Abstract

This study investigates how Korean speakers interpret a covert element in an ambiguous double-nominative psych-predicate construction (e.g., Cengmi-ka kekcengsulewun ka pota, ‘Cengmi must be worried/worrisome’). Prior research suggests that the thematic role (experiencer vs. stimulus) assigned to the sole overt NP Cengmi depends on whether the discourse topic shifts or continues, implicating discourse factors in null pronoun interpretation. We conducted a 2 × 2 self-paced reading experiment that manipulated topic status (shift vs. continuation) and thematic role (experiencer vs. stimulus) to probe whether the repeated name penalty (RNP) in the centering theory framework can explain these interpretations, as was argued in previous studies. Results indicate that the immediate penalty predicted by the RNP did not appear; effects emerged only after the psych-predicate, suggesting that simple NP-repetition effects cannot fully account for how participants resolved the ambiguity. Moreover, clear signs of the experiencer reading bias and context-dependent revision were observed. We discuss the implications of the findings and highlight the need for further research to clarify how comprehenders integrate and project discourse structure.

1 Introduction

The production and the interpretation of pronouns have been extensively studied with regard to various aspects such as discourse coherence (Gordon et al. 1993; Grosz et al. 1995; Hwang 2023; Kehler 2002; Kehler et al. 2008), inter-sentential causality and consequentiality (Crinean and Garnham 2006; Garnham et al. 2021; Garvey and Caramazza 1974; McKoon et al. 1993; Pickering and Majid 2007; Stewart et al. 1998), and grammatical positions (Chambers and Smyth 1998; Crawley et al. 1990; Smyth 1994), among others. Such investigations have not been limited to overt pronoun languages. Pro-drop languages with rich agreement morphology such as Italian (Carminati 2002; Carminati et al. 2008) and Spanish (Filiaci et al. 2013; Gelormini-Lezama 2020; Gelormini-Lezama and Almor 2011) have also been delved into. However, comparatively fewer studies have looked at what Huang (1984) calls “cool languages”, languages without elaborate agreement morphology – such as Korean, Japanese, and Chinese – particularly regarding how speakers identify antecedents.

Previous work on the relationship between null pronouns and antecedents in cool languages consistently demonstrates that both the interpretation and the use of null pronouns depend strongly on discourse factors. For example, Kwon and Sturt (2013) report that Korean relies more on discourse cues than on morphological markers when assigning references to null pronouns, aligning with Huang’s original classification. In a similar vein, Hwang (2023) finds that discourse continuity influences speakers’ choices of referential forms in Korean. Kim and Chun (2023) further show that the way a discourse unfolds can be based on an implicit causal relationship signaled by the lexical semantics of the verb, in combination with the topicality marked by -(n)un. Finally, the production study by Ueno and Kehler (2016) indicates that discourse factors generally outweigh grammatical cues in shaping null pronoun interpretation.

While Korean presents a valuable case of null pronoun interpretation without robust verbal inflection, it is important to acknowledge that cross-linguistic constraints on pronoun or topic drop vary in significant ways beyond morphological richness. For instance, topic drop has been attested in non-pro-drop languages like German and English, particularly in informal registers (Haegeman 1990; Huang 1984). In languages like Japanese, topic drop is systematic and influenced by discourse salience (Kameyama 1990). Some languages allow only subject drop (e.g., Finnish), while others restrict drop based on syntactic or pragmatic constraints (Barbosa 2011). These cross-linguistic patterns suggest that the presence or absence of verbal agreement is not the sole predictor of null argument licensing. Recognizing this broader typological diversity highlights the relevance of examining Korean, which offers a compelling case where discourse structure and thematic roles, rather than morphological cues, guide pronoun interpretation.

Investigating the referent of a nonexistent element is inherently more complex. With overt pronouns, one can directly ask “Who or what does this pronoun refer to?” In cool languages, by contrast, the pronoun is not visible at all, requiring first the assumption that a missing element exists. This difference complicates both theoretical analyses and empirical methods, as researchers must establish not only how reference is assigned but also whether a covert pronoun has been used in the first place.

The complexity grows when one tries to compare overt pronouns with covert ones. Many studies on null pronoun languages have therefore relied on production tasks (Hwang 2023; Kim and Chun 2023; Ueno and Kehler 2016), which frequently involve overt pronouns uncommon in actual language use. Real-time comprehension research often uses reading times as a proxy for online processing cost, yet it remains impossible to measure how long it takes to process a nonexistent element. To work around this, researchers have measured reading times over multiple regions or entire sentences in self-paced reading tasks (Gelormini-Lezama 2020; Gelormini-Lezama and Almor 2011; Shoji et al. 2017); however, these methods cannot directly capture how listeners or readers respond to full NPs versus null pronouns in the same way that studies on overt-pronoun languages can. The current study probes into a peculiar Korean construction that allows the investigation of the relationship between discourse and null pronouns without making a comparison between null and overt pronouns.

2 Background

2.1 Thematic roles and topic status

Sentence (1) is ambiguous between ‘Cengmi must be worried’ and ‘Cengmi must be worrisome’, with Cengmi as an experiencer of worry or the stimulus. The ambiguity arises from the so-called double-nominative construction. Although Korean two-place psych-predicates take a dative experiencer and a nominative stimulus in the canonical structure seen in (2), they can also form a double-nominative construction, as in (3), in which case the word order determines the thematic roles: the experiencer always precedes the stimulus, differentiating (3a) from (3b) in meaning. With one of the two arguments dropped, sentence (1) is ambiguous, and the context clarifies the thematic role of the sole overt NP. Previous studies (Ahn 2017, 2018) reported that the overt NP in sentences like (1) was interpreted as an experiencer when topics shifted but as a stimulus when the same topic continued. That is, a significant dependence between topic status and thematic role was observed.[1]

| Cengmi-ka | kekcengsulewun | ka | po-ta. |

| Cengmi-nom | worried/worrisome | ka | aux-dec |

| ‘Cengmi must be worried/worrisome.’ | |||

| Cengmi-eykey | Yuna-ka | kekceng-sulewun | ka | po-ta. |

| Cengmi-dat | Yuna-nom | worry-adj | ka | aux-dec |

| ‘To Cengmi, Yuna must be worrisome.’ | ||||

| Cengmi-ka | Yuna-ka | kekceng-sulewun | ka | po-ta. |

| Cengmi-nom | Yuna-nom | worry-adj | ka | aux-dec |

| ‘Cengmi must be worried about Yuna.’ | ||||

| Yuna-ka | Cengmi-ka | kekceng-sulewun | ka | po-ta. |

| Yuna-nom | Cengmi-nom | worry-adj | ka | aux-dec |

| ‘Yuna must be worried about Cengmi.’ | ||||

Consider (4) and (5). In both (4) and (5), the two entities Cengmi and Yuna appear in the same order in the respective context sentences; however, the thematic roles they get to take in the critical sentences differ; Yuna is the experiencer in (4) but the stimulus in (5). As the experiencer always precedes the stimulus in the double-nominative construction, Yuna will always take the first NP position in (4) but Cengmi in (5), irrespective of its overtness.

Through this combination of the double-nominative construction and an NP drop, segmentally identical sentences as in (4a) and (5b) and in (4b) and (5a) are interpreted differently: Yuna is experiencer in (4a) but stimulus in (5b), and Cengmi is stimulus in (4b) but experiencer in (5a).

| Topic shift | ||||||

| ecey | cenyek-ey | cengmi-nun | yuna-eykey | phoklyekcekin | namcachinkwu-ey | tayhay |

| yesterday | evening-at | Cengmi-top | Yuna-dat | violent | boyfriend-about | about |

| thelenoh-ass-ta. | ||||||

| confide-pst-dec | ||||||

| ‘Last night, Cengmi confided in Yuna about (her) violent boyfriend.’ | ||||||

| yuna-ka | (cengmi-ka) | kekceng-sulewe-ss-nunci | heyecila-ko |

| Yuna-nom | (Cengmi-nom) | worry-adj-pst-conj | separate-comp |

| chwungkohay-ss-ta. | |||

| advise-pst-dec | |||

| ‘Yuna must have been worried (about Cengmi), (Yuna) advised (Cengmi) to leave (her boyfriend).’ | |||

| (yuna-ka) | cengmi-ka | kekceng-sulewe-ss-nunci | heyecila-ko |

| (Yuna-nom) | Cengmi-nom | worry-adj-pst-conj | separate-comp |

| chwungkohay-ss-ta. | |||

| advise-pst-dec | |||

| ‘(To Yuna) Cengmi must have been worrisome, (Yuna) advised (Cengmi) to leave (her boyfriend).’ | |||

| Topic Continuation | |||||||

| ecey | cenyek-ey | cengmi-nun | yuna-uy | phoklyekcekin | namcachinkwu-ey | tayhay | |

| yesterday | evening-at | Cengmi-top | Yuna-gen | violent | boyfriend-about | about | |

| alkey | toy-ess-ta. | ||||||

| aware | become-pst-dec | ||||||

| ‘Last night, Cengmi learned about Yuna’s violent boyfriend.’ | |||||||

| cengmi-ka | (yuna-ka) | kekceng-sulewe-ss-nunci | heyecila-ko |

| Cengmi-nom | (Yuna-nom) | worry-adj-pst-conj | separate-comp |

| chwungkohay-ss-ta. | |||

| advise-pst-dec | |||

| ‘Cengmi must have been worried (about Yuna), (Cengmi) advised (Yuna) to leave (her boyfriend).’ | |||

| (cengmi-ka) | yuna-ka | kekceng-sulewe-ss-nunci | heyecila-ko |

| (Cengmi-nom) | Yuna-nom | worry-adj-pst-conj | separate-comp |

| chwungkohay-ss-ta. | |||

| advise-pst-dec | |||

| ‘(To Cengmi) Yuna must have been worrisome, (Cengmi) advised (Yuna) to leave (her boyfriend).’ | |||

Previous studies (Ahn 2017, 2018, 2024) reported that speakers prefer cases where the same overt NPs are not repeated as the first NP across two adjacent sentences: (4a) and (5b) were either judged more acceptable or used more frequently over (4b) and (5a). Ahn (2018) asked participants to create a story using an ambiguous sentence as in (1) at the beginning, middle, and end of the story (see Figure 1), which manipulated the topic status. The study found that participants tended to create a story with the overt NP in (1) as the experiencer when the given construction had to be placed at the beginning, which required a new topic. When the construction had to be placed in the middle or at the end, where the same topic tended to continue, the experiencer reading decreased while the stimulus reading increased. That is, segmentally identical NPs were assigned different thematic roles depending on topic status.

Illustration of three story-completion conditions in Ahn (2018). (a) Beginning (b) middle (c) end.

A caveat in interpreting the results of the study was that the relationship between topic status and thematic role was not dichotomous nor was it the case that middle and end conditions always resulted in topic continuation. Even in middle and end conditions, topics shifted, in which case the stimulus reading was extremely rare. In general, participants tended to interpret the sole NP of the ambiguous construction (1) as the experiencer, even in the middle and end conditions. But the ratio of the experiencer reading significantly decreased in the middle and end conditions, where topic continuation was more likely.

One might wonder if the ambiguous construction is more commonly used with the overt NP as the experiencer in naturally occurring texts; however, a corpus analysis (Ahn 2024) shows that the overt NP in such a construction is significantly more likely to be a stimulus. The overall experiencer reading preference could be an artifact of a controlled study, where participants were given the critical sentence out of context as in Figure 1. Yet it demonstrates that, out of context, the construction’s default interpretation skews toward the experiencer.

The observed interaction between topic status and thematic role was accounted for in terms of the repeated name penalty (RNP) in the centering theory framework (Gordon et al. 1993; Grosz et al. 1995). The next section briefly introduces the concept and discusses whether it can best account for the phenomenon at hand.

2.2 The repeated name penalty

In the centering theory framework (Gordon and Chan 1995; Gordon and Scearce 1995; Gordon et al. 1993; Grosz et al. 1995), if two consecutive sentences have the same discourse center or discourse topic, the second sentence has the topical entity pronominalized. The topic of (6a) is Bruno, and the same topic is continued in (6b). Via a self-paced reading task, Gordon et al. (1993) showed that reading times increased when the continued topic was repeated as a definite description (Bruno in this case): hence, the repeated name penalty.

| Bruno was the bully of the neighborhood. |

| He / Bruno chased Tommy all the way from school one day. |

Two assumptions are made for the RNP to explain the interaction between topic status and thematic role in (4) and (5). One is that unstressed English pronouns are equivalent to null pronouns in Korean, and the other is that the topic of the sentence is the entity that the sentence is about. With such assumptions, the topic is Yuna in both (4a) and (4b), but Cengmi in (5a) and (5b), irrespective of its overtness. When the topic shifts from Cengmi to Yuna in (4), the new discourse topic should be referred to as a definite description, which explains why (4a) is preferred over (4b). Also, when the same topic (Cengmi) continues in (5), the continued topic should be pronominalized to avoid the repetition of the same NP, which means, in Korean, it should be a null pronoun. This accounts for the preference of (5b) over (5a).

However, the RNP in the centering theory framework focuses mainly on the comprehension of an overt pronoun, and its main argument is based on the assumption that seeing or hearing an overt pronoun provides a cue for listeners and readers to expect the existing discourse topic to continue. In contrast, no overt pronouns can provide such a cue in the Korean construction at issue here. Only when a definite NP is repeated as the topic can the RNP be applied.

The RNP predicts processing difficulty when the same NP is repeated in two consecutive sentences, that is, a main effect of NP repetition. This main effect is also an interaction effect between topic status and thematic role in that NPs are not repeated in the combination between topic shift and experiencer (4a) and that between topic continuation and stimulus (5b) while NPs are repeated in the other cases: (4b) and (5a). Crucially, since the RNP discusses the penalty for the repetition of the topical NP, the effect of repetition should appear when the overt NP is repeated; that is, at or right after the overt NP of the critical sentence. Earlier RNP studies (Gordon and Chan 1995; Gordon and Scearce 1995; Gordon et al. 1993; Yang et al. 1999) and later studies that tested RNP on null pronoun languages (Gelormini-Lezama 2020; Gelormini-Lezama and Almor 2011; Shoji et al. 2017) report summed reading times of several regions. From these studies that used phrase- or sentence-level RTs, it is difficult to tell if the effect of NP repetition is immediate or not. However, Eilers et al. (2019) report time-locked reactions to the (non-)repetition of NPs in German via an eye-tracking-while-reading task; the effects were observed on the anaphor or right after. Therefore, a word-by-word self-paced reading experiment is called for to investigate whether speakers’ sensitivity to NP repetition can be detected in real time.

Another question arises as to whether the RNP can explain the interdependence between topic status and thematic role described above. In (6), both forms (He and Bruno) refer to the same entity and take the same thematic role (the agent of chased). However, the Korean case compares overt NPs referring to different thematic roles. A separate measure is required to probe the interpretation of the overt NP. According to Ferreira and Yang (2019), comprehension questions are not simple tools to ensure that participants pay attention to the content of the test items. They can indicate whether participants misinterpret the sentences and whether the misinterpretations are revised or linger. The current study attempts to probe which thematic role is assigned to the overt NP in the critical sentence by asking who performed an action to stimulate the psychological state.

| nwukwu-uy | namcachinkwu-ka | phoklyekcek-i-nka? |

| who-gen | boyfriend-nom | violent-be-Q |

| ‘Whose boyfriend is violent?’ | ||

A comprehension question as in (7) can probe whether a reader can identify the stimulus in the critical sentence of (4) and (5). Measuring the accuracy of the answers to such comprehension questions will shed light on the disambiguation of the ambiguity in (1).

2.3 Research questions

Three key observations have been highlighted so far that motivate the current study. First, two-place psych-predicates with double-nominative constructions introduce thematic role ambiguity between an experiencer and a stimulus when one of the required arguments is dropped. Prior work suggests that context – particularly whether a discourse topic is shifting or continuing – interacts with this ambiguity. Second, the RNP offers one explanation by focusing on the cost of repeating a topical NP, but it is not obvious that it generalizes straightforwardly to Korean, where discourse can hinge on null elements. Third, the overt NP of the ambiguous construction (1) tends to be interpreted as the experiencer outside the context.

Given these previous findings, the present study directly examines how speakers resolve the thematic role ambiguity of psych-predicate constructions by topic status. By collecting word-by-word reading times and comprehension data, we aim to (i) test whether RNP effects emerge when the same NP is repeated in adjacent sentences and (ii) determine whether thematic roles are properly assigned to an overt NP, which will indicate the thematic role of the missing element. If the RNP alone can explain the relationship between topic status and thematic role in (4) and (5), we expect the effect of repetition (as in the form of interaction between topic status and thematic role) at or right after the overt NP region. Furthermore, if the experiencer reading bias observed in previous studies was an experimental artifact, the effect of thematic role should not be observed in the current study, in which the critical sentence is always contextualized.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Eighty native Korean speakers (64 female) were recruited from a major university community in Seoul for monetary compensation. Participation was limited to those who had not used languages other than Korean with their parents or caregivers and had not lived outside Korea for more than six consecutive months before age 7.

3.2 Stimuli

Experimental items were designed to have a context sentence and a critical sentence as in (4) and (5). Each context sentence introduced two referents of the same gender to prevent any gender biases. Each item was counter-balanced in a 2 × 2 Latin-square design so no participant would see the same item through different conditions. After each critical item was a comprehension question asking who stimulated the psychological state. A complete list of critical items is given in the Appendix. Forty fillers, without psych-predicates, had two sentences as in the experimental items and were followed by a comprehension question asking about the main idea or details of the sentence contents.

3.3 Procedure

After a screening survey, participants were invited into a Zoom session and were asked to turn their cameras and microphones on to ensure they were participating in the experiment in a quiet space with no disruptions. The experiment was conducted via the Penn Controller for IBEX platform (Zehr and Schwarz 2018). Since the platform downloads all experimental stimuli into a user’s local temporary folder before the experiment begins, no delays or disturbances were expected due to varying internet connection. Each item was presented word by word as participants pressed the space bar, and the comprehension questions appeared after the context and critical sentence screen was cleared. The entire session of instructions, consent form signing, practice trials, and experiment trials took approximately 45 min.

3.4 Analysis

Raw reading times (RTs) per character were first transformed to logarithms to normalize skewed data; then, residuals were calculated in a linear mixed-effects model that factored in word length, word position, and trial order, all of which were centered and scaled, with participant intercepts as random effects.[2] Log RT residuals that exceeded three standard deviations below or above the mean were filtered out, which resulted in 2.04 % of data loss. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team 2024) using lme4 version 1.1.31 (Bates et al. 2015) and lmerTest version 3.1.3 (Kuznetsova et al. 2017). In linear mixed-effects modeling for RT data analyses, fixed factors were centered; thematic roles (experiencer as −0.5 vs. stimulus as 0.5) and topic status (continue −0.5 vs. shift 0.5). Only participant and item intercepts were included for random effects. The maximal random-effects structure resulted in singularity issues, different combinations of slopes were compared, and more complex models did not significantly differ from the intercept-only model (Barr et al. 2013; Matuschek et al. 2017). Since RTs in self-paced reading are heavily affected by the RTs of previous words, log RT residuals of two immediately preceding words were factored in (Hofmeister 2011).[3] Responses to comprehension questions were analyzed using logistic mixed-effects regression with topic status and thematic role as fixed factors and participant and item for random effects.[4]

4 Results

The data were analyzed to probe whether an effect of NP repetition is observed at or right after the repeated overt NP, whether thematic roles are properly assigned, and whether the thematic role bias is observed at or right after the psych-predicate. The effect of NP repetition, measured via RT changes, was observed not at or right after the overt NP. Instead, an unexpected main effect of topic status was observed in the overt NP region. An interaction effect of topic status and thematic role was observed in the region after the psych-predicate. Regarding the thematic role assignment, the analysis of comprehension accuracy resulted in an interaction effect of topic status and thematic role and a main effect of thematic role, which indicated that participants interpreted the sentence more accurately when the overt NP was an experiencer regardless of the topic status. The effect of the experiencer bias appeared as an increase in RT between the psych-predicate region and the following region.

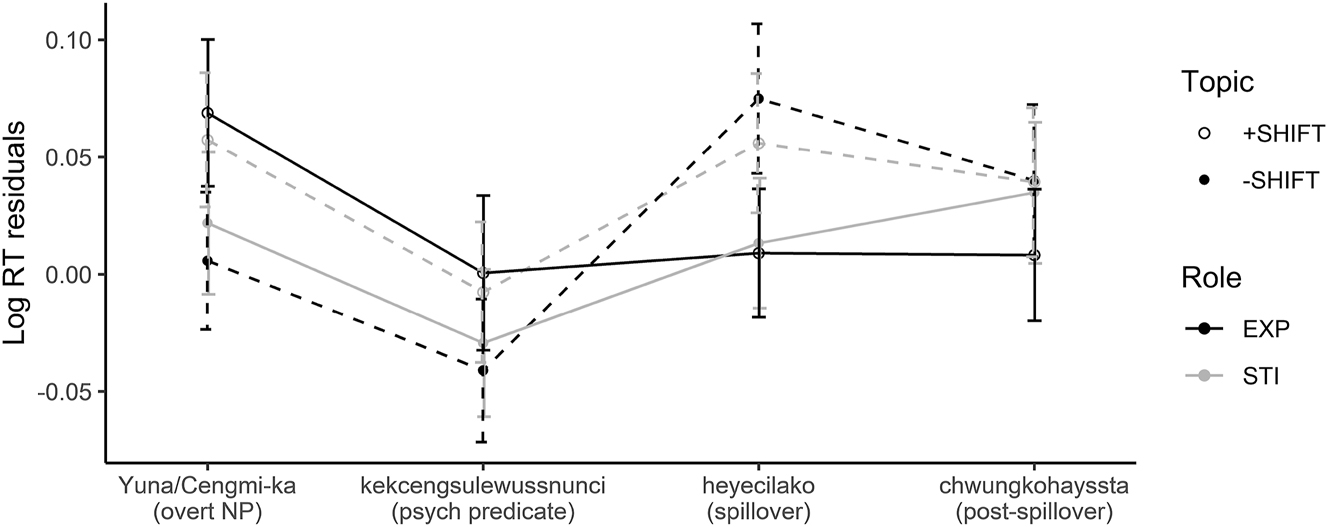

4.1 Reading times

Figure 2 shows the residuals of the log-transformed RT data in four regions: the overt NP, the psych-predicate, and two additional regions after the psych-predicate. The black and gray lines indicate the experiencer and stimulus readings of the overt NP, respectively, and the filled and unfilled circles indicate the shift and continuation of the topics. The solid and dashed lines indicate the results of combining the two factors. If the overt NP is the experiencer in the topic shift (+SHIFT) condition (4a) or the stimulus in the topic continuation (−SHIFT) condition (5b), the NP is not repeated, indicated by the solid lines. On the other hand, if the overt NP is the stimulus when the topics shift (+SHIFT) (4b) or the experiencer when the topic continues (−SHIFT) (5a), the NP is repeated, indicated by the dashed lines. The error bars indicate 95 % confidence intervals. The subject region with the overt NP of thematic role ambiguity is the region right after the last word of the context sentence. The next region is the critical region where the psych-predicate is given, which, in turn, is followed by spillover and post-spillover regions.

Log RT residuals by region.

The RNP predicted an effect of overt NP repetition at or right after the overt NP, which should have appeared in the form of interaction between topic status and thematic role, but it was not observed in the overt NP region nor in the psych-predicate region. Instead, an effect of topic status was observed in the overt NP region. Log-transformed RT residuals showed a significant increase in the topic shift condition (β = 0.042, SE = 0.014, t = 2.938, p = 0.003). The significance remained the same with or without the previous word analysis in all RT analyses (see Table 1 for complete statistics).

Fixed effects coefficients for log RT residuals in the overt NP region.

| Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | t value | Pr(>|t|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −1.265 | 0.141 | −1.542 | −0.988 | −8.985 | 0.000 | *** |

| Topic | 0.042 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.070 | 2.938 | 0.003 | ** |

| Theme | 0.002 | 0.014 | −0.026 | 0.030 | 0.111 | 0.912 | |

| Previous word 1 | 0.159 | 0.022 | 0.116 | 0.202 | 7.271 | 0.000 | *** |

| Previous word 2 | 0.066 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.113 | 2.788 | 0.005 | ** |

| Topic:Theme | −0.017 | 0.028 | −0.073 | 0.039 | −0.608 | 0.543 |

An interaction effect of topic status and thematic role was observed in the spillover region, the region right after the psych-predicate (β = 0.106, SE = 0.027, t = 3.973, p < 0.001).[5] Table 2 summarizes fixed effects coefficients and relevant statistics for log RT residuals in the spillover region. A pairwise comparison analysis was performed, and a significant difference was observed between experiencer NPs and stimulus NPs in the topic shift condition, that is, between (4a) and (4b) (β = −0.053, SE = 0.019, t = −2.759, p = 0.012). In the topic continuation condition, experiencer NPs (5a) were read significantly longer than stimulus NPs (5b) (β = 0.053, SE = 0.019, t = 2.773, p = 0.012). Experiencer NPs were read significantly faster in the topic shift condition (4a) than in the topic continuation condition (5a) (β = 0.070, SE = 0.019, t = 3.631, p = 0.002). Stimulus NPs were read marginally faster when the topic continued (5b) than when it shifted (4b) (β = −0.037, SE = 0.019, t = −1.906, p = 0.085).

Fixed effects coefficients for log RT residuals in the spillover region.

| Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | t value | Pr(>|t|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.908 | 0.153 | −1.208 | −0.608 | −5.933 | 0.000 | *** |

| Topic | −0.016 | 0.014 | −0.043 | 0.011 | −1.204 | 0.229 | |

| Theme | 0.000 | 0.014 | −0.028 | 0.028 | 0.004 | 0.997 | |

| Previous word 1 | 0.123 | 0.024 | 0.076 | 0.170 | 5.232 | 0.000 | *** |

| Previous word 2 | 0.039 | 0.023 | −0.006 | 0.084 | 1.725 | 0.085 | . |

| Topic:Theme | 0.106 | 0.027 | 0.054 | 0.158 | 3.973 | 0.000 | *** |

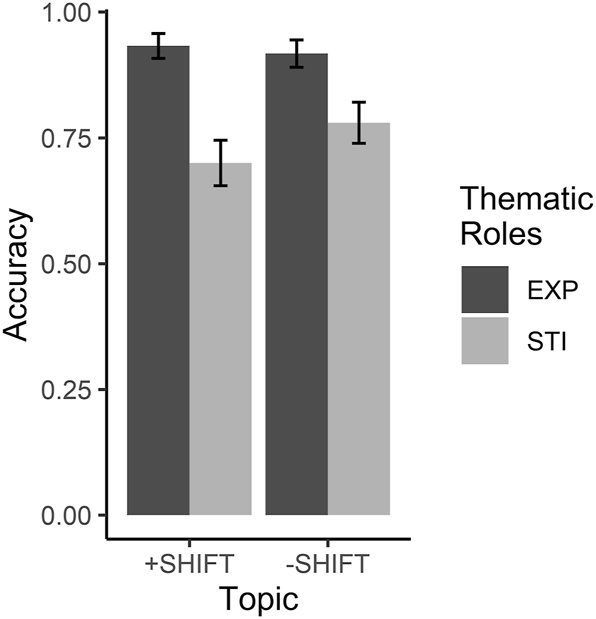

4.2 Comprehension accuracy

The comprehension accuracy data is summarized in Table 3. Comprehenders showed a higher accuracy when the overt NP was an experiencer than when it was a stimulus. Also, the decrease in the accuracy ratio from the experiencer reading to the stimulus reading was greater in the topic shift condition than in the topic continuation condition.

Comprehension accuracy ratio by topic status and thematic role.

| Topic status | Thematic role | N | Accuracy | SD | SE | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift | Experiencer | 400 | 0.933 | 0.251 | 0.0126 | 0.025 |

| Shift | Stimulus | 400 | 0.700 | 0.459 | 0.023 | 0.045 |

| Continue | Experiencer | 400 | 0.918 | 0.275 | 0.014 | 0.027 |

| Continue | Stimulus | 400 | 0.780 | 0.415 | 0.021 | 0.041 |

Figure 3 visualizes the accuracy ratio by topic status and thematic role, and Table 4 summarizes the fixed effect coefficients and relevant statistics of a logistic mixed-effects model. A significant main effect of thematic role (β = −1.612, SE = 0.169, t = −9.530, p < 0.0001) and a significant interaction effect of topic status and thematic role (β = −0.704, SE = 0.324, t = −2.175, p = 0.030) were observed. Also, a pairwise comparison analysis was conducted and significant differences were found in all pairs of conditions (p < 0.001) except between topic shift and continuation when the overt NP was experiencer. That is, the difference between the two highest bars in Figure 3 was insignificant (β = 0.806, SE = 0.222, z = −0.782, p = 0.434).

Comprehension question accuracy by topic status and thematic role.

Fixed effects coefficients for comprehension accuracy.

| Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | z value | Pr(>|Z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.080 | 0.178 | 1.730 | 2.429 | 11.663 | 0.000 | *** |

| Topic | −0.1367 | 0.167 | −0.463 | 0.190 | −0.818 | 0.413 | |

| Theme | −1.612 | 0.169 | −1.944 | −1.280 | −9.530 | 0.000 | *** |

| Topic:Theme | −0.704 | 0.324 | −1.338 | −0.070 | −2.175 | 0.030 | * |

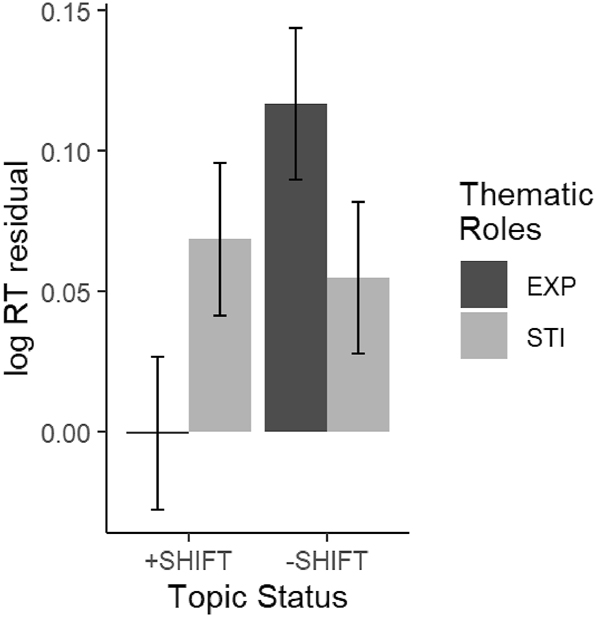

4.3 Experiencer bias

Despite contextualization, comprehension accuracy data indicated a significant bias toward experiencer reading. To probe whether the experiencer bias also influenced RTs, the RT difference between the psych-predicate and spillover regions was analyzed. The overt NP can be assigned a thematic role only when the psych-predicate is presented. If participants are biased to interpret the overt NP as the experiencer in the critical region, the interpretation will suit the context only in (4a), in which an experiencer NP was intended in the topic shift condition. In the three other conditions, experiencer reading will not make sense, and RTs will increase.

Figure 4 shows that the RT difference between the psych-predicate and spillover regions in the topic shift/experiencer condition (4a) nears zero, while the three other conditions show significant differences. The RT difference between the psych-predicate and spillover regions was modeled with topic status and thematic role as fixed effects and participants and items as random effects, and the model resulted in a main effect of topic status (β = 0.052, SE = 0.018, t = 2.819, p = 0.005) and an interaction effect of topic status and thematic role (β = −0.131, SE = 0.036, t = −3.654, p = 0.0003). Pairwise comparisons also showed significant differences between the topic shift/experiencer condition and the three other conditions (p < 0.05). Table 5 summarizes the fixed effects coefficients of RT differences between the psych-predicate and spillover regions.

RT difference between the critical and spillover region.

Fixed effects coefficients for RT difference between psych-predicate and spillover regions.

| Estimate | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | t value | Pr(>|t|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.060 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.102 | 2.762 | 0.010 | ** |

| Topic | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.088 | 2.819 | 0.005 | ** |

| Theme | 0.004 | 0.018 | −0.033 | 0.040 | 0.194 | 0.846 | |

| Topic:Theme | −0.131 | 0.036 | −0.202 | −0.061 | −3.654 | 0.000 | *** |

5 Discussion

The present study began with the questions of whether the RNP from the centering theory framework (Gordon et al. 1993; Grosz et al. 1995) applies to a null pronoun language like Korean, whether thematic roles are assigned appropriately to overt NPs, and whether the experiencer bias observed out of context will be replicated within contexts. The RT analysis results raise questions about whether the RNP can adequately account for the Korean construction in the current study. Comprehension accuracy and RT change data suggest that the thematic role assignment could be biased toward the experiencer even when the critical sentence was contextualized.

The RNP predicted a real-time effect of overt NP repetition, which could be proxied by an interaction between topic status and thematic role, but the effect appeared later, after the psych-predicate. One might argue that the interaction effect observed in the spillover region was a delayed effect from two regions earlier, the overt NP region. However, the possibility cannot be easily dismissed that the RNP, based mainly on overt pronoun languages, does not apply to the null pronoun language Korean. The repetition of NPs might be more allowable in null pronoun languages, especially in Korean, in which verb inflections rarely complement missing pronouns. The delayed effect observed in the current study could be an epiphenomenon of comprehenders’ realization of what arguments are required after they encounter the psych-predicate. Once they identify the required arguments and determine which argument is overtly realized and which is covertly realized, they can compute the cost of processing overt NPs and null pronouns, as well as their respective functions in the discourse, and decide whether it is justifiable to use a phonologically and semantically richer form. That is, the pattern of RTs observed might not be due to the repetition of NPs per se.

Regarding the thematic role assignment, the results of the comprehension accuracy analyses suggest that the interpretation of the overt NP is biased toward the experiencer. Regardless of the topic status, the accuracy ratio was higher when the overt NP was the experiencer. This finding is noteworthy in that previous studies (Ahn 2016, 2018) presented the critical sentence and had participants create the context, while the current study presented the context first and the critical sentence was situated within contexts. Not only the comprehension accuracy data but also the RT change between the psych-predicate and the spillover regions corroborates the experiencer bias. With the experiencer bias, participants might assign the thematic role of experiencer when they encounter the psych-predicate, regardless of the context. However, as they integrate the proposition within the context, they realize that their interpretation should be revised, except in cases where the overt NP is the experiencer. The process of revision was manifested as significant RT increases in the three conditions in which experiencer reading was inappropriate (see Figure 4).

This bias toward the experiencer reading requires further investigation for the following two reasons. First, a corpus study (Ahn 2024) shows that the types of two-place psych-predicates used in the current study have their stimulus argument overtly realized significantly more than their experiencer argument when only one of the two required arguments was realized as in (1). Second, the psych-predicates themselves are attributive adjectives that describe the stimulus. When one considers that the canonical structure of the psych-predicates takes a dative experiencer and a nominative stimulus, the experiencer reading bias observed in the current and previous studies does not align with natural language data.

Finally, there was an unexpected main effect of topic status observed in the overt NP region. The context sentences were not identical across conditions; the items in the topic continuation condition were longer (μ = 46.18 words) than those in the topic shift condition (μ = 44.38 words). Hence, the longer RTs in the topic shift condition could be due to the length difference of context sentences between the topic shift and continuation conditions (t = 2.293; df = 77.76; p = 0.025). However, the RTs were log-transformed and residualized, and the models factored into the spillover effects of two previous words. The main effect of topic status in the overt NP region cannot be simply dismissed as an experimental artifact.

A speculative potential account for the phenomenon, which will require scrutiny in future research, is that participants’ focus on discourse entities might move depending on the lexical properties of verbs used. That is, in (4), the first NP Cengmi confides in the second NP Yuna about her boyfriend whereas in (5), Cengmi learns about Yuna’s boyfriend. Items in the topic shift condition include verbs such as ‘brag’, ‘request’, or ‘slap’, which require proto-agent roles (Dowty 1991) in the subject positions. On the other hand, verbs in the topic continuation condition include ‘be told’, ‘be requested’, or ‘be slapped’, for which the subjects take on proto-patient roles (Dowty 1991). The proto-agent property in the topic shift condition and the proto-patient (or thematic) property in the topic continuation condition are consistent throughout all critical items.

Proto-agents cause an event or change of state in another participant according to Dowty (1991). In that sense, ‘bragging’, ‘requesting’, or ‘slapping’ affects the other party while ‘being told’, ‘being requested’, or ‘being slapped’ indicates undergoing a change of state or being causally affected by the other party. Stevenson et al. (1994) have shown that antecedents related to the consequences of an event are preferred. That is, when the previous sentence has an agent in the first NP position and a patient as the second NP, a patient NP is more likely taken as the antecedent for the pronoun in the subsequent sentence. This implies that participants shift their focus from one entity to the other in the topic shift condition within the context sentence. On the other hand, no such focus shift is expected in the topic continuation condition if similar preference as in Stevenson et al. (1994) is applicable in Korean. Since the thematic role of the second NP in (4) and the first NP in (5) were both experiencer, the experiencer bias observed might also be explained by the coherence account.

That the coherence relation between sentences might be predictable is certainly an intriguing possibility, opening the door to stronger connections between the findings of the current study and broader discourse coherence theories (Kehler 2002; Kehler and Rohde 2013, 2019; Kehler et al. 2008; Rohde and Kehler 2013; Rohde et al. 2006). Nonetheless, our current data only allows us to speculate about such predictability. Future research will need to explore it in greater depth.

6 Conclusions

The current study aimed to clarify the mechanisms involved in the interpretation of null pronouns through thematic role ambiguity in Korean double-nominative psych-predicate constructions. By employing a carefully designed self-paced reading experiment, we primarily investigated the predictions derived from the RNP within the centering theory framework while also probing the experiencer bias observed in previous studies.

Our findings revealed that the interaction between topic status and thematic role emerged only after the psych-predicate region, suggesting that the RNP may not sufficiently explain the online processing difficulty associated with interpreting ambiguous null pronouns in Korean. Instead, participants showed sensitivity to thematic roles and aspects of discourse, with significant RT differences reflecting both thematic role assignment and topic status. In particular, our comprehension accuracy data indicated a bias toward interpreting overt NPs as experiencers, regardless of discourse context. This calls for a future study to investigate whether an inherent preference may overshadow discourse manipulations. Finally, RT increases between the psych-predicate and spillover regions indicate the process of revising the initial biased interpretation. Together, these results indicate that, beyond simple repetition effects, factors relating to discourse structure play a critical role in how comprehenders resolve thematic role ambiguity and interpret null pronouns in Korean.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5B5A07111230).

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest related to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Appendix: The complete list of critical stimuli

Each item had four different versions in a 2 × 2 design. The first NP of the context sentence was either stimulus or experiencer, and the critical sentence had either the second or the first NP overtly realized. The first sentences in each item (marked CX) are context sentences, and the second sentences (marked CR) are critical sentences.

| CX: | ecey cenyekey cengminun [yunaeykey/yunauy] phoklyekcekin namca chinkwuey tayhay [thelenohassta / alkey toyessta]. |

| ‘Last night, [Jungmi confided in Yunah about her violent boyfriend / Jungmi found out about Yunah’s violent boyfriend.]’ | |

| CR: | [yunaka/cengmika] kekcengsulewessnunci heyecilakwo chwungkwohayssta. |

| ‘[Yuna/Jungmi] must have been [worried/worrisome], she told her to leave him.’ |

| CX: | tongchanghoyeyse cenganun [unmieykey/unmika] saylo san catongcha [calangul hayssta / calanghanun kesul tulessta]. |

| ‘At the homecoming party, [Jungah bragged to Eunmi about her new car / Jungah heard Eunmi bragging about her new car].’ | |

| CR: | [unmika/cengaka] pwulewessnunci malepsi calilul phihayssta. |

| ‘[Eunmi/Jungah] must have been [envious/envied], she quietly left the room.’ |

| CX: | swuep kkuthnako kyengswunun tongwueykey swukceylul [towatallako/-nun] pwuthakul [hayssta/patassta] |

| ‘After class, Kyungsoo [asked Dongwoo / was asked by Dongwoo] to help with homework.’ | |

| CR: | [tongwuka/kyengswuka] kwichanhassnunci papputanun phingkyeylul tayssta. |

| ‘[Dongwoo/Kyungwoo] must have been [bothered/bothersome], he gave an excuse that he was busy.’ |

| CX: | mincaynun [unhoeykey/unhoka] ccaksalanghanun yeca ttaymwuney [himtultako malhayssta / himtulehanun kesul alkey twoyessta]. |

| ‘[Minjae told Eunho that he was suffering for a crush / Minjae found out that Eunho was suffering for a crush.]’ | |

| CR: | [unhoka/mincayka] taptaphayssnunci kopaykhanun kesul towacwukeysstako hayssta. |

| ‘[Eunho/Minjae] must have been [frustrated/frustrating], he told him that he would help.’ |

| CX: | yengminun [ciswueykey/ciswuka] mwutcito anhko [ciswuuy mwulkenul kacyekassta / caki mwulkenul kacyekanun kel poassta]. |

| ‘[Youngmi took Jisu’s stuff without asking / Youngmi saw Jisu taking her stuff without asking].’ | |

| CR: | [ciswuka/yengmika] mosmattanghayssnunci taumpwuthenun helakul patulako hwalul nayssta. ‘[Jisu/Youngmi] must have been [displeased/displeasing], she told her to ask for permission next time.’ |

| CX: | onul achimey mincinun yumieykey [solilul cilukwo ppyamul ttaylyessta / ppyamul macko kepey cillye tomangchyessta]. |

| ‘This morning, [Minji screamed at Yumi and slapped her / Minji got slapped by Yumi and ran away frightened].’ | |

| CR: | [yumika/mincika] mwusewessnunci chipul naka tolaoci anhassta. |

| ‘[Yumi/Minci] must have been [scared/scary], she left home and hasn’t come back. |

| CX: | halmeninun [sonnyeeykey kwakeey patun ollimphik kummeytalul poyecwuessta / sonnyeka ollimphikeyse kummeytalul ttan kesul alkey toyessta]. |

| ‘The grandmother [showed the granddaughter the Olympic Gold medal she won in the past / found out that the granddaughter won an Olympic Gold medal].’ | |

| CR: | [sonnyeka/halmenika] calangsulewessnunci kanun kos mata calangul hayssta. |

| ‘The [granddaughter/grandmother] must have been [pleased/pleasing], she bragged about it everywhere she went.’ |

| CX: | nolitheeyse yenghonun [minswueykey ppoppolul halyeko tallyetulessta / minswuka ppoppolul halyeko hay nollassta]. |

| ‘At the playground, Youngho [tried to kiss Minsu / was surprised that Minsu tried to kiss him].’ | |

| CR: | [minswuka/yenghoka] cingkulewessnunci sosulachimye tomangchyessta. |

| ‘[Minsu/Youngho] must have been [disgusted/disgusting], he ran away flabbergasted.’ |

| CX: | manwen pesu aneyse minhonun [pyengswueykey khun solilo umtamphayselul nulenohassta / pyengswuka khun solilo umtamphayselhanun kesul mallici moshayssta]. |

| ‘On a crowded bus, Minho [told Byungsoo dirty jokes / couldn’t stop Byungsoo from telling dirty jokes].’ | |

| CR: | [pyengswuka/minhoka] changphihayssnunci taum yekeyse coyonghi naylyessta. |

| ‘[Byungsoo/Minho] must have been [embarrassed/embarrassing], he got off the bus at the next stop quietly.’ |

| CX: | cwunsenun [unwueykey/unwuka] cinantaley ie tto tonul [pillyetallako hayssta/ pillyetallanun maley nwollassta]. |

| ‘Joonsuh [asked Eunwoo to lend him money/was surprised that Eunwoo asked him to lend him money] again after he did last month.’ | |

| CR: | [unwuka/cwunseka] hansimhayssnunci te isangun pillyecwul toni epstako hayssta. |

| ‘[Eunwoo/Joonsuh] must have [found him pathetic/been pathetic], he said that he had no more money to lend.’ |

| CX: | cwunkinun [kenwueykey/kenwuka] pithukhoiney cencaysanul [thwucahaysstako malhayssta /thwucahaysstanun kesul alkey toyessta]. |

| ‘Joonki [told Gunwoo that he/found out that Gunwoo] invested all his fortunes in the Bitcoin.’ | |

| CR: | kenwuka / cwunkika kekcengsulewessnunci camul ilwuci moshayssta. |

| ‘[Gunwoo/Joonki] must have been [worried/worrisome], he couldn’t sleep.’ |

| CX: | yongcaynun [tonghoeykey / tonghoka] pwucatulman moimey [chotayhacako malhayssta / chotayhayyahantako malhanun kel tulessta]. |

| ‘Yongjae [told Dongho / heard Dongho say] only the rich should be invited to the club.’ | |

| CR: | [tonghoka/yongcayka] kokkawessnunci moimeyse thalthoyhakeysstako malhayssta. |

| ‘[Dongho/Yongjae] must have felt [displeased/displeasing], (he) said (he) would leave the club.’ |

| CX: | yenganun cihuyeykey yenge kongpwuhanun kesul [towatallako pwuthakhayssta / towatallanun pwuthakul patassta]. |

| ‘Youngah [asked Jihee/was asked by Jihee] to help with studying English.’ | |

| CR: | [cihuyka/yengaka] kwichanhassnunci kapcaki yengelul moshanun chek hayssta. |

| ‘[Jihee/Youngah] must have been [bothered/bothersome], she suddenly pretended not to speak English.’ |

| CX: | miswunun [cengayeykey/cengayka] hoysa tonglyouy pwuthakul kecelhaki [himtultamye coenul kwuhayssta/himtulehanun kesul alkey toyessta]. |

| ‘Misoo [asked Jungae for advice that she/found out that Jungae] could not say no to a colleague at work.’ | |

| CR: | cengayka / miswuka taptaphayssnunci taysin mannase yaykihaycwuessta. |

| ‘[Jungae/Misoo] must have felt [frustrated/frustrating] that she delivered the message instead.’ |

| CX: | yuncaynun [kyuhwoeykey/kyuhoka] mathkyenohun tusi sipmanwenul [naynohulako hayssta /naynohulanun kesul ihayhal swu epsessta]. |

| ‘Yoonjae [demanded Kyuho for/couldn’t understand Kyuho for demanding] one hundred thousand won as if he had owed him.’ | |

| CR: | [kyuhwoka/yuncayka] mosmattanghayssnunci toni epstakwo capatteyssta. |

| ‘[Kyuho/Yoonjae] must have felt [displeased/displeasing], he insisted he didn’t have money.’ |

| CX: | cengcaynun [yunholul/yunhoeykey] kicelhatolok [ttayliko/macko] hantalmaney syophingmoleyse macwuchyessta. |

| ‘Jungjae [beat/was beaten by] Yoonho severely and ran into him at the shopping mall after a month.’ | |

| CR: | [yunhwoka/cengcayka] mwusewessnunci talun kosulo calilul phihayssta. |

| ‘[Yoonho/Jungjae] must have been [scared/scary], he left for another place.’ |

| CX: | samchonun [cokhaeykey/cwokhaka] malathon tayhoyeyse 1tunghan sacinul [poyecwuessta /sinmwuneyse poassta]. |

| ‘The uncle [showed the nephew his/saw in the newspaper his nephew’s] photograph of winning the first place in a marathon race.’ | |

| CR: | cokhaka / samchoni calangsulewessnunci insuthakulaymey sacinul ollyessta. |

| ‘The nephew/uncle must have felt pleased/pleasing, he posted the photo on Instagram.’ |

| CX: | mokyokthangeyse yunhuynun [cengmiuy/cengmika] kasumul mancilyeko [hayssta / hayse tanghwanghayssta]. |

| ‘At the public bath, Yoonhee [tried to touch Jungmi’s bosom/was surprised that Jungmi tried to touch her bosom].’ | |

| CR: | cengmika/yunhuyka cingkulewessnunci elkwulul cciphwulyessta. |

| ‘Jungmi/Yoonhee must have been disgusted / disgusting, she frowned.’ |

| CX: | pominun [chwicikthekul naykeysstamye hyenalul pwullenohko siktangeyse congepweneykey kapcilul hayssta / hyenaka chwicikthekul naynun calieyse siktang congepweneykey kapcilhanun kesul poassta]. |

| ‘Bomi, to celebrate her new job, invited Hyunah to a party and behaved rudely to a server at the restaurant / Bomi saw Hyunah behaving rudely at a party to celebrate her new job.’ | |

| CR: | hyenaka / pomika changphihayssnunci siksalul haci anhko pakkulwo nakassta. |

| ‘Hyunah / Bomi must have felt embarrassed / embarrassing, she left for outside without having a meal.’ |

| CX: | cihyeynun [kyengmieykey/kyengmika] ipeneyto thwucaey [silphayhaysstako malhayssta / silphayhan kesul alkey toyessta]. |

| ‘Jihye [told Kyungmi that she / found out that Kyungmi] lost her investment this time again.’ | |

| CR: | [kyengmika/cihyeyka] hansimhayssnunci te isang tonul pillyecwul swu epstako malhayssta. |

| ‘[Kyungmi/Jihye] must have [found her pathetic / been pathetic] she said she couldn’t lend her any more money.’ |

References

Ahn, Hyunah. 2016. Reference in discourse: The case of L2 and heritage Korean. In Michael Kenstowicz, Ted Levin & Ryo Masuda (eds.), Proceedings of the 23rd Japanese/Korean linguistics conference. Stanford: CSLI Publications. https://web.stanford.edu/group/cslipublications/cslipublications/ja-ko-contents/toc-jako23.shtml (accessed 23 October 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Ahn, Hyunah. 2017. The prosodic resolution of syntactic/semantic ambiguity: An exemplar-based account. Language Research 53(3). 501–524. https://doi.org/10.30961/lr.2017.53.3.501.Search in Google Scholar

Ahn, Hyunah. 2018. Prosody, syntax, and discourse: A three-way interaction. Korean Journal of Linguistics 43(1). 73–100.10.18855/lisoko.2018.43.1.004Search in Google Scholar

Ahn, Hyunah. 2024. The argument drop patterns of the psych-predicate mwusep- in spoken, written, and messenger corpora. Studies in English Language and Literature 50(2). 153–173.Search in Google Scholar

Barbosa, Pilar. 2011. Pro-drop and theories of pro in the minimalist program, part 2: Pronoun deletion analyses of null subjects and partial, discourse, and semi pro-drop. Language and Linguistics Compass 5. 571–587.10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00292.xSearch in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278.10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Bolker Ben & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Carminati, Maria Nella. 2002. The processing of Italian subject pronouns. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Carminati, Maria Nella, P. G. van Gompel Roger, Christoph Scheepers & Manabu Arai. 2008. Syntactic priming in comprehension: The role of argument order and animacy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34(5). 1098–1110.10.1037/a0012795Search in Google Scholar

Chambers, Craig G. & Ron Smyth. 1998. Structural parallelism and discourse coherence: A test of centering theory. Journal of Memory and Language 39(4). 593–608.10.1006/jmla.1998.2575Search in Google Scholar

Crawley, Rosalind A., Rosemary J. Stevenson & David Kleinman. 1990. The use of heuristic strategies in the interpretation of pronouns. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 19(4). 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01077259.Search in Google Scholar

Crinean, Marcelle & Alan Garnham. 2006. Implicit causality, implicit consequentiality and semantic roles. Language and Cognitive Processes 21(5). 636–648.10.1080/01690960500199763Search in Google Scholar

Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67(3). 547–619. https://doi.org/10.2307/415037.Search in Google Scholar

Eilers, Sarah, Simon P. Tiffin-Richards & Sascha Schroeder. 2019. The repeated name penalty effect in children’s natural reading: Evidence from eye tracking. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (Hove) 72(3). 403–412.10.1177/1747021818757712Search in Google Scholar

Ferreira, Fernanda & Zoe Yang. 2019. The problem of comprehension in psycholinguistics. Discourse Processes 56(7). 485–495.10.1080/0163853X.2019.1591885Search in Google Scholar

Filiaci, Francesca, Antonella Sorace & Manuel Carreiras. 2013. Anaphoric biases of null and overt subjects in Italian and Spanish: A cross-linguistic comparison. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 29(7). 825–843.10.1080/01690965.2013.801502Search in Google Scholar

Garnham, Alan, Svenja Vorthmann & Karolina Kaplanova. 2021. Implicit consequentiality bias in English: A corpus of 300+ verbs. Behavior Research Methods 53(4). 1530–1550.10.3758/s13428-020-01507-zSearch in Google Scholar

Garvey, Catherine & Alfonso Caramazza. 1974. Implicit causality in verbs. Linguistic Inquiry 5(3). 459–464.Search in Google Scholar

Gelormini-Lezama, Carlos. 2020. The overt pronoun penalty for plural anaphors in Spanish. In Diego Pascual y Cabo & Idola Elola (eds.), Current theoretical and applied perspectives on Hispanic and lusophone linguistics (Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics), 175–188. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ihll.27.08gelSearch in Google Scholar

Gelormini-Lezama, Carlos & Amit Almor. 2011. Repeated names, overt pronouns, and null pronouns in Spanish. Language and Cognitive Processes 26(3). 437–454.10.1080/01690965.2010.495234Search in Google Scholar

Gordon, Peter C. & Davina Chan. 1995. Pronouns, passives, and discourse coherence. Journal of Memory and Language 34(2). 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.1995.1010.Search in Google Scholar

Gordon, Peter C., Barbara J. Grosz & Laura A. Gilliom. 1993. Pronouns, names and the centering of attention in discourse. Cognitive Science 17(3). 311–347.10.1207/s15516709cog1703_1Search in Google Scholar

Gordon, Peter C. & Kimberly A. Scearce. 1995. Pronominalization and discourse coherence, discourse structure and pronoun interpretation. Memory and Cognition 23(3). 313–323.10.3758/BF03197233Search in Google Scholar

Grosz, Barbara J., Aravind K. Joshi & Weinstein Scott. 1995. Centering: A framework for modeling the local coherence of discourse. Computational Linguistics 22(2). 203–225.10.21236/ADA324949Search in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane. 1990. Non-overt subjects in diary contexts. In Joan Mascaró & Marina Nespor (eds.), Grammar in progress: Glow essays for Henk van Riemsdijk, 167–174. Dordrecht: Foris.10.1515/9783110867848.167Search in Google Scholar

Hofmeister, Philip. 2011. Representational complexity and memory retrieval in language comprehension. Language and Cognitive Processes 26(3). 376–405.10.1080/01690965.2010.492642Search in Google Scholar

Huang, C.-T. James. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15(4). 531–574.Search in Google Scholar

Hwang, Heeju. 2023. The influence of discourse continuity on referential form choice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 49(4). 626–641.10.1037/xlm0001166Search in Google Scholar

Kameyama, Megumi. 1990. Functional and conceptual control of zero anaphora: A critical review. Journal of Japanese Linguistics 12. 39–63.10.1515/jjl-1990-0117Search in Google Scholar

Kehler, Andrew. 2002. Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Kehler, Andrew, Laura Kertz, Hannah Rohde & Jeffrey L. Elman. 2008. Coherence and coreference revisited. Journal of Semantics 25(1). 1–44.10.1093/jos/ffm018Search in Google Scholar

Kehler, Andrew & Hannah Rohde. 2013. A probabilistic reconciliation of coherence-driven and centering-driven theories of pronoun interpretation. Theoretical Linguistics 39(1–2). 1–37.10.1515/tl-2013-0001Search in Google Scholar

Kehler, Andrew & Hannah Rohde. 2019. Prominence and coherence in a Bayesian theory of pronoun interpretation. Journal of Pragmatics 154. 63–78.10.1016/j.pragma.2018.04.006Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Hyunwoo & Eunjin Chun. 2023. Effects of topicality in the interpretation of implicit consequentiality: Evidence from offline and online referential processing in Korean. Linguistics 61(1). 77–105.10.1515/ling-2020-0197Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff & Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. Lmertest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82(13). 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.Search in Google Scholar

Kwon, Nayoung & Patrick Sturt. 2013. Null pronominal (pro) resolution in Korean, a discourse-oriented language. Language and Cognitive Processes 28(3). 377–387.10.1080/01690965.2011.645314Search in Google Scholar

Matuschek, Hannes, Reinhold Kliegl, Shravan Vasishth, Harald Baayen & Bates Douglas. 2017. Balancing type I error and power in linear mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language 94. 305–315.10.1016/j.jml.2017.01.001Search in Google Scholar

McKoon, Gail, Steven B. Greene & Roger Ratcliff. 1993. Discourse models, pronoun resolution, and the implicit causality of verbs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 19(5). 1040–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.5.1040.Search in Google Scholar

Pickering, Martin J. & Asifa Majid. 2007. What are implicit causality and consequentiality? Language and Cognitive Processes 22(5). 780–788.10.1080/01690960601119876Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Rohde, Hannah & Andrew Kehler. 2013. Grammatical and information-structural influences on pronoun production. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 29(8). 912–927.10.1080/01690965.2013.854918Search in Google Scholar

Rohde, Hannah, Andrew Kehler & Jeffrey L. Elman. 2006. Event structure and discourse coherence biases in pronoun interpretation. In Ron Sun (ed.), Proceedings of the 28th annual conference of the cognitive science society, 617–622. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Shoji, Shinichi, Stanley Dubinsky & Amit Almor. 2017. The repeated name penalty, the overt pronoun penalty, and topic in Japanese. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 46(1). 89–106.10.1007/s10936-016-9424-4Search in Google Scholar

Smyth, Ron. 1994. Grammatical determinants of ambiguous pronoun resolution. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 23(3). 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02139085.Search in Google Scholar

Stevenson, Rosemary J., A. Crawley Rosalind & David Kleinman. 1994. Thematic roles, focus and the representation of events. Language and Cognitive Processes 9(4). 519–548.10.1080/01690969408402130Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, Andrew J., Martin J. Pickering & Anthony J. Sanford. 1998. Implicity consequentiality. In Ann Gernsbacher Morton & Sharon J. Derry (eds.), Proceedings of the twentieth annual conference of the cognitive science society, 1031–1036. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.10.4324/9781315782416-186Search in Google Scholar

Ueno, Mieko & Andrew Kehler. 2016. Grammatical and pragmatic factors in the interpretation of Japanese null and overt pronouns. Linguistics 54(6). 1165–1221.10.1515/ling-2016-0027Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Chin Lung, Peter C. Gordon, Randall Hendrick & Jei Tun Wu. 1999. Comprehension of referring expressions in Chinese. Language and Cognitive Processes 14(5–6). 715–743.10.1080/016909699386248Search in Google Scholar

Zehr, Jeremy & Florian Schwarz. 2018. Penncontroller for internet based experiments (IBEX). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MD832.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2025-0065).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2025

- Research Articles

- Vowel formant track normalization using discrete cosine transform coefficients

- Asymmetry in French speech-in-noise perception: the effects of native dialect and cross-dialectal exposure

- Direct pseudo-partitives in US English

- A baseline for object clitic climbing in Italian

- Semantic granularity in derivation

- Shared processing strategies as a mechanism for contact-induced change in flexible constituent order

- The (non)canonical status of the ka- passive in Balinese

- A comparative study of 时 si 2 /shi 2 in Meixian Hakka and Ancient Chinese using the Minimalist Program

- A quantitative method for syntactic gradience: words, phrases, and the constructions in between

- Yeah, but how? Operationalizing the functions of the discourse-pragmatic marker yeah

- Hotspots for acoustic politeness in Korean and Japanese deferential speech

- How fast is fast and how slow is slow in mental simulation? Two rating studies on Estonian speed adverbs

- Discourse effects in processing Chinese reflexive pronouns

- Attitudinal negotiation: the analysis of online commentary videos about an international event on Chinese social media platform bilibili.com

- Crosslinguistic constructions and strategies: where do concessive conditionals fit in?

- Recurring patterns in tone (chain) shift

- Null pronoun interpretation probed via thematic role ambiguity: a case in Korean

- Experimental investigation on quantifier scope in Chinese relative clauses

- Sensitivity to honorific agreement: a window into predictive processing

- The negative concord illusion: an acceptability study with Czech neg-words

- Expletive negation in Italian temporal clauses: an acceptability judgement and a self-paced reading study

- Effects of information structure on pronoun resolution: the number of pronouns matters

- The cognitive processing of nouns and verbs in second language reading: an eye-tracking study

- Comprehension of conversational implicatures in L3 Mandarin

- Effects of crosslinguistic influence in definiteness acquisition: comparing HL-English and HL-Russian bilingual children acquiring Hebrew

- Multimodal language processing in school-aged Mandarin-speaking children: the role of beat gesture in enhancing memory for discourse information

- My Memoji, my self: prosodic correlates of online performed code-switching via avatar

- Gender effects in Mandarin creaky voice evaluation: a matched-guise study

- Narrating the doctoral journey on Chinese social media: chronotopes and scales in user interaction on Xiaohongshu

- Salient Language in Context (SLIC): a web app for collecting real-time attention data in response to audio samples

- Children’s emerging sociolinguistic expectations around social roles: a triangulated approach

- Situating speakers in change: a methodology for quantifying degree and direction of change over the lifespan

- Testing the effect of speech separation on vowel formant estimates

- Researching dialects with high school students: a citizen science approach

- Sociolinguistic research projects as brands

- Do readers perceive various types of knowledge expressed through evidentials in news reports with different degrees of certainty?

- Quantitative relationship between distribution of sentence length and dependency distance in Spanish

- Large corpora and large language models: a replicable method for automating grammatical annotation

- Using ATLAS.ti for constructing and analysing multimodal social media corpora

- Exploring the effect of semantic diversity on boundary permeability in verb/noun heterosemy using deep contextualized word embedding

- Communicative pressures influence the use of adverbs as well as adjectives: evidence from a crosslinguistic investigation

- Non-signers favor two-handed gestures when expressing inherently plural meanings

- Encoding Chinese metaphorical motion: a typological perspective

- Frequency does not predict the processing speed of multi-morpheme sequences in Japanese

- Did he lead monologues or did he talk to himself? How typological distance between source and target language influences the preservation of metaphorical mappings in translation

- How long is too long? Production-internal and communicative constraints in the coding of conditionality in Spanish

- Long English objects and short Chinese objects: language diversity shaped by cognitive universality

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2025

- Research Articles

- Vowel formant track normalization using discrete cosine transform coefficients

- Asymmetry in French speech-in-noise perception: the effects of native dialect and cross-dialectal exposure

- Direct pseudo-partitives in US English

- A baseline for object clitic climbing in Italian

- Semantic granularity in derivation

- Shared processing strategies as a mechanism for contact-induced change in flexible constituent order

- The (non)canonical status of the ka- passive in Balinese

- A comparative study of 时 si 2 /shi 2 in Meixian Hakka and Ancient Chinese using the Minimalist Program

- A quantitative method for syntactic gradience: words, phrases, and the constructions in between

- Yeah, but how? Operationalizing the functions of the discourse-pragmatic marker yeah

- Hotspots for acoustic politeness in Korean and Japanese deferential speech

- How fast is fast and how slow is slow in mental simulation? Two rating studies on Estonian speed adverbs

- Discourse effects in processing Chinese reflexive pronouns

- Attitudinal negotiation: the analysis of online commentary videos about an international event on Chinese social media platform bilibili.com

- Crosslinguistic constructions and strategies: where do concessive conditionals fit in?

- Recurring patterns in tone (chain) shift

- Null pronoun interpretation probed via thematic role ambiguity: a case in Korean

- Experimental investigation on quantifier scope in Chinese relative clauses

- Sensitivity to honorific agreement: a window into predictive processing

- The negative concord illusion: an acceptability study with Czech neg-words

- Expletive negation in Italian temporal clauses: an acceptability judgement and a self-paced reading study

- Effects of information structure on pronoun resolution: the number of pronouns matters

- The cognitive processing of nouns and verbs in second language reading: an eye-tracking study

- Comprehension of conversational implicatures in L3 Mandarin

- Effects of crosslinguistic influence in definiteness acquisition: comparing HL-English and HL-Russian bilingual children acquiring Hebrew

- Multimodal language processing in school-aged Mandarin-speaking children: the role of beat gesture in enhancing memory for discourse information

- My Memoji, my self: prosodic correlates of online performed code-switching via avatar

- Gender effects in Mandarin creaky voice evaluation: a matched-guise study

- Narrating the doctoral journey on Chinese social media: chronotopes and scales in user interaction on Xiaohongshu

- Salient Language in Context (SLIC): a web app for collecting real-time attention data in response to audio samples

- Children’s emerging sociolinguistic expectations around social roles: a triangulated approach

- Situating speakers in change: a methodology for quantifying degree and direction of change over the lifespan

- Testing the effect of speech separation on vowel formant estimates

- Researching dialects with high school students: a citizen science approach

- Sociolinguistic research projects as brands

- Do readers perceive various types of knowledge expressed through evidentials in news reports with different degrees of certainty?

- Quantitative relationship between distribution of sentence length and dependency distance in Spanish

- Large corpora and large language models: a replicable method for automating grammatical annotation

- Using ATLAS.ti for constructing and analysing multimodal social media corpora

- Exploring the effect of semantic diversity on boundary permeability in verb/noun heterosemy using deep contextualized word embedding

- Communicative pressures influence the use of adverbs as well as adjectives: evidence from a crosslinguistic investigation

- Non-signers favor two-handed gestures when expressing inherently plural meanings

- Encoding Chinese metaphorical motion: a typological perspective

- Frequency does not predict the processing speed of multi-morpheme sequences in Japanese

- Did he lead monologues or did he talk to himself? How typological distance between source and target language influences the preservation of metaphorical mappings in translation

- How long is too long? Production-internal and communicative constraints in the coding of conditionality in Spanish

- Long English objects and short Chinese objects: language diversity shaped by cognitive universality

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations