Abstract

Open educational resources (OERs) have transformed access to educational materials by promoting open licensing and cost-free distribution. However, despite their potential to democratize education, systemic inequities in knowledge production, digital infrastructure, and institutional policies persist, disproportionately affecting low-income and marginalized communities. This study critically examines the historical development, regional disparities, and pedagogical implications of OERs, analyzing their alignment with equity-driven education models and principles of critical pedagogy. Findings reveal that high-income nations dominate OER content creation, reinforcing Western-centric epistemologies and excluding Indigenous and non-English perspectives. Regional initiatives, such as OER Africa and Red REA-LATAM, attempt to counterbalance these inequities; however, technological barriers, funding shortages, and restrictive licensing models limit their effectiveness. The study emphasizes the need for sustainable funding mechanisms, investment in digital infrastructure, and inclusive licensing policies to ensure OERs fulfill their transformative potential. Additionally, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence-driven adaptive learning platforms offer promising solutions for personalized, student-centered education, but require careful implementation to prevent reinforcing existing inequalities. This research advocates for a reimagined, participatory OER framework, ensuring equitable access, knowledge co-creation, and culturally relevant learning opportunities for all learners.

1 Introduction

Open educational resources (OERs) are a transformational educational force, creating greater access, cost savings, and collaborative teaching, learning, and research resources (Gulyamov, Yakubov, & Karakhodjaeva, 2024; Open Education Global, 2025; UNESCO, 2019; Yuan & Recker, 2015). Since the term was introduced by UNESCO in 2002, it has become a global campaign to democratize education by expanding access to teaching and learning materials through open licensing. However, even as it is much touted, regional contrasts, power asymmetries in knowledge creation, and obstacles to equitable access – including variations in institutional policies and licensing – continue to pose an intractable challenge. This article reviews the history of OERs and their impact on making higher education more accessible, examining regional disparities in access and the role of OERs in promoting equity and justice.

Specifically, this study explores the tensions around OERs, digital infrastructure, linguistic diversity, and institutional policies, pinpointing the socio-material constraints that must be overcome to realize OER’s full potential. While OERs offer much potential for inclusive and learner-centered education, their effectiveness depends on addressing gaps in technological access, content relevance, and teachers’ digital skills. Understanding these barriers is essential to establishing meaningful, sustainable efforts that foster equitable learning environments worldwide and in keeping with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Number 4 (SDG4), which focuses on ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning, aligning closely with efforts to enhance OERs (UNESCO, 2019).

Also, as global initiatives such as with the most recent Open Education Week (OEWeek) 2025 continue to expand, they serve as catalysts for advancing equity-driven OER adoption emphasizing thematic focus areas, including Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA), Indigenous Ways of Knowing, and Open Education Policies, align directly with the need for more inclusive, localized, and participatory educational frameworks, stressing the need to address regional disparities while fostering an open knowledge ecosystem. These initiatives reinforce the importance of collaborative knowledge-sharing and underscore the role of culturally responsive and sustainable practices in shaping the future of education. Integrating diverse perspectives and regional expertise, they help bridge systemic gaps, ensuring that OER adoption is contextually relevant and globally impactful (Open Education Global, 2025).

This research underlines how the benefits of OERs can change current teaching in openness, collaboration, and innovation. It helps to shift away from top-down delivery methods because OERs allow educators and learners to work closely together to co-construct knowledge as a community – more than just free resources. Only when there is some maturity in the digital infrastructure, copyright issues, quotas, and institutional resistance towards open licensing will OERs reach wider adoption. These challenges call for collaborative engagement by policymakers, educators, and technology developers in presenting sustainable, contextual, and accessible means of operating OER programs for diverse learning communities.

To this end, the current study has focused on global Open OERs to provide insights into how diversity in OERs may vary by other sociological perspectives and regional differences. It also investigates to what extent these tools illustrate critical sociological insights and advance transformative education. Specifically, it investigates the following questions:

How do OERs reflect sociological themes of power, equity, and justice?

Are OERs aligned with the principles of critical pedagogy in fostering transformative education?

2 Literature Review

2.1 Historical Development and Impact of OERs on Accessibility

The concept of OER has transformed the educational landscape by making education more accessible, affordable, and collaborative. According to UNESCO (2019), OER is: “learning, teaching, and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright but released under an open license that permits no-cost access, reuse, repurpose, adaptation, and redistribution by others” (para. 3). OER, a term coined by UNESCO in 2002, has since spread in an international movement designed to democratize access to education through freely available teaching and learning materials (Junasova, Rzeplinksi, & Alards-Tomalin, 2025). One of the significant benefits is that OERs can help foster more equitable access to education by reducing student costs (Hilton, Gaudet, Clark, Robinson, & Wiley, 2013). Hilton demonstrated that open textbooks significantly lower costs while maintaining or improving learning outcomes. Additionally, OERs enhance accessibility for students with disabilities by offering adaptable formats that cater to diverse learning needs (Zhang et al., 2020). Furthermore, OERs can improve the quality of learning by promoting interactive and student-centered pedagogy (Gulyamov et al., 2024; Yuan & Recker, 2015).

A fundamental aspect of OERs is flexibility, encapsulated in Wiley’s (2014) 5R framework: Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute – which enables educators and learners to modify and share resources to fit specific learning contexts (Wiley, 2014). The adaptability of OERs allows for innovation in teaching, making it possible to customize educational materials for diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Dutra, Chee, & Clochesy, 2023). With the increasing advocacy for open-access education, global initiatives such as the Open e-Learning Content Observatory Services have played a key role in promoting OER adoption. Addressing the challenges of OERs that promote social equality for all citizens worldwide requires a multifaceted approach, including investments in digital infrastructure, capacity-building initiatives for educators, and policies that encourage the development and dissemination of regionally relevant OER materials (Forehand, 2024).

2.2 Regional Disparities in Sociological Perspectives on Education

2.2.1 The Intersection of Education, Power, and Knowledge Production

The fundamental processes of education, authority, and knowledge creation develop a critical framework for understanding the importance of OERs. Traditionally, educational resources have been controlled by commercial publishers, meaning that unequal access to knowledge is contingent upon the resources available. This centralization of resource control has often disenfranchised certain communities and limited their opportunities for equitable education (Semjén, Le, & Hermann, 2018). OERs interrupt this model by decentralizing access to educational resources and making them freely available to a wider audience. Removing cost barriers, OERs enable more inclusive education, allowing learners from diverse socio-economic backgrounds to access better resource materials, thereby creating a more democratic knowledge economy (Inefuku, 2017).

OERs hold the potential to address these challenges. Still, some researchers caution that the transition to open resources alone may not address structural inequities in education that have deep roots (Harvey & Bond, 2022). While OERs can increase access to content, they do not alter the power relations within educational systems. To make meaningful progress toward educational equity, a more comprehensive approach is necessary to address systemic inequities embedded in educational systems, including the processes by which knowledge is produced, valued, and disseminated. Unless these broader structural challenges are addressed, the fear of the shift to OERs may produce only modest gains in delivering authentically equitable learning results.

2.2.2 Equity and Justice in Educational Resource Development

The sociopolitical roots of OERs are deeply intertwined with broader movements advocating for educational equity, open access, and the democratization of knowledge. The issues of accessibility and fairness in allocating educational resources remain slippery subjects within the movement. OERs facilitate the democratization of education by making learning opportunities available to everyone, regardless of income (Giacomazzi, Fontana, & Camilli Trujillo, 2022). However, the actual impact of OER on student learning outcomes varies. Some research suggests positive effects on student performance (Griffiths, Mislevy, & Wang, 2022). Colvard, Watson, and Park (2018) also found that students using OERs performed on par with or better than traditional textbooks. On the other hand, if OERs are appropriate, they can lead to better learning experiences and outcomes (Colvard et al., 2018). In contrast, other studies have reported no impact on student academic performance (Fortney, 2021).

2.3 Critical Pedagogy and Open Education

2.3.1 The Transformative Potential of OERs Through a Freirean Lens

Critical pedagogy is a powerful heuristic that examines the influence of OERs in fostering transformative learning experiences. Freire’s (1970) notion of education as a practice of freedom aligns with the core tenets of open education – the development of critical consciousness, empowerment, and dialogue (Freire, 1970). OERs can enable students and educators to critically engage with content and query dominant narratives while creating more equitable learning environments by providing unfettered access to knowledge (Giroux, 2020) and so have the potential to disrupt traditional educational hierarchies. This ties to the broader aim of critical pedagogy, which seeks to achieve social justice and empower oppressed voices through education. As a result, OERs are a valuable tool for democratizing knowledge.

However, incorporating critical pedagogy principles in designing and implementing OERs does not come without challenges. However, institutional resistance towards using OERs in critical curriculum designs may hinder their adoption among educators and students, especially in traditional education systems where the norms/fundamental principles shape technology/networking. Critical pedagogy calls for more holistic and student-centered practices, which may conflict with the institutionalized and top-down domains of teaching and learning (Hooks, 1994). In addition to making OERs more widely available and accessible, faculty may require additional training in critical pedagogical techniques to challenge power dynamics and empower others through their use of OERs (Farrow, 2017). To overcome these barriers, institutional policies need to be created that facilitate critical pedagogy and OERs as complementary approaches to achieving educational equity, and professional development must be provided to educators.

2.3.2 Challenges in Embedding Critical Pedagogy Principles in OERs

While there is alignment between OER and critical pedagogy, there are challenges to realizing OER’s liberatory potential. Many OER initiatives are driven by market rather than pedagogical motivations, potentially stymying their ability to be agentic within such a framework (Florencio-Wain, 2024). In addition, the Global North produces the bulk of OER content, causing issues of epistemic injustice and marginalization of many voices and approaches (Karakaya & Karakaya, 2020). To address these issues, programs should emphasize localized knowledge generation, ensure diverse authorship, and adopt pedagogies that promote critical engagement with content. Such measures are critical in fostering more inclusive, egalitarian, and transformative learning realities across diverse contexts.

2.4 Global Disparities in OER Development and Use

2.4.1 How Different Regions Prioritize Sociological Themes in Educational Content

The theorization and institutionalization of OERs differ widely globally, and it is necessary to consider cultural, political, and socio-economic contexts. At times, a focus is on Sociological phenomena that reflect local challenges and issues in instructional material development. On other occasions, structural hurdles, for example, insufficient finance or infrastructure, make implementation complex (Apple, 2018). The contexts where OERs are made are also important; they inform what goes into the content and how knowledge is represented. Weller (2014) noted that these discrepancies can produce unequal embodiments of minority voices within the media (including instructional materials) presented to students (Weller, 2014).

This point leads to the question of how to meet these challenges, starting with the acceptance that OERs manifest a range of perspectives and worldviews that reflect the local knowledge and lived experience of diverse peoples and communities. This approach involves recognizing the need for cultural sensitivity and collaborating with the local community to ensure educational materials are co-created to be true to their lived experience. This ensures equitable access to education across diverse learning backgrounds (Tariq, 2024). Such a move toward inclusivity and contextuality is necessary for global educational equity in marginalized populations, for example (Dutra et al., 2023; Leask, 2015).

2.4.2 Case Studies of Countries With Strong OER Initiatives vs Those With Limited Access

The case studies on countries such as the Netherlands and South Korea with strong OER programs provide valuable lessons for government-led policies that encourage the widespread adoption of OERs (Mays, Aluko, & Combrinck, 2020; Open Education Global, 2025; Schuwer & Janssen, 2018). Strong national policies, institutional support, and established digital infrastructure in these countries have laid the groundwork for implementing OERs in various settings. By contrast, countries in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions face significant challenges, including poor infrastructure, limited funds, and untrained teachers (Kwarteng, 2021). This discrepancy heightens the importance of developing inclusive strategies, including international collaboration and financial support, to close the divides and facilitate more equitable access to OERs worldwide (Open Education Global, 2025).

OERs can significantly change education, potentially overcoming social and resource barriers and allowing knowledge to be distributed more evenly than previously thought possible (Cubides, Chiappe, & Ramirez-Montoya, n.d.). OERs can facilitate innovative pedagogical practices and enhance learning outcomes, especially for disadvantaged groups, courtesy of free and open access to high-quality teaching and learning materials (Dutra et al., 2023). Nonetheless, regional variation, institutional inertia, and unclear effects on student achievement stand as significant obstacles to the wide adoption of this reform. Although research is contained about the factors needed for OERs to deliver its promise of enhancing access to resources for everyone, it does not correlate linearly where more access to content leads to greater learning, which underlines the necessity for a more targeted, localized approach to the deployment of OERs (Dutra et al., 2023; Gulyamov et al., 2024; Yuan & Recker, 2015).

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Design

This study employs a qualitative content analysis approach (Komor & Grzyb, 2023; Özden, 2024) to examine the representation of sociological themes in OERs, focusing on power, equity, and justice within global educational materials. Qualitative content analysis is well-suited for investigating textual, visual, and structural elements in educational resources, allowing for a systematic interpretation of how sociological narratives are embedded in OERs (Özden, 2024). This method facilitates the identification of underlying ideological frameworks, knowledge hierarchies, and regional disparities in the design, accessibility, and pedagogical approaches of OERs. For example, a qualitative content analysis of OER history textbooks may reveal Eurocentric narratives that marginalize Indigenous knowledge systems, whereas resources from Latin American or African initiatives may emphasize decolonial perspectives, illustrating how power structures shape knowledge representation and access (Bernard, 2024; Weaver, 2023).

Given the study’s emphasis on comparative analysis, the research design integrates a cross-regional examination of OER repositories, contrasting content from high-income nations with materials from resource-constrained educational settings (Ochieng & Gyasi, 2021; UNESCO, 2019). In analyzing how open-access educational materials engage with issues of educational justice, this study aims to critically assess whether OERs function as tools for democratizing knowledge or perpetuating existing structural inequalities (Katz & Van Allen, 2022; Lourenço, Oliveira, & Tymoshchuk, 2024). Identifying disparities in content representation, accessibility, and institutional control, the comparative analysis underscores the impact of structural limitations that hinder equitable knowledge production and informs strategies for developing more inclusive, contextually relevant OERs (Bernard, 2024; Seiferle-Valencia, 2021).

Moreover, a qualitative, comparative approach was adopted to examine how OERs reflect critical pedagogy and social justice principles across diverse geopolitical, economic, and institutional contexts (Freire, 1970; Katz & Van Allen, 2022; Naeem, Ozuem, Howell, & Ranfagni, 2023). This method identified structural disparities in OER funding, policy support, and technological accessibility, which shape the global production and distribution of open-access educational materials (Lochmiller, 2021). Instead of assuming OERs are inherently democratizing, this analysis interrogates whether these resources function as tools of knowledge equity or inadvertently perpetuate existing educational asymmetries.

3.2 Selection Criteria for OERs

The study draws upon a diverse selection of OER repositories and databases, chosen based on their global reach, subject diversity, and institutional credibility. The primary sources include globally recognized repositories such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) OpenCourseWare, OER Commons, UNESCO OER, OpenLearn (UK Open University), MERLOT, and OpenStax (Rice University), along with the African Virtual University (OER Africa), which represents a regionally focused OER initiative. Additionally, other regionally significant open-access platforms, such as the Latin American OERs Network (Red de Recursos Educativos Abiertos de América Latina, Red REA-LATAM), which provides open-access educational materials tailored to the Latin American region, were included to ensure a broad and representative dataset.

These repositories were selected due to their subject coverage, accessibility, and influence on open education initiatives (Drumond, Méxas, & Meza, 2024; Lochmiller, 2021). Incorporating both multinational and regionally focused OER sources enables an accurate analysis of disparities in content representation, pedagogical structures, and sociological engagement across different educational systems. Each platform provides distinct advantages in understanding the interplay of open-access education, sociological themes, and critical pedagogy. Appendix A provides an overview of each platform’s classification, pedagogical approach, accessibility features, and support for global equity and inclusion.

MIT OpenCourseWare is a university-hosted platform that offers free course materials from the MIT. It primarily features STEM-focused content, structured as university-style coursework. As one of the most well-known OER initiatives, it has expanded access to high-quality educational resources worldwide. The platform’s structured approach mirrors conventional higher education models, making it a valuable case study in understanding how institutional knowledge is disseminated through open-access frameworks. However, despite its accessibility, MIT OpenCourseWare largely follows a traditional lecture-based format, which may limit its alignment with participatory, learner-centered approaches to education (MIT, n.d.).

OER Commons functions as a global aggregator of OERs contributed by educators worldwide. Unlike single-institution platforms, it allows curating diverse educational materials across multiple disciplines and pedagogical styles. Its flexible licensing models and broad institutional backing make it a vital tool in analyzing how OERs can be adapted to various educational settings. However, the quality and rigor of materials vary widely due to the open-contribution model, highlighting the challenge of maintaining consistent academic standards within open education (Watson et al., 2023).

UNESCO OER is a globally recognized digital repository supported by UNESCO that fosters international collaboration on open education. By prioritizing equity and multilingual access, UNESCO OER is a critical resource for examining how global education policies influence knowledge-sharing practices. The platform also underscores the role of international governance structures in shaping educational content, providing insights into the intersection of policy, access, and education justice (UNESCO, n.d.-a).

OpenLearn, hosted by the UK Open University, is a self-paced learning platform providing structured, freely accessible courses. Unlike other OER repositories, OpenLearn offers interactive and modular content, making it a valuable case for examining how OERs can promote independent learning. However, despite its accessibility, OpenLearn materials remain predominantly in English, presenting limitations for non-English-speaking learners (Open University, n.d.).

MERLOT is a curated OER repository developed by the California State University system, featuring faculty-contributed educational content. This platform provides an extensive collection of discipline-specific materials, particularly useful for evaluating how OERs support professional and higher education. However, MERLOT’s focus on faculty contributions means that student-generated content and interactive learning components are less prominent, potentially limiting its alignment with participatory learning models (California State University, n.d.).

OpenStax, a Rice University initiative, provides free, peer-reviewed academic textbooks, making it a valuable reference for assessing affordability and accessibility in formal education settings. The platform’s commitment to high-quality, research-backed content ensures credibility, but its emphasis on textbook-based learning may not fully support dynamic, student-centered pedagogies. Nonetheless, OpenStax has been instrumental in reducing financial barriers for students, making it a key player in discussions on OER equity and accessibility (Rice University, n.d.).

The African Virtual University (OER Africa) is a regionally focused platform that supports African learners by integrating Indigenous knowledge systems. This initiative emphasizes the challenges of digital access and funding constraints while offering an example of localized knowledge production within OER frameworks. OER Africa plays a crucial role in broadening perspectives within open education, countering the dominance of Western-centric educational paradigms. However, despite its efforts to promote inclusivity, the platform faces limitations regarding technological infrastructure and funding (Saide, n.d.).

Red REA-LATAM provides Spanish- and Portuguese-language educational content, emphasizing linguistic inclusivity and regional adaptation in OER implementation. As one of the few Latin America-centered platforms, it is a case study of how regional OER initiatives address sociological disparities in educational access. In prioritizing locally relevant educational materials, Red REA-LATAM offers a model for culturally responsive open education, yet challenges remain in scaling up its reach beyond its primary linguistic communities (Red REA-LATAM, n.d.).

Through these selection criteria, the study evaluates how OERs frame sociological themes within diverse educational contexts (Drumond et al., 2024; Ochieng & Gyasi, 2021). In comparing global repositories with regionally focused initiatives, this approach accentuates power asymmetries in knowledge production while identifying equitable models for open-access dissemination (Katz & Van Allen, 2022; Lourenço et al., 2024). Furthermore, it provides a critical lens on how socio-political and economic structures influence the accessibility and adaptability of OERs across different educational landscapes (Bernard, 2024; Moges, Assefa, Tilwani, Desta, & Shah, 2023; Weaver, 2023).

3.3 Framework for Analysis

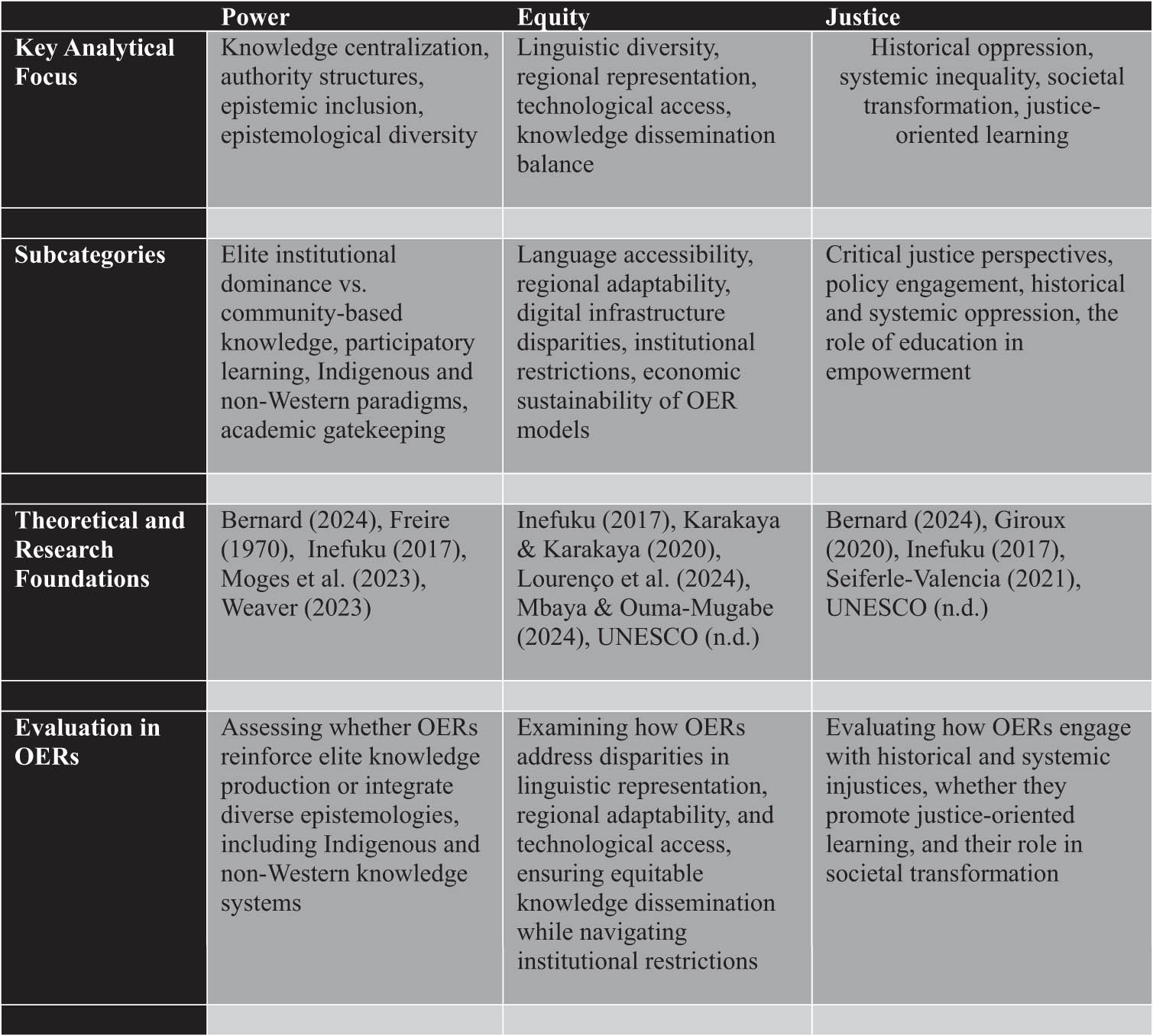

To systematically examine how OERs engage with sociological themes, the study employed a structured coding scheme utilizing thematic coding and critical discourse analysis. The coding framework was designed to assess three primary sociological categories – power, equity, and justice – alongside subcategories informed by critical pedagogy and global education equity frameworks (Freire, 1970; Lourenço et al., 2024; Seiferle-Valencia, 2021). This approach ensures a multidimensional examination of how knowledge dissemination, content organization, and pedagogical strategies within OERs reflect broader power dynamics, structural inequities, and justice-oriented learning practices. The analysis considered textual and visual content and the organizational structure of OER materials, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of how educational narratives are framed within open-access contexts.

The power dimension of the analysis evaluated how authority, expertise, and knowledge validation are structured in OERs. This included examining whether knowledge production was centralized within elite academic institutions or whether community-based, Indigenous, and non-Western perspectives were incorporated (Bernard, 2024; Moges et al., 2023; Weaver, 2023). The study also assessed the extent to which OERs positioned learners as passive recipients of knowledge versus active contributors, reflecting the hierarchical or participatory nature of open-access materials. The equity dimension focused on language accessibility, regional representation, and learner agency, determining whether OERs effectively addressed disparities in educational access and content adaptation (Karakaya & Karakaya, 2020).

Special attention was given to linguistic diversity and regional adaptability, as these factors significantly ensure that OERs reach diverse learning communities and do not reinforce existing educational divides. The justice dimension analyzed how OERs engaged with themes of historical oppression, systemic inequality, and the role of education in societal transformation (Giroux, 2020). In identifying the extent to which OERs incorporate critical perspectives on justice, this study evaluates whether these resources truly function as tools for educational empowerment or remain embedded in dominant ideological structures. In critically assessing these dimensions, this research highlights the potential for OERs to serve as catalysts for inclusive and transformative education.

Finally, epistemological diversity was examined relative to OER pedagogy, evaluating whether these resources integrate Indigenous knowledge systems, non-Western educational paradigms, and community-driven learning models. In assessing how OERs amplify or marginalize alternative ways of knowing, this study interrogates whether open-access resources genuinely disrupt academic gatekeeping or continue to reflect dominant knowledge hierarchies (Bernard, 2024; Moges et al., 2023; Weaver, 2023). Recognizing these disparities in accessibility, the study evaluates how OER platforms negotiate the balance between institutional restrictions and equitable knowledge dissemination (Inefuku, 2017).

In integrating sociological content analysis with pedagogical evaluation, this study moves beyond conventional accessibility metrics, instead interrogating how power operates within open education frameworks (Katz & Van Allen, 2022; Seiferle-Valencia, 2021). Rather than claiming that OERs are inherently equitable, the findings assess whether these resources genuinely foster critical, justice-oriented learning experiences and provide meaningful opportunities for educational empowerment across diverse contexts (Lourenço et al., 2024; Ochieng & Gyasi, 2021). Through this dual-level analysis, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of the sociopolitical dimensions of OERs, offering insights into strategies for making open-access resources more inclusive, participatory, and representative of diverse ways of knowing (Bernard, 2024; Moges et al., 2023; Weaver, 2023).

4 Findings and Analysis

4.1 Representation of Sociological Themes in OERs

While OERs have emerged as a potential equalizing force in global education, disparities persist in how power, equity, and justice are framed within these materials. OER platforms expand access, but as reflected in Appendix A, their institutional structures, content models, and licensing frameworks determine the extent to which they democratize knowledge or reinforce existing hierarchies (Tlili et al., 2022). In high-income nations, repositories such as MIT OpenCourseWare, OpenStax, and MERLOT reflect elite institutional knowledge production, often emphasizing STEM disciplines and traditional academic frameworks (Abelson, 2008; Flinn & Openo, 2024). These repositories, though publicly accessible, maintain conventional educational paradigms, raising concerns about knowledge centralization and epistemic exclusion (Wilcox & Lawson, 2022). Figure 1 shows a comparative representation of sociological themes in OER platforms.

Comparative representation of sociological themes in OERs. Note. This compares sociological themes in OERs across three dimensions – power, Equity, and Justice – examining the dynamics of knowledge centralization, accessibility, linguistic diversity, historical oppression, and justice-oriented learning.

In contrast, regionally focused repositories, such as the African Virtual University (OER Africa) and Red REA-LATAM, provide linguistically and culturally responsive content, integrating Indigenous knowledge systems and localized curricula (Letsoalo, 2024; Mosquera, Días, Lozada, & Cuichán, 2024). These repositories emphasize the importance of situated knowledge by ensuring that educational materials are accessible in multiple languages and reflective of regional educational priorities, addressing historical exclusions and linguistic barriers (Tepe, Verchier, & Kokou, 2024). However, despite these efforts, several challenges persist.

A primary issue is the disparity in resource allocation and funding mechanisms that inhibit the scalability of these platforms. Limited governmental and institutional support in some regions exacerbates the challenge, resulting in an uneven distribution of high-quality OER across different communities (Mbaya & Ouma-Mugabe, 2024). While international collaborations have facilitated the expansion of OER initiatives, the reliance on external donors and foreign institutions has led to concerns about sustainability and local autonomy in content development (Letsoalo, 2024).

Additionally, technological infrastructure gaps remain a significant constraint. For example, rural and marginalized areas experience challenges accessing digital repositories due to inconsistent internet connectivity, limited access to digital devices, and insufficient digital literacy training (Mosquera et al., 2024). In Latin America, for example, Red REA-LATAM has attempted to bridge these divides by developing low-bandwidth versions of its repository and implementing offline access strategies. Nevertheless, technological infrastructure disparities still hinder OER’s equitable use (Mosquera et al., 2024). Similarly, in Africa, the African Virtual University has developed partnerships to provide offline learning materials, but the reach of these initiatives remains constrained by financial and logistical limitations (Tepe et al., 2024).

Beyond technological limitations, sociopolitical factors also shape the adoption and impact of regional OER repositories. In some cases, educational policies and regulatory frameworks fail to recognize or incentivize the use of OERs, leading to institutional reluctance to integrate these materials into mainstream curricula (Mbaya & Ouma-Mugabe, 2024). Furthermore, concerns over the quality assurance of OERs, particularly in highly specialized or technical fields, pose additional barriers to widespread adoption (Tepe et al., 2024). Resistance from traditional publishing industries, which view OERs as a threat to commercial educational materials, further complicates efforts to promote open-access learning. Additionally, varying levels of digital literacy among educators and learners can influence the effective utilization of OERs, potentially exacerbating existing educational inequities (Dickson & Holm, 2022; Otto, 2019).

Despite these challenges, regionally focused OER repositories continue to play a central role in fostering inclusive education by centering local knowledge, promoting linguistic diversity, and mitigating some of the systemic barriers to educational equity. Future efforts should prioritize sustainable funding mechanisms, enhanced digital infrastructure, and stronger policy advocacy to ensure that regional OER initiatives can fulfill their potential as transformative educational tools. Additionally, OER platforms differ in their commitment to social-justice-oriented frameworks. UNESCO OER, for example, positions open access as a fundamental educational right, embedding policy-driven initiatives that promote knowledge equity (Ossiannilsson, Cazarez, Goode, Mansour, & Gusmao, 2024; UNESCO, n.d.-a, -b, -c). However, even within these global repositories, dominant narratives often marginalize non-Western perspectives, illustrating the complex interplay between global policy and localized educational realities (Francis, Hill, & Overmier, 2022).

4.2 Critical Pedagogy in OERs

A core challenge in OER development lies in its alignment with critical pedagogy, particularly its emphasis on dialogic learning, student agency, and transformative education (Freire, 1970; Katz & Van Allen, 2022). While open-access models theoretically encourage participatory learning, a deeper examination of major repositories reveals varying degrees of engagement with Freirean pedagogical principles. Freirean pedagogy advocates for problem-posing education, where learners construct meaning through critical reflection and dialogue (Freire, 1970). This framework emphasizes the co-construction of knowledge, where the power dynamic between educators and learners is dismantled, fostering an environment of mutual learning and empowerment (Katz & Van Allen, 2022). Furthermore, it underscores the role of education as a tool for social transformation, challenging oppressive structures and equipping learners with the critical consciousness needed to interrogate and reshape their realities. Some platforms actively promote student-centered learning, while others reinforce conventional academic hierarchies, limiting their potential to drive social transformation.

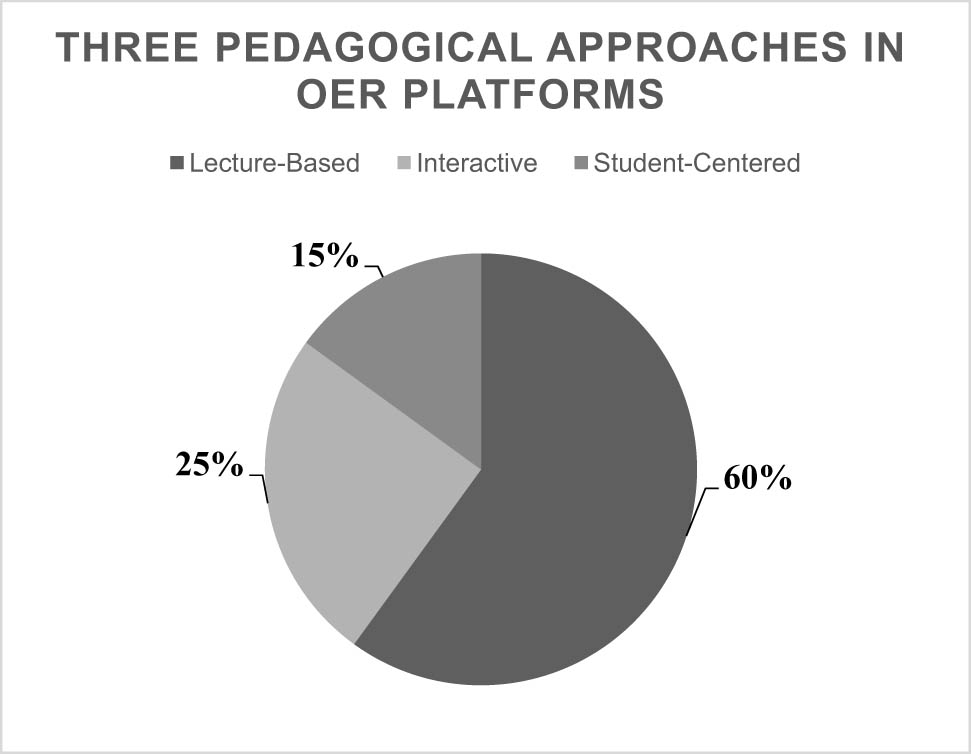

Three primary pedagogical approaches emerge in many OER: lecture-based, interactive, and student-centered. As illustrated in Figure 2, approximately 60% of OERs lean toward a traditional, lecture-based model in which information primarily flows in one direction, from instructor to learner. Meanwhile, around 25% of these materials incorporate interactive features – such as quizzes, simulations, or discussion prompts – to engage learners more actively. Lastly, 15% of OERs emphasize a student-centered design where learners exercise greater agency in constructing their knowledge, often via collaborative or inquiry-driven methods. These proportions point to a prevalent reliance on didactic content within OER platforms while underscoring the potential growth area for interactive and student-centered models that draw on critical pedagogy and foster deeper learner engagement (Chan, Wong, Lohana, Mitra, & So, 2024; Freire, 1970; Navarra-Madsen, 2024; Priya & Senthilnathan, 2024; Qu, 2023; Rosenberg, 2023; Tlili et al., 2022).

OER pedagogical models. Note. Illustrates a predominance of lecture-based designs in many open educational materials, with interactive and student-centered approaches representing smaller – but still significant – portions of OER pedagogy.

Though providing high-quality, structured content, repositories such as MIT OpenCourseWare and OpenStax primarily adhere to a university-structured, lecture-based model (MIT, n.d.; Navarra-Madsen, 2024). Since these platforms significantly contribute to widening educational access, they do so within traditional academic frameworks that position students as passive recipients of information rather than as co-creators of knowledge (Qu, 2023). The linear, instructor-led nature of these OERs often lacks interactive components that foster critical inquiry, peer collaboration, and knowledge co-construction. Without student input or real-time engagement mechanisms, such resources risk reinforcing hierarchical knowledge dissemination rather than challenging it through participatory dialogue and critical reflection. The absence of learner-driven content adaptation further limits the applicability of these OERs in diverse sociopolitical and cultural contexts, underscoring the need for more flexible and collaborative learning models.

In contrast, OER Commons and MERLOT function as educator-curated platforms, offering greater adaptability and customization (Chan et al., 2024; Rosenberg, 2023), aligning more closely with critical pedagogy, allowing educators to modify and contextualize resources, and fostering student engagement and localized learning (Priya & Senthilnathan, 2024). The ability to edit, remix, and tailor content enables educators to integrate culturally relevant materials and interactive methodologies that empower students as active participants in the learning process. However, their open-contribution models introduce content consistency and pedagogical coherence challenges, often leading to variability in resource quality and reliability (Sergiadis, 2024). Some materials lack rigorous peer review, resulting in a fragmented knowledge base where the effectiveness of resources is contingent upon the expertise of the contributors, pointing out a fundamental tension in OER development – balancing the need for inclusivity and adaptability with the necessity of maintaining high academic standards and instructional quality.

Significantly, the African Virtual University and Red REA-LATAM have pioneered efforts to embed participatory and community-driven learning approaches, incorporating multilingual content, Indigenous epistemologies, and collaborative knowledge production (Adekanmbi, 2021; Mazouz & Khalida, 2024). These platforms challenge Western-dominated narratives in education by foregrounding local knowledge systems and encouraging learner-centered exploration. Unlike static repositories, they facilitate interactive engagement, where students collectively contribute to and refine knowledge, aligning with Freire’s call for education as a means of social transformation and fostering critical consciousness among learners. However, despite these advances, funding shortages and technological constraints continue to hinder the scalability and sustainability of these initiatives (Sylla, Mbatchou Nkwetchoua, & Bouchet, 2022). The lack of consistent financial support and limited infrastructure – such as broadband access and digital literacy programs – creates barriers to broader participation, disproportionately affecting historically marginalized communities.

Moreover, while some OERs promote student-led inquiry and dynamic interaction, many remain restricted by licensing structures and institutional control. For example, Creative Commons licenses vary in flexibility, with some restricting modifications or requiring attribution that limits free adaptation for localized learning (Tlili et al., 2022), presenting a paradox in open education. Although OERs are designed to be freely accessible, the degrees of openness vary significantly, affecting how learners and educators can actively shape and repurpose content. Addressing these limitations requires focused and intentional shifts in policy, funding allocation, and digital infrastructure development to create OER ecosystems that are accessible and transformative. Appendix A shows a breakdown of some OER platform characteristics.

Future efforts in OER development must move beyond mere content dissemination toward fostering interactive, socially responsive learning experiences. Expanding learner agency through co-creation mechanisms – such as student-authored content, community-led peer review, and interactive feedback systems – can help bridge the gap between access and empowerment. Furthermore, integrating emerging digital tools such as AI-driven content customization and adaptive learning technologies can enhance the responsiveness of OERs to diverse learner needs, ensuring that critical pedagogy principles are not merely aspirational but actively embedded within open education frameworks (Open Education Global, 2025).

Accordingly, the potential of OERs to serve as vehicles for transformative education hinges on their ability to transcend rigid academic structures and embrace participatory, dialogic, and justice-oriented pedagogies (Bernard, 2024; Freire, 1970). Without a deliberate commitment to fostering student agency and equity-driven content creation, OERs risk replicating the educational inequities they seek to address. Therefore, the next phase of OER evolution must prioritize broader access and the cultivation of pedagogical practices that genuinely empower learners to challenge, critique, and reconstruct knowledge in ways that align with their lived experiences and social realities.

4.3 Global Disparities in OER Content

The geographical and socio-political contexts in which OERs are produced profoundly shape their accessibility, content diversity, and pedagogical approaches (Knight, 2024). While OERs are intended to democratize education, the structural inequalities embedded within global knowledge production continue to hinder equitable participation. With their advanced technological infrastructure and institutional support, high-income nations dominate OER creation, whereas lower-income regions struggle with systemic barriers that restrict widespread adoption, adaptation, and localization (Knight, 2024). These disparities raise critical concerns about whether OERs genuinely contribute to global education equity or inadvertently perpetuate existing hierarchies.

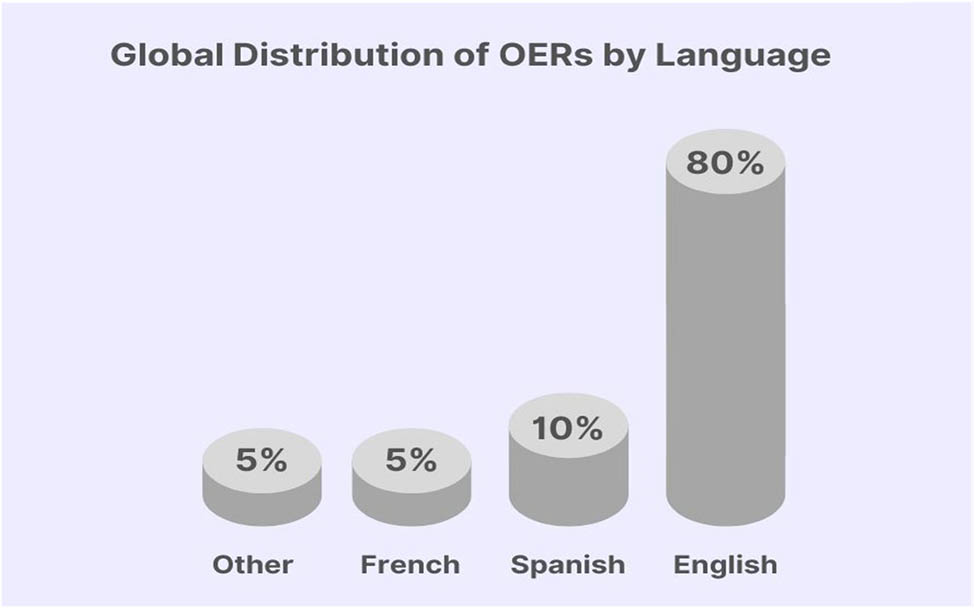

One of the most pronounced disparities in OER content is language accessibility. Major platforms such as MIT OpenCourseWare, OpenStax, and MERLOT primarily deliver content in English, thereby excluding large populations of non-English-speaking learners from equitable participation in open education (Abelson, 2008; Thiruppathi & Muthumani, 2024). While repositories such as UNESCO OER and OpenLearn attempt to address linguistic inclusivity by offering multilingual content, the volume and quality of non-English resources remain disproportionately low (Law & Storrar, 2024; Santos-Hermosa, 2024). Figure 3 shows a representation of the global distribution of OERs by language, for example.

Hence, this linguistic hegemony reinforces Western-centric knowledge structures, positioning English as the dominant language of academic discourse and limiting the reach of OERs in regions where local and Indigenous languages are the primary medium of education. Although initiatives such as Red REA-LATAM and OER Africa have made strides in developing regionally relevant materials in Spanish, Portuguese, and African languages, the lack of funding and institutional support continues to hinder large-scale multilingual resource development (George-Reyes, López-Caudana, & Gómez-Rodríguez, 2024; Letsoalo, 2024).

Other critical factors influencing OER sustainability and content diversity are institutional support and financial resources. The most widely recognized OER initiatives – such as OpenStax, MIT OpenCourseWare, and UNESCO OER – benefit from substantial financial support from universities, philanthropic organizations, and governmental entities (Bossu & Willems, 2024). This centralized funding model ensures long-term sustainability and reinforces the dominance of elite academic institutions in shaping OER narratives, curriculum structures, and pedagogical models.

Conversely, regionally focused repositories such as African Virtual University and Red REA-LATAM contend with severe financial and infrastructural constraints, often relying on intermittent external funding that influences content direction and priorities (Kiplangat, 2024; Ndibalema, 2024). The reliance on international donors and development agencies introduces an additional layer of complexity, as these entities may impose funding conditions that do not necessarily align with local educational needs or cultural contexts. Consequently, the sustainability of regional OERs remains precarious, raising concerns about their long-term viability and independence.

Beyond financial limitations and language barriers, disparities in digital infrastructure and internet accessibility exacerbate inequalities in OER utilization. In high-income regions with high broadband access and high digital literacy, OER platforms are easily integrated into mainstream educational practices. In contrast, lower-income countries face significant technological barriers, including unreliable internet connectivity, lack of affordable digital devices, and insufficient digital literacy training (Mbaya & Ouma-Mugabe, 2024). While some OER initiatives have attempted to bridge this gap through offline access options and mobile-friendly content, these efforts remain limited in scope and scale (Tepe et al., 2024). For example, African Virtual University has experimented with low-bandwidth platforms and offline distribution models, yet infrastructural deficits impede its full potential. Similarly, Red REA-LATAM has implemented downloadable materials to circumvent unreliable internet access, but the absence of robust digital policies and support mechanisms constrains widespread adoption (Mosquera et al., 2024).

OER licensing models also play a significant role in shaping content adaptation and redistribution. Repositories such as MIT OpenCourseWare and OpenStax employ fully open Creative Commons licenses that allow modification, translation, and redistribution, but other platforms impose institutional restrictions limiting these capabilities (Ossiannilsson, 2021). Some repositories require attribution to the original authoring institution, restricting localized adaptation for cultural and pedagogical relevance. Others limit derivative works, preventing educators from modifying content to suit their specific teaching contexts. These licensing restrictions disproportionately benefit well-resourced educational systems, which have the institutional capacity to navigate licensing complexities while constraining the ability of under-resourced communities to engage with and adapt OERs to their local needs fully (Francis et al., 2022).

Furthermore, content representation and thematic focus disparities persist across global OER platforms. High-income nation repositories often emphasize STEM disciplines and traditional academic fields, reinforcing a Western-centric view of knowledge production (Tlili et al., 2022). Social sciences, humanities, and Indigenous knowledge systems are frequently underrepresented in major repositories, limiting the diversity of perspectives available to learners. In contrast, regionally focused OER initiatives attempt to counterbalance this trend by embedding culturally responsive curricula that reflect local histories, epistemologies, and societal challenges (Garcia Peñalvo, 2025). However, these efforts remain constrained by resource shortages and the dominance of Euro-American pedagogical frameworks that shape global education trends.

4.4 Implications for OER Design and Development

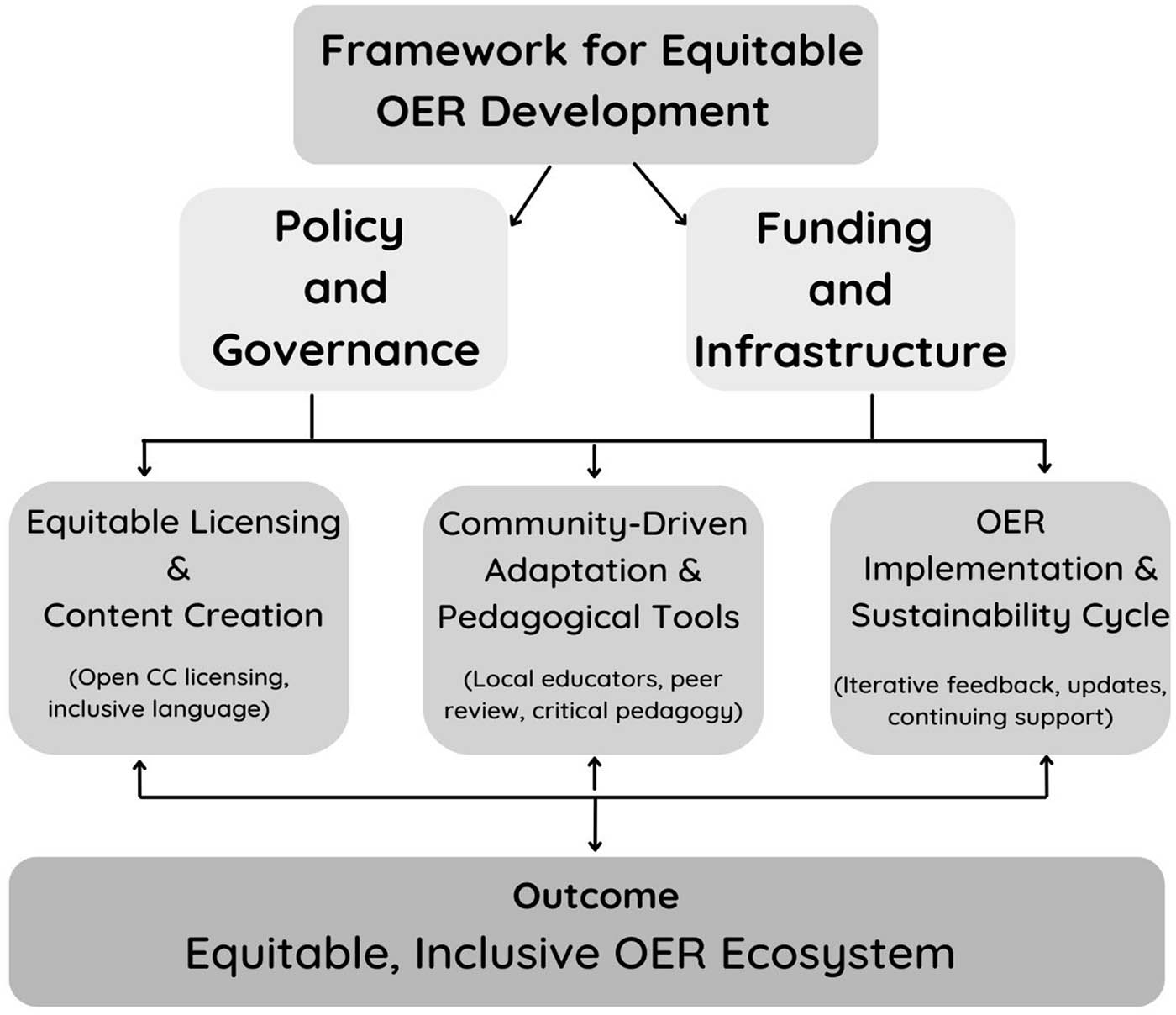

The findings indicate a pressing need for a more equitable, participatory, and contextually responsive OER framework that actively counters existing disparities in knowledge production and accessibility. Figure 4 illustrates a conceptual model of proposed improvements for equitable OER design. The figure is a vertical flow that starts at the top with two foundational pillars – Policy & Governance and Funding & Infrastructure – and continues downward through various layers. Eventually, it leads to the “Outcome” at the bottom – a truly equitable and inclusive OER ecosystem. The arrows between the layers suggest that each layer informs or enables the next, an ongoing process rather than a one-off procedure.

Framework for equitable OER development. Note. This illustrates a structured approach to developing equitable OERs, emphasizing the interconnectedness between policy and governance and funding and infrastructure in shaping equitable OER ecosystems.

The Framework for Equitable OER Development starts with Policy & Governance and Funding & Infrastructure as foundational pillars. Equitable Licensing & Content Creation make open and inclusive materials possible, followed by Community-Driven Adaptation & Pedagogical Tools, which ensure local relevance and active learning. The Implementation & Sustainability Cycle guarantees that OER remains effective and valuable over time, while the Outcome is a strong and evolving equitable OER ecosystem continually shaped by feedback loops and community involvement. The parenthetical notes under each stage detail the essential principles, such as open creative content licensing, critical pedagogy, and iterative feedback, offering actionable practices to maintain a focus on equity and accessibility beyond just “free” content.

A critical area is expanding equitable knowledge production and ensuring that OER initiatives incorporate diverse epistemologies, linguistic accessibility, and regionally grounded curricula that move beyond dominant Western paradigms (Rüschenpöhler, 2024). Many existing OER repositories, particularly those based in high-income nations, maintain traditional academic structures prioritizing Eurocentric knowledge systems while marginalizing alternative ways of knowing. To foster a more inclusive OER landscape, initiatives must prioritize integrating Indigenous perspectives, localized knowledge, and multilingual resources, ensuring that underrepresented educational frameworks receive equal recognition and accessibility (George-Reyes et al., 2024; Letsoalo, 2024).

Another significant implication of the findings is the need to strengthen localized and culturally responsive OERs. While some regionally focused repositories, such as the African Virtual University (OER Africa) and Red REA-LATAM, have made noteworthy progress in contextualizing educational materials to reflect cultural and linguistic diversity, these efforts remain constrained by financial limitations and institutional backing (Tepe et al., 2024). Expanding Indigenous knowledge integration and providing broader multilingual materials would enable learners from marginalized communities to engage with content that reflects their lived experiences and educational priorities. Without deliberate efforts to expand these initiatives, OERs risk reinforcing epistemic exclusion, further disadvantaging learners in non-Western contexts. Implementing participatory content development, where local educators and scholars actively contribute to and modify OERs, would enhance the relevance and adaptability of open-access educational materials.

Beyond content diversification, the study accentuates the necessity of expanding institutional and policy-level support to ensure the sustainability of OER development. Many OER platforms rely on external donors or short-term grants, leading to inconsistent funding that impedes long-term accessibility and innovation. Governments, philanthropic organizations, and international agencies must be more active in financing open education initiatives, particularly in low-income regions where financial and infrastructural constraints are most pronounced (Wimpenny, Finardi, Orsini-Jones, & Jacobs, 2022).

Moreover, cross-regional collaborations among educational institutions could facilitate knowledge-sharing networks that improve the sustainability of OER models, reducing reliance on external entities that may dictate content priorities based on funding conditions. More substantial policy interventions are also required to integrate OERs into formal education systems, ensuring that they are not merely supplementary resources but are embedded within national curricula as viable and accredited learning tools. A more equitable OER framework must balance accessibility, quality, and contextual relevance, recognizing that open access alone does not ensure educational equity. Achieving this requires addressing systemic inequalities in funding, language representation, and institutional adoption while fostering collaboration, policy support, and sustainable funding for inclusive open education (Bossu & Willems, 2024).

Thus, while OERs have significantly expanded educational access, systemic inequalities remain embedded in content, licensing, and dissemination structures. Without intentional, equity-driven reforms, OERs risk perpetuating existing knowledge hierarchies rather than dismantling them. A reimagined open-access education model must prioritize co-creation, participatory learning, and policy-driven inclusion efforts, ensuring a just and equitable global knowledge ecosystem. This requires sustained commitments from policymakers, institutions, and educators to embed equity into the very foundation of OER development and dissemination. Failure to do so may result in an open education landscape that remains accessible in theory but exclusionary in practice, reinforcing global disparities rather than alleviating them (Watson, Petrides, Karaglani, Burns, & Sebesta, 2023).

5 Discussion

OERs reflect the complex relationship between power, equity, and knowledge democratization, yet systemic disparities continue to shape their design, accessibility, and impact (Watson et al., 2023). The architecture and content model of OERs determines the extent to which they promote inclusivity or reinforce existing educational hierarchies. As demonstrated in Figure 1, major OER platforms, particularly those developed in high-income regions, prioritize disciplines such as STEM and social sciences, perpetuating Western-oriented academic paradigms (Abelson, 2008; Wilcox & Lawson, 2022). While these repositories – MIT OpenCourseWare, OpenStax, and MERLOT – offer freely accessible educational materials, they reflect institutional structures that largely centralize knowledge production within elite academic institutions, often at the expense of alternative epistemologies (Flinn & Openo, 2024).

In contrast, regionally focused repositories such as OER Africa and Red REA-LATAM adopt a contextually sensitive approach, integrating Indigenous knowledge systems, localized curricula, and multilingual content (Letsoalo, 2024; Mosquera et al., 2024). These platforms provide critical alternatives to hegemonic educational models, fostering culturally relevant learning experiences while addressing historical exclusions based on language and socio-economic marginalization (Tepe et al., 2024). However, despite these efforts, Figure 2 shows the technological and infrastructural barriers that disproportionately affect OER access in low-income regions, reinforcing the need for sustained investment in digital infrastructure and policy-driven initiatives to bridge these divides (Mbaya & Ouma-Mugabe, 2024).

A persistent challenge in equitable OER adoption lies in funding and institutional sustainability. While international collaborations have facilitated regional OER expansion, external funding dependencies raise concerns about these initiatives’ long-term viability and autonomy (Letsoalo, 2024). The forthcoming OEGlobal 2026 conference will be hosted by MIT OpenCourseWare in collaboration with the Massachusetts Open Education Resources (OER) Advisory Council, raising important questions about the decentralization of knowledge production in OER. While MIT has been a pioneer in the field, the concentration of OER leadership within elite institutions continues to highlight systemic inequities in global access to knowledge. Similarly, the UNESCO Estancia 2025 initiative, which marks a decade of Open Education in Latin America, aims to strengthen regional engagement and counterbalance these disparities by centering localized knowledge and multilingual education (Open Education Global, 2025). As Figure 3 demonstrates, the disparity in financial support between high-income and low-income regions directly correlates with variations in OER production and sustainability (Bossu & Willems, 2024). Many regionally developed repositories struggle to maintain consistent content updates, translation efforts, and technological enhancements, limiting their scalability and effectiveness in education reform (Tepe et al., 2024).

Beyond funding constraints, the digital divide remains a structural impediment to OER accessibility. In many rural and marginalized communities, limited internet infrastructure, lack of digital literacy programs, and inadequate access to devices exacerbate educational inequalities (Mosquera et al., 2024; Tepe et al., 2024). While OER initiatives such as Red REA-LATAM and the African Virtual University have implemented low-bandwidth and offline-access solutions, these adaptations remain insufficient in bridging the global digital divide (Sylla et al., 2022). Figure 4 illustrates how disparities in digital literacy and internet access hinder the widespread adoption of OERs, underscoring the urgent need for policy interventions and investment in educational technology infrastructure.

Additionally, OER platforms exhibit significant variations in their alignment with critical pedagogy. Repositories such as MIT OpenCourseWare and OpenStax primarily employ traditional, instructor-centered models, where students remain passive recipients of information rather than active participants in knowledge construction (Navarra-Madsen, 2024; Qu, 2023). This limitation contradicts the principles of Freirean pedagogy, which emphasize dialogic learning, student agency, and participatory knowledge production (Freire, 1970; Katz & Van Allen, 2022). Conversely, OER Commons and MERLOT provide greater adaptability and educator-driven customization, fostering localized, learner-centered approaches (Chan et al., 2024; Priya & Senthilnathan, 2024). However, despite their greater potential for interactivity and contextual adaptation, the quality and consistency of educator-contributed materials remain uneven, affecting their credibility and widespread adoption (Sergiadis, 2024).

Furthermore, the role of licensing frameworks in shaping OER accessibility and adaptation warrants closer examination. While repositories such as MIT OpenCourseWare and OpenStax employ open Creative Commons licensing, allowing for freer adaptation and redistribution, others impose restrictive licensing models that limit modifications, translations, and localized use (Ossiannilsson, 2021). These constraints reinforce hierarchical knowledge dissemination, disproportionately benefiting well-resourced educational systems while restricting knowledge appropriation in underprivileged contexts (Francis et al., 2022). Figure 3 illustrates how licensing restrictions impact the ability of different global regions to adapt OER materials, reinforcing the need for policy reforms that promote equitable content distribution.

Several policy recommendations should be prioritized to ensure OERs fulfill their transformative potential.

Governments and international organizations must integrate OER adoption into national education policies, providing sustainable funding mechanisms to reduce reliance on external donors (Wimpenny et al., 2022).

Licensing policies should prioritize open-access frameworks that allow unrestricted modification, translation, and regional adaptation, fostering inclusive knowledge-sharing ecosystems (Francis et al., 2022).

Finally, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and adaptive learning platforms promise to redefine OER engagement, enabling personalized learning experiences that align with critical pedagogy principles (Bernard, 2024). AI-driven content recommendation systems and real-time feedback mechanisms could enhance student agency, promoting greater participation in open education ecosystems (Wimpenny et al., 2022). However, the integration of AI within OER must be approached critically, ensuring that technological advancements do not reinforce existing power structures or exacerbate digital inequities (Bernard, 2024).

6 Conclusion

Expanding OERs has increased access to learning materials. Yet, significant disparities in content production, accessibility, and pedagogical approaches continue to undermine their role as tools for educational equity. High-income nations and elite institutions control much of the OER landscape, prioritizing STEM-based curricula and Western academic models. At the same time, regional OER initiatives struggle with financial sustainability, technological barriers, and policy limitations. Although some platforms foster linguistic diversity, localized knowledge, and participatory learning, many reproduce hierarchical, instructor-led teaching models that limit student agency and co-creation. To realize the full potential of OERs, governments, policymakers, and educational institutions must implement sustainable funding strategies, digital infrastructure improvements, and licensing reforms that enable greater flexibility and adaptation for diverse learning contexts. Furthermore, advancements in AI-driven personalization offer new opportunities for adaptive and learner-centered education, but must be designed ethically to prevent reinforcing systemic inequities. Ultimately, OERs can only become truly transformative if they move beyond access alone and embrace a model prioritizing justice, inclusion, and critical engagement in global education. Participating in OEWeek 2025, for example, contributing to OER Commons or sharing open assets provides opportunities for knowledge co-creation and community-driven action, as ensuring that OER frameworks align with inclusive, participatory, and justice-oriented pedagogies requires collective commitment at both institutional and grassroots levels.

-

Funding information: The University of Arizona provided institutional funding support to cover publishing fees.

-

Author contributions: All authors accept responsibility for the content of this manuscript and consent to its submission. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. D.M.B. conceived the study and wrote the initial draft. R.B. contributed to the methodology, data analysis, and editing. Both authors contributed to the interpretation of results and the final revisions.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

Summary of OER Platform Characteristics

| OER platform | Classification | Content model | Licensing | Institutional backing | Pedagogical approach | Accessibility | Global equity & inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIT opencourse-ware | University-hosted courses | Freely available university materials | Creative Commons, fully open | MIT | University-structured, lecture-based | Fully open, no login required | STEM and technical fields are heavily represented |

| OER commons | Aggregator | Searchable educator-contributed OERs | Creative Commons, varying licenses | Multiple institutions & educators globally | Educator-curated, adaptable | Open access, some registration required | Varied subjects, inclusive of multiple disciplines |

| UNESCO OER | Global Repository | Digital library of OERs | Creative Commons, an open-access framework | UNESCO, global education institutions | Knowledge-sharing repository | Fully open-access, UNESCO-backed | Designed to support global education equity |

| OpenLearn | Open university-led Platform | Self-paced courses and materials | Open-access, some restrictions | UK Open University | Self-paced learning, interactive materials | Free access, some enrollment required | English-language focused, widely accessible |

| MERLOT | Curated Repository | Faculty-contributed higher education resources | Creative Commons, educator-driven | Higher education faculty, universities | Higher education-focused, discipline-specific | Open access, some institutional knowledge required | Broad academic coverage but Western-centric |

| OpenStax | University-published Textbooks | Freely available textbooks | Creative Commons-licensed | Rice University, philanthropic support | Textbook-centered learning | Fully accessible, textbook format | Supports under-resourced learners |

| OER Africa | African Continent-focused Initiative | Online courses and materials | OERs, government-backed | African Virtual University, education ministries | Online learning for African education systems | Open access, but infrastructure limitations | Designed specifically for African educational needs |

| Red REA-LATAM | Latin American Region-focused | Spanish/Portuguese-language content | Creative Commons, regionally curated | Latin American universities, education ministries | Culturally relevant materials | Freely available, Spanish/Portuguese focus | Culturally responsive content for Latin America |

Note. This table provides an overview of the key characteristics of selected OER platforms, including their classification, content models, licensing, and accessibility features. The information is based on publicly available data.

References

Abelson, H. (2008). The creation of OpenCourseWare at MIT. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17, 164–174. doi: 10.1007/S10956-007-9060-8.Search in Google Scholar

Adekanmbi, G. (2021). The state of access in open and distance learning in sub-Saharan Africa. In P. Jain, N. Mnjama, & O. Oladokun (Eds.), Open access implications for sustainable social, political, and economic development (pp. 160–182). Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-5018-2.ch009.Search in Google Scholar

Apple, M. W. (2018). Ideology and curriculum. In Ideology and curriculum. New York, NY, USA: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429400384.Search in Google Scholar

Bernard, D. M. (2024). Reimagining Indigenous education in Costa Rica through Paulo Freire’s pedagogical lens: A critical analysis. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 5(4), 3415–3437. doi: 10.56712/latam.v5i4.2503.Search in Google Scholar

Bossu, C., & Willems, J. (2024). OER-based capacity building to overcome higher education staff equity and access issues. Brisbane, Australia: ASCILITE Publications. doi: 10.14742/apubs.2017.734.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, H., Wong, T., Lohana, P., Mitra, S., & So, J. (2024). Top 10 computer science Open Educational Resources in MERLOT. In 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC) (pp. 2228–2232). doi: 10.1109/COMPSAC61105.2024.00357.Search in Google Scholar

Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., & Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262–276. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184998.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Cubides, S. M., Chiappe, A., & Ramirez-Montoya, M. S. (n.d.). The transformative potential of Open Educational Resources for teacher education and practice. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2024.2409808.Search in Google Scholar

Dickson, C., & Holm, C. (2022). Open access publishing biases OER. Kennesaw, GA, USA: Digital Commons@Kennesaw State University. doi: 10.32727/27.2022.2.Search in Google Scholar

Drumond, G., Méxas, M., & Meza, L. (2024). Opening the horizons for education: Reflections on repositories of open educational resources in higher education. Em Questão, 30, e-133916. doi: 10.1590/1808-5245.30.133916.Search in Google Scholar

Dutra, S., Chee, V., & Clochesy, J. (2023). Adapting an educational software internationally: Cultural and linguistical adaptation. Education Sciences, 13(3), 237. doi: 10.3390/educsci13030237.Search in Google Scholar

Farrow, R. (2017). Open education and critical pedagogy. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(2), 130–146. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2016.1113991.Search in Google Scholar

Flinn, C., & Openo, J. (2024). Are we asking too much of OER? A conversation on OER from OE Global 2023. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 25(4), 201–214. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v25i4.7744.Search in Google Scholar

Florencio-Wain, A. F. (2024). Voices of the holistically educated: Impacts and outcomes beyond academics. Albany, NY, USA: State University of New York at Albany.Search in Google Scholar

Forehand, L. C. (2024). From access to equity: The role of OER and technology in higher education. Long Beach: California State University.Search in Google Scholar

Fortney, A. (2021). OER textbooks versus commercial textbooks: Quality of student learning in psychological statistics. Locus: The Seton Hall Journal of Undergraduate Research, 4(1), 4. doi: 10.70531/2573-2749.1037.Search in Google Scholar

Francis, R., Hill, C., & Overmier, J. (2022). The opportunity of now: Adopting Open Educational Resources in the sociology classroom and beyond. Teaching Sociology, 51(4), 381–392. doi: 10.1177/0092055X221129638.Search in Google Scholar

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. https://archive.org/details/pedagogyofoppres00frei/page/n195/mode/2up.Search in Google Scholar

Garcia Peñalvo, F. J. (2025). Elaboración de políticas de apoyo de Educación y Ciencia y Abierta, presentado en Estancia Internacional organizada por la Cátedra UNESCO Movimiento Educativo Abierto para América Latina 2025, Monterrey, México, 20-31 de enero de 2025. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.14708770.Search in Google Scholar

George-Reyes, C. E., López-Caudana, E. O., & Gómez-Rodríguez, V. G. (2024). Communicating educational innovation projects in Latin America mediated by the scaling of complex thinking: Contribution of the UNESCO-ICDE Chair in Mexico. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 14(3), e202434. doi: 10.30935/ojcmt/1462.Search in Google Scholar

Giacomazzi, M., Fontana, M., & Camilli Trujillo, C. (2022). Contextualization of critical thinking in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic integrative review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 43(October 2020), 100978. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100978.Search in Google Scholar

Giroux, H. (2020). Critical pedagogy, In U. Bauer, U. H. Bittlingmayer, & A. Scherr (Eds.), Handbuch Bildungs- und Erziehungssoziologie (pp. 1–16). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-31395-1_19-1.Search in Google Scholar

Griffiths, R., Mislevy, J., & Wang, S. (2022). Encouraging impacts of an Open Education Resource Degree Initiative on college students’ progress to degree. Higher Education, 84(5), 1089–1106. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00817-9.Search in Google Scholar

Gulyamov, S., Yakubov, A., & Karakhodjaeva, D. (2024). The role of open educational resources in advancing distance and online learning. 2024 4th International Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning in Higher Education (TELE) (pp. 365–367). doi: 10.1109/TELE62556.2024.10605598.Search in Google Scholar

Harvey, P., & Bond, J. (2022). The effects and implications of using open educational resources in secondary schools. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 22(3), 107–119. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v22i3.5293.Search in Google Scholar

Hilton III, J. L., Gaudet, D., Clark, P., Robinson, J., & Wiley, D. (2013). The adoption of open educational resources by one community college math department. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(4), 37–50. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i4.1523.Search in Google Scholar

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Teaching-to-Transgress-Education-as-the-Practice-of-Freedom/hooks/p/book/9780415908085.Search in Google Scholar

Inefuku, H. (2017). Globalization, open access, and the democratization of knowledge. Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education. (n.d.). Half Moon Bay, CA, USA: OER Commons. https://oercommons.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Junasova, D., Rzeplinksi, A., & Alards-Tomalin, D. (2025). Open in higher education: Student experiences and perceptions of OER. Journal of Open Educational Resources in Higher Education, 3(1), 113–124. doi: 10.31274/joerhe.17955.Search in Google Scholar

Karakaya, K., & Karakaya, O. (2020). Framing the role of English in OER from a social justice perspective: A critical lens on the (dis) empowerment of non-English speaking communities. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 175–190. https://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/508.Search in Google Scholar

Katz, S., & Van Allen, J. (2022). Open with intention: Situating equity pedagogy within open education to advance social justice. Journal for Multicultural Education, 16(5), 421–429. doi: 10.1108/jme-07-2022-0089.Search in Google Scholar

Kiplangat, H. K. (2024). Transformational leadership in higher education: Empowering Africa’s future. Journal of Research and Academic Writing, 1(2), 65–73. doi: 10.58721/jraw.v1i2.846.Search in Google Scholar

Knight, J. (2024). Higher education cooperation at the regional level. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 26(1), 101–115. doi: 10.1108/JICE-09-2023-0021.Search in Google Scholar

Komor, M., & Grzyb, K. (2023). Qualitative content analysis – A research method in social science. Przegląd Badań Edukacyjnych, 2(43), 143–163. doi: 10.12775/pbe.2023.032.Search in Google Scholar

Kwarteng, I. (2021). Integrated science teachers’ attitude and use of digital resources in private basic schools in the Bia West District. Winneba, Ghana: University of Education Winneba.Search in Google Scholar

Law, P., & Storrar, R. (2024). The motivation to earn digital badges: A large-scale study of online courses. Distance Education, 46(2), 190–208. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2024.2338732.Search in Google Scholar

Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. In Internationalizing the curriculum. New York, NY, USA: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315716954.Search in Google Scholar

Letsoalo, N. (2024). Bridging the divide: Indigenous language integration in Open Educational Resource accessibility. Mousaion: South African Journal of Information Studies, 42(3), 1–19. doi: 10.25159/2663-659x/11906.Search in Google Scholar

Lochmiller, C. (2021). Conducting thematic analysis with qualitative data. The Qualitative Report, 26(6), 2029–2044. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5008.Search in Google Scholar

Lourenço, F., Oliveira, R., & Tymoshchuk, O. (2024). How can Open Educational Resources promote equity in education? In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health - ICT4 AWE (pp. 132–139); SciTePress. doi: 10.5220/0012586500003699.Search in Google Scholar

Massachusetts Institute of Technology - MIT. (n.d.). MIT opencourseware. https://ocw.mit.edu/.Search in Google Scholar

Mays, T. J., Aluko, F. R., & Combrinck, M. H. A. (2020). Exploring dual and mixed mode provision of distance education. London, England & New York, NY, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9780429287473Search in Google Scholar

Mazouz, Z., & Khalida, A. (2024). The virtual university–models and experiences. International Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(4), 755–765. https://ijeponline.org/index.php/journal/article/view/590.Search in Google Scholar

Mbaya, M., & Ouma-Mugabe, J. (2024). A systematic literature review and mapping of systemic barriers to digital learning innovation in Africa in the context of changing global value chains. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 16(4), 491–511. doi: 10.1080/20421338.2023.2287803.Search in Google Scholar

Moges, B., Assefa, Y., Tilwani, S., Desta, S., & Shah, M. (2023). The inclusion of Indigenous knowledge into adult education programs: Implications for sustainable development. Studies in the Education of Adults, 56(1), 5–25. doi: 10.1080/02660830.2023.2196174.Search in Google Scholar