Abstract

The aim of this article is twofold. First, we analyze whether the decision of where to import from is affected by firms’ ex-ante characteristics. Second, we analyze how the origin of imports affects firms’ productivity, export sales, and the number of export markets. Using extensive data on Swedish manufacturing firms from 2007 to 2020, we uncover several significant insights. Nearly 80% of the firms engage in international trade. The smallest firms operate exclusively as exporters, medium-sized firms as importers, and the largest firms engage in two-way trading. While most imports originate from high-wage countries, there has been a gradual shift to low-wage countries over time. Self-selection is evident, with highly productive firms importing from all sources, followed by firms that exclusively import from either low-wage or high-wage countries, and the lowest-productive firms not importing. By controlling for self-selection using the Event Study approach and difference-in-differences matching estimator, we find that large importing firms exhibit no significant differences in productivity and export sales in comparison to their non-importing counterparts. However, small importing firms show increased productivity growth, driven by high-wage imports. Both small and large firms importing from high- and low-wage countries tend to access more high-wage export markets than non-importers.

1 Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that global trade has significantly contributed to economic growth, particularly in developed countries. Firms of all sizes and sectors have contributed to and benefited from this development. For instance, in Sweden, over 70% of manufacturing firms with a minimum of 10 employees export their products to international markets. Concurrently, it is well-documented that most of the firms, particularly those in small open economies like Sweden, heavily rely on global sourcing, as the production process nowadays is more fragmented and spread around the world. The increasing role of global value chains (GVCs), which enables firms’ involvement in an international network of production, has significantly enhanced the link between the origin of imports and the destination of exports. To effectively engage in the export market, firms need to carefully assess the sources of their intermediate inputs. Participation in GVCs is therefore an important factor in shaping firms’ sourcing decisions, which, in turn, may impact their overall export strategies. Additionally, previous research has highlighted the crucial role of productivity in enabling firms to enter the export market and identify potential export destinations.

Given these circumstances, the present article focus on the link between import, productivity, and export performances in terms of export sales and the number of export markets. The article seeks to address two key questions. First, it aims to empirically analyze how firms’ ex-ante characteristics influence their import decision and their choice between low-wage or high-wage countries or both as import sources. Second, the article aims to analyze whether productivity and export performances differ between firms engaged in importing and those that are not, taking into account various firm-specific characteristics that may affect the outcomes and the geographical origin of the imports.

The data used in this article are from Statistics Sweden (SCB) covering the entire manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees over the period 2007–2020. The register-based information at the firm level is linked to the firms’ foreign trade, disaggregated at the six-digit product level for imports and exports.

Before we start to answer the above questions analytically, however, it is important to provide a comprehensive overview of how firms’ involvement in the international market has developed in recent years. This includes examining the presence of firms active in the international market, whether as importers, exporters or both, and the number of products and different countries from which the intermediate inputs are imported.

Although several international literatures have studied the role of imports in firm productivity and export opportunities, there are still knowledge gaps. The literature, up to date, has focused on the characteristics important for firms to become importers (e.g., Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009; Lewin et al., 2009; Mol et al., 2005), the location choice of the import (e.g., Doh et al., 2009; Rasciute & Downward, 2017), the import effect on different labor market outcomes (e.g., Abramovsky et al., 2017; Bandick, 2016; Feenstra & Hanson, 1999; Head & Ries, 2002; Hummels et al., 2014), or how imports affect firm productivity and other performance (e.g., Aristei et al., 2013; Bas & Strauss-Kahn, 2014; Bertrand, 2011; Elliott et al., 2016; Hijzen et al., 2010; Jabbour, 2010; Smeets & Warzynski, 2013). Nevertheless, as argued by Antràs and Chor (2022) and Antràs et al. (2022), there remains a knowledge gap in understanding how these issues are interconnected. It is reasonable to believe that factors influencing firms’ import decisions and sourcing location may also correlate with firm performance in terms of productivity and export opportunities. Still, even if the decision to import and sourcing location are endogenously driven, firms may also experience improved productivity and export performance ex-post due to learning by doing (Ethier, 1982; Grossman & Helpman, 1991; Markusen, 1989; Young, 1991). However, most of the relatively small number of empirical firm-level studies (e.g., Amiti & Konings, 2007; Aristei et al., 2013; Bas, 2012; Castellani et al., 2010; Kasahara & Rodrigue, 2008; Kugler & Verhoogen, 2009; Muuls & Pisu, 2009; Smeets & Warzynski, 2013) do not explore if there are differences in the learning process between different sourcing locations, and many of them even ignore investigating the direction of the causality, whether it is self-selection, learning, or both.

The learning effect partly originates from the perspective that imports may lead to productivity enhancement by introducing higher quality and more diversified varieties of inputs that are otherwise unavailable in the domestic market. Additionally, importing firms may encounter lower sunk-entry costs for exporting, as they possess a deeper understanding of the export destination, including factors such as language, culture, distribution channels, and networks. Furthermore, the impact of the learning effect on productivity and export depends on the sourcing location. The larger the technology gap between the firm’s home country and the origin of imports, the greater the learning effect, provided that the firms have the capacity to assimilate the advanced technology inherent in the imported inputs (Lööf & Andersson, 2010).

However, empirical findings regarding the presence of the learning-by-importing effect exhibit significant variation across previous studies, as reviewed by Wagner (2012) and further discussed by Fernández and Gavilanes (2017). For instance, Pane and Patunru (2023) find that Indonesian firms utilizing imported inputs in their production process experience enhanced productivity, with a more pronounced effect for inputs originating from developed countries. Elliott et al. (2016) find greater productivity gains among Chinese firms that import from high-wage countries, in comparing to importing from low-wage countries. Feng et al. (2016) show that intermediate inputs from G7 countries prove more advantageous for Chinese firms initiating exports to the same destinations. Additionally, for the Spanish firms, Máñez et al. (2020) show that the import of intermediate inputs increases the likelihood of becoming an exporter, while Díaz-Mora et al. (2015) find positive export survival rates for small firms that source inputs from abroad. Requena et al. (2023), also investigating Spanish firms, found modest export increase for those firms utilizing imported intermediates from non-EUEFTA countries, while sourcing high-quality inputs, regardless of the income level of the country, contributed to enhancing Spanish firms’ exports to the EU15. Bas and Strauss-Kahn (2014) examine French firms and find that imported inputs from developed countries augment productivity levels and exports, whereas inputs from developing countries only increase productivity levels. Conversely, Jabbour (2010) who also studies French firms, reveals that inputs from developing countries increase firm productivity, while inputs from developed countries have no significant effect on productivity.

Hence, the objective of this article is to empirically investigate the relevant firm-level characteristics necessary for firms to engage in global sourcing and determine the sources of such imports. Another crucial gap that this article tries to address is how import origin affects firm productivity and the link to export sales and the number of export markets. As discussed earlier, the impact of imported intermediate inputs on productivity and export performance, and whether these effects differ based on imports from low-wage or high-wage countries or both, remains unclear – both theoretically and empirically. Furthermore, few studies have examined these questions from a Swedish perspective, many of which are outdated due to the availability of more recent data and significant methodological advancements in recent years. In this article, we utilize the most available data ranging from 2007–2020 and implement an event study approach to capture heterogeneous treatment effects (de Chaisemartin & D’Haultfoeuille, 2022; Clarke & Schythe, 2020; Sun & Abraham, 2021) and a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach with a propensity score matching estimator (PSM).

This article underscores several important findings. First, almost 80% of Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees participate in the international market. The smallest firms predominantly engage as exporters, middle-size firms focus on imports, and the largest firms engage in both import and export activities, so-called two-way traders. Second, irrespective of firm size, most imports originate from high-wage countries. However, over the years, a gradual shift from high-wage to low-wage country imports has been observed. Third, becoming an importer requires possessing high levels of firm-specific characteristics. The most productive, largest, and have the highest average wage costs, and exporters are more inclined to import from all countries. Firms with slightly lower characteristics tend to import from either low- or high-wage countries, while firms with the lowest characteristics are non-importers. Among the small importing firms, the level of capital stock is a relatively more important determinant if imports are concentrated in either low- or high-wage countries, as compared to the case if firms import form all countries. Fourth, controlling for the self-selection mechanisms using an event study approach and difference-in-differences matching estimator, we find, for larger firms, no differences in productivity and export sales growth between importing and non-importing firms. However, we do find evidence suggesting that small importing firms experience higher productivity growth, primarily driven by imports from high-wage countries. Lastly, both small and large firms importing from both high- and low-wage countries have, on average, more high-wage export markets as compared to non-importers.

The next section describes the data and summary statistics. Section 3 describes the estimation strategies. Section 4 reports the results, and Section 5 concludes.

2 Data and Summary Statistics

The data utilized in this article were collected by Statistic Sweden over the period 2007–2020, covering all manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees[1]. The data comprise two databases, the Firm Statistics Register (FirmStat) and the Swedish Foreign Trade Register (TradeStat). The information extracted from FirmStat includes general firm accounting data such as sales, number of employees, wage costs, value-added, net investment value, capital stock, intermediate inputs, purchased final goods, and industry identifier[2]. Utilizing the number of employees, firms are categorized into small firms with fewer than 50 employees and large firms with 50 employees or more. Moreover, the information from FirmStat enables us to calculate capital intensity, defined as capital stock over sales, average wage costs, labor productivity, defined as sales per employee[3], and estimates total factor productivity by using the Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) methodology.

The information from TradeStat contains firm-level export and import values disaggregated by destination/origin and products, measured at the six-digit Combined Nomenclature (CN6). These data enable us to calculate, for each firm, the aggregate value of exports and imports to/from low- and high-wage countries. The definition of low- and high-wage countries is from The World Bank as of 2010 fiscal year.[4]

FirmStat and TradeStat can be merged by using the unique firm identifier which means that we have access to general accounting data and aggregate export and import values for both low- and high-wage countries for each firm. Unfortunately, however, there are some limitations to our dataset.

First, TradeStat does not provide information regarding whether traded products are raw materials, semi-manufactured goods, or intermediaries. Consequently, for imports, we cannot distinguish between transactions involving intermediate inputs or final goods. This implies that importing firms might include retailers that are not engaged in product manufacturing. Nevertheless, focusing only on the manufacturing sector, we observe that a very small fraction of firms report positive values for purchased final goods while simultaneously reporting zero values for intermediate inputs. This suggests that most of the firms in our data can be classified as manufacturers, with imported transactions likely serving as intermediate inputs. Second, TradeStat lacks information regarding whether imported transactions originate from affiliated providers (intra-firm sourcing) or unaffiliated providers (offshore outsourcing). Hence, we follow previous literature (e.g., Bandick, 2020; Crinò, 2009; Grossman & Rossi-Hansberg, 2006; Hijzen et al., 2010; Olsen, 2006) by using the value of imports as a proxy for global sourcing, without distinguishing the affiliation of the provider with the importing firm[5].

Given the available data, we are able to classify firms as exporters, importers, or both (referred to as two-way traders). Exporting firms are identified by assigning an indicator (Exporter) equal to one if the export value is positive, and zero otherwise. Additionally, we calculate the export intensity for each firm (EX_intensity_sales), defined as the ratio of export sales to total sales. Similarly, for importing firms, we assign an indicator (Importer) equal to one if the import value is positive, and zero otherwise. Import intensity is measured in two ways: one as the ratio of import value to total sales (IM_intensity_sales), and the other as the ratio of import value to the total value of intermediate inputs (IM_intensity_intermediate). Lastly, an additional indicator (two-way) is assigned to two-way traders, equaling one if both export and import values are positive, and zero otherwise.

With the panel data structure defined in terms of content and limitations, as well as the main variables, we proceed to present key facts and recent developments concerning the role of global sourcing in the Swedish manufacturing sector.

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the number of firms, mean employment and the share of importer and exporter over the period 2007–2020. Although the total number of firms declined over the period, the proportion of firms engaged in international trade, whether as importers, exporters, or both, remains relatively stable around 80%. On average, 7% of the firms exclusively use the international market for imports, while almost 13% exclusively engage in exporting, and 58% are two-way traders. Furthermore, Table 1 reveals clear differences in firm size, where the largest firms are two-way traders with an average of 124 employees, followed by exclusive importers with 33 employees, and the smallest firms are exclusive exporters with an average of 26 employees.

Number of firms, mean employment and share of importer and exporter, 2007–2020

| Year | All firms | Only importer | Only exporter | Two-way trader | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean employment | Share of firmsa | Mean employment | Share of firmsa | Mean employment | Share of firmsa | Mean employment | |

| 2007 | 6,724 | 86 | 7.2 | 28 | 12.9 | 23 | 57.4 | 133 |

| 2008 | 6,761 | 82 | 7.4 | 30 | 12.9 | 31 | 57.3 | 125 |

| 2009 | 6,313 | 79 | 6.7 | 28 | 13.8 | 24 | 57.2 | 120 |

| 2010 | 6,061 | 79 | 7.1 | 30 | 14.0 | 30 | 57.4 | 119 |

| 2011 | 5,964 | 82 | 6.8 | 37 | 12.9 | 27 | 58.0 | 123 |

| 2012 | 5,837 | 82 | 7.2 | 31 | 12.9 | 28 | 57.5 | 124 |

| 2013 | 5,621 | 82 | 7.1 | 34 | 12.6 | 24 | 58.2 | 124 |

| 2014 | 5,483 | 82 | 7.2 | 29 | 13.7 | 24 | 58.1 | 124 |

| 2015 | 5,390 | 80 | 7.1 | 33 | 12.5 | 25 | 59.0 | 119 |

| 2016 | 5,343 | 81 | 7.1 | 31 | 12.4 | 28 | 58.6 | 121 |

| 2017 | 5,266 | 83 | 7.6 | 38 | 12.4 | 24 | 58.7 | 125 |

| 2018 | 5,236 | 86 | 7.7 | 38 | 12.6 | 24 | 59.0 | 129 |

| 2019 | 5,137 | 88 | 7.7 | 34 | 11.7 | 25 | 60.0 | 129 |

| 2020 | 5,003 | 88 | 7.6 | 38 | 11.6 | 25 | 60.5 | 128 |

| Average | 5,724 | 83 | 7.2 | 33 | 12.8 | 26 | 58.4 | 124 |

Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. aShare of firms (percent) engaged in international trade.

Table 2 shows the distribution of importing firms based on their source countries, classifying them as exclusively importing from low-wage countries, exclusively from high-wage countries, or from both. At the beginning of the analysis period in 2007, nearly 60% of importing firms exclusively imported from high-wage countries. However, by the end of the study period in 2020, this share had decreased to less than 40%. Importantly, compared to all manufacturing firms, the share of firms exclusively importing from high-wage countries declined by almost 12% points during the 2007–2020 period. Meanwhile, firms importing from both low- and high-wage countries increased by 16% points relative to all importing firms and by 12% points relative to all firms. Firms exclusively importing from low-wage countries also exhibited a positive trend, with their share among total importing firms nearly quadrupling, from 1.6 to 5.4%, and among all firms increasing from 1.0 to 3.7%.

Share of firms importing from either or both low- and high-wage countries, 2007–2020

| Percentage of importing firms (percentage of all firms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Importing only from low-wage countries | Importing only from high-wage countries | Importing from both low- and high-wage countries |

| 2007 | 1.6 (1.0) | 58.5 (37.8) | 39.9 (25.8) |

| 2008 | 2.2 (1.4) | 56.5 (36.5) | 41.3 (26.7) |

| 2009 | 1.9 (1.2) | 54.2 (34.6) | 43.9 (28.1) |

| 2010 | 2.7 (1.7) | 52.2 (33.6) | 45.1 (29.1) |

| 2011 | 3.3 (2.2) | 50.9 (33.0) | 45.7 (29.6) |

| 2012 | 3.4 (2.2) | 49.8 (32.1) | 46.8 (30.2) |

| 2013 | 3.1 (2.0) | 49.0 (31.9) | 47.8 (31.2) |

| 2014 | 3.5 (2.3) | 46.5 (30.4) | 50.0 (32.6) |

| 2015 | 4.2 (2.8) | 42.4 (28.0) | 53.4 (35.3) |

| 2016 | 4.0 (2.6) | 43.2(28.4) | 52.7 (34.6) |

| 2017 | 4.3 (2.9) | 41.4 (27.5) | 54.3 (36.0) |

| 2018 | 4.3 (2.8) | 40.2 (26.8) | 55.6 (37.1) |

| 2019 | 4.7 (3.2) | 38.0 (25.8) | 57.3 (38.9) |

| 2020 | 5.4 (3.7) | 38.6 (26.3) | 56.0 (38.1) |

Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. Countries categorized by the World Bank as upper-middle or high-income groups until the fiscal year 2010 are defined as high-wage countries, whereas countries categorized as low or lower-middle income groups are defined as low-wage countries. All figures are in percent. The percentage share importing firms, percentage of total firms in parentheses (.).

As shown in Table 3, the shifts in import origin observed in Table 2 are evident across nearly all the two-digit (NACE Rev.2) manufacturing industries. However, these patterns exhibit significant variation among industries. For instance, in the Manufacturing industry of leather and related products (SNI07_15), the share of firms exclusively importing from high-wage countries decreased by about 2% points from 2007 to 2020, whereas in the Manufacturing industry of coke and refined petroleum products (SNI07_19), this share dropped by 33% points. Similarly, while some industries had no change in the share of firms exclusively importing from low-wage countries, others experienced an increase of nearly 5% points over the same period. These differences highlight industry-specific trends in import sourcing that we need to control for in the empirical model below.

Share of firms importing from low-, high-, or both low- and high-wage countries, 2-digit industry level, percentage point change, 2007–2020

| Manufacturing industries SNI07 (NACE Rev. 2) | % change of importing firms (% change all firms) 2007–2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNI07 | Description | Importing only from Low-wage countries | Importing only from High-wage countries | Importing from both Low- and High-wage countries |

| 10 | Manufacture of food products | 2.3 (4.5) | −8.0 (−18.0) | 7.3 (13.4) |

| 11 | Manufacture of beverages | 0 (0) | 8.9 (−2.7) | 15.2 (2.7) |

| 12 | Manufacture of tobacco products | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | −14.3 (−25.0) |

| 13 | Manufacture of textiles | 1.0 (1.0) | −17.5 (−20.3) | 18.9 (22.8) |

| 14 | Manufacture of wearing apparel | 0 (0) | −3.4 (−4.0) | 6.5 (4.0) |

| 15 | Manufacture of leather and related products | 0 (0) | −2.2 (−5.0) | 13.3 (5.0) |

| 16 | Manufacture of wood and of products of wood and cork, except furniture; manufacture of articles of straw and plaiting materials | 3.1 (7.0) | −3.4 (−4.8) | −1.3 (−2.2) |

| 17 | Manufacture of paper and paper products | 0 (0) | −22.9 (−29.8) | 31.8 (29.8) |

| 18 | Printing and reproduction of recorded media | 3.4 (3.0) | 3.4 (−20.8) | 15.8 (17.7) |

| 19 | Manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products | 0 (0) | −32.9 (−35.0) | 31.5 (35.0) |

| 20 | Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products | −0.3 (1.4) | −22.4 (−24.1) | 21.0 (22.7) |

| 21 | Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations | 0 (0) | −32.5 (−34.0) | 31.3 (34.0) |

| 22 | Manufacture of rubber and plastic products | 2.0 (3.2) | −23.8 (−29.7) | 24.8 (26.5) |

| 23 | Manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products | 1.0 (3.0) | −10.4 (−9.0) | 1.1 (6.0) |

| 24 | Manufacture of basic metals | 2.8 (0.6) | −6.7 (−10.4) | 10.9 (9.7) |

| 25 | Manufacture of fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment | 4.5 (8.6) | −10.8 (−23.6) | 8.0 (14.9) |

| 26 | Manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products | 2.2 (2.8) | −15.3 (−16.2) | 12.3 (13.4) |

| 27 | Manufacture of electrical equipment | 0.2 (0.2) | −16.6 (−20.0) | 16.5 (19.9) |

| 28 | Manufacture of machinery and equipment n.e.c. | 1.0 (0.5) | −12.3 (−18.5) | 18.9 (18.0) |

| 29 | Manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers | 4.0 (4.3) | −16.4 (−23.8) | 19.7 (19.5) |

| 30 | Manufacture of other transport equipment | 1.9 (1.6) | −1.6 (−12.0) | 21.1 (10.4) |

| 31 | Manufacture of furniture | 4.8 (7.3) | −14.0 (−19.3) | 6.0 (12.0) |

| 32 | Other manufacturing | 2.9 (5.6) | −12.3 (−16.4) | 10.8 (10.8) |

| 33 | Repair and installation of machinery and equipment | 0.1 (5.9) | −8.1 (−12.6) | 3.1 (6.7) |

Notes: see Table 2.

When examining the development of import intensity and the number of imported products over the years, it becomes evident that differences exist between small and large firms. This distinction is highlighted in Table 4. For small firms (those with fewer than 50 employees), the average share of import value over sales is 6%, and, comparatively, the share of import value over total intermediate inputs is nearly 11%. In contrast, large firms exhibit significantly higher ratios of 17 and 31%, respectively. Moreover, regarding the number of imported products (as shown in the last column of Table 4), small firms import an average of 3.6 products, while large firms import an average of 13 products.

Import intensity, number of imported products and firm size

| Year | Import intensity_sales | Import intensity_intermediate | #imported products | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small firm | Large firm | Small firm | Large firm | Small firm | Large firm | |

| 2007 | 6.7 | 15.9 | 12.0 | 28.9 | 3.6 | 11.8 |

| 2008 | 6.7 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 29.3 | 3.6 | 11.9 |

| 2009 | 6.0 | 14.9 | 10.5 | 28.2 | 3.5 | 12.0 |

| 2010 | 6.3 | 16.4 | 10.7 | 30.4 | 3.4 | 12.5 |

| 2011 | 6.2 | 16.6 | 10.5 | 30.5 | 3.5 | 12.5 |

| 2012 | 6.0 | 15.9 | 10.6 | 29.5 | 3.6 | 12.8 |

| 2013 | 6.0 | 16.5 | 11.1 | 31.9 | 3.7 | 13.2 |

| 2014 | 6.4 | 17.0 | 11.7 | 32.7 | 3.7 | 13.5 |

| 2015 | 5.8 | 16.7 | 10.2 | 31.4 | 3.5 | 13.4 |

| 2016 | 5.4 | 16.6 | 9.9 | 31.9 | 3.5 | 13.6 |

| 2017 | 5.8 | 16.9 | 10.1 | 30.8 | 3.6 | 13.7 |

| 2018 | 6.1 | 17.3 | 10.5 | 31.3 | 3.7 | 13.8 |

| 2019 | 6.3 | 17.2 | 10.8 | 31.4 | 3.9 | 14.1 |

| 2020 | 6.2 | 16.8 | 10.5 | 31.7 | 3.9 | 13.8 |

| Average | 6.1 | 16.5 | 10.8 | 30.7 | 3.6 | 13.0 |

Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. Firms fewer than 50 employees are defined as small firms while firms with 50 employees or more are defined as large firms. Import intensity_sales is measured as the ratio of import value to total sales and import intensity_intermediate is measured as the ratio of import value to total value of intermediate inputs.

In Table 5, we present the average number of unique countries from which firms import. The categories of countries that imports originate from are divided into EU-15, EU-12 (countries that joint the EU during the 2004, 2007, and 2013 enlargement), other high-wage countries, and lastly, low-wage countries. It is evident that regardless of firm size, imports primarily originate from EU15 and other high-wage countries. The dominance of EU15 countries as a source of Swedish imports, besides the membership of the European Union, can be explained by firms’ participation in GVCs, especially within strategic sectors such for example the automotive and pharmaceutical sectors, where the production chains mainly are clustered regionally in Europe. Over the years, small firms appear to have imported from an average of 1.3 EU15 countries, while large firms imported from more than one-third of EU15 countries. As it seems, the number of countries within EU12 and other high-wage countries as import partners are relatively consistent over the years for small firms.

Number of import countries and firm size

| Year | Small firm | Large firm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #EU15 | #EU12 | Other High-wage countries | Low-wage countries | #EU15 | #EU12 | Other High-wage countries | Low-wage countries | |

| 2007 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 5.4 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| 2008 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| 2009 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 2.0 |

| 2010 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 2.2 |

| 2011 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 2.1 |

| 2012 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 2.3 |

| 2013 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| 2014 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| 2015 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 2.6 |

| 2016 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.6 |

| 2017 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.6 |

| 2018 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.7 |

| 2019 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 2.8 |

| 2020 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 2.6 |

| Average | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. Firms fewer than 50 employees are defined as small firms while firms with 50 employees or more are defined as large firms.

However, the significance of low-wage countries as import partners has increased over time. For instance, the average number of low-wage countries from which small firms import has doubled, from an average of 0.4 countries in 2007 to 0.8 countries in 2020. During the same period, small firms reduced the number of countries within the EU15 as import partners by an average of 0.3 countries. Among large firms, the number of import countries within EU15 and other high-wage counties remains relatively constant, while they appear to import from more EU12 and low-wage countries. Notably, the number of EU12 import countries increased by more than 70%, while the number of low-wage import countries increased by almost 40%, respectively[6].

Moving to Table 6, we present differences in various firm-specific characteristics between importers and non-importers, stratified by firm size and import origin. A notable difference emerges between small firms that are importers and their non-importing counterparts, irrespective of whether they import exclusively from low- or high-wage countries or both. Small importing firms exhibit higher productivity, larger export sales, engagement with more export destinations, larger employment and capital stock, and higher average wage costs. Interestingly, these differences are even more pronounced when comparing small firms that import from all countries to those that do not engage in importing. Conversely, no statistically significant differences are observed between large firms exclusively importing from low-wage countries and their non-importing counterparts. However, large firms importing from either high-wage countries or all countries display significantly better firm-specific characteristics compared to non-importing large firms.

Differences in firm-specific characteristics between importing and non-importing firms

| Importing only from Low-wage countries vs Non-importer | Importing only from High-wage countries vs Non-importer | Importing from both Low- and High-wage countries vs Non-importer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small firms | Large firms | Small firms | Large firms | Small firms | Large firms | |

| Log Productivity | 0.140 | −0.065 | 0.328 | 0.241 | 0.456 | 0.390 |

| (9.78)*** | (1.14) | (58.63)*** | (13.21)*** | (72.95)*** | (22.17)*** | |

| Log Export sales | 0.725 | −0.464 | 1.720 | 1.763 | 2.900 | 3.662 |

| (8.18)*** | (1.50) | (47.31)*** | (16.10)*** | (81.25)*** | (41.98)*** | |

| Export countries | 0.837 | 1.251 | 2.056 | 5.019 | 11.249 | 24.178 |

| (7.45)*** | (2.39)*** | (25.51)*** | (11.17)*** | (75.91)*** | (27.68)*** | |

| Log Employment | 0.084 | −0.077 | 0.195 | 0.284 | 0.313 | 0.690 |

| (8.09)*** | (1.77)* | (47.67)*** | (14.25)*** | (68.63)*** | (25.90)*** | |

| Log Capital stock | 0.222 | 0.069 | 0.507 | 0.807 | 0.428 | 1.177 |

| (5.39)*** | (0.45) | (32.66)*** | (16.22)*** | (24.73)*** | (22.49)*** | |

| Average wage cost | 0.099 | 0.011 | 0.119 | 0.062 | 0.227 | 0.197 |

| (6.65)*** | (0.22) | (21.73)*** | (3.92)*** | (36.62)*** | (12.81)*** | |

Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. Firms fewer than 50 employees are defined as small firms while firms with 50 employees or more are defined as large firms. Labor productivity is defined as sales per employee. Average wage cost is calculated as total wage cost per employee. Standard deviation in parentheses. ***, **, * indicate significance at 1, 5 and 10% levels, respectively.

In conclusion, this section highlights the substantial engagement of Swedish manufacturing firms in the international market, as importers, exporters or, as most of the firms are, two-way traders. There is a clear ranking of the firms, with exclusive exporters being the smallest, exclusive importers being the middle, and two-way traders are the largest group in terms of the number of employees. Irrespective of firm size, a considerable share of imports originates from high-wage countries. Nonetheless, changes in import distribution are observed over the years, including shifts from high- to low-wage countries and an increase in the number of low-wage import partners. Notable, importing firms display superior firm-specific characteristics compared to non-importing counterparts, with this gap being more pronounced among those importing from both low- and high-wage countries.

Given the significance development and shift of import origin, as well as the disparities between importers and non-importers, we proceed to analyze in subsequent sections how these trends have impacted firms’ productivity and export performances.

3 Econometric Considerations

The empirical strategy in this paper is to investigate the differences in outcomes for firms that import with the outcomes they would have had if they had not imported. However, this hypothetical “non-importer” event is not observable for firms already involved in importing. Following Heckman et al. (1997), we can define the average effect of importing on the outcome variable (in our case productivity and export performances) as:

Here,

However, this approximation is only valid if there are no contemporaneous effects that are correlated with the decision to import. Such effects could introduce endogeneity bias into the empirical analysis. Unfortunately, this is not unlikely to be the case since, as discussed earlier, and demonstrated in Table 6, there is empirical evidence that firms that import tend to possess better firm-specific characteristics compared to non-importing firms. This makes it difficult to distinguish whether post-import productivity and export performances are influenced by the decision to import, or by the firms’ ex-ante characteristics. Therefore, when constructing the counterfactual event, it is crucial to select a valid control group. To address this issue of endogeneity bias, we employ two common methods, namely Event Study approach and DiD with a PSM.

Starting with the Event Study approach, the initial step involves examining whether there are any differences in pre- and post- trends between importing and non-importing firms. The challenge at hand involves two-sided heterogeneity: one across firms to be treated (becoming an importer) and another with respect to the timing of the treatment. As previously discussed, importing firms often possess superior characteristics that may influence their decision to engage in importing. This selection bias can obscure the true impact of importing on productivity and export performances, given that importers tend to be inherently more productive and possess advantageous attributes compared to their counterparts. Moreover, firms may opt to import from various sourcing countries due to distinct strategic motives that may correlate with their pre-existing firm-specific attributes. Furthermore, the effect of imports on productivity and export performances varies depending on when firms begin importing since not all firms initiate imports simultaneously.

To address these complexities, we adopt the panel Event Study framework proposed by Clarke and Schythe (2020) and de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (2022). More precisely, we estimate the following dynamic two-way fixed model:

In equation (2),

The binary variables j and k indicate the number of years before and after the first event in which the import indicator switches from zero to one. For instance,

Firms that never started to import (never treated) are used as control firms. For these firms, leads and lags for the corresponding years are set to zero. The first lead in equation (2) serves as the reference base year[7]. Consequently, leads and lags estimate the differences between treated and control firms in comparison to the baseline year differences. The assumption underlying this approach is that in the absence of treatment, the difference in the outcome variable between treated and control groups would have remained similar to the baseline. This is commonly referred to as the parallel trends assumption. As an additional robustness measure for selecting appropriate control firms, we will consider those that became importers last year in the panel (last-treated) as proposed by Callaway and Sant’Annac (2021) and Sun and Abraham (2021).

As mentioned earlier, the other common method to assess the impact of a treatment is to use DiD with a propensity score matching. The objective of the matching approach is to mitigate dissimilarities among firms by identifying, for each importing firm, a comparable firm that did not engage in importing (to approximate the non-observed counterfactual event). Conversely, the concept of DiD aims to eliminate the influence of unobservable firm-specific effects. The DID-PSM proceeds through the following steps: Conditional on a set of firm characteristics, the firm’s probability (referred to as propensity score) to initiate importing is estimated using the probit model as described by equation (A1) in the Appendix.

Subsequently, once the propensity scores are computed, the nearest control firms for which the propensity score falls within a pre-defined radius can be selected as matches for the importing firm.[8] Moreover, it is essential to verify the balancing condition – ensuring that each independent variable does not significantly differ between importing and non-importing firms – and the so-called common support condition[9], which ensures that firms with identical X values possess a positive probability of being both importing and non-importing firms.

The difference-in-differences matching estimator,

Here,

4 Results

Before reporting the main results, we first summarize the results analyzing the role of ex-ante firm-specific characteristics in the decision for a firm to source inputs from abroad. Here, we refer to the Appendix for the empirical setup and the corresponding tables to save space. As revealed in Tables A1 and A2, there is compelling evidence that superior firm-specific characteristics are necessary for firms to become importers. The results clearly demonstrate a ranking order where firms that are most productive, largest, and have highest average wage costs are more likely to import from all countries, followed by firms exclusively import from either low- or high-wage countries, and finally, firms that do not import. The findings also suggest that among importers, particularly for small firms, the level of capital stock is a relatively more important determinant for sourcing from either low- or high-wage countries. Given these results, it is imperative to account for the self-selection mechanism when evaluating the effects of imports. Without such consideration, the estimate of the causal effect could potentially be biased, as discussed in Section 3.

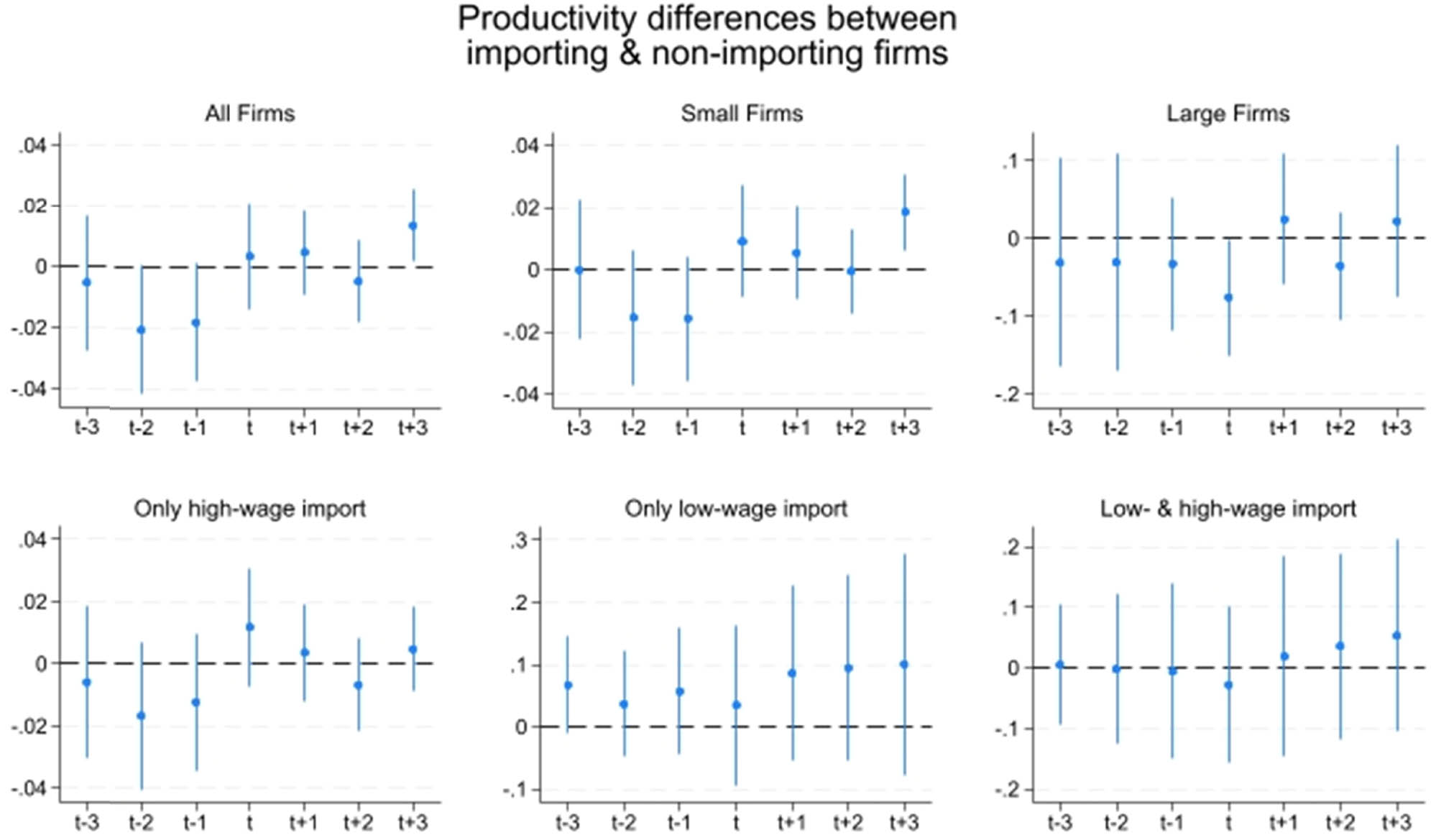

Moving now to the results from Event study and DiD-PSM. In Figure 1, we illustrate the effect of imports on productivity levels using equation (2). As discussed earlier, our analysis includes three lags and three leads representing time before and after the firm started importing. Therefore, the binary variables t−3, t−2, and t−1, on the x-axis are set to one for three, two, and one years before the firm´s import initiation at time t0 (base year), while t+1, t+2, and t+3 are set to one for the years after the import. The differences in productivity levels between importing and non-importing firms, displayed on the y-axis, are presented by point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each of the three lags and leads. As discussed before, we also include base year firm-specific variables as included in the probit model, equation (A1), and control for firm and time-fixed effects.

Productivity differences between importing and non-importing firms. Notes: Source: Statistics Sweden. The sample include all Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees. Firms fewer than 50 employees are defined as small firms while firms with 50 employees or more are defined as large firms. The upper-left corner presents the results of estimating equation (2) for all firms, the upper-middle solely for small firms and upper-right corner solely for large firms. The lower plots present the results when import originates exclusively from high-wage countries in lower-left corner, exclusively from low-wage countries in the lower-middle, and from all countries in lower-right corner. On the x-axis, t−3, t−2 and t−1 are binary variables equals to one for three, two and one year before the firm´s import initiation at time t0 (base year), and t+1, t+2 and t+3 are set to one for the years after the import. On the y-axis, the differences in the level of the outcome between importing and non-importing firms are presented by point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each of the three lags and leads. The model includes base year firm-specific variables (as in Table A1) and control for firm and time fixed effects.

The results of estimating equation (2) for all firms without distinguishing their size or import source are shown in the upper-left corner of Figure 1. It can be observed that the pre-trends in productivity levels, measured as log sales per employees, do not appear to differ between importing and non-importing firms[10]. This suggests that the key assumption for the validity of the parallel trends is satisfied. Additionally, the point estimates for periods following the base year t0 are not significantly different from zero, indicating that, on average, importing and non-importing firms experience similar productivity levels over the years.

In the subsequent step, we proceed to analyze whether the impact of imports on productivity depends on firm size and import source. The upper plots of Figure 1 present the results of estimating equation (2) solely for small firms in the upper-middle and solely for large firms in the upper-right corner. The lower plots of Figure 1 present the results when import originates exclusively from high-wage countries in the lower-left corner, exclusively from low-wage countries in the lower-middle, and from all countries in the lower-right corner. In all cases, the productivity differences between pre- and post-periods for importing firms are compared to productivity differences for non-importing firms. It can be observed that, regardless of firm size and import origin, there are no significant differences in the productivity levels between importing and non-importing firms in the periods before or after the base year t0.

Thus far, the results from the event study suggest that sourcing from abroad does not influence the differences between importing and non-importing firms, at least in terms of productivity levels. Consequently, we continue our analysis to determine whether sourcing from abroad impacts another crucial outcome for firms, namely export sales. Figure 2 presents the re-estimated equation (2), with log export sales as the dependent variable. As before, we include similar base year firm-specific variables and control for firm and time-fixed effects. The plot arrangement in Figure 2 mirrors that of Figure 1, with upper plots dividing the results by different firm sizes, and lower plots by different import origins. The results once again suggest that, regardless of firm size or import source, importing firms experience similar levels of export sales as non-importing firms.

Export sales differences between importing and non-importing firms. Notes: see Figure 1.

In summary, the results from the Event Study indicate that import does not have a statistically significant impact on firms’ productivity and export sales, whether we control for firm size or import origin. However, is this result robust when simultaneously controlling for firm size and import origin? In other words, how do productivity and export sales change for small and large firms, respectively, while accounting for import origin? Moreover, how does the number of export markets these firms engage in change based on the origin of their imports? To answer these questions, we proceed to implement one of the most commonly used evaluation methods in the field, the DiD propensity score-matching by using equation (3). As mentioned before, the matched non-importing firms are used to approximate unobserved counterfactual events, that is, what would have happened to the productivity and export performance of importing firms on average if they had not initiated imports.

Table 7 presents the DiD matching estimator,

Import and productivity growth, matched sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-wage countries only | Low-wage countries only | Low- and high-wage countries | |

| Specification (1) | |||

| Small firms | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.015 |

| (0.004)** | (0.023) | (0.007)** | |

| Specification (2) | |||

| Large firm | −0.014 | −0.011 | −0.017 |

| (0.026) | (0.053) | (0.024) |

Notes: The results in specification (1) are based on estimating equation (3) for small firms only, with small non-importers as the reference group, while specification (2) report the results for large firms, with large non-importers as the reference group. The indicator in column (1) is equal to one for firms importing exclusively from high-wage countries, in column (2) it is equal to one for firms importing exclusively from low-wage countries, and in column (3) it is equal to one for firms importing from all countries. Standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicate significance at 1, 5 and 10% levels, respectively.

The result in Table 7, Specification (1) and column (1), indicates that small firms importing exclusively from high-wage countries experience, on average, a 0.9% points higher growth in productivity compared to small non-importing firms. In column (3), this difference increases to about 1.5% points for small firms importing from all countries, in comparison to small non-importers. However, small firms that exclusively import from low-wage countries do not appear to exhibit different productivity growth compared to small non-importers, as shown in specification (1); column (2). The results in specification (2) for larger firms also indicate that importing firms, regardless of import origin, experience similar productivity growth as non-importing large firms.

To summarize the findings of the DiD-PSM thus far, we can conclude that importing firms tend to have higher ex-ante productivity levels as compared to non-importing firms. Upon accounting for this, it appears that larger importing firms exhibit similar post-import productivity development to their non-importing counterparts. For small firms, however, there seems to be a slight learning effect from importing in terms of higher productivity, particularly when importing from high-wage countries, albeit marginally more so than from low-wage countries.

We now proceed to present the results of how imports affect export performances, as shown in Table 8. This analysis excludes non-exporting firms. The first three columns depict the results for export sales. Columns (4)–(6) and (7)–(9) present the results for how imports impact the total number of export countries and the total number of high-wage export counties, respectively. The structures of the two specifications and the division of the import indicators in the respective columns mirror those in Table 7. Controlling for firm size and import origin, the export sales do not seem to differ between importing and non-importing firms. Moreover, relative to small non-importing firms, small firms concentrating their import from low-wage countries appear to leave high-wage export markets to a greater extent. Simultaneously, small firms importing from both low- and high-wage countries export to on average 8 more high-wage countries than their non-importing counterparts. Similar trends are observed for large firms importing from all countries, which export to an average of 3 more high-wage countries compared to large non-importing firms. However, large firms that primarily import from high-wage countries seem to reduce their participation in high-wage export markets by over 1 market on average, in contrast to large non-importers.

Import and export growth and number of export countries

| Growth of export value | Number of export countries | Number of high-wage export countries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Import from: | |||||||||

| High-wage countries only | Low-wage countries only | High- and low-wage countries | High-wage countries only | Low-wage countries only | High- and low-wage countries | High-wage countries only | Low-wage countries only | High- and low-wage countries | |

| Specification (1) | |||||||||

| Small firms | 0.009 | −0.168 | 0.059 | −0.083 | 0.204 | 10.483 | −0.039 | −0.422 | 8.096 |

| (0.062) | (0.160) | (0.057) | (0.098) | (0.180) | (0.343)*** | (0.089) | (0.149)*** | (0.258)*** | |

| Specification (2) | |||||||||

| Large firm | 0.492 | −0.499 | 0.281 | −1.936 | −0.800 | 4.045 | −1.617 | −1.200 | 3.636 |

| (0.431) | (1.014) | (0.465) | (0.753)*** | (2.387) | (1.383)*** | (0.604)*** | (2.332) | (1.146)*** | |

Notes: Non-exporting firms are excluded. Column (1) – (3) show the results for export sales. Column (4) to (6) and (7) to (9) present the results for how imports impact the total number of export countries and the total number of high-wage export counties, respectively. Specification (1) show the results for small firms only, with small non-importers as the reference group, while specification (2) reports the results for large firms, with large non-importers as the reference group. The indicator in column (1), (4) and (7) equal to one for firms importing exclusively from high-wage countries, in column (2), (5) and (8) it is equal to one for firms importing exclusively from low-wage countries, and in column (3), (6) and (9) it is equal to one for firms importing from all countries. Standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicate significance at 1, 5 and 10% levels, respectively.

5 Summary and Conclusions

There is substantial evidence underscoring the significance of global trade in driving economic growth, particularly benefiting firms in small open economies by providing access to larger markets. However, there is also evidence that only the most productive firms enter the export market, and they rely heavily on global sourcing due to the increasing fragmentation of production processes. This article aims to explore the relationship between imports, productivity, and export performance. Our initial empirical exploration delves into the relevant firm-level characteristics required for firms to engage in foreign sourcing, as well as the origins of their sourcing. Subsequently, we examine how the source of imports impacts firm productivity and its connection to export sales and the number of export markets.

The data utilized in this article cover the entire Swedish manufacturing firms with at least 10 employees over the period 2007–2020. We adopt the most recently developed event study approach to account for heterogeneous treatment effects and combine a DiD approach with a PSM.

This article underscores several key findings. First, nearly 80% of the sampled firms engage in international trade, with smaller firms predominantly functioning as exporters, mid-sized firms as importers, and larger firms engaging in two-way trading. Second, while imports predominantly originate from high-wage countries, there is a gradual shift toward low-wage countries over time. Third, a clear hierarchy emerges regarding firms’ import behaviors based on productivity levels, with high-productive firms importing from all countries, followed by firms sourcing from low- or high-wage countries, and non-importing firms. Among small importing firms, the level of capital stock appears as a crucial determinant, particularly when imports are concentrated in low- or high-wage countries. Fourth, accounting for self-selection mechanisms, we find no significant differences in productivity and export sales growth between importing and non-importing larger firms. However, small importing firms experience higher productivity growth, primarily driven by imports from high-wage countries. Additionally, both small and large firms importing from both high- and low-wage countries tend to access more high-wage export markets.

As a final remark, the findings of this article provide significant policy implications, suggesting the importance of promoting access to imported intermediate inputs, especially from technologically advanced countries, to enhance domestic productivity and export potential. Policies should target small firms not currently engaged in international markets and those exclusively importing or exporting, aiming to improve their competitiveness. Encouraging diversification of import sources and aiming for favorable terms for the import of high-quality inputs during trade negotiations can further enable firms to exploit the benefits of global sourcing.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the participants at the XXIV Conference on International Economics and at the twenty-fourth Annual ETSG Conference.

-

Funding information: This work has been fully supported by National Board of Trade, Sweden.

-

Author contributions: RB, PK and PT have contributed equally to all parts of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The micro register data from Statistics Sweden is restricted only to researcher within Swedish authorized research environments and have permitted research proposal following the rules by the Swedish ethical legalization laws. More information about the data availability can be found here: https://www.scb.se/en/services/ordering-data-and-statistics/microdata/mona--statistics-swedens-platform-for-access-to-microdata/.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

Appendix

To analyze how ex-ante firm-specific characteristics affect a firm´s decision to import and the source of imports, we will utilize the following probit models:

In equation (A1), the binary variable

The result from the probit model is shown in Table A1. In the first column, we estimate equation (A1) for all firms. The result suggests that higher productivity levels make firms more likely to source from abroad. Moreover, as shown by previous studies such as Debaere et al. (2013) and Görg et al. (2008), it appears that exporters are more inclined to engage in importing. In fact, all the firm-level variables included in the probit model, except for capital stock, appear to positively influence firms’ decision to import. This finding aligns with previous research (e.g., Fariñas et al., 2010; Görg et al., 2008; Hummels et al., 2014; Sethupathy, 2013; Sharma & Mishra, 2015; Wagner, 2011) that provides evidence of self-selection among importing firms. In subsequent columns of Table A1, we estimate equation (A1) separately for small firms, in column (2), and for large firms, in column (3). The results seem to be consistent across small and large firms.

Firm probability to import; Probit model

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All firms | Small firms | Large firms | |

| Labor productivity | 0.349 | 0.367 | 0.173 |

| (0.012)*** | (0.013)*** | (0.031)*** | |

| Level of employment | 0.568 | 0.489 | 0.505 |

| (0.010)*** | (0.015)*** | (0.033)*** | |

| Capital stock | −0.040 | −0.041 | −0.022 |

| (0.004)*** | (0.004)*** | (0.013)* | |

| Growth relative to industry | 1.101 | 0.852 | 1.273 |

| (0.457)** | (0.504)* | (1.031) | |

| Average wage costs | 0.523 | 0.594 | 0.281 |

| (0.024)*** | (0.027)*** | (0.051)*** | |

| Exporter | 1.227 | 1.205 | 1.422 |

| (0.013)*** | (0.014)*** | (0.043)*** | |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.209 | 0.234 | 0.193 |

| LR chi2 | 17,916 | 15,795 | 1,961 |

| Observations | 67,783 | 49,452 | 18,331 |

Notes: The dependent variable is a dummy variable that equals to 1 if firm i import in period t but not in t−1 and 0 if the firm does not import during these two periods. Coefficients are reported as marginal effect. Standard errors. (clustered at the firm level) within parentheses. Besides the variable Growth relative to industry and Exporter, all the other explanatory variables are lagged 1 year. Year dummies are included. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10% levels, respectively.

With these results in mind, we proceed to analyze whether self-selection also applies to the decision of sourcing from different countries. Additionally, we test whether the predicted probability of ex-ante firm-specific characteristics influencing the decision to source from different countries varies between small and large firms. Table A2 presents the results of estimating the multinomial probit model described by equation (A2). In this case, we only include importing firms, and in column (1), the dependent variable defines the origin of the import, with the indicator set to 0 for firms importing exclusively from low-wage countries, 1 for firms importing exclusively from high-wage countries, and 2 for firms importing from all countries. Consequently, the reference group are firms that exclusively import from low-wage countries.

Import, choices of origin, Multinomial Probit model

| Import origin | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All firms | Small firms | Large firms | |

| Import high-wage countries only | |||

| Labor productivity | 0.264 | 0.212 | 0.468 |

| (0.028)*** | (0.031)*** | (0.076)*** | |

| Level of employment | 0.201 | 0.156 | 0.383 |

| (0.028)*** | (0.042)*** | (0.103)*** | |

| Capital stock | 0.042 | 0.043 | 0.022 |

| (0.012)*** | (0.012)*** | (0.037) | |

| Growth relative to industry | −0.249 | −0.331 | 0.565 |

| (1.063) | (1.152) | (2.796) | |

| Average wage costs | 0.339 | 0.560 | −0.018 |

| (0.055)*** | (0.071)*** | (0.980) | |

| Exporter | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.061 |

| (0.041) | (0.043) | (0.125) | |

| Import low- and high-wage countries | |||

| Labor productivity | 0.407 | 0.376 | 0.569 |

| (0.029)*** | (0.032)*** | (0.075)*** | |

| Level of employment | 0.765 | 0.638 | 0.986 |

| (0.028)*** | (0.043)*** | (0.103)*** | |

| Capital stock | −0.083 | −0.077 | −0.117 |

| (0.012)*** | (0.013)*** | (0.037)*** | |

| Growth relative to industry | 1.558 | 1.395 | 2.440 |

| (1.081) | (1.088) | (2.801) | |

| Average wage costs | 0.893 | 1.013 | 0.686 |

| (0.056)*** | (0.073)*** | (0.099)*** | |

| Exporter | 1.391 | 1.266 | 2.117 |

| (0.046)*** | (0.049)*** | (0.137)*** | |

| Wald chi2 | 7,242 | 3,009 | 1,920 |

| Observations | 45,494 | 28,343 | 17,151 |

Notes: The depended variable

The result shown in Table A2; column (1) indicates that firms importing from all countries are, ex-ante, the most productive, largest, and possess the highest average wage costs in comparison to firms exclusively importing from high- or low-wage countries. Being an exporter is also a significant driver for firms to import from all countries. However, the level of capital stock seems unimportant for firms that import from all countries, but it appears to be more relevant for firms importing exclusively from either low- or high-wage countries. Regarding exporter status and relative sales growth within the industry, they do not seem to affect the decision to source from either low- or high-wage countries.

Moving to Table A2; columns (2) and (3), we use a similar estimation strategy as in the previous column but restrict the sample to small and large firms, respectively. The results for firms of different sizes do not appear to differ significantly from those in column (1).

In summary, the results from the probit models highlight the importance of possessing superior firm-specific characteristics for the firms to become importers. The results also reveal a distinct hierarchy where firms that are most productive, largest, and have the highest average wage costs are more inclined to import from all countries. Firms that exclusively import form either low- or high-wage countries have the next best firm-specific characteristics, while firms that do not import have the least firm-specific characteristics. Additionally, the findings suggest that among importers, particularly for small firms, the level of capital stock is a relatively more important determinant for sourcing from either low- or high-wage countries.

References

Abraham, K. G., & Taylor, S. K. (1996). Firms’ use of outside contractors: Theory and evidence. Journal of Labour Economics, 14(3), 394–424.10.1086/209816Search in Google Scholar

Abramovsky, L., Griffith, R., & Miller, H. (2017). Domestic effects of offshoring high-skilled jobs: Complementarities in knowledge production. Review of International Economics, 25(1), 1–20.10.1111/roie.12242Search in Google Scholar

Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638.10.1257/aer.97.5.1611Search in Google Scholar

Antràs, P, & Chor, D. (2022). Global value chains. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (pp. 297–376, 2022, chapter 5). Elsevier.10.1016/bs.hesint.2022.02.005Search in Google Scholar

Antràs, P., Fadeev, E. Fort, T. C., & Tintelnot, F. (2022). Global sourcing and multinational activity: A unified approach. Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w30450Search in Google Scholar

Aristei, D., Castellani, D., & Franco, C. (2013). Firms’ exporting and importing activities: Is there a twoway relationship? Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 149(1), 55–84.10.1007/s10290-012-0137-ySearch in Google Scholar

Bandick, R. (2016). Offshoring, plant survival and employment growth. The World Economy, 39(5), 597–620.10.1111/twec.12316Search in Google Scholar

Bandick, R. (2020). Global sourcing, productivity and export intensity. The World Economy, 43(3), 615–643.10.1111/twec.12887Search in Google Scholar

Bas, M. (2012). Input-trade liberalization and firm export decisions: Evidence from Argentina. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 481–493.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.05.010Search in Google Scholar

Bas, M., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2014). Does importing more inputs raise exports? Firm-level evidence from France. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 150, 241–275.10.1007/s10290-013-0175-0Search in Google Scholar

Bertrand, O. (2011). What goes around, comes around: Effects of offshore outsourcing on the export performance of firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 42, 334–344.10.1057/jibs.2010.26Search in Google Scholar

Callaway, B., & Sant’Annac, P. H. C. (2020). Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230.10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001Search in Google Scholar

Castellani, D., Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2010). Firms in international trade: Importers’ and exporters’ heterogeneity in Italian manufacturing industry. World Economy, 33, 424–457.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01262.xSearch in Google Scholar

Clarke, D., & Tapia-Schythe, K. (2020). Implementing the panel event study. The Stata Journal, 21(4), 853–884.10.1177/1536867X211063144Search in Google Scholar

Crinò, R. (2009). Offshoring, multinationals and labour market: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23, 197–24910.1111/j.1467-6419.2008.00561.xSearch in Google Scholar

Debaere, P., Görg, H., & Raff, H. (2013). Greasing the wheels of international commerce: How services facilitate firms’ international sourcing. Canadian Journal of Economics, 46(1), 78–102.10.1111/caje.12006Search in Google Scholar

de Chaisemartin, C., & D’Haultfoeuille, X. (2022). Difference-in-Differences Estimators of Intertemporal Treatment Effects (tech. rep.). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w29873Search in Google Scholar

Díaz-Mora, C., Córcoles, D., & Gandoy, R. (2015). Exit from exporting: Does being a two-way trader matter? Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 9(2015-20), 1–27.10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2015-20Search in Google Scholar

Doh, J., Bunyaratavej, K., & Hahn, E. (2009). Separable but not equal: The location determinants of discrete services offshroign activities. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(6), 926–943.10.1057/jibs.2008.89Search in Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Jabbour, L., & Zhang, L. (2016). Firm productivity and importing: evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Canadian Journal of Economics, 49(3), 1086–1124.10.1111/caje.12226Search in Google Scholar

Ethier, W. (1982). National and international returns to scale in the modern teory of international trade. American Economic Review, 72(3), 389–405.Search in Google Scholar

Fariñas, J. C., López, A., & Martín-Marcos, A. (2010). Foreign sourcing and productivity: Evidence at the firm level. The World Economy, 33(3), 482–506.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01264.xSearch in Google Scholar

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1999). The impact of outsourcing and high-technology capital on wages: Estimates for the United States, 1979–1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 907–940.10.1162/003355399556179Search in Google Scholar

Feng, L., Li, Z., & Swenson, D. L. (2016). The connection between imported intermediate inputs and exports: Evidence from Chinese firms. Journal of International Economics, 101, 86–101.10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.03.004Search in Google Scholar

Fernández, J., & Gavilanes, J. C. (2017) Learning-by-importing in emerging innovation systems: Evidence from Ecuador. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 26(1), 45–64.10.1080/09638199.2016.1205121Search in Google Scholar

Görg, H., Hanley, A., & Strobl, E. (2008). Productivity effects of international outsourcing: Evidence from plant-level data. Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(2), 670–688.10.1111/j.1540-5982.2008.00481.xSearch in Google Scholar

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2006). The rise of offshoring: It’s not wine for cloth anymore. In The new economic geography: Effects and policy implications. Jackson Hole Conference Volume, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (pp. 59–102).Search in Google Scholar

Head, K., & Ries, J. (2002). Offshore production and skill upgrading by Japanese manufacturing firms. Journal of International Economics, 58(1), 81–105.10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00161-1Search in Google Scholar

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching as an econometricevaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Review of Economic Studies, 64, 605–654.10.2307/2971733Search in Google Scholar

Hijzen, A., Inui, T., & Todo, Y. (2010). Does offshoring pay? Firm-level Evidence from Japan. Economic Inquiry, 48(4), 880–895.10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00175.xSearch in Google Scholar

Hummels, D., Jørgensen, R., Munch, J., & Xiang, C. (2014). The wage effects of offshoring: Evidence from Danish matched worker-firm data. American Economic Review, 104w(6), 1597–1629.10.1257/aer.104.6.1597Search in Google Scholar

Jabbour, L. (2010). Offshoring and firm performance: Evidence from French manufacturing industry. The World Economy, 33, 507–524.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01265.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kasahara, H., & Rodrigue, J. (2008). Does the use of imported intermediates increase productivity? Plant-level evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 87, 106–118.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.12.008Search in Google Scholar

Kedia, B. L., & Mukherjee, D. (2009). Understanding offshoring: A research framework based on disintegration, location and externalization advantages. Journal of World Business, 44(3), 250–261.10.1016/j.jwb.2008.08.005Search in Google Scholar

Kimura, E. (2002). Subcontracting and the performance of small and medium firms in Japan. Small Business Economics, 18, 163–175.10.1007/978-1-4615-0963-9_9Search in Google Scholar

Kugler, M., & Verhoogen, E. (2009). Plants and imported inputs: New facts and an interpretation. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 99(2), 494–500.10.1257/aer.99.2.494Search in Google Scholar

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 317–341.10.1111/1467-937X.00246Search in Google Scholar

Lewin, A., Massini, S., & Peeters, C. (2009). Why are companies offshoring innovation? The emerging global race for talent. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 901–925.10.1057/jibs.2008.92Search in Google Scholar

Lööf, H., & Andersson, M. (2010). Imports, Productivity and Origin Markets: The Role of Knowledge-intensive Economies. The World Economy, 33(3), 458–481.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01263.xSearch in Google Scholar

Máñez, J. A., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis, J. A. (2020). Foreign sourcing and exporting. The World Economy, 43(5), 1151–1187.10.1111/twec.12929Search in Google Scholar

Markusen, J. (1989). Trade in producer services and in other specialized intermediate inputs. American Economic Review, 79(1), 85–95.Search in Google Scholar

Merino, F., & Rodriguez, D. (2007). Business services outsourcing by manufacturing firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(6), 1147–1173.10.1093/icc/dtm034Search in Google Scholar

Mol, M., Van Tulder, R., & Beije, P. (2005). Antecedents and performance consequences of international outsourcing. International Business Review, 14(5), 599–617.10.1016/j.ibusrev.2005.05.004Search in Google Scholar

Muuls, M., & Pisu, M. (2009). Imports and exports at the level of the firm. The World Economy, 32, 692–734.10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01172.xSearch in Google Scholar

Olsen, K. B. (2006). Productivity impacts of offshoring and outsourcing: A review. OEDC, STI Working Paper 2006/1.Search in Google Scholar

Pane, D. D., & Patunru, A. A. (2023) The role of imported inputs in firms’ productivity and exports: Evidence from Indonesia. Review of World Economics, 159, 629–672.10.1007/s10290-022-00476-zSearch in Google Scholar

Rasciute, S., & Downward P. (2017). Explaining variability in the investment location choices of MNEs: An exploration of country, industry and firm effects. International Business Review, 26, 604–613.10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.12.002Search in Google Scholar

Requena, F., Serrano, G., & Mínguez, R. (2023). The enhancing effect of imports of intermediate inputs on firms’ exports. The World Economy, 46, 2654–2683.10.1111/twec.13467Search in Google Scholar

Roth, J. (2022). Pretest with caution: Event-study estimates after testing for parallel trends. American Economic Review: Insights, 4(3), 305–322.10.1257/aeri.20210236Search in Google Scholar

Sethupathy, G. (2013). Offshoring, wages, and employment: Theory and evidence. European Economic Review, 62, 73–97.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2013.04.004Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, C., & Mishra, R. K. (2015). International trade and performance of firms: Unraveling export, import and productivity puzzle. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 57, 61–74.10.1016/j.qref.2015.02.001Search in Google Scholar

Smeets, V., & Warzynski, F. (2013). Estimating productivity with multi-product firms, pricing heterogeneity and the role of international trade. Journal of International Economics, 90(2), 237–244.10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.01.003Search in Google Scholar

Sun, L., & Abraham, S. (2021). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 175–199.10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006Search in Google Scholar

Wagner, J. (2011). Offshoring and firm performance: Self-selection, effects on performance, or both? Review of World Economics, 147(2), 217–247.10.1007/s10290-010-0078-2Search in Google Scholar

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148, 235–267.10.1007/s10290-011-0116-8Search in Google Scholar

Young, A. (1991). Learning by doing and the dynamic effects of international trade. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 369–405.10.2307/2937942Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt