Abstract

Wound infection is a significant burden on public health. Most present antibacterial agents are typically toxic and devoid of long-term durability. We reported an antimicrobial microcapsule with Chinese nutgall (CN) encapsulated, which was a plant-derived extraction. It is biocompatible and has been used in traditional medicine systems. Sodium alginate (SA) and chitosan worked as shells. The promise of the design is to adopt biocompatible natural polymers and electrostatic attractive chitosan and SA form stable shells to keep long-term release of CN. The results exhibited microcapsules with integrated performance of biocompatibility, long-term durability (inhibition rate of 98.99% against S. aureus after 12 h and 100% after 12 h, 99.61% against E. coli after 6 h and 100% after 12 h), high antibacterial efficacy (with S. aureus inhibition zones of 7.67 mm and E. coli inhibition zones of 5.27 mm) and ease of storage (-20°C for more than 60 h). Their successful fabrication may provide new insights into application of traditional cotton gauze in a sustainable and multifunctional form.

1 Introduction

Bacterial infection of open wounds constitutes the forefront of injury treatments. Wound beds provide a moist, warm and nutritious environment for microbial growth. Among four time-dependent wound healing phases, which are hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and remodeling, the inflammation phase is the riskiest for bacteria attack (1). Various substances like toxins and proteases can cause prolonged inflammatory response of the host tissue, interfering with the wound healing process (2). To prevent the microbial infection, various antibacterial agents have been applied on the wound, including quaternary ammonium salts and silver nanoparticles (3). Although these agents can significantly minimize wound infections, they cannot satisfy wound healing needs as they still exhibit some toxicity to human beings. Besides, their immediate biocidal effects may suffer from significant decrease due to the irreversible consumptions, which work by direct contact killing (4). Thus, nontoxic and prolonged antimicrobial systems to provide protections from bacterial infections are needed.

A desirable design of antimicrobial systems requires an optimization of two important properties: the biocompatibility of antibacterial agents and the durability of biocidal functions, which affects their long-term usage. There is a growing interest in adopting natural antibacterial compounds such as extracts from herbs and plants for defending microbe because of their biocompatibility. Besides, the relatively low frequency of infectious diseases in plants suggests these natural defense mechanisms can be very effective (5). Cisowska A. presented the antimicrobial properties of anthocyanin and its identified compounds. Generally, anthocyanins are active against different microbes, and Gram-positive bacteria usually are more susceptible to the anthocyanin action than Gram-negative ones (6). H.J.D. Dorman studied the antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils from black pepper, geranium, nutmeg and oregano. The results demonstrated the plant volatile oils had great potentials as biocidal agents (7). However, the antibacterial function did not last long because of volatilization. Drug delivery technology by incorporating biocidal agents into hydrogels could be a strategy and was extensively investigated recently (8, 9, 10). Hydrogels are cross-linked networks of hydrophilic polymers capable of retaining large amounts of water yet remaining insoluble and maintaining their three-dimensional structure (11). However, the necessary criteria of hydrophilic polymers put limitations on their applications. And they have the disadvantage of burst release of drugs through breakdown of the matrices due to poor mechanical properties and high swelling ratio (12). Microcapsules have been developed as a convenient technology for drug delivery to protect encapsulated drugs from the external environment and control their release behaviors. They would be, in this regard, a promising candidate for the antimicrobial system. Yang H. prepared artemisia argyi oil-loaded antibacterial microcapsules by hydroxyapatite/poly (melamine formaldehyde) hybrid shells. They illustrated controlled release and long-term antimicrobial activity. However, the biocompatibility needs to be investigated furtherly (13). Tea tree oil-loaded antibacterial microcapsules were fabricated from sodium alginate/quaternary ammonium salt of chitosan by Mingjie Chen. High bacterial inhibition rate was demonstrated. And the surface roughness of microcapsules needed to be improved if applied for solid material release (14).

The Chinese nutgall (CN), which is a nature antibacterial extract without side effects, is getting more attention for biocidal functions (15). In Asian countries, it has been used for centuries in traditional medicines for treating inflammatory diseases. Water extract of CN is effective for inflamed tonsils, while direct application on skin cures swelling and inflammation. The constituents of CN are mainly hydrolysable tannins of tannic acid, gallic acid, ellagic acid and methyl gallate (16). Compared with synthetic antibacterial agents, CN is highly effective and nontoxic. To the best of our knowledge, although CN has been applied as antibacterial agents for long, most of them adopted CN extract directly. And CN still has great potential in long term-release or multi-functional antibiotics. Microcapsules are made up of the core and the shell. The shell has to stand various loads during fabrication and can degrade to release encapsulated materials. Sodium alginate (SA) is an anionic natural macromolecule, which is composed of poly-β-1, 4-d-mannuronic acid (M units) and α-1, 4-l-glucuronic acid (G units) in varying proportions by 1–4 linkages. SA can be extracted from marine algae or produced by bacteria, and so it is abundant, renewable, non-toxic, water-soluble, biodegradable and biocompatible (17). As a cationic polymer derived chitin, chitosan is widely obtained. Besides, chitosan has great advantages of biocompatibility, biodegradability and hemostasis. It has been one of the most important antimicrobials against a broad spectrum of bacteria (18). It can also electrostatically interact with SA to form stable shells to protect materials encapsulated.

Thus, plant-derived CN was adopted as cores to fabricate biocompatible and long durability antimicrobial microcapsules by incorporating SA and chitosan as shells. All adopted materials are natural polymers. Cationic chitosan and anionic SA form stable shells to control the release of encapsulated CN. Chitosan can also provide biocidal functions. Besides, partial chitosan degradation or CN permeation through pores can release more extracts defending microbe. The microcapsules exhibit integrated properties of biocompatibility, long-term durability, high antibacterial efficacy and ease of storage. The incorporation of antibacterial microcapsules as a biocidal layer on wound dressings was demonstrated to achieve promising applications in wound dressing.

2 Experimental

2.1 Experimental materials

SA was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Chitosan (deacetylation degree 92.36%) was purchased in Jinke Biochemical Co., Ltd (Zhejiang, China). Calcium chloride (CaCl2), glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH, 98% in concentration), methyl alcohol (CH3OH), glutaraldehyde (25%) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were obtained from Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China), with analytical grade. CN extract was purchased from Huilin Bio-technology Co., Ltd (Shanxi, China).

2.2 Preparation of the CN - SA/ chitosan microcapsules

CN - SA/ chitosan microcapsules were fabricated by the orifice granulation method (19). Firstly, CN and SA - chitosan solutions were prepared as follows. Solution A: CN extract was dissolved into NaOH solution, which was produced by dissolving NaOH in distilled water. Solution B: NaOH was dissolved in CH3COOH solution and the chitosan was added into the mixture. Secondly, the solution A was dropwise added into solution B, and the system (pH=5.5) was stirred for 30 min at 45°C. Thirdly, the glutaraldehyde was added to the reaction system to fix microcapsule shape. Finally, the suspension was dried in an electrothermal blowing dryer (Shanghai Yiheng Co., Ltd, China). The optimized parameters were attained by orthogonal experiment and shown in Table 1.

The optimized parameters in preparation CN - SA/ chitosan microcapsules.

| Microcapsule coding | CC wt% | SA wt% | Chitosan wt% | SA wt%: CN wt% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 3.5: 1 |

| B1 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 3.5: 1 |

| C1 | 4 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 3.5: 1 |

| D1 | 5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 3.5: 1 |

| A2 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | / |

| B2 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.3 | / |

| C2 | 4 | 2.0 | 0.1 | / |

| D2 | 5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | / |

2.3 CN encapsulation efficiency and stability

The ultraviolet spectrum of CN in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.7) (20) was measured by UV- vis spectra photometer (TU-1901, Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). And the maximal absorption peak was at the wavelength of 256 nm (Figure S1). Accordingly, mass fraction – absorption intensity curve of CN was obtained (Figure S2). To calculate CN encapsulation efficiency, grinded microcapsules were dissolved in CH3OH and dispersed by ultra-sonication. After filtration, the solution absorption intensity at 256 m wavelength was recorded and CN encapsulation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the weight of CN in microcapsules to theoretical loading CN.

Besides, the storage stability of CN - SA/ chitosan microcapsules in -20°C was also studied. At a predetermined time, CN in microcapsules was dissolved in PBS (pH = 7.7) and its absorption intensity was measured.

2.4 Physical characterization of microcapsules

The morphology of the CN loaded and unloaded microcapsules was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Jeol Ltd., Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. Image processing software ImageJ was applied to measure the diameter of at least 50 microcapsules from at least 10 images. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of different samples was recorded by absorption mode at 2 cm-1 intervals in the range of 4000–600 cm-1 wave numbers, using a FT-IR spectrophotometer (Avatar380, USA). Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) of samples with and without CN was recorded by an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku D/MAX 2550/PC, Japan) operating at 40 kV and 200 mA, along with Cu Kα radiation.

2.5 In vitro release

The release characteristics of CN from antimicrobial microcapsules were measured in PBS (pH = 7.7) to simulate the CN release corresponding to the inflammation phase. Samples were placed in centrifuge tubes with the release medium at 37°C. At predetermined time points, 1 mL solution of each sample was extracted to measure the absorption intensity at 256 nm wavelength. Meanwhile, an equal amount of fresh PBS was supplemented to each centrifuge tube. And the accumulative release rate (%) was calculated as the ratio of released CN at each procedural time to the amount of loaded CN.

2.6 Antibacterial activity of microcapsules

Agar diffusion plate test was applied to evaluate antibacterial activity of microcapsules qualitatively according to ISO 20645:2004 (20). Typical bacteria Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) in wounds were selected as testing organisms (20) and their sensitivity was judged by the zone of inhibition. Microcapsule circle with the diameter of 20 mm was inoculated with approximately 1 mL of bacterial suspension ((1 × 108 CFU/mL) per tryptic soya agar plate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and then measured by a Vernier caliper to determine the zone of inhibition, which was calculated as following formula (1),

where H is the zone of inhibition (mm), D is the total diameter of the specimen and zone of inhibition (mm) and d is the diameter of the specimen (mm).

Oscillation method (GB/T 20944.3-2008, China Standards) was adopted to determine the antibacterial activity of microcapsules quantitatively. Inhibition rates (%) were measured by: (control bacterial suspension (CFU/mL) - sample bacterial suspension (CFU/mL))/ control bacterial suspension (CFU/mL).

2.7 Application of microcapsules onto wound dressings and their antibacterial properties

Cotton gauze is still a standard of care in the management of chronic wounds. It has reasonable gas permeability and effective exudates absorption (21). Here, we designed a composite wound dressing based on the cotton gauze and alginates. And antimicrobial microcapsules were applied on it (Figure 1). The outer cotton gauze layers helped exudates absorption, while the inner SA hydrogel provided a barrier for water vapor permeation. Antimicrobial microcapsules were fixed and incorporated into the SA hydrogel. Three layers were then laminated and antibacterial properties were evaluated according to agar diffusion plate test in ISO 20645:2004. For each sample, three specimens were tested.

Composite wounding dressing.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data reported was the means and standard deviations, and the error bars in figures corresponded to standard deviations. t-tests were used to determine the statistical difference. The data in the figures were marked by (*) for p < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 CN encapsulation efficiency and stability

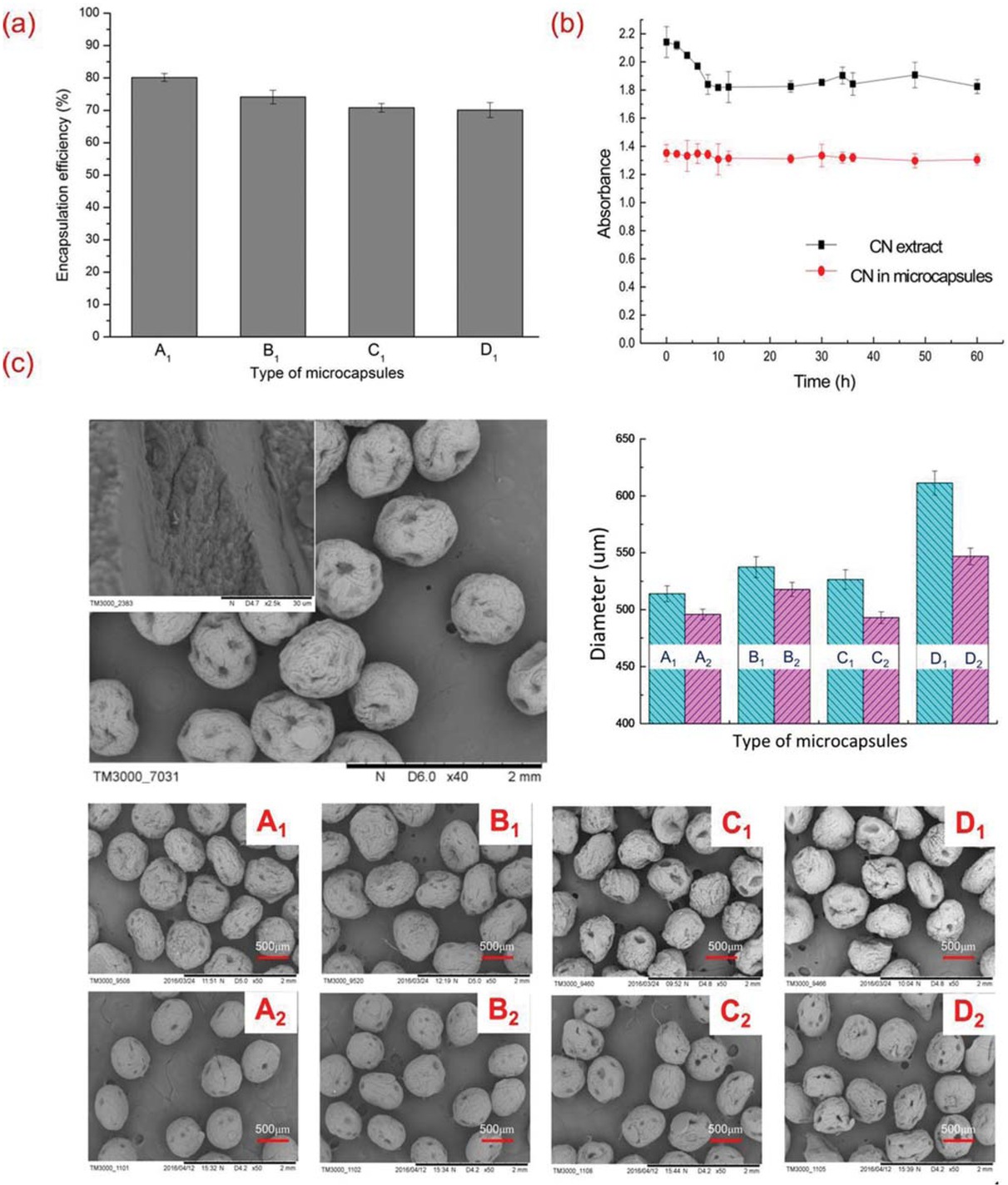

The encapsulation efficiency of CN is an important index for CN loaded microcapsules and is shown in Figure 2a. SA and chitosan provide essential basis in the shell formation of microcapsules. Insufficient SA or chitosan may lead to low shell strength, or even shell breakage under foreigner loads. However, excessive SA can increase viscosity of the Solution A and then decrease CN encapsulation efficiency. CaCl2 works as a curing agent and its lack will also cause shell softness, while rising amount can lead to thicker shell and less CN encapsulated. For the four optimized microcapsules by orthogonal method, they had encapsulation efficiencies of 80.16%, 74.21%, 70.79% and 70.11% for A1, B1, C1 and D1, respectively.

(a) Encapsulation efficiency of microcapsules; (b) Stability of microcapsules; (c) SEM images and average diameters of microcapsules.

Absorption intensity of CN after storage under -20°C for different intervals is shown in Figure 2b. Compared with fluctuant intensity of CN extract, CN in microcapsules kept almost stable and unchanged. It indicated that microcapsules could protect CN from degradation and destruction due to electrostatic attraction between SA and chitosan.

3.2 Physical characterization of microcapsules

Microcapsules were successfully prepared by the orifice granulation method. After adding SA solution into chitosan solution, the interface became thicker as the aggregation caused by electrostatic attraction between the negative charges on SA and the positive charges of chitosan. And the above rigid shell was able to protect core materials. Figure 2c shows the images of microcapsules with good monodispersity, together with surface details. The surface of microcapsules with CN encapsulated is porous, which allows the release of CN to the surrounding medium. Cross-section image shows obvious layers of cores and shells. Microcapsules with core materials have more pores on the surface compared with microcapsules without core materials. Besides, the roughness of microcapsules increases with the decrease of encapsulation efficiency from A1 to D1 (22). Besides, mean size of CN - SA/ chitosan microcapsules are larger than microcapsules without CN included.

Encapsulation of CN is qualitatively confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy in Figure 3a. In the FTIR spectrum of the pure CN, the peaks at 3457 cm-1, 3153 cm-1, 1722 cm-1 and 1617 cm-1 are attributed to stretching vibration of O-H, C-H, C=O and -C=C-, respectively. Peaks at 1326 cm-1, 1111 cm-1, 1039 cm-1 and 757 cm-1 are due to bending vibration of -CH3, C-O-C, C-N and ⌬, respectively. Compared with pure CN, the FTIR spectrum of the CN loaded microcapsules has peaks at 1326 cm-1, 1111 cm-1, 1039 cm-1 and 757 cm-1, which derive from the CN. Microcapsules without CN did not show any characteristic peaks of CN. According to the results of FTIR spectra analysis, CN loaded microcapsules were prepared successfully.

(a) FTIR spectroscopy of microcapsules; (b) XRD spectrum of microcapsules.

Figure 3b illustrates the changes in the intensity, height and weight of the reflection peak in CN extract and microcapsules. Sharp diffraction peak around 20° indicates high crystallinity and larger crystal size insideCN. Peaks around 20° in microcapsules confirmed the encapsulation of CN, while shorter ones indicated SA and chitosan in shells affected the original structure of CN. On one hand, SA and chitosan interacted with each other by electrostatic attraction. On the other hand, carboxyl of SA and amidogen of chitosan can bond with phenolic hydroxyl groups in CN, furtherly intervening with its crystal structures.

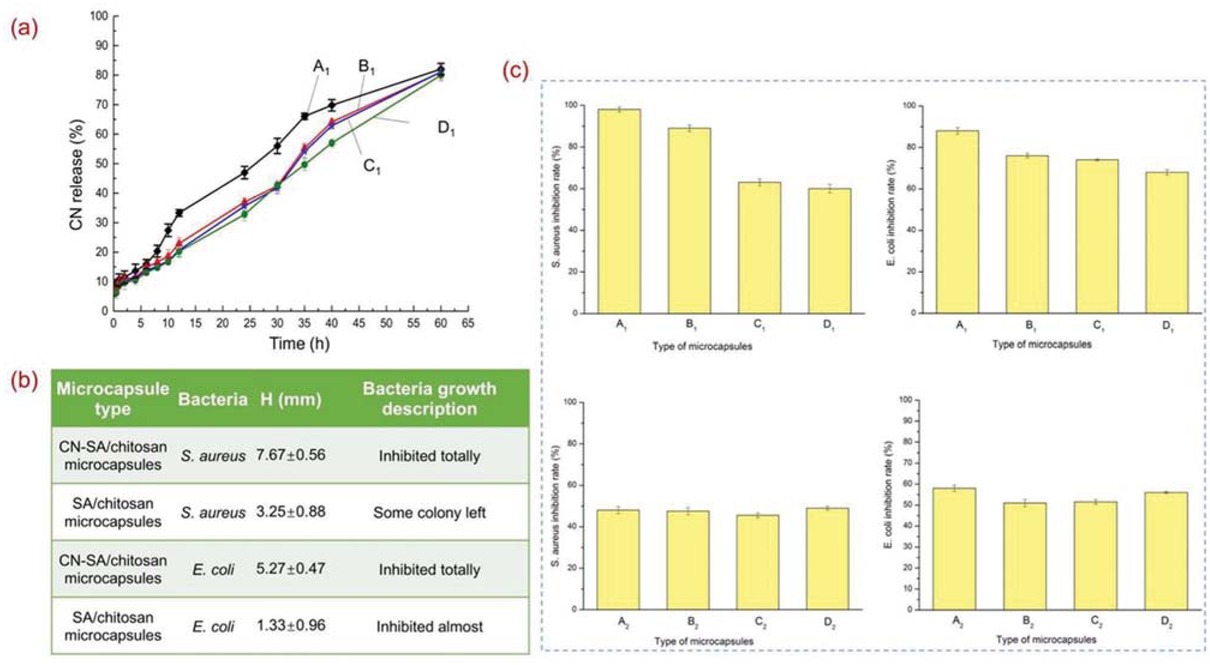

3.3 In vitro release

The release behaviors of CN from the microcapsules were investigated at pH = 7.7. Figure 4a gives a distinct picture of the release rate of CN. It was seen that the release of CN demonstrated a continuous and comparatively even process over the study period. The initial “burst release” was around 20% for B1, C1 and D1, and 35% for A1, which was very weak, during the first 12 h. It was primarily attributed to the protection of CN by shells. CN sustaining release reached the release proportions around 80% after 60 h. It is the basis of long-term durability of microcapsule antibacterial activity.

(a) CN release of microcapsules along with the time; (b) Microcapsule qualitative antibacterial activity; (c) Microcapsule quantitative antibacterial activity.

Acute wound healing process can be divided into four periods, among which inflammation phase is more likely to cause microorganism growth (23). In this period, the skin pH increases from 5-6 to 7 or more (24). In acid medium, the COO− groups in alginates transform into COOH groups. On the one hand, the hydrogen-bonding interaction among COOH groups is strengthened and the additional physical crosslinking is generated; on the other hand, the electrostatic repulsion among COO− group is restricted, and so the alginate shell tends to shrink. CN release from the core decreases (25). But partial chitosan degrades to defend microbes at the first stage. However, in inflammation stage, the skin pH increases in wounds and the ratio of COO− groups in polymer network increase. Consequently, the hydrogen-bonding interaction is broken and the electrostatic repulsion among negatively charged polymer chains increases, and so the polymer network tends to swell. Degraded chitosan also leads to more pores for CN release to kill the bacteria.

3.4 Microcapsule antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activity of microcapsules with CN loaded and unloaded against S. aureus and E. coli was investigated. The results (Figure 4b) revealed that CN-loaded microcapsules had strong antibacterial effects, with S. aureus inhibition zones of 7.67 mm and E. coli inhibition zones of 5.27 mm after incubation for 24 h. Microcapsules without CN encapsulation also illustrated antimicrobial property, with S. aureus inhibition zones of 3.25 mm and E. coli inhibition zones of 1.33 mm, which were the contributions of chitosan. In addition, it was observed that the antibacterial effect against E. coli was slightly weak compared to S. aureus. Quantitative evaluations (Figure 4c) also illustrated higher inhibition rates against S. aureus. Besides, antibacterial performance of microcapsules increased with the CN encapsulation rates, while microcapsules without CN performed similar inhibition rates. It confirmed the biocidal functions of CN. The inhibition rate could research 98.99% against S. aureus after 12 h and 100% after 24 h (Table S1) for microcapsule (A1) loading concentration of 4.5 mg/mL. It remained 99.61% against E. coli after 6 h and kept 100% after 12 h (Table S2) for 5.0 mg/mL, demonstrating a long-term antibacterial performance.

So, at the early stage of wound healing, chitosan in microcapsule shells plays the role to defend bacteria and help hemostatic. At inflammation stage, alginate networks swell with the increase of skin pH and partial chitosan degrades with pores left. Thus, more CN in the core release to defend microbe.

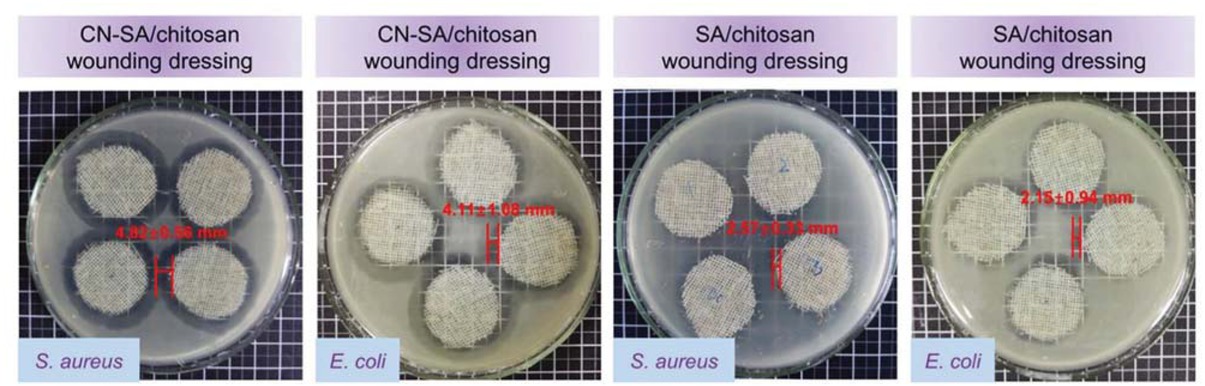

3.5 Wound dressing antibacterial properties

Antimicrobial performance of composite wound dressings was investigated and shown in Figure 5. CN loaded dressings have S. aureus inhibition zones of 4.82 mm and E. coli inhibition zones of 4.11 mm, while dressings without CN showed S. aureus inhibition zones

Wound dressing antibacterial properties.

of 2.57 mm and E. coli inhibition zones of 2.15 mm. Because of indirect CN contact with bacteria, wound dressings have inferior antimicrobials compared with microcapsules. According to ISO 20645:2004, they still showed good antibacterial effect. Moreover, cotton gauze on the outer layer works as wicking of excessive exudation. Alginates in the middle can fix antibacterial microcapsules, as well as provide a barrier for water vapor permeation by forming hydrogels through ionic exchange. The whole system works cooperatively to help wound healing.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the antibacterial performance of plant-derived CN and its incorporation in microcapsules. The obtained microcapsules had rough surfaces and high stability under -20°C. Besides, prominent antimicrobial effects of CN as well as its sustained release profile was observed. Chitosan in microcapsule shells can defend bacteria and help hemostatic at the early stage of wound healing. At the inflammation stage, alginate networks swell and degraded chitosan lead to more CN release to combat infections. Thus, the developed microcapsules with natural formed a biocompatible and long durability antibacterial system, which was promising in wound dressing applications.

Acknowledgement

The project is support by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant No. 2232017A-05, 2232018G-01), Science and Technology Support Program of Shanghai (grant No. 16441903803), the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (grant No. CUSF-DH-D-2017012), National Health and Family Planning Commission Fund (No. 2017ZX01001-S22) and 111 project (grant No. B07024).

Supplementary material: Figure S1 (a) The ultraviolet spectrum of CN in PBS (pH = 7.7); (b) CN concentration – absorption curve. Table S1 Inhibition rates of microcapsules against S. aureus. Table S2 Inhibition rates of microcapsules against E. coli.

Conflict of interest

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions: M. Z., F. W., J. G. and L. W. conceived and designed the experiments. W. X. and M. Z. performed the experiments including fabrication and analysis. W. X. wrote the paper.

References

1 Velnar T., Bailey T., Smrkolj V., The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res, 2009, 37(5), 1528-1542.10.1177/147323000903700531Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Unnithan A. R., Barakat N.A.M., Pichiah P.B.T., Gnanasekaran G., Nirmala R., Cha Y.S., et al., Wound-dressing materials with antibacterial activity from electrospun polyurethane–dextran nanofiber mats containing ciprofloxacin HCl. Carbohyd Polym, 2012, 90(4), 1786.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.071Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3 Liu J., Liu C., Liu Y., Chen M., Yang H., Yang Z., Study on the grafting of chitosan–gelatin microcapsules onto cotton fabrics and its antibacterial effect. Colloid Surface B, 2013, 109(9), 103-108.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.03.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Si Y., Zhang Z., Wu W., Fu Q., Huang K., Nitin N., et al., Daylight-driven rechargeable antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes for bioprotective applications. Sci Adv, 2018, 4(3), eaar5931.10.1126/sciadv.aar5931Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5 Palaniappan K., Holley R.A., Use of natural antimicrobials to increase antibiotic susceptibility of drug resistant bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 140(2), 164-168.10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.04.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Cisowska A., Wojnicz D., Hendrich A. B., Anthocyanins as antimicrobial agents of natural plant origin. Nat Prod Commun, 2011, 6(1), 149-156.10.1177/1934578X1100600136Search in Google Scholar

7 Dorman H., Deans S.G., Antimicrobial agents from plants: antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J Appl Microbiol, 2000, 88(2), 308-316.10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00969.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

8 Masood F., Polymeric nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery system for cancer therapy. Mat Sci Eng C, 2016, 60, 569.10.1016/j.msec.2015.11.067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9 Bharti C., Nagaich U., Pal A.K., Gulati N., Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in target drug delivery system: A review. Int J Pharm Investig, 2015, 5(3), 124-133.10.4103/2230-973X.160844Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10 Xue X., Zhao Y., Dai L., Zhang X., Hao X., Zhang C., et al., Spatiotemporal drug release visualized through a drug delivery system with tunable aggregation-induced emission. Adv Mat, 2014, 26(5), 712-717.10.1002/adma.201302365Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Vermonden T., Censi R., Hennink W. E., Hydrogels for Protein Delivery. Chem Rev, 2012, 112(5), 2853.10.1021/cr200157dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

12 Wang Q., Zhang J.P., Wang A.Q., Preparation and characterization of a novel pH-sensitive chitosan--poly (acrylic acid)/attapulgite/ sodium alginate composite hydrogel bead for controlled release of diclofenac sodium. Carbohyd Polym, 2009, 78(4), 731-737.10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.06.010Search in Google Scholar

13 Hu Y., Yang Y., Ning Y., Wang C., Tong Z., Facile preparation of artemisia argyi oil-loaded antibacterial microcapsules by hydroxyapatite-stabilized Pickering emulsion templating. Colloid Surface B, 2013, 112, 96-102.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.08.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Chen M., Hu Y., Zhou J., Xie Y., Wu H., Yuan T., et al., Facile fabrication of tea tree oil-loaded antibacterial microcapsules by complex coacervation of sodium alginate/quaternary ammonium salt of chitosan. RSC Adv, 2016, 6(16), 13032-13039.10.1039/C5RA26052CSearch in Google Scholar

15 Wang C.G., Chinese pulsatilla extracts eliminate resistance of Escherichia coli to streptomycin. Afr J Microbiol Res, 2011, 5(21), 81-4.10.5897/AJMR11.445Search in Google Scholar

16 Pithayanukul P., Nithitanakool S., Bavovada R., Hepatoprotective potential of extracts from seeds of Areca catechu and nutgalls of Quercus infectoria. Molecules, 2009, 14(12), 4987-5000.10.3390/molecules14124987Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Wang W., Wang A., Synthesis and swelling properties of pH-sensitive semi-IPN superabsorbent hydrogels based on sodium alginate--poly(sodium acrylate) and polyvinylpyrrolidone. Carbohyd Polym, 2010, 80(4), 1028-1036.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.01.020Search in Google Scholar

18 Gupta B., Arora A., Saxena S., Alam M.S., Preparation of chitosan&;ndash;polyethylene glycol coated cotton membranes for wound dressings: preparation and characterization. Polym Advan Technol, 2010, 20(1), 58-65.10.1002/pat.1280Search in Google Scholar

19 Zheng L.J., Luo Y.P., Wang Y.J., Xing-Guo H.U., Zhi-Qing W.U., Bao F.K., et al., Advances in the study of the antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action of Galla chinensis. Journal of Pathogen Biology, 2011, 6(11), 868-1105.Search in Google Scholar

20 Chen X., Hou D., Wang L., Zhang Q., Zou J., Sun G., Antibacterial Surgical Silk Sutures Using a High-Performance Slow-Release Carrier Coating System. Acs Appl Mater Inter, 2015, 7(40), 22394-22403.10.1021/acsami.5b06239Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Edwards J.V., Yager D. R., Cohen I.K., Diegelmann R.F., Montante S., Bertoniere N., et al., Modified cotton gauze dressings that selectively absorb neutrophil elastase activity in solution. Wound Repair Regen 2001, 9(1), 50.10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00050.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Zhang M., Rao B., Gao J., Wang F., Wang L., Wu J., et al., Preparation and structure research of gallnut antibacterial microcapsules. Industrial Textiles, 2016, 34(7), 28-34.Search in Google Scholar

23 Witte M.B., Barbul, A., General principles of wound healing. Surg Clin N Am, 1997, 77(3), 509.10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70566-1Search in Google Scholar

24 Schneider L.A., Korber A., Grabbe S., Dissemond J., Influence of pH on wound-healing: a new perspective for wound-therapy? Arch Dermatol Res, 2007, 298(9), 413-420.10.1007/s00403-006-0713-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Seeli D.S., Dhivya S., Selvamurugan N., Prabaharan M., Guar gum succinate-sodium alginate beads as a pH-sensitive carrier for colon-specific drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol, 2016, 91, 45-50.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Xue et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Polymers and Composite Materials / Guest Editor: Esteban Broitman

- A novel chemical-consolidation sand control composition: Foam amino resin system

- Bottom fire behaviour of thermally thick natural rubber latex foam

- Preparation of polymer–rare earth complexes based on Schiff-base-containing salicylic aldehyde groups attached to the polymer and their fluorescence emission properties

- Study on the unsaturated hydrogen bond behavior of bio-based polyamide 56

- Effect of different nucleating agent on crystallization kinetics and morphology of polypropylene

- Effect of surface modifications on the properties of UHMWPE fibres and their composites

- Thermal degradation kinetics investigation on Nano-ZnO/IFR synergetic flame retarded polypropylene/ethylene-propylene-diene monomer composites processed via different fields

- Properties of carbon black-PEDOT composite prepared via in-situ chemical oxidative polymerization

- Regular articles

- Polyarylene ether nitrile and boron nitride composites: coating with sulfonated polyarylene ether nitrile

- Influence of boric acid on radial structure of oxidized polyacrylonitrile fibers

- Preparing an injectable hydrogel with sodium alginate and Type I collagen to create better MSCs growth microenvironment

- Application of calcium montmorillonite on flame resistance, thermal stability and interfacial adhesion in polystyrene nanocomposites

- Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications

- Polycation-globular protein complex: Ionic strength and chain length effects on the structure and properties

- Improving the flame retardancy of ethylene vinyl acetate composites by incorporating layered double hydroxides based on Bayer red mud

- N, N’-sebacic bis(hydrocinnamic acid) dihydrazide: A crystallization accelerator for poly(L-lactic acid)

- The fabrication and characterization of casein/PEO nanofibrous yarn via electrospinning

- Waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s films as a sustained release system for ketoconazole

- Polyimide/mica hybrid films with low coefficient of thermal expansion and low dielectric constant

- Effects of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning process parameters on polymer nanofiber morphology and microstructure

- Stimuli-responsive DOX release behavior of cross-linked poly(acrylic acid) nanoparticles

- Continuous fabrication of near-infrared light responsive bilayer hydrogel fibers based on microfluidic spinning

- A novel polyamidine-grafted carboxymethylcellulose: Synthesis, characterization and flocculation performance test

- Synthesis of a DOPO-triazine additive and its flame-retardant effect in rigid polyurethane foam

- Novel chitosan and Laponite based nanocomposite for fast removal of Cd(II), methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution

- Enhanced thermal oxidative stability of silicone rubber by using cerium-ferric complex oxide as thermal oxidative stabilizer

- Long-term durability antibacterial microcapsules with plant-derived Chinese nutgall and their applications in wound dressing

- Fully water-blown polyisocyanurate-polyurethane foams with improved mechanical properties prepared from aqueous solution of gelling/ blowing and trimerization catalysts

- Preparation of rosin-based polymer microspheres as a stationary phase in high-performance liquid chromatography to separate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkaloids

- Effects of chemical modifications on the rheological and the expansion behavior of polylactide (PLA) in foam extrusion

- Enhanced thermal conductivity of flexible h-BN/polyimide composites films with ethyl cellulose

- Maize-like ionic liquid@polyaniline nanocomposites for high performance supercapacitor

- γ-valerolactone (GVL) as a bio-based green solvent and ligand for iron-mediated AGET ATRP

- Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process

- Preliminary market analysis of PEEK in South America: opportunities and challenges

- Influence of mid-stress on the dynamic fatigue of a light weight EPS bead foam

- Manipulating the thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of polydicyclopentadiene via tuning the stiffness of the incorporated monomers

- Voigt-based swelling water model for super water absorbency of expanded perlite and sodium polyacrylate resin composite materials

- Simplified optimal modeling of resin injection molding process

- Synthesis and characterization of a polyisocyanide with thioether pendant caused an oxidation-triggered helix-to-helix transition

- A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications

- Development of vegetable oil-based conducting rigid PU foam

- Conetworks on the base of polystyrene with poly(methyl methacrylate) paired polymers

- Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams

- Impact and shear properties of carbon fabric/ poly-dicyclopentadiene composites manufactured by vacuum‐assisted resin transfer molding

- Effect of resins on the salt spray resistance and wet adhesion of two component waterborne polyurethane coating

- Modifying potato starch by glutaraldehyde and MgCl2 for developing an economical and environment-friendly electrolyte system

- Effect of curing degree on mechanical and thermal properties of 2.5D quartz fiber reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Preparation and performance of polypropylene separator modified by SiO2/PVA layer for lithium batteries

- A simple method for the production of low molecular weight hyaluronan by in situ degradation in fermentation broth

- Curing behaviors, mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical analysis and morphologies of natural rubber vulcanizates containing reclaimed rubber

- Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method

- Application of antioxidant and ultraviolet absorber into HDPE: Enhanced resistance to UV irradiation

- Study on the synthesis of hexene-1 catalyzed by Ziegler-Natta catalyst and polyhexene-1 applications

- Fabrication and characterization of conductive microcapsule containing phase change material

- Desorption of hydrolyzed poly(AM/DMDAAC) from bentonite and its decomposition in saltwater under high temperatures

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of biomass and carbon dioxide derived polyurethane reactive hot-melt adhesives

- The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin

- High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells

- Rigid polyurethane/expanded vermiculite/ melamine phenylphosphate composite foams with good flame retardant and mechanical properties

- A novel film-forming silicone polymer as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids

- Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior

- Effect of salt and temperature on molecular aggregation behavior of acrylamide polymer

- Dynamics of asymmetric star polymers under coarse grain simulations

- Experimental and numerical analysis of an improved melt-blowing slot-die