Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

-

Zineb Ben Khadda

and Raquel P. F. Guiné

Abstract

The purpose of the current study is to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected eating behavior and directed toward organic food and bioproducts consumption in the North African region especially Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia as well as identify the variables that may affect the eating behavior of these population. Data were collected using an anonymous online survey on 1,244 respondents from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The results showed that the confinement did influence the consumption of healthy food to enhance people’s immune system so as to prevent infection by the COVID-19, and other diseases. Moreover, academic level, gender, and country of residence were diversely correlated with the eating behavior during COVID-19 confinement. The understanding of people’s eating behavior will help the public health to reshape future policies toward organic and bio-based food production; moreover, some further nutritional recommendations could be concluded to maintain a global better health status and improve body defence mechanism.

1 Introduction

The worldwide spread of the 2019 coronavirus disease, known as COVID-19 during late 2019 and 2020, and the resulted lockdowns, caused an unprecedented change in the population’s lifestyles. As a consequence, a lot of people were led to work/study from home, in an inexperienced social isolation. Hence, their eating habits may change. In Italy, a survey has shown that Italians adhered to the Mediterranean diet as a response to the lockdown [1]. Eating habits change was also reported in the Zimbabwe population, which tended to consume more vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables (57% of the questioned people) [2]. Moreover, another study in Ecuador showed that quarantine during COVID-19 has generated many changes in adults eating habits and sleep quality, in the same study researchers mentioned that women and young adults were the most affected by those changes [3]. Similarly, in the Peru, changes in eating behavior were recorded and almost 68% of adults participated in an online survey reported a significant variation in their weight, while 40% of the population reported a weight gain. These changes were mainly associated to the physical inactivity, unhealthy eating habits, and stress caused by the quarantine situation [4]. The results of a narrative synthesis analyzing the preliminary effects of the quarantined lifestyle from the point of view of eating habits revealed a sharp increase in the consumption of carbohydrate sources, fruits, vegetables and protein sources, in particular legumes [5]. In addition, an increase in tea consumption has clearly been recorded [6]. Other reports of eating habits’ changes during COVID-19 pandemic can be checked elsewhere [7].

Besides, food producers suffered from huge losses in the perishable food sector due to changes in customers’ consumption patterns, as a result to lifestyle disruptions and psychological stress during the quarantine. Hence, the food production and distribution patterns along the supply chain were influenced [8]. Recently, in response to awareness campaigns by the media about the effect of pesticides and chemical fertilizers on health, environment, and food safety, consumers start to be more vigilant about food origins and show interest in organic food [9,10].

Organic foods are produced according to methods and substrates respecting the ecological balance of natural systems, without chemical fertilizers, pesticides, growth hormones, or antibiotics or any intervention of bioengineering and genetic modification [11]. The crop protection techniques rely on preventive measures, biological control, physical control allied to green interventions, and soil managements measures [12]. Plant products from organic farming may contain very high polyphenol, vitamin C, and antioxidants amounts [10]. Those compounds are known to have anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, cardioprotective, immunomodulatory, vasodilatory, and analgesic properties. Also, organic food consumption may decrease the risk of allergic diseases and obesity [10,13,14]. Hence, organic farming aims to produce healthy food and create an ecological balance to reduce the difficulties linked to pests and soil fertility [15]. Generally, organic food have more benefits than conventionally grown ones, and more importantly with no detectable toxic chemical residues [16]. Organic food allied to a healthy diet may ensure good health and play an important role in successfully managing and overcoming health crises like the severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [17,18].

By the January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as the sixth public health emergency of international concern [19]. This pandemic has spread exponentially all over the world, with more than 208 million COVID-19 confirmed cases and 4 million deaths reported globally (numbers updated on August 18, 2021) [20]. According to Gasmi et al. [21] and Jayawardena and Misra [18], diet and nutrition are essential to the good functioning of the immune system. Hence an imbalanced diet with a lack of physical activity will cause many health problems mainly obesity and heart and respiratory problems, recently an Italian survey revealed that obese patients even younger ones brought to emergency for COVID-19-related pneumonia needed more ventilation than normal weight people or the access to intensive care units [21]. Despite the awareness of the importance of organic products, and their increased consumption on the global scale, the data concerning the different aspects of organic products consumption as well as people’s food attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic are very limited and not fully understood. To our knowledge, no study has discussed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on attitudes toward organic product consumption. In this context, the present study aims to assess the consumption level of organic products in three North African countries (Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), as well as to determine the effect of COVID-19 on the consumption attitudes toward these products.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data collection

Data collection was carried out through an assisted web-based survey using google forms, launched on June 21, 2020 on social networks (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, LinkedIn, etc.). The questionnaire was pre-tested on a small number of participants, and then it was validated by some expert researchers. After that it was shared through the different social networks aforementioned, and the population was targeted through the different platforms on the different North African countries. The survey questions were done based on previous studies, to highlight the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organic food consumption; mainly in three North African countries namely Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (Figure 1). These countries were selected because of their agricultural status and their shared history, geographic situation as well as their appreciation of bio-based products.

The main area of the study.

“Organic food” was used widely in this survey, and respondents refer to the term in their understanding, which differ from an academic perspective, or even industrial definition. However, the term was already recognized in the area. Hence, a question/statement was made at the beginning of the survey to understand the term as chemical-free food, natural, GMO-free, issued from biological agriculture and healthy products.

2.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire was composed of 28 questions in total, which were divided into three main parts: the first aimed the collection of information about the respondents, through seven questions concerning nationality, place of residence, age, gender, academic level, family situation, and profession. The questions in the second part (15 questions) were mainly around organic products, started with a question concerning the eating habits in general: “What do you think about your eating habits? with four possible rethinks; healthy, bad, incomplete, not sure,” and the number of meals consumed per day. Besides, the consumption frequency of organic products was evaluated using the following scale: always, often, sometimes, rarely, never. The type of products consumed (all types of products, fruits and vegetables, dairy products, cosmetics, etc.), as well as questions concerning the reasons that encourage their organic purchases (organic products are good for my health, organic products have a good quality, environment respect, traceability, and monitoring of products, the price reflects the quality of the product, conventional products contain residues of pesticide(s), etc.), or limits to consumption (unavailability or the difficulty to find these organic products, organic product is indifferent to other products, ignorance of organic products, the price, the taste, etc.), all in the form of multiple choice questions associated with a Likert scale (totally agree, tend to agree, tend to disagree, totally disagree etc.). The third part of questionnaire included questions designed to determine the effect of the COVID-19 health crisis on biological products’ consumption, for example: “Since the COVID-19 health crisis, have your eating behavior changed? yes, no,” “In light of the COVID-19 health crisis, your consumption of organic products has increased, decreased, indifferent.” These questions were designed to understand the reasons for the decrease (access to organic products remains minimal, unavailability in the market, restriction of movement, other(s)) or the increase in the consumption (the awareness of the healthy diets’ importance to overcome health crises, the greater chance of finding organic products easier than conventional ones, development of online commerce, proximity to places/markets where organic is frequent, etc.).

2.3 Data analysis

The collected data were coded, entered, and verified to eliminate the risk of error, only participants over the age of 18 years of North Africa countries were selected, and then the SPSS 20 software was used to calculate the relative frequencies and frequencies of the responses. Canonical analysis of the correspondences was carried out using the PAST 3 software to know more genuinely the relationship between the socio-demographic variables of respondents (age, educational level, family situation, etc.) and the eating habits toward organic products.

3 Results

3.1 Sample characterization

A total of 1,244 respondents took part in this survey, including 805 women and 439 men. The full demographic breakdown is shown in Table 1.

Demographic profile of the respondents

| Total respondents | Women (%) | Men (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 64.7 | 35.3 | 100 | |

| Nationality | |||

| Moroccan | 60.6 | 39.4 | 71.71 |

| Algerian | 74.2 | 25.8 | 15.92 |

| Tunisian | 80.7 | 19.3 | 7.07 |

| Other | 69.7 | 30.3 | 5.3 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 66.3 | 33.7 | 88.8 |

| Rural | 51.8 | 48.2 | 11.2 |

| Age | |||

| 15–25 years old | 71.7 | 28.3 | 65.6 |

| 26–40 years old | 52.7 | 47.3 | 30.5 |

| 41–50 years old | 45.5 | 54.5 | 2.6 |

| 51–60 years old | 28.6 | 71.4 | 0.6 |

| Over 60 years old | 37.5 | 62.5 | 0.7 |

| Family situation | |||

| Single | 65.2 | 34.8 | 83.5 |

| Married but without children | 62.9 | 37.1 | 5 |

| Married with children | 60.5 | 39.5 | 10 |

| Divorced | 87.5 | 12.5 | 0.6 |

| Other | 63.6 | 36.4 | 0.9 |

| Academic level | |||

| Illiterate | 50 | 50 | 0.2 |

| Primary | 0 | 100 | 0.2 |

| Secondary | 64.5 | 35.5 | 3.6 |

| University | 64.9 | 35.1 | 96 |

| Profession | |||

| No occupation | 76.5 | 23.5 | 6.5 |

| Pupil, student | 69.5 | 30.5 | 61.2 |

| Employee | 55.3 | 44.7 | 26.4 |

| Retirement | 42.9 | 57.1 | 0.6 |

| Farmer | 33.3 | 66.7 | 0.7 |

| Other | 45.6 | 54.4 | 4.6 |

The major participation recorded was of Moroccans with a percentage of 71, followed by Algerians (15.92%) and Tunisians (7.07%). The most represented age categories were 15–25 and 26–40 years, with percentages of 65.6 and 30.5, respectively. This reflects that the majority of participants were young people. Regarding the level of education, a large portion of 96% had a university level, 3.6% had a high school education, and only 0.4% had no academic training or had a primary level. Most of the respondents were single (83.5%) and 10% were married and had children. Students were dominant in this study with a percentage of 61.2, while 26.4% were employees, 6.5% were unemployed, and 2.6% were working in agriculture or retired (1.3% each).

3.2 Status of organic food consumption in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia

Out of the 1,244 participants, 53.8% were aware that their eating habits are incomplete and only less than 5% declared that they had bad habits. Fast food was consumed rarely or sometimes by almost 90% of the respondents and only 1.6% of them had fast food every day. Half of the population included in this survey had three meals a day, while 26% had four meals a day. Around 2.2 and 2.3%, respectively, of the questioned populations had one or five meals a day. Regarding the knowledge about organic compounds, a critical question in the present work, 91%, confirmed that they have heard about them at least once, 85.6% of which were aware of the importance of organic food and almost all respondents were aware of the relationship between the immune system and nutrition. Organic products were consumed sometimes by 42.2%, often by 28.7%, and never by 5.1% of the interrogated population. Nevertheless, almost all the respondents are wishing to increase their organic food consumption rate. The answer to the question “how many people around you consumes organic products?” was 1 to 3 people by 17.6% of respondents, 3 to 5 people by 9.7%, while 7.4% knew more than 9 people (Table 2).

Level of consumption of organic products by respondents

| Questions | Answer | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| What do you think about your eating habits? | Healthy | 29.8 |

| Bad | 4.4 | |

| Incomplete | 53.8 | |

| Not sure | 12 | |

| Do you eat fast meals daily? | Always | 1.5 |

| Often | 9.1 | |

| Sometimes | 39.9 | |

| Rarely | 42.2 | |

| Never | 7.3 | |

| How many meals do you take per day? | One meal | 2.2 |

| Two meals | 16.8 | |

| Three meals | 51.8 | |

| Four meals | 26.1 | |

| Five meals | 2.3 | |

| Other | 0.8 | |

| Have you ever heard of organic products? | Yes | 91.9 |

| No | 8.1 | |

| Are you aware of the importance of organic food? | Yes | 85.6 |

| No | 14.4 | |

| In your opinion, is there a relationship between nutrition and the immune system? | Yes | 99.7 |

| No | 0.3 | |

| Do you consume organic products? | Always | 6.1 |

| Often | 28.7 | |

| Sometimes | 42.2 | |

| Rarely | 17.9 | |

| Never | 5.1 | |

| How many people around you consume organic? | I do not know | 55.7 |

| Nobody | 3.6 | |

| From 1–3 people | 17.6 | |

| From 3–5 people | 9.7 | |

| From 5–7 people | 4.4 | |

| From 7–9 people | 1.7 | |

| More than 9 people | 7.3 | |

| Is there such a person(s) who practice organic farming around you? | Yes | 37 |

| No | 63 | |

| Would you like to increase your consumption of organic products? | Yes | 95.4 |

| No | 4.6 |

According to respondents in our study, organic purchases were governed by many criteria; the higher price and the non-availability of organic products were the main criteria that have a negative impact with almost 55% of respondents who tend to agree or totally agree. Concerning the criteria that have a positive impact on organic purchases, there were four main ones in the following order: (1) the great benefits for health, (2) the high quality of organic products, (3) the environment respect, and finally (4) the fact that they are pesticides free, respectively, with percentages of 66.2, 47.2, 43.6, and 37.9 of respondents who totally agree (Table 3).

Criteria influencing organic food purchase

| Totally disagree (%) | Tend to disagree (%) | Neutral (%) | Tend to agree (%) | Totally agree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? | |||||

| The non-availability of organic products | 13.8 | 18 | 13.6 | 29.9 | 24.7 |

| Indifference from other products | 63.3 | 19.3 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 4.4 |

| Lack of knowledge of organic in general | 41 | 20.4 | 16.2 | 14.8 | 7.6 |

| The price | 16.8 | 15 | 15.8 | 22.3 | 30.1 |

| Taste | 37.5 | 16.6 | 20.3 | 16.6 | 9 |

| For what reason(s) or criteria do you consume or prefer organic product? | |||||

| Organic products are good for health | 5.3 | 7 | 8.7 | 12.8 | 66.2 |

| Organic products have good quality | 5.4 | 8.8 | 13.4 | 25.2 | 47.2 |

| The respect of environment | 6.7 | 8.4 | 18.9 | 22.4 | 43.6 |

| Product traceability and monitoring | 12.3 | 14.5 | 29.7 | 20.3 | 23.2 |

| The price reflects the quality | 20.4 | 22.4 | 25.3 | 17.7 | 14.2 |

| Conventional products contain pesticide residues | 13.3 | 13.1 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 37.9 |

3.3 COVID-19 effect on organic product consumption

Almost all the participants were not affected by the SARS CoV-2. Faced with this pandemic, only 7.6% have followed a specific or particular diet; however, 62.4% declared that their eating behavior has changed since the health crisis started. During the quarantine, the number of meals a day as well as the consumption of organic products did change for 59.9 and 57%, respondents, respectively. Finally, according to almost half of them, the demand for natural products will be increased after confinement (Table 4).

Eating behavior during the COVID-19 health crisis

| Questions | Answers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever had COVID-19 disease? | Yes | 1 |

| No | 99 | |

| If yes, did you follow a specific or particular diet? | Yes | 7.6 |

| No | 92.4 | |

| Since the COVID-19 health crisis, did our eating habits really changed? | Yes | 62.4 |

| No | 37.6 | |

| During confinement, did the number of your daily meals… | Increase | 24.6 |

| Decrease | 15.9 | |

| Indifferent | 59.5 | |

| In light of the COVID-19 health crisis, did your consumption of organic products… | Increase | 25.3 |

| Decrease | 17.7 | |

| Indifferent | 57 | |

| In your opinion, after the quarantine the demand for natural (organic) products will be… | Increased | 51.9 |

| Decreased | 4.7 | |

| Indifferent | 43.3 |

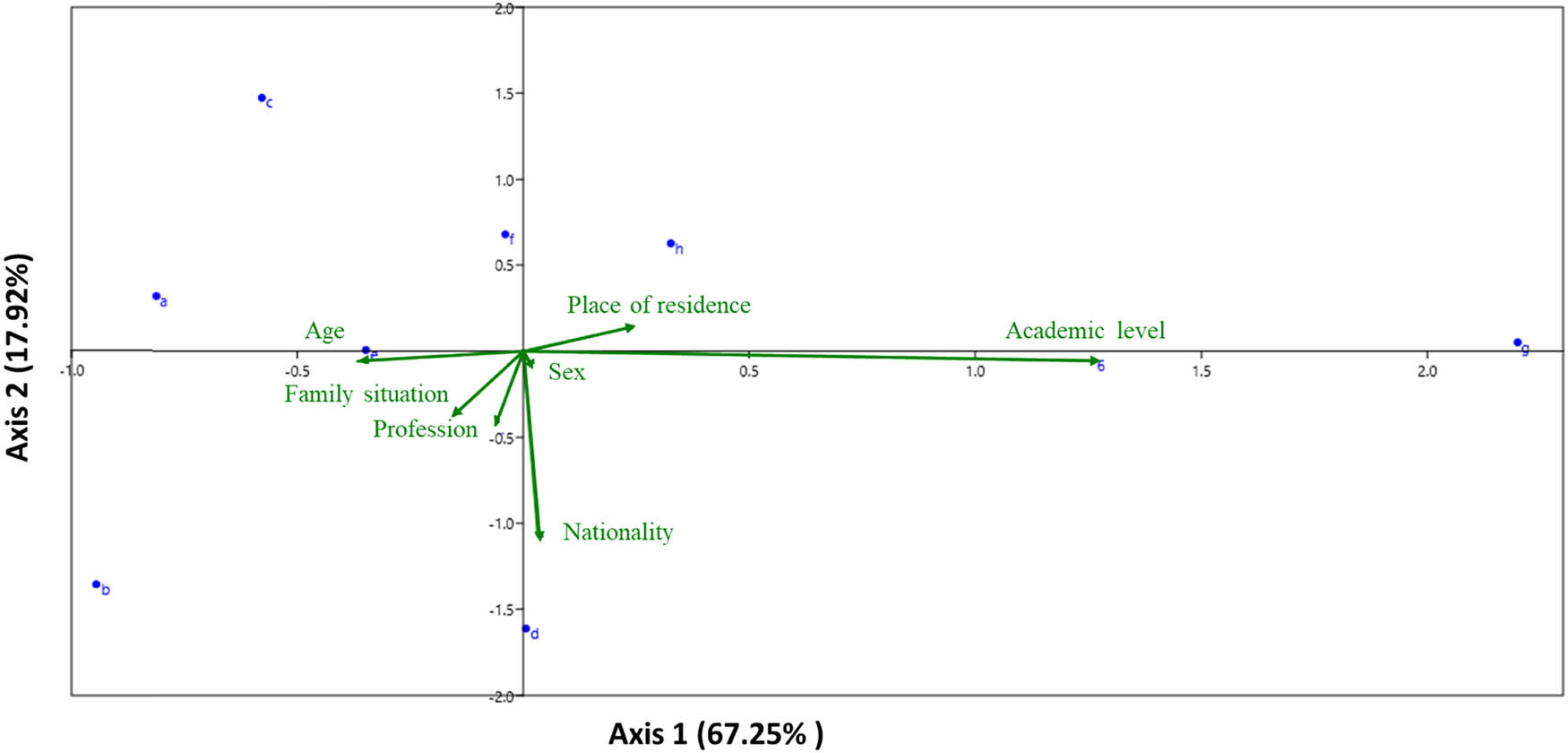

The relationship between eating behavior during the COVID-19 health crisis and personal socio-economic characteristics is illustrated in Figure 2. The first canonical axis accounts for approximately 67.25% of the variation in this relationship and the first two represent approximately 85.17%. The four variables (nationality, place of residence, age, and academic level) were also correlated with eating behavior during this crisis. The opposite meanings of the arrows for age and academic level in Figure 2 indicate that these two factors have opposing influences on eating behavior during confinement. The other variables are not correlated with the coverage behavior of personal protective equipment and do not vary the percentage of explanations on the canonical axis.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) representing the impact of COVID-19 on the consumption of organic products. (a) Have you ever had the COVID-19 disease? (b) Since the COVID-19 health crisis, has our eating behavior really changed? (c) During quarantine, has the number of your daily meals changed? (d) In light of the COVID-19 health crisis, does your consumption of organic products have increased or decreased? (e) In your opinion, after quarantine, the demand for natural products (organic) will be high or low? (f) Do you think that organic food is part of our future? (g) How many meals do you eat per day? (h) Have you ever heard of organic products?.

3.4 Multivariate analysis

The canonical correlation resuming the factors of organic products’ use is illustrated in Figure 3. The first two canonical axes, explaining 52.87 and 22.19% of data variability, were used to generate the plot shown in Figure 3. The variables of personal demographic characteristics are represented by the green arrows. The length of the arrows indicates the relative contribution of the variables to the axes and the relationship between the consumption of organic products and personal characteristics. Nationality, place of residence (urban/rural), gender, and academic level were correlated with the consumption of organic products.

![Figure 3

CCA representing the reasons that encourage/discourage the consumption of organic products. (a) Do you consume organic products? (b) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [The unavailability in your entourage or the difficulty to find these organic products]. (c) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [The organic product is indifferent compared to other products]. (d) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [Lack of knowledge of organic products in general]. (e) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [The price]. (f) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [Taste]. (g) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [The taste]. (h) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because organic products are good for my health]. (i) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because organic products have a good quality]. (j) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [For the respect of the environment]. (k) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [For product traceability and tracking]. (l) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because the price reflects the quality of the product]. (m) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because conventional products contain pesticide residue(s)].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2022-0064/asset/graphic/j_opag-2022-0064_fig_003.jpg)

CCA representing the reasons that encourage/discourage the consumption of organic products. (a) Do you consume organic products? (b) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [The unavailability in your entourage or the difficulty to find these organic products]. (c) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [The organic product is indifferent compared to other products]. (d) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [Lack of knowledge of organic products in general]. (e) What are the criteria that slow down your organic purchases? [The price]. (f) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [Taste]. (g) What are the criteria that hold back your organic purchases? [The taste]. (h) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because organic products are good for my health]. (i) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because organic products have a good quality]. (j) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [For the respect of the environment]. (k) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [For product traceability and tracking]. (l) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because the price reflects the quality of the product]. (m) For what reason(s) or criterion(s) do you consume or prefer organic products? [Because conventional products contain pesticide residue(s)].

4 Discussion

The COVID-19 disease caused by the SARS CoV-2 has been spreading exponentially around the world. According to the WHO in August 18, 2021 in the African continent, the number of confirmed cases was 5,360,548 and 128,201 deaths. However, in our study area, there have been 772,394 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 11,242 deaths in Morocco; 187,968 confirmed cases with 4,830 deaths in Algeria; and 626,750 confirmed cases with 21,926 deaths in Tunisia [20].

During the confinement, nutrition, diet, and physical activity have widely changed, which lead the WHO to indicate that a healthy diet and nutrition can help in the treatment and prevention of the disease [7]. There is a close relationship between food and health, so that the acquisition of good eating habits and essentially organic food influence positively the health status and decrease the predisposition to diseases such as diabetes, obesity or cardiovascular diseases [7,23]. In the present study, we tried to investigate the changes that occurred during the pandemic and in the period of confinement in three North African countries (Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia).

Focusing on organic product consumption, 53% of our respondents were having unbalanced eating habits, only 29% think that their eating habits were healthy. Besides, only 10.6% were having the consumption of fast food as a habit, while 48.2% think that the number of meals per day was unstable and varied between 1 to 5 meals a day. Moreover, the majority of the respondents were aware of organic food importance to health, 99.7% think that the consumption of organic food helps the immune system and empowers the body to fight diseases; however, only 6.1% were able to consume these products in a daily basis while the rest responded that they consume organic food frequently. The WHO has published a recommendation for healthy food consumption based on fruits and vegetables during the self-quarantine or long homestays, as the best diet for health and best strategy to fight COVID-19 [24]. Interestingly, the North African region is known by the availability of agricultural products especially Morocco and Tunisia which have an agriculture-based economy. During the pandemic, these countries have guaranteed the low price and accessibility for all products. The low consumption of fast food was directly linked to the absence of restaurants which has encouraged home cooking, and played a major role reducing the incidence of chronic diseases [7,25]. Furthermore, the change in eating habits during the pandemic was linked to several factors such as stress and anxiety. Unfortunately, the unhealthy lifestyle and sedentary effect influenced heavily the health and empowered cardiovascular disease, which made the population vulnerable to SARS CoV-2 infection [26].

The canonical correlation of the biological products’ consumption illustrated in Figure 2 showed that nationality, place of residence, gender, and academic level were correlated with the consumption of organic products, this is explained by the fact that the majority of respondents have a great knowledge about organic food, the majority know biological products as a product without the intervention of chemicals and fertilizers, so the choice of products was based on their knowledge. However, the arrows for nationality and place of residence suggest that these two variables have a negative impact on the consumption of organic products by the respondents which could be explained that in rural regions the availability of bioproducts is higher than in urban regions, which means that small farmers produce their own vegetables and products without the use of pesticide and chemical fertilizers. Several studies showed that the motives behind organic food consumption was because of the concerns about health, desires for supporting the local economy, the environment, food safety, and animal welfare [27].

The canonical analysis of the variation in the relationship between eating behavior, COVID-19 health crisis, and personal socio-economic characteristics relationship was represented in Figure 3. The nationality and place of residence were correlated with eating behavior during this crisis. Emilien and Hollis reported that several factors have profoundly affected eating behavior, such as environmental, cultural, including physiology, emotional, social, economic, and access pressures [28]. The age and academic level have not affected eating behavior during the pandemic; however, this behavior was influenced by food accessibility or the types of available food which was noted by the geographical factor.

During the pandemic, the knowledge generated so as to fight the COVID-19 has emerged significantly, and with the absence of proper treatment people tried to change their food consumption toward a healthy one, as a preventive way of improving their immunity. This was clear when the respondents who were infected with the virus have changed their consumption behavior to organic food and increased their number of meals per day.

The study revealed the changes in consumption patterns of organic food during the pandemic, in three North African countries, which are linked historically and share the same ideology and culture. However, some limitations were presented during the survey which should be fixed in further studies. As the research data were collected using a web platform, the respondents were indirectly biased according to their academic level and access to internet. The region studied has a big majority of people that could not use computers or connect to the internet, and they do not have any idea about organic food and its importance to health. Hence, future studies should focus on these aspects and attempt to reach those segments of the population as well.

5 Conclusion

To summarize, this work provides the first description of how the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has changed the eating behavior to fight the SARS CoV-2, in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. These changes have an impact on health, due to the quarantine and the media influence. People have improved their eating habits toward organic and biobased products knowing that healthy food may improve their immunity which is the main weapon to fight this disease. Furthermore, organic consumption was clearly influenced first by nationality and place of residence, then by the gender and academic level, which clearly had an impact on the respondents’ choices. However, for the consumption behavior during the confinement, all the factors studied were influential.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CERNAS Research Centre and the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu for their support.

-

Funding information: The work was funded by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., through CERNAS Research Centre, within the scope of the project Ref UIDB/00681/2020.

-

Author contributions: Z.B., N.R., S.E., A.B. – conceptualization; Z.B., S.E., N.R., H.L., Z.E. – data curation; S.E., A.Z., H.L. – formal analysis; R.G., Y.E., Z.E. – funding acquisition; Y.E., L.E., T.H.S. – methodology; Z.B., N.R., S.E., Y.E. – resources; Z.B., N.R., S.E., H.L., A.B. – writing: original draft; R.G., Y.E., N.R. – writing: review and editing – supervision: R.G., L.E., T.H.S.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Scarmozzino F, Visioli F. Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown modified dietary habits of almost half the population in an Italian sample. Foods. 2020;9(5):675.10.3390/foods9050675Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Matsungo TM, Chopera P. Effect of the COVID-19-induced lockdown on nutrition, health and lifestyle patterns among adults in Zimbabwe. BMJ Nutr Prev Heal. 2020;3(2):205–12. 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000124. Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Ramos-Padilla P, Villavicencio-Barriga VD, Cárdenas-Quintana H, Abril-Merizalde L, Solís-Manzano A, Carpio-Arias TV. Eating habits and sleep quality during the covid-19 pandemic in adult population of Ecuador. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3606.10.3390/ijerph18073606Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Agurto HS, Alcantara-Diaz AL, Espinet-Coll E, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ. Eating habits, lifestyle behaviors and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine among Peruvian adults. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11431.10.7717/peerj.11431Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Zupo R, Castellana F, Sardone R, Sila A, Giagulli VA, Triggiani V, et al. Preliminary trajectories in dietary behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a public health call to action to face obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. 2020;17:7073.10.3390/ijerph17197073Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Castellana F, De Nucci S, De Pergola G, Di Chito M, Lisco G, Triggiani V, et al. Trends in coffee and tea consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Foods. 2021;10:2458.10.3390/foods10102458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Ruiz-Roso MB, de Carvalho Padilha P, Mantilla-Escalante DC, Ulloa N, Brun P, Acevedo-Correa D, et al. Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1807.10.3390/nu12061807Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Aldaco R, Hoehn D, Laso J, Margallo M, Ruiz-Salmón J, Cristobal J, et al. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci Total Environ. 2020;742:140524.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140524Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Hughner RS, McDonagh P, Prothero A, Shultz CJ, Stanton J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J Consum Behav. 2007;6(2–3):1–17.10.1002/cb.210Search in Google Scholar

[10] Popa ME, Mitelut AC, Popa EE, Stan A, Popa VI. Organic foods contribution to nutritional quality and value. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;84:15–8.10.1016/j.tifs.2018.01.003Search in Google Scholar

[11] Olson EL. The rationalization and persistence of organic food beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. J Clean Prod. 2017;140:1007–13.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.005Search in Google Scholar

[12] Guiné RP, Gaião D, Costa DV, Correia PM, Guerra LT, Correia HE, et al. Bridges between family farming and organic farming: a study case of the Iberian Peninsula. Open Agric. 2019;4(1):727–36.10.1515/opag-2019-0073Search in Google Scholar

[13] Balsano C, Alisi A. Antioxidant effects of natural bioactive compounds. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(26):3063–73.10.2174/138161209789058084Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Oczkowski M. Health-promoting effects of bioactive compounds in blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) Berries. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2021;72(3):229–38.10.32394/rpzh.2021.0174Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] FAO. Organic agriculture: what are the environmental benefits of organic agriculture? https://www.fao.org/organicag/oa-faq/oa-faq6/en/ (accessed February 6, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

[16] Bertrand C, Lesturgeon A, Amiot MJ, Dimier-Vallet C, Dufeu I, Habersetzer T, et al. Organic food: state of the art and perspectives. Cah Nutr Diét. 2018;53:141–50.10.1016/j.cnd.2018.02.004Search in Google Scholar

[17] Valencia DN. Brief review on COVID-19: the 2020 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7386.10.7759/cureus.7386Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Jayawardena R, Misra A. Balanced diet is a major casualty in COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):1085–6.10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3):105924.10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard|WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Dashboard; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Gasmi A, Tippairote T, Mujawdiya PK, Peana M, Menzel A, Dadar M, et al. Micronutrients as immunomodulatory tools for COVID-19 management. Clin Immunol. 2020;220:108545.10.1016/j.clim.2020.108545Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Busetto L, Bettini S, Fabris R, Serra R, Dal Pra C, Maffei P, et al. Obesity and COVID-19: an Italian snapshot. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(9):1600–5.10.1002/oby.22918Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Belanger MJ, Hill MA, Angelidi AM, Dalamaga M, Sowers JR, Mantzoros CS. Covid-19 and disparities in nutrition and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):e69.10.1056/NEJMp2021264Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] WHO, Food and nutrition tips during self-quarantine; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Liu J, Rehm CD, Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Quality of meals consumed by US adults at full-service and fast-food restaurants, 2003-2016: persistent low quality and widening disparities. J Nutr. 2020;150(4):873–83.10.1093/jn/nxz299Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Cocchi C, Maffei S, Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(9):1409–17.10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Teng CC, Wang YM. Decisional factors driving organic food consumption: generation of consumer purchase intentions. Br Food J. 2015;117(3):1066–81.10.1108/BFJ-12-2013-0361Search in Google Scholar

[28] Emilien C, Hollis JH. A brief review of salient factors influencing adult eating behaviour. Nutr Res Rev. 2017;30(2):233–46.10.1017/S0954422417000099Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Zineb Ben Khadda et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Foliar application of boron positively affects the growth, yield, and oil content of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Impacts of adopting specialized agricultural programs relying on “good practice” – Empirical evidence from fruit growers in Vietnam

- Evaluation of 11 potential trap crops for root-knot nematode (RKN) control under glasshouse conditions

- Technical efficiency of resource-poor maize farmers in northern Ghana

- Bulk density: An index for measuring critical soil compaction levels for groundnut cultivation

- Efficiency of the European Union farm types: Scenarios with and without the 2013 CAP measures

- Participatory validation and optimization of the Triple S method for sweetpotato planting material conservation in southern Ethiopia

- Selection of high-yield maize hybrid under different cropping systems based on stability and adaptability parameters

- Soil test-based phosphorus fertilizer recommendation for malting barley production on Nitisols

- Effects of domestication and temperature on the growth and survival of the giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) postlarvae

- Influence of irrigation regime on gas exchange, growth, and oil quality of field grown, Texas (USA) olive trees

- Present status and prospects of value addition industry for agricultural produce – A review

- Competitiveness and impact of government policy on chili in Indonesia

- Growth of Rucola on Mars soil simulant under the influence of pig slurry and earthworms

- Effect of potassium fertilizer application in teff yield and nutrient uptake on Vertisols in the central highlands of Ethiopia

- Dissection of social interaction and community engagement of smallholder oil palm in reducing conflict using soft system methodology

- Farmers’ perception, awareness, and constraints of organic rice farming in Indonesia

- Improving the capacity of local food network through local food hubs’ development

- Quality evaluation of gluten-free biscuits prepared with algarrobo flour as a partial sugar replacer

- Effect of pre-slaughter weight on morphological composition of pig carcasses

- Study of the impact of increasing the highest retail price of subsidized fertilizer on rice production in Indonesia

- Agrobiodiversity and perceived climatic change effect on family farming systems in semiarid tropics of Kenya

- Influences of inter- and intra-row spacing on the growth and head yield of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) in western Amhara, Ethiopia

- The supply chain and its development concept of fresh mulberry fruit in Thailand: Observations in Nan Province, the largest production area

- Toward achieving sustainable development agenda: Nexus between agriculture, trade openness, and oil rents in Nigeria

- Phenotyping cowpea accessions at the seedling stage for drought tolerance in controlled environments

- Apparent nutrient utilization and metabolic growth rate of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, cultured in recirculating aquaculture and biofloc systems

- Influence of season and rangeland-type on serum biochemistry of indigenous Zulu sheep

- Meta-analysis of responses of broiler chickens to Bacillus supplementation: Intestinal histomorphometry and blood immunoglobulin

- Weed composition and maize yield in a former tin-mining area: A case study in Malim Nawar, Malaysia

- Strategies for overcoming farmers’ lives in volcano-prone areas: A case study in Mount Semeru, Indonesia

- Principal component and cluster analyses based characterization of maize fields in southern central Rift Valley of Ethiopia

- Profitability and financial performance of European Union farms: An analysis at both regional and national levels

- Analysis of trends and variability of climatic parameters in Teff growing belts of Ethiopia

- Farmers’ food security in the volcanic area: A case in Mount Merapi, Indonesia

- Strategy to improve the sustainability of “porang” (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) farming in support of the triple export movement policy in Indonesia

- Agrarian contracts, relations between agents, and perception on energy crops in the sugarcane supply chain: The Peruvian case

- Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

- Meta-analysis of zinc feed additive on enhancement of semen quality, fertility and hatchability performance in breeder chickens

- Meta-analysis of the potential of dietary Bacillus spp. in improving growth performance traits in broiler chickens

- Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer

- Cross transferability of barley nuclear SSRs to pearl millet genome provides new molecular tools for genetic analyses and marker assisted selection

- Detection of encapsulant addition in butterfly-pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) extract powder using visible–near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics analysis

- The willingness of farmers to preserve sustainable food agricultural land in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Transparent conductive far-infrared radiative film based on polyvinyl alcohol with carbon fiber apply in agriculture greenhouse

- Grain yield stability of black soybean lines across three agroecosystems in West Java, Indonesia

- Forms of land access in the sugarcane agroindustry: A comparison of Brazilian and Peruvian cases

- Assessment of the factors contributing to the lack of agricultural mechanization in Jiroft, Iran

- Do poor farmers have entrepreneurship skill, intention, and competence? Lessons from transmigration program in rural Gorontalo Province, Indonesia

- Communication networks used by smallholder livestock farmers during disease outbreaks: Case study in the Free State, South Africa

- Sustainability of Arabica coffee business in West Java, Indonesia: A multidimensional scaling approach

- Farmers’ perspectives on the adoption of smart farming technology to support food farming in Aceh Province, Indonesia

- Rice yield grown in different fertilizer combination and planting methods: Case study in Buru Island, Indonesia

- Paclobutrazol and benzylaminopurine improve potato yield grown under high temperatures in lowland and medium land

- Agricultural sciences publication activity in Russia and the impact of the national project “Science.” A bibliometric analysis

- Storage conditions and postharvest practices lead to aflatoxin contamination in maize in two counties (Makueni and Baringo) in Kenya

- Relationship of potato yield and factors of influence on the background of herbological protection

- Biology and life cycle Of Diatraea busckella (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) under simulated altitudinal profile in controlled conditions

- Evaluation of combustion characteristics performances and emissions of a diesel engine using diesel and biodiesel fuel blends containing graphene oxide nanoparticles

- Effect of various varieties and dosage of potassium fertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.)

- Review Articles

- Germination ecology of three Asteraceae annuals Arctotis hirsuta, Oncosiphon suffruticosum, and Cotula duckittiae in the winter-rainfall region of South Africa: A review

- Animal waste antibiotic residues and resistance genes: A review

- A brief and comprehensive history of the development and use of feed analysis: A review

- The evolving state of food security in Nigeria amidst the COVID-19 pandemic – A review

- Short Communication

- Response of cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) varieties grown in the southeastern United States to nitrogen fertilization

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences

- Special issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research – Agrarian Sciences: Message from the editor

- Maritime pine land use environmental impact evolution in the context of life cycle assessment

- Influence of different parameters on the characteristics of hazelnut (var. Grada de Viseu) grown in Portugal

- Organic food consumption and eating habit in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Customer knowledge and behavior on the use of food refrigerated display cabinets: A Portuguese case

- Perceptions and knowledge regarding quality and safety of plastic materials used for food packaging

- Understanding the role of media and food labels to disseminate food related information in Lebanon

- Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells

- Validation of an analytical methodology to determine humic substances using low-volume toxic reagents

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development – IConARD 2020

- Behavioral response of breeder toward development program of Ongole crossbred cattle in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia

- Special Issue on the 2nd ICSARD 2020

- Perceived attributes driving the adoption of system of rice intensification: The Indonesian farmers’ view

- Value-added analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus cell encapsulation using Eucheuma cottonii by freeze-drying and spray-drying

- Investigating the elicited emotion of single-origin chocolate towards sustainable chocolate production in Indonesia

- Temperature and duration of vernalization effect on the vegetative growth of garlic (Allium sativum L.) clones in Indonesia

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method

- Special Issue of International Web Conference on Food Choice and Eating Motivation

- Can ingredients and information interventions affect the hedonic level and (emo-sensory) perceptions of the milk chocolate and cocoa drink’s consumers?