Abstract

To feed humans on a future Mars settlement, a sustainable closed agricultural ecosystem is a necessity. On Mars, both the faeces of astronauts as well as any plant residues or other organic waste needs to be (re)used to fertilise the present regolith. The activity of earthworms may play a crucial role in this ecosystem as they break down and recycle the dead organic matter. The contribution of worms to Mars regolith forming is yet an unexplored territory. The first goal of our research was to investigate whether earthworms (Caligonella genus and Dendrobaena veneta) can survive in Mars soil simulant. The second goal was to investigate whether earthworm activity on Mars soil simulant can stimulate the growth of crops, in our case Rucola. The third goal was if earthworm activity can enhance the effect of pig slurry on the growth of Rucola. In a 75-day greenhouse experiment, we sowed Rucola in Mars soil simulant as well as in silver sand as an Earth control, amended with pig slurry, plant residues, and earthworms. During the experimental period, we observed worm activity. At the end of the experiment, the worms had propagated both in the Mars soil simulant and Earth control. However, we found no significant effect of worm activity on plant biomass production. This was probably due to the relative short duration of the experiment, being one life cycle of Rucola. Adding pig slurry stimulated plant growth significantly as expected, especially for the Mars soil simulant.

1 Introduction

To feed astronauts on a future Mars settlement, a closed sustainable agricultural ecosystem will be a necessity [1,2]. Crops may be flown in, but that is costly and inefficient. Moreover, it is an uncertain factor in the food supply, since a supply ship may fail. Crop growth on Mars itself will contribute to the safe (permanent) stay of astronauts on Mars. There are basically four different ways possible to grow crops on Mars, but we are assuming that it all will be indoors or underground, given the hazardous Mars environment with a very low air pressure (6 hPa, about 0.6% of Earth pressure at sea level). Main components of Mars atmosphere are about 95% CO2, 2.6% N2, 1.9% Ar, 0.16% O2, and 0.06% CO, all volume percents. The average temperature lies around –63°C with a variation from –140 to + 20⁰C [3]. Moreover, due to the absence of a planet wide protecting magnetic field, cosmic radiation reaches the planet surface giving a 17 times higher radiation than on Earth, which may affect plant growth [4,5].

The first possible option to grow crops is aeroponics [6]. The second option is aquaponics, as is investigated by e.g. Fu et al. [7]. A third option is underwater growth e.g. algae and fish [8]. The fourth option is to use the soil that is present on Mars, the Mars regolith, and the present water (as ice) on Mars [9,10]. The last option is further explored in this article, based on the idea to use the resources available on Mars as much as possible.

Martian regolith is not available on Earth for research. Therefore, NASA has created soil simulants for research purposes. Two variants developed under supervision of NASA are available, the JSC-1A [11], made in 1997. The second is the Mojave Mars Soil (MMS) made in 2007 and originates from the Mojave Desert near Saddleback Mountain [12]. In this experiment we applied the more recent MMS simulant (for an extensive description refer Peters et al. [12], their Table 1 and for a comparison with Mars measurements their Table 2). Important for plant growth are the absence of life, the almost absence of nitrogen and ammonium, and the absence of complicated organic molecules. One of the physical features of the MMS is that the minerals that make up the soil are quite sharp, as they would be on Mars. This may have consequences for all life in the soil. Edges of the minerals may be so sharp that it could damage living cells, including roots of plants or the gut of worms, leading to leaking of cell content and in the end possible death of plants and animals.

Overview of the experimental set-up

| Worm | Manure | Soil type | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | Earth | NME |

| − | + | Mars | NMM |

| − | − | Earth | NNE |

| − | − | Mars | NNM |

| + | + | Earth | WME |

| + | + | Mars | WMM |

| + | − | Earth | WNE |

| + | − | Mars | WNM |

For soil type Earth indicates application of Earth soil and Mars indicates application of Mars soil simulant MMS. The code for the treatments is used in all other tables and figures.

Properties of the pig slurry

| Parameter | Analysis method | (kg fresh weight−1) |

|---|---|---|

| DW (%) | Oven dried and weighed | 2.9 |

| Specific weight (kg/L) | Weighing 100 mL at 20°C | 1.008 |

| pH | Electrode at 20°C | 8.06 |

| Ntot (mg/kg) | H2SO4/Se/H2O2 destruction and measured with a segmented flow analyser | 3861.7 |

| NH4-N (mg/kg) | Extraction with 1 M KCl and measured with a segmented flow analyser | 1,284 |

| Ptot (mg/kg) | H2SO4/Se/H2O2 destruction and measured with a segmented flow analyser | 840 |

| Ortho P (mg/kg) | Centrifuged, filtrated, and measured with a segmented flow analyser | 146 |

In a closed agricultural system non-eaten parts of cultivated crops must be returned into the agricultural system. A key step in the breakdown of these organic “waste products” will be the breakdown of organic matter by earthworms [13,14].

Another option to manure the soil is to bind N2 from the air by nitrogen fixing bacteria that live in symbiosis with plants [15] or by cyanobacteria [16], thus enriching the soil with ammonia. Human faeces can also be a source of nutrients and should therefore also be returned into the agricultural system as manure for the plants. Instead of the application of human faeces, for experiments it is also an option to use pig slurry, which is easier and safer to handle, especially given the pathogen content in human faeces [17]. We added the pig slurry to review the effect on plant growth compared to the expected manuring effect of the worm activity.

Earthworms eat the organic matter, mixing it in the process with soil in their gut, while extracting nourishing elements and then excreting a mixture of broken-down organic matter and soil. Bacteria can then further breakdown the organic matter and thus release nutrients for the next generation of plant growth [13]. The earthworms are also an important factor in the forming of soil by bringing organic matter into the soil [14]. They also dig burrows, which promotes draining of the soil and they make water supply easier. In earlier experiments with Mars soil simulant, water supply proved to be problematic due to the hydrophobic character of the simulant [9]. Adding organic matter to the soil proved to solve this problem [10,18]. The burrows of the earthworms also help aerating the soil so that the roots of the plants can take up the oxygen they need for their maintenance respiration [19].

The first goal of this experiment was to investigate whether the earthworms can survive in Mars soil simulant and whether they show normal activity as digging burrows and decomposing organic matter. The second goal was to investigate if the worm activity stimulates plant growth also in combination with the addition of pig slurry. To this end, a greenhouse experiment was set up with MMS and Earth soil control and the addition of pig slurry and earthworms. The effects of the addition were monitored using Rucola (Eruca sativa) as a bio-indicator.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Experimental design and greenhouse settings

The experiment lasted from 1-9-2017 to 15-11-2017 and was carried out in a greenhouse with a minimum temperature of 20°C and 65% humidity. Daytime lasted 16 h. Lamps yielding 80 µmol (HS2000 from Hortilux Schréder) were used if the sunlight intensity was below 150 W/m².

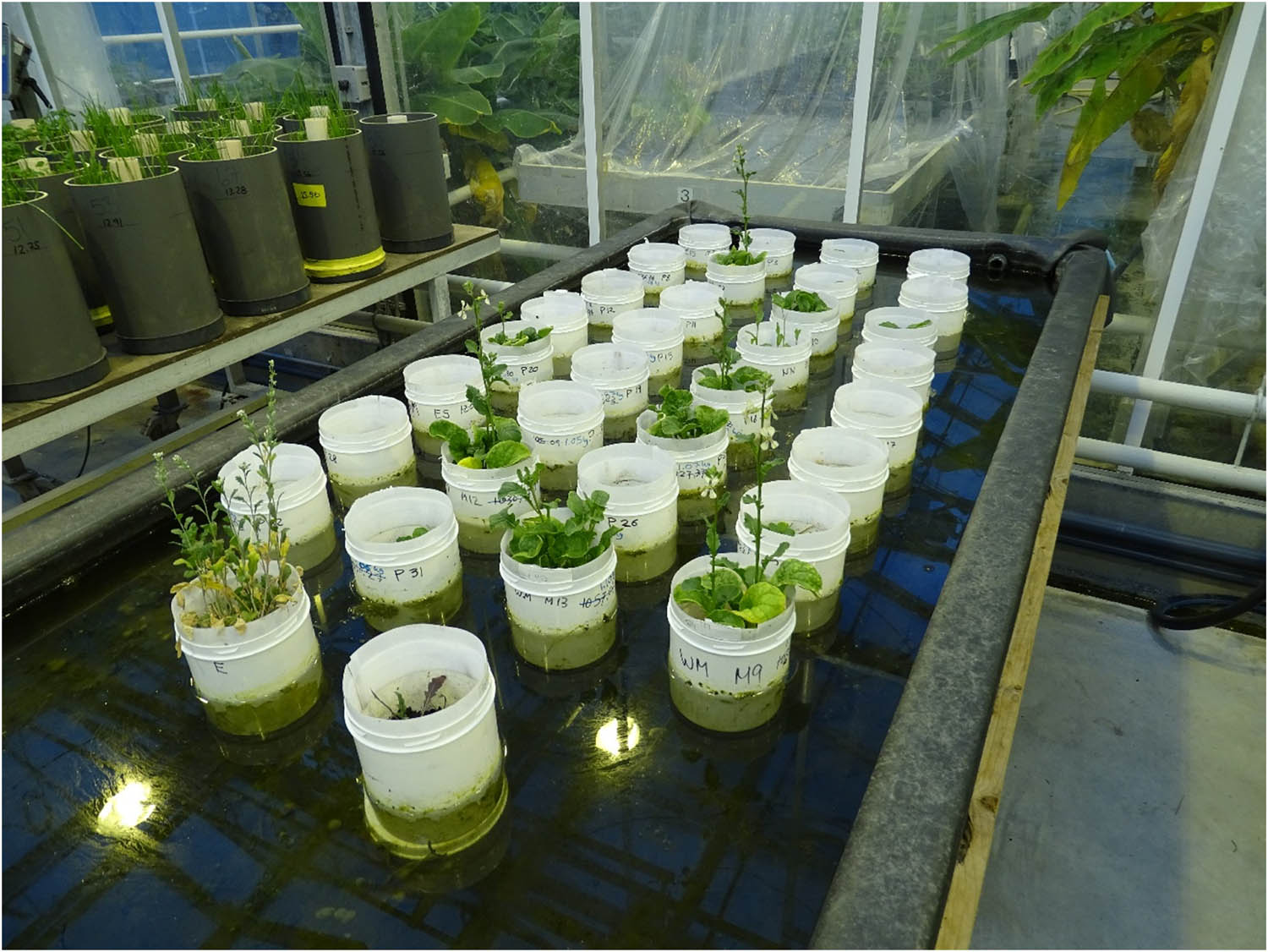

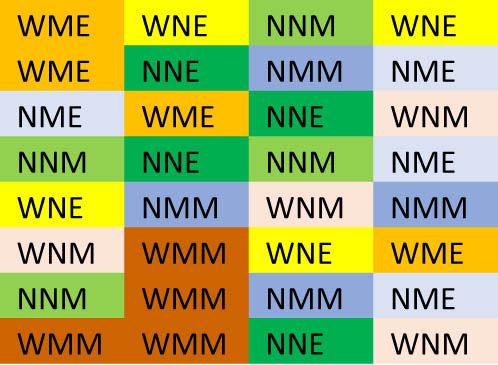

The experiment had a full factorial design of three factors of two levels each (2 * 2 * 2, with n = 4); earthworm, pig slurry, and “soil,” giving in total 2 (worm, no worm) × 2 (manure, no manure) × 2 (Mars soil simulant, Earth control) × 4 (replicas) 32 pots (also Table 1). The treatments were randomly placed in a water bath (Figure 1). Temperatures in the greenhouse are optimal for plants, but too high for the worms. To obtain more optimal conditions for the worms, the pots were placed in a streaming water bath. The water was cool groundwater pumped up at the site with a temperature of approximately 10°C.

Set up of the experiment. Pots and treatments were placed randomly in the water bath. The photo shows the pots placed in a cold-water bath for optimal temperature conditions of the soil for the worms. A schematic diagram of the pot set up can be found in Appendix Figure 1.

2.2 Pots

The experiment was carried out in circular pots with a radius of 5.0 and 15.0 cm height (1.2 l, by NIPAK, The Netherlands). Velcro (5 cm) was glued to the inside top of the pots to prevent worms from escaping the pots (as suggested and tested by Lubbers and van Groenigen, [20]).

2.3 Soil and water

In contrary to our earlier experiments, the Mojave Mars Simulant (MMS) was used instead of the JSC-1A [9,10]. The MMS soil, delivered by the Martian garden (www.themartiangarden.com), was used as the next generation Mars soil simulants. Despite its more recent origin, this simulant does not contain perchlorate, which was recently found in Martian soil and believed to be widespread on Mars [21,22,23]. As Earth control, we used silver sand, sand that is nutrient poor and also lacking organic material. We used 800 g MMS and 700 g silver sand per pot.

For both soils, the water holding capacity (WHC) was determined. For MMS the WHC was 21% and for silver sand 23% (soil weight). Water was added to both the soils till the saturation point. During the experiment, on 12-10-2017, water content was raised to 26% for MMS and 30% for Earth control soil to keep the pots moist to compensate for increased evaporation due to plant growth. Water was supplied twice a week bringing the pots back to their original weight.

2.4 Organic matter and manure

The soils were mixed with the harvested above ground organic matter from a previous growth experiment on Mars soil simulant and Earth control [10]. 20 g per pot was added as rough material and mixed through the upper 10 cm of the soil. 10 g ball milled organic matter was added per pot on top of the soil as a litter layer. Both the organic matter fractions were added after water was added to the soils. This gives roughly 3.8% organic matter in MMS and 4.3% organic matter in silver sand (dry weight, DW). The organic matter mainly contained above ground non-eaten parts of rye, cress, green bean, pea, and carrot. The organic matter contained on average 18.8 g/kg DW (±7.0) potassium, 12.4 g/kg DW (±3.6) nitrogen, and 2.16 g/kg DW (±1.00) phosphorous. The variation between the samples taken from the organic matter was quite large, hence the large standard errors. The N content is rather low, but not outside the range what is found for N-content in organic matter.

12.5 mL of Pig slurry was added as manure (Table 2 shows its content), after water and organic matter were added. It was added on top of the soil. The slurry did sink in the silver sand immediately after adding to the soil, in the MMS soil it took minutes to sink in. This shows the hydrophobic character of the MMS, which was also found for the JSC-1A we used in an earlier experiment [9].

2.5 Worms

Two species of worms were added to the soils. The first were from the Caligonella genus, the most common endogenic species found in The Netherlands. They were caught in the grass field next to the institute. The second worm species was Dendrobaena veneta, a compost worm. These worms were supplied by “De Polderworm” in Rutten, The Netherlands. Adult worms were put on tissue paper and water for two days to empty their guts, to prevent interference of gut material with the experiment. Each worm treatment in the experiment received two Caligonella and two Dendrobaena worms. The worms were added after germination and establishment of the seedlings of the Rucola on 22-9-2017, 3 weeks after the start of the experiment.

2.6 Plant growth

To investigate the effect of the treatments on plant aboveground biomass growth, we used a round leaved Rucola cultivar (argula or rocket, Eruca sativa Mill. cv Sparkle RZ, delivered by Rijk Zwaan) as bio-indication. A teaspoon full of seeds (50 ± 5) were sown randomly in each pot. After germination, the young plants were not thinned. At the end of the experiment, aboveground biomass was harvested and fresh and dry weights were measured. The biomass was dried in an oven for 2 days at 70°C.

2.7 Statistics

A full factorial 3-way-ANOVA was carried out for both fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) of the Rucola for all treatments and interactions in SPSS (IBM, [24]). Statistically significant differences between DWs was tested with a student t-test (p = 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Earthworms

As long as the experiment lasted, worms did escape the pots despite the Velcro that should prevent this [20]. They were removed from the water bath but not put back in the pots, since they had not been labelled per pot. During the experiment all pots were infested with fungi, some formed even mushrooms. The mushrooms were removed, the fungi were not treated.

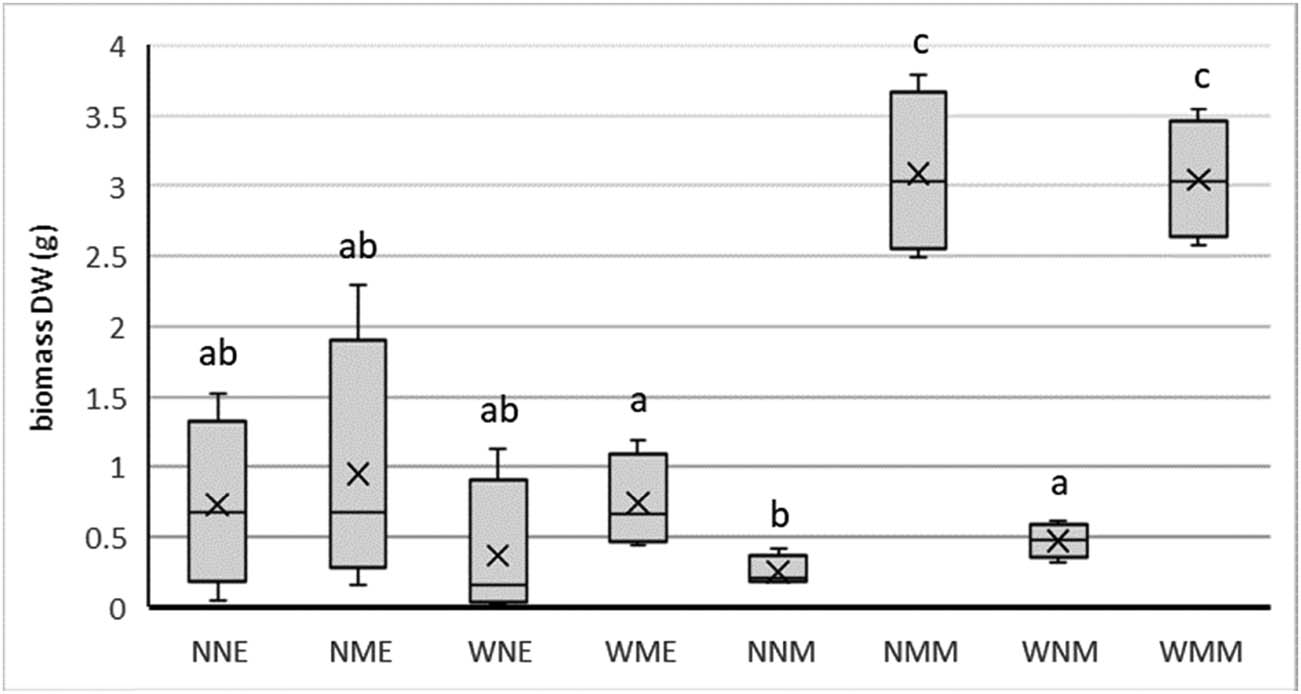

At the end of the experiment worms were retrieved from the soil. Most of the worms had by then escaped from the pots (Appendix Table 2). However, two young worms were found in two different pots in the Mars soil simulant and one in the Earth control. Recovered worms from the pots were all alive and lively. The effect of the worms on the aboveground biomass growth (DW) of Rucola was not significant (Figure 2; for the statistics see Appendix Table 3). Comparing the treatments NNE and WNE, NME and WME, NNM and WNM, and NMM and WMM in Figure 2 clearly shows that there are no differences between the paired treatments with and without worms on the DW.

Box plot of the harvested biomass (dry weight) per treatment. Treatment code indicates for first letter for worm (W) or no worm (N) added; for the second letter for manure (M) or no manure (N) added; for the third letter for Earth control (E) and Mars soil simulant (M). Different letters indicate significant differences at p = 0.05.

3.2 Biomass growth

All pots produced growing plants. However, the difference between the treatments were huge (Figure 2; Appendix Tables 3 and 4). The pig slurry treatment yielded the highest biomass (DW) of Rucola and differed statistically significant from the non-treated pots. The MMS soil simulant gave a significant higher biomass production than the Earth control (p = 0.010). This was mainly due to the relative low biomass production of the pig slurry addition to the Earth control. The two-way interaction between planet and manure and the three-way interaction between planet, manure and earthworm were (just) significant. No significant interactions were found for the harvested DW of the aboveground biomass.

4 Discussion

The worms did survive in the MMS soil simulant, indicating that uptake of sharp soil particles, present in the MMS, is not a major problem for their survival. The fact that they were healthy is also supported by the young worms that were born during the experiment. Many worms escaped from the pots, but there was no difference between the Earth control and the MMS soil simulant. Another indicator of good health of the worms were the burrows dug and the poop heaps found on the surface of some of the pots. Soil forming processes were observed in the pots with the worms. The effect of the worms on the biomass growth, however, was absent despite our expectation that the worms would positively influence biomass production. The absence of a positive stimulus may also be due to the time the experiment lasted and the time it takes for worms to process the organic matter and, subsequently, for bacteria to mineralise the worm excrement and release the nutrients for the plants [13,14,25].

The growth of Rucola was clearly stimulated by the addition of pig slurry. The fact that adding manure stimulates the growth is not very surprising and the effect is well known [25,26]. Pig Slurry was chosen because it mimics the addition of human faeces well [27]. In a closed agricultural system, the human faeces will have to be brought back in the system, otherwise there will be a loss of nutrients from the system, especially nitrate, which is not easily replaced. The human faeces will have to be sterilised before application, to prevent unwanted bacteria from the human gut to enter the agricultural system. Worms can also play a role in bringing the faeces back into the soil when it will be applied to the soil. However, in this experiment, the interaction between worm and manure was not significant (p = 0.685).

The biomass production (DW) of Rucola was higher on the Mars soil simulant compared to the Earth control (p = 0.010). These results are in line with the earlier research of Wamelink et al. [9]. In their experiment, the Earth control was nutrient poor soil as well. In later research, Wamelink et al. [10] used organic soil as a control. Our expectation is that when this would have been applied in this experiment as well, the Earth control would have outperformed the MMS. However, the idea was to build a soil from Earth sand as well as from the MMS and then the approach followed here is more appropriate. Effects can be better compared and studied and the Caligonella genus fits these circumstances better.

The fresh weight analyses were in line with the DW; however, here also two interactions were found to be just significant, for the two-way interaction between planet and manure (p = 0.033) and the three-way interaction between planet, manure and earthworm (p = 0.042; Appendix Table 4). The significant effect of the three-way interaction is most likely a result of the two-way interaction between planet and manure. We cannot explain this effect.

We used Dendrobaena veneta and worms from the Caligonella genus. D. veneta is a mulching species and is used to high temperatures (The supplier Polderworm breeds them at around 20°C). Worms of the Caligonella genus, however, like it colder. To accommodate the Caligonella genus worms, we put the pots in a cold-water bath. However, this is suboptimal for D. veneta and plant growth. For this first trial experiment this is acceptable, but it is less optimal, and the water bath complicates the experimental set up. Therefore, in the next experiments, we recommend using worms that thrive at 20°C and can mix organic matter with soil.

One of the most disputed issues is the presence of perchlorate in the Mars soil, at least in the upper layers [21,22,23,28]. There was no perchlorate present in the JSC-1A or the MMS soil simulant used here, nor was it added to its successors [11,12,29]. Perchlorate is poisonous for plants and humans and most likely for earthworms as well. To test the effect, it could be added to the soil simulant, as was done by Oze et al. [30]. They found a significant negative effect of perchlorate on both the germination and growth, if any, on a Mars soil simulant. This result was confirmed by Eichler et al. [31]. However, it remains disputable if the perchlorate is present everywhere on Mars including deeper soil layers and in caves.

5 Conclusion

The added worms were clearly active during the experiment and showed to be able to propagate. However, the worms did not significantly affect the plant biomass production, probably due to the short experimental period; a longer experiment is needed to assess whether or not there is a long-term effect.

The addition of pig slurry stimulated plant growth significantly as expected, especially in the Mars soil simulant. The biomass production on Mars soil simulant was higher than on the nutrient poor Earth soil.

Acknowledgments

The pig slurry was kindly provided by Willeke van Tintelen.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: G.W.W.W. designed the experiment, helped out with the experiment, and wrote the article, L.S. did the day-to-day care and the harvest, J.Y.F. supervised and did the day-to-day care and the harvest, and I.L. designed the experiment, and carried out the statistics.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Appendix

Fresh and dry weights of the Rucola.

| Code | Treatment | Fresh weight (g) | Dry weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E12 | NME | 4.4 | 0.63 |

| E16 | NME | 1.13 | 0.16 |

| E4 | NME | 9.301 | 2.29 |

| E8 | NME | 3.89 | 0.71 |

| M12 | NMM | 16.79 | 3.33 |

| M16 | NMM | 15.95 | 3.79 |

| M4 | NMM | 14.7 | 2.74 |

| M8 | NMM | 15.65 | 2.49 |

| E10 | NNE | 4.68 | 0.59 |

| E14 | NNE | 0.7 | 0.05 |

| E2 | NNE | 9.29 | 1.52 |

| E6 | NNE | 4.65 | 0.75 |

| M10 | NNM | 2.73 | 0.41 |

| M14 | NNM | 1.53 | 0.19 |

| M2 | NNM | 1.05 | 0.22 |

| M6 | NNM | 1.52 | 0.18 |

| E1 | WME | 7.57 | 0.8 |

| E13 | WME | 4.23 | 1.19 |

| E5 | WME | 3.7 | 0.53 |

| E9 | WME | 2.28 | 0.44 |

| M1 | WMM | 13.39 | 3.21 |

| M13 | WMM | 17.74 | 3.54 |

| M5 | WMM | 15.28 | 2.57 |

| M9 | WMM | 13.37 | 2.86 |

| E11 | WNE | 0.48 | 0.02 |

| E15 | WNE | 0.49 | 0.23 |

| E3 | WNE | 0.62 | 0.07 |

| E7 | WNE | 6.73 | 1.13 |

| M11 | WNM | 3.45 | 0.32 |

| M15 | WNM | 3.1 | 0.46 |

| M3 | WNM | 4.2 | 0.61 |

| M7 | WNM | 3.14 | 0.49 |

The code gives the soil type (E for Earth control and M for Mars soil simulant) and pot number. For treatment W/N first letter for worm or no worm added; for the second letter M/N for manure or no manure added; for the third letter E/M for Earth control and Mars soil simulant.

Number of worms added and retrieved.

| Added | Retrieved | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Code | Caliginosa | Dendrobaena | Total | Caliginosa | Dendrobaena | Baby |

| WM | E1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | E2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | E3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | E4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | E5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | E6 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | E7 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| NM | E8 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | E9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | E10 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | E11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | E12 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | E13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | E14 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | E15 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | E16 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | M1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | M2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | M3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | M4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | M5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| NN | M6 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | M7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | M8 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | M9 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| NN | M10 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | M11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | M12 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WM | M13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NN | M14 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| WN | M15 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| NM | M16 | 0 | 0 | ||||

Type gives the treatment: with W/N first letter for worm or no worm added; M/N for manure or no manure added. Code gives the soil type, with E for Earth control and M for Mars soil simulant; the number is the pot number. In total 16 worms that escaped were retrieved from the water bath. We found 16 worms in the pots, of which 3 were offspring. Thus, of the 64 worms added 29 were accounted for.

Average FW and DW of the aboveground biomass of Rucola.

| Treatment | FW | DW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg | S.E. | Avg | S.E. | |

| NME | 4.68 | 3.40 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| NMM | 15.77 | 0.86 | 3.09 | 0.59 |

| NNE | 4.83 | 3.51 | 0.73 | 0.61 |

| NNM | 1.71 | 0.72 | 0.25 | 0.11 |

| WME | 4.4 | 2.24 | 0.74 | 0.34 |

| WMM | 14.95 | 2.07 | 3.05 | 0.42 |

| WNE | 2.08 | 3.10 | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| WNM | 3.47 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.12 |

Treatment codes are built up as follows: first letter for earthworm (W) or no worm (N) added; for the second letter for manure (M) or no manure (N) added; the third letter for Earth control soil (E) and Mars soil simulant (M) added. Results per pot can be found in Appendix Table 1.

Results of the 3-way-ANOVA for FW and DW for all treatments and interactions.

| Source | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F | sign. (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | Model | 16.455 | 8 | 2.057 | 21.404 | 0.000 |

| Planet | 0.987 | 1 | 0.987 | 10.269 | 0.004 | |

| Manure | 2.557 | 1 | 2.557 | 26.612 | 0.000 | |

| Earthworm | 0.018 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.188 | 0.668 | |

| Manure * earthworm | 0.026 | 1 | 0.026 | 0.267 | 0.610 | |

| Planet * earthworm | 0.321 | 1 | 0.321 | 3.339 | 0.080 | |

| Planet * manure | 0.490 | 1 | 0.490 | 5.095 | 0.033 | |

| Planet * manure * earthworm | 0.443 | 1 | 0.443 | 4.609 | 0.042 | |

| Error | 2.306 | 24 | 0.096 | |||

| Total | 18.762 | 32 | ||||

| DW | Model | 7.656 | 8 | 0.957 | 5.950 | 0.000 |

| Planet | 1.256 | 1 | 1.256 | 7.811 | 0.010 | |

| Manure | 3.918 | 1 | 3.918 | 24.359 | 0.000 | |

| Earthworm | 0.015 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.093 | 0.763 | |

| Manure * earthworm | 0.027 | 1 | 0.027 | 0.168 | 0.685 | |

| Planet * earthworm | 0.277 | 1 | 0.277 | 1.719 | 0.202 | |

| Planet * manure | 0.565 | 1 | 0.565 | 3.511 | 0.073 | |

| Planet * manure * earthworm | 0.333 | 1 | 0.333 | 2.071 | 0.163 | |

| Error | 3.860 | 24 | 0.161 | |||

| Total | 11.516 | 32 |

Planet indicates the effect of the difference between Earth potting soil and Mars soil simulant MMS. Data were natural log transformed to gain normal distribution. In bold, p-values <0.05.

Schematic diagram of the pot set up of the experiment. Treatment codes are built up as follows: first letter for earthworm (W) or no worm (N) added; for the second letter for manure (M) or no manure (N) added; the third letter for Earth control soil (E) and Mars soil simulant (M) added.

References

[1] Horneck G, Facius R, Reichert M, Rettberg P, Seboldt W, Manzey D, et al. HUMEX, a study on the survivability and adaptation of humans to long-duration exploratory missions, part II: Missions to Mars. Adv Space Res. 2006;38:752–9. 10.1016/j.asr.2005.06.072 Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Cousins CR, Cockell CS. An ESA roadmap for geobiology in space exploration. Acta Astron. 2016;118:286–95.10.1016/j.actaastro.2015.10.022Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Sagan C, Mullen G. Evolution of atmospheres and surface temperatures. Science. 1972;177(4043):52–6.10.1126/science.177.4043.52Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Guo J, Slaba TC, Zeitlin C, Wimmer-Schweingruber RF, Badavi FF, Böhm E, et al. Dependence of the Martian radiation environment on atmospheric depth: Modeling and measurement. J Geophys Res Planets. 2017;122:329–41. 10.1002/2016JE005206.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Tack N, Wamelink GWW, Denkova AG, Schouwenburg M, Hilhorst H, Wolterbeek HT, et al. Influence of Martian radiation-like conditions on the growth of Secale cereale and Lepidium sativum. Front Astron Space Sci. 2021;8:665649. 10.3389/fspas.2021.665649.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Maggi F, Pallud C. Space agriculture in micro- and hypo-gravity: A comparative study of soil hydraulics and biogeochemistry in a cropping unit on Earth, Mars, the Moon and the space station. Planet Space Sci. 2010;58:1996–2007.10.1016/j.pss.2010.09.025Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Fu Y, Li L, Xie B, Dong C, Wang M, Jia B, et al. How to establish a bioregenerative life support system for long-term crewed missions to the moon or mars. Astrobiology. 2016;16:925–36.10.1089/ast.2016.1477Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Bluem V, Paris F. Possible applications of aquatic bioregenerative life support modules for food production in a Martian base. Adv Space Res. 2003;31:77–86. 10.1016/S0273-1177(02)00659-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Wamelink GWW, Frissel JY, Krijnen WHJ, Verwoert MR, Goedhart PW. Can plants grow on Mars and the Moon: a growth experiment on mars and moon soil simulants. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103138. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103138.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Wamelink GWW, Frissel JY, Krijnen WHJ, Verwoert MR. Crop growth and viability of seeds on Mars and Moon soil simulants. Open Agriculture. 2019;4:509–16. 10.1515/opag-2019-0051.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Rickman D, McLemore CA, Fikes J. Characterization summary of JSC-1A bulk lunar mare regolith simulant; 2007. http://www.orbitec.com/store/JSC-1AF_Characterization.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Peters GH, Abbey W, Bearman GH, Mungas GS, Smith JA, Anderson RC, et al. Mojave Mars simulant-characterization of a new geologic Mars analog. Icarus. 2008;197:470–9.10.1016/j.icarus.2008.05.004Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Edwards CA, Fletcher KE. Interactions between earthworms and microorganisms in organic-matter breakdown. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1988;24:235–47.10.1016/0167-8809(88)90069-2Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Edwards CA, Hendrix PF, Arancon NQ. Biology and ecology of Earthworms. 3rd edn. US: Springer; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Harris F, Dobbs J, Atkins D, Ippolito JA, Stewart JE. Soil fertility interactions with Sinorhizobium-legume symbiosis in a simulated Martian regolith; effects on nitrogen content and plant health. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257053.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Verseux C, Heinicke C, Ramalho TP, Determann J, Duckhorn M, Smagin M, et al. A low-pressure, N2/CO2 atmosphere is suitable for Cyanobacterium-based life-support systems on Mars. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:611798. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.611798.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Tyrrel SF, Quinton JN. Overland flow transport of pathogens from agricultural land receiving faecal wastes. J Appl Microbiol Symp Suppl Vol. 2003;949(32):87S–93S.10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.10.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Caporale AG, Vingiani S, Palladino M, El-Nakhel C, Duri LG, Pannico A, et al. Geo-mineralogical characterisation of Mars simulant MMS-1 and appraisal of substrate physico-chemical properties and crop performance obtained with variable green compost amendment rates. Sci Total Environ. 2020;720:137543. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137543.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Raich JW, Tufekcioglu A. Vegetation and soil respiration: Correlations and controls. Biogeochemistry. 2000;48:71–90.10.1023/A:1006112000616Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Lubbers IM, van Groenigen JW. A simple and effective method to keep earthworms confined to open-top mesocosms. Appl Soil Ecol. 2013;64:190–3.10.1016/j.apsoil.2012.12.008Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Hecht MH, Kounaves SP, Quinn RC, West SJ, Young SM, Ming DW, et al. Detection of perchlorate and the soluble chemistry of martian soil at the phoenix lander. Science. 2009;325:64–7.10.1126/science.1172466Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Chevrier VF, Hanley J, Altheide TS. Stability of perchlorate hydrates and their liquid solutions at the phoenix landing site, Mars. Geophys Res Lett. 2009;36:L1020.10.1029/2009GL037497Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Clark BC, Kounaves SP. Evidence for the distribution of perchlorates on Mars. Int J Astrobiol. 2016;15:311–5.10.1017/S1473550415000385Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Nie NH, Bent DH, Hull CH. SPSS: Statistical package for the social sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1970.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Atiyeh RM, Arancon N, Edwards CA, Metzger JD. Influence of earthworm-processed pig manure on the growth and yield of greenhouse tomatoes. Bioresour Technol. 2000;75:175–80.10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00064-XSuche in Google Scholar

[26] Herrero M, Thornton PK, Notenbaert AM, Wood S, Msangi S, Freeman HA, et al. Smart investments in sustainable food production: revisiting mixed crop-livestock systems. Science. 2010;327:822–5.10.1126/science.1183725Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Kararli TT. Comparison of the gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of humans and commonly used laboratory animals. Biopharm Drug Disposition. 1995;16:351–80.10.1002/bdd.2510160502Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Navarro-González R, Vargas E, De La Rosa J, Raga AC, McKay CP. Reanalysis of the Viking results suggests perchlorate and organics at midlatitudes on Mars. J Geophys Res E: Planets. 2010;115:E12010.10.1029/2010JE003599Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Zeng X, Li X, Wang S, Li S, Spring N, Tang H, et al. JMSS-1: a new Martian soil simulant. Earth, Planets Space. 2015;67:72. 10.1186/s40623-015-0248-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Oze C, Beisel J, Dabsys E, Dall J, North G, Scott A, et al. Perchlorate and agriculture on Mars. Soil Syst. 2021;5(37). 10.3390/soilsystems5030037.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Eichler A, Hadland N, Pickett D, Masaitis D, Handy D, Perez A, et al. Challenging the agricultural viability of martian regolith simulants. Icarus. 2021;354:114022. 10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114022.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Gerrit Willem Wieger Wamelink et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?