Abstract

The steady decline in agrobiodiversity is not only a significant threat to the genetic stability of the rural agroecosystems but also places a huge impediment to the realization of global food security. Climate change and decline in arable land is forcing subsistence farmers to abandon the less productive but well-adapted local crops for the newer short term and drought-tolerant crops decimating agrobiodiversity further. This study sought to establish the on-farm species and genetic diversity status among the family farming systems of semiarid areas of Eastern Kenya and effect on food security, agrobiodiversity management strategies, their perception of climate change, and climate change coping strategies. Structured questionnaires were administered to 92 active farmers in Embu, Kitui, and Tharaka Nithi Counties of Eastern Kenya. On-farm diversity, socio-economic factors, and their impact on agrobiodiversity were determined. Possible correlations were established using Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient. Remarkably, 26 crop species were recorded where legumes and cereals were dominant. According to the Shannon–Wiener Diversity index (H′), Tharaka Nithi County recorded the highest legumes and cereals diversity indices of 3.436 and 3.449, respectively. Food shortage was reported by over 50% of the respondents in the study area. The existence of weaker adaptive measures in response to climate change was evident. Family farming systems that had higher crop diversification and integrated livestock rearing in their farms were more food secure. Improved mitigation to climate change and diversification of farming systems among the smallholder farms is essential not only in boosting the food security but also in establishment of sustainable farming systems resilient to climate change.

1 Introduction

Agrobiodiversity is an essential resource playing a critical role in providing the needs of livelihoods and ensuring not only the genetic stability of many agroecosystems but also the quality of life in myriad ways. Recent decades have witnessed a rapid decline in biodiversity in many ecosystems with agricultural biodiversity being not an exemption [1]. According to Food and Agriculture Organization, about 70% of crop genetic diversity have been lost in the recent past [2] with the loss attributable to climate change and the changing socio-economic and cultural dynamics of agrobiodiversity. Moreover, biodiversity loss is expected to worsen further with climate change and shrinking of arable land, as stakeholders focus on high yielding hybrids. With the loss of agrobiodiversity, man also loses the chance to have richer and healthier diets and sustainable food systems. Notably, 33% of the world population is suffering from a micronutrient deficiency, with another close to 2 billion struggling with obesity [2,3,4]. The formal economic models postulate that in the absence of effective counteraction, the effect of climate change will be equivalent to the annual loss of at least 5% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product [5]. The economic decline is aggravated by the fact that in many farming systems, there is an increasing overreliance on a few food crops. In particular, the human population largely depends on maize, rice, and wheat to meet their dietary carbohydrate needs severely compromising micronutrition. Agrobiodiversity is, therefore, centerstage to any strategy aimed at developing sustainable food production systems that are resilient to stresses occasioned by climate change [6]. The burgeoning world human population has more than ever placed significant strain on agricultural production and agroecosystems. If sustainable approaches are not institutionalized, increased global food production might be met at the irredeemable cost of ecosystem stability.

Agrobiodiversity loss is worsened by the climate change that is consistently decimating the worlds cultivatable land size and crop productivity. Climate change has led to the continued rise in earth surface temperatures and unreliable rainfall patterns inducing abiotic stresses, considerably impacting the agrobiodiversity negatively [7,8]. Despite the glaring threat and risks posed by climate change to agroecosystems and perception, family farming systems’ responsiveness to this threat remains blurry. This pushes many farming systems of several nations to the dire echelons of food insecurity. In sub-Saharan Africa, food insecurity continues to be a significant impediment to the realization of UN sustainable development goals (SDGs), especially SDG 1: Eliminate Poverty, 2: Zero Hunger, and 3: Good Health and Well-Being. While there have been multifaceted approaches to boosting the agricultural production to increase food security using modern techniques, excessive chemical use and over-exploitation exacerbate the already dire loss of biodiversity in the agricultural ecosystems. Determination of the agrobiodiversity status and climate change mitigation in the vulnerable family farming systems is critical to food security intervention.

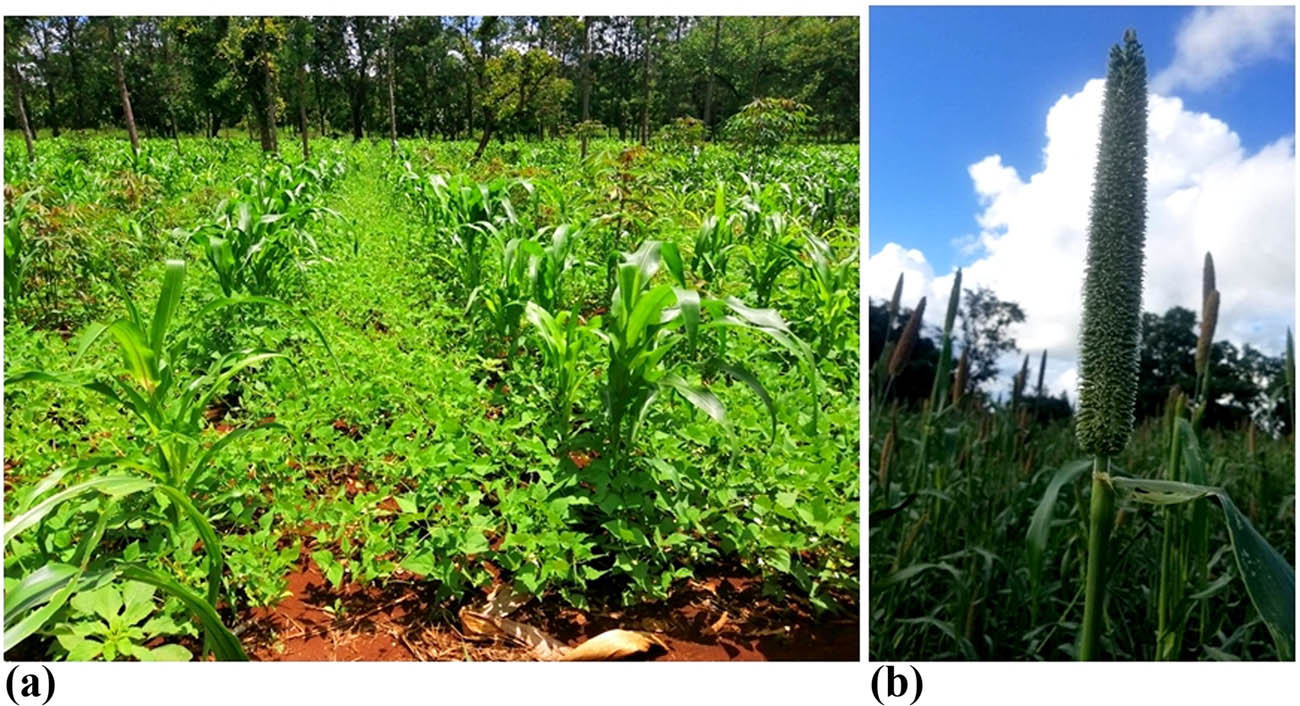

In the wake of climate change and biodiversity loss, family farming systems are the most vulnerable [9,10]. Family farming systems, also commonly referred to as smallholder farming systems, play an indispensable role in ensuring the rural agroecosystems’ genetic stability where they are dominant [10,11]. Though made of small individual units, collectively they supply more than half of the world’s food basket. The family farming systems are characterized by highly intensive land use, crop biodiversity, and mixed cropping systems (Figure 1). Family farming systems are the cornerstone of household development and economic empowerment in many cultures worldwide [12]. The Committee on World Food Security describes food security to occur among people when they have access to sufficient food all year round [13]. Considering the critical role they play, the promotion of agrobiodiversity in family farming systems is timely and there is a need to improve food production to meet the ever-burgeoning human world population with the least possible disturbance to the environment [14].

Family farming systems characterized by intercropping. Photograph (a) shows a farm in Kitui County with common bean and maize plants intercropped. Photograph (b) shows sorghum crop from Tharaka Nithi. Erratic rainfall occasioned by climate change has led to a rapid shift from maize to sorghum in many family farming systems in the arid agroecological zones of Kenya owing to its economic value and tolerance to water stress.

In family farming systems, agrobiodiversity is significantly affected by socio-economic and cultural factors. The socio-economic, cultural, biotic, and abiotic factors interact in an intricately complex manner to influence agrobiodiversity in myriad ways. The main objective of this study was to determine the agrobiodiversity status and climate change perception among the family farming systems in the semiarid belt of Eastern Kenya. The specific objectives were to determine: (1) the agrobiodiversity status among the family farming systems and relationship to food security in Tharaka Nithi, Embu, and Kitui Counties of Eastern Kenya, (2) the agrobiodiversity conservation measures in the three selected counties, (3) climate change perception and intervention strategies in the three counties of Eastern Kenya.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites

This study was conducted in three selected counties of Eastern Kenya; Tharaka Nithi, Kitui, and Embu Counties, all neighbors with their semiarid regions classified as food stressed. Unreliable rainfall patterns in recent past are associated with fluctuating productivity of the predominant family farming systems in the region. With most semiarid counties of Eastern Kenya predominantly practicing pastoral farming, the selected counties of Eastern Kenya have semiarid regions that practice agriculture as the principal economic activity with the regions of these counties receiving adequate rainfall being biodiverse hotspots. This makes them suitable candidate counties for agrobiodiversity studies in semiarid agroecosystems.

This study focused on the relatively semiarid lowland parts of the selected counties which receive as low as 600 mm annual rainfall. The select counties receive bimodal rainfall, short and long rains. It should, however, be noted that the periods do not reflect on the amount of rainfall but the duration. While agriculture is the principal economic activity supporting the livelihoods of 80% of the rural households in the selected counties, it is increasingly becoming an extremely burdensome venture owing to the challenges exacerbated by climate change. Cereals and legumes are the dominant crops grown in these regions with mango fruit farming also being common (Figure 2). Livestock rearing is also practiced; however, this is mostly limited by land sizes. The unreliable rainfall patterns, an apparent increase in temperatures, and rapidly deteriorating soil health over the recent decades have led to dwindling returns and biting food shortages in the region.

Mango fruit tree (Mangifera indica) in Kasafari, Embu County. Mango is the most popular fruit tree grown across the three counties. Mango is commonly grown in Eastern Kenya for commercial purposes.

2.2 Sampling and data collection

Ninety-two farmers were selected for this study; 32 farmers from Tharaka Nithi in Tunyai area, (0°10′33″ S, 37°50′12″ E), elevation of 600–1,500 m above sea level (asl), 30 farmers from Embu in Karurumo area (0°29′12″ S, 37°41′50″ E), 1,174 m a.s.l., and 30 farmers from Kitui, Matinyani area (1°18′30.6″ S 37°59′30.2″ E), 400–1,800 m a.s.l. Respondents’ selection was based on purposive sampling, with the focus centered on the active farmers who predominantly rely on agriculture for their livelihoods and have practiced farming in the region for a considerable period of time to give an account of the climate variability in the region.

Structured questionnaires were administered through direct face to face interviews with the family heads on the farms at times convenient for the respondents. Where the family head was unavailable, an adult member of the family above 18 years well versed with the farming history and economics and willing to participate in the survey was interviewed. Questionnaires primarily focused on the household characteristics, farm characteristics, crop diversity, food security status, and climate change intervention strategies. Based on the significance of maize and legumes in the rural family farming systems, there was also a greater focus on the determination of the diversity in legumes and maize varieties grown in the three study sites. The varieties of maize and cowpeas planted by the farmers were recorded using the local names by which they are known. The values of annual crop and livestock yields were also explored in the interviews. Other than the on-farm agrobiodiversity, the questionnaires were also tailored to determine the socio-economic characteristics of the households with a view to construct the socio-economic dimension of agrobiodiversity.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

2.3 Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. The quantitative and qualitative data were generated and described. The relationships between the demographic factors, agrobiodiversity status, and food security were determined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Species relative density was calculated for each crop using the formula below as outlined by Mburu et al. [11].

Crop Species Richness (CSR) and Livestock Species Richness (LSR) indices were calculated using the Shannon–Wiener index (H), Menhinick’s index measure of species richness (D), and Simpson’s Index of Dominance. Shannon–Wiener index and Simpson’s index of Dominance were suitable for this study as they take into account the aspects of species relative abundances, species evenness, and diversity which are critical in this study [14,15].

3 Results

3.1 On-farm agrobiodiversity

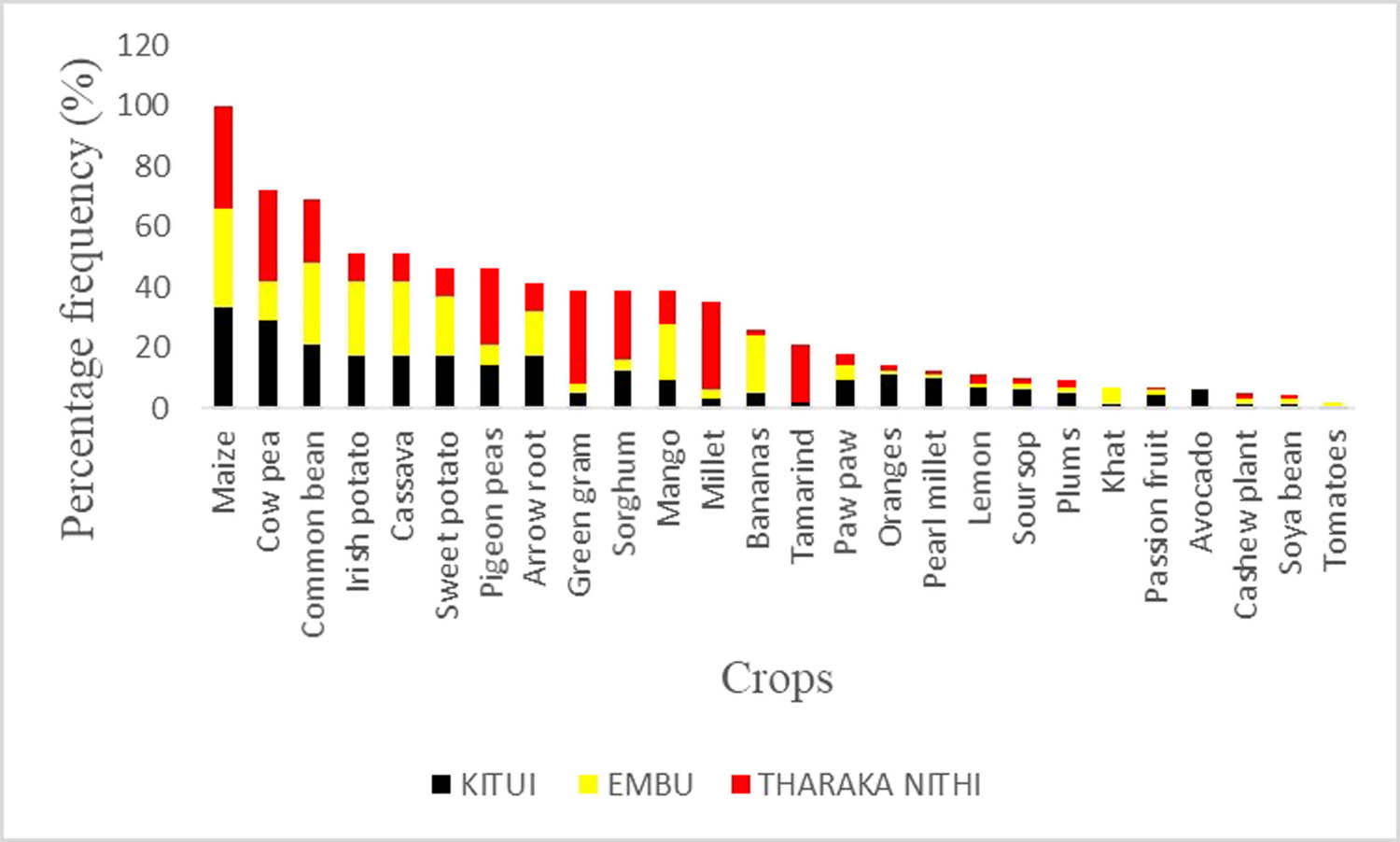

Twenty-six different species of crops were identified in the three counties. Only two categories of crops were grown by more than 50% of the farmers in the three counties; legumes and cereals (Figure 3). The most dominant cereal grown was maize. Other grains grown included millet, finger millet, sorghum, and pearl millet (Table 1). Legumes grown included common beans, cowpeas, pigeon peas, and green grams. There was a notable variation in the types of legumes and cereals grown in the three counties with millet scarcely grown by Embu and Kitui farmers but much preferred by the farmers in Tharaka Nithi County. The crops grown were mostly for food and commercial purposes. Mangoes and bananas were the main fruit trees planted across the three counties.

Different types of crops grown by farmers in the study area. Legumes and cereals were the dominant crop types. Bananas, mangoes, and tubers were the other crops grown by farmers in all the three counties. Tomatoes were only reported in Embu County, while avocado farming was reported only in Kitui County.

Relative densities of the crop species grown in the study area

| Crop species | Scientific name | Relative density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maize | Zea mays | 11.9 |

| Cowpea | Vigna sinensis L. | 9.3 |

| Common bean | Phaseolus vulgaris | 8.9 |

| Irish potato | Solanum tuberosum | 6.6 |

| Cassava | Manihot esculenta | 6.6 |

| Sweet potato | Ipomoea batatas | 5.9 |

| Pigeon peas | Cajanus cajan | 6.0 |

| Arrow root | Maranta arundinacea L. | 5.3 |

| Green gram | Vigna radiata | 5.1 |

| Sorghum | Sorghum bicolor | 5.1 |

| Mango | Mangifera indica | 5.1 |

| Millet | Eleusine coracona | 4.5 |

| Bananas | Musa acuminata | 3.4 |

| Tamarind | Tamarindus indica | 2.7 |

| Paw paw | Carica papaya | 2.3 |

| Oranges | Citrus sinensis | 1.8 |

| Pearl millet | Pennisetum glaucum | 1.6 |

| Lemon | Citrus limon | 1.4 |

| Soursop | Annona muricata | 1.3 |

| Plums | Prunus domestica | 1.2 |

| Khat | Catha edulis vahl | 0.9 |

| Passion fruit | Passiflora edulis | 0.9 |

| Avocado | Persea americana | 0.8 |

| Cashew fruit | Anacardium occidentale | 0.6 |

| Soya bean | Glycine max | 0.5 |

| Tomatoes | Solanum lycopersicum L. | 0.3 |

Farms under maize cultivation in Embu and Kitui were slightly larger than Tharaka Nithi. The total cultivatable area influenced the area under maize cultivation in most of the households surveyed (p < 0.05, r = 0.411). There was no significant variation between the age group of the household and the total area under cultivation. The total available land per farm varied in the study area. Most farms in Embu and Kitui Counties were smaller, averaging between 1 and 2 acres, while those in Tharaka Nithi County had >5 acres of land.

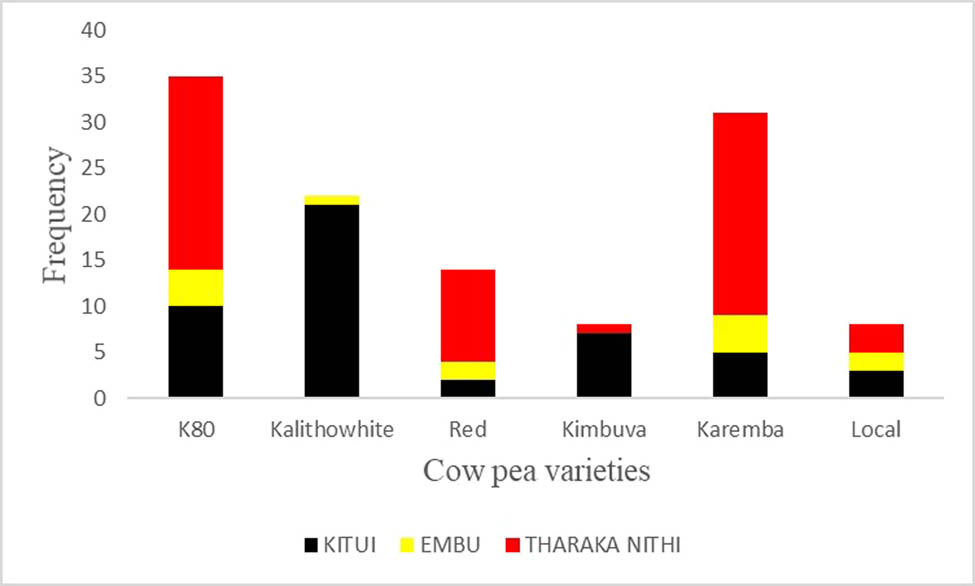

There was remarked diversity in the variety of cowpea and maize crops. Eight varieties of cowpea were grown; K80, Kalitho white, Red, Kimbuva, Karemba, Local, Muthonga, and Yellow. Karemba and K80 were the dominant varieties in Tharaka with frequencies (F) of 21 and 22, respectively. Dominant varieties in Embu were K80 (F = 4) and Karemba (F = 4). In Kitui, the dominant cowpea varieties grown were K80 and Kalitho white with F values of 10 and 21, respectively (Figure 4). It should, however, be noted that in Tharaka Nithi County, cowpea farming is done on a very small scale with the primary purpose being for vegetable use. This is in sharp contrast to Embu County, where cowpea is a significant cash crop. A total of 11 maize varieties were identified in the study area; DUMA 43, Katumani, Kikamba, Kitharaka, DH02, Makueni, DH04, Sungura, Sawa, DK 8031, and Hybrid 531. DUMA 43 was the most popular variety across the three counties.

The dominant cowpea varieties grown in the three counties. K80, Red, Karemba, and Local varieties were commonly grown in all three counties, albeit with varying degrees of frequency. Majority of the farmers in Tharaka grew K80, Karemba, and Red varieties.

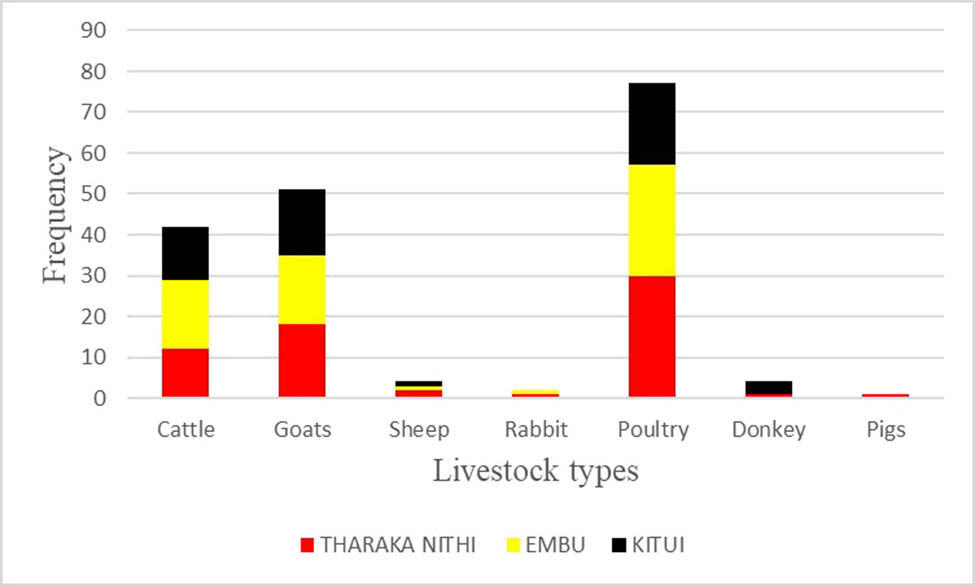

There was also significant diversity in livestock kept by the farmers. A total of 12 species of livestock were identified; cattle, goats, sheep, rabbits, chicken, ducks, turkey birds, guinea fowls, cats, dogs, pigs, and donkeys. For livestock species, the highest Menhinick’s species richness index was observed in Tharaka Nithi County (0.262) with the least index witnessed in Embu County (0.202). According to Simpson’s Diversity index, Kitui County had the highest livestock diversity index of 2.049, with Embu County showing the least livestock diversity of 1.365 (Table 2). The current study established a significant negative correlation between the age of the farmer and livestock rearing. There was also a significant positive correlation between livestock keeping and reserve food (p < 0.05, r = 0.416).

Diversity indices of the common cereals and legumes varieties grown in the study area

| Diversity indices | Embu | Tharaka Nithi | Kitui | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legumes | Cereals | Legumes | Cereals | Legumes | Cereals | |

| Taxa_S | 30 | 30 | 32 | 32 | 30 | 30 |

| Individuals | 54 | 35 | 109 | 88 | 89 | 40 |

| Dominance_D | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.039 |

| Simpson_1-D | 0.960 | 0.962 | 0.967 | 0.968 | 0.963 | 0.961 |

| Shannon_H | 3.305 | 3.342 | 3.436 | 3.449 | 3.35 | 3.329 |

| Evenness_e^H/S | 0.908 | 0.943 | 0.971 | 0.983 | 0.951 | 0.931 |

| Brillouin | 2.682 | 2.522 | 3.014 | 2.958 | 2.891 | 2.575 |

| Menhinick | 4.082 | 5.071 | 3.065 | 3.411 | 3.18 | 4.743 |

| Margalef | 7.27 | 8.157 | 6.608 | 6.924 | 6.461 | 7.861 |

| Equitability_J | 0.972 | 0.983 | 0.991 | 0.995 | 0.985 | 0.979 |

| Fisher_alpha | 27.79 | 99.74 | 15.26 | 18.09 | 15.9 | 54.53 |

| Berger-Parker | 0.056 | 0.086 | 0.046 | 0.045 | 0.056 | 0.075 |

| Chao-1 | 37.09 | 111.3 | 32 | 32 | 30 | 53.33 |

Cattle, goats, and poultry were the main livestock reared in the study area. No significant diversity was observed among the poultry species in the three counties, with most family farming systems engaging in chicken rearing (Figure 5). The livestock rearing technique was determined to be influenced significantly with the total farm land with tethering more preferred in the smaller family farming units. A negative correlation was observed between free range technique and the total farm area (p < 0.01 r = −0.450).

Livestock species reared in the selected counties of Eastern Kenya. Cattle, goats, and poultry were the dominant livestock species across the three counties. The animals were predominantly kept for sustainable insurance in addition to crop farming. Proceeds from livestock sales were majorly used to pay for education and other daily household needs.

3.2 Socio-economic factors

All the households that took part in this survey practice agriculture as the main economic activity. Most of the households in Embu and Kitui Counties are headed by males. In sharp contrast, however, only 21.9% of the surveyed households in Tharaka Nithi County are headed by males. Eighty percent of the household heads had at least basic primary education. A higher percentage of household heads with no education was reported in Tharaka Nithi County. The data collected showed that all the households depended wholesomely on agriculture for their livelihood. The average household occupancy in Tharaka Nithi and Embu Counties were 3.9 and 3.8, respectively (Table 3). There was no significant relationship between the household head age and the total area put under cultivation.

Socio-economic factors affecting biodiversity across the selected counties

| Characteristic | Tharaka Nithi (N = 32) | Embu (N = 30) | Kitui (N = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family farming unit male (%) | 21.9 | 60.0 | 60.0 |

| Marital profile of the FH (% married) | 68.8 | 83.3 | 80.0 |

| Education level of FH | |||

| No education (%) | 15.6 | 3.3 | 10.0 |

| Primary education (%) | 37.5 | 40.0 | 46.7 |

| Secondary education (%) | 43.6 | 50.0 | 26.7 |

| University education (%) | 3.1 | 6.7 | 10.0 |

| Other (%) | — | — | 6.7 |

| Households in business (%) | 9.4 | 13.3 | 3.3 |

| Households employed (%) | 3.1 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Households in crop farming (%) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Total household occupancy (x) | 3.9 | 3.8 | 5.1 |

3.3 Soil conservation status and climate change perception

3.3.1 Soil conservation status and management practices

Soil erosion challenges were reportedly most pronounced in Tharaka Nithi County, with the farms of 75% of the respondents severely affected. Only 40% of household farms in Embu County reported having soil erosion challenges. Major notable soil conservation measures included bench terraces to curb soil erosion, crop rotation, use of compost manure, and mixed cropping. The family subsistence farms surveyed in Kitui, however, did not practice mixed farming. Most of the respondents interviewed across the three counties reported their farm soils to be less fertile. Only 10% of the farmers in Kitui reported having fertile soils. The percentage of farms perceived fertile by farmers in Embu and Tharaka Nithi Counties were 0.0 and 6.3%, respectively (Table 4). All the farmers interviewed from Embu perceived their farms to be less fertile and could not produce significant yield without intensive application of farm yard manure or inorganic fertilizers. There was greater use of herbicides in weed control in Tharaka Nithi (78.1%) compared to the other counties.

Soil conservation status and climate change perception

| Characteristic | Embu County | Kitui County | Tharaka Nithi County |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil conservation factors | |||

| Soil erosion problems (%) | 40.0 | 60.0 | 75.0 |

| Soil conservation structures present (%) | 26.7 | 60.0 | 71.9 |

| Crop rotation done (%) | 66.7 | 26.7 | 65.6 |

| Mixed cropping (%) | 30.0 | — | 62.5 |

| Compost manure users (%) | 53.3 | 36.7 | 21.9 |

| Inorganic fertilizer users (%) | 66.7 | 13.3 | 59.4 |

| Conservation tillage (%) | 10.0 | 6.7 | 28.1 |

| Shift cultivation (%) | 13.3 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

| Herbicides in weed control (%) | 36.7 | 10.0 | 78.1 |

| Farms perceived fertile (%) | 0.0 | 10.0 | 6.3 |

| Causes of climate change | |||

| Use of farm chemicals (%) | 46.7 | 13.3 | 43.8 |

| Deforestation (%) | 66.7 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Industrialization (%) | 6.7 | 13.3 | 21.9 |

| Effects of climate change | |||

| Land degradation (%) | 40.0 | 23.3 | 40.6 |

| Reduced yield (%) | 66.7 | 50.0 | 78.1 |

| Erratic rain (%) | 60.0 | 36.7 | 68.8 |

| Drought (%) | 70.0 | 56.7 | 65.6 |

| Floods (%) | 13.3 | 23.3 | 9.4 |

| Human wildlife conflict (%) | 30.0 | 6.3 | 43.8 |

| Intervention strategies | |||

| Drought tolerant crops (%) | 26.7 | 60.0 | 46.9 |

| Cover crops (%) | 26.7 | 36.7 | 28.1 |

| Short term crops (%) | 36.7 | 26.7 | 53.1 |

| Agroforestry (%) | 50.0 | 56.7 | 50.0 |

3.3.2 Perceived climate change and intervention measures

Generally, the respondents acknowledged significant climate change. There were varied opinions on the perceived causes and effects of climate change. Most notably, respondents cited excessive usage of agrochemicals and deforestation as the leading causes of climate change, with fewer respondents quoting industrialization. Significant reduction in crop yields, erratic rainfall, and drought were perceived to be the main effects of climate change. Despite the higher perception of climate change, responsive strategies are relatively weak among smallholder farmers (Table 4). Only 26.7% of farm households in Embu have adopted the use of drought tolerant crops (Table 4).

Though most farmers could not adequately explain the causative factors of climate change, it was generally noted that the family farming systems acknowledged the real dangers presented by climate change. A slightly higher proportion of Kitui farmers had more significant intervention measures to cope with climate change compared to the two counties (Table 4), with 60% of the respondents using drought-tolerant crops. Respondents noted the increased human-wildlife conflict as a significant effect of climate change (43.8%) with monkeys reported as key pests in Tharaka Nithi County.

3.4 Food security

The current study established that food shortage is a commonly recurring problem in the family farming systems. The percentage of family farming systems affected by food shortage in Embu, Kitui, and Tharaka Nithi Counties are 90, 56.7, and 78.1%, respectively. While food shortage was reported to affect a significant proportion of farmers in Embu County, 46.7% of the affected family farming systems in Embu relied on reserve food supplies during the shortage period. This is in contrast to Kitui and Tharaka Nithi Counties, where only 20 and 28.1%, respectively, of the affected families relied on reserve food.

4 Discussion

4.1 On-farm agrobiodiversity

Remarkably, 26 different crop species were recorded in the study area indicating a high agrobiodiversity in the study area. Maize and legumes were the most dominant crops grown by all farmers in the region. Numerous studies on agrobiodiversity in family farming systems across the globe have documented high agrobiodiversity with dominance of one or two crops. The crop dominance is guided by dietary habits, socio-cultural factors, and local market dynamics. Influence of dietary behaviors on choice of crops sowed by the family farming systems has been established by many studies [11,14,16,17,18] with maize and rice being the most dominant crops in Africa and Asia. Crops were majorly grown for food with the surplus occasionally sold in the local markets. Maize is the main crop used to make ugali, the main staple food in the region. Alternatively, it is often combined with beans to make githeri, another popular local meal. This underpins the significance of the two dominant crops in the study area. With generally low incomes in the rural establishments, protein rich-legumes are predominant source of protein in the diets as most households cannot afford animal-based proteins such as meat and fish. An agrobiodiversity study survey by Mburu et al. [11] on the upper parts of Embu established much higher agrobiodiversity with 39 crop species reported. The difference in crop species diversity in different smallholder agroecosystems is explained by difference in physical factors with the amount of precipitation being critical [19].

Considerably lower maize cultivation was noted in Tharaka Nithi County compared to the other two counties. Most respondents from Tharaka Nithi County revealed that the size of farms under maize cultivation has decimated over the recent years with climate change being the driving force behind the change. Decreased rainfall totals in the region have favored millet and sorghum cultivation in Tharaka Nithi with maize not doing well with the low annual precipitation. Temperature and topographical factors have also been documented to have profound effect on diversity as well [19].

There was significant diversity in the variety of maize seeds grown in the study area. Productivity and resistance to drought were the main considerations for the selection of the variety of maize to be grown by most farmers. Few respondents also hinted to quick maturing varieties as the leading factor of consideration. This was in part due to the unreliable rainfall patterns. Some farmers, however, had no specific reason for choice of varieties of crops to grow with their choices guided by friends and neighbors. The same factors have been established to drive family system farmers’ choices in other similar studies [4,20,21]. DUMA 43 was the most popularly grown maize variety in the study area. While most respondents could easily acquire the certified seeds from the local agro-based veterinary shops, some respondents expressed fear of unscrupulous dealers selling uncertified fake seeds. Most farmers in Kitui expressed faith in the local maize varieties citing higher resistance to drought.

Mangoes and bananas were the most common fruits grown in the three regions with respondents citing high marketability of the two fruits. Studies reveal that in most family farming systems, farmers have learned over time to select crops that are most suited for the local physicochemical conditions and can offer the best ecological services [17,20,21,22].

Legumes, other than being a food source, are also well known for their ecological and economic significance in the smallholder family farming systems found in areas of low to moderate annual rainfall. Cowpea farming was more dominant in Embu and Kitui Counties. Most farmers in Tharaka Nithi County planted cowpea, not for grains, but for use as vegetables. With vegetables being the primary purpose for most cowpea farmers, most grew the local varieties in Tharaka Nithi. Karemba and K80 varieties were preferred in Embu and Kitui Counties for their productivity and marketability. Legumes hold a significant value to the farmers due to not only their nutritional significance but also their economic contribution to the provisions of the household livelihoods. They are high-value crops that fetch the farmers significant income essential for their livelihood providence. Green grams were only grown by a few farmers from Kitui and Tharaka Nithi Counties. Most respondents reported abandoning green gram farming due to high pest invasion severely decimating production. This underpins the critical role pests have on agrobiodiversity. Decreased landholding capacity of family household farms occasioned by an increasing rural population also leads to loss of biodiversity [18,19]. Integrated livestock keeping was a common observation among the family farming systems in the study area. Most respondents kept livestock for food, labor, security, and cash. With agricultural produce not reliable, most farmers sold their livestock during prolonged droughts to enable them to purchase food and also meet their obligations such as healthcare and education. Several studies have identified that livestock rearing is an integral activity in smallholder family units for ecosystem services and the providence of livelihoods [16,23]. Land size is a significant impediment to effective and sustainable livestock keeping in the area. A possible reason for the high species richness index in Tharaka Nithi County could be the comparatively larger farm sizes in Tharaka Nithi in comparison to Embu and Kitui Counties. The negative correlation between the age of the farmers and livestock rearing observed in this study can be attributed to the rigorous demands of livestock rearing, making most of the aging farmers to prefer majoring in crop farming. Livestock rearing provides the family farming systems with the much-needed insurance against the agronomic risks such as droughts and pests and diseases that have been exacerbated by climate change. Most subsistence farmers in the study area rely on income from legumes and cereals to meet other vital needs such as clothing, medicare, and education. Where livestock rearing takes place, the income from livestock ensures that the farmers sell less of their food crops, leading to improved food security.

4.2 Socio-economic factors

Socio-cultural factors form an integral component of agrobiodiversity influencing several critical farming decisions and land management practices. Household occupancy in Embu and Tharaka Nithi Counties reflected the national average rural household occupancy (four persons) with Kitui County having a slightly higher household occupancy (5 persons). Household occupancy is a critical factor in the agronomic practices of the family system farms. While it is a critical indicator of the labor force available for farm activities, it also places significant stress on food resources that can compromise food security, especially if most of the household occupants are young and of school-going age. Eighty percent of family subsistence farms depend on their family labor [18]. A higher proportion of households is composed of school-going children increasing dependency which consequently places huge stress on family agricultural income. A higher agrobiodiversity is observed among the households headed by older farmers. The reason for this could be the long-standing history and understanding of the crop species best suited to the variable local climatic patterns. This is consistent with the findings of Whitney on agrobiodiversity in Uganda [24].

Most respondents had no formal employment with even fewer engaging in alternative businesses. These statistics point to a community of farmers heavily reliant on agriculture and with limited access to financial capital that can enhance improvement in farming management and practices. The measure of family household wealth significantly influences the agrobiodiversity since they can easily try out new crops and can manage the resulting agronomic risks [19]. Kitui County had the highest percentage of older farmers. The age of the household head has been established in other studies to influence not only the biodiversity but also food security in other studies [25].

4.3 Soil fertility status and conservation measures

Soil erosion was a notable problem across the three counties with varying degrees, Tharaka Nithi being the most affected. This is explained by the topographical differences across the study area. While farms in Tharaka Nithi County are on steep slopes, the surveyed farms in Embu County are on gentle slopes hence lesser risks of soil erosion. Continuous land use in sloping lands has been identified as a causative factor of soil erosion in many family farming systems [19]. Continued soil degradation is steadily decimating world global crop production, with SSA being the most affected [22]. Most farms were perceived to be less fertile. Continuous land use and poor soil conservation measures could be the leading factors for continued soil degradation.

While most farmers preferred the use of farmyard manure, there was inadequate access, with most farmers unable to meet the cost of farmyard manure. Not many farmers in the region keep livestock numbers sufficient to produce manure that can sustainably support organic soil fertility mitigation. Other studies also indicate that for the farmers who buy farmyard manure, poor infrastructure across many rural settlements escalates the farmyard manure prices high beyond the reach of many resource-strained small-holder farmers [26,27]. Perhaps oblivious to the potential risk of further environmental degradation or sheer disregard promoted by lack of proper conservation guard policies, rapid deforestation, and charcoal burning practices, these activities are still a common occurrence in the study area (Figure 6).

Charcoal burning in Tharaka Nithi County. While tree felling is outlawed in many counties, inadequate oversight and enforcement still allow such land degrading practices to continue.

Mixed cropping, bench terraces, and crop rotation were the main intervention measures. Lack of proper education and exposition to soil conservation measures in family farming systems hinder the soil conservation efforts [28]. With soil fertility rapidly declining, most of the family farming systems have resorted to the use of inorganic fertilizers as a quick-fix solution. However, inorganic fertilizers alter the physicochemical properties of the soil through their direct and indirect effect on native soil microflora, making soils more susceptible to soil erosion. This is consistent with other studies that have also established a strong correlation between inorganic fertilizer use and soil degradation [10,19]. It is also noteworthy that farm characteristics also have a significant bearing on soil conservation efforts. There is a strong positive correlation between the size of land and crop rotation. With most family farming systems being greatly decimated in size due to increased land fragmentation, most farms are too small to permit sustainable rotatory farming systems.

4.4 Perceived climate change and intervention measures

While it was evident from many respondents that there has been notable climate change, not many individuals could astutely explain the phenomenon and its causes. More than half of the respondents perceived deforestation as the leading cause of climate change. Some respondents could neither describe climate change nor identify the causative factors. This can be attributed to the complex nature of the climate, limited knowledge on the same, and limited access to information [5]. This study also established that most farming households identified climate change as a significant threat to food security and livelihoods. This agrees with the study that was conducted by Waldman among smallholder farmers, which established that 98% of the farmers identified climate change as a significant threat to their livelihoods [29]. The percentage of farmers adopting short term crops was proportionately higher in Tharaka Nithi County than the other counties. This is explainable by the drier climate of Tharaka Nithi in comparison to the other counties.

With climate change leading to alteration of farming activities, many farmers in the region are increasingly resorting to the use of modern short-term seeds and abandoning the local varieties. This will place even greater stress on agrobiodiversity [24]. A good number of the older farmers also preferred the local maize varieties to the newer modern varieties due to their better adaptability to climate change. This calls for heightened studies on climate change perceptions among the subsistence farmers and the factors hindering climate change adaptations. The adoption of climate change intervention techniques will be critical in ensuring genetic stability and food security in family farming systems (Table 5).

Effective climate change adaptive strategies for smallholder farms

| Climate change adaptation strategies | Reference |

|---|---|

| Increased livestock integration | Amejo et al. [23]; Morton, [30] |

| Diversification of farmers’ livelihoods | Descheemaeker et al. [16]; Mortimore and Adams [7]; Morton, [30] |

| Drought resistant, short time maturing crops, and changing planting dates | Harvey et al. [31]; Khanal et al. [32]; Komba and Muchapondwa [33]; Menike and Arachchi [34]; Wekesa et al. [35] |

| Sturdy local livestock breeds over highly productive cross breeds. | Kichamu et al. [36] |

| Grazing management | Descheemaeker et al. [16] |

| Managing agrobiodiversity | Mortimore and Adams [7] |

| Agroforestry | Harvey et al. [31]; Komba and Muchapondwa [33] |

4.5 Food security

The family farming systems in the study area were established to be highly food insecure owing to the recurrent food shortage. Most farmers cited low yields occasioned by unreliably low rainfall as the main factor contributing to food shortage. Farmers in the study area rely exclusively on rain-fed agriculture. When rainfall is sufficient, most farmers realized harvests that comfortably saw them through the drought periods. Farm sizes also influence crop productivity and food shortage. With poor farming practices, small farms often translate to low yields that cannot comfortably sustain the families through the subsequent growing seasons [8,11]. Most farmers also cited their overreliance on agriculture as the main economic activity; hence significant variations in seasonal productivity impacted massively on their food security. They often rely on agriculture not just for food but also for other necessities like shelter, clothing, medication, and education. Selling off parts of their agricultural proceeds to meet these critical needs exposes them to the risk of food shortage and insecurity. Maize is the chief staple food consumed by residents of Eastern Kenya and, therefore, the size of land under maize cultivation has a strong bearing on the food security of a household in this region.

Another study also reported that the mismatch between the high cost of farm inputs such as seeds and inorganic fertilizers and farm output prices makes it an upward task for family farming systems to navigate out of the food insecurity pool [13]. Family farming systems with higher crop diversification reported less food shortage than family farming systems with one or two dominant crops planted underscoring the significance of agrobiodiversity to food security. There was correlation between livestock keeping and reserve food and hence improved food security. With no respondents practicing livestock keeping solely, family farming systems keeping livestock had higher agrobiodiversity. The sale of livestock reduces the need of farmers to sell off their crop produce to meet their livelihood demands improving food security among the households. Crop diversification boosts food security as some of the resilient crops can withstand unreliable rainfall patterns where the dominant cereals and legumes fail. Monoculture farming techniques can be severely affected by droughts and pests significantly predisposing the families to food insecurity. Several studies have established climate change and soil-borne pathogens as critical threats to agrobiodiversity and food security among family system farmers [8,12,13,16,24,37]. Occurrence and abundance of pathogens are exacerbated by certain farming conditions and practices in family farming systems. Observed field aggregation, abundance, and uniformity of the host crop species in most of the farms in Eastern Counties of Kenya contribute significantly to fueling the spread of the pathogens leading to significant losses, thus, affecting food security.

5 Conclusion

The rapid decrease in the diversity of crops in global agriculture production accelerated by modern agriculture is a threat to global health and food security. This study focused on the determination of agrobiodiversity status and climate change perceptions in the selected counties of Eastern Kenya. High agrobiodiversity was recorded in the region with climate change influencing crop practices. Despite its glaring effects, climate change perception was largely obscure in the study region, significantly impeding institutionalization of intervention measures. There is an urgent need for future studies to be aimed at formulating biodiversity driven sustainable agriculture policies among the subsistence farmers. With no reported use of biopesticides and biofertilizers, the need for sensitization programs on alternative green solutions to the biotic and abiotic stressors of crop productivity is critical.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Reverend Anthony Njeru Jesse for his precious help in organizing the farmer interviews. Moreover, we acknowledge the smallholder farmers from Tharaka Nithi, Embu, and Kitui for their participation and cooperation in this study.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by The Future Leaders – African Independent Researchers (FLAIR) Fellowship Programme, which is a partnership between the African Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society funded by the UK Government’s Global Challenges Research Fund (Grant number FLR\R1\190944).

-

Author contributions: E.M.N.: conceived and designed the study procedures, R.O.A., K.C.K., K.K., A.A.J., and M.M.: carried out the interviews and data collection, and R.O.A., M.M., and E.M.N. conducted data analysis. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Almond RE, Grooten M, Peterson T. Living planet report 2020 – bending the curve of biodiversity loss. Gland, Switzerland: World Wildlife Fund; 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] FAO and OECD. Food security and nutrition: challenges for agriculture and the hidden potential of soil; 2020. www.fao.org/publications.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Gabel V, Home R, Stöckli S, Meier M, Stolze M, Köpke U. Evaluating on-farm biodiversity: a comparison of assessment methods. Sustainability. 2018 Dec;10(12):4812. 10.3390/su10124812.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Jones AD. On-farm crop species richness is associated with household diet diversity and quality in subsistence-and market-oriented farming households in Malawi. J Nutr. 2017 Jan 1;147(1):86–96. 10.3945/jn.116.235879.substituting.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Altieri MA, Koohafkan P. Enduring farms: climate change, smallholders and traditional farming communities. Penang: Third World Network (TWN); 2008 Nov.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Brookfield H, Stocking M. Agrodiversity: definition, description and design. Glob Environ Change. 1999 Jul 1;9(2):77–80. 10.1016/S0959-3780(99)00004-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Mortimore MJ, Adams WM. Farmer adaptation, change and ‘crisis’ in the Sahel. Glob Environ Change. 2001 Apr 1;11(1):49–57. 10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00044-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Reynolds TW, Waddington SR, Anderson CL, Chew A, True Z, Cullen A. Environmental impacts and constraints associated with the production of major food crops in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Food Secur. 2015 Aug;7(4):795–822. 10.1007/s12571-015-0478-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Andersson Djurfeldt A, Cuthbert Isinika A, Mawunyo Dzanku F. Agriculture, diversification, and gender in rural Africa: longitudinal perspectives from six countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018.10.1093/oso/9780198799283.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Sibhatu KT, Qaim M. Rural food security, subsistence agriculture, and seasonality. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 19;12(10):e0186406. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186406.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Mburu SW, Koskey G, Kimiti JM, Ombori O, Maingi JM, Njeru EM. Agrobiodiversity conservation enhances food security in subsistence-based farming systems of Eastern Kenya. Agric Food Secur. 2016 Dec;5(1):1. 10.1186/s40066-016-0068-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Scialabba NE, Pacini C, Moller S. Smallholder ecologies. 2014, Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4196e.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Dioula BM, Deret H, Morel J, Vachat E, Kiaya V. Enhancing the role of smallholder farmers in achieving sustainable food and nutrition security. ICN2, Second International Conference on Nutrition. Vol. 13. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2013. 10.1016/j.emc.2013.01.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Oduor FO, Boedecker J, Kennedy G, Termote C. Exploring agrobiodiversity for nutrition: Household on-farm agrobiodiversity is associated with improved quality of diet of young children in Vihiga, Kenya. PLoS One. 2019 Aug 2;14(8):e0219680. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219680.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Baul TK, Rahman MM, Moniruzzaman M, Nandi R. Status, utilization, and conservation of agrobiodiversity in farms: a case study in the northwestern region of Bangladesh. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2015 Oct 2;11(4):318–29. 10.1080/21513732.2015.1050456.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Descheemaeker K, Oosting SJ, Homann-Kee Tui S, Masikati P, Falconnier GN, Giller KE. Climate change adaptation and mitigation in smallholder crop–livestock systems in sub-Saharan Africa: a call for integrated impact assessments. Region Environ Change. 2016 Dec;16(8):2331–43. 10.1007/s10113-016-0957-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Nkwiine C, Tumuhairwe JK. Effect of market-oriented agriculture on selected agrobiodiversity, household income and food security components. Uganda J Agric Sci. 2004;9(1):680–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Bisht IS, Pandravada SR, Rana JC, Malik SK, Singh A, Singh PB, et al. Subsistence farming, agrobiodiversity, and sustainable agriculture: a case study. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2014 Sep 14;38(8):890–912. 10.1080/21683565.2014.901273.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] McCord PF, Cox M, Schmitt-Harsh M, Evans T. Crop diversification as a smallholder livelihood strategy within semi-arid agricultural systems near Mount Kenya. Land Use Policy. 2015 Jan 1;42:738–50. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.10.012.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Altieri MA, Funes-Monzote FR, Petersen P. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: contributions to food sovereignty. Agron Sustain Dev. 2012 Jan;32(1):1–3. 10.1007/s13593-011-0065-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Frei M, Becker K. Agro-biodiversity in subsistence-oriented farming systems in a Philippine upland region: nutritional considerations. Biodivers Conserv. 2004 Jul;13(8):1591–610. 10.1023/B:BIOC.0000021330.81998.bb.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Riesgo L, Louhichi K, GomezPaloma, Hazell S, Ricker-Gilbert P, Wiggins J, et al. Food and nutrition security and role of smallholder farms: challenges and opportunities. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies; Information for Meeting Africa’s Agricultural Transformation and Food Security Goals (IMAAFS). Luxembourg: European Commission Publications Office; 2016. 10.2791/653314.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Amejo AG, Gebere YM, Kassa H, Tana T. Characterization of smallholder mixed crop–livestock systems in integration with spatial information: in case Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):1565299. 10.1080/23311932.2019.1565299.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Whitney CW. Agrobiodiversity and nutrition in traditional cropping systems-Homegardens of the indigenous Bakiga and Banyakole in southwestern Uganda. Doctoral dissertation. Witzenhausen: University of Kassel; 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Achonga BO, Akuja TE, Kimatu JN, Lagat JK. Implications of crop and livestock enterprise diversity on household food security and farm incomes in the Sub Saharan Region. Glob Inst Res Educ. 2015;4(2):125–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Kanton RA, Prasad PV, Mohammed AM, Bidzakin JK, Ansoba EY, Asungre PA, et al. Organic and inorganic fertilizer effects on the growth and yield of maize in a dry agro-ecology in northern Ghana. J Crop Improv. 2016 Jan 2;30(1):1–6. 10.1080/15427528.2015.1085939.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Raimi A, Adeleke R, Roopnarain A. Soil fertility challenges and biofertiliser as a viable alternative for increasing smallholder farmer crop productivity in sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Food Agric. 2017 Jan 1;3(1):1400933. 10.1080/23311932.2017.1400933.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Muoni T, Barnes AP, Öborn I, Watson CA, Bergkvist G, Shiluli M, et al. Farmer perceptions of legumes and their functions in smallholder farming systems in east Africa. Int J Agric Sustain. 2019;17(3):205–18. 10.1080/14735903.2019.1609166.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Waldman KB, Attari SZ, Gower DB, Giroux SA, Caylor KK, Evans TP. The salience of climate change in farmer decision-making within smallholder semi-arid agroecosystems. Climat Change. 2019 Oct;156(4):527–43. 10.1007/s10584-019-02498-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Morton JF. The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007 Dec;104(50):19680–5. 10.1073/pnas.0701855104.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Harvey CA, Saborio-Rodríguez M, Martinez-Rodríguez MR, Viguera B, Chain-Guadarrama A, Vignola R, Alpizar F. Climate change impacts and adaptation among smallholder farmers in Central America. Agric Food Secur. 2018 Aug;7(1):1–20. 10.1186/s40066-018-0209-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Khanal U, Wilson C, Lee B, Hoang VN. Smallholder farmers participation in climate change adaptation programmes: understanding preferences in Nepal. Clim Policy. 2018 Dec;18(7):916–27. 10.1080/14693062.2017.1389688.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Komba C, Muchapondwa E. Adaptation to climate change by smallholder farmers in Tanzania. Agricultural adaptation to climate change in Africa: Food Security in a Changing Environment. 2018 March;129–168. 10.4324/9781315149776.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Menike LMCS, Arachchi KAGPK. Adaptation to climate change by smallholder farmers in rural communities: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Procedia Food Sci. 2016;6:288–92. 10.1016/j.profoo.2016.02.057.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Wekesa C, Ongugo P, Ndalilo L, Amur A, Mwalewa S, Swiderska K. Smallholder farming systems in coastal Kenya Key trends and innovations for resilience. London: IIED; 2017. https://pubs.iied.org/17611iied.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Kichamu EA, Ziro JS, Palaniappan G, Ross H. Climate change perceptions and adaptations of smallholder farmers in Eastern Kenya. Environ Dev Sustain. 2017 July;20(6):2663–80. 10.1007/s10668-017-0010-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Wolde-Meskel E, van Heerwaarden J, Abdulkadir B, Kassa S, Aliyi I, Degefu T, et al. Additive yield response of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) to rhizobium inoculation and phosphorus fertilizer across smallholder farms in Ethiopia. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2018 Jul 1;261:144–52. 10.1016/j.agee.2018.01.035.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 Ezekiel Mugendi Njeru et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?