Abstract

Despite continued efforts to address this issue, many students still exhibit misunderstandings regarding Newton’s laws. These misconceptions include beliefs, such as every movement requires a force, that force is directly proportional to velocity, and that action–reaction forces can differ in magnitude. To mitigate these misunderstandings, innovative teaching strategies like cognitive conflict approaches are essential. This study utilized a scenario-based scaffolding method, integrating common student misconceptions early in the modeling instruction (MI) process. This process requires scaffolding and authentic problems. To date, scaffolding in MI learning was not initially designed with students’ diversity in mind. The problems given by teachers in the early MI emphasize natural phenomena or symptoms that are aligned with the learning objectives in the curriculum. In contrast to what has been done, the force concept inventory (FCI) and interviews were used to pinpoint these misconceptions. The FCI was also administered as both a pretest and posttest to evaluate students’ reasoning abilities. Additionally, interviews provided deeper insights into the effectiveness of the instructional model in addressing persistent misconceptions. The combined data from interviews and test results revealed a significant improvement in students’ understanding of Newton’s laws, with a 65.42% reduction in misconceptions. The designed MI with scaffolding and the problems based on students’ misconceptions, fostering new and correct thinking patterns of students in responding to the natural phenomena in their daily lives.

1 Introduction

Newton’s laws are fundamental to an understanding of mechanics (Chow, 2024; Gates, 2014; Kalies & Do, 2023; van der Linden & van Joolingen, 2016). The comprehension of kinematics, effort and energy, power, impulse and momentum, the rotation of rigid bodies, and balance is contingent upon an understanding of Newton’s laws (Wilson, 2020). In the event that students lack a sufficient understanding of Newton’s law, they will be unable to grasp the law of conservation of momentum (Low & Wilson, 2017). The material of Newton’s laws is closely connected to the experiences of students in their daily lives. Besides, the rectification of erroneous beliefs pertaining to Newton’s laws has the potential to alter students’ perspectives on their everyday experiences (Ding, Zhu, Bian, & Bao, 2024; El-Helou & Kalman, 2023; Engelman & Koenig, 2018). The fundamental concept underlying Newton’s laws is the concept of force. In the field of mechanics, the concept of force represents the primary means of understanding the character of an object’s motion. A lack of comprehension or erroneous beliefs regarding the concept of force will inevitably lead to an inability to grasp the principles of motion (Goren & Galili, 2019).

Many ways to eradicate the misconceptions of Newton’s law have been performed and reported (Bao, Hogg, & Zollman, 2002; Clement, 1982; Gates, 2014; Hestenes, Wells, & Swackhamer, 1992; Kelly, 2011). In the last 6 years, efforts to erode the focus have been carried out with various approaches (Aksit & Wiebe, 2020; Balta & Eryılmaz, 2017; de Mello Forato, 2018; Fazio & Battaglia, 2019; Fulmer, 2015; Galili, Bar, & Brosh, 2016). Aksit and Wiebe (2020) concluded that the exploration of force and motion concepts can be performed by technology, but requires scaffolding in an effort to erode the misconceptions. Balta and Eryılmaz (2017) were able to eradicate 39% of the misconceptions of Newtonian dynamics material with a counterintuitive dynamics test. De Mello Forato (2018) developed an approach to learning that focused on ontological and epistemological aspects. This approach resulted in the identification and resolution of student misconceptions, though it should be noted that these misconceptions were not authentic. Fazio and Battaglia (2019) eradicated students’ misconceptions about Newtonian Mechanics through Cluster Analysis of Student Answers through force concept inventory (FCI). The results showed that cluster analysis proved to be a useful tool to identify latent structures in students’ conceptual understanding. Fulmer (2015) examined three learning strategies, and the results were tested with FCI. As a result, the best learning is by involving students’ contextual problems. Galili et al. (2016) concluded that good learning to reduce misconceptions entails a consideration of the epistemological domain. However, when dealing with the real world, students still use their naive theories in responding to these real symptoms (Kryjevskaia & Grosz, 2020; Leta, Ayele, & Kind, 2021; Santos & dos Silva, 2021). This phenomenon leads to the conclusion that eroding misconceptions related to Newton’s laws has not been effectively carried out by relying on learning based on students’ naive theories.

As a result, the misconceptions phenomena of Newton’s law are still reported by the researchers, such as a student’s assumption that every moving object requires a force acting on it (Ding et al., 2024; Hecht, 2015; Lee & Leegwater, 2011; Rahmawati, Jumadi, Kuswanto, & Oktaba, 2020; Robertson, Goodhew, Scherr, & Heron, 2021). Force causes objects to continue moving at a certain speed (Itza-Ortiz, Rebello, & Zollman, 2004; Putri, Sundari, Mufit, & Dewi, 2024; Robertson et al., 2021; Sujarittham & Tanamatayarat, 2019). When an object is thrown upward, there is a force that points upward according to the force of the hand that throws upward (Robertson et al., 2021). Objects moving in a curved tube, when exiting the tube, the object’s motion remains curved. This happens because students build the assumption of a curved pushing force (Robertson et al., 2021). Students treat action–reaction force pairs from Newton’s third law as if they were acting on separate objects and can be added as in Newton’s second law to obtain the total force (Dedic et al., 2010; Low & Wilson, 2017).

The research related to the phenomenon of misconceptions related to Newton’s laws has been previously documented by researchers. These phenomena include the assumption from students that for every movement, there must be a force (Hecht, 2015; Lee & Leegwater, 2011; Rahmawati et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2021). The application of force results in the continued movement of objects at a specified velocity (Itza-Ortiz et al., 2004; Robertson et al., 2021; Sujarittham & Tanamatayarat, 2019). As an object is thrown upward, a force is directed upward, in accordance with the force applied to the object at the moment it is thrown (Robertson et al., 2021). When an object moves in a curved tube and then exits the tube, its motion remains curved because students build the assumption of a curved pushing force (Robertson et al., 2021). Students tend to conceptualize action–reaction force pairs from Newton’s third law as if they are acting on separate objects, which can be added together as in Newton’s second law to obtain the total force (Dedic et al., 2010; Low & Wilson, 2017).

The attempts to challenge and dispel misconceptions related to Newton’s laws have been undertaken and documented (Bao et al., 2002; Clement, 1982; Gates, 2014; Hestenes et al., 1992; Kelly, 2011). In the past 6 years, the efforts to erode misconceptions have been focused on various approaches (Aksit & Wiebe, 2020; Balta & Eryılmaz, 2017; de Mello Forato, 2018; Fazio & Battaglia, 2019; Fulmer, 2015; Galili et al., 2016). Aksit and Wiebe (2020) concluded that the concept of force and motion can be explored using IT, but it requires the application of scaffolding to eradicate the misconception. Meanwhile, Balta and Eryılmaz (2017) demonstrated the efficacy of a counterintuitive dynamics test to lower 39% of students’ misconceptions of Newtonian dynamics. De Mello Forato (2018) formulated a learning approach with consideration of the ontological and epistemological aspects. Fazio and Battaglia (2019) employed cluster analysis of student responses to the force and motion concept inventory (FCI) to identify and minimize the misconceptions concerning Newtonian mechanics among students. That study concluded that cluster analysis is effective for discerning the underlying structures in students’ conceptual misunderstanding. Fulmer (2015) conducted an analysis of three learning strategies using FCI. The findings indicated that the most effective learning involves engaging students to address the contextual problem. Galili et al. (2016) posited that effective learning necessitates an emphasis on the epistemological domain to facilitate the dissolution of misconception. However, in practical situations, students tend to apply their initial, unsophisticated explanation when confronted with these phenomena (Kryjevskaia & Grosz, 2020; Leta et al., 2021; Santos & dos Silva, 2021). The findings from the aforementioned studies suggest that the eradication of misconceptions related to Newton’s laws has not been effective, with the learning relying on students’ naïve theories.

The misconceptions concerning Newton’s laws cannot be effectively addressed through teacher-centered learning (Fadaei & Mora, 2015; Crogman, Peters, & TrebeauCrogman, 2018). Instead, the learning that can decrease misconceptions involves the formation of conceptual conflicts, demonstrations, and experiments in the classroom (Crogman & Trebeau Crogman 2016, 2018; Crogman, Crogman, Warner, Mustafa, & Peters, 2015; Ha & Kim, 2020). In the teaching of Newton’s laws, the second and third laws are mostly presented as separate entities (Low & Wilson, 2017). It is uncommon that the three laws are integrated to solve a problem during the learning process (Fulmer, 2015). This leads students to revert to their naïve understanding when faced with real-world issues (Kryjevskaia & Grosz, 2020; Lutz, Sylvester, Oliver, & Herrington, 2017). Meanwhile, the comprehensive application of Newton’s law is essential, particularly in investigating daily phenomena (Wilson, 2020), for example, in the analysis of the force of a body swinging at its lowest position. Newton’s third law is invoked to ascertain the object’s interaction with its surrounding environment, for determining the force on it. Further, to ensure that the observer is in an inertial frame, Newton’s first law may be invoked, along with Newton’s second law, to obtain the desired result, generating

In addition, student-centered, real-world, problem-based, and project-based learning constitutes the modeling instruction (MI) (Dounas-Frazer & Lewandowski, 2018; Phillips, Gouvea, Gravel, Beachemin, & Atherton, 2023). MI is defined as the combination of evidence and model-based reasoning to facilitate comprehension of everyday phenomena (Russ & Odden, 2017). It is aligned with the concept of modeling in physics, which involves a combination of accurate information with experimentation (Koponen, 2007). MI is a pedagogical approach that emulates the practice of science, facilitating authentic engagement with scientific concepts among learners (Brewe & Sawtelle, 2018; Dominguez, De La Garza, Quezada-Espinoza, & Zavala, 2023). If a child wishes to shoot a bird, they will aim directly at the bird, rather than above it, due to the influence of gravity. This results in the student’s development of naïve theory, suggesting that bullets travel in a straight line. MI serves to bridge the gap between the real world, which potentially provokes students’ naïve theory, and the correct scientific rule (Basu, Biswas, & Kinnebrew, 2017). Further, experimentation is a crucial aspect of MI, while in experimental studies, it is essential to control variables. In many instances, when students engage in authentic experiments involving everyday occurrences, there are confounding variables that must be accounted for and controlled (Dias, Carvalho, & Vianna, 2016).

The Theory of Theory is essentially a conceptual framework for understanding misconceptions (“Misconceptions,” 2014; Posner, 1982). The misconception theory claims that there is a robust and stable incorrect structure in students’ mind that is resistant to disruption by contextual factors (Von Aufschnaiter & Rogge, 2010). Therefore, before learning session, teachers need to discover what misconceptions their students have in their brain structure. Once identified, teachers’ focus is on removing the misconception theory and replacing it with the correct theory. FCI emerged at a time when the theory of misconception was more dominant. As a result, many understand that the FCI is a tool for detecting students’ solid and stable misconception structures that are difficult to disrupt by context. Those who believe in the Theory of Knowledge in Pieces (KiP) claim that students need the pieces of knowledge that may be irrelevant or inappropriate depending on when those pieces are applied (“Knowledge-in-Pieces—Andrea A. diSessa, David Hammer,” 2020). Within the KiP framework, this theory develops students’ knowledge into a more coherent and comprehensive understanding. MI serves as a tool for thinking in developing learning strategies, with the goal of constructing models and understanding how to use them (Joyce & Calhoun, 2024). Therefore, the mindset of MI learning aligns with the KiP theory. Over time, misconceptions have been redefined, not as robust and stable incorrect structures resistant to contextual disruption, but rather as flawed thinking. Consequently, the use of the FCI instrument remains relevant for detecting students’ misconceptions within the context of MI-based learning.

In the learning stage, MI requires that the teacher assume a scaffolding role to facilitate the attainment of learning objectives (Belcher, 2017, Tian, Xu, & Mao, 2024). This aspect is frequently overlooked since teachers only sporadically assume the role of scaffolding (Mustofa & Asmichatin, 2019). Consequently, students are unable to adhere to the full spectrum of MI learning stages. Consequently, human scaffolding emerges as the most prevalent form of scaffolding. Meanwhile, as the world of learning is already equipped with computers, the scaffolding designed is conceptual and procedural scaffolding.

At the outset of this MI learning, students engage in observation of natural phenomena in small groups, with guidance from the instructor (Brewe & Sawtelle, 2018). At this stage, teachers frequently present natural phenomena that align with the learning objectives outlined in the curriculum (Barlow, Frick, Barker, & Phelps, 2014; Jackson, Dukerich, & Hestenes, 2008; McPadden & Brewe, 2017; Vasconcelos & Kim, 2020). Additionally, teachers present problems based on findings from research papers (Kusairi, Imtinan, & Swasono, 2019). Consequently, students will persist in employing their naïve theory to address their everyday challenges, as these issues consistently prompt them to utilize their naïve theory (Kryjevskaia & Grosz, 2020). Therefore, this present study employed MI with scaffolding from the outset of learning, along with problems based on students’ naïve theories.

Therefore, this study aims to ascertain the efficacy of MI with scaffolding that had been designed at the outset of the learning process. Besides, the learning also adopted problems based on students’ naïve theory to enhance students’ understanding and reduce their misconception of Newton’s law. It analyzes the increase in scores from the pretest to the posttest and the reduction of students’ misconceptions of the material of Newton’s laws, as measured by the FCI instrument.

2 Research Method

2.1 Research Design

In the initial phase of the study, a pretest was administered to ascertain the specific areas of misunderstanding that were prevalent among the students. FCI was utilized to identify students’ misconceptions (Hestenes et al., 1992). Students were required to select their preferred option on the FCI, along with the rationale. This approach was selected to ascertain the underlying conceptions that may be present in students’ cognitive frameworks. The second stage involved conducting an interview to gain further insight into the rationale behind students’ responses. This approach has been recommended as a means of gaining more comprehensive information (Johnson & Christensen, 2017; Low & Wilson, 2017; Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017). The interview was employed to further substantiate students’ conceptions pertaining to Newton’s law. This section focused on investigating students’ misconceptions and their underlying causes.

The third stage was designing the MI learning, which was tailored to the fundamental issues. The learning was also supported by scaffolding that had been designed from the outset of the learning process. MI is a student-centered learning approach that integrates real context into the classroom, as well as employing problem-based and project-based learning strategies (Dounas-Frazer & Lewandowski, 2018). MI is a pedagogical approach that integrates evidence-based reasoning with model-based reasoning to facilitate comprehension of everyday phenomena (Russ & Odden, 2017). The integration of real-world context into the classroom can be effectively facilitated through procedural and conceptual scaffolding. Meanwhile, the combination of evidence and model-based reasoning to understand everyday phenomena is likely to be more engaging for students if the problems presented are problems based on students’ naive theories. In the fourth stage, MI learning was conducted with the aid of scaffolding that had been meticulously designed. Besides, the learning also used problems based on students’ naive theories. The underlying principle of this learning is counter-cognitive, as it seeks to disassemble the naive theory of students. The essence of counter-cognitive lies in the stage of designing and conducting experiments to prove students’ misconceptions (Evangelou & Kotsis, 2019). In the fifth stage, a posttest with the FCI was conducted to gain students’ responses and the rationale. In the sixth stage, an interview was conducted to gain further insight into students’ selected options. This interview was used to examine the effectiveness and constraints of learning when students completed the pretest and posttest, particularly in relation to alterations in the students’ responses. Interviews were utilized to investigate the limitations of learning when they took pretests and posttests, yet still selected the same but wrong option, changed options that remained incorrect, or even changed options to be incorrect. All the process of research planning is presented in Figure 1.

Research planning.

2.2 Research Instrument

The instrument utilized to obtain the quantitative data was the FCI with reasoning. The FCI is a 30-item instrument that has been validated and field tested (Savinainen & Viiri, 2008). FCI has been employed on 1,500 senior high school students and over 500 college students in the United States of America to discern their erroneous beliefs regarding motion and force material (Hestenes et al., 1992). In general, the FCI encompasses a variety of topics, including force, kinematics, Newton’s first law, Newton’s second law, Newton’s third law, the action–reaction principle, and types of forces (Poutot & Blandin, 2015; Wells et al., 2019). Each item on the FCI is accompanied by five answer options. Each answer option represents the student’s conception of the material. The correct answer options represent students’ accurate conceptual understanding, whereas incorrect answer options indicate the presence of misconceptions. Therefore, FCI has been employed for over two decades to identify students’ misconceptions and has remained a viable instrument for this purpose, as evidenced by its consistently high levels of validity and reliability (Hestenes et al., 1992; Oktarisa, Utami, & Denny, 2017). Furthermore, FCI can be employed for the assessment of learning outcomes (Hestenes et al., 1992; Lee, Connolly, Dancy, Henderson, & Christensen, 2018). It has been subjected to rigorous testing for validity in multiple studies (Coletta, Phillips, & Steinert, 2007; Munfaridah, Sutopo, Sulur, & Asim, 2018; Thornton, Kuhl, Cummings, & Marx, 2009). The initial test demonstrated a 0.9 reliability coefficient, while the final test exhibited a reliability coefficient of 0.81, with an overall reliability of 0.865 (Lasry, Rosenfield, Dedic, Dahan, & Reshef, 2011; Munfaridah et al., 2018). The results of the reliability test demonstrate that the FCI instrument exhibits consistency performance when utilized for assessment purposes. Consequently, the FCI instrument can be adopted to analyze the misconceptions pertaining to motion and force that are commonly encountered in physics learning.

2.3 Quantitative Data Analysis

Quantitative data were obtained through the administration of pretests and posttests. A Wilcoxon signed rank was conducted to assess the differential between the pretest and posttest data, followed by the N-gain test (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007). The percentage of students whose misconceptions were reduced for each question was calculated using the following equation:

RM represents the percentage of students whose misconceptions are reduced for each question, A represents the number of students who answered correctly on the pretest, B represents the number of students who answered correctly on the posttest, C represents the number of students who answered correctly on the pretest and then answered incorrectly on the posttest, D represents the number of students who answered correctly during the pretest but provided an incorrect rationale, and N represents the total number of students (80)

The mean percentage of students exhibiting reduced misconceptions is calculated using the following equation:

RMT represents the average percentage of students whose misconception has been lowered S = total FCI. The FCI instrument consists of 30 items.

To ascertain whether students hold misconceptions, interviews were conducted with two participants (Gerke, 2020). A student was deemed to hold a misconception if both students were identified as such. In the event of a discrepancy, a discussion was held to determine whether the student held a misconception.

The FCI structure encompasses Newton’s law I in questions 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 23, and 24; Newton’s law II in questions 1, 2, 3, 12, 14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26, and 27; Newton’s law III in questions 4, 5, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 28, 29, and 30. For the purposes of qualitative analysis, number 8 was selected as a representative of Newton’s law I, number 21 as a representative of Newton’s law II, and number 15 as a representative of Newton’s law III.

The quantitative data obtained through the pretest and posttest were presented in the form of percentages and statistical analysis. The presentation of percentage data was divided into three categories for each indicator: correct answers, incorrect answers, and no answers. The objective was to ascertain the extent of the percentage change in the number of students in each category between the pretest and posttest. A misunderstanding of Newton’s law was identified through the assumption that an object’s natural state is at a fixed speed. A misconception of Newton’s second law could be identified as a lack of understanding of the concept that a constant force produces a constant acceleration. A further misconception of Newton’s law III was identified through students’ dissimilar misunderstanding of the action–reaction force. The objective of the statistical data presentation was to ascertain the efficacy of MI with designed scaffolding and problems based on students’ conceptual understanding. The data processing was carried out employing statistical testing, which included the Wilcoxon signed-rank difference test followed by the N-gain test (Cohen et al., 2007). The category of N-gain score distribution and the category of N-gain score effectiveness interpretation are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

N-gain score distribution category

| Nilai N-gain | Kategori |

|---|---|

| g > 0.7 | Tinggi |

| 0.3 ≤ g ≤ 0.7 | Sedang |

| g < 0.3 | Rendah |

N-gain score effectiveness interpretation category

| Percentage | Tafsiran |

|---|---|

| <40 | Tidak efektif |

| 40–55 | Kurang efektif |

| 56–75 | Cukup efektif |

| >76 | efektif |

2.4 Qualitative Data Analysis

The interview results were classified into two distinct categories. The data from the initial interview with the entire student population were employed to ascertain whether the students were experiencing any misconceptions. The data from the second interview were employed to ascertain the rationale behind the persistence of the observed behavior, despite the implementation of a structured learning approach and the incorporation of misconception-based challenges. The subjects who were interviewed to ascertain the reasons for their lack of change were those who, during the pretest and posttest, provided incorrect responses, continuously provided incorrect responses, and originally provided correct responses, then changed into incorrect ones. The data from the first and second interviews were employed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of MI learning with designed scaffolding and misconception-based problems.

3 Results and Discussion

A review of the pretest and posttest data revealed that the data were not normally distributed. Consequently, the Wilcoxon signed-rank difference test statistic was employed, yielding a significance value of 0.000 <0.05. This result indicated a statistically significant difference in the mastery of Newton’s laws between the pretest and posttest. This implies that the average posttest score is higher than the average pretest score, thereby supporting the conclusion that the use of MI learning with designed scaffolding and misconception-based problems has a positive effect on students’ understanding of the concept. Further, the mean N-Gain score is 65%, indicating a relatively high level of effectiveness. This falls within the category of relatively effective, as it is between 56 < N-Gain < 75.

Among the 30 misconceptions identified, only 9 were identified as correct conceptions prior to the administration of the test. The results of the interviews indicated that these nine correct conceptions were not supported by sufficient evidence. Consequently, the students provided a random response. Meanwhile, among the 30 misconceptions, 23 were identified as correct conceptions during the posttest. The results of the interviews indicated that all students who provided correct responses had well-founded reasons. The student’s capacity to respond accurately is contingent upon the provision of clear scaffolding in instances where students experience difficulty during the MIs. This enables the elimination of misconceptions, as the problems presented are precisely those that caused student misconceptions. Consequently, the implementation of MI learning with designed scaffolding and misconception-based problems can effectively reduce students’ misconceptions related to Newton’s laws material by 76.67%.

The following section presents a synthesis of the reduction of misconceptions related to Newton’s laws. Question number 8 was selected as a representative of Newton’s law I, number 21 as a representative of Newton’s law II, and number 15 as a representative of Newton’s law III. Question number 8 was selected because a significant proportion of students appear to disregard the concept of inertia, exhibiting a tendency to hold misconceptions about this fundamental principle. Answer choice A for number 8 aims to find out whether students still hold the misconception that the kick completely replaces the impact of inertia, thereby eliminating the initial inertia of the object. In everyday life, students often assume that when an object is moving east and then kicked north, it will continue moving north. The objective of answer choice B is to ascertain whether students possess an accurate understanding of the concept of inertia. When the ball is initially moving eastward and then kicked northward, the impact of the eastward slide remains, necessitating the calculation of the resultant eastward and northward velocities. This results in a trajectory that continues northeastward with a fixed speed, as illustrated by a straight graph. Following the northward kick, the northward force is no longer present, leading to the emergence of a northward velocity component with a fixed magnitude and direction. Answer C is used to determine whether students remain having the misconception that, at the outset of the experiment, the speed is so considerable that it negates the impact of the speed to the east, and that at a certain point, the speed to the north is either zero or reaches a point of exhaustion. Answer D is employed to ascertain whether there are still students who hold the misconception that, subsequent to the kick to the north, the object accelerates to the north. This indicates that students still adhere to the misconception that, in the absence of a force acting upon it, an object will move in a straight line. Answer E is employed to ascertain whether there are still students who hold the misconception that, subsequent to the northward kick, the object decelerates to the north. This indicates that students still have the misconception that, in the absence of a force impeding its motion, an object will move in a straight line. The mindset of answer E is applied by students based on their daily experience: if a ball is kicked, the object moves slowly and finally comes to rest.

Question 21 was selected due to a significant proportion of students continuing to demonstrate difficulty in differentiating between velocity and acceleration in the context of force. The objective of answer A is to ascertain whether students still hold the misconception that constant thrust will gradually disappear. Consequently, the acceleration of the rocket diminishes over time. This perception may occur due to the thrust being directed upward, facing an inhibitory force, namely gravity, which results in a reduction in the acceleration of the rocket. Despite the clarification that the rocket is in outer space, students continue to apply their everyday understanding that an object thrown upward will slow down and eventually come to a standstill at its highest point. The objective of answer B is to ascertain whether students still adhere to the misconception that force is proportional to speed. In their everyday lives, students tend to assume that in order to increase and stabilize the speed of their vehicle at a higher level, they must turn the handlebars of the vehicle more. This increased rotation of the handlebar results in greater speed stabilization at higher speeds. Similarly, answer B aligns with the prevalent misconception among students that the initial velocity (inertia) can be effectively supplanted or negated through the introduction of a novel treatment, namely the thrust force applied to the rocket. The objective of answer C is to ascertain whether students still adhere to the erroneous notion that force is proportional to velocity. If the student selects answer C, it indicates that they still perceive the initial velocity to be in a lateral direction. Consequently, the graph depicts the outcome as a combination of lateral and upward velocities. Possibly, the student believes that the thrust force is canceled out by the force of gravity, resulting in a zero vertical force. In the event that the resultant force is zero, it is possible that the object is moving in a straight line. Answer D is designed to ascertain whether students still hold the misconception that initially, the inertia of the rocket’s sideways motion is dominant, resulting in a straight and regular trajectory to the side. Subsequently, the thrust force accelerates the rocket upward. In their everyday experiences, when a motor begins to move, it typically does so at a slow pace before accelerating to a faster speed. Answer E is designed to ascertain whether students’ conceptions align with the understanding of force presented in the graph. The graph in response E illustrates the resultant between the rocket’s fixed, sideways velocity and the rocket’s increasing, upward velocity or acceleration, with a fixed acceleration. The fixed acceleration of the upward rocket is a consequence of the application of a fixed upward thrust force to the rocket.

Problem number 15 was selected for analysis because numerous students continue to demonstrate an inability to grasp the fundamental principle that the interaction between two objects in any condition invariably results in an identical magnitude of action–reaction force. In question number 15, the mass of the car is less than that of the truck. The interaction occurs when the motion of the two vehicles is accelerated, with the car taking the initiative in the push or collision. The objective of answer A is to ascertain whether the student’s comprehension of Newton’s third law is accurate. Despite the fact that the mass of the car is less than that of the truck, the interaction occurs when the motion of the two vehicles is accelerated, with the car taking the initiative in the push or collision. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the pushing force exerted by the car on the truck is equal to the backward pushing force exerted by the truck on the car. The student’s conception is correct insofar as it posits that the action-reaction force is not influenced by differences in mass, type of movement, or who takes the initiative to push or collide. Answer B indicates that students continue to hold the misconception that the same amount of action-reaction force is applicable only to interactions between objects of the same mass. In this case, students assume that if a car with a small mass collides with a truck with a large mass, the amount of force used by the car to push the truck is smaller than the backward thrust of the truck exerted on the car. This may be attributed to the student’s daily experience that a larger individual will have greater force than a smaller individual. Similarly, a larger rock will cause greater injury to the foot than a smaller rock. Being struck by a car is more traumatic than being struck by a bicycle. Such student misconceptions will be identified if students select answer B.

The objective of question C is to ascertain whether students still hold the misconception that the same amount of action–reaction force is applicable only to the interaction of objects moving at the same speed. The student’s mindset may be based on the assumption that if an object is accelerated, the resultant force must be non-zero. Consequently, students hypothesize that a larger force must exist between the two forces. This approach is referred to as “recursive plug-and-chug,” as it entails identifying the amount and entering it into the equation (Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). The students indicated that in the tug-of-war event, the victorious participant exerts a greater pulling force, with evidence that the opponent is pulled in the direction desired by the student. In the push event, the car assumes the role of the initiator of the force, leading the student to perceive that the sum of the car’s pushing force on the truck is greater than the truck’s backward pushing force on the car. Additionally, response C can be seen to encapsulate the students’ erroneous assumption that the party who assumes the initiative must exert a greater force. In this problem, the car initiates the force exerted on the truck. In their everyday experiences, students often perceive the force exerted on a stalled car to be greater than it actually is. This is because they are pushing the car, rather than the car pushing back against them. If A is pushed into the ravine by B, then B, who has the initiative to push, will exert a greater force, with evidence that A is bounced and pushed into the ravine. This is consistent with the mindset of reasoning primitives and intuitive mathematics, with physical mechanism game learning patterns (Tuminaro & Redish, 2007).

To ascertain whether students still hold the misconception that interaction does not necessitate an action-reaction force pair, it is essential to examine the circumstances surrounding the truck’s interaction with the car. In this case, the truck receives a push, yet there is no initiative to push back, resulting in the truck not exerting force on the car. The evidence indicates that if the truck does not exert force on the car, it is because the truck engine is not operational. Therefore, it is impossible for the truck to push the car. However, if the truck engine is started and placed in reverse gear, the truck will then exert a force on the car. According to the student’s reasoning, the car engine is running and therefore exerting a force on the truck, but the truck engine is not running and therefore unable to push the car back. The truck is only able to move forward due to its position blocking the car. In addition, students hold erroneous beliefs based on their everyday experiences, particularly during soccer games. When soccer player A casually dribbles the ball and is then pushed (in the body) by soccer player B, soccer player A bounces. The student’s erroneous assumption is that Player B exerts a force on Player A, yet Player A does not exert a force on Player B. This is evidenced by the fact that player B does not bounce, whereas player A bounces. Furthermore, player A has the initiative to lean his body in order to exert a force on player B. However, player A’s body remained upright, indicating that no force was exerted. Further, answer E aims to ascertain whether students still hold the misconception that there is no interaction force between the car and the truck, due to the accidental nature of the incident. The incident occurs as a result of a truck breaking down, which causes the car to push the truck due to its obstruction. Students’ understanding of Newton’s third law is that action and reaction occur when both objects are involved. Therefore, the misconception is that neither the car nor the truck exerts any force on the other. The truck is only pushed forward due to its position blocking the car.

3.1 Reduced Misconception on Newton’s First Law

There is a question:

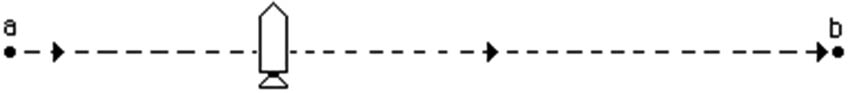

The figure depicts a hockey puck sliding with constant speed v

o in a straight line from point “a” to point “b” on a frictionless horizontal surface. Forces exerted by the air are negligible. You are looking down on the puck. When the puck reaches point “b,” it receives a swift horizontal kick in the direction of the heavy print arrow. Had the puck been at rest at point “b,” then the kick would have set the puck in horizontal motion with a speed v

k

in the direction of the kick.

Which of the paths below would the puck most closely follow after receiving the kick?

Table 3 indicates that 46 students initially selected a particular option, but only 24 students maintained the answer. Besides, 36 students who participated in both the pretest and posttest provided the correct answer B. Further, between these 36 students, 14 provided the correct reason for their answer, while 22 students provided an incorrect reason but still identified the correct answer. On average, 14 students provided the rationale that “after being kicked to the north, there is no further force acting, so the velocity vector is the sum of the speed to the east and the speed to the north.” Twenty-two students provided an incorrect rationale, stating that “the kicking force to the north causes the object to be accelerated to the north, so the resultant velocity is the combination of the speed to the east and the speed to the north.” To ascertain the students’ cognitive processes. The example of an interview excerpt is presented in the following.

| Researchers: | In yesterday’s exam, you answered number 8 correctly, B. You also wrote out the reason. Take another look at your reasoning. Now, give me a more detailed explanation of why your reasoning is like that. |

| Students: | Newton’s second Law says that force causes acceleration. So, when you kick the ball north, it’ll move north. That means it’ll also move east, so the answer is B. |

Distribution of students’ answers to question item 8 on pretest–posttest

| Posttest | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B* | C | D | E | X | B** | Total | |||

| 1.25% | 85.00% | 3.75% | 7.50% | 2.50% | 0.00% | 0.00% | ||||

| Pretest | A | 12.50% | 1 | 9 | 10 | |||||

| B* | 18.75% | 14 | 1 | 15 | ||||||

| C | 11.25% | 7 | 2 | 9 | ||||||

| D | 16.25% | 8 | 5 | 13 | ||||||

| E | 13.75% | 8 | 1 | 2 | 11 | |||||

| X | 0.00% | 0 | ||||||||

| B** | 27.50% | 22 | 22 | |||||||

| Total | 1 | 68 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 80 | ||

*Correct answer.

X students who give no answers.

**Students correct answers with wrong reason or without reason.

The results of the interview indicate that the students lack an accurate understanding of the graph representing the combination of fixed and accelerated speed. Consequently, they will not select answer option B but rather choose answer option D. Besides, they attempt to reason using intuitive mathematical principles and the Pictorial Analysis Game pattern (Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). Therefore, the students were incorrect in their responses to question number 8.

As illustrated in Table 3, one student initially selected the incorrect answer option A. The rationale provided for this choice was that “the kick neutralizes everything, so the ball goes north.” To gain further insight into this student’s thought process, an interview was conducted, the results of which are presented below.

| Researchers: | In yesterday’s exam, you selected answer option A in the pretest for question number 8. You also wrote that the kick neutralizes everything, so the ball goes north. Take another look at your reasoning. Now, go into more detail with me about why you think this way. |

| Students: | Well, sir, from my experience playing volleyball, when I hit the ball, it goes where I want it to, even if I hit it from any direction. When I hit the ball from behind, from the side, from the front, or anywhere, it goes where I want. |

| Researchers: | During the post-test, you still picked answer A, even though you’ve learned MI. |

| Students: | During the experiment, the object moving east was only pushed momentarily to the north. This isn’t the same as what’s in the question, which is that the bat sticks to the ball for a while. I think it’s when it sticks that it centralizes the movement to the east. So I’m not sure about how similar the case is between the experiment in the lesson and the case in the problem. |

The results of the interview indicate that students utilize reasoning primitives. The cognitive model (resource model) is employed in conjunction with the physical mechanism game mindset. Students employ primitive reasoning, an abstraction of everyday experience, to solve problems. Their daily experiences are interpreted by students into their brain structure, which is referred to as naïve knowledge (Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). It is evident that students bring naïve prior knowledge into the physics classroom (Bigozzi, Tarchi, Fiorentini, Falsini, & Stefanelli, 2018; Vermeulen & Meyer, 2017).

The MI learning with a virtual Phet laboratory designed by students has been found to be unable to replace the case in the problem, thus failing to address the problems (Mufit, Festiyed, Fauzan, & Lufri, 2018). The learning in the virtual Phet laboratory is regarded as analogous to their typical daily experience when playing volleyball. Despite efforts to demonstrate the applicability of the material to their own experiences, students remain unable to reconcile their preconceptions with the presented information. Consequently, the cognitive conflict process is not initiated, and students tend to persist in their existing misconceptions (Vosniadou, 2019).

Table 3 indicates that two students initially selected answer C, which was identified as the incorrect response. The rationale provided for this choice is the assertion that the effect of the kick will dissipate, causing the object to revert to its initial state of motion eastward. To gain further insight into the students’ thought processes, interviews were conducted with the two students, the results of which are presented below.

| Researchers: | In number 8 of yesterday’s exam, where you picked answer option C. You also wrote that the effect of the kick will run out so that it returns to its initial state of moving east. Take another look at your reasoning. Now, give me a more detailed explanation of why you came to that conclusion. |

| Student 2: | Well, when I was working on question number 8, I thought about my younger brother playing with toy cars. I turned on the car and it moved east to enter the hole. But because I hadn’t set the direction right, I pushed the car to the north. It moved north for a while, then went east again after the push wore off. |

| Student 1: | It was pretty similar, but in my case, I was riding the car bomb. When I was hit from the side, my car moved to the side, but then it moved back to the original direction after the pushing force wore off. |

Following the interview data, it can be inferred that students utilize their daily experiences to respond to question number 8. Students employ their initial, uninformed understanding of a subject matter (which, over time, may lead to the formation of erroneous beliefs) to assess a given problem. The two students interviewed asserted that “the effect of the pushing force runs out,” representing the impetus concept. The concept of impetus, as postulated by Drake (1975), states that in order to move an object continuously, a continuous force must be applied. If the force is applied for a moment, then the effect of the force will gradually diminish. In the concept of impetus, force is interpreted as energy (Jung, 2020; Robertson & Taczak, 2023). Therefore, it is evident that the two students brought misconceptions based on their previous daily experiences to solve the problem.

The results of interviews conducted after the posttest suggest that students still selected option C because they believed that MI learning using Phet was unable to replace the case in the problem. They also expressed skepticism about the results of experiments conducted in their groups, citing engineering toward the correct answer, namely B (Mufit et al., 2018; Vosniadou, 2019).

As illustrated in Table 3, five students initially selected the incorrect answer, option D. The rationale provided for this choice was that “the force will cause acceleration, so the result between the initial velocity and the speed to the north, if drawn, is D.” To gain further insight into the student’s thought process, interviews were conducted with the five students who had selected option D. The results of these interviews are presented in the following.

| Researchers: | OK, in yesterday’s exam, you picked answer D for question 8. You also wrote the reason that “the force will cause acceleration, so the resultant between the initial velocity and the velocity towards the north, if drawn, is D.” Take another look at your reasoning. Now, give me a more detailed explanation of why you came to that conclusion. |

| Student 3: | Well, sir, when I was working on question number 8, I remembered the lesson on parabolic motion. Parabolic motion is a combination of linear motion and perpendicular motion, then the graph is curved like answer D. |

| Student 1: | It’s similar, but in my case, when the marbles were rolled on the table and then fell, the path was like answer D. When I think about it, it was a combination of linear motion in the horizontal direction with the force of gravity. |

| Student 5: | I experienced it myself when I was bathing in the river, sir. My friend and I ran from a height and then plunged into the river. When I saw the trajectory of my friend’s plunge, it looked like answer D, sir. |

| Student 2: | I have the same reason as student 3, sir. |

| Student 4: | I have a similar experience to Student 1, but the event occurred during my high school practicum, sir. |

The interview data indicate that the five students also drew upon their daily experiences to respond to question number 8. The students employ the pictorial analysis game mindset to analyze the problem. The results of the interview indicate that the students’ epistemic game, as evidenced by their responses to question 8, is pictorial analysis (Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari, Wahyuniar, & Wardani, 2020; Puspitasari, 2023). Therefore, it is evident that the eight students employed misconceptions based on their previous daily experiences in order to solve pictorial-based problems. During the posttest, students continued to select option D, as they had during the experiment in MI learning because they had found that the trajectory was consistent with this answer. However, an error in the experimental procedure meant that the upward movement was accelerated due to the continuous application of force. This demonstrates that, if not managed properly, experiment-based learning can reinforce students’ misconceptions (Oma, 2021).

Table 3 indicates that two students initially selected answer E, which is incorrect. The rationale provided for this choice is that “the kicking force is only for a moment, so gradually the speed to the north also drops. When combined with the initial velocity, the matching graph is E.” To gain further insight into the student’s thought process, interviews were conducted with the two students in question. The results of these interviews are presented below.

| Researcher: | In yesterday’s exam, in question 8, you picked answer E. You also wrote a reason, saying that the kicking force is only momentary, so the speed to the north gradually drops. When you put the initial velocity into the equation, the graph matches option E. Take another look at your reasoning. Now, give me a more detailed explanation of why you came to that conclusion. |

| Student 2: | When I was working on problem number 8, I thought back to my daily experience of kicking a ball, sir. No matter how hard I kicked the ball, it eventually came to rest. So the motion is straight and slowed down regularly. |

| Researcher: | So, what is your conclusion? |

| Student 2: | I tried to draw the x-axis of linear motion and the y-axis of straight motion slowed down by regularity. I think the most suitable answer is E, sir. |

| Student 1: | I agree, sir. I’m a soccer player, sir. |

As evidenced by the interview, both students drew upon their daily experiences to respond to question number 8. The results of the interview indicate that the students’ epistemic game, as evidenced by their responses to question 8, is the physical mechanism game (Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari et al., 2020; Puspitasari, 2023). In the physical mechanism game, students attempt to construct a physically coherent and descriptive story based on their intuitive sense of physical mechanisms. The knowledge base for this game consists of reasoning primitives (Chen, Irving, & Sayre, 2013; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). The students’ assumption that the absence of force equates to the absence of energy results in their prediction that the ball will gradually lose energy and then come to a standstill (Jung, 2020). In the posttest, the students maintained their original answer (E), citing the discrepancy between the experiment and reality as the reason. The air track, employed to eliminate friction during movement, represents an engineering solution that does not align with reality (Kelly, 2010).

Table 3 indicates that nine students altered their response from option A to the correct answer, B, providing a rationale for this change. Initially, the students’ responses were based on their daily experience of kicking a ball, which they asserted would travel in the direction of the kick regardless of the ball’s initial trajectory. Other students’ responses initially aligned with this perspective, citing examples such as hitting a baseball, striking a cock during badminton, or pushing their friends. To substantiate the rationale behind the shift toward the correct answer B, interviews were conducted with the nine students, while the interview excerpt is presented in the following section.

| Researcher: | OK, in yesterday’s pretest, you picked answer option A for number 8. You also wrote that the reason is “the kicking force neutralizes the initial motion of the object.” Let’s take another look at your reasoning. Now, can you go into more detail with me about why you came to that conclusion? |

| Student 1: | When I was working on question number 8, I remembered what it was like when I kicked the ball. If the ball was rolling east and I kicked it north, it would go north. No matter where the ball was originally heading, if I kick it north, it will definitely go north. Given my experience, I initially went with answer A. |

| Researcher: | Right, what about the others? |

| Student 3: | It’s pretty similar, but in my case it’s badminton. It doesn’t matter where the ball comes from. If I want to hit it in a certain direction, it will go there. |

| Student 5: | I agree. I’ve had the same experience playing baseball. |

| Student 4: | When I pushed my friend. |

| Student 2, 6, and 7 | I agree with Student 1. |

| Student 8 and 9: | I agree with Student 4. |

| Researcher: | Then, when you took the post-test, you switched to option B, which was the correct answer. What happened? |

| Student 2: | I had a different learning experience, sir. I think I was taken to my everyday life first. I was shown the event that led me to choose A earlier, sir. The learning process is always guided by the students’ worksheets and the lecturer, who provides direction during discussions. At a certain point, I was asked to create experimental designs, both real and through virtual Phet labs, which challenged my initial ideas. After that, we had a discussion about how my daily experience occurs because there are so many uncontrollable variables. We also looked at the results of the real and Phet experiments. We discussed this and realized that if you control these variables, you get a combination of the initial speed to the east and the speed of the kick to the north. This is answer B. |

| Researcher: | You said earlier that you were guided by the student worksheet and the lecturer during the discussion. If you’ve done this kind of learning often, do you still need direction? |

| Student 4: | I think, we can gradually take less direction over time. I’ve learned the pattern well enough that I don’t need as much guidance. |

| Researcher: | That direction is called scaffolding. I thought all lectures had some kind of direction. |

| Student 5: | I’m not sure, sir. From my experience, I tend to see the direction as an afterthought, so there’s no discernible pattern. |

| Student 6: | Absolutely, sir. I have the same reason as Student 5. The direction wasn’t planned from the start. In this case, the student worksheet is clear, and the lecturer always provides direction in the form of comments that consistently focus on the learning objectives. Also, I think this learning is fun because the problem is based on things I deal with in my day-to-day, so I’m challenged to follow the learning. |

| Student 7: | Anyway, I feel like my understanding is challenged. |

| Student 8: | In the final stage of learning, we were given a problem similar to the aforementioned problem, so that we built our new conception more firmly. |

| Other students: | Yes, sir, like that. |

| Researcher: | OK, thank you. You’ve answered honestly. |

The interview data suggest that the directions provided by the lecturer, both in written form (worksheet) and orally, serve as a form of scaffolding. A defining feature of scaffolding is the provision of assistance, albeit not indefinitely. With sufficient guidance, students can effectively master the scaffolding pattern (Belland, 2017). The utility of scaffolding is contingent upon its initial design, ensuring that students are equipped with the requisite tools to navigate the learning process with optimal focus (Doo, Bonk, & Heo, 2020; Ertugruloglu, Mearns, & Admiraal, 2023). From the interview, it can be inferred that learning will be highly engaging if the problems presented are authentic and drawn from students’ daily lives (Raine, 2019). If the learning provides solutions or benefits for students’ real lives, then the learning will be perceived as highly interesting (Lee, 2020). Experiments, both real and virtual (Phet), are designed to challenge students’ naive conceptions or misconceptions. Experiments are designed to be similar to students’ daily experiences and then practiced if the uncontrollable variables are controlled. In virtual experiments, it is more straightforward to regulate the variables that influence the outcomes. In the initial stages of utilizing Phet, it is demonstrated that the outcomes were identical to those experienced by students in their everyday lives, provided that the variables are not subjected to control. Once the variables have been controlled, the result is answer B. This stage is crucial, as it allows students to gradually shift their misconceptions toward a more accurate understanding. If students are presented with problems that reflect their daily experiences and are encouraged to develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter, they will be better equipped to analyze these problems effectively (Haryono, Aini, Samsudin, & Siahaan, 2021; Mufit, Festiyed, Fauzan, & Lufri, 2023; Suhandi et al., 2020).

As evidenced in Table 3, seven individuals initially selected the incorrect answer option C but ultimately selected the correct answer option B. The typical student’s understanding is that the transient force exerts a mere shift in direction. Once the force’s effect dissipates, the object will resume its original trajectory. The student’s initial responses were informed by their daily experience of shifting the Tamia toy car. Once the effect of the push had run its course, the Tamia would resume its original trajectory. Other students’ original responses were also shaped by similar experiences, including the shifting of a rolling ball, the slipping of a box to avoid hitting a car, and the “bodying” of a friend during a chase. To ascertain whether these responses could be redirected toward the correct answer B, interviews were conducted with the seven students. The excerpt of the interview is also presented in the following section.

| Researcher: | OK, in yesterday’s pretest, you picked answer option C for number 8. You’ve also written the reason “the momentary push only has the effect of shifting the direction.” It seems like you understand that after the push is over, the object will move in the original direction. Let’s take another look at your reasoning. Now, can you go into more detail with me about why you think that way? |

| Student 2: | When I was working on question number 8, I remembered pushing my Tamia toy car to change its direction. If I push my Tamia toy car from east to north, it moves north a little, then it goes east again. So, I just shifted it, sir. The Tamia is originally moving east, so I push it north, and it shifts north a little bit and then moves east again. Based on my experience, I initially selected answer option C. |

| Student 3: | It is similar, but in my case, it is when the ball is rolling. At the time, my younger brother kicked the ball in the direction of a small goal. I saw that he missed, so I pushed the ball with my foot to help it reach the goal. |

| Student 5: | Same here, sir. If I remember correctly, when the road is downhill and there’s a box that slips, it’ll probably hit a parked car. To avoid hitting the car, I give it a little push from the side. So, the box shifts a little and then moves again, but it is not heading toward the parked car anymore. |

| Student 4: | I enjoy playing soccer, though I’m not particularly skilled at it. At the time, my friend and I were competing for the ball. To prevent my friend from getting it, I pushed him with my body. The phrase “body” in the context refers to the ball. My friend changed his direction of movement, which gave me control of the ball. |

| Student 1: | Basically, I have the same reason as Student 2, except that it is my 3-year-old brother’s toy car. |

| Student 6 and 7: | I’m in a similar position to Student 4 |

| Researcher: | So, when you did the post-test, you switched to option B. What happened there? |

| Student 2: | After learning more about this, I realized that there were still many uncontrollable factors. The learning was supported by a well-directed student worksheet, sir. I also found the lecturer’s guidance during the discussion really helpful in focusing on the issue. From the start, I was guided through everything, from everyday events to group discussions, designing experiments, presentations, and reinforcement. The lecturer was always there to help. |

| Student 1: | When we were designing and conducting experiments, we saw that the problem was similar to my everyday experience. Then, we saw that when we controlled the variables, the movement was similar to answer B. We even did a virtual experiment showing that if we controlled all the relevant variables, the movement of the object was exactly similar to answer B. If you controlled the relevant variables, the movement of the object would be exactly like answer B. |

| Student 3: | The virtual experiment also showed that if you don’t control the variables, you end up moving a little and then moving again to the original direction. But after you control and adjust the variables to match question number eight, the movement is like answer B. |

| Student 4: | I’m glad we got to see the real movement of objects first, even though the variables weren’t controlled. Then I saw how we adjusted the conditions to answer question number 8. It seemed like we were gradually shifting our thinking in the right direction. It was like we were given facts to back up our understanding, not just theory. |

| Student 5: | I like how the learning is connected to our everyday problems, sir. |

| Student 6: | We also saw firsthand what happened when you adjusted the conditions to problem number 8. |

| Student 7: | It seems like we have the confidence to implement this learning for our other daily problems. |

| Researcher: | You mentioned earlier that you were guided by the worksheet and the lecturer during the discussion. If you’ve done this kind of learning often, do you still need guidance? |

| Student 7: | I think, the guidance can gradually reduce. Eventually, you will not need guidance because you will have mastered the pattern. |

| Researcher: | That guidance is called scaffolding. But, isn’t every lesson also guided by the lecturer? |

| Student 5: | It seems like direction is only given when there’s a problem and is kind of an afterthought. |

| Student 6: | I agree with that, sir. It seems like we are only given direction when we need it. It is exactly what it should be. The worksheet is basically the same as the worksheet from high school. There is no direction at all. What is also important is that this learning can really help me with my daily problems. That is useful. |

| Student 7: | I felt enlightened. |

| Student 1: | I had to say, “Oh, it turns out so.”. |

| Other students: | Yes, sir. My comment is similar to my friends’. |

Student 7’s response indicates that this form of assistance can be classified as scaffolding. Scaffolding is designed to provide temporary assistance to students, after which they are expected to master the material independently (Belland, 2017). Effective scaffolding is a deliberate process that guides students from simple thinking patterns to critical thinking patterns (Jarvis & Baloyi, 2020). Additionally, interviews with students have revealed that learning that challenges their misconceptions can be beneficial. Contextualized learning is defined as learning based on students’ daily problems, as opposed to problems engineered by the curriculum (Nyabando & Evanshen, 2021; Riordan et al., 2023). When learning is contextualized and relevant to students’ real-life experiences, it is perceived as more interesting and useful (Lee, 2020). Based on the interview data, students also indicated that they are guided toward the correct answer option B. In addition to daily problems presented in class, the students can visualize them through the implementation of real experiments. The students designed the experiments themselves to demonstrate the events that occur in their daily lives. Furthermore, real experiments are employed to demonstrate the characteristics of the movement if the actual experimental setup is to be subjected to the conditions outlined in question number eight. It is revealed that the movement of objects is analogous to answer option B. Despite the utilization of virtual experiments with Phet, the experimental set is conditioned in a manner analogous to the circumstances of everyday life, resulting in analogous outcomes to answer C. This approach is crucial for fostering students’ confidence in the virtual experimental set. When the experimental set is conditioned in accordance with the parameters set forth in question number 8, the students testify that the motion of the object is identical to that described in answer option B. This stage, based on the findings of the interview, is capable of facilitating a shift in the student’s understanding from a state of misconception to one of accurate conceptualization. If the learning process presents or visualizes the events occurring in students’ daily lives and subsequently establishes the correct conception, it will become firmly established in their mindsets (Ha & Kim, 2020; Haryono et al., 2021; Suhandi et al., 2020).

Table 3 shows that 68 students provided the correct response during the posttest. Fourteen students (17.5%) provide correct responses from the outset, while 54 students (67.5%) exhibit a shift from initial misconceptions to more accurate conceptualizations. One student initially provides a correct response but then alters it to an incorrect one. Additionally, 12 students (15.00%) initially provided incorrect responses and subsequently maintained those responses despite continued learning. Eleven students maintain their incorrect responses, while one student changes his answer but remains incorrect. The 54 students, on average, indicated that the reason for changing to the correct answer was that the learning process was effectively guided in a way that made it straightforward to direct students toward the correct conceptual understanding. Additionally, students are provided with opportunities to challenge their existing ideas through tasks and experiments grounded in their daily experiences and reinforced through the use of both real and virtual laboratories (Fadhilah, Effendi, & Ridwan, 2021; Haryono et al., 2021).

The guidance provided to students represents an example of scaffolding (Belland, Weiss, Kim, Piland, & Gu, 2019; Belcher, 2017). In the initial discussion, which involves observing the phenomenon, students are guided by student worksheets online that include written scaffolding of procedural and conceptual types. At the initial stage of the discussion, the individual acting as a guide has been prepared to assist students in observing the phenomenon in a way that is conducive to achieving the desired outcome. A total of 12 students persisted in their misconceptions because they considered experiments conducted in virtual laboratories, such as Phet, to be unreal and engineered (Aşıksoy & Islek, 2017).

Figure 2 presents a comparison of the percentage of students whose misconceptions are reduced with the percentage of students whose misconceptions persist for Newton’s law I material for question number 8.

A comparison of the percentage of students whose misconceptions are reduced with the percentage of students who retain their misconceptions for Newton’s law material, question number 8.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the percentage of students who reduced their misconceptions with the percentage of students who persisted in their misconceptions of Newton’s law I material across all questions.

A comparison of the percentage of students whose misconceptions are reduced with the percentage of students who retain their misconceptions for Newton’s law I material is presented herewith.

3.2 Decrease of Conceptual Error Concerning Misconception on Newton’s Second Law

There is question

A rocket drifts sideways in outer space from point “a” to point “b” as shown below. The rocket is subject to no outside forces. Starting at position “b,” the rocket’s engine is turned on and produces a constant thrust (force on the rocket) at right angles to the line “ab.” The constant thrust is maintained until the rocket reaches a point “c” in space.

21. Which path below best represents the path of the rocket between points “b” and “c”?

Table 4 indicates that 43 students maintained their initial choice, whereas only 33 students maintained their initial mindset. A total of 18 students, who participated in both the pretest and posttest, had retained the correct answer, designated as E. Of these 18 students, 8 provided the correct rationale for their responses, while 6 students did not provide a reason, and four provided an incorrect reason. On average, 8 students provided the rationale that “after the rocket engine starts, the upward thrust causes acceleration, so the result is the resultant between the sideways fixed speed and the upward fixed acceleration.” Four students who provided the incorrect rationale asserted that the thrust of the rocket causes a fixed speed that is higher than the sideways speed, resulting in the sideways speed being gradually dominated by the upward speed. To confirm the students’ understanding, interviews were conducted with four students.

Distribution of students’ answers to question 21 during pretest-posttest

| Posttest | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E* | X | E** | TOTAL | |||

| 7.50% | 7.50% | 11.25% | 12.50% | 61.25% | 0.00% | 0.00% | ||||

| Pretest | A | 21.25% | 6 | 1 | 10 | 17 | ||||

| B | 16.25% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 13 | ||||

| C | 20.00% | 7 | 9 | 16 | ||||||

| D | 16.25% | 1 | 8 | 4 | 13 | |||||

| E* | 12.50% | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 | |||||

| X | 1.25% | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| E** | 12.50% | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| Total | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 80 | ||

The results of the interview indicate that, when students seek to enhance the stable speed, they apply their daily experience by accelerating the motor until it reaches a point of stability at a specific RPM. Consequently, the lateral velocity will decelerate when the ball is rolled. The cognitive model utilized by students is the physical mechanism game. Students employ a form of reasoning that is based on everyday experience and can be described as a primitive abstraction. This enables them to solve problems. Meanwhile, students themselves interpret their daily experience into their brain structure, thereby creating their own naïve knowledge (Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). It can be concluded that the four students were incorrect in their responses to question 21.

Based on Table 4, six students initially selected the incorrect answer choice A. The rationale provided for this choice was “the upward thrust will gradually slow down.” To gain further insight into the student’s thought process, interviews were conducted with six students. The interview results indicate that most students lack an understanding of the context of the problem in space, which leads them to believe that there is no other force at work besides the upward thrust of the rocket engine. The phenomenon of the rocket’s upward movement is still perceived as a reduction in speed, due to the continued influence of the students’ daily experiences. They continue to apply their daily experience on Earth to this situation. Therefore, students hypothesize that the rocket will initially ascend, but subsequently return to a lateral trajectory. Accordingly, the students’ epistemological approach to solving the problem is the physical mechanism game (Chen et al., 2013; Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari et al., 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). Students attempt to employ the problem-solving strategy of mapping mathematics to meaning, specifically recalling the equation W = mg and then interpreting that the object will be decelerated by ascending (Rodriguez, Bain, & Towns, 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007).

As evidenced in Table 4, four students initially selected answer B, which was identified as the incorrect response. The rationale provided for this choice was based on the premise that “the engine thrust dominates the movement, so there is only upward movement at a fixed speed.” To gain further insight into the student’s thought process, interviews were conducted with these four students. During the interview, students described that they employ their daily experiences, such as kicking a ball, setting off firecrackers, and changing direction when the beam slips, when solving problems. The physical mechanism game problem-solving strategy is employed by students (Hunter, Rodriguez, & Becker, 2021; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). Additionally, students posit that a residual gravitational force acts to counteract the rocket’s thrust, resulting in a net linear motion force that counteracts the rocket’s lateral motion. Students construct a free-body diagram of the rocket, wherein they identify a downward force of gravity and an upward force of rocket thrust of equal magnitude. In addressing the problem, students employ the pictorial analysis problem-solving strategy (Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari et al., 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007).

As evidenced in Table 4, seven students initially selected answer C, which was identified as the incorrect response. The rationale provided for this choice was based on the premise that “the thrust force of the machine causes a constant upward speed, so the resultant between the constant upward speed and the constant sideways speed is C.” To substantiate the hypothesis that the students were operating under a certain mindset, interviews were conducted with the seven students in question.

The interviews with these seven students indicate that they drew a parallel between this phenomenon and their everyday experience of attempting to accelerate their motorcycle. The assumption is that increasing the angle of the handlebar will result in a greater force being exerted by the motorcycle engine. In their experience, the motorcycle will travel at a fixed speed that is higher than that at which it was previously traveling. The student’s understanding of the relationship between force and speed remains that force is proportional to speed. In their everyday lives, students tend to grasp the concept of speed or velocity with greater ease than that of acceleration. A journey of 100 km is completed in 2 h at a speed of 50 km/h. The students’ epistemic game for solving the problems is a physical mechanism game, as described by Chen et al. (2013); Odden & Russ (2018); Puspitasari et al. (2020); Puspitasari (2023); Tuminaro & Redish (2007) was the method used to solve the problem. Three students are depicted in free-body diagrams, representing the forces acting on a rocket. The downward force of gravity and the upward force of rocket thrust are of equal magnitude. The students employed the pictorial analysis problem-solving strategy to address the problem (Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari et al., 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007).

Table 4 also shows that eight students persisted in selecting the incorrect response, option D. The rationale provided for this choice, on average, was that the initial push was weak and then gradually enlarged. To substantiate the hypothesis that the students’ responses were indicative of a specific cognitive process, interviews were conducted with the eight students who had selected answer D. From the interview students’ described that, as a rocket is a large object, they drew upon their experience of pushing a heavy object to inform their responses. In the initial stages of pushing a heavy object, such as a car, the object appears to be relatively stationary. However, after a brief interval, the car begins to move. The students’ epistemological approach to problem-solving is the physical mechanism game (Chen et al., 2013; Odden & Russ, 2018; Puspitasari et al., 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). The students apply the concept of Newton’s first law, which states that the greater the mass, the greater the inertia. Therefore, it requires a considerable amount of time to overcome the inertia of an object with a large mass. During this period, students employ the strategy of mapping mathematics to meaning (Rodriguez et al., 2020; Tuminaro & Redish, 2007). Consequently, initially, the dominant movement is still the sideways movement of the rocket, followed by the emergence of only the upward acceleration.

As presented in Table 4, the remaining ten students changed their response from A to E. Initially, they based their answer on their daily experience of throwing objects upward, noting that the speed decreases with increasing height. To confirm the reason for this change, interviews were conducted with these students.