Abstract

2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites with different curing degrees were prepared by different curing temperatures and curing times. The effects of curing degree on the flexural strength and thermal properties of the composites were investigated by mechanical properties test, scanning electron microscope (SEM) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The results show that the flexural strength increases to the increase in the degree of cure, but the rate of increase is non-linear. When the degree of cure is higher than 90%, the flexural strength of the composite is more than 300 MPa and the bending failure mechanism of the composite is analyzed by SEM. The TG test showed that the degree of cure had little effect on the residual weight of the composite at 1000°C, but had a greater effect on the temperature of the previous weight loss.

1 Introduction

Multidimensional woven fiber reinforced composites has many advantages over traditional two-dimensional (2D) fiber reinforced composites, such as excellent inter laminar shear resistance and excellent integrity. However, three-dimensional (3D) woven fibers have the disadvantages of complicated production process and high production cost. The appearance of 2.5D woven technology has greatly improved the shortcomings of 3D woven, while retaining the advantages of multidimensional woven fibers (1, 2, 3, 4). Quartz fiber has good high temperature resistance, long-term use temperature up to 1200°C, and has good mechanical properties and permeability (5). Boron phenolic resin is a resin matrix commonly used for high temperature and ablation resistant composites (6,7). Therefore, the 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin matrix composite has excellent mechanical properties, especially resistance to interlayer shear, excellent high temperature resistance and ablation resistance, it is an advanced composite material used in high-end equipment such as launch vehicles, missiles, and aircraft. Yong Liu (8) studied the mechanical properties and microstructure of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced silica composites, and concluded that the shear stress-displacement curve of composites changes nonlinearly and the composites show good toughness in the radial direction. Qing Wang (9) studied the effect of ZrO2 coating from the mechanical properties of 2.5D SiC fiber reinforced SiO2 composites, the results show that the flexural strength of ZrO2 coated SiC fiber reinforced SiO2 composites is about twice that of uncoated composites, the strength of the composite tested at 1200°C increased by about 12% compared to the strength of the sample tested at room temperature.

The curing degree of the resin has a very large effect on the properties of the composite (10, 11, 12, 13). In general, the greater the degree of cure of the resin, the better the properties of the composite (14, 15, 16). However, in the actual production of composite materials, due to raw materials, curing processes, molds and other factors, the curing degree of composite materials often does not reach a higher level, or if the curing degree is to reach a certain higher value, it will cost more time and energy. In this paper, the boron phenolic resin was used as the matrix and 2.5D quartz fiber was used as the reinforcing material to prepare 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composite and studying the effect of curing degree on its mechanical properties and thermal properties.

2 Experimental details

2.1 Experimental materials

Thermoset phenolic resin was purchased from Shanxi Taihang Fire Resistant Polymer Company (China) and more details on the resin are shown in Table 1. 2.5D quartz fiber braid, C type, (the single layer thickness is 2 mm and the woven structure is shallow cross-linking; the fiber volume content is 38%) produced by Hubei Jingzhou Feilihua Quartz Glass Company (China). Acetone(AR) was supplied by Sinopharm Reagent Company (China). Absolute ethanol(AR) was supplied by Sinopharm Reagent Company (China).

Compositions of boron phenolic resin.

| Component | resin | phenol | phenol derivative | free aldehyde | others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass fraction (wt%) | 92.29 | 4.21 | 2.07 | 0.87 | 0.56 |

2.2 Preparation of composite materials

First, the 2.5D quartz fiber was dried at 80°C for 5 h using a vacuum drying oven, and the powdered boron phenolic resin was dissolved using absolute ethanol. The 2.5D quartz fiber was cut to a suitable size, and the mass ratio of the boron phenolic resin to the 2.5D quartz fiber was calculated based on the fiber mass, the fiber volume content, and weighing dissolved boron phenolic resin. Next, the weighed boron phenolic resin was uniformly impregnated with 2.5D quartz fiber by a wet hand lay-up process, and then the solvent was removed in a vacuum drying oven to obtain a 2.5D quartz fiber-boron phenolic resin prepreg. Cut the prepreg to fit the size of the mold and cure it under different curing parameters to obtain a 2.5D quartz fiber-boron phenolic resin composite material with different degrees of cure. Numbering composite samples, from CM-A1 to CM-C4, as shown in Table 2. Figure 1 is a picture of the cured 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composite sample.

Pictures of the cured 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composite sample.

Curing parameters of composite samples.

| Samples | Curing temperature (°C) | Holding time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| CM-A1 | 130 | 30 |

| CM-A2 | 60 | |

| CM-A3 | 120 | |

| CM-A4 | 180 | |

| CM-B1 | 150 | 30 |

| CM-B2 | 60 | |

| CM-B3 | 120 | |

| CM-B4 | 180 | |

| CM-C1 | 30 | |

| CM-C2 | 180 | 60 |

| CM-C3 | 120 | |

| CM-C4 | 180 |

2.3 Material testing and performance characterization

The curing degree of the composite material was measured by solvent the extraction method. The part

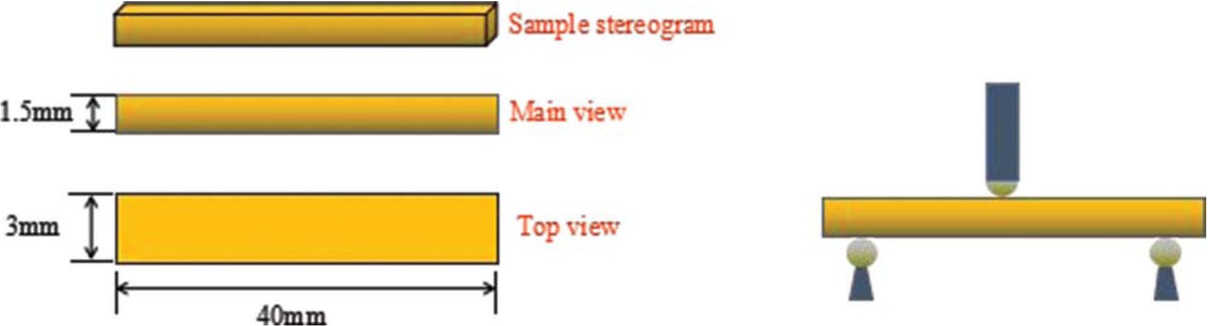

of the composite material close to the measured resin content was selected. The sample was processed into a powder sample by a trowel, and the powder sample was sieved through a 0.4 mm standard sieve to obtain a powder sample to be determined. Then, the powder samples are extracted from acetone, and the extracted sample was subjected to suction filtration and drying treatment. The finally the curing degree of the composite material was calculated by weighing. The flexural strength of the composites with different degrees of cure was tested for a mechanical testing machine using a “three-point bending method” with a loading rate of 2 mm/min, the sample size and test schematic shown in Figure 2. The cross section of the composite was observed using scanning electron microscopy (JSM-IT300 model of Japan Electronics Co., Ltd., sample size is less than 20 mm × 20 mm, Pt treatment on the surface of the sample, Secondary electron imaging and the exposure time is 20 s, the vacuum degree reaches 10-6 Pa), and the bending failure mechanism of the composite was analyzed. The thermal performance of the composite material was tested by a high temperature TG-DSC thermal analyzer from NETZSCH, Germany. The heating rate was 10.0°C/min, and the temperature range was 25°C to 1000°C in a nitrogen atmosphere.

The size of the curved sample and schematic diagram of the flexural test.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Curing degree and flexural strength of 2.5D quartz fiber-boron phenolic resin composite

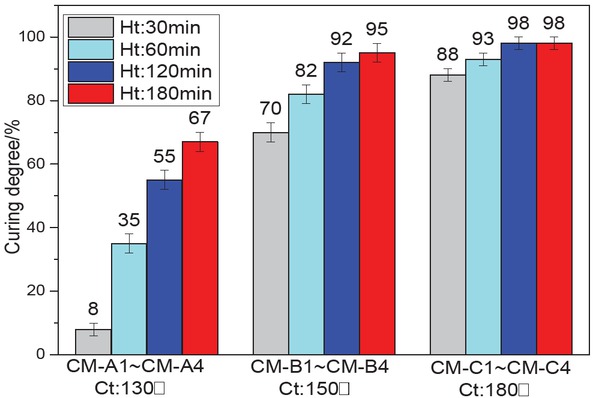

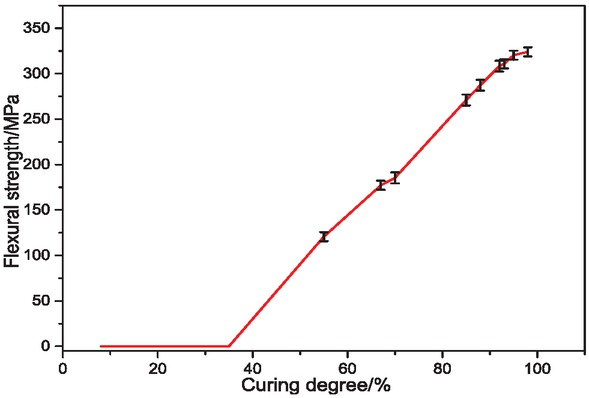

The Figure 3 shows the change in the curing degree of the sample under different curing processes, and the Figure 4 shows the bending strength of the sample at different degrees of cure. As shown in Figure 3, the Ct (curing temperature) and the Ht (holding time) have an effect on the curing degree, The curing degree of sample increases with the increase of Ct or Ht, but the degree of influence is different. When the Ht is the same, it is clear that the higher the Ct, the higher the curing degree of the sample, The overall curing degree of Samples CM-A1~CM-A4 is significantly lower than that of Samples CM-C1~CM-C4, the curing degree of CM-A4 is 67%, which is 46% lower than the CM-C4 with 98% curing degree, the sample CM-C1 with a curing temperature of 180°C can achieve 88% cure even in the shortest holding time. Therefore, the Ct contributes more to the curing degree, but from another point of view, the ideal curing degree can be achieved by extending the holding time at a lower temperature. As can be seen from Figure 4, the bending strength of the sample increases as the degree of cure increases, but this trend is not linear. The curing degree of the composite material increased in 70% to 92%, the flexural strength reached 310.56 MPa from 185.34 MPa, the flexural strength improvement rate of the material is 67%, and the curing degree was from 85% to 95%, and the flexural strength was from 271.08 MPa to 320.32 MPa, the rate is 18%. When the curing degree of the composite material reaches 90% or higher, the flexural strength of the composite material exceeds 300 MPa, and the flexural strength differs little in this range (17). Therefore, when the curing degree reaches a certain value, the flexural strength of the sample does not rise significantly as the curing degree increases.

Curing degree of different curing processes (Ht – Holding time, Ct – curing temperature).

Flexural strength of different curing degree.

3.2 Analysis of sectional micromorphology and flexural failure mechanism of composites

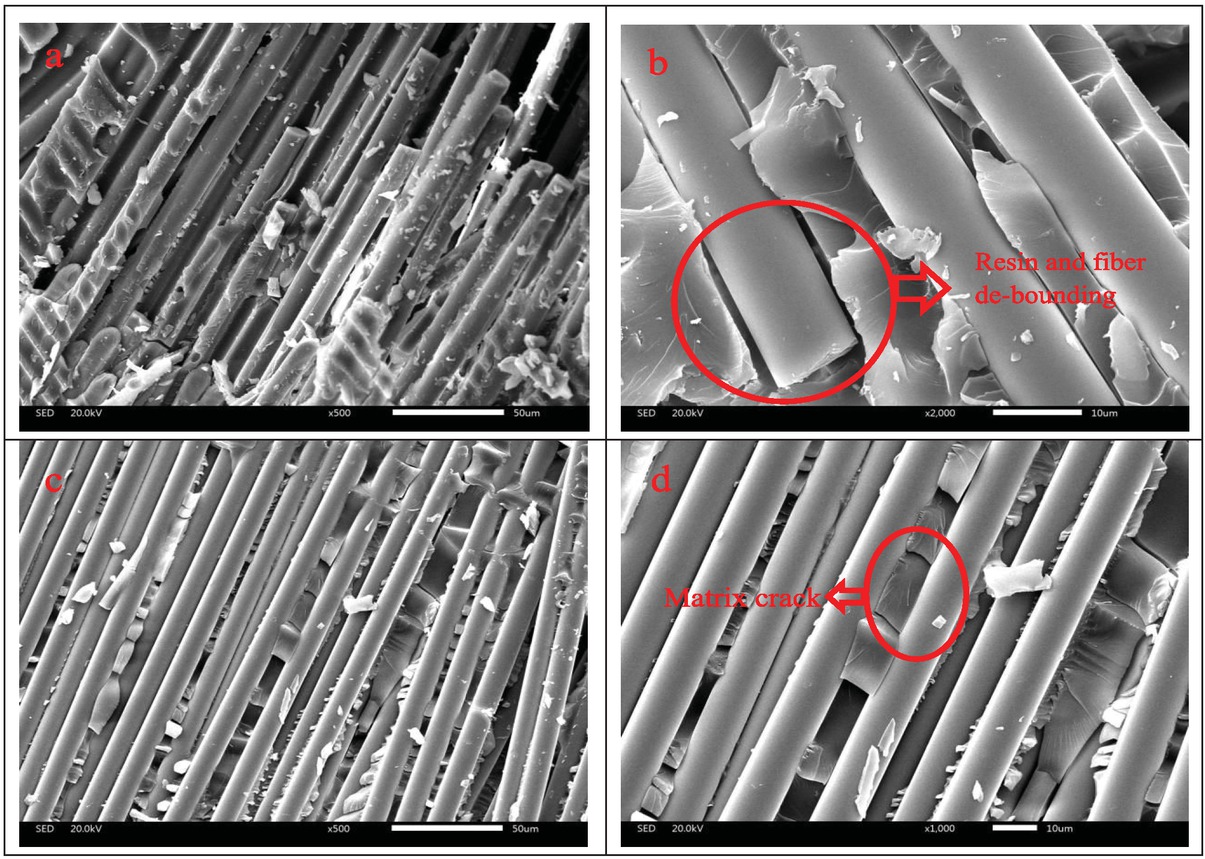

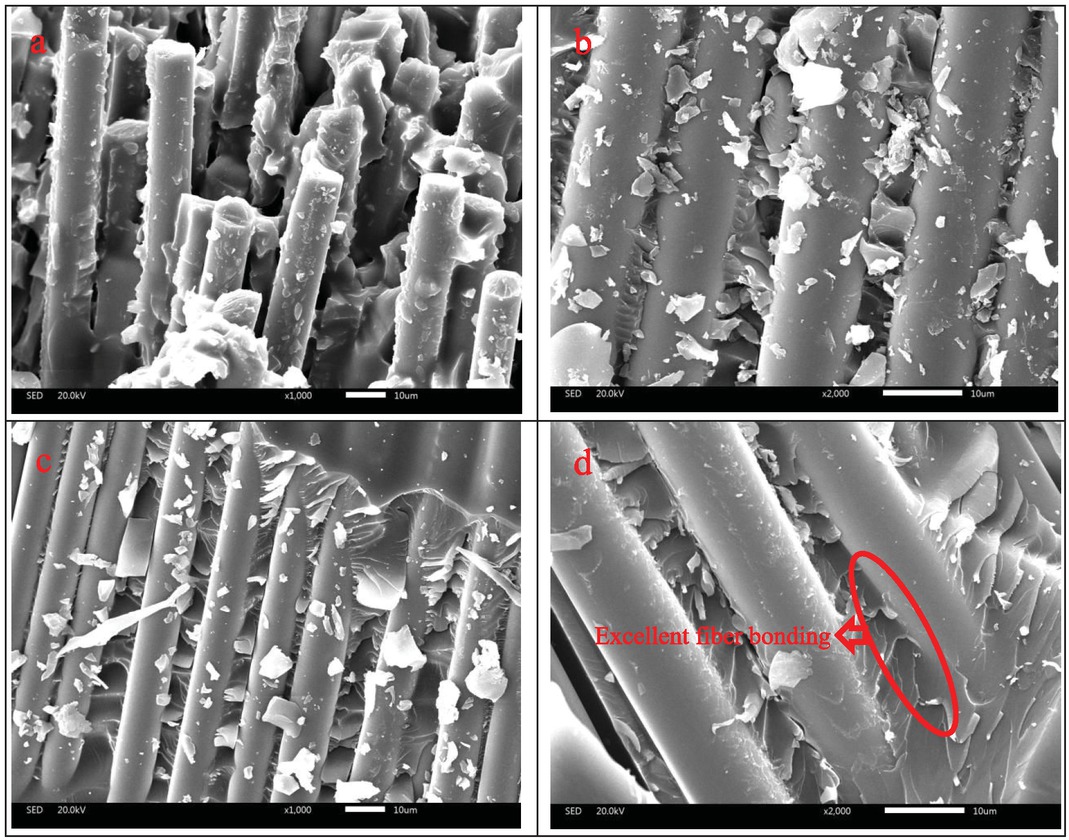

In order to analyze the effect of curing degree on the micro-morphology of bending failure of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composites and the flexural failure mechanism of composites, scanning electron microscopy analysis was performed on the curved section of CM-B1 with curing degree of 70% and CM-C3 with curing degree of 98%, the resulting SEM images are shown in Figures 5 and 6. It can be seen from the SEM image that the fiber surface on the curved section of the sample CM-B1 is relatively smooth, almost no resin matrix is attached, and the resin and fiber de-bounding, as shown in Figure 5b

SEM image of CM-B1 bending failure.

SEM image of CM-C3 bending failure.

In contrast, the surface of the fiber on the cross section of the sample CM-C3 was rough, as shown in Figure 6, and the resin was attached to the surface of the fiber, and the fiber and the resin did not separate. It can be seen from Figure 5d that the resin between the fibers has cracks of different sizes and even cracks, but in Figure 6d the resin matrix is well attached to the surface of the fibers and the interface remains intact. This shows that the degree of cure will affect the interface properties of the composite. The reason for these occurrences is that when the resin is not cured enough, the resin strength is low, cracks or even cracks are easily caused by bending and compression, and the interface strength between the resin and the fiber is low, thereby affecting the bending strength of the composite. When the degree of curing of the resin is high, the degree of cross-linking of the resin is high, the resin strength is high, and the interface property between the resin and the fiber is good. When the composite material is subjected to bending and compression, the resin can effectively transmit load and distribute load. It can also be seen from the two SEM images that, regardless of the degree of curing, most of the fibers are intact after the sample is subjected to bending failure, and few fibers are single or single-strand broken, which shows that the 2.5D structure have excellent Integrity.

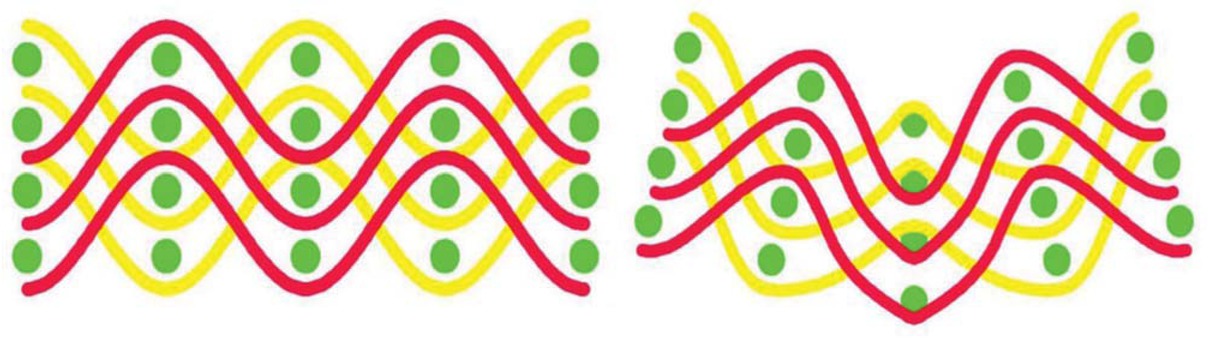

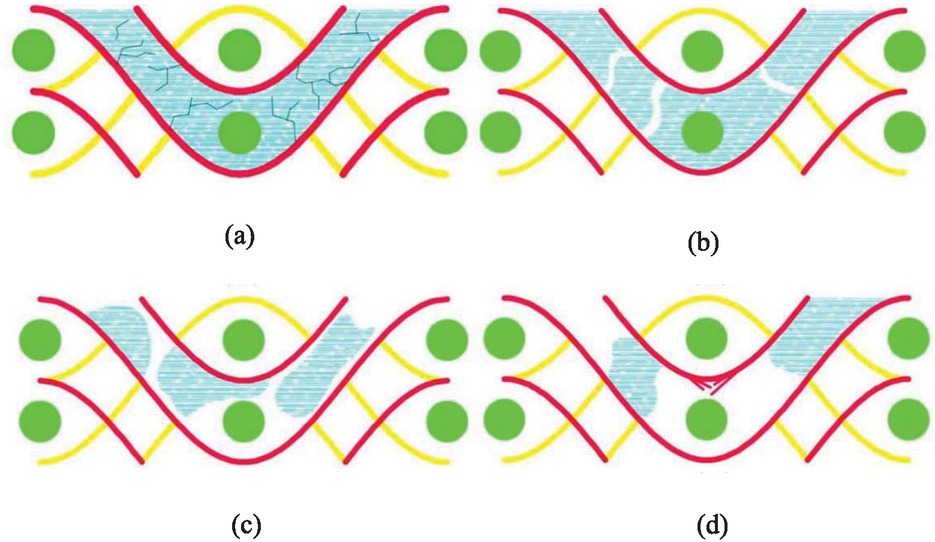

Therefore, it can be inferred that the macroscopic change of the 2.5D fiber reinforced composite material under bending to load may be as shown in Figure 7. Figure 4a shows the state of the fiber when the composite material are not subjected to load, and Figure 4b is the state of the fiber when the composite is under load. Since the warp yarn is not in a fully stretched state in the structure of the 2.5D fiber, but is bent through several layers of weft yarns, the tension is less. Therefore, when the composite material are subjected to a load, it can be deformed by the fibers, so that the load applied to the surface perpendicular to the composite material is distributed over the warp yarns of the respective layers, and the warp yarns are deformed to resist the load. From the above analysis, it can be inferred that the composite material may have several failure mechanisms (18,19) as shown in Figure 8. When the 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composite material is subjected to a bending load, if the curing degree of the composite material is not high, it is likely that the resin matrix is cracked or even broken, as shown in Figures 8a and 8b As the load continues to increase, the deformation of the composite increases. Due to the poor interfacial properties of the resin matrix and the fiber, the deformation between the fiber and the resin under bending to load is inconsistent, and the resin may gradually peel off from the fiber, as shown in Figure 8c The damaged resin remains between the fibers, but the protective fiber has been lost, and the fiber is easily broken, as shown in Figure 8d When the composite has a high curing degree, the composite tends to be brittle when subjected to a bending load, that is, it is more likely that the fiber breaks together with the matrix.

Form of 2.5D structural fiber: (a) composite material is not loaded; (b) composite material subjected to bending load.

Fiber and resin state when composite material is subjected to bending load: (a) crack in the resin matrix; (b) resin matrix fracture; (c) resin and fiber stripping; (d) fiber and resin break.

3.3 Thermal properties of composite materials

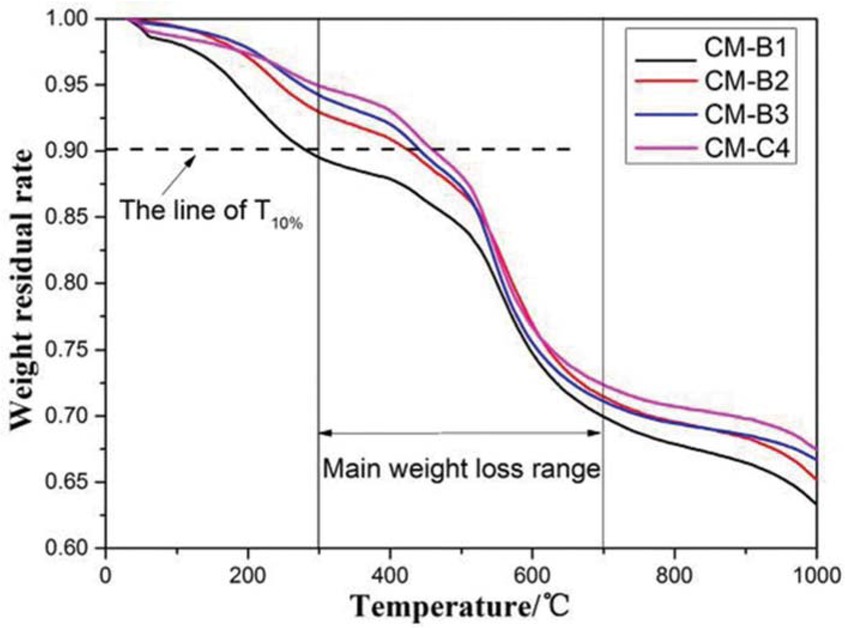

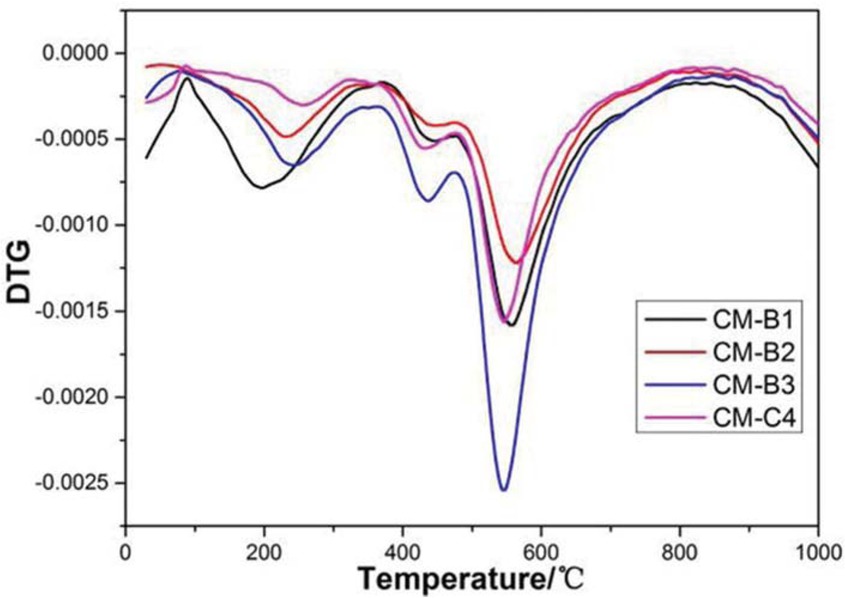

The TG curves and the DTG curves of the composite samples CM-B1, CM-B2, CM-B3 and CM-C4 are shown in Figures 9 and 10, the thermal decomposition parameters of the composite can be obtained from the TG data, as shown in the Table 3. In order to eliminate the error caused by the difference in fiber content of each sample, the figures and the table data do not contain the weight of the fiber. It can be seen from Figure 9 that the thermal weight loss of the composite sample mainly occurs to the range of 300°C~700°C, at this stage the composite resin matrix cracking reaction, the weight is rapidly reduced. However, the weight loss of composite materials with different curing degree is different. It can be seen from the data onto Table 3 that the temperature T10% of 10% weight loss moves toward high temperature as the curing degree increases, the CM-B1 loses 10% of its temperature at 283.3°C, while the CM-C4 loses 10% of its temperature at 461.2°C, the curing degree differs by less than 30%, while T10% differs by 180°C. The reason is that the composite resin matrix with low curing degree contains a large amount of resin which does not undergo cross-linking reaction. During heating, these

TG curve for composites.

DTG curve for composites.

Thermal decomposition parameters of composites.

| Sample | Curing degree (%) | T10% (°C) | Maximum degradation temperature (°C) | Residue weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM-B1 | 70 | 283.3 | 563.8 | 63.29 |

| CM-B2 | 85 | 427.3 | 555.3 | 65.14 |

| CM-B3 | 92 | 442.7 | 545.5 | 66.67 |

| CM-C4 | 98 | 461.2 | 553.4 | 67.44 |

resins begin to undergo cross-linking reaction, and the reaction produces volatile small molecules, which reduces the weight. In addition, when the temperature reaches the decomposition temperature of the resin, the two reactions work together to make the T10% of the composite material lower. As the degree of cure increases, the former reaction becomes weaker and weaker, so that T10% moves to a high temperature as the curing degree increases. The residual weight of the composite at 1000°C is similar to T10%, the difference is that the residual weight of each composite sample is not much different at 1000°C, and 70% curing degree and 98% curing degree composite material only differs by 3% at 1000°C residual weight.

4 Conclusions

Curing temperature and holding time have a great influence on the curing degree of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composite. The higher the curing temperature, the faster the curing degree of the composite increases; however the curing degree can be achieved by extending the holding time at a lower curing temperature. The improvement of the curing degree is beneficial to the bending property of the composite. When the curing degree is higher than 90%, the rate of change of the bending strength is small, and the bending strength is higher than 300 MPa.

The SEM results show that the increase of curing degree can improve the interface properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composites. When the composite material with a low curing degree is subjected to a bending load, the matrix is cracked or broken, then the resin matrix is peeled off from the fibers, and finally the fibers are broken.

The TG test showed that the degree of cure had a great influence on the pre-weightless temperature T10% of the 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic resin composite. The higher the curing degree is, the better the increase of T10%; however when the degree of cure is higher than 90%, the increase of T10% is not obvious. The degree of curing has little effect on the residual weight of the material at 1000°C. The residual weight of 70% curing degree and 98% curing degree differs only by 3% at 1000°C.

References

1 Deng X., Chawla N., Three-dimensional (3D) modeling of the thermoelastic behavior of woven glass fiber-reinforced resin matrix composites. J. Mater. Sci., 2008, 43(19), 6468-6472.10.1007/s10853-008-2982-6Suche in Google Scholar

2 Xue-Wei X.U., Jiao Y.N., Ying S., Impact properties of multidimensional multi-directional textile composites. J. Tianjin Polytechnic Univ., 2014, 33(1), 1-4.Suche in Google Scholar

3 Hu X., Sun Z., Yang F., Fatigue Hysteresis Behavior of 2.5D Woven C/SiC Composites: Theory and Experiments. Appl. Compos. Mater., 2017, 24(6), 1-17.10.1007/s10443-017-9591-ySuche in Google Scholar

4 Jiao Y.N., Qiu P.X., Gao-Ning J.I., Mechanical properties of 2.5D woven composites with different volume rates in warp and weft directions. J. Tianjin Polytechnic Univ., 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

5 Gooch J.W., Quartz Fiber. Springer, New York, 2011.10.1007/978-1-4419-6247-8_9687Suche in Google Scholar

6 Zhang Y., Cao J., Wang D., Synthesis of Boron Modified Phenolic Resin. Chin. J. Syn. Chem., 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

7 Yan L.S., Yao D.M., Yang X.J., Study on Boron-Phenolic Resin Ablative Materials. J. Solid Rocket Technol., 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

8 Liu Y., Zhu J., Chen Z., Mechanical properties and microstructure of 2.5D (shallow straight-joint) quartz fibers-reinforced silica composites by silicasol-infiltration-sintering. Ceram. Int., 2012, 38(1), 795-800.10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.08.006Suche in Google Scholar

9 Wang Q., Cao F., Xiang Y., Effects of ZrO2 coating on the strength improvement of 2.5D SiC f /SiO2 composites. Ceram. Int., 2017, 43(1), 884-889.10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.09.164Suche in Google Scholar

10 Wachsman E.D., Frank C.W., Effect of cure history on the morphology of polyimide: Fluorescence spectroscopy as a method for determining the degree of cure. Polymer, 1988, 29(7), 1191-1197.10.1016/0032-3861(88)90043-2Suche in Google Scholar

11 Uddin M.A., Alam M.O., Chan Y.C., Adhesion strength and contact resistance of flip chip on flex packages-effect of curing degree of anisotropic conductive film. Microelectron. Reliab., 2004, 44(3), 505-514.10.1016/S0026-2714(03)00185-9Suche in Google Scholar

12 Montserrat S., Flaqué C., Pagès P., Effect of the crosslinking degree on curing kinetics of an epoxy–anhydride system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2010, 56(11), 1413-1421.10.1002/app.1995.070561104Suche in Google Scholar

13 Labronici M., Ishida H., Effect of degree of cure and fiber content on the mechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced PMR‐15 polyimide composites. Polym. Composite., 2010, 20(4), 515-523.10.1002/pc.10375Suche in Google Scholar

14 Maas T.A.M.M., Optimalization of processing conditions for thermosetting polymers by determination of the degree of curing with a differential scanning calorimeter. Polym. Eng. Sci., 2010, 18(1), 29-32.10.1002/pen.760180106Suche in Google Scholar

15 Heba F., Mouzali M., Abadie M.J.M., Effect of the crosslinking degree on curing kinetics of an epoxy–acid copolymer system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2010, 90(10), 2834-2839.10.1002/app.12991Suche in Google Scholar

16 So S., Rudin A., Effects of resin and curing parameters on the degree of cure of resole phenolic resins and woodflour composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2010, 40(11-12), 2135-2149.10.1002/app.1990.070401126Suche in Google Scholar

17 Li S.S., Chen L., Jiao Y.N., Experimental Research on Bending Behavior of 2.5D Woven Fabrics. Adv. Mater. Res., 2011, 152-153, 254-258.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.152-153.254Suche in Google Scholar

18 Song J., Wen W., Cui H., Finite Element Analysis of 2.5D Woven Composites, Part II: Damage Behavior Simulation and Strength Prediction. Appl. Compos. Mater., 2015, 23(1), 1-25.10.1007/s10443-015-9449-0Suche in Google Scholar

19 Zhong S., Guo L., Liu G., A continuum damage model for three-dimensional woven composites and finite element implementation. Compos. Struct., 2015, 128, 1-9.10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.03.030Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Fu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die