Abstract

The Egyptian cobra is among the deadliest snake species, capable of causing death within a short span of 15 min. Also, every snake species has its own anti-venom type. So, a quick identifying the Egyptian Cobra bite from other snake species is a challenging and critical task. This research employs Internet of things (IoT) and deep learning methods to precisely recognize bites of Egyptian cobra, in the real-time, by analyzing images of the bite marks. We deploy IoT-enabled wearable devices equipped with sensors capable of detecting snake bites, whereas these sensors measure changes in physiological parameters indicative of a snakebite, such as heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature sensors based on our proposed mathematical algorithm. Also, we present a real case study in which we used our mathematical algorithm to determine based on its sensor readings whether the victim was exposed to a snake bite or not in the real-time. These wearable devices can be worn by individuals working or living in areas prone to snake encounters, such as farmers. When a snake bite occurs, the IoT sensors embedded in the wearable devices will immediately detect the bite and transmit real-time data, including vital information about the bite marks, to a central monitoring system or victim relative. Also, we assembled a dataset consisting of 500 images depicting Egyptian cobra bites and 600 images of bites from various other snake species indigenous to Egypt. To bolster the model’s trustworthiness and facilitate understanding of its decisions, we employed the contemporary method of explainable deep learning. Also, notably, our methodology yielded an accuracy of 90.9%.

1 Introduction

Snake bites pose a significant public health concern, with millions of individuals affected annually, as reported by the World Health Organization. These incidents result in numerous cases of poisoning, fatalities, and instances of amputation and paralysis. In Egypt, the “Egyptian cobra” stands out as one of the most poisonous snakes, capable of causing swift fatality within minutes for humans and a few hours for elephants [1,2]. The danger of Egyptian cobras is further heightened by their tendency to inhabit areas near human dwellings, as they prey on domestic fowl like chickens, thus increasing the risk to the local population. Prompt identification of the attacking snake species is crucial in snake bite cases to administer the appropriate antitoxin treatment. However, medical professionals often resort to administering polyvalent anti-venom without accurate knowledge of the specific snake species responsible. Even when patients offer visual descriptions of the snake, healthcare professionals might not possess the specialized knowledge to pinpoint the exact species solely relying on these descriptions. Additionally, snake bite victims are often unable to provide detailed observations due to their limited awareness of snake features. Using polyvalent anti-venom, which contains antibodies against multiple snake species, carries potential risks. While it can neutralize the venom of some snakes, the un-neutralized components of the polyvalent anti-venom that remain can present additional health risks [3].

Consequently, the accurate identification of the snake species is essential for delivering the right medical intervention, thus increasing the prospects of survival for individuals suffering from snake bites [4]. We also deploy Internet of things (IoT)-enabled wearable devices equipped with sensors capable of detecting snake bites. These wearable devices can be worn by individuals working or living in areas prone to snake encounters, such as farmers, field researchers, or residents in rural communities. Various sensors and technologies can aid in detecting snake bites or identifying the presence of venom. These include pressure sensors, temperature sensors, venom detection kits, electrochemical sensors, biosensors, smart wearables, and machine learning algorithms. Pressure sensors detect the force exerted by snake fangs, while temperature sensors identify local temperature changes caused by venom. Venom detection kits and electrochemical sensors detect venom in blood or tissue, while biosensors use biological components to detect venom toxins. Smart wearables equipped with sensors can detect sudden changes indicative of a snake bite, and machine learning algorithms can recognize patterns associated with envenomation. By combining these technologies, detection systems can be more accurate and reliable, potentially improving outcomes for snake bite victims, though prompt medical treatment remains critical. When a snake bite occurs, the IoT sensors embedded in the wearable devices will immediately detect the bite, based on the high change in the blood pressure, heart rate, and other specific and transmit real-time data, including vital information about the bite marks, to a central monitoring system or victim relative. By leveraging IoT technology, we aim to provide rapid and reliable snake bite identification, enabling prompt medical intervention and potentially saving lives. Additionally, the real-time nature of IoT data transmission will facilitate faster response times and more efficient allocation of medical resources in snake bite emergencies.

There are notable advancements through machine learning for snake classification [5,6,7]. Although identifying snake species manually based on visual cues such as head shape, body texture, skin color, and eye characteristics poses a considerable challenge for those lacking expertise, recent research has shown promise in automating this process [8]. For instance, a study utilized a convolutional neural network (CNN) to develop a classification system for five venomous snake species found in Indonesia. By training three CNN models on a dataset of 415 snake images, significant strides were made in accurately identifying these species [9]. The previously mentioned techniques are not feasible in real-life situations. After a person is bitten by a snake, they are unable to document the snake’s characteristics, and there is no time for the victim to capture an image. Therefore, our model showcases notable improvements in efficiency as it relies on bite marks that can be assessed at any point following the bite incident. Building on this foundation, our study aims to further improve the accuracy and reliability of snake species identification, thereby providing crucial assistance to individuals vulnerable to snake bites, whereas bite marks have been recognized as a common factor for identifying snake species [10]. Our research centers on the development of a deep learning model utilizing an extensive dataset that encompasses two distinct categories: bite marks caused by the Egyptian Cobra and those resulting from other snake species. Through the model’s training on this dataset, it becomes capable of distinguishing whether a given snake bite mark belongs to the Egyptian Cobra species or not. Our research aims to investigate the effectiveness of utilizing bite marks as a training material for achieving efficient snake species identification. One of the main obstacles when implementing deep learning solutions in healthcare is the lack of transparency in these models, which impedes a full comprehension of the underlying rationale behind machine-generated predictions. To tackle this issue and establish trust among healthcare professionals, we suggest employing an explainable artificial intelligence method known as Grad-CAM in our research. Through the utilization of Grad-CAM, our objective is to offer insights into the model’s decision-making process, thus improving its comprehensibility within the medical community. Our model demonstrates a commendable accuracy of 90%, which is considered highly efficient. However, it is important to acknowledge that a 10% error rate is common, even among human doctors. Our ongoing objective is to continually refine the model’s accuracy and strive for optimal performance over time, ensuring the highest possible level of accuracy in snake species identification.

Here, we can list the contributions of our proposed model as shown below:

We deploy IoT-enabled wearable devices equipped with sensors capable of detecting snake bites in real-time. By leveraging IoT technology, we aim to provide rapid and reliable snake bite identification, enabling prompt medical intervention and potentially saving lives.

We present a novel approach to recognizing the bite of the Egyptian Cobra based on the bite marks, whereas all previous works need an image or accurate description of the attacking snake, which is not practical in a real situation.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the existing literature in the field of snake species identification; the proposed classification model is discussed in Section 3; performance analyses are discussed in Section 4; Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Related work

We have undertaken a comprehensive review of previous models employed for snake species identification with the aim of assisting the millions of individuals who are vulnerable to snake bites, as shown in Figure 1. Our taxonomy categorizes these models based on user input, distinguishing between those that utilize textual representations of the attacking snake provided by the user and those that employ image data for classification purposes. While some studies focus solely on determining whether a snake is venomous or not, others delve further to identify the specific species. Additionally, certain models restrict their classification efforts to specific locations, whereas others adopt a more general approach. Smart machine learning methods, such as deep learning algorithms, have demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing the risks associated with snakes, which are among the leading causes of human fatalities [11]. In a previous study conducted in Malaysia, researchers compiled a dataset known as the “Snakes of Perlis Corpus,” which included images representing 22 distinct snake species. They applied intelligent techniques, including k-nearest neighbors and backpropagation neural networks, to achieve an accuracy of 87% in recognizing snake species [9]. Nevertheless, the manual identification of snake species based on visual features such as head shape, body texture, skin color, and eye characteristics remains a challenging task for individuals without expertise in the field. Another noteworthy study used a CNN to create a snake species classification system using images of five venomous snake species prevalent in Indonesia. Through the training of three CNN models on a dataset comprising 415 snake images, significant progress was made in accurately classifying snake species [9]. Our study builds upon the foundation established by these previous works, aiming to further enhance the accuracy and reliability of snake species identification, thus offering valuable support to individuals at risk of snake bites.

Categorization of snake-species recognition-based deep learning. Source: Proposed, created and drawn by the authors.

The previously mentioned techniques are not feasible in real-life situations. After a person is bitten by a snake, they are unable to document the snake’s characteristics, and there is no time for the victim to capture an image. Therefore, our model showcases notable improvements in efficiency as it relies on bite marks that can be assessed at any point following the bite incident. Furthermore, bite marks are recognized as a crucial factor in characterizing each snake species [8]. Diligent examination of the snake’s bite location can prove to be highly valuable in combination with the search.

The snakes in the Galápagos Islands represent a significantly understudied group among vertebrates in the region. Formal evaluation of the conservation status has only been conducted for four out of the nine recognized species, with indications suggesting the potential extinction of some species on certain islands. Furthermore, the reliability of reports from park rangers and citizen scientists regarding Galápagos snakes is dubious, given recent clarification in the systematics of these snakes. To address this issue, a previous work proposed the development and implementation of easily accessible applications for real-time species identification utilizing automatic object recognition technology. Through the utilization of deep learning algorithms trained on collected images of snake species, we have created an artificial intelligence platform, an application software, capable of identifying snake species from user-uploaded images. The process involves the algorithm processing the uploaded image, classifying it into one of the nine snake species, providing information on the predicted species, and educating users on aspects such as distribution, natural history, conservation, and etymology of the identified snake species [15]. Automatic snake classification involves the identification of snake species through image processing techniques. This system serves to mitigate fatalities resulting from snake bites by swiftly suggesting appropriate antivenom for victims. Previous endeavors in this field have relied on systems with smaller databases utilizing machine learning and older deep learning architectures. These systems exhibited limitations such as identifying only a limited number of snake species or lower accuracies. Nonetheless, there is room for enhancement to bolster the robustness of snake classification systems. The proposed system surpasses prior efforts by identifying 772 classes of snake species, employing a larger dataset, and utilizing the state-of-the-art deep learning architecture ResNeXt50-V2. An ensembled model is incorporated to further refine the system, resulting in an impressive accuracy of 85.7% and an F1-score of 0.68 [16].

Distinguishing between venomous and non-venomous snakes is essential as it can prevent the unnecessary administration of antivenin, which, in some cases, can lead to adverse effects, including potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions. It is worth noting that research papers focusing on location-based classification, which identify snake species unique to specific regions, tend to achieve higher accuracy compared to those attempting to classify all known snake species. This is due to the vast number of snake species (3,848 known species), making it a challenging task to compile a comprehensive dataset containing a substantial number of images for each species. We present a comparison among the reviewed papers and our proposal, as shown in Table 1.

Comparison of the discussed papers and our paper

| Reference | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| [9] | Obtaining an image of the attacking snake is often impractical |

| [6] | The model’s output may be insufficient and time-consuming in critical cases |

| [7] | The ultimate model relies on a visual description provided by the victim to predict the snake species. Nonetheless, this approach may not be practical |

| [13] | The user provides an image of the attacking snake to obtain classification. However, these images may not always provide clear descriptions of the snake |

| [18] | In many of these images, only parts of the snake may be visible |

| [19] | Relying solely on geographical distribution information in the recognition process is often insufficient |

| [20] | The fundamental difference between real-world situations and the samples used for model training |

| Proposed model | These marks are the initial endeavor to identify snake species using bite marks, which proves to be a more practical and accurate approach, as demonstrated in Table 6 |

3 Methodology

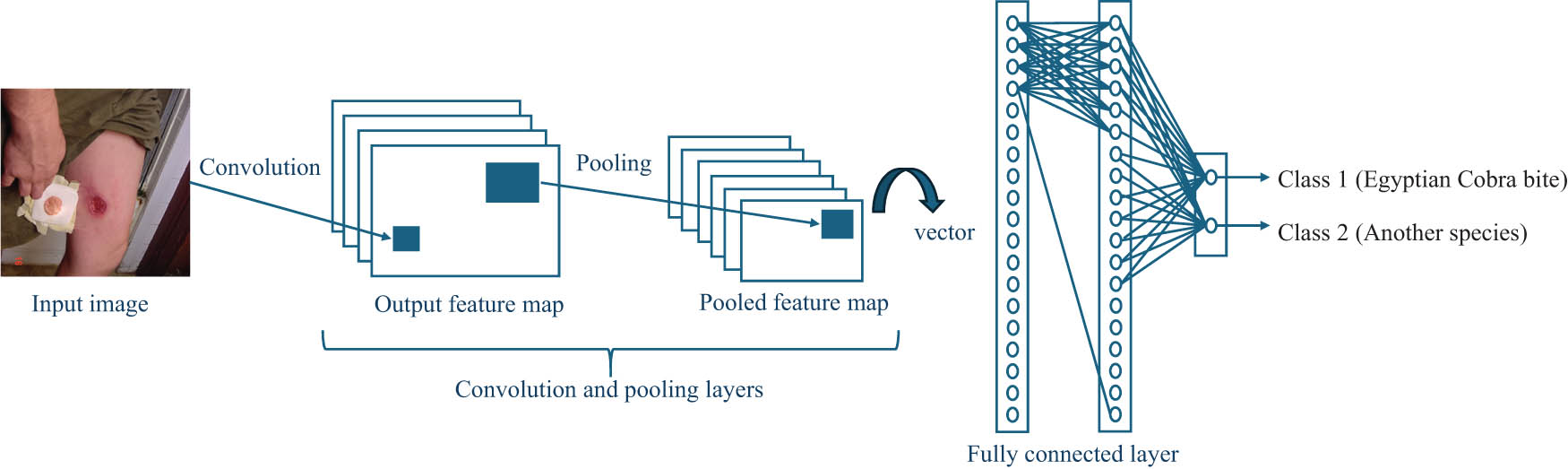

Snake species identification plays a crucial role in the initial treatment of snakebite victims. Deep learning techniques have demonstrated remarkable success in various healthcare applications. In this study, we leverage these techniques to accurately identify Egyptian cobra bites based on images of the bite marks, as shown in Figure 2 [17]. To train our model, we curated a dataset comprising 500 images of cobra bite marks and 600 images of bite marks from other snake species found in Egypt. To enhance the generalization and accuracy of our model, we employ advanced techniques such as transfer learning, which enables the model to leverage knowledge learned from pre-trained networks, and data augmentation (DA), which augments the dataset by applying transformations to existing images. These strategies contribute to the robustness and reliability of our model, ensuring its effectiveness in accurately identifying Egyptian cobra bites. By leveraging deep learning techniques and employing a well-curated dataset, our model holds significant promise in improving the efficiency and precision of snake species identification, thereby enabling prompt and appropriate medical interventions for snakebite victims.

Architecture of our classifier. Source: Proposed, created and drawn by the authors.

3.1 IoT-based snake-bit detection

Traditional methods of snake bite detection often rely on visual identification of bite marks or symptoms, which can lead to delays in treatment and potentially fatal outcomes. To address this challenge, we propose the integration of IoT technology with wearable sensors for real-time snake bite detection and identification. Our approach utilizes wearable devices equipped with a combination of advanced sensors capable of detecting key indicators of snake bites. These sensors include pressure sensors, temperature sensors, accelerometers/gyroscopes, electrochemical sensors, and multispectral imaging technology.

Pressure sensors: Detect sudden pressure spikes indicative of a snake bite.

Temperature sensors: Monitor localized changes in skin temperature caused by venom injection.

Accelerometers/gyroscopes: Detect abnormal movement patterns associated with snake bites.

Upon detecting a potential snake bite, the wearable sensors immediately transmit data to a central monitoring system via wireless communication protocols such as Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. This real-time data transmission ensures prompt notification of snake bite incidents, enabling rapid response and medical intervention.

We develop equations to detect snake bites based on sensor data that require a deep understanding of snake venom effects on the body and how these effects manifest in sensor readings, as shown in equations (1)–(4). Let us say we have sensors measuring pressure (P), temperature (T), and biochemical markers (B). We want to determine the likelihood of a snake bite based on these sensor readings. We determine typical readings for each sensor in the absence of a snake bite (normal case-reading). This baseline can vary depending on the individual and environmental conditions, as shown in Table 2. After that, we determine how sensor readings deviate from baseline values in the presence of a snake bite. For example, pressure might increase due to swelling at the bite site, temperature might rise due to localized inflammation, and certain biochemical markers might increase due to venom effects

Normal and danger values of sensor readings

| Reading | Normal | Danger |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure | 1,000 mmHg | 1,050 mmHg |

| Temperature | 37°C | 38.5 |

| Biochemical | 0 | 50 |

Here, w 1, w 2, and w 3 are weighting factors representing the relative importance of each sensor in detecting a snake bite. These weighting values need to be determined through experimentation and validation; ΔP, ΔT, and ΔB are the deviations in pressure, temperature, and biochemical marker reading, respectively. Also, P baseline is the baseline pressure reading, T baseline is the baseline temperature reading, and B baseline is the baseline biomedical reading, P Snake Bite is the probability that the victim was exposed to a snake bite. After that, we gather real-world data from sensor readings in both snake bite and non-bite scenarios and then adjust weighting factors and threshold values based on the observed correlation between sensor readings and snake bites. We continuously refine the equation based on feedback from experts and real-world observations.

3.2 Case study for our proposed equation

John, while hiking in a forest known to be inhabited by venomous snakes, suddenly felt a sharp pain in his leg [21]. He quickly examined his leg and noticed fang marks and swelling around the bite site.

Here are the readings taken immediately after the suspected snake bite:

Pressure reading (P):

Current pressure reading: 1,055 mmHg (higher than the baseline of 1,000 mmHg)

Temperature reading (T):

Current temperature reading: 38.5°C (higher than the baseline of 37°C)

Biochemical marker reading (B):

Current biochemical marker reading: 20 units (elevated from the baseline of 0 units)

Now, let us plug these values into equation (4):

Likelihood of snake bite = 1⋅(1,055−1,000) + 1⋅(38.5−37) + 1⋅(20−0)

Likelihood of snake bite = 1⋅(1,055−1,000) + 1⋅(38.5−37) + 1⋅(20−0)

Likelihood of snake bite = 55 + 1.5 + 20 likelihood of snake bite = 55 + 1.5 + 20

Likelihood of snake bite = 76.5

Since the likelihood score is above a predetermined threshold (let us say 50 for this example), it indicates a probable snake bite. Based on this evaluation, it is likely that John has been bitten by a snake.

3.3 Dataset collecting

Obtaining a suitable dataset posed a significant challenge for our research. Due to the sensitive nature of bite mark images, there is a scarcity of readily available datasets that align with our specific objectives. Access to such images is restricted and requires patient consent. Consequently, extensive and meticulous online searches were conducted to locate bite mark images caused by Egyptian cobra bites, amplifying the complexity of our task. To compile our dataset, we extensively scoured zoological and medical scientific papers, as well as online medical websites [17]. Through these endeavors, we successfully gathered a total of 847 images showing bite marks from Egyptian cobras and 1,005 images of bite marks from other snake species, as illustrated in Figure 2. Given the challenges mentioned earlier, this compilation stands as a noteworthy accomplishment. However, we recognize the need to address this challenge to attain the highest possible accuracy. To address the diversity in image sizes within the dataset, we employed DA techniques and leveraged transfer learning. This approach involved resizing all bite mark images to a uniform dimension of 1,000 × 1,000 pixels. Consequently, we achieved RGB reordering, resulting in an input format of 1,000 × 1,000 × 3 for our proposed model. Among the included cases, 73% corresponded to male individuals, while 27% pertained to female individuals. Furthermore, 54% of the cases involved young individuals, whereas 46% encompassed older individuals, some of whom suffered from chronic diseases. Overcoming these challenges through the utilization of DA and transfer learning techniques has enabled us to address the intricacies inherent in our dataset. By employing these strategies, our objective is to improve the accuracy and resilience of our model, making it suitable for various scenarios and delivering the most dependable results.

3.4 Dataset pre-processing

Enhancing the generalization of deep learning is a critical challenge in our research. Generalization refers to a model’s ability to perform well on unseen data (testing data) after being trained on a set of known data (training data). Typically, achieving strong generalization necessitates a large dataset that encompasses a diverse range of features. However, in certain scenarios, dataset availability may be limited, presenting a challenge in enhancing model accuracy. In order to tackle this challenge and improve our model’s precision, we incorporate a method known as DA. DA enables us to artificially expand the size of the training dataset by generating altered variations of the existing data DA offers a mechanism to artificially expand the size of the training dataset by generating modified versions of existing data. In our study, we employ specific augmentation techniques, namely image flipping and also zooming-in, to augment our dataset size, as outlined in Table 3. By applying these augmentation techniques, we aim to increase the diversity and variability within our dataset, enabling our model to learn more robust and representative features.

Values of augmentation parameters

| Augmentation | Value |

|---|---|

| Flipping-technique | 110 |

| Zooming-technique | 0.6–0.9 |

The application of a two-dimensional Gaussian filter is commonly employed for noise reduction and smoothing purposes [2]. However, its implementation demands substantial processing resources and performance. The Gaussian operator is typically utilized, with Gaussian smoothing accomplished through convolution, as shown in equation (5)

The Gaussian operators in two dimensions (circularly symmetric) are showcased by

In this context, σ (Sigma) represents the standard deviation of the Gaussian function, with higher values yielding superior smoothing effects. The coordinates (x, y) denote the Cartesian coordinates within the image, indicating the dimensions of the window. These filters involve summation and multiplication operations between the kernel and image, with the image typically represented in a matrix format ranging from 0 to 255 on an 8-bit scale. The kernel is a standardized square matrix ranging between 0 and 1. Following this, the kernel’s size is expressed in bits. During the convolution process, the total bits of the kernel and all elements of the image are divided by the power of 2.

3.5 Transfer learning

Transfer learning is a highly effective approach that leverages pre-trained deep learning models as a starting point for new tasks. It involves reusing a model previously trained on one task and applying it to a related task, resulting in accelerated progress during the modeling process. By utilizing transfer learning, we can achieve improved performance compared to training a model from scratch, especially when working with given limited data availability; our snake species identification model incorporates three well-established pre-trained models: VGG19, VGG-16, and ResNet-101. Notably, VGG-19 is a deep CNN comprising 19 layers, including 5 convolutional blocks and 3 fully connected layers. In comparison, ResNet-101 is a variant of the ResNet CNN with a remarkable depth of 101 layers, featuring 33 residual blocks. In our model, the convolutional layer plays a crucial role as it conducts feature extraction. This layer employs the convolution operation, which replaces conventional matrix multiplication and serves as the fundamental component of CNNs. The convolutional layer’s parameters consist of a set of trainable filters, also known as kernels. Its primary purpose is to detect features within various regions of the input image and generate corresponding feature maps. This operation involves applying a specific filter over the input image, with typical filter sizes being 3 × 3, 5 × 5, or 7 × 7 pixels. The outcome of this convolution operation results in the creation of activation maps, which contain locally distinctive features relevant to the specific task, as shown in equation (7)

In this context, each convolution layer is equipped with a filter represented as m

1. The output of Layer l comprises

In the pooling operation, a vector “v” is reduced to a single scalar “f(v)” through the pooling process “f.” Two types of pooling are commonly used: average pooling and max pooling. In this case, max pooling is employed. Fully connected layers serve the following purposes: (1) they convert the feature maps from the last convolution or pooling layer into a one-dimensional vector, (2) connect to one or more dense layers, (3) adjust the weights, and (4) provide the final classification prediction.

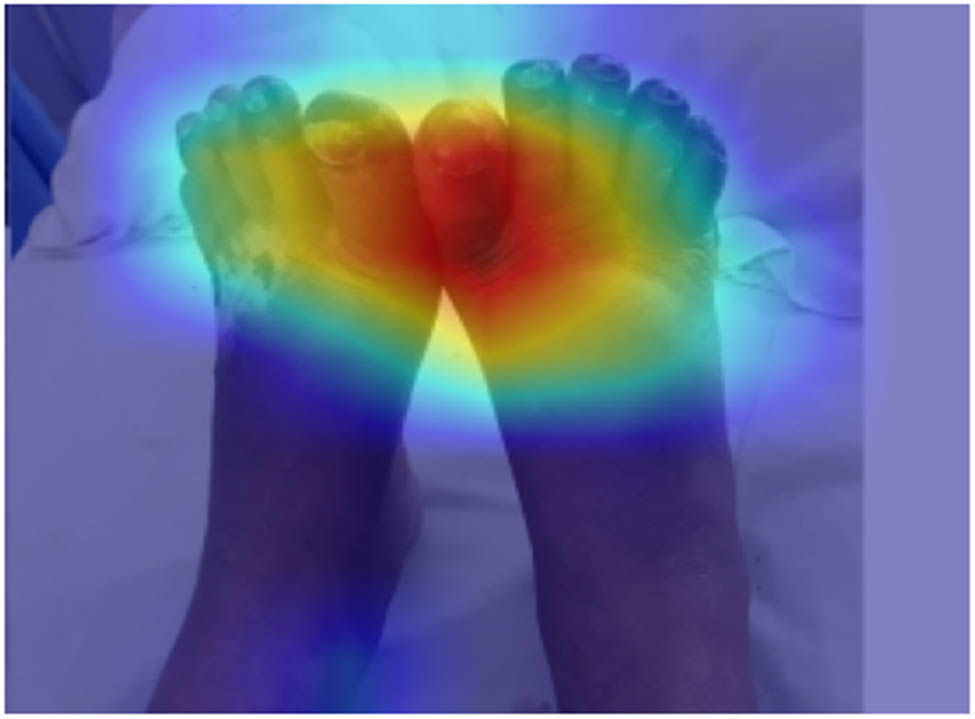

3.6 Visualization

The lack of tools for understanding the functioning of black-box models poses a challenge to the integration of deep learning in medical imaging. In the medical field, where trust among clinicians and patients is paramount, interpretability and reliability are essential. Moreover, deep learning models have the potential to unveil biologically distinctive patterns by identifying underlying features that conventional diagnosis might overlook. However, these valuable insights can only be leveraged if the model’s decision-making process is interpretable and comprehensible to those examining the results. When the reasoning behind a model’s predictions is unknown or poorly understood, it raises questions about the level of trust in those predictions. In our research, we employ a gradient-weighted class activation mapping technique called Grad-CAM. This method is both class-specific and proficient at pinpointing relevant regions within an image. Grad-CAM operates by using gradients to assign scores to various parts of an image based on a trained model’s assessment of a given image category. As demonstrated in a prior study [22], Grad-CAM outperformed other explainable techniques, such as CAM and Grad-CAM++. Consequently, we have opted to utilize Grad-CAM for interpreting our model’s decisions and highlighting the salient features within the bite marks.

4 Performance evaluation

This section will delve into the assessment of our model’s performance in classifying snake bite marks, which are categorized into two distinct classes: Egyptian cobra and non-Egyptian cobra. Numerous experiments were conducted to fine-tune the model's optimal values. The values of the parameters used in our experiments are shown in Table 4.

Values of used parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning rate (α) | 0.01 |

| Epochs | 150 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Epsilon |

|

4.1 Confusion matrix

The confusion matrix is a valuable tool for evaluating the performance of deep learning models in classification tasks. This matrix enables the comparison of predicted outcomes with actual values, consisting of four key components: False Positives (FP), True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN), as outlined in Table 5. The matrix’s rows correspond to “Real class values,” while the columns represent “Predicted class values.” This analysis aids in evaluating the model’s performance. Based on the validation dataset’s confusion matrix, our model attained a sensitivity of 96.7% and a specificity of 71.5%. Sensitivity assesses the model’s capability to accurately detect Egyptian cobra bite marks (True Positives, TP) out of the total number of such bites in the test dataset. Our model made accurate predictions for 170 out of 220 Egyptian cobra bites, indicating a 96.7% success rate. This result signifies a minimal error rate of 3.3% and underscores the model’s effectiveness in identifying Egyptian cobra bite marks. Specificity, on the other hand, refers to the model’s ability to correctly identify non-Egyptian cobra bites (True Negatives, TN). Our model achieved a specificity rate of 71.4%. By calculating the overall accuracy based on the confusion matrix, our model achieved an accuracy of 90.9%. This demonstrates its high accuracy compared to other models for snake species identification, as shown in Table 3. The increased accuracy can be ascribed to the utilization of bite mark images in the training data, which provide the model with effective features for precise bite mark classification. The unique structural characteristics and functional properties of venom components in various snake species play a crucial role in the successful classification, as they rely on well-defined parameters [23].

Confusion matrix

| Predicted | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cobra | Other | ||

| Actual | Cobra | TP = 170 | FN = 8 |

| Other | FP = 12 | TN = 30 | |

4.2 Accuracy

The validation accuracy ranged from 74.6 to 91.5%. Similarly, the training accuracy ranged from 77.8 to 94.01%. This indicates the model’s ability to generalize, a crucial aspect of deep learning models. In comparison to existing approaches outlined in Table 6, our model surpasses them in terms of performance. Unlike these approaches that rely on snake image classes, our model overcomes the limitations caused by partial snake visibility or coiled positions. These constraints result in missing important snake features in training images.

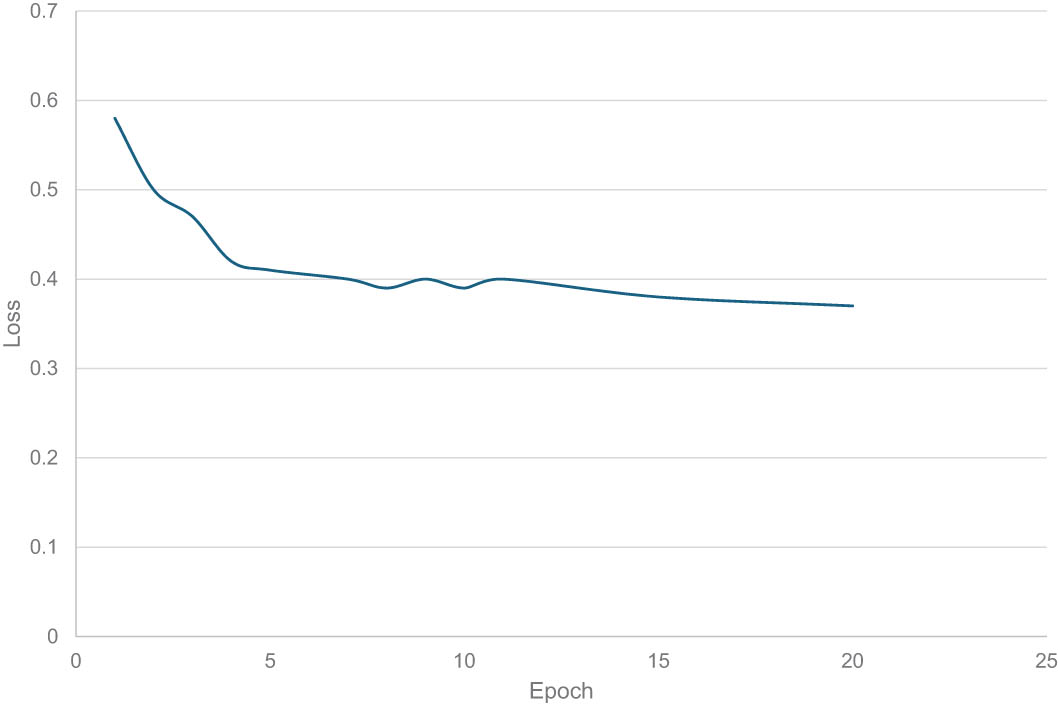

4.3 Loss

With regard to the loss factor, our model consistently exhibits impressive outcomes when employing different models in our transfer learning approach, as illustrated in Figure 3. These findings highlight the efficacy of our technique in promoting a resilient learning process and in harnessing the dataset to extract meaningful features, thereby enabling our model to achieve accurate identification of “Egyptian Cobra” bites.

Loss of the proposed model. Source: Proposed, created and drawn by the authors.

4.4 Time decision

Our primary objective is the swift identification of the snake species responsible for the attack, as this is a critical initial step in saving the victim’s life. Therefore, expediting this process is of paramount importance. To evaluate the time aspect, we conducted a comparative analysis with prior research endeavors. The time taken for a decision is influenced by two main factors: transmission time and prediction time. Concerning transmission time, our approach follows the edge node paradigm, siting the classifier in close proximity to the user, which results in reduced transmission time. In terms of prediction time, as demonstrated in Table 6, our approach stands out for its rapid predictions due to its straightforward implementation.

4.5 Interpretation parameter

This parameter is recent and important as it provides insights and justifications for the decisions made by deep learning models. By understanding why a model makes certain predictions or classifications, we gain transparency and trust in its output. As shown in Figure 4, our model considers only the injury place and neglects all other possible features. This reflects our model interests.

Heatmap for our model. Source: Proposed, created and drawn by the authors.

5 Limitations

We try to apply this efficient idea to save the lives of many people that exposed to death because of the Egyptian Cobra every year. However, there are some limitations that we will handle in our future work. First, dataset limitations: While we assembled a comprehensive dataset for training our deep learning model, it may not fully capture the variability of snake bites encountered in real-world scenarios. We will discuss the potential biases or shortcomings of our dataset and explore avenues for improving its diversity and representativeness. Second, generalizability: Although our model demonstrates promising performance in recognizing Egyptian cobra bites, its generalizability to other geographic regions or snake species may be limited. We will acknowledge this constraint and highlight the importance of further validation and adaptation for different contexts. Third, technical challenges: Implementing IoT-enabled wearable devices for snake bite detection may pose technical challenges, such as battery life, connectivity issues, and sensor reliability. We will discuss these technical limitations and potential strategies for mitigating their impact on the effectiveness of our system.

6 Conclusion and future works

In conclusion, our research presents a pioneering approach to addressing the challenges posed by snake envenomation through the integration of IoT technology with wearable sensors for snake bite detection. By harnessing advanced sensor technology and deep learning algorithms, we have developed a comprehensive system capable of swiftly and accurately detecting snake bites in real-time.

A pivotal aspect of snakebite management is the precise identification of the snake species responsible, and our model achieves this with remarkable precision, boasting a 91% precision rate and a sensitivity of 96.7% in recognizing Egyptian Cobra bites. This advancement surpasses previous methodologies reliant on impractical images of the attacking snake, highlighting the practicality and efficacy of our approach. Furthermore, by exclusively training our model on bite marks, we depart from conventional approaches, enhancing the reliability and applicability of our findings. The theoretical implications of our research extend to the realms of IoT integration and deep learning methodologies, offering insights into the potential of interdisciplinary solutions in addressing complex healthcare challenges. On a practical level, our system holds significant advantages for snakebite management, offering real-time detection capabilities that can expedite emergency responses and improve patient outcomes. However, we acknowledge certain limitations, including dataset biases and the need for further validation across diverse geographic regions and snake species. Moving forward, future research endeavors could explore the integration of additional sensor modalities, such as biochemical markers, to enhance the accuracy and reliability of snakebite detection systems. Additionally, investigations into community-based interventions and awareness programs may contribute to the prevention and mitigation of snakebite incidents in high-risk areas. Also, enhancing the security and reliability of the model is one of the most important aims in future works.

-

Funding information: This research received no external funding.

-

Author contributions: Mohamed Elhoseny found the dataset and made the required literature review before working. Ahmed Hassan presented the basic idea and made the practical works. Marwa H. Shehata wrote the Introduction and Related Work sections. Mohammed Kayed wrote Methodology and Performance Evaluation sections and reviewed the paper.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Omran MAA, Fabb SA, Dickson G. Biochemical and morphological analysis of cell death induced by Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) venom on cultured cells. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2004;10:219–41. 10.1590/S1678-91992004000300004.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Morsy TA, Khater MKA, Khalifa AKE. Principle management of snake bites with reference to Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2021;51(2):332–42. 10.21608/jesp.2021.193313.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] James AP, Mathews B, Sugathan S, Raveendran DK. Discriminative histogram taxonomy features for snake species identification. Hum-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2014;4:1–11. 10.1186/s13673-014-0011-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Premawardhena AP, De Silva CE, Fonseka MMD, Gunatilake SB, De Silva HJ. Low dose subcutaneous adrenaline to prevent acute adverse reactions to antivenom serum in people bitten by snakes: randomised, placebo controlled trial. Bmj. 1999;318(7190):1041–3. 10.1136/bmj.318.7190.1041.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Patel A, Cheung L, Khatod N, Matijosaitiene I, Arteaga A, Gilkey JW. Revealing the unknown: real-time recognition of Galápagos snake species using deep learning. Animals. 2020;10(5):806. 10.3390/ani10050806.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Rajabizadeh M, Rezghi M. A comparative study on image-based snake identification using machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–16. 10.1038/s41598-021-86760-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Kacprzyk J. Lecture notes in networks and systems. USA: Springer; 2019. 10.1007/978-3-319-99987-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Ying Z, Li G, Ren Y, Wang R, Wang W. A new image contrast enhancement algorithm using exposure fusion framework. In International Conference on Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns. Cham: Springer; 2017, August. p. 36–46. 10.1007/978-3-319-64698-5_4.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Phon-Amnuaisuk S, Au TW, Omar S. Computational intelligence in information systems. In Proceedings of the Computational Intelligence in Information Systems Conference (CIIS 2016). Vol. 532; 2016. 10.1007/978-981-10-2777-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Nishioka SDA, Silveira PVP, Bauab FA. Bite marks are useful for the differential diagnosis of snakebite in Brazil. Wilderness Environ Med. 1995;6(2):183–8. 10.1580/1080-6032(1995)006[0183:BMUFTD]2.3.CO;2.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Ghorpade SN, Zennaro M, Chaudhari BS, Saeed RA, Alhumyani H, Abdel-Khalek S. A novel enhanced quantum PSO for optimal network configuration in heterogeneous industrial IoT. IEEE Access. 2021;9:134022–36. 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3115180.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Vasmatkar M, Zare I, Kumbla P, Pimpalkar S, Sharma A. Snake species identification and recognition. In 2020 IEEE Bombay Section Signature Conference (IBSSC). IEEE; 2020, December. p. 1–5. 10.1109/IBSSC51096.2020.9332141.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Kalinathan L, Prabavathy Balasundaram PG, Bathala SS, Mukesh RK. Automatic snake classification using deep learning algorithm. In CLEF (Working Notes); 2021. p. 1587–96. 10.1007/978-3-030-85251-1_13.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Bloch L, Friedrich CM. EfficientNets and Vision transformers for snake species identification using image and location information. In CLEF (Working Notes); 2021. p. 1477–98. 10.1007/978-3-030-85251-1_12.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Patel A, Cheung L, Khatod N, Matijosaitiene I, Arteaga A, Gilkey Jr JW. Revealing the unknown: Real-time recognition of Galápagos snake species using deep learning. Animals. 2020;10(5):806. 10.3390/ani10050806.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Kalinathan L, Balasundaram P, Ganesh P, Bathala SS, Mukesh RK. Automatic snake classification using deep learning algorithm. In CLEF (Working Notes); 2021. p. 1587–96. 10.1007/978-3-030-85251-1_13.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Hassan A, Elhoseny M, Kayed M. Hierarchical cloud architecture for identifying the bite of “Egyptian cobra” based on deep learning and quantum particle swarm optimization. Sci Rep. 2023;13:5250. 10.1038/s41598-023-29292-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Tekgül S, Yilmaz GN. Snake detection and blurring system to prevent unexpected appearance of snake images on visual media sources using deep learning. J Artif Intell Data Sci 1(2):125–35. 10.54307/jaids.v1i2.25.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Picek L, Durso AM, Bolon I, de Castañeda RR. Overview of SnakeCLEF 2021: Automatic snake species identification with country-level focus. In Proceedings of the Working Notes of CLEF 2021 – Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum. Bucharest: CEUR-WS; 2021. p. 1463–1476. 10.1007/978-3-030-85251-1_11.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Bolon I, Picek L, Durso AM, Alcoba G, Chappuis F, Ruiz de Castañeda R. An artificial intelligence model to identify snakes from across the world: Opportunities and challenges for global health and herpetology. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(8):e0010647. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010647.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Najafabadi MM, Villanustre F, Khoshgoftaar TM, Seliya N, Wald R, Muharemagic E. Deep learning applications and challenges in big data analytics. J Big data. 2015;2(1):1–21. 10.1186/s40537-014-0007-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Singh RK, Pandey R, Babu RN. COVIDScreen: explainable deep learning framework for differential diagnosis of COVID-19 using chest X-rays. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33:8871–92. 10.1007/s00521-020-05673-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Zhang Y, Lee WH, Gao R, Xiong YL, Wang WY, Zhu SW. Effects of Pallas’ viper (Agkistrodon halys pallas) venom on blood coagulation and characterization of a prothrombin activator. Toxicon. 1998;36(1):143–52. 10.1016/S0041-0101(97)00133-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Abdurrazaq IS, Suyanto S, Utama DQ. Image-based classification of snake species using convolutional neural network. In 2019 International Seminar on Research of Information Technology and Intelligent Systems (ISRITI). IEEE; 2019, December. p. 97–102. 10.1109/ISRITI48646.2019.9034631.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Synergistic effect of artificial intelligence and new real-time disassembly sensors: Overcoming limitations and expanding application scope

- Greenhouse environmental monitoring and control system based on improved fuzzy PID and neural network algorithms

- Explainable deep learning approach for recognizing “Egyptian Cobra” bite in real-time

- Optimization of cyber security through the implementation of AI technologies

- Deep multi-view feature fusion with data augmentation for improved diabetic retinopathy classification

- A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving multi-objective single-machine scheduling problems

- Estimating glycemic index in a specific dataset: The case of Moroccan cuisine

- Hybrid modeling of structure extension and instance weighting for naive Bayes

- Application of adaptive artificial bee colony algorithm in environmental and economic dispatching management

- Stock price prediction based on dual important indicators using ARIMAX: A case study in Vietnam

- Emotion recognition and interaction of smart education environment screen based on deep learning networks

- Supply chain performance evaluation model for integrated circuit industry based on fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy neural network

- Application and optimization of machine learning algorithms for optical character recognition in complex scenarios

- Comorbidity diagnosis using machine learning: Fuzzy decision-making approach

- A fast and fully automated system for segmenting retinal blood vessels in fundus images

- Application of computer wireless network database technology in information management

- A new model for maintenance prediction using altruistic dragonfly algorithm and support vector machine

- A stacking ensemble classification model for determining the state of nitrogen-filled car tires

- Research on image random matrix modeling and stylized rendering algorithm for painting color learning

- Predictive models for overall health of hydroelectric equipment based on multi-measurement point output

- Architectural design visual information mining system based on image processing technology

- Measurement and deformation monitoring system for underground engineering robots based on Internet of Things architecture

- Face recognition method based on convolutional neural network and distributed computing

- OPGW fault localization method based on transformer and federated learning

- Class-consistent technology-based outlier detection for incomplete real-valued data based on rough set theory and granular computing

- Detection of single and dual pulmonary diseases using an optimized vision transformer

- CNN-EWC: A continuous deep learning approach for lung cancer classification

- Cloud computing virtualization technology based on bandwidth resource-aware migration algorithm

- Hyperparameters optimization of evolving spiking neural network using artificial bee colony for unsupervised anomaly detection

- Classification of histopathological images for oral cancer in early stages using a deep learning approach

- A refined methodological approach: Long-term stock market forecasting with XGBoost

- Enhancing highway security and wildlife safety: Mitigating wildlife–vehicle collisions with deep learning and drone technology

- An adaptive genetic algorithm with double populations for solving traveling salesman problems

- EEG channels selection for stroke patients rehabilitation using equilibrium optimizer

- Influence of intelligent manufacturing on innovation efficiency based on machine learning: A mechanism analysis of government subsidies and intellectual capital

- An intelligent enterprise system with processing and verification of business documents using big data and AI

- Hybrid deep learning for bankruptcy prediction: An optimized LSTM model with harmony search algorithm

- Construction of classroom teaching evaluation model based on machine learning facilitated facial expression recognition

- Artificial intelligence for enhanced quality assurance through advanced strategies and implementation in the software industry

- An anomaly analysis method for measurement data based on similarity metric and improved deep reinforcement learning under the power Internet of Things architecture

- Optimizing papaya disease classification: A hybrid approach using deep features and PCA-enhanced machine learning

- Handwritten digit recognition: Comparative analysis of ML, CNN, vision transformer, and hybrid models on the MNIST dataset

- Multimodal data analysis for post-decortication therapy optimization using IoMT and reinforcement learning

- Predicting early mortality for patients in intensive care units using machine learning and FDOSM

- Uncertainty measurement for a three heterogeneous information system based on k-nearest neighborhood: Application to unsupervised attribute reduction

- Genetic algorithm-based dimensionality reduction method for classification of hyperspectral images

- Power line fault detection based on waveform comparison offline location technology

- Assessing model performance in Alzheimer's disease classification: The impact of data imbalance on fine-tuned vision transformers and CNN architectures

- Hybrid white shark optimizer with differential evolution for training multi-layer perceptron neural network

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review of deep learning and machine learning techniques for early-stage skin cancer detection: Challenges and research gaps

- An experimental study of U-net variants on liver segmentation from CT scans

- Strategies for protection against adversarial attacks in AI models: An in-depth review

- Resource allocation strategies and task scheduling algorithms for cloud computing: A systematic literature review

- Latency optimization approaches for healthcare Internet of Things and fog computing: A comprehensive review

- Explainable clustering: Methods, challenges, and future opportunities

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Synergistic effect of artificial intelligence and new real-time disassembly sensors: Overcoming limitations and expanding application scope

- Greenhouse environmental monitoring and control system based on improved fuzzy PID and neural network algorithms

- Explainable deep learning approach for recognizing “Egyptian Cobra” bite in real-time

- Optimization of cyber security through the implementation of AI technologies

- Deep multi-view feature fusion with data augmentation for improved diabetic retinopathy classification

- A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving multi-objective single-machine scheduling problems

- Estimating glycemic index in a specific dataset: The case of Moroccan cuisine

- Hybrid modeling of structure extension and instance weighting for naive Bayes

- Application of adaptive artificial bee colony algorithm in environmental and economic dispatching management

- Stock price prediction based on dual important indicators using ARIMAX: A case study in Vietnam

- Emotion recognition and interaction of smart education environment screen based on deep learning networks

- Supply chain performance evaluation model for integrated circuit industry based on fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy neural network

- Application and optimization of machine learning algorithms for optical character recognition in complex scenarios

- Comorbidity diagnosis using machine learning: Fuzzy decision-making approach

- A fast and fully automated system for segmenting retinal blood vessels in fundus images

- Application of computer wireless network database technology in information management

- A new model for maintenance prediction using altruistic dragonfly algorithm and support vector machine

- A stacking ensemble classification model for determining the state of nitrogen-filled car tires

- Research on image random matrix modeling and stylized rendering algorithm for painting color learning

- Predictive models for overall health of hydroelectric equipment based on multi-measurement point output

- Architectural design visual information mining system based on image processing technology

- Measurement and deformation monitoring system for underground engineering robots based on Internet of Things architecture

- Face recognition method based on convolutional neural network and distributed computing

- OPGW fault localization method based on transformer and federated learning

- Class-consistent technology-based outlier detection for incomplete real-valued data based on rough set theory and granular computing

- Detection of single and dual pulmonary diseases using an optimized vision transformer

- CNN-EWC: A continuous deep learning approach for lung cancer classification

- Cloud computing virtualization technology based on bandwidth resource-aware migration algorithm

- Hyperparameters optimization of evolving spiking neural network using artificial bee colony for unsupervised anomaly detection

- Classification of histopathological images for oral cancer in early stages using a deep learning approach

- A refined methodological approach: Long-term stock market forecasting with XGBoost

- Enhancing highway security and wildlife safety: Mitigating wildlife–vehicle collisions with deep learning and drone technology

- An adaptive genetic algorithm with double populations for solving traveling salesman problems

- EEG channels selection for stroke patients rehabilitation using equilibrium optimizer

- Influence of intelligent manufacturing on innovation efficiency based on machine learning: A mechanism analysis of government subsidies and intellectual capital

- An intelligent enterprise system with processing and verification of business documents using big data and AI

- Hybrid deep learning for bankruptcy prediction: An optimized LSTM model with harmony search algorithm

- Construction of classroom teaching evaluation model based on machine learning facilitated facial expression recognition

- Artificial intelligence for enhanced quality assurance through advanced strategies and implementation in the software industry

- An anomaly analysis method for measurement data based on similarity metric and improved deep reinforcement learning under the power Internet of Things architecture

- Optimizing papaya disease classification: A hybrid approach using deep features and PCA-enhanced machine learning

- Handwritten digit recognition: Comparative analysis of ML, CNN, vision transformer, and hybrid models on the MNIST dataset

- Multimodal data analysis for post-decortication therapy optimization using IoMT and reinforcement learning

- Predicting early mortality for patients in intensive care units using machine learning and FDOSM

- Uncertainty measurement for a three heterogeneous information system based on k-nearest neighborhood: Application to unsupervised attribute reduction

- Genetic algorithm-based dimensionality reduction method for classification of hyperspectral images

- Power line fault detection based on waveform comparison offline location technology

- Assessing model performance in Alzheimer's disease classification: The impact of data imbalance on fine-tuned vision transformers and CNN architectures

- Hybrid white shark optimizer with differential evolution for training multi-layer perceptron neural network

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review of deep learning and machine learning techniques for early-stage skin cancer detection: Challenges and research gaps

- An experimental study of U-net variants on liver segmentation from CT scans

- Strategies for protection against adversarial attacks in AI models: An in-depth review

- Resource allocation strategies and task scheduling algorithms for cloud computing: A systematic literature review

- Latency optimization approaches for healthcare Internet of Things and fog computing: A comprehensive review

- Explainable clustering: Methods, challenges, and future opportunities