TMA-POSS was added into the flask. 0.27 mol DMCS and 25 mL organic solvent were added dropwise into the flask under the stirring conditions. The mixed system was stirred for another 1–24 h at 10–40 °C in a water bath. Then the flask was cooled to 0 °C. 500 mL of cooled distilled water was dripped and the system was stirred for another 30 min. The organic phase was then separated from the aqueous phase using a separating funnel. The organic products were then washed with deionized water for several times to neutralize. The solvents were excluded from the system with vacuum distillation. After filtration, washing with methanol and vacuum drying, the white precipitate products were obtained as Octa DMS-POSS.

2.2.2 Preparation of VAPOSS

Briefly, a 100 ml round-bottomed four-necked flask was equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a thermometer, and a nitrogen-gas inlet. VAPOSS based on Octa DMS-POSS and VAc were prepared by adding VAc and Octa DMS-POSS with specified ratios into the flask. Chloroplatinic acid as catalyst was added into the system. After the addition was finished, the polymerization was kept at 60 °C for 48 h. The addition reaction with compounds with unsaturated bonds is one of the fundamental reactions in organosilicone. The hydrogen group in Octa DMS-POSS undergoes an addition reaction with the double bond of VAc. After the reaction, the solvents were excluded from the system with vacuum distillation. After filtration and vacuum drying, the white precipitate products were obtained as VAPOSS. The product was vacuum-dried before use. The synthesis process of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS was summarized in Scheme 1. The VAPOSS1, VAPOSS2, VAPOSS3, VAPOSS4, and VAPOSS5 products were obtained with the molar ratio of POSS and VAc was 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:6 and 1:8, respectively.

Synthesis process of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS.

2.3 Characterization

The yield was measured by gravimetric analysis. The Octa DMS-POSS sample weighed m1. The theoretical production of Octa DMS-POSS was weighed m2. The yield was calculated by the equation (2-1):

Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was detected using a model V70 infrared spectrophotometer at ambient temperature. The test was carried out with 16 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1 within 500–3500 cm−1.

1H NMR measurements were conducted on a BRUKER AVANCE III HD 400 M spectrometer (Germany) at 400 MHz in CDCl3. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal reference.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to determine the crystallinity of the samples. The tests were performed at room temperature with a Siemens D5000 X-ray diffractometer with a CuKα radiation source operated at 40 kV and 30 mA. Patterns were recorded by monitoring diffractions from 5° to 70°. The scan speed was 0.02°/min.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere from 25 °C to 750 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Five VAPOSS samples with differing VAc content were analyzed.

The thermal properties were measured with a Q200 differential scanning calorimeter (DSC, TA Instruments Company, USA) under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min over a temperature range of 100 °C–350 °C. The data from the first heating run are reported. The samples were subjected to the heating under a nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 10 ml/min).

The contact angles of water on the surface of the samples were measured using a JC2000A contact angle goniometer at room temperature. Three parallel measurements at different points were performed to calculate the average static contact angle.

The samples were coated with gold using an Edwards S 150 A sputter coater. The morphology of the samples was examined by the scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 50 kV.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) adsorption isotherms at 273.0 K were evaluated on a Micrometrics TriStar II 3020. The samples were degassed at 150 °C for at least 12 h before the measurements.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Optimization research of Octa DMS-POSS synthetic process

The synthesized Octa DMS-POSS was followed by the substitution reaction mechanism. The -SiH(CH3)2 group replaced the tetramethylammonium ion on Octa TMA-POSS. It was an alkylation reaction. It was commonly reported that the yield is correlated with the reaction conditions, such as the reaction temperature, reaction time, and solvent type. The yield can be modified by optimizing the reaction conditions. Therefore, the effect of the reaction temperature, reaction time, and solvent type on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS will be discussed in the following part.

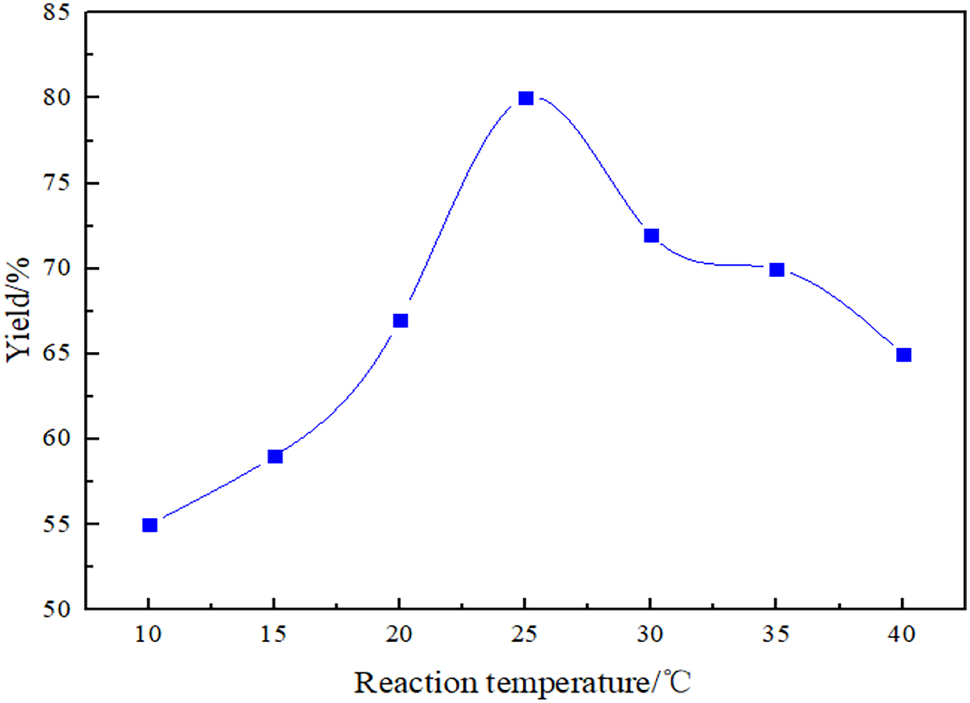

3.1.1 Effect of the reaction temperature on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS

The reaction time was fixed at 12 h and the solvent was chosen as DMF, respectively, in order to evaluate the effect of reaction temperature on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS. The effect of reaction temperature on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS is shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, the reaction temperature has a great effect on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS. With the reaction temperature increasing from 10 °C to 25 °C, the yield increased from 55 % to 80 %. It can be easily understood that a higher temperature has a positive impact on the substitution reaction rates, while this impact would be compromised when the temperature is further increased to 40 °C. Alkylation reaction was a hydrolysis condensation process, and the hydrolysis condensation process between DMCS and Octa TMA-POSS was an exothermic reaction. With the temperature increased, the average kinetic energy of molecules increased, making collisions between molecules more frequent and intense. In this way, the probability of effective collisions between reactant molecules will increase, thereby promoting the progress of the reaction. There were more side reactions when the reaction temperature was too high, the hydrolysis rate is relatively fast, and linear polydimethylsiloxane instead of cage structure is tends to form, resulting in a decrease in yield [22]. Therefore, the yield had been increased, and the optimized reaction temperature is 25 °C.

Effect of the reaction temperature on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS.

3.1.2 Effect of the reaction time on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS

The reaction temperature was fixed at 25 °C and the solvent was chosen as DMF, respectively, in order to evaluate the effect of reaction time on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS. The effect of the reaction time on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS is shown in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, the yield of Octa DMS-POSS first increased and then basically unchanged with increasing the reaction time. With the reaction time increasing from 1 h to 12 h, the yield of Octa DMS-POSS increased from 40 % to 80 %. The optimized reaction time to reach the highest yield is 12 h of reaction time. When the reaction time was further extended, the yield basically unchanged. As the reaction time increased, the concentration of reactants decreased, and the yield of products increased. When the reaction proceeded to a certain time, the yield was basically stable, and the extending reaction time had little effect on the yield. Therefore, it can be explained that the reaction time has an optimal value, rather than the longer the better.

Effect of the reaction time on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS.

3.1.3 Effect of the solvent type on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS

The reaction temperature and time were fixed at 25 °C and 12 h, respectively, in order to evaluate the effect of solvent type on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS. The relationship between yield and reaction solvent was investigated by sequentially selecting ethanol, hexane, and DMF as solvents. The results are shown in Table 1. The reagent DMCS was easily hydrolyzed, when ethanol was used as solvent. DMCS was inclined to the side reaction of hydrolysis condensation rather than substitution reaction, resulting in a low yield. Hexane was a non-polar solvent, and it was difficult to dissolve the reactants, so the substitution reaction rate was slow, also resulting in a low yield. This reaction was an ionic nucleophilic substitution reaction, and the polar solvent was a good solvent for reactants and products. Therefore, a high yield of products was obtained by using the polar solvent DMF. Therefore, the optimized reaction solvent is DMF.

Effect of the solvent type on the yield of Octa DMS-POSS.

| Solvent | Ethanol | Hexane | DMF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield/% | 15.2 | 24.5 | 80 |

3.2 ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS3

The VAPOSS3 sample, with an intermediate molar ratio of Octa DMS-POSS to VAc 1:4, was selected as a representative candidate for detailed structural characterization (e.g., ATR-FTIR, NMR, XRD, SEM) to confirm the successful chemical modification. All VAPOSS samples were subjected to performance evaluations including TGA, DSC, contact angle measurements, and CO2 adsorption tests.

The analysis of samples by ATR-FTIR has proved to be very useful in detecting the absorption peaks that are characteristic of the samples during the modification. In Figure 3, traces (a) and (b) represent the transmission ATR-FTIR spectra collected from Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS3, respectively. In Figure 3a, the absorption peaks at 2,973 cm−1 was assigned to -CH3. The peaks at 1,400 cm−1 were attributed to the bending vibration absorption of C–H. The characteristic absorption peaks at 1,107 cm−1 are attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of the Si–O–Si cages, which is a hallmark of the polyhedral silsesquioxane framework [23], [24], [25]. The characteristic peaks at 878 cm−1 were due to the rocking vibration of Si–H. In addition, compared to Figure 3a, the characteristic peaks of C=O at 1720 cm−1 and the bending vibration at 1,457 cm−1 of the hydrocarbon groups in Figure 3b confirm the introduction of VAc [26]. The absorption peaks at 2,958 and 2,837 cm−1 were assigned to -CH3 and -CH2. The peaks at 1,079 cm−1 were associated with the stretching vibrations of -C-O-C. A peak at 815 cm−1 can be found, which is the characteristic peak of Si–C. The absence of an absorption peak in the 1,600–1,500 cm−1 range, which is characteristic of the carbon-carbon double bond from the vinyl group of VAc, confirms the complete consumption of the vinyl monomers and thus the success of the reaction [26]. The result of ATR-FTIR shows that the modification between VAc and Octa DMS-POSS has happened and the modification indeed occurred.

ATR-FTIR absorption peaks of Octa DMS-POSS (a) and VAPOSS3 (b).

3.3 Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS3

Figure 4 showed the 1H NMR spectra and chemical shift of different protons of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS3. Chemical shifts were obtained with respect to deuterated chloroform (δ = 7.28 ppm). In trace 4a, the characteristic peaks at 1.55 ppm were attributed to the -SiH proton. The characteristic signal at 0.87–0.12 ppm corresponded to the -SiCH3 proton attached to the Si atom [3]. Compared with spectrum 4a, the 1H NMR spectrum 4b changed in part. In trace 4b, the typical singlet peaks singlet at 5.59 ppm were due to the -CH3 proton attached to the ester groups originated in VAc. The peaks at 3.55 ppm were corresponding to protons in -CH2- attached to an oxygen atom. The characteristic signal at 1.19 ppm were corresponding to -CH3 attached to the Si atom. The NMR results were consistent with the FTIR results.

The 1H NMR spectra of Octa DMS-POSS (a) and VAPOSS3 (b).

3.4 XRD patterns of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS

X-ray diffraction was employed to investigate the changes in the crystalline structure of the POSS framework upon functionalization with vinyl acetate. The XRD patterns of Octa DMS-POSS (a), VAPOSS3 (b), and VAPOSS5 (c) are shown in Figure 5. The precursor, Octa DMS-POSS (trace 5a), exhibited a highly crystalline structure, as evidenced by numerous sharp diffraction peaks at 6.3°, 9.2°, 9.9°, 12.8°, 18.2°, 23.1°, and 26.9°. This pattern is characteristic of a well-defined, ordered octahedral silsesquioxane cage. In contrast, the pattern of VAPOSS3 (trace 5b) demonstrates a significant loss of long-range order. The multitude of sharp peaks present in the precursor has disappeared, confirming the disruption of the original crystalline lattice. This amorphization is likely due to the stochastic distribution of VAc side groups on the POSS cage. While the average degree of substitution is 4 VAc groups per cage, the actual composition is a mixture of cages with varying substitution degrees, which prevents the formation of a periodic crystalline structure. A relatively sharp feature is observed at approximately 18.5°. This peak could be an artifact or, more plausibly, it may indicate the presence of a small population of domains with residual local order. However, its intensity is low, confirming that the material is predominantly amorphous.

XRD pattern of Octa DMS-POSS (a), VAPOSS3 (b) and VAPOSS5 (c).

To further investigate this structural evolution, the XRD pattern of the fully substituted VAPOSS5 (trace 5c) was examined. Notably, VAPOSS5 exhibits a completely featureless, broad amorphous halo. The sharp feature seen at ∼18.5° in VAPOSS3 is absent, which supports the interpretation that it was related to an intermediate or less homogeneous structural state. The complete amorphization of VAPOSS5 provides strong evidence that a high degree of functionalization with bulky VAc groups effectively destroys the crystalline packing of the POSS cages, resulting in a fully amorphous material. This trend from crystalline to partially ordered and finally to fully amorphous solidifies the conclusion that VAc modification progressively disrupts the crystalline structure [1], 3], 14].

3.5 TGA curves of VAPOSS

The weight loss as a function of temperature was recorded for each VAPOSS as shown in Figure 6. As displayed in Figure 6, the degradation temperatures (Td5 and Td10) and char yields were 240.3 °C, 282.3 °C, and 29 % for VAPOSS1; 241.6 °C, 281.6 °C, and 32 % for VAPOSS2; 249.5 °C, 300.8 °C, and 43 % for VAPOSS3; 235.7 °C, 277.1 °C, and 38 % for VAPOSS4; and 242.8 °C, 283.9 °C, and 40 % for VAPOSS5, respectively. It also can be seen from Figure 6 that the thermal decomposition of VAPOSS exhibits two distinct stages. The primary decomposition occurs between 200 °C and 400 °C, while all VAPOSS samples start significant weight loss, corresponding to the degradation of organic components, including VAc groups and the Si-OR groups. The weight loss originates from the carbonization and volatilization of organic segments. The weight of VAPOSS3 is the lowest (9.91 %). The second thermal decomposition occurs between 400 °C and 600 °C, this stage mainly involves the decomposition of POSS framework. Medium molar ratio of POSS to VAc significantly improves stability. Its weight loss is 2.20–5.51 % lower than other samples, attributed to moderate VAc acts as a bridging agent to form a denser Si–O–Si network, reducing free Si-OR groups. In contrast, too low or too high VAc content creates network defects, accelerating small-molecule volatilization and weight loss. This trend also indicates that higher molar of VAc reduces the overall thermal stability of the VAPOSS hybrid, likely due to the lower thermal resistance of the VAc moieties compared to the inorganic POSS core [21].

TGA curves of VAPOSS with a different molar ratio of POSS to VAc.

3.6 DSC curves of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS

The thermal behavior of samples with different molar ratios of Octa DMS-POSS to VAc was investigated using DSC, and the results are shown in Figure 7. The DSC curves reveals a distinct thermal event pattern: a small exothermic peak followed immediately by a larger endothermic peak.

DSC curves of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS with a different molar ratio of POSS to VAc.

The exothermic event is attributed to cold crystallization, a process in which the amorphous material gains sufficient mobility upon heating to reorganize into an ordered, crystalline structure. This process releases heat. The subsequent sharp endothermic peak corresponds to the melting of these newly formed crystals. Therefore, the thermal profiles are best described as a cold-crystallization and melting process.

As shown in Figure 7, the melting temperatures for Octa DMS-POSS and the VAPOSS series with increasing VAc content are 301.1 °C, 301.9 °C, 305.7 °C, 306.8 °C, 309.3 °C, and 337.5 °C, respectively. Notably, the melting temperature shows a clear upward trend with increasing VAc content. This trend can be explained by the role of VAc in the crystallization process. The incorporation of VAc groups initially disrupts the pristine crystalline order of Octa DMS-POSS, as confirmed by XRD, resulting in a predominantly amorphous structure at room temperature. However, upon heating, the VAc side chains may facilitate the reorganization of the POSS cages into a new, more stable ordered structure during the cold-crystallization step. The increasing VAc content likely influences the size, perfection, or stability of these newly formed crystals, leading to the observed increase in melting point. The significant jump in melting temperature for the sample with the highest VAc content suggests a possible critical concentration effect or the formation of a distinctly different and more thermally stable crystalline phase.

The systematic increase in the melting point with higher VAc content can be rationalized by the enhanced intermolecular interactions, such as dipole-dipole forces between the polar acetate groups of adjacent VAPOSS cages. These stronger interactions create a more thermally stable structure, thereby requiring more energy (manifested as a higher temperature) to melt the newly formed crystalline domains. Alternatively, the VAc side chains may act as flexible spacers that facilitate molecular reorganization during the cold-crystallization process, leading to the formation of crystals with higher perfection and stability. While the exact mechanism warrants further investigation, the clear correlation between composition and thermal behavior underscores the tunability of the VAPOSS system. Future studies employing variable-temperature XRD or detailed rheological analysis could provide deeper insights into the crystallization kinetics and microstructure evolution responsible for these thermal properties.

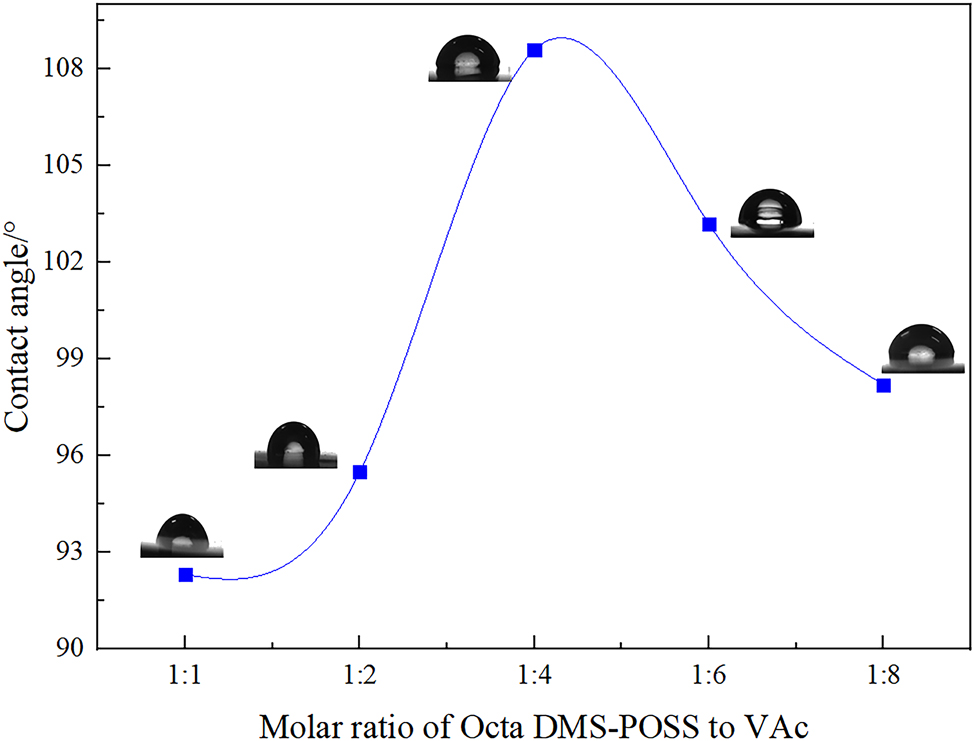

3.7 Contact angle of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS

In this research, Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS were uniformly loaded on the surface of the glass slide, and the static contact angle of water on its surface was measured. The results are shown in Figure 8. It can be seen from Figure 8 that as the molar ratio of Octa DMS-POSS to VAc increased, the contact angle first increased from 92.3° to 108.6° and then decreased slightly to 98.2°. This is mainly because Octa DMS-POSS has a cage-like structure, as well as the characteristics of siloxane structure and giant molecules, which can demonstrate certain resistance to water molecule wetting. With the increasement of VAc, VAc was introduced into the cage-like structure of POSS, and the ester group-based structure in VAc also has a certain hydrophobicity [27]. Therefore, the synergistic effect of the siloxane structure and ester group structure increased the contact angle. The better molar ratio of POSS to VAc was 1:4 according to the results of the contact angle results.

Contact angle of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS.

3.8 SEM micrographs of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS

To evaluate the surface morphologies of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS3, scanning electron microscopy was performed, and the micrographs of Octa DMS-POSS (a) and VAPOSS3 (b) are both shown in Figure 9. It could be seen that the Octa DMS-POSS particles were relatively loose and have more pores in Figure 9a. SEM measurements revealed that there is an obvious change of morphologies after the addition of VAc. Compared to Figure 9a, there was no pore structure on the surface of VAPOSS3 particles in Figure 9b. The SEM images in Figure 9b reveal that VAPOSS3 comprised relatively uniform solid spherical particles of a similar shape having dimensions of several micrometers. VAc was introduced into the cage structure through the cross-linking reaction during the preparation process of VAPOSS. The POSS was embedded inside the system and the original pore structure disappeared, forming a structure connected by small nanoparticles.

SEM micrographs of Octa DMS-POSS (a) and VAPOSS3 (b).

3.9 Carbon dioxide adsorption

Recently, as CO2 is a key greenhouse gas and considered a cause of global warming, researchers have focused on the CO2 capture technologies. POSS is considered to be a useful material for CO2 adsorption. To evaluate its potential application in CO2 capture, CO2 adsorption measurements were carried out at 273.0 K and the adsorption isotherms are shown in Figure 10. The CO2 uptakes of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS were found to be 0.80 mmol⋅g−1 (3.52 wt%), 1.16 mmol⋅g−1 (5.10 wt%), 1.22 mmol⋅g−1 (5.37 wt%), 1.46 mmol⋅g−1 (6.42 wt%), 1.48 mmol⋅g−1 (6.51 wt%), 1.50 mmol⋅g−1 (6.60 wt%) at 273 K, respectively, which were measured up to 800 mmHg. As expected, the introduction of acetate groups in VAPOSS resulted in materials with enhanced CO2 adsorption properties. With the molar ratio of VAc to POSS increased, the adsorption capacity increased. The adsorption capacity is higher than that of the Octa DMS-POSS. This result may be attributed to the introduction of -COOCH3 units in the VAc structure. The acetate groups have good affinity for CO2 [28]. The oxygen atoms in the acetate groups have a certain degree of electronegativity, and these atoms could undergo Lewis acid- Lewis base interactions with the positively charged C atoms in CO2. Furthermore, the O atom of CO2 can form weak hydrogen bonds with the electron-deficient H atoms in these structures [29], and the resulting electronic effect forms a virtual multicomponent ring structure, which can stabilize the original Lewis acid-base interaction and further enhance the interaction with CO2. Therefore, the introduction of acetate groups into VAPOSS led to a higher CO2 adsorption than that of POSS. The CO2 adsorption capacity increases with the VAc to POSS molar ratio, although the enhancement becomes less pronounced at higher ratios (e.g., VAPOSS4 to VAPOSS5). This trend suggests that the improved capacity is not solely due to the increased number of CO2-philic acetate groups. A competing factor is the significant change in morphology observed by SEM (Figure 9). The transformation from a loose, particulate structure in Octa DMS-POSS to dense, non-porous spherical particles in the VAPOSS series likely limits the internal diffusion and accessibility of CO2 to the adsorption sites. Therefore, the overall adsorption capacity is determined by a balance between the favorable chemical interactions provided by the VAc groups and the unfavorable morphological changes that reduce surface area and porosity.

Carbon dioxide adsorption isotherms of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS at 273.0 K.

Moreover, the CO2 adsorption capacity of VAPOSS is not only significantly higher than that of its precursor, Octa DMS-POSS, but also demonstrates competitive performance among porous organic-inorganic hybrid materials. For instance, its uptake is notably higher than that of many amine-functionalized POSS porous polymers, such as those reported by Wang et al., which exhibited capacities in the range of 0.63–1.01 mmol⋅g−1 at 298 K and 1 bar [15]. When compared to conventional adsorbents, the capacity of VAPOSS is comparable to or exceeds that of several zeolites-for example, Zeolite 13X, which shows an uptake of about 4.7 mmol⋅g−1 under similar conditions [30]. Although this value remains lower than those of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) such as Mg-MOF-74 (∼8.5 mmol⋅g−1 at 298 K) [31], the VAPOSS system offers a compelling combination of moderate CO2 uptake, excellent thermal stability, and highly tunable surface functionality. These characteristics underscore the potential of VAPOSS as a versatile and practical adsorbent platform, particularly in applications where a balance of performance, stability, and synthetic flexibility is essential.

4 Conclusions

A new type of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) has been obtained with vinyl acetate (VAc) as the functional monomer. The structures of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS are characterized by the attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance. The effect of preparation conditions is optimized by testing the yield. The effect of vinyl acetate molar ratio on the crystalline, thermal stability, and contact angle is measured through the X-ray diffraction, differential scanning calorimeter, and contact angle tests. The micrographs of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS are also characterized by the scanning electron microscope. The optimum preparation conditions are the reaction temperature 25 °C, the reaction time 12 h, and the reaction solvent DMF. The highest yield is 80 %. ATR-FTIR and NMR results showed that Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS were successfully synthesized. The crystalline structure was weakened after it was modified with VAc. With the molar ratio of POSS to VAc increasing, the melting temperature increased and the contact angle increased first and then decreased slightly. The better molar ratio of POSS to VAc is 1:4 according to the discussion of contact results. The micrographs of Octa DMS-POSS and VAPOSS show obvious differences. The carbon dioxide sorption results illustrated that the synthesized VAPOSS materials could potentially be utilized as adsorbents to store and capture CO2.

Future studies will include quantitative 1H NMR analysis to determine the precise degree of substitution for each sample, which will provide a more detailed understanding of the structure-property relationships.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (contract grant number: 52204045), the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (contract grant number: 2024JC-YBMS-119), the Academic Backbone Training Project Funded by Xianyang Normal University (contract grant number: XSYXSGG202105), the Fourteenth Batch of College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Base Teams (projects) Settled in Xianyang Normal University (contract grant number: XSYC202512), the Provincial College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program Funding Project (S202510722085) and the authors would also like to thank the Scientific Research Program Funded by Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (contract grant number: 24JC070).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, X.W. and G.M.; Methodology, X.W.; Writing Original Draft Preparation, X.W., G.M. W.W., and Y.Y.; Writing-Review and Editing, X.W., G.M. W.W., and Y.Y.; Funding Acquisition, X.W. and G.M.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Xiao, L, Lai, Y, Song, Q, Cai, J, Zhao, Y, Hou, L. POSS-based ionic polymer catalyzed the conversion of CO2 with epoxides to cyclic carbonates under solvent- and cocatalyst-free conditions at ambient pressure. J Environ Chem Eng 2023;11:109958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109958.Search in Google Scholar

2. Guo, L, Lamb, KJ, North, M. Recent developments in organocatalysed transformations of epoxides and carbon dioxide into cyclic carbonates. Green Chem 2021;23:77–118. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0gc03465g.Search in Google Scholar

3. Gabriel, G, May-Britt, H, Gertrude, K, Christian, S, Thijs, P, Nicolas, R, et al.. Investigation of amino and amidino functionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS®) nanoparticles in PVA-based hybrid membranes for CO2/N2 separation. J Membr Sci 2017;554:161–73.10.1016/j.memsci.2017.09.014Search in Google Scholar

4. Romano, MC, Anantharaman, R, Arasto, A, Ozcan, DC, Ahn, H, Dijkstra, JW, et al.. Application of advanced technologies for CO2 capture from industrial sources. Energy Proc 2013;37:7176–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.655.Search in Google Scholar

5. Gautam Chaudhary, A, Sahoo, S. Experimental investigation on adsorbent composites for CO2 capture application: an attempt to improve the dynamic performance of the parent adsorbent. Int J Heat Mass Tran 2023;203:123796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123796.Search in Google Scholar

6. Li, G, Wang, L, Ni, H, Pittman, CU. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) polymers and copolymers: a review. J Inorg Organomet P 2001;11:123–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015287910502.10.1023/A:1015287910502Search in Google Scholar

7. Li, S, Jiang, X, Yang, Q, Shao, L. Effects of amino functionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes on cross-linked poly(ethylene oxide) membranes for highly-efficient CO2 separation. Chem Eng Res Des 2017;122:280–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2017.04.025.Search in Google Scholar

8. Demirtas, C, Dilek, C. Enhanced solubility of siloxy-modified polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes in supercritical carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluid 2019;143:358–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2018.09.015.Search in Google Scholar

9. Nischang, O, Brüggemann, I, Teasdale, I. Facile, single-step preparation of versatile, high-surface-area, hierarchically structured hybrid materials. Angew Chem Int Ed 2011;50:4592–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201100971.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Brown, D, Neyertz, S, Raaijmakers, MJT, Benes, NE. Sorption and permeation of gases in hyper-cross-linked hybrid Poly(POSS-imide) networks: an in silico study. J Membr Sci 2019;577:113–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2019.01.039.Search in Google Scholar

11. Mohamed, MG, Liu, NY, El-Mahdy, AFM, Kuo, SW. Ultrastable luminescent hybrid microporous polymers based on polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane for CO2 uptake and metal ion sensing. Micropor Mesopor Mat 2021;311:110695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110695.Search in Google Scholar

12. Wang, D, Li, L, Yang, W, Zuo, Y, Feng, S, Liu, H. POSS-based luminescent porous polymers for carbon dioxide sorption and nitroaromatic explosives detection. RSC Adv 2014;4:59877–84. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra11069b.Search in Google Scholar

13. Mohamed, MG, Kuo, SW. Polybenzoxazine/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) nanocomposites. Polymers 2016;8:225. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8060225.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Chen, WC, Ahmed, MMM, Wang, CF, Huang, CF, Kuo, SW. Highly thermally stable mesoporous Poly(cyanate ester) featuring double-decker–shaped polyhedral silsesquioxane framework. Polymer 2019;185:121940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121940.Search in Google Scholar

15. Wang, D, Yang, W, Feng, S, Liu, H. Amine post-functionalized POSS-based porous polymers exhibiting simultaneously enhanced porosity and carbon dioxide adsorption properties. RSC Adv 2016;6:13749–56. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra26617c.Search in Google Scholar

16. Wu, J, Mather, PT. Poss polymers: physical properties and biomaterials applications. Polym Rev 2009;49:25–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583720802656237.Search in Google Scholar

17. Zhang, W, Müller, AHE. Architecture, self-assembly and properties of well-defined hybrid polymers based on polyhedral oligomeric silsequioxane (POSS). Prog Polym Sci 2013;38:1121–62.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.03.002Search in Google Scholar

18. Hussain, H, Shah, SM. Recent developments in nanostructured polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane-based materials via ‘controlled’ radical polymerization. Polym Int 2014;63:835–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.4692.Search in Google Scholar

19. Kuo, SW, Chang, FC. POSS related polymer nanocomposites. Prog Polym Sci 2011;36:1649–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

20. Bhagiyalakshmi, M, Anuradha, R, Park, SD, Jang, HT. Octa(aminophenyl)silsesquioxane fabrication on chlorofunctionalized mesoporous SBA-15 for CO2 adsorption. Micropor Mesopor Mat 2010;131:265–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gamal Mohamed, M, Tsai, MY, Wang, CF, Huang, CF, Danko, M, Dai, L, et al.. Multifunctional polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) based hybrid porous materials for CO2 uptake and iodine adsorption. Polymers-Basel 2021;13:221. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13020221.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Qin, ZL, Yang, RJ, Zhang, WC, Jiao, QJ. Mechanistic insights into the synthesis of fully condensed polyhedral octaphenylsilsesquioxane. Chin J Chem 2019;37:1051–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjoc.201900170.Search in Google Scholar

23. Huang, Y, Gong, S, Huang, R, Cao, HJ, Lin, YH, Yang, M, et al.. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane composited gel polymer electrolyte based on matrix of PMMA. RSC Adv 2015;5:45908–18. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra06860f.Search in Google Scholar

24. Wang, B, Shi, MX, Ding, J, Huang, ZX. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: synthesis and anti-oxidation properties. E-Polymers 2021;21:316–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly-2021-0031.Search in Google Scholar

25. Shivakumar, R, Bolker, A, Tsang, SH, Atar, N, Verker, R, Gouzman, I, et al.. POSS enhanced 3D graphene-polyimide film for atomic oxygen endurance in low earth orbit space environment. Polymer 2020;194:122270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122270.Search in Google Scholar

26. Ma, G, Wang, L, Wang, XR, Wang, CJ, Li, X, Li, L, et al.. Preparation and properties of poly(vinyl acetate) adhesive modified with vinyl versatate. Molecules 2023;28:6634. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28186634.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Cortez-Lemus, NA, Licea-Claverie, A. Preparation of a mini-library of thermo-responsive star (NVCL/NVP-VAc) polymers with tailored properties using a hexafunctional xanthate RAFT agent. Polymers 2018;10:20. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10010020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Kilic, S, Wang, Y, Johnson, JK, Beckman, EJ, Enick, RM. Influence of tert-amine groups on the solubility of polymers in CO2. Polymer 2009;50:2436–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2009.03.012.Search in Google Scholar

29. Trung, NT, Nguyen, MT. Interactions of carbon dioxide with model organic molecules: a comparative theoretical study. Chem Phys Lett 2013;581:10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2013.05.048.Search in Google Scholar

30. Liang, Z, Marshall, M, Chaffee, AL. CO2 adsorption-based separation by metal organic framework (Cu-BTC) versus zeolite (13X). Energy Fuels 2009;23:2785–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef800938e.Search in Google Scholar

31. Yazaydın, AO, Snurr, RQ, Park, TH, Koh, K, Liu, J, LeVan, MD, et al.. Screening of metal-organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture from flue gas using a combined experimental and modeling approach. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:18198–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja9057234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)