Abstract

The crystal structure of diamagnetic borate chloride Sn2B5O9Cl exhibits two crystallographically independent tin sites which both show pronounced lone-pair activity of the tin atoms. This is reflected in substantial quadrupole splitting in the 119Sn Mössbauer spectrum. The isomer shifts of 3.887(8) and 4.137(7) mm s−1 clearly indicate divalent tin. In agreement with bond valence calculations, the Sn1 atoms have a lower charge and the higher isomer shift, compatible with a higher electron density at the tin nuclei.

1 Introduction

119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy is an excellent tool for the study of tin oxidation states and for analyses of the local electronic structures and the chemical bonding peculiarities of solids. The important experimental parameters are the isomer shift, relating variations of the electron density at the tin nuclei and the electric quadrupole splitting, monitoring the deformation of the electron density. The most prominent examples are the tin oxides SnIIO (SnO4 square pyramids and hence a pronounced stereochemical lone-pair activity) and SnIVO2 (slightly distorted SnO6 octahedra). The lower valence of the tin atom and the anisotropy of the coordination sphere of SnO lead to an isomer shift around 2.7 mm s−1 and substantial quadrupole splitting of 1.4 mm s−1. SnO2 samples show an isomer shift around 0 mm s−1, similar to that of the usually used Ca119mSnO3 or Ba119mSnO3 sources, and the only slight distortion of the octahedra induces a much weaker quadrupole splitting of 0.5 mm s−1. These values have repeatedly been reported for diverse SnO and SnO2 samples [1], [2], [3], [4].

Thus, divalent and tetravalent tin in solids can safely be distinguished on the basis of 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic data. Nevertheless, also within a family of SnII and SnIV compounds, small variations of the local electron density and the tin coordination environment can be monitored. This has competently been summarized for a large number of tin chalcogenides by Lippens [2] and for a huge number of organotin compounds by Zuckerman [5].

Especially the SnII compounds show peculiar behavior. To give an example, while SnO with its SnO4 square pyramids shows pronounced quadrupole splitting, SnTe with the rocksalt structure shows no quadrupole splitting at all [6], [7], [8]. The gradual change of the quadrupole splitting parameter from SnO to SnTe and the particular isomer shift of the oxide have been studied by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy by Lefebvre et al. [8] and were discussed on the basis of DFT calculations.

The quadrupole splitting parameters (ΔEQ) of SnII compounds cover a much broader range than observed for the SnO4 square pyramids in SnO. Our recent studies on the arene-stabilized monocation [SnII{N(SiMe3)(Ar)}]+ [Al(OC4F9)4]− [9] revealed ΔEQ=3.69 mm s−1. Many organotin carboxylates [5] show even values >4 mm s−1.

We have now probed the resolution of 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy with respect to SnII borates. β-SnB4O7 [10] contains one crystallographically independent tin site which shows an isomer shift of 4.14 mm s−1. The SnO10 polyhedron shows a distortion, accounting for the lone pair effect. This leads to a weak quadrupole splitting parameter of 0.78 mm s−1. Herein we report on the 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic characterization of the recently reported borate chloride Sn2B5O9Cl [11], which contains two different SnO7Cl2 polyhedra, favorable to enhance the optical performance via cation substitution [12].

2 Experimental

2.1 Sample synthesis and characterization

Polycrystalline Sn2B5O9Cl was obtained from a standard solid state reaction at high temperature using SnO, SnCl2, B2O3 and H3BO3 (all supplied from Aladdin with purities better than 99%) following the original work [11]. The solids were mixed in the ideal stoichiometric ratio, ground to a fine powder and sealed in an evacuated silica ampoule. The mixture was first heated at T=473 K for 10 h and then to 723 K and kept at that temperature for another 2 weeks. The underlying reaction is SnO+SnCl2+2 B2O3+H3BO3→→Sn2B5O9Cl+HCl+H2O.

The powder sample was characterized by X-ray diffraction using a Guinier camera (equipped with an imaging plate detector, coupled with a Fuji film BAS-1800 readout system) and CuKα1 radiation with α-quartz (a=491.30 and c=540.46 pm) as an internal standard. The experimental pattern was compared to a calculated one [13] and the lattice parameters [a=1126.5(6), b=1132.5(7), c=657.0(3) pm, V=0.8382 nm3] were deduced from a least-squares fit. They are in good agreement with the single crystal data [a=1128.1(3), b=1133.1(3), c=655.73(19) pm, V=0.8382 nm3] [11]. SnO2 was detected as by-product. The Guinier pattern revealed the Bragg peaks of SnO2 besides a broader bump, originating from amorphous SnO2. Similar behaviour has been observed for nanoparticles and hollow spheres of tin dioxide [14].

2.2 Physical property studies

Part of the polycrystalline Sn2B5O9Cl sample was packed in a polyethylene (PE) capsule and attached to the sample holder rod of a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer unit (VSM) for measuring the magnetization M(T,H) in a Quantum Design Physical-Property-Measurement-System (PPMS). The sample was investigated in the temperature range between 2.5 and 300 K and with an applied magnetic field of 10 kOe (1 kOe=7.96×104 A m−1).

2.3 Mössbauer spectroscopy

A Ca119mSnO3 source was used for the 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic investigation. Source, sample and detector were placed in the usual transmission geometry. A palladium foil of 0.05 mm thickness was used to reduce the tin K X-rays concurrently emitted by this source. The ideal absorber thickness was calculated according to the work of Long et al. [15]. The sample was placed in a thin-walled PMMA container inside an Argon-filled glovebox to prevent sample decomposition. The container was sealed with a two component epoxide glue. The measurement (4 days counting time) was conducted at room temperature. The spectrum was fitted with the WinNormos for Igor6 program package [16].

3 Crystal chemistry

Sn2B5O9Cl [11] crystallizes with the non-centrosymmetric Ca2B5O9Br-type structure [17], space group Pnn2. The borate substructure consists of the fundamental building unit (FBU) [B5O12]9−, a condensation of three BO4 tetrahedra and two BO3 triangles. For a detailed crystal chemical discussion of the many isotypic compounds we refer to the relevant original work [11], [17], [18], [19]. Herein we redraw only to the coordination of the tin cations that is relevant for the interpretation of the 119Sn Mössbauer spectra.

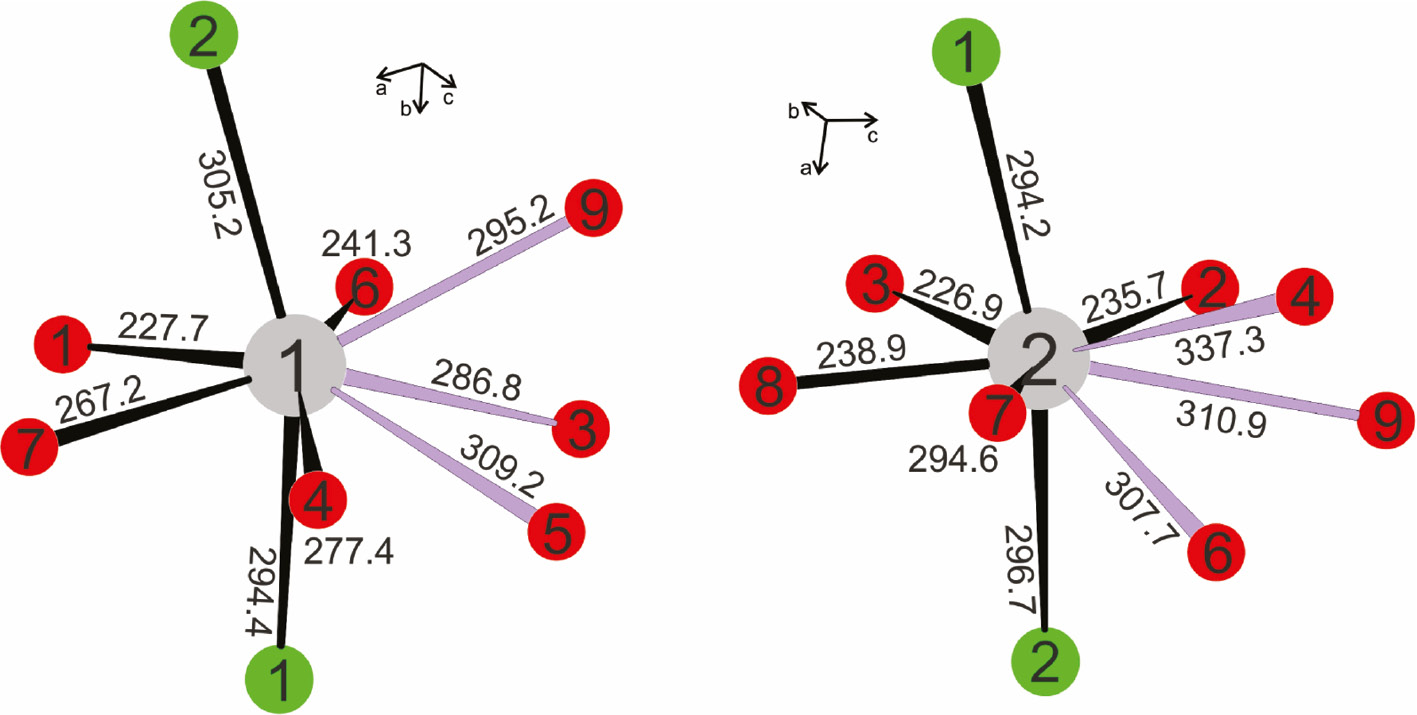

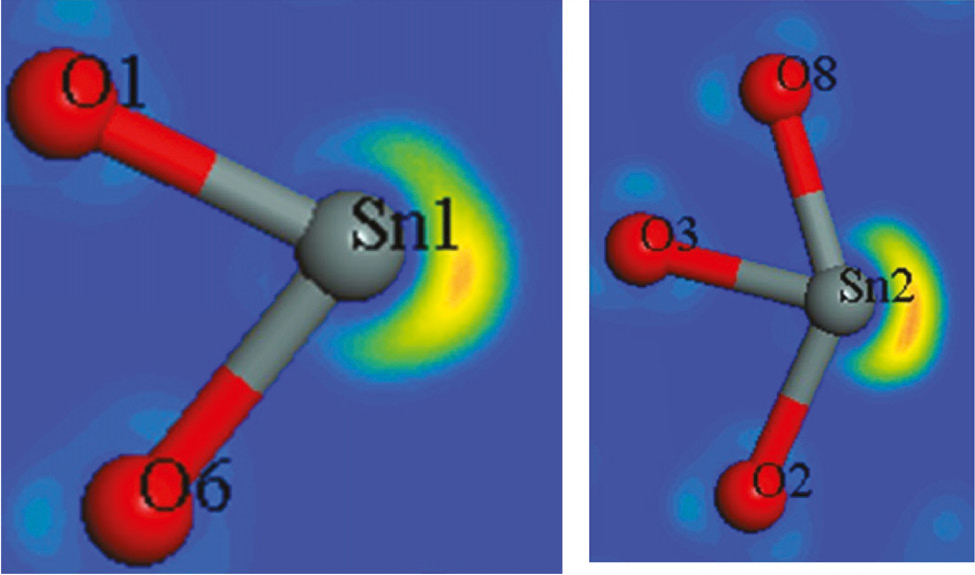

The Sn2B5O9Cl structure contains two crystallographically independent tin sites which both have site symmetry 1. The coordination environment of both tin sites is shown in Fig. 1. The distances to the seven nearest oxygen neighbors of each tin cation cover a broad range: 227.7–309.2 pm for Sn1 and 226.9–337.3 pm for Sn2. Three of the seven oxygen neighbors at each tin site show distinctly longer Sn–O distances. These bonds are drawn in violet color in Fig. 1. This coordination asymmetry is in line with the lone-pair activity and approximately corresponds with the cutouts presented in Fig. 2 resulting from the electron localization function (ELF) by the first principles calculations (for details see [11]). We draw back to this asymmetry when discussing the quadruple splitting parameters (vide infra).

The coordination environment of the tin atoms in Sn2B5O9Cl. Tin, oxygen and chlorine atoms are drawn as light grey, red and green circles, respectively. Atom designations and bond distances are given. For details see text.

Cutouts of the tin coordination spheres in Sn2B5O9Cl. The lone pairs around the Sn1 and Sn2 ions in Sn2B5O9Cl are visualized by the electron localization function (ELF).

The pronounced lone-pair character is also expressed in the lattice parameters. The A2B5O9Cl chloride series exist for A=Ca, Sr, Ba, Eu, Pb [19] and Sn. Of all chlorides, Sn2B5O9Cl has the largest c lattice parameters, even larger than that of Pb2B5O9Cl. This is consistent with the longer Sn–O distances emphasized in Fig. 1. Their resultant, and consequently the lone pairs, point in c direction.

The local electron density at the tin nuclei is the second important parameter. In Table 1 we present bond valence sums for Sn2B5O9Cl calculated with the bond length/bond strength (ΣV) [20], [21] and Chardi concepts (ΣQ) [22], [23]. The computed charges show good agreement with the ideal model; however, both calculations consistently show a distinctly lower charge for the Sn1 cations.

Charge distribution in Sn2B5O9Cl calculated with the Bond-Length/Bond-Strength concept (ƩV) [20], [21] (top) and the Chardi concept (ƩQ) [22], [23] (bottom).

| Sn1 | Sn2 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | O1 | O2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ƩV | 1.67 | 1.87 | 3.17 | 2.98 | 3.17 | 3.12 | 3.06 | −2.44 | −1.96 |

| ƩQ | 1.66 | 2.09 | 3.28 | 2.60 | 3.15 | 2.92 | 3.21 | −2.02 | −1.89 |

| O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | O7 | O8 | O9 | Cl1 | Cl2 | |

| ƩV | −1.91 | −1.79 | −1.93 | −1.83 | −1.54 | −2.20 | −1.87 | −0.95 | −0.80 |

| ƩQ | −2.11 | −1.98 | −1.84 | −2.06 | −2.13 | −1.93 | −1.97 | −1.08 | −1.07 |

4 Magnetic properties

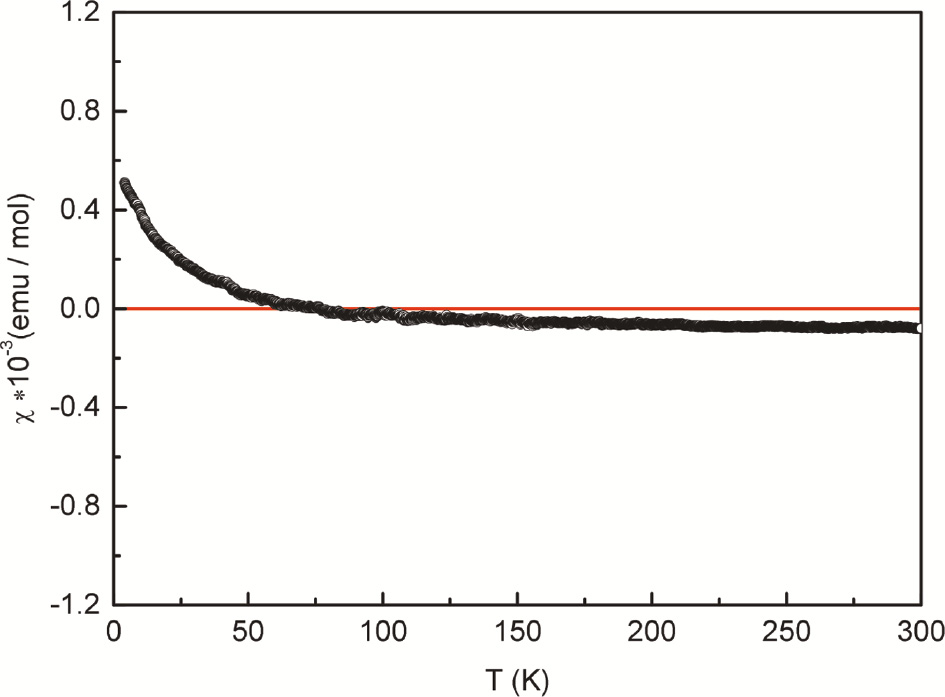

The temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility, determined at an applied external field of 10 kOe is presented in Fig. 3. The susceptibility is negative and almost independent of temperature above ca. 150 K, indicating diamagnetism. The upturn in the low temperature regime results from tiny amounts of paramagnetic impurities (Curie tail). The room temperature value of −80×10−6 emu mol−1 is in the same order of magnitude as the sum of the diamagnetic increments of (in units of 10−6 emu mol−1) 2×−20 for Sn2+, 5×−0.2 for B3+, 9×−12 for O2− and −23.4 for Cl−, resulting in a value of −172.4×10−6 emu mol−1 [24]. The smaller experimental value is attributed to (i) the by-product SnO2 which is a weaker diamagnet (the sum of the diamagnetic increments is only −44×10−6 emu mol−1) and (ii) minor paramagnetic impurities.

Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility of the Sn2B5O9Cl sample measured at 10 kOe. The red line serves as a guideline to the eye.

5 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy

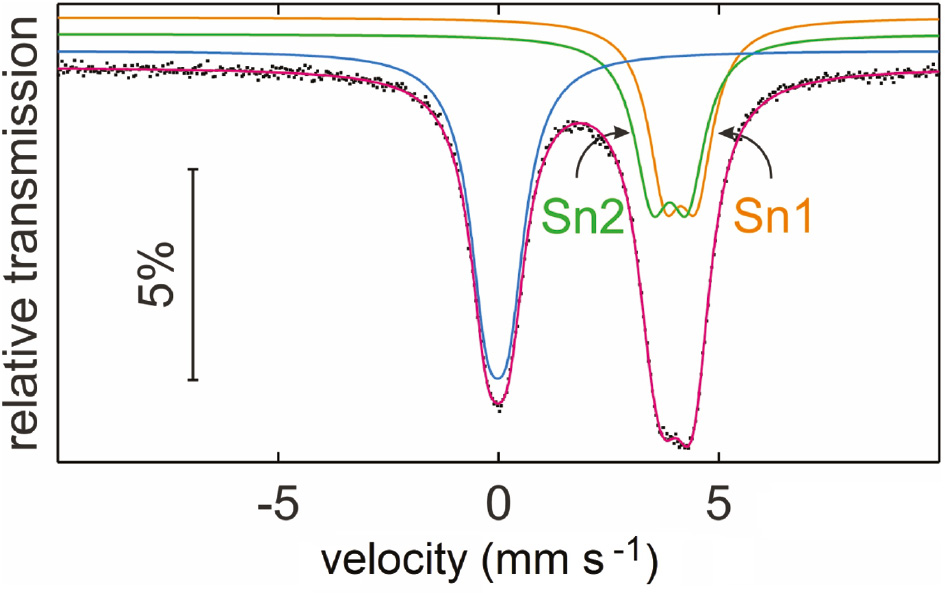

The experimental and simulated 119Sn Mössbauer spectrum of the Sn2B5O9Cl sample is presented in Fig. 4 along with a transmission integral fit. The corresponding fitting parameters are summarized in Table 2. The total counting time of 4 days led to a well-resolved spectrum and all parameters could be refined independently without any constraint. The spectrum shows two main signals. The one at −0.020 mm s−1 corresponds to the by-product SnO2, which occured in the products of all synthesis attempts [11]. The weak quadrupole splitting parameter of this sub-signal results from the slightly distorted octahedral coordination in rutile-type SnO2. Both, the isomer shift and the quadrupole splitting parameter are in good agreement with literature data [2], [4], [25]. The slightly broadened line can be attributed to the amorphous SnO2 content, as also observed for SnO2 nanoparticles [14], [26].

Experimental (data points) and simulated (colored lines) 119Sn Mössbauer spectrum of a Sn2B5O9Cl sample at room temperature. The sub-signal emphasized with a blue line corresponds to the by-product SnO2.

Fitting parameters of the 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic measurement of the Sn2B5O9Cl sample at room temperature.

| δ (mm·s−1) | ΔEQ (mm·s−1) | Γ (mm·s−1) | Ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnO2 (by-product) | −0.020(2) | 0.487(6) | 0.965(8) | 42(1) |

| Sn2B5O9Cl | 3.887(8) | 0.804(7) | 0.967(12) | 29(1) |

| 4.137(7) | 0.707(7) | 0.916(14) | 29(1) |

δ=Isomer shift; ΔEQ=electric quadrupole splitting; Γ=experimental line width.

The second sub-signal occurs at a higher isomer shift. This spectral contribution is much broader than the SnO2 signal and was well reproduced with a superposition of two quadrupole split signals (with fixed 1:1 contribution) at isomer shifts of 3.887(8) and 4.137(7) mm s−1, clearly indicating divalent tin. These isomer shifts lie in between the values for SnO (2.7 mm s−1) and SnCl2 (4.1 mm s−1) [2]. In 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy, an increase of the isomer shift goes along with an increasing s electron density at the tin nuclei [2]. Thus, on the basis of the bond valence calculations (vide ultra), we can clearly assign the tin sub-spectra to the individual tin sites. The Sn1 atoms with the lower calculated charge has the higher isomer shift. In view of the low site symmetry and the similar distortions, both tin sites show very similar quadrupole splitting parameters.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 51972336

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61835014

Funding statement: S. Pan thanks for support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51972336 and 61835014).

References

[1] I. A. Courtney, R. A. Dunlap, J. R. Dahn, Electrochim. Acta1999, 45, 51.10.1016/S0013-4686(99)00192-9Search in Google Scholar

[2] P. E. Lippens, Phys. Rev. B1999, 60, 4576.10.1103/PhysRevB.60.4576Search in Google Scholar

[3] J. Chouvin, J. Oliver-Fourcade, J. C. Jumas, B. Simon, Ph. Biensan, F. J. Fernández Madrigal, J. L. Tirado, C. Pérez Vicente, J. Electroanal. Chem.2000, 494, 136.10.1016/S0022-0728(00)00357-0Search in Google Scholar

[4] T. Baidya, P. Bera, O. Krocher, O. Safonova, P. M. Abdala, B. Gerke, R. Pöttgen, K. R. Priolkar, T. K. Mondal, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.2016, 18, 13974.10.1039/C6CP01525ESearch in Google Scholar

[5] J. J. Zuckerman, in Advances in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 9 (Eds.: F. G. A. Stone, R. West), Academic Press, New York, 1970, pp. 21–134.10.1016/S0065-3055(08)60050-7Search in Google Scholar

[6] F. Ledda, C. Muntoni, S. Serci, L. Pellerito, Chem. Phys. Lett.1987, 134, 545.10.1016/0009-2614(87)87190-7Search in Google Scholar

[7] G. Concas, T. M. De Pascale, L. Garbato, F. Ledda, F. Meloni, A. Rucci, M. Serra, J. Phys. Chem. Solids1992, 53, 791.10.1016/0022-3697(92)90191-FSearch in Google Scholar

[8] I. Lefebvre, M. A. Szymanski, J. Olivier-Fourcade, J. C. Jumas, Phys. Rev. B1998, 58, 1896.10.1103/PhysRevB.58.1896Search in Google Scholar

[9] J. Li, C. Schenk, F. Winter, H. Scherer, N. Trapp, A. Higelin, S. Keller, R. Pöttgen, I. Krossing, C. Jones, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2012, 51, 9557.10.1002/anie.201204601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] J. S. Knyrim, F. M. Schappacher, R. Pöttgen, J. Schmedt auf der Günne, D. Johrendt, H. Huppertz, Chem. Mater.2007, 19, 254.10.1021/cm061946wSearch in Google Scholar

[11] J. Guo, A. Tudi, S. Han, Z. Yang, S. Pan, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2019, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201911187.10.1002/anie.201911187Search in Google Scholar

[12] X. Dong, Q. Jing, Y. Shi, Z. Yang, S. Pan, K. R. Poeppelmeier, J. Young, J. M. Rondinelli, J. Am. Chem. Soc.2015, 137, 9417.10.1021/jacs.5b05406Search in Google Scholar

[13] K. Yvon, W. Jeitschko, E. Parthé, J. Appl. Crystallogr.1977, 10, 73.10.1107/S0021889877012898Search in Google Scholar

[14] S. Indris, M. Scheuermann, S. M. Becker, V. Šepelák, R. Kruk, J. Suffner, F. Gyger, C. Feldmann, A. S. Ulrich, H. Hahn, J. Phys. Chem. C2011, 115, 6433.10.1021/jp200651mSearch in Google Scholar

[15] G. J. Long, T. E. Cranshaw, G. Longworth, Moessbauer Eff. Ref. Data J.1983, 6, 42.Search in Google Scholar

[16] R. A. Brand, WinNormosforIgor6, version for Igor 6.2 or above: 22.02.2017, Universität Duisburg, Duisburg (Germany) 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[17] D. J. Lloyd, A. Levasseur, C. Fouassier, J. Solid State Chem.1973, 6, 179.10.1016/0022-4596(73)90179-5Search in Google Scholar

[18] O. V. Yakubovich, N. N. Mochenova, O. V. Dimitrova, W. Massa, Acta Crystallogr.2004, E60, i127.10.1107/S1600536804023232Search in Google Scholar

[19] C. Fouassier, A. Levasseur, P. Hagenmuller, J. Solid State Chem.1971, 3, 206.10.1016/0022-4596(71)90029-6Search in Google Scholar

[20] I. D. Brown, D. Altermatt, Acta Crystallogr.1985, B41, 244.10.1107/S0108768185002063Search in Google Scholar

[21] N. E. Brese, M. O’Keeffe, Acta Crystallogr.1991, B47, 192.10.1107/S0108768190011041Search in Google Scholar

[22] R. Hoppe, S. Voigt, H. Glaum, J. Kissel, H. P. Müller, K. Bernet, J. Less-Common Met.1989, 156, 105.10.1016/0022-5088(89)90411-6Search in Google Scholar

[23] M. Nespolo, B. Guillot, J. Appl. Crystallogr.2016, 49, 317.10.1107/S1600576715024814Search in Google Scholar

[24] G. A. Bain, J. F. Berry, J. Chem. Educ.2008, 85, 532.10.1021/ed085p532Search in Google Scholar

[25] P. A. Flinn, in Mössbauer Isomer Shifts (Eds.: G. K. Shenoy, F. E. Wagner), North-Holland Publishing, Amsterdam, 1978, Chapter 9a, pp. 593–616.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Y. S. Avadhut, J. Weber, E. Hammarberg, C. Feldmann, I. Schellenberg, R. Pöttgen, J. Schmedt auf der Günne, Chem. Mater.2011, 23, 1526.10.1021/cm103286tSearch in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Research Articles

- Electron densities of two cyclononapeptides from invariom application

- Crystal structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Pixel energy calculations of three trifluoromethylquinoline derivatives: further analyses of fluorine close contacts in trifluoromethylated derivatives

- Synthesis and antifungal activities of 3-substituted phthalide derivatives

- Unexpected isolation of a cyclohexenone derivative

- Preparation and structure of 4-(dimethylamino)thiopivalophenone – intermolecular interactions in the crystal

- A new binuclear NiII complex with tetrafluorophthalate and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic properties

- Two mononuclear zinc(II) complexes constructed by two types of phenoxyacetic acid ligands: syntheses, crystal structures and fluorescence properties

- Investigation of the reactivity of 4-amino-5-hydrazineyl-4H-1,2, 4-triazole-3-thiol towards some selected carbonyl compounds: synthesis of novel triazolotriazine-, triazolotetrazine-, and triazolopthalazine derivatives

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a Ni(II) coordination polymer with a tripodal 4-imidazolyl-functional ligand

- Crystal structure and photocatalytic degradation properties of a new two-dimensional zinc coordination polymer based on 4,4ʹ-oxy-bis(benzoic acid)

- Intermetallics of the types REPd3X2 and REPt3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; X=In, Sn) with substructures featuring tin and In atoms in distorted square-planar coordination

- A 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic characterization of the diamagnetic birefringence material Sn2B5O9Cl

- Synthesis, crystal structure and photoluminescence of the salts Cation+ [M(caffeine)Cl]− with Cation+=NnBu4+, AsPh4+ and M==Zn(II), Pt(II)

- Synthesis and characterization of two bifunctional pyrazole-phosphonic acid ligands

- A β-ketoiminato palladium(II) complex for palladium deposition

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, XCVIa. Push-pull-substituierte 1,3,5-Hexatriene aus Orthoamiden von Alkincarbonsäuren und Birckenbach-analogen Acetophenonen

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, IIICa. Weitere Ergebnisse bei der Umsetzung von Orthoamiden der Alkincarbonsäuren mit CH2- und CH2/NH-aciden Verbindungen

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Research Articles

- Electron densities of two cyclononapeptides from invariom application

- Crystal structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis and Pixel energy calculations of three trifluoromethylquinoline derivatives: further analyses of fluorine close contacts in trifluoromethylated derivatives

- Synthesis and antifungal activities of 3-substituted phthalide derivatives

- Unexpected isolation of a cyclohexenone derivative

- Preparation and structure of 4-(dimethylamino)thiopivalophenone – intermolecular interactions in the crystal

- A new binuclear NiII complex with tetrafluorophthalate and 2,2′-bipyridine ligands: synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic properties

- Two mononuclear zinc(II) complexes constructed by two types of phenoxyacetic acid ligands: syntheses, crystal structures and fluorescence properties

- Investigation of the reactivity of 4-amino-5-hydrazineyl-4H-1,2, 4-triazole-3-thiol towards some selected carbonyl compounds: synthesis of novel triazolotriazine-, triazolotetrazine-, and triazolopthalazine derivatives

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a Ni(II) coordination polymer with a tripodal 4-imidazolyl-functional ligand

- Crystal structure and photocatalytic degradation properties of a new two-dimensional zinc coordination polymer based on 4,4ʹ-oxy-bis(benzoic acid)

- Intermetallics of the types REPd3X2 and REPt3X2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb; X=In, Sn) with substructures featuring tin and In atoms in distorted square-planar coordination

- A 119Sn Mössbauer-spectroscopic characterization of the diamagnetic birefringence material Sn2B5O9Cl

- Synthesis, crystal structure and photoluminescence of the salts Cation+ [M(caffeine)Cl]− with Cation+=NnBu4+, AsPh4+ and M==Zn(II), Pt(II)

- Synthesis and characterization of two bifunctional pyrazole-phosphonic acid ligands

- A β-ketoiminato palladium(II) complex for palladium deposition

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, XCVIa. Push-pull-substituierte 1,3,5-Hexatriene aus Orthoamiden von Alkincarbonsäuren und Birckenbach-analogen Acetophenonen

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, IIICa. Weitere Ergebnisse bei der Umsetzung von Orthoamiden der Alkincarbonsäuren mit CH2- und CH2/NH-aciden Verbindungen