Abstract

In this paper, we study the approximation of π through the semiperimeter or area of a random n-sided polygon inscribed in a unit circle in ℝ2. We show that, with probability 1, the approximation error goes to 0 as n → ∞, and is roughly sextupled when compared with the classical Archimedean approach of using a regular n-sided polygon. By combining both the semiperimeter and area of these random inscribed polygons, we also construct extrapolation improvements that can significantly speed up the convergence of these approximations.

1 Introduction

The classical approach to estimate π, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, based on the semiperimeter (or area) of regular polygons inscribed in or circumscribed about a unit circle in ℝ2 can be traced to Archimedes more than 2000 years ago [1]. Although the lower bound π ≈ 3 and better estimates such as π ≈ 3.125 were known to the Babylonians and the Egyptians as early as 4000 years ago, it was Archimedes who first used the polygonal method to calculate π to any desired degree of accuracy. On the one hand, Archimedes correctly recognized that π lies between the semiperimeter 𝓢n of a regular n-sided polygon inscribed in the unit circle and the semiperimeter

satisfied by the semiperimeters 𝓢n = n sin (π/n) and

To introduce some modern flavor to the ancient Archimedean approach, we consider in this paper the problem of approximating π using the semiperimeter 𝓢n or area 𝓐n of an n-sided random polygon inscribed in the unit circle. For simplicity, we assume that all vertices are independently and uniformly distributed on the circle. By connecting these vertices consecutively, we then obtain a random polygon inscribed in the unit circle. Note that although such random polygons will rarely be regular (when the vertices happen to be all equally spaced on the circle), it is intuitively clear that, as n becomes large, these random vertices tend to spread out and become “evenly” distributed on the circle so that the semiperimeter or area of the circle may still be well approximated by the corresponding semiperimeter or area of the inscribed random polygon. This is confirmed by the strong convergence results stated in the theorem below.

Theorem 1.1

Given n ≥ 3, let 𝓢n and 𝓐n be the semiperimeter and area of a random inscribed polygon generated by n independent points uniformly distributed on the unit circle. Then, with probability 1, both 𝓢n and 𝓐n converge to π as n → ∞.

Note that Theorem 1.1 improves on the weak convergence results previously obtained by Bélisle [2]. In fact, for n large, we can also obtain the error estimates

Thus, compared with a regular n-gon which happens to minimize the approximation error, on average, the approximation error is roughly sextupled when a random n-gon is used. Additionally, we will also show that, for both Archimedean and our random approximations of π, by applying extrapolation type techniques [3], it is possible to construct some simple linear combinations of 𝓢n and 𝓐n that can greatly improve the accuracy of these approximations.

2 Basic convergence estimates for the Archimedean approximations of π

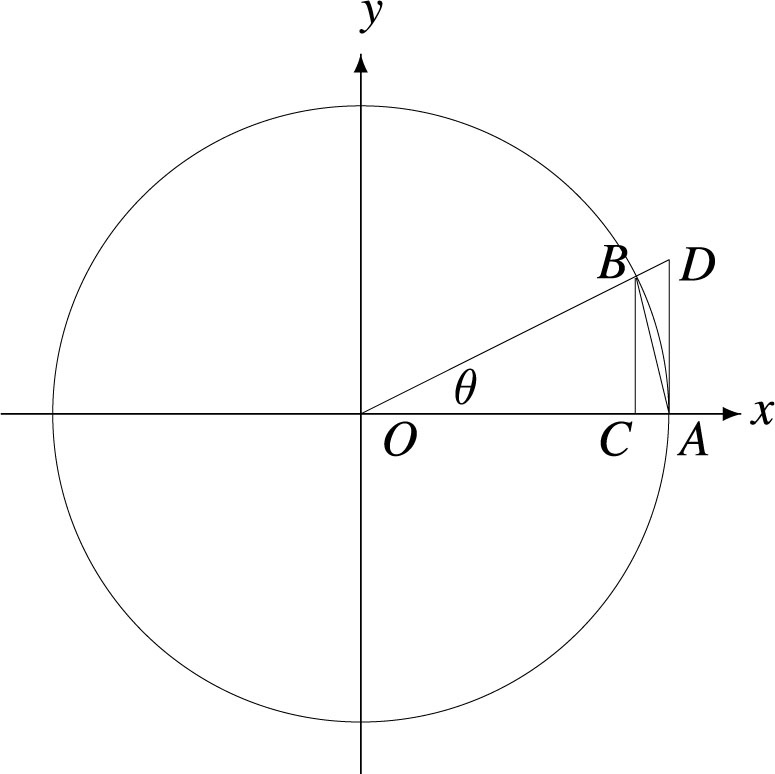

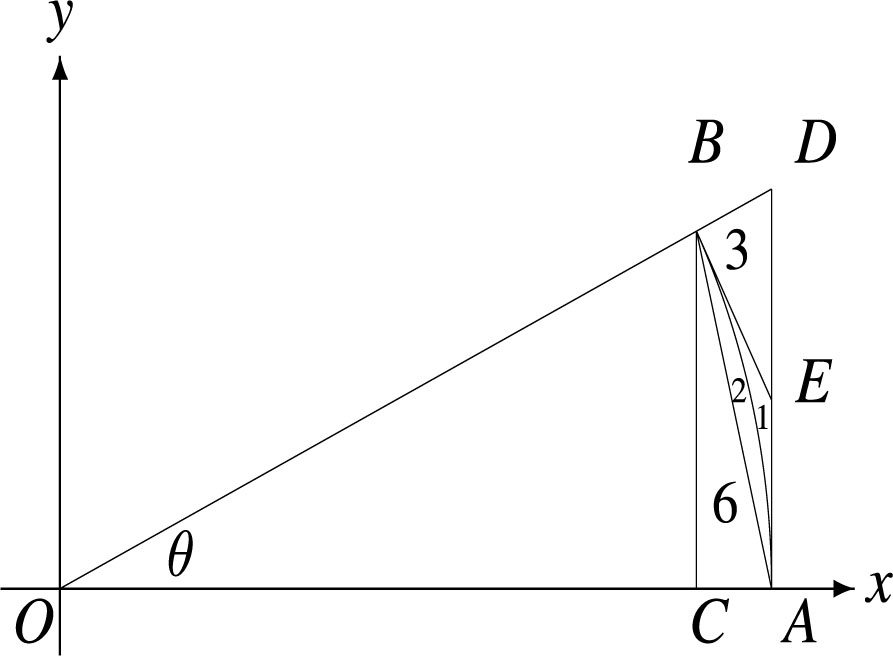

By using the following well-known elementary estimates (which can be derived, for example, by comparing the areas of ΔOAB, sector OAB and ΔOAD, or somewhat differently, by comparing the lengths of BC, arc

Comparison of areas and lengths in a unit circle: The areas of △ OAB, sector OAB, and △ OAD equal

it is easy to see that 𝓢n < π <

it follows that

Moreover, since the function (sin x)/x is monotone decreasing on the interval (0, π/2), the sequence {𝓢n} increases with n. On the other hand, since the function (tan x)/x is monotone increasing for 0 < x < π/2, the sequence {

The following lemma provides some improved higher-order estimates for the sine function and will be useful for deriving error estimates for various approximations of π.

Lemma 2.1

Let θ > 0. Then sin θ < θ,

Note that these inequalities correspond precisely to estimates given by the partial sums of the alternating Taylor series of the sine function. By using sin θ > θ – θ3/6 and sin θ < θ – θ3/6 + θ5/120 for θ > 0, we can establish the following error estimates for 𝓢n = n sin (π/n)

Thus, the approximation error associated with 𝓢n, an under-estimate of π, is slightly less than, but almost precisely π3/(6n2). On the other hand, for the over-estimate of π given by

with the approximation error slightly more than π3/(3n2). In particular, for n = 96, we find 𝓢96 – π ≈ – π3/55296 ≈ –5.6 × 10–4 and

It is interesting to note that, as one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, Archimedes was wise enough to have stopped at n = 96, but instead suggested taking the average of 𝓢96 and

The approximate 1 : 2 : 3 : 6 ratio for the areas of the four small regions in the trapezoid ACBD separated by AB, arc

Thus, even with the modest value of n = 96, this would yield π ≈ 𝓧96 – π5/1698693120 with an approximation error of about 1.8 × 10–7, a historic feat that was first achieved by Chinese mathematician Zu Chongzhi more than 7 centuries later by calculating 𝓢n with n = 212 × 3 = 12, 288!

We conclude this discussion by noting that, based on a similar approximate 1 : 3 ratio between the area bounded by AB and

and further improvements can be obtained by combining 𝓢n,

and in numerous more ways by also utilizing earlier values such as

3 Approximation of π through the semiperimeter or area of a random cyclic n-gon

We now turn to the related but more interesting problem of approximating π through the semiperimeter or area of a randomly selected n-gon inscribed in a unit circle, adding another modern twist to Archimedes’ ancient approach. For definiteness, we assume that the vertices of the n-gon are independently and uniformly distributed on the circle. Our main goal is to show that, as n → ∞, the semiperimeter 𝓢n and area 𝓐n of such a random n-gon each converges to π with probability 1, that is, ℙ(𝓢n → π) = ℙ(𝓐n → π) = 1. This in turn implies convergence of 𝓢n → π and 𝓐n → π in probability and in mean square as well.

Suppose the vertices of such an n-gon are labeled P0, P1, …, Pn–1, Pn in counterclockwise direction with θ0 < θ1 < ⋯ < θn–1 < θn = θ0 + 2π and Pn representing the same point as P0 on the circle. Here θi equals the length of the arc from the fixed reference point (1, 0) to Pi, while θi+1 – θi gives the length of the arc

Note that, since sin θ < θ for all θ > 0, again we have 𝓐n < 𝓢n < π. In fact, we also have 𝓢n ≤ n sin

Before we proceed, we mention that the main difficulty in establishing the convergence of 𝓢n → π or 𝓐n → π as n → ∞ arises from the lack of independence among θi – θi–1 for 1 ≤ i ≤ n (with their sum being 2π). The key to our proof is to use Lemma 2.1 to establish a tight lower bound for 𝔼(𝓢n) and 𝔼(𝓐n) with 𝔼(|𝓢n – π|) → 0 and 𝔼(|𝓐n – π|) → 0 sufficiently fast as n → ∞. In particular, we will exploit the symmetry (all vertices are independent and identically distributed) which implies that all θi – θi–1 are also identically distributed.

Without loss of generality, we assume θ0 = 0. To further simplify the calculations below, we also write θi = 2πXi, 0 ≤ i ≤ n so that 0 = X0 < X1 < X2 < ⋯ < Xn–1 < Xn = 1 corresponds to a random division [4, 5, 6] of the unit interval by n – 1 uniformly distributed random points, with the lengths of the resulting n segments Xi – Xi–1 = (2π)–1 (θi – θi–1) all identically distributed. Since X1 = min {X1, X2, …, Xn–1}, it follows that, for any 0 < x < 1, ℙ (X1 > x) = ℙ(Xi > x for all 1 ≤ i ≤ n – 1) = (1 – x)n–1, and thus the probability density function of X1, and hence of each Xi – Xi–1, is given by f(x) = (n – 1) (1 – x)n–2. Consequently,

In particular, for k = 1, 2, 3, we have

We now turn to estimate 𝔼(|𝓢n – π|). First, by using the inequality sin

With (4), this yields

Thus, by Markov inequality [7, 8], we have, for any ε > 0,

This proves 𝓢n → π in probability as n → ∞. Furthermore, we have

By applying Borel-Cantelli lemma [7, 8], we see that |𝓢n – π| > ε occurs finitely often. This implies 𝓢n → π with probability 1, that is, ℙ(𝓢n → π) = 1. Additionally, since |𝓢n – π| ≤ π, we also have the following mean square convergence of 𝓢n → π as n → ∞:

With slight modifications in the calculations above, we can obtain similar convergence results for 𝓐n:

and for all ε > 0,

Similar to (2), we can further show that, the combination

and for any ε > 0,

Note that while the average approximation error for 𝓨n is now about 120 times that associated with a regular n-gon, it converges to π much faster than 𝓢n and 𝓐n for large n. It should be clear that, with the doubling of the sides of such a random n-gon, further extrapolation improvements may be obtained [9] by combining 𝓢n and 𝓐n with the corresponding semiperimeter and area of a suitably constructed 2n-sided random polygon inscribed in the unit circle. In fact, besides the above mentioned strong convergence results, central limit theorem type (weak) convergence estimates also hold for these random approximations of π [2, 9].

On the other hand, by using (3) and the uniform and absolute convergence of the Taylor series of sine function on the interval [0, 2π] (or tighter estimates described in Section 2), we can obtain

or alternatively, by repeatedly using integration by parts, the following finite sum expression

We mention that, while only random inscribed polygons are considered in this paper, most of our convergence results actually also hold for random circumscribing polygons [10] that are tangent to the circle at each of the prescribed random points. However, unlike the classical Archimedean case, such a circumscribing random polygon is not always well-defined (when all random points fall on a semicircle), and even if it exists, its semiperimeter or area can still be unbounded. Finally, similar convergence results also hold for certain random cyclic polygons whose vertices are no longer independently and uniformly distributed on the circle. We refer to [10, 11] for details.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Professors Robert Mena, Kent Merryfield, Shu Wang and the anonymous referees for carefully reading earlier drafts of the paper and providing helpful comments and suggestions for improving the presentation of the paper. Research is supported in part by NSFC (Grant No.11471028, 11831003), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No.1182004, 1192001, Z180007) and Beijing University of Technology (No. ykj-2018-00110).

References

[1] Beckmann P., A History of π, Fifth edition, 1982, The Golem Press.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Bélisle C., On the polygon generated by n random points on a circle, Statist. Probab. Lett., 81 2011, 236-24210.1016/j.spl.2010.11.012Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Joyce D.C., Survey of extrapolation processes in numerical analysis, SIAM Review, 13 1971, 435-49010.1137/1013092Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Moran P.A.P., The random division of an interval, Suppl. J. Roy. Statist. Soc., 9 1947, 92-9810.2307/2983572Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Darling D.A., On a class of problems related to the random division of an interval, Ann. Math. Statistics, 24 1953, 239-25310.1214/aoms/1177729030Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Pyke R., Spacings, J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B, 27 1965, 395-44910.1111/j.2517-6161.1965.tb00602.xSuche in Google Scholar

[7] Feller W., An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, Vol. II, 1966, Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Chung K.L., A Course in Probability Theory, Third edition, 2001, Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Xu W.-Q., Extrapolation methods for random approximations of π, J. Numer. Math. Stoch., 5 2013, 81-92Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Xu W.-Q., Random circumscribing polygons and approximations of π, Statist. Probab. Lett., 106 2015, 52-5710.1016/j.spl.2015.06.026Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Wang S.S., Xu W.-Q., Random cyclic polygons from Dirichlet distributions and approximations of π, Statist. Probab. Lett., 140 2018, 84-9010.1016/j.spl.2018.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Xu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator of orders less than one

- Centralizers of automorphisms permuting free generators

- Extreme points and support points of conformal mappings

- Arithmetical properties of double Möbius-Bernoulli numbers

- The product of quasi-ideal refined generalised quasi-adequate transversals

- Characterizations of the Solution Sets of Generalized Convex Fuzzy Optimization Problem

- Augmented, free and tensor generalized digroups

- Time-dependent attractor of wave equations with nonlinear damping and linear memory

- A new smoothing method for solving nonlinear complementarity problems

- Almost periodic solution of a discrete competitive system with delays and feedback controls

- On a problem of Hasse and Ramachandra

- Hopf bifurcation and stability in a Beddington-DeAngelis predator-prey model with stage structure for predator and time delay incorporating prey refuge

- A note on the formulas for the Drazin inverse of the sum of two matrices

- Completeness theorem for probability models with finitely many valued measure

- Periodic solution for ϕ-Laplacian neutral differential equation

- Asymptotic orbital shadowing property for diffeomorphisms

- Modular equations of a continued fraction of order six

- Solutions with concentration and cavitation to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the extended Chaplygin gas

- Stability Problems and Analytical Integration for the Clebsch’s System

- Topological Indices of Para-line Graphs of V-Phenylenic Nanostructures

- On split Lie color triple systems

- Triangular Surface Patch Based on Bivariate Meyer-König-Zeller Operator

- Generators for maximal subgroups of Conway group Co1

- Positivity preserving operator splitting nonstandard finite difference methods for SEIR reaction diffusion model

- Characterizations of Convex spaces and Anti-matroids via Derived Operators

- On Partitions and Arf Semigroups

- Arithmetic properties for Andrews’ (48,6)- and (48,18)-singular overpartitions

- A concise proof to the spectral and nuclear norm bounds through tensor partitions

- A categorical approach to abstract convex spaces and interval spaces

- Dynamics of two-species delayed competitive stage-structured model described by differential-difference equations

- Parity results for broken 11-diamond partitions

- A new fourth power mean of two-term exponential sums

- The new operations on complete ideals

- Soft covering based rough graphs and corresponding decision making

- Complete convergence for arrays of ratios of order statistics

- Sufficient and necessary conditions of convergence for ρ͠ mixing random variables

- Attractors of dynamical systems in locally compact spaces

- Random attractors for stochastic retarded strongly damped wave equations with additive noise on bounded domains

- Statistical approximation properties of λ-Bernstein operators based on q-integers

- An investigation of fractional Bagley-Torvik equation

- Pentavalent arc-transitive Cayley graphs on Frobenius groups with soluble vertex stabilizer

- On the hybrid power mean of two kind different trigonometric sums

- Embedding of Supplementary Results in Strong EMT Valuations and Strength

- On Diophantine approximation by unlike powers of primes

- A General Version of the Nullstellensatz for Arbitrary Fields

- A new representation of α-openness, α-continuity, α-irresoluteness, and α-compactness in L-fuzzy pretopological spaces

- Random Polygons and Estimations of π

- The optimal pebbling of spindle graphs

- MBJ-neutrosophic ideals of BCK/BCI-algebras

- A note on the structure of a finite group G having a subgroup H maximal in 〈H, Hg〉

- A fuzzy multi-objective linear programming with interval-typed triangular fuzzy numbers

- Variational-like inequalities for n-dimensional fuzzy-vector-valued functions and fuzzy optimization

- Stability property of the prey free equilibrium point

- Rayleigh-Ritz Majorization Error Bounds for the Linear Response Eigenvalue Problem

- Hyper-Wiener indices of polyphenyl chains and polyphenyl spiders

- Razumikhin-type theorem on time-changed stochastic functional differential equations with Markovian switching

- Fixed Points of Meromorphic Functions and Their Higher Order Differences and Shifts

- Properties and Inference for a New Class of Generalized Rayleigh Distributions with an Application

- Nonfragile observer-based guaranteed cost finite-time control of discrete-time positive impulsive switched systems

- Empirical likelihood confidence regions of the parameters in a partially single-index varying-coefficient model

- Algebraic loop structures on algebra comultiplications

- Two weight estimates for a class of (p, q) type sublinear operators and their commutators

- Dynamic of a nonautonomous two-species impulsive competitive system with infinite delays

- 2-closures of primitive permutation groups of holomorph type

- Monotonicity properties and inequalities related to generalized Grötzsch ring functions

- Variation inequalities related to Schrödinger operators on weighted Morrey spaces

- Research on cooperation strategy between government and green supply chain based on differential game

- Extinction of a two species competitive stage-structured system with the effect of toxic substance and harvesting

- *-Ricci soliton on (κ, μ)′-almost Kenmotsu manifolds

- Some improved bounds on two energy-like invariants of some derived graphs

- Pricing under dynamic risk measures

- Finite groups with star-free noncyclic graphs

- A degree approach to relationship among fuzzy convex structures, fuzzy closure systems and fuzzy Alexandrov topologies

- S-shaped connected component of radial positive solutions for a prescribed mean curvature problem in an annular domain

- On Diophantine equations involving Lucas sequences

- A new way to represent functions as series

- Stability and Hopf bifurcation periodic orbits in delay coupled Lotka-Volterra ring system

- Some remarks on a pair of seemingly unrelated regression models

- Lyapunov stable homoclinic classes for smooth vector fields

- Stabilizers in EQ-algebras

- The properties of solutions for several types of Painlevé equations concerning fixed-points, zeros and poles

- Spectrum perturbations of compact operators in a Banach space

- The non-commuting graph of a non-central hypergroup

- Lie symmetry analysis and conservation law for the equation arising from higher order Broer-Kaup equation

- Positive solutions of the discrete Dirichlet problem involving the mean curvature operator

- Dislocated quasi cone b-metric space over Banach algebra and contraction principles with application to functional equations

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator on the open semi-axis

- Differential polynomials of L-functions with truncated shared values

- Exclusion sets in the S-type eigenvalue localization sets for tensors

- Continuous linear operators on Orlicz-Bochner spaces

- Non-trivial solutions for Schrödinger-Poisson systems involving critical nonlocal term and potential vanishing at infinity

- Characterizations of Benson proper efficiency of set-valued optimization in real linear spaces

- A quantitative obstruction to collapsing surfaces

- Dynamic behaviors of a Lotka-Volterra type predator-prey system with Allee effect on the predator species and density dependent birth rate on the prey species

- Coexistence for a kind of stochastic three-species competitive models

- Algebraic and qualitative remarks about the family yy′ = (αxm+k–1 + βxm–k–1)y + γx2m–2k–1

- On the two-term exponential sums and character sums of polynomials

- F-biharmonic maps into general Riemannian manifolds

- Embeddings of harmonic mixed norm spaces on smoothly bounded domains in ℝn

- Asymptotic behavior for non-autonomous stochastic plate equation on unbounded domains

- Power graphs and exchange property for resolving sets

- On nearly Hurewicz spaces

- Least eigenvalue of the connected graphs whose complements are cacti

- Determinants of two kinds of matrices whose elements involve sine functions

- A characterization of translational hulls of a strongly right type B semigroup

- Common fixed point results for two families of multivalued A–dominated contractive mappings on closed ball with applications

- Lp estimates for maximal functions along surfaces of revolution on product spaces

- Path-induced closure operators on graphs for defining digital Jordan surfaces

- Irreducible modules with highest weight vectors over modular Witt and special Lie superalgebras

- Existence of periodic solutions with prescribed minimal period of a 2nth-order discrete system

- Injective hulls of many-sorted ordered algebras

- Random uniform exponential attractor for stochastic non-autonomous reaction-diffusion equation with multiplicative noise in ℝ3

- Global properties of virus dynamics with B-cell impairment

- The monotonicity of ratios involving arc tangent function with applications

- A family of Cantorvals

- An asymptotic property of branching-type overloaded polling networks

- Almost periodic solutions of a commensalism system with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting on time scales

- Explicit order 3/2 Runge-Kutta method for numerical solutions of stochastic differential equations by using Itô-Taylor expansion

- L-fuzzy ideals and L-fuzzy subalgebras of Novikov algebras

- L-topological-convex spaces generated by L-convex bases

- An optimal fourth-order family of modified Cauchy methods for finding solutions of nonlinear equations and their dynamical behavior

- New error bounds for linear complementarity problems of Σ-SDD matrices and SB-matrices

- Hankel determinant of order three for familiar subsets of analytic functions related with sine function

- On some automorphic properties of Galois traces of class invariants from generalized Weber functions of level 5

- Results on existence for generalized nD Navier-Stokes equations

- Regular Banach space net and abstract-valued Orlicz space of range-varying type

- Some properties of pre-quasi operator ideal of type generalized Cesáro sequence space defined by weighted means

- On a new convergence in topological spaces

- On a fixed point theorem with application to functional equations

- Coupled system of a fractional order differential equations with weighted initial conditions

- Rough quotient in topological rough sets

- Split Hausdorff internal topologies on posets

- A preconditioned AOR iterative scheme for systems of linear equations with L-matrics

- New handy and accurate approximation for the Gaussian integrals with applications to science and engineering

- Special Issue on Graph Theory (GWGT 2019)

- The general position problem and strong resolving graphs

- Connected domination game played on Cartesian products

- On minimum algebraic connectivity of graphs whose complements are bicyclic

- A novel method to construct NSSD molecular graphs

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator of orders less than one

- Centralizers of automorphisms permuting free generators

- Extreme points and support points of conformal mappings

- Arithmetical properties of double Möbius-Bernoulli numbers

- The product of quasi-ideal refined generalised quasi-adequate transversals

- Characterizations of the Solution Sets of Generalized Convex Fuzzy Optimization Problem

- Augmented, free and tensor generalized digroups

- Time-dependent attractor of wave equations with nonlinear damping and linear memory

- A new smoothing method for solving nonlinear complementarity problems

- Almost periodic solution of a discrete competitive system with delays and feedback controls

- On a problem of Hasse and Ramachandra

- Hopf bifurcation and stability in a Beddington-DeAngelis predator-prey model with stage structure for predator and time delay incorporating prey refuge

- A note on the formulas for the Drazin inverse of the sum of two matrices

- Completeness theorem for probability models with finitely many valued measure

- Periodic solution for ϕ-Laplacian neutral differential equation

- Asymptotic orbital shadowing property for diffeomorphisms

- Modular equations of a continued fraction of order six

- Solutions with concentration and cavitation to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the extended Chaplygin gas

- Stability Problems and Analytical Integration for the Clebsch’s System

- Topological Indices of Para-line Graphs of V-Phenylenic Nanostructures

- On split Lie color triple systems

- Triangular Surface Patch Based on Bivariate Meyer-König-Zeller Operator

- Generators for maximal subgroups of Conway group Co1

- Positivity preserving operator splitting nonstandard finite difference methods for SEIR reaction diffusion model

- Characterizations of Convex spaces and Anti-matroids via Derived Operators

- On Partitions and Arf Semigroups

- Arithmetic properties for Andrews’ (48,6)- and (48,18)-singular overpartitions

- A concise proof to the spectral and nuclear norm bounds through tensor partitions

- A categorical approach to abstract convex spaces and interval spaces

- Dynamics of two-species delayed competitive stage-structured model described by differential-difference equations

- Parity results for broken 11-diamond partitions

- A new fourth power mean of two-term exponential sums

- The new operations on complete ideals

- Soft covering based rough graphs and corresponding decision making

- Complete convergence for arrays of ratios of order statistics

- Sufficient and necessary conditions of convergence for ρ͠ mixing random variables

- Attractors of dynamical systems in locally compact spaces

- Random attractors for stochastic retarded strongly damped wave equations with additive noise on bounded domains

- Statistical approximation properties of λ-Bernstein operators based on q-integers

- An investigation of fractional Bagley-Torvik equation

- Pentavalent arc-transitive Cayley graphs on Frobenius groups with soluble vertex stabilizer

- On the hybrid power mean of two kind different trigonometric sums

- Embedding of Supplementary Results in Strong EMT Valuations and Strength

- On Diophantine approximation by unlike powers of primes

- A General Version of the Nullstellensatz for Arbitrary Fields

- A new representation of α-openness, α-continuity, α-irresoluteness, and α-compactness in L-fuzzy pretopological spaces

- Random Polygons and Estimations of π

- The optimal pebbling of spindle graphs

- MBJ-neutrosophic ideals of BCK/BCI-algebras

- A note on the structure of a finite group G having a subgroup H maximal in 〈H, Hg〉

- A fuzzy multi-objective linear programming with interval-typed triangular fuzzy numbers

- Variational-like inequalities for n-dimensional fuzzy-vector-valued functions and fuzzy optimization

- Stability property of the prey free equilibrium point

- Rayleigh-Ritz Majorization Error Bounds for the Linear Response Eigenvalue Problem

- Hyper-Wiener indices of polyphenyl chains and polyphenyl spiders

- Razumikhin-type theorem on time-changed stochastic functional differential equations with Markovian switching

- Fixed Points of Meromorphic Functions and Their Higher Order Differences and Shifts

- Properties and Inference for a New Class of Generalized Rayleigh Distributions with an Application

- Nonfragile observer-based guaranteed cost finite-time control of discrete-time positive impulsive switched systems

- Empirical likelihood confidence regions of the parameters in a partially single-index varying-coefficient model

- Algebraic loop structures on algebra comultiplications

- Two weight estimates for a class of (p, q) type sublinear operators and their commutators

- Dynamic of a nonautonomous two-species impulsive competitive system with infinite delays

- 2-closures of primitive permutation groups of holomorph type

- Monotonicity properties and inequalities related to generalized Grötzsch ring functions

- Variation inequalities related to Schrödinger operators on weighted Morrey spaces

- Research on cooperation strategy between government and green supply chain based on differential game

- Extinction of a two species competitive stage-structured system with the effect of toxic substance and harvesting

- *-Ricci soliton on (κ, μ)′-almost Kenmotsu manifolds

- Some improved bounds on two energy-like invariants of some derived graphs

- Pricing under dynamic risk measures

- Finite groups with star-free noncyclic graphs

- A degree approach to relationship among fuzzy convex structures, fuzzy closure systems and fuzzy Alexandrov topologies

- S-shaped connected component of radial positive solutions for a prescribed mean curvature problem in an annular domain

- On Diophantine equations involving Lucas sequences

- A new way to represent functions as series

- Stability and Hopf bifurcation periodic orbits in delay coupled Lotka-Volterra ring system

- Some remarks on a pair of seemingly unrelated regression models

- Lyapunov stable homoclinic classes for smooth vector fields

- Stabilizers in EQ-algebras

- The properties of solutions for several types of Painlevé equations concerning fixed-points, zeros and poles

- Spectrum perturbations of compact operators in a Banach space

- The non-commuting graph of a non-central hypergroup

- Lie symmetry analysis and conservation law for the equation arising from higher order Broer-Kaup equation

- Positive solutions of the discrete Dirichlet problem involving the mean curvature operator

- Dislocated quasi cone b-metric space over Banach algebra and contraction principles with application to functional equations

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator on the open semi-axis

- Differential polynomials of L-functions with truncated shared values

- Exclusion sets in the S-type eigenvalue localization sets for tensors

- Continuous linear operators on Orlicz-Bochner spaces

- Non-trivial solutions for Schrödinger-Poisson systems involving critical nonlocal term and potential vanishing at infinity

- Characterizations of Benson proper efficiency of set-valued optimization in real linear spaces

- A quantitative obstruction to collapsing surfaces

- Dynamic behaviors of a Lotka-Volterra type predator-prey system with Allee effect on the predator species and density dependent birth rate on the prey species

- Coexistence for a kind of stochastic three-species competitive models

- Algebraic and qualitative remarks about the family yy′ = (αxm+k–1 + βxm–k–1)y + γx2m–2k–1

- On the two-term exponential sums and character sums of polynomials

- F-biharmonic maps into general Riemannian manifolds

- Embeddings of harmonic mixed norm spaces on smoothly bounded domains in ℝn

- Asymptotic behavior for non-autonomous stochastic plate equation on unbounded domains

- Power graphs and exchange property for resolving sets

- On nearly Hurewicz spaces

- Least eigenvalue of the connected graphs whose complements are cacti

- Determinants of two kinds of matrices whose elements involve sine functions

- A characterization of translational hulls of a strongly right type B semigroup

- Common fixed point results for two families of multivalued A–dominated contractive mappings on closed ball with applications

- Lp estimates for maximal functions along surfaces of revolution on product spaces

- Path-induced closure operators on graphs for defining digital Jordan surfaces

- Irreducible modules with highest weight vectors over modular Witt and special Lie superalgebras

- Existence of periodic solutions with prescribed minimal period of a 2nth-order discrete system

- Injective hulls of many-sorted ordered algebras

- Random uniform exponential attractor for stochastic non-autonomous reaction-diffusion equation with multiplicative noise in ℝ3

- Global properties of virus dynamics with B-cell impairment

- The monotonicity of ratios involving arc tangent function with applications

- A family of Cantorvals

- An asymptotic property of branching-type overloaded polling networks

- Almost periodic solutions of a commensalism system with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting on time scales

- Explicit order 3/2 Runge-Kutta method for numerical solutions of stochastic differential equations by using Itô-Taylor expansion

- L-fuzzy ideals and L-fuzzy subalgebras of Novikov algebras

- L-topological-convex spaces generated by L-convex bases

- An optimal fourth-order family of modified Cauchy methods for finding solutions of nonlinear equations and their dynamical behavior

- New error bounds for linear complementarity problems of Σ-SDD matrices and SB-matrices

- Hankel determinant of order three for familiar subsets of analytic functions related with sine function

- On some automorphic properties of Galois traces of class invariants from generalized Weber functions of level 5

- Results on existence for generalized nD Navier-Stokes equations

- Regular Banach space net and abstract-valued Orlicz space of range-varying type

- Some properties of pre-quasi operator ideal of type generalized Cesáro sequence space defined by weighted means

- On a new convergence in topological spaces

- On a fixed point theorem with application to functional equations

- Coupled system of a fractional order differential equations with weighted initial conditions

- Rough quotient in topological rough sets

- Split Hausdorff internal topologies on posets

- A preconditioned AOR iterative scheme for systems of linear equations with L-matrics

- New handy and accurate approximation for the Gaussian integrals with applications to science and engineering

- Special Issue on Graph Theory (GWGT 2019)

- The general position problem and strong resolving graphs

- Connected domination game played on Cartesian products

- On minimum algebraic connectivity of graphs whose complements are bicyclic

- A novel method to construct NSSD molecular graphs