Abstract

A climate-resilient, root-based sweetpotato planting material (SPM) conservation method called “Triple S” or “Storage in Sand and Sprouting” has created timely access to sweetpotato planting material in areas with a prolonged dry season in Uganda and Tanzania. The aim of this study was to validate and optimize the Triple S method for conservation of sweetpotato planting material in dry areas of southern Ethiopia. The Triple S method was validated in four districts of southern Ethiopia on varieties Kulfo and Awassa 83 and compared with two common local planting material conservation methods: leaving “volunteer roots” in the soil which then sprout at the onset of rains; and planting vines under shade or mulch. Across study locations and for both varieties, Triple S resulted in a higher survival rate (81–95%) in storage during the dry season compared to the local conservation methods (7–57%). Plants of both varieties grown from roots conserved with the Triple S method showed significantly higher vine growth and lower weevil and virus infection symptoms compared to plants grown from the two local conservation methods. An additional experiment found that planting at the start of the main rainy season in June and harvesting just before the start of the dry season in October gives the highest number of medium-sized and weevil-free roots suitable for Triple S. The current study demonstrated that the Triple S method is a promising technology for small-scale sweetpotato farmers in dry areas for timely access to high-quality planting material

1 Introduction

The Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) is the major sweetpotato producing region of Ethiopia, it covers 65% of the total area under sweetpotato production of the country [1]. Sweetpotato is the main food security crop in SNNPR, but the lack of planting material is constraining the production and role of sweetpotato for food security [2,3,4]. The effort to disseminate orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) varieties to fight vitamin A deficiency is being affected by the inability to get access to the planting material [5]. Vines from farm-grown sweetpotato plants are the main source of sweetpotato planting material in SNNPRs [6]. Traditionally, farmers in southern Ethiopia conserve sweetpotato planting material during the dry season by either: (1) planting under the shade of enset plant at the backyard, (2) conserving vines in a wet part of the farm under mulch, (3) a combination of (1) and (2), or (4) leaving some roots in the soil at harvest which then sprout with the onset of rains (“volunteer plants”) [6,7,8,9]. Where farmers cannot rely on volunteer plants because of too harsh conditions during the dry season, they may bury fresh roots in a wet and fertile part of the farm which then sprout at the onset of rains similar to volunteer plants [7,10].

On-farm conservation of sweetpotato planting material is challenging as lack of water and heat stress during the dry period cause planting material to dry out before the start of the rainy season [10,11]. The loss and subsequent shortage of planting material is a major constraint to sweetpotato production in Ethiopia [7,8,9,10]. According to McEwan [7] and Gibson [8], this lack of planting material is the main reason why the crop is grown less with increasing distance from the Equator, further impoverishing some of the poorest people in Africa in countries such as in Ethiopia, Sudan, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi. The on-farm conservation of planting material is further constrained by the pressure from sweetpotato virus diseases (SPVD) and sweetpotato weevil, which intensifies during the dry season [2,12,13] and leads to low-quality planting material. Use of such material as seed can result in a yield reduction up to 70% [14]. To replenish the lost planting material or renew the deteriorated stock, quality declared planting material is not available in the local seed market; if available, it is expensive and most resource-poor sweetpotato producers cannot afford to buy it [15]. In some areas of SNNPR, farmers were forced to stop growing sweetpotato because of the lack of planting material following loss of farm growing sweetpotato in drought years (personal communication). There have been extensive planting material distribution programs to restore sweetpotato production, but in the driest areas, the distributed material gets lost within a few seasons. More recently, government and development organizations have distributed planting material of beta-carotene rich OFSP varieties to improve the population’s access to micronutrients, in particular Vitamin A [16]. However, the inability of the farmers to conserve planting material during the dry season constrains the sustained production of these varieties [17,18,19,20]. As a result, resource-poor farmers have not been able to benefit from the food, nutrition, and income benefits of OFSP varieties.

The development of the Ethiopian sweetpotato sector depends on cost-effective planting material conservation and production methods [12]. Aware of the need for innovative approaches for tackling planting material shortage in an affordable way, the International Potato Center and the Natural Resources Institute in the United Kingdom jointly developed a climate-resilient and affordable root-based sweetpotato seed conservation technique called “Triple S,” or “Storage in Sand and Sprouting” [21]. Triple S was initially developed for areas in Uganda with a dry period of 3 months and then later validated in dry parts of Tanzania where the duration of the dry period is 5 months [21]. For successful use of the Triple S method, stored roots should sprout slowly and survive the dry period without spoilage and drying [21]. The technology created timely access of clean planting material where sweetpotato farmers in dry part of Uganda and Tanzania could plant sweetpotato at the start of rain and harvest early to fill the hunger period [11]. Although sweetpotato propagation by root piece is known for its high genotype by environment interaction and yield instability [22], planting material derived from Triple S method is true-to-type and same as other vine based propagation except the vine is grown from sprouted roots [11,21]. However, humidity, temperature, genotype, and the length of the dry season may affect the success of Triple S in a given environment by affecting sprouting, weight loss (dryness), and spoilage (rotting) [20,22,23,24,25]. Storage condition with higher humidity and high temperature promote sprouting, while lower humidity leads to rapid weight loss and slow sprouting of sweetpotato roots [22,23,26]. The type of agronomic management such as organic fertilizer, harvesting age, and stress affect the post-harvest characteristics of sweetpotato roots at storage where application of organic fertilizer affected sprouting, weight loss, and rotting [24,25]. The effect of genotype is also an important factor that determines the sprouting and slip production potential of sweetpotato roots when used as multiplication material [11,27,28]. Sweetpotato farmers in Ethiopia do not practice ex-situ root conservation method [2,12,28], but these farmers have high technical efficiency to practice new technologies [29] that is required to adopt technologies like Triple S. Therefore, validation of Triple S in SNNPR was conducted to study the suitability of Triple S in SNNPR where there is difference in agro-ecology, variety, length of dry season, and farming system than the place where Triple S was developed.

2 Materials and methods

The aim of this study was to validate and optimize the Triple S method for conservation of sweetpotato planting material in dry areas of southern Ethiopia. Using the Triple S method, a farmer selects and stores healthy sweetpotato roots in a container lined with a sheet of newspaper and layers of dry sand for the duration of the dry season. Roots stored in the sand will sprout slowly without rotting or drying. 6–8 weeks before the rains start, the roots which have sprouted are planted out for further multiplication in seed root beds and watered twice a week. When the rains start, the vines in the root bed can be harvested and used as planting material. A single stored root can give up to 40 vine cuttings. The Triple S method was tested for varieties Kulfo and Awassa 83 and compared with two common local planting material conservation methods: leaving “volunteer roots” in the soil which then sprout at the onset of rains and planting vines under shade or mulch.

2.1 Selection of study areas, research groups, and research plots

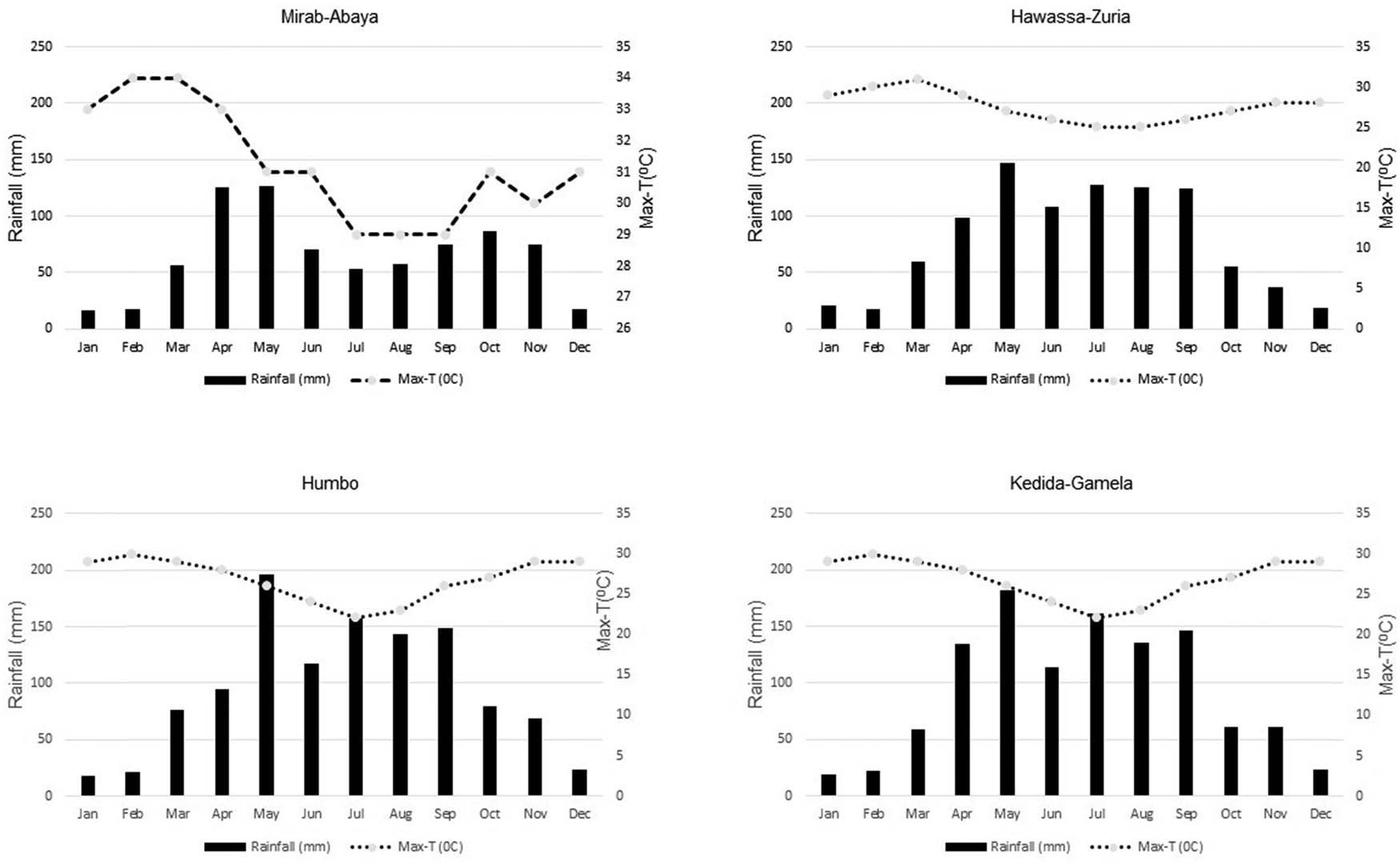

The research took place in four sweetpotato growing districts in the SNNPR: Mirab-Abaya, Hawassa-Zuria, Humbo, and Kedida-Gamela in 2015 and 2016. These districts differ with regard to precipitation, temperature, and length of the dry season (Figure 1). Mirab-Abaya district receives the lowest annual rainfall (773 mm), followed by Hawassa-Zuria (940 mm), Humbo (1,140 mm), and Kedida-Gamela (1,120 mm). December, January, and February are dry months (called “Bega”) for all districts (Figure 1). From March–May, rainfall starts to increase with the rate of increase depending on the district. This period is called “Belg.” The main rainy season in which farmers plant their crops is between June and August and is called “Kiremit.” Rainfall declines starting from September, depending on the district, and completely stops in November, and this period is called “Meher.” Hawassa-Zuria has the longest period of 5 consecutive dry months receiving less than 2 mm rainfall a day starting from October to February followed by Kedida-Gamela and Mirab-Abaya which have 4 months and Humbo has only 3 consecutive dry months between December and February. Mirab-Abaya has the highest maximum temperatures during the dry period (“Bega”) season making it the harshest of all to field growing plants during the dry period. The main sweetpotato planting time in the two driest districts, Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria, is between May and June. In Humbo and Kedida-Gamela, sweetpotato is planted at the end of the rainy season starting from September for root production in the main farm based on residual moisture and for planting material conservation under enset (Ensete ventricosum) shade during the dry season.

Monthly average maximum temperature and rainfall of the four study areas based on 10 years data (2006–2015).

In each of the selected districts, one main sweetpotato producing peasant association (kebele) was selected in consultation with the district Bureau of Agriculture and Natural Resource Development office. In each peasant association, 30 sweetpotato farmers were identified and grouped into 3 Farmer Research Groups (FRG) of 10 farmers each. In total, 12 FRGs, 3 in each district, were formed. Consultation meetings (one per kebele) were carried out to select one host farmer per FRG and to identify the main two local sweetpotato planting material conservation methods. In each FRG, the selected host farmer provided an experimental field and managed the experiment described below. In addition, the selected farmer hosted meetings with FRG members to demonstrate the different steps of the Triple S method and to collect data. Throughout the experiment, there were five meetings conducted with each FRG to introduce the research idea, demonstrate the Triple S method, collect data, and manage the conservation plots.

2.2 Participatory identification of local conservation methods

At the start of the experiment, the researcher asked the members of each FRG to identify sweetpotato planting material conservation methods used by farmers during the dry season in their area. In Kedida-Gamela and Humbo districts, where the length of the dry season is only 3 months, farmers practice a combination of planting under the shade of enset, with mulching, and using vines from volunteer plants. Enset is also known as “false banana” and has a similar shape and grown in clusters similar to banana trees. In Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria, no shade trees are available and most farmer use vines from volunteer plants, although conserving vines under mulch (without shade) is also practiced. Accordingly, planting in shade (if available) with mulching and the use of vines from sprouted volunteer roots were identified as the two commonly used conservation methods for planting material.

2.3 Experimental design of participatory validation of the Triple S method

Members of the FRG were involved in experimental setup, management, and data collection. Participatory validation of Triple S was conducted by comparing the Triple S method and the selected two local conservation methods in each area (FRG). Accordingly, there were three planting material conservation treatments: the Triple S method (“Triple S”), using vines sprouted from roots that remained buried in the soil during the dry season (“volunteer”), and preserving vines under shade or mulch (“shade/mulch”). The Triple S method was adopted from the work conducted in Uganda by Namanda et al. (2013). In each FRG, the experiment was installed with one replicate, and hence FRGs within the district served as replicates, with three replicates per district. Therefore, the experiment had two factors: district and conservation method. In Mirab-Abaya, Humbo, and Kedida-Gamela, two locally available varieties Awassa 83 and Kulfo were used for the experiment. In Hawassa-Zuria, only one variety, Kulfo, was used as there was no good quality roots for Awassa 83 at the time of the experiment. Awassa 83 is a local, white-fleshed sweetpotato variety, while Kulfo is an OFSP variety that is being promoted in Ethiopia to address vitamin A deficiency. Farmers claim that Kulfo is more sensitive to drought than Awassa 83, which makes difficult to conserve planting material of Kulfo. The experiment was established in December 2014, after the long rainy season. Sweetpotato roots and vines were obtained from a certified commercial vine multiplication company (Jara Agro Industry).

For each Triple S treatment, 40 roots were used. The roots were harvested from visually clean, disease-free sweetpotato plants (based on observation). Medium size, disease-free, weevil-free, and undamaged roots were carefully selected and transported to the study locations. Members of the FRGs collected sand from nearby areas. The sand was sun-dried and placed in a dry place under shade to cool down. Each FRG prepared an 80 cm diameter plastic basin for both varieties. First, the basins were lined with dry newspaper. Then, a 2 cm layer of sand was poured into the basin and the selected roots were carefully placed on the sand without touching other roots. A 2 cm layer of sand was added on the top of the roots and subsequently other layers of roots were placed in a similar way until the basins were full, ending with a 10 cm layer of sand on top. The Triple S basins were then kept in a safe and dry place in the main house of the host farmer.

For the volunteer treatment, 20 roots were buried in a humid and fertile part of the farm of the host farmer at the same time as establishing the Triple S basins. Each root was buried in a 30 cm deep hole as per the local practice. For the shade/mulch treatment, 20 vine cuttings were planted under shade trees located at the backyard of the host farmer’s farm using a spacing of 30 cm × 60 cm between plants and rows, respectively. In Humbo and Kedida-Gamela districts, fertile backyard land with enset plants were used as planting blocks whereas in Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria, where enset is not grown, vines were planted in a fertile and humid part of the farm selected by the farmer and mulched with grass and cow dung.

Based on the starting time of rainfall which was after 179, 149, 110, and 102 dry days in Mirab-Abaya, Hawassa-Zuria, Humbo, and Kedida-Gamela, respectively, Triple S roots that had survived and were sprouting at the end of the storage period were planted out in a seed root bed for vine multiplication. The sprouted roots were buried at a depth of 30 cm using 50 cm × 50 cm spacing between roots and rows. At this time, data on the number of surviving roots survived under the Triple S method and volunteer treatments as well as number of surviving vines in the shade/mulch treatment were collected.

The seed beds were not irrigated as they were established at the start of the rainy season at each district. Forty-five days after planting out the sprouted roots from the Triple S basins (July 2015 for Mirab-Abaya, June 2015 for Hawassa, and May 2015 for Humbo and Kedida-Gamela), vines from the three treatments were harvested. First, the FRG members counted the number of plants in each of the treatment plots (stand count). Vine length was measured from five surviving plants per plot (and from all remaining plants if less than five had survived). The vine length of all branches longer than 30 cm of every plant was measured. Total vine length was calculated by adding the length of the main stem and those of the branches. Damage from weevil infestation and viruses were evaluated by counting the number of plants which were attacked by weevils and/or viruses, and presented as the percentage of plants affected. Survival rate of planting material during the dry season was calculated as:

Vine cutting productivity was defined as the number of 30 cm vine cuttings harvested per root or vine stored using the different conservation methods and calculated as follows:

2.4 Local optimization of planting and harvesting time of roots for the Triple S method

After understanding the potential of Triple S to conserve better quantity of quality sweetpotato planting material than the conventional methods, a follow-up experiment was conducted in an attempt to synchronize the main Triple S steps with the districts’ sweetpotato planting times. The study aimed at identifying the right time for planting and harvesting of sweetpotato to produce high quality roots to be conserved as planting material using the Triple S method. High quality roots for storage are roots that are medium in size, undamaged, and free from weevil infection and from plants without viruses.

The effect of harvest time on the quality of roots for conservation as planting material using the Triple S method was tested for two different planting times, in April 2016 (early planting) and June 2016 (normal planting time). The variety Kulfo was used for the experiment. Vine cuttings of 30 cm were planted using a spacing of 30 cm and 60 cm between plants and rows, respectively, in 6 m × 3 m plots (10 rows of 10 plants per row making 100 plants per plot). From each plot, 3 rows excluding the border plants (24 plants) were harvested during 3 consecutive harvesting times in September, October, and November for the plots planted in April 2016, and October, November, and December for the plots planted in June 2016. Data on root yield, number of small-, medium-, and large-sized roots which weigh approximately 100–200, 200–400, and 400–550 g, respectively (based on farmers’ standard of classification by visual observation) and number of weevil-damaged roots were collected at harvest.

2.5 Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a mixed model with district and planting material conservation method as fixed factors and FRG as random factor (replication). For the validation experiment, the analysis of treatment effects on vine characteristics was conducted for the two varieties separately. The experiment to evaluate the effect of harvest time on root quality was analyzed using a mixed model with harvest time and district as fixed factor and FRG as random factor (replication). The analysis of treatment effects was conducted for each planting time separately. SPSS statistical software version 24 was used for the analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Participatory validation of the Triple S method

3.1.1 Survival of planting material during the dry season

In all locations, percentage of root survived for both varieties (Kulfo and Awassa 83) stored using the Triple S method was significantly higher than percentage of survived plants conserved using the mulch/shade and volunteer methods. Comparison between the two local conservation methods showed for both varieties that there was no significant difference in Hawassa-Zuria and Mirab-Abaya; however, the volunteer method resulted in a higher survival than the shade/mulch method in Humbo and Kedida-Gamela for variety Kulfo. Awassa 83 conserved using the volunteer method performed better in Humbo but poorly in Kedida-Gamela. (Table 1).

Effects of conservation methods and locations on plants/roots survived (%) over the dry period in southern Ethiopia (2015)

| Planting material survival rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirab-Abaya | Hawassa-Zuria | Humbo | Kedida-Gamela | |

| Kulfo | ||||

| Triple S | 95 | 95 | 83 | 81 |

| Shade/mulch | 7 | 13 | 33 | 37 |

| Volunteer | 8 | 12 | 57 | 46 |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | |||

| Location (L) | *** | |||

| C × L | *** | 2.6–3 | ||

| Awassa 83 | ||||

| Triple S | 83 | 87 | 84 | |

| Shade/mulch | 20 | 33 | 42 | |

| Volunteer | 18 | 65 | 34 | |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | |||

| Location (L) | *** | |||

| C × L | *** | 3.4 | ||

a Standard error of the difference; where range is indicated, the smallest value should be used for comparisons within location and the largest value for comparisons between locations; *** – P < 0.001; ns – not significant.

Comparison among the locations showed difference among the conservation methods. In variety Kulfo, the survival of planting material subjected to Triple S treatment was higher in Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria compared to Humbo and Kedida-Gamela. In contrast, Kulfo conserved in mulch and volunteer method showed lower rate of survival at Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria compared to Humbo and Kedida-Gamela. For Awassa 83, survival of planting material in the Triple S treatment was not affected by location; but survival in the volunteer treatment was significantly lower in Mirab-Abaya and higher in Kedida-Gamela followed by Humbo district (Table 1).

3.2 Vine length and cutting productivity

Vine length per plant at 45 days after planting the roots in the seed bed using sprouted roots stored under the Triple S method was significantly higher than vine length of the surviving plants from the shade/mulch and volunteer treatments in all locations and for both varieties. Average vine length per plant for Kulfo and Awassa 83 were 581 and 565 cm in the Triple S, 141 and 300 cm in shade/mulch, and 200 and 246 cm in the volunteer treatments, respectively (data not presented).

Comparison across the three conservation methods showed that the Triple S method resulted in the highest cutting productivity in all locations compared to the two local conservation methods. The highest number of cuttings were obtained from the Triple S roots of both varieties Kulfo and Awassa 83 in Hawassa-Zuria and Humbo districts, respectively (Table 2).

Effect of conservation methods and locations on number of multiplied cuttings in dry areas of southern Ethiopia

| Cutting productivity (number of 30 cm cuttings) | Average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirab-Abaya | Hawassa-Zuria | Humbo | Kedida-Gamela | ||

| Kulfo | |||||

| Triple S | 320 | 405 | 344 | 298 | 342 |

| Shade/mulch | 3 | 12 | 41 | 57 | 28 |

| Volunteer | 5 | 11 | 64 | 62 | 35 |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | ||||

| Conservation (C) | *** | ||||

| Location (L) | ns | ||||

| C × L | *** | 14–16 | |||

| Awassa83 | |||||

| Triple S | 304 | — | 353 | 306 | 321 |

| Shade/mulch | 31 | — | 77 | 90 | 66 |

| Volunteer | 17 | — | 129 | 71 | 72 |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | ||||

| Conservation (C) | *** | ||||

| Location (L) | *** | ||||

| C × L | *** | 12 | |||

a Standard error of the difference; where range is indicated, the smallest value should be used for comparisons within location and the largest value for comparisons between locations; *** – P < 0.001; ns – not significant.

Cutting productivity of Triple S was significantly affected by location where the highest and lowest number of cuttings were obtained at Hawassa-Zuria and Kedida-Gamela, respectively. Likewise, the locations differed significantly in cutting productivity derived from shade/mulch and volunteer treatments. Plants from both shade/mulch and volunteer treatments in Humbo and Kedida-Gamela gave a higher cutting productivity compared to Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria for both varieties. On an average across locations, cutting productivity was higher for the volunteer treatment compared to the shade/mulch treatment for both varieties (Table 2).

3.3 Rate of weevil infestation

Conservation of roots of both varieties in Triple S method and planting out the sprouted roots in seed beds showed zero percentage weevil infestation across all locations. In contrast, conservation using the shade/mulch and volunteer treatments resulted in higher weevil infestation. Kulfo showed higher susceptibility to weevils compared to Awassa 83. In general, conservation under shade/mulch showed a significantly lower rate of weevil damage than the volunteer conservation method across all locations. This was with the exception of Mirab-Abaya where Kulfo conserved in either of the local method showed same weevil damage (89%). There was a significant difference across locations: in Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria, both varieties scored a higher rate of weevil damage compared to Humbo and Kedida-Gamela. For both varieties there is no significant interaction between location and conservation methods for weevil damage (Table 3).

Effect of conservation method and location on percentage of weevil-infested plants in multiplication plots

| Percentage of weevil affected plants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirab-Abaya | Hawassa-Zuria | Humbo | Kedida-Gamela | |

| Kulfo | ||||

| Shade/mulch | 89 | 75 | 29 | 37 |

| Volunteer | 89 | 97 | 55 | 72 |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | 5 | ||

| Location (L) | *** | 8 | ||

| C × L | ns | |||

| Awassa 83 | ||||

| Shade/mulch | 41 | 25 | 27 | |

| Volunteer | 74 | 49 | 52 | |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | 2 | ||

| Location (L) | *** | 3 | ||

| C × L | ns | |||

NB: infestation by weevils was zero in the Triple S treatment for all locations and both varieties and results are not shown. a Standard error of the difference; where range is indicated, the smallest value should be used for comparisons within location and the largest value for comparisons between locations; *** – P < 0.001; ns – not significant.

3.4 Percentage of plants with SPVD symptom

Visual observation and scoring of SPVD symptoms in multiplication plots derived from Triple S roots were significantly lower than shade/mulch and volunteer treatments for both varieties across all locations. For both varieties, conservation using the shade/mulch method showed significantly higher percentage of SPVD infected plants than the volunteer method in all locations except in Mirab-Abaya for variety Awassa 83 (Table 4). The highest prevalence of SPVD symptoms (75%) was observed in plots with the shade/mulch treatment in Hawassa-Zuria, while the lowest SPVD prevalence was observed in Triple S derived plots in Kedida-Gamela for variety Awassa 83 (0%) and Humbo for variety Kulfo (1%). There was a significant difference by location for SPVD symptoms where Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria scored higher than Humbo and Kedida-Gamela (Table 4).

Effect of conservation method and location on percentage of plants with SPVD symptoms

| Percentage of plants with SPVD symptoms % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirab-Abaya | Hawassa-Zuria | Humbo | Kedida-Gamela | |

| Kulfo | ||||

| Triple S | 5 | 7 | 1 | 4 |

| Shade/mulch | 75 | 100 | 37 | 27 |

| Volunteer | 44 | 28 | 27 | 14 |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | 6 | ||

| Location (L) | *** | 7 | ||

| C × L | ns | |||

| Awassa 83 | ||||

| Triple S | 9 | 13 | 0 | |

| Shade/mulch | 74 | 49 | 35 | |

| Volunteer | 70 | 26 | 47 | |

| Probabilities of F-statistics | SED a | |||

| Conservation (C) | *** | 9 | ||

| Location (L) | *** | 7 | ||

| C × L | ns | |||

a Standard error of the difference; where range is indicated, the smallest value should be used for comparisons within location and the largest value for comparisons between locations; *** – P < 0.001; ns – not significant.

3.5 Local optimization of planting and harvesting time of roots for the Triple S method

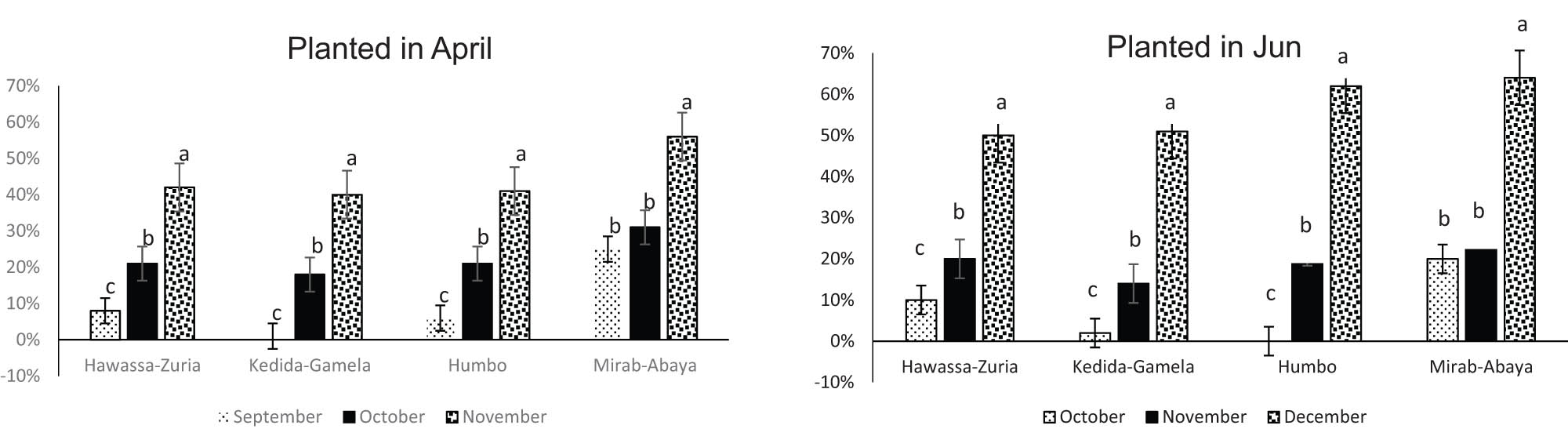

Sweetpotato planted in April (Belg season) and June (Meher season) and harvested in September and October, respectively, scored significantly lower weevil infestation compared to the delayed harvesting times in all areas. Planting in April and harvesting in November resulted in the highest weevil attacked root percentage of 64, 62, 51, and 50% in Mirab-Abaya, Humbo, Kedida-Gamela, and Hawassa-Zuria, respectively. Similarly, planting in June and harvesting in December also resulted in higher weevil damage of 56, 41, 40, and 42% in Mirab-Abaya, Humbo, Kedida-Gamela, and Hawassa-Zuria, respectively (Figure 2). Generally, it was observed that early harvesting during the time period between September and November resulted in significant reduction in weevil damaged roots than in late harvesting in December (Figure 2).

Percentage of weevil-infested roots for different harvest times in four districts in southern Ethiopia (2016). Values with different letters differ significantly at P < 0.001.

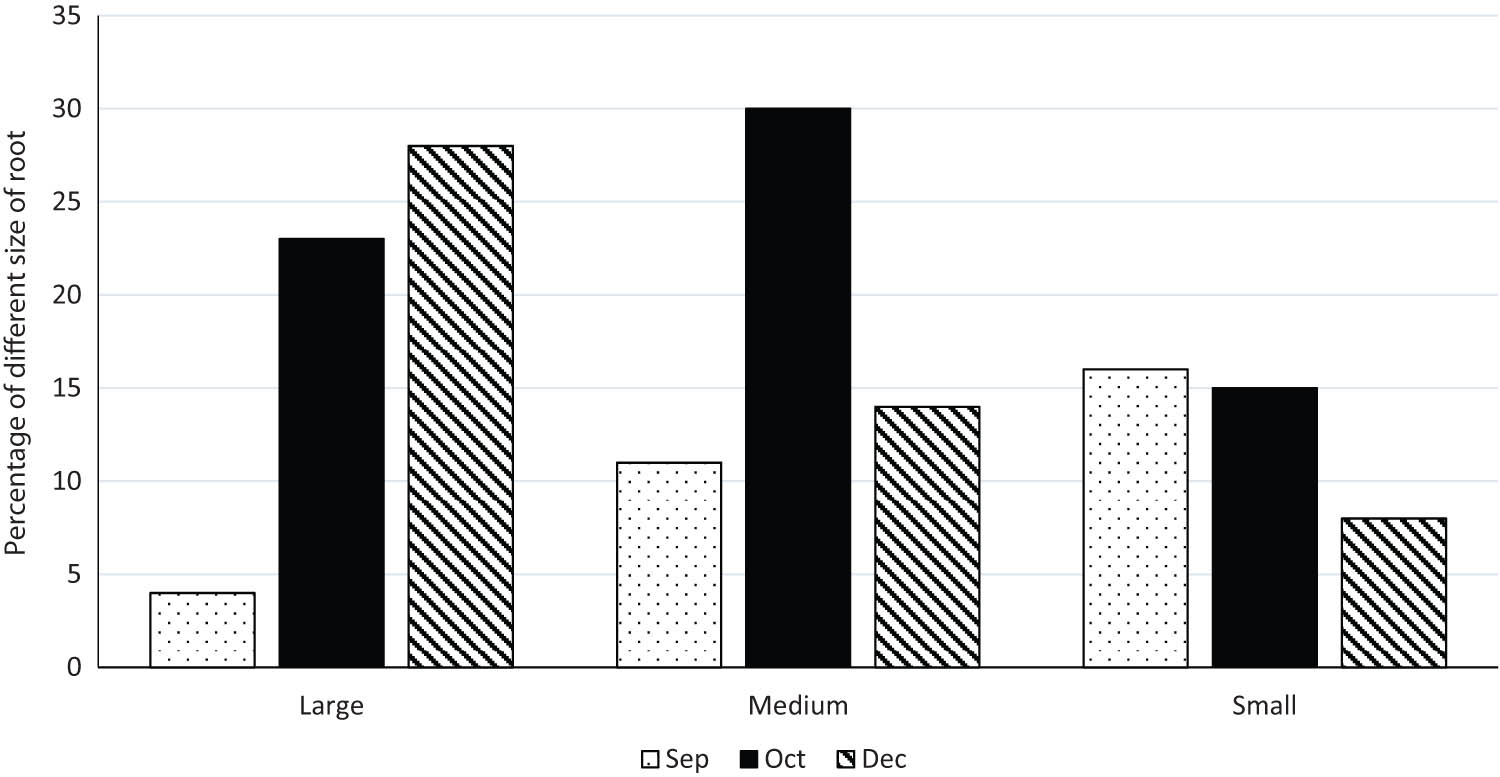

Harvesting time of roots affected the number of different size of roots, where planting in June and harvesting in October resulted in higher number of medium-sized roots. The number of large root size increased when harvested late in December and harvesting in September resulted in higher number of small-sized roots (Figure 3).

Percent of large, medium, and small sizes of roots in September, October and December harvesting.

4 Discussion

The present study shows that the Triple S method for planting material conservation results in a higher number of high-quality vine cuttings available for planting compared to the local conservation methods in the SNNPR in Ethiopia.

The validation experiment for comparing the Triple S method with the common local conservation methods was conducted in the dry season between December and April. During this time, average maximum temperatures in Mirab-Abaya, Hawassa-Zuria, Kedida-Gamela, and Humbo were 33, 30, 29, and 28°C, and average rainfall was 112, 150,144 and 100 mm, respectively (Figure 1). This means that the areas experienced drought stress with less than 1 mm of rainfall per day on average. Roots and vines conserved under the volunteer and shade/mulch treatment were exposed to the water and heat stress conditions which were too hot and dry to survive and grow vigorously. Survival rates using the local conservation methods were much lower in the districts Mirab-Abaya and Hawassa-Zuria where the dry season is longer with higher temperature and lower annual rainfall (Figure 1) than the Humbo and Kedida-Gamela districts where the condition is less harsher. However, Triple S performed best in all of these districts. This shows that the advantage of Triple S is greatest in the driest and hottest districts. According to the FRG members, damage by rodents and livestock were other factors contributing to the low survival rate in the two conventional methods unlike roots stored using the Triple S method which is stored in protected place. During the dry season, most plants that serve as a source of forage dry out making the sweetpotato vine conservation plots an easy target for grazing animals [8,11,21].

Although considerable care was taken to select clean roots that were not damaged by weevils or which had mechanical injury, not all roots stored under the Triple S method successfully survived the storage period due to drying and rotting. According to Namanda et al. [21], the main factors that affect the loss of roots stored under the Triple S method are drying and rotting. The drying mainly occurred as the upper sand cover was disturbed and the roots were exposed to high evapotranspiration. This loss in Triple S can be reduced by improving the selection and covering the upper layer of roots with a layer of 5–10 cm sand. If the sand on the upper layer is very thin, the roots will be exposed to the external environment leading to excessive transpiration, loss of water, subsequent drying, and death of root eyes, and/or attack by rodents or poultry. The water content of Kulfo and Awassa 83 is between 70 and 80% [2] which is higher than the water potential of the outside environment. Sweetpotato roots loose a significant quantity of moisture by transpiration especially after sprouting has started and may rapidly become dry or shrink [24]. To avoid the drying of roots during storage, there is a need to regularly follow up and monitor the storage container to remove any rotting roots and to make sure that all stored roots are covered properly. Although it is recommended to cover the top layer of Triple S storage by 5–10 cm of sand [21], it was observed that the upper layer of sand can be easily uncovered by chickens, rats, or moving the storage container rendering the top layer of roots vulnerable to damage. In some cases, drying was observed even with adequate sand cover indicating the importance to adjust the thickness of the upper sand cover for different sand types, coarseness, and storage volumes. However, a sand cover that is too thick can restrict air movement which limits the oxygen level in the storage medium. Sweetpotato roots are in continuous respiration during storage and therefore, there should be enough oxygen in the storage medium to avoid possible decay [30].

The higher survival rate of planting material conserved with the Triple S method compared to the local conservation methods was accompanied by a higher vine productivity. Our results show that with the Triple S method, up to 1,620 high quality 30 cm vine cuttings can be obtained from a basin with 40 roots from the first and ratoon harvest (assuming the same number from ratoon), which is sufficient to plant an area of 486 m2 (taking into account 1 m × 0.3 m planting spacing). This is in agreement with ref. [21] where it was reported that a basin of 40 roots stored with the Triple S method can generate around 1,500 cuttings by the onset of rains. Although there are many factors that influence vine yield of sweetpotato roots, root size and temperature are critical apart from availability of enough water for the growing sprouts [31].

Sweetpotato weevils lay their eggs inside the vines or storage roots and on hatching gradually burrow their way into the healthy parts unless protection measures are taken earlier [32]. Cuttings derived from the Triple S storage had a lower weevil damage rate than cuttings from the conventional conservation methods. The absence of a weevil source in the Triple S storage condition and the fact that with Triple S, sprouted roots are transplanted after the onset of rains might explain the observed lower weevil damage. However, plants of both the volunteer and the shade/mulch treatments were highly infected by weevils as plants were conserved under field conditions during the hottest and driest months of the year which is a conducive environmental condition for weevils [33]. This coupled with the already present weevil populations results in continued cycle of high weevil infestation. In addition to the dry and hot conditions, the fact that plants in both volunteer and shade/mulch treatments were exposed to weevils for a long period (3–6 months) increased the probability and severity of weevil infestation. Generally, there is high prevalence of sweetpotato virus disease in the study area is high and it is expected that on farm vine conservation results in a higher rate of virus infection compared to the isolated method of Triple S, due to a longer period of exposure to vectors responsible for virus. The most important viruses such as sweetpotato feathery mottle virus, sweetpotato chlorotic stunt virus, and the sweetpotato virus disease have been reported in the study area [34].

Sweetpotato planted in April and June and harvested in September and October gave highest number of medium-sized weevil-free roots than plants planted in both months but harvested in December. Previous studies in Ethiopia have shown that planting in June gave rise to higher yield of high quality roots [12] and delayed harvesting after rain secession results in higher rate of weevil infestation [5]. Planting out the sprouted roots mid-February to early March is important to multiply enough quantity of planting material for planting the sweetpotato crop in April and May. However, where water is available for irrigating the seedbeds, planting out the sprouted roots even earlier than mid-February will enable farmers to plant sweetpotato at the beginning of the Belg season.

5 Conclusion

The validation experiment proved that the root-based sweetpotato planting material conservation method called “Triple S” performs better than the conventional sweetpotato planting material conservation methods in the SNNPR region in Ethiopia in terms of quantity and quality of vines for planting available at the onset of rains. The ability to conserve planting material during the dry season is the main determinant to plant sweetpotato on time and harvest early to fill the hunger gap. Generally, the conservation of 40 roots is enough to multiply more than 820 cuttings at the start of the planting time. Assuming the same number of cuttings from the ratoon, it is possible to harvest 1,640 cuttings by conserving 40 roots in Triple S method which enables farmer to plant 486 m2 land just in few weeks after the rain started. The technology is best suited to conserve planting material of drought-sensitive sweetpotato varieties like the OFSP variety Kulfo. Therefore, it is recommended that promotion, distribution, and dissemination of new varieties are accompanied by promotion of the Triple S method of vine conservation. Since the success of the Triple S method is highly dependent on sprouting characteristics of the variety, it is furthermore important to consider root sprouting characteristics of a variety when recommending the number of medium-sized roots that should be conserved in Triple S to get required number of cuttings. In addition, future sweetpotato breeding programs in Ethiopia should consider incorporating the sprouting characteristics in variety development programs.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to acknowledge host farmers who hosted the experiment, participant farmers who are members of the farmer research groups, and experts of the office of agriculture of respective districts for facilitating the work with farmers. This study is undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers, and Banana (RTB) at the International Potato Center under the Sweetpotato Action for Security and Health Phase II (SASHA II) project which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [OPP1019987].

-

Funding information: This research is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) [OPP1019987] under the Sweetpotato Action for Security and Health in Africa Phase 2 (SASHA II) project.

-

Author contributions: M.C.H., M.M., J.W.L., and S.N.: proposal development, implementation, and writing of this research. E.V. and R.B.: reviewing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the CGIAR open access repository, https://data.cipotato.org/dataverse/dvn/?q=mihiretu. In addition, the datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] CSA. Statistical bulletin. Agricultural sample survey 2017/18; April 2018. p. 20–36.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gurmu F, Hussein S, Laing M. Diagnostic assessment of sweetpotato production in Ethiopia: Constraints, post-harvest handling and farmers’ preferences. Res Crop. 2015;16(1):104.10.5958/2348-7542.2015.00016.9Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Mota AA, Lachore ST, Handiso YH. Assessment of food insecurity and its determinants in the rural households in Damot Gale Woreda, Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia. Agric Food Sec. 2019;8(1):11.10.1186/s40066-019-0254-0Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Busse HA, Fofanah M, Schulz S, Lunt T, Tefera G. Wealth matters: prevalence and predictive indicators of food insecurity in the sidama and wolayta zones of southern Ethiopia. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2016;11(1):45–58.10.1080/19320248.2015.1045667Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Shonga E, Gemu M, Tadesse T, Urage E. Review of entomological research on sweet potato in Ethiopia. Discourse J Agriculture Food Sci. 2013;1(5):10.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Aldow AM. Factors affecting sweetpotato production in crop-livestock farming systems in Ethiopia [Masters of Science]. Norwegian: Norwegian University of Life Sciences; 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] McEwan M. Sweetpotato seed systems in sub-saharan Africa: a literature review to contribute to the preparation of conceptual frameworks to guide practical interventions for root, tuber and banana seed systems. Lima, Peru: RTB Working Paper; 2016. p. 45.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Gibson R. Review of sweetpotato seed system in east and southern Africa. Lima, Peru: International Potato Center; 2009. p. 48.10.4160/9789290603726Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Gurmu F. Sweetpotato research and development in Ethiopia: a comprehensive review. J Agric Crop Res. 2019;7(7):106–18.10.33495/jacr_v7i7.19.127Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Belehu T. Agronomical and physiological factors affecting growth, development and yield of sweetpotato in Ethiopia. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria; 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Namanda S. Current and potential systems for maintaining sweetpotato planting material in areas with prolonged dry seasons: a biological, social and economic framework. London, UK: University of Greenwich; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Markos D, Loha G. Sweetpotato agronomy research in Ethiopia: Summary of past findings and future research directions. Agriculture Food Sci Res. 2016;3(1):1–11.10.20448/journal.512/2016.3.1/512.1.1.11Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Gibson R, Kreuze J. Degeneration in sweetpotato due to viruses, virus-cleaned planting material and reversion: a review. Plant Pathol. 2015;64(1):1–15.10.1111/ppa.12273Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Sugri I, Maalekuu BK, Gaveh E, Kusi F. Compositional and shelf-life indices of sweet potato are significantly improved by pre-harvest dehaulming. Ann Agric Sci. 2019;64:113–20.10.1016/j.aoas.2019.03.002Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Parker ML, Low JW, Andrade M, Schulte-Geldermann E, Andrade-Piedra J. Climate change and seed systems of roots, tubers and bananas: the cases of potato in Kenya and Sweetpotato in Mozambique. The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 99–111.10.1007/978-3-319-92798-5_9Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Low JW, Mwanga RO, Andrade M, Carey E, Ball A-M. Tackling vitamin A deficiency with biofortified sweetpotato in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Food Security. 2017;14:23–30.10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Jenkins M, Shanks CB, Brouwer R, Houghtaling B. Factors affecting farmers’ willingness and ability to adopt and retain vitamin A-rich varieties of orange-fleshed sweet potato in Mozambique. Food Security. 2018;10(6):1501–19.10.1007/s12571-018-0845-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] McEwan M. Institutional arrangements for sustainable sweetpotato seed systems: terminal report. Gates Open Res. 2019;3:1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Jones D, Gugerty MK, Anderson CL. Sweet potato value chain: Ethiopia. Gates Open Res. 2019;3:1–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Adejuwon J, Olawole A, Adeoye N. Changing pattern in sweetpotato cultivation in semi-arid environment, Nigeria. J Appl Sci Environ Manag. 2019;23(7):1233–8.10.4314/jasem.v23i7.7Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Namanda S, Amour R, Gibson R. The Triple S method of producing sweet potato planting material for areas in Africa with long dry seasons. J Crop improvement. 2013;27(1):67–84.10.1080/15427528.2012.727376Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Abidin PE, Kazembe J, Atuna RA, Amagloh FK, Asare K, Dery EK, et al. Sand storage, extending the shelf-life of fresh sweetpotato roots for home consumption and market sales. J Food Eng. 2016:227–36. 10.17265/2159-5828/2016.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Garzon JG. Physical and chemical changes in different varieties of sweetpotatoes subjected to long-term storage at varying environmental conditions. 2012. p. 24–55. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/bitstream/handle/1840.16/7829/etd.pdf?sequence=2.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Atuna RA, Aduguba WO, Alhassan AR, Abukari IA, Muzhingi T, Mbongo D, et al. Postharvest quality of two orange-fleshed sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L) Lam] cultivars as influenced by organic soil amendment treatments. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6(6):1545–54.10.1002/fsn3.700Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Mpagalile J, Silayo V, Laswai H, Ballegu W, Kikuu C, editors. Effect of different storage methods on the shelf-life of fresh sweetpotatoes in Gairo, Tanzania. Tropical root and tuber crops: opportunities for poverty alleviation and sustainable livelihoods in developing countries. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Triennial Symposium of the International Society for Tropical Root Crops (ISTRC); 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Edmunds BA, Boyette MD, Clark CA, Ferrin DM, Smith TP, Holmes GJ. Postharvest Handling of Sweetpotato Roots. North Carolina University; 2016. https://plantpathology.ces.ncsu.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2013/12/sweetpotatoes_postharvest-1.pdf?fwd=no.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] George NA, Shankle M, Main J, Pecota KV, Arellano C, Yencho GC. Sweetpotato grown from root pieces displays a significant genotype × environment interaction and yield instability. HortScience. 2014;49(8):984–90.10.21273/HORTSCI.49.8.984Suche in Google Scholar

[28] La Bonte DR, Clark CA, Smith TP, Villordon AQ, Stoddard CS. ‘Bellevue’ sweetpotato. HortScience. 2015;50(6):930–1.10.21273/HORTSCI.50.6.930Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Jote A, Feleke S, Tufa A, Manyong V, Lemma T. Assessing the efficiency of sweet potato producers in the southern region of Ethiopia. Exp Agriculture. 2018;54(4):491–506.10.1017/S0014479717000199Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Wathome KA. Studies on Shrink-Wrapping and Low-Oxygen Storage of ‘Beauregard’ Sweetpotatoes (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam.). Louisiana State Univerisity; 1999. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8098&context=gradschool_disstheses.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Braun B. The maintenance of sweetpotato planting materials in Namibia: options for the development of a vine production and distribution system. Agricola. 2011;12:5.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Korada RR, Naskar SK, Palaniswami MS, Ray RC. Management of sweet potato weevil [Cylas Formicarius (Fab.)]: an overview. Indian Soc Root Crop. 2010;36(1):13.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Palaniswami MS, Visalakshi A, Mohandas N, Das L. Evaluation of soil application method of insecticides against cylas Formicarius (F.) and its impact on soil microflora in sweetpotato ecosystem. J Root Crop. 2002;28:6.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Mekonen S, Gurmu F, Tadesse T. Evaluation of elite sweetpotato genotypes for resistance to sweetpotato virus disease in Southern Ethiopia. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5(5):6–83.10.21474/IJAR01/4695Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Mihiretu C. Hundayehu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?