Abstract

The low level of nationality awareness among primary school students, which resulted from inadequate learning, served as the research basis. A learning model was developed to facilitate this, namely the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model. However, the previous learning model was not contextual, did not involve students, did not consider the students’ preferred learning methods, and did not connect the technology-based learning process. Although the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach has been deemed valid, further research was required to ascertain its impact on students’ nationalistic insight. This research aimed to determine how elementary students’ nationalistic insight was impacted by an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model. Six hundred students participated in this quasi-experimental research. Test questions were utilized to assess their level of nationalistic insight. The normality, homogeneity, paired sample t-test, effect size, and independent sample t-tests were performed on the test results. The findings indicated that the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model impacted elementary school students’ nationalistic insight. Comparing students who learned conventionally with those who used the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model, the former showed a higher value of nationalistic insight. The findings of this study have value for how academics might help elementary school students develop their nationalistic insight.

1 Introduction

Nationalism is a thorough grasp of national ideals, citizens’ rights and obligations, and how citizens love their nation and country (Bideau & Kilani, 2012; Kumar & Jan, 2013). Nationalistic understanding is not only information but also a component of citizens’ efforts to strengthen a sense of togetherness amidst diversity. Nationalistic insight is required in society’s diversity, such as ethnic, socioeconomic, cultural, and religious differences, which can be used to foster mutual respect and establish a harmonious living (Junaeda, Kesuma, Sumilih, Dahlan, & Bahri, 2022; Mukri & Waspiah, 2023). In the age of globalization, outside cultures significantly impact people’s lives, particularly the younger generation. The era of globalization enables the younger generation to have widespread and open access to knowledge, which influences their life processes. If a thorough grasp of national identity does not balance this impact, it will lead to weak national connections. Nationalistic insight serves to safeguard individuals against the impact of outside cultures that do not align with local values. Nationalistic insight enables individuals to filter these influences and adapt to prevalent beliefs and norms while keeping their national identity.

Individuals with a national understanding can deter national disintegration (Isabella, 2017). Ethnic and social diversity, which is part of the nation’s wealth, can cause conflict if not managed properly (Sukma, 2021). Individuals with a nationalistic perspective can benefit from seeing diversity as a shared strength to achieve common goals. This process is critical to ensuring the country’s stability and integrity. As a result, nationalistic understanding must be imparted to the population at a young age, beginning with elementary school.

Nationalistic awareness should be formed in elementary school because this is the first stage in developing a child’s character and basic values (Zulela, Neolaka, Iasha, & Setiawan, 2022; Zulfikar, Permady, & Sudirman, 2023). Elementary school-aged children are in a vital stage of cognitive and emotional development. Children in this era can understand social values and moral concepts, as well as establish their own identities. The process of instilling nationalistic awareness in elementary school students will help them comprehend and respect the idea of unity in diversity, as well as the value of patriotism (Cahyani & Isah, 2016; Izzati & Adiarti, 2020). Developing patriotic insights in primary school will create a young generation that will value diversity in religion, ethnicity, and culture. Students with a high level of nationalistic insight will find it simpler to acquire empathy, tolerance, and the ability to cooperate with others without questioning their nationality. This concept is crucial in today’s multicultural life.

Furthermore, nationalistic awareness is crucial for elementary school pupils to acquire as at that age children often get fast impacted by the information, they encounter both from the media and peers (Mubarok & Anggraini, 2021). By giving national insight, students are not only taught the importance of national values but also taught how to apply these principles in their daily lives. Students will grow up with strong national ideals toward their country. This process will produce individuals with a strong social duty to protect national unity. As a result, it is critical to ensure that elementary school pupils get the best possible nationalistic insights.

However, according to the literature review, elementary school kids have low nationalistic awareness (Fitri & Habiby, 2023; Hendrowibowo, Harsoyo, & Sunarso, 2020; Saputro, Winarni, & Indriayu, 2020; Wahyani, Ma’ruf, Rahmawati, Prastiwi, & Rahmawati, 2022; Widiana, Tegeh, & Artanayasa, 2021; Wulandari & Senen, 2018). Elementary school kids’ limited nationalistic insight is shown in their lack of comprehension of student nationalism (Saputra, Murdiono, & Tohani, 2023). Many pupils lack an extensive knowledge of national symbols and the concept of nationalism; therefore, they have no emotional connection to these values. Furthermore, elementary school pupils with little nationalistic understanding are more likely to grasp foreign cultural values than their national values. Students become more familiar with foreign cultures through digital entertainment/technology, while their own culture is undervalued (Djumadiono, 2019; Sari & Dahnial, 2021).

This is supported by observations made by researchers at five state primary schools in Indonesia. Based on these observations, many pupils lack a love for their nation and a knowledge of state symbols. This observation is evidenced by the fact that many pupils are unenthusiastic about performing the flag ceremony, which is a mandatory program every Monday to commemorate the services of the nation’s fighters. Even when asked about the meaning of the state symbol and the colors of the flag, many students misinterpreted them. Observations revealed that many students were unfamiliar with the country’s history. Many students struggled to identify heroes and significant events in the country’s independence process. Furthermore, many students are not enthusiastic about commemorating Independence Day. This finding indicates that primary school pupils lack nationalistic awareness.

To obtain accurate data, the researcher conducted an initial measurement of elementary school children’s nationalistic insight with 600 fifth-grade students. The results of the initial measurement are as follows:

Table 1 shows that the initial measurement results for each aspect of national insight are in the low category. This lack of patriotic awareness must be addressed promptly so that elementary school pupils can become individuals who are accountable to the nation and state.

Initial measurement results

| Aspect | Scores | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of nationality | 46.03 | Low |

| Understanding of nationality | 45.50 | Low |

| Spirit of nationality | 45.00 | Low |

| Average | 45.51 | Low |

According to the researcher’s findings, primary school pupils’ lack of nationalistic awareness is due to a poor learning process established in schools. The existing learning procedure remains same and does not consider pupils’ ethnic backgrounds or requirements. This procedure leads to a lack of connection with nationalist learning. The learning process also does not fully integrate local culture, so pupils do not comprehend the meaning of diversity and the need of tolerance in differences. Furthermore, the existing learning process remains conventional without the use of technology, making the learning process dull because it is out of date. The learning process remains in the form of lectures and memorization without student participation, causing pupils to become uninterested and bored shortly afterward. This technique makes learning about nationality monotonous. Furthermore, the learning process is not inclusive, and teachers are not allowed to modify the learning model, resulting in students having a limited area for recognizing cultural differences that form national identity. This method also leads to kids preferring to work independently rather than collaboratively. Current learning does not enable students to participate in project activities that directly investigate national values. This learning situation shows the necessity for learning adjustments that can help with these issues to build primary school kids’ patriotic insights.

Based on this situation, earlier studies created an ethnological-based differentiated digital learning model. The ethnological-based digital learning approach incorporates components of digital technology, customized learning, and local cultural values. This learning paradigm is intended to make learning more engaging by incorporating interactive technologies. This strategy helps primary school pupils learn nationality in a fun way by promoting diversity and allowing instructors to tailor instruction. This model also includes project tasks that encourage students to absorb national values, making it appropriate for use in efforts to enhance elementary school students’ national understanding. Three learning design specialists have pronounced this ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning paradigm valid and practical for use.

However, earlier study was limited to assessing the model’s feasibility. As a result, more study is needed to establish the impact of an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach on elementary school kids’ nationalistic insight.

This research has never been undertaken. Previous studies have begun to investigate the development of nationalistic insight. Priyambodo, Sukartiningsih, and Hum (2021) investigated the process of creating an effective interactive digital map media to increase critical thinking abilities connected to the nature of nationalism in elementary school children. Puspasari, Abidin, Rusdiyani, and Afifah (2020) investigated the construction of an ethnomathematics-based problem-based learning learning paradigm that effectively increases students’ sense of nationalism. Usman et al. (2020) investigated the construction of effective multicultural education teaching materials to improve the nationalism of future elementary school teachers. These studies demonstrate that this research differs from earlier studies.

This study focuses on the use of an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model that combines digital methods with diverse and ethnosocial-based approaches, specifically for elementary school students, and directly measures the effect of this model on elementary school students’ nationalistic insight. Thus, this study aims to investigate the impact of the Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model on primary school students’ nationalistic insight.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model

The ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model was developed to combine differentiated learning components with local cultural contexts in digital learning environments. This approach highlights the need to recognize students’ diverse cultural backgrounds, learning styles, and skills and how technology can help them learn in a relevant and adaptive manner.

The model serves as a theoretical foundation, incorporating the notions of Social Constructivism (Vygotsky), which emphasizes that learning depends on social and cultural interactions, and Distributed Learning Theory (Tomlinson), which emphasizes that learning should be adapted to students’ specific requirements. Furthermore, this method promotes self-reliance theory (SDT) to increase students’ intrinsic motivation and social-emotional learning (SEL) to develop their social–emotional capacities through an awareness of cultural variety.

2.1.1 Learning Theory

The ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model is based on Lev Vygotsky’s (1978) social constructivism theory and Tomlinson’s (2001) differentiated learning theory. Vygotsky emphasizes the importance of social interaction, culture, and scaffolding in learning through the zone of proximal development (ZPD). He used local cultural aspects like folklore and national emblems to create appropriate learning environments. Tomlinson, on the other hand, emphasizes the need to adapt learning to students’ needs, abilities, and learning styles (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic). The purpose is to respect diversity and give all students an equal opportunity to learn the material. This approach makes education more inclusive, engaging, and effective.

2.1.2 Motivation Theory

Deci and Ryan (2013) developed self-determination theory (SDT), which complements the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model by highlighting three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and connectedness. Student autonomy is achieved through participation in cultural projects, group discussions, and digital exploration. Competence is accomplished by setting challenges that are appropriate for students’ skills, and connectedness is strengthened by incorporating local cultural elements which increase their sense of pride and cultural identity. Previous research (Hernández-Martos et al. 2024; Smith & Langberg, 2018) demonstrates that cultural context-based learning can boost students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement, making SDT an excellent basis for learning sustainability.

2.1.3 Social-Emotional Development Theory

The SEL framework from CASEL (2013) forms the basis of the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model. SEL focuses on five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. The model promotes students’ social awareness through culturally relevant activities such as learning cultural symbols and folklore, which improve empathy, tolerance, and the ability to collaborate in varied groups. In addition, culture-based projects assist students in building interpersonal, communication, and conflict-resolution skills, resulting in a more inclusive learning environment. These activities also help students comprehend their identity as members of the Indonesian nation instill cultural pride, and create students’ overall character while increasing academic achievement (Taylor, Oberle, Durlak, & Weissberg, 2017).

2.1.4 Digital Learning Theory

The ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model is based on digital learning theory, which emphasizes the use of technology to enrich, customize, and make learning more relevant. According to the Connectivism theory (Siemens, 2005), learning comprises the interaction of students with technology, allowing students to learn at their own pace and style using tools such as interactive stories, simulations, and videos. Blended Learning (Bonk & Graham, 2012) mixes face-to-face and digital platforms to enable flexible and contextual investigation of local culture. Furthermore, the TPACK approach (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) highlights the convergence of technology, pedagogy, and content, allowing teachers to present culture-based materials while also increasing students’ digital literacy for 21st-century demands.

This learning paradigm combines learning theory, motivation, SEL, and digital learning to create an adaptive, relevant, and contextualized learning experience. The model’s components include syntax, social system, reaction principle, support system, and instructional and accompanying effects.

The syntax (Learning Stages) of this model consists of six main steps:

2.1.5 Introduction

The teacher introduces the learning theme and explains the learning objectives. The teacher will connect the learning content to the local culture that the pupils are familiar with. This approach can be aided by viewing videos relating to the content to be taught. (referring to the principle of social constructivism)

2.1.6 Initial Exploration

Students will be guided to communicate their initial knowledge of the topic they will learn. In addition, the teacher refers to the local cultural environment. During this initial exploration stage, the teacher uses digital technology such as videos or interactive simulations. Students are also requested to share their initial understandings. Teachers can utilize this technique to identify disparities in pupils’ levels of understanding and cultural experiences. Teachers can also use platforms like Padlet to help pupils convey their early understanding (Connectivism Principle and the TPACK Framework).

2.1.7 Learning Differentiation

At this stage, teachers apply the learning process based on students’ learning styles, backgrounds, and needs. The learning methods addressed include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic, all of which are common among elementary school students. Before implementing this methodology, teachers conduct a learning style identification process to better understand their students’ learning preferences. The identification procedure consists of direct observation of students’ behavior during learning activities, initial assessment via quizzes or short examinations, and the use of applicable learning style surveys, such as the VARK Questionnaire. At this point, the teacher creates resources tailored to the needs of the pupils, such as text modules, videos, and interactive media.

2.1.8 Material Enrichment

At this stage, students explore the learning subject through project activities and discussions. The teacher prepares students to analyze cultural values by relating academic subjects to their culture. Students can use videos to document their project progress (Supporting SDT).

2.1.9 Reflection and Application

At this stage, students are expected to reflect on their activities and consider how the subject might be applied in everyday life. The teacher urges pupils to be able to apply the information and knowledge they have received so that they can see how the learning has benefited them. The teacher instructs the students to write their reflections in a digital journal or video log, commonly known as vlog.

2.1.10 Authentic Assessment

The teacher evaluates students’ comprehension utilizing the digital project or portfolio technique about the ethnosocial values discussed. The examination focuses on student's capacity to connect academic concepts to the cultural and social variety around them.

2.1.11 Evaluation and Follow-Up

At this stage, the teacher is expected to assess the entire learning process. This procedure seeks to allow the teacher to take post-learning action, such as offering assistance or enrichment. This follow-up aims to ensure that students internalize their national values and local culture (SEL Framework).

Other components, such as the social system, are collaborative, allowing students to learn through interactions with their classmates. Meanwhile, according to Vygotsky’s ZPD theory, teachers serve as facilitators, offering scaffolding to assist students in understanding complicated concepts. The reaction principle highlights the need for responsive teachers who provide positive feedback to keep students motivated and assist them overcome learning challenges. The support system includes learning technologies, culturally appropriate resources, and teacher training. TPACK-based learning is supported by technologies such as digital devices and the internet. Meanwhile, culture-based materials, align with the idea of SDT, and allow students to become more connected to the local culture. One of the objectives of teacher training is to provide them with necessary pedagogical and technology skills. By mixing local cultural components into digital learning and developing critical thinking abilities, this education style attempts to increase students’ academic comprehension and widen their national horizons. Social-emotional education (SEL) principles assist students in developing social-emotional qualities such as empathy, tolerance, and cooperativeness. They are also taught to value differences, raise social awareness, and develop their national identity by researching local cultures and working in groups.

This ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model is utilized as a teaching tool to help students in elementary schools increase their nationalistic understanding. Experts validated the learning model and verified it was suitable for use.

2.2 Insight of Nationality

National insight is a collective view that represents a nation’s identity, values, and ideals in the context of societal, national, and state life. Nationalistic insight in education seeks to teach a love of country, an understanding of the need for unity, and a willingness to protect national values (Sartono, Jerusalem, & Rahmawati, 2021). Nationalistic insight includes not only cognitive aspects such as knowledge of the nation, but also emotional aspects.

Three main indicators can be used to measure national insight (Rahmanto & Yani, 2015; Widayanti, Armawi, & Andayani, 2018), namely:

2.2.1 Sense of Nationality

A sense of nationality is the belief that we are one country because of our shared history, challenges, and sense of belonging, as well as our shared ideas, hopes, and ideals for the future.

2.2.2 Understanding of Nationality

Nationalism includes an understanding of what a nation is, including its identity, values, and the history of the formation of the State, including the struggle for independence.

2.2.3 Spirit of Nationality

National spirit is the motivation to maintain national values and foster strong nationalism in the face of global challenges. It also includes the ability of the nation to remain united and adapt to the times.

Nationalistic insight education is critical in the education system for developing a young generation that is not only intellectually superior but also has a love for the country and the courage to protect the nation’s integrity (Setiawan & Wulandari 2020). Nationalistic insight education is extremely crucial in primary school, as students begin to realize their cultural identity and nationalism principles. Learning about nationalistic insights helps children understand their choice to select what they want.

In this study, three indicators of nationalistic insight – a sense of nationality, understanding of nationality, and spirit of nationality – are used to measure the overall nationalistic insight of elementary school students.

3 Research Methodology

This is a quasi-experimental study, using a nonequivalent control design. This research addresses the hypothesis, specifically:

Ho: There is no difference in the average disaster insight between students who follow conventional learning (control class) and students who follow the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model (experimental class).

H1: There is an average difference in disaster insight between students who follow conventional learning (control class) and students who follow the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model (experimental class).

This study included 600 Indonesian primary school students in grade 5. A total of 300 elementary school students were divided into two groups: the control group, which learned conventionally, and the experimental group, which learned using an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model.

The sampling approach utilized in this study was purposive sampling. This purposive sample strategy was adopted to ensure that the elementary school students engaged met the research objectives. Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim (2016) defined purposive sampling as a sampling technique in which researchers purposefully pick samples to satisfy certain research objectives. The reasons for selecting this purposive sampling technique include:

3.1 The Research Focused on Grade 5 Elementary School Students

The research participants are focused on grade 5 elementary school students in this study because at this level students have started a deeper nationality and are following the research objectives related to national insight.

3.2 The Research was Conducted in Schools with Sufficient Access to Technology

The selected schools have sufficient access to technology for the digital learning process, such as computers, laptops, tablets, or smartphones, and also have adequate internet network access. The availability of these tools aims to ensure that the learning process follows the plan.

3.3 Schools Willing to Participate

Only students and schools eager to participate in this learning process are selected with formal consent from students and parents.

This purposive sampling strategy guarantees that the sample’s characteristics match the research context, allowing the study’s results to demonstrate the effectiveness of the learning model.

The sample size was 600 primary school students, selected based on the population’s availability in the research location and the requirement to ensure that the results collected could be statistically accounted for. In this study, the number of students was determined by splitting them equally into experimental and control classes.

Students are not randomly assigned to experimental or control classrooms during group assignments. Grouping is based on the existing classes in each school. However, during the grouping procedure, researchers ensured that the features of the experimental and control classes were equal by considering students’ social–economic–cultural and socioeconomic values to retain the validity of the results.

The data collection process comprises a test. The questionnaire used to assess nationalistic insight includes 30 multiple-choice questions and 6 descriptive questions. This tool was created using three key indicators of national insight: a sense of nationality, understanding of nationality, and spirit of nationality. The explanation of these indicators can be found in Table 2.

Indicators of nationalistic insight

| Indicators of nationalistic insight | Definition | Measured aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of nationality | The awareness that we are one nation constructed by history, struggle, togetherness, and a sense of commonality, as well as common perspectives, goals, and ideals for the future |

|

| Understanding of nationality | Understanding a nation entails understanding its identity, beliefs, and plans, as well as learning about Indonesia’s independence |

|

| Spirit of nationality | The ability to defend national principles, confront dangers, and foster a strong nationalism are all manifestations of national motivation and resilience |

|

The instrument was developed using literature on nationality education and nationalism perspectives. Three civic education specialists validated the tool to ensure the above factors were appropriately portrayed. The experts determined that the questions were legitimate and appropriate for usage. Following expert validation, the test was evaluated with a pilot test of fifty students outside the main sample. All questions were considered valid when the analysis revealed that the r-count value was greater than the r-table value (0.159). According to the reliability measurement, the questions showed a very high level of consistency in measuring nationalistic insight, getting a score of 0.973.

The primary data processing methods used were the paired sample t-test, effect size test, and independent sample t-test, all performed with SPSS 29. Interviews with primary school students provided further data. This interview attempts to learn about primary school kids’ experiences using an ethnosocial-based digital learning model. The interviews focused on how students saw the model, how they found it useful, how they coped with obstacles, and which learning components helped them understand nationalistic insights the best. Students from the experimental group with diverse learning styles and academic backgrounds were purposefully chosen for the interviews. At the end of the learning session, interviews were held in person, lasting 10–15 min for each student. Data were collected and analyzed using thematic approaches to identify relevant themes or patterns.

4 Research Results

After receiving 2 days of instruction, teachers adopted the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model with their students. During this training, teachers are taught syntax, the social system, the reaction principle, the support system, instructional impact, and accompanying impact. Teachers are also instructed on how to use digital platforms, construct customized learning, and incorporate local cultural components into learning activities.

After receiving training, teachers were expected to implement the learning model. Teachers in the experimental class used an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach, whereas teachers in the control class used a conventional learning model. The implementation process lasted 6 months. During the implementation of the teacher learning model, monitoring was carried out to ensure that the teacher’s learning was consistent with the developed model. Three major approaches were used to monitor the fidelity of the model implementation. First, researchers conducted direct observation for half of the learning session to check that the model’s implementation phases were consistent with the design. Second, teachers were requested to complete an evaluation sheet after each learning session to record the activities completed, the problems faced, and the level of student participation. Third, at the end of each week, teachers meet to discuss the model’s implementation progress.

In the experimental class, students learned through an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach that included an introduction, initial exploration, learning differentiation, material deepening, authentic assessment, evaluation, and follow-up. In one example of implementing an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model, at the start of the learning process in the introduction stage, the teacher conveyed the learning theme “Cultural Diversity of the Archipelago” and learning objectives: understanding local cultural values and connecting them to national insight. As a practical step, teachers could use folktales from the student’s study area. Students in West Sumatra, for example, can use the narrative of Batu Malin Kundang as a lesson starter. The teacher also displayed a short video about local traditions, such as traditional dances or usual ceremonies, to capture students’ interest and explain how this learning relates to their daily lives.

At the initial exploration stage, students were requested to share their basic understanding of their respective local cultural traditions through short talks or presentations. Students from Java, for example, may discuss batik, but those from Bali may discuss the ngaben heritage. Teachers utilize a digital platform like Padlet to generate the cultural map and collect the replies from their students. To help students understand, teachers showed interactive videos or 3D simulations of traditional musical instruments and houses. This technique allows educators to obtain a deeper knowledge of their students’ various levels of comprehension and cultural experiences, which serves as the foundation for implementing learning differentiation.

At the learning differentiation stage, teachers separated students into groups based on their learning styles (which had been identified at the beginning of school) and level of comprehension. For example, students who use visual learning styles are given materials about local traditions and infographics. Meanwhile, students who use kinesthetic learning styles are given video instructions to make simple batik. In addition, students who use reflective learning styles are given narrative texts about local culture to examine its cultural values. Furthermore, teachers presented real-life examples of how traditional ceremonies represent values of togetherness and community service, all are linked to academic concepts such as national insight in Civic Education.

During the material deepening phase, students were invited to collaborate in groups to develop projects that connected academic concepts with local culture. Examples of projects included creating a digital presentation on “The Role of Local Culture in Maintaining National Unity” and developing a short video documentary of traditional practices in each region, along with an appraisal of its values. Teachers provided video lessons to help students comprehend the project.

The following stage is reflection and application. Students should reflect and apply what they have learned. The teacher asked them to record their reflections in digital journals or video logs (vlogs). One recommended reflection question is, “What lessons did I learn from this traditional ceremony?” How can I apply this principle in my daily life? Students were invited to plan a school activity that included different local cultures, such as a cultural festival or a traditional attire competition.

During the authentic assessment phase, teachers assessed students’ learning through portfolios or digital projects that included ethnosocial values. Students, for example, produced an interactive infographic depicting local traditions while keeping national principles in mind. A pre-prepared criteria was utilized to examine student’s capacity to connect academic concepts to local culture. Finally, evaluation and follow-up occur. The teacher thoroughly reviewed the learning process, noting the approaches’ strengths and faults. Furthermore, teachers provided enrichment to students who had a strong understanding of the culture, such as in-depth discussions regarding the role of culture in the formation of national identity. Teachers also gave extra support to less engaged students, such as through more focused individual talks.

In conventional classrooms, learning starts with an introduction from the teacher to express the learning theme and objectives. The teacher then presented the materials to the students. Following the presentation, students were given tasks based on the subject presented. In the final stage, the teacher conducted a perception equation with students, which involved ensuring that pupils understood the content equitably through discussion or question-answer sessions that focused on the most significant parts of the subject acquired. Following that, the teacher evaluated the exercises that the students completed. This evaluation was conducted using a test designed to examine students’ nationalistic insights, with a focus on their ability to connect academic topics to relevant local and national cultural values.

At the end of the learning process, each class was assessed for nationalistic insight using a prepared test. Table 3 of the data tabulation displays the findings of the measurement of nationalistic insight.

Data tabulation

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test experiment | 300 | 43.33 | 63.86 | 45.86 | 2.173 |

| Post-test experiment | 300 | 86.33 | 94.33 | 91.26 | 2.492 |

| Pre-test control | 300 | 42.43 | 60.56 | 45.16 | 2.475 |

| Post-test control | 300 | 44.93 | 71.33 | 53.33 | 2.582 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 300 |

Table 3 data tabulation shows the scores earned by students in the control and experimental classes. Furthermore, the normality measurement is performed to determine whether the data being utilized is normally distributed, which is required for further measurements. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov computation is used in this normality test since the calculated sample exceeds 100 samples. Table 4 displays the results of the normality test calculations.

Normality test results

| Class | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality insight | Pre-test experiment | 0.283 | 300 | 0.111 |

| Post-test experiment | 0.193 | 300 | 0.131 | |

| Pre-test control | 0.272 | 300 | 0.134 | |

| Post-test control | 0.251 | 300 | 0.152 |

From Table 4, the normality test results in the Sig value section show that the Sig value is greater than 0.05. This result shows that all classes are normally distributed. These results indicate that the following measurement, the paired sample t-test, can be performed. The paired sample t-test compares two data sets to determine whether there is a difference between pre-test scores and post-test scores. The paired sample t-test was used to compare the control and experimental groups in terms of enhancing students’ nationalistic insight.

This test is specifically designed to answer the question of whether the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach influences primary school students’ nationalistic insight. The calculation results are shown in Table 5 of the paired sample t-test findings.

Paired sample T-test results

| Mean difference | Std. dev | Std. error mean | 95% Confidence interval of the difference | t | df | Sig. (2 tailed) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | Pre-test experiment – Post-test experiment | 54.392 | 3.492 | 0.420 | 22.039 | 33.382 | 47.392 | 299 | 0.000 |

| Pair 2 | Pre-test control – Post-test control | 0.837 | 1.212 | 0.192 | 1.320 | 1.392 | 5.492 | 299 | 0.212 |

Table 5 shows that the Sig. (two-tailed).000 is less than 0.05. This finding demonstrates that there is an average difference between the Pre-test Experiment and Post-test Experiment groups. This research suggests that the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning paradigm has an impact on primary school students’ nationalistic insight. In pair 2, the Sig. (two-tailed) score is 0.212, which is greater than 0.05. This finding demonstrates that there is no difference in the average between the Pre-test Experiment and Post-test Experiment groups. This finding demonstrates that conventional learning models do not affect elementary school kids’ nationalistic insight.

The next measurement is effect size. The purpose of this measurement is to determine the amount of influence that an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model has on primary school pupils’ nationalistic insight. Table 6 shows the effect size calculations.

Effect size calculation results

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square | Std. error of the estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.883a | 0.843 | 0.434 | 0.972 |

Table 6 shows that the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model has a considerable influence on the nationality of elementary school children, as indicated by an R-value of 0.883. The R Square value also indicates that the deployment of ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning models influences 84.3% of elementary school kids’ nationality insight, with the remainder influenced by other factors. Given the effect size, it is possible to conclude that using an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning paradigm has a considerable impact on elementary school kids’ nationalistic insight.

To sharpen the findings, an independent sample t-test was used. Previously, a homogeneity variance test was performed as a basic assumption need. Table 7 displays the homogeneity test calculations as follows:

The homogeneity test results

| Class | Statistic | df | df2 | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster awareness | Based on mean | 104.392 | 1 | 598 | 0.218 |

| Based on media | 92.871 | 1 | 598 | 0.432 | |

| Based on median and with adjusted df | 92.871 | 1 | 114.942 | 0.214 | |

| Based on trimmed mean | 104.291 | 1 | 598 | 0.293 |

According to the calculation findings in Table 7, the Sig. Value in the based on mean section is 0.218 higher than 0.05. This finding indicates that both data sets are derived from homogeneous data. After determining that the group has a homogeneous variance, the paired sample t-test can be performed. The paired sample t-test compares the nationalistic insights of students in the control and experimental groups. In particular, the calculation seeks to answer the question “Is there a difference in the nationalistic insight of elementary school students between the group that learns using the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model and the group that learns using the conventional learning model?” The data compared is the data obtained after the learning process occurrence (post-test). The independent sample t-test findings are as follows:

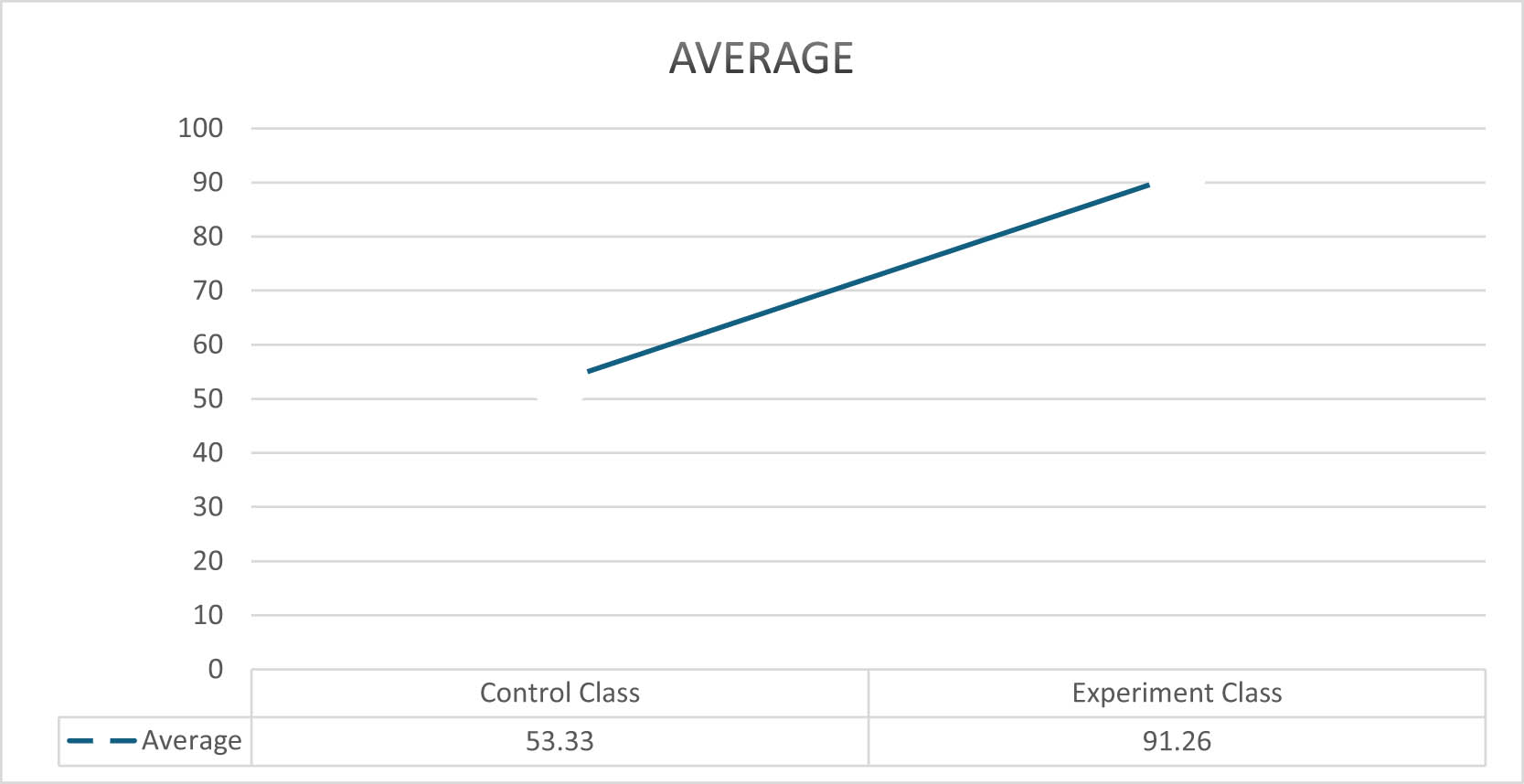

In Table 8, the sig. value is 0.000. This sign value is less than 0.05. This finding indicates that there is an average difference in nationalistic insight between elementary school students who learn using an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model and elementary school students who learn using a conventional learning model. This difference is also evident in the post-test results of the experimental and control classes in Table 1. To make things easier, refer to Figure 1.

Independent sample t-test results

| Levene’s test for equality of variance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | ||

| Nationality insight | Equal variances assumed | 123.642 | 0.000 | 71.027 | 382 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 71.027 | 101.482 | |||

Control class and experimental class scores.

Figure 1 shows that students in the control class (learning with conventional learning models) had a lower average score (53.33) than students in the experimental class (91.26) (learning with ethnosicial-based differentiated digital learning model). This significant distinction demonstrates the effectiveness of the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model in enhancing students’ nationalistic insight. This figure clearly shows that students who learn utilizing an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach are influential and effective in improving elementary school students’ nationalistic insight.

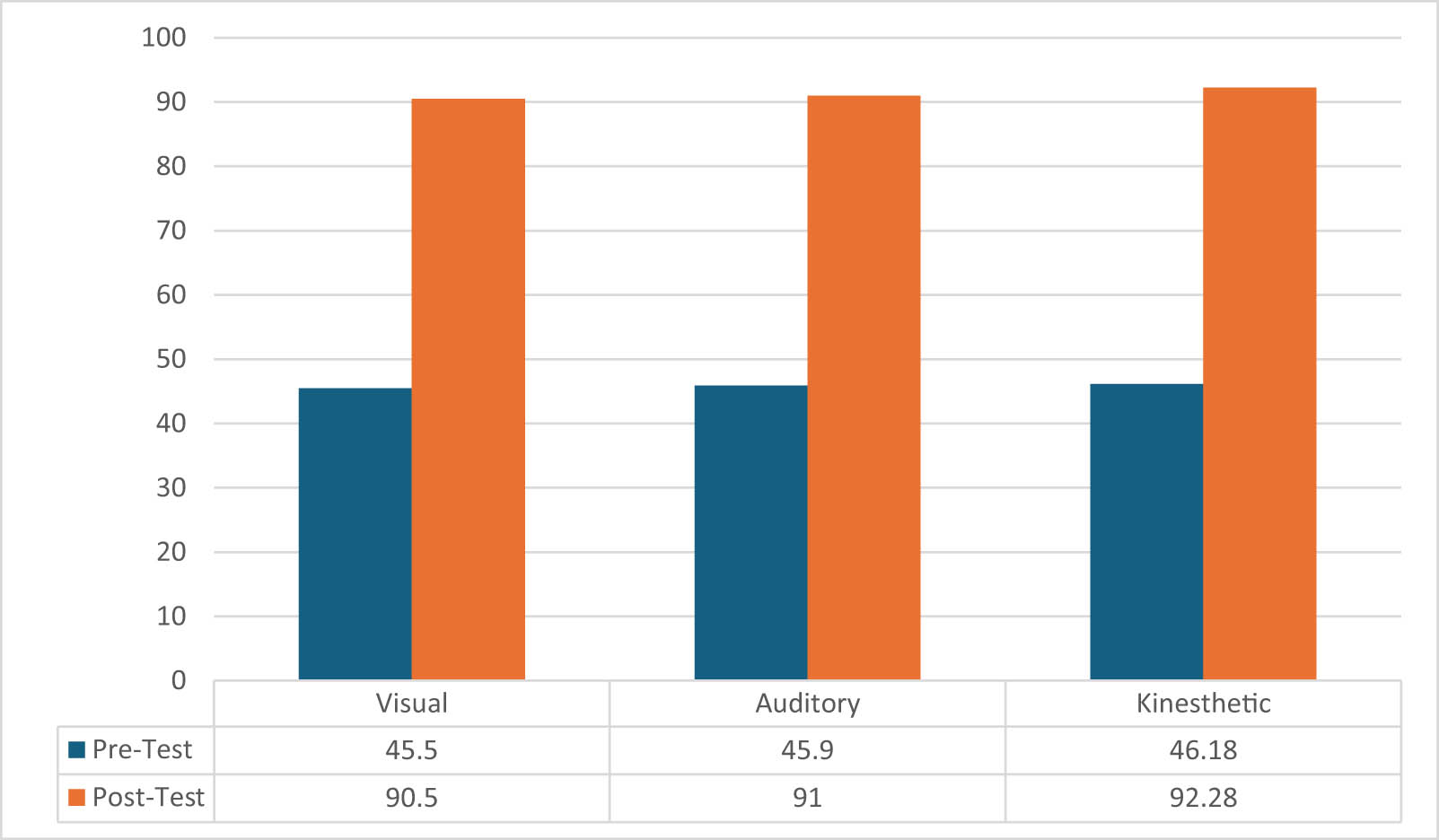

The results of this calculation also show that students with diverse learning styles have a higher value of national insight when they learn utilizing an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model. The figure below illustrates this.

Figure 2 shows that the average national insight score increased significantly across three types of learning (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic). For example, students with a visual learning style had an average pre-test score of 45.5, which improved to 90.5 on the post-test. Students with auditory (45.9–91) and kinesthetic (46.18–92.28) learning methods showed similar increases.

Mean score of nationalistic insight based on learning style of elementary school students.

This finding indicates that the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model can assist students with diverse learning styles in better understanding the subject provided and improving their nationalistic perspective. Thus, the findings of this study support the notion that the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning paradigm improves elementary school kids’ nationalistic insights, regardless of their learning styles.

5 Discussion

Overall, this study demonstrates that an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning strategy improves elementary school students’ nationalistic insight. This study presents an innovative approach to increasing students’ nationalistic awareness by merging digital technology with their ethnosocial (social and cultural) background, which has not previously been studied by scholars. Ricoy and Sánchez-Martínez (2022) found that using a digital approach with gamification can improve ecological awareness and digital literacy among elementary school students in Spain. However, the study only focuses on environmental awareness and does not consider ethnosocial aspects. Research conducted by Kiwango (2020) examined the integration of technology during out-of-school learning in Tanzania, to improve academic achievement. The study focuses on the importance of contextualizing technology in the school learning process without linking it to national insight dimensions. Guo’s research (2023) investigated digital learning models within the context of macro-education changes that aim to boost students’ digital abilities and innovation. This study claims that academic learning has improved, however, it does not investigate ethnosocial components.

Chen et al. (2017) investigated how a mobile-based learning approach may improve primary school pupils’ metacognition awareness. This learning style can promote metacognitive awareness, involvement, and academic accomplishment, but it does not address ethnosocial and national insight. Castañeda, Marín, and Villar-Onrubia (2023) research underlined the significance of building critical digital literacy abilities in prospective educators in Spain. This study attempted to improve digital skills and teacher education, but it did not look at digital learning through a more nationalistic view, as this one did. As a result, this study presents an innovative contribution by merging differentiated and ethnosocial approaches in the digital learning process designed to increase primary school kids’ nationalistic insight. This discovery is significant for the learning process in primary schools because there is currently limited study linking digital learning technology with ethnosocial aspects (local culture) in the context of growing national insight.

5.1 Effectiveness of Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model

The ethnosocial-based digital learning model is useful for elementary school kids in enhancing nationalistic understanding because it connects learning concepts to students’ cultural identities. This model can make the subject more relevant and contextual to students. Elementary school students are children in the developmental stage, during which they begin to establish a basic awareness of themselves, their culture, and their social surroundings. During this stage, students will benefit from contextual learning to fully comprehend content (Kenedi, Helsa, Ariani, Zainil, & Hendri, 2019; Zainil, Kenedi, Indrawati, & Handrianto, 2023). Ethnosocial-based learning capitalizes on the unique characteristics of local culture by connecting subject matter to components such as folklore, traditions, and values that students are familiar with. This technique makes academic and national concepts more understandable and relevant to student’s daily lives, resulting in a more integrated and natural learning experience.

Using an ethnosocial approach will naturally boost students’ comprehension of multiculturalism, which is a critical component of national education (Sahudra, Kenedi, & Asnawi, 2023). In a multicultural country, local culture-based learning will help students appreciate the differences between ethnic groups (Yuldashbayevna, 2020). Using this method, they will learn to appreciate cultural diversity, which is part of the wealth that must be preserved. In addition to improving national insight, this strategy can foster the values of tolerance and respect for others. For example, when teaching students the notion of mutual collaboration, teachers can tie it to local cultures and social customs that demonstrate the significance of togetherness, allowing students to readily understand the concept not just theoretically but also contextually.

This ethnosocial-based digital learning model offers additional advantages over conventional learning in that it may awaken students’ interest in learning and engage them in the learning process. Teachers can employ technology to present lessons interactively, beginning with multimedia, learning videos, and simulations that incorporate cultural components (Ramadhani, Sahudra, & Kenedi, 2024). In general, elementary school students choose visually stimulating and engaging activities. This activity can be aided by technology-based learning. Additionally, the digital technology-based learning method enables students to learn through various customized learning experiences. For example, digital games designed to honor the efforts of heroes or teach students about the history of the country will be more appealing to them than having them read or hear explanations from teachers.

Digital techniques also offer the flexibility required for differentiated learning. Every primary school student has unique learning preferences and styles (Asnawi et al., 2023). By optimizing this technology, teachers can deliver learning materials that are suited to their students’ learning styles. Teachers can design learning stages with varying levels of difficulty. This technique is designed to allow pupils to learn according to their capacities. For example, students who are slow to grasp the material can be helped by the teacher providing additional videos or material that students can use to understand learning, whereas students who quickly master the material can be helped by assigning more difficult tasks that require more creativity related to local culture in depth. This technique allows students to learn according to their ability without feeling burdened.

Ethnosocial digital learning can also help students improve their social skills. During this learning process, students will participate in collaborative activities such as group projects highlighting local culture or social activities relating to nationality. Activities like this teach students about the nature of cooperation, how to exchange ideas, and how to respect the perspectives of others, all of which can indirectly improve students’ social skills (Bassachs, Cañabate, Serra, & Colomer, 2020; Salimi & Dardiri, 2021). For example, students might collaborate in the form of project activities to explore their own culture as well as the cultures of others, allowing them to learn that each existing culture has its own uniqueness and importance in society.

As a result, the ethnosocial-based digital learning model is highly effective at increasing elementary school kids’ nationalistic insight. This learning model is not only contextual and relevant to students’ local culture but also employs a technology-based learning strategy that appeals to and supports students’ diverse learning styles. The combination of numerous approaches can help primary school pupils build important learning skills while also instilling tolerance and nationalism. This learning approach is not only focused on the academic process, but it also contributes to the formation of student character values, which have an impact on elementary school kids’ national understanding.

5.2 The Role of Differentiated Learning in Enhancing Students’ Nationalistic Insight

The role of diversified learning in this learning style influences elementary school students’ national understanding. Differentiated learning is the adaptation of the learning process to the needs of students depending on their level of ability, interest, and learning style (Faigawati et al., 2023; Mulyawati, Zulela, & Edwita, 2022). This unique method is essential in nationality education since the abstract concept of nationality requires a strategy that students can easily understand. Elementary students are often in the process of developing their cognitive and emotional components, therefore a variety of approaches are required to absorb knowledge (Achmad, Rachman, Aras, & Amran, 2024). Some students may learn more quickly through visual images, but others would learn best through direct experience or simply listening. With this diversified learning method, teachers can tailor the learning process (materials and teaching materials) to their students’ distinctive characteristics, resulting in more meaningful and effective learning.

Differentiated learning also assists students in understanding complex ideas in nationalistic insight by making the information more relevant to their lives. Differentiated learning allows teachers to tie a subject to real-life situations and cultures that students are familiar with (Cornett, Paulick, & van Hover, 2020). For example, by learning about cooperation, teachers might use examples from local cultures, such as community work or traditional ceremonies, to demonstrate cooperation. This technique allows students to not only study conceptually but also connect the learning process to real-world situations, making it easier for them to understand.

Differentiated learning also allows for the utilization of many types of media and learning formats. Some students may learn the concept of nationality more quickly through stories containing national values, whilst others may understand information more rapidly through movies and visual images showcasing the cultural diversity of Indonesians. Teachers can offer the subject in many formats, such as folklore or documentary movies. This approach makes nationality lessons more vivid, relevant, and understandable for children with diverse learning styles.

Differentiated learning is also vital for ensuring that children learn effectively within their developmental zones. Each student’s knowledge varies, particularly when it comes to abstract, contemplative notions like nationalistic insight. The key aim of differentiated learning is to modify the level of learning difficulty based on students’ academic abilities. Students with greater abilities may be assigned more difficult activities, such as conducting cultural studies in other regions or writing essays on the importance of unity in the face of diversity. Students who require more attention can be provided with easier material, either by analogy, videos, or simple ways adapted to student needs. This learning technique allows them to learn according to their ability without feeling burdened. This individualized learning also keeps students from becoming bored or frustrated while trying to master difficult concepts. Those who learn the topic quickly can be assigned extra assignments, whilst individuals who require more attention can be assigned information in a simpler format. Differentiated learning guarantees that all students are engaged and have a vested interest in fully comprehending the material.

Differentiated learning also adapts to students’ learning styles, which increases students’ interest and motivation to improve national insight. The fact that all students learn in the same way; some learn best through verbal engagement, while others prefer writing or hands-on activities. The ethnosocial approach allows teachers to encourage learning approaches that are appropriate for their student’s learning patterns. For example, students with visual preferences like to watch videos on nationality, students with audio preferences prefer to listen to tales about nationality, and kinesthetic learners prefer role-playing. With this diversity of options, students will be motivated because the learning approach corresponds to how they grasp the topic. This personalization will help to retain student demand for educational resources. When students feel valued in a learning process that is adapted to their learning style, they will be able to learn the content more effectively (Palieraki & Koutrouba, 2021). This type of approach is essential in the process of improving nationalistic insight because it teaches the abstract concept of nationalistic insight in an enjoyable way. This diversified learning technique allows students to learn in a way that is comfortable for them, which increases student motivation to develop nationalistic insight.

The customized approach in the ethnosocial learning model also helps kids acquire a sense of pride in their cultural identity. Cultural variety is a source of national pride. The practice of incorporating local cultural elements into learning and offering actionable examples of culture will help pupils feel proud of their heritage. When culture is included in the learning process, children feel respected for their culture, which fosters a sense of pride and respect for other cultures. This method will result in tolerance because they perceive diversity as a resource that unites rather than a source of conflict. Thus, ethnosocial-based differentiated learning not only enhances students’ intellectual understanding of nationalism but also strengthens their national identity. Nationality learning that is adjusted to individual learning styles will connect students to the learning process, allowing the concept of nationality to become more than simply a theory but also a part of their identity as citizens who value variety.

As a result, the ethnosocial-based digital learning model is very sufficient in meeting students’ needs tailored to their circumstances, increasing students’ understanding of national insight, and instilling a sense of pride in culture while respecting the culture of others to improve students’ national insight. This learning method is not only easier to understand, but also more meaningful because it is adjusted to students’ learning styles, talents, and cultural backgrounds. This learning strategy assures relevant and inclusive national education while also supporting character development by students’ social and cultural circumstances, resulting in increased nationalistic insight.

5.3 The Influence of Digital Technology on Nationalistic Insight

Digital technology plays a significant role in improving student engagement in nationalistic insight learning. When applied normally, nationalistic insight is regarded as a vague, tedious, and uninspiring learning experience. Technology-based learning can capture primary school kids’ attention since it is relevant to their daily experiences (Arwin, Kenedi, Anita, Hamimah, & Zainil, 2024; Zainil, Kenedi, Rahmatina, Indrawati, & Handrianto, 2024). The technology-based learning method can help students participate in various activities by providing engaging media and tools. The use of technology in pride learning, such as animation, 3D graphics, and interactive videos, will provide a strong visual learning experience. Students will grasp abstract themes of pride, such as unity, diversity, and national identity, more tangibly. For example, to grasp the process of national struggle, students can view documentary videos, which allow them to understand and feel the event. This technique will assist them to improve their comprehension and memory of the event. Students can better comprehend the role of local culture in establishing a stronger nation by visualizing historical events, national figures, and cultural variety.

Interactive movies used in this learning model play an essential part in boosting primary school pupils’ national awareness. Interactive movies can inspire elementary school students to participate in the learning process by asking questions while they watch (Hapsari & Hanif, 2019; Kenedi, Anita, & Afrian, 2023). Interactive movies offer history and culture, requiring students to make decisions and accept responsibility for their choices. Students, for example, can choose the actions of a hero in a crisis during the independence war or strengthen local practices from various regions of Indonesia. Using interactive videos, children will be able to participate emotionally and cognitively, sense the significance of nationality, and experience an environment that is familiar to them, making them feel more connected to the material.

The digital simulation of this learning technique also influences nationalistic insight. The simulation technique allows students to realistically experience the processes of culture, history, and national values. For example, simulations aimed at demonstrating the process of life prior to independence or cultural interaction in Indonesia can provide students with a new perspective on unity and tolerance. Simulations can help students gain hands-on experience (Poultsakis, Papadakis, Kalogiannakis, & Psycharis, 2021; Tigowati, Efendi, & Budiyanto, 2017). Students can experience the challenge and importance of national principles, transforming nationhood from a theoretical concept to a way of life. Digital simulations can help people explore and comprehend culture entertainingly, increasing curiosity about nationalistic insights (Gebreheat, Whitehorn, & Paterson, 2022; Nafıdı, Alamı, Zakı, El Batrı, & Afkar, 2018).

Digital technology also enables project-based or collaborative learning, which improves students’ nationalistic understanding. Students can collaborate via internet platforms on assignments, conversations, or projects about national history, traditions, culture, and all other nationalism-related topics. The collaboration not only broadens elementary school children’s nationalistic insight but also teaches teamwork and appreciation for diversity.

Overall, in the modern era, digital technology makes primary school children’s learning experiences more interesting. Students can gain patriotic insights by using digital technologies like multimedia, interactive movies, and digital simulations. Students study not only the idea of nationalism but also how to apply it.

5.4 Potential, Practical Recommendations, Challenges, and Obstacles

The ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model aims to improve students’ understanding of their country by infusing elements of local culture into their digital learning experience. This method teaches students not only academic material but also cultural values that reflect the nation’s identity. Folklore, national symbols, and social customs are immediately integrated into the lessons, fostering a deep bond between students and their cultural context (Sugara, 2022).

The incorporation of local cultural components into digital learning allows learners to recognize and value Indonesia’s cultural diversity. This enhances pupils’ sense of nationhood, making them proud to be citizens while also teaching them the values of the nation’s ideology and struggle for independence. This process also promotes a spirit of nationhood, encouraging people to stay together and contribute to the country’s success.

The concept also offers students contextual, relevant, and adaptive learning possibilities using digital technologies. The concept broadens students’ nationalistic perspectives and trains them to be a generation that loves their homeland and can handle issues globally without losing their national identity. Culture-based activities adapted to students’ learning styles and skills assist pupils in connecting national values to everyday concerns (Istika, Hartono, & Siswanto, 2024).

This study can be utilized as a practical recommendation for policymakers, educators, and curriculum developers to create more relevant and contextualized education. Policymakers should promote the incorporation of local cultural components into the national curriculum, as well as develop school technological infrastructure to support the deployment of various digital learning methods. Educators should receive specialized instruction on how to incorporate digital learning into local culture. They should also develop strategies that address the specific needs of students to broaden their national horizons. Curriculum creators should build a curriculum that blends technology and national values, and then perform periodic evaluations to ensure that this learning model is relevant in enhancing students’ national identity. By applying these recommendations, it is expected that this learning approach will improve students’ nationalistic insights and prepare them to handle larger global concerns.

In diverse educational contexts, ethnosocially differentiated digital learning models confront numerous obstacles and barriers. Inequitable access to technology is one of the major challenges. Lack of technology infrastructure can be a significant barrier to implementing this strategy in some areas, particularly in remote areas. Restrictions include limited equipment, insufficient internet connectivity, and a lack of technological training for teachers.

The effectiveness of this model can also be affected by students’ cultural and social differences. Students from varied cultural origins may struggle to identify the local cultural features included in their studies. As a result, the cultural components taught must be customized to the different social contexts of each region.

In addition, there are concerns about teachers’ capability and ability to apply this model. To apply a technology-based and ethnosocial learning model, teachers must not only be technologically adept but also comprehend different cultures and national insights. Without adequate preparation, teachers may struggle to manage learning that incorporates digital features and local culture.

As a result, this model has the potential to significantly boost students’ national insight. However, additional efforts are required to address issues such as technological accessibility, teacher preparedness, and cultural diversity.

6 Conclusion

This study demonstrates how an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model influences primary school students’ nationalistic insights. Those who learn through an ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning approach have a higher level of nationalistic understanding than those who learn conventionally.

7 Research Limitations

Some drawbacks to this study should be noted. First, this research was developed as a quasi-experiment. This means that students were not randomly assigned to experimental or control groups. This may lead to biases, such as differences in baseline characteristics between groups, affecting the study’s outcomes. The findings of this study may not be generalizable to different populations or educational situations, despite efforts to ensure that all students were equal in terms of average academic grades and socioeconomic background.

Second, to apply the digital learning model, this study will require proper access to technology. Limited devices or internet connections in specific regions may make it difficult to apply this concept. Furthermore, the success of this model is strongly dependent on the teacher’s ability to understand the pedagogical technology content knowledge framework (TPACK). This ability is required to successfully combine technology, learning materials, and ethnosocial approaches.

8 Research Future Recommendation

Future research is required to address the current constraints and broaden the scope of the application of the ethnosocial-based differentiated digital learning model. One alternative study option is to create more contextualized and diversified learning materials that span a broader spectrum of ethnicity and cultural studies to fully depict the diversity of national culture. In addition, long-term or longitudinal studies are required to assess the model’s impact over time, including its influence on students’ attitudes, behaviors, and nationalistic perspectives. Researchers might also investigate the use of increasingly innovative technologies, such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence, to make students’ learning experiences more engaging and immersive. This study’s direction seeks to improve the effectiveness of learning models in a variety of diverse educational contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service (DRTPM), Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for supporting the funding of this research. We also extend our sincere thanks to Universitas Samudra for facilitating this research.

-

Funding information: This research is funded by the Budget Implementation List (DIPA), Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service (DRTPM), Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia in 2024, under the main contract 085/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2024 and derivative contract 455/UN54.6/PG/2024.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed significantly to the conception, development, and completion of this research. Asnawi (Corresponding Author) led the overall study, including conceptualization, methodology design, and manuscript writing. Ary Kiswanto Kenedi contributed to the theoretical framework and literature review, ensuring a strong foundation for the study. Tengku Muhammad Sahudra was responsible for data collection, processing, and initial analysis. Dini Ramadhani played a key role in designing the differentiated digital learning model and its implementation. Ronald Fransyaigu handled the statistical analysis and interpretation of the findings. Asna Mardin contributed to the discussion section by aligning the results with nationalistic insights and educational policies. Arwin provided critical revisions, proofreading, and final editing to enhance the clarity and coherence of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper before submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Asnawi, upon reasonable request. Due to ethical and confidentiality considerations, certain datasets may be restricted and provided only for research purposes. Any additional information related to the study can also be made available upon request.

References

Achmad, W. K. S., Rachman, S. A., Aras, L., & Amran, M. (2024). Differentiated instruction in reading in elementary schools: A systematic review. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13(3), 1997–2005. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v13i3.27134.Suche in Google Scholar

Arwin, A., Kenedi, A. K., Anita, Y., Hamimah, C. H., & Zainil, M. (2024). STEM-based digital disaster learning model for disaster adaptation ability of elementary school students. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education ISSN, 13(5), 3248–3259. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v13i5.29616.Suche in Google Scholar

Asnawi, A., Sahudra, T. M., Ramadhani, D., Kenedi, A. K., Aosi, G., Wardhana, M. R., & Khalil, N. A. (2023). Development of digital diagnostic test instruments for differentiated learning process in elementary schools. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA, 9(Special Issue), 460–466. doi: 10.29303/jppipa.v9iSpecialIssue.6125.Suche in Google Scholar

Bassachs, M., Cañabate, D., Serra, T., & Colomer, J. (2020). Interdisciplinary cooperative educational approaches to foster knowledge and competences for sustainable development. Sustainability, 12(20), 8624. doi: 10.3390/su12208624.Suche in Google Scholar

Bideau, F., & Kilani, M. (2012). Multiculturalism, cosmopolitanism, and making heritage in Malaysia: A view from the historic cities of the Straits of Malacca. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 18, 605–623. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2011.609997.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonk, C. J., & Graham, C. R. (2012). The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs. San Fransisco: Wiley + ORM. https://curtbonk.com/toc_section_intros2.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Cahyani, C., & Isah, I. (2016). The national character education paradigm in the Indonesian language instructions. In Ninth International Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 9) (pp. 273–275). Bandung: Atlantis Press. doi: 10.2991/CONAPLIN-16.2017.61.Suche in Google Scholar

CASEL. (2013). Effective social and emotional learning programs, preschool and elementary school edition. Chicago: KSA-Plus Communications, Inc.Suche in Google Scholar

Castañeda, L., Marín, V. I., & Villar-Onrubia, D. (2023). Relational topologies in the learning activity spaces: Operationalising a sociomaterial approach. Educational Technology Research and Development, 2023, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11423-023-10296-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Z., Zhang, Y., Bai, Q., Chen, B., Zhu, Y., & Xiong, Y. (2017). A PBL teaching model based on mobile devices to improve primary school students’ meta-cognitive awareness and learning achievement. In 2017 International Conference of Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT) (pp. 81–86). IEEE. doi: 10.1109/EITT.2017.27.Suche in Google Scholar

Cornett, A., Paulick, J., & van Hover, S. (2020). Utilizing home visiting to support differentiated instruction in an elementary classroom. School Community Journal, 30(1), 107–137. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1257636.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Djumadiono, D. (2019). The effect of case study learning methods on the learning outcomes of national insight of the Republic of Indonesia. Monas: Jurnal Inovasi Aparatur, 1(1), 24–29. https://garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/documents/detail/2507760.10.54849/monas.v1i1.4Suche in Google Scholar

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.Suche in Google Scholar

Faigawati, F., Safitri, M. L. O., Indriani, F. D., Sabrina, F., Kinanti, K., Mursid, H., & Fathurohman, A. (2023). Implementation of differentiated learning in elementary schools. Jurnal Inspirasi Pendidikan, 13(1), 47–58. doi: 10.21067/jip.v13i1.8362.Suche in Google Scholar

Fitri, N., & Habiby, W. N. (2023). Teaching the character of nationalism in historical materials in elementary schools. Santhet (Jurnal Sejarah Pendidikan Dan Humaniora), 7(1), 99–107. doi: 10.36526/santhet.v7i1.2578.Suche in Google Scholar

Gebreheat, G., Whitehorn, L. J., & Paterson, R. E. (2022). Effectiveness of digital simulation on student nurses’ knowledge and confidence: An integrative literature review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 13, 765. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S366495.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, Y. (2023). Digital learning models in macro-educational reform. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 9(1), 1–17. doi: 10.2478/amns.2023.2.01297.Suche in Google Scholar

Hapsari, A. S., & Hanif, M. (2019). Motion graphic animation videos to improve the learning outcomes of elementary school students. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(4), 1245–1255. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.8.4.1245.Suche in Google Scholar

Hendrowibowo, L., Harsoyo, Y., & Sunarso, S. (2020). Students’ commitment to national heritage, patriotism and nationalism (The case of Indonesian elementary students in border area with East Timor). Preprints, 2020, 2020120161. doi: 10.20944/preprints202012.0161.v1.Suche in Google Scholar

Hernández-Martos, J., Morales-Sánchez, V., Monteiro, D., Franquelo, M. A., Pérez-López, R., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Reigal, R. E. (2024). Examination of associations across transformational teacher leadership, motivational orientation, enjoyment, and boredom in physical education students. European Physical Education Review, 30(2), 194–211. doi: 10.1177/1356336X231194568.Suche in Google Scholar

Isabella, M. (2017). Strengthening the national resilience of Indonesia through socialization of national insight. In International Conference on Democracy, Accountability and Governance (ICODAG 2017) (pp. 224–228). Atlantis Press. doi: 10.2991/icodag-17.2017.42.Suche in Google Scholar

Istika, W., Hartono, W., & Siswanto, J. (2024). Analisis Gaya Belajar Diferensiasi Terintegrasi Budaya (CRT) Pada Materi Ekonomi Menggunakan Pembelajaran Berbasis Masalah. SOCIAL: Jurnal Inovasi Pendidikan IPS, 4(1), 17–24. doi: 10.51878/social.v4i1.3074.Suche in Google Scholar

Izzati, K. I., & Adiarti, W. (2020). Learning program of national vision cultivation to Indonesian children with permanent resident status. BELIA: Early Childhood Education Papers, 9(1), 13–19. doi: 10.15294/belia.v9i1.32515.Suche in Google Scholar

Junaeda, S., Kesuma, A., Sumilih, D., Dahlan, M., & Bahri, B. (2022). Cultivating nationalism and national insight through film for students at MTs Miftahul Ulum, Gowa Regency, South Sulawesi. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 149, p. 01013). EDP Sciences. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/202214901013.Suche in Google Scholar

Kenedi, A. K., Anita, Y., & Afrian, R. (2023). The impact of the virtual-based disaster learning model on elementary students’ understanding of COVID-19 disaster-learning. European Journal of Educational Research, 12(2), 1059–1069. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.12.2.1059.Suche in Google Scholar

Kenedi, A. K., Helsa, Y., Ariani, Y., Zainil, M., & Hendri, S. (2019). Mathematical connection of elementary school students to solve mathematical problems. Journal on Mathematics Education, 10(1), 69–80. doi: 10.22342/jme.10.1.5416.69-80.Suche in Google Scholar

Kiwango, T. (2020). Impact of modelling technology integration for out-of-school time learning on academic achievement. EPRA International Journal of Research and Development, 5(5), 292–299. doi: 10.36713/epra3369.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, S., & Jan, J. (2013). Mapping research collaborations in the business and management field in Malaysia, 1980–2010. Scientometrics, 97, 491–517. doi: 10.1007/s11192-013-0994-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Mubarok, H., & Anggraini, D. M. (2021). Analysis of factors improving insights on national character education of elementary school teachers. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Innovation and Quality Education (pp. 1–6). doi: 10.1145/3516875.3516893.Suche in Google Scholar