Abstract

Ceramizable silicone rubber (SR) composites, which transform into high-strength ceramics at high temperatures, are crucial for fire-resistant applications. This study investigates the synergistic effects of ammonium polyphosphate (APP) and zinc borate (ZB) on the mechanical properties and thermal stability of ceramizable SR composites. The results show that the addition of APP and ZB significantly enhances the flexural strength and thermal stability of the composites at high temperatures, while maintaining their elasticity and electrical insulation properties at room temperature. The synergistic effect of APP and ZB leads to the formation of a liquid phase at high temperatures, which binds the residual materials and promotes the formation of mullite and aluminum borate crystals, resulting in a high-strength ceramic matrix. The composite exhibits excellent elongation at break (492.36%) and electrical insulation (volume resistance of 1.89 × 1014 Ω m) at room temperature, and a flexural strength of 39.47 MPa after heat treatment at 1,000°C.

1 Introduction

Ceramizable silicone rubber (SR) composites, which transform into high-strength ceramics at high temperatures, are crucial for fire-resistant applications in aerospace, electrical cables, and battery safety due to their excellent flexibility, elasticity, and electrical insulation properties [1–5]. The unique siloxane structure of SR gives it a higher oxygen index compared to carbon chain-based rubbers, resulting in slower heat release and flame propagation speed during combustion [6]. It does not release toxic gases, giving SR an advantage in environmental and safety applications [7,8].

Ceramizable SR composites have the elasticity and mechanical properties of SR at room temperature and transform into a ceramic body with fire-resistant and fire resistance properties at high temperatures [9,10]. This dual functionality allows ceramizable SR to provide excellent flame retardancy and self-supporting ability in high temperature environments [11–14]. However, achieving a balance between high flexural strength, thermal stability, and electrical insulation while maintaining flexibility remains a challenge. By adding ceramic-forming fillers, fluxes, and reinforcing fillers, the ceramization performance of the composite can be significantly improved [15–22]. For example, ammonium polyphosphate (APP), a halogen-free flame retardant, is widely used to improve the flame retardancy of polymer materials. Thermal decomposition releases small molecules such as NH3 and H2O, producing polyphosphates, which effectively promote the formation of ceramics and improve flame retardancy [23–25].

The role of APP is not only its flame retardant property, but also its function as a sintering aid through its thermal decomposition products at high temperature, thereby promoting the bonding between inorganic components and the ceramization process [26]. The polyphosphate and pyrophosphate formed during APP decomposition has good sintering aid properties and combines the decomposition products of mica powder (MP) and SR into a dense and strong ceramic body at high temperature. In addition, there is a synergistic effect between APP and other flux active ingredients [26–28], such as zinc borate (ZB), further improving the ceramization performance and significantly improving their mechanical strength and thermal stability [11,15,16].

To further improve the performance of ceramizable SR composites, researchers have also studied the effects of different types of fluxes and fillers. For example, silicate materials have been introduced as reinforcing fillers to increase the flexural strength and fire resistance of the composites [23,29–31]. Furthermore, the incorporation of glass powder (GP) has been shown to lower the ceramization temperature and promote the formation of a more compact ceramic structure [24,32–35]. These fillers act synergistically with APP at high temperatures and significantly improve the ceramization effect and mechanical performance of the material.

In addition, the heating speed plays an important role in the ceramization process. Lower heating rates generally contribute to the densification and uniformity of the ceramic body, thereby improving its mechanical strength and thermal stability. By controlling the heating rate, the development of the microstructure during the ceramization process can be optimized, thereby improving the mechanical properties of the final composite. High-temperature calcination experiments showed that a slower heating rate helps reduce thermal stresses and form a more uniform porous structure, which is crucial for improving the reliability of the material in practical applications [25].

In conventional ceramizable rubber materials, fillers are typically added to enhance the strength of the ceramic structure, while this often compromises the elasticity and flexibility of the rubber matrix. Previous research has made significant strides in developing novel filler materials and optimizing composite formulations to mitigate these trade-offs and improve overall material performance. However, the synergistic effect of APP and ZB on improving flexural strength has not been fully explored. This study investigates the synergistic effects of APP and ZB on the mechanical properties and thermal stability of ceramizable SR composites. The variation in bending strength of SR/MP/GP/APP/ZB composite (SMGAZ) was explored under different temperature and heating rates. The addition of small amounts of APP and ZB not only preserved the elasticity and flexibility of the rubber, but also, through their role as fluxing agents, significantly improved the bending strength of the resulting ceramic. Furthermore, X-ray diffraction (XRD) testing and characterization were employed to analyze the ceramicization mechanism. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the thermal performance evolution of SMGAZ and its potential application in high fire safety environments.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

Methyl vinyl SR (molecular weight: 540,000) was obtained from Nanjing Dongjue Company. APP was purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company and ZB was also purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company. MP (400 mesh) was purchased from Hebei Longhao Company. Hydroxyl silicone oil was purchased from McLean Reagent Company and GP was purchased from Ami Fine Powder Company. 2,4-Dichlorobenzoyl peroxide (DCBP) was purchased from Nouryon Chemicals.

2.2 Sample preparation

According to Table 1, the methyl vinyl SR and the fumed silica were repeatedly mixed in an open mill until transparent. Then MP, APP, ZB, and GP were added and mixed evenly. Finally, 1.25 g of hardener was added and mixed evenly. The SR composite was cured in a flat vulcanization machine at 120°C for 10 min to obtain the ceramizable SR samples. SMG consisted of SR, MP, and GP. SMGA consisted of SR, MP, GP, and APP. SMGAZ consisted of SR, MP, GP, APP, and ZB. SMGZ consisted of SR, MP, GP, and ZB. The numbers behind the designations represent the different ratios of APP and ZB in the composite materials (Figure 1).

Chemical compositions (wt%) of the ceramizable SR composites

| Composition | SR | SiO2 | Hydroxysilicone oil | MP | App | ZB | GP | DCBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMG | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGA | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 30 | 0 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGAZ-1 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 25 | 5 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGAZ-2 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGAZ-3 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGAZ-4 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGAZ-5 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 1.25 |

| SMGZ | 100 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 20 | 1.25 |

Ceramizable SR-based precursor vulcanization and sintering process.

2.3 Preparation of ceramic body

The samples with dimensions of 100 mm × 13 mm × 3 mm were prepared and calcined to 600, 800, and 1,000°C in a muffle furnace in air atmosphere with a heating rate of 10°C min−1 and a holding time of 30 min. For comparison, the samples were also produced at 1,000°C and with the different heating rates of 5, 10, and 20°C min−1.

2.4 Characterization

2.4.1 Mechanical properties of ceramizable SR composite

The tensile strength and elongation at break tests of the ceramizable SR composites were determined using a universal testing machine (Instron, USA) according to Chinese standard GB/T 1040.3-2006. The loading speed was 300 mm/min. The dimensions of the dumbbell samples were 115 mm (length) × 6 mm (width of narrow area) × 2 mm (thickness).

The density of the composite materials was measured using the drainage method and determined with an electron density meter (MG-300, Shanghai Guanwei Instruments Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) at room temperature. The results were also the average value of five specimens.

The shore A hardness of the composites with different contents of hydrated ZB was conducted by LX-A shore hardness tester (Shanghai Lunjie Instruments Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) at room temperature. The specimens were 6 mm thick, and the results were also the average value of five specimens.

2.4.2 Volume resistance and surface resistance of ceramizable SR composite

The insulation properties have been tested according to GB/T 31838.2 and GB/T 31838.3 standards.

2.4.3 Flexural strength of the ceramics of ceramizable SR composites

The three-point bending strength tests were carried out on an electronic tensile machine (Instron, USA) at a speed of 1 mm/min according to GB/T 6569-2006, and the results were the average value of five specimens.

2.4.4 Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of ceramizable SR composite

TGA was performed with a thermal analysis mass spectrometry (TG 209 F3Tarsus, Netzsch, Germany) up to 1,000°C with a heating rate of 10°C min−1 and a nitrogen flow of 20 mL min−1. DSC was performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC200 F3 Miai, Netzsch, Germany) up to 600°C with at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 and a nitrogen flow of 20 mL min−1.

2.4.5 Microstructure of the formed ceramics

The morphology of the ceramic body was observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI QUANTA FEG 250, USA).

2.4.6 XRD analysis of the formed ceramics

The crystalline phase of the ceramic body was captured using an X-ray diffractometer (D8-advance, Bruker, Germany) with a scan step length of 0.02, a scan speed of 0.2°/s, and a scan range of 2θ = 5–90°.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Mechanical properties of ceramizable SR composite

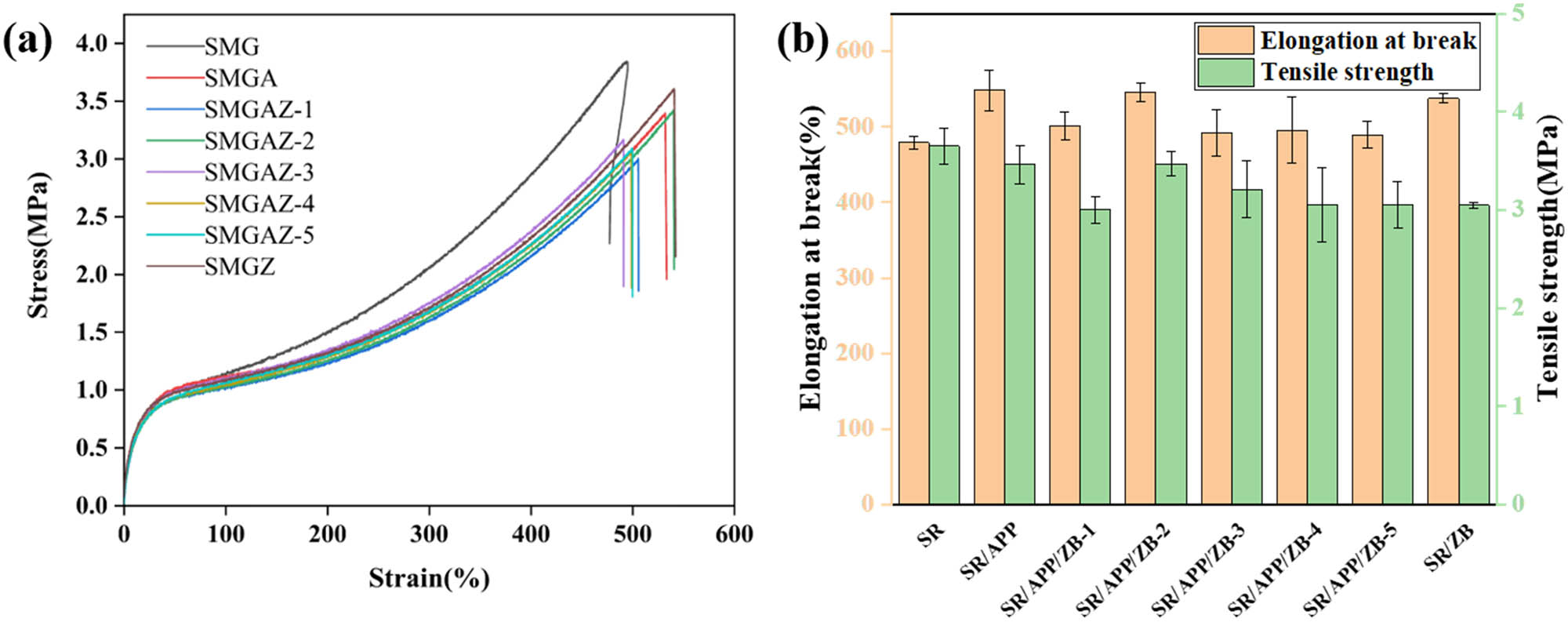

The mechanical properties of the ceramizable SR composite were determined by tensile tests. The results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The tensile strength of SR is 3.65 MPa and the elongation at break is 479.26%. By adding APP or ZB, the elongation at break of SR improved significantly, while the tensile strength decreased slightly. This is because the incorporation of fillers disrupts the cross-linking network of the SR, thereby reducing the overall structural strength of the material [36]. It is noteworthy that when APP and ZB were simultaneously added to SR in different ratios, the mechanical properties of the SR/APP/ZB system were slightly worse compared to the samples in which only APP or ZB was loaded. Furthermore, with the increase of ZB content in SR/APP/ZB, both the elongation at break and tensile strength of the composite gradually decreased. However, the elongation at break of SR/APP/ZB remained slightly higher compared to SR without APP or ZB.

Density and hardness of SR composite

| Composition | Density (g/cm3) | Hardness |

|---|---|---|

| SMG | 1.363 | 51 |

| SMGA | 1.406 | 58 |

| SMGAZ-1 | 1.417 | 56 |

| SMGAZ-2 | 1.430 | 57 |

| SMGAZ-3 | 1.434 | 57 |

| SMGAZ-4 | 1.436 | 57 |

| SMGAZ-5 | 1.450 | 57 |

| SMGZ | 1.451 | 58 |

Tensile performance of SR composite: (a) stress–strain curves and (b) tensile strength and elongation at break.

The experiments also show that the density and hardness of SR are 1.363 g/cm³ and 51 Shore A, respectively, which are significantly lower than the values after adding APP/ZB. This indicates that the density and hardness of the material increased with the total amount of filler added. In particular, as the ZB content increased, the density and hardness of the SR/APP/ZB system gradually increased, indicating that the addition of ZB can effectively improve the density and hardness of the composite. However, due to the relatively small variation in filler content, the change in density was relatively small. Overall, the addition of APP and ZB improved the elasticity of the material while maintaining its flexibility.

Table 2 shows the changes in mechanical properties of the composite when the filler content and composition ratios were adjusted. This property allows the SMGAZ composite to maintain high shape quality and structural integrity while balancing elasticity and mechanical strength, providing potential advantages for applications in high temperature environments.

3.2 Volume resistance and surface resistance of ceramizable SR composite

Figure 3 shows the volume resistance and surface resistance of various composites. Compared to the original SMG without APP and ZB, the volume resistance of the composite with APP decreased significantly. This is because APP has relatively low electrical insulation properties. The ammonium salt structure of APP had the effect of an electrolyte, which, as a conductive medium in the composite, was not conducive to insulation performance, thereby reducing the overall electrical insulation [37]. Furthermore, the surface resistance also showed a similar decreasing trend, further confirming that the addition of APP weakened the insulation properties of the composite.

Volume resistance and surface resistance of SR composite.

On the other hand, with the gradual increase in ZB content (as seen in SMGAZ-1 to SMGAZ-5), both volume resistivity and surface resistivity show an increasing trend. This is mainly because ZB has high electrical insulation properties and its introduction into the composite effectively improves the overall insulation properties of the material. In particular, for the composites with higher ZB content, both volume and surface resistivity values increase significantly, indicating that ZB has a positive influence on improving the electrical insulation properties of the composite. It is worth noting that the volume and surface resistance of SMGAZ-3 exceeded 1013 Ω cm, which meets the national standards for insulation materials. This suggests that by adjusting the proportions of APP and ZB, a ceramizable SR composite with excellent electrical insulation properties can be produced, which is suitable for high insulation application scenarios.

The addition of APP reduced the insulation performance of the composite, while ZB effectively compensated for this deficiency and significantly improved both the volume and surface resistance of the material. Therefore, by rationally designing the content ratio of APP and ZB, the electrical performance of the composite can be optimized by balancing high resistivity with good mechanical properties to meet the requirements of specific applications. Insulating properties suitable for high insulation application scenarios can be created.

3.3 Flexural strength of the ceramics of ceramizable SR composites

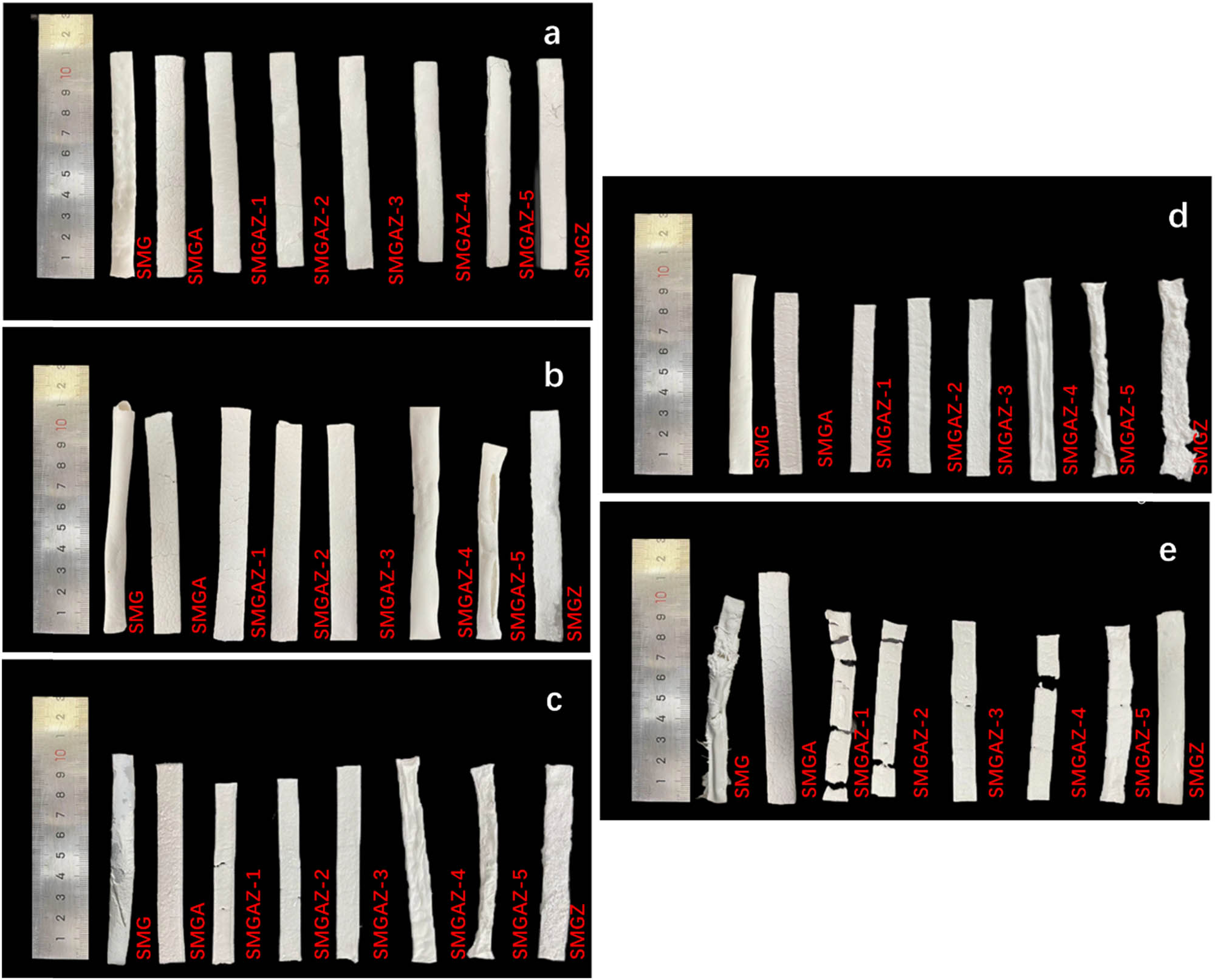

The SMG, SMGA, and SMGZ samples did not retain their original shape after firing at 1,000°C and showed significant surface deformation. In contrast, the ceramic residue of SMGAZ showed a dense appearance and a smooth white surface, indicating significantly improved dimensional stability and smoothness due to the combination of APP and ZB in the SR composite, as shown in Figure 4. The flexural strength of the SMGAZ samples calcined at different temperatures is shown in Figure 5a. In the temperature range of 600–1,000°C, the flexural strength increases with the increase in the sintering temperature. At 1,000°C, the flexural strength of the ceramic residue reaches a maximum value of 39.47 MPa and shows excellent mechanical properties.

Surface topography of the sample calcined at 600–10°C min−1 (a), 800–10°C min−1 (b), 1,000–10°C min−1 (c), 1,000–5°C min−1 (d), and 1,000–20°C min−1 (e).

Flexural strength (a) of the sample after calcination at 600–10°C min−1, 800–10°C min−1, 1,000–10°C min−1, and the flexural strength (b) at 1,000–10°C min−1, 1,000–5°C min−1, 1,000–20°C min−1.

Figure 5b shows the flexural strength of the samples calcined at 1,000°C at different heating rates. The samples with lower heating rates generally have better flexural strength. When comparing the samples produced with the heating rates of 5 and 20°C min−1, it can be seen that the flexural strength decreases slightly with the increase in the heating rate. Specifically, the flexural strength of SMGA decreases from 10.19 ± 0.97 to 8.66 ± 2.56 MPa, while the flexural strength of SMGAZ-3 decreases from 42.19 ± 2.69 23.28 ± 3.32 MPa and that of SMGAZ-2 from 45.39 ± 3.67 MPa decreases to 6.80 ± 0.89 MPa when the heating rate increased from 5 to 20°C min−1.

It is observed that at the heating rate of 20°C min−1, the lower ZB content in SMGAZ-1 resulted in insufficient liquid phase formation during ZB melting, resulting in incomplete bonding of the ceramic body and the formation of irregular blocks [14]. In contrast, SMGAZ-5, which had higher ZB content, maintained continuity but lacked the self-supporting properties provided by the gas produced during APP decomposition, resulting in significant deformations and irregular shapes, which could affect fire protection performance in practical applications.

We compared the flexural strength of SMGAZ-3 with those reported [7,11,15,25,38–40] in previous studies (Table 3). For single-filler systems, Hu et al. [11] reported a flexural strength of 9.99 MPa for the SRAAM sample with APP filler, while Song et al. [38] achieved 11.58 MPa for the SR-5 sample using ZB filler. In contrast, dual-filler systems (APP/ZB) showed improved performance: the EVA-based [25] ceramizable material reached 21.20 MPa and the polyethylene-based [39] material attained 30.50 MPa. The flexural strength of SMGAZ-3 in this work is increased by 29.4–86.2% compared with the above results; this demonstrates that the synergy between the SR matrix and the APP/ZB composite filler significantly enhances high-temperature flexural performance.

Comparison of flexural strength among different samples

| Name of the sample | Matrix | Temperature (°C) | Flexural strength (MPa) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSP-1 | SR | 1,000 | 7.16 | [7] |

| SRAAM | SR | 1,000 | 9.99 | [11] |

| SGAO | SR | 850 | 3.50 | [15] |

| EVA/MP/OMMT/APP/ZB3:4 | Ethylene-vinyl acetate | 1,000 | 21.20 | [25] |

| SR-5 | SR | 1,000 | 11.58 | [38] |

| CPE-4 | Polyethylene | 1,000 | 30.50 | [39] |

| SR-4 | SR | 1,000 | 19.70 | [40] |

| SMGAZ-3 | SR | 1,000 | 39.47 | This work |

These results indicate that the flexural strength of the samples with higher APP content tends to fluctuate significantly at high heating rate because the rapid decomposition of APP creates many irregular pores, which significantly reduces the strength of the samples. The SMGAZ-3 maintained its good shape and showed good flexural strength at various heating rates at 1,000°C, reaching 39.47 MPa, fully meeting the requirements for fire protection applications.

3.4 TGA of ceramizable SR composite

Figure 6 shows the TG and DTG curves of the samples on the thermal decomposition behavior of SMG. The thermal degradation behavior of the SMGA and SMGAZ-3 composites is similar to that of the original SMG, but both the initial decomposition temperature (T 5%) and the temperature at the maximum degradation rate (T max) are reduced. This is mainly because the added inorganic filler APP generated gases such as ammonia and water vapor during thermal decomposition, which affected the thermal stability of the SR matrix and reduced the overall stability of the composite [15]. Table 3 summarizes the TGA data for various samples, where the residual mass of SMGA at 1,000°C is 39.2%, which is lower than the residual mass of SMG at the same temperature (42.9%), further suggesting that the decomposition of APP phosphates produced gases that catalyzed and accelerated the decomposition process of the SR matrix.

TGA (a) and DTG (b) of the sample.

As summarized in Table 4, the SMGZ composite exhibited a residual mass of 49.6% at 1,000°C, representing a 6.7% increase compared to the SMG sample (42.9%). This result shows that the addition of ZB effectively slowed the thermal decomposition of SR and increased the thermal stability of the composite. Under high-temperature conditions, ZB undergoes melting and transitions into a liquid phase, forming a protective layer that acts as a thermal barrier to block external heat transfer, reduce mass loss, and increase the residual char weight [38]. In addition, the initial decomposition temperature of SMGAZ-3 was 308°C lower than that of the original SMG of 374°C, but its residual mass at 1,000°C was 46.8%, higher than that of SMG of 42.9%. The good morphology was retained, which means that the sample can maintain its structural integrity and surface smoothness after calcination at high temperatures. This shows that the synergistic effect of APP and ZB brings significant advantages in terms of morphology stability. This indicates that the simultaneous addition of APP and ZB effectively improves the thermal stability and morphology stability of the composite and avoids the problem of excessive morphology changes when adding ZB alone.

TGA data of ceramizable SR composite

| Sample | T 5% (°C) | T Max (°C) | Residues at 1,000°C (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMG | 374 | 430 | 42.9 |

| SMGA | 287 | 318 | 39.2 |

| SMGAZ-1 | 292 | 319 | 41.1 |

| SMGAZ-2 | 296 | 319 | 43.5 |

| SMGAZ-3 | 308 | 324 | 46.8 |

| SMGAZ-4 | 306 | 323 | 47.2 |

| SMGAZ-5 | 327 | 514 | 49.6 |

| SMGZ | 367 | 436 | 49.6 |

As shown in Figure 7, DSC analysis reveals significant endothermic peaks in the 300–350°C range for both SMGA and SMGAZ-3 systems containing APP, a phenomenon attributed to APP’s thermal decomposition. Given the higher APP concentration in SMGA, its endothermic peak exhibits greater intensity, indicating a positive correlation between APP’s endothermic effect and its concentration [11]. This finding aligns with the TG data, in which SMGA shows a lower initial decomposition temperature (287°C) compared to SMGAZ-3 (308°C). A comparison of the DSC curves of SMG and SMGZ systems demonstrates that the notable increase in SMGZ’s heat flow value, manifested as an upward curve shift, suggests that ZB effectively suppresses the kinetic process of thermal degradation [41]. This conclusion is corroborated by the TG test results.

DSC curve of sample.

Comparing the DSC curves of SMG and SMGZ systems, the notable increase in the heat flow value of SMGZ, manifested as an upward shift of the curve, suggests that ZB effectively suppresses the kinetic process of material thermal degradation. This conclusion is corroborated by TG test results, as the decomposition residue of SMGZ (49.8%) exceeds that of SMG (42.9%), jointly confirming the synergistic enhancement of material thermal stability by ZB.

The addition of APP lowered the initial decomposition temperature of the composite, but its synergistic effect with ZB significantly increased the residual mass and morphology stability of the material at high temperatures, thereby improving the overall thermal stability of the composite. The synergistic effect of APP and ZB plays an active role in improving the thermal stability of polymer-based materials [42]. By rationally adjusting the ratio of APP and ZB, the thermal decomposition behavior and high-temperature performance of SR composites can be significantly improved, making them suitable for applications requiring high thermal stability.

3.5 Microstructure of the formed ceramics

Figure 8 shows the cross-sectional morphology of SMGA, SMGZ, and SMGAZ-3 after calcination at 1,000°C observed using SEM. Figure 8a1 shows the cross-sectional morphology of SMGA. The SMGA sample has large and uneven pores and the internal structure is relatively loose. This phenomenon is attributed to the thermal decomposition of APP at elevated temperatures, which generates gaseous products including ammonia and water vapor. These released gases create internal pores within the composite matrix during the initial degradation stage. Subsequent calcination at 1,000°C induces structural reorganization through sintering, during which the accumulated pores coalesce and propagate toward the surface, ultimately resulting in the formation of interconnected surface cracks [43]. The lamellar structure of mica can be clearly seen in Figure 8a3, indicating that there was no reaction between APP and mica when APP was used alone.

SEM micrographs of SMGA (a1, a2, a3), SMGZ (b2, b2, b3), and SMGAZ-3 (c1, c2, c3) calcined at 1,000°C.

Figure 8b1 shows the cross-sectional morphology of SMGZ. At high temperature, the ZB melted into a liquid phase that partially filled the voids in the matrix, creating a relatively dense structure. However, not all pores could be completely filled, resulting in some residual pores of uneven size. The areas with larger pores tend to become stress concentration points, making the ceramic body more susceptible to cracking or fracture under stress [44]. Furthermore, no lamellar mica structure is observed in Figure 8b3, suggesting that ZB facilitates the decomposition of mica at high temperatures. The image of SMGAZ-3 after calcination at 1,000°C shows that its pores are more uniform and smaller compared to those of SMGA and SMGZ. This explains the superior flexural strength of this material at high temperatures.

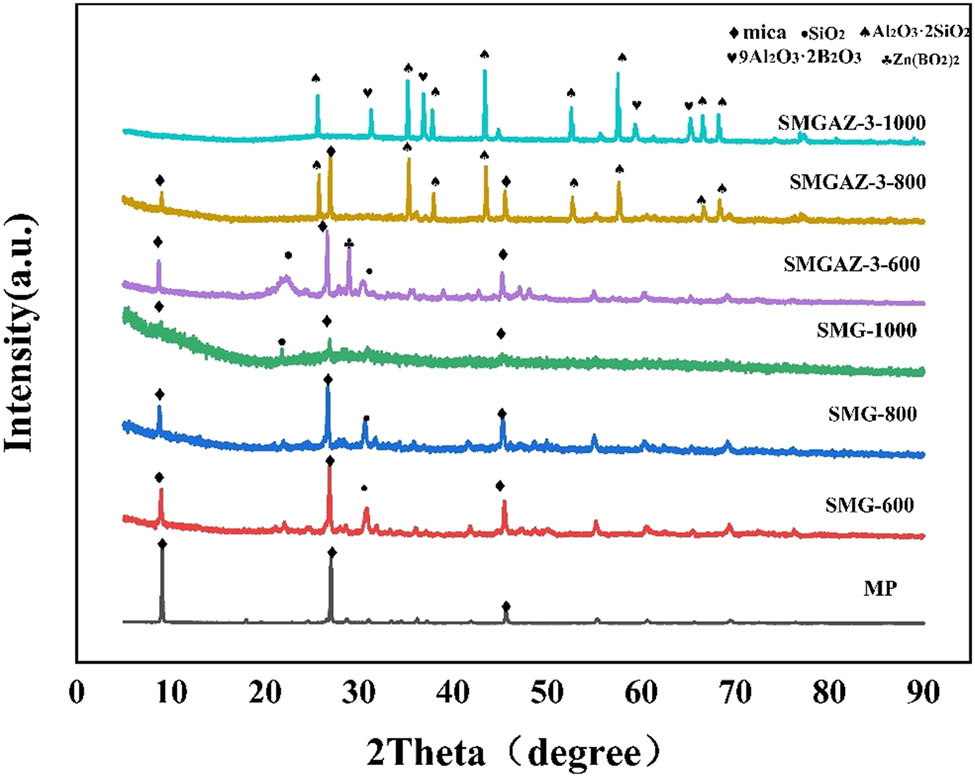

3.6 XRD of the formed ceramics

To further investigate the influence of APP and ZB on the ceramization process of SMG, XRD analysis was carried out. Figure 9 shows the XRD patterns of mica (MP), SMG, and SMGAZ-3 ceramics. The typical diffraction peaks of mica are clearly visible in the XRD pattern of MP. When the ceramization temperature is changed, no significant fluctuations in the diffraction peaks are observed in the SMG samples. After ceramization at 600, 800, and 1,000°C, the SMG samples show the diffraction peaks similar to MP as well as the additional diffraction peaks corresponding to SiO2. This phenomenon is attributed to the decomposition of SR, which leads to the formation of SiO2. The XRD analysis of SMGAZ-3 shows that the diffraction peaks of SMGAZ-3 at 600°C exhibit the presence of MP, SiO2, and ZB. SiO2 is observed in its amorphous form and the absence of phosphate peaks suggests that phosphates formed from the decomposition of polyphosphazene are in a liquid phase. At 800°C, the intensity of the MP peaks decreases, the ZB peaks disappear completely, and the SiO2 peaks disappear. At the same time, the new Al2O3·2SiO2 diffraction peaks appear, indicating that mica decomposes to form aluminum oxide, which undergoes a eutectic reaction with SiO2 formed during the decomposition of SR, resulting in the formation of Al2O3·2SiO2 crystals [45]. This explains the weakening of mica peaks, the disappearance of SiO2, and the appearance of Al2O3·2SiO2 while ZB melts and remains in a liquid phase. At 1,000°C, only the diffraction peaks of Al2O3·2SiO2 and aluminum borate are observed, indicating that mica completely decomposes into alumina with increasing temperature. Part of the aluminum oxide reacts with SiO2 to form Al2O3·2SiO2 crystals, while another part reacts with ZB to form aluminum borate, resulting in the formation of a high-strength ceramic matrix.

XRD result of the ceramics of MP, SMG, and SMGAZ-3.

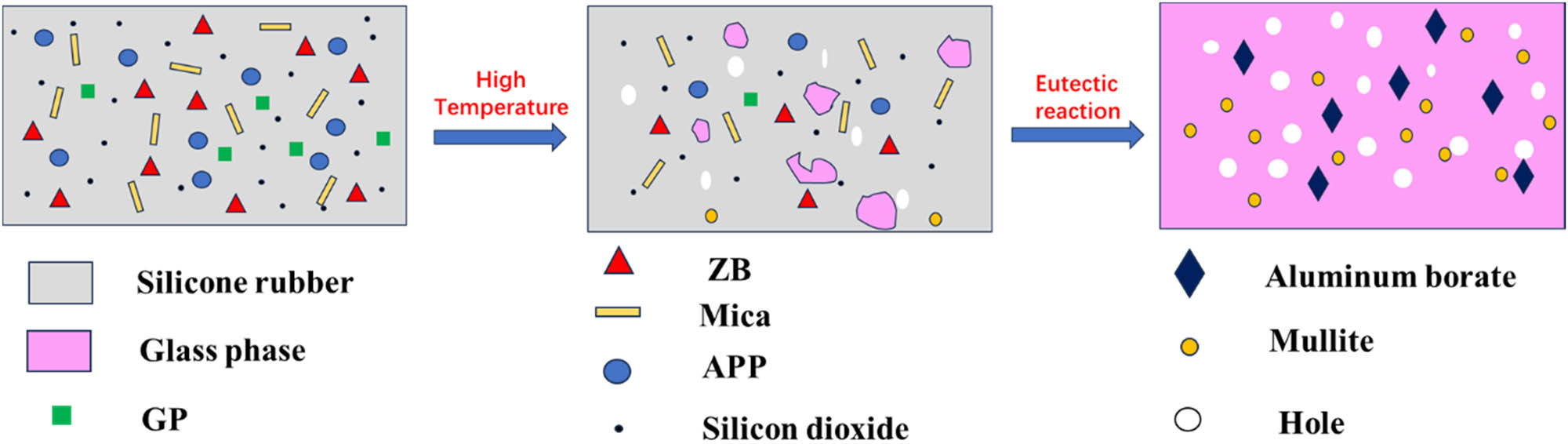

3.7 Mechanism of ceramization

As shown in Figure 10, at elevated temperature, the decomposition of SR produces SiO2 while the GP melts and forms a liquid phase. At the same time, the decomposition of APP produces polyphosphates and gases. The liquid phases of the GP and polyphosphates act as agglomerating agents, binding SiO2, MP, ZB, and other residues in the SR matrix and at the same time filling some of the pores that are created when the SR decomposes. As the temperature continues to rise, ZB melts and facilitates agglomeration, improving the cohesion of the remaining components. At about 800°C, the mica gradually decomposes and leads to a eutectic reaction between alumina and SiO2, resulting in the formation of mullite. At a temperature of 1,000°C, mica completely decomposes into aluminum oxide, which reacts with the molten ZB to form crystalline aluminum borate phases.

Ceramization process of SMGAZ.

During this process, the gases produced by the decomposition of SR and APP create pores in the matrix, which are subsequently encapsulated by the molten liquid phase. This liquid phase fills large voids and penetrates the material, effectively reducing the formation of macropores. When cooled and solidified, the liquid phase together with the crystallized phases of aluminum borate and mullite (Al2O3·2SiO2) contribute to the formation of a durable ceramic material. The synergistic interaction between the dense microstructure and the crystalline phases gives the ceramic material superior mechanical strength and thermal stability.

4 Conclusion

In summary, by incorporating APP and ZB into the SR/MP/GP system, a ceramizable SR composite material was successfully developed, which achieved a flexural strength of 39.47 MPa after heat treatment at 1,000°C. At room temperature, SMGAZ had an elongation at break of 492.36% and a volume resistance of 1.89 × 10¹⁴ Ω m, demonstrating excellent elasticity and electrical insulation properties. The comparative tests of the flexural strength of the ceramic body at different heating rates showed that a lower heating rate promotes higher flexural strength. The microstructural observations showed that the synergistic effect of APP and ZB reduced the formation of large pores, significantly improved the density of the ceramic body, and minimized stress defects, which increased its flexural strength. The ceramization mechanism shows that APP and ZB melt at high temperature and form a liquid phase that binds residual materials, followed by a typical eutectic reaction producing mullite and aluminum borate crystals, ultimately resulting in a high-strength ceramic. This study highlights the potential of APP- and ZB-modified SR for high-temperature fireproof applications, particularly in environments requiring high thermal stability and superior mechanical performance.

-

Funding information: The authors appreciate financial support from the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province, China (Grant no. 2024TSGC0522).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Shuo Li: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft. Yingqiang Feng: resources, formal analysis, supervision. Heyi Ge: resources, formal analysis, supervision, writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

[1] Shit SC, Shah P. A review on silicone rubber. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2013;36(4):355–65.10.1007/s40009-013-0150-2Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mansouri J, Burford RP, Cheng YB. Pyrolysis behaviour of silicone-based ceramifying composites. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2006;425(1–2):7–14.10.1016/j.msea.2006.03.047Search in Google Scholar

[3] Qi J, Wen Q, Zhu W. Research progress on flame-retarded silicone rubber. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 392, 2018.10.1088/1757-899X/392/3/032007Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhu C, Deng C, Cao J-Y, Wang Y-Z. An efficient flame retardant for silicone rubber: preparation and application. Polym Degrad Stab. 2015;121:42–50.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.08.008Search in Google Scholar

[5] Khattak A, Iqbal M, Amin M. Aging analysis of high voltage silicone rubber/silica nanocomposites under accelerated weathering conditions. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2017;24(5):679–89.10.1515/secm-2015-0327Search in Google Scholar

[6] Li J. Research status and development trend of ceramifiable silicone rubber composites: a brief review. Mater Res Express. 2022;9(1):024001.10.1088/2053-1591/ac4625Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhao D, Kong L, Wang J, Jiang G, Zhang J, Shen Y, et al. Ceramifiable silicone rubber composites with enhanced self-supporting and ceramifiable properties. Polymers. 2022;14(10):1944.10.3390/polym14101944Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Deng Y, Peng B, Liu Z, Du Y, Zhou S, Liu J, et al. Hygrothermal ageing performance of high temperature vulcanised silicone rubber and its degradation mechanism. High Volt. 2023;8(6):1196–205.10.1049/hve2.12347Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen D, He L, Shang S. Study on aluminum phosphate binder and related Al2O3-SiC ceramic coating. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2003;348(1–2):29–35.10.1016/S0921-5093(02)00643-3Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yu J, Qu L, Min Y, Hong L, Chen D. Preparation, characterization and fire resistance evaluation of a novel ceramizable silicone rubber composite. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139(20):50459–82.10.1002/app.52157Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hu S, Chen F, Li J-G, Shen Q, Huang Z-X, Zhang L-M. The ceramifying process and mechanical properties of silicone rubber/ammonium polyphosphate/aluminium hydroxide/mica composites. Polym Degrad Stab. 2016;126:196–203.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.02.010Search in Google Scholar

[12] Azizi S, Momen G, Ouellet Plamondon C, David E. Enhancement in electrical and thermal performance of high-temperature vulcanized silicone rubber composites for outdoor insulating applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(46):45914–30.10.1002/app.49514Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li Z, Liang W, Shan Y, Wang X, Yang K, Cui Y. Study of flame-retarded silicone rubber with ceramifiable property. Fire Mater. 2019;44(4):487–96.10.1002/fam.2802Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zhang H, Zhou S, Liang M, Zou H. Improving the transient thermal response and ablation properties of epoxy-modified silicone rubber composites by adding fluxing agent. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023;141(2):54786.10.1002/app.54786Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhao D, Liu T, Xu Y, Zhang J, Shen Y, Wang T. Investigation of the thermal degradation kinetics of ceramifiable silicone rubber-based composite. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2023;148(13):6487–99.10.1007/s10973-023-12138-9Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhou D, Luo Q, Nie G, Dong M, Du X, Liu H, et al. Preparation of high-quality zinc borate flame retardant: the existence mechanism and synergistic coupling separation of chloride ions in zinc borate. Sep Purif Technol. 2024;344:127198.10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127198Search in Google Scholar

[17] Yi G, Yu Y. Liquid silicone rubber with uniformly dispersed nanosized silica for the preparation of SiOC ceramics. Ceram Int. 2023;49(15):25980–6.10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.05.148Search in Google Scholar

[18] Huang L, Yu F, Liu Y, Lu A, Song Z, Liu W, et al. Structural analyses of the bound rubber in silica-filled silicone rubber nanocomposites reveal mechanisms of filler-rubber interaction. Compos Sci Technol. 2023;233:109905.10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109905Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zou Z, Qin Y, Xue C, Zhu D, Fu H, Deng Z, et al. Thermal properties, oxidation corrosion behavior, and the in situ ceramization mechanism of SiB6@BPR/HF composites under high-temperature corrosion. Corros Sci. 2021;193:109913.10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109913Search in Google Scholar

[20] Baharvandi HR, Hadian AM, Alizadeh A. Processing and mechanical properties of boron carbide-titanium diboride ceramic matrix composites. Appl Compos Mater. 2006;13(3):191–8.10.1007/s10443-006-9012-0Search in Google Scholar

[21] Lombardi M, Fino P, Montanaro L. Influence of ceramic particle features on the thermal behavior of PPO-matrix composites. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2014;21(1):23–8.10.1515/secm-2012-0139Search in Google Scholar

[22] Gong X, Wang T. Optimisation of the ceramic-like body for ceramifiable EVA-based composites. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2017;24(4):599–607.10.1515/secm-2015-0093Search in Google Scholar

[23] Imer MR, González M, Veiga N, Kremer C, Suescun L, Arizaga L. Synthesis, structural characterization and scalable preparation of new amino-zinc borates. Dalton Trans. 2017;46(45):15736–45.10.1039/C7DT03186FSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Üreyen ME, Kaynak E. Effect of zinc borate on flammability of PET woven fabrics. Adv Polym Technol. 2019;2019:1–13.10.1155/2019/7150736Search in Google Scholar

[25] Li Y-M, Deng C, Shi X-H, Xu B-R, Chen H, Wang Y-Z. Simultaneously improved flame retardance and ceramifiable properties of polymer-based composites via the formed crystalline phase at high temperature. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(7):7459–71.10.1021/acsami.8b21664Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Liao S-F, Deng C, Huang S-C, Cao J-Y, Wang Y-Z. An efficient halogen-free flame retardant for polyethylene: piperazinemodified ammonium polyphosphates with different structures. Chin J Polym Sci. 2016;34(11):1339–53.10.1007/s10118-016-1855-8Search in Google Scholar

[27] Dong L-P, Deng C, Li R-M, Cao Z-J, Lin L, Chen L, et al. Poly(piperazinyl phosphamide): a novel highly-efficient charring agent for an EVA/APP intumescent flame retardant system. RSC Adv. 2016;6(36):30436–44.10.1039/C6RA00164ESearch in Google Scholar

[28] Shao Z-B, Deng C, Tan Y, Yu L, Chen M-J, Chen L, et al. Ammonium polyphosphate chemically-modified with ethanolamine as an efficient intumescent flame retardant for polypropylene. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2(34):13955–65.10.1039/C4TA02778GSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Rybinski P, Syrek B, Zukowski W, Bradlo D, Imiela M, Anyszka R, et al. Impact of basalt filler on thermal and mechanical properties, as well as fire hazard, of silicone rubber composites, including ceramizable composites. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(15):2432.10.3390/ma12152432Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Si W, Ding C. An investigation on crystallization property, thermodynamics and kinetics of wollastonite glass ceramics. J Cent South Univ. 2018;25(8):1888–94.10.1007/s11771-018-3878-5Search in Google Scholar

[31] Tian Q, Kong D, Zhai T. Preparation and microstructure of machinable Al2O3/mica composite by ball milling and hot-press sintering. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2016;23(5):573–7.10.1515/secm-2014-0138Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zhou D-X, Sun R-G, Gong S-P, Hu Y-X. Low-temperature sintering and microwave dielectric properties of 3Z2B glass-Al2O3 composites. Ceram Int. 2011;37(7):2377–82.10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.03.033Search in Google Scholar

[33] Shang K, Lin GD, Jiang HJ, Jin X, Zhao J, Liu D, et al. Flame retardancy, combustion, and ceramization behavior of ceramifiable flame-retardant room temperature vulcanized silicone rubber foam. Fire Mater. 2023;47(8):1082–91.10.1002/fam.3154Search in Google Scholar

[34] Chang K, Qin Y, Zou Z, Huang Z. Mechanical properties and thermal oxygen corrosion behavior of Al2O3f-CF hybrid fiber reinforced ceramicizable phenolic resin matrix composites. Appl Compos Mater. 2023;30(6):1929–47.10.1007/s10443-023-10155-3Search in Google Scholar

[35] Xu Y, Zhao D, Fang X, Jiang G, Shen Y, Wang T. “Mica/silicate glass frit‐armored skeleton” in PDMS composite foam for improving fire-proofing performance. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023;140(23):53938.10.1002/app.53938Search in Google Scholar

[36] Yagyu H. Simulations of the effects of filler aggregation and filler-rubber bond on the elongation behavior of filled cross-linked rubber by coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Soft Mater. 2017;15(4):263–71.10.1080/1539445X.2017.1352512Search in Google Scholar

[37] Cui H, Zhang X, Liu W, Jiang Y, Wang N, Zhao H. Construction of functional epoxy resin coatings based on acid-doping polyaniline coated APP: preparation, characterization and properties. Polym Degrad Stab. 2024;225:110785.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2024.110785Search in Google Scholar

[38] Song J, Huang Z, Qin Y, Li X. Thermal decomposition and ceramifying process of ceramifiable silicone rubber composite with hydrated zinc borate. Materials. 2019;12(10):1591.10.3390/ma12101591Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Shen J, Sun Q, Gao X, Zhang J, Sheng J. Effect of ZB/APP on ceramifying properties of ceramifiable polyethylene composites at high temperatures. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2023;21(3):1905–16.10.1111/ijac.14604Search in Google Scholar

[40] Lou F, Cheng L, Li Q, Wei T, Guan X, Guo W. The combination of glass dust and glass fiber as fluxing agents for ceramifiable silicone rubber composites. RSC Adv. 2017;7(62):38805–11.10.1039/C7RA07432HSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Gillani QF, Ahmad F, Abdul Mutalib MI, Megat-Yusoff PSM, Ullah S, Messet PJ, et al. Thermal degradation and pyrolysis analysis of zinc borate reinforced intumescent fire retardant coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2018;123:82–98.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.05.007Search in Google Scholar

[42] Wang J-S, Wang G-H, Liu Y, Jiao Y-H, Liu D. Thermal stability, combustion behavior, and toxic gases in fire effluents of an intumescent flame-retarded polypropylene system. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2014;53(17):6978–84.10.1021/ie500262wSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Yan L, Zhang H, Zhou S, Zou H, Chen Y, Liang M. Improving ablation properties of liquid silicone rubber composites by in situ construction of rich-porous char layer. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;138(11):50030.10.1002/app.50030Search in Google Scholar

[44] Dong Y, Jiang H, Chen A, Yang T, Zou T, Xu D. Porous Al2O3 ceramics with spontaneously formed pores and enhanced strength prepared by indirect selective laser sintering combined with reaction bonding. Ceram Int. 2020;46(10):15159–66.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.03.052Search in Google Scholar

[45] Limpichaipanit A, Jiansirisomboon S, Tunkasiri T. Sintering temperature–microstructure–property relationships of alumina matrix composites with silicon carbide and silica additives. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2017;24(4):495–500.10.1515/secm-2014-0353Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)