Intermetallics of the types REPd3X2 and REPt3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; X=In, Sn) with substructures featuring tin and In atoms in distorted square-planar coordination

-

Simon Engelbert

Abstract

The intermetallic compounds RET3X2 (RE = La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; T = Pd, Pt; X = In, Sn) have been synthesized from the elements by arc-melting and subsequent annealing sequences in tube or induction furnaces. The samples were characterized through Guinier powder diffraction patterns, and several structures were refined from single crystal X-ray diffractometer data. These indium and tin intermetallics crystallize with the orthorhombic CePd3In2-type structure, space group Pnma. The palladium (platinum) and indium (tin) atoms in the RET3X2 structures build up complex three-dimensional [T3X2]δ− polyanionic networks in which the rare earth atoms fill cavities. The striking structural motifs concern the indium, respectively tin substructures, in which part of the indium and tin atoms have distorted square planar homoatomic coordination environments: In1In12In22 units in PrPd3In2 with interatomic distances 325 pm In1–In1 and 332 pm In1–In2 as well as Sn1Sn12Sn22 units in PrPt3Sn2 with the larger distances of 356 pm for Sn1–Sn1 and of 344 pm for Sn1–Sn2. Temperature dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements have indicated Pauli paramagnetism or diamagnetism for the lanthanum compounds, van-Vleck paramagnetism for SmPt3In2 and Curie-Weiss paramagnetism for the remaining compounds. Antiferromagnetic ordering was detected at TN = 4.0(1) K for CePt3In2 and at TN = 3.5(1) K for SmPt3In2. CePt3In2 shows a metamagnetic transition at an external magnetic field of 47(3) kOe.

1 Introduction

Many intermetallic compounds of a given structure type allow for geometrical and electronic flexibility. Especially rare earth-based phases often exist for several, sometimes for all rare earth elements (RE) [1]. The structures tolerate the difference in size imposed by the lanthanide contraction. For binaries (RExTy or RExXz) and ternaries (RExTyXz), substitution of a transition metal (T) or an element of the p block (X) leads to a change in the valence electron count and consequently the geometrical and electronic changes induce variations in the magnetic and transport properties.

In the case of the p element exchange, many indium and tin based intermetallic compounds have been studied. The differences in size (covalent radii of 150 pm for indium and 140 pm for tin [2]) and the location in the Periodic Table lead to changes in the unit cell parameters, to a different band structure and thus to changes in the physical properties. A typical example concerns the Cu3Au-type phases La3In and La3Sn which both show transitions to a superconducting state at TC=9.7 K (La3In) and TC=6.2 K (La3Sn) [3]. More drastic is the situation for Eu2In (a=744.5, b=557.3, c=1030.6 pm) [4] and Eu2Sn (a=785.7, b=539.0, c=991.0 pm) [5] which both crystallize with the orthorhombic Co2Si type. Besides substantial changes in the lattice parameters one also observes considerable differences in the magnetic ground state. Eu2In is a TC=58 K ferromagnet, while Eu2Sn is ordered antiferromagnetically at the much lower Néel temperature of TN=31 K [6].

As for examples of ternary phases we point to Ce2Pd2In (TN=4.3 K) [7] and Ce2Pd2Sn (TN=4.2 K) [8]. Both order antiferromagnetically with only slightly different Néel temperatures. This is also the case for EuPdIn [9] and EuPdSn [10], [11], [12] which both order antiferromagnetically below TN=13 K. Their isotypic platinum counterparts EuPtIn [13] and EuPtSn [11] also show antiferromagnetic ground states; however, at different Néel temperatures of TN=16 K (EuPtIn) and TN=28.5 K (EuPtSn). Although for the ternary systems RE-T-In [14] and RE-T-Sn [15], [16] a large number of compounds has been described which allow for a study of this delicate interplay, by far not all compounds have yet been discovered and only few isothermal sections have been completely investigated.

Phase analytical studies in the palladium based systems revealed the pairs of orthorhombic compounds LaPd3In2 [17]/CePd3In2 (a=1026.6, b=462.34, c=987.79 pm) [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22] and LaPd3Sn2 [23]/CePd3Sn2 (a=972.89, b=476.63, c=1016.92 pm) [23] with CePd3In2-type structure, space group Pnma. Again, the different structural distortions found for CePd3In2 and CePd3Sn2 lead to changes in the Ce–Ce distances and thus the magnetic exchange coupling. This is expressed in the different Néel temperatures of TN=2.1 K (CePd3In2) and TN=0.6 K (CePd3Sn2).

In the present study we extended the substitution studies on CePd3In2-type phases with respect to the rare earth element, the transition metal and the p-element sites. Herein we report on the compounds REPd3In2 (RE=La, Pr, Nd, Sm), REPd3Sn2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm), REPt3In2 (RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb) and REPt3Sn2 (RE=Ce–Nd, Sm). The existence of PrPd3In2 and NdPd3In2 was claimed during a phase analytical study of the Pr-Pd-In and Nd-Pd-In systems [18]; however, no lattice parameters were reported. The same holds true for LaPd3Sn2 [23]. All new compounds have been structurally characterized and were studied with respect to their magnetic properties; in the case of the stannides 119Sn Mössbauer spectral data are also provided.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis

The starting materials for the synthesis of the ternary indium and tin compounds were ingots of the rare earth elements (Chempur or smart elements, 99.9%), sheets of palladium and platinum powder (Agosi, >99.9%), an indium bar (smart elements 99.99%) and tin droplets (Merck 99.9%). The moisture sensitive rare earth elements were cut under dried cyclohexane and kept under argon in Schlenk tubes prior to the reactions. For the platinum containing compounds, the Pt powder was cold-pressed into pellets, arc-melted [24] under an atmosphere of 800 mbar dry argon (Westfalen, 99.998%; purified over titanium sponge (T=870 K), silica gel, and molecular sieves) and subsequently cut into suitable pieces. The elements were weighed in the ideal ratios 1:3:2 and arc-melted under an argon atmosphere of 800 mbar. The product buttons were re-melted three times to ensure homogeneity. Afterwards, the samples were sealed in carbon coated evacuated silica ampoules and annealed with different temperature sequences using resistance furnaces. The purity of the samples and the crystal growth strongly depended on the annealing sequences. These are summarized in detail in the paragraphs below.

The REPd3In2 samples and LaPd3Sn2 were annealed at T=773 K for 14 days and subsequently cooled at a rate of 5 K h−1 to room temperature. The single crystals of PrPd3In2 and NdPd3In2 were selected from those samples. The PrPd3In2 sample for the magnetic measurement had a different heat treatment history. It was first annealed at 873 K for 7 days and then cooled to room temperature at a rate of 20 K h−1.

The REPt3In2 samples were heated at 1023 K for 35 days and cooled to room temperature at a rate of 5 K h−1 (11 days and 10 K h−1 for LaPt3In2). For the growth of PrPt3In2 crystals, a second sample was inductively heated (high-frequency furnace type 1.5/300, Hüttinger Elektronik, Freiburg, Germany) in a water-cooled evacuated silica ampoule (the experimental setup is documented elsewhere [25]). The sample was annealed for 10 min barely below the melting point and gradually cooled to room temperature within 7 h. Afterwards the ampoule was placed in a resistance furnace, heated to 973 K and cooled at a rate of 10 K h−1 to room temperature.

The remaining REPd3Sn2 samples were annealed at 1173 K for 7 days and cooled to room temperature at a rate of 5 K h−1 (5 days and 20 K h−1 for CePd3Sn2). The single crystals of PrPd3Sn2 and NdPd3Sn2 were isolated from these samples. The magnetic measurement of PrPd3Sn2 was performed on a sample heated at 1173 K for 7 days and cooled to room temperature at a rate of 20 K h−1.

The CePt3Sn2 and PrPt3Sn2 samples for the magnetic measurements were annealed at 873 K for 14 days, then at 1073 K for 7 days and finally cooled to room temperature at a rate of 10 K h−1. The NdPt3Sn2 sample was annealed at 973 K for a period of 14 days and afterwards at 1073 K for 16 days, followed by quenching in water. The single crystals were obtained from different samples. The PrPt3Sn2 single crystal was isolated from a sample which was annealed at 1223 K for 21 days and cooled to room temperature at a rate of 5 K h−1. The NdPt3Sn2 single crystal was isolated from an inductively annealed sample, treated similarly as PrPt3In2. The sample was annealed barely below the melting point for 10 min and gradually cooled down to room temperature within 6 h. Then, the sample was placed in a resistance furnace, heated to 1073 K for 2 days followed by cooling to room temperature at a rate of 2 K h−1.

The different annealing sequences tested for the SmPd3Sn2 and SmPt3Sn2 samples always resulted in increasing amounts of impurity phases. The unit cell parameters were thus refined from the arc-melted samples. The SmPd3In2, GdPt3In2 and TbPt3In2 samples were not single-phase. They always contained by-products which were not diminished after the heat treatments.

All RET3X2 samples are silvery with metallic lustre and stable in air over several months.

2.2 X-ray diffraction

The polycrystalline RET3X2 samples were characterized through their Guinier powder diffraction patterns using an Enraf-Nonius FR552 camera, equipped with an imaging plate detector (Fuji film BAS-1800) and CuKα1 radiation. α-Quartz (a=491.30, c=540.46 pm) was taken as an internal standard. The orthorhombic lattice parameters (Table 1) were obtained from least-squares refinements. All experimental patterns were compared to calculate ones (Lazy Pulverix routine [26]) in order to ensure correct indexing. The powder data (Table 1) is in good agreement with the single crystal lattice parameters (Tables 2 and 3).

Lattice parameters (Guinier powder and literature data) of the compounds RET3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn).

| Compound | a (pm) | b (pm) | c (pm) | V (nm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indium compounds | ||||

| LaPd3In2 | 1029.1(2) | 463.9(1) | 995.2(2) | 0.4751 |

| LaPd3In2 [17] | 1029.86(14) | 464.24(6) | 994.98(13) | 0.4757 |

| CePd3In2 [19] | 1028.6(1) | 462.5(1) | 988.1(2) | 0.4701 |

| CePd3In2 [20] | 1026.5(24) | 462.34(16) | 987.79(19) | 0.4688 |

| CePd3In2 [17] | 1027.88(8) | 462.37(4) | 987.65(9) | 0.4694 |

| CePd3In2 [21] | 1026.5(4) | 462.3(6) | 987.8(2) | 0.4688 |

| PrPd3In2 | 1028.9(3) | 461.0(1) | 983.5(2) | 0.4665 |

| NdPd3In2 | 1029.2(2) | 459.58(6) | 978.8(2) | 0.4630 |

| SmPd3In2 | 1028.5(3) | 457.9(1) | 974.4(3) | 0.4589 |

| LaPt3In2 | 1027.2(1) | 460.11(8) | 1005.5(2) | 0.4752 |

| CePt3In2 | 1027.8(2) | 458.7(1) | 997.9(2) | 0.4705 |

| PrPt3In2 | 1027.7(1) | 456.86(7) | 993.5(2) | 0.4665 |

| NdPt3In2 | 1029.8(2) | 455.47(8) | 989.8(2) | 0.4643 |

| SmPt3In2 | 1032.7(1) | 453.24(7) | 982.9(1) | 0.4601 |

| GdPt3In2 | 1034.8(2) | 451.74(7) | 976.8(2) | 0.4566 |

| TbPt3In2 | 1037.1(2) | 450.29(7) | 972.1(1) | 0.4540 |

| Tin compounds | ||||

| LaPd3Sn2 | 978.3(1) | 478.54(7) | 1024.6(1) | 0.4797 |

| CePd3Sn2 | 973.5(1) | 477.2(1) | 1018.1(2) | 0.4730 |

| CePd3Sn2 [23] | 972.89(1) | 476.63(1) | 1016.92(1) | 0.4716 |

| PrPd3Sn2 | 971.69(9) | 476.81(9) | 1014.8(2) | 0.4702 |

| NdPd3Sn2 | 970.3(2) | 475.5(1) | 1012.8(3) | 0.4673 |

| SmPd3Sn2 | 967.0(1) | 474.07(8) | 1008.4(2) | 0.4623 |

| CePt3Sn2 | 964.8(3) | 475.8(1) | 1034.7(2) | 0.4750 |

| PrPt3Sn2 | 962.8(2) | 474.7(1) | 1033.6(2) | 0.4724 |

| NdPt3Sn2 | 961.4(2) | 473.7(1) | 1029.9(2) | 0.4690 |

| SmPt3Sn2 | 959.9(2) | 471.54(7) | 1026.5(2) | 0.4646 |

Crystal data and structure refinement of RET3In2 (RE=Pr, Nd; T=Pd, Pt), space group Pnma, Z=4, wavelength λ=71.073 pm (MoKα radiation).

| Empirical formula | PrPd3In2 | NdPd3In2 | PrPt3In2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula weight, g mol−1 | 689.8 | 693.1 | 955.8 |

| Lattice parameters (single crystal data) | |||

| a, pm | 1029.03(2) | 1028.32(6) | 1028.91(7) |

| b, pm | 460.99(4) | 459.83(3) | 456.94(4) |

| c, pm | 983.49(4) | 980.08(7) | 993.99(7) |

| Cell volume V, nm3 | 0.4665 | 0.4634 | 0.4673 |

| Calcd. density, g cm−3 | 9.82 | 9.93 | 13.58 |

| Crystal size, μm3 | 20×20×80 | 40×50×70 | 30×30×60 |

| Diffractometer type | StadiVari | IPDS-II | IPDS-II |

| Detector distance, mm | 40 | 70 | 70 |

| Exposure time, s | 48 | 300 | 720 |

| Abs. coefficient, mm−1 | 31.1 | 32.0 | 109.2 |

| F(000), e | 1180 | 1184 | 1564 |

| θ range, ° | 2–34 | 2–34 | 2–34 |

| Range hkl | ±15, ±7, ±15 | ±15, ±7, ±14 | ±15, ±7, ±15 |

| Total no. reflections | 14 077 | 5887 | 8602 |

| Independent reflections/Rint | 996/0.0264 | 967/0.0349 | 994/0.0536 |

| Reflections with I>3 σ(I) | 876 | 738 | 791 |

| Data/parameters | 996/38 | 967/38 | 994/38 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.56 |

| R1/wR2 for I>3 σ(I) | 0.0106/0.0127 | 0.0149/0.0148 | 0.0283/0.0293 |

| R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0137/0.0134 | 0.0278/0.0163 | 0.0410/0.0308 |

| Extinction coefficient | 99(5) | 216(8) | 342(14) |

| Larg. diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 0.39/−0.50 | 0.75/−0.99 | 2.87/−2.79 |

Crystal data and structure refinement of RET3Sn2 (RE=Pr, Nd; T=Pd, Pt), space group Pnma, Z=4, wavelength λ=71.073 pm (MoKα radiation).

| Empirical formula | PrPd3Sn2 | NdPd3Sn2 | PrPt3Sn2 | NdPt3Sn2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula weight, g mol−1 | 697.5 | 700.9 | 963.6 | 966.9 |

| Lattice parameters (single crystal data) | ||||

| a, pm | 971.85(6) | 969.71(6) | 962.33(7) | 962.01(4) |

| b, pm | 476.33(3) | 475.15(3) | 474.35(7) | 473.62(2) |

| c, pm | 1015.28(6) | 1011.87(7) | 1032.67(7) | 1031.03(4) |

| Cell volume V, nm3 | 0.4670 | 0.4662 | 0.4714 | 0.4698 |

| Calcd. density, g cm−3 | 9.86 | 9.99 | 13.58 | 13.67 |

| Crystal size, μm3 | 30×30×100 | 50×50×100 | 30×40×40 | 20×50×85 |

| Diffractometer type | IPDS-II | IPDS-II | IPDS-II | StadiVari |

| Detector distance, mm | 60 | 70 | 60 | 40 |

| Exposure time, s | 1800 | 240 | 1800 | 36 |

| Abs. coefficent, mm−1 | 31.7 | 32.6 | 109.1 | 110.1 |

| F(000), e | 1188 | 1192 | 1572 | 1576 |

| θ range, ° | 2–35 | 2–34 | 2–35 | 2–34 |

| Range hkl | ±15, ±7, ±13 | ±14, ±7, ±15 | ±15, ±7, ±16 | ±15, ±7, ±16 |

| Total no. reflections | 6028 | 7832 | 10597 | 14066 |

| Independent reflections/Rint | 1085/0.0518 | 995/0.0452 | 1131/0.0606 | 1034/0.0471 |

| Reflections with I>3 σ(I) | 751 | 706 | 836 | 871 |

| Data/parameters | 1085/38 | 995/38 | 1131/38 | 1034/38 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 1.28 | 0.98 | 1.34 | 1.34 |

| R1/wR2 for I>3 σ(I) | 0.0291/0.0263 | 0.0175/0.0169 | 0.0261/0.0249 | 0.0204/0.0222 |

| R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0610/0.0292 | 0.0370/0.0197 | 0.0500/0.0278 | 0.0259/0.0230 |

| Extinction coefficient | 103(12) | 233(8) | 87(5) | 158(5) |

| Larg. diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 2.82/–3.17 | 1.38/–1.47 | 4.05/–2.70 | 1.59/–1.70 |

The shape of the small single crystals depended on the element combination. After careful mechanical fragmentation either lath-shaped crystals or small blocks were obtained. The crystals were glued to quartz fibres using beeswax and their quality was first tested on a Buerger precession camera (white Mo radiation). Most intensity data sets were collected on a STOE IPDS-II diffractometer (graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation) in oscillation mode or on a STOE StadiVari diffractometer equipped with a Mo micro focus source and a Pilatus detection system. Numerical absorption corrections were applied to all data sets. Due to a Gaussian-shaped profile of the micro focus X-ray source scaling was applied along with numerical absorption corrections to the StadiVari data sets. Details of the data collections and the refinement data are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

2.3 Structure refinements

The seven data sets showed primitive orthorhombic lattices and the systematic extinctions were compatible with space group Pnma, in agreement with the previous work on the prototype CePd3In2 [20]. The atomic parameters of the cerium compound were taken as starting values and the structures were refined with full-matrix least-squares on

Atomic coordinates and displacement parameters (in pm2) of RET3X2 (RE=Pr, Nd; T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn) (space group Pnma, all atoms lie on Wyckoff positions 4c: x, 1/4, z).

| Atom | x | z | U11 | U22 | U33 | U13 | Ueqa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrPd3In2 | |||||||

| Pr | 0.23036(2) | 0.05510(2) | 162(1) | 174(1) | 139(1) | −7(1) | 158(1) |

| Pd1 | 0.12011(2) | 0.35419(3) | 193(1) | 180(1) | 238(1) | 42(1) | 204(1) |

| Pd2 | 0.24172(2) | 0.76017(2) | 156(1) | 162(1) | 158(1) | 6(1) | 159(1) |

| Pd3 | 0.47396(2) | 0.60633(2) | 167(1) | 184(1) | 173(1) | −14(1) | 175(1) |

| In1 | 0.01493(2) | 0.61574(2) | 170(1) | 166(1) | 157(1) | −11(1) | 164(1) |

| In2 | 0.39592(2) | 0.33984(2) | 175(1) | 146(1) | 167(1) | −20(1) | 163(1) |

| NdPd3In2 | |||||||

| Nd | 0.22960(3) | 0.05446(3) | 87(1) | 104(1) | 73(1) | −6(1) | 88(1) |

| Pd1 | 0.12125(4) | 0.35396(5) | 118(2) | 109(2) | 171(3) | 48(1) | 133(1) |

| Pd2 | 0.24125(4) | 0.75878(4) | 78(2) | 89(2) | 92(2) | 8(1) | 86(1) |

| Pd3 | 0.47365(4) | 0.60589(5) | 92(2) | 110(2) | 105(2) | −17(1) | 102(1) |

| In1 | 0.01451(3) | 0.61510(4) | 95(1) | 95(2) | 90(2) | −12(1) | 93(1) |

| In2 | 0.39616(3) | 0.33869(4) | 100(2) | 74(2) | 97(2) | −20(1) | 90(1) |

| PrPt3In2 | |||||||

| Pr | 0.23063(8) | 0.05435(8) | 131(3) | 138(3) | 120(3) | −6(2) | 130(2) |

| Pt1 | 0.11978(6) | 0.35423(7) | 154(3) | 154(2) | 200(3) | 37(2) | 169(1) |

| Pt2 | 0.24129(6) | 0.75829(5) | 122(2) | 138(2) | 128(2) | −1(2) | 129(1) |

| Pt3 | 0.47062(6) | 0.60496(6) | 140(2) | 172(2) | 170(3) | −13(2) | 161(1) |

| In1 | 0.01799(10) | 0.61360(11) | 131(4) | 148(4) | 146(5) | −18(3) | 142(2) |

| In2 | 0.39628(10) | 0.33935(11) | 148(4) | 137(4) | 148(5) | −10(3) | 144(2) |

| PrPd3Sn2 | |||||||

| Pr | 0.23816(5) | 0.06816(5) | 85(2) | 103(3) | 89(2) | −12(2) | 93(2) |

| Pd1 | 0.09995(9) | 0.36107(9) | 129(3) | 97(5) | 228(4) | 40(3) | 151(2) |

| Pd2 | 0.25345(8) | 0.77422(7) | 78(2) | 119(4) | 110(3) | −2(2) | 103(2) |

| Pd3 | 0.48142(7) | 0.59679(7) | 95(3) | 144(5) | 115(3) | −10(2) | 118(2) |

| Sn1 | 0.02202(6) | 0.62929(6) | 81(2) | 97(4) | 110(2) | −7(2) | 96(2) |

| Sn2 | 0.38684(7) | 0.35120(7) | 105(3) | 88(4) | 114(3) | −29(2) | 102(2) |

| NdPd3Sn2 | |||||||

| Nd | 0.23780(4) | 0.06811(3) | 84(2) | 95(2) | 81(1) | −10(1) | 87(1) |

| Pd1 | 0.10004(6) | 0.36074(6) | 130(2) | 91(3) | 216(2) | 40(2) | 146(1) |

| Pd2 | 0.25351(6) | 0.77394(5) | 75(2) | 111(2) | 99(2) | 3(2) | 95(1) |

| Pd3 | 0.48131(5) | 0.59668(5) | 94(2) | 136(3) | 104(2) | −6(2) | 112(1) |

| Sn1 | 0.02224(5) | 0.62849(4) | 73(2) | 97(2) | 94(2) | −6(2) | 88(2) |

| Sn2 | 0.38650(5) | 0.35105(7) | 103(2) | 83(2) | 98(2) | −27(1) | 95(2) |

| PrPt3Sn2 | |||||||

| Pr | 0.23850(7) | 0.07062(6) | 86(3) | 95(2) | 94(2) | −7(2) | 92(1) |

| Pt1 | 0.09849(6) | 0.36272(6) | 133(2) | 108(2) | 198(2) | 27(2) | 146(1) |

| Pt2 | 0.25127(6) | 0.77109(5) | 78(2) | 128(2) | 105(2) | 1(2) | 104(1) |

| Pt3 | 0.47848(5) | 0.59419(5) | 99(2) | 153(2) | 124(2) | −6(2) | 125(1) |

| Sn1 | 0.02206(9) | 0.62653(8) | 81(3) | 96(3) | 127(3) | −9(3) | 101(2) |

| Sn2 | 0.38624(10) | 0.35230(9) | 116(4) | 97(3) | 120(3) | −32(3) | 111(2) |

| NdPt3Sn2 | |||||||

| Nd | 0.23783(5) | 0.07029(5) | 209(2) | 225(2) | 201(2) | −10(2) | 212(2) |

| Pt1 | 0.09830(4) | 0.36234(4) | 250(2) | 219(2) | 293(2) | 24(1) | 254(1) |

| Pt2 | 0.25164(4) | 0.77085(4) | 202(1) | 243(2) | 212(1) | 2(1) | 219(1) |

| Pt3 | 0.47830(4) | 0.59369(4) | 226(2) | 269(2) | 230(2) | −4(2) | 242(1) |

| Sn1 | 0.02269(6) | 0.62591(6) | 210(2) | 211(3) | 218(2) | −13(2) | 213(1) |

| Sn2 | 0.38608(7) | 0.35171(6) | 235(3) | 215(3) | 226(3) | −30(2) | 225(2) |

aThe isotropic displacement parameter Ueq is defined as: Ueq=1/3 (U11+U22+U33) (pm2); U12=U23=0. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Interatomic distances (pm) in PrT3X2 (T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn).

| PrPd3In2 | PrPt3In2 | PrPd3Sn2 | PrPt3Sn2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr: | 1 | Pd2 | 290.3 | 1 | Pt2 | 294.5 | 1 | Pd2 | 298.8 | 1 | Pt3 | 302.6 |

| 2 | Pd2 | 307.6 | 2 | Pt2 | 306.8 | 1 | Pd3 | 300.5 | 1 | Pt2 | 309.6 | |

| 1 | Pd3 | 307.9 | 1 | Pt3 | 310.9 | 2 | Pd2 | 317.1 | 2 | Pt2 | 315.0 | |

| 1 | Pd1 | 315.3 | 2 | Pt3 | 312.4 | 2 | Pd3 | 321.1 | 2 | Pt3 | 316.9 | |

| 2 | Pd3 | 316.0 | 1 | Pt1 | 319.2 | 1 | Sn2 | 321.6 | 1 | Sn2 | 323.8 | |

| 1 | In2 | 327.8 | 1 | In2 | 330.6 | 1 | Pd1 | 326.3 | 1 | Pt1 | 330.4 | |

| 1 | In1 | 337.6 | 2 | In2 | 339.0 | 2 | Sn1 | 339.0 | 2 | Sn1 | 335.7 | |

| 2 | In2 | 338.9 | 1 | In1 | 339.5 | 1 | Sn1 | 341.0 | 1 | Sn1 | 340.5 | |

| 2 | Pd1 | 340.4 | 2 | Pt1 | 339.8 | 2 | Sn2 | 346.4 | 1 | Sn2 | 348.2 | |

| 2 | In1 | 354.1 | 2 | In1 | 350.1 | 1 | Sn2 | 351.1 | 2 | Sn2 | 348.6 | |

| 1 | In2 | 359.3 | 1 | In2 | 359.9 | 2 | Pd1 | 354.5 | 1 | Pt1 | 353.2 | |

| 1 | Pd1 | 358.9 | 2 | Pt1 | 356.3 | |||||||

| T1: | 2 | In1 | 270.8 | 2 | In1 | 270.8 | 2 | Sn1 | 266.2 | 2 | Sn1 | 264.3 |

| 1 | In1 | 279.1 | 1 | In1 | 278.3 | 1 | Sn2 | 279.0 | 1 | Sn2 | 277.1 | |

| 1 | In2 | 284.2 | 1 | In2 | 284.9 | 1 | Sn1 | 282.7 | 1 | Sn1 | 282.2 | |

| 2 | Pd2 | 286.2 | 2 | Pt2 | 285.9 | 2 | Pd2 | 291.2 | 2 | Pt2 | 293.4 | |

| 1 | In2 | 299.4 | 1 | In2 | 299.8 | 1 | Sn2 | 298.9 | 1 | Sn2 | 301.7 | |

| 1 | Pr | 315.3 | 1 | Pr | 319.2 | 1 | Pr | 326.3 | 1 | Pr | 330.4 | |

| 2 | Pr | 340.4 | 2 | Pr | 339.8 | 2 | Pr | 354.5 | 1 | Pr | 353.2 | |

| 2 | Pd3 | 349.2 | 2 | Pt3 | 349.6 | 1 | Pr | 358.9 | 2 | Pr | 356.3 | |

| 2 | Pd3 | 367.4 | 2 | Pt3 | 372.3 | |||||||

| T2: | 1 | In1 | 273.2 | 1 | In1 | 271.1 | 1 | Sn1 | 268.8 | 1 | Sn1 | 266.3 |

| 2 | In2 | 281.7 | 2 | In2 | 280.6 | 1 | Sn1 | 278.8 | 1 | Sn1 | 281.2 | |

| 1 | Pd3 | 282.8 | 1 | Pt3 | 280.9 | 2 | Sn2 | 285.3 | 2 | Sn2 | 284.3 | |

| 2 | Pd1 | 286.2 | 2 | Pt1 | 285.9 | 1 | Pd3 | 285.5 | 1 | Pt3 | 284.2 | |

| 1 | Pr | 290.3 | 1 | Pr | 294.5 | 2 | Pd1 | 291.2 | 2 | Pt1 | 293.4 | |

| 1 | Pd3 | 305.2 | 2 | Pr | 306.8 | 1 | Pd3 | 295.0 | 1 | Pt3 | 297.1 | |

| 1 | In1 | 306.5 | 1 | Pt3 | 309.9 | 1 | Pr | 298.8 | 1 | Pr | 309.6 | |

| 2 | Pr | 307.6 | 1 | In1 | 311.9 | 2 | Pr | 317.1 | 2 | Pr | 315.0 | |

| T3: | 2 | In2 | 271.8 | 2 | In2 | 272.1 | 1 | Sn2 | 265.7 | 1 | Sn2 | 265.1 |

| 1 | In2 | 274.1 | 1 | In2 | 274.9 | 2 | Sn2 | 275.5 | 2 | Sn2 | 276.1 | |

| 1 | In1 | 276.6 | 1 | Pt2 | 280.9 | 1 | Sn1 | 280.9 | 1 | Pt2 | 284.9 | |

| 1 | Pd2 | 282.8 | 1 | In1 | 284.0 | 1 | Pd2 | 285.5 | 1 | Sn1 | 291.4 | |

| 1 | Pd2 | 305.2 | 1 | Pt2 | 309.9 | 1 | Pd2 | 295.0 | 1 | Pt2 | 297.1 | |

| 1 | Pr | 307.9 | 1 | Pr | 310.9 | 1 | Pr | 300.5 | 1 | Pr | 302.6 | |

| 2 | Pd3 | 315.8 | 2 | Pr | 312.4 | 2 | Pd3 | 310.9 | 2 | Pt3 | 309.5 | |

| 2 | Pr | 316.0 | 2 | Pt3 | 315.3 | 2 | Pr | 321.1 | 2 | Pr | 316.9 | |

| 2 | Pd1 | 349.2 | 2 | Pt1 | 349.6 | 2 | Pd1 | 367.4 | 2 | Pt1 | 372.3 | |

| X1: | 2 | Pd1 | 270.8 | 2 | Pt1 | 270.8 | 2 | Pd1 | 266.2 | 2 | Pt1 | 264.3 |

| 1 | Pd2 | 273.2 | 1 | Pt2 | 271.1 | 1 | Pd2 | 268.8 | 1 | Pt2 | 266.3 | |

| 1 | Pd3 | 276.6 | 1 | Pt1 | 278.3 | 1 | Pd2 | 278.8 | 1 | Pt2 | 281.2 | |

| 1 | Pd1 | 279.1 | 1 | Pt3 | 284.0 | 1 | Pd3 | 280.9 | 1 | Pt1 | 282.2 | |

| 1 | Pd2 | 306.5 | 1 | Pt2 | 311.9 | 1 | Pd1 | 282.7 | 1 | Pt3 | 291.4 | |

| 2 | In1 | 325.4 | 2 | In1 | 323.4 | 2 | Pr | 339.0 | 2 | Pr | 335.7 | |

| 2 | In2 | 331.8 | 2 | In2 | 332.2 | 2 | Sn2 | 339.6 | 1 | Pr | 340.5 | |

| 1 | Pr | 337.6 | 1 | Pr | 339.5 | 1 | Pr | 341.0 | 2 | Sn2 | 344.1 | |

| 2 | Pr | 354.1 | 2 | Pr | 350.1 | 2 | Sn1 | 357.0 | 2 | Sn1 | 355.5 | |

| X2: | 2 | Pd3 | 271.8 | 2 | Pt3 | 272.1 | 1 | Pd3 | 265.7 | 1 | Pt3 | 265.1 |

| 1 | Pd3 | 274.1 | 1 | Pt3 | 274.9 | 2 | Pd3 | 275.5 | 2 | Pt3 | 276.1 | |

| 2 | Pd2 | 281.7 | 2 | Pt2 | 280.6 | 1 | Pd1 | 279.0 | 1 | Pt1 | 277.1 | |

| 1 | Pd1 | 284.2 | 1 | Pt1 | 284.9 | 2 | Pd2 | 285.3 | 2 | Pt2 | 284.2 | |

| 1 | Pd1 | 299.4 | 1 | Pt1 | 299.8 | 1 | Pd1 | 298.9 | 1 | Pt1 | 301.7 | |

| 1 | Pr | 327.8 | 1 | Pr | 330.6 | 1 | Pr | 321.6 | 1 | Pr | 323.8 | |

| 2 | In1 | 331.8 | 2 | In1 | 332.2 | 2 | Sn1 | 339.6 | 2 | Sn1 | 344.1 | |

| 2 | Pr | 338.9 | 2 | Pr | 339.0 | 2 | Pr | 346.4 | 1 | Pr | 348.2 | |

| 1 | Pr | 359.3 | 1 | Pr | 359.9 | 1 | Pr | 351.1 | 2 | Pr | 348.6 | |

All distances of the first coordination spheres are listed. Standard deviations are equal or smaller than 0.2 pm.

The NdPt3Sn2 crystal showed slightly enhanced displacement parameters for all atoms. We collected an additional data set at 90 K. The lattice and displacement parameters showed an almost isotropic shrinking, giving no hint for a lowering of the space group symmetry.

CCDC 1959118–1959122, 1959124 and 1959211 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

2.4 EDX data

The single crystals studied on the diffractometers were additionally semi-quantitatively analysed by EDX, using a Zeiss EVO® MA10 scanning electron microscope in variable pressure mode (60 Pa) with PrF3, NdF3, Pd, Pt, InAs and Sn as standards. Four point analyses were carried out for each crystal. The averaged values were within 1–2 at% close to the ideal composition. No impurity elements were observed.

2.5 Physical property measurements

Magnetic property measurements were conducted on X-ray phase pure samples of the general composition RET3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm; T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn) by means of magnetic susceptibility measurements. For this purpose, approximately 20 mg of each sample were attached to a brass sample holder rod of a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) of a Quantum Design Physical-Property-Measurement-System (PPMS) using Kapton foil. Magnetization experiments were carried out in the temperature range of 2.5–300 K with external magnetic field strengths of up to 80 kOe (1 kOe=7.96×104 A m−1). For heat capacity measurements performed on SmPt3In2, a small piece of the previously investigated sample was fixed to a pre-calibrated heat capacity puck using Apiezon-N® grease and investigated in the temperature range of 2–25 K without an applied external field.

2.6 Mössbauer spectroscopy

A Ca119mSnO3 source was used for the Mössbauer spectroscopic characterization of the stannides REPd3Sn2 (RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd) and REPt3Sn2 (RE=Ce, Pr, Nd). The measurements were conducted in the usual transmission geometry using a commercial nitrogen bath cryostat. The source was kept at room temperature. The REPt3Sn2 samples were cooled to 78 K while the REPd3Sn2 samples were measured at room temperature. All samples were placed in thin-walled PMMA containers and their ideal absorber thickness was calculated according to the work of Long et al. [28]. The total counting time per spectrum was between 6 and 24 h. Only in the case of CePt3Sn2 the counting time was extended to 3 days to obtain better resolution. The spectra were fitted with the WinNormosforIgor6 software package [29].

3 Results

3.1 Crystal chemistry

The CePd3In2-type structure was originally described in 2004 by Nesterenko et al. [20], space group Pnma, Pearson symbol oP24 and Wyckoff sequence c6. Besides the prototype, isotypic LaPd3In2 [17] was characterized as the Pauli-paramagnetic counterpart of the cerium compound. Recently, also the isotypic stannides LaPd3Sn2 and CePd3Sn2 [23] have been reported; however, only the cerium compound has been structurally characterized. Herein we report on a complete structural characterization of the so far existing series of REPd3In2 and REPd3Sn2 phases and their platinum counterparts.

The refined lattice parameters of all CePd3In2-type phases along with some literature data are summarized in Table 1. This structure type shows some geometrical restrictions. The existence range is not similar for all Pd(Pt)/In(Sn) combinations. Within all four series we observe a decrease of the cell volume with increasing atomic number, a consequence of the lanthanide contraction. All cerium compounds nicely fit into the volume plots, indicating trivalent cerium. From Table 1 it is readily evident that the a and c lattice parameters of the indium and tin series show drastic differences. We address this feature in more detail below when discussing the p-element substructures.

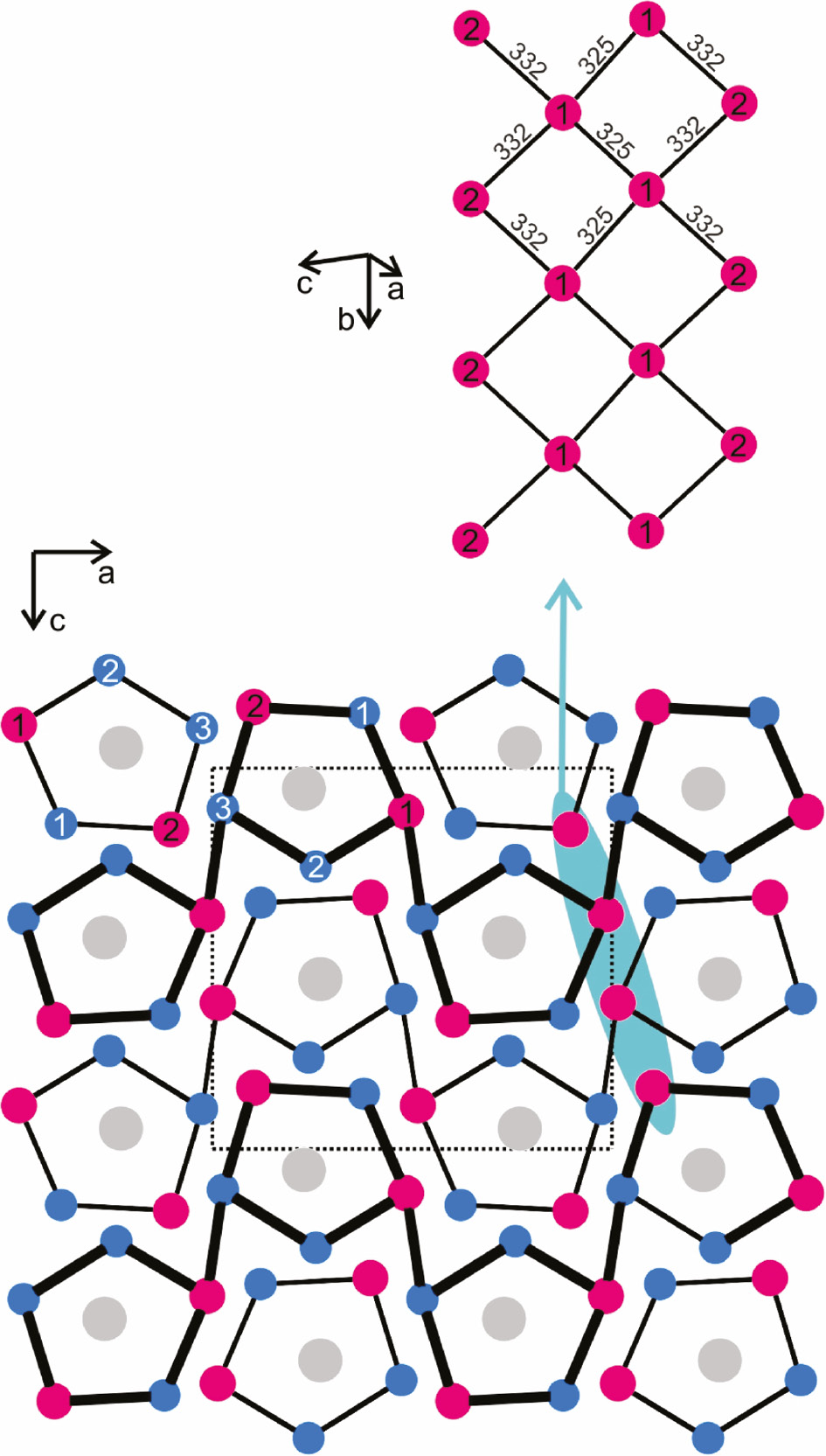

As an example we discuss the PrPd3In2 structure in more detail. A projection of its unit cell is presented in Fig. 1. All atoms lie on mirror planes at y=1/4 and y=3/4, indicated by thin and thick lines in the drawing. A striking geometrical motif is the slightly distorted pentagonal prismatic coordination of the praseodymium atoms by two Pd3In2 pentagons. These prisms are capped on the rectangular faces by further palladium and tin atoms. Such pentagonal prisms are a general structural motif in many of the rare earth-transition metal-indides and stannides [14], [15]. Two prominent examples are the indium-based structures of Ce4Pd10In21 [30] and Yb2Pd6In13 [31]. A complex tessellation of different pentagons has been observed in the stannides Sm3Pd4.95Sn5 and Sm6Pd9.82Sn11 [32].

The crystal structure of PrPd3In2. Praseodymium, palladium and indium atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. (bottom) Projection of the structure along the b axis. Atoms connected by thin (y=1/4) and thick (y=3/4) lines are shifted by half a translation period. (top) Cutout of the indium substructure. The crystallographically independent sites and relevant In–In distances in the slightly corrugated square net are given.

The shortest interatomic distances in the PrPd3In2 structure occur between the palladium and indium atoms. The Pd–In distances range from 271 to 284 pm, close to the sum of the covalent radii [2] for Pd+In of 278 pm. Similar ranges also occur in other indides, e.g. Ce4Pd10In21 (269–288 pm Pd–In) [30] or EuPdIn4 (265–280 pm Pd–In) [33]. All these short Pd–In distances are indicative of substantial covalent Pd–In bonding, in agreement with electronic structure calculations of structurally closely related compounds [34], [35].

Each of the three crystallographically independent palladium atoms in PrPd3In2 has at least two short Pd–Pd contacts. The Pd–Pd distances range from 283 to 316 pm. The shorter ones are close to the Pd–Pd distances of 275 pm in fcc palladium [36]. Within the PrPd3In2 structure we observe a clustering of the indium atoms into a slightly corrugated and distorted square network in form of a strand (Fig. 1, top). The In1 atoms have distorted square planar indium coordination with 2×325 pm In1–In1 and 2×332 pm In1–In2, while the In2 atoms have only two indium neighbors. Again, also the In–In distances compare well with those in elemental indium (tetragonal body-centered indium: 4×325 and 8×338 pm In–In) [36].

Keeping the courses of the interatomic distances in mind we can draw the following picture on chemical bonding in PrPd3In2. The praseodymium atoms as the least electronegative component transfer valence electrons to the palladium and indium atoms, enabling formation of the polyanionic [Pd3In2]δ− network which is primarily stabilized through strong Pd–In bonds but also through In–In and Pd–Pd bonding. This rigid network (Fig. 2) leaves the pentagonal channels that are filled by the praseodymium atoms.

![Fig. 2: The complex, three-dimensional polyanionic [Pd3In2]δ− network in the structure of PrPd3In2. Praseodymium, palladium and indium atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2019-0166/asset/graphic/j_znb-2019-0166_fig_002.jpg)

The complex, three-dimensional polyanionic [Pd3In2]δ− network in the structure of PrPd3In2. Praseodymium, palladium and indium atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively.

Now we compare the REPd3In2 compounds with the platinum-based series REPt3In2. Although platinum (129 pm) has an only slightly larger covalent radius than palladium (128 pm) [2], we observe small shifts in the lattice parameters when directly comparing the individual unit cells of REPd3In2 and REPt3In2 (Table 1). This accounts for the individual distances in Pr–Pd, Pd–Pd and Pd–In vs. Pr–Pt, Pt–Pt and Pt–In as evident from the direct comparison of the data shown in Table 5.

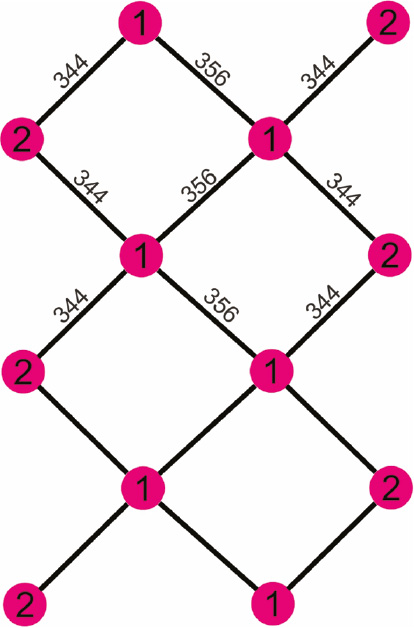

Finally we turn to the stannides REPd3Sn2 and REPt3Sn2. Already the course of the lattice parameters (Table 1) indicates severe differences with respect to the corresponding indium intermetallics. The a parameters of the stannides are drastically shorter than those of the indium compounds while the b and c parameters show the inverse behavior. This is directly related to the different extension of the tin and indium substructures. As emphasized in Fig. 1, the p-element substructure extends in bc direction. While the indium network (Fig. 1) shows closer contacts, similar to those of elemental indium, the Sn–Sn distances within the unique tin substructure (distorted square planar!; exemplarily shown for PrPt3Sn2 in Fig. 3) of 344 and 356 pm are distinctly longer than e.g. in β-Sn (4×302 and 2×318 pm Sn–Sn) [36], indicating much weaker Sn–Sn bonding. Thus, the stannide unit cells are expanded in bc direction and in order to keep the overall bonding, they are contracted in a direction. The direct comparison of the PrPd3In2 and PrPt3Sn2 interatomic distances (Table 5) shows that the weaker Sn–Sn bonding is compensated by stronger Pt–Sn bonding. The Pt–Sn distances in PrPt3Sn2 range from 264 to 284 pm, close to the sum of the covalent radii for Pt+Sn of 269 pm [2]. Keeping the differences in the lattice parameters and the chemical bonding in mind, the relationship between the indium and tin series is rather isopointal [37], [38] than isotypic.

The tin substructure of PrPt3Sn2. The crystallographically independent tin sites are shown and relevant Sn–Sn distances are indicated.

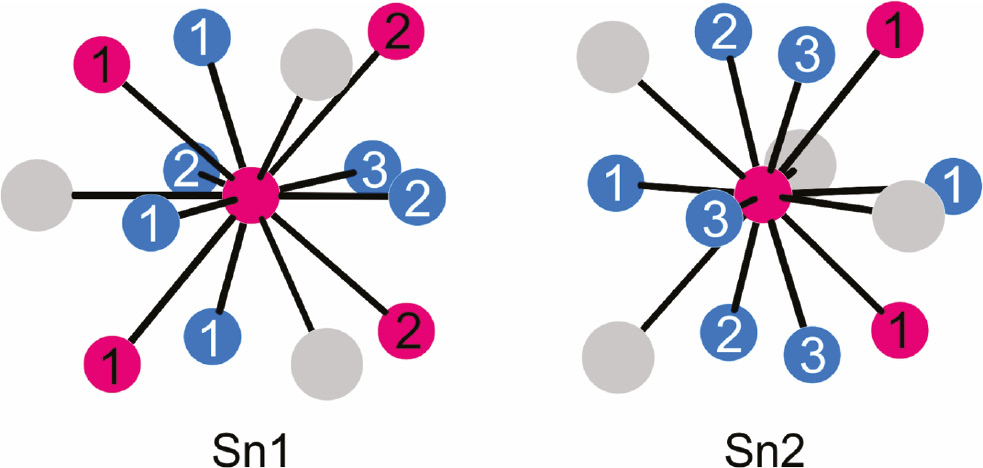

Another crystal chemical issue concerns the individual coordination of the two crystallographically independent tin sites in the REPd3Sn2 and REPt3Sn2 series, exemplarily drawn for PrPt3Sn2 in Fig. 4. Both tin sites have site symmetry 4c and coordination number 13; however, with different atoms, i.e. 6 Pt+4 Sn+3 Pr for Sn1 and 7 Pt+2 Sn+4 Pr for Sn2. This leads to small changes in the tin local electron density and is thus reflected in the 119Sn Mössbauer spectra discussed below.

Coordination of the two crystallographically independent tin sites (both with site symmetry .m.) in PrPt3Sn2. Praseodymium, platinum and tin atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. The crystallographically independent platinum and tin sites are indicated.

3.2 Physical properties

The basic magnetic properties of the compounds with nominal composition RET3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm; T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn) are summarized in Table 6. The lanthanum palladides all exhibit nearly temperature-independent Pauli-paramagnetic behavior (data not shown hear), while in the case of the corresponding platinide LaPt3In2 the intrinsic-core diamagnetism overcompensates the Pauli-paramagnetic contribution of the conduction electrons. All other investigated compounds except for CePt3In2 and SmPt3In2 exhibit paramagnetic behavior over the entire investigated temperature range. Long-range magnetic ordering for these compounds was not detected using zero-field-cooled and field-cooled (ZFC/FC) experiments above 2.5 K. The magnetic properties of CePt3In2 and SmPt3In2 will be discussed in further detail below. The basic magnetic properties of all compounds, except SmPt3In2, were obtained by fitting the experimental magnetic susceptibility data, recorded at 10 kOe, between T=50 and 300 K using the modified Curie-Weiss law. The deduced effective magnetic moments for compounds containing paramagnetic rare earth elements are in close agreement with the theoretically expected value of the free RE3+ ions and therefore pointing towards stable trivalent oxidation states. PrPd3In2 and PrPd3Sn2 show slightly enhanced effective magnetic moments (Table 6), most likely due to minor amounts of impurity phases (not visible in the Guinier patterns). Both compounds were prepared several times. The measurements with the lowest moments are reported in Table 6.

Magnetic properties of the RET3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm; T=Pd, Pt; X=In, Sn) compounds: TN, Néel temperature; μeff, effective magnetic moment; μcalc, calculated magnetic moment; θP, paramagnetic Curie temperature; μsat, experimental saturation magnetization; gJ×J, theoretical saturation magnetization.

| Compound | TN (K) | μeff (μB) | μcalc (μB) | θP (K) | μsat (μB per RE3+) | gJ×J (μB per RE3+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LaPd3In2 | χ(300 K)=+3.5(2)×10−4 emu mol−1 | |||||

| PrPd3In2 | – | 3.67(1) | 3.58 | −7.6(3) | 0.5(1) | 3.20 |

| NdPd3In2 | – | 3.59(1) | 3.62 | −17.0(5) | 1.1(1) | 3.27 |

| LaPt3In2 | χ(300 K)=−7.0(2)×10−5 emu mol−1 | |||||

| CePt3In2 | 4.0(1) | 2.48(1) | 2.54 | 0.8(5) | 1.0(1) | 2.14 |

| SmPt3In2 | 3.5(1) | 0.76(1) | 0.845 | −45(1) | 0.05(1) | 0.71 |

| LaPd3Sn2 | χ(300 K)=+6.3(2)× 10−4 emu mol−1 | |||||

| PrPd3Sn2 | – | 3.86(1) | 3.58 | −25.1(5) | 0.9(1) | 3.20 |

| NdPd3Sn2 | – | 3.55(1) | 3.62 | −11.7(5) | 1.0(1) | 3.27 |

| CePt3Sn2 | – | 2.56(1) | 2.54 | −18.0(5) | 0.9(1) | 2.14 |

| NdPt3Sn2 | – | 3.65(1) | 3.62 | −4.7(3) | 1.7(1) | 3.27 |

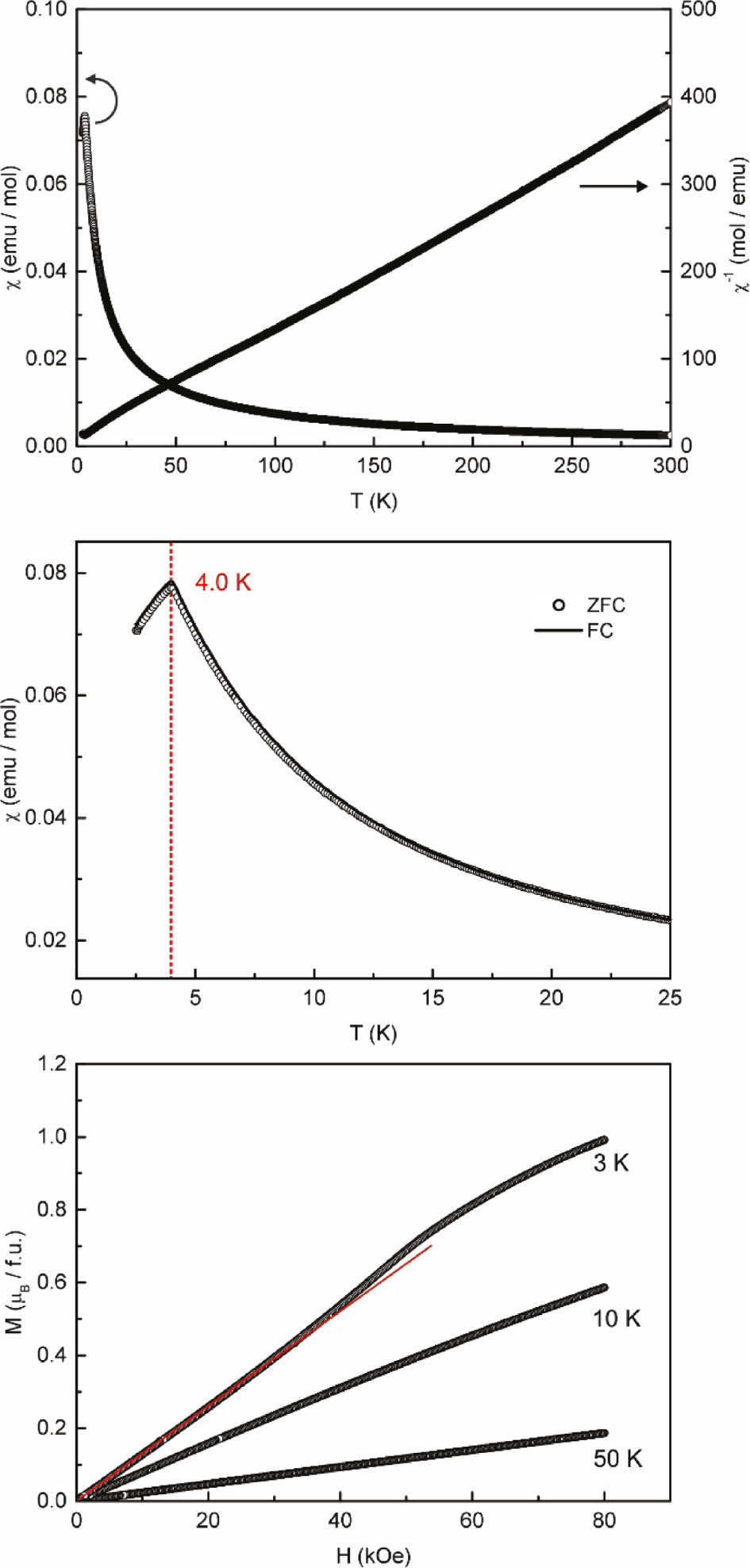

The results of the magnetic and inverse magnetic susceptibility measurements of CePt3In2, obtained at an applied external field strength of 10 kOe, are shown in Fig. 5. The effective magnetic moment per cerium atom was deduced as μeff=2.48(1) μB, close to the value expected for the free Ce3+ ion (μeff,theo=2.54 μB) indicating a stable trivalent oxidation state of the cerium atoms in CePt3In2. The paramagnetic Curie temperature of θP=0.8(5) K indicates the absence of dominant magnetic interactions in the paramagnetic range. In order to check for long-range magnetic ordering at low temperature, additional ZFC/FC experiments at an external magnetic field of 100 Oe were performed and the results are depicted in the middle of Fig. 5. CePt3In2 is ordered antiferromagnetically below TN=4.0(1) K. The magnetization isotherms recorded at T=3, 10 and 50 K, are depicted in the bottom panel of Fig. 5. While those isotherms recorded above the magnetic phase transition show a linear field dependency, the one recorded with CePt3In2 being in its antiferromagnetic ground state clearly shows a metamagnetic step (antiparallel to parallel spin alignment; emphasized by the straight red line). The high critical field strength of 47(3) kOe, determined at the inflection point, suggests a stable antiferromagnetic ground state. The saturation magnetization at 80 kOe and 3 K reaches only μsat=1.0(1) μB, significantly below the theoretical value of μsat,theo=2.14 μB, frequently observed in intermetallic cerium compounds such as CeAuSn [39] and CePtAl [40], [41].

Magnetic properties of CePt3In2: (top) temperature dependence of the magnetic and inverse magnetic susceptibility measured at 10 kOe; (middle) temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility in ZFC/FC mode (100 Oe); (bottom) isothermal magnetization recorded at T=3, 10 and 50 K. The red line acts as a guide to the eye.

The temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility and its inverse of SmPt3In2 is shown in Fig. 6. The compound exhibits the typical van Vleck paramagnetism arising from the population of excited J=7/2 states in the proximity of the J=5/2 ground state of the Sm3+ ions [42]. Hamaker et al. developed a model to fit experimentally the temperature dependent molar susceptibilities of polycrystalline, metallic samarium compounds [43]:

![Fig. 6: Magnetic properties of SmPt3In2: (top) temperature dependence of the magnetic and inverse magnetic susceptibility measured at 10 kOe. The red curve represents the fit of the experimental data using the model introduced by Hamaker et al. [43]; (middle) temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility in ZFC/FC mode at various magnetic fields; (bottom) isothermal magnetization recorded at T=3, 10 and 50 K. The inset represents an enlarged section of the low-field region at T=3 K.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2019-0166/asset/graphic/j_znb-2019-0166_fig_006.jpg)

Magnetic properties of SmPt3In2: (top) temperature dependence of the magnetic and inverse magnetic susceptibility measured at 10 kOe. The red curve represents the fit of the experimental data using the model introduced by Hamaker et al. [43]; (middle) temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility in ZFC/FC mode at various magnetic fields; (bottom) isothermal magnetization recorded at T=3, 10 and 50 K. The inset represents an enlarged section of the low-field region at T=3 K.

In this equation, NA represents the Avogadro constant, kB the Boltzmann constant, μeff the effective magnetic moment, θP the Curie temperature, and μB the Bohr magneton. The term δ corresponds to an energy scale and is defined as δ=20ΔE/7, where ΔE describes the energy difference between the ground and first excited state.

The corresponding fit of the experimental data of SmPt3In2 is shown as a solid red line in Fig. 6 (top) and results in an effective magnetic moment of μeff=0.76(1) μB which is below the expected value of μeff,calc=0.845(1) μB for the free Sm3+ ion. Nonetheless, as for the other members of the RET3X2 series, a stable trivalent oxidation state can be assumed. The negative paramagnetic Curie temperature of θP=–45(1) K points towards predominant antiferromagnetic interactions in the paramagnetic temperature range. The refined energy scale δ=515(1) K corresponds to an energy difference of ΔE=1471 K. Stewart predicted the energy difference to be at 1550 K [44]. However, in intermetallic Sm compounds like SmRh4B4 (1080 K) [43] or SmPdGa3 (1240 K) [45] lower values are often observed (in magnetochemistry the energy difference between the quantum states is usually given in units of K while spectroscopic investigations usually list them in units of cm−1).

The middle panel of Fig. 6 shows the results of ZFC/FC experiments performed at external magnetic fields of 250, 1000 and 2500 Oe, respectively. The huge bifurcation between both curves at 250 Oe suggests a ferromagnetic ground state below approximately T=8 K. However, increasing the magnetic field strength strongly reduces this effect, pointing towards an extrinsic phenomenon. The presence of a tiny ferromagnetic impurity leads to a hysteresis effect observed in a magnetization isotherm recorded at 3 K (see Fig. 6, bottom panel). The saturation magnetization of only μsat=0.05(1) μB at 3 K and an external field of 80 kOe is significantly below the expected value of μsat,calc=0.714 μB according to gJ×J, often observed in intermetallic samarium compounds. Those isotherms observed at 10 and 50 K exhibit a linear field dependence as expected for SmPt3In2 being in a paramagnetic state.

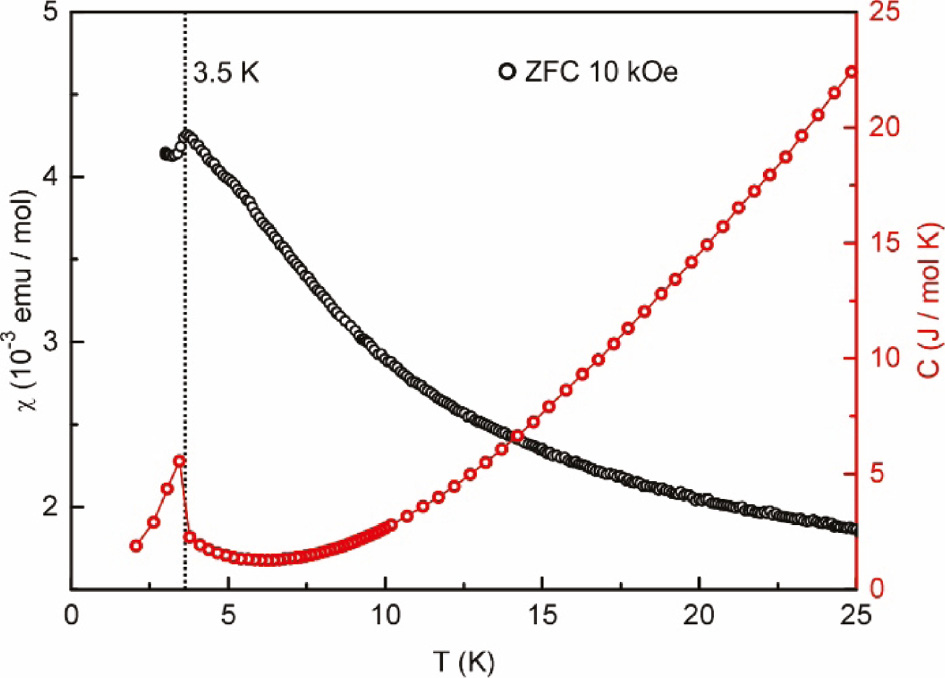

In order to prove that the observed anomaly is caused by a ferromagnetic impurity, additional heat capacity measurements were performed in zero-field and the results are depicted in Fig. 7. As expected, no heat tone is present in the corresponding temperature range excluding an intrinsic magnetic ordering. Instead, a λ-shaped anomaly appears at THC=3.4(1) K, correlating with an antiferromagnetic ordering below TN=3.5(1) K detectable in the ZFC measurement at an applied field of 10 kOe. This magnetic transition can only hardly be observed in the low-field ZFC/FC experiments due to the presence of the aforementioned magnetic impurities.

Heat capacity (red line) of SmPt3In2 measured between 2 and 25 K without an applied field and ZFC measurements at 10 kOe (black line).

3.3 Mössbauer spectroscopy

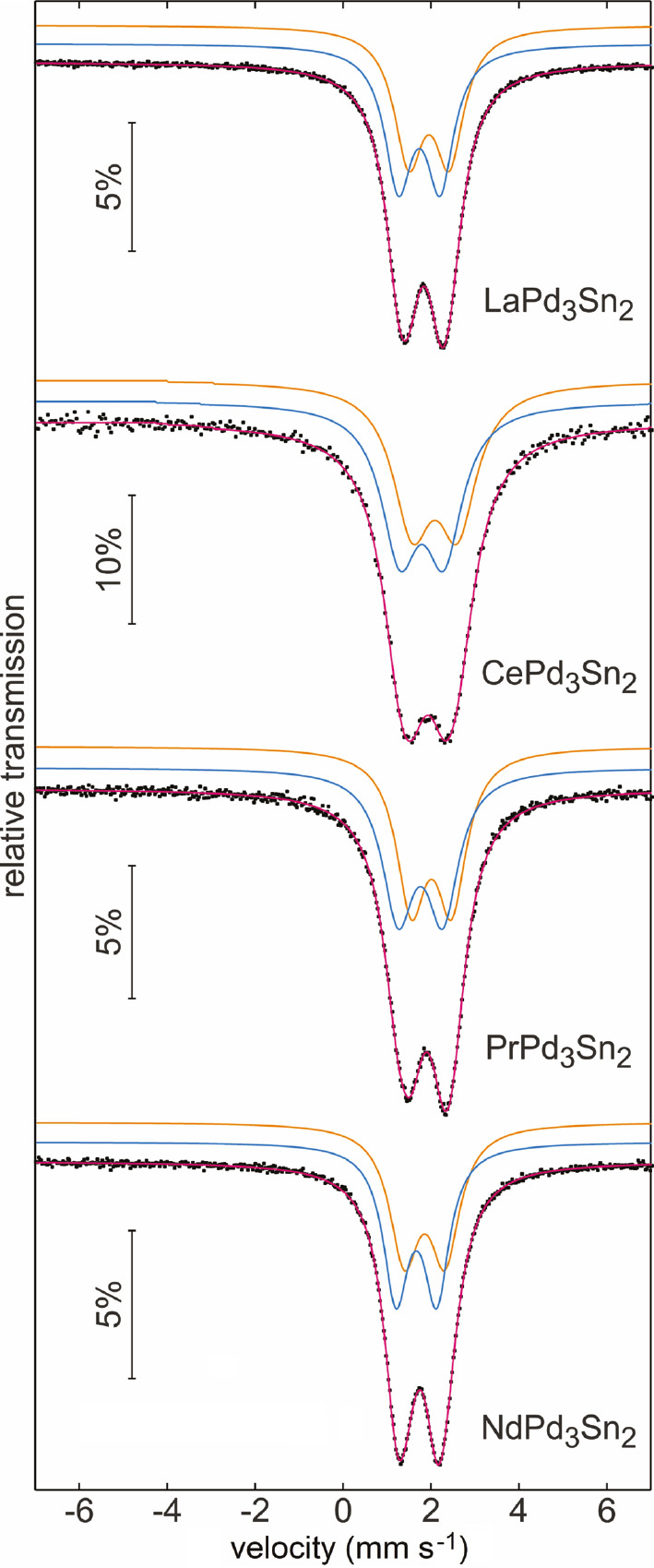

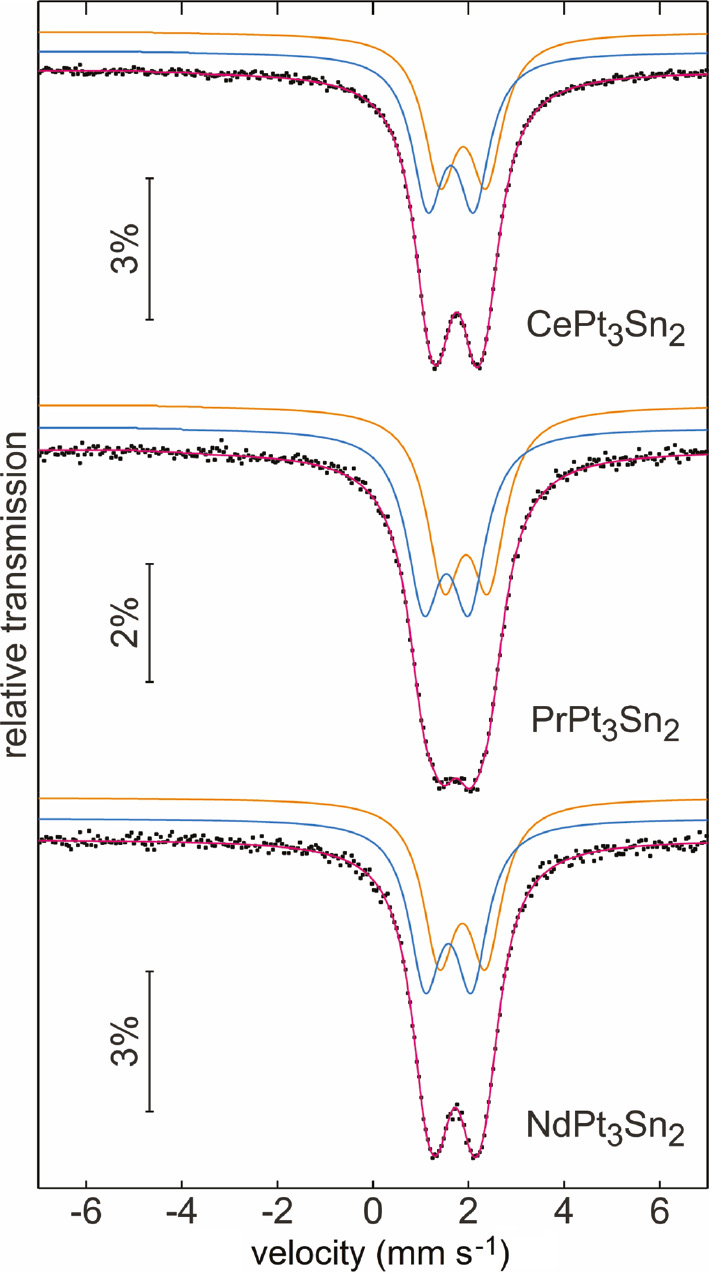

The experimental and simulated 119Sn Mössbauer spectra of the stannides REPd3Sn2 (RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd) and REPt3Sn2 (RE=Ce, Pr, Nd) are presented in Figs. 8 and 9. The corresponding fitting parameters are listed in Table 7. At first sight one may assume that all samples show simple quadrupole-split signals; however, fits with single signals resulted in too large line widths. This is a clear sign for overlapping individual sub-signals. The tin coordination has already been discussed in the crystal chemical section. Based on the two different coordination polyhedra we fitted the spectra with a 1:1 overlap of two quadrupole-split sub-spectra. It was possible to refine the data without any constraints with reasonable line width parameters. The quadrupol splitting for both sites accounts for the non-cubic site symmetry of the tin atoms. The isomer shifts are in the typical range observed for intermetallic tin compounds [16].

Experimental (data points) and simulated (colored lines) 119Sn Mössbauer spectra of the stannides REPd3Sn2 (RE=La–Nd) at room temperature.

Experimental (data points) and simulated (colored lines) 119Sn Mössbauer spectra of the stannides REPt3Sn2 (RE=Ce–Nd) at T=78 K.

Fitting parameters of 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopic measurements of REPd3Sn2 (RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd) at room temperature and REPt3Sn2 (RE=Ce, Pr, Nd) at 78 K. δ=isomer shift, ΔEQ=electric quadrupole splitting, Γ=experimental line width.

| Compound | δ (mm·s−1) | ΔEQ (mm·s−1) | Γ (mm·s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium series | |||

| LaPd3Sn2 | 1.714(2) | 0.949(2) | 0.763(4) |

| 1.936(2) | 0.922(2) | 0.810(5) | |

| CePd3Sn2 | 1.773(8) | 1.004(8) | 1.02(2) |

| 2.069(9) | 1.028(8) | 1.07(2) | |

| PrPd3Sn2 | 1.741(5) | 1.071(4) | 0.878(9) |

| 1.990(4) | 0.915(4) | 0.825(9) | |

| NdPd3Sn2 | 1.646(3) | 0.924(2) | 0.705(4) |

| 1.836(3) | 0.925(3) | 0.818(7) | |

| Platinum series | |||

| CePt3Sn2 | 1.630(4) | 0.964(4) | 0.797(8) |

| 1.888(4) | 0.965(4) | 0.827(10) | |

| PrPt3Sn2 | 1.537(4) | 0.945(6) | 0.867(12) |

| 1.950(4) | 0.927(6) | 0.870(12) | |

| NdPt3Sn2 | 1.578(6) | 0.969(6) | 0.811(13) |

| 1.873(6) | 0.970(6) | 0.829(15) | |

Although we have observed well-resolved 119Sn spectra, it is difficult to assign the two sub-signals to the two individual tin sites. In 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy, a higher isomer shift is compatible with a higher s electron density at the tin nucleus. This has nicely been demonstrated for the stannides CaTSn2 (T=Rh, Pd, Ir) [46], where the palladium compound shows the highest isomer shift, similar to the results for the series reported herein. The correct assignment of the tin sites for the series REPd3Sn2 and REPt3Sn2 deserves precise electronic structure calculations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dipl.-Ing. J. Kösters and Dr. R.-D. Hoffmann for the intensity data collections and M. Sc. F. Eustermann for the EDX analyses.

References

[1] P. Villars, K. Cenzual, Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds (release 2018/19), ASM International®, Materials Park, Ohio (USA) 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] J. Emsley, The Elements, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] C. S. Garde, J. Ray, G. Chandra, J. Alloys Compd. 1993, 198, 165.10.1016/0925-8388(93)90160-OSuche in Google Scholar

[4] M. L. Fornasini, S. Cirafici, Z. Kristallogr. 1990, 190, 295.10.1524/zkri.1990.190.3-4.295Suche in Google Scholar

[5] A. Palenzona, P. Manfrinetti, M. L. Fornasini, J. Alloys Compd. 1998, 280, 211.10.1016/S0925-8388(98)00692-6Suche in Google Scholar

[6] F. Guillou, A. K. Pathak, D. Paudyal, Y. Mudryk, F. Wilhelm, A. Rogalev, V. K. Pecharsky, Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2925.10.1038/s41467-018-05268-4Suche in Google Scholar

[7] D. Kaczorowski, P. Rogl, K. Hiebl, Phys. Rev. B1996, 54, 9891.10.1103/PhysRevB.54.9891Suche in Google Scholar

[8] F. Fourgeot, P. Gravereau, B. Chevalier, L. Fournès, J. Etourneau, J. Alloys Compd. 1996, 238, 102.10.1016/0925-8388(96)02202-5Suche in Google Scholar

[9] R. Pöttgen, J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 63.10.1039/JM9960600063Suche in Google Scholar

[10] D. T. Adroja, S. K. Malik, Phys. Rev. B1992, 45, 779.10.1103/PhysRevB.45.779Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] R. Müllmann, B. D. Mosel, H. Eckert, G. Kotzyba, R. Pöttgen, J. Solid State Chem. 1998, 137, 174.10.1006/jssc.1998.7750Suche in Google Scholar

[12] P. Lemoine, J. M. Cadogan, D. H. Ryan, M. Giovannini, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter2012, 24, 236004.10.1088/0953-8984/24/23/236004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] R. Müllmann, U. Ernet, B. D. Mosel, H. Eckert, R. K. Kremer, R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, J. Mater. Chem. 2001, 11, 1133.10.1039/b100055lSuche in Google Scholar

[14] Ya. M. Kalychak, V. I. Zaremba, R. Pöttgen, M. Lukachuk, R.-D. Hoffmann, in Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths, Vol. 34 (Eds.: K. A. Gschneidner Jr., V. K. Pecharsky, J.-C. Bünzli), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005, chapter 218, pp. 1–133.10.1016/S0168-1273(04)34001-8Suche in Google Scholar

[15] R. V. Skolozdra, in Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths (Eds.: K. A. Gschneidner, Jr., L. Eyring), Vol. 24, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1997, chapter 164, pp. 399–517.10.1016/S0168-1273(97)24009-2Suche in Google Scholar

[16] R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch. 2006, 61b, 677.10.1515/znb-2006-0607Suche in Google Scholar

[17] H. Kaldarar, E. Royanian, H. Michor, G. Hilscher, E. Bauer, A. Gribanov, D. Shtepa, P. Rogl, A. Grytsiv, Y. Seropegin, S. Nesterenko, Phys. Rev. B2009, 79, 205104.10.1103/PhysRevB.79.205104Suche in Google Scholar

[18] M. Giovannini, A. Saccone, S. Delfino, P. Rogl, Intermetallics2003, 11, 1237.10.1016/S0966-9795(03)00164-XSuche in Google Scholar

[19] M. Giovannini, A. Saccone, P. Rogl, R. Ferro, Intermetallics2003, 11, 197.10.1016/S0966-9795(02)00185-1Suche in Google Scholar

[20] S. N. Nesterenko, A. I. Tursina, P. Rogl, Y. D. Seropegin, J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 373, 220.10.1016/j.jallcom.2003.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

[21] D. V. Shtepa, S. N. Nesterenko, A. I. Tursina, E. V. Murashova, Y. D. Seropegin, Vestn. Mosk. Univ. Ser. 22008, 49, 197.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] A. M. Strydom, D. Britz, Solid State Phen. 2011, 170, 219.10.4028/www.scientific.net/SSP.170.219Suche in Google Scholar

[23] C. L. Yang, S. Tsuda, K. Umeo, T. Onimaru, W. Paschinger, G. Giester, P. Rogl, T. Takabatake, J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 739, 518.10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.323Suche in Google Scholar

[24] R. Pöttgen, Th. Gulden, A. Simon, GIT Labor-Fachzeitschrift1999, 43, 133.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] D. Niepmann, Yu. M. Prots’, R. Pöttgen, W. Jeitschko, J. Solid State Chem. 2000, 154, 329.10.1006/jssc.2000.8789Suche in Google Scholar

[26] K. Yvon, W. Jeitschko, E. Parthé, J. Appl. Crystallogr.1977, 10, 73.10.1107/S0021889877012898Suche in Google Scholar

[27] V. Petříček, M. Dušek, L. Palatinus, Z. Kristallogr.2014, 229, 345.10.1515/zkri-2014-1737Suche in Google Scholar

[28] G. J. Long, T. E. Cranshaw, G. Longworth, Moessbauer Eff. Ref. Data J.1983, 6, 42.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] R. A. Brand, WinNormosforIgor6, version for Igor 6.2 or above: 22.02.2017, Universität Duisburg, Duisburg (Germany) 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] V. I. Zaremba, U. Ch. Rodewald, Ya. M. Kalychak, Ya. V. Galadzhun, D. Kaczorowski, R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2003, 629, 434.10.1002/zaac.200390072Suche in Google Scholar

[31] V. I. Zaremba, V. P. Dubenskiy, Ya. M. Kalychak, R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, Solid State Sci. 2002, 4, 1293.10.1016/S1293-2558(02)00011-0Suche in Google Scholar

[32] U. Ch. Rodewald, B. Heying, R. Pöttgen, Z. Kristallogr. 2014, 229, 277.10.1515/zkri-2013-1714Suche in Google Scholar

[33] R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, V. I. Zaremba, Ya. M. Kalychak, Z. Naturforsch. 2000, 55b, 834.10.1515/znb-2000-0907Suche in Google Scholar

[34] R.-D. Hoffmann, U. Ch. Rodewald, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch. 1999, 54b, 38.10.1515/znb-1999-0110Suche in Google Scholar

[35] R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, Chem. Eur. J. 2000, 6, 600.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(20000218)6:4<600::AID-CHEM600>3.0.CO;2-9Suche in Google Scholar

[36] J. Donohue, The Structures of the Elements, Wiley, New York, 1974.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] E. Parthé, L. M. Gelato, Acta Crystallogr. 1984, A40, 169.10.1107/S0108767384000416Suche in Google Scholar

[38] L. M. Gelato, E. Parthé, J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1987, 20, 139.10.1107/S0021889887086965Suche in Google Scholar

[39] D. Niepmann, R. Pöttgen, K. M. Poduska, F. J. DiSalvo, H. Trill, B. D. Mosel, Z. Naturforsch.2001, 56b, 1.10.1515/znb-2001-0102Suche in Google Scholar

[40] H. Kitazawa, S. Nimori, J. Tang, F. Iga, A. Dönni, T. Matsumoto, G. Kido, Phys. B1997, 237–238, 212.10.1016/S0921-4526(97)00104-XSuche in Google Scholar

[41] M. Eilers-Rethwisch, O. Niehaus, O. Janka, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.2014, 640, 153.10.1002/zaac.201300485Suche in Google Scholar

[42] J. H. van Vleck, The Theory of Electric and Magnetic Susceptibilities, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1932.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] H. C. Hamaker, L. D. Woolf, H. B. MacKay, Z. Fisk, M. B. Maple, Solid State Commun.1979, 32, 289.10.1016/0038-1098(79)90949-9Suche in Google Scholar

[44] A. M. Stewart, Phys. Rev. B1972, 6, 1985.10.1103/PhysRevB.6.1985Suche in Google Scholar

[45] S. Seidel, O. Niehaus, S. F. Matar, O. Janka, B. Gerke, U. Ch. Rodewald, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch. 2014, 69b, 1105.10.5560/znb.2014-4119Suche in Google Scholar

[46] R.-D. Hoffmann, D. Kußmann, U. Ch. Rodewald, R. Pöttgen, C. Rosenhahn, B. D. Mosel, Z. Naturforsch. 1999, 54b, 709.10.1515/znb-1999-0602Suche in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Research Articles

- Electron densities of two cyclononapeptides from invariom application

- Crystal structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Pixel energy calculations of three trifluoromethylquinoline derivatives: further analyses of fluorine close contacts in trifluoromethylated derivatives

- Synthesis and antifungal activities of 3-substituted phthalide derivatives

- Unexpected isolation of a cyclohexenone derivative

- Preparation and structure of 4-(dimethylamino)thiopivalophenone – intermolecular interactions in the crystal

- A new binuclear NiII complex with tetrafluorophthalate and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic properties

- Two mononuclear zinc(II) complexes constructed by two types of phenoxyacetic acid ligands: syntheses, crystal structures and fluorescence properties

- Investigation of the reactivity of 4-amino-5-hydrazineyl-4H-1,2, 4-triazole-3-thiol towards some selected carbonyl compounds: synthesis of novel triazolotriazine-, triazolotetrazine-, and triazolopthalazine derivatives

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a Ni(II) coordination polymer with a tripodal 4-imidazolyl-functional ligand

- Crystal structure and photocatalytic degradation properties of a new two-dimensional zinc coordination polymer based on 4,4ʹ-oxy-bis(benzoic acid)

- Intermetallics of the types REPd3X2 and REPt3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; X=In, Sn) with substructures featuring tin and In atoms in distorted square-planar coordination

- A 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic characterization of the diamagnetic birefringence material Sn2B5O9Cl

- Synthesis, crystal structure and photoluminescence of the salts Cation+ [M(caffeine)Cl]− with Cation+=NnBu4+, AsPh4+ and M==Zn(II), Pt(II)

- Synthesis and characterization of two bifunctional pyrazole-phosphonic acid ligands

- A β-ketoiminato palladium(II) complex for palladium deposition

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, XCVIa. Push-pull-substituierte 1,3,5-Hexatriene aus Orthoamiden von Alkincarbonsäuren und Birckenbach-analogen Acetophenonen

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, IIICa. Weitere Ergebnisse bei der Umsetzung von Orthoamiden der Alkincarbonsäuren mit CH2- und CH2/NH-aciden Verbindungen

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Research Articles

- Electron densities of two cyclononapeptides from invariom application

- Crystal structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Pixel energy calculations of three trifluoromethylquinoline derivatives: further analyses of fluorine close contacts in trifluoromethylated derivatives

- Synthesis and antifungal activities of 3-substituted phthalide derivatives

- Unexpected isolation of a cyclohexenone derivative

- Preparation and structure of 4-(dimethylamino)thiopivalophenone – intermolecular interactions in the crystal

- A new binuclear NiII complex with tetrafluorophthalate and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic properties

- Two mononuclear zinc(II) complexes constructed by two types of phenoxyacetic acid ligands: syntheses, crystal structures and fluorescence properties

- Investigation of the reactivity of 4-amino-5-hydrazineyl-4H-1,2, 4-triazole-3-thiol towards some selected carbonyl compounds: synthesis of novel triazolotriazine-, triazolotetrazine-, and triazolopthalazine derivatives

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a Ni(II) coordination polymer with a tripodal 4-imidazolyl-functional ligand

- Crystal structure and photocatalytic degradation properties of a new two-dimensional zinc coordination polymer based on 4,4ʹ-oxy-bis(benzoic acid)

- Intermetallics of the types REPd3X2 and REPt3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; X=In, Sn) with substructures featuring tin and In atoms in distorted square-planar coordination

- A 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic characterization of the diamagnetic birefringence material Sn2B5O9Cl

- Synthesis, crystal structure and photoluminescence of the salts Cation+ [M(caffeine)Cl]− with Cation+=NnBu4+, AsPh4+ and M==Zn(II), Pt(II)

- Synthesis and characterization of two bifunctional pyrazole-phosphonic acid ligands

- A β-ketoiminato palladium(II) complex for palladium deposition

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, XCVIa. Push-pull-substituierte 1,3,5-Hexatriene aus Orthoamiden von Alkincarbonsäuren und Birckenbach-analogen Acetophenonen

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, IIICa. Weitere Ergebnisse bei der Umsetzung von Orthoamiden der Alkincarbonsäuren mit CH2- und CH2/NH-aciden Verbindungen