Abstract

Over the past decades, liquid biopsy, especially circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), has received tremendous attention as a noninvasive detection approach for clinical applications, including early diagnosis of cancer and relapse, real-time therapeutic efficacy monitoring, potential target selection and investigation of drug resistance mechanisms. In recent years, the application of next-generation sequencing technology combined with AI technology has significantly improved the accuracy and sensitivity of liquid biopsy, enhancing its potential in solid tumors. However, the increasing integration of such promising tests to improve therapy decision making by oncologists still has complexities and challenges. Here, we propose a conceptual framework of ctDNA technologies and clinical utilities based on bibliometrics and highlight current challenges and future directions, especially in clinical applications such as early detection, minimal residual disease detection, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. We also discuss the necessities of developing a dynamic field of translational cancer research and rigorous clinical studies that may support therapeutic strategy decision making in the near future.

Introduction

Liquid biopsy has gained prominence in biomedical research due to its non-invasive approach and the ability to detect biomarkers in body fluids, offering important insights for precision cancer medicine. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), first observed in cancer patients’ blood in 1989 [1], serves as a pivotal biomarker for various tumor evaluations. Recent progress in next-generation sequencing (NGS) and DNA methylation monitoring [2] has markedly improved the precision of ctDNA, underscoring its potential value in clinical practice. The integration of AI, particularly deep learning, has revolutionized ctDNA research [3], improving mutation and drug resistance predictions and enhancing treatment strategies. Additionally, with the increasing understanding of the tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy, the role of ctDNA in tumor immunotherapy has also attracted wide attentions.

Despite many advances in ctDNA research, its application in solid tumors is hindered by many challenges, such as technical difficulties related to ctDNA extraction and detection, standardization of clinical application, and data interpretation. Thus, we present a comprehensive review of the latest research progress in the application of ctDNA in solid tumors to provide a reference and inspiration for further research in this field. In this review, we use bibliometrics [4, 5] to shed light on the evolving trends with the utilization of ctDNA in the context of solid tumor applications. We provide a concise summary of ctDNA’s key characteristics, the most recent advancements in detection technologies, as well as an assessment of its merits and drawbacks. Our focus is on its pivotal role in early detection, the evaluation of minimal residual disease (MRD), and its significance in the evaluation of therapeutic response, particularly within the realms of immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Through this comprehensive exploration of ctDNA’s applications in solid tumors, our intention is to inspire further research and innovation within this field.

Development trends in ctDNA utility over the past decade – based on bibliometrics

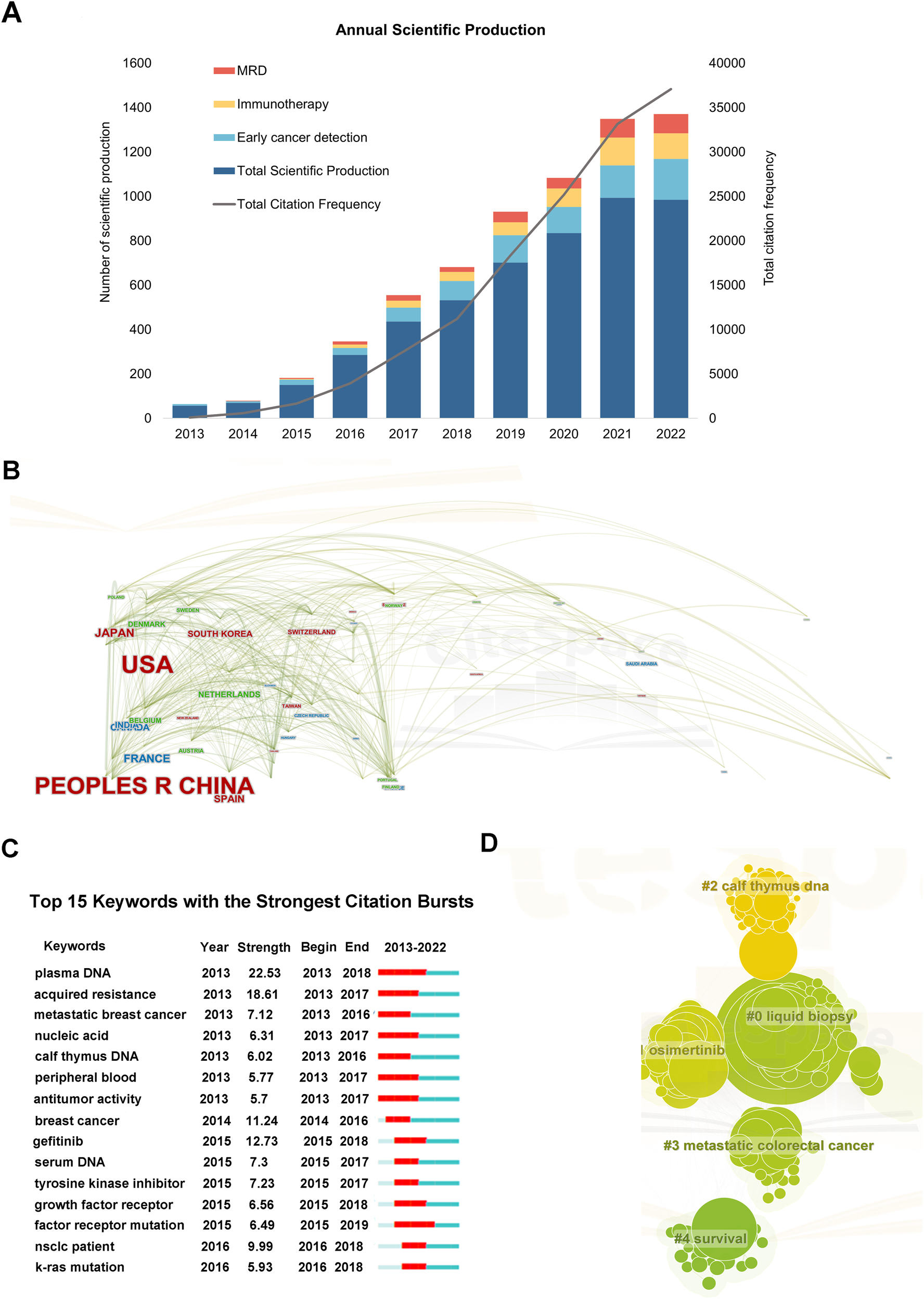

The dynamic changes in the number of papers over the past decade reflect the overall development trends and the scope of research in the field of ctDNA. From 2013 to 2022, the number of papers in this field has shown a significant upward trend, with relatively small fluctuations in the past two years, indicating foundational work in previous research (Figure 1A). Correspondingly, the citation frequency increased from 100 times in 2013 to 37,078 times in 2022, indicating increasing research depth and academic influence (Figure 1A). China ranked first in the number of publications (n=1233), followed by the USA (n=1094), with close collaboration between the two countries (Figure 1B). Analysis of corresponding authors’ countries revealed China’s weaker communication and collaboration with other countries in this field (Supplementary Table 1). The top 25 most globally cited documents on ctDNA research from 2013 to 2022 are listed (Supplementary Table 2). The journals Cancers and Clinical Cancer Research have the most publications and citations in ctDNA-related research, reflecting their academic influence and visibility in this field (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, Clinical Cancer Research has the highest Source Local Impact, indicating its high reputation and influence (Supplementary Table 4). The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center had the highest number of publications (n=393) (Supplementary Table 5). Keyword analysis revealed lung cancer as a significant research focus, with “diagnosis”, “prognosis”, and “recurrence” as hotspots. “Factor receptor mutation” is the most recent citation explosion keyword, with EGFR mutation as a prominent research area. ctDNA has gained attention as a liquid biopsy method for tumor diagnosis, monitoring efficacy, and evaluating prognosis. Lung cancer and factor receptor mutations are important in this field. ctDNA research and application are hotspots in oncology, expected to become important for tumor diagnosis, treatment selection, and prognosis evaluation as technology improves.

Bibliometric analysis of ctDNA-related documents from 2013 to 2022. (A) Annual scientific publication and total citation frequency from 2013 to 2022; (B) cooperation relationships of countries or regions; (C) top 15 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. A red bar indicates high citations in that year; (D) the co-occurrence network of keywords related to research on ctDNA from 2013 to 2022.

Origin and biological characteristics of ctDNA

Peripheral circulating free DNA (cfDNA) refers to DNA fragments in a free state detected in plasma or serum. These fragments are released into the bloodstream during processes such as necrosis, apoptosis, or cell disintegration, primarily resulting from the apoptosis of hematopoietic cells [6]. In healthy individuals, the cfDNA level is typically low. However, it rises with diseases, especially tumors or significant inflammatory responses. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to free DNA obtained from tumor cells, it can be detected in various bodily fluids like blood, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, and semen [7]. For most situations, blood holds the highest ctDNA concentrations due to its role as the main release channel for tumor cell-derived ctDNA, which can be obtained conveniently. This review mainly focuses on ctDNA in peripheral blood, which is about 0.01–10 % of total blood DNA.

CtDNA exhibits several distinct biological properties. Its length, between 134 and 144 bp, is generally shorter than tumor tissue DNA which is about 3.2 billion bp, and its half-life in blood is short, often between 16 min and 2.5 h [6], [7], [8]. As a dynamic biomarker, ctDNA is highly tumor-relevant and tissue-specific, spread throughout the blood with its level reflecting tumor burden and quickly entering the bloodstream post-release [9]. Its concentration depends on factors like tumor type, size, location, differentiation level, and the release and clearance rates in tumor cells. Thus, changes in its blood level can indicate tumor shifts, making it a key marker for evaluating tumor progress or therapy effectiveness.

CtDNA detection techniques

Even though the blood sample is noninvasive and accessible, the ctDNA test technology requires high accuracy and remains more breakthroughs in materials and analytical techniques. The ctDNA test is a noninvasive and highly sensitive method for detecting tumors. It analyzes the presence, amount, and mutations of tumor cells by studying ctDNA in the blood. Current detection methods include digital PCR (dPCR), BEAMing, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and plasma methylation assays. Digital PCR or Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR, a kind of dPCR) rapidly identifies DNA sequences even at extremely low concentrations [10]. However, the assay is limited in terms of expanding its capacity due to technical constraints, particularly droplet chip capacity. To improve result accuracy, automated sample preprocessing procedures must be enhanced to mitigate experimental challenges. BEAMing (Bead, Emulsion, Amplification, and Magnetics) can detect specific mutations in ctDNA and quantitatively analyze the amount of ctDNA in a sample [11]. This method may have limited use in clinical settings because it can only detect specific mutations, requires complex equipment and trained staff, and can be expensive for sample analysis. NGS possesses the remarkable ability to simultaneously analyze hundreds of target genes, highly applicable for tumor genomic and transcriptomic analysis, while its operation and data interpretation are typically complex [12]. Plasma methylation assays detect minute ctDNA amounts in whole blood, serum, and tissues, enabling the precise identification of whether ctDNA originates from tumor cells [13]. These assays hold potential for clinical diagnosis. However, the technique is limited to detecting specific tumor types and necessitates rigorous sample selection and quality control measures. To broaden the applicability and adaptability of the technique, more precise and stable analytical techniques and algorithms must be developed [14, 15].

Recent ctDNA research has introduced innovative testing techniques. Some of these approaches have undergone laboratory validation and are gradually advancing toward clinical application, while others remain in the research and exploration phase. Nanomaterial-based assays, like a graphene oxide-based platform and functionalized black phosphorus nanosheets, have shown high sensitivity in ctDNA detection. While the former efficiently isolates ctDNA cross-linked to collagen, the latter uses fluorescent probes selectively bind to ctDNA, skipping purified DNA extraction or PCR amplification. Both techniques offer potential for early tumor diagnosis and disease surveillance, ultimately enhancing relevant clinical treatment and prognosis [16]. Some methods use gene editing in conjunction with nanoparticles for ctDNA detection, but their widespread adoption and popularity in clinical applications is hindered by high cost and reliance on the nanomaterial characteristics.

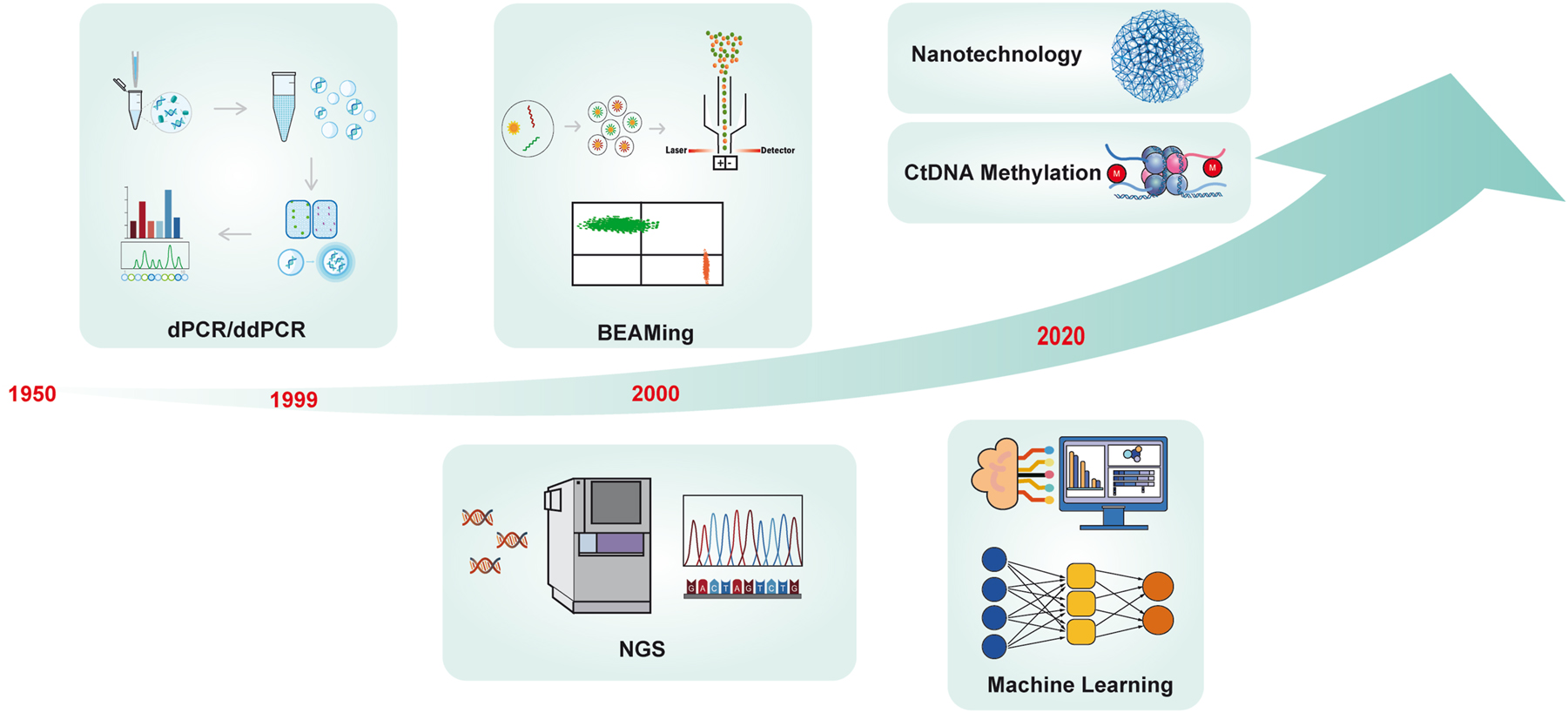

Besides nanomaterials, novel ctDNA detection approaches are being explored. Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques have been studied for quick, accurate ctDNA analysis. Ray et al. conducted a study on using specific biomarkers for noninvasive lung cancer detection. The research highlights DNA methylation analysis for cfDNA detection and the significance of combining artificial intelligence with this technique to improve the accuracy of lung cancer detection and provide individualized patient care [17] (Figure 2). Herein, the current challenges in ctDNA detection, such as achieving high sensitivity, specificity, and standardization, still pose significant hurdles. Overcoming technological limitations, navigating the complexities of tumor heterogeneity, and mitigating sample contamination are crucial aspects for clinical applications. The future exploration of ctDNA research encompasses not just advancements in sequencing technologies but also the integration of ctDNA into routine clinical practice based on liquid biopsy, the application of multi-omics approaches, the utilization of machine learning for data analysis, and the execution of large-scale clinical validation studies. The future objective is to establish ctDNA as a reliable and widely applicable biomarker, paving the way for enhanced early cancer detection, precise efficacy monitoring, and the development of personalized therapeutic interventions [18].

Timeline of the development of ctDNA technology. In 1948, Mandel and Metais discovered cell-free nucleic acid molecules (cfDNA) in plasma, and it was not until 1989 that Stroun reported that some cfDNA from tumor patients originated from tumor cells. KRAS mutations were first detected in blood cfDNA of pancreatic cancer patients using PCR in 1994. Afterward, dPCR technology appeared in 1999, and BEAMing appeared in 2006, which greatly improved the accuracy of ctDNA detection and pushed the research in related fields to the peak. Currently, with the emergence of new technologies, such as the popularity of NGS, DNA methylation detection, nanomaterials, artificial intelligence, and deep machine learning, ctDNA has many potential clinical applications waiting to be developed by researchers.

Areas of ctDNA clinical applications

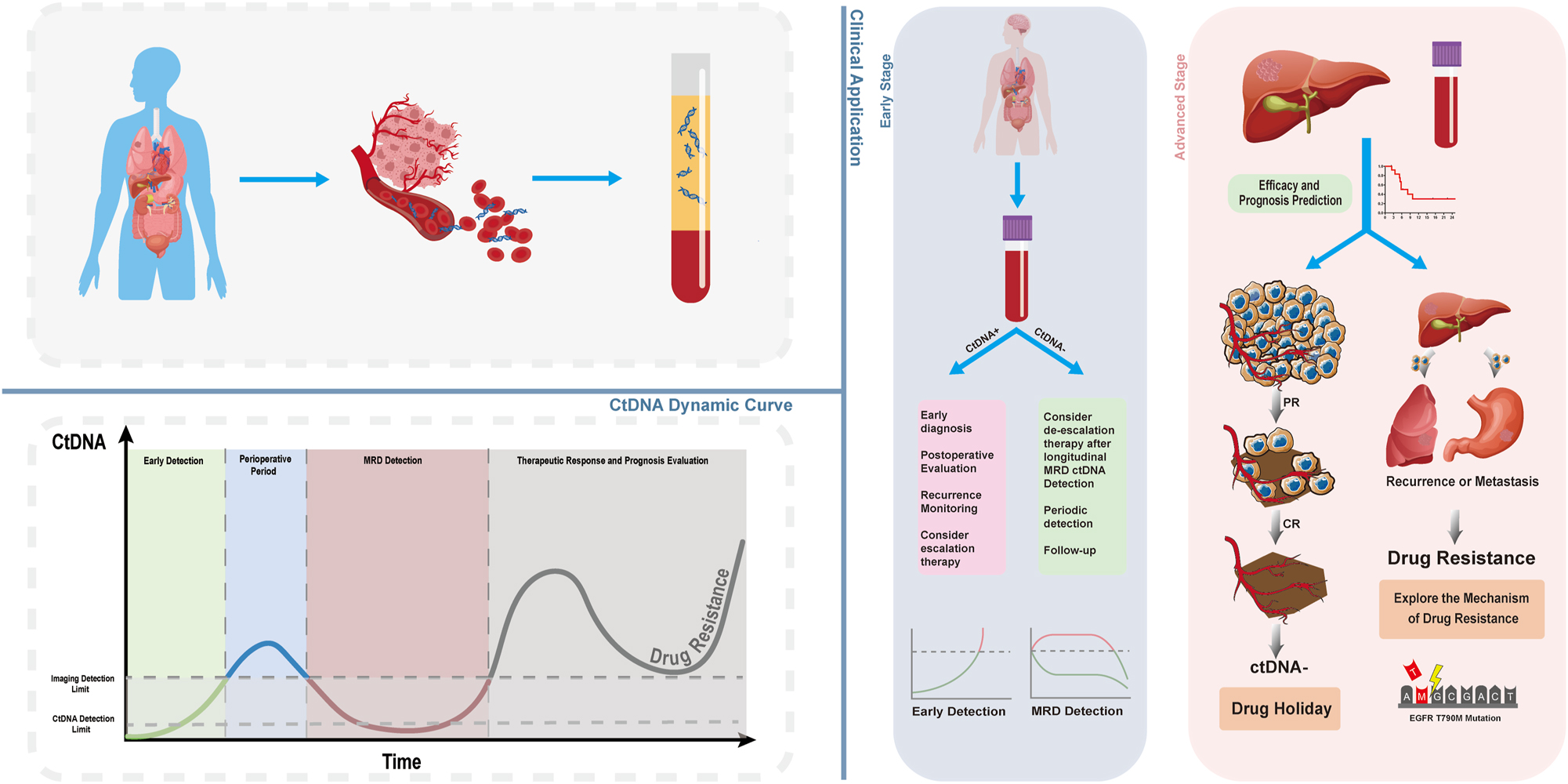

Unlike imaging and traditional tissue sample testing, ctDNA testing of blood samples offers a noninvasive and time-resilient approach in different clinical areas. This capability enables early tumor diagnosis, detection of minimal remaining lesions or recurrence, real-time monitoring of treatment response, prediction of patient prognosis, enhanced treatment plan formulation, and support for individualized treatment. Consequently, the application and utilization of ctDNA technology in clinical practice hold great promise (Figure 3).

Dynamic changes of ctDNA and its clinical application. As cancer develops and is treated, the levels of ctDNA in the body undergo dynamic changes. CtDNA detection technology can indicate disease changes ahead of traditional imaging. Initially, ctDNA levels in the body are too low to be detected by either imaging or ctDNA detection technology; thus, the disease is in a hidden stage. When ctDNA levels reach a detectable threshold, the tumor may still be unidentifiable by imaging, making ctDNA detection technology suitable for preclinical early screening. Following the surgical removal of early-stage tumors, the lesions are unobservable by imaging, but ctDNA can still be detected in the body, entering the stage of minimal residual disease (MRD) detection. By continuously monitoring ctDNA-MRD over time, postoperative prognosis can be evaluated, and a dynamic increase in ctDNA may predict disease recurrence or metastasis in advance. Notably, when ctDNA is undetectable, a state we refer to as MRD negative, treatment for the patient can be temporarily halted, a period known as a “drug holiday”. In late-stage cancer treatment, ctDNA can indicate patient response. When a tumor develops resistance, particularly in targeted and immunotherapies, the genetic information of the tumor reflected by ctDNA may provide reasons for the tumor’s resistance, paving the way for new approaches to overcome tumor resistance.

Early detection and diagnosis

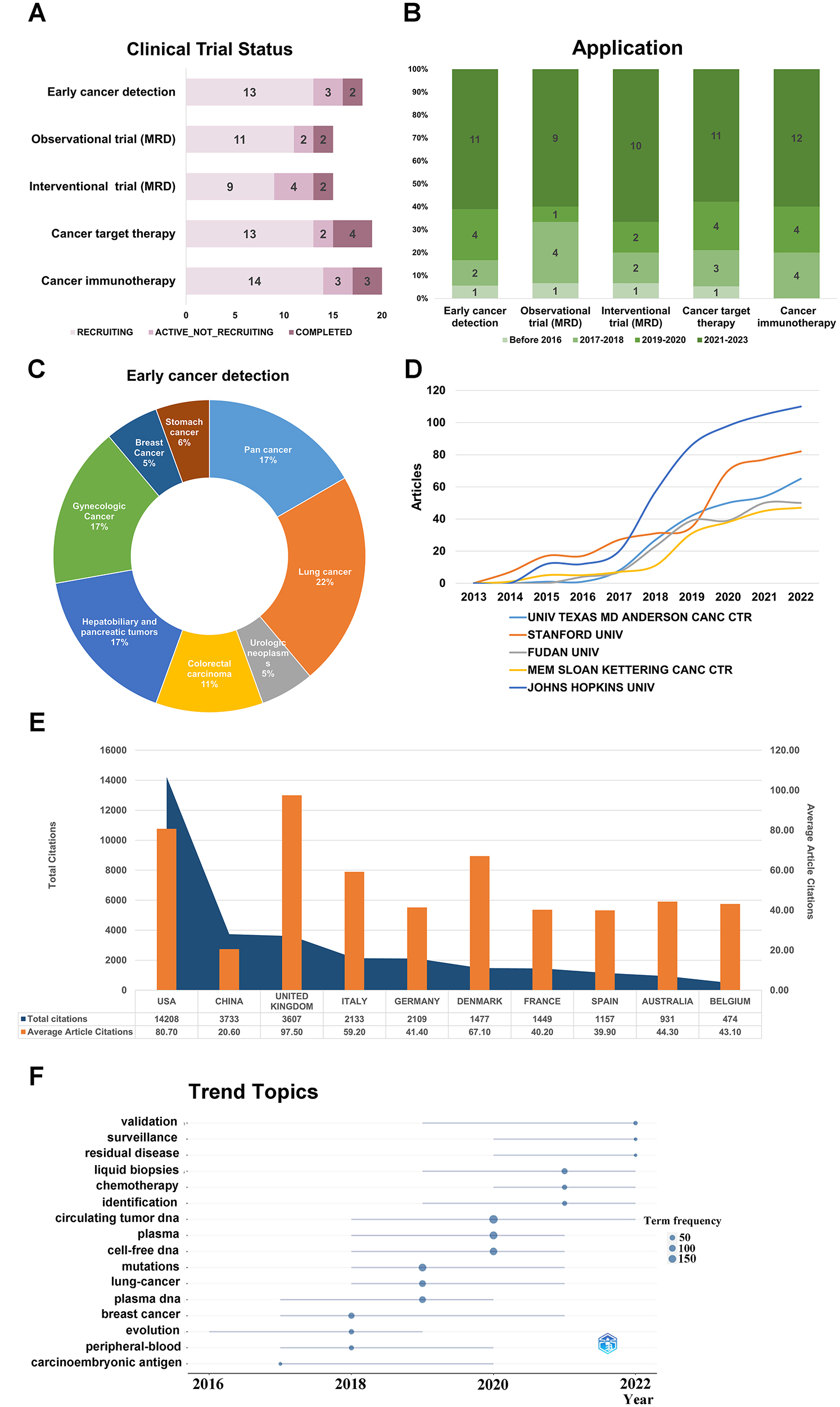

CtDNA harbors significant potential as a molecular beacon for the early detection of various cancer types, often preempting disease onset earlier than traditional imaging modalities and clinical symptomatology. Characterized by its high sensitivity and noninvasive nature, this approach encapsulates a comprehensive spectrum of tumor-specific information, thus serving as a robust tool in the early cancer detection landscape [19]. As one of the means of early screening, ctDNA has achieved many results in clinical trials of solid tumors. According to the statistical results, we found that there are 18 clinical trials related to early cancer detection as observational studies (Figure 4A), among which 13 clinical trials are currently recruiting participants. Compared to several other clinical applications of ctDNA, the clinical trials related to early cancer detection were initiated earliest (Figure 4B), and they involved the most diverse solid tumor types, with lung cancer-related trials being the most numerous (22 %) (Figure 4C). These clinical trials utilizing ctDNA for early cancer detection will provide guidance and reference for further research and applications.

CtDNA related clinical trials and bibliometric analysis of literature on early detection and ctDNA. CtDNA clinical trial programmes by clinical trial status (A) and clinical trial start date (B). (C) In the clinical trials which ctDNA is applied for early cancer detection, the distribution of tumor types. (D) Annual scientific production of the top 5 affiliations; (E) total citations and average article citations for the top 10 countries; (F) trend topic analysis.

In the case of common cancers like breast and colorectal cancer, ctDNA detection has become the standard approach for medical practice. A study conducted by K. Page et al. [20] aimed to investigate the occurrence of ctDNA in early-stage 1 and stage 2 breast screening. The results showed that ctDNA was detected in 14.3 % of the patients. Although the low percentage of ctDNA-positive results suggests that relying solely on ctDNA for early breast cancer detection may not be highly effective as a supplement to mammography, this personalized ctDNA approach might be useful in monitoring post-surgery patients or those with detectable cfDNA initially. In colorectal cancer (CRC), S. Mo et al. [21] introduced the ColonES assay, a precise method for early detection. It distinguished CRC or advanced adenoma patients from healthy ones with high accuracy and sensitivity (a sensitivity of 79.0 % for AA and 86.6 % for CRC, with a specificity of 88.1 % in healthy individuals), especially noting poorer outcomes in patients with elevated ctDNA methylation levels.

In addition to these applications, ctDNA holds promise for the detection and management of less common or rare cancers. For pancreatic cancer, often diagnosed late, Liu et al. [22] found ctDNA can detect early-stage disease with impressive accuracy by detecting the combination of KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, SMAD4 mutations. These small mutant fragments, especially 75–85 bp for KRAS G12D, are more prevalent in early stages, differing from the 150 bp peak in advanced ones, suggesting a detection method based on fragment sizes. Beyond traditional ctDNA detection, methylation analysis elevates its application in early screening. DNA methylation, a widely researched epigenetic modification, is linked to tumorigenesis, even in precancerous stages. This suggests its use as an early biomarker, a claim recent studies validate [23]. Wu’s team [24] analyzed whole-genome methylation profiles and formulated a method for early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma detection. The PDACatch-based classifiers showed 76–82 % sensitivity for early-stage PDAC, aligning with other studies using DNA methylation as cancer biomarkers. In lung adenocarcinoma detection, ctDNA-based high-throughput DNA methylation sequencing complements LDCT screening. WH Liang’s team [25] devised a model distinguishing malignant from benign pulmonary nodules by comparing DNA methylation patterns. Applied to plasma samples, it displayed robust sensitivity and specificity for early-stage lung cancer. Furthermore, combining machine learning with deep methylation sequencing enhances detection of minuscule ctDNA amounts, vital for cancer screening and treatment assessment. Naixin Liang et al. [26] highlighted that this method detects tumor signals in dilutions as low as 1 in 10,000, accurately pinpointing 52–81 % of patients in stages IA to III, and doubling detections in a subgroup, surpassing ultradeep mutation sequencing.

Based on the aforementioned applications, it is worth noting that ctDNA has garnered significant attentions as an emerging tumor marker. Therefore, we conducted a bibliometric analysis of the literature on ctDNA and early cancer detection to provide insights for further research. We found 790 articles published in this field over the past decade, with a consistent increase in the number of articles and citations each year (Figure 1A). Johns Hopkins University had the highest publication volume with 39 articles (Figure 4D). The United States had the highest overall publication volume, followed by China, but the average article citations in China were lower, indicating room for improvement in the quality and influence of papers from China (Figure 4E). The trending topics in 2022 were validation, surveillance, and residual disease. Validation research focused on verifying the reliability of ctDNA testing for clinical use, surveillance research aimed to monitor tumor progression, and residual disease research focused on detecting and treating residual disease to improve treatment outcomes (Figure 4F). The top 10 most cited documents in ctDNA and early detection research are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

In summary, ctDNA testing holds significant promise in the areas of validation, surveillance, and residual disease monitoring within the clinical context. The increasing research and heightened interest in this field point toward ongoing developments that will enhance our capabilities for early cancer detection and treatment. This progress extends not only to common cancers but also offers potential benefits for the detection and management of rarer malignancies. With rigorous randomized controlled trials supporting its application, ctDNA research is steadily advancing, marking substantial strides in the realm of cancer diagnostics.

CtDNA MRD detection

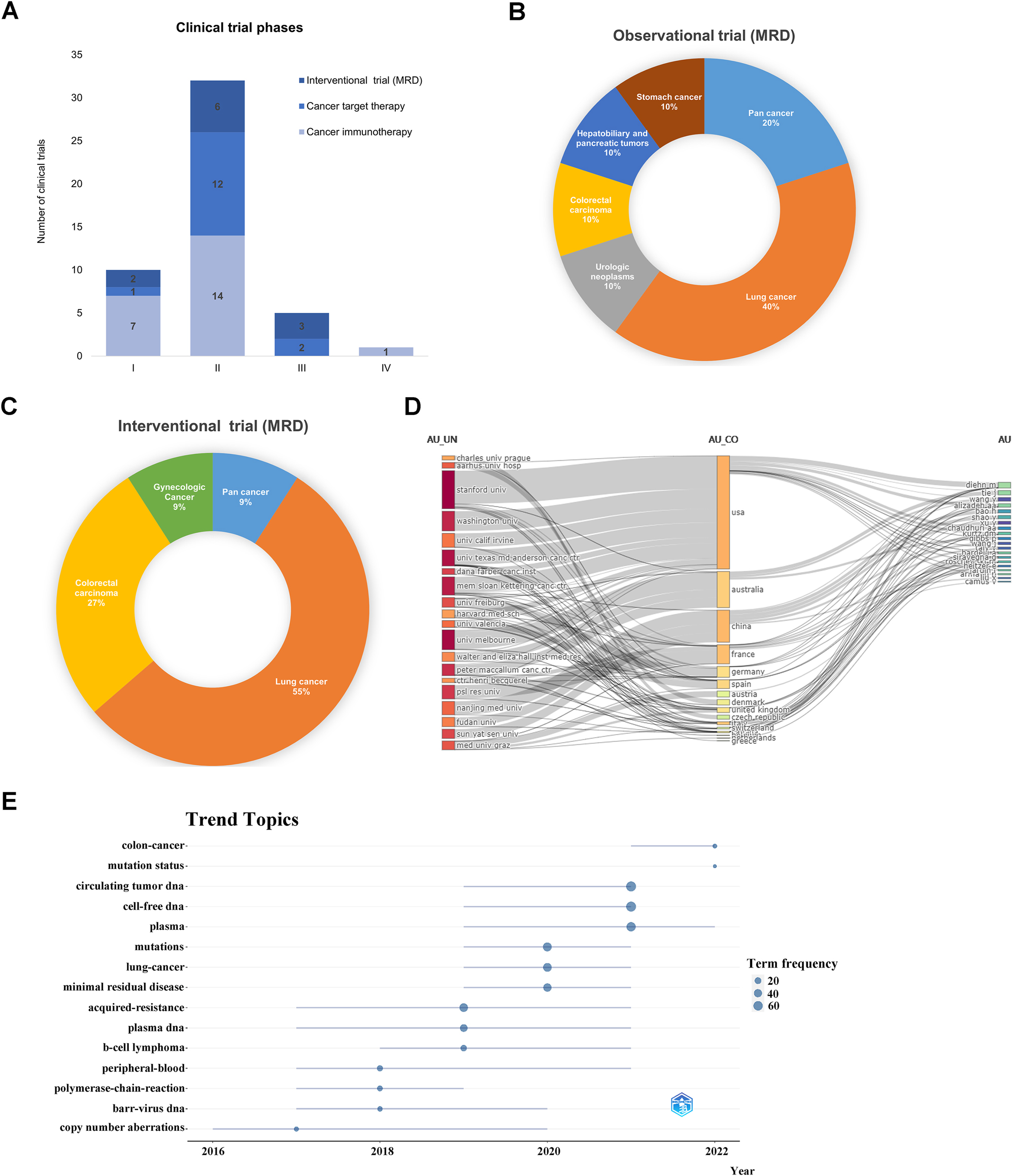

Minimal residual disease (MRD) refers to the tiny number of cancer cells left in the body during or after treatment. These cells are detectable only through highly sensitive methods capable of identifying a single cancer cell among a million normal cells [27]. With advances in liquid biopsy technology, ctDNA has become a vital tool in MRD monitoring. While MRD testing is primarily used for blood cancers like lymphoma and leukemia [28], recent clinical trials have expanded its use in monitoring recurrence, risk assessment, treatment efficacy, and prognosis for solid tumors. Currently, most clinical trials on MRD are ongoing, while a few have already been completed, such as the DYNAMIC trial for colorectal cancer(ACTRN12615000381583) [29] (Figure 4A). There has been a noticeable increase in the number of clinical trials conducted in the past three years (Figure 4B). Lung cancer studies predominantly comprise observational trials (40 %) and interventional trials (55 %) (Figure 5B and C). Interventional trials are mainly in Phase II [6], followed by Phase III [3] and Phase I [2] (Figure 5A). The analysis of these clinical trials highlights the growing understanding and emphasis on MRD as an evolving concept in cancer treatment and monitoring. With an increasing number of MRD clinical trials, there are more opportunities to assess its value in guiding treatment decisions and prognostic assessment. Assessing and monitoring MRD enables precise individualized treatment approaches, leading to improved treatment outcomes and survival rates. This trend reflects the growing importance of MRD in the medical community and its potential to play a crucial role in future cancer treatments.

Clinical trials and bibliometric analysis of the literature on MRD and ctDNA. (A) CtDNA clinical trial programmes by clinical trial phases. (B and C) The distribution of tumor types in the clinical trials which ctDNA is applied for observational and interventional trial (MRD). (D) Sankey of universities, countries, and authors. (E) Trend topic analysis.

The clinical significance of ctDNA in MRD is increasingly recognized based on growing evidence. We conducted a bibliometric analysis of 334 relevant articles from 2013 to 2022, revealing an overall increase in publications since 2016 (Figure 1A). The US and China rank highest in publications and influence, but Chinese scholars as corresponding authors (MCPs) have a low proportion (Supplementary Table 7). This calls for stronger collaboration and exchange with other countries to enhance research impact. Analysis of institution-country and author collaborations highlights US engagement and China’s further potential with Nanjing University, Fudan University, and Sun Yat-sen University leading in China (Figure 5D). These results support the need for collaborative studies, emphasizing the importance of teamwork. The top ten most cited publications are provided in Supplementary Table 8, with top journal rankings in Supplementary Table 9 indicating emerging status and acceptance challenges of ctDNA in MRD research. Trending topics include cell-free DNA, ctDNA, mutation status, while colon cancer remains an intense focus (Figure 5E). Overall, ctDNA and MRD research contribute to advancements in tumor diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and prognosis assessment. Further technological advancements and research will deepen our understanding in the future.

Tumor-informed and tumor-naive sequencing assays for ctDNA MRD detection

Current sequencing assays for ctDNA detection include tumor-informed and tumor-agnostic assays [30]. The tumor-informed assay is tailored based on individual tumor tissue characteristics, while the tumor-agnostic approach uses preset genetic panels to identify specific tumor genes in blood [31]. At ASCO 2021, Japanese researchers used a personalized panel of over 4,000 genes on 400+ patients. Only 17 % of two patients had the same gene, and less than 5 % among three or more patients, highlighting significant tumor heterogeneity [32]. Therefore, tumor-informed assays cater to this heterogeneity, offering a precise method for MRD detection. In a trial comparing these assays in colorectal cancer patients, of the 5,835 variants detected, only 344 (6 %) were identified by the fixed panel [33]. Furthermore, when various assays were evaluated on breast cancer plasma samples, tumor-informed tests demonstrated superior sensitivity in detecting low-concentration ctDNA [34].

Landmark vs. surveillance ctDNA MRD analysis

Wu’s team studied MRD dynamics post-surgery, categorizing monitoring into two periods: landmark (1–3 months post-surgery) and longitudinal (every 3–6 months thereafter) [35]. The research emphasized continuous monitoring over a single time point. Even with negative MRD at the landmark, some patients still faced recurrence. However, consistent negativity during longitudinal monitoring showed a minimal risk of recurrence. The study recommends continuous monitoring every 3–6 months after the landmark for at least 18 months. For MRD-positive patients, postoperative adjuvant therapy improves survival. For MRD-negative patients, the benefit of this therapy is inconclusive, with no significant survival difference noted in this small-scale study. Beyond assessing tumor progression, longitudinal ctDNA profiling through NGS offers insights into prognostic monitoring and tumor-related genome changes [36]. In essence, post-surgical MRD monitoring should be continuous. Regular monitoring accurately assesses recurrence risk, and while adjuvant therapy is advised for MRD-positive patients, its necessity for MRD-negative patients remains uncertain.

Advanced cancer treatment strategies based on MRD – drug holidays

Tumor evolution theory suggests that antitumor therapy creates selection pressure, causing sensitive tumor cells to reach evolutionary dead ends, while a few drug-resistant clones lead to progression [37]. The drug holiday model limits this pressure, preserving sensitive clones and inhibiting the growth of drug-resistant clones. Consequently, when tumors recur, retreatment remains effective [38]. Thus, patients may not need the maximum drug dose or lengthiest treatment, with minimal necessary treatment being optimal [39]. Wu’s team introduced a new approach – drug holidays based on MRD detection – using MRD and CEA as indicators for subsequent interventions [40]. Their research shows that adjusting drug treatment based on MRD levels can notably extend PFS, encouraging further exploration of drug holiday strategies.

Challenges and prospects related to MRD

There remain challenges for MRD assessment’s broader clinical adoption. A meta-analysis revealed ctDNA’s low specificity but high sensitivity in lung cancer prognosis, largely attributed to its low detection rate [41]. This is because tumors, at the MRD detection stage, generally have a lower load and some don’t readily release ctDNA into the blood. Despite its prognostic significance, ctDNA’s low detection rate makes it insufficient for sole use in prognosis models. It’s often paired with other biochemical markers, like CMS or white blood cells, though a standardized approach is lacking [42, 43]. Anders K. M. Jakobsen et al. [44] introduced “ctDNA-RECIST” criteria, awaiting further validation. Plasma MRD monitoring for brain metastases is restricted due to the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers, making plasma unreflective of intracranial conditions. Meichen Li’s study [45] indicated that CSF ctDNA fluctuations better predict intracranial tumor responses in NSCLC patients with brain metastases. The technology and prognostic value of cerebrospinal fluid ctDNA in such cases warrant deeper investigation.

CtDNA and targeted therapy

With advancing detection technology, the monitoring and analysis of plasma ctDNA are increasingly utilized in personalized treatment for various types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and pancreatic cancer. After the initiation of targeted therapy for advanced solid tumors, quantitative and dynamic analysis of ctDNA levels based on NGS detection is expected to emerge as a promising approach for evaluating treatment efficacy. Upon conducting a comprehensive analysis of clinical trials related to ctDNA and targeted therapies, we have observed that clinical trials related to targeted therapy rank second, just behind immunotherapy [19] (Figure 4B). Currently, 4 trials have completed recruitment, while 13 trials are actively recruiting patients, with most being in Phase II (Figure 5A). Lung cancer trials have the highest representation (27 %), followed by breast carcinoma and colorectal carcinoma (21 % each) (Supplementary Figure 1A). These trials aim to provide more precise and individualized treatment options for ctDNA positive patients. Targeted therapies, focusing on specific oncogenic molecules or signaling pathways, strive to enhance treatment effectiveness and extend patient survival. This personalized treatment approach brings new hope and overcomes limitations of traditional therapies in cancer treatment.

CtDNA in the prediction of therapeutic efficacy

The FLAURA study analyzed ctDNA at disease progression in two arms (osimertinib vs. gefitinib/erlotinib). Results indicated osimertinib led to better overall survival (OS) than EGFR-TKIs. Patients with undetectable EGFR mutations in ctDNA at baseline showed longer progression-free survival (PFS) than those with detectable baseline mutations, suggesting osimertinib’s efficacy in first-line treatment of EGFR-mutated NSCLC. It implies superior overall survival and tolerability of osimertinib in such cases [46]. While ALK fusion detection via liquid biopsy is not as sensitive as for EGFR, its noninvasive nature permits frequent blood tests. ALK rearrangements, mainly in adenocarcinomas, appear in 3–5 % of NSCLC patients [47]. Two studies have shown that the Guardant360 assay reliably identifies ALK fusions in NSCLC patients with TKI-resistant ALK disease [48, 49]. ROS1 rearrangements are commonly detected by FISH or NGS. DNA-based NGS is more prone to false negatives than RNA-based ones. Few explored plasma genotyping for ROS1-positive NSCLC [50]. A study using Guardant360 NGS for ROS1-positive NSCLC highlighted its potential in spotting mutations causing resistance to ROS1 therapies [51]. BRAF mutations are prevalent in cancers like melanoma and colorectal cancer. A study on plasma ctDNA analysis for BRAF mutation revealed BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment based on liquid biopsy results significantly boosted survival in patients with BRAF V600E-positive mCRC, but was less effective in other cancers. It offers new treatment alternatives and affirms the clinical utility of BRAF testing in liquid biopsies [52]. Similar to BRAF, KRAS and NRAS mutations are widespread in cancers. A study by Pinheiro and Peixoto et al. assessed KRAS and NRASgene mutation analysis of ctDNA in the plasma of patients with mCRC. It emphasized their significance in prognosis and treatment response, and presented a noninvasive method for detection, providing new ideas for personalized mCRC treatments [53].

We reviewed prior studies to grasp trends in ctDNA and targeted therapy research. Five chief tumor mutation targets in ctDNA emerged: EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, MET, and Her2, with applications spanning clinical practice [54, 55]. EGFR and ctDNA research began earliest, peaking in 2019, while Her2 and ctDNA studies have risen consistently, signaling its rising prominence (Supplementary Figure 1B).

CtDNA and drug resistance

Drug resistance is a significant clinical challenge. Liquid biopsy advancements allow real-time tumor drug resistance tracking. CtDNA testing, a rapidly evolving liquid biopsy technology, discerns tumor progression and drug resistance through blood-based tumor biomarkers.

Although targeted therapy focuses on molecular targets within tumor cells, resistance frequently emerges, impeding the effectiveness of the treatment. Hence, early resistance detection via ctDNA can aid in adjusting the therapeutic strategy for better outcomes. Firstly, the T790M mutation is a well-established resistance mutation observed in response to both first and second-generation TKIs [55]. Osimertinib has emerged as a prominent therapeutic option for advanced lung cancer patients harboring the EGFR T790M mutation, as demonstrated by recent pivotal studies consistently highlighting its effectiveness as a first-line treatment [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62]. In clinical practice, when utilizing ctDNA genetic testing for NSCLC patients undergoing first-line osimertinib treatment, the primary objective is now on identifying potential co-mutations in EGFR-positive NSCLC, as certain co-mutations may be closely linked to resistance against EGFR-TKIs. Evaluating the status of these co-mutations becomes crucial for guiding treatment decisions, necessitating a personalized approach to combination therapy [63, 64]. Secondly, BRAF V600E, linked to BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma, was first detected in colon cancer via ctDNA in 2010 [65]. Other significant mutations include PIK3CA H1047R in breast cancer, KRAS G12C in lung cancer, and ALK F1174L and MET Y1230C both associated with their respective inhibitor resistances [66], [67], [68], [69]. Some mutation targets remain underexplored, potentially due to their rarity. Overall, ctDNA offers early tumor resistance detection, informs clinical decisions, and underpins personalized treatment. Research volume on ctDNA and targeted therapy resistance mutations is shown in Supplementary Figure 1C (Supplementary Table 11).

Although osimertinib is currently considered the standard first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC, many still opt for first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs. EGFR T790M mutations during progression are one of the common mechanisms of resistance in EGFR-TKI therapy. J Remon et al.’s study, which combined ctDNA assay technology to explore the relationship between T790M mutations and response to osimertinib treatment, indicated better outcomes for T790M-positive patients and treatment-related ctDNA decreases with extended patient progression-free survival [70]. In another study, the researchers’ analysis of ctDNA in the blood of lung cancer patients at different times identified BRAF mutations and resistance mechanisms post-BRAF therapy through ctDNA [71] In HER2-positive breast cancer, drug resistance is common. In a particular study, plasma ctDNA was quantified through the prospective collection of plasma samples from patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and were being treated with oral anti-HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The findings suggested that longitudinal gene panel ctDNA sequencing can be used to determine drug resistance and guide the precise use of anti-HER2-targeted therapy in the setting of metastasis [72]. An important study published in Lancet Oncology was the first to establish that adjusting endocrine treatments based on ctDNA findings leads to an improvement in progression-free survival among breast cancer patients [73]. Through experiments on lung cancer cell lines and mouse models, the KRAS G12C mutation was found to enhance EGFR inhibitor resistance, promote tumor cell growth and survival and activate ERK and AKT pathways in lung cancer. This suggests that real-time ctDNA analysis could potentially optimize treatment by timely adjustments [74].

In summary, ctDNA analysis serves as a potent tool for evaluating targeted therapy outcomes across various cancers. It adeptly monitors prognosis and personalizes treatments but is unable to detect the emergence of previously unidentified mutations. This limitation affects ctDNA’s efficacy prediction in targeted therapies, necessitating deeper research into drug resistance mechanisms in forthcoming years.

CtDNA and immunotherapy

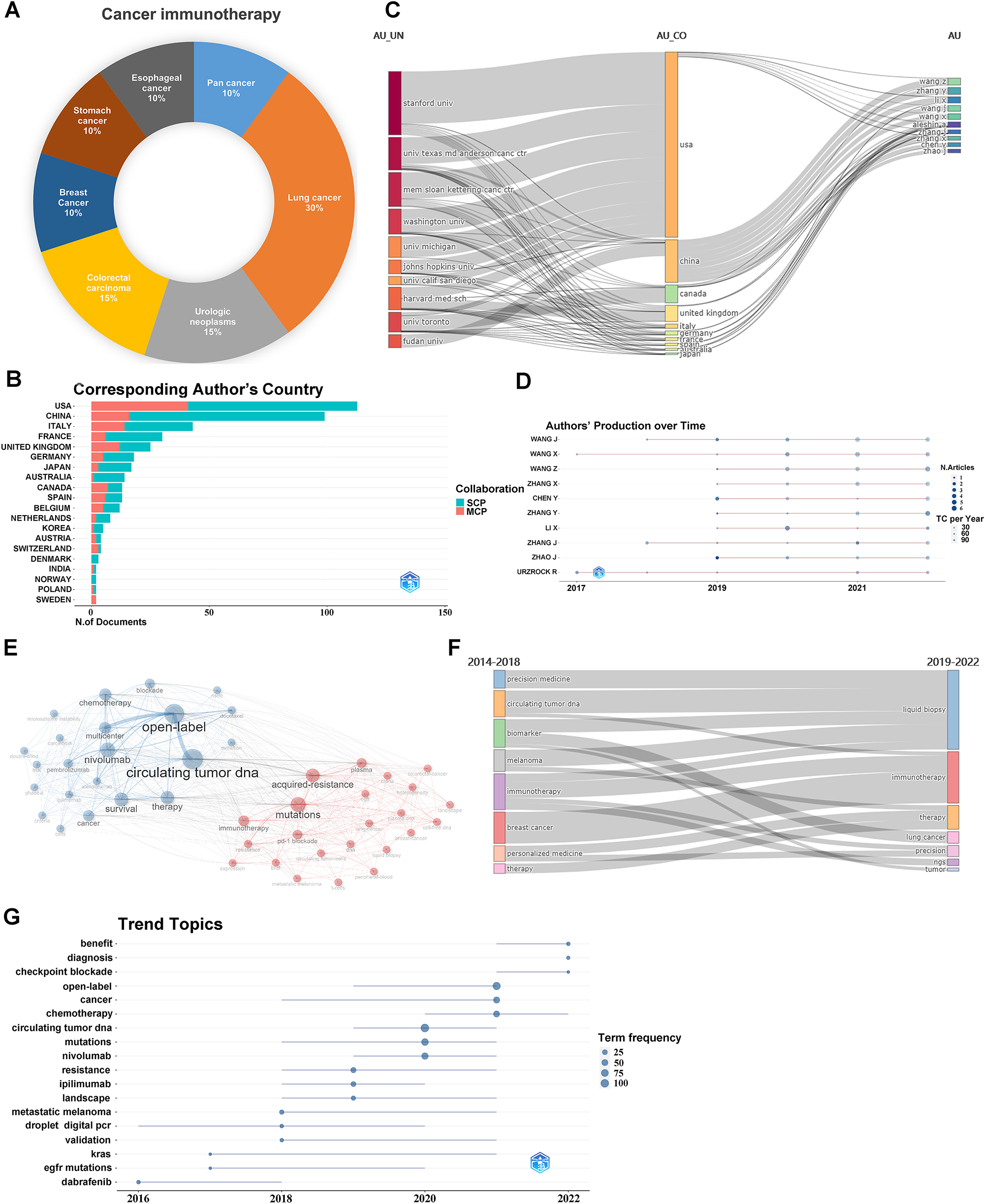

Immunotherapy (ICI), an emerging area of oncology treatment, has been shown to improve survival in a wide range of solid tumors and is increasingly becoming a routine treatment option for many tumors. An important advantage of immunotherapy is that it activates the body’s immune cells and enhances the body’s antitumor immune response, thereby causing the death of tumor cells and releasing ctDNA fragments. These ctDNA fragments reflect the effectiveness of treatment and the variability of tumor cells, so the use of ctDNA testing and analysis can help in establishing better individualized treatment regimens and more accurately assessing the effectiveness of immunotherapy and patient disease progression [75]. Numerous ctDNA-based immunotherapy clinical trials, primarily focused on cancer, have been conducted. Three trials have completed recruitment, while 14 trials are actively recruiting patients (Figure 4A). Over the past three years, 12 clinical trials specifically targeting cancer immunotherapy have been conducted (Figure 4B). Most trials are in Phase II, followed by Phase I. Additionally, one Phase IV trial focusing on lung cancer is ongoing (Figure 5A). These trials aim to evaluate the potential of ctDNA as a prognostic indicator for immunotherapy response and identify eligible patients based on ctDNA mutation burden. Ongoing trials will shed further light on the role and potential benefits of immunotherapy in ctDNA-related cancers, enhancing guidance and evidence for future clinical applications. The studies aim to evaluate long-term effectiveness, safety, and real-world outcomes of immunotherapy in a larger patient population, refining treatment strategies and identifying patient subgroups who may derive maximum benefit from this approach.

A total of 472 immunotherapy-related articles were found from 2013 to 2022, demonstrating an increasing trend, reaching its peak between 2019 and 2022 (Figure 6A). In terms of publications, the United States took the lead, followed by China (Figure 6B). Stanford University holds a prominent position, and the majority of the top ten authors are from China (Figure 6C and D). The top ten journals with the highest Source Local Impact are provided in Supplementary Table 12, with Clinical Cancer Research being an influential and renowned journal in the field. Co-occurrence analysis of keywords reveals a close connection between ctDNA and open label and multicenter clinical trials in clinical applications, while immunotherapy is closely associated with acquired resistance and mutations (Figure 6E). Supplementary Table 13 presents the top ten most cited documents on ctDNA and immunotherapy research. Research themes evolution (Figure 6F) demonstrates that from 2014 to 2018, there was a rise in exploring the relationship between ctDNA and immunotherapy, specifically focusing on the biomarker value of ctDNA and its application in melanoma and breast cancer immunotherapy. From 2019 to 2022, the research shifted toward the combined use of ctDNA and immunotherapy, with a particular emphasis on monitoring ctDNA during immunotherapy, investigating its role in tumor immunotherapy resistance mechanisms, and exploring current hotspots and trends in lung cancer research (Figure 6G). In conclusion, there are currently limited biomarkers available for effectively predicting the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. CtDNA, as a non-invasive detection method, can effectively identify beneficiaries across different types of cancer treated with ICIs, demonstrating significant potential for future applications.

Clinical trials and bibliometric analysis of the literature on immunotherapy and ctDNA. (A) The distribution of tumor types in the clinical trials which ctDNA is applied for cancer immunotherapy; (B) corresponding authors’ countries, MCP represents the number of papers coauthored by authors from different countries, while SCP represents the number of papers coauthored by authors from the same country; (C) Sankey; (D) scientific production over time of the top 10 authors; (E) keyword cluster analysis; (F) thematic evolution.

CtDNA and clinical outcome prediction

Immunotherapy enhances survival in oncology patients, yet only a portion benefit long-term. This emphasizes the need for biomarkers to identify potential responders. While approved biomarkers include PD-L1 high expression, MSI-H, and TMB-H, they don’t allow dynamic evaluations of immunotherapy efficacy, urging the discovery of new biomarkers. CtDNA testing, being noninvasive and repeatable, potentially fulfills the need for real-time monitoring of patient response and tumor burden. Trevor J. Pugh and Lillian L. Siu’s team established a link between ctDNA levels and patient response to immunotherapy. Their study of 106 patients revealed that those with lower baseline ctDNA exhibited better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Additionally, a more favorable clinical benefit rate (CBR) and objective remission rate (ORR) were observed in patients with low baseline ctDNA levels [76]. Retrospective analyses highlighted that changes in variant allele frequencies (VAF) identified by ctDNA testing can predict durvalumab’s clinical benefit in lung and bladder cancer patients. In this study, 96 % patients showed somatic mutations by ctDNA testing and the testing results showed that early VAF changes preceded imaging [77, 78]. Furthermore, ctDNA molecular responses serve as early efficacy indicators for immunotherapy [79, 80]. Early ctDNA reduction (as soon as 4 weeks into treatment) indicated longer survival benefits, with a median OS 29.21 vs. 9.4 months in the ctDNA decrease and ctDNA increase groups, respectively This suggests that dynamic testing of ctDNA, with real-time monitoring of efficacy, provides important information for timely adjustment of treatment strategies for patients. CtDNA dynamic assessment can be a powerful complement to imaging assessment of efficacy while providing a time lead when using ctDNA for assessment [81].

Although imaging remains pivotal for treatment decisions, it can’t always detect pseudoprogression – a misleading sign of transient tumor growth during immunotherapy. This maybe wrongly interpreted as treatment failure but stems from immune cells targeting tumor cells, causing a heightened tumor inflammatory response, resulting in an increase in the volume and metabolic activity of the tumor foci [82]. Although the incidence of pseudoprogression is low, it is a major challenge for immunotherapy, and if it occurs and is then misdiagnosed, it may misguide treatment decisions. One study confirmed that ctDNA profiling in metastatic melanoma patients treated with PD-1 antibodies could discern between pseudoprogression and true progression [83]. Consequently, RECIST assessments alone are not fully reliable for predicting outcomes with ICI [84], urging a combined approach of ctDNA and imaging for a comprehensive patient outcome evaluation.

Genetic determinants of immunotherapy

Research indicates that the tumor mutational load (TMB) holds promise as a predictive biomarker for the immunotherapy of various solid tumors, though its predictive utility in clinical practice requires more prospective evaluations [85]. The prevalent method of measuring TMB is via tumor tissue TMB (tTMB), but this method is not only constrained by material availability but also the results can be affected by intratumor heterogeneity and might evolve with treatment [86]. An alternative, the blood-based TMB (bTMB) assay, overcomes these challenges the problem of difficult sampling and by enabling dynamic detection to addressing the challenge of tumor heterogeneity [87, 88]. The inaugural validation of bTMB confirmed its efficacy in predicting immunotherapeutic outcomes. Two studies, POPLAR and OAK, analyzed over 1000 blood samples from NSCLC patients. As with tTMB, there is an association between high bTMB scores and identifying associations between high bTMB scores and better ORR and improved PFS and OS in patients with NSCLC [89, 90]. Another key efficacy predictor for solid tumor immunotherapy is MSI status. Notably, patients with dMMR/MSI-H statuses can benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors irrespective of the cancer type. A significant cohort study (n=1145) revealed a 98.4 % consistency between plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA)-based MSI detection and its tissue-based counterpart, emphasizing the feasibility of blood-sample MSI detection for dependable tumor diagnosis and treatment [91].

Continued exploration of ctDNA underscores its value as a tumor immunotherapy biomarker, given its quick, non-invasive obtainability and capacity to reflect intricate tumor heterogeneity with high specificity. CtDNA aids in predicting patient responses to immunotherapy and distinguishing between responders and non-responders, guiding clinical therapy selection. CtDNA’s potential shines in disease monitoring, indicating when regimen adjustments are warranted, and is particularly beneficial in tracking areas challenging for conventional imaging, like brain and bone metastases. Summarily, the integration of ctDNA into tumor immunotherapy is undeniable, with its biomarker role set to expand, anticipating more applications and research breakthroughs ahead.

Conclusions

In summary, ctDNA holds significant promise for revolutionizing cancer clinical practice, particularly in the context of solid tumor therapy. However, its full potential is hampered by several technical challenges, including its low concentration and dispersion relative to other DNA molecules in the body. These challenges underscore the need for improved technical sensitivity, specificity, as well as sample collection and preprocessing methods. Looking ahead, future research efforts should focus on advancing ctDNA technologies and methodologies, establishing robust standards for testing and analysis, and validating its practical application on a larger clinical trial. This is especially pertinent in areas like MRD testing and immunotherapy research, where the potential value of ctDNA warrants comprehensive exploration. Ultimately, overcoming these challenges and harnessing the potential of ctDNA will be pivotal in enhancing cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Funding source: Educational funding of Liaoning Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. LJKMZ20221135

Funding source: Shenyang Science and technology project funding

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. 22-321-33-06

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: HQ, CL and KL were major contributors in writing the manuscript. HT and SL collected the related references and took the charge of manuscript reviewing and editing. LR and HT critically revises the manuscript. All authors read and approved the finial manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Educational funding of Liaoning Province No. LJKMZ20221135; Shenyang Science and technology project funding No. 22-321-33-06.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Stroun, M, Anker, P, Maurice, P, Lyautey, J, Lederrey, C, Beljanski, M. Neoplastic characteristics of the DNA found in the plasma of cancer patients. Oncology 1989;46:318–22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000226740.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Li, Y, Fan, Z, Meng, Y, Liu, S, Zhan, H. Blood-based DNA methylation signatures in cancer: a systematic review. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Basis Dis 2023;1869:166583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166583.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Moser, T, Kühberger, S, Lazzeri, I, Vlachos, G, Heitzer, E. Bridging biological cfDNA features and machine learning approaches. Trends Genet 2023;39:285–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2023.01.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Thompson, DF, Walker, CK. A descriptive and historical review of bibliometrics with applications to medical sciences. Pharmacotherapy 2015;35:551–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1586.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Ninkov, A, Frank, JR, Maggio, LA. Bibliometrics: methods for studying academic publishing. Perspect Med Educ 2022;11:173–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-021-00695-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Wan, JCM, Massie, C, Garcia-Corbacho, J, Mouliere, F, Brenton, JD, Caldas, C, et al.. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:223–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Tivey, A, Church, M, Rothwell, D, Dive, C, Cook, N. Circulating tumour DNA – looking beyond the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022;19:600–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00660-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004;431:931–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Lin, C, Liu, X, Zheng, B, Ke, R, Tzeng, C-M. Liquid biopsy, ctDNA diagnosis through NGS. Life 2021;11:890. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11090890.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Zhang, L, Parvin, R, Fan, Q, Ye, F. Emerging digital PCR technology in precision medicine. Biosens Bioelectron 2022;211:114344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2022.114344.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. O’Leary, B, Hrebien, S, Beaney, M, Fribbens, C, Garcia-Murillas, I, Jiang, J, et al.. Comparison of BEAMing and droplet digital PCR for circulating tumor DNA analysis. Clin Chem 2019;65:1405–13. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2019.305805.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Larribère, L, Martens, UM. Advantages and challenges of using ctDNA NGS to assess the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) in solid tumors. Cancers 2021;13:5698. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13225698.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Nikanjam, M, Kato, S, Kurzrock, R. Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01351-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Li, H, Jing, C, Wu, J, Ni, J, Sha, H, Xu, X, et al.. Circulating tumor DNA detection: a potential tool for colorectal cancer management. Oncol Lett 2019;17:1409–16. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.9794.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Vessies, DCL, Greuter, MJE, van Rooijen, KL, Linders, TC, Lanfermeijer, M, Ramkisoensing, KL, et al.. Performance of four platforms for KRAS mutation detection in plasma cell-free DNA: ddPCR, Idylla, COBAS z480 and BEAMing. Sci Rep 2020;10:8122. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64822-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Huang, C, Hu, S, Zhang, X, Cui, H, Wu, L, Yang, N, et al.. Sensitive and selective ctDNA detection based on functionalized black phosphorus nanosheets. Biosens Bioelectron 2020;165:112384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2020.112384.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Bahado-Singh, R, Vlachos, KT, Aydas, B, Gordevicius, J, Radhakrishna, U, Vishweswaraiah, S. Precision oncology: artificial intelligence and DNA methylation analysis of circulating cell-free DNA for lung cancer detection. Front Oncol 2022;12:790645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.790645.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Dang, DK, Park, BH. Circulating tumor DNA: current challenges for clinical utility. J Clin Invest 2022;132:e154941. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci154941.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Hasenleithner, SO, Speicher, MR. A clinician’s handbook for using ctDNA throughout the patient journey. Mol Cancer 2022;21:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01551-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Page, K, Martinson, LJ, Hastings, RK, Fernandez-Garcia, D, Gleason, KLT, Gray, MC, et al.. Prevalence of ctDNA in early screen-detected breast cancers using highly sensitive and specific dual molecular barcoded personalised mutation assays. Ann Oncol 2021;32:1057–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.018.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Mo, S, Dai, W, Wang, H, Lan, X, Ma, C, Su, Z, et al.. Early detection and prognosis prediction for colorectal cancer by circulating tumour DNA methylation haplotypes: a multicentre cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2023;55:101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101717.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Liu, X, Liu, L, Ji, Y, Li, C, Wei, T, Yang, X, et al.. Enrichment of short mutant cell-free DNA fragments enhanced detection of pancreatic cancer. EBioMedicine 2019;41:345–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Joosse, SA, Pantel, K. Detection of hypomethylation in long-ctDNA. Clin Chem 2022;68:1115–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac108.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Wu, H, Guo, S, Liu, X, Li, Y, Su, Z, He, Q, et al.. Noninvasive detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma using the methylation signature of circulating tumour DNA. BMC Med 2022;20:458. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02647-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Liang, W, Zhao, Y, Huang, W, Gao, Y, Xu, W, Tao, J, et al.. Non-invasive diagnosis of early-stage lung cancer using high-throughput targeted DNA methylation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Theranostics 2019;9:2056–70. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.28119.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Liang, N, Li, B, Jia, Z, Wang, C, Wu, P, Zheng, T, et al.. Ultrasensitive detection of circulating tumour DNA via deep methylation sequencing aided by machine learning. Nat Biomed Eng 2021;5:586–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00746-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Pantel, K, Alix-Panabières, C. Liquid biopsy and minimal residual disease – latest advances and implications for cure. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:409–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-019-0187-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Cirillo, M, Craig, AFM, Borchmann, S, Kurtz, DM. Liquid biopsy in lymphoma: molecular methods and clinical applications. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;91:102106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102106.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Tie, J, Cohen, JD, Lahouel, K, Lo, SN, Wang, Y, Kosmider, S, et al.. Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:2261–72. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2200075.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Kasi, PM. Tumor-informed versus plasma-only liquid biopsy assay in a patient with multiple primary malignancies. JCO Precis Oncol 2022;6:e2100298. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.21.00298.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Chan, HT, Nagayama, S, Otaki, M, Chin, YM, Fukunaga, Y, Ueno, M, et al.. Tumor-informed or tumor-agnostic circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for risk of recurrence in resected colorectal cancer patients. Front Oncol 2022;12:1055968. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1055968.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Yukami, H, Nakamura, Y, Watanabe, J, Kotaka, M, Yamazaki, K, Hirata, K, et al.. Minimal residual disease by circulating tumor DNA analysis for colorectal cancer patients receiving radical surgery: an initial report from CIRCULATE-Japan. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3608. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.3608.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Cao, D, Wang, F-L, Li, C, Zhang, R-X, Wu, X-J, Li, L, et al.. Patient-specific tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis for molecular residual disease (MRD) detection in surgical patients with stage I-IV colorectal cancer (CRC). J Clin Oncol 2023;41(4 Suppl):213. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2023.41.4_suppl.213.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Santonja, A, Cooper, WN, Eldridge, MD, Edwards, PAW, Morris, JA, Edwards, AR, et al.. Comparison of tumor-informed and tumor-naïve sequencing assays for ctDNA detection in breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2023;15:e16505. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202216505.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Zhang, J-T, Liu, S-Y, Gao, W, Liu, S-YM, Yan, H-H, Ji, L, et al.. Longitudinal undetectable molecular residual disease defines potentially cured population in localized non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov 2022;12:1690–701. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-21-1486.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Filis, P, Kyrochristos, I, Korakaki, E, Baltagiannis, EG, Thanos, D, Roukos, DH. Longitudinal ctDNA profiling in precision oncology and immunο-oncology. Drug Discov Today 2023;28:103540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103540.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Vendramin, R, Litchfield, K, Swanton, C. Cancer evolution: Darwin and beyond. EMBO J 2021;40:e108389. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2021108389.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Gatenby, RA, Brown, JS. Integrating evolutionary dynamics into cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17:675–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0411-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Stanková, K, Brown, JS, Dalton, WS, Gatenby, RA. Optimizing cancer treatment using game theory: a review. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3395.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Dong, S, Wang, Z, Zhou, Q, Yang, L, Zhang, J, Chen, Y, et al.. P49.01 drug holiday based on minimal residual disease status after local therapy following EGFR-TKI treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:S1113–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.529.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Zhong, R, Gao, R, Fu, W, Li, C, Huo, Z, Gao, Y, et al.. Accuracy of minimal residual disease detection by circulating tumor DNA profiling in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2023;21:180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02849-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Duffy, MJ, Crown, J. Circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for monitoring patients with solid cancers: comparison with standard protein biomarkers. Clin Chem 2022;68:1381–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac121.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Li, Y, Mo, S, Zhang, L, Ma, X, Hu, X, Huang, D, et al.. Postoperative circulating tumor DNA combined with consensus molecular subtypes can better predict outcomes in stage III colon cancers: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer 2022;169:198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2022.04.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Connolly, ID, Li, Y, Gephart, MH, Nagpal, S. The “liquid biopsy”: the role of circulating DNA and RNA in central nervous system tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2016;16:25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-016-0629-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Li, M, Chen, J, Zhang, B, Yu, J, Wang, N, Li, D, et al.. Dynamic monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor DNA to identify unique genetic profiles of brain metastatic tumors and better predict intracranial tumor responses in non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases: a prospective cohort study (GASTO 1028). BMC Med 2022;20:398. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02595-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Leighl, NB, Karaseva, N, Nakagawa, K, Cho, B-C, Gray, JE, Hovey, T, et al.. Patient-reported outcomes from FLAURA: osimertinib versus erlotinib or gefitinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2020;125:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Hofman, P. Detecting resistance to therapeutic ALK inhibitors in tumor tissue and liquid biopsy markers: an update to a clinical routine practice. Cells 2021;10:168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010168.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. McCoach, CE, Blakely, CM, Banks, KC, Levy, B, Chue, BM, Raymond, VM, et al.. Clinical utility of cell-free DNA for the detection of ALK fusions and genomic mechanisms of ALK inhibitor resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2758–70. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-2588.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Shaw, AT, Solomon, BJ, Besse, B, Bauer, TM, Lin, C-C, Soo, RA, et al.. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1370–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.18.02236.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Lin, JJ, Shaw, AT. Recent advances in targeting ROS1 in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:1611–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.08.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Dagogo-Jack, I, Rooney, M, Nagy, RJ, Lin, JJ, Chin, E, Ferris, LA, et al.. Molecular analysis of plasma from patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:816–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Tan, L, Tran, B, Tie, J, Markman, B, Ananda, S, Tebbutt, NC, et al.. A phase Ib/II trial of combined BRAF and EGFR inhibition in BRAF V600E positive metastatic colorectal cancer and other cancers: the EVICT (erlotinib and vemurafenib in combination trial) study. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:1017–30. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-3094.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Xu, J-M, Liu, X-J, Ge, F-J, Lin, L, Wang, Y, Sharma, MR, et al.. KRAS mutations in tumor tissue and plasma by different assays predict survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2014;33:104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-014-0104-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Nakamura, Y, Okamoto, W, Kato, T, Esaki, T, Kato, K, Komatsu, Y, et al.. Circulating tumor DNA-guided treatment with pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2021;27:1899–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01553-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Mack, PC, Miao, J, Redman, MW, Moon, J, Goldberg, SB, Herbst, RS, et al.. Circulating tumor DNA kinetics predict progression-free and overall survival in EGFR TKI-treated patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC (SWOG S1403). Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:3752–60. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-0741.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Mok, TS, Wu, Y-L, Ahn, M-J, Garassino, MC, Kim, HR, Ramalingam, SS, et al.. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:629–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1612674.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Yang, JC-H, Ahn, M-J, Kim, D-W, Ramalingam, SS, Sequist, LV, Su, W-C, et al.. Osimertinib in pretreated T790M-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: AURA study phase II extension component. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1288–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.70.3223.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Goss, G, Tsai, C-M, Shepherd, FA, Bazhenova, L, Lee, JS, Chang, G-C, et al.. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1643–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30508-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Soria, J-C, Ohe, Y, Vansteenkiste, J, Reungwetwattana, T, Chewaskulyong, B, Lee, KH, et al.. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:113–25. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1713137.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Fukuoka, M, Wu, Y-L, Thongprasert, S, Sunpaweravong, P, Leong, S-S, Sriuranpong, V, et al.. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2866–74. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.33.4235.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Wu, YL, Zhou, C, Liam, CK, Wu, G, Liu, X, Zhong, Z, et al.. First-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: analyses from the phase III, randomized, open-label, ENSURE study. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1883–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv270.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Chen, G, Feng, J, Zhou, C, Wu, YL, Liu, XQ, Wang, C, et al.. Quality of life (QoL) analyses from OPTIMAL (CTONG-0802), a phase III, randomised, open-label study of first-line erlotinib versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 2013;24:1615–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Hong, S, Gao, F, Fu, S, Wang, Y, Fang, W, Huang, Y, et al.. Concomitant genetic alterations with response to treatment and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:739–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0049.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Wang, Z, Cheng, Y, An, T, Gao, H, Wang, K, Zhou, Q, et al.. Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma circulating tumour DNA as a selection criterion for first-line gefitinib treatment in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma (BENEFIT): a phase 2, single-arm, multicentre clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:681–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30264-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Ye, L-F, Huang, Z-Y, Chen, X-X, Chen, Z-G, Wu, S-X, Ren, C, et al.. Monitoring tumour resistance to the BRAF inhibitor combination regimen in colorectal cancer patients via circulating tumour DNA. Drug Resist Updates 2022;65:100883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2022.100883.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Martínez-Sáez, O, Chic, N, Pascual, T, Adamo, B, Vidal, M, González-Farré, B, et al.. Frequency and spectrum of PIK3CA somatic mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2020;22:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01284-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Poole, JC, Wu, S-F, Lu, TT, Vibat, CRT, Pham, A, Samuelsz, E, et al.. Analytical validation of the Target Selector ctDNA platform featuring single copy detection sensitivity for clinically actionable EGFR, BRAF, and KRAS mutations. PLoS One 2019;14:e0223112. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223112.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

68. Kwon, M, Ku, BM, Olsen, S, Park, S, Lefterova, M, Odegaard, J, et al.. Longitudinal monitoring by next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in ALK rearranged NSCLC patients treated with ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Med 2022;11:2944–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4663.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Ou, S-HI, Young, L, Schrock, AB, Johnson, A, Klempner, SJ, Zhu, VW, et al.. Emergence of preexisting MET Y1230C mutation as a resistance mechanism to crizotinib in NSCLC with MET Exon 14 skipping. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:137–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.119.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Remon, J, Besse, B, Aix, SP, Callejo, A, Al-Rabi, K, Bernabe, R, et al.. Osimertinib treatment based on plasma T790M monitoring in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): EORTC Lung Cancer Group 1613 APPLE phase II randomized clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2023;34:468–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.02.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Zhang, Q, Luo, J, Wu, S, Si, H, Gao, C, Xu, W, et al.. Prognostic and predictive Impact of circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced cancers treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1842–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-0047.Suche in Google Scholar

72. Ma, F, Zhu, W, Guan, Y, Yang, L, Xia, X, Chen, S, et al.. ctDNA dynamics: a novel indicator to track resistance in metastatic breast cancer treated with anti-HER2 therapy. Oncotarget 2016;7:66020–31. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.11791.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. O’Leary, B. PADA-1 trial: ESR1 mutations in plasma ctDNA guide treatment switching. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023;20:67–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00712-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Zhao, Y, Murciano-Goroff, YR, Xue, JY, Ang, A, Lucas, J, Mai, TT, et al.. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature 2021;599:679–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04065-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Murtaza, M, Dawson, S-J, Tsui, DWY, Gale, D, Forshew, T, Piskorz, AM, et al.. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature 2013;497:108–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Bratman, SV, Yang, SYC, Iafolla, MAJ, Liu, Z, Hansen, AR, Bedard, PL, et al.. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis as a predictive biomarker in solid tumor patients treated with pembrolizumab. Nat Cancer 2020;1:873–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-0096-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Raja, R, Kuziora, M, Brohawn, PZ, Higgs, BW, Gupta, A, Dennis, PA, et al.. Early reduction in ctDNA predicts survival in patients with lung and bladder cancer treated with durvalumab. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:6212–22. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-0386.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Goldberg, SB, Narayan, A, Kole, AJ, Decker, RH, Teysir, J, Carriero, NJ, et al.. Early assessment of lung cancer immunotherapy response via circulating tumor DNA. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1872–80. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-1341.Suche in Google Scholar

79. Anagnostou, V, Forde, PM, White, JR, Niknafs, N, Hruban, C, Naidoo, J, et al.. Dynamics of tumor and immune responses during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 2019;79:1214–25. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-1127.Suche in Google Scholar

80. Váraljai, R, Wistuba-Hamprecht, K, Seremet, T, Diaz, JMS, Nsengimana, J, Sucker, A, et al.. Application of circulating cell-free tumor DNA profiles for therapeutic monitoring and outcome prediction in genetically heterogeneous metastatic melanoma. JCO Precis Oncol 2020;3:PO.18.00229. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.18.00229.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

81. Kansara, M, Bhardwaj, N, Thavaneswaran, S, Xu, C, Lee, JK, Chang, L-B, et al.. Early circulating tumor DNA dynamics as a pan-tumor biomarker for long-term clinical outcome in patients treated with durvalumab and tremelimumab. Mol Oncol 2023;17:298–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.13349.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82. Frelaut, M, du Rusquec, P, de Moura, A, Le Tourneau, C, Borcoman, E. Pseudoprogression and hyperprogression as new forms of response to immunotherapy. BioDrugs 2020;34:463–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00425-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Lee, JH, Long, GV, Menzies, AM, Lo, S, Guminski, A, Whitbourne, K, et al.. Association between circulating tumor DNA and pseudoprogression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:717–21. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5332.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Nabet, BY, Esfahani, MS, Moding, EJ, Hamilton, EG, Chabon, JJ, Rizvi, H, et al.. Noninvasive early identification of therapeutic benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition. Cell 2020;183:363–76.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85. Sha, D, Jin, Z, Budczies, J, Kluck, K, Stenzinger, A, Sinicrope, FA. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1808–25. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-0522.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

86. Stadler, J-C, Belloum, Y, Deitert, B, Sementsov, M, Heidrich, I, Gebhardt, C, et al.. Current and future clinical applications of ctDNA in immuno-oncology. Cancer Res 2022;82:349–58. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-21-1718.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Parikh, AR, Leshchiner, I, Elagina, L, Goyal, L, Levovitz, C, Siravegna, G, et al.. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat Med 2019;25:1415–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0561-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

88. Marusyk, A, Janiszewska, M, Polyak, K. Intratumor heterogeneity: the Rosetta Stone of therapy resistance. Cancer Cell 2020;37:471–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89. Gandara, DR, Paul, SM, Kowanetz, M, Schleifman, E, Zou, W, Li, Y, et al.. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a predictor of clinical benefit in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. Nat Med 2018;24:1441–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0134-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

90. Rizvi, NA, Cho, BC, Reinmuth, N, Lee, KH, Luft, A, Ahn, M-J, et al.. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab vs standard chemotherapy in first-line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: the MYSTIC phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:661–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0237.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Willis, J, Lefterova, MI, Artyomenko, A, Kasi, PM, Nakamura, Y, Mody, K, et al.. Validation of microsatellite instability detection using a comprehensive plasma-based genotyping panel. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:7035–45. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-1324.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-1157).

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

- Supplementary Material

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Circulating tumor DNA measurement: a new pillar of medical oncology?

- Reviews

- Circulating tumor DNA: current implementation issues and future challenges for clinical utility

- Circulating tumor DNA methylation: a promising clinical tool for cancer diagnosis and management

- Opinion Papers

- The final part of the CRESS trilogy – how to evaluate the quality of stability studies

- The impact of physiological variations on personalized reference intervals and decision limits: an in-depth analysis

- Computational pathology: an evolving concept

- Perspectives

- Dynamic mirroring: unveiling the role of digital twins, artificial intelligence and synthetic data for personalized medicine in laboratory medicine

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Macroprolactin in mothers and their babies: what is its origin?

- The influence of undetected hemolysis on POCT potassium results in the emergency department

- Quality control in the Netherlands; todays practices and starting points for guidance and future research

- QC Constellation: a cutting-edge solution for risk and patient-based quality control in clinical laboratories

- OILVEQ: an Italian external quality control scheme for cannabinoids analysis in galenic preparations of cannabis oil

- Using Bland-Altman plot-based harmonization algorithm to optimize the harmonization for immunoassays

- Comparison of a two-step Tempus600 hub solution single-tube vs. container-based, one-step pneumatic transport system

- Evaluating the HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay: a powerful approach to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma

- Insight into the status of plasma renin and aldosterone measurement: findings from 526 clinical laboratories in China

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Reference values for plasma and urine trace elements in a Swiss population-based cohort

- Stimulating thyrotropin receptor antibodies in early pregnancy

- Within- and between-subject biological variation estimates for the enumeration of lymphocyte deep immunophenotyping and monocyte subsets

- Diurnal and day-to-day biological variation of salivary cortisol and cortisone

- Web-accessible critical limits and critical values for urgent clinician notification

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Thyroglobulin measurement is the most powerful outcome predictor in differentiated thyroid cancer: a decision tree analysis in a European multicenter series

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Interaction of heparin with human cardiac troponin complex and its influence on the immunodetection of troponins in human blood samples

- Diagnostic performance of a point of care high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay and single measurement evaluation to rule out and rule in acute coronary syndrome

- Corrigendum

- Reference intervals of 24 trace elements in blood, plasma and erythrocytes for the Slovenian adult population

- Letters to the Editor

- Disturbances of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate homeostasis: incidence, probable causes, and outcome

- Validation of the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF)-test in heparinized and EDTA plasma for use in reflex testing algorithms for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

- Detection of urinary foam cells diagnosing the XGP with thrombopenia preoperatively: a case report

- Methemoglobinemia after sodium nitrite poisoning: what blood gas analysis tells us (and what it might not)

- Novel thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) variant identified in Malay individuals

- Congress Abstracts