Abstract

Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) are widely used in aeronautical and engineering fields because of their excellent mechanical properties and lower manufacturing costs. Among them, resin–matrix composite material is one of the widely used material types. In this study, the effect of the opening behavior of composite laminates under different hygrothermal aging conditions on their compression properties was studied. At the same time, the finite-element analysis method is used to numerically simulate the hygrothermal aging process and compression experiment. It is found that the hygroscopic behavior in the hygrothermal aging process is compounded by Fick’s second law. After the compression experiment, it is further found that aging time is the main reason affecting the mechanical properties of materials. At the same time, the failure caused by compression behavior mainly occurs laterally along the opening until brittle failure occurs.

1 Introduction

Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) are widely used in aerospace, automobile manufacturing, and other fields because of their excellent mechanical properties and lower manufacturing costs [1,2,3,4]. Among them, epoxy resin matrix composites are widely used in shipbuilding, ocean engineering, and other fields because of their better chemical properties (especially thermal stability properties). Hygrothermal environment, salt spray environment, high humidity environment, etc., are the most common aging environments for CFRP [5,6,7,8,9]. Relevant studies have shown that when the opening position is not properly deployed, CFRP will cause delamination [10], fracture [11], hole circularity surface [12], microstructure damage [13], and other damages. The appearance of these damages will inevitably affect the integrity, reliability, and safety of CFRP. Some relevant research reports point out [14] that improperly deployed opening positions can cause quality problems for up to 60% of the parts in the aircraft and affect flight safety. Based on this, the aging mechanism of CFRP in a hygrothermal environment and the effect of opening holes on mechanical properties (such as compression) are the focus of the researchers.

A considerable number of reports have demonstrated that CFRP reduces mechanical properties in hygrothermal environments [15,16]. The main reasons for the degradation of composite properties are the expansion, fracture, and hydrolysis of micro-cracks in the process of reabsorption [17]. Zhang et al. [18] studied the mechanism of hygrothermal aging of three-dimensional four-direction braided composites (3D4d-BC) with two different matrixes. The results show that the infiltration of water molecules, the chemical composition, and the temperature of the resin-based materials will cause the degradation of the matrix during the hydrothermal aging process. At the same time, it is confirmed that the post-curing process mainly occurs in the hygrothermal aging process. These factors will cause further degradation of the mechanical properties of 3D4d-BC. Han and Nairn [19] conducted aging experiments on laminates under different hygrothermal environments. The results show that with the increase of aging time, temperature, and relative humidity (RH), the toughness of microcracks decreases gradually. Jana and Bhunia [20] conducted interlaminar shear experiments on both slotted and unslotted composite material specimens. The results show that the interlaminar shear strength is related to the number of thermal cycles. Youssef et al. [21] conducted a study on the response to the changes in internal stress caused by the damp-heat aging process. Ma et al. [22] systematically studied the influence of the hygrothermal aging process on the impact properties of CFRP. The results showed that the fiber/matrix interface of CFRP was damaged after aging.

Similarly, the influence of the opening position on its mechanical properties is also one of the hot issues that researchers focus on. Wang et al. [23] studied the tensile and compressive strength of isotropic laminated plates after hole punching. Suemasu et al. [24] explained the compression failure mechanism of quasi-isotropic laminates after opening holes through experiments and numerical simulation. Guan et al. [25] conducted an experimental analysis and numerical simulation on the evolution process of compression damage of the lower composite plate under the effect of hygrothermal aging. Xu et al. [26] observed the fracture morphology of porous composites in hygrothermal environments and room temperature/dry (RTD) environments. It is found that the failure modes in two different environments are not the same. Tojaga et al. [27] introduced the micromechanics of kink band formation in porous composites under compressive load. Zhang et al. [28] proposed a three-dimensional progressive damage analysis model considering fiber kink and shear effects for the damage characteristics of perforated composite laminates. Yildirim et al. [29] used a variety of monitoring methods to study the mechanical behavior and damage evolution of CF/PEKK laminates under tensile loads.

Although many scholars have conducted relevant studies on the mechanism, damage forms, and aging effects of hygrothermal aging, there is still a lack of experimental research on opening holes after wet and heat aging. Based on this, the experimental idea of “hygrothermal aging – opening hole- compression” is set up in this study. Hygrothermal aging type sets different conditions and aging times. It is 70°C–85%Relative Humidity (RH) and 70°C–Soak and the aging time is 500, 1,000 and 2,000 h. On this basis, compression experiments were carried out to analyze the effect of opening hole behavior on mechanical properties after hygrothermal aging. Similarly, the finite-element analysis (FEA) of the hygrothermal aging process and the compression experimental process is carried out to further understand the damage behavior and failure mechanism. This study will provide the experimental basis and numerical simulation experience for the effect of opening hole behavior on the mechanical properties of composite laminates after hygrothermal aging.

2 Experimental procedure

2.1 Materials

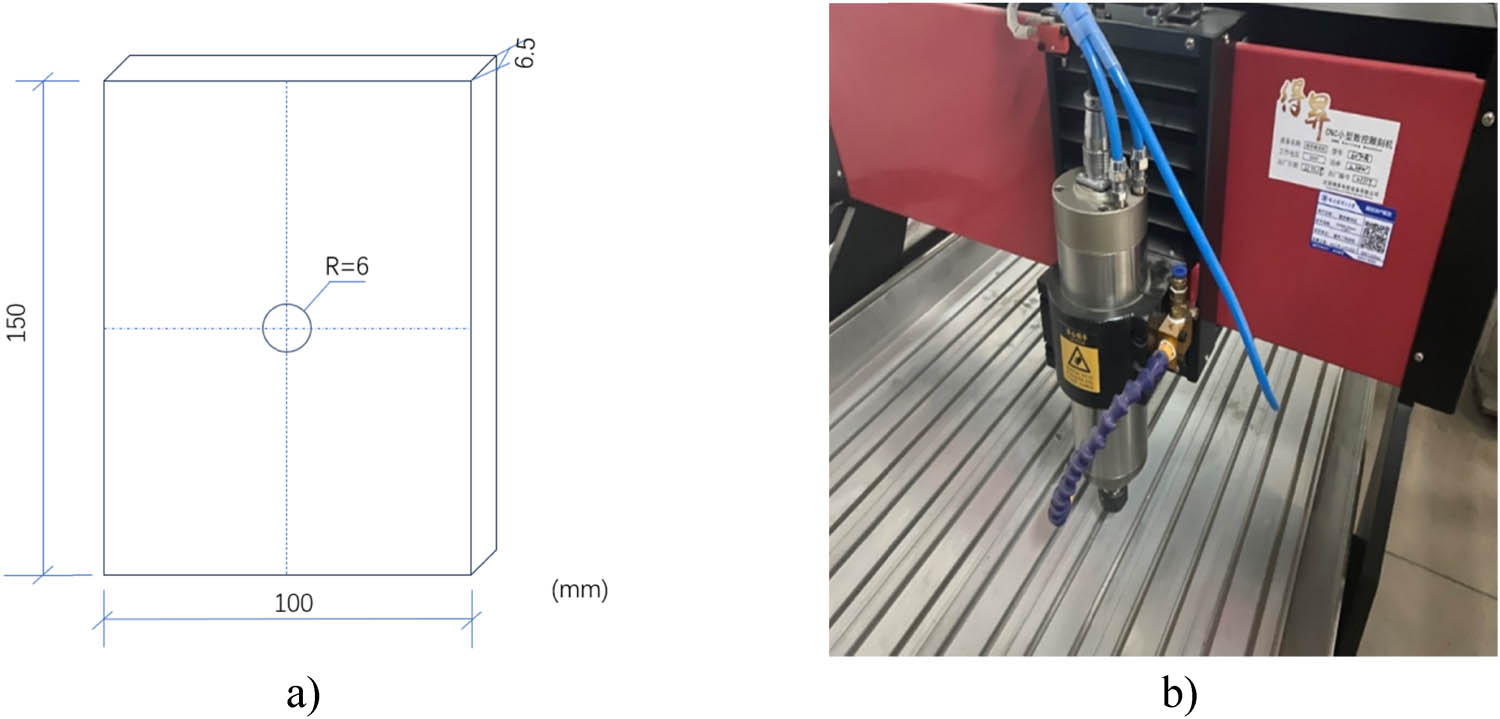

Epoxy resin matrix composite laminate (T700/U3160) was used in this study. Specifically, layering sequence is [0°/45°/90°/−45°]s, single layer thickness is 0.75 mm, plate size is 100 mm × 150 mm × 6.5 mm, and error is ±0.5 mm. The specific parameters of specimens are shown in Table 1.

T700/U3160 composite laminate-related parameters

| Parameter type | Carbon fiber | Epoxy resin |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (10−6 K) | 3.1 | 56.9 |

| Coefficient of wet expansion (10−3/H2O) | 0 | 3.24 |

| Wet diffusivity (10−4 mm/h) | 0 | 18.828 |

| Maximum moisture absorption (%) | 0 | 88% |

| Density (kg/m3) | 1,760 | 1,190 |

2.2 Experimental equipment and process

2.2.1 Hygrothermal aging

According to ASTM hygroscopic standard D5229/D5229M-92, the test part was weighed with a balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg to record the mass of the test part during the hygroscopic process. Before moisture absorption, the test part was washed, the surface dirt was wiped off, and the test part was dried in a vacuum drying box at 85°C for 72 h to the engineering dry state, and the initial weight M0 after drying was measured, accurate to 0.1 mg. During the initial hygroscopic stage, wet test pieces were removed from the furnace every 24 h, and the mass of each test piece was recorded after wiping the surface moisture of the test pieces, with an accuracy of 0.1 mg. The hygrothermal aging process under the condition of 70°C–85%RH is carried out in a constant temperature and humidity test chamber (Figure 1a). The hygrothermal aging process is 70°C–Soak in a thermostatic water bath (Figure 1b). The equipment parameters are shown in Table 2.

Wet heat test equipment: (a) constant temperature and humidity test chamber and (b) thermostatic water bath.

Hygrothermal aging equipment parameters

| Device name | Type | Main parameter |

|---|---|---|

| Constant temperature and humidity test chamber | JHY-H-150L | Temperature interval: −60°C to 150°C |

| Humidity interval: 20%RH to 98%RH | ||

| Thermostatic water bath | HWY-501 | Volume: 20 L |

| Temperature: Room temperature to 80°C |

2.2.2 Open hole experiment

After the hygrothermal aging experiment, all specimens were subjected to an open-hole experiment to study the effect of open-hole behavior on material properties after hygrothermal aging behavior. A small CNC engraving machine (Jiangyin DEGAO Electronic Control Equipment Co., LTD., Wuxi, Jiangsu, China) was used in this experiment. The spindle speed was 8,000 rpm, the feed rate was 0.05 mm, and the cutting edge was a 6 mm two-edge tungsten steel flat-bottom milling cutter made by Taiwan Chunbao (WF25). Milling cutter-specific parameters are shown in Table 3. The opening process is shown in Figure 2.

Specific parameters of milling cutter

| Name | Type | Number of blades | Cutting hardness | Spiral angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-point tungsten steel flat-end milling cutter | Taiwan Chunbao (WF25) | 2 | For steel: ≤58° | Θ1: 40°–42° |

| For aluminum: ≤60° | Θ2: 42°–45° |

Process of the opening experiment: (a) specimen opening diagram and (b) the opening hole experiment process.

2.2.3 Compression experiment

The treated sample was compressed at room temperature. The compression test follows ASTM D7137/D71377-07 standard, and the experimental equipment is a 200 kN hydraulic universal testing machine (UTM). Experimental process: compression load was applied to the sample at a displacement speed of 0.5 mm/min on the upper test-piece’s head of the hydraulic UTM until the sample was damaged and failed. In the compression test, a special fixture (Figure 3b) was used to fix the specimen to ensure that the force direction of the specimen was vertical. At the same time, a 2 mm gap is reserved to provide space for transverse expansion of the specimen that may occur in the case of compression failure. At the beginning, a small prestress is applied to the specimen to ensure complete contact between the specimen and the fixture. Ultrasonic C-scan (C-scan) was used to detect the internal damage area of the specimen (Figure 3d). The C-scan device model is Sonoscan D9500 with a frequency of 5 to 40 M, a sound wave width of 0.25 ns to 1 μs, and a Z-axis resolution of 9 nm. The compression experiment process is shown in Figure 3.

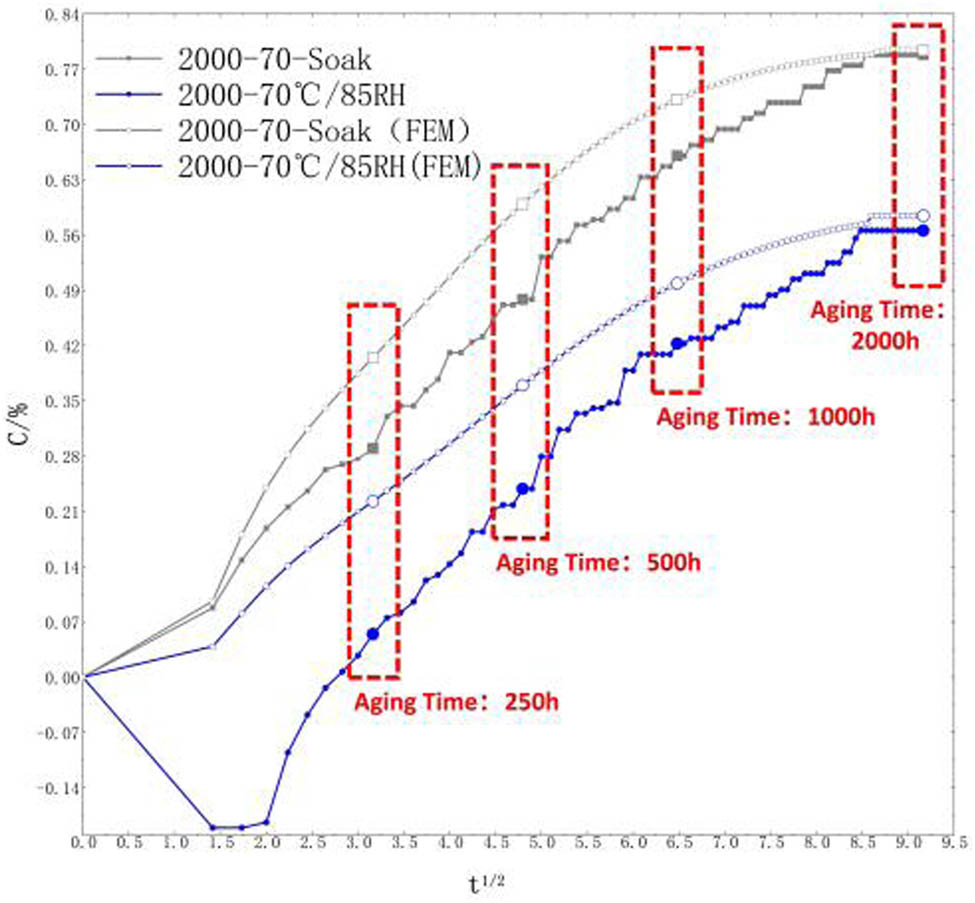

Hygroscopic curves under two kinds of hygrothermal aging conditions. Note: FEM represents numerical simulation results.

3 Hygrothermal aging process and analysis

3.1 Experimental analysis method

The composite laminates aged by moisture and heat were weighed after drying at the same time every day. The weight of the specimen weighed on day t is denoted as M t , and the mass of the specimen during drying is denoted as M 0. The composite material absorbs water in a hygrothermal environment, and the degree of water absorption (denoted as c) is expressed by the water absorption concentration (Formula (1))

According to Fick’s second law (Formula (2)):

where G means moisture absorption rate;

where

Formula (2) can also be reduced to

where K is a constant related to the coefficient of water absorption.

3.2 Numerical simulation analysis method

Based on the material characteristics and test process of composite laminates, a strain-based three-dimensional Hashin criterion is adopted as the damage criterion.

Fiber stretching pattern (

Fiber compression mode (

Matrix tensile mode (

Matrix compression mode (

3.3 Analysis of hygrothermal aging results

The relationship between the hygroscopic concentration c and t1/2 calculated according to the above analysis is shown in Figure 3. In general, when the absolute value of the mass difference of two consecutive weighing attempts is less than or equal to 0.01%, the sample is considered to have reached the stage of hygroscopic equilibrium. It can be seen from Figure 3 that in the initial stage of hygroscopicity, water rapidly diffuses in the composite material. This is because moisture first enters void spaces or defects such as bubbles and cracks inside the material, resulting in a rapid increase in mass. With the increase of hygrothermal aging time, the mass change rate increases slowly and then tends to be stable. Finally, the mass change rate enters the relative saturation stage.

Specific analysis, the specimen numbered 2,000 h–70°C–Soak showed a slight decrease in moisture absorption concentration in the first 2 days. The reason for this phenomenon may be that it has not been previously dried to the engineering dry state. However, 2,000 h–70°C–Soak after reaching the engineering dry state, the water absorption concentration c changes with t 1/2 with other samples still conforms to Fick’s second law. With the increase of moisture absorption time, the water absorption concentration of the test piece began to flatten out. During the whole process, the dilute humidity concentration C is “70°C–70°C/85%RH”. This shows that the higher the humidity, the more moisture absorption of the laminate. In engineering, that is, the higher the humidity in the service environment and the longer the service time, the higher the moisture absorption, and the more obvious the performance decline of the matrix caused by the moisture absorption process. This is mainly due to the mismatch between the moisture and heat expansion of the matrix, which leads to the degradation of the interface bonding properties, and eventually the matrix properties of the composite materials. Similarly, the numerical analysis results of the hygroscopic model established according to Fick’s law fit well with the actual experiment, especially the hygroscopic concentration in the hygroscopic equilibrium stage (Tables 4 and 5). This further indicates that the hygroscopic process in the real environment conforms to Fick’s law.

Comparison of experimental data and simulation results in 70°C–Soak

| Aging time (h) | 70°C–Soak | 70°C–Soak–FEM | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.47837 | 0.61016 | −22 |

| 1,000 | 0.66029 | 0.73163 | −10 |

| 2,000 | 0.7883 | 0.79393 | −1 |

Comparison of experimental data and simulation results in 70°C/85%RH

| Aging time (h) | 70°C/85%RH–Soak | 70°C/85%RH–Soak –FEM | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.2385 | 0.37902 | −37 |

| 1,000 | 0.42249 | 0.4987 | −15 |

| 2,000 | 0.56559 | 0.58432 | −3 |

4 Compression experiment

4.1 Analysis of the compression experiment

The “Distance–Load” curve of all specimens is shown in Figure 4, and the peak load statistics of all specimens are shown in Table 6. Among them, RT represents the test pieces at room temperature (without hygrothermal aging) as the experimental group. Red, green, and blue are used, respectively, to indicate that the aging specimen is less than 500, 1,000, and 2,000 h. As can be seen from the figure, the maximum peak load of the RT group is 164.54KN. After 2,000 h aging treatment, the maximum peak load reduction of the specimen is about 15%. For the same-aged specimens, the peak load difference between 85%RH and Soak is about 1%. Therefore, the increase of humidity will slightly reduce the compressive strength of the material. Aging time is the main factor affecting compressive strength. It should be noted in particular that during the compression experiment, we did not apply prestress to the specimen, resulting in false contact between the top of the specimen and the bottom of the pressure plate. This operation causes the “Load–Displacement” curve to rise slowly in the early stages. The compression modulus calculated from the experimental curve will produce an error of about 20%. It should be noted that the operation error does not affect the compressive failure load of the structure. This paper focuses on the compression failure form and failure behavior after the wet and heat behavior and will further demonstrate its mechanical behavior in the numerical simulation.

The “Distance–Load” curve of all specimens.

Peak load statistics under different wet heat aging conditions

| Hygrothermal aging conditions | Load (kN) | Ratio to control (%) |

|---|---|---|

| RT | 164.54 | — |

| 500 h–70°C/85%RH | 162.35 | 1.33 |

| 500 h–70°C–Soak | 162.27 | 1.38 |

| 1,000 h–70°C/85%RH | 157.48 | 4.29 |

| 1,000 h–70°C–Soak | 154.77 | 5.94 |

| 2,000 h–70°C/85%RH | 139.75 | 15.06 |

| 2,000 h–70°C–Soak | 139.69 | 15.10 |

Similarly, the numerical simulation results under two different aging conditions (aging time 2,000 h) were compared with the experimental results, as shown in Figure 5. The results show that the trend of “Distance–Load” curve obtained by numerical simulation is in good agreement with the experimental results; the differences are 7.1% and 4.9%, respectively. The simulation results validate the conclusions obtained from the test and enhance the reliability of the test conclusions.

The numerical simulation results were compared with the experimental results under two different aging conditions (aging time 2,000 h).

According to different aging conditions and aging times, all specimens were divided into two groups to explore the influence of different humidity and temperature on compressive strength. Figure 6 shows the “Distance–Load” curve under different humidity conditions at the same time. According to Figure 6a, with the increase of aging time, the peak load of the sample at 85% humidity becomes smaller and smaller, and the load–displacement curve is relatively gentle, showing a certain lag. Figure 6b follows the same rule. It is indicated that the longer the material is in service under hot and humid conditions, the lower the mechanical properties and failure load of the material.

“Load–Distance” curves under different aging conditions: (a) 70°C/85%RH and (b) 70°C-Soak.

Figure 7 shows the “Distance–Load” curve under the same humidity and different aging times. In the graph, you can clearly see that the peak load in the “85%RH” condition is slightly larger than the “Soak” condition. With the increase of displacement, the first failure is 85%RH, and Soak has a certain lag. This indicates that at the same temperature, the more the water molecules/the greater the humidity, the more intense the Brownian motion, and the more water enters the material through the inherent defects, further leading to the softening of the matrix and the interface debonding.

“Load–Distance” curves under different aging times: (a) 500 h, (b) 1,000 h, and (c) 2,000 h.

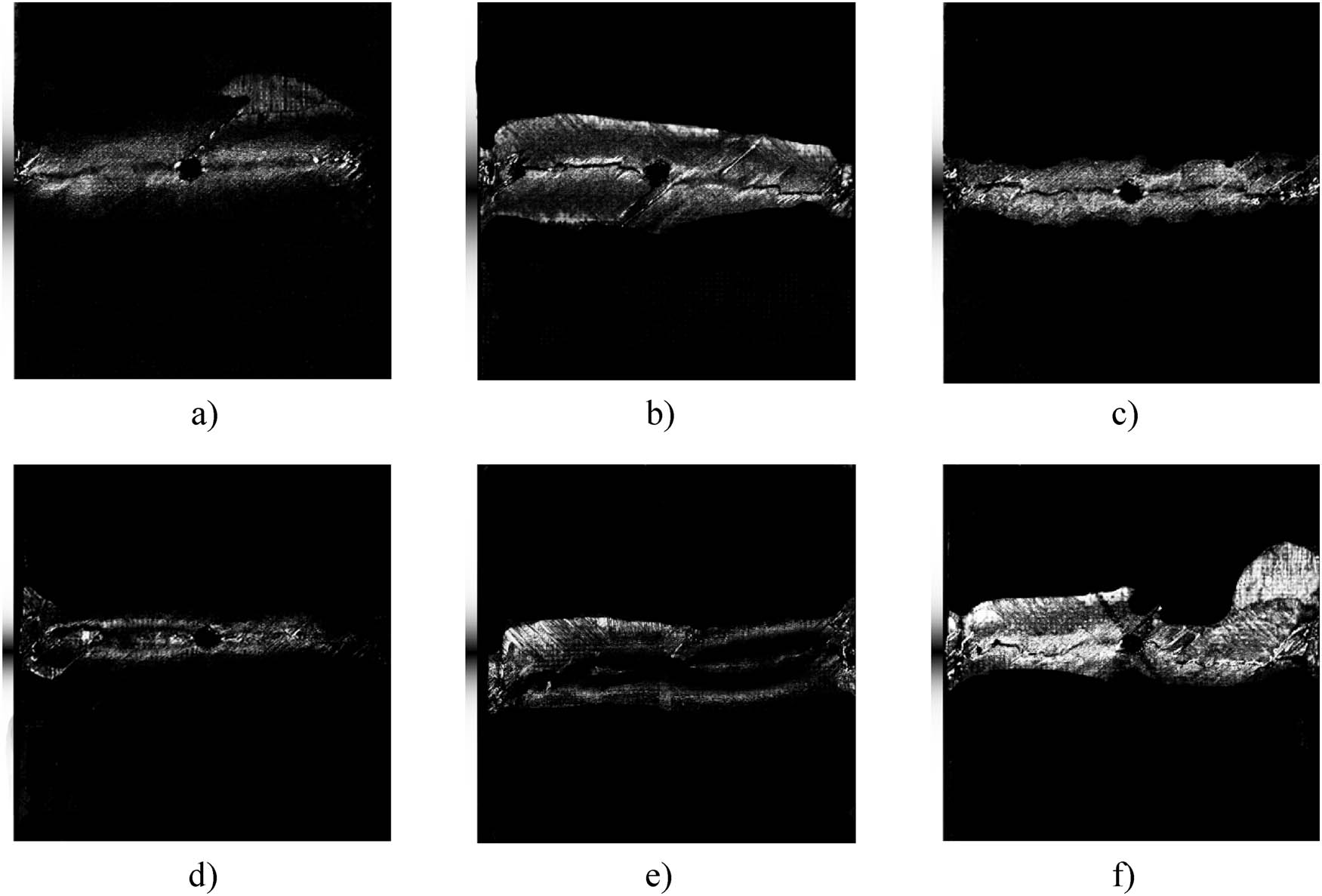

C-scan was performed on all specimens after the compression test, and the results are shown in Figure 8. The statistics of the damaged area are shown in Table 7. As shown in Figure 8, the compression failure extends laterally along the opening until the specimen fails. With the increase of aging time, the damage area is expanding. This indicates that the hygrothermal aging process will cause the specimen to destick and delaminate, which further leads to the decline of mechanical properties. The results shown in Table 7 show that the internal damage area of the specimen treated with 2,000 h is nearly 10% higher than that treated with 500 h. Similarly, the increase in humidity will also increase the area of damage. Therefore, higher humidity and longer aging time are the main reasons for the deterioration of the mechanical properties of specimens.

C-scan images of all specimens: (a) 500 h–70°C–Soak, (b) 1,000 h–70°C–Soak, (c) 2,000 h–70°C–Soak, (d) 500 h–70°C/85%, (e) 1,000 h–70°C/85%, and (f) 2,000 h–70°C/85%.

Internal damage area statistics

| Hygrothermal aging conditions | The proportion of damaged area to scanned area (%) |

|---|---|

| 500 h–70°C/85%RH | 2.64 |

| 500 h–70°C–Soak | 5.90 |

| 1,000 h–70°C/85%RH | 6.26 |

| 1,000 h–70°C–Soak | 7.39 |

| 2,000 h–70°C/85%RH | 15.03 |

| 2,000 h–70°C–Soak | 16.83 |

Finite-element analysis was carried out on specimens subjected to compression tests after 2,000 h of hygrothermal aging treatment. Figure 9 shows the damage evolution of the test specimen under simulated conditions using the second layer (45°) and seventh layer (90°) as examples, which has a high fit with the results of S-can. It can be clearly seen that the loss evolution extends along the fiber laying direction until failure. The simulation is conducted under completely ideal conditions of constraints, loads, and interactions. However, in practical operation, it is inevitable to produce human errors or defects in the test piece itself. Therefore, observation can be made through the degree of fitting of stress–strain curves, loss evolution, fault mechanisms, and other aspects.

Damage evolution in the second layer (45°) and seventh layer (90°) under simulated conditions.

Numerical simulation results at different stages are shown in Figure 10. As can be seen from Figure 10, with the progress of the compression test, the damage went through three stages in total. In the initial stage, damage occurs along the opening position, and stress concentration occurs. Due to longitudinal compression, the transverse moment of inertia is smaller, resulting in greater force. In the damage extension stage, the lateral force is more concentrated (red area). When the ultimate compressive strength of the specimen is reached, the transverse fracture occurs through the opening position, and brittle damage occurs, and the specimen fails at this point. The damage modes and failure forms under the two different conditions are the same. Compared with the experimental results, the numerical simulation results accord with the experimental law and the degree of fitting is high. Specifically, during the whole compression process, the stress performance is 70°C/85%RH > 70°C–Soak. The results are consistent with the experimental results, which further show that higher humidity is the main reason for the deterioration of mechanical properties of materials under the same aging treatment time.

Numerical analysis of “stress–strain” Mises images.

5 Conclusion

In this article, the effects of different hygrothermal aging conditions on the compression properties of composite laminates were studied. C-scan was used to investigate the internal damage area of the specimen after compression. At the same time, using the finite-element analysis method, the hygrothermal aging process and the compression process are numerically simulated. The numerical simulation results agree well with the experimental data. Through the above research, it is found that:

The intrusion of oxygen and water molecules will reduce the compressive strength of the specimen. This is because the strength of the fiber/matrix interface inside the material decreases after the effect of hygrothermal aging.

Aging time is the main factor affecting the mechanical properties of materials;

The open hole compression test shows that the failure will be broken along the open hole until the failure.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 11972140 (Shi Yan), No. 12002003 (Junjun Zhai)], and the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province [No. A2023409007 (Junjun Zhai)] is acknowledged for supporting this research.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, methodology: Shi Yan, Hanhua Li, Junjun Zhai; writing – original draft preparation: Lipeng Liu, Yuxuan Zhang; raw date support: Lipeng Liu, Yue Guan; writing – review and editing: Lipeng liu, Yuanxuan Zhang, Yue Guan; simulation and formal analysis: Lipeng Liu, Yue Guan; validation: Xin Wang; supervision: Shi Yan; funding provided: Shi Yan, Junjun Zhai. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Wang X, Li H, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Yan S, Zhai J. Compressive failure characteristics of 3D four-directional braided composites with prefabricated holes. Materials. 2024;17:3821. 10.3390/ma17153821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Ge J, Luo M, Zhang D, Catalanotti G, Falzon Brian G, McClelland J, et al. Temperature field evolution and thermal-mechanical interaction induced damage in drilling of thermoplastic CF/PEKK – A comparative study with thermoset CF/epoxy. J Manuf Process. 2023;88:167–83. 10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.01.042.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang Y, Yan S, Jiang L, Fan T, Zhai J, Li H. Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2024;63:20240003. 10.1515/rams-2024-0003.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ogbonna VE, Popoola API, Popoola OM, Adeosun SO. A review on corrosion, mechanical, and electrical properties of glass fiber-reinforced epoxy composites for high-voltage insulator core rod applications: challenges and recommendations. Polym Bull. 2022;79:6857–84. 10.1007/s00289-021-03846-z.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhang Y, Yan S, Du C, Jiang L, Zhai J. Experimental analysis of low-velocity impact and CAI properties of 3D four-directional braided composites after hygrothermal aging. Materials. 2024;17:3151. 10.3390/ma17133151.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Frej H, Léger R, Perrin D, Ienny P. A novel thermoplastic composite for marine applications: Comparison of the effects of aging on mechanical properties and diffusion mechanisms. Appl Compos Mater. 2021;28:899–922. 10.1007/s10443-021-09903-0.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Haris N, Hassan M, Ilyas RA, Suhot M, Sapuan SM, Dolah R, et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced hybrid polymer composites: A review. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;19:167–82. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.04.155.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yildirim C, Ulus H, Beylergil B, Al-Nadhari A, Topal S, Yildiz M. Tailoring adherend surfaces for enhanced bonding in CF/PEKK composites: Comparative analysis of atmospheric plasma activation and conventional treatments. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2024;180:108101. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2024.108101.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Topal S, Al-Nadhari A, Yildirim C, Beylergil B, Kan C, Unal S, et al. Multiscale nano-integration in the scarf-bonded patches for enhancing the performance of the repaired secondary load-bearing aircraft composite structures. Carbon. 2023;204:112–25. 10.1016/j.carbon.2022.12.056.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ge J, Catalanotti G, Falzon Brian G, McClelland J, Higgins C, Jin Y, et al. Towards understanding the hole making performance and chip formation mechanism of thermoplastic carbon fibre/polyetherketoneketone composite. Compos Part B: Eng. 2022;234:109752. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.109752.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kakinuma Y, Ishida T, Koike R, Klemme H, Denkena B, Aoyama T. Ultrafast feed drilling of carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastics. Procedia CIRP. 2015;35:91–5. 10.1016/j.procir.2015.08.074.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Batista M, Basso I, Toti F, Rodrigues A, Tarpani J. Cryogenic drilling of carbon fibre reinforced thermoplastic and thermoset polymers. Compos Struct. 2020;251:112625. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112625.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Xu J, Huang X, Davim JP, Ji M, Chen M. On the machining behavior of carbon fiber reinforced polyimide and PEEK thermoplastic composites. Polym Compos. 2020;41:3649–63. 10.1002/pc.25663.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gaugel S, Sripathy P, Haeger A, Meinhard D, Bernthaler T, Lissek F, et al. A comparative study on tool wear and laminate damage in drilling of carbon-fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP). Compos Struct. 2016;155:173–83. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.08.004.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wang P, Ke L, Wu H, Leung Christopher KY. Hygrothermal aging effect on the water diffusion in glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) composite: Experimental study and numerical simulation. Compos Sci Technol. 2022;230:109762. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109762.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Fiore V, Calabrese L, Miranda R, Badagliacco D, Sanfilippo C, Palamara D, et al. An experimental investigation on performances recovery of glass fiber reinforced composites exposed to a salt-fog/dry cycle. Compos Part B: Eng. 2023;257:110693. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110693.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Sun P, Zhao Y, Luo Y, Sun L. Effect of temperature and cyclic hygrothermal aging on the interlaminar shear strength of carbon fiber/bismaleimide (BMI) composite. Mater Des. 2011;32:4341–7. 10.1016/j.matdes.2011.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Zhang Y, Yan S, Wang X, Guan Y, Du C, Fan T, et al. An experimental investigation of the mechanism of hygrothermal aging and low-velocity impact performance of resin matrix composites. Polymers. 2024;16:1477. 10.3390/polym16111477.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Han M-H, Nairn J. Hygrothermal aging of polyimide matrix composite laminates. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2003;34:979–86. 10.1016/s1359-835x(03)00154-4.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Jana RN, Bhunia H. Hygrothermal degradation of the composite laminates from woven carbon/SC‐15 epoxy resin and woven glass/SC‐15 epoxy resin. Polym Compos. 2008;29:664–9. 10.1002/pc.20417.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Youssef Z, Jacquemin F, Gloaguen D, Guillén R. A multi-scale analysis of composite structures: Application to the design of accelerated hygrothermal cycles. Compos Struct. 2008;82:302–9. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2007.01.008.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ma S, He Y, Hui L, Xu L. Effects of hygrothermal and thermal aging on the low-velocity impact properties of carbon fiber composites. Adv Compos Mater. 2020;29:55–72. 10.1080/09243046.2019.1630054.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Wang J, Callus PJ, Bannister MK. Experimental and numerical investigation of the tension and compression strength of un-notched and notched quasi-isotropic laminates. Compos Struct. 2004;64:297–306. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2003.08.012.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Suemasu H, Takahashi H, Ishikawa T. On failure mechanisms of composite laminates with an open hole subjected to compressive load. Compos Sci Technol. 2006;66:634–41. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.07.042.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Guan Y, Yan S, Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li H, et al. Analysis of residual post-impact compressive strength of composite laminates under hygrothermal conditions. Appl Compos Mater. 2024;1–21. 10.1007/s10443-024-10258-5.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Xu L, He Y, Ma S, Hui L, Jia Y, Tu Y. Effects of aging process and testing temperature on the open-hole compressive properties of a carbon fiber composite. High Perform Polym. 2020;32:693–701. 10.1177/0954008319897291.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Tojaga V, Skovsgaard Simon PH, Jensen H. Micromechanics of kink band formation in open-hole fibre composites under compressive loading. Compos Part B: Eng. 2018;149:66–73. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.05.014.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zhang D, Zheng X, Wu T. Damage characteristics of open-hole laminated composites subjected to longitudinal loads. Compos Struct. 2019;230:111474. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111474.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Yildirim C, Tabrizi I, Al-Nadhari A, Topal S, Beylergil B, Yildiz M. Characterizing damage evolution of CF/PEKK composites under tensile loading through multi-instrument structural health monitoring techniques. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2023;175:107817. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2023.107817.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation on cutting of CFRP composite by nanosecond short-pulsed laser with rotary drilling method

- Antibody-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles as a selective doxorubicin vehicle to improve toxicity against HER2+ breast cancer cells

- Study on the effects of initial stress and imperfect interface on static and dynamic problems in thermoelastic laminated plates

- Analysis of the laser-assisted forming process of CF/PEEK composite corner structure: Effect of laser power and forming rate on the spring-back angle

- Phase transformation and property improvement of Al–0.6Mg–0.5Si alloys by addition of rare-earth Y

- A new-type intelligent monitoring anchor system for CFRP strand wires based on CFRP self-sensing

- Optical properties and artistic color characterization of nanocomposite polyurethane materials

- Effect of 200 days of cyclic weathering and salt spray on the performance of PU coating applied on a composite substrate

- Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of the effect of opening hole behavior after hygrothermal aging on the compression properties of laminates

- Engineering properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete with polyester-coated pumice aggregates

- Optimization of rGO content in MAI:PbCl2 composites for enhanced conductivity

- Collagen fibers as biomass templates constructed multifunctional polyvinyl alcohol composite films for biocompatible wearable e-skins

- Early age temperature effect of cemented sand and gravel based on random aggregate model

- Properties and mechanism of ceramizable silicone rubber with enhanced flexural strength after high-temperature

- Buckling stability analysis of AFGM heavy columns with nonprismatic solid regular polygon cross-section and constant volume

- Reusable fibre composite crash boxes for sustainable and resource-efficient mobility

- Investigation into the nonlinear structural behavior of tapered axially functionally graded material beams utilizing absolute nodal coordinate formulations

- Mechanical experimental characteristics and constitutive model of cemented sand and gravel (CSG) material under cyclic loading with varying amplitudes

- Synthesis and properties of octahedral silsesquioxane with vinyl acetate side group

- The effect of radiation-induced vulcanization on the thermal and structural properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) rubber

- Review Articles

- State-of-the-art review on the influence of crumb rubber on the strength, durability, and morphological properties of concrete

- Recent advances in carbon and ceramic composites reinforced with nanomaterials: Manufacturing methods, and characteristics improvements

- Special Issue: Advanced modeling and design for composite materials and structures

- Validation of chromatographic method for impurity profiling of Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)