Abstract

Ethnic entrepreneurship is the phenomenon that individuals from certain ethnic backgrounds participate in entrepreneurial activities. Individuals from those ethnic backgrounds are affected by various factors such as entrepreneurial tendencies, cultural values, social networks, and economic opportunities. Although such factors have the potential to explain ethnic entrepreneurship, it is important to continually update research and definitions in this field as ethnic entrepreneurship is an ever-growing topic. The purpose of this article is to be a part of the studies on ethnic entrepreneurship and to contribute to the field by identifying the conditions that influence the entrepreneurial process of Meskhetian Turks, who immigrated to the USA under special laws and became successful in establishing their own businesses. In order to achieve this purpose, in-depth interviews were conducted with entrepreneurs, and the findings are discussed in the context of the interactional model. According to the findings, social, capital, and ethnic networks play a significant role in business establishment and development, knowledge acquisition for business, and labor supply. In addition, due to the differences in the migration experiences of entrepreneurs, it is seen that both ethnic and non-ethnic networks affect entrepreneurship in the dimension of resource mobility. This study confirms the need to evaluate the benefits of ethnic entrepreneurship as a dynamic field.

1 Introduction

“How immigrant entrepreneurs are revitalizing Dayton” [1]

“One Ohio City’s Growth Strategy? Immigrants” [2]

“Ailing Midwestern Cities Extend a Welcoming Hand to Immigrants” [3]

“Dayton named one of the nation’s top 7 enterprising cities” [4]

– News headlines from the National and Local Press in the USA

People who had to leave the lands where they were born, raised and lived for various reasons, either earn money by working in paid jobs or decide to establish their own business in order to continue their lives in the country they go to and to provide for their family. In the literature, ethnic entrepreneurship is defined in the simplest form as the entrepreneurial activities of those with ethnic identity by establishing their own businesses. Information about the entrepreneurial processes of Meskhetian Turks, who were exposed to various discriminations and troubles more than once and immigrated from their homeland, first to Uzbekistan, then to Russia, and finally to the United States in 2004 with a special law, will be provided in this study.

The studies concerning migrants and ethnic entrepreneurs were The Notion of Class and Ethnic Resources by Ivan Light, The Concept of Intermediary Minority by Edna Bonacich, the argument by Alejandro Portes on the establishment of “ethnic settlements” in the 1970s, and John Modell and Howard Aldrich published similar studies. Roger Waldinger added to these studies in the 1970s and 1980s, and these researchers collaborated on ethnic entrepreneurship in the 1990s (Fregetto, 2004, p. 166; Waldinger, 1989, p. 49). Ethnic entrepreneurship is absolutely not a novel phenomenon for our modern society; however, potential entrepreneurs are the consequence of migration flows, sometimes for economic reasons and sometimes for reasons stimulated by foreign actors such as war, suppression, and natural famine disasters (Masurel et al., 2004, p. 78). Ethnic entrepreneurs often immigrated from less developed to more developed countries, particularly to attractive demographic areas in cities (Waldinger, 1989).

Researchers developed and used various theories and models to explain the concept of ethnic entrepreneurship (Fregetto, 2004). It is seen that some theories/perspectives combine the social, cultural, and economic factors to explain ethnic entrepreneurship. These theories are mixed embeddedness by Light (1988), interactional model by Waldinger et al. (1990), blocked mobility perspective by Gold and Kibria (1993), (ethnic) social capital perspective by Sanders and Nee (1996), women entrepreneurship/gender differences by Baycan-Levent et al. (2003), and ethnic diversity by Smallbone et al. (2010). These theories explain that the purpose of ethnic groups in establishing a business is to survive in society by increasing their social mobility and obtaining better economic conditions (Indarti et al., 2021, p. 438).

Entrepreneurs are one of the important factors that contribute to change within a dynamic society with globalization in modern economic life (Ma et al., 2013; Ratten, 2023). Entrepreneurship is a phenomenon that encourages the creativity, initiative, and freedom of individuals who can take risks and utilize dynamic and complex opportunities in the context of uncertainty (Ramadani et al., 2014) by bringing together the factors of production to contribute to economic growth and maximize profits (Mickiewicz et al., 2019). In a classic saying, entrepreneurship is combining resources in new ways to create something of value (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 112). Ethnic entrepreneurship is defined as “a set of connections and organized interaction models established among people who share a common national background and migration experiences” (Waldinger et al., 1990, p. 3). In this sense, an ethnic entrepreneur can be defined as the owner of a company that carries out business by encouraging solidarity, trust, flexibility, and personal motivation (Chaganti & Greene, 2002) under the same roof with a social group of common origin based on relative cultural similarity.

Ethnic entrepreneurship refers mainly to small and medium-sized business activities carried out by entrepreneurs of a particular sociocultural or ethnic origin and tends to be an indigenous and important part of the local economy (Masurel et al., 2001, p. 2). Ethnic entrepreneurs create employment and economic opportunities for their own communities through their businesses. In addition, ethnic entrepreneurs support cultural diversity by promoting the relationship between different cultures and economic affairs. This has a positive effect on economic growth and development in general. The numerical data on ethnic entrepreneurs’ contribution to the economy vary for each country. According to a study conducted in the United States in 2020, the total turnover of businesses by ethnic entrepreneurs exceeded $1.2 trillion, and the number of ethnic businesses in the United States corresponds to approximately 15% of all businesses (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). The total turnover of ethnic businesses in the UK in 2019 was recorded as £36.5 billion, and the number of ethnic entrepreneurs in the UK in the same year accounted for around 9% of all businesses (British Business Bank, 2019). In Turkey, according to data from 2019, the share of ethnic-origin businesses in total number of businesses is 4.4%, and the employment rate of those businesses is 6.2% (Turkish Statistical Institute). The studies conducted in various countries indicate that the contribution of ethnic entrepreneurship to the economy is important. However, beyond financial data, factors such as employment generation, local economic development, and social integration should be considered in the contribution of ethnic entrepreneurs to the economy.

Ethnic entrepreneurship is a complex and multi-dimensional phenomenon that impacts various communities in different regions (Guerra-Fernandes et al., 2022, p. 397). Ethnic entrepreneurs are business owners who focus on their ethnic groups and often specialize in a particular industry (Sowell, 1981). It is seen that some ethnic groups have higher business establishment rates than others, especially among first- and second-generation migrants (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 113). Portes (1995) emphasizes that the economic activities of ethnic entrepreneurs are important for social and economic development. The success of ethnic entrepreneurs depends on both their personal abilities and the quality of the social and cultural networks within their community. In this sense, ethnic entrepreneurs contribute to the economic development of both their ethnic groups and society (Light & Rosenstein, 1995; Sowell, 1981). Considering the discussions on ethnic enterprises, three different approaches can be suggested for defining the resources of ethnic entrepreneurship success; first are the traits that migrants bring with them and that predispose them to carry out good business; the second is the importance of opportunity structure as a prerequisite for business success; third are ethnic strategies that emphasize the interaction between newcomers’ opportunities and ethnic group characteristics (Waldinger, 1989, p. 49). In this sense, it is important to focus on social, structural, and cultural conditions, as higher levels of entrepreneurship cannot only be explained by the personal characteristics of the owners (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 113).

Mixed embeddedness and the interactional model are two concepts that offer different perspectives in explaining ethnic entrepreneurship. The first person to use and explain the concept of mixed embeddedness was Ivan Light. To explore ethnic entrepreneurship, Light introduced the concept of mixed embeddedness in a study published in 1984 titled Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Koreans in Los Angeles, 1965–1982. In this study, it is emphasized that ethnic entrepreneurs are embedded both in their ethnic communities and in the surrounding society, and this mixed embeddedness shapes ethnic entrepreneurial activities. The interactional model is one of the main approaches used to explain the entrepreneurial success of an ethnic group, and it was based on a study titled Structural Opportunity or Ethnic Advantage? Immigrant Business Development in New York by Waldinger (1989). Later, it was developed with a study titled Ethnic Entrepreneurs: Immigrant Business in Industrial Societies by Waldinger et al. (1990). This approach explains the road map that an ethnic group follows in business development. Accordingly, it is said that there is not one single feature responsible for the entrepreneurial success of ethnic entrepreneurs; moreover, success pertains to the interaction between the opportunity structure and ethnic group characteristics.

Mixed embeddedness model is a theoretical approach that is used to explain and determine ethnic entrepreneurship in the social sciences (Kloosterman & Rath, 2001; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Rath, 2001; Rath & Kloosterman, 2002; Ram et al., 2017). This model argues that ethnic entrepreneurship does not arise solely from individual or environmental factors, but occurs as a result of the interaction of these factors. Mixed embeddedness suggests there are three main factors that determine ethnic entrepreneurship: ethnic networks, institutional environment, and the personal characteristics of entrepreneurs. These factors interact with each other and have a decisive effect on the nature and success of ethnic entrepreneurship. Ethnic networks refer to the families, friends, colleagues, and other social relationships of ethnic entrepreneurs. These networks provide entrepreneurs with business ideas, resources, customers, and markets. Institutional environment refers to external factors that directly or indirectly affect the business activities of ethnic entrepreneurs such as judicial, political, and economic institutions. Personal characteristics of entrepreneurs include factors such as abilities, skills, education, experience, motivation, and cultural identity.

Waldinger’s interactional model suggests that environmental factors as well as the characteristics of ethnic groups have an effect on the development of ethnic entrepreneurship. According to this model, the success of ethnic entrepreneurs depends on both the characteristics of their ethnic groups (e.g., cultural capital, social networks, language skills, etc.) and environmental factors (e.g., market conditions, government policies, legal regulations, economic situation, etc.). Waldinger’s interactional model addresses three main components of ethnic entrepreneurship: ethnic group characteristics, individual entrepreneurial characteristics, and entrepreneurial opportunities. In the interactional model, Waldinger emphasizes that the harmony between these components is important for the success of ethnic entrepreneurship. Ethnic entrepreneurs develop their personal entrepreneurial characteristics by using the resources and support from their ethnic groups. When entrepreneurial opportunities are combined with ethnic group characteristics and the conditions provided by the economic environment, ethnic strategies are formed and this increases the success of ethnic entrepreneurship.

There are some nuanced differences between these two concepts. Mixed embeddedness emphasizes ethnic networks as an important factor that affects ethnic entrepreneurship. Ethnic networks usually aspire to solidarity and mutual benefit within the ethnic group, such as solidarity, support, and resource sharing. These resources include the resources that people within ethnic groups share with each other, such as business opportunities, financial support, knowledge, and experience. Interactional model suggests that social capital plays a notable role in ethnic entrepreneurship. Social capital includes elements such as social networks, contacts, connections, and access to individuals’ social resources. Mixed embeddedness discusses the institutional environment as another factor that affects ethnic entrepreneurship. Institutional environment includes judicial, political, and economic factors and analyzes the external factors that affect entrepreneurs’ business activities. Interactional model emphasizes that entrepreneurial activities are shaped as a result of the interaction of individuals’ ethnic identity and social capital with the economic environment. Mixed embeddedness considers how the personal characteristics of entrepreneurs affect ethnic entrepreneurship. However, interactional model emphasizes that individuals’ ethnic identity, comprised of ethnic belonging, cultural values, language, and traditions, may shape entrepreneurial actions.

These analytical approaches represent the frameworks used to explore the different factors and relationships of ethnic entrepreneurship. While the mixed embeddedness approach offers a more comprehensive perspective, interactional model provides a more specific focus and emphasizes the interaction of individual factors. Both approaches are important theoretical instruments to explain the phenomenon of ethnic entrepreneurship. However, interactional model is preferred in this study because Meskhetian entrepreneurs establish social and cultural relationships with family members left in the country they came from; however, they also establish commercial relationships with local networks in the country they migrated to for reasons such as physical distance, cost, and quality. It is also seen that Meskhetian Turks, who initially established their own businesses, especially in the logistics sector, learned about the business from the experience of Russian and Bosnian friends, from different ethnic origins (taking advantage of language and religion similarity), who shared the establishment and operations process and knowledge acquisition to get them started. In other words, social capital plays a remarkable role. Moreover, the Meskhetian Turks then taught the business to close family members, relatives, and friends from the same ethnic origin after they established their businesses and supported them to establish their own businesses; namely, they benefited from ethnic networks as an ethnic business strategy for the future.

In light of that data, the following research questions are discussed in this study:

How do personal characteristics, such as motivation, willingness to take a risk, and self-sufficiency, interact with the cultural, social, and economic factors and shape the entrepreneurial tendencies of individuals from different ethnic backgrounds?

What are the economic opportunities or challenges that affect the entrepreneurial tendencies of individuals from different ethnic backgrounds?

What are the social network and social resource factors that support or prevent the entrepreneurial activities of individuals from different ethnic origins?

Adopting and developing policies that promote ethnic entrepreneurship by local governments plays a remarkable role in increasing entrepreneurship and achieving significant economic, social, and cultural gains for the regions benefiting from ethnic entrepreneurs. In addition, the fact that local governments determine what works by evaluating the effect and effectiveness of the gains from ethnic entrepreneurs for the region and then share that information with the public will provide significant support to better benefit from the entrepreneurial skills or entrepreneurial spirit of hundreds of communities in the USA.

In conclusion, this study offers a framework that specifically discusses ethnic entrepreneurship and analyzes the business opportunities and resources of immigrant communities. In this context, this study indicates that the interaction of ethnic entrepreneurs with local communities, the role of entrepreneurs in local economic development, the opportunity structure of business establishment motivation and growth potentials, and the ethnic and non-ethnic social networks that emerge from the interaction of group characteristics are important.

The course of this study can be outlined as follows: The existing literature was reviewed by addressing the discussions within the framework of conceptual and methodological issues related to ethnic entrepreneurship. In this context, a basic literature review on ethnic entrepreneurship was carried out, and the role of ethnic entrepreneurs and local governments in a region’s economy was included. Afterward, a theoretical framework on the interactional model is presented, which explains what plays a role in the business success of ethnic entrepreneurs in a social, cultural, and economic context. Information about the method of the study and sampling is shared in the methodology section. In the findings section, the obtained findings from in-depth interviews, a qualitative technique, with Meskhetian Turk entrepreneurs operating in Dayton are discussed within the context of the interactional model. Lastly, discussion and conclusions are provided.

2 Role of Ethnic Entrepreneurs and Local Governments in Revival of a City or Region

It is seen in most of the studies on ethnic entrepreneurship that ethnic entrepreneurs are highly important for the revival, renewal, and change of a city or region. It is also indicated that adopting plans and programs to support ethnic entrepreneurs in their local institutions is extremely important for the revival of the local economy. In the city of Dayton, Ohio, USA, where the sample of this study is located, the Dayton City Commission adopted a new “immigrant friendly” plan to attract immigrants and encourage those who are here to prevent job losses and population decline after the industrial recession and to revive the economy and spirit of the city: “WELCOME DAYTON.”

“Welcome Dayton” is an integration initiative and a program established to encourage the adaptation and integration of the local community, immigrants, and refugees in Dayton. The “Welcome Dayton” program aspires to create and support a culture of coexistence based on the successful integration of immigrants, refugees, and local communities, emphasizing that Dayton is a city of people with diverse cultural, economic, and social ethnic backgrounds. The program includes activities such as providing services for immigrants and refugees; increasing the cooperation and communication between local governments, institutions, and communities; reducing the difficulties that immigrants and refugees experience; and inspiring the entire community to celebrate this cultural richness (https://www.daytonohio.gov/998/Welcome-Dayton). Similarly, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2021) discusses how public policies and programs may support inclusive entrepreneurship in its report titled The Missing Entrepreneurs 2021. The report discusses reducing disincentives for business establishment; facilitating access to finance; development of immigrants’ entrepreneurial skills through training, coaching, and mentoring; strengthening entrepreneurial culture and networks for target groups; and aggregating strategies and actions for inclusive entrepreneurship accordingly.

Immigrants and refugees may know a craft or how to trade very well, but they may not be familiar with business establishment processes such as registering the business and concluding contracts when starting a business in the country of immigration, related regulations, the business permission process, and local regulations that may affect a particular type of business. In addition, they may not have a credit history, which prevents them to gaining access to capital. These barriers are combined with linguistic and cultural differences. In this sense, the purpose of the Welcome Dayton plan is to “identify and support a strategic neighborhood business district as a center for immigrant businesses desiring to collocate in a commercial or industrial node.” The plan also aspires to “help ease the burdens/reduce the barriers for anyone who wants to open new businesses in the city serving whomever or wherever. Regarding access to capital, the Welcome Dayton committee has a group focused on small businesses and economic development that, among other things, is concerned with ensuring that people have access to small loans, primarily less than $50,000. Welcome Dayton is encouraging other municipalities and counties in the region to adopt similar welcoming policies, as well as encouraging local governments to adopt more immigrant-friendly policies generally” (American Immigration Council Special Report, 2016). Dayton’s entrepreneurial spirit garnered national recognition, and the US Chamber of Commerce listed the city as one of the top seven business-friendly “entrepreneur cities.”

In addition to the policies by local governments that encourage entrepreneurship, the opportunity to have cheaper housing and the positive attitude of the local people towards immigrants increased the recognition of Dayton. Therefore, ethnic businesses established here, over time, accelerated the region’s population growth and also filled critical labor gaps. According to a New American Economy study, immigrants contributed $1.9 billion to Montgomery County’s (regional municipality mostly inhabited by Meskhetian Turks) economy in 2019, with more than $75 million paid in state and local taxes. The report also estimates that immigrants living in the county had helped create or preserve 1,200 manufacturing jobs that would have otherwise vanished or moved elsewhere by 2019. The report cites similar positives in the entrepreneurial field, estimating that there are 1,100 foreign-born entrepreneurs generating close to $40 million in business income in Montgomery County. Despite making up 4.8% of the population, immigrants made up 7.1% of the business owners in the county in 2019 (American Immigration Council Report, 2016). The success of the entrepreneurial Meskhetian Turks in their enterprises is also an important element of this situation.

In conclusion, businesses owned by ethnic entrepreneurs are important for local economies and provide economic cooperation and cultural diversity among different communities. Local governments that understand the benefit of ethnic entrepreneurs prepare detailed plans/programs for the establishment of ethnic businesses and even play a key role in promoting entrepreneurship by encouraging other local governments in the region to adopt similar policies. In addition, ethnic entrepreneurs are one of the best supporters of the regional economy in terms of attracting foreign investment and pumping their own cash into the local economy through the businesses they establish.

3 An Approach to Explain Ethnic Entrepreneurship: The Interactional Model

The studies on ethnic enterprise emerged in the United States in the last century as part of an attempt to explain historical differences in business activities among African-Americans, Hispanics, and Asians, and it was seen that a mutual interaction played a significant role, especially between the opportunity structure and the characteristics of a group (Waldinger, 1989, p. 48; Waldinger & Aldrich, 1990, p. 49). In addition, the re-experience of mass migration to the USA, increasing importance of small businesses for the USA, significant entrepreneurial success of some new migrant groups, and continuous low self-employment rates among native black people made the ethic trade studies an active field (Waldinger, 1989, p. 48; Waldinger et al., 1990). Light and Rosenstein (1995) emphasize that ethnic entrepreneurship in the United States has many important roles, such as economic growth, business establishment, revival of local businesses, economic diversity, innovation, and preservation of cultural heritage, and state that the existence and contribution of ethnic entrepreneurs in the US economy is a critical factor, especially for small businesses and economic developments in cities.

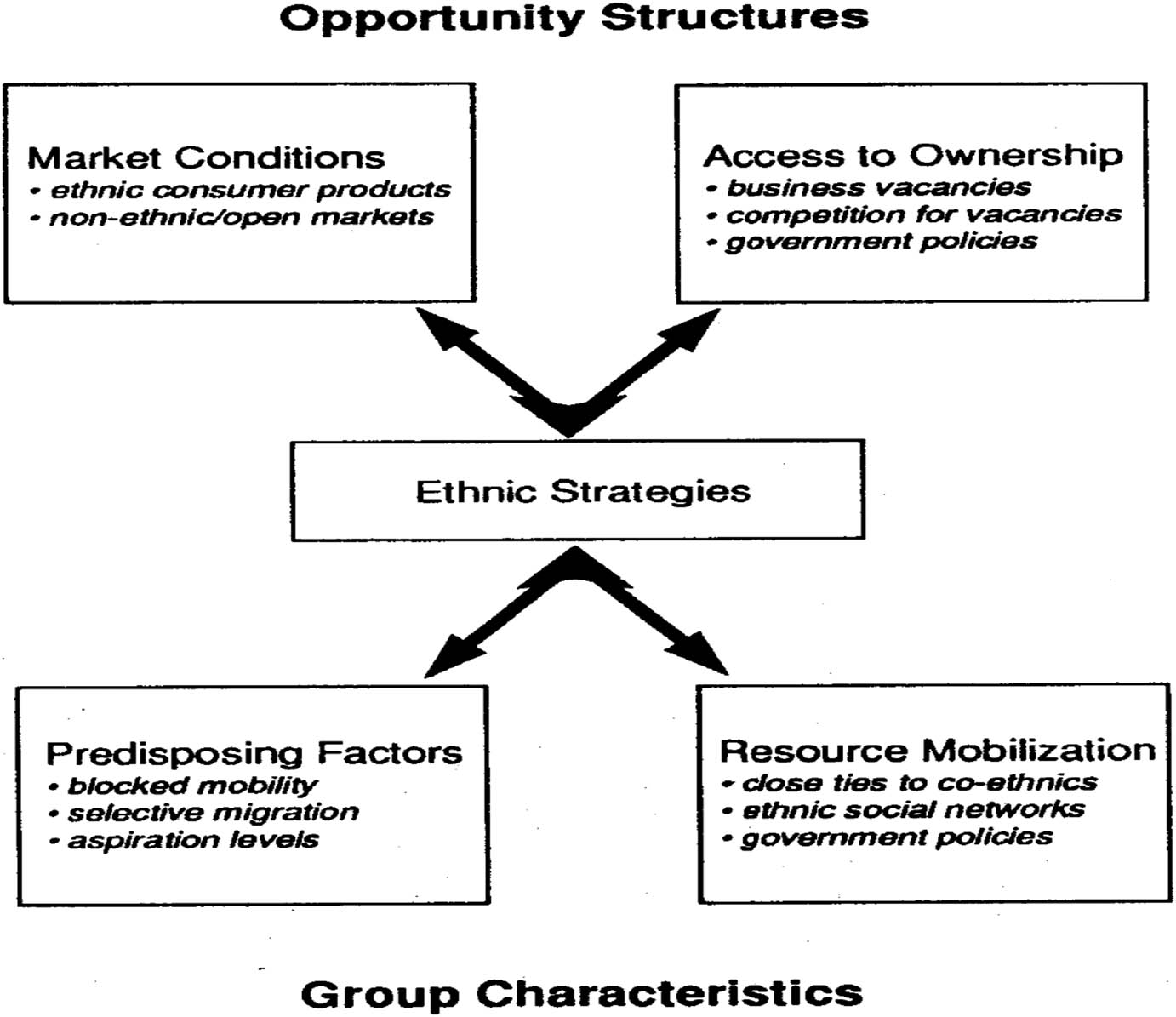

Waldinger Aldrich and Ward (1990, p. 22) developed the interaction model to explain the complexity of ethnic entrepreneurship with a multidimensional approach. The interactional model is based on three components (Figure 1), opportunity structures, group characteristics, and strategies (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990; Waldinger et al., 1990), and it provides an explanation of interactive factors that are required for ongoing operations of ethnic businesses. Accordingly, the interactional model emphasizes that economic activities are resource mobilization through ethnic networks and the interactive consequence of opportunity pursuit. According to the interactional model, the strategies implemented by ethnic entrepreneurs are inclined by both opportunity structure and group characteristics. Opportunity structure consists of market conditions and entrepreneurs’ abilities to access business ownership. Group characteristics depend on entrepreneurs’ predisposing characteristics and resource mobilization abilities.

Interactional model in ethnic business development (Reference: Waldinger et al., 1990, p. 22).

Opportunity structures consist of market conditions that support products or services for co-ethnic groups and the conditions in which a wider non-ethnic market is offered. Opportunity structures also include accessibility to business opportunities, and the access largely depends on the level of competition among ethnic groups and government policies. Group characteristics include predisposing factors such as blocked mobility, selective migration, and aspiration levels. In addition, they include resource mobilization potential and ethnic social networks, general organizational capacity, and government policies that restrict or facilitate resource procurement. Ethnic strategies are the result of the interaction of opportunities and group characteristics as ethnic groups adapt to their environment (Waldinger et al., 1990, p. 114).

According to Fregetto (2004, p. 170), Waldinger et al. state that ethnic strategies come out of the interaction of four factors (Figure 2), and this provides a model to explain the ethnic strategies in ethnic business development as ethnic entrepreneurs use available resources to create their own niches. From this standpoint, the interactional model provides a relational perspective that includes opportunity structure, which includes market conditions and blocked mobility; ethnic community characteristics such as ethnic social networks and close ties to ethnic groups, which contribute to ethnic entrepreneurs’ success; ethnic business strategies, which arise from the interaction between ethnic group and opportunity structure; and settlement characteristics of ethnic entrepreneurs. In this respect, the interactional model offers a framework for ethnic entrepreneurs to see and get opportunities, especially in social, political, and cultural terms.

Interactional model in ethnic business development (Reference: Fregetto, 2004, p. 170).

3.1 Opportunity Structure

The dynamism of the entrepreneurship market depends on a set of intervening variables that influence and shape the interaction between entrepreneurs and opportunity structure. Opportunity structure is the dynamic interaction between entrepreneurs and their social, political, and economic environments that greatly influences entrepreneurial behavior and business success.

It is seen that opportunity structure consists of market conditions in ethnic markets, non-ethnic markets, and open markets with growth potential accessible to newcomers to establish a business (Fregetto, 2004, p. 171). Entrepreneurs expand their businesses to non-ethnic markets after achieving success in services for ethnic settlements (Fregetto, 2004, p. 167). Market conditions merely support the businesses that serve the needs of an ethnic community, and, in this case, entrepreneurship opportunities are limited; or market conditions may support smaller businesses that serve the non-ethnic population, and, in this case, opportunities are much greater (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 114; Waldinger et al., 1990, p. 21). For that reason, the concept of open and closed markets refers to the scope of entrepreneurial opportunities. Access to business ownership by potential ethnic entrepreneurs is majorly determined by the number of business vacancies, the scope of competition for vacancies, and government policies for immigrant entrepreneurs (Waldinger et al., 1990, p. 28).

Ethnically diversified relationships represent a productive foundation for opportunities and innovations, as well as enlarged and open markets, and also provide opportunities for the flow of knowledge and resources (Hartmann & Philipp, 2022, p. 157). The greater the cultural differences between the ethnic group and the host country, the greater the need for “ethnic goods” and a niche market. However, no matter how big a niche market, the opportunities it offers are limited. Access to open markets occupied by local entrepreneurs is often blocked by financial and knowledge-based high-entry barriers. However, not all industries in Western economies are characterized by inaccessible accumulation of knowledge (Ramadani et al., 2014, p. 319).

Growth potential of ethnic entrepreneurs’ businesses depends on access to customers beyond the ethnic community. Researchers determined four conditions where small ethnic businesses can grow in open markets: underserved and abandoned markets, markets characterized by small-scale economies, markets with unstable or ambiguous demand, and markets for exotic goods (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 116). Immigrants in the USA and some West European countries populate the core areas of city centers that are not suitable for the technological and organizational conditions of large businesses but work in favor of small businesses and create a productive trading area. This indicates that market conditions can support ethnic businesses where owners of ethnic businesses have a protected market position and external environments often support the entrepreneurs who are eager to take greater risks than normal. In this sense, ethnic entrepreneurs are true entrepreneurs as they take high risks under ambiguous conditions (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 117).

As well as the market conditions, another factor that influences the enterprises of ethnic groups is access to ownership. What influences access to ownership is the level of competition among ethnic groups and government policies (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 117). If the level of competition among ethnic groups is high, ethnic groups either concentrate on the industries limited in number, or they are forced into exclusion and end up completely out of business. Generally, economic exclusion reinforces group adaptation; thus, it increases the concentration of ethnic networks and, therefore, access to group resources (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 118). Planning government policies to support immigrant entrepreneurs in regulations regarding entrepreneurs accelerates access to business markets. For instance, immigrant countries such as the USA have almost no official barriers to the geographical or economic mobility of immigrants and therefore increase the potential business establishment rate for immigrants (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 121).

3.2 Group Characteristics

When immigrant groups from the same countries and regions create entrepreneurial profiles in certain industries and niches and employ people from their own ethnic networks for economic solidarity, they are regarded as “ethnic economies” (Light & Gold, 2000). Waldinger et al. (1990) pointed out that certain ethnic economies are informed by in-group characteristics such as socio-economic background as well as the opportunity structure of the host country. In addition, it is seen that the existence of in-group social networks plays an important role in migration policies, access to business markets and economic resources, in-group employment of the labor force, and other economic activities. In correlation, opportunity structure greatly influences the internal characteristics of the group (Flubacher, 2020, p. 119).

Aldrich and Waldinger (1990, p. 122) determined that group characteristics are a two-dimensional structure, which consists of predisposing factors and resource mobilization. Predisposing factors refer to the skills and targets that individuals and groups bring along to access an opportunity. Resource mobilization means to what extent close ethnic ties and ethnic social networks and government policies help or encourage ethnic entrepreneurship. For instance, lack of language, low educational level, and discriminatory behavior can be mentioned as predisposition factors. Communication networks, unofficial information channels, and special government policies are considered examples of resource mobilization (Masurel et al., 2004, p. 79).

Ethnic entrepreneurs were comprehensively studied for their job-seeking efforts and to potentially provide employment for other members of the same ethnic group (Flubacher, 2020, p. 119). It is seen that some immigrant entrepreneurs prefer self-employment as the only appropriate alternative to the low-paying jobs available in the secondary labor market (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990). This is still valid for many immigrants (Ndofor & Priem, 2011). When immigrants and non-immigrants are compared with regard to self-selected migration and aspiration levels, which are entrepreneurial predisposing factors for immigrants, immigrants have greater risk tendency and aim for economic mobility rather than social status (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, pp. 125–126; Waldinger et al., 1990, pp. 32–33).

Establishing and running a business is a challenging task, and only a minority of owners succeed in keeping the business running. In this sense, it is an important factor that immigrant groups have a resource mobilization capacity to keep pace with the opportunity structure in the USA in their entrepreneurial success (Waldinger & Aldrich, 1990, p. 49). Resource mobilization includes cultural traditions and ethnic social networks. An explanation of cultural traditions is based on the hypothesis that the self-employment of certain groups is a consequence of their particular cultural preconditions (Volery, 2007). Ethnic social patterns consist of kinship and friendship networks organized around ethnic communities and the intertwining of these networks with positions in the economy, location (housing), and society (organizations). In this respect, information is obtained about the role of ethnic entrepreneurs in the raising of capital, employment, relations with suppliers and customers, and about promising lines of business, especially through various indirect ties with their ethnic communities (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 127). The structure of these networks varies depending on the group characteristics. While some groups have more organized families and a high sense of loyalty and liability, others have disorderly families. In addition, some groups have special associations and media that disseminate information. As ethnic groups provide information, the result is often the accumulation or concentration of an ethnic group in a limited number of industries (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 128). Relying on family and ethnic networks as a resource is highly important in entrepreneurial activities. These ties may compensate for many of the disadvantages that ethnic groups experience, especially in a foreign environment (Ramadani et al., 2014, p. 319).

3.3 Ethnic Strategies

Ethnic strategies are a dimension arising from the interaction between opportunity structures and group characteristics, and they are dynamic. Ethnic business owners experience some challenges while establishing and running their businesses. They are: to be trained and to get the skills needed to run a small business; to employ and manage productive, honest, and affordable employees; to manage interactions with customers and suppliers; to survive in tough business competition; and to protect themselves from political attacks (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 130; Waldinger et al., 1990, pp. 46–47). Ethnic strategy is developing certain survival patterns in business life. For instance, a willingness to work long hours for family members and self-employment, forming alliances based on solidarity and loyalty with relatives, and informal financing of business investments (Masurel et al., 2004, p. 79). Thus, the missing family ties increase the need to develop non-family ties for social and economic support. Light (1972) defines this situation as “immigrant brotherhood” (Fregetto, 2004, p. 167).

It is seen in many studies that people use their social connections to support their business establishment attempts (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986; Chand & Ghorbani, 2011; Jan, 2017; Martinez & Aldrich, 2011; Ndofor & Priem, 2011; Portes & Zhou, 1992; Volery, 2007; Zhou, 2004). Ethnic networks are based on the employment of the members of ethnic groups in businesses owned by the same ethnic groups, setting up their own business with the support of partners from the same ethnic group, and providing opportunities for purchasing and/or supplying ethnic goods and more (Waldinger, 1994). In addition, ethnic networks play an important role in the location selection process of businesses for their activities, eliciting market information, and reinforcing the residence (Bagci et al., 2022, p. 202).

Individuals’ desire to be successful in life leads them to deal with activities based on their cultural values, information, awareness, and personal appreciations, and to often make choices through creative processes when markets are ambiguous (Rath & Swagerman, 2016). Training and skills are typically obtained on the job within ethnic groups, often while working in the business of a potential owner from the same ethnic group or family member. Family and working with people of the same ethnic origin are crucially important for many small ethnic businesses. This type of labor force is mostly cheap and corresponds to working long hours in the service of employers (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 130).

What makes immigrant entrepreneurs different from resident entrepreneurs is their access to labor markets in business activities (Valenzuela & Solano, 2022, p. 173). The existence of social networks based on common origin can be used as a functional tool for overcoming challenges in the local labor market with solidarity and mutuality. In addition, such networks reduce individual or collective experiences of discrimination and exclusion and facilitate access to information, capital, and organizations (Flubacher, 2020, p. 119).

It is seen that ethnic entrepreneurs seem to be able to adapt to business markets more quickly in terms of starting and growing businesses and play an important role in establishing small businesses. Portes (1995) states that ethnic entrepreneurs’ immigration experiences and ethnic networks have a positive effect on their entrepreneurial activities. In ethnic entrepreneurship, social capital and social networks play a remarkable role in establishing, growing, and sustaining businesses (Karadal et al., 2021, p. 1587). Aldrich and Waldinger (1990) state that ethnic entrepreneurs have a strong local network in society, and most of their business strategies are based on these networks. In the following section, information about the method of study will be given.

4 Method

4.1 A Brief History of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA

It is known that many nations in the world were exposed to exile in different eras. While Meskhetian Turks were living in the Meskhetia region, which is in the northeast of Turkey and within the borders of Georgia today, the region came under Russian domination in 1829; they were exiled to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan in 1944 by Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union at that time; and no Turks were left on these lands (Aydıngün et al., 2006; Buntürk, 2007; Kolukırık, 2011; Sakallı, 2016).

Meskhetian Turks living in Uzbekistan had to leave and migrate to other lands as a result of the events that happened in Fergana in 1989. Troubles for Meskhetian Turks, who started to live in different regions of Russia with this second migration, continued there as well. Meskhetian Turks who moved to live in the Krasnodar Krai region of Russia were exposed to serious discrimination. They were not given residence and work permits, and they were deprived of the most basic right to life (Aydıngün et al., 2006).

In October 2003, the US Department of State included Meskhetian Turks in the Proposed Refugee Admission Report for the 2004 Fiscal Year, which was submitted to Congress, and declared that Meskhetian Turks from the Krasnodar Krai region of Russia would be admitted to the United States. As a result of studies supported and carried out institutionally and individually, more than 10,000 Meskhetian Turks migrated to the USA (US Department of State). Meskhetian Turks with a population of more than 400,000 in total live in nine different countries in the world today (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and the USA), and their living conditions vary according to the places they live in (Ozözen-Kahraman & Ibrahimov, 2013). The most populated region of Meskhetian Turks who are living in various states of the USA is Dayton, Ohio. Today, around 2,500 Ahiska Turks are thought to reside in the Dayton area.

4.2 Research Method

One important source of ethnic entrepreneurship information is conducting interviews and collecting the required data to better understand certain skills used by ethnic entrepreneurs for their businesses (Crouch & McKenzie, 2006). When the literature on ethnic entrepreneurship is examined, it is seen that studies were mostly carried out in developed countries and the qualitative approach is predominantly used in entrepreneurship studies (Indarti et al., 2021). The qualitative approach enables individual entrepreneurs not only to discuss entrepreneurial activity but also to examine the entrepreneurial context, including the sociocultural environment (Dana, 1995, p. 58). Since no study is found on the field of business management/entrepreneurship in international literature about Meskhetian Turks, the qualitative approach in this study can provide new information for ethnic entrepreneurs to determine a road map in entrepreneurship because Meskhetian Turks present different migration experiences for society, as they had to migrate constantly, beyond normal migration.

4.3 Sample Selection

The sample for this study consists of Meskhetian Turks who practice entrepreneurial activities in Dayton, Ohio, USA. This region was selected as it is the most densely populated region of Meskhetian Turks in the USA. First of all, an interview was conducted with Islam Shakhbandarov, the Chairman of the Ahiska Turkish American Community Center in Dayton. The earliest information about the details of the study area was obtained from him, and his permission and help for getting started were requested. Through this early interview, we got preliminary information to identify the nature of business activities, business categories, and enterprises in the field of study, and it was identified that a majority of the entrepreneurs are active in the logistics sector, and some of them are engaged with enterprises that serve the ethnic market, such as food, restaurants, and clothing.

With the knowledge and approval of the President of the Association, Islam Shakhbandarov, together with the director of the association, Sarvar Ismaylov, the businesses of the enterprising Meskhetian Turks, who are members of the Meskhetian–Turkish American Community Center, were visited in order to reach out and conduct interviews with the enterprising Meskhetian Turks in Dayton. In this context, face-to-face and in-depth interviews were conducted with 15 entrepreneurs, in total, who chose to participate in the study voluntarily. The President of the Association, Shakhbandarov, stated that there was approximately 50 businesses belonging to Meskhetian Turks, who established their own businesses in Dayton, and most of them were in the logistics sector. Due to time and cost limitations (between February 5 and May 2, 2019), research was limited to the 15 entrepreneurs who volunteered to be interviewed and invited us to their business for face-to-face interviews. In this sense, the fact that the study was conducted with only 15 entrepreneurs operating in Dayton creates a limitation for generalizing the results of the study. However, it is our belief that it will be important to provide an idea about the entrepreneurs operating in this region and entrepreneurial processes to reflect on the overall situation in the region.

A field study was carried out between February 5, 2019, and May 2, 2019. Interviews were audio-recorded with the informed and voluntary consent of the entrepreneurs. Qualitative data such as structured, semi-structured questions, and observation were used in the interviews, which were carried out face-to-face at the entrepreneurs’ workplaces upon appointment. Therefore, entrepreneurs were observed in their workplaces. The interviews with entrepreneurs lasted between 30 min and 3 h, and they were carried out during working hours. Open-ended questions were asked of the entrepreneurs about their life experiences and successes, their decision-making process for self-employment and their sources of motivation, the sector they entered in the market, the details of their business and the structure of the market, their relationships with suppliers and how they employed employees, and any other social and political issues. The results were evaluated in the context of the interactional model developed by Waldinger et al. (1990). In addition, the entrepreneurs were also asked for some operational information, such as how many years their businesses have been active, how much capital was needed to get established, its average annual income, and number of employees. The participants’ interest, helpful attitude toward the study, and their hospitality were pleasing and made for a comfortable and productive interview atmosphere.

4.4 Characteristics of Entrepreneurs and Their Businesses

In Table 1, below, the demographic information of the entrepreneurs has been given according to the sector distribution. Then, the information about the characteristics of the entrepreneurs’ businesses has been given according to the same sector ranking.

Demographic Information about Entrepreneurs

| Sector | Gender | Marital Status | Age | Educational Level | How many businesses have you established in the USA? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clothing | Female | Married | 51 | High School | One |

| Clothing | Female | Married | 35 | Associate (Healthcare) | One |

| Restaurant | Female | Married | 48 | High School | One |

| Furniture | Male | Married | 32 | High School | Two |

| Accounting | Female | Married | 34 | Associate (Accounting) | One |

| Health | Male | Married | 37 | Associate (Banking) | Two |

| Marble/Ceramic | Male | Married | 30 | Bachelor (Banking and Finance) | Two |

| Used car Trade | Male | Married | 56 | Associate (Artist) | One |

| Auto interior design | Male | Married | 53 | Associate (Tailor) | One |

| Logistics | Male | Married | 33 | High School | One |

| Logistics | Male | Married | 37 | Bachelor (Computer) | One |

| Logistics | Male | Married | 38 | Associate | One |

| Logistics | Male | Married | 49 | Bachelor (Physical Education) | Two |

| Logistics | Male | Single | 23 | High School | One |

| Logistics | Male | Single | 23 | High School | One |

Accordingly, it is seen that the majority of entrepreneurs in Table 1 are male and married. As for educational level, it is seen that the majority of participants have a higher education degree. As for the age variable, it is seen that entrepreneurs are in the young and middle-age range, and the majority of them established a business for the first time. The entrepreneurs who established their second businesses stated that their first business was in the logistics sector, and they transferred the business to one of their family members and established the second business in a different sector.

Characteristics of entrepreneurs’ businesses are given in Table 2.

Characteristics of Entrepreneurs’ Businesses

| Sector | Market Type | Active Year | Capital/Dollar | Average Annual Income/Dollar | Number of Employees | Customer Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clothing | Ethnic/Closed | 4 | 10,000 | 70,000 | 4 | Mostly Turkish |

| Clothing | Ethnic/Closed | 1 | 150,000 | — | 2 | Mostly Turkish |

| Restaurant | Ethnic/Closed | 3 | 57,000 | 128,000 | 3 | Mostly Turkish |

| Furniture* | Ethnic/Closed | 2 | — | — | 5 | Mostly Turkish |

| Accounting | Non-ethnic/Open | 5 | 10,000 | 100,000 | 1 | Mostly Turkish |

| Health* | Non-ethnic/Open | 5 | 35,000 | 600,000 | 60 | Mostly native |

| Marble/Ceramic* | Non-ethnic/Open | 2 | 500,000 | 1,400,000 | 10 | Mostly native |

| Used Car Trade | Non-ethnic/Open | 7 | 10,000 | 100,000 | 2 | Mostly native |

| Auto Interior Design | Non-ethnic/Open | 6 | 30,000 | 70,000 | 3 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 7 | 45,000 | 150,000 | 3 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 6 | 60,000 | 2,500,000 | 14 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 7 | 30,000 | 150,000 | 4 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 5 | 100,000 | 250,000 | 2 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 7 | 30,000 | 220,000 | 3 | Mostly native |

| Logistics | Non-ethnic/Open | 5 | 60,000 | 400,000 | 3 | Mostly native |

*Enterprises with an asterisk next to them are second businesses established by their owners. The first businesses established by these entrepreneurs are in logistics.

It is seen that the businesses of entrepreneurs in the sample operate in both ethnic and non-ethnic markets. From the interviews with the entrepreneurs, it was discovered that the first customers of the entrepreneurs operating in other fields apart from the logistics sector initially consisted of people from their own ethnic origin; however, the natives in the region were included in the customer portfolio over time. Moreover, the majority of entrepreneurs’ customers in the ethnic market consist of their own ethnic origin, and the majority of entrepreneurs’ customers in non-ethnic market consist of natives. Most of the entrepreneurs, except for the ones in the marble/ceramic and auto interior design sectors, engage with businesses in the service sector (Table 2). Except for one of the companies focusing on the study (health services), the others are in the status of micro and small-scale enterprises, and according to the information obtained from the interviews, it is seen that they grew over the years. While most of the employees in these businesses are family members or relatives, it is seen that the employees for entrepreneurs’ businesses with more than 10 employees are a mix of other ethnic origins and natives, as well as family members.

Since this sample consists of enterprising Meskhetian Turks who settled in Dayton, it is important to not generalize the following findings to account for the rest of the USA and other countries, because opportunity structure and ethnic group characteristics may not be the same in other places.

5 Enterprising Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA: A Practice in Dayton

The data obtained from the interviews with enterprising Meskhetian Turks indicate that the interactional model ideally explains ethnic business development. The obtained findings are evaluated in the context of the interactional model and are detailed in the remaining part of the article.

5.1 Opportunity Structures

Opportunity structure for ethnic entrepreneur Meskhetian Turks is initially determined according to market conditions. Access to ownership factors, which is another dimension of opportunity structure in the interactional model, is not included among the factors that influence the competence of many entrepreneurs to establish a business. The large and demanding US market may positively affect this situation. In addition, it is seen that government policies in the country had no adverse effect during the ownership process of Meskhetian Turks; on the contrary, they supported and encouraged all entrepreneurs.

5.1.1 Market Conditions

Entrepreneurs who participated in the study participated in both market conditions and continued both their ethnic consumption of goods in the ethnic market and their entrepreneurial activities in a non-ethnic/open market. Even most of the entrepreneurs stated that they were engaged in entrepreneurial activities in different fields, especially in logistics, in a non-ethnic/open market and that they did not see any restrictions or barriers in their enterprises.

5.1.1.1 Non-ethnic/Open Market

A majority of enterprising Meskhetian Turks operate in a non-ethnic/open market, and all of these businesses except for one of them (health services) are micro- and small-scale enterprises. Of the interviewed businesses in the non-ethnic market, six operate in logistics, one in healthcare, one in marble/ceramic, one in the used car market, one in auto interior design, and one in the accounting sector. While most of the businesses operate in the service sector, only two of them (marble/ceramic and auto interior design) are in the manufacturing sector. While initial commercial activities of ethnic entrepreneurs mainly aim to serve the needs of the sociocultural or ethnic class to which they belong, it is seen that market areas expand to a much broader scope of urban demand over time (Masurel et al., 2001, p. 3). Some of the entrepreneurs explain this issue as follows: First, we entered the logistics with my cousin (son of my uncle) together; however, our business grew over time. We have big families and my brother deals with the logistics now and I established another business on ceramic/marble. Hearing it, people from our nation said, “Make the kitchen of our house, too.” We both do it cheaper and we are relatives, not foreigners. Employees are American. We designed the kitchens of our families in the first of establishment, now most of our customers are natives and new builders. Another entrepreneur said: I left the logistics to my brother and I established another business related to healthcare services. I have almost 60 employees here and most of them are natives. In first years of the business, we were engaged in healthcare services of elders of the families from our own origin; however, our customer profile is now natives. Another entrepreneur stated: If you decide what to do, if you know how to work and how to use a computer and if your credit score is good, there is no obstacle to being an entrepreneur in the USA.

While customers or suppliers carry out local activities when they are in the same country with entrepreneurs, they can also carry out transnational activities such as export/import enterprises or international consultancy when they are in different countries from the entrepreneurs (Valenzuela & Solano, 2022, p. 172). Immigrant entrepreneurs may stay in contact with their homelands and other countries by carrying out transnational activities (Ambrosini, 2014) to purchase the goods they will supply to meet the local ethnic needs. On this issue, an entrepreneur said: Clothes in the US were not suitable for our culture and everyone wanted me to buy clothes for them when I came to Turkey. I had my own business in Russia, and later, I decided to do my own business here. I established my own business on clothing and home textile and I brought the goods from Turkey. This corresponds to the statement by Masurel et al. (2001, p. 3) that ethnic entrepreneurs have great potential for business organization between two cultures and two countries. However, it can be said that this may not be true for non-ethnic goods in a non-ethnic market because transnational activities for entrepreneurs should not increase both the cost liability due to physical distance and the cost according to the comparative advantages theory. Transnational activities may not be preferred by entrepreneurs if the goods to be traded are not in the category of non-substituted, rare, or valuable goods. One of the entrepreneurs spoke on this issue as follows: After we succeeded in the business in logistics sector that we partnered with my cousin, we decided to establish a business on marble. In the beginning, we worked with some companies from Turkey; however, we had problems in price and quality. We did not have any problems in orders from Europe and Central Asia. Packaging, package quality, barcode etc. were up to American standards; however, shipping costs increased then. For that reason, we supply the material here. I pay a bit more when I buy here, but it is more reasonable because I buy by seeing and touching. In addition, in case of defective product, they replace it or bring a new one.

It may be necessary to have specific training or professional expertise or experience to establish a business in some non-ethnic/open market enterprises. An entrepreneur who established his own business in auto interior design spoke on this issue as follows: I have been in this business since 1986. I studied tailoring for 3 years in Uzbekistan and I established my first business there. Then, when we were exiled to Russia, I did the same business there; however, I could not establish my own business because we had no identity cards and residential permits. In the USA, we firstly came to Idaho; however, I did not have the language proficiency to establish my own business. I worked with a Russian translator as a worker for someone else for 8 years. Here, I worked on tailoring and sewing of ship and vehicle seats. We settled in Dayton in 2012 because majority of our nation were here. I established my own business in Dayton and now I do the business related to my profession. Another entrepreneur stated as follows: I worked in a factory for 3 years when I first came to the USA; however, my wage was not enough for living. For that reason, I bought cars from the auction, repaired and sold them. Later on, we decided with my son to establish our own business and we purchased this shop. My son handles government correspondence. I buy old or crashed cars and then repair, modify and sell them. I learnt to repair cars in Uzbekistan. If I employ a master, I could not earn money. Another entrepreneur said as follows: I finished the accounting department in university. I used to work for someone else. I decided to establish my own business and I left that job. Almost all of my customers are Turks as we can freely speak with Turks. However, in order not to make mistakes, I exchange information with American experts.

5.1.1.2 Ethnic Consumer Goods Market or Ethnic/Closed Market

One-third of the interviewed entrepreneurs are mostly engaged in businesses that appeal to their ethnic origin. Two of them are in the clothing sector, one of them is in the furniture sector, and one of them is a restaurant. The entrepreneurs in the ethnic/closed market declared that they had customers only from their ethnic origin in the beginning; however, their costumer group diversified over time to a certain extent, consisting of Middle Eastern, Central Asian, Arab, and native customers. Most of the products in the ethnic market consist of retail ethnic goods exported from Turkey and Russia. These entrepreneurs declared that they do not experience much competition as there are not many entrepreneurs with similar businesses in Dayton. The following quotes from these three entrepreneurs confirm it: We brought the goods from Turkey. Sofa sets or furniture are sometimes specially requested by our own nation. We have Uzbek, Arab, and Central Asian customers apart from Meskhetian Turks. Another entrepreneur said: We brought the goods from Turkey. We appeal to all people but we usually have Indian, Arabic, and Turkish customers. Another one said: My husband was a cook in his military service and I established this business through his supports. It was 3 years ago. My husband and daughter help me here. In the beginning, only the contacts from our ethnic origin were our customers. I prepared dishes for their special days. Now we have customers from all nations.

5.1.2 Access to Ownership

The government policies defined in the interactional model had a positive and significant role here. The situations of business vacancies and competition for vacancies are not relevant for enterprising Meskhetian Turks. The government policies, subsidies from the USA for entrepreneurs, fast-track bureaucracy, tax advantage, and even advantages such as no requirement to be a citizen of this country in order to establish a company within the borders of the USA can be appreciated as positive factors for anyone who would like to be an entrepreneur in the country, not only for Meskhetian Turks. It is seen that government policies also encourage entrepreneurs. The following quotes from four entrepreneurs confirm it: In the USA, there is an institution called as small business administration, which is a government-sponsored institution for small entrepreneurs. You apply to the institution with the business plan, it is examined and you are given loans with low interest rate. Another one said: It is easy to establish a company in the USA. You get loans easily here and establish your own business; however, you have to be very careful about the rules here. You have to do everything according to the rules and on time. Another entrepreneur said: They guide you to establish a business in the US. When we were new in our business, a Bosnian woman came to help us. She helped those who were new in business. She also helped us about the issues on business. Another entrepreneur said: Here is a free country. We are not exposed to discrimination in our business. We can freely establish our business and work. We carry goods to many states in the US and we have no problem. Another entrepreneur said: We want to invest in the places where we are accepted better, and we are accepted better in Dayton.

5.2 Group Characteristics

It is seen that wealth, success, and values related to personal admission are dominant in group characteristics, and they facilitate entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial processes include the characteristics of an ethnic culture or originate from ethnic values. Many ethnic entrepreneurs establish their own businesses within an ethnic customer network and entrepreneurial activities may have a social, political, and cultural context (Morris & Schindehutte, 2005).

Group characteristics consist of predisposing factors and resource mobilization. Predisposing factors include blocked mobility, selective migration, and aspiration levels, and resource mobilization includes close ties with ethnic groups, ethnic social networks, and government policies. While the fact that Meskhetian Turks populated and created a residential area in Dayton and tended toward entrepreneurship are the predisposing factors for Meskhetian Turks, it is found that close ties with an ethnic group and ethnic social networks are important under the title of resource mobilization.

5.2.1 Predisposing Factors

Waldinger et al. (1990) pointed out that certain ethnic economies are informed by in-group characteristics such as socio-economic background as well as the host country’s opportunity structure. It is seen that in-group social networks play an important role in migration policies, access to the labor market and economic resources, in-group employment of the labor force, and other economic activities. Consequently, opportunity structure mutually affects the in-group characteristics (Flubacher, 2020, p. 119). Accordingly, characteristics of their settlement and aspiration levels will be discussed as predisposing factors for Meskhetian Turks.

5.2.1.1 Characteristics of Settlement and Entrepreneurial Tendencies

The location of a business is a highly important issue, as well as the nature of business activities. When immigrant groups from the same country or region develop entrepreneurial profiles in certain sectors or niches and hire people from their own ethnic networks for economic solidarity, they are considered “ethnic economies” (Light & Gold, 2000). Ndofor and Priem (2011) indicate that capital equipment and social identity of immigrant entrepreneurs influence their choice of location against the dominant market enterprise strategy. One of the interviewees stated as follows: When we first came to the USA, we lived in other states but we learnt that they settled to Dayton in years and established their own businesses and supported each other in every respect by living together. So we settled to Dayton too, and we established our own business. Another entrepreneur stated as follows: You just need capital to establish, buy or invest in a small business; other than that, they do not ask for a diploma or anything else. Just do your job. However, if you want to establish a big business, you need both diploma and bigger capital and a good command of English. Here most of Meskhetian Turks do logistics business because Dayton is right in the center for logistics, and it is a long transfer point connecting the east and the west. In the beginning, we worked for someone else but taking orders is not for us. We learnt logistics and began to do own our business.

Ethnic housing density provided a strong consumer core for many ethnic entrepreneurs, especially for immigrant groups in the first decades of their settlement in the host country. Since immigrants clustered in cities in the beginning, a long-term dense population occurred, and this facilitated employment networks for ethnic suppliers and workers (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 115). In addition, an increase in the number of ethnic people in urban areas indicates a contribution to a multiform and multicultural society, renewal of generations, and an increased income especially in these areas (Baycan-Levent et al., 2003). Although settlements are similar to the local ethnic market in terms of spatial concentration and hiring from their own ethnic networks for economic solidarity, they differ in two respects. First, the industrial structure of the settlement is diversified beyond “local economy” industries, which are the characteristics of a local ethnic market. Second, the industries of the settlements are also connected with general markets, i.e., non-ethnic markets. For that reason, population sizes and densities are necessary and sufficient for local ethnic markets but not sufficient for ethnic settlements (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990, p. 123). Accordingly, the fact that the Meskhetian Turks, populated in Dayton, would only engage in activities in the ethnic market would have caused both intense competition and the continuous existence of a limited number of small businesses by not taking advantage of the opportunities in the country. On the contrary, the fact that the Meskhetian Turks have group characteristics, which provide a strong tendency towards business ownership, the abundance of entrepreneurship opportunities in the country, and the advantages of their location, especially for entrepreneurs operating in the field of logistics, played an important role. In addition, the business activities of enterprising Meskhetian Turks in non-ethnic markets contribute to their trading with the natives in the country and those with other ethnic origins, thereby expanding and developing their businesses. The following quotes from interviews with entrepreneurs confirm it: We have a business on logistics and we are one of the first 2-3 companies to do this business in Dayton. Most of Meskhetian Turks in Dayton do this business because Dayton is located in the heart of the Midwest in a very important location for logistics. We easily supply goods from large centers such as Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, Indianapolis, and Pittsburg. Another entrepreneur stated as follows: I do logistics with my brother. There is such a large market for this business that someone who does it in Chicago is not a threat for someone who wants to do it in Dayton. In addition, in addition, we do not see our own nationalities doing this job in Dayton as competitors because the market is huge. Another entrepreneur said: Most of Meskhetian Turks in Dayton do this business because no special education or certificate is needed to do this business. Those who are 21 years old and have a license to drive a truck can become a driver. You just have to speak English fluently with suppliers to purchase goods. We have acquaintances, which came here from other states because Dayton is situated in a critical point for this business and most of us are successful here in logistics business. A common point for the entrepreneurs, even in different sectors, is their tendency for entrepreneurship. The quotes on this issue are as follows: Being free motivates me and I feel happier when I do my own business. In fact, you take more responsibility but you do not take orders from anybody else, you act freely and make your own decisions. Another entrepreneur said: You earn more when you do your own business. You control your own business. Doing your own business means both being free and taking responsibility. I do not remember that I sleep for 8 h for 9 years. Another entrepreneur stated as follows: In the beginning, we worked together with our family members but today most of Meskhetian Turks do their own businesses. This means that it is difficult to find people from our own nation. In addition, our businesses grew and now we employ those from other ethnic origin and natives apart from our family members and relatives. These findings are defined as attractive factors, and they focus on the positive aspects of establishing one’s own business by ethnic group members. Attractive factors can be counted as more earnings, having the same language, sense of freedom, demographic factors, confidence in ethnic groups, and social capital.

5.2.2 Resource Mobilization

Ethnic resources used by enterprising Meskhetian Turks mainly consist of close ties with the ethnic community and ethnic social networks. Accordingly, ethnic social networks and close ties with ethnic communities had a supportive effect on establishing a business, getting information about the business, raising capital, and labor supply. The details are explained below.

5.2.2.1 Close Ties with Ethnic Community

Heterogeneous ethnic groups with different motivations do not hesitate to try new ways to overcome troubles, even if they are faced with problems to be solved, and tend to establish their own businesses thanks to the support from their own ethnic communities (Masurel et al., 2002). Chaganti and Greene (2002) emphasize that entrepreneurs would rather continue to be involved in their own communities; their communities provide them important human resources for their business, and it is important to establish close ties with the ethnic community to survive.

In terms of entrepreneurship, it is more likely that ethnic immigrants deal with their ethnic communities in host countries than other groups. It is seen that many entrepreneurs state that their close friends and acquaintances are from their own ethnic origin, and they generally prefer to work with people from their own ethnic origin in their business activities. These close ethnic friends and family members provided social support to each other on many issues since they were included in the US society. Many entrepreneurs stated that their families and relatives helped them to establish their businesses. Many entrepreneurs also stated that common ethnic friends and acquaintances helped them in the process of business establishment and development. Moreover, they stated that they founded an association so that they could come together in Dayton to establish close ties and interact with the ethnic community. Thus, Aldrich and Waldinger (1990, p. 129) stated that ethnic organizations, such as churches and volunteer associations, are often supported by ethnic entrepreneurs due to the sense of in-group loyalty as well as commercial reasons. According to the findings obtained from this study, it is found that enterprising Meskhetian Turks trust close family members most for the support, then close relatives, and then friends. The statements from some entrepreneurs are as follows: I was working with my uncle and he taught me the business. In the beginning, I worked with them, but later on, I established my own business. If I have a question about the business, I still call and ask them. Another entrepreneur said: I learnt how to establish a business while working with my friend. I worked with my friend for 1 year, and we established our own business with my cousin. We employed those from our ethnic origin as employees, and we also taught them how to establish a business. Now they all have their own workplace, their own business and employ workers. We are really happy to see it. Another entrepreneur said: We grew in our businesses because we were together and helped each other. I went to friends of my brother’s and asked them how to establish a business. They told me and did not want anything in return. Now my father, brother and I do our business. Another entrepreneur said: I help my cousin and one of the friends of my father’s to supply goods. We did not sign an official contract because we know each other. Another entrepreneur stated: I have very good friends that I have known for 13 years. They are business administration graduates. They informed me about everything on establishing a business. Now they are engaged with accounting and financing. I learnt the fundamentals of the business from them.

5.2.2.2 Ethnic Social Networks

Although the effect of ethnic groups on business probabilities is under the control of the factors related to education, labor force, professional experience, and social status, social networks with the same ethnic origin may offer exceptional opportunities for ethnic entrepreneurs (Evans, 1989). The existence of common-origin-based social networks can be used as a functional tool for solidarity and reciprocity and for overcoming challenges in the local labor market. In addition, such networks provide support for the experiences of individual or collective discrimination and exclusion and facilitate access to information, capital, and institutions (Flubacher, 2020, p. 119).