Abstract

This paper presents the synthesis of two aminosilane-based external donors for the Ziegler-Natta catalysis: di(piperidyl) dimethoxysilane (DPPDMS) and dipyrrolyldimethoxysilane (DPRDMS). We compared the electron donation by these two compounds in the MgCl2- supported Ziegler-Natta catalysis of the polymerization of hexene-1 into a polyhexene-1 (PHe) elastomer with that of the common donor cyclohexylmethyldimethoxysilane (CHMMS). The catalytic activity of the system and isotacticity of the polymer (PHe) product improved significantly because of the considerable steric hindrance and strong electronic effects of these aminosilane-based external donors. The effects of different external donors on the catalytic efficiency, polymer isotacticity, molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of the PHe products were investigated. Under the best reaction conditions, the catalyst activity, polymer molecular weight, and glass-transition temperature were determined as 899 g/g Cat·h-1, MW = 252,300 g/mol, and -41.39°C, respectively. The PHe was characterized by FTIR and NMR. This report also describes blending of PHe and low density polyethylene that leads to a significant increase in the impact strength and elongation at breaks.

1 Introduction

Polyhexene-1 (PHe) is a novel elastomeric material synthesized through the homopolymerization of hexene-1. Among the various α-olefin isotactic polymers, the homopolymers of butene-1 and its posterior olefin types are all crystalline thermoplastics. The homopolymers of octene-1 and its anterior olefin types are also crystalline; only PHe is an entirely amorphous elastomer (1). PHe, a polyolefin elastomer with properties intermediate between those of rubber and plastic, can be used as a modifier for these materials (2). Due to the low processing temperature, PHe can be easily mixed with rubbers not clear how processing temprature and polarity are related, especially EPR, EPDM, and PS (3). PHe is frequently applied to plastic products (4), and the modification of PE and PP by PHe can significantly improve elongation at breaks.

In 1963, polyolefin rubber was invented by Goodyear (5) and used in the medical polymer field. The patents US3933769 (6) and US3991262 (7) describe the use of Ziegler-Natta catalysts in the synthesis of the Hexsyn polyolefin rubbers made from 97% hexene-1 and a small amount of 5-methyl-1, 4-hexadiene. Lord Corporation also synthesizes this polymer for use in artificial lumbar intervertebral discs and the sidewall material of high-grade tires (8). Hexsyn rubber is the optimal substitute material for artificial heart valve prosthesis (9).

Most hexene-1 polymerizations catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalysts show only slight differences in forms or treatment methods (10, 11, 12). In 2016, Nouri-Ahangarani et al., reported the polymerization of hexene-1 catalyzed by the FeCl3-doped TiCl4/diethoxymagnesium catalyst system (13). That study showed that the FeCl3-doped catalyst system could improve both the catalytic activity in the polymerization reaction and the isotacticity of the polymerization products, although the products remained amorphous. In 2018, Nazari et al. improved the impact strength of polystyrene (PS) and elongation at breaks in its synthesis were improved by modifying it with PHe (14).

The current study considers the elastomeric properties of PHe and proposes a novel Ziegler-Natta catalytic system for its synthesis by the homopolymerization of hexene-1. This work also involved a comprehensive investigation of polymerization conditions and the development of a series of characterization tests for polymers.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and instruments

The Z-N118 catalyst (Ti content: 2.6%) was purchased from Basell. The n-hexane (Tianjin No.3 Chemical Reagent Factory), cyclohexane (Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), n-heptane (Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), and hexene-1 (J&K Scientific Co., Ltd) were all analytical grade and pretreated with 5A molecular sieves before use. Triethylaluminium (1.0 mol⋅L-1 in hexane solution) was purchased from Albemarle. Nitrogen (99.99% purity) was from Daqing Xuelong Gas Co., Ltd. Analytical-grade cyclohexyl methyl dimethoxy silane (CHMMS) was purchased from J&K Scientific Co., Ltd.

Experiment apparatuses included a two-necked Schlenk flask (Synthwave); a 500 mL three-necked flask (Tianjin Shengbo Glass Instrument Factory); a DF-101S thermostatic oil bath in which the sample can be magnetically stirred (Tianjin Yuhua Instrument Co., Ltd.); Bruker-Tonsor27 FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany); a GPC220CV high-temperature gel permeation chromatography apparatus from WATERS, USA; and a Bruker DRX-400 nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C-NMR) spectrometer from Bruker, USA.

2.2 Experimental procedures

2.2.1 Synthesis of external donors

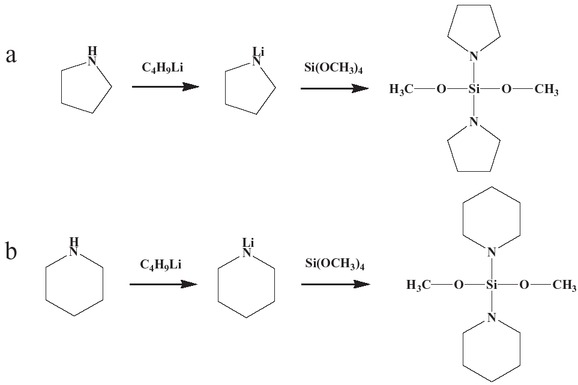

All reactions were carried out under argon using Schlenk standard technology. The synthesis of the external donors is shown in the following schematic diagram (15) (Scheme 1).

The reaction structures of DPPDMS (a) and DPRDMS (b).

Preparation of DPPDMS

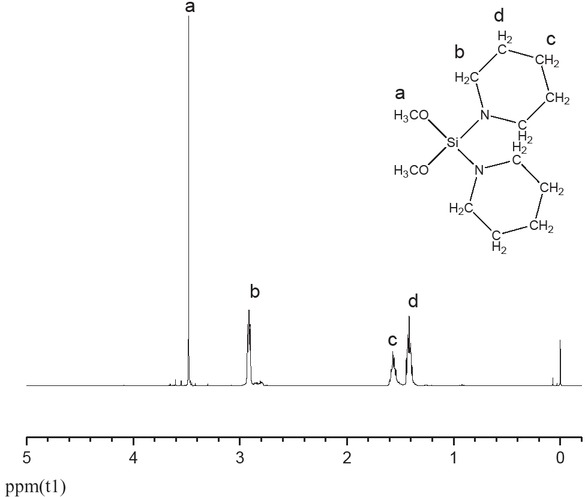

The reaction needs to add 80 mL of n-heptane to a 500 mL five-necked flask followed by 23 mL of 0.2 mol/L piperidine. After the drop-wise addition of 133 mL 1.66 mol/L n-butyllithium in n-heptane, it needs slowly cooling the mixture with water at 25°C (room temperature) for 1 h. After further drop-wise addition of tetramethoxysilane (15 mL of a 0.1 mol/L (0.1 M), the mixture was again cooled with water. Upon completion of the additions, the resultant mixture was cooled at 25°C (room temperature) for 6 h and then incubated for a further 12 h. The supernatant liquid was transferred under argon into a 250 mL three-necked flask, and the precipitate washed three times with 30 mL portions of n-heptane. A colorless transparent liquid (DPPDMS) was obtained (yield: 53.1%) after the solvent and unreacted reagents were removed by reduced pressure distillation (-0.1 MPa). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.4(m, 2H), 1.6(m, 2H), 2.9(m, 2H), 3.5(s, 3H) (Figure 1).

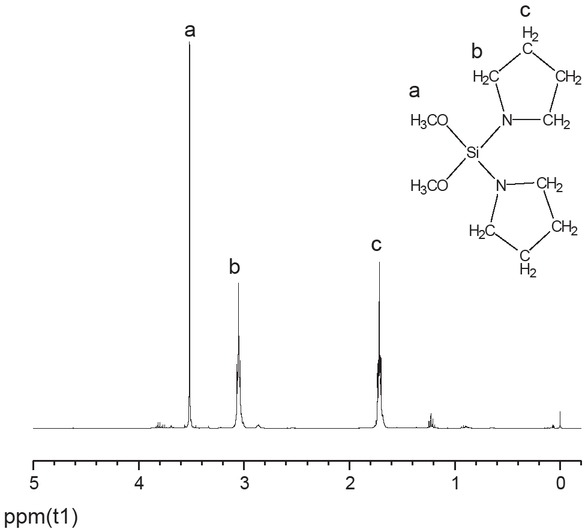

Preparation of DPRDMS

The reaction conditions were identical to those used for the preparation of DPPDMS as described in Section 2.2.1 except that nafoxidine was used in place of piperidine. After reduced pressure distillation, the product DPRDMS, a colorless transparent liquid was obtained in 40.1% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3); δ 1.7(m, 2H), 3.1(m, 2H), 3.5(s, 3H) (Figure 2).

1H NMR spectrum of DPPDMS.

1H NMR spectrum of DPRDMS.

2.2.2 Polymerization of hexene-1

This reaction requires adding of 62 mL hexene-1 (0.5 mol), 50 mL hexane, external donors (ED), and triethylaluminium to a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The reaction was carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere with the contents of both water and oxygen less than 0.1 ppm. After 10 min stirring on an oil bath at 20 to 50°C, we added the test catalyst to the flask. Following 2 h reaction, the mixture was terminated using 10% hydrochloric acid, filtered, dried and weighed.

2.3 Test and characterization

2.3.1 Calculation of catalytic activity

The catalytic activity (A) was:

where M was the mass of the product, and m was the mass of the catalyst in grams.

2.3.2 Molecular weight determination and distribution

The molecular weight of a sample was determined by gel permeation chromatography. Samples were dissolved in 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene at elevated temperatures. Gel permeation chromatography was carried out at 150°C at a flow rate of 1.00 mL/min on a PL GPC-220 chromatograph equipped with a differential refractive index detector.

2.3.3 The test method of FT-IR

FT-IR was carried out on PERKIN-ELMER Model 1700 FT-IR from Perkin-elmer, USA.

2.3.4 The test method of 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR

13C-NMR was carried out on a Bruker-400 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance apparatus, and o-dichlorobenzene was used as a solvent.

1H-NMR was carried out on a Bruker-400 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance apparatus in which tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal standard and chloroform was used as a solvent.

2.3.5 Mechanical performance

The shore hardness is tested by the national standard GB/T531-92.

Tensile strength, yield strength and elongation at break were tested according to GB/T1042-92 using high-speed rail AI-7000S tensile testing machine.

3 Results and discussion

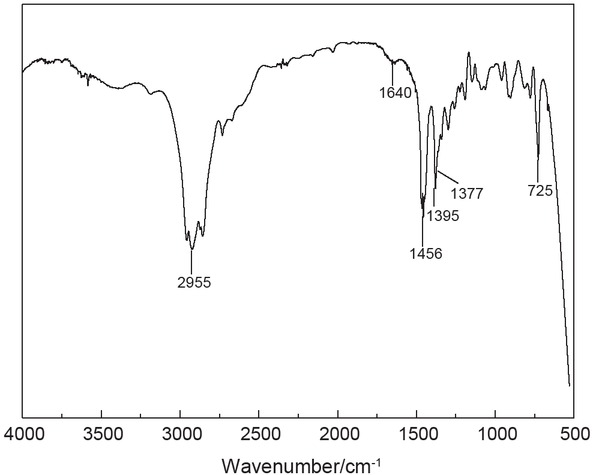

3.1 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of PHe

PHe sample was characterized by FTIR spectroscopy. Figure 3 shows a C–H stretching vibration band over the range of 2855~2955 cm-1; there were two other stretching bands at 1377 and 1456 cm-1, respectively. These bands may be a C–H in-plane bending of the methyl group. The weak band at 725 cm-1 may result from the butyl side chain. The weakened C–H stretching at 1395 cm-1 and reduced C=C stretching vibration at 1640 cm-1 of vinyl indicate the formation of PHe.

The FTIR of polyhexene-1.

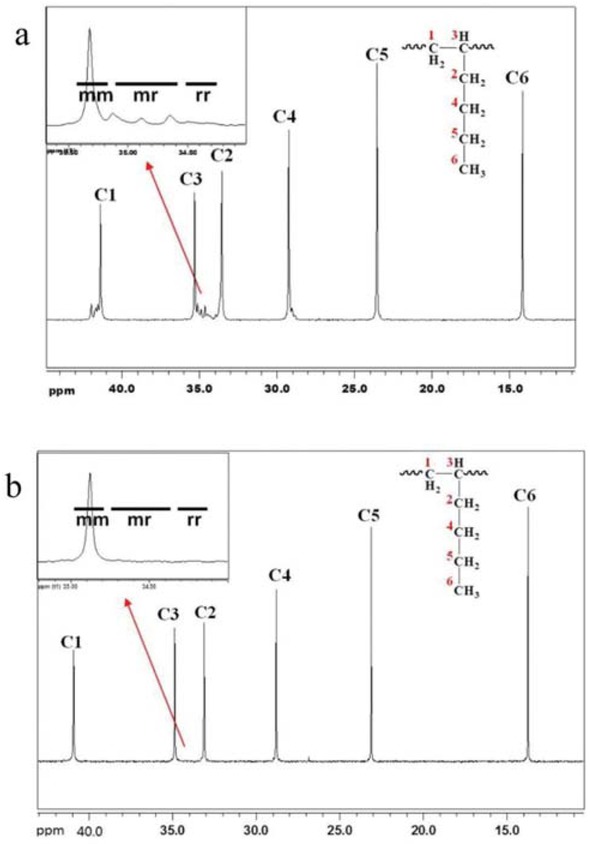

3.2 13C NMR spectra of PHe and calculation of its isotacticity

The PHe elastomer samples with isotacticities of 71% and 93% were characterized by 13C NMR, as shown in Figure 4. The chemical shift values of the six carbons of poly(1-hexene) observed are in good agreement with other reports (16). The isotactic calculation method is from C3 to C2 (between 36 ppm and 34 ppm), and the ratio of the isotactic part mm divided by mm+mr+rr is the isotacticity of polyhexene-1. The peak heights were uniform. The methyl signal was observed over the range of 13.00~17.00 ppm. The carbon atoms of the CH2 group in the branch appeared at 22.70~23.18 ppm. The resonance of the carbon atoms at ca 28 and 40 ppm suggests the presence of the methyl side chain with 1,3 and 1,6 couplings.

The 13C NMR of polyhexene-1 with an isotacticity of 93% (a) and 71% (b).

3.3 Effects of External Donors (EDs) on the polymerization of hexene-1

We characterized the effects of different EDs on the polymerization reaction. The data in Table 1 show that the EDs alter the efficiency of the catalyst, and also change the tacticity of the product. Regarding catalytic efficiency, the silane-based EDs, DPPDMS and DPRDMS, both outperform CHMMS, possibly because of steric hindrance and an electronic effect. CHMMS, commonly used in industry, has only one hexamethylene group, while DPPDMS and DPRDMS contain two piperidyl and two pyrrole groups, respectively. Therefore, the steric hindrance provided by these groups in DPPDMS and DPRDMS would facilitate electron donation and result in

Effects of the different external donors on the performance of MgCl2-supported catalysts for hexene-1 polymerization.

| Run | External donor | Activity (gPHe/gCat·h-1) | I.I. (%) | Mw ×10-4 | MWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 430 | 71.0 | 19.3 | 6.85 |

| 2 | CHMMS | 599 | 91.5 | 21.9 | 5.43 |

| 3 | DPPDMS | 928 | 90.2 | 20.6 | 4.62 |

| 4 | DPRDMS | 781 | 96.5 | 18.7 | 4.10 |

| 5 | DPPDMS/ | 899 | 93.7 | 25.2 | 4.67 |

| DPRDMS |

Polymerization conditions: cat = 10 mg, hexene-1 = 62 mL, cyclohexane = 50 mL, n(Al)/n(Ti) = 200, T = 30°C, t = 2 h, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20

higher isotacticity of the product. The conjugation effect due to the introduction of piperidyls and pyrrolyls would also lead to enhanced electron donating ability and higher catalytic activity. Table 1 also shows that in the presence of both EDs, (DPPDMS and DPRDMS), the polymerization reaction gives optimal results. Hence, the ED synthesized by the complex formulation of DPPDMS and DPRDMS (mass ratio = 1:1) was used for all of our polymerizations.

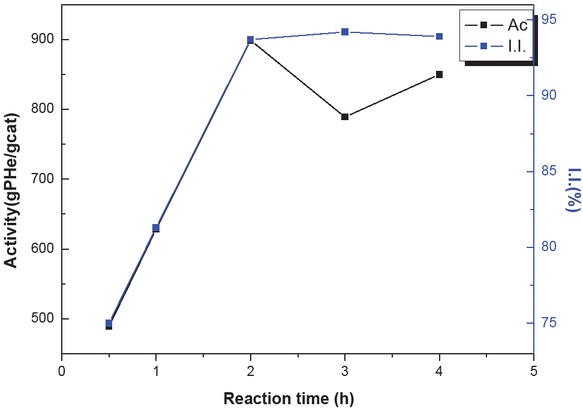

3.4 Effects of reaction time on the hexene-1 polymerization reaction

Table 2 displays the effects of reaction time on the catalytic activity of the system and the isotacticity of hexene-1 homopolymer. Figure 5 shows that the amount of hexene-1 homopolymer formed increased until it reached a maximum. With longer reaction times, the dispersion of catalyst in hexene-1 became more uniform with stirring, and the active sites of the catalyst were more accessible so that maximum catalytic activity (899 g/g Cat·h-1) was obtained. Extended reaction time led to a balanced state between the available active sites of the catalyst and the hexene-1 molecules so that no more active sites were available for catalysis of hexene-1 after 2 h. The polymer isotacticity reached 93.7% in 2 h. After another hour the polymer isotacticity reached its peak value (94.2%), while the catalytic activity decreased slightly. Therefore, the best reaction time is 2 h.

Effect of reaction time on catalyst activity and isotacticity.

Effect of reaction time on catalyst activity (formation of PHe) and isotacticity of the PHe product.

| T (h) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (g PHe/g Cat·h-1) | 489 | 628 | 899 | 789 | 850 |

| I.I. (%) | 75.0 | 81.3 | 93.7 | 94.2 | 93.9 |

Polymerization conditions: cat = 10 mg, hexene-1 = 62 mL, cyclohexane = 50 mL, n(Al)/n(Ti) = 200, T = 30°C, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20

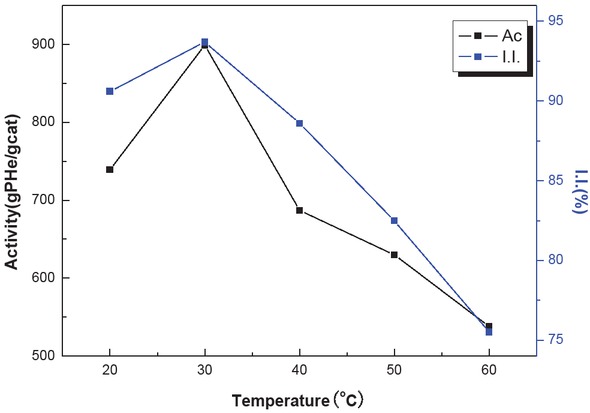

3.5 Effects of reaction temperature on hexene-1 polymerization

Table 3 shows the effects of reaction temperature on the catalytic activity of the system and the isotacticity of

Effect of temperature on catalyst activity (formation of PHe) and isotacticity of the PHe product.

| T (°C) | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (gPHe/gCat·h-1) | 739 | 899 | 687 | 630 | 538 |

| I.I. (%) | 90.6 | 93.7 | 88.6 | 82.5 | 75.5 |

Polymerization conditions: cat = 10 mg, hexene-1 = 62 mL, cyclohexane = 50 mL, n(Al)/n(Ti) = 200, t = 2 h, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20

hexene-1 homopolymer at a 2 h reaction time. Figure 6 shows that the reaction rate increased and then decreased with the increasing reaction temperatures, with optimal product formation at 30°C yielding 899 g/g Cat·h-1. The increased reaction temperature leads to the formation of more catalyst active sites, and the rapid formation of active sites within a short time leads to higher catalytic activity. In this reaction system, the reaction capacity of alkylaluminium is also increased at elevated temperatures, which raises the number of active sites. This effect also explains the increase in catalytic activity. Further temperature increases lead to further dissolution of PHe in cyclohexane, which leads to a decreased hexene-1 concentration in these active sites and thus to lower catalytic activity. For these reasons, there is an optimum reaction temperature at 30°C.

Effect of temperature on catalyst activity and isotacticity.

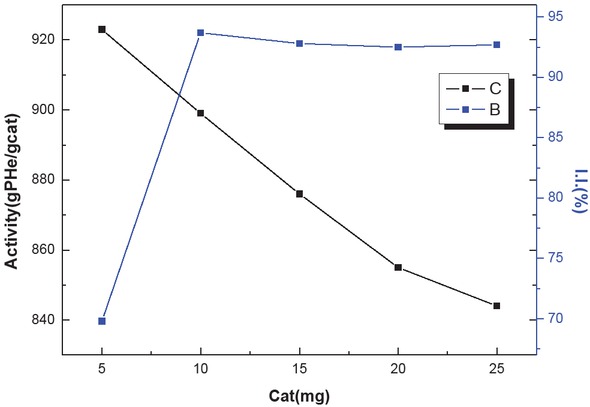

3.6 Effects of catalyst dosage on the hexene-1 polymerization reaction

Table 4 shows the effect of catalyst dosage on the rate of the reaction and isotacticity of hexene-1 homopolymer at 30°C at a reaction time of 2 h. Figure 7 shows that an increase in catalyst dosage increases the catalytic activity

Effect of catalyst dosage on catalyst activity and isotacticity.

Effect of catalyst dosage on catalyst activity and polymer isotacticity.

| Cat (mg) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (gPHe/gCat·h-1) | 923 | 899 | 876 | 855 | 844 |

| I.I. (%) | 69.8 | 93.7 | 92.8 | 92.5 | 92.7 |

Polymerization conditions: hexene-1 = 62 mL, cyclohexane = 50 mL, n(Al)/n(Ti) = 200, t = 2 h, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20, T = 30°C

until it reaches a maximum at 10 mg. At low catalyst concentrations, the increase in catalyst dosage enables more hexene-1 molecules to contact the active sites so the catalytic activity increases. However, after the catalyst dosage exceeds 10 mg, the catalytic activity reaches a plateau. Although more catalysts contributed to more active sites availability, a saturation state is reached for the hexene-1 monomer concentration, so chain growth is not improved any further. We observed the best results using 10 mg catalyst in the reaction mix.

3.7 Effects of solvent type and dosage on hexene-1 polymerization

Table 5 shows the effects of solvent type and dosage on the catalytic activity in the reaction, and on the isotacticity, molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of the hexene-1 homopolymer product at 30°C after a reaction time of 2 h. All properties are improved after solvent addition. The catalyst was premixed in solution, which contributed to more uniform catalyst distribution and sufficient contact between active sites and hexene-1 molecules. (The catalyst is a solid substance and is mixed

Effects of the types and amount of solvent on catalyst activity and polymer isotacticity.

| Solvent | Amount (mL) | Activity (g PHe/g Cat) | I.I. (%) | Mw×10-4(g/mol) | MWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | - | 430 | 88.5 | 18.6 | 5.88 |

| Hexane | 50 | 610 | 90.1 | 19.8 | 4.20 |

| Cyclohexane | 50 | 899 | 93.7 | 25.2 | 4.67 |

| Heptane | 50 | 1018 | 93.5 | 27.8 | 3.27 |

Polymerization conditions: cat = 10 mg, hexene-1 = 62 mL , n(Al)/n(Ti) = 200, t = 2 h, T = 30°C, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20

with a solvent to form a mixture.) The catalytic activity, polymer isotacticity, molecular weight and molecular weight distribution were generally improved with magnetic stirring. We studied three solvents commonly used in industry: n-hexane, cyclohexane, and n-heptane. These data show that the optimum catalytic activity and isotacticity occur in n-heptane. However, we found poor molecular weight distribution for the polymer when using n-heptane as the solvent. This distribution was detrimental to subsequent polymer processing. The best solvent is cyclohexane.

3.8 Effects of alkylaluminium dosage on the polymerization of hexene-1

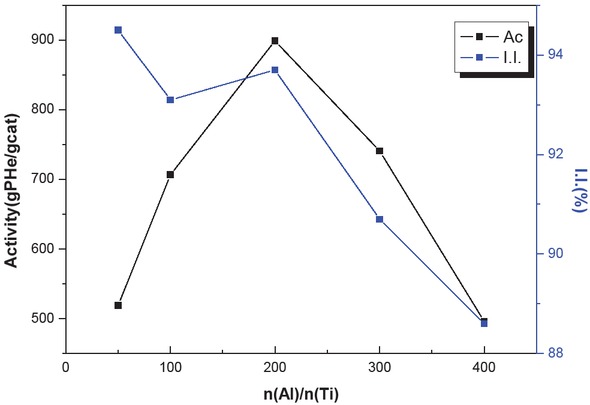

Table 6 displays the effects of alkylaluminium dosage on the formation and isotacticity of hexene-1 homopolymer product at 30°C after a reaction time of 2 h (10 mg catalyst; 0.5 mol hexene-1 (62 mL); 50 mL hexane; n(Al)/n(CHMMS) = 20). Figure 7 shows that as the mole ratio of co-catalyst to the main catalyst, AlEt3, increases, the catalytic activity first increases and then decreases. The AlEt3 at the beginning of the reaction reacted with impurities. Thus, some titanium (Ti) failed to be activated, and the reaction resulted in lower average polymerization activity. Increases in AlEt3 dosage lead to more Ti activation and contribute to higher polymerization activity. However, when the ratio of n(Al)/n(Ti) exceeds 200, further increase in AlEt3 dosage leads to decreased polymerization activity. This effect can be explained as follows (17, 18, 19):

Effect of Al/Ti mole ratio on catalyst activity and polymer isotaticity.

| n(Al)/n(Ti) | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (gPHe/gCat·h-1) | 519 | 707 | 899 | 741 | 496 |

| I.I.(%) | 94.5 | 93.1 | 93.7 | 90.7 | 88.6 |

Polymerization condition: cat = 10 mg, hexane = 62 mL, coclohexane = 50 mL , t = 2 h, n(Al)/n(ED) = 20, T = 30°C

The alkylaluminium competes with the monomer for the adsorption onto active sites.

A certain amount of catalyst active sites are present in this system. Further increases in the catalyst dosage do not lead to more active sites. Thus, the catalyst activity curve at higher alkylaluminium amounts in the reaction mixture reaches a maximum and does not show further change.

With increasing AlEt3 dosage, the propagating chains shift to AlEt3, so the effective catalytic ability of AlEt3 decreases the polymerization activity.

Excessive AlEt3 reduces Ti4+ to Ti2+ which leads to the loss of polymerization activity. As the mole ratio of n(Al)/n(Ti) increases, the polymer isotacticity shows an overall decrease, perhaps because the increase in alkylaluminium dosage increases the probability of transfer to alkylaluminium, and decreases the polymer isotacticity. The best value for catalytic activity is observed at n(Al)/n(Ti) of 200 (Figure 8).

Effect of Al/Ti mole ratio on catalyst activity and polymer isotaticity.

3.9 Application of PHe produced

The linear low density polyethylene (LLDPE) 7042 was blended with the PHe produced (PE/PHe = 0.05, 0.1, 0.15 and 0.2) synthesized in this study. The molecular weight of LLDPE7042 was 10.7857 and the molecular weight distribution was 3.75. The mechanical properties of the blends were investigated by the extrusion and pelletizing test using a twin screw extruder, and the results are shown in the following table.

Table 7 shows that the elongation at break and the impact strength of the polyethylene added with PHe are improved, and gradually increase with the increase of the PHe content. This is mainly due to the existence of four carbon chains on the side chain of PHe, which makes the polymer chains slide between each other and therefore results in elastic properties. However, the tensile strength and yield strength all decrease, since the lack of double bonds in the PHe structure makes it unable to form crosslinks.

Comparison of mechanical properties of blends with different proportions.

| Sample | Tensile strength (MPa) | Yield strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | Impact strength (J/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 25.43 ± 1.0 | 11.26 ± 0.1 | 484 ± 25 | 79.6 ± 0.5 |

| PE/PHe5% | 22.18 ± 1.0 | 10.77 ± 0.1 | 513 ± 25 | 80.7 ± 0.5 |

| PE/PHe10% | 18.29 ± 1.0 | 10.13 ± 0.1 | 546 ± 25 | 83.5 ± 0.5 |

| PE/PHe15% | 16.01 ± 1.0 | 8.38 ± 0.1 | 578 ± 25 | 88.7 ± 0.5 |

| PE/PHe20% | 12.68 ± 1.0 | 6.02 ± 0.1 | 617 ± 25 | 91.2 ± 0.5 |

4 Conclusion

This work describes the synthesis of two new efficient types of external donors (aminosilanes) for titanium-catalyzed hexane-1 polymerization. The catalytic activity of the system and isotacticity of the polymer (PHe) product improved significantly because of the considerable steric hindrance and strong electronic effects of these aminosilane-based external donors.

We analyzed the structures of the polymerization products by FTIR and NMR and calculated the PHe isotacticity using NMR.

The polymerization of hexene-1 was carried out at atmospheric pressure; the monomer concentration, n(Al)/n(Ti) ratio, reaction time, reaction temperature, and other parameters were selected. The catalyst activity, polymer molecular weight, and glass-transition temperature were determined as 899 g/g Cat·h-1, MW = 252,300 g/mol, and -41.39°C, respectively.

The blending modification of low density polyethylene with PHe was studied in this work. The results show that the impact strength and elongation at polyethylene breaks improved substantially upon addition of PHe, which demonstrates the usefulness of PHe in industrial applications.

References

1 Tu C.F., Biesenberger J.A., Stivala S.S., Physicochemical Studies of Polyhexene-1. I. Polymerization Kinetics. Macromolecules, 1970, 3(2), 206-214. 10.1021/ma60014a017Search in Google Scholar

2 Jozaghkar M.R., Jahani Y., Arabi H., Ziaee F., Preparation and Assessment of Phase Morphology, Rheological Properties, and Thermal Behavior of Low-Density Polyethylene/Polyhexene-1 Blends. Polym.-Plast. Technol., 2018, 57(8), 757-765, 10.1080/03602559.2017.1344858Search in Google Scholar

3 Hanifpour A., Bahri‐Laleh N., Nekoomanesh‐Haghighi M., Mirmohammadi S.A., Poly1‐hexene: New impact modifier in HIPS technology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2016, 133(35), 10.1002/app.43882Search in Google Scholar

4 Morales P., Gómez L.M., Olayo M.G., Cruz G.J., Palacios C., Morales J., et al., Polyethylene Obtained by Plasma Polymerization of Hexene. Macromol. Sy., 2009, 283(1), 13-17, 10.1002/masy.200950903Search in Google Scholar

5 Gladding E.K., Sulfur-curable elastomeric copolymers of ethylene, alpha-olefins, and 5-methylene-2-norbornene. U.S. Patent 3,093,621, 1963-6-11.Search in Google Scholar

6 Lal J., Sandstrom P.H., Sulfur vulcanizable interpolymers. U.S. Patent 3,933,769, 1976-1-20.Search in Google Scholar

7 Lal J., Sandstrom P.H., Sulfur vulcanizable interpolymers. U.S. Patent 3,991,262, 1976-11-9.Search in Google Scholar

8 Mcmillin C.R., Characterization of hexsyn, a polyolefin rubber. J. Biomater. Appl., 1987, 2(1), 3-99, 10.1177/088532828700200101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9 Kiraly R., Yozu R., Hillegass D., Harasaki H., Murabayashi S., Snow J., et al., Hexsyn trileaflet valve: application to temporary blood pumps. Artif. Organs, 1982, 6(2): 190-197, 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1982.tb04082.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Echevskaya L., Matsko M., Nikolaeva M., Sergeev S., Zakharov V., Kinetic Features of Hexene-1 Polymerization over Supported Titanium-Magnesium Catalyst. Macromol. React. Eng., 2014, 8(9), 666-672, 10.1002/mren.201400009Search in Google Scholar

11 Nouri-Ahangarani F., Nekoomanesh M., Mirmohammadi S.A., Bahri-Laleh, N., Effects of FeCl3 doping on the performance of MgCl2TiCl4DNPB catalyst in 1-hexene polymerization. Polyolefins J., 2017, 4(2), 253-262. 10.22063/POJ.2017.1467Search in Google Scholar

12 Vasilenko I.V., Kostyuk S.V., Gaponik L.V., Kaputskii F.N., Polymerization of 1-Hexene on Catalytic System TiCl4-Al(C6H133•Mg(C6H132 Russ. J. Appl. Chem+, 2004, 77(2), 295-298, 10.1023/B:RJAC.0000030370.31741.ddSearch in Google Scholar

13 Nouri-Ahangarani F., Bahri-Laleh N., Nekoomanesh-Haghighi M., Karbalaie M., Synthesis of highly isotactic poly 1-hexene using Fe-doped Mg(OEt)2/TiCl4/ED Ziegler-Natta catalytic system. Des. Monomers Polym., 2016, 19(5), 394-405, 10.1080/15685551.2016.1169373Search in Google Scholar

14 Nazari D., Bahri‐Laleh N., Nekoomanesh‐Haghighi M., Jalilian S.M., Rezaie R., Mirmohammadi S.A., (2018).. New high impact polystyrene: Use of poly (1‐hexene) and poly (1‐hexene‐co‐ hexadiene) as impact modifiers. Polym. Advan. Technol., 2018, 29(6), 1603-1612, 10.1002/pat.4265Search in Google Scholar

15 Ikeuchi H., Yano T., Ikai S., Sato H., Yamashita J., Study on aminosilane compounds as external electron donors in isospecific propylene polymerization. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem., 2003, 193(1-2), 207-215, 10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00465-XSearch in Google Scholar

16 Ahmadjo S., Preparation of ultra high molecular weight amorphous poly (1‐hexene) by a Ziegler-Natta catalyst. Polym. Advan. Technol., 2016, 27(11), 1523-1529, 10.1002/pat.3828Search in Google Scholar

17 Puhakka E., Pakkanen T.T., Pakkanen T.A., Theoretical investigations on Ziegler-Natta catalysis: Alkylation of the TiCl4 catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem., 1997, 120(1-3), 143-147.10.1016/S1381-1169(96)00433-5Search in Google Scholar

18 Trischler H., Höchfurtner T., Ruff M., Paulik C., Influence of the aluminum alkyl co-catalyst type in Ziegler-Natta ethene polymerization on the formation of active sites, polymerization rate, and molecular weight. Kinet. Catal+, 2013, 54(5), 559-565.10.1134/S0023158413050170Search in Google Scholar

19 Tarazona A., Koglin E., Buda F., Coussens B.B., Renkema J., van Heel S., et al., Structure and Stability of Aluminum Alkyl Cocatalysts in Ziegler-Natta Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. B, 1997, 101(22), 4370-4378.10.1021/jp963999eSearch in Google Scholar

© 2019 Yan et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die