Abstract

Objectives

This study evaluates the HYDRASHIFT assay’s effectiveness in mitigating daratumumab interference on serum protein tests during multiple myeloma (MM) treatment, aiming to ensure an accurate assessment of treatment response.

Methods

We analyzed 113 serum samples from 68 MM patients undergoing daratumumab treatment, employing both standard IF and the HYDRASHIFT assay. The assay’s precision was determined through intra-day and inter-day variability assessments, while its specificity was verified using serum samples devoid of daratumumab. Comparative analysis of IF results, before and after the application of the HYDRASHIFT assay, facilitated the categorization of treatment responses in alignment with the International Myeloma Working Group’s response criteria.

Results

The precision underscored the assay’s consistent repeatability and reproducibility, successfully eliminating interference of daratumumab-induced Gκ bands. Specificity assessments demonstrated the assay’s capability to distinguish daratumumab from both isatuximab and naturally occurring M-proteins. Of the analyzed cases, 91 exhibited successful migration of daratumumab-induced Gκ bands, thereby enhancing the accuracy of treatment response classification. The remaining 22 cases did not show a visible migration complex, likely due to the low concentration of daratumumab in the serum. These findings underscore the assay’s critical role in distinguishing daratumumab from endogenous M-protein, particularly in samples with a single Gκ band on standard IF, where daratumumab and endogenous M-protein had co-migrated.

Conclusions

The HYDRASHIFT assay demonstrates high precision, specificity, and utility in the accurate monitoring of treatment responses in MM patients receiving daratumumab. This assay represents a significant advancement in overcoming the diagnostic challenges posed by daratumumab interference.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable hematologic malignancy that requires long-term therapy and monitoring. Most MM patients undergo several cycles of remission and relapse, necessitating multiple lines of combination therapies, including proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (t-mAbs), among others [1]. Currently, the most widely used t-mAb is daratumumab, a human immunoglobulin IgG1κ monoclonal antibody (mAb) targeting the CD38 surface protein on myeloma cells [2]. Daratumumab has proven to be effective in treating both newly diagnosed [3], [4], [5], [6] and relapsed/refractory MM [7, 8]. However, as a human IgGκ immunoglobulin, daratumumab is detected on serum electrophoresis (EP) and immunofixation (IF), potentially causing false-positive interference [9, 10]. Misinterpretation of daratumumab as pathologic M-protein can lead to misidentification of a patient’s treatment response, based on the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) response criteria, and affect clinical decisions. Therefore, laboratory tests to distinguish daratumumab from endogenous M-protein are absolutely necessary.

Sebia’s HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay has successfully discriminated between daratumumab and endogenous M-protein on gel IF [11]. This assay employs anti-daratumumab antiserum to bind to the daratumumab component and shift it outside the gamma globulin region, revealing the true presence of the patient’s M-protein. Although it is the only commercially available, FDA-approved, daratumumab-specific IF reflex assay, its performance has been evaluated in only a few studies with a limited number of samples [11], [12], [13]. In this study, we evaluated the performance of the HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay in a relatively large number of MM patient samples and established an indication of the assay’s effectiveness based on our experience.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Remnant serum samples from MM patients treated with daratumumab were collected from July 2022 to July 2023 at Samsung Medical Center, a tertiary care hospital in Seoul, South Korea. In total, 113 serum samples from 68 MM patients, submitted for routine monoclonal protein assessment, were included in this study. Each sample had a minimal volume of 300 μL. The samples were stored at −70 °C until analyzed. Clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, diagnosis, isotype of endogenous M-protein, history of daratumumab infusion, and concurrent chemotherapy, were gathered through chart reviews (Table 1). Serum and urine EP, urine IF, and bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy studies, conducted on the day of sample submission, were analyzed to determine the disease status of the patients. The Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center approved this study (SMC IRB No. 2023-07-053).

Clinical characteristics of the 68 patients administered with daratumumab.

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 68 |

| No. of measurements | 113 |

| No. of measurements per patient, median (range) | 1 (1–5) |

| Age, years, median (range) | 67 (39–87) |

| Sex | Male: n=43 Female: n=25 |

| Diagnosis | Multiple myeloma: n=64 Multiple myeloma and amyloidosis: n=4 |

| Isotype of endogenous M-protein | Gκ: n=24 Gλ: n=13 Aκ: n=4 Aλ: n=6 Mκ: n=1 Mλ: n=0 Light chain only, κ: n=5 Light chain only, λ: n=15 |

| Treatment regimen | Daratumumab monotherapy: n=25 Daratumumab + bortezomib + steroid: n=4 Daratumumab + lenalidomide + steroid: n=5 Daratumumab + pomalidomide + steroid: n=5 Daratumumab + iberdomide + steroid: n=9 Daratumumab + talquetamab + steroid: n=2 Daratumumab + teclistamab: n=6 Daratumumab + elranatamab: n=1 Daratumumab + bortezomib + lenalidomide + steroid: n=8 Daratumumab + bortezomib + thalidomide + steroid: n=2 Daratumumab + talquetamab + pomalidomide + steroid: n=1 |

| Time interval between the last infusion and sample collection, day, median (range) | 14 (6–126) |

Gel IF by Hydrasys 2 scan focusing and HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay

Gel IF on selected samples was performed using the Hydrasys 2 scan focusing system (Sebia, Lisses, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions and employing the Hydragel IF 2/4 gel (Sebia). The process included automated steps such as sample application, electrophoretic migration, incubation with fixative solution and antisera, gel drying, staining with acid violet, destaining, and scanning. Manual procedures involved handling of samples and gels, application of fixative and antisera, and instrument setup. The HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay (HYDRASHIFT assay) was conducted by applying anti-daratumumab antiserum to a specific site on the anti-dara applicator, aligning with the IgG and kappa lanes of the gel. This resulted in the formation of a daratumumab-anti-daratumumab complex, which migrated to the alpha-1 region of the gel. For each patient sample, results were recorded both before and after the HYDRASHIFT assay – termed pre-HYDRASHIFT IF and post-HYDRASHIFT IF, respectively – and were analyzed for the presence of monoclonal bands through visual inspection.

Gel IF interpretation

The gel IF results were interpreted by three qualified reviewers (two attending faculties [S-M.K and H-D.P] and one clinical pathology resident [H-W.L]). A consensus call was necessary to assign the sample to a specific isotype category. At the time of interpretation, other information such as the results of serum EP, urine EP, urine IF and BM study, or the patients’ clinical data were not available to the reviewers.

Performance evaluation of HYDRASHIFT assay

The precision and specificity of the HYDRASHIFT assay were assessed, along with a comparison analysis between pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF results.

Precision

Intra-day and inter-day variability were evaluated using a quality control (QC) sample and a patient sample. The QC sample, provided by Sebia, was prepared by spiking daratumumab into drug-free human serum. The patient sample contained both daratumumab and endogenous Gλ paraprotein, reflective of the patient’s treatment history and clinical status. Intra-day variability was assessed over 10 runs in a single day, while inter-day variability was assessed over 2 runs per day across 5 days, with an acceptance criterion of 100 % consistency among runs.

Specificity

The specificity assessment utilized four daratumumab-free serum samples: one from a patient treated with isatuximab and three from newly diagnosed MM patients with endogenous paraprotein isotypes of Gκ, Gλ, and Aκ. Each sample underwent testing twice, with and without the HYDRASHIFT assay applied. An identical gel IF result and the absence of a migration complex (daratumumab-anti daratumumab antibody complex) indicated acceptable specificity.

Comparison analysis

Results from pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF were interpreted and documented, then compared alongside patients’ disease statuses. Disease status was determined using serum EP, urine EP, post-HYDRASHIFT IF, urine IF, and BM study results, in accordance with standard IMWG response criteria [14]. A complete response (CR) was identified by negative results in all of these tests, while persistent disease (P) was indicated by at least one positive result.

Results

Interpretation of every gel IF conducted in this study reached a consensus by the three reviewers.

Precision and specificity

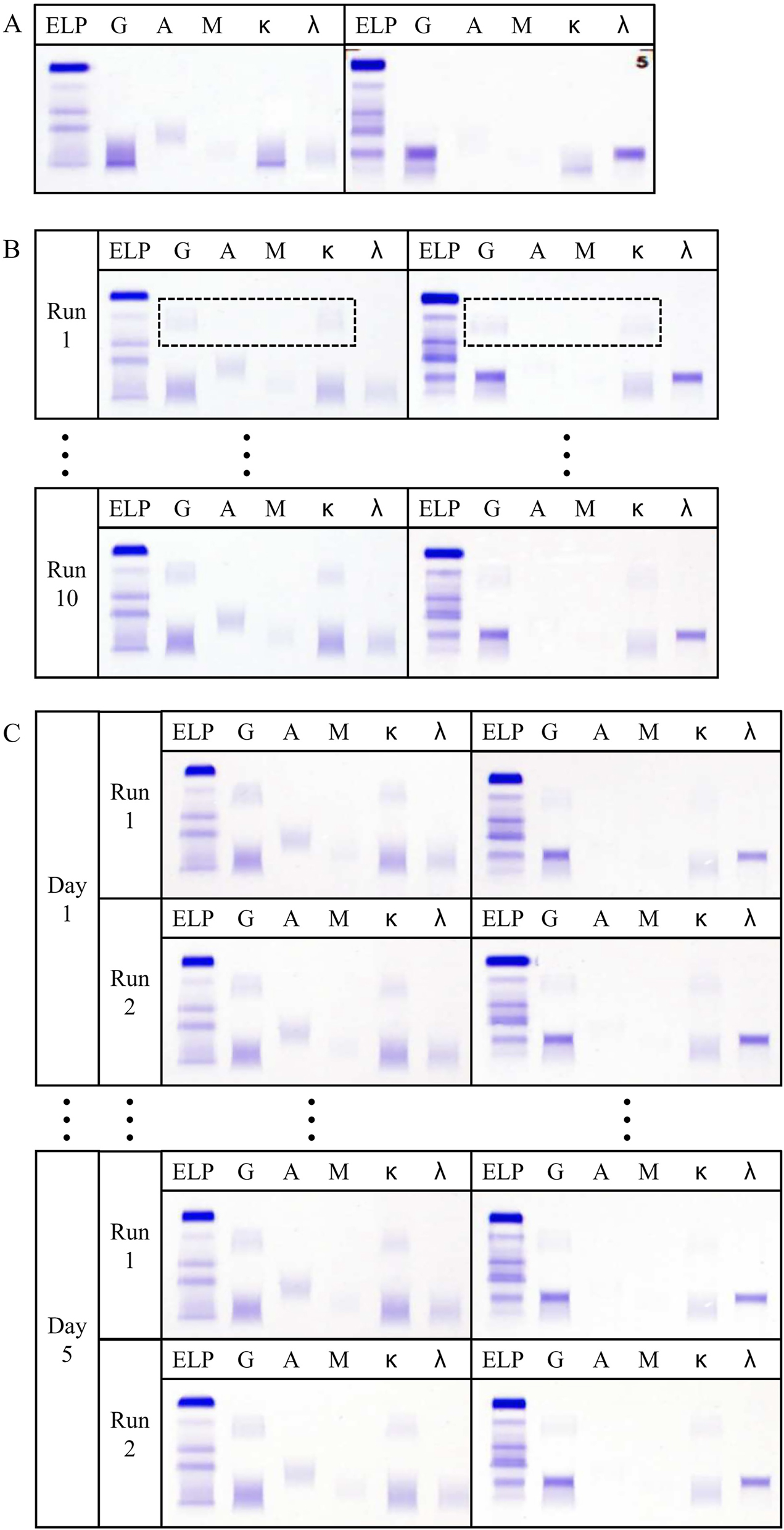

Before the implementation of the HYDRASHIFT assay, the daratumumab-induced Gκ band was observable in standard gel IF for both QC and patient samples, as shown in Figure 1A. The assay’s intra-day and inter-day variability were deemed satisfactory, as evidenced by the consistent appearance of the migration complex for both QC and patient samples following the application of the HYDRASHIFT assay, as illustrated in Figure 1B and C. This consistency indicates that the HYDRASHIFT assay effectively neutralizes the interference caused by daratumumab in the immunofixation process, thereby ensuring reliable and accurate detection of monoclonal proteins in the evaluated samples.

Precision of HYDRASHIFT assay. (A) Standard gel IF of QC (Left) and the patient sample (Right). (B) Intra-day variability of HYDRASHIFT assay on QC (Left) and the patient sample (Right). Box in dotted line represents the migration complex. (C) Inter-day variability of HYDRASHIFT assay on QC (Left) and the patient sample (Right).

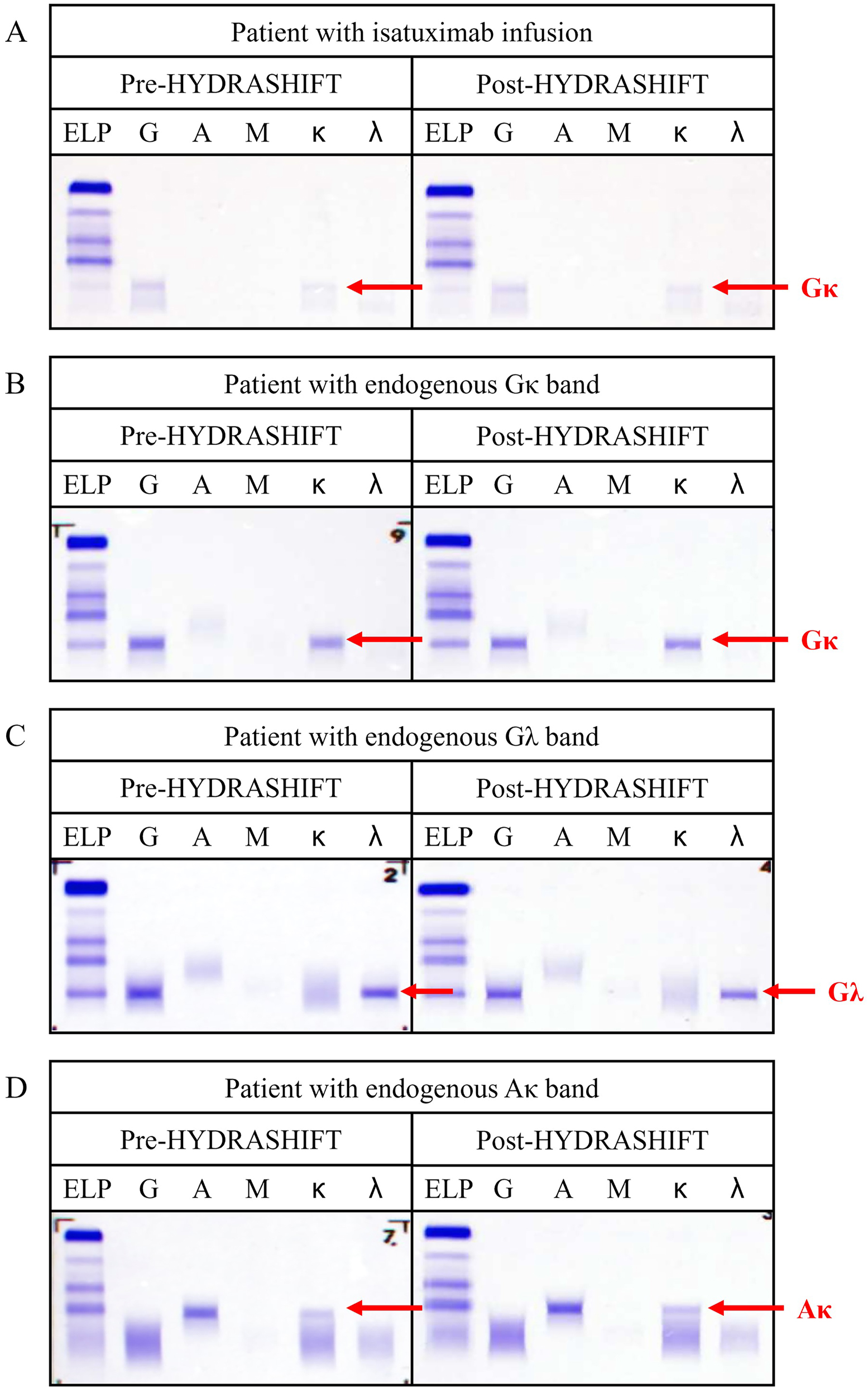

The specificity of the assay was confirmed to be acceptable, as the pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF results were identical across all four patient samples, with no migration complex observed (Figure 2). The HYDRASHIFT assay did not interfere with isatuximab or the patients’ endogenous M-protein, demonstrating excellent specificity.

Specificity of HYDRASHIFT assay. (A) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of patient with isatuximab infusion. (B) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of patient with endogenous Gκ band. (C) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of patient with endogenous Gλ band. (D) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of patient with endogenous Aκ band.

After the application of the HYDRASHIFT assay, every daratumumab component migrated to the anodal end without leaving any trace of positive interference (Figure 1), while patients’ endogenous bands remained on their initial position (Figure 2). These results suggest the perfect separation capacity of the HYDRASHIFT assay, enabling full discrimination of daratumumab from patients’ endogenous M-protein.

Comparison analysis

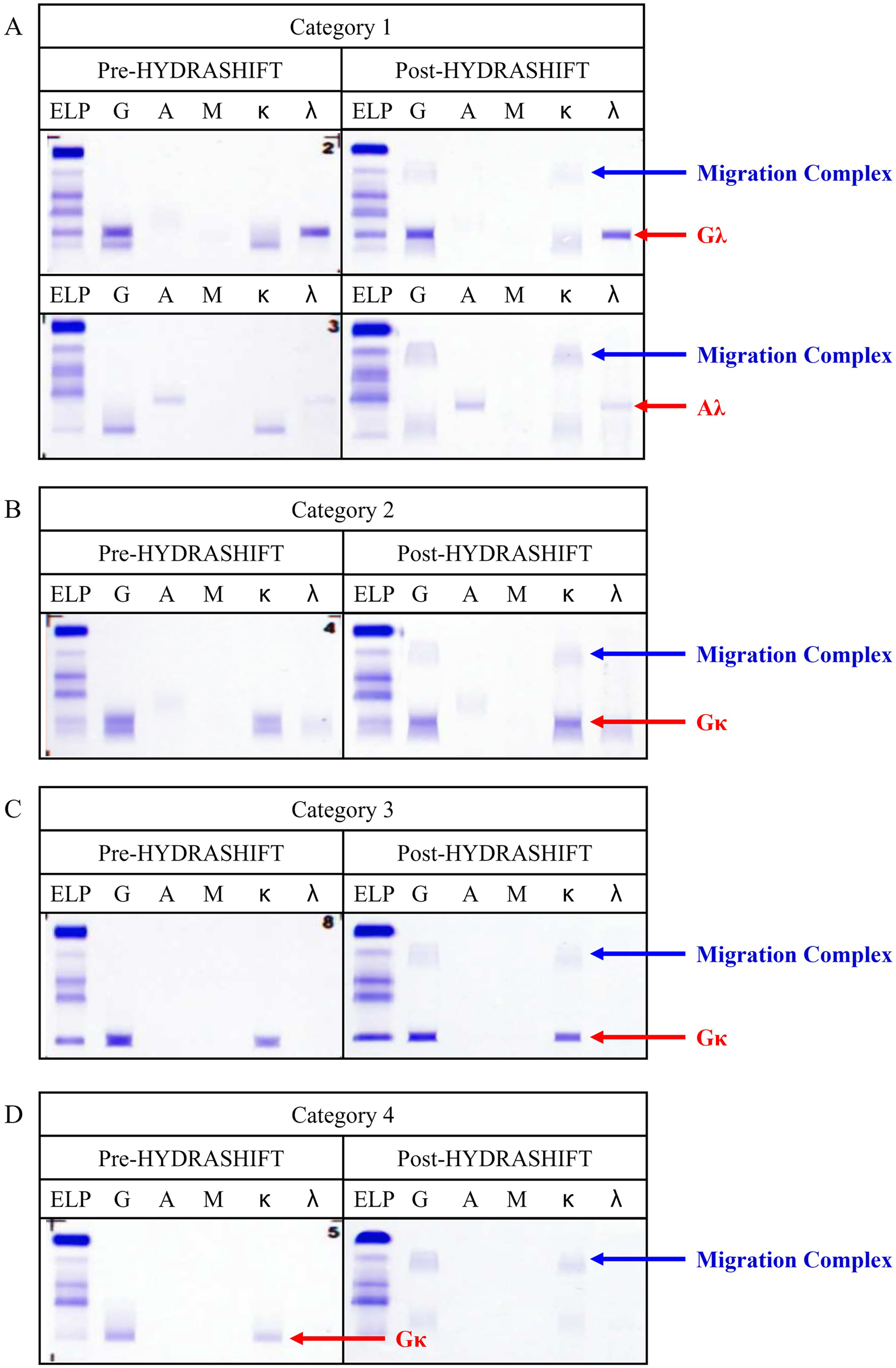

A total of 113 serum samples from 68 multiple myeloma patients undergoing daratumumab therapy were analyzed. The pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF results were categorized into seven groups (Table 2). A migration complex was observed in categories 1–4 (n=91), indicating the successful elimination of the daratumumab-induced Gκ band by the HYDRASHIFT assay. Categories 1–3 showed persistence of endogenous M-protein, while category 4 indicated a complete response. No migration complex was observed in categories 5–7 (n=22), indicating the absence of a daratumumab-induced Gκ band. Categories 5 and 6 showed persistence of endogenous M-protein, whereas category 7 indicated a complete response. The time interval between the last daratumumab infusion and sample collection significantly differed between groups with (categories 1–4) and without (categories 5–7) a migration complex, with median intervals of 14 and 28 days, respectively (p<0.001) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Comparison and categorization of the pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF results.

| Category no. | Presence of migration complex | Pre-HYDRASHIFT IF result | Post-HYDRASHIFT IF result | Disease status | No. of samples | BM study result | Interpretation of the monoclonal components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Yes (n=91) | Gκ + Non-Gκ | Non-Gκa | P | 21a | ND | Daratumumab + endogenous M-protein (non-Gκ) |

| 2 | Gκ + Gκ | Gκ | P | 12 | ND | Daratumumab + endogenous M-protein (Gκ) | |

| 3 | Gκ | Gκ | P | 16 | ND | Daratumumab + endogenous M-protein (Gκ) | |

| 4b | Gκ | No band | CR | 42 | CR (3b) | Daratumumab | |

| 5c | No (n=22) | Non-Gκ | Non-Gκc | P | 3c | ND | Endogenous M-protein (non-Gκ) |

| 6d | Gκ | Gκ | P | 17 | P (1d) | Endogenous M-protein (Gκ) | |

| 7 | No band | No band | CR | 2 | ND | Absent |

-

Non-Gκ refers to the isotype of the monoclonal band other than Gκ. aIsotypes of category 1 consist of 14 Gλ, four λ, two Aλ, and one Aκ + λ. bThree samples in category 4 revealed complete remission on BM study, consistent with the post-HYDRASHIFT IF result. cIsotypes of category 5 consist of one Aκ + κ, one κ, and one λ. dOne sample in category 6 revealed disease persistence on BM study, consistent with the post-HYDRASHIFT IF result. CR, complete response; IF, immunofixation; ND, not done; P, persistence.

The IF patterns of patients treated with daratumumab and exhibiting a migration complex were classified into four categories (1–4), based on the isotype of endogenous M-protein and disease progression. Representative cases for each category are illustrated in Figure 3. An oligoclonal band pattern on pre-HYDRASHIFT IF (Figure 3A and B) suggested the coexistence of daratumumab and endogenous M-protein. A single Gκ band pattern on pre-HYDRASHIFT IF indicated two possibilities: formation by co-migration of daratumumab and endogenous M-protein (Figure 3C) or solely due to daratumumab (Figure 3D).

Representative cases with migration complex on the comparison analysis. Daratumumab and patients’ endogenous M-protein were fully discriminated. (A) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of category 1 (Gκ + Non-Gκ → Non-Gκ). (B) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of category 2 (Gκ + Gκ → Gκ). (C) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of category 3 (Gκ → Gκ). (D) Pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF of category 4 (Gκ → No band).

Among 36 patients tested two or more times with the HYDRASHIFT assay, three experienced a change in their disease status, as detailed in Table 3. Patients A and C exhibited relapse of multiple myeloma; the 2nd follow-up (f/u) for patient A showed positive findings on post-HYDRASHIFT IF and urine IF, indicating relapse. Similarly, the 2nd f/u for patient C showed positive results on post-HYDRASHIFT IF and serum EP, suggesting a relapse. Patient B demonstrated complete remission at the 2nd f/u, as evidenced by negative results on post-HYDRASHIFT IF and other tests.

Serial follow-up of pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF results on three patients with change on disease status.

| Patient | Follow-up | Sample collection date | Chemotherapy cycle | Pre-HYDRASHIFT IF result | Post-HYDRASHIFT IF result | Serum EP | Urine EP | Urine IF | BM study | Disease status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | #1 | 2022.07.21 | C8D1 | No band | No band | N | ND | N | ND | CR |

| #2 | 2023.01.31 | C15D1 | Gκ | Gκ | N | ND | Gκ | ND | P | |

| B | #1 | 2022.08.30 | C8D1 | Gκ + Gκ | Gκ | N | N | N | ND | P |

| #2 | 2022.11.22 | C11D1 | Gκ | No band | N | N | N | ND | CR | |

| #3 | 2023.02.14 | C14D1 | Gκ | No band | N | N | N | ND | CR | |

| C | #1 | 2022.11.29 | C20D1 | Gκ | No band | N | N | N | ND | CR |

| #2 | 2023.03.21 | C24D1 | Gκ + Gκ | Gκ | M (<0.1) | N | N | ND | P | |

| #3 | 2023.04.18 | C25D1 | Gκ + Gκ | Gκ | M (0.45) | N | N | ND | P | |

| #4 | 2023.05.04 | C25D1 | Gκ + Gκ | Gκ | M (1.55) | N | Gκ | ND | P | |

| #5 | 2023.06.02 | C25D1 | Gκ | Gκ | M (0.46) | N | Gκ | ND | P |

-

The number in the parenthesis indicates the amount of M-protein in g/dL unit. CR, complete response; M, monoclonal peak; N, no peak or band; ND, not done; P, persistence.

Discussion

This study represents the largest collection of patient samples among the performance evaluation studies for the HYDRASHIFT assay [11], [12], [13], comprising a total of 113 serum samples from 68 daratumumab-treated MM patients for the comparison analysis of pre- and post-HYDRASHIFT IF.

Out of the 113 samples, 22 exhibited no visible migration complex. This absence could be attributed to low serum daratumumab concentrations, falling below the limit of visualization. Caillon et al. demonstrated that migration complexes become difficult to visualize when daratumumab concentration drops below 0.2 g/L [12]. Daratumumab pharmacokinetic data indicate that serum concentrations may dip below 0.2 g/L after reaching steady state [15]. However, the high variability in serum daratumumab concentrations among patients made it impossible to precisely estimate the concentration. Therefore, our analysis concentrated on factors influencing serum daratumumab concentration: the daratumumab infusion cycle, dosage, and sampling timing. Firstly, the number of daratumumab infusion cycles was sufficient to assume a steady state in all samples. Secondly, the daratumumab dosage was consistently set at 16 mg/kg for all patients. Thirdly, the interval between serum sampling and daratumumab infusion was significantly longer in the group without the migration complex (n=22) compared to the group with the migration complex (n=91), as shown in Supplementary Figure 1. We hypothesize that this extended interval led to the relatively lower serum daratumumab concentrations, resulting in the absence of a visible migration complex.

Before the adoption of the HYDRASHIFT assay, interpreting serum EP and IF results in daratumumab-treated patients involved correlating these results with other tests. Historical data, including serum EP/IF, urine EP/IF, free light chain ratio, and even BM studies, were thoroughly reviewed to detect pathologic M-protein presence. Despite these efforts, uncertainty persisted when a single Gκ band was identified in initial serum IF tests, making it difficult to ascertain whether the band represented the patient’s M-protein (category 6), daratumumab (category 4), or the coexistence of both monoclonal antibodies (category 3). Consequently, the HYDRASHIFT assay is required for samples displaying a single Gκ band on initial serum IF, where the patient’s M-protein and daratumumab may have co-migrated due to their similar electrophoretic mobility. In our study, categories 3, 4, and 6 necessitated the use of the HYDRASHIFT assay for accurate treatment response evaluation. Additionally, Kirchhoff et al. reported that the HYDRASHIFT assay is unnecessary for the patients with M-spike of over 0.2 g/dL, the maximum serum concentration of daratumumab, since high M-spike quantitation itself implies the presence of pathologic M-protein and persistent myeloma [16]. A total of 53 samples revealed M-protein of less than 0.2 g/dL on serum EP, consisting of seven samples in category 3, 42 samples in category 4 and four samples in category 6. Hence, 47 % (53/113) of the samples in our study would truly require the HYDRASHIFT assay. On the other hand, when two distinct bands are seen on initial serum IF (categories 1 and 2), distinguishing the patient’s M-protein from daratumumab becomes feasible. Nevertheless, the HYDRASHIFT assay remains beneficial for identifying rare, treatment-related, endogenous oligoclonal bands [11, 17, 18].

The HYDRASHIFT assay proved invaluable in detecting changes in disease status during routine f/u tests. Without it, the disease status determined by initial serum immunofixation (IF) would have led to the misclassification of the 2nd and 3rd f/u of patient B and the 1st f/u of patient C (referenced in Table 3) as persistent disease. However, the application of post-HYDRASHIFT IF revealed the disappearance of the monoclonal Gκ band, indicating disease remission. For patient B, complete remission (CR) was achieved by the 2nd f/u, and as planned, daratumumab monotherapy concluded on cycle 24 without further treatment. For patient C, CR was reached by the 1st f/u, and daratumumab monotherapy concluded on cycle 25 as scheduled. Unfortunately, the 2nd f/u for patient C showed disease relapse, prompting a change in the treatment regimen to a combination of pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone. The utility of the HYDRASHIFT assay was particularly evident in these three instances (2nd and 3rd f/u for patient B, and 1st f/u for patient C), where each case exhibited a single Gκ band on initial serum IF. Cases presenting a single Gκ band are susceptible to misinterpretation, and the HYDRASHIFT assay stands as the only commercially available, FDA-approved method capable of eliminating false-positive IF results, underscoring its importance in accurate disease status evaluation.

The HYDRASHIFT assay offers notable user convenience, as it integrates seamlessly with the existing analyzers (Hydrasys 2 scan focusing) by requiring only the simple addition of an anti-daratumumab reagent, in contrast to the original protocol. We explored the possibility of the HYDRASHIFT assay interfering with other monoclonal antibodies involving the IgG heavy chain or kappa light chain, given that the anti-daratumumab antiserum is applied to the IgG and kappa lanes of the gel. A specificity analysis was carried out, confirming that the HYDRASHIFT assay does not affect isatuximab and patients’ pathologic M-proteins with isotypes of Gκ, Gλ, and Aκ. However, we were unable to test specificity for other isotypes containing IgG or kappa, such as Mκ, due to the absence of specimens. Isotypes Dκ and Eκ were also not tested because of their rare occurrence.

Another limitation of our study is the self-determined study design and acceptance criteria, given the lack of existing guidelines for evaluating the performance of non-binary examinations with three or more categorical results [19]. Only one article provided a comprehensive method for verifying precision, accuracy, and conducting comparison studies for non-binary qualitative examinations [20]. However, applying this verification protocol was impractical due to the complexity of the experiments, the unavailability of QC samples, and the lack of alternative assays capable of mitigating the effect of daratumumab. Additionally, the determination of disease status may have been limited due to the lack of BM studies, considering their pivotal role in diagnosing MM. Only four BM studies were conducted on the exact day of sample submission (Table 2), owing to practical difficulties such as the lengthy interval between follow-up BM studies, whereas other tests – serum and urine EP, urine IF and post-HYDRASHIFT IF – were thoroughly performed on every patient sample. Moreover, the use of other t-mAbs – erlantamab, talquetamab, teclistamab (Table 1) – was neglected in this study, presuming that they would not induce false-positive interference in serum EP or IF tests. The dosage of these other t-mAbs, in moles per patient’s body weight, was less than 15 % of the daratumumab dosage, indicating their negligible impact on interference compared to that of daratumumab. Furthermore, as these t-mAbs have recently gained clinical approval, their effects on immunofixation analysis are unknown, necessitating further evaluation.

The HYDRASHIFT assay stands out as a distinct method that differentiates between patients’ M-protein and daratumumab, yet it faces certain limitations. Specifically, the HYDRASHIFT assay is tailored for daratumumab and does not address interferences caused by other t-mAbs, as illustrated in Figure 2A. This limitation becomes increasingly relevant as new combinations of t-mAbs are introduced in clinical practice. To fully eliminate interferences from t-mAbs, antisera specific to each t-mAb need to be developed. For example, the HYDRASHIFT 2/4 isatuximab assay by Sebia successfully removes isatuximab interference using anti-isatuximab antiserum [21]. Moreover, assays that counteract the interference from both daratumumab and nivolumab have been recently formulated [13]. To bypass the limitations inherent to the IF method, quantitative assays employing mass spectrometry (MS) have been adopted [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. MS-based assays are capable of accurately quantifying M-protein without interference from multiple t-mAbs, owing to the unique mass-to-charge ratio of M-protein compared to that of t-mAbs. From the perspective of detecting minimal residual disease, MS-based assays offer sensitivity and minimal invasiveness, making them a compelling alternative to BM studies [23, 26]. Despite their advantages, MS-based methods have not been broadly adopted for routine monitoring due to challenges such as cost, maintenance, and the need for standardization. Therefore, during the transition from electrophoretic to the forthcoming mass-spectrometric era in M-protein diagnostics, the HYDRASHIFT assay remains an essential tool. Its specificity for daratumumab, while a limitation in the face of emerging t-mAbs, underscores the need for continued development in diagnostic assays to accommodate evolving therapeutic strategies.

Conclusions

As daratumumab continues to gain prominence as a primary therapy for multiple myeloma [27, 28], the demand for the HYDRASHIFT assay is expected to rise. The clinical adoption of this highly precise and specific assay is critical for providing accurate monitoring of treatment responses. Particularly, samples from patients treated with daratumumab that display a single Gκ band on standard gel IF are prime candidates for the HYDRASHIFT assay. This tool addresses a significant challenge in the interpretation of IF results, ensuring that clinicians can differentiate between the therapeutic monoclonal antibody and the patient’s own monoclonal proteins. Thus, the HYDRASHIFT assay plays a vital role in optimizing patient care by enabling more precise assessments of disease status and treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with support from Sebia Korea.

-

Research ethics: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center approved this study (SMC IRB No. 2023-07-053).

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Lee was involved in the analysis of clinical data and experimental results, and in writing the initial draft of the manuscript. Kim assisted with data collection and analysis of the results. Park oversaw the research design, analysis of experimental results, manuscript revision, and overall progress. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Kumar, SK, Callander, NS, Adekola, K, Anderson, LD, Baljevic, M, Baz, R, et al.. Multiple myeloma, version 2.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2023;21:1281–301. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Lokhorst, HM, Plesner, T, Laubach, JP, Nahi, H, Gimsing, P, Hansson, M, et al.. Targeting CD38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1207–19. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1506348.Search in Google Scholar

3. Moreau, P, Attal, M, Hulin, C, Arnulf, B, Belhadj, K, Benboubker, L, et al.. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;394:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31240-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Mateos, MV, Dimopoulos, MA, Cavo, M, Suzuki, K, Jakubowiak, A, Knop, S, et al.. Daratumumab plus bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:518–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1714678.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Facon, T, Kumar, S, Plesner, T, Orlowski, RZ, Moreau, P, Bahlis, N, et al.. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2104–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1817249.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Facon, T, Kumar, SK, Plesner, T, Orlowski, RZ, Moreau, P, Bahlis, N, et al.. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1582–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00466-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Lonial, S, Weiss, BM, Usmani, SZ, Singhal, S, Chari, A, Bahlis, NJ, et al.. Daratumumab monotherapy in patients with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (SIRIUS): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1551–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01120-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Palumbo, A, Chanan-Khan, A, Weisel, K, Nooka, AK, Masszi, T, Beksac, M, et al.. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;375:754–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1606038.Search in Google Scholar

9. McCudden, CR, Jacobs, JFM, Keren, D, Caillon, H, Dejoie, T, Andersen, K. Recognition and management of common, rare, and novel serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation interferences. Clin Biochem 2018;51:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.08.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Murata, K, McCash, SI, Carroll, B, Lesokhin, AM, Hassoun, H, Lendvai, N, et al.. Treatment of multiple myeloma with monoclonal antibodies and the dilemma of false positive M-spikes in peripheral blood. Clin Biochem 2018;51:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.09.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Thoren, KL, Pianko, MJ, Maakaroun, Y, Landgren, CO, Ramanathan, LV. Distinguishing drug from disease by use of the hydrashift 2/4 daratumumab assay. J Appl Lab Med 2019;3:857–63. https://doi.org/10.1373/jalm.2018.026476.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Caillon, H, Irimia, A, Simon, JS, Axel, A, Sasser, K, Scullion, MJ, et al.. Overcoming the interference of daratumumab with immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) using an industry-developed dira test : hydrashift 2/4 daratumumab. Blood 2016;128:2063. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v128.22.2063.2063.Search in Google Scholar

13. Noori, S, Verkleij, CPM, Zajec, M, Langerhorst, P, Bosman, PWC, de Rijke, YB, et al.. Monitoring the M-protein of multiple myeloma patients treated with a combination of monoclonal antibodies: the laboratory solution to eliminate interference. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021;59:1963–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2021-0399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Kumar, S, Paiva, B, Anderson, KC, Durie, B, Landgren, O, Moreau, P, et al.. International myeloma working group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e328–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30206-6.Search in Google Scholar

15. Clemens, PL, Yan, X, Lokhorst, HM, Lonial, S, Losic, N, Khan, I, et al.. Pharmacokinetics of daratumumab following intravenous infusion in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after prior proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory drug treatment. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017;56:915–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0477-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Kirchhoff, DC, Murata, K, Thoren, KL. Use of a daratumumab-specific immunofixation assay to assess possible immunotherapy interference at a major cancer center: our experience and recommendations. J Appl Lab Med 2021;6:1476–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfab055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Schmitz, MF, Otten, HG, Franssen, LE, van Dorp, S, Strooisma, T, Lokhorst, HM, et al.. Secondary monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2014;99:1846–53. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2014.111104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. van de Donk, NW, Otten, HG, El Haddad, O, Axel, A, Sasser, AK, Croockewit, S, et al.. Interference of daratumumab in monitoring multiple myeloma patients using serum immunofixation electrophoresis can be abrogated using the daratumumab IFE reflex assay (DIRA). Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:1105–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0888.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. CLSI. Evaluation of qualitative, binary output examination performance, 3rd ed. CLSI EP12. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

20. Pum, JKW. Evaluation of analytical performance of qualitative and semi-quantitative assays in the clinical laboratory. Clin Chim Acta 2019;497:197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.07.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Finn, G, Macé, S, Chu, R, van de Velde, H, Menad, S, Melki, M-T, et al.. Development of a hydrashift 2/4 isatuximab assay to mitigate interference with monoclonal protein detection on immunofixation electrophoresis in vitro diagnostic tests in multiple myeloma. Blood 2020;136:15. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136613.Search in Google Scholar

22. Mills, JR, Kohlhagen, MC, Willrich, MAV, Kourelis, T, Dispenzieri, A, Murray, DL. A universal solution for eliminating false positives in myeloma due to therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference. Blood 2018;132:670–2. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-05-848986.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Murray, DL. Bringing mass spectrometry into the care of patients with multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol 2022;115:790–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-022-03364-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Zajec, M, Jacobs, JFM, Groenen, P, de Kat Angelino, CM, Stingl, C, Luider, TM, et al.. Development of a targeted mass-spectrometry serum assay to quantify M-protein in the presence of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. J Proteome Res 2018;17:1326–33. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00890.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Kohlhagen, MC, Mills, JR, Willrich, MAV, Dasari, S, Dispenzieri, A, Murray, DL. Clearing drug interferences in myeloma treatment using mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem 2021;92:61–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2021.02.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Zajec, M, Langerhorst, P, VanDuijn, MM, Gloerich, J, Russcher, H, van Gool, AJ, et al.. Mass spectrometry for identification, monitoring, and minimal residual disease detection of M-proteins. Clin Chem 2020;66:421–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvz041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Kumar, SK, Callander, NS, Adekola, K, Anderson, L, Baljevic, M, Campagnaro, E, et al.. Multiple myeloma, version 3.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2020;18:1685–717. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2020.0057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Moreau, P, Kumar, SK, San Miguel, J, Davies, F, Zamagni, E, Bahlis, N, et al.. Treatment of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: recommendations from the international myeloma working group. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:e105–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30756-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2024-0416).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Circulating tumor DNA measurement: a new pillar of medical oncology?

- Reviews

- Circulating tumor DNA: current implementation issues and future challenges for clinical utility

- Circulating tumor DNA methylation: a promising clinical tool for cancer diagnosis and management

- Opinion Papers

- The final part of the CRESS trilogy – how to evaluate the quality of stability studies

- The impact of physiological variations on personalized reference intervals and decision limits: an in-depth analysis

- Computational pathology: an evolving concept

- Perspectives

- Dynamic mirroring: unveiling the role of digital twins, artificial intelligence and synthetic data for personalized medicine in laboratory medicine

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Macroprolactin in mothers and their babies: what is its origin?

- The influence of undetected hemolysis on POCT potassium results in the emergency department

- Quality control in the Netherlands; todays practices and starting points for guidance and future research

- QC Constellation: a cutting-edge solution for risk and patient-based quality control in clinical laboratories

- OILVEQ: an Italian external quality control scheme for cannabinoids analysis in galenic preparations of cannabis oil

- Using Bland-Altman plot-based harmonization algorithm to optimize the harmonization for immunoassays

- Comparison of a two-step Tempus600 hub solution single-tube vs. container-based, one-step pneumatic transport system

- Evaluating the HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay: a powerful approach to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma

- Insight into the status of plasma renin and aldosterone measurement: findings from 526 clinical laboratories in China

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Reference values for plasma and urine trace elements in a Swiss population-based cohort

- Stimulating thyrotropin receptor antibodies in early pregnancy

- Within- and between-subject biological variation estimates for the enumeration of lymphocyte deep immunophenotyping and monocyte subsets

- Diurnal and day-to-day biological variation of salivary cortisol and cortisone

- Web-accessible critical limits and critical values for urgent clinician notification

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Thyroglobulin measurement is the most powerful outcome predictor in differentiated thyroid cancer: a decision tree analysis in a European multicenter series

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Interaction of heparin with human cardiac troponin complex and its influence on the immunodetection of troponins in human blood samples

- Diagnostic performance of a point of care high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay and single measurement evaluation to rule out and rule in acute coronary syndrome

- Corrigendum

- Reference intervals of 24 trace elements in blood, plasma and erythrocytes for the Slovenian adult population

- Letters to the Editor

- Disturbances of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate homeostasis: incidence, probable causes, and outcome

- Validation of the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF)-test in heparinized and EDTA plasma for use in reflex testing algorithms for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

- Detection of urinary foam cells diagnosing the XGP with thrombopenia preoperatively: a case report

- Methemoglobinemia after sodium nitrite poisoning: what blood gas analysis tells us (and what it might not)

- Novel thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) variant identified in Malay individuals

- Congress Abstracts

- 56th National Congress of the Italian Society of Clinical Biochemistry and Clinical Molecular Biology (SIBioC – Laboratory Medicine)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Circulating tumor DNA measurement: a new pillar of medical oncology?

- Reviews

- Circulating tumor DNA: current implementation issues and future challenges for clinical utility

- Circulating tumor DNA methylation: a promising clinical tool for cancer diagnosis and management

- Opinion Papers

- The final part of the CRESS trilogy – how to evaluate the quality of stability studies

- The impact of physiological variations on personalized reference intervals and decision limits: an in-depth analysis

- Computational pathology: an evolving concept

- Perspectives

- Dynamic mirroring: unveiling the role of digital twins, artificial intelligence and synthetic data for personalized medicine in laboratory medicine

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Macroprolactin in mothers and their babies: what is its origin?

- The influence of undetected hemolysis on POCT potassium results in the emergency department

- Quality control in the Netherlands; todays practices and starting points for guidance and future research

- QC Constellation: a cutting-edge solution for risk and patient-based quality control in clinical laboratories

- OILVEQ: an Italian external quality control scheme for cannabinoids analysis in galenic preparations of cannabis oil

- Using Bland-Altman plot-based harmonization algorithm to optimize the harmonization for immunoassays

- Comparison of a two-step Tempus600 hub solution single-tube vs. container-based, one-step pneumatic transport system

- Evaluating the HYDRASHIFT 2/4 Daratumumab assay: a powerful approach to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma

- Insight into the status of plasma renin and aldosterone measurement: findings from 526 clinical laboratories in China

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Reference values for plasma and urine trace elements in a Swiss population-based cohort

- Stimulating thyrotropin receptor antibodies in early pregnancy

- Within- and between-subject biological variation estimates for the enumeration of lymphocyte deep immunophenotyping and monocyte subsets

- Diurnal and day-to-day biological variation of salivary cortisol and cortisone

- Web-accessible critical limits and critical values for urgent clinician notification

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Thyroglobulin measurement is the most powerful outcome predictor in differentiated thyroid cancer: a decision tree analysis in a European multicenter series

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Interaction of heparin with human cardiac troponin complex and its influence on the immunodetection of troponins in human blood samples

- Diagnostic performance of a point of care high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay and single measurement evaluation to rule out and rule in acute coronary syndrome

- Corrigendum

- Reference intervals of 24 trace elements in blood, plasma and erythrocytes for the Slovenian adult population

- Letters to the Editor

- Disturbances of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate homeostasis: incidence, probable causes, and outcome

- Validation of the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF)-test in heparinized and EDTA plasma for use in reflex testing algorithms for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

- Detection of urinary foam cells diagnosing the XGP with thrombopenia preoperatively: a case report

- Methemoglobinemia after sodium nitrite poisoning: what blood gas analysis tells us (and what it might not)

- Novel thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) variant identified in Malay individuals

- Congress Abstracts

- 56th National Congress of the Italian Society of Clinical Biochemistry and Clinical Molecular Biology (SIBioC – Laboratory Medicine)