Abstract

Since the expansion of higher education began, student motivation and institutional choice have been widely studied, yet the reasons behind high dropout rates in public institutions in Central and Eastern Europe remain poorly understood. In our research, we sought to answer the question of what subjective and objective factors predict an increased risk of dropping out. We analyzed the views of students who had already dropped out and active students in our empirical research database (N = 1,502), recorded in 2018–19. A large-scale questionnaire survey was conducted to examine students’ perceptions. We hypothesized that family background, academic motivational factors, and external and internal institutional networks each have an independent impact on the perception of dropout risk in both groups studied. Our results, based on multivariable analysis, show that the effect of individual sociodemographic factors is significant. However, parental involvement clearly proved to be the strongest protective factor, along with the positive effect of institutional intergenerational support and intrinsic motivation for further education. We recommend that institutions develop a comprehensive strategy to enhance family support and reinforce the role of extracurricular activities in higher education.

1 Introduction

Student dropout is when a student leaves a higher education institution without a diploma. This is a phenomenon that affects almost all higher education institutions and impacts all actors in higher education (Miskolczi, Bársony, & Király, 2018; Pusztai, Demeter-Karászi, Alter, Marincsák, & Dabney-Fekete, 2022a; Tóth, Szemerszki, Ceglédi, & Máté-Szabó, 2019). With this in mind, it is worth exploring the reasons for student dropout (Kovács et al., 2019). Although there can be significant differences in dropout rates within a single country, and international statistics are often difficult to compare and provide only a limited perspective on the issue, it is essential to consider data from a report that synthesizes information from multiple sources (Kaiser, Jongbloed, Unger, & Zeemann, 2015). According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization data, the proportion of students in Hungary who graduate on time is around 30%. In contrast, organisation for economic co-operation and development statistics, which account for all tertiary education programs, indicate a more favorable rate of approximately 50%. However, in the region examined in our study, the dropout rate is even higher than the national average, as it is a socio-economically disadvantaged area.

Regarding the explanations for dropout, it should be noted that the overlap of manifest and latent causes is not to be expected in the case of dropout from higher education and that those young people who have dropped out (and many of them are still looking for their place even at the time of the survey) are not able to reflect confidently on the factors behind their failure. Despite that, the analysis of students’ perceptions is highly important, since a major decision such as dropping out of higher education is based on an individual calculation, even if this calculation does not have the characteristics of a rational decision. As Boudon (2013) argues, there are multiple forms of rational deliberation, and not all of them focus solely on maximizing future benefits. In certain decision-making situations, individuals do not evaluate alternatives purely in a calculative manner but also consider norms, values, and moral justifications. Additionally, worldview, value orientation, and spirituality may also influence the decision-making process. Thus, alongside instrumental rationality, axiological rationality also plays a role, which may help explain why students’ dropout decisions are not always based on strictly rational considerations (Tódor, 2022).

Students do not usually have all the necessary information when making a decision to drop out, and even if they did, they might not be able to interpret it in a rational way. While some factors influencing dropout are situated at the systemic or institutional level, many of the most immediate influences are perceived at the individual or interpersonal level. These include students’ academic experiences, social embeddedness, and family support. However, students are often only partially aware of the broader structural or institutional constraints that shape their decisions. Therefore, it is important to investigate dropout not solely through objective indicators, but also by examining how students themselves perceive and interpret their challenges. Decision theory suggests that dropout is rarely the result of a single identifiable cause; instead, students’ choices often reflect a complex network of interrelated factors. Our analysis focuses on how students make sense of these difficulties – whether they stem from personal, relational, or contextual sources – and how such perceptions contribute to their sense of dropout risk (Brundsen, Davies, Shevlin, & Bracken, 2000; Kovács et al., 2019). Accordingly, this study aims to explore which social and institutional experiences most strongly shape students’ perceptions of dropout risk in the context of Hungarian higher education.

2 Theoretical Background

Uninterrupted progress toward a degree and drop-outs that never lead to a degree are two endpoints of a very wide scale (Hagedorn, 2012). The first studies of the problem dealt with voluntary drop-out from higher education, where students dismissed for academic and behavioral-ethical problems were not considered as drop-out, only those who left their studies by their own choice (Tinto, 1975). This phenomenon can also be approached by looking at students who are hesitant to continue their studies, since they are in a permanent state of reflection, in which they make decisions about whether to stay or drop out based on their everyday experiences and interactions (Tinto, 1993). Previous research on explanations for dropout have provided a multifaceted picture to characterize a wide range of students on different learning pathways (Kovács et al., 2019; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). In our study, we relied on the most widely recognized factors in the literature, which have traditionally been identified as key explanatory variables for student dropout. At the same time, we also aimed to explore new explanatory variables, seeking to identify additional factors that may not have been the primary focus of previous research but could be relevant for a deeper understanding of dropout risks. Given the complexity of dropout, it is crucial to consider the multiple ways in which various factors may influence students’ academic trajectories (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). In the following, we seek to answer this question.

This leads us to consider not only the personal decisions made by students but also the social structures and relationships that influence these decisions. Educational behavior is interpreted differently across various theoretical perspectives. Some approaches explain it through an individual’s position within the social structure (Bourdieu, 1973), while others emphasize the role of personal decision-making (Boudon, 2013; Tódor, 2022). However, Coleman (1990) argues that school processes are not solely determined by one’s position in the vertical social structure or individual choices but are also significantly influenced by the impact of social relationships on decision-making. Consequently, individual decisions are shaped by the interplay of resources embedded in social networks (Pusztai, 2015a).

Theoretical perspectives suggest an important question regarding how various social and personal factors interact and contribute to different student experiences. The experience of previous research shows that the risky position of men is clearly visible (Ceglédi, Fényes, & Pusztai, 2022; Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021; Pusztai et al., 2022a). A key contributing factor to these differences lies in family socialization, where gendered expectations shape children’s attitudes toward education from an early age. Variations in external and internal motivation between genders influence academic persistence, with girls demonstrating greater tolerance for failure and higher perseverance within the education system. Boys, on the other hand, are more susceptible to peer influence, and environmental factors tend to affect them asymmetrically, which may further increase their dropout risk. These differences in motivation and resilience are further reinforced by the structure and function of social networks. Women perform better not only because they are more hardworking and willing to meet external expectations or because they are more inclined to share attention, but also because their network of relationships is stronger. They also can mobilize their relationships in a targeted way, which increases their flexibility and adaptability (Fényes, 2022). This allows them to acquire and decipher in time the information held by lecturers and administrators, which is not always transparent, to access the right learning material, and to warn each other of the “dangers” lurking in the “labyrinth” of higher education. In this system, male students are more likely to get lost because their peer network is more extensive but weaker, and their circle of acquaintances is more leisure-oriented, casual, and sometimes open or hidden (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). The individualistic approach and the wide network of weak ties cannot effectively support effective progression, as we have already found in previous research (Pusztai, 2015a).

In line with the tradition of educational research in Hungary, we can estimate the cultural capital that a student can rely on at home based on the educational attainment of parents. The concept of cultural capital is closely linked to broader social inequalities and their impact on education, which extends to higher education as well. Parents with higher educational attainment not only provide direct academic support but also shape their children’s attitudes toward learning, ambition, and career expectations. Their familiarity with the educational system and their ability to navigate institutional requirements can serve as an advantage for their children, reinforcing existing social inequalities. Conversely, students from less-educated families often face additional challenges in accessing institutional resources and adapting to academic expectations. These disparities in cultural capital contribute to differences in student persistence and dropout risks in higher education. Contrary to expectations, if the mother has a higher education degree, it increases the chances of passive semesters and delays in studies (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). Taking the results of previous research further and interpreting them in the context of mass education, the following explanations become plausible. Mothers, particularly highly qualified mothers, play an important role in families in setting further education goals and tend to push their children toward the most ambitious further education goal possible (Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). Among graduates, this means that they tend to aspire to high-prestige courses. Forward-looking and informed parents are more likely to influence their children toward choices that young people might be less inclined to make, in which case students’ progress more slowly along the path set by their parents. In addition, parents with a higher education diploma effectively pass on high expectations to the younger generation, and these expectations are also reflected in high expectations of higher education institutions. This may be reinforced by the positive experience of parents with higher education, which they acquired mostly before mass education (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). It is no coincidence that disillusionment with higher education, skepticism, and disappointment with the course and institution are the most common in the case of children of highly educated parents (Kovács et al., 2019; Pusztai, 2015a). It is also possible that highly educated mothers have set overly ambitious further education goals for their children, where they have failed to keep their feet on the ground. Meanwhile, for parents with lower qualifications, no prior knowledge, and expectations of higher education, any degree means an increase in status, so they often leave the decision to their children, even if the chosen course does not pay off in the long run. It is also natural that students feel more successful in their chosen major and the perception of success encourages them to perform well. This nuanced relationship between maternal education and dropout risk highlights the complexity of educational inequalities. While higher parental education generally reduces dropout risk, the selection of more prestigious and academically demanding programs by students from highly educated families may expose them to greater challenges. As a result, the proportion of those facing dropout risks may vary across different educational tracks. These findings refine existing knowledge on the impact of educational attainment on dropout risk, emphasizing that institutional selectivity and field of study must also be considered when interpreting these effects (Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021).

Research results clearly show that a significant proportion of drop-out students leave education because of uninformed career choices and disillusionment with their education (Csók, Hrabéczy, & Németh, 2019; Hrabéczy & Csók 2023; Kovács et al., 2019; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). Incorrect career choice decisions are rooted not only in misperceptions of the student’s aptitudes but also in the inadequate knowledge of the Hungarian career guidance system about the higher education system and labor market opportunities, which career guidance system is only narrowly focusing on psychological characteristics of the students. The costs of a wrong career choice (wasted time, lost semesters of state support, etc.) are paid by the students and their families. Another cause of disappointment in education is disillusionment with outdated higher education curricula and working methods. Changing majors is often the phase of a failed higher education career before final drop-out (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021).

Education research has less often reflected on the qualitative and quantitative features of the relationships that most influence the effectiveness of the educational organization, but several previous research findings have highlighted the strong impact of this (Pusztai, 2015a, 2019). The heterogeneity of the student population has put higher education socialization at the center of attention socialization in those higher education systems that encountered the expansion of higher education earlier. Entering the higher education institution’s network and the disengagement from external networks have begun to be recorded as decisive factors (Tinto, 1975, 1993). There is a consensus that dropout is a consequence of ineffective student socialization (Heublein, 2014). Previous research observed a close relationship between attachment to networks, the direction and strength of ties, the multiplexity of ties, and the content of interpretations that influence higher education activities and therefore introduced the concept of student embeddedness to systematically examine students’ institutional ties (Pusztai, 2015a). They confirmed the importance of the role of the availability of lecturers outside the classroom and the possibility of continuous contact with them. The perception of student peer engagement, i.e., how important they consider learning activities and belonging to the campus community to be, was found to be an influential factor (Pusztai, 2015a; Sciarra, Seirup, & Sposato, 2016). While international research has shown the moderating effect of strong intragenerational student relationships on dropout, research in the first years of restructuring higher education in Hungary found that students embedded in the campus peer community had lower achievement (Pusztai, 2015a). It is important to consider in the research on institutional effects that the characteristics of the institution and students’ perceptions of the institutional environment cannot be equated. Therefore, it deserves attention to what becomes a social fact and a collective interpretation within institutional societies (Astin & Antonio, 2011). Additionally, a common mistake is confusing environmental factors and the intensity of student participation (Astin, 1993) – also known as integration (Tinto, 1993) – as one refers to the context, while the other pertains to individual characteristics. It is therefore advisable to consciously treat these separately in analyses (Pusztai & Kovács, 2021).

Little attention has been paid to external intergenerational relations (Pusztai, 2019). At the turn of the millennium, it was suggested that the academic achievement of certain groups of students is supported by the information and even inclusion of parents (Tierney, 2000). There are numerous forms of parental involvement, not only as donators but also as target groups for family events and as members of parent clubs. In the United States, they are organized and informed by university parent liaison offices and are seen in the literature as a key stakeholder group (Chan & Hu, 2023; Dotterer, 2022, McCarron & Inkelas, 2006; Perna & Titus, 2005; Wartman & Savage, 2015). Impact evaluations of institutional programs that engage parents in the student’s higher education development and preparation for obtaining a degree see parents as active partners, and increasingly in direct contact with universities and colleges. They can even be involved in training that prepares and supports their child’s further higher education. Parental involvement or support was previously considered an undesirable intervention, a barrier to student development and autonomy, but recent research suggests that it can contribute to students’ persistence in their studies (Perna & Titus, 2005; Wartman & Savage, 2015; Wolf, Sax, & Harper, 2009). Parental involvement is a multidimensional phenomenon that may include participation in higher education events, interaction with the organization and staff of higher education, in addition, to influence on the choice of major and institution, interest in studies and the organization, financial support, and the increased role of encouragement in case of academic difficulties (Wartman & Savage, 2015). There seem to be changing trends in student contact network orientation and integration and their impact, with an upward trend in extra-organizational networks (Pusztai, 2019).

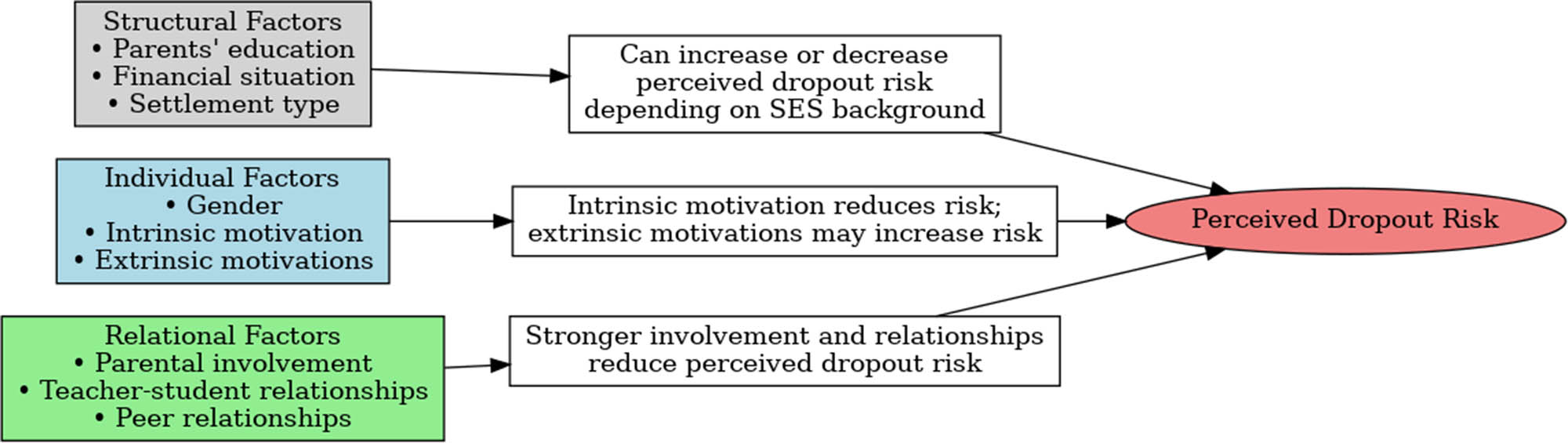

Building on the theoretical perspectives discussed above, we identified three major dimensions that influence students’ perception of dropout risk: structural background factors, individual characteristics and motivations, and relational embeddedness in higher education. These dimensions interact in complex ways, contributing to the diverse student experiences that can either mitigate or intensify the likelihood of dropout. Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual framework of our study, presenting the key factors and their hypothesized effects on perceived dropout risk.

Conceptual framework of factors influencing students’ perceived risk of dropout. Note: the figure summarizes the three major categories of explanatory variables – structural, individual, and relational factors – and their hypothesized effects on students’ perception of dropout risk in higher education.

3 Methodology

The database we analyzed was created by merging two databases (DEPART2018, PERSIST2019) along the variables that were relevant to our analysis and research objectives and were found in both databases. Both data sets are based on cross-border surveys of respondents from Hungary and abroad. However, in the present research, only the Hungarian subsamples were analyzed, and only respondents who were studying in Hungarian institutions and those who dropped out of Hungarian institutions were analyzed. In both surveys, we aimed to reach the broadest possible population by educational background. For the DEPART2018 database, respondents were collected who had left higher education without a degree in the last 10 years from the date of the survey. The data were collected using a snowball method, which did not result in a representative sample, but as a hidden target group, this method of data collection proved to be the most appropriate. The PERSIST2019 database is representative of the Hungarian student population by faculty, field of study, and funding type. Respondents who were active students at the time of data collection were asked. The two databases were merged following the model of Keller and Róbert (2016), who also attempted to merge data from several different surveys for a deeper analysis. During merging and analyzing, missing responses were treated using the listwise deletion method. This approach was chosen because the proportion of missing data was low, minimizing the risk of bias. Moreover, it ensured a straightforward and transparent handling of missing cases, aligning with the study’s focus on predictive analysis. We opted not to impute missing data to avoid introducing artificial variation or bias into the results. A limitation of the present research is different ways and times of data collection. For this reason, we are not looking for significant differences between the two target groups, drop-outs, and active students, but rather focusing on how the different factors that increase the risk of dropping out are perceived within each group and drawing conclusions accordingly. However, merging two datasets introduces potential time-related biases, which we acknowledge as a limitation of our study. Over time, educational policies and institutional conditions may have changed, potentially affecting students’ experiences and perceived dropout risks at the two different points of data collection. One possible way to address this would have been to restrict the analysis to respondents of the same age group; however, this approach would have significantly reduced the sample size and the statistical power of our analysis. Instead, we employed logistic regression, which not only allows for the comparison of respondents with similar characteristics, thereby mitigating time-related biases, but also provides a way to quantify the relationship between risk factors and perceived dropout risk. In this model, Exp(B) (also called the odds ratio) represents the factor by which the odds of the outcome change for a one-unit increase in the predictor variable, holding all other variables constant. Values above 1 indicate an increased likelihood of perceiving higher dropout risks, whereas values below 1 suggest a protective effect against dropout risk.

Our hypotheses were as follows: (H1) based on research findings on gender differences in educational attainment, we assume that men perceive a greater risk of dropping out during higher education (Ceglédi et al., 2022; Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021; Pusztai, Fényes, & Kovács, 2022b). (H2) Based on research findings on the influence of social background on school careers, children of parents with higher education and better financial status are assumed to face fewer risks (Pusztai et al., 2022b; Vossensteyn et al., 2015). (H3) Among the motivations, we hypothesized the risk-protective effects of the status-acquisition and knowledge-acquisition motivations (Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Pusztai, 2015b). We expected the protective effect of (H4) parental involvement and (H5) intergenerational institutional embeddedness (Csók & Pusztai, 2023; Győri & Pusztai, 2022).

3.1 Variables Included in the Analysis

For the two target groups, we investigated which factors reinforce the perception of dropout risk factors. To assess this, a 20-item measure (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.838) was developed by the CHERD-Hungary research team, incorporating both push and pull factors related to academic difficulties, financial difficulties, and family/personal difficulties. The questionnaire is a significant research result, as its high validity and reliability were established through extensive interview research (Pusztai et al., 2022a). This was further confirmed by its strong correlation with progress-measuring variables in previous quantitative studies (Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). In addition to demonstrating strong internal consistency, the scale’s construct validity was established through exploratory factor analysis, which identified coherent and theoretically interpretable dimensions aligned with dropout-related frameworks (Pusztai, 2015b; Pusztai & Szigeti, 2021). Furthermore, its criterion-related validity was supported by consistent and statistically significant associations with academic progress indicators, such as persistence and completion, across multiple large-scale datasets. These findings underscore the scale’s robustness and predictive value in assessing perceived dropout risk. The significance of the questionnaire lies in its ability to capture early signs of dropout risk before actual dropout occurs. Based on this measure, we created an index, which we refer to as the perception of dropout risk index. The question block was used to determine whether respondents had experienced factors that hindered their progress in higher education.[1] An index was formed from these 20 items, which was then transformed into a dummy variable to distinguish between respondents who perceived below-average and above-average dropout risk. In the total sample, 47.2% of students perceived above-average dropout risk factors during their studies. This proportion was 51.9% among drop-outs and 45.1% among active students. While the proportion of active students is lower, it is still significant, suggesting that almost half of the students in higher education experience substantial barriers identified in the survey as risk factors for dropout.

Explanatory variables: demographic and social background factors (such as parents’ level of education, type of settlement, subjective and relative financial situation), parental involvement (e.g., talking with parents about different topics like studies, politics, movies, and spending time together), motivations for further education (moratorium oriented, time passing, mobility-oriented and intrinsic motivation), and inter- and intra-generational dimensions of higher education embeddedness (relationship with peers and instructors) were examined as factors influencing the perception of dropout risk. Among the demographic and social background factors, the following variables were analyzed. In Hungary, the ranking of parental educational attainment was based on the structure of the national education system. After completing primary school, students may choose among three main tracks: (1) vocational school without a high school graduation exam (resulting in vocational qualifications but not eligibility for higher education), (2) secondary vocational school with a high school graduation exam (matura), and (3) general secondary school, also ending with a high school graduation exam. Only the latter two tracks provide access to higher education, which includes college and university degrees. Accordingly, the educational degrees were ranked from lowest to highest: primary school completion, vocational school without high school graduation exam, secondary vocational or general secondary school with high school graduation exam, and higher education degree. For gender, we examined whether being male increases the perception of dropout risks, based on Fényes’ (2010) male bias hypothesis. We compared the effect of lower social status indicators on the educational attainment of mother and father with that of parents with a degree, on the type of municipality with that of a large city, and on subjective and relative financial situation with better than average financial situation. We examined the relationship between the degree of parental involvement and the perception of dropout risk. In this respect, we created a principal component of a 6-item question block, which was included in the analysis as a continuous variable. The relationship between the different motives for continuing education and the perception of dropout risk is investigated. For these variables, 4 factors were constructed from a block of 12 items, including moratorium seeking, time-passing, mobility-oriented career choice, and intrinsic motivation. We speak of moratorium seeking career motivation when the student expects a high income and recognition through the chosen career. In the case of time-passing career motivation, the students chose the given university major because they did not want to start working yet, or could afford to continue their studies instead of working. In the case of mobility-oriented career choice, the hope of social mobility plays a prominent role. We speak of intrinsic motivational factors of career choice when the students decide to continue their studies due to the acquisition of knowledge and the building of relationships. Finally, we examined inter- and intra-generational higher education embeddedness. For intergenerational embeddedness, we created a principal component from a block of 8 items, and for the examination of intragenerational embeddedness, we created an index from a block of 10 items. The construct validity of key measures, such as intrinsic motivation and intergenerational embeddedness, has been previously tested in earlier research (Pusztai, 2015b), ensuring their reliability in the present study.

4 Results

Using the variables listed above, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed, where the dependent variable was the above-average perception of dropout risk factors. The analysis was performed using a split procedure to bisect the database along the two target groups. The purpose of this was to examine how our explanatory variables behave for the two target groups, and how they are related to the perception of the occurrence of dropout risk factors. The results of the regression analysis are illustrated in Table 1. All the variables listed above were included in the analysis, but Table 1 summarizes only the factors that are significant.

Factors affecting the above-average perception of the presence of dropout risk factors (binary logistic regression analysis, N = 1,502)

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dropped out students | Male | 0.541 | 0.258 | 4.390 | 1 | 0.036 | 1.718 |

| Mother’s education (ref.: graduate) | 5.768 | 2 | 0.056 | ||||

| Lower than higher education | −0.924 | 0.408 | 5.126 | 1 | 0.024 | 0.397 | |

| Higher education | −0.647 | 0.334 | 3.752 | 1 | 0.053 | 0.524 | |

| Parental involvement | −0.449 | 0.154 | 8.557 | 1 | 0.003 | 0.638 | |

| Moratorium-seeking career choices | 0.257 | 0.121 | 4.507 | 1 | 0.034 | 1.293 | |

| Path-seeking career choice | 0.334 | 0.149 | 5.028 | 1 | 0.025 | 1.397 | |

| Career choices for mobility | 0.323 | 0.144 | 5.007 | 1 | 0.025 | 1.381 | |

| Intrinsic motivation-driven career choice | −0.262 | 0.128 | 4.172 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.769 | |

| Intergenerational higher education embeddedness | −0.372 | 0.153 | 5.921 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.689 | |

| Constant | −1.063 | 0.550 | 3.737 | 1 | 0.053 | 0.345 | |

| Active students | Subjective financial situation (ref: better than average financial situation) | 12.112 | 3 | 0.007 | |||

| You have everything, but not much to spend | 0.486 | 0.190 | 6.531 | 1 | 0.011 | 1.626 | |

| Sometimes you cannot cover your everyday expenses | 1.411 | 0.460 | 9.429 | 1 | 0.002 | 4.100 | |

| You often cannot cover your everyday expenses | 0.199 | 0.873 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.820 | 1.220 | |

| Parental involvement | −0.361 | 0.103 | 12.206 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.697 | |

| Intrinsic motivation-driven career choice | −0.316 | 0.085 | 13.882 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.729 | |

| Constant | −0.068 | 0.381 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.859 | 0.935 |

Source: DEPART2018, PERSIST2019.

Table 1 shows that some variables play a similar role, and some variables play a different role in the perception of the presence of dropout risk factors for the two target groups. For dropout respondents, the following results can be seen. If the respondent is male, the chances of the respondent perceiving dropout risk factors to be above average during studies increase. In addition, however, lower than graduate maternal education, parental involvement, and intergenerational higher education embeddedness all reduce the odds of perceiving dropout risk factors or even their actual presence. In the case of motives for further education, it can be seen that the presence of intrinsic motivation alone reduces the chances of perceiving dropout risk factors in this target group, while extrinsic motivational factors, such as moratorium seeking, hopes of social mobility, and path seeking, time procrastination all increase the chances of this risk.

For active students compared to drop-out respondents, there is no significant effect of gender, mother’s education, extrinsic career motivation factors, and intergenerational higher education embeddedness. In contrast, however, it can be seen that if the respondent’s subjective financial situation is average or worse, this increases the likelihood of perceived risk factors for dropping out. For this target group, the level of parental involvement also has a positive effect, with higher levels of involvement reducing the presence or perception of risk factors, and the same is observed for the presence of an intrinsic motivational factor for career choice.

5 Discussion

In our study, we sought to answer the question of what factors increase the likelihood that students will encounter factors that threaten their academic progress and degree attainment during their higher education studies to such a significant degree that they are placed in the at-risk group. Using a self-developed measurement tool, we measured the factors that students themselves perceive as risk factors for drop-out, whether they are push factors from outside higher education or pull factors from outside the institution.

In our analysis, we looked at two groups of students in terms of the background factors that are likely to contribute to this negative premonition. In itself, the usefulness of the above-mentioned set of questions in predicting risk is invaluable, but it is important to identify factors that may themselves increase risk to prevent it. A retrospective report was requested from one of the two groups, as they had already experienced drop-out. Of course, retrospective reports should be subject to uncertainty, as students tend to construct an individual narrative for themselves when looking back on positive or negative learning outcomes. In spite of the risk of retrospective bias, the result of the search for explanations, which is repeatedly thought through after the drop-out, is extremely important for us, and the index produced from the instrument no longer highlights the individual reasons or explanations from this narrative, but rather, in aggregate, expresses the fact that negative experiences began to dominate before the negative event. For the other group of students, who are still students in higher education, the high value of this index is interpreted as a reliable predictor, a precursor to dropout. Our results show that the most influential factors that increase and decrease the likelihood of negative experiences are found in the student’s sociodemographic characteristics, their motivation to study, and their network of contacts.

The results of the present analysis show that male students are more likely to have negative or threatening experiences that indicate a drift toward dropout. However, among active students, gender does not appear to significantly influence the perception of risk factors. This discrepancy between active students and dropouts may be explained by the fact that male students who remain enrolled in higher education do not perceive risk factors to an above-average extent. Continuing students, regardless of gender, do not recognize these difficulties at a critical level, which suggests that their awareness of potential threats to academic progression is lower. This false sense of security may paradoxically contribute to an increased dropout risk among men. If male students do not consciously recognize or acknowledge these challenges while they are enrolled, they may be less likely to develop coping strategies or seek support in time. This unawareness effect can lead to an accumulation of difficulties that may eventually push them toward dropping out. In contrast, students who are more aware of the risks – often due to stronger academic socialization or support networks – may have a better chance of addressing these challenges proactively, thereby reducing their dropout risk. This dynamic highlights the importance of not only identifying at-risk groups but also understanding the role of perception and self-awareness in shaping students’ academic trajectories. This interpretation aligns with previous findings on gendered differences in academic risk perception and persistence. Studies have shown that male students are generally less likely to acknowledge academic difficulties, underestimate long-term risks, and seek institutional support, which may explain their higher dropout rates despite similar levels of objective disadvantage (Fényes, 2010; Kovács et al., 2019).

Parental educational attainment is known to be a factor that can influence academic careers over a very long period. After the turn of the millennium, several previous research findings have pointed to the influence of maternal educational attainment (Fényes, 2010; Pusztai, 2015b). In the case of dropouts, the higher the mother’s educational attainment, the more aware the student is of the threatening signs that predict dropout. Mothers talk more and study more with their children, and maternal education can contribute to important dimensions of literacy and school career, such as book reading and aspiration to further education, helping to develop realistic situation assessment and reflectivity. In retrospect, the children of mothers with no more than a school leaving certificate were much less able to identify these risk factors than the children of parents with a higher education diploma. The children of mothers with no school-leaving qualifications, on the other hand, were less reflective of the risk of dropping out than the children of mothers with a higher education diploma, but somewhat more reflective than the children of mothers with a high school degree. This may be explained by the fact that the children with higher education of mothers with primary education are so-called resilient students and thus more consciously struggle through their studies than the children of the majority of parents with a degree, who have a normal background (Ceglédi, 2022).

However, the mother’s education may be a suppressor factor in the analysis, masking the effect of the institution, field of education, and degree. In the present analysis, the field of education is not included, but mothers with higher education are more likely to send their children to more prestigious, selective institutions, while mothers with lower education are more likely to send their children to more secure, less prestigious and attractive institutions and majors. The children of higher-educated mothers may face more difficulties in more demanding, selective, and difficult majors (Csók & Pusztai, 2023).

Among the active students, maternal education does not make a difference in terms of the perception of dropout risk, but here another dimension of family status, the financial situation of the student’s family, namely the poor subjective financial situation, influences the students’ perception of risk. The more unfavorable the students perceive the financial situation of their family, the more they perceive problems that make it difficult to continue in higher education. One possible explanation for this is that financial difficulties in themselves disadvantage students in several ways, for example, if they have poorer access to equipment (digital tools, internet access), poorer learning and living conditions (accommodation to ensure a quiet preparation), or if they have to take paid work, this clearly leads to a more difficult academic career. However, the degree of financial hardship matters. It is a very serious threat to a student’s career if they are unable to cover everyday expenses. In this context, financial support policies play a crucial role in mitigating dropout risks. In Hungary, state-funded students are exempt from tuition fees and can apply for social scholarships, while academic scholarships are only available to those in the top decile of academic performance. Expanding access to financial aid – through higher social and academic scholarships, as well as additional targeted support for students in need – could alleviate financial insecurity and reduce the likelihood of dropout. Ensuring broader eligibility for financial assistance and providing institutional financial guidance programs could further support students in managing their economic challenges effectively.

An important new finding is that parental involvement is significantly the strongest factor in reducing the likelihood of accumulating experiences that jeopardize academic progress for both dropouts and active students. The beneficial, supportive role of parental involvement has been clearly identified in the literature, but research on its role in public education has already indicated that parental involvement is inversely related to age and school level. The independent, positive effect of family support has also been previously identified as a factor behind student success (Pusztai, 2019), and the present results confirm that those who receive more parental attention during their years of higher education face fewer dropout risk factors than average. Parental involvement has also been identified as a protective factor among dropouts, but, as our results show, it is not sufficient to prevent dropout. Among active students, however, it has been identified as the strongest protective factor that has been shown to be effective overall. However, while family support plays a crucial role in mitigating dropout risks, it is essential to distinguish between institutional and family-level interventions. Institutional strategies – such as mentoring programs, financial aid policies, and academic counseling – complement parental involvement by providing structured support that directly addresses academic and financial challenges. At the family level, more conscious parental engagement could further strengthen students’ resilience. Parents could pay closer attention to their children’s academic progress, engage in more frequent conversations about their experiences, and provide emotional and practical support to help them navigate challenges. A more nuanced approach that differentiates these levels of intervention could enhance targeted policies, ensuring that both universities and families contribute effectively to student retention.

Among dropouts, the intention with which a student enters higher education has a significant influence on the accumulation of experiencing risk factors. The theoretical basis for this phenomenon can be traced back to Clark and Trow’s (1966) typology, which identified archetypal student orientations based on their attitudes toward academic norms and institutional expectations. Their qualitative study highlighted how different motivations shape student behavior, including levels of academic commitment and conformity to university norms. Our findings align with this framework, demonstrating that Hungarian students exhibit similar patterns in their approach to higher education, which in turn affects their dropout risk. The nature of motivations at entry takes on a new meaning in the light of dropout. According to the experience of drop-out students, the risk of dropping out is increased by procrastinating, moratorium-seeking career choices, by uncertain, path-seeking career choices, and by the type of motivation where the student only wants to enter higher education for the sake of social advancement.

In contrast, intrinsic motivation-driven career choice reduces risk perceptions in both subsamples of students. Career choice is a decision process that requires a high degree of conscious cooperation between family and school. Students and families may plan higher education for a variety of reasons, and while gaining time, finding a substitute, and gaining status are existing considerations, they do not always provide enough support for a career in higher education. The desire to acquire knowledge, on the other hand, can be an independent motivator for students to pursue goals in the face of adversity.

Among the institutional factors, intergenerational embeddedness, i.e., collegial and mentoring relationships between teachers and students, is a factor that can also act as a stand-alone factor to mitigate negative experiences. Intergenerational embeddedness is therefore not only a predictor of effectiveness but also a mitigator of the risk of drop-out.

In relation to our hypotheses, we can therefore conclude that the first hypothesis can be partially confirmed, that males are more at risk among students who drop out. Among the social status characteristics, maternal education and subjective financial status increase students’ perception of being at risk, while the motivation to gain knowledge decreases it. A significant finding is that the risk of being at risk for students who are adults is mostly reduced by parental support and significantly reduced by instructor support.

6 Conclusion and Limitations

The lesson of our analysis is that experiences that threaten students’ progression in higher education are not randomly distributed in the student population, but their occurrence is correlated with certain factors. In addition to sociodemographic factors (gender, parental education, and financial situation), there are other factors that play a role in the accumulation of negative experiences that the education system may be able to address. Career choice, the shaping and conscious development of career motivation, and the training of teachers to support students’ academic careers more effectively are factors that higher education institutions should take on board to strengthen student retention. While effective parental support has been widely recognized in international research, it has not yet been a focal point in higher education. Our findings suggest that parental involvement at the university level can have a significant impact on student retention, yet further research is needed to understand its mechanisms and the potential for institutional support. Universities could facilitate this process by organizing parental days and weeks, providing opportunities for parents to gain insight into academic life. Additionally, small group sessions led by faculty members could actively engage parents in research and academic activities, fostering stronger collaboration and shared responsibility in supporting students’ educational trajectories.

While our findings provide valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our sampling method. Snowball sampling may introduce selection bias, as initial respondents are likely to recruit individuals with similar backgrounds and experiences. To mitigate this, we aimed to maximize diversity in the initial seed selection, ensuring that respondents came from different institutions, fields of study, and social backgrounds. Additionally, while our sample is not representative, the applied logistic regression model allows us to control for key background variables, reducing the potential impact of sample selection bias on the interpretation of our findings.

One of the key limitations of this study is its inability to clearly distinguish between manifest and latent causes. Consequently, it remains uncertain whether the respondents have fully processed and interpreted the underlying reasons for their dropout. This should be taken into account when considering the implications of the findings. Furthermore, our results highlight the necessity of longitudinal research to track the long-term effects of educational policy interventions. A longitudinal approach would allow for a more precise assessment of how various policy measures influence student retention and academic success over time, providing a stronger foundation for evidence-based policymaking. Future research should also explore the factors that support student resilience and contribute to reducing dropout risks. A deeper understanding of resilience mechanisms could help design interventions that better equip students to overcome academic challenges. Additionally, it is crucial to examine the role of educators through both qualitative and quantitative research. Investigating faculty attitudes, support strategies, and mentoring practices could provide valuable insights into how university environments can be improved to foster student success.

One further limitation concerns the dropout risk index applied in this study. While the scale was designed to measure perceived dropout risk, many of the items are closely related to students’ academic satisfaction, motivation, and engagement. Thus, the index may not reflect objective dropout probability in a behavioral sense but rather captures subjective academic experiences and emotional responses. These perceptions are nevertheless important, as prior research has shown that perceived dissatisfaction and disengagement are strong predictors of eventual dropout. Still, future research should aim to validate and refine this measure, possibly by combining it with longitudinal behavioral data or by developing scales that more directly assess students’ dropout intentions and actions.

-

Funding information: Project no. 123847 has been implemented with support provided by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the K_17 funding scheme. The research on which this article is based has been implemented by the MTA-DE-Parent-Teacher Cooperation Research Group and with the support provided by the Research Programme for Public Education Development of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the content of the manuscript and consented to its submission, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; methodology: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; investigation: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; data curation: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; writing – original draft preparation: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; writing – review and editing: G.P., A.H., and C.C.; and visualization, G.P., A.H., and C.C.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Institutional review board statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the School Ethics Committee of Doctoral Program on Educational Sciences at the University of Debrecen (protocol code 1/2022 and date of approval: March 9, 2022).

-

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was not required for the study.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Astin, A. W., & Antonio, A. L. (2011). Assesment for excellence. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.Search in Google Scholar

Boudon, R. (2013). Beiträge zur allgemeinen Theorie der Rationalität. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, education and cultural change (pp. 71–105). London: Willner Brothers Limited.10.4324/9781351018142-3Search in Google Scholar

Brundsen, V., Davies, M., Shevlin, M., & Bracken, M. (2000). Why do HE students drop out? A test of Tinto’s model. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 24(3), 301–310. doi: 10.1080/030987700750022244.Search in Google Scholar

Ceglédi, T. (2022). Resilience and compensating factors. In G. Pusztai (Ed.), Sociology of education: Theories, communities, contexts (pp. 48–61). Debrecen: Debrecen University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ceglédi, T., Fényes, H., & Pusztai, G. (2022). The effect of resilience and gender on the persistence of higher education students. Social Sciences, 11(3), 93. doi: 10.3390/socsci11030093.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, H.-Y., & Hu, X. Harper, C. E. (2023). Parental involvement and college enrollment: Differences between parents with some and no college experience. Research in Higher Education, 64(8), 1217–1249.10.1007/s11162-023-09744-9Search in Google Scholar

Clark, B. R., & Trow, M. (1966). The organizational context. In T. M. Newcombe & E. K. Wilson (Eds.), College peer groups. (pp. 17–70). Chicago: Aldine.Search in Google Scholar

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Csók, C., Hrabéczy, A., & Németh, D. (2019). Focus on the dropout students’ secondary school experience and career orientation. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 9(4), 708–720. doi: 10.1556/063.9.2019.4.57.Search in Google Scholar

Csók, C., & Pusztai, G. (2023). Stratified student society in higher education fields. Impact of expected earning on students’ career. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 12(1), 40–55. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2023.1.40.Search in Google Scholar

Dotterer, A. M. (2022). Diversity and complexity in the theoretical and empirical study of parental involvement during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Educational Psychologist, 57(4), 295–308. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2129651.Search in Google Scholar

Fényes, H. (2010). School efficiency of boys and girls in a borderland region of Hungary. Review of Sociology, 6(1), 51–77.Search in Google Scholar

Fényes, H. (2022). Differences and rivalry: Gender in education. In G. Pusztai (Ed.), Sociology of education: Theories, communities, contexts (pp. 56–75). Debrecen: Debrecen University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Győri, K., & Pusztai, G. (2022). Exploring the relational embeddedness of higher educational students during Hungarian emergency remote teaching. Frontiers in Education, 7, 814168. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.814168.Search in Google Scholar

Hagedorn, L. S. (2012). How to define retention: A new look at an old problem. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention: Formula for student success (pp. 81–99). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.10.5040/9798216414476.ch-004Search in Google Scholar

Heublein, U. (2014). Student drop-out from German higher education institutions. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 497–513. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12097.Search in Google Scholar

Hrabéczy, A., & Csók, C. (2023). Career choice along the student’s study path in higher education. IPSZIN, 1(1), 55–66.Search in Google Scholar

Kaiser, F., Jongbloed, B., Unger, M., & Zeemann, M (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe Annex 4: National study success profiles. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/12be15b0-0dce-11e6-ba9a-01aa75ed71a1.0001.01/DOC_1.Search in Google Scholar

Keller, T., & Róbert, P. (2016). Inequality in educational returns in Hungary. In Education, occupation and social origin (pp. 49–64). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781785360459.00009Search in Google Scholar

Kovács, K., Ceglédi, T., Csók, C., Demeter-Karászi, Z., Dusa, Á. R., Fényes, H., … Váradi, J. (2019). Lemorzsolódott hallgatók 2018. Debrecen: CHERD-Hungary.Search in Google Scholar

McCarron, G. P., & Inkelas, K. K. (2006). The gap between educational aspirations and attainment for first-generation college students and the role of parental involvement. Journal of College Student Development, 47(5), 534–549. doi: 10.1353/csd.2006.0059.Search in Google Scholar

Miskolczi, P., Bársony, F., & Király, G. (2018). Hallgatói lemorzsolódás a felsőoktatásban: elméleti, magyarázati utak és kutatási eredmények összefoglalása. Iskolakultúra, 28(3–4), 87–105.Search in Google Scholar

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2005.11772296.Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G. (2015a). Pathways to success in higher education. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH.10.3726/978-3-653-05577-1Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G. (2015b). The contribution of secondary schools to the career choice. In G. Pusztai & T. Ceglédi (Eds.), Professional Calling in Higher Education: Challenges of Teacher Education in the Carpathian Basin (pp. 98–117). Nagyvárad–Budapest: Partium Press, Personal Problems Solution, New Mandate Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G. (2019). The role of intergenerational social capital in diminishing student attrition. Journal of Adult Learning, Knowledge and Innovation, 3(1), 20–26.10.1556/2059.02.2018.04Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G., Demeter-Karászi, Z., Alter, E., Marincsák, R., & Dabney-Fekete, I. D. (2022a). Administrative data analysis of student attrition in hungarian medical training. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 317. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03276-z.Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G., Fényes, H., & Kovács, K. (2022b). Factors influencing the chance of dropout or being at risk of dropout in higher education. Education Sciences, 12(11), 804. doi: 10.3390/educsci12110804.Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G., & Kovács, K. (2021). Válaszúton: A perzisztenssé, rizikóssá vagy lemorzsolódóvá válás esélyének vizsgálata. In G. Pusztai & F. Szigeti (Eds.), Lemorzsolódási kockázat és erőforrások a felsőoktatásban (pp. 38–56). Debrecen: CHERD-Hungary.Search in Google Scholar

Pusztai, G., & Szigeti, F. (Eds.). (2021). Előrehaladás és lemorzsolódási kockázat a felsőoktatásban. Debrecen: CHERD-Hungary.Search in Google Scholar

Sciarra, D. T., Seirup, H. J., & Sposato, E. (2016). High school predictors of college persistence: The significance of engagement and teacher interaction. Professional Counselor, 6(2), 189–202. doi: 10.15241/ds.6.2.189.Search in Google Scholar

Tierney, W. G. (2000). Power, identity, and the dilemma of college student departure. In J. M. Braxton (Ed.), Reworking the student departure puzzle (pp. 213–234). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.10.2307/j.ctv176kvf4.14Search in Google Scholar

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education. A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125. doi: 10.2307/1170024.Search in Google Scholar

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226922461.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Tódor, I. (2022). Rational choice theories and school careers. In G. Pusztai (Ed.), Sociology of education: Theories, communities, contexts (pp. 43–55). Debrecen: Debrecen University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tóth, D. A., Szemerszki, M., Ceglédi, T., & Máté-Szabó, B. (2019). The different patterns of the dropout according to the level and the field of education. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 9(4), 257–69.10.1556/063.9.2019.1.23Search in Google Scholar

Vossensteyn, H., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., & Wollscheid, S. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe: Main report. Luxembourg: European Commission.Search in Google Scholar

Wartman, K. L., & Savage, M. (2015). Parent and family engagement in higher education. ASHE, 41(6), 1–94.10.1002/aehe.20024Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, D. S. S., Sax, L. J., & Harper, C. E. (2009). Parental engagement and contact in the academic lives of college students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 46(2), 325–358. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.6044.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part II

- Formation of STEM Competencies of Future Teachers: Kazakhstani Experience

- Technology Experiences in Initial Teacher Education: A Systematic Review

- Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model to Enhance Nationalistic Insight

- Delimiting the Future in the Relationship Between AI and Photographic Pedagogy

- Research Articles

- Examining the Link: Resilience Interventions and Creativity Enhancement among Undergraduate Students

- The Use of Simulation in Self-Perception of Learning in Occupational Therapy Students

- Factors Influencing the Usage of Interactive Action Technologies in Mathematics Education: Insights from Hungarian Teachers’ ICT Usage Patterns

- Study on the Effect of Self-Monitoring Tasks on Improving Pronunciation of Foreign Learners of Korean in Blended Courses

- The Effect of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Soft Skill Development: Quasi-Experimental Study

- The Impact of Perfectionism, Self-Efficacy, Academic Stress, and Workload on Academic Fatigue and Learning Achievement: Indonesian Perspectives

- Revealing the Power of Minds Online: Validating Instruments for Reflective Thinking, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulated Learning

- Culturing Participatory Culture to Promote Gen-Z EFL Learners’ Reading Proficiency: A New Horizon of TBRT with Web 2.0 Tools in Tertiary Level Education

- The Role of Meaningful Work, Work Engagement, and Strength Use in Enhancing Teachers’ Job Performance: A Case of Indonesian Teachers

- Goal Orientation and Interpersonal Relationships as Success Factors of Group Work

- A Study on the Cognition and Behaviour of Indonesian Academic Staff Towards the Concept of The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- The Role of Language in Shaping Communication Culture Among Students: A Comparative Study of Kazakh and Kyrgyz University Students

- Lecturer Support, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, and Statistics Anxiety in Undergraduate Students

- Parental Involvement as an Antidote to Student Dropout in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of Dropout Risk

- Enhancing Translation Skills among Moroccan Students at Cadi Ayyad University: Addressing Challenges Through Cooperative Work Procedures

- Socio-Professional Self-Determination of Students: Development of Innovative Approaches

- Exploring Poly-Universe in Teacher Education: Examples from STEAM Curricular Areas and Competences Developed

- Understanding the Factors Influencing the Number of Extracurricular Clubs in American High Schools

- Student Engagement and Academic Achievement in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Psychosocial Development

- The Effects of Parental Involvement toward Pancasila Realization on Students and the Use of School Effectiveness as Mediator

- A Group Counseling Program Based on Cognitive-Behavioral Theory: Enhancing Self-Efficacy and Reducing Pessimism in Academically Challenged High School Students

- A Significant Reducing Misconception on Newton’s Law Under Purposive Scaffolding and Problem-Based Misconception Supported Modeling Instruction

- Product Ideation in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Insights on Design Process Through Shape Coding Social Robots

- Navigating the Intersection of Teachers’ Beliefs, Challenges, and Pedagogical Practices in EMI Contexts in Thailand

- Business Incubation Platform to Increase Student Motivation in Creative Products and Entrepreneurship Courses in Vocational High Schools

- On the Use of Large Language Models for Improving Student and Staff Experience in Higher Education

- Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students With Divorced Parents and Their Impact on Learning Motivation

- Twenty-First Century Learning Technology Innovation: Teachers’ Perceptions of Gamification in Science Education in Elementary Schools

- Exploring Sociological Themes in Open Educational Resources: A Critical Pedagogy Perspective

- Teachers’ Emotions in Minority Primary Schools: The Role of Power and Status

- Investigating the Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intention to Use Chatbots in Primary Education in Greece

- Working Memory Dimensions and Their Interactions: A Structural Equation Analysis in Saudi Higher Education

- A Practice-Oriented Approach to Teaching Python Programming for University Students

- Reducing Fear of Negative Evaluation in EFL Speaking Through Telegram-Mediated Language Learning Strategies

- Demographic Variables and Engagement in Community Development Service: A Survey of an Online Cohort of National Youth Service Corps Members

- Educational Software to Strengthen Mathematical Skills in First-Year Higher Education Students

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Fostering Student Creativity in Kazakhstan

- Review Articles

- Current Trends in Augmented Reality to Improve Senior High School Students’ Skills in Education 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review

- Exploring the Relationship Between Social–Emotional Learning and Cyberbullying: A Comprehensive Narrative Review

- Determining the Challenges and Future Opportunities in Vocational Education and Training in the UAE: A Systematic Literature Review

- Socially Interactive Approaches and Digital Technologies in Art Education: Developing Creative Thinking in Students During Art Classes

- Current Trends Virtual Reality to Enhance Skill Acquisition in Physical Education in Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: A Systematic Review

- Understanding the Technological Innovations in Higher Education: Inclusivity, Equity, and Quality Toward Sustainable Development Goals

- Perceived Teacher Support and Academic Achievement in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review

- Mathematics Instruction as a Bridge for Elevating Students’ Financial Literacy: Insight from a Systematic Literature Review

- STEM as a Catalyst for Education 5.0 to Improve 21st Century Skills in College Students: A Literature Review

- A Systematic Review of Enterprise Risk Management on Higher Education Institutions’ Performance

- Case Study

- Contrasting Images of Private Universities

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part II

- Formation of STEM Competencies of Future Teachers: Kazakhstani Experience

- Technology Experiences in Initial Teacher Education: A Systematic Review

- Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model to Enhance Nationalistic Insight

- Delimiting the Future in the Relationship Between AI and Photographic Pedagogy

- Research Articles

- Examining the Link: Resilience Interventions and Creativity Enhancement among Undergraduate Students

- The Use of Simulation in Self-Perception of Learning in Occupational Therapy Students

- Factors Influencing the Usage of Interactive Action Technologies in Mathematics Education: Insights from Hungarian Teachers’ ICT Usage Patterns

- Study on the Effect of Self-Monitoring Tasks on Improving Pronunciation of Foreign Learners of Korean in Blended Courses

- The Effect of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Soft Skill Development: Quasi-Experimental Study

- The Impact of Perfectionism, Self-Efficacy, Academic Stress, and Workload on Academic Fatigue and Learning Achievement: Indonesian Perspectives

- Revealing the Power of Minds Online: Validating Instruments for Reflective Thinking, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulated Learning

- Culturing Participatory Culture to Promote Gen-Z EFL Learners’ Reading Proficiency: A New Horizon of TBRT with Web 2.0 Tools in Tertiary Level Education

- The Role of Meaningful Work, Work Engagement, and Strength Use in Enhancing Teachers’ Job Performance: A Case of Indonesian Teachers

- Goal Orientation and Interpersonal Relationships as Success Factors of Group Work

- A Study on the Cognition and Behaviour of Indonesian Academic Staff Towards the Concept of The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- The Role of Language in Shaping Communication Culture Among Students: A Comparative Study of Kazakh and Kyrgyz University Students

- Lecturer Support, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, and Statistics Anxiety in Undergraduate Students

- Parental Involvement as an Antidote to Student Dropout in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of Dropout Risk

- Enhancing Translation Skills among Moroccan Students at Cadi Ayyad University: Addressing Challenges Through Cooperative Work Procedures

- Socio-Professional Self-Determination of Students: Development of Innovative Approaches

- Exploring Poly-Universe in Teacher Education: Examples from STEAM Curricular Areas and Competences Developed

- Understanding the Factors Influencing the Number of Extracurricular Clubs in American High Schools

- Student Engagement and Academic Achievement in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Psychosocial Development

- The Effects of Parental Involvement toward Pancasila Realization on Students and the Use of School Effectiveness as Mediator

- A Group Counseling Program Based on Cognitive-Behavioral Theory: Enhancing Self-Efficacy and Reducing Pessimism in Academically Challenged High School Students

- A Significant Reducing Misconception on Newton’s Law Under Purposive Scaffolding and Problem-Based Misconception Supported Modeling Instruction

- Product Ideation in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Insights on Design Process Through Shape Coding Social Robots

- Navigating the Intersection of Teachers’ Beliefs, Challenges, and Pedagogical Practices in EMI Contexts in Thailand

- Business Incubation Platform to Increase Student Motivation in Creative Products and Entrepreneurship Courses in Vocational High Schools

- On the Use of Large Language Models for Improving Student and Staff Experience in Higher Education

- Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students With Divorced Parents and Their Impact on Learning Motivation

- Twenty-First Century Learning Technology Innovation: Teachers’ Perceptions of Gamification in Science Education in Elementary Schools

- Exploring Sociological Themes in Open Educational Resources: A Critical Pedagogy Perspective

- Teachers’ Emotions in Minority Primary Schools: The Role of Power and Status

- Investigating the Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intention to Use Chatbots in Primary Education in Greece

- Working Memory Dimensions and Their Interactions: A Structural Equation Analysis in Saudi Higher Education

- A Practice-Oriented Approach to Teaching Python Programming for University Students

- Reducing Fear of Negative Evaluation in EFL Speaking Through Telegram-Mediated Language Learning Strategies

- Demographic Variables and Engagement in Community Development Service: A Survey of an Online Cohort of National Youth Service Corps Members

- Educational Software to Strengthen Mathematical Skills in First-Year Higher Education Students

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Fostering Student Creativity in Kazakhstan

- Review Articles

- Current Trends in Augmented Reality to Improve Senior High School Students’ Skills in Education 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review

- Exploring the Relationship Between Social–Emotional Learning and Cyberbullying: A Comprehensive Narrative Review

- Determining the Challenges and Future Opportunities in Vocational Education and Training in the UAE: A Systematic Literature Review

- Socially Interactive Approaches and Digital Technologies in Art Education: Developing Creative Thinking in Students During Art Classes

- Current Trends Virtual Reality to Enhance Skill Acquisition in Physical Education in Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: A Systematic Review

- Understanding the Technological Innovations in Higher Education: Inclusivity, Equity, and Quality Toward Sustainable Development Goals

- Perceived Teacher Support and Academic Achievement in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review

- Mathematics Instruction as a Bridge for Elevating Students’ Financial Literacy: Insight from a Systematic Literature Review

- STEM as a Catalyst for Education 5.0 to Improve 21st Century Skills in College Students: A Literature Review

- A Systematic Review of Enterprise Risk Management on Higher Education Institutions’ Performance

- Case Study

- Contrasting Images of Private Universities