Abstract

Multifunctional characteristics are of significance for development of bionic skin materials. Herein, we report the collagen fibers (CFs) as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films (PCBPP) that integrate the diverse properties including the good thermal stability, water resistance, self-healing ability, adhesiveness, benign biocompatibility, and sensitive electrical signal response within a single structure, realize much more favorable functionalities in mimicking natural skin. The CFs as biomass template well immobilize and stabilize the polypyrrole (PPy) nanoparticles, which simultaneously improves the dispersity of PPy and enhances its conductivity. More importantly, due to the CFs constructed conductive paths and micro- and nano-sensing structure, the PCBPP prepared e-skin exhibits the GF value of 0.366 in the strain range of 10–40% and is able to distinguish different strain intensities and monitor the movements of the human body, including wrist bending, elbow bending, and swallowing. The self-healed PCBPP prepared e-skin exhibited the recoverable sensitivity. Our investigation provided a new prospect for designing CFs as conductive network packed multifunctional composite film and the as-prepared PCBPP exhibits great potential for versatile applications in various wearable devices and in the field of artificial intelligence.

1 Introduction

Nature is genius to provide numerous inspirations for development of biomimetic multifunctional materials. Natural skins possess flexibility, self-healing capabilities, and the ability to sense diverse stimuli from the external environment [1–3]. Consequently, the wearable artificial electronic skin (e-skin) is devised to mimic the mechanical and sensory properties of human skin, with potential applications in biomedical sensors, health monitoring/diagnostics, robotic prosthetics, and human–machine interface [4,5]. Desirable traits of e-skin encompass high mechanical strength, flexibility, good adhesion, self-healing ability, as well as conductivity and sensory functions, all of which are considered as essential components for bionic skin materials [6]. However, designing a smart material that simultaneously possesses all these functions concurrently remains a formidable challenge.

Over the past few years, considerable research studies have devoted to the development of multifunctional conductive hydrogels. However, these hydrogels often exhibit poor mechanical property, conductivity, and long-term usability due to the rapid loss of water, which limits their practical applications in flexible electrodes [7–9]. Plastic films emerge as highly promising candidates for development of e-skin, particularly because they feature good mechanical strength, low cost effectiveness, and can be produced in large sheets [10]. As a biocompatible and hydrophilic polymer, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) prepared composite films with enhanced mechanical strength show considerable potential to replace hydrogel-based e-skin sensors for e-skin applications [11–13]. Polyethylene oxide (PEO) is a kind of crystalline and thermoplastic water-soluble polymer, in which the terminal hydroxyl group provides a ready-made site for covalent bonding with other molecules and surfaces [14,15]. Therefore, the incorporation of PEO into PVA possessing abundant hydroxyl groups has ability to facilitate the forming of hydrogen bonds, which is conductive to fabricating flexible, stretchable, and self-healing composite films.

Polypyrrole (PPy), a highly promising conductive polymer, offering rapid charge transfer and low cost, making it widely applicable in sensors, fuel cells, and electromagnetic shielding. However, its conjugated π-electron system leads to rigid polymer chains, causing poor dispersibility and aggregation-prone domains [16–18]. Fortunately, biomass collagen fibers (CFs) with rich active groups (–OH, C═O, and –NH), the component units of natural skin, feature intrinsic (fiber slipping and deformation) and extrinsic (crack deflection and crack bridging) toughening properties due to their hierarchical structure [19–23]. Thus, CFs are used as biomass templates and coated with PPy by in situ oxidative polymerization to improve the dispersity of PPy in water and enhance the conductivity of composite films. To immobilize PPy nanoparticles on CFs, the CFs were first coated with bayberry tannin (BT), a natural polyphenol used in biomaterial functionalization [24–26]. Iron(III) chloride (FeCl3) was used as an oxidant to initiate the polymerization of PPy on the CFs surface [27]. Meanwhile, the macromolecular complexes of BT with iron ions (Fe3+) formed by coordination action as bio-adhesives to facilitate the interactions between PPy and CFs, so as to improve the stability of PPy on the CFs [28–30]. Therefore, the enhanced flexibility, dispersity, and conductivity of these PPy–CFs-BT compared with conventional PPy were achieved by improving interfacial interactions between CFs and PPy.

Herein, inspired by the multiple functions of natural skin, PPy–CFs-BT as conductive network were incorporated into a PVA–PEO composite to construct a versatile film, abbreviated as PCBPP. It is expected that the interfacial interactions between PVA and PEO are also improved due to the synergy of Fe3+ chelation and the hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) between the –OH groups of PVA, PEO, CFs-BT, and amino groups of PPy chains. The PCBPP film with flexibility and conductivity was capable of sensing both large (e.g., bending of elbow) and subtle (e.g., swallowing) body motions, which enabled it to simulate the tactual sensation of human skin. Moreover, the PCBPP film integrated the diverse properties including good thermal stability, water resistance, self-healing ability, adhesiveness, benign biocompatibility, and sensitive electrical signal response within a single structure and further achieved much more favorable functionalities in mimicking natural skin. As a result, this work provides a new prospect for designing CFs packed multifunctional composite film and the as-prepared PCBPP exhibits great potential for versatile applications in various wearable devices and in the field of artificial intelligence.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

CFs were provided by Hebei Dongming Cattle Skins Leather Co., Ltd (Hebei, China). CFs were washed with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol, and then filtered. After drying, the CFs were milled using a grinder and screened by 1 mm mesh. As shown in Figure S1a–c, the resultant CFs show the hierarchically fibrous structure and the typical D-period structure formed by a quarter-staggered end-overlap fashion of collagen molecules [31]. BT was provided by Baise Tianxing Plant Technology Co., Ltd (Guangxi, China). Glutaraldehyde, pyrrole, and FeCl3·6H2O were obtained from Kelong Chemical Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). PVA and PEO were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were used as received without further purification. The insulating tapes were purchased from Hebei Xinchen Electric Power Technology Co., Ltd (Hebei, China).

2.2 Preparation of BT tanned CFs (CFs-BT)

The tanning procedure of CFs with BT was performed according to the literature [32]. About 50 g of BT was dissolved in 600 mL of distilled water and mixed with 30 g of CFs. The mixture was stirred at 30°C for 4 h. After the intermediate products were collected by filtration and washed with distilled water, 600 mL of glutaraldehyde solution (20 g L−1) as cross-linking agent was added. The mixture was first stirred at 30°C for 1 h and was then continuously stirred at 50°C for 4 h. When the reaction was complete, the product was first washed with distilled water, then with ethanol, and finally dried at 60°C for 12 h. The resultant products were CFs-BT.

2.3 Preparation of PCBPP composite film (PCBPP)

CFs-BT (0.2 g) was added in 50 mL of distilled water and the mixture was stirred for 10 min in ice water bath. Then pyrrole (0.2 g) was added and stirred vigorously for 30 min. Afterward, the FeCl3·6H2O solution (0.33 g of FeCl3·6H2O as oxidant dissolved in 10 mL distilled water) was slowly dropped into the above mixture for 1 h. Then the temperature was slowly raised to 80°C and varied amount of PEO (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g) was introduced, and stirred at this temperature for 1 h. Finally, 10 g of PVA was added and stirred at 80°C for 2 h. The resultant mixture was poured into a mold and dried to obtain the PCBPP composite films, which were denoted as PCBPP-1, PCBPP-2, PCBPP-3, and PCBPP-4. For comparison, the films containing only PVA were denoted as PVA. The films without CFs-BT, pyrrole, and FeCl3·6H2O were also prepared by the same method and denoted as PVA–PEO. The films without PEO were denoted as PCBP. The films without CFs-BT were denoted as PPP. The materials containing CFs-BT, pyrrole, and FeCl3·6H2O were prepared and denoted as PPy–CFs-BT. The ingredients of the composite films are enumerated in Table S1.

2.4 Preparation of e-skin device

The copper foil was attached on the edge of PCBPP-3 film and two pieces of PCBPP-3 films were assembled together by insulating tape to obtain e-skin device. The device was wrapped and sealed in tape, which can be mounted on the different positions of body for motion sensing and monitoring.

2.5 Characterization

Surface morphologies of the samples were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Nova NanoSEM 450, USA) operated at 3 kV and the corresponding elemental mappings were obtained by a coupled energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Ultim Max, Oxford Instruments, UK). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific, Escalab250Xi, USA) was used for further analysis of the chemical composition of samples. The thermal stability of samples was tested by thermogravimetry analysis (Mettler TGA2, Switzerland). The measurements were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 20°C min−1 from 30 to 800°C. The water contact angles were measured by a contact angle goniometer (Kruss, DSA30, Germany). The surface roughness was measured by an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Dimension Icon, USA) at a frequency of 0.5 Hz via scanAsyst in air. The tensile properties of samples were measured using a tensile testing machine (Gotech, AI-7000 SN, China) at a crosshead speed of 100 mm min−1. Self-healing tests were performed with one drop of water (100 μL) put on the cut surface (overlapped by 1 mm) of the samples with an applied pressure of 100 kPa for 1 h.

The water resistance of the prepared samples was investigated. The sample was cut into the size of 2 mm × 2 mm and its weight was recorded as W 1. Then, the sample was soaked in 50 mL of deionized water for 24 h, taken out and wiped the water on its surface to record its weight as W 2. Finally, the above hydrous sample was dried to a constant weight and recorded its weight as W 3. The water absorption (W a) was calculated according to the following formula:

The weight loss (W l) was calculated according to the following formula:

The adhesive strengths of the PCBPP films on a variety of substrates were investigated via a lap shear testing method. The substrates with 20 mm × 20 mm × 2 mm dimensions were attached to steel plates (20 mm × 50 mm × 2 mm) using cyanoacrylate glue. Then, a PCBPP film with dimension 20 mm × 20 mm was placed between the two substrates and compressed with a 100 g weight for 5 min. Next, the adhered plates were pulled to separation at a speed of 10 mm min−1 on the tensile testing machine. The adhesion strength was calculated by the measured maximum load divided by the adhesive areas.

A standard four-point probe method was applied for measuring the conductance of samples. Current changes were recorded by a CHI660E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, Inc., China) with an applied DC voltage of 3 V. The force value was applied by an ESM303-COMP mechanical measurement system (Mark-10 Corporation, USA).

RAW264.7 macrophage cells were cultured on PBS culture medium containing as-prepared films with 5 mm × 5 mm squares for 12 h to assess the basic cytocompatibility of these materials and to evaluate their potential applications for biomaterials.

3 Results and discussion

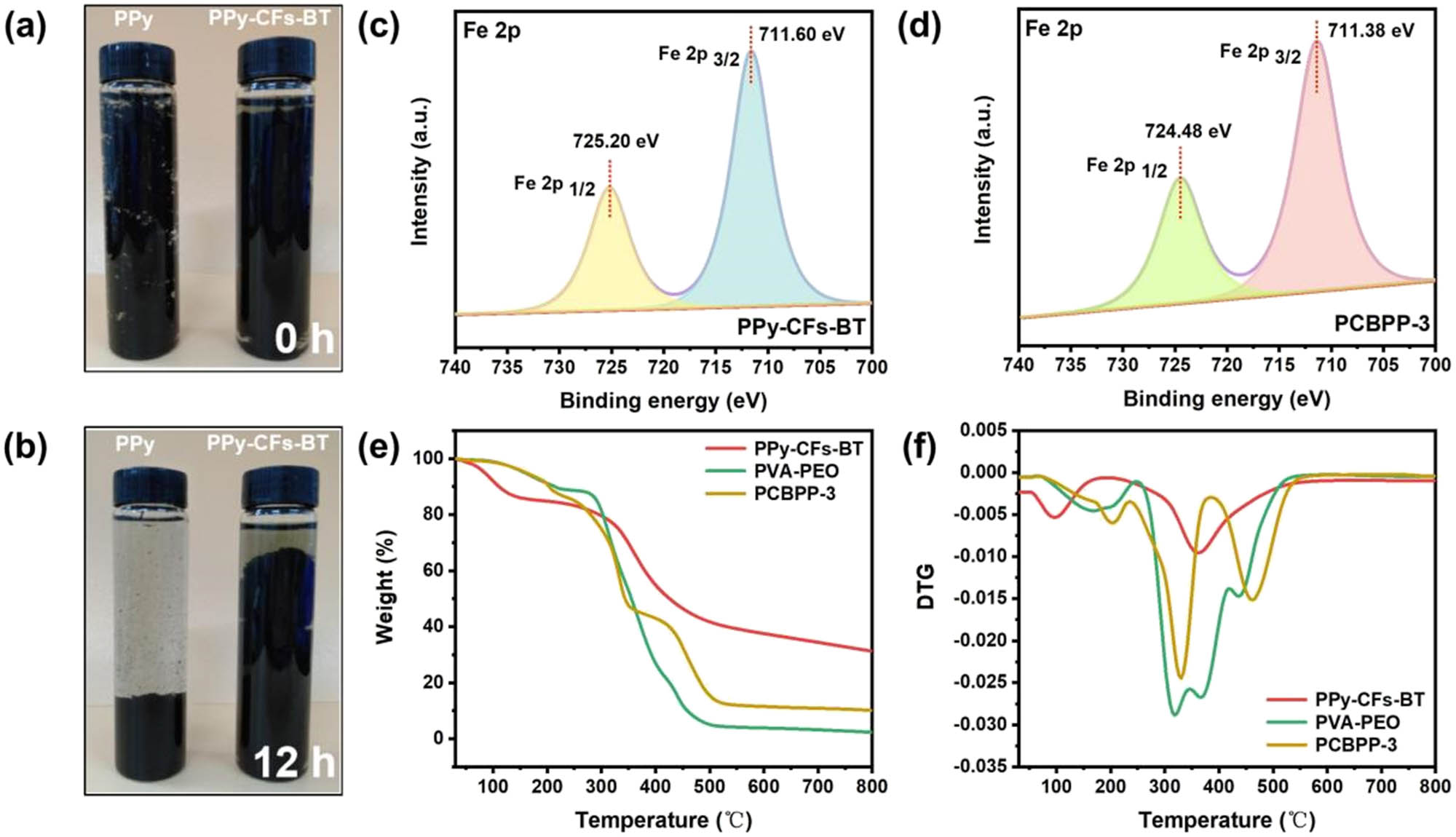

Figure 1a–d is the schematic illustration showing the fabrication of PCBPP (details in Section 2). The CFs were first modified with BT by tanning procedure to obtain the CFs-BT, which were further in situ grown with PPy using FeCl3 as oxidant to prepare the PPy–CFs-BT. The obtained PPy–CFs-BT was mixed with the solution of PVA and PEO, followed by drying to prepare the PCBPP composite film (PCBPP). Figure 1e–g and Figure S2 show the digital photo and the microstructures of PPy, CFs, CFs-BT, and PPy–CFs-BT, respectively. It can be found that the pure PPy nanoparticles show approximate spherical shape and are densely agglomerated. CFs still retain the hierarchically fibrous structure after tanned with BT and in situ growth with PPy, resulting in the change of CFs from light blue to brown, and to black, which confirms the successful growth of PPy on CFs-BT. As seen in Figure 1g, the spherical PPy nanoparticles grow along the hierarchical CFs template to alleviate agglomeration, which will be beneficial to improve the composite film with good enhanced conductivity. The comparison of Figure 2a and b also further demonstrates that the CFs as biomass templates obviously reduce the agglomeration of PPy and improve its dispersity. The surface microstructures of PVA, PVA–PEO, PCBP, and PCBPP-3 films are shown in Figure 1h and Figure S3. Particularly, the pure PVA film exhibits flat and smooth surface, while a relatively flat structure of PVA–PEO is observed, which is due to the heterogeneous mixture of PVA and PEO. In the presence of PPy–CFs-BT, relatively rough surface and homogeneous dispersion of PPy–CFs-BT are observed in PCBP and PCBPP-3 films, which is the combined result of H-bonds and coordination bonds. SEM-mapping analyses manifest that Fe elements are well scattered on the PCBPP-3 and the content of Fe elements is relatively less than that of C, N, and O elements (Figure 1h–l). The XPS survey scan spectrum of the PCBPP-3 shows the characteristic peaks of C, N, O, and Fe elements and little existence of O and Fe elements (Figure S4). The Fe XPS spectrum of PCBPP-3 is fitted into two peaks, which are assigned to the Fe 2p 1/2 (724.48 eV) and Fe 2p 3/2 (711.38 eV), respectively (Figure 2d), similar with those of PPy–CFs-BT (Figure 2c). The fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrum of PCBPP-3 was also provided to analyze of the chemical bonds and functional groups of the composites. As shown in Figure S5, the FTIR spectrum of PCBPP-3 shows the characteristic peaks of –OH, –CH2, and –C═C– located at 3,259, 2,940, and 1,653 cm−1, respectively. The above experimental results confirm the successful integration of PPy–CFs-BT in the PCBPP-3. The thermogravimetric analysis was carried out to identify the thermal stability of the as-prepared samples. As shown in Figure 2e and f, the weight loss 10% of PCBPP-3 starts at 202°C, which exhibits excellent thermal stability. The weight loss 10% of PPy–CFs-BT and PVA–PEO starts at 110 and 210°C, respectively. The above results show that the introduction of PPy–CFs-BT into PVA–PEO has little effect on the thermal stability.

(a)–(d) Schematic illustration showing the fabrication of PCBPP and FESEM images of (e) CFs, (f) CFs-BT, and (g) PPy–CFs-BT (insets in e–g show the digital photos of CFs, CFs-BT, and PPy–CFs-BT, respectively. (h)–(l) FESEM-EDS mapping images of PCBPP-3.

(a) and (b) Digital photos of PPy and Ppy–CFs-BT during the 12 h of static placemen, the Fe XPS spectra of (c) Ppy–CFs-BT and (d) PCBPP-3, (e) TGA and (f) DTG curves of PPy–CFs-BT, PVA–PEO, and PCBPP-3.

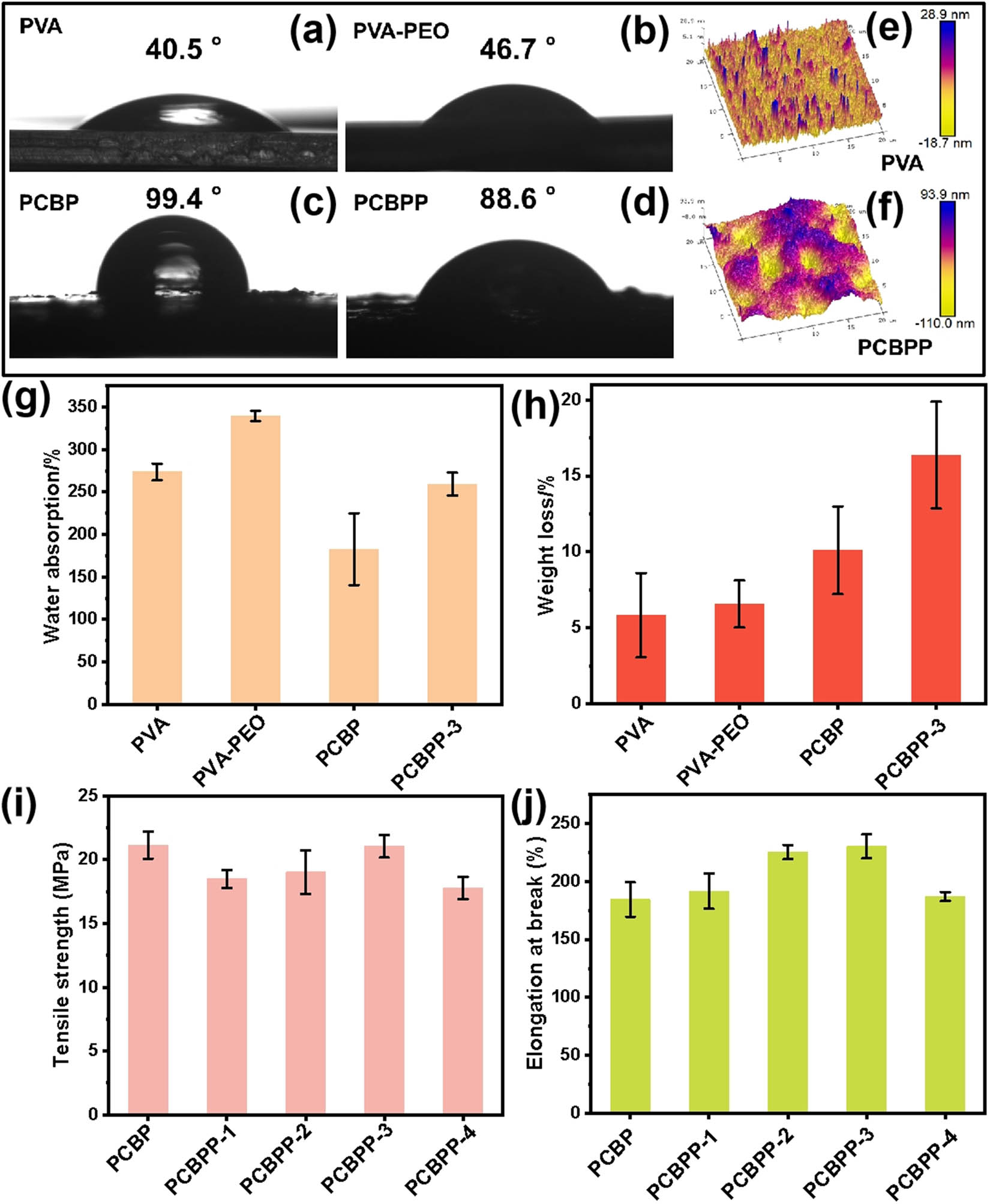

The contact angle tests were carried out to evaluate the hydrophilicity of the as-prepared films (PVA, PVA–PEO, PCBP, and PCBPP). As shown in Figure 3a–d, the PCBP and PCBPP composite films exhibit the contact angle of 99.4° and 88.6°, respectively. In contrast, the PVA and PVA–PEO films exhibit lower contact angle of 40.5° and 46.7°, respectively. These results show that the addition of PPy–CFs-BT decreases the hydrophilicity, which is related to the increase of surface roughness from 3.34 nm of PVA film to 29.5 nm of PCBPP film (Figure 3e and f). Due to the difference of hydrophilicity, the PVA, PVA–PEO, PCBP, and PCBPP films exhibit different water absorption. As shown in Figure 3g, the PCBP and PCBPP composite films show the water absorption of 183 and 259%, respectively, which is significantly lower than those of PVA (274%) and PVA–PEO (339%) films. On the contrary, the PCBP (10.1%) and PCBPP (16.4%) composite films show higher weight loss than those of PVA (5.83%) and PVA–PEO (6.57%) films, which might be attributed to that the addition of PPy–CFs-BT decreases the intermolecular bonding force of original PVA and PVA–PEO films (Figure 3h). The above experimental results show that the as-prepared PCBPP composite films feature with good water resistance.

Contact angle of (a) PVA, (b) PVA–PEO, (c) PCBP, and (d) PCBPP-3, the 3D peak force tapping mode AFM images of (e) PVA and (f) PCBPP-3, (g) the water absorption and (h) weight loss of PVA, PVA–PEO, PCBP, and PCBPP-3, (i) the tensile strength and (j) elongation at break of PCBP, PCBPP-1, PCBPP-2, PCBPP-3, and PCBPP-4.

For the as-prepared PCBPP composite films, the capabilities of mechanical tensile tolerance are significantly influenced by the content of PEO. As shown in Figure 3i, the tensile strength of PCBPP exhibits a trend of decreasing, then increasing, and subsequently decreasing again along with the increase of PEO content. In contrast, the elongation at break of PCBPP exhibits a trend of first increasing and then decreasing along with the increase of PEO content (Figure 3j). The PCBPP-3 simultaneously shows considerable tensile strength and elongation at break, which are 21.1 MPa and 230%, respectively. The PCBP film without PEO shows comparable tensile strength (21.2 MPa) and lower elongation at break (184%). Obviously, the integration of PEO improves the tensile property of PCBPP composite films, which provides the basis for the design of e-skin device.

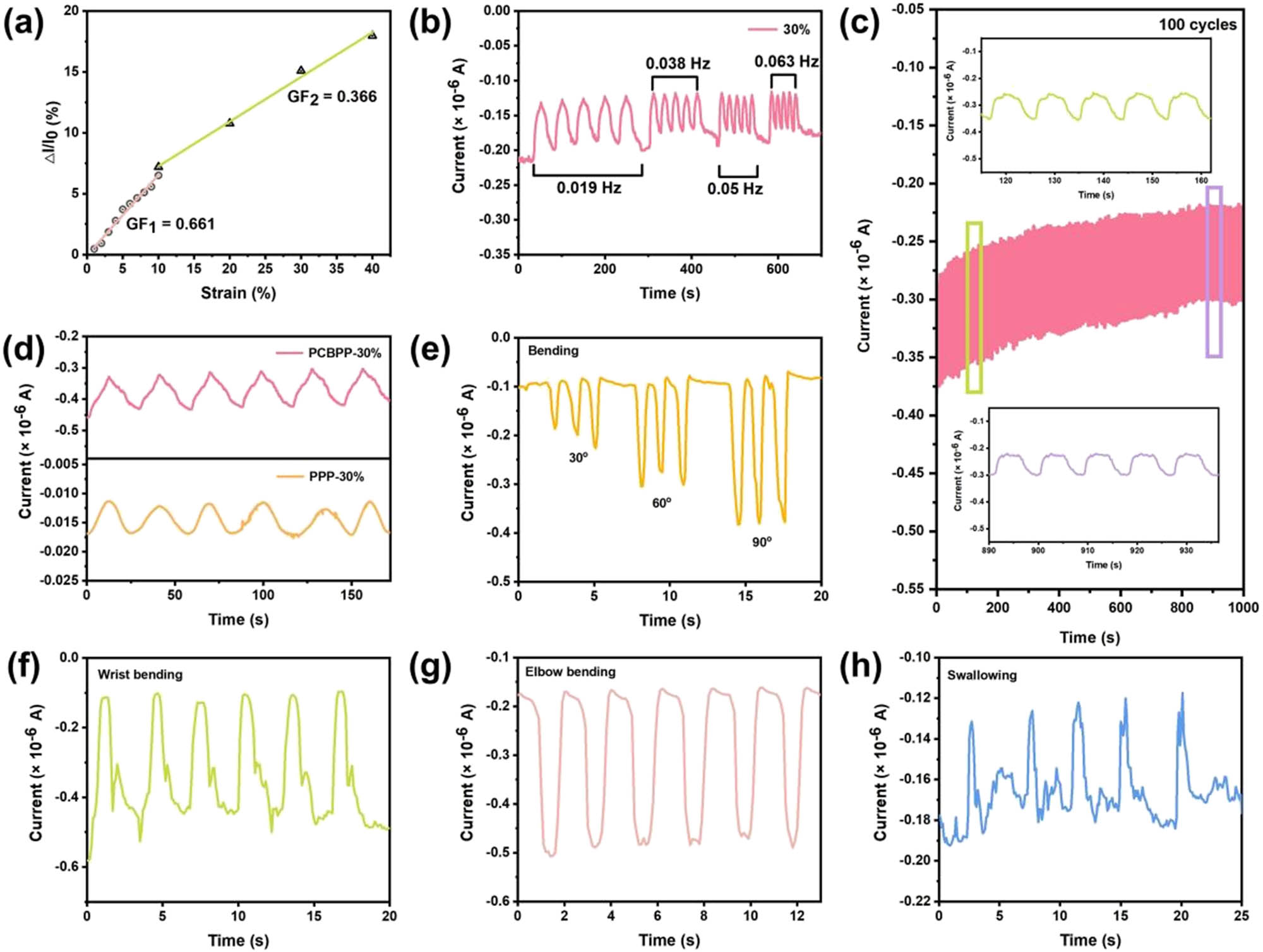

The as-prepared PCBPP-3 film exhibits the conductance of 3.11 × 10−3 S m−1 due to the existence of conductive PPy-coated CFs. The copper foil was attached on the edge of PCBPP-3 film and two pieces of PCBPP-3 films were assembled together to obtain e-skin device. The e-skin exhibits strain-dependent electrical properties, which are capable of monitoring different strain stimuli. We measured the gauge factor (GF) of e-skin by applying different strain intensities on it, ranging from 1 to 40%. As shown in Figure 4a, there is a linear segment of ΔI/I 0 versus strain. The GF value of e-skin was calculated as GF = d(ΔI/I 0)/dS, where S, I 0, and ΔI are the applied strain, the initial current, and the change of current after applying strain, respectively. The GF values of e-skin were determined to be 0.661 and 0.366 in the strain range of 1–10% and 10–40%, respectively. The e-skin shows similar electrical signal amplitude under the strain stimuli of 30% with varied frequencies (0.019–0.063 Hz), which exhibits the frequency stability on same strain (Figure 4b). More importantly, the e-skin is able to distinguish different strain intensities and shows varied amplitude electrical signals in range of 2–40% (Figure S6). The sensing stability of e-skin was further evaluated by applying repetitive loading/unloading strain of 30% for 100 cycles, and it was found that the e-skin provided excellent stability (Figure 4c). The sensing response to the strain of 30% of PCBPP and PPP was compared. As shown in Figure 4d, the PCBPP prepared e-skin exhibits wider current signal change than that of PPP, which further demonstrated the importance of CFs as biomass template to enhance the conductivity. As shown in Figure 4e, the PCBPP prepared e-skin is able to distinguish different bending angle stimuli. The PCBPP prepared e-skin was also applicable for monitoring the movements of the human body, including wrist bending (Figure 4f), elbow bending (Figure 4g), and swallowing (Figure 4h). The sensing mechanism of e-skin device is explained as follow. When stretched, the PVA matrix deforms, disrupting the conductive fiber pathways, increasing the resistance. CFs enhance flexibility and interfacial adhesion, ensuring uniform strain distribution. Reversible deformation realigns conductive networks upon relaxation, restoring conductivity. The resistance change correlates with strain, enabling real-time sensing.

(a) Strain sensitivity of PCBPP prepared e-skin, (b) I–t curve of e-skin under the strain stimuli of 30% with varied frequencies (0.019–0.063 Hz), (c) 100 cycles of repetitive loading/unloading strain of 30% (inset shows I–t curve of e-skin in randomly selected ten cycles), (d) I–t curves of PCBPP and PPP prepared e-skin under the strain stimuli of 30%, (e)–(h) I–t curves of PCBPP prepared e-skin under (e) different bending angles, (f) wrist bending, (g) elbow bending, and (h) swallowing.

The as-prepared PCBPP composite film exhibits self-healing ability owing to the hydrogen bond interaction. As shown in Figure 5a and b, the tensile strength and at break elongation of pristine PCBPP are 21.1 MPa and 230%, respectively. After being cut off, the self-healed PCBPP exhibits slightly decreased tensile strength (18.5 MPa) and significantly decreased at break elongation (119%). Figure 5c–f shows the digital photos of PCBPP during self-healing. The self-healed PCBPP still remains with good flexibility. More importantly, the self-healed PCBPP shows same-amplitude electrical signal as the pristine PCBPP under the strain stimuli of 6%, which confirms the recoverable sensibility of PCBPP (Figure 5g). The self-healed PCBPP was connected in a circuit and it still lights up an LED light bulb, which further confirms the good self-healing ability of PCBPP (Figure 5h).

(a) Tensile strength and (b) at break elongation of PCBPP before and after being cut off, (c)–(f) digital photos of PCBPP during self-healing, (g) I–t curves of PCBPP prepared e-skin before and after being cut off under the strain stimuli of 6%, and (h) LED light bulb illuminated by the self-healed PCBPP.

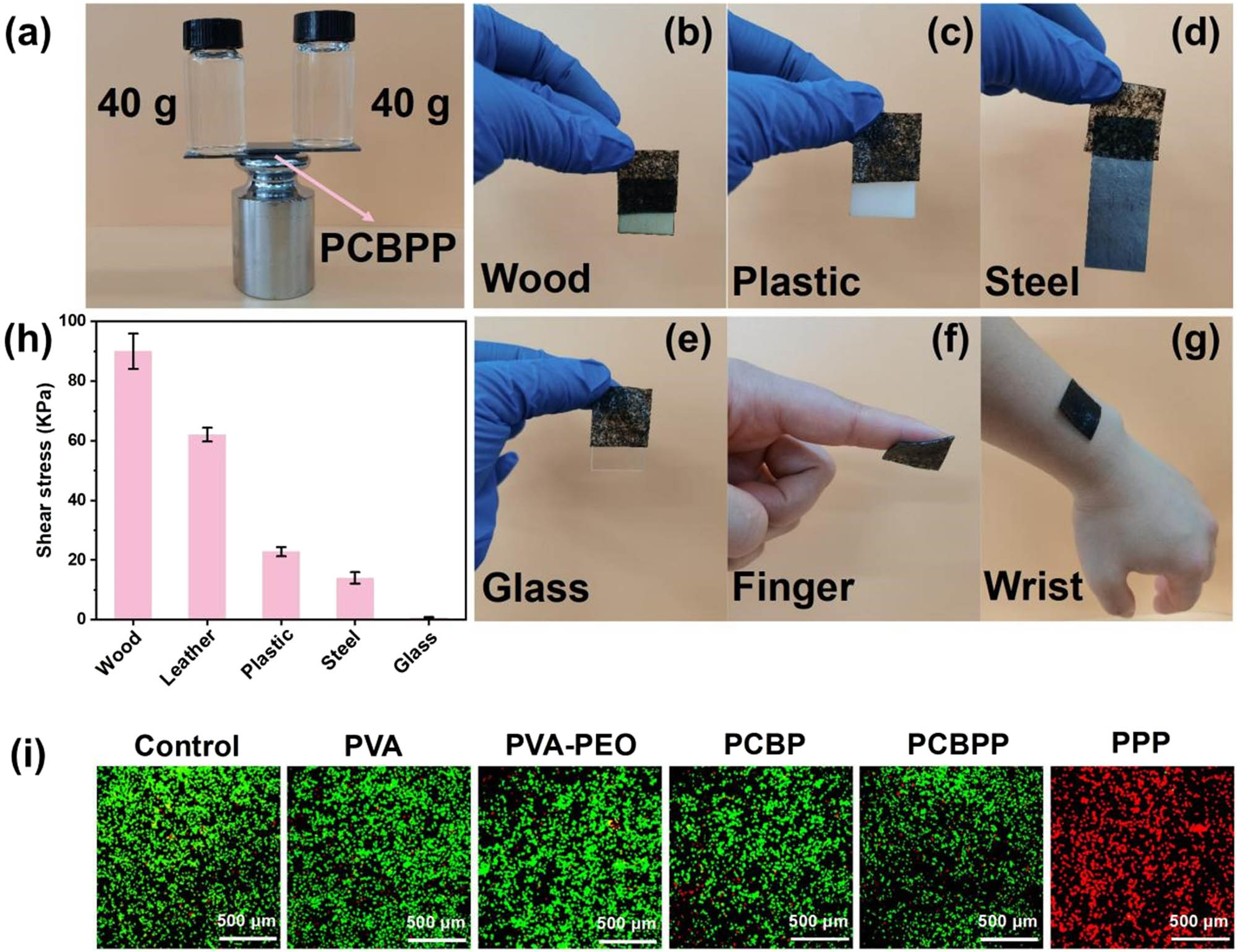

Benefitting from the abundant catechol groups of BT and the multiple hydrogen bond properties of PVA and PEO, the as-prepared PCBPP exhibits remarkable adhesion. As shown in Figure 6a, the PCBPP as adhesive is able to bond two steel plates and support 80 g of weight. In addition, the PCBPP is capable of maintaining a tight fit and seamless connection with wood, plastic, steel, glass, finger, and wrist (Figure 6b–g). The tensile adhesion tests show that the shear stress of PCBPP with wood, leather, plastic, steel, and glass is 90.0, 62.1, 22.8, 14.0, and 0.733 kPa, respectively (Figure 6h). Therefore, the PCBPP exhibits outstanding adhesiveness, which is capable of providing a viable solution for stable and reliable sensor fitting. Moreover, the PCBPP also exhibits good cytocompatibility. As shown in Figure 6i, the cell viability of PCBPP and PCBP remains with no little change compared to the control, PVA, and PVA–PEO. However, the cell viability of PPP suffers from remarkable decrease. The above experimental results demonstrate that the CFs as biomass template for PPy provide good biocompatibility.

(a) Digital photos of PCBPP as adhesive to support 80 g of weight, (b)–(g) digital photos of PCBPP as adhesive to adhere with wood, plastic, steel, glass, finger, and wrist, respectively, (h) shear stress of PCBPP with wood, leather, plastic, steel, and glass, (i) laser confocal microscope images of RAW264.7 macrophage cells after 12 h of co-culture in the control group, PVA, PVA–PEO, PCBP, PCBPP, and PPP, respectively.

4 Conclusions

We have successfully fabricated the PCBPP composite film by utilizing CFs as biomass templates to immobilize and stabilize the PPy nanoparticles, followed by being filled into the mixture of PVA and PEO. Specifically, the PPy was in situ grown on the CFs using FeCl3 as oxidant and the complex of BT and Fe3+ as adhesive. The obtained PPy–CFs-BT improved the dispersity of PPy and its conductivity. The as-prepared PCBPP composite film exhibited good thermal stability, water resistance, self-healing ability, adhesiveness, benign biocompatibility, and sensitive electrical signal response within a single structure, realized much more favorable functionalities in mimicking natural skin. More importantly, the PCBPP prepared e-skin was able to distinguish different strain intensities and monitor the movements of the human body, including wrist bending, elbow bending, and swallowing. The self-healed PCBPP prepared e-skin exhibited the recoverable sensitivity. Therefore, we have provided a new prospect for designing CFs packed multifunctional composite film and the as-prepared PCBPP exhibits great potential for versatile applications in various wearable devices and in the field of artificial intelligence.

-

Funding information: This study was financially supported by the Open Fund Project of Innovation Center for Chenguang High Performance Fluorine Material (SCFY2402).

-

Author contributions: Y.N. Wang: involved in methodology, conceptualization, project management, writing – review and editing, and funding acquisition; G.G. Niku: performed data collation; H. Chen: methodology; and Y.J. Wang: methodology, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Xiong Y, Han J, Wang YF, Wang ZL, Sun QJ. Emerging iontronic sensing: materials, mechanisms, and applications. Research. 2022;2022:9867378.10.34133/2022/9867378Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Zhou LT, Li YC, Xiao JC, Chen SW, Tu Q, Yuan MS, et al. Liquid metal-doped conductive hydrogel for construction of multifunctional sensors. Anal Chem. 2023;95:3811–20.10.1021/acs.analchem.2c05118Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Li T, Li Y, Zhang T. Materials, structures, and functions for flexible and stretchable biomimetic sensors. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52(2):288–96.10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00497Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Wu XD, Ahmed M, Khan Y, Payne ME, Zhu J, Lu CH, et al. A potentiometric mechanotransduction mechanism for novel electronic skins. Sci Adv. 2020;6(30):eaba1062.10.1126/sciadv.aba1062Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Iravani S, Rabiee N, Makvandi P. Advancements in MXene-based composites for electronic skins. J Mater Chem B. 2024;12(4):895–915.10.1039/D3TB02247ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Lv X, Tian S, Liu C, Luo LL, Shao ZB, Sun SL. Tough, antibacterial and self-healing ionic liquid/multiwalled carbon nanotube hydrogels as elements to produce flexible strain sensors for monitoring human motion. Eur Polym J. 2021;160:110779.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110779Search in Google Scholar

[7] Li CZ, Li XB, Zhang ED, Shi J, Kong CG, Ren JR, et al. A novel highly stretchable, freeze-resistant, and recyclable organohydrogel by waterborne polyurethane and DMSO-H2O binary solvent enhanced for multifunctional sensors. Polymer. 2024;290:126489.10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126489Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yu JY, Gu YQ, Ren Y, Lou QN, Ding YT, Qiu QF, et al. Characterization and research progress of hydrogel conductive materials for energy storage components. J Energy Storage. 2024;101:113813.10.1016/j.est.2024.113813Search in Google Scholar

[9] Liao H, Guo X, Wan P, Yu G. Conductive MXene nanocomposite organohydrogel for flexible, healable, low‐temperature tolerant strain sensors. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1904507.10.1002/adfm.201904507Search in Google Scholar

[10] Krull SM, Patel HV, Li M, Bilgili E, Davé RN. Critical material attributes (CMAs) of strip films loaded with poorly water-soluble drug nanoparticles: I. Impact of plasticizer on film properties and dissolution. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;92:146–55.10.1016/j.ejps.2016.07.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Cheng H, Devi RK, Huang KY, Ganesan M, Ravi SK, Lin CC. Highly biocompatible antibacterial hydrogel for wearable sensing of macro and microscale human body motions. Small. 2024;20(37):2401201.10.1002/smll.202401201Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Wen LS, Xie DH, Wu J, Liang YT, Zhang YC, Li JF, et al. Humidity-/sweat-sensitive electronic skin with antibacterial, antioxidation, and ultraviolet-proof functions constructed by a cross-linked network. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(50):56074–86.10.1021/acsami.2c15876Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Yang M, Wang Z, Li M, Yin Z, Butt HA. The synthesis, mechanisms, and additives for bio‐compatible polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels: a review on current advances, trends, and future outlook. J Vinyl Addit Techn. 2023;29(6):939–59.10.1002/vnl.21962Search in Google Scholar

[14] Canossa S, Wuttke S. Functionalization chemistry of porous materials. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:2003875.10.1002/adfm.202003875Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lawoko M, Berglund L, Johansson M. Lignin as a renewable substrate for polymers: from molecular understanding and Isolation to targeted applications. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021;9(16):5481–5.10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c01741Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang RJ, Tan ZQ, Zhong WB, Liu K, Li MF, Chen YL, et al. Polypyrrole (PPy) attached on porous conductive sponge derived from carbonized graphene oxide coated polyurethane (PU) and its application in pressure sensor. Compos Commun. 2020;22:100426.10.1016/j.coco.2020.100426Search in Google Scholar

[17] Kaur G, Toppo AE, Garima Mehta SK, Sharma S. Synthesis of polypyrrole (PPY) functionalized halloysite nanotubes (HNTs): an electrochemical sensor for ibuprofen. Appl Surf Sci. 2024;652:159280.10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.159280Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jain R, Jadon N, Pawaiya A. Polypyrrole based next generation electrochemical sensors and biosensors: a review. Trac-Trend Anal Chem. 2017;97:363–73.10.1016/j.trac.2017.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liu XH, Zheng MH, Wang XC, Luo XM, Hou MD, Yue O. Biofabrication and characterization of collagens with different hierarchical architectures. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6(1):739–48.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01252Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Xiao HZ, Wang YJ, Hao BC, Cao YR, Cui YW, Huang X, et al. Collagen fiber‐based advanced separation materials: recent developments and future perspectives. Adv Mater. 2022;34(46):2107891.10.1002/adma.202107891Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Wen QL, Wu XT, Xu WX, Shi B. Effects of dispersion and fixation of collagen fiber network on its flame retardancy. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2020;175:109122.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2020.109122Search in Google Scholar

[22] Cao YR, Xiao HZ, Zheng W, Wang YJ, Wang YN, Huang X, et al. Green synthesis of environmentally benign collagen fibers-derived hierarchically structured amphiphilic composite fibers for high-flux dual separation of emulsion. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(1):107067.10.1016/j.jece.2021.107067Search in Google Scholar

[23] Wang YN, Hao BC, Wang YJ, Wei YJ, Huang X, Shi B. Soft while strong mechanical shock tolerable e-skins. J Mater Chem A. 2022;10(15):8186–94.10.1039/D1TA10746ASearch in Google Scholar

[24] Dang XG, Fu YT, Wang XC. Versatile biomass-based injectable photothermal hydrogel for integrated regenerative wound healing and skin bioelectronics. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:2405745.10.1002/adfm.202405745Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wang YN, Zhang JW, Zhao Y, Pu MJ, Song XY, Yu LM, et al. Innovations and challenges of polyphenol-based smart drug delivery systems. Nano Res. 2022;15:8156–84.10.1007/s12274-022-4430-3Search in Google Scholar

[26] Peng Y, Huang H, Wu YL, Jia SH, Wang F, Ma J, et al. Plant tannin modified chitosan microfibers for efficient adsorptive removal of Pb2+ at low concentration. Ind Crop Prod. 2021;168:113608.10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113608Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ye XX, Ke L, Wang YP, Gao KY, Cui YW, Wang XL, et al. Polyphenolic‐chemistry‐enabled, mechanically robust, flame resistant and superhydrophobic membrane for separation of mixed surfactant‐stabilized emulsions. Chem Eur J. 2018;24:10953–8.10.1002/chem.201800956Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Xie ZF, Wang ML, Deng YS, Li JN, Li JT, Pang WD, et al. Acute toxicity of eucalyptus leachate tannins to zebrafish and the mitigation effect of Fe3+ on tannin toxicity. Ecotox Environ Safe. 2022;229:113077.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.113077Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Liu PY, Miao ZH, Li K, Yang HJ, Zhen L, Xu CY. Biocompatible Fe3+–TA coordination complex with high photothermal conversion efficiency for ablation of cancer cells. Colloid Surf B. 2018;167:183–90.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.03.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Li WH, Han S, Huang HC, McClements DJ, Chen S, Ma CC, et al. Fabrication, characterization, and application of pea protein isolate-polyphenol-iron complexes with antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;150:109729.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.109729Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sant S, Coutinho DF, Gaharwar AK, Neves NM, Reis RL, Gomes ME, et al. Self‐assembled hydrogel fiber bundles from oppositely charged polyelectrolytes mimic micro‐/nanoscale hierarchy of collagen. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1606273.10.1002/adfm.201606273Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Liao XP, Zhang MN, Shi B. Collagen-fiber-immobilized tannins and their adsorption of Au(III). Ind Eng Chem Res. 2004;43(9):2222–7.10.1021/ie0340894Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)