Abstract

Pumice aggregates stand out with their low density and high porosity. However, their high water retention capacity and low mechanical strength are the primary disadvantages limiting their use in lightweight concrete production. In this study, pumice aggregates with particle sizes ranging from 4 to 16 mm were coated with polyester, known for its superior adhesion and insulation properties, to produce polyester-coated pumice aggregates. Subsequently, five different lightweight concrete mixtures were prepared using 450 kg/m³ cement, incorporating coated and non-coated pumice aggregates as coarse aggregates at replacement ratios of 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%. Aggregate tests included specific gravity and water absorption, while fresh concretes were evaluated for unit weight and slump. Hardened concretes were tested for dry unit weight, water absorption, ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), compressive strength, freeze–thaw resistance, and thermal conductivity. The results revealed that the polyester coating increased the specific gravity of pumice aggregates by up to 45% and reduced water absorption by 85%. The use of coated aggregates increased the unit weight of the concrete but resulted in a reduction in compressive strength and UPV. Despite a compressive strength reduction of up to 58% depending on the coated aggregate content, concrete specimens produced with polyester-coated aggregates exhibited the highest performance in terms of freeze–thaw resistance and thermal conductivity.

1 Introduction

The utilization of concrete requires care and attention throughout its entire phases, commencing from the manufacturing phase and extending to its eventual application. Concrete is by far the most common and widely used construction material. It is versatile, adaptable, economical, and, if properly made, durable [1]. In recent years, the concrete industry has experienced significant advancements in technology, leading to the emergence of specialized concretes. Special concretes are concretes designed to satisfy various requirements in accordance with their intended use and place of use. Structural lightweight concrete, heavy concrete, self-compacting concrete, and concrete with insulation properties are among the special concrete types [2].

The use of lightweight concrete, which is one of the special types of concrete and stands out with its much lower unit weight compared to conventional concrete in the structural system of the buildings, reduces the dead load and the horizontal earthquake forces acting on the structure. Therefore, possible earthquake damages can be reduced to a certain degree with the use of lightweight concrete [3,4]. In addition, as the unit weight of concrete decreases, the thermal conductivity also decreases [5]. Lightweight concrete can be produced through various methods, including introducing a porous structure to the cement paste (like foamed concrete), excluding fine aggregates from the concrete mixture (like porous concrete), or utilizing lightweight aggregates as replacements [6]. In the lightweight concrete production process, artificial aggregates such as expanded perlite, expanded clay, fly ash, and shale, as well as natural aggregates such as pumice, diatomite, raw perlite, volcanic tuff, and volcanic slag are used. Although artificial aggregates were mostly used in the production of lightweight concrete until the 1980s, later natural aggregates were used due to energy costs [7].

Aggregates, which are one of the basic components of concrete, are approximately 75% by volume in concrete [8]. Pumice, one of the lightweight aggregates, is a glassy rock type that gains a porous structure due to the sudden cooling and gases in it, leaving the body of lava reaching the earth as a result of volcanic activities. Pumice that has numerous independent voids is characterized by its low unit weight, low sound and thermal conductivity, great resistance to external influences, and ease of production [9]. While pumice finds application in various industries, its predominant utilization is observed within the construction industry. Pumice, which is a valuable raw material due to its physical and chemical properties, has great importance for the construction sector [10].

There are many studies in which volcanic pumice is used as coarse and/or fine aggregate in concrete. When the studies on lightweight concrete with pumice aggregate were reviewed, it was determined that the dry unit weights of mineral-added lightweight concrete produced by using pumice as coarse aggregate ranged from 1,800 to 1,860 kg/m3, and their compressive strengths can reach up to 39 MPa [11]. Sancak et al. reported that the unit weights of concrete specimens produced using pumice aggregate and silica fume-substituted cement (0, 5, and 10%) were 1,650–1,720 kg/m3, water absorption rates were 5.8–8.25%, and compressive strengths were in the range of 16.6–22.6 MPa [12].

Karthika et al. stated in their study that the water absorption values of the concrete samples produced by replacing coarse aggregate with pumice aggregate at different ratios such as 50, 80, and 100% were in the range of 1.6–4.1%, and compressive strengths were in the range of 6.9–38.4 MPa, and that the water absorption rate was high and compressive strength was low in the samples produced with pumice aggregate [13]. Hossain et al. reported that the unit weights of concrete specimens containing 50, 75, and 100% pumice (maximum size 12.5 mm) as a coarse aggregate substitute at normal weight varied between 1,850 and 2,180 kg/m3 and 28-day compressive strengths were 35, 31, and 27 MPa, respectively [14]. Türkmen et al. indicated that the use of pumice in lightweight concretes with different cement proportions and slump values increased the freeze–thaw performance in their study in which they used pumice aggregates as a replacement for normal aggregates [15]. In a study in which coarse pumice aggregate was used by replacing it with normal aggregate (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30%) and the freeze–thaw effect was investigated, it was observed that the use of pumice at 10, 15 and 20%, respectively, gave the best results [16].

In a study where cement proportions (200, 250, 300, 350, 400, and 500 kg/m3), slump amount (3 ± 1, 5 ± 1, 7 ± 1 cm), and pumice ratio (0, 25, 50, 75 and 100%) were considered as variables, it was determined that the unit weights were 1,330–2,270 kg/m3 and the thermal conductivity coefficients were in the range of 0.77–1.46 W/mK of 300 kg/m3 cement concrete samples at constant slump values. It was pointed out that the thermal conductivity decreased as the unit weight decreased [17]. Lynda Amel et al. showed that when pumice is used as coarse aggregate, the thermal conductivity of concretes can be changed between 0.48 and 0.53 W/mK by substituting the standard weight of fine aggregate type [18].

In a study, coated pumice aggregate with a mixture of cement, pumice powder, and silica fume was used as coarse aggregate, and concrete specimens with a unit weight of 1,320 kg/m3, a thermal conductivity coefficient of 0.318 W/mK, a 28-day compressive strength of 21.6 MPa, and a freeze–thaw resistance up to 100 cycles were developed [19]. Salli Bideci et al. coated coarse pumice aggregates with three different polymers. As a result of the polymer coating, the unit weight of the pumice aggregates increased by up to 48%, while their water absorption rate decreased significantly from 40% to as low as 2% [20]. Vahabi et al. employed PVA and SBR latex polymers to coat scoria and leca aggregates for the production of lightweight concrete. The study revealed that the water absorption rates of the lightweight aggregates were reduced by 82% following the coating process [21]. Özgüler et al. coated coarse pumice aggregates obtained from two different sources with a cement paste. They reported that, following the cement paste coating, the water absorption rates of the aggregates decreased by 50.49 and 78.32%, respectively [22]. Bideci et al. coated pumice aggregates with polyester resin for use in lightweight concrete production. They observed that the specific gravity of the aggregates increased by up to 17% after the polyester coating process, while the water absorption rates decreased by up to 95% [23].

The literature review reveals that the high water absorption capacity of pumice aggregates can be mitigated by the application of various coating materials. However, the number of studies focusing on the use of polymer-coated pumice aggregates remains limited. The objective of this study is to develop a novel lightweight aggregate by reducing the high water absorption rate of pumice, a natural lightweight aggregate, through polyester coating.

2 Materials and methods

This study investigates the feasibility of using polyester-coated aggregates in the production of lightweight concrete. In this study, pumice aggregates with a particle size of 4–16 mm were coated with polyester to produce coated aggregates. Subsequently, five different series of lightweight concrete samples with a cement dosage of 450 kg/m³ were produced using crushed stone aggregates with a particle size of 0–4 mm, as well as coated and non-coated aggregates with a particle size of 4–16 mm. The unit weights and slump values of the fresh concrete were determined. Additionally, the dry unit weight, water absorption, ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), compressive strength (at 28 and 90 days), freeze–thaw resistance (50 and 100 cycles), and thermal conductivity of the hardened concrete samples were experimentally evaluated.

2.1 Materials

In this study, coarse aggregate polyester coated and non-coated pumice with 4–8 and 8–16 mm grain sizes and fine aggregate natural crushed stone sand with 0–4 mm grain sizes were used. CEM I 42.5R cement manufactured in accordance with TS EN 197-1 standard [24] was used as a binder. At the end of the polyester coating process, marble dust with a particle size of 100 µm was used to separate the aggregates. Chemical analysis of the mineral-based materials is given in Table 1.

Chemical analysis of the materials used (%)

| Chemical composition | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | K2O | Na2O | SO3 | Loss ignition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pumice | 65.75 | 13.85 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 0.75 | 2.85 | 2.80 | — | 4.25 |

| CEM I 42.5R | 18.75 | 5.02 | 2.50 | 64.05 | 1.15 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 3.15 | 3.80 |

| Marble powder | — | — | 0.02 | 31.10 | 23.20 | 0.01 | 0.51 | — | 45.29 |

The polyester resin employed in this research is an unsaturated cast-based polyester. Polyester finds common application in filled casting scenarios, such as in artificial marble, owing to its notable filler acceptance and moderate shrinkage attributes. Additionally, it is utilized in cases where expedited curing and exceptional heat resistance are not imperative. The mechanical and physical attributes of the utilized polyester are detailed in Table 2 [25].

Technical properties of the polyester

| Elongation (tensile) | Elongation (flexural) | Flexural strength | Modulus of elasticity | Water absorption | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 5.94% | 138 MPa | 3,047 MPa | 0.16% | 1.125 |

2.2 Polyester coating procedure of pumice aggregates

Pumice aggregates intended for use in concrete mixtures with polyester coating were separated into grain sizes of 4–8 and 8–16 mm and dried at 100°C for 24 h prior to the polyester coating process. The coating process was carried out using a spray method with a compressor generating 6–8 bar of air pressure and a top-feed spray gun equipped with nozzle diameters ranging from 0.8 to 2.8 mm. Plastic containers with a diameter of 40 cm and a depth of 25 cm were used during the coating process. Due to the dense consistency of the polyester, it was diluted with cellulosic thinner at a ratio of 6% by weight to facilitate spraying. The pumice aggregates were coated with polyester in three layers to ensure full surface coverage. The reason for applying three layers of polyester was to minimize water permeability through the aggregate surface. The coated aggregates were subsequently dried at 23 ± 2°C for an average of 96 h. Following these procedures, it is estimated that the coating material on the surface of the pumice aggregates consisted of approximately 80% polyester and 20% marble dust. Polyester-coated and non-coated pumice aggregates are shown in Figure 1.

Non-coated and polyester-coated pumice aggregates.

2.3 Lightweight concrete mixture proportions

A series of lightweight concrete mixtures with a cement content of 450 kg/m³ was designed using both polyester-coated and non-coated pumice aggregates. The formulation of the lightweight concrete mixtures adhered to the rules specified in the TS 2511 standard [26]. In the mix design, sand with a particle size ranging from 0 to 4 mm constituted 50% of the total aggregate volume, while aggregates with particle sizes of 4–8 and 8–16 mm accounted for 30 and 20%, respectively. The coated pumice aggregates replaced the non-coated pumice aggregates at volumetric replacement ratios of 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%. In the labeling of the concrete series, the series in which all the pumice aggregates were non-coated was designated as REF (reference), while the other series were named according to the percentage of coated pumice (PC) in the mix.

For each concrete series, 18 cube specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were produced for various tests, including 6 specimens for compressive strength tests (28–90 days), 3 specimens for UPV tests, 6 specimens for freeze–thaw tests, and 3 specimens for water absorption and unit weight tests. Additionally, a total of 15 prismatic specimens with dimensions of 300 × 300 × 30 mm were produced to determine the thermal conductivity coefficient. Detailed proportions of the lightweight concrete mixtures are provided in Table 3.

Lightweight concrete mixture proportions (kg/m3)

| Series | Aggregates sieve aperture (mm) | Cement | Water | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crushed sand | Pumice | ||||||

| 0–4 | 4–8 mm | 8–16 mm | |||||

| Coated | Non-coated | Coated | Non-coated | ||||

| REF | 834.5 | 0 | 175.7 | 0 | 114.6 | 450 | 225 |

| PC-25 | 834.5 | 63.8 | 131.8 | 37.2 | 86.0 | 450 | 225 |

| PC-50 | 834.5 | 127.5 | 87.9 | 74.3 | 57.3 | 450 | 225 |

| PC-75 | 834.5 | 191.3 | 43.9 | 111.5 | 28.7 | 450 | 225 |

| PC-100 | 834.5 | 255.1 | 0 | 148.6 | 0 | 450 | 225 |

In the study. the preliminary water absorption rates of pumice aggregates were not factored in the mix calculation. Consequently, all mixtures were formulated with a consistent water volume. Nonetheless, the obtained results were scrutinized considering this particular aspect.

2.4 Methods

Specific gravity and water absorption tests for coated and non-coated aggregates were conducted in accordance with the TS EN 1097-6 standard [27]. To evaluate the workability of fresh concrete, a slump test was performed following the procedures outlined in the TS EN 12350-2 standard [28], while a unit weight test was carried out in compliance with the guidelines specified in the TS EN 12350-6 standard [29].

In the study, hardened concrete tests involved determining the dry unit weight and water absorption rates following the conditions outlined in the TS EN 12390-7 standard [30]. Compressive strengths were specified according to the TS EN 12390-3 standard [31] utilizing 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm cube specimens. UPV measurements were carried out in accordance with the ASTM C 597 standard [32]. In the freeze–thaw test, the concrete specimens were placed in a freeze–thaw device for 50 and 100 cycles of freeze–thaw cycles after 28 days of water curing. Each freeze–thaw cycle was performed in such a way that the freeze–thaw device completed one cycle between +20 and −20°C in 6 h. The compressive strengths of the specimens were determined after the freeze–thaw cycle.

The thermal conductivity coefficients of the concrete specimens were determined in accordance with the ASTM C518 standard [33]. In the experimental study, a LINSEIS HFM300 thermal conductivity testing device was utilized. The device was configured with the hot plate set to 30°C and the cold plate set to 10°C, ensuring heat flow through the concrete specimens placed between the plates without any gaps. All concrete series were subjected to testing for a fixed duration of 60 min, and their thermal conductivity coefficients were measured.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Aggregate tests results

The specific gravities of aggregates, determined based on the volumetric displacement of water, and the water absorption ratios calculated relative to the oven-dry weights of the aggregates are presented in Table 4. It was observed that the specific gravities of the aggregates ranged between 0.91 and 1.35 g/cm³. The specific gravities of pumice aggregates increased with the coating process; however, they remained below the maximum specific gravity value for lightweight aggregates reported in the literature (2.1 g/cm³).

Specific weight and water absorption rates of pumice aggregates

| Aggregates | Sand | Pumice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-coated | Coated | ||||

| 0–4 mm | 4–8 mm | 8–16 mm | 4–8 mm | 8–16 mm | |

| Specific weight (g/cm3) | 2.65 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1.35 | 1.18 |

| Water absorption (%) | 1.60 | 29.30 | 32.10 | 4.40 | 4.80 |

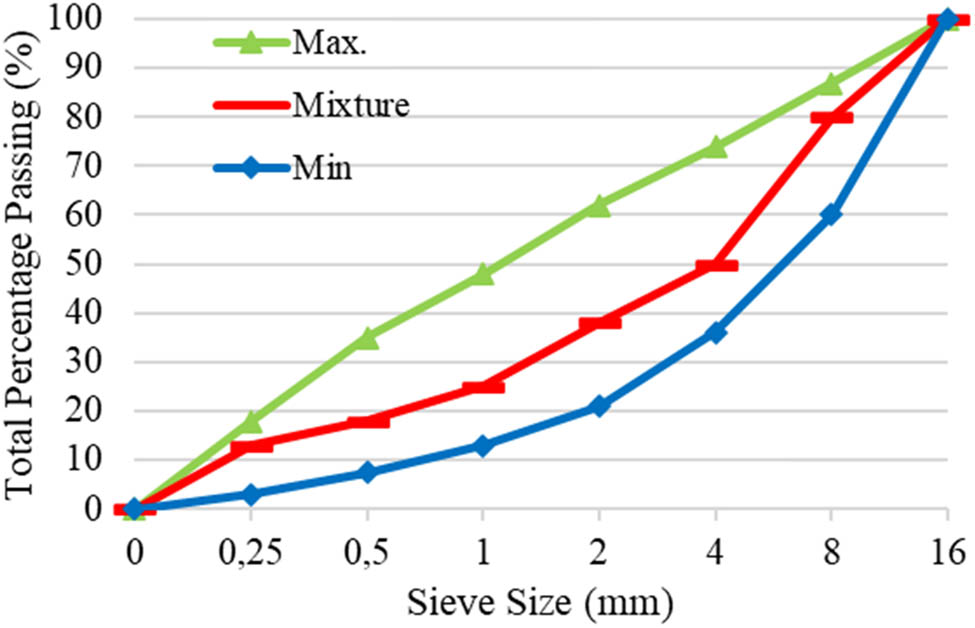

Previous studies have reported that pumice aggregates typically exhibit water absorption ratios ranging between 30 and 40%, which can be reduced to 2–10% through various polymer coatings [20]. For non-coated pumice aggregates with a particle size of 4–8 mm, the water absorption ratio was found to be 29.3%, whereas polyester-coated pumice aggregates of the same particle size exhibited a water absorption ratio of 4.4%. Similarly, for pumice aggregates with a particle size of 8–16 mm, the water absorption ratio of non-coated aggregates was 32.1%, while that of polyester-coated aggregates was 4.8%. Remarkably, the water absorption ratio of pumice aggregates decreased by a factor of 5–6 following the polyester coating process. This observation highlights the potential of polyester coating applications to enhance the durability properties of pumice by reducing its water absorption capacity. Additionally, the granulometry curve determined in accordance with the TS 706 EN 12620 standard [34] is shown in Figure 2.

Granulometry curve of aggregates.

3.2 Concrete tests results

The unit weight values of fresh concrete samples and the results of the slump test conducted to evaluate the workability of fresh concrete are presented in Table 5. The unit weights of the fresh concrete samples ranged between 1,766 and 1,907 kg/m³. The lowest unit weight value of 1,766 kg/m³ was recorded for the REF series, in which all pumice aggregates remained non-coated. Comparatively, an increase in the use of polyester-coated pumice aggregates in the other concrete series resulted in higher unit weight values.

Unit weight and slump values of fresh concretes

| Series | Unit weight (kg/m3) | Slump values (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| REF | 1,766 | 11 |

| PC-25 | 1,829 | 19 |

| PC-50 | 1,847 | 32 |

| PC-75 | 1,871 | 70 |

| PC-100 | 1,907 | 114 |

The slump values of the fresh concrete samples varied between 11 and 114 mm. It was observed that workability improved with the increasing percentage of polyester-coated aggregates in the concrete mixtures. This improvement can be attributed to the higher water absorption rates of non-coated pumice aggregates compared to the lower water absorption rates of polyester-coated pumice aggregates. Since equal amounts of water were used in all concrete mixtures, regardless of the water absorption characteristics of the aggregates, the non-coated aggregates absorbed part of the mixing water, thereby negatively affecting the workability of the concrete.

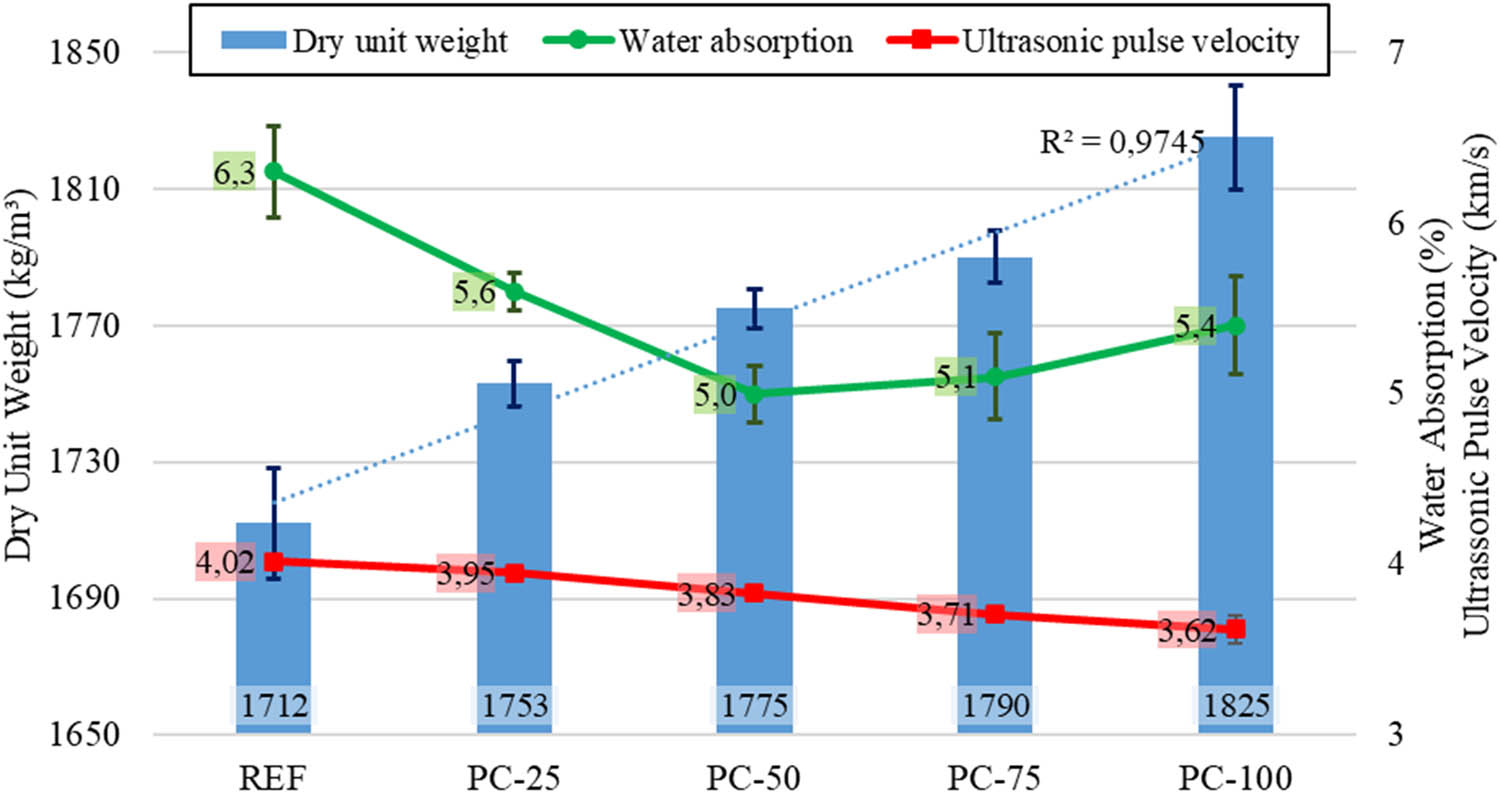

Dry unit weight, water absorption, and UPV values of the lightweight concrete series are given in Figure 3. It has been observed that the PC-100 series specimens exhibit the highest unit weight, measuring at 1825.5 kg/m³. Within the concrete series, it was noted that the dry unit weight values correlate directly with the proportion of coated pumice aggregate present in the concrete. As the percentage of coated pumice aggregate increases, so does the unit weight of the concrete. The dry unit weights of the PC-25 series, PC-50 series, PC-75 series, and PC-100 series increased by 2.4, 3.7, 4.6, and 6.6%, respectively, compared to the samples from the REF series.

Dry unit weights and water absorption rates – UPV of the samples.

The analysis of water absorption rates in the concrete series revealed values ranging from 5.0 to 6.3%, with the REF series exhibiting the highest water absorption rate at 6.3% and the PC-50 series demonstrating the lowest rate at 5.0%. It was observed that all concrete series containing polyester-coated pumice aggregates exhibited lower water absorption rates compared to the control series without polyester-coated pumice. This indicates that the polyester coating process reduces water absorption not only in the aggregates but also in the resulting concrete. However, a linear reduction in water absorption rates was not observed with the increasing content of polyester-coated aggregates in the concrete series. This is thought to be due to non-coated aggregates partially absorbing mixing water and thereby altering the effective water-to-binder ratio. Furthermore, the literature suggests that indirectly altered water-to-binder ratios in concrete mixtures can influence permeability properties [35]. Despite these findings, the water absorption rates determined in this study align with the ranges reported in the literature for lightweight concrete, which typically range from 6 to 12% [36,37]. Additionally, the results meet the requirements suggested by Neville and Aitcin [38,39], which propose a maximum water absorption rate of up to 10% for high-durability lightweight concretes.

The measurement of UPV, based on the propagation speed of an ultrasonic wave pulse generated at the surface of concrete, is a non-destructive testing method aimed at assessing the homogeneity of concrete material and identifying structural defects such as cracks. This method is widely employed in the evaluation of the physical and mechanical properties of concrete, providing critical insights into parameters such as elastic modulus, density, and compressive strength [40,41,42]. The UPV test is particularly effective for detecting irregularities and heterogeneities within the internal structure of concrete. The velocity of sound waves traveling through the material is a direct indicator of internal cracks, voids, or other structural imperfections. Higher pulse velocities indicate a homogeneous and dense material structure, whereas lower velocities suggest the presence of defects and voids within the concrete [43].

Data obtained from UPV measurements indicate that the ultrasonic pulse velocities of the concrete series range between 3.62 and 4.02 km/s. The highest UPV was observed in the REF series specimens produced with non-coated aggregates. It was determined that ultrasonic pulse velocities decreased as the percentage of coated aggregates in the mixture increased. Compared to the REF-labeled control series, the ultrasonic pulse velocities of the PC-25, PC-50, PC-75, and PC-100 series specimens decreased by 2, 5, 8, and 10%, respectively. The literature reports that concrete produced with aggregates having smoother surfaces exhibit higher UPV values [44]. The smoother surface of polyester-coated aggregates compared to non-coated aggregates supports these UPV values. Moreover, it is hypothesized that the partial absorption of mixing water by non-coated aggregates and the higher effective water-to-binder ratio in concrete series produced with polyester-coated aggregates are the primary factors contributing to this phenomenon.

An inverse relationship was observed between the dry unit weights of the concrete series and their ultrasonic pulse velocities. This can be explained by the fact that although coated aggregates possess a higher specific gravity, their relatively smoother surface characteristics and the higher effective water-to-binder ratios in the mixtures significantly influence this relationship.

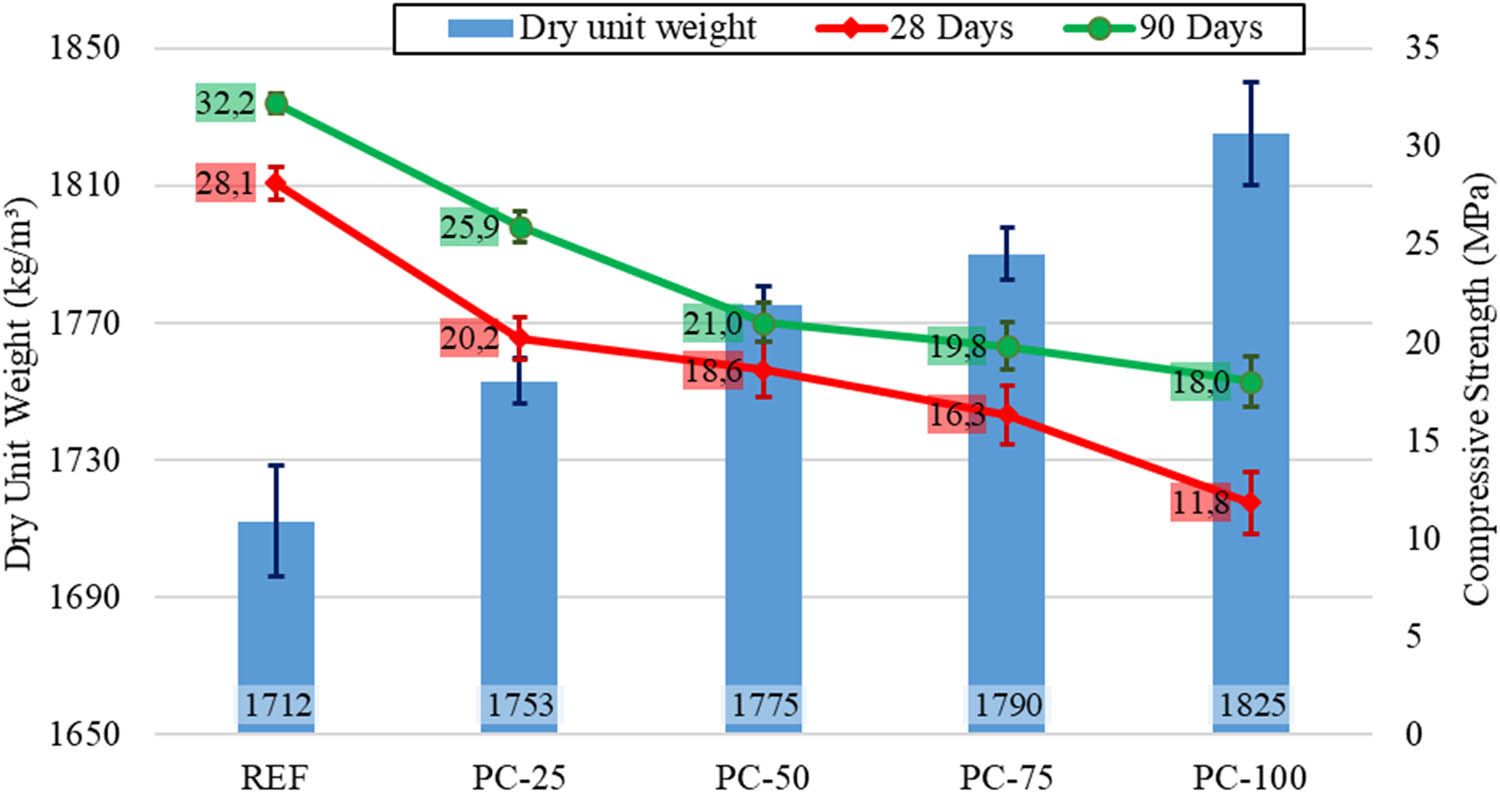

The 28- and 90-day compressive strength test results, along with the dry unit weights of the concrete series, are presented in Figure 4. An analysis of Figure 4 reveals that the REF series specimens exhibited the highest compressive strength of 28.1 MPa after 28 days, while the PC-100 series specimens showed the lowest value of 11.8 MPa. A reduction in compressive strength was observed with the increasing proportion of polyester-coated pumice aggregates in the concrete series. This decrease in compressive strength is attributed to two main factors: the partial absorption of mixing water by non-coated aggregates, which alters the effective water-to-binder ratio, and the smoother surface morphology of polyester-coated pumice aggregates compared to non-coated aggregates, leading to reduced adhesion at the cement–aggregate interface. Concrete produced with coarser aggregates featuring rougher surfaces typically exhibits enhanced interfacial bond strength and improved mechanical performance [45,46,47]. Compared to the REF series, the compressive strengths of the PC-25, PC-50, PC-75, and PC-100 series specimens were reduced by 28, 34, 43, and 58%, respectively. Regarding the 90-day compressive strength results, the highest value was obtained in the REF series specimens at 32.2 MPa, while the lowest value was observed in the PC-100 series specimens at 18 MPa. When compared to the REF series, the compressive strengths of the PC-25, PC-50, PC-75, and PC-100 series specimens decreased by 20, 35, 39, and 44%, respectively.

Dry unit weights and compressive strength (28–90 days) of the samples.

A comparison of compressive strengths over 28- and 90-day periods revealed that all concrete series exhibited an increase in compressive strength at 90 days. Among these, the PC-100 series specimens demonstrated the most significant increase, with an impressive 52% increase in compressive strength compared to their 28-day results. This was followed by the PC-25 series with a 28% increase, the PC-75 series with a 22% increase, the REF series with a 15% increase, and the PC-50 series with a 13% increase. These results suggest that the use of polyester-coated aggregates may delay the process of achieving ultimate strength. Furthermore, the lower strength gain observed in the PC-50 series compared to the REF series has been attributed to the heterogeneous nature of the concrete.

According to TS EN 206 + A2 standard [48], the compressive strength of lightweight concretes can be in the range of 9–88 MPa for 28-day cube specimens and 8–80 MPa for 28-day cylinder specimens. When the experimental results are examined, it is seen that the compressive strength values for 28-day concrete specimens are between 28.1 and 11.8 MPa. Considering this situation, it was determined that the concrete series produced conformed to the standard, and the compressive strength classes were LC 25/28 in the REF series, LC 16/18 in PC-25 and PC-50 series, LC 12/13 in the PC-75 series and LC 8/9 in PC-100 series. Among the concrete series, it was determined that the 28-day compressive strengths of the REF, PC-25, and PC-50 series specimens fulfill the condition of being a structural lightweight concrete stated as 17 MPa in the literature, while the 28-day compressive strengths of the PC-75 and PC-100 series specimens do not fulfill this condition [49]. However, when the 90-day compressive strengths of the concrete specimens were analyzed, it was observed that all concrete series had compressive strengths over 17 MPa.

In general, there is a positive correlation between concrete unit weight and compressive strength [50,51,52,53]. However, in the present study, the opposite trend was observed. This phenomenon is attributed to the fact that, although coated aggregates possess a higher specific gravity, their altered surface characteristics and indirect influence on the properties of the concrete mixture contribute to this deviation.

The compressive strengths of the specimens after 50 and 100 cycles of freeze–thaw cycles are given in Figure 5. It is known that negative environmental conditions such as freeze–thaw adversely affect the durability properties of concrete, cause deterioration in concrete and reduce concrete performance [53,54,55]. The concrete specimens produced within the scope of the study were subjected to two different freeze–thaw cycles, 50 and 100 cycles, to determine their resistance to freeze–thaw effects. No rupture or mass loss was observed in the concrete specimens after freeze-thaw cycles. The compressive strengths of the concrete specimens exposed to freeze–thaw cycles were determined.

Compressive strength of samples before and after freezing and thawing.

Specimens from the REF (29.1 MPa) series exhibited the highest compressive strength following 50 cycles of freezing and thawing, while those from the PC-100 (12.5 MPa) series displayed the lowest compressive strength. An analysis of the compressive strengths of specimens after 50 cycles of freezing and thawing revealed that, compared to the 28-day compressive strengths, certain specimens exhibited an increase in compressive strength while others experienced a decrease. After 50 cycles, compressive strengths increased by 3.4% in REF specimens, increased by 4.6% in PC-25 specimens, decreased by 3.9% in PC-50 specimens, unchanged in PC-75 specimens, and increased by 5.8% in PC-100 specimens. Since these changes in compressive strengths are very small, it is assumed that this situation is related to the heterogeneous structure of concrete rather than freeze–thaw cycles.

Comparing the 28-day compressive strengths of the concrete specimens with the compressive strengths after 100 cycles of freezing and thawing, it was found that REF series specimens increased by 1.9%, PC-25 series specimens increased by 19.7%, PC-50 series specimens decreased by 2.8%, PC-75 series specimens decreased by 8.6%, and PC-100 series specimens decreased by 8.9%. Based on 100 cycles of freeze–thaw cycles, the compressive strengths of all series except the PC-25 series decreased among the concrete series containing polyester-coated aggregates. The increase observed in the PC-25 series is thought to be associated with the heterogeneous nature of the concrete. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5, the high standard deviation of the corresponding data supports this observation. Researchers have indicated that the freeze and thaw resistance of concrete can be increased by the use of lightweight aggregates in certain proportions in concrete. In addition, they stated that the increase in compressive strength after the freeze–thaw cycle could be attributed to the escape of excess water into the pores in the lightweight aggregates during the freezing event [56,57]. Polyester coating reduced the water absorption rate of aggregates. Therefore, the possibility of water infiltration into the aggregate voids was largely eliminated. Considering this situation, it is seen that the compressive strengths of the PC-50, PC-75, and PC-100 concrete series decreased by 2.8, 8.6, and 8.9%, respectively, after 100 cycles of freeze–thaw.

The thermal conductivity of aggregates depends on their porosity and mineralogical composition. In their study, Holm and Bremner reported that the thermal conductivity coefficients of normal-weight concrete with an average unit weight of 2,400 kg/m³ range between 1.4 and 2.9 W/mK, whereas lightweight concretes with an average unit weight of 1,850 kg/m³ have thermal conductivity coefficients ranging from 0.58 to 0.86 W/mK [58]. In a similar study, lightweight concretes with unit weights ranging from 1,440 to 1,890 kg/m³ exhibited thermal conductivity coefficients between 0.70 and 1.36 W/mK, while normal-weight concretes demonstrated higher values. The same study reported that, depending on the properties of the aggregates used, the thermal conductivity coefficients of lightweight concretes were 40 to 53% lower than those of normal-weight concretes [59]. Bideci et al. noted that the thermal conductivity of lightweight concretes produced by replacing polyester-coated pumice and non-coated pumice aggregates at ratios of 0, 50, and 100% ranged between 0.227 and 0.269 W/mK [23].

The thermal conductivity coefficients, unit weights, and compressive strengths of the lightweight concrete series are presented in Figure 6. An evaluation of the thermal conductivity measurement data indicates that the coefficients range between 0.246 and 0.300 W/mK. The lowest thermal conductivity coefficient, 0.246 W/mK, was observed in the PC-25 series, while the highest value, 0.300 W/mK, was recorded in the PC-100 series. Compared to the reference series, the thermal conductivity coefficients of the specimens decreased by 11 and 2% in the PC-25 and PC-50 series, respectively. In contrast, an increase of 7 and 9% was observed in the PC-75 and PC-100 series, respectively.

Thermal conductivity and compressive strengths of the samples.

When examining all concrete series, no linear relationship is observed among the thermal conductivity results. The higher thermal conductivity coefficient of the REF series compared to the PC-25 series has been associated with the significant influence of the heterogeneous nature of concrete on its thermal conductivity properties. However, among the concrete specimens containing polyester-coated pumice aggregates, an increase in thermal conductivity was observed with the increasing proportion of polyester-coated pumice. This indicates that as the unit weight of concrete increases, the thermal conductivity coefficient also increases. Under normal conditions, in lightweight aggregate concrete, the thermal conductivity coefficient is predominantly influenced by concrete density and moisture content, while the effects of aggregate type, concrete grade, and cement content are much more limited [60]. Numerous studies in the past have reported a relationship between thermal conductivity and density, with higher thermal conductivity coefficients corresponding to increased density. Additionally, it has been reported that concretes with higher porosity exhibit lower thermal conductivity coefficients [61,62]. These findings are consistent with the data obtained from the present study.

4 Conclusions

The results of the experiments conducted on lightweight concrete produced with polyester-coated and non-coated pumice aggregates are presented.

It was determined that the specific gravity of pumice aggregates increased as a result of the polyester coating process, while their water absorption rates decreased by nearly 85%.

Despite the water-to-binder ratio remaining constant across all concrete series, the slump values of the fresh concrete specimens varied between 11 and 114 mm, and the unit weights of the fresh concrete ranged from 1,765 to 1,907 kg/m³.

The dry unit weights of the lightweight concrete produced were found to range between 1,712 and 1,826 kg/m³, while their water absorption rates were within the range of 5–6%. It was observed that the concrete series containing polyester-coated aggregates exhibited higher unit weights but lower water absorption rates compared to the reference series.

The 28- and 90-day compressive strengths of the concrete specimens ranged from 11.8 to 28.1 MPa and from 18 to 32.2 MPa, respectively. Concrete containing polyester-coated pumice exhibited a slower development of ultimate compressive strength. The ultrasonic pulse velocities of the concrete specimens were measured to be between 3.62 and 4.02 km/s. A reduction in both compressive strength and UPV was observed with the use of polyester-coated pumice.

According to the compressive strength data following freeze–thaw cycles, a maximum change of 5% was observed in strength values after 50 cycles. However, after 100 cycles, the high utilization of polyester-coated aggregates had a negative impact on freeze-thaw resistance.

The thermal conductivity coefficients of the concrete specimens were determined to range between 0.246 and 0.300 W/mK. A linear relationship was identified between the unit weight and thermal conductivity for concrete specimens containing polyester-coated aggregates, except for the REF series.

The study concluded that the produced concretes can be utilized as lightweight concrete materials for non-load-bearing walls and as an alternative to lightweight insulation materials. To further evaluate the applicability of polymer-coated pumice aggregates in concrete production, future studies could focus on enhancing mechanical strength properties and determining durability characteristics in greater detail.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. MT: methodology, resources, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing. AB: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing. OSB: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, and visualization. BÇ: conceptualization, methodology, and visualization. GD: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and investigation.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

[1] Alexander M, Bentur A, Mindess S. Durability of Concrete. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2017.10.1201/9781315118413Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yazıcıoğlu S, Bozkurt N. The investigation of the mechanical properties of structural lightweight concrete produced with pumice and mineral admixtures. J Fac Eng Archit Gazi Univ. 2006;21:675–80.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yasar E, Atis CD, Kilic A, Gulsen H. Strength properties of lightweight concrete made with basaltic pumice and fly ash. Mater Lett. 2003;57:2267–70.10.1016/S0167-577X(03)00146-0Search in Google Scholar

[4] Muralitharan RS, Ramasamy V. Development of lightweight concrete for structural applications. J Struct Eng. 2017;44:1–5.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Asadi I, Shafigh P, Abu H, Bin ZF. Mahyuddin NB. Thermal conductivity of concrete – A review. J Build Eng. 2018;20:81–93.10.1016/j.jobe.2018.07.002Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sifan M, Nagaratnam B, Thamboo J, Poologanathan K, Corradi M. Development and prospectives of lightweight high strength concrete using lightweight aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2023;362:129628.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129628Search in Google Scholar

[7] Short A, Kinniburgh W. Lightweight concrete. 3rd edn. London: Applied Science Publishers; 1978.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Türkel S, Kadiroğlu B. Investıgatıon on mechanical properties of structural lightweight concrete made with pumice aggregate. Pamukkale Unıv Eng Fac J Eng Sci. 2007;13:353–9.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Anwar Hossain KM. Properties of volcanic pumice based cement and lightweight concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2004;34:283–91.10.1016/j.cemconres.2003.08.004Search in Google Scholar

[10] Dinçer İ, Orhan A, Çoban S. Pomza araştirma ve uygulama merkezi fizibilite raporu. Nevşehir: Ahiler Kalkınma Ajansı; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kılıç A, Atiş CD, Yaşar E, Özcan F. High-strength lightweight concrete made with scoria aggregate containing mineral admixtures. Cem Concr Res. 2003;33:1595–9.10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00131-5Search in Google Scholar

[12] Sancak E, Dursun Sari Y, Simsek O. Effects of elevated temperature on compressive strength and weight loss of the light-weight concrete with silica fume and superplasticizer. Cem Concr Compos. 2008;30:715–21.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[13] Karthika RB, Vidyapriya V, Nandhini Sri KV, Merlin Grace Beaula K, Harini R, Sriram M. Experimental study on lightweight concrete using pumice aggregate. Mater Today Proc. 2021;43:1606–13.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.762Search in Google Scholar

[14] Hossain KMA, Ahmed S, Lachemi M. Lightweight concrete incorporating pumice based blended cement and aggregate: mechanical and durability characteristics. Constr Build Mater. 2011;25:1186–95.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.09.036Search in Google Scholar

[15] Türkmen İ, Demirboğa R, Gül R. The effects of different cement dosages, slumps and pumice aggregate ratios on the freezing and thawing of concrete. Comput Concr. 2006;3:163–75.10.12989/cac.2006.3.2_3.163Search in Google Scholar

[16] Öz HÖ, Yücel HE, Güneş M. Freeze-thaw resistance of self compacting concrete incorporating basic pumice. Int J Theor Appl Mech. 2016;1:285–91.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Uysal H, Demirboğa R, Şahin R, Gül R. The effects of different cement dosages, slumps, and pumice aggregate ratios on the thermal conductivity and density of concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2004;34:845–8.10.1016/j.cemconres.2003.09.018Search in Google Scholar

[18] Lynda Amel C, Kadri E-H, Sebaibi Y, Soualhi H. Dune sand and pumice impact on mechanical and thermal lightweight concrete properties. Constr Build Mater. 2017;133:209–18.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.043Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lv XJ, Cao ML, Li Y, Li Y. Experimental study on the pumice aggregate concrete. Mater Sci Forum. 2013;743–744:329–3.10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.743-744.329Search in Google Scholar

[20] Salli Bideci Ö, Bideci A, Gültekin AH, Oymael S, Yildirim H. Polymer coated pumice aggregates and their properties. Compos B Eng. 2014;67:239–43.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[21] Vahabi MY, Tahmouresi B, Mosavi H, Fakhretaha Aval S. Effect of pre‐coating lightweight aggregates on the self‐compacting concrete. Struct Concr. 2022;23:2120–31.10.1002/suco.202000744Search in Google Scholar

[22] Özgüler AT, Göncüoğlu T, Emiroğlu M. Investigation of impact value and water absorption performance on pumice aggregates coated with cement paste. Int J Pure Appl Sci. 2023;9:157–64.10.29132/ijpas.1248073Search in Google Scholar

[23] Bideci A, Bideci ÖS, Ashour A. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight concrete produced with polyester-coated pumice aggregate. Constr Build Mater. 2023;394:132204.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132204Search in Google Scholar

[24] TS EN 197-1. Cement - Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Poliya. Polipol 3455 Technical Data Sheet. n.d.Search in Google Scholar

[26] TS 2511. Mix design for structural lightweight aggregate concrete. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[27] TS EN 1097-6. Tests for mechanical and physical properties of aggregates - Part 6: Determination of particle density and water absorption. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[28] TS EN 12350-2. Testing fresh concrete - Part 2: Slump test. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[29] TS EN 12350-6. Testing fresh concrete - Part 6: Density. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[30] TS EN 12390-7. Testing hardened concrete - Part 7: Density of hardened concrete. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[31] TS EN 12390-3. Testing hardened concrete - Part 3: Compressive strength of test specimens. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[32] ASTM C597. Standard test method for ultrasonic pulse velocity through concrete. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[33] ASTM C518. Standard test method for steady-state thermal transmission properties by means of the heat flow meter apparatus. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[34] TS 706 EN 12620 + A1. Aggreg Concr. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Aïtcin P-C. The importance of the water–cement and water–binder ratios. Science and technology of concrete admixtures. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2016. p. 3–13.10.1016/B978-0-08-100693-1.00001-1Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ali MR, Maslehuddin M, Shameem M, Barry MS. Thermal-resistant lightweight concrete with polyethylene beads as coarse aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2018;164:739–49.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[37] Bajare D, Kazjonovs J, Korjakins A. Lightweight concrete with aggregates made by using industrial waste. J Sustainable Archit Civ Eng. 2013;4:1–7.10.5755/j01.sace.4.5.4188Search in Google Scholar

[38] Neville AM. Properties-of-concrete. 4th edn. London: Longman; 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Aïtcin P-C. High performance concrete. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1998.10.4324/9780203475034Search in Google Scholar

[40] Malhotra VM, Carino NJ. Handbook on nondestructive testing of concrete. 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003.10.1201/9781420040050Search in Google Scholar

[41] Kurt M, Gül MS, Gül R, Aydin AC, Kotan T. The effect of pumice powder on the self-compactability of pumice aggregate lightweight concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2016;103:36–46.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.11.043Search in Google Scholar

[42] Solís-Carcaño R, Moreno EI. Evaluation of concrete made with crushed limestone aggregate based on ultrasonic pulse velocity. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22:1225–31.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.01.014Search in Google Scholar

[43] Saint-Pierre F, Philibert A, Giroux B, Rivard P. Concrete quality designation based on ultrasonic pulse velocity. Constr Build Mater. 2016;125:1022–7.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.158Search in Google Scholar

[44] Güçlüer K. Investigation of the effects of aggregate textural properties on compressive strength (CS) and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) of concrete. J Build Eng. 2020;27:100949.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100949Search in Google Scholar

[45] Hong L, Gu X, Lin F. Influence of aggregate surface roughness on mechanical properties of interface and concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2014;65:338–49.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.131Search in Google Scholar

[46] Hong L, Gu X-L, Lin F, Gao P, Sun L-Z. Effects of coarse aggregate form, angularity, and surface texture on concrete mechanical performance. J Mater Civ Eng. 2019;31:1–13.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002849Search in Google Scholar

[47] Hilal AA. Effect of aggregate roughness on strength and permeation characteristics of lightweight aggregate concrete. J Eng. 2021;2021:1–8.10.1155/2021/9505625Search in Google Scholar

[48] TS EN 206 + A2. Concrete - specification, performance, production and conformity. Ankara, Turkey: Türk Stand. Ins; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[49] ACI 213R-87. Guide for structural lightweight-aggregate concrete. Farmington Hills, MI, USA: American Concrete Institute; 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Newman J, Choo BS. Advanced concrete technology. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Elango KS, Sanfeer J, Gopi R, Shalini A, Saravanakumar R, Prabhu L. Properties of light weight concrete – A state of the art review. Mater Today Proc. 2021;46:4059–62.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.571Search in Google Scholar

[52] Fořt J, Afolayan A, Medveď I, Scheinherrová L, Černý R. A review of the role of lightweight aggregates in the development of mechanical strength of concrete. J Build Eng. 2024;89:109312.10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109312Search in Google Scholar

[53] Tanyıldızı M, Gökalp İ. Utilization of pumice as aggregate in the concrete: A state of art. Constr Build Mater. 2023;377:131102.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131102Search in Google Scholar

[54] Rustamov S, Woo Kim S, Kwon M, Kim J. Mechanical behavior of fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete subjected to repeated freezing and thawing. Constr Build Mater. 2021;273:121710.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121710Search in Google Scholar

[55] Sun W, Zhang YM, Yan HD, Mu R. Damage and damage resistance of high strength concrete under the action of load and freeze-thaw cycles. Cem Concr Res. 1999;29:1519–23.10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00097-6Search in Google Scholar

[56] Kabay N, Kizilkanat AB, Tüfekçi MM. Effect of prewetted pumice aggregate addition on concrete properties under different curing conditions. Period Polytechn Civ Eng. 2016;60:89–95.10.3311/PPci.7767Search in Google Scholar

[57] Polat R, Demirboǧa R, Karakoç MB, Türkmen I. The influence of lightweight aggregate on the physico-mechanical properties of concrete exposed to freeze–thaw cycles. Cold Reg Sci Technol. 2010;60:51–6.10.1016/j.coldregions.2009.08.010Search in Google Scholar

[58] Holm TA, Bremner. TW. State-of-the-art report on high-strength. High-durability structural low-density concrete for applications in severe marine environments. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Real S, Bogas JA, Gomes M, da G, Ferrer B. Thermal conductivity of structural lightweight aggregate concrete. Mag Concr Res. 2016;68:798–808.10.1680/jmacr.15.00424Search in Google Scholar

[60] Khushefati WH, Demirboğa R, Farhan KZ. Assessment of factors impacting thermal conductivity of cementitious composites—A review. Clean Mater. 2022;5:100127.10.1016/j.clema.2022.100127Search in Google Scholar

[61] Mahpour AR, Sadrolodabaee P, Ardanuy M, Haurie L, Lacasta AM, Rosell JR, et al. Serviceability parameters and social sustainability assessment of flax fabric reinforced lime-based drywall interior panels. J Build Eng. 2023;76:107406.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107406Search in Google Scholar

[62] Sadrolodabaee P, Hosseini SMA, Claramunt J, Ardanuy M, Haurie L, Lacasta AM, et al. Experimental characterization of comfort performance parameters and multi-criteria sustainability assessment of recycled textile-reinforced cement facade cladding. J Clean Prod. 2022;356:131900.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131900Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)