Abstract

Recent years have witnessed a considerable increase in the production of novel types of nanomaterials and nanomaterial-modified matrices and surfaces. This article highlights the latest achievements (predominantly over the past 5 years) in the properties and manufacturing methods of nanostructured composites, with a particular focus on carbon and ceramic materials. The key parameters determining the effectiveness of nanofillers for reducing brittleness and increasing corrosion resistance, including that at high temperatures, in ceramic composites are discussed. Interphase effects play a decisive role in shaping the properties of nanocomposites. Research into the relationship between the structure of composites, particularly those based on ceramic materials as a matrix, and the addition of carbon nanotubes, is promising. Thus, it has been shown that carbon nanomaterials significantly reduce the brittleness of ceramic and carbon composites, increasing their strength and durability.

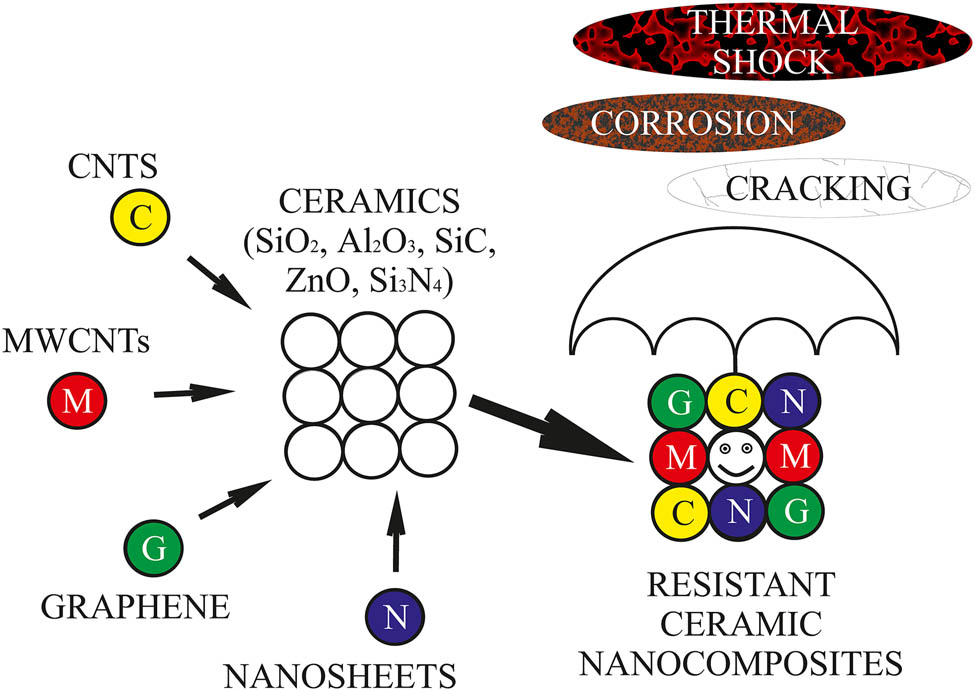

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology studies the fundamental properties of substances that are smaller than 100 nm in at least one of three dimensions; this field of science is related to physics, biology, and chemistry. The upper limit of the size of nanomaterials or nanosystems is the point beyond which further increase does not lead to a change in properties. Morphologically, nanomaterials can be films, rods (tubes, wires), quantum dots, etc. Nanoscale dimensions cause changes in the physical and chemical properties (electrical conductivity, magnetism, ability to absorb and emit light, optical refraction, thermal stability, strength) of materials and lead to catalytic activity or reactivity that are not observed in macro- and microscopic bodies of the same chemical nature [1,2]. From a qualitative point of view, the special properties of nanomaterials are associated with both the unusually developed surface of the particles and the electronic and quantum effects inherent in these nanoparticles.

Various nanoscale materials are used as fillers to improve the properties of polymer (thermoplastic, elastomeric), ceramic or metal matrices [3,4,5]. The reason for preferring nanofillers to macrofillers is that nanofillers not only improve the desired mechanical properties of composites, but also improve their functional properties, such as self-lubricating surfaces [6]. Composites consist of two phases: matrix and reinforcement. It has been demonstrated that the introduction of nanofillers in various ratios improves the structural or functional properties of matrices, such as mechanical, thermal, electrical, electrochemical, and others [4,7,8]. In this case, nanoparticles are used as connecting links between molecular structures in bulk materials [9]. A particularly important aspect is the use of solid micro- and nanofillers as compatibility enhancers or to increase the strength and flexibility of matrices when only a limited amount of filler can be used.

Obtaining new types of materials with advanced performance characteristics is important for the development of the aviation industry, energy, construction, and biomedical technologies [10–13]. Numerous studies have shown improvements in the mechanical properties of composite materials through the introduction of different forms of carbon materials [14–19] (Table 1).

Comparison of mechanical properties of composite materials

| Materials | Experimental technique | Young’s modulus | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolayer graphene | Nano-indentation in AFM | 1 TPa | 15 |

| Chemically rGO sheet | An AFM tip-induced deformation | 250 GPa | 16 |

| Monolayer GO | AFM imaging contact mode | 207 GPa | 17 |

| Free standing GO | Nano-indentation on a dynamic contact tool | 697 ± 15 GPa | 18 |

| Graphene paper | — | 31.7 GPa | 19 |

| Graphene fiber (hybrid of graphene ribbons and sheets) | Tensile tester at a strain rate of 1 mm min─1 with a gauge length of 5 mm | — | 20 |

However, this area remains insufficiently studied. The main problems arise from the inherent characteristics of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) as nanofillers, in particular their strong tendency to aggregate and their flexibility, which often leads to pronounced bending of nanotubes during the manufacture of polymer nanocomposites [20]. A similar effect is also known for composites containing metal wires, where it has a significant impact on the properties of the material [20]. The effectiveness of mechanical reinforcement of ceramic composites with carbon allotropes remains a subject of debate, due to the heterogeneity of carbon nanomaterial dispersion, weak adhesion at the phase boundary between carbon allotropes and ceramic matrix grains, and the location of carbon allotropes at grain boundaries [21,22]. In this regard, the analysis of recent studies presented in this article, which addresses the aforementioned shortcomings, is highly relevant. A large number of literature reviews are devoted to polymer and/or metal matrices reinforced with carbon nanomaterials, and there are not enough publications on changing the properties of ceramic matrices using CNT.

Since composite manufacturing is an important area of materials science and mechanical engineering, it is relevant to analyze the various components of matrices and fillers. For example, Al–Si alloy is widely used in mechanical engineering to manufacture parts such as pistons and cylinder liners due to its high strength. The size of silicon particles in different areas of the casting system varies significantly, leading to significant variability in the mechanical properties of the sample [23]. Primary silicon crystals can be purified to increase wear resistance and hardness. For example, it has been found that silicon carbide (SiC) particles synthesized in situ play a positive role in increasing hardness, density, wear resistance, and thermal expansion coefficient. In addition, the ultimate tensile strength of a SiC-reinforced alloy can be increased to 132 MPa at a test temperature of 350°C [24]. It has been demonstrated that when the content of SiC nanoparticles is increased from 1 to 10 vol%, the yield strength and tensile strength increase from 296 and 343 MPa to 545 and 603 MPa, respectively [25]. It has been reported that the elastic modulus of a composite reinforced with 10 vol% SiC nanoparticles is 97.1 GPa, which is significantly higher than that of pure aluminum (72.6 GPa) [26]. The strengthening effect of SiC nanoparticles is reduced due to their aggregation in the metal matrix [17]. In addition, fully dense composites (titanium boride [TiB2] + SiC) reinforced with Ti3SiC2 containing 15 vol% TiB2 and 0–15 vol% SiC were obtained by in situ hot pressing. The increase in SiC content contributed to compaction and significantly suppressed the growth of Ti3SiC2 grains. It was found that the maximum flexural strength of such composites is 881 MPa, and the fracture toughness is 9.24 MPa at 1/2 at 10 vol% SiC. The Vickers hardness of the composites increased monotonically from 9.6 to 12.5 GPa [27]. In the work of Li et al. [28], composites made of ZA27 alloy reinforced with Ti3SiC2 were synthesized by hot pressing mechanically alloyed mixtures of Ti3SiC2 and ZA27 powders. It was shown that composites containing 20% Ti3SiC2/ZA27 have the highest tensile strength at room temperature, flexural strength, and Vickers hardness, equal to 339 MPa, 593 MPa, and 1.13 GPa, respectively. The improved mechanical properties of the Ti3SiC2/ZA27 composite are mainly due to the effects of fine-grained and dispersion strengthening [28,29]. Friction stir processing (FSP) was used as a method for producing Al 7075 composites (SCs) doped with three different nanoparticles: multi-walled carbon nanotubes, graphene, and titanium dioxide [30]. All SC samples demonstrated uniform dispersion of filler nanoparticles in their microstructure. The increase in the hardness and strength of the composites was due to grain refinement and the pinning effect, which was accelerated by the circulation of the cooling liquid. The hardness values in SCs increased by approximately 95–110%. The wear rate in SCs also decreased due to the increase in hardness and the formation of a lubricating coating in the case of carbon-containing composites. In addition, scanning electron microscopy demonstrated that three different phases can be distinguished in the composite containing 10% SiC, namely, the white phase Ti3SiC2, the non-white phase TiB2, and the dark phase SiC. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) tomography results were in good agreement with the results of X-ray and electron analyses. The SEM tomography results showed a uniform distribution of both TiB2 and SiC in the composites, with fine grains approximately 1–2 µm in size for SiC and 2–4 µm for TiB2. Increasing the SiC content from 0 to 15 vol% initially led to an increase in the flexural strength of the composites, followed by a decrease. The effect on fracture toughness remained insignificant [26,31].

In addition, various nanofillers are used in matrices to change the interphase interaction of components, in addition to reinforcement and increased wear resistance. For example, hydroxyapatite was synthesized in the form of nanofibers and introduced into a polylactic acid (PLA) matrix [32]. The authors note that, despite poor interphase adhesion between hydroxyapatite nanofiber (HANF) and PLA, the destruction of composites was slowed down due to the binding effect of the fibers. The elastic modulus and tensile strength of PLA/HANF with an HANF content of 5 wt% increased by 38 and 13%, respectively, compared to PLA. An increase in the tensile strength of PLA/HANF compared to PLA resin was observed up to 10 wt% of HANF. Hydroxyapatite fibers were then combined with PLA, which further improved the adhesion to the interface between HANF and the PLA matrix, as well as the dispersion of HANF in the composites.

It should be noted that the choice of matrix is determined by the intended application and performance characteristics of the materials. The materials used are diverse, and this article will cover several important groups, with a particular focus on ceramic and carbon materials.

2 Characteristics of CNTs and approaches to forming CNT-based composites

CNTs are a type of crystalline carbon and, depending on the synthesis method, can have a crystalline, amorphous, or mixed structure. These nanoparticles are widely known for their unique physical and chemical properties and practical applications. The classification of CNT is usually based on the number of carbon layers forming their structure, which is equivalent to the number of walls in the nanotube [33,34].

CNTs have attracted considerable attention since their discovery in the 1990s due to their exceptional tensile strength and electrical conductivity, which make them valuable components in the aerospace, automotive, and computer industries. The morphology of single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs) can be determined using various approaches, including atomic force microscopy (Figure 1).

![Figure 1

Visualization of MWCNT using atomic force microscopy. Reproduced with permission from [35].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2025-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2025-0065_fig_001.jpg)

Visualization of MWCNT using atomic force microscopy. Reproduced with permission from [35].

Arc discharge and laser ablation methods allow the production of SWNTs with a high-quality graphite lattice, but they are energy-intensive and yield a small amount of product. In contrast, chemical vapor deposition and catalytic growth in the gas phase are more economical, although the resulting nanotubes often have an imperfect graphite structure. As a result, chirality and geometric parameters play a decisive role in determining the optical, electrical, and mechanical properties of CNT [36,37]. The prospects for using CNT as a reinforcing component in composites are due to their unique combination of physical and mechanical characteristics, including an abnormally low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), exceptional mechanical strength (tensile strength up to 100 GPa), and high thermal conductivity (up to 3,000 W m−1 K−1) [38].

Experimental studies show that adding just 3 vol% of CNT to an aluminum matrix allows achieving an elastic modulus of 90 GPa and a strength of 600 MPa, which is comparable to the characteristics of traditional Al-SiC composites containing 20–25 vol% silicon carbide [8]. At the same time, optimizing the CNT content to 4.5 mass% leads to an increase in hardness and tensile strength by 2.3 and 2.4 times, respectively, compared to an unreinforced matrix. A critical factor determining the performance characteristics of such composites is the degree and uniformity of dispersion of nanotubes in the metal matrix [4]. Numerous studies confirm that nanotubes effectively suppress the thermal expansion of the matrix material, and the degree of CTE reduction depends on both the volume fraction of the strengthening phase and the spatial orientation of the nanotubes [9]. The greatest effectiveness in terms of thermal expansion control is observed when using oriented structures based on CNT, which is associated with the anisotropy of their physical properties and a more sophisticated mechanism of stress transfer at the phase boundary [39,40]. In addition, dispersion, especially uneven dispersion of CNT in the matrix, plays a decisive role in the mechanical and thermal properties of the composite. A number of studies have shown that CNT reduce the CTE, for example, of aluminum composites [38]. The degree of reduction in the coefficient depends on the content of CNTs and their orientation (with oriented CNTs being more effective [40]. Over the past two decades, several materials have been developed using CNT that can store electrical energy, withstand lightning strikes, detect damage, and have the ability to self-repair [41]. Zhu et al. [42] reported in their work that incorporating SWCNT into a polymer matrix can increase Young’s modulus by up to 20%. Some studies report that the use of SWCNT can increase Young’s modulus and shear strength by more than 1,000% [43]. With the introduction of curvature into SWCNT, the elasticity of CNT slightly increases under tension and decreases under compression [44].

Various methodological approaches are used to improve mechanical, electrical, thermal, and barrier properties due to the unique characteristics of CNT. The two main types of matrices for obtaining composites are polymer and ceramic matrices. Polymer nanocomposites with CNT include thermoplastics (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene, polycarbonate), thermosetting resins (epoxy, phenol–formaldehyde), and elastomers (silicone, polyurethane) [45,46]. The main methods for incorporating carbon nanoparticles are (1) melt mixing, which is used, for example, for polyamide-6 or polypropylene, where shear forces at high temperatures ensure the dispersion of CNTs [47]; (2) mixing solutions, which is used for polyaniline, PET, and PVC. CNTs are pre-dispersed in solvents (dimethylformamide, chloroform) followed by polymer precipitation [48,49]. In addition, ultrasonic treatment [50], mechanical mixing [51], and probe dispersion [52]. Resin transfer molding deserves special mention, as it is used for epoxy matrices and provides a high degree of CNT wetting and the production of large-sized composites [53].

When ceramic matrices are used, CNT-reinforced ceramic composites (CNT-CMC) can be obtained, which are used in the aerospace, defense, and energy industries due to their high thermal stability and strength [54]. According to an analysis of the literature, the following methods of incorporating CNTs into ceramic matrices are most in demand: (1) mechanochemical mixing, in which matrix powders and CNTs are subjected to high-energy mixing in planetary mills [55]; (2) the sol–gel method is often used for SiO2 matrices and provides an optimal level of CNT distribution [56]; (3) hydrothermal synthesis is used to create hybrid nanostructures and improve interphase interaction [57,58]; and (4) spark plasma sintering (SPS) provides dense packing and control over microstructure, actively used for Al2O3 and SiC matrices with CNTs [59,60]. Hot pressing is a classic method for creating dense composites based on ZrO2 and Si3N4 [61,62]. The manufacturing parameters and some characteristics of composites based on polymer and ceramic matrices and CNTs are presented in detail in Table 2.

Characteristics and features of the production of composite materials reinforced with CNT, with polymer and ceramic matrices

| Criterion | Polymer matrices with CNT | Ceramic matrices with CNT |

|---|---|---|

| Processing temperature | Low (usually <300°C) | High (up to 1,600°C and above) |

| Methods of dispersing CNT | Simple: Ultrasound, dissolution, extrusion | Complex: Ball milling, sol–gel, SPS |

| Preservation of CNT structure | Good (at low temperatures) | Risk of destruction during sintering |

| Compatibility with CNT | Often poor, chemical functionalization required | Very poor without modification, especially with oxide matrices |

| Interfacial adhesion | Moderate, improved by functionalization | Complex, but can be high with good chemical compatibility |

| Alignment and orientation of CNT | Easily achieved by extrusion, centrifugation | Difficult to implement, requires special methods (magnetic field, freezing) |

| Technological simplicity | High, easily scalable | Low, requires complex equipment |

| Mechanical strength of the composite | Moderate, limited by polymer properties | High, especially with optimal sintering |

| Crack resistance | Insignificant improvement | Significant improvement due to CNT bridges |

| Thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity | Can be improved (depending on CNT content) | Significant improvement with CNT alignment |

| Material density | Low | High |

| Application | Electronics, biomedicine, packaging, flexible electronics | Aerospace, tools, thermal barriers |

Thus, the combination of CNT with various polymer and ceramic matrices using adapted synthesis methods provides a wide range of mechanical and functional characteristics, paving the way for the creation of a new generation of multifunctional nanocomposites. At the same time, the most preferred method for obtaining composites is FSP (Figure 2) with the introduction of dispersed nanofillers, as it combines technological versatility, a high degree of strengthening, and a wide range of applications [63–65].

![Figure 2

Composite creation procedure. Reproduced with permission from [63].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2025-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2025-0065_fig_002.jpg)

Composite creation procedure. Reproduced with permission from [63].

The comprehensive analysis of ceramic matrices modified with CNT is a priority area in modern materials science. It focuses on the development and fundamental understanding of new classes of nanostructured composites with improved performance characteristics. The relevance of this area is due to the need to create a new generation of structural and functional materials that are simultaneously high-strength, low-density, thermally and chemically resistant, and capable of integrating additional functions such as electrical conductivity, thermal stability, or crack resistance. Reinforcing ceramic matrices with CNT not only significantly expands the strength characteristics of brittle ceramics, but also increases the resistance to destruction and durability of materials under extreme loads.

3 Ceramic composites and nanocomposites

Ceramic materials and ceramic matrix composites (CMC) are of particular interest for a variety of applications. Ceramics are known to consist of metallic and non-metallic elements and are valued for their hardness and resistance to high temperatures. However, ceramic materials are very brittle, which limits their use [66]. They also have low tensile strength [67], but they are good thermal and electrical insulators [68]. Due to strong ionic or covalent bonds in ceramic materials, plastic deformation is difficult, resulting in their brittleness. There are traditional methods to reduce the brittleness of ceramic materials such as (i) grain size reduction, based on increasing the total area of grain boundaries to make it difficult for cracks to propagate; (ii) surface toughening, dispersion toughening by adding a second phase; and (iii) texturing by a given grain orientation [69]. Modern methods are aimed at obtaining CMC in which the ceramic material forms a continuous matrix and nanofillers of various types are used as a reinforcing component. These nanoparticles or nanofibers make it difficult for cracks to spread and enable composites to withstand sudden temperature changes without breaking. The ceramic matrix, in turn, enables the composite material to be resistant to corrosion and oxidation. Continuous or long and discontinuous or short fibers are used to increase the strength of CMC. Discontinuous or short-fiber composites consist of non-oxide alumina, as well as oxide alumina materials [70,71]. The utilization of zirconium oxides, SiC, TiB2, and aluminum nitride in the reinforcement of a ceramic matrix is outlined elsewhere [72,73]. Continuous or long fibers exhibit superior strength, which endures even when the ceramic matrix fractures, thereby mitigating the propagation of cracks. Conversely, short fibers are employed to enhance resistance to cracking. Monofilament fibers provide a better interfacial connection, which makes matrix materials more durable [74,75].

Depending on the matrix used, ceramic matrix nanocomposites are divided into oxide and non-oxide composite systems [76]. Nanofillers can additionally be classified by origin, composition, and size [77] (Figure 3).

Classification of nanofillers in terms of size and morphology.

Nanofillers, even at a level of less than 1%, can endow nanocomposites with desired properties. This is in contrast to higher loading levels of approximately 15–40 vol% for conventional microfillers in traditional composites [78].

Karbalaei Akbari et al. [79] introduced two types of TiB2 particles, namely micro- and nanocomposite reinforcements, into a molten A356 aluminum matrix using a mechanical stirrer. Nanocomposite elements allowed obtaining materials with enhanced tensile strength and viscosity. In particular, the addition of optimal amount of the TiB2 nanocomposite (1.5% by volume) resulted in a 43% increase in tensile strength and a 27% increase in elongation compared with a non-reinforced alloy.

In the majority of composite systems, it has been observed that nanofillers such as fibers, filamentous crystals, and plates at an optimal load level increase the fracture toughness of ceramics. These nanofillers have been shown to delay the onset of cracking and prevent crack propagation [80].

It should be noted that ceramic nanocomposite materials are of high practical importance, since they can be used in the aircraft industry to increase the performance of aircraft systems [81], as well as in mechanical engineering to increase the wear resistance of piston mechanisms [82].

Many new CMCs with improved properties have been developed. For example, a ceramic composite consisting of aluminum oxide, glass frit, and microencapsulated phase change materials was obtained, which could maintain stable heat storage characteristics after 200 melting-solidification cycles with minor latent heat losses [83]. In the study by Wang et al. [84], a high-temperature phase change material made of a ternary salt/porous Si3N4 composite was fabricated. The skeleton material was composed of Si3N4 porous ceramics, while the filler was a ternary salt consisting of 50 wt% sodium chloride, 30 wt% potassium chloride, and 20 wt% magnesium chloride. The thermal conductivity of the composite was found to be six times higher than that of pure ternary salts, and the thermophysical properties of the composite remained stable even after 300 thermal cycles.

In a recent study, multiphase ceramics composed of corundum, spinel, and mullite were obtained, exhibiting high resistance to thermal shock [85]. Furthermore, novel high-entropy disilicate (Y0.25Yb0.25Er0.25Sc0.25)2Si2O7 ((4RE0.25)2Si2O7) materials were also obtained through a two-step process, which demonstrated favorable phase stability during 1.5 h of sintering at 1,600°C, in addition to demonstrating excellent corrosion resistance [86].

It is noteworthy that carbon materials are among the most widely employed nano-sized additives in ceramic composites, and their utilization is described in more detail below.

4 Carbon reinforcing elements

Composite materials created by mixing different components have improved properties compared to the original constituents. For example, the powder metallurgy method makes it possible to combine metal powder with reinforcing material (fiber, ceramics or other metal), and the ratio of components is important for achieving the required characteristics. This method is cost-effective and allows producing complex shapes of composite products. In the field of materials science, nanocarbon has been identified as a particularly effective toughening phase in CMC. In recent years, there has been a surge of interest to the use of nanocarbon materials for the strengthening of polymer composites [87]. Promising nanofillers for this application include graphene oxide and graphene [88], pyrocarbon [89], and graphite [90], which have the potential to mitigate the limitations of ceramic materials due to their superior thermal, electrical, and mechanical properties. In addition, composites based on carbon materials and aluminum are lightweight, which is advantageous, for example, for the aerospace industry, where it is important to save fuel and reduce the emission of harmful compounds into the atmosphere.

A significant difficulty in obtaining ceramic composites with carbon nanofillers is to reach the uniform filler distribution. Due to the strong electrostatic interaction of the surfaces of nanomaterials, they are prone to aggregation in the composite material. Surface modification of carbon materials, addition of bonding agents and addition of surface active compounds are often used to optimize the interfacial interaction in matrices. The synthesis of SiCN(CNT) composite ceramics has been achieved through the polymer-derived method [91]. For SiCN(CNT) pyrolyzed at a temperature of 1,100°C, an optimal reflection loss of −38.40 dB was obtained at a frequency of 18 GHz in the sample with a thickness of 4.4 mm, and an effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) was 1.3 GHz (from 16.7 to 18 GHz). Besides, with a thickness of 4.7 mm, a wider EAB of 2.16 GHz (from 15.76 to 17.92 GHz) was achieved. Thus, SiCN composite ceramics containing CNT demonstrate an attractive potential for applications in the field of microwave radiation absorption [37]. Using the one-step sintering method, C/MgAl2O4 composites were obtained, and graphene with 6–10 layers was distributed in the agglomerates, increasing the materials’ resistance to oxidation, thermal shock, and slag corrosion [92].

A considerable number of studies have demonstrated that various types of carbon materials have the capacity to enhance the mechanical properties of ceramic matrices to a significant degree [93–95]. For instance, it has been shown that CNT can provide enhanced interlayer and intralayer reinforcement, as well as an increased resistance of composites to delamination [91]. The utilization of nanofibers as a reinforcing agent in materials is attributable to two principal factors: the high ratio of surface area to the volume of the fibers, and their high aspect ratio. Nanofillers have been shown to exhibit superior mechanical properties in comparison to micro-reinforcing materials; however, it is necessary to ensure good dispersion of nanoscale fillers. The analysis of literature data shows the problems in improving matrix properties when the use of equal volumes of nanofillers leads to incomplete changes in the properties of the resulting composite, which emphasizes the relevance of the study of properties and mechanisms of deformation of composites [96].

Tungsten carbide matrix composite reinforced with a hybrid nanocomponent of CNT, SiC nanowire (SiCnw), and graphene (G) (G/CNT/SiCnw-WC) was developed [97]. All the conventional toughening mechanisms, provided by utilization of separate G, CNT, or SiCnw, were operational, and a synergistic toughening effect was obtained as a result of improved uniform dispersion of G/CNT/SiCnw, which facilitated the maximization of the toughening effect. The augmentation of the number of toughening mechanisms is illustrated in Figure 4 [97].

![Figure 4

Scheme of toughening mechanisms in a ceramic composite, provided by a hybrid reinforcing agent G/CNT/SiCnw. Reproduced with permission from [97].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2025-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2025-0065_fig_004.jpg)

Scheme of toughening mechanisms in a ceramic composite, provided by a hybrid reinforcing agent G/CNT/SiCnw. Reproduced with permission from [97].

CNT can improve the thermal properties of polymers and ceramic materials. Shah et al. [98] produced a graphene/CNT/alumina hybrid composite and reported an increase in thermal conductivity of the composite at 1% CNTs and 0.4% wt% graphene. CNTs can be used to increase the crack resistance of ceramics [99]. Mirkhalaf et al. [100] compared the polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs) toughened with three nanofillers (CNT, Si3N4, and Al2O3 nanoparticles) and found that CNTs were less efficient than Si3N4 and Al2O3 nanoparticles (Figure 5a), because of the formation of CNT agglomerates (Figure 5c).

![Figure 5

Visualization of the mechanism of composite toughening using nanofillers. (a) Comparison of crack propagation in cases without fillers, with 6 wt% Al2O3, 6 wt% Si3N4 and 3 wt% of CNT. (b) A more thorough examination of the process of toughening by filling cracks in PDC modified with Al2O3. (c) Agglomeration of nanotubes that has been observed on the surface of specimens modified with CNT. All cracks were produced with the same force on the PDC. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License from [100], Copyright © 2021, Crown.](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2025-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2025-0065_fig_005.jpg)

Visualization of the mechanism of composite toughening using nanofillers. (a) Comparison of crack propagation in cases without fillers, with 6 wt% Al2O3, 6 wt% Si3N4 and 3 wt% of CNT. (b) A more thorough examination of the process of toughening by filling cracks in PDC modified with Al2O3. (c) Agglomeration of nanotubes that has been observed on the surface of specimens modified with CNT. All cracks were produced with the same force on the PDC. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License from [100], Copyright © 2021, Crown.

The incorporation of nanotubes resulted in a marked enhancement of the ceramics mechanical properties, with the addition of 1 wt% CNT leading to a 50% increase in the modulus of elasticity. However, the modulus of elasticity of the material remained almost constant with further addition of CNT. The hardness of the material increased from approximately 4.1 GPa for a specimen without filler to approximately 9.8 GPa (an enhancement of 2.5 times) for a sample containing 1 wt% CNT, after which it no longer increased [100]. The incorporation of nanotubes results in an enhancement of the overall mechanical properties, which may be attributed to the formation of microscopic cracks observed in several studies of CNT-reinforced PDCs [101].

Thus, carbon materials, both individually and as part of complex reinforcing compounds, can significantly enhance the properties of the initial matrix, provided that their uniform distribution in the matrix is ensured.

5 Dispersion of nanocarbon in a ceramic matrix

In addition to the advantageous properties of carbon materials, there are certain limitations that must be considered. A significant disadvantage of using carbon fibers is their inert surface, which results in the poor compatibility of the interface surface with polymer matrices, and, consequently, to numerous defects of the interface surface and pores in finished carbon fiber composites. The dispersion of nanocarbon in CMC is challenging due to its significantly large specific surface area, surface energy, van der Waals forces resulting from the intermolecular electric dipole moment, and interactions between functional groups, as well as its tendency toward aggregation and entanglement [101]. The interfaces between nanocarbon and ceramics are considered suitable due to disparities in surface tension and density. It is important to note that currently, there is no single method for measuring the strength of ceramic matrix nanocarbon composites. Traditionally, strength is defined as the energy required to propagate a crack per unit length. However, high anisotropy of composites makes the measurements difficult.

It is noteworthy that the characteristics of composites largely depend on the method of their manufacture [102]. Wet or dry mixing of carbon material with ceramic powder is most often used to produce composites [103], but this results in agglomeration and loss of the original structure of the materials. However, a novel method for the fabrication of nanocarbon/ceramic composites utilizing a combined gel casting and reduction sintering process has been proposed [104]. This novel one-step approach proposes a promising strategy for the production of aluminum oxide and nanocarbon composites. It is noteworthy that the nanocarbon-ceramic composite fabricated using Al2O3 exhibits excellent p-type semiconducting properties and ultrahigh carrier mobility in the holes, contrasting with the metallic property of a conventional composite [105].

Technologies for producing composites with improved properties are being developed. For instance, the creation of an integrated composite that can be used at an operating temperature of ≈1,900°C was described. This is approximately 300°C higher than that of the previously described porous materials that can be used for aerospace vehicles in oxidizing environments. The resulting material has the properties of ablation resistance (ablation rate of 0.38 µm s−1), thermal insulation (temperature difference of 1,050°C with a thickness of 10 mm), thermostability (shrinkage of 0.08%), and high load-bearing capacity (compressive strength of 90.5 MPa) at a temperature of 1,900°C. In addition, the material exhibits a substantially higher specific strength of 119 MPa per 1 cm3, which is 12–34 times greater than that of rigid insulation boards, which are the most widely used materials for wear-resistant and heat-insulating applications. Such a carbon-ceramic composite should facilitate the design and increase the operating temperatures of thermal protection systems for critical components, thereby significantly enhancing the performance of future high-temperature thermal protection systems for aerospace vehicles [106].

Homogeneous distribution of nanocarbons in the ceramic matrix is fundamental for improving composite properties. Three common methods are employed for the optimization of the dispersion of solids in aqueous solutions, namely surface wetting, electric double layer, and colloidal protection [107,108]. Additionally, the volume fraction of CNT within the matrices significantly impacts their dispersion and wettability. Therefore, it is recommended to select a low volume fraction to enhance dispersion and promote high wettability. Optimization of the volume fraction should not be compromised prior to developing a CNT-reinforced composite. The maximum tribological enhancement of composites through CNT reinforcement can only be accomplished under the condition of uniform dispersion and complete wettability of CNT [109].

6 Methods for estimating the dispersion of nanofillers

Filler uniformity can be assessed using direct and indirect methods. Direct dispersion estimation includes image analysis methods such as SEM and X-ray computed tomography (CT) [110], but it is difficult to quantitatively evaluate the fiber dispersion using these methods. The indirect method typically relies on mechanical or electrical characteristics for macroscale estimation, which is not suitable for individual distribution checks, considering the influence of the matrix [110].

The study of composite morphology is important for understanding their physical properties, and electron microscopy methods such as SEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are widely used for this purpose. These methods are very helpful for determining the shape and size of domains in composites, as well as the degree of their adhesion to the main component at the interface. The application of SEM facilitates the correlation of alterations in morphology with the processing parameters employed [111].

For example, the structure of the Al2O3 scaffold sintered at 1,400°C for 2 h was studied using SEM. It was shown that the thickness of the ceramic layers was approximately 360 μm (Figure 6) [112].

![Figure 6

The macrostructures of (a) an Al2O3 scaffold and (b) an Al/Al2O3 composite visualized with SEM. Magnified views of the microstructures of a porous Al2O3 wall, an interface, and an infiltrated ceramic layer are shown in the insets (a1), (b1), and (b2), respectively. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License from [112], 2024 Elsevier B.V.](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2025-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2025-0065_fig_006.jpg)

The macrostructures of (a) an Al2O3 scaffold and (b) an Al/Al2O3 composite visualized with SEM. Magnified views of the microstructures of a porous Al2O3 wall, an interface, and an infiltrated ceramic layer are shown in the insets (a1), (b1), and (b2), respectively. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License from [112], 2024 Elsevier B.V.

In order to conduct a more comprehensive study of the physical properties of composites, it is important to combine various methods, such as wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), small-angle X-ray scattering, small-angle neutron scattering, light scattering, and differential light scattering. Scanning calorimetry [113] is also a useful method in this respect.

The use of theoretical models and numerical simulations to predict the physical properties of a composite can be an efficient way to save time and cost when developing a new composite, even if it cannot completely replace experimental research [113–115].

With the help of supercomputer methods, realistic modeling of large-scale tasks consisting of several objects has become faster and more accessible in recent years, for example, modeling the formation of a seepage network. A microstructural model has been developed for modeling the nonlinear behavior of the conductivity of composite dielectrics modified with metal oxide fillers, which allows taking into account the features of the destruction of the insulating matrix and the mechanism of internal conductivity, as well as the exact percolation threshold, which was 33% [116].

A new morphological model was used to understand the importance of CNT aggregation and electron tunneling. The influence of the geometry of the carbon nanofiller, aspect ratio, aggregation, and concentration has also been studied. The simulation results show that the degree of aggregation has a significant effect on the change in electrical conductivity depending on the concentration of nanoadditives. Well dispersed nanofillers are not always preferred for forming conductive networks [117]. Currently, machine learning is successfully used to predict the properties of composite materials, which involves analyzing and determining the nonlinear relationships between properties and related factors based on existing information. For example, a trained neural network can be used to predict Young’s modulus and tensile strength of polyethylene nanocomposites based on the geometric parameters of the nanometric filler. The combined use of deep learning with traditional experimental approaches makes it possible to obtain more accurate predictions of the mechanical properties of a composite material [118].

7 Conclusion

The study of the structural characteristics of composites and nanostructures is of fundamental importance in materials science. Thanks to their unique properties, ceramics and their composites can replace traditional materials in various fields, such as gray cast iron in brake systems. This is largely due to their improved physical and mechanical properties, in particular high wear resistance and low friction coefficient, resistance to high temperatures and other factors that are crucial for reducing component losses during rotation and increasing component durability [119]. This article considers the use of carbon materials to enhance the properties of ceramic matrices. It is demonstrated that

The introduction of nanofillers with different morphologies and chemical compositions in various proportions allows for the targeted improvement of key properties of the base matrix.

An increase in the mechanical (strength, stiffness, and resistance to destruction), thermal, and electrochemical properties of composites has been demonstrated.

Thanks to their significantly larger specific surface area, nanofillers can achieve excellent interaction with the matrix, which leads to improved dispersion and, ultimately, more promising composites than when using macrofillers.

To evaluate filler dispersion, direct methods (microscopy [e.g., SEM, TEM, AFM], spectroscopy, and tomographic methods) are used, as well as analysis based on changes in physical, mechanical, or electrical properties. Each method has its advantages and limitations and can be selected depending on the type of matrix and the nature of the filler.

The use of computational tools, including finite-element analysis, multiscale modeling, and machine learning algorithms, opens up new possibilities for predicting the behavior of composites, optimizing the selection and distribution of fillers, and developing a new generation of high-performance nanocomposites.

-

Funding information: The author states no funding involved.

-

Author contribution: The only author Pisarev A.V. carried out the whole work on the research.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

References

[1] Biener J, Wittstock A, Baumann TF, Weissmüller J, Bäumer M, Hamza AV. Surface chemistry in nanoscale materials. Materials. 2009;2(4):2404–28.10.3390/ma2042404Search in Google Scholar

[2] Patil SP, Burungale VV. Physical and chemical properties of nanomaterials. In Nanomedicines for breast cancer theranostics. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 17–31.10.1016/B978-0-12-820016-2.00002-1Search in Google Scholar

[3] Laadjal K, Cardoso AJM. Multilayer ceramic capacitors: An overview of failure mechanisms, perspectives, and challenges. Electronics (Basel). 2023;12:1297. 10.3390/electronics12061297.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Cazan C, Enesca A, Andronic L. Synergic effect of TiO2 filler on the mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites. Polymers. 2021;13(12):2017.10.3390/polym13122017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Dubey KA, Hassan PA, Bhardwaj YK. High performance polymer nanocomposites for structural applications. In Materials under extreme conditions. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. p. 159–94.10.1016/B978-0-12-801300-7.00005-XSearch in Google Scholar

[6] Khanna V, Kumar V, Bansal SA. Mechanical properties of aluminium-graphene/carbon nanotubes (CNTs) metal matrix composites: Advancement, opportunities and perspective. Mater Res Bull. 2021;138:111224.10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111224Search in Google Scholar

[7] Guchait A, Saxena A, Chattopadhyay S, Mondal T. Influence of nanofillers on adhesion properties of polymeric composites. ACS Omega. 2022;7:3844–59.10.1021/acsomega.1c05448Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Mandal S, Roy D, Prasad NE, Joshi M. Interfacial interactions and properties of cellular structured polyurethane nanocomposite based on carbonaceous nano‐fillers. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138(2):e49775.10.1002/app.49775Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lee MS, Yee DW, Ye M, Macfarlane RJ. Nanoparticle assembly as a materials development tool. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(8):3330–46.10.1021/jacs.1c12335Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Verma VK, Verma S. Applications and potential of advanced materials: An overview. Mater Today: Proc. 2024;1–4. 10.1016/j.matpr.2024.05.004б.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Tamayo JA, Riascos M, Vargas CA, Baena LM. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy via electron beam melting for the development of implants for the biomedical industry. Heliyon. 2021;7(5):e06892.10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06892Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Gialanella S, Malandruccolo A. Aerospace alloys. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 129–89.10.1007/978-3-030-24440-8_4Search in Google Scholar

[13] Han H, Lou Z, Wang Q, Xu L, Li Y. Introducing rich heterojunction surfaces to enhance the high-frequency electromagnetic attenuation response of flexible fibre-based wearable absorbers. Adv Fiber Mater. 2024;6(3):739–57.10.1007/s42765-024-00387-8Search in Google Scholar

[14] Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science. 2008;321(5887):385–8.10.1126/science.1157996Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Gómez-Navarro C, Burghard M, Kern K. Elastic properties of chemically derived single graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 2008;8(7):2045–9.10.1021/nl801384ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Suk JW, Piner RD, An J, Ruoff RS. Mechanical properties of monolayer graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2010;4(11):6557–64.10.1021/nn101781vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Kang S-H, Fang T-H, Hong Z-H, Chuang C-H. Mechanical properties of free-standing graphene oxide. Diam Relat Mater. 2013;38:73–8.10.1016/j.diamond.2013.06.016Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ranjbartoreh AR, Wang B, Shen X, Wang G. Advanced mechanical properties of graphene paper. J Appl Phys. 2011;109(1):014306.10.1063/1.3528213Search in Google Scholar

[19] Gan YX. Effect of interface structure on mechanical properties of advanced composite materials. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(12):5115–34.10.3390/ijms10125115Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Li Y, Huang X, Zeng L, Li R, Tian H, Fu X, et al. A review of the electrical and mechanical properties of carbon nanofiller-reinforced polymer composites. J Mater Sci. 2019;54:1036–76.10.1007/s10853-018-3006-9Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chan KF, Zaid MHM, Mamat MS, Liza S, Tanemura M, Yaakob Y. Recent developments in carbon nanotubes-reinforced ceramic matrix composites: A review on dispersion and densification techniques. Crystals. 2021;11(5):457.10.3390/cryst11050457Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mondal S, Mondal P, Mishra DP. Research progress on ceramic nanomaterials reinforced aluminum matrix nanocomposites. Mater Sci Technol. 2023;39(15):1841–57.10.1080/02670836.2023.2187153Search in Google Scholar

[23] Du X, Gao T, Liu G, Liu X. In situ synthesizing SiC particles and its strengthening effect on an Al–Si–Cu–Ni–Mg piston alloy. J Alloy Compd. 2017;695:1–8.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.10.170Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yao X, Zhang Z, Zheng YF, Kong C, Quadir MZ, Liang JM, et al. Effects of SiC nanoparticle content on the microstructure and tensile mechanical properties of ultrafine grained AA6063-SiCnp nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy. J Mater Sci & Technol. 2017;33(9):1023–30.10.1016/j.jmst.2016.09.022Search in Google Scholar

[25] El-Daly AA, Abdelhameed M, Hashish M, Eid AM. Synthesis of Al/SiC nanocomposite and evaluation of its mechanical properties using pulse echo overlap method. J Alloy Compd. 2012;542:51–8.10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.07.102Search in Google Scholar

[26] Casati R, Fiocchi J, Fabrizi A, Lecis NORA, Bonollo F, Vedani M. Effect of ball milling on the ageing response of Al2618 composites reinforced with SiC and oxide nanoparticles. J Alloy Compd. 2017;693:909–20.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.09.265Search in Google Scholar

[27] Pan L, Song K, Gu J, Qiu T, Yang J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of (TiB2 + SiC) reinforced Ti3SiC2 composites synthesized by in situ hot pressing. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2016;13(4):629–35.10.1111/ijac.12544Search in Google Scholar

[28] Li H, Zhou Y, Cui A, Zheng Y, Huang Z, Zhai H, et al. Ti3 SiC2 reinforced ZA27 alloy composites with enhanced mechanical properties. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2016;13:636–43.10.1111/ijac.12531Search in Google Scholar

[29] Singh P, Mishra RK, Singh B, Gupta V. Mechanical and tribological properties of zinc-aluminium (ZA-27) metal matrix composites: A review. Adv Mater Process Technol. 2025;11(1):73–91.10.1080/2374068X.2024.2304394Search in Google Scholar

[30] Sandhu KS, Singh H, Singh G. Implications of nanomaterials reinforcement along with sub-zero temperature cooling on microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir processed Al7075 alloy. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2024;1–19. 10.1080/01694243.2024.2409938.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Dai J, Pineda EJ, Bednarcyk BA, Singh J, Yamamoto N. Micromechanics-based simulation of B4C-TiB2 composite fracture under tensile load. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2022;42(14):6364–78.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2022.07.010Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ko HS, Lee S, Jho JY. Synthesis and modification of hydroxyapatite nanofiber for poly (Lactic acid) composites with enhanced mechanical strength and bioactivity. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(1):213.10.3390/nano11010213Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Rao CNR, Satishkumar BC, Govindaraj A, Nath M. Nanotubes. chemphyschem. 2001;2(2):78–105.10.1002/1439-7641(20010216)2:2<78::AID-CPHC78>3.0.CO;2-7Search in Google Scholar

[34] Kukovecz Á, Kozma G, Kónya Z. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Springer handbook of nanomaterials. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. p. 147–88.10.1007/978-3-642-20595-8_5Search in Google Scholar

[35] Rozhina E, Batasheva S, Miftakhova R, Yan X, Vikulina A, Volodkin D, et al. Comparative cytotoxicity of kaolinite, halloysite, multiwalled carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide. Appl Clay Sci. 2021;205:106041.10.1016/j.clay.2021.106041Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ali A, Koloor SSR, Alshehri AH, Arockiarajan A. Carbon nanotube characteristics and enhancement effects on the mechanical features of polymer-based materials and structures–A review. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:6495–521.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.072Search in Google Scholar

[37] Harito C, Bavykin DV, Yuliarto B, Dipojono HK, Walsh FC. Polymer nanocomposites having a high filler content: Synthesis, structures, properties, and applications. Nanoscale. 2019;11(11):4653–82.10.1039/C9NR00117DSearch in Google Scholar

[38] Zhou L, Liu K, Yuan T, Liu Z, Wang Q, Xiao B, et al. Investigation into the influence of CNTs configuration on the thermal expansion coefficient of CNT/Al composites. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;18:3478–91.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.04.042Search in Google Scholar

[39] Murugesan R, Gopal M, Murali G. Effect of Cu, Ni addition on the CNTs dispersion, wear and thermal expansion behavior of Al-CNT composites by molecular mixing and mechanical alloying. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;495:143542.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.143542Search in Google Scholar

[40] Liu ZY, Xiao BL, Wang WG, Ma ZY. Effect of carbon nanotube orientation on mechanical properties and thermal expansion coefficient of carbon nanotube-reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Acta Metall Sin (Engl Lett). 2014;27:901–8.10.1007/s40195-014-0136-1Search in Google Scholar

[41] Qian H, Greenhalgh ES, Shaffer MS, Bismarck A. Carbon nanotube-based hierarchical composites: A review. J Mater Chem. 2010;20(23):4751–62.10.1039/c000041hSearch in Google Scholar

[42] Zhu R, Pan E, Roy AK. Molecular dynamics study of the stress–strain behavior of carbon-nanotube reinforced Epon 862 composites. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2007;447(1–2):51–7.10.1016/j.msea.2006.10.054Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zheng Q, Xue Q, Yan K, Gao X, Li Q, Hao L. Effect of chemisorption on the interfacial bonding characteristics of carbon nanotube–polymer composites. Polymer. 2008;49(3):800–8.10.1016/j.polymer.2007.12.018Search in Google Scholar

[44] Vijayaraghavan V, Wong CH. Temperature, defect and size effect on the elastic properties of imperfectly straight carbon nanotubes by using molecular dynamics simulation. Comput Mater Sci. 2013;71:184–91.10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.12.025Search in Google Scholar

[45] Chaurasia A, Suzhu Y, Henry CKF, Mogal VT, Saha S. Properties and applications of polymer nanocomposites. In Handbook of manufacturing engineering and technology. London: Springer; 2014. p. 1–46.10.1007/978-1-4471-4976-7_22-1Search in Google Scholar

[46] Latif Z, Ali M, Lee EJ, Zubair Z, Lee KH. Thermal and mechanical properties of nano-carbon-reinforced polymeric nanocomposites: A review. J Compos Sci. 2023;7(10):441.10.3390/jcs7100441Search in Google Scholar

[47] Faghihi M, Shojaei A, Bagheri R. Characterization of polyamide 6/carbon nanotube composites prepared by melt mixing-effect of matrix molecular weight and structure. Compos Part B: Eng. 2015;78:50–64.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.03.049Search in Google Scholar

[48] Al Sheheri SZ, Al-Amshany ZM, Al Sulami QA, Tashkandi NY, Hussein MA, El-Shishtawy RM. The preparation of carbon nanofillers and their role on the performance of variable polymer nanocomposites. Des Monomers Polym. 2019;22(1):8–53. 10.1080/15685551.2019.1565664 Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Mostafa MH, Ali ES, Darwish MS. Polyaniline/carbon nanotube composites in sensor applications. Mater Chem Phys. 2022;291:126699.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2022.126699Search in Google Scholar

[50] Gao X, Isayev AI, Yi C. Ultrasonic treatment of polycarbonate/carbon nanotubes composites. Polymer. 2016;84:209–22.10.1016/j.polymer.2015.12.051Search in Google Scholar

[51] Huang YY, Terentjev EM. Dispersion of carbon nanotubes: Mixing, sonication, stabilization, and composite properties. Polymers. 2012;4(1):275–95.10.3390/polym4010275Search in Google Scholar

[52] Liu CX, Choi JW. Improved dispersion of carbon nanotubes in polymers at high concentrations. Nanomaterials. 2012;2(4):329–47.10.3390/nano2040329Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Liu W, Wei B, Xu F. Investigation on the mechanical and electrical properties of carbon nanotube/epoxy composites produced by resin transfer molding. J Compos Mater. 2017;51(14):2035–43.10.1177/0021998316667541Search in Google Scholar

[54] Sales-Contini RC. Electrical discharge machining of composites: A critical review of challenges and innovations. J Mech Eng Manuf. 2025;1(1):5.10.53941/jmem.2025.100005Search in Google Scholar

[55] Welham NJ, Willis PE, Kerr T. Mechanochemical formation of metal–ceramic composites. J Am Ceram Soc. 2000;83(1):33–40.10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01144.xSearch in Google Scholar

[56] Silva PR, Almeida VO, Machado GB, Benvenutti EV, Costa TM, Gallas MR. Surfactant-based dispersant for multiwall carbon nanotubes to prepare ceramic composites by a sol–gel method. Langmuir. 2012;28(2):1447–52.10.1021/la203056fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Fan X, Yu C, Ling Z, Yang J, Qiu J. Hydrothermal synthesis of phosphate-functionalized carbon nanotube-containing carbon composites for supercapacitors with highly stable performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(6):2104–10.10.1021/am303052nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Gao H, Shen JY, Zhang H, Gao X, Tang XN, Zhu LH, et al. Enhanced toughness of KZr2 (PO4) 3 ceramics via hydrothermal incorporation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Ceram Int. 2025;51(2):1499–507.10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.11.122Search in Google Scholar

[59] Wiśniewska M, Laptev AM, Marczewski M, Krzyżaniak W, Leshchynsky V, Celotti L, et al. Towards homogeneous spark plasma sintering of complex-shaped ceramic matrix composites. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2024;44(12):7139–48.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2024.04.065Search in Google Scholar

[60] Mir AH, Sheikh NA. Effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on material properties of spark plasma sintered silicon nitride-based advanced ceramic composites. J Mater Eng Perform. 2025;34:17284–96. 10.1007/s11665-024-10421-w.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Ibadi M, Supriadi S, Purnomo H, Setianto MH, Wibowo HB, Whulanza Y. Challenges and innovative solutions in fabrication of ceramic matrix composite for ultra high-temperature application. Sci Sinter. 2025;00:14–4. 10.2298/SOS250116014I.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Li MX, Wei W, Zhao Y, Li M, Huang H, Chen Z, et al. Fabrication and characterization of ceramic WC10Co4Cr-YSZ composite coating via HVOF spraying core-shell powders. Ceram Int. 2025;51(14):19058–70.10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.02.085Search in Google Scholar

[63] Dwivedi SP, Sharma S, Singh A. Tailoring AlSi7Mg0.3 composite properties with CoCrMoNbTi high entropy alloy particles addition via FSP technique. Mater Chem Phys. 2024;315:129038.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.129038Search in Google Scholar

[64] Adi SS, Malik VR. Friction stir processing of aluminum machining waste: carbon nanostructure reinforcements for enhanced composite performance-a comprehensive review. Mater Manuf Process. 2025;40(3):285–334.10.1080/10426914.2024.2425628Search in Google Scholar

[65] Khan MA, Butola R, Gupta N. A review of nanoparticle reinforced surface composites processed by friction stir processing. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2023;37(4):565–601.10.1080/01694243.2022.2037054Search in Google Scholar

[66] Ryan W. Properties of ceramic raw materials. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Rice RW. Effects of environment and temperature on ceramic tensile strength–grain size relations. J Mater Sci. 1997;32(12):3071–87.10.1023/A:1018630113180Search in Google Scholar

[68] Chaudhary RP, Parameswaran C, Idrees M, Rasaki AS, Liu C, Chen Z, et al. Additive manufacturing of polymer-derived ceramics: Materials, technologies, properties and potential applications. Prog Mater Sci. 2022;128:100969.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.100969Search in Google Scholar

[69] Sun J, Zhao J, Chen Y, Wang L, Yun X, Huang Z. Macro-micro-nano multistage toughening in nano-laminated graphene ceramic composites. Mater Today Phys. 2022;22:100595.10.1016/j.mtphys.2021.100595Search in Google Scholar

[70] Dhanasekar S, Ganesan AT, Rani TL, Vinjamuri VK, Nageswara Rao M, Shankar E, et al. A comprehensive study of ceramic matrix composites for space applications. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2022;2022(1):6160591.10.1155/2022/6160591Search in Google Scholar

[71] Kumar M, Devi C, Hemath M, Mandol S, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S. Prospects of ceramic matrix composites in engineering and commercial applications. Applications of composite materials in engineering. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2025. p. 419–36. 10.1016/B978-0-443-13989-5.00017-6.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Kaur DP, Raj S, Bhandari M. Recent advances in structural ceramics. Advanced ceramics for versatile interdisciplinary applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. p. 15–39.10.1016/B978-0-323-89952-9.00008-7Search in Google Scholar

[73] Kalin M. Friction and wear of ceramics. In ASM handbook. Friction, lubrication, and wear technology. Vol. 18, ASM International; 2017. p. 542–9.10.31399/asm.hb.v18.a0006431Search in Google Scholar

[74] Cherevinskiy AP, Ponomarenko AD, Budylin NY, Shapagin AV. Interfacial strength and its regulation in the carbon monofiber/epoxy binder system. Polymer. 2024;309:127430.10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127430Search in Google Scholar

[75] Qiu B, Qiu B, Sun T, Zou Q, Yuan M, Zhou S, et al. Constructing a multiscale rigid-flexible interfacial structure at the interphase by hydrogen bonding to improve the interfacial performance of high modulus carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2022;229:109672.10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109672Search in Google Scholar

[76] Basu B, Balani K. Advanced structural ceramics. United States: Wiley; 2011.10.1002/9781118037300Search in Google Scholar

[77] Sharma N, Saxena T, Alam SN, Ray BC, Biswas K, Jha SK. Ceramic-based nanocomposites: A perspective from carbonaceous nanofillers. Mater Today Commun. 2022;31:103764.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103764Search in Google Scholar

[78] Le B, Khaliq J, Huo D, Teng X, Shyha I. A review on nanocomposites. Part 1: Mechanical properties. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2020;142:100801.10.1115/1.4047047Search in Google Scholar

[79] Karbalaei Akbari M, Baharvandi HR, Shirvanimoghaddam K. Tensile and fracture behavior of nano/micro TiB2 particle reinforced casting A356 aluminum alloy composites. Mater Des (1980–2015). 2015;66:150–61.10.1016/j.matdes.2014.10.048Search in Google Scholar

[80] Rafiee R, Rabczuk T, Milani AS, Tserpes KI. Advances in characterization and modeling of nanoreinforced composites. J Nanomater. 2016;2016:1.10.1155/2016/9481053Search in Google Scholar

[81] Chate GR, Kulkarni RM, Chate VR, GC MP, Sollapur S, Shettar M. Ceramic material coatings: Emerging future applications. In Advanced ceramic coatings for emerging applications. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 3–17.10.1016/B978-0-323-99624-2.00007-3Search in Google Scholar

[82] Ma Q, Zou D, Wang Y, Lei K. Preparation and properties of novel ceramic composites based on microencapsulated phase change materials (MEPCMs) with high thermal stability. Ceram Int. 2021;47(17):24240–51.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.05.135Search in Google Scholar

[83] Lv L, Xiao G, Ding D. Improved thermal shock resistance of low-carbon Al2O3–C refractories fabricated with C/MgAl2O4 composite powders. Ceram Int. 2021;47(14):20169–77.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.023Search in Google Scholar

[84] Wang H, Ran X, Zhong Y, Lu L, Lin J, He G, et al. Ternary chloride salt–porous ceramic composite as a high-temperature phase change material. Energy. 2022;238:121838.10.1016/j.energy.2021.121838Search in Google Scholar

[85] Xu J, Su Z, Liu J, Lin K, Zhang Y. Design, preparation and characterization of multiphase heat storage ceramic balls with high thermal shock resistance. Ceram Int. 2025;51(15):20745–54.10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.02.241Search in Google Scholar

[86] Wang X, Cheng M, Xiao G, Wang C, Qiao R, Zhang F, et al. Preparation and corrosion resistance of high-entropy disilicate (Y0.25Yb0.25Er0.25Sc0.25)2Si2O7 ceramics. Corros Sci. 2021;192:109786.10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109786Search in Google Scholar

[87] Rativa-Parada W, Nilufar S. Nanocarbon-infused metal matrix composites: A review. JOM. 2023;75(9):4009–23.10.1007/s11837-023-05905-4Search in Google Scholar

[88] Madhankumar A, Xavior A. Graphene reinforced ceramic matrix composite (GRCMC)–state of the art. Eng Res Express. 2024;6:022503. 10.1088/2631-8695/ad476a.Search in Google Scholar

[89] Xu J, Guo L, Wang H, Li K, Wang T, Li W. Mechanical property and toughening mechanism of 2.5D C/C-SiC composites with high textured pyrocarbon interface. Ceram Int. 2021;47:29183–90. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.081.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Jana P, Oza MJ, Schell KG, Bucharsky EC, Laha T, Roy S. Study of the elastic properties and thermal shock behavior of Al–SiC-graphite hybrid composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Ceram Int. 2022;48:5386–96.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.082Search in Google Scholar

[91] Wang S, Gong H, Zhang Y, Ashfaq MZ. Microwave absorption properties of polymer-derived SiCN (CNTs) composite ceramics. Ceram Int. 2021;47(1):1294–302.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.08.250Search in Google Scholar

[92] Li N, dong Wang G, Melly SK, Peng T, Li YC, Di Zhao Q, et al. Interlaminar properties of GFRP laminates toughened by CNTs buckypaper interlayer. Compos Struct. 2019;208:13–22.10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.10.002Search in Google Scholar

[93] Zhang C, Hu P, Xun L, Zhou Y, Han J, Zhang X. A universal strategy towards the fabrication of ultra-high temperature ceramic matrix composites with outstanding mechanical properties and ablation resistance. Compos Part B: Eng. 2024;280:111485.10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111485Search in Google Scholar

[94] Li J, Liu B, Ren Q, Cheng J, Tan J, Sheng J, et al. Nanoarchitected graphene/ceramic composites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2025;297:112296.10.1016/j.compositesb.2025.112296Search in Google Scholar

[95] Zeng S, Wu H, Li S, Gong L, Ye X, Zhang H, et al. Preparation and properties of three-dimensional continuous network reinforced Graphite/SiC ceramic composite insulation materials. Ceram Int. 2024;50(17):30252–62.10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.323Search in Google Scholar

[96] Morales-Flórez V, Domínguez-Rodríguez A. Mechanical properties of ceramics reinforced with allotropic forms of carbon. Prog Mater Sci. 2022;128:100966.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.100966Search in Google Scholar

[97] Sun J, Zhai P, Chen Y, Zhao J, Huang Z. Hierarchical toughening of laminated nanocomposites with three-dimensional graphene/carbon nanotube/SiC nanowire. Mater Today Nano. 2022;18:100180.10.1016/j.mtnano.2022.100180Search in Google Scholar

[98] Shah WA, Luo X, Yang YQ. Microstructure, mechanical, and thermal properties of graphene and carbon nanotube-reinforced Al2O3 nanocomposites. J Mater Science: Mater Electron. 2021;32:13656–72.10.1007/s10854-021-05944-0Search in Google Scholar

[99] Ramachandran K, Boopalan V, Bear JC, Subramani R. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)-reinforced ceramic nanocomposites for aerospace applications: A review. J Mater Sci. 2022;57:3923–53.10.1007/s10853-021-06760-xSearch in Google Scholar

[100] Mirkhalaf M, Yazdani Sarvestani H, Yang Q, Jakubinek MB, Ashrafi B. A comparative study of nano-fillers to improve toughness and modulus of polymer-derived ceramics. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6951.10.1038/s41598-021-82365-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[101] Yang Y, Ramirez C, Wang X, Guo Z, Tokranov A, Zhao R, et al. Impact of carbon nanotube defects on fracture mechanisms in ceramic nanocomposites. Carbon N Y. 2017;115:402–8.10.1016/j.carbon.2017.01.029Search in Google Scholar

[102] Vilatela JJ, Eder D. Nanocarbon composites and hybrids in sustainability: A review. ChemSusChem. 2012;5:456–78.10.1002/cssc.201100536Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[103] Zhu J, Abeykoon C, Karim N. Investigation into the effects of fillers in polymer processing. Int J Lightweight Mater Manuf. 2021;4:370–82.10.1016/j.ijlmm.2021.04.003Search in Google Scholar

[104] Tatami J, Nakano H, Wakihara T, Komeya K. Development of advanced ceramics by powder composite process. KONA Powder Part J. 2010;28:227–40.10.14356/kona.2010020Search in Google Scholar

[105] Maitre A, Lefort P. Solid state reaction of zirconia with carbon. Solid State Ion. 1997;104:109–22.10.1016/S0167-2738(97)00398-6Search in Google Scholar

[106] Xin Y, Takeuchi Y, Shirai T. Influence of ceramic matrix on semi-conductive properties of nano-carbon/ceramic composites fabricated via reductive sintering of gel-casted bodies. Ceram Int. 2021;47:23670–6.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.305Search in Google Scholar

[107] Yan M, Hu C, Li J, Zhao R, Pang S, Liang B, et al. An unusual carbon–ceramic composite with gradients in composition and porosity delivering outstanding thermal protection performance up to 1900 C. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(36):2204133.10.1002/adfm.202204133Search in Google Scholar

[108] Ujah CO, Kallon DVV, Aigbodion VS. Tribological properties of CNTs-reinforced nano composite materials. Lubricants. 2023;11(3):95.10.3390/lubricants11030095Search in Google Scholar

[109] Gao J, Wang Z, Zhang T, Zhou L. Dispersion of carbon fibers in cement-based composites with different mixing methods. Constr Build Mater. 2017;134:220–7.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.047Search in Google Scholar

[110] Chuang W, Lei P, Bing-Liang L, Ni G, Li-Ping Z, Ke-Zhi L. Influences of molding processes and different dispersants on the dispersion of chopped carbon fibers in cement matrix. Heliyon. 2018;4(10):e00868.10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00868Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[111] Khare HS, Burris DL. A quantitative method for measuring nanocomposite dispersion. Polymer. 2010;51(3):719–29.10.1016/j.polymer.2009.12.031Search in Google Scholar

[112] Jiang MY, Meng XY, Zhou J, Wei ZY, Zhang HF, Shen P. Design and manufacture of near-net-shape metal-ceramic composites with gradient-layered structure and optimized damage tolerance. Addit Manuf. 2024;84:104112.10.1016/j.addma.2024.104112Search in Google Scholar

[113] Dorigato A, Fredi G. Effect of nanofillers addition on the compatibilization of polymer blends. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res. 2024;7:405–27.10.1016/j.aiepr.2023.09.004Search in Google Scholar

[114] Torquato S. Modeling of physical properties of composite materials. Int J Solids Struct. 2000;37(1–2):411–22.10.1016/S0020-7683(99)00103-1Search in Google Scholar

[115] Yan W, Lin RJT, Bhattacharyya D. Particulate reinforced rotationally moulded polyethylene composites–mixing methods and mechanical properties. Compos Sci Technol. 2006;66(13):2080–8.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.12.022Search in Google Scholar

[116] Myroshnychenko V, Smirnov S, Mulavarickal Jose PM, Brosseau C, Förstner J. Nonlinear dielectric properties of random paraelectric-dielectric composites. Acta Mater. 2021;203:116432.10.1016/j.actamat.2020.10.051Search in Google Scholar

[117] Sun Z, Shan Z, Shao T, Li J, Wu X. A multiscale modeling for predicting the thermal expansion behaviors of 3D C/SiC composites considering porosity and fiber volume fraction. Ceram Int. 2021;47(6):7925–36.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.11.142Search in Google Scholar

[118] Yang J, Jiang P, Suhail SA, Sufian M, Deifalla AF. Experimental investigation and AI prediction modelling of ceramic waste powder concrete–An approach towards sustainable construction. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;23:3676–96.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[119] Almansoori A, Balázsi K, Balázsi C. Advances, challenges, and applications of graphene and carbon nanotube-reinforced engineering ceramics. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(23):1881.10.3390/nano14231881Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)