Abstract

The solutions to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the extended Chaplygin gas are constructed for all kinds of situations by using the method of phase plane analysis. The asymptotic limits of solutions to the Riemann problem for the relativistic extended Chaplygin Euler system are investigated in detail when the pressure given by the equation of state of extended Chaplygin gas becomes that of the pressureless gas. During the process of vanishing pressure, the phenomenon of concentration can be identified and analyzed when the two-shock Riemann solution tends to a delta shock wave solution as well as the phenomenon of cavitation also being captured and observed when the two-rarefaction-wave Riemann solution tends to a two-contact-discontinuity solution with a vacuum state between them.

1 Introduction

It is very important to understand the relativistic fluid dynamics in the study of various astrophysical phenomena [1], such as the gravitational collapse, the supernova explosion and the formation and acceleration of the universe. Nowadays, there exists a vast amount of literature in various models of relativistic fluid dynamics since the fundamental work of Taub [2]. However, only a few analytical theories have been developed such as in [3, 4, 5, 6] due to the complicated structures of various relativistic fluid dynamics models. In this present work, we draw our attention on the isentropic Euler system of two conservation laws consisting of energy and momentum in special relativity in the following form [3, 5, 6, 7]

Here the unknown state variables ρ(x, t) and v(x, t) stand for the proper-energy density and the particle speed respectively and the unknown function p(ρ) is used to denote scalar pressure which is a function of ρ for the isentropic situation. In addition, the constant c is the speed of light. The system (1.1) was often used to describe the dynamics of plane waves in special relativistic fluids in the two-dimensional Minkowski space-time [3].

In our present study, the equation of state p(ρ) is chosen as the third-order form of the extended Chaplygin gas [8, 9] as follows:

in which A1, A2, A3 ≥ 0 and B > 0. It requires that the speed of sound

It is well known that the explicit solution can help us to understand the formation mechanism of singularities. For this purpose, we restrict ourselves to consider the system (1.1)-(1.2) with the Riemann-type initial data which is taken to be

Formally, if we adopt the Newtonian limit (namely the limit

which has been widely studied as in [17, 18]. On the other hand, if the limit A1, A2, A3, B → 0 is taken, then the system (1.1)-(1.2) turns out to be the following zero-pressure relativistic Euler system

The system (1.5) is a non-strictly hyperbolic and completely linearly degenerate system, whose elementary wave only involves the contact discontinuity. More specifically, the solution to the Riemann problem (1.3) and (1.5) is either a delta shock wave solution when v– > v+ or a two-contact-discontinuity solution with a vacuum state between them when v– < v+. It is worth mentioning that the evolution of universe is in agreement with the pressureless fluid of the dark matter era at the early stage and subsequently is also consistent with the cosmic fluid to mimic the cosmological constant of the dark energy era at the later stage [14]. Motivated by the above observation, it is of great interest to investigate the transition between the two different stages of the universe by studying the vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) where A1, A2, A3, B → 0 is taken.

The first task of this paper is to solve the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1) associated with the equation of state (1.2). It is easy to get that the system (1.1) associated with (1.2) is strictly hyperbolic and each of the two characteristic fields is genuinely nonlinear. As a consequence, the solutions to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) are four kinds of different combinations between 1-shock (or 1-rarefaction) wave and 2-shock (or 2-rarefaction) wave, which depends on the choice of initial Riemann data (1.3). The second task of this paper is to consider the limits A1, A2, A3, B → 0 of solutions to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) as the pressure tends to zero. Our discussion should be divided into two parts: (1) c > v– > v+ > –c and (2) –c < v– < v+ < c according to the two different structures of the solutions to the Riemann problem (1.3) and (1.5). To be more precise, the phenomenon of concentration can be identified and analyzed for the case c > v– > v+ > –c, where the limit of solution consisting of two shock waves to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) tends to a δ-shock wave solution as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 while the intermediate density between the two shock waves tends to be a weight Dirac δ-measure. In contrast, the phenomenon of cavitation can also be captured and observed for the case –c < v– < v+ < c, where the limit of the solution consisting of two rarefaction waves to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) tends to a two-contact-discontinuity solution with a vacuum state between them as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 while the intermediate density between the two rarefaction waves tends to be zero (namely a vacuum state).

For the related work about the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1), the equation of state p(ρ) = k2ρ was first investigated by Smoller and Temple [3] where the global existence of BV weak solutions to the Cauchy problem for the system (1.1) was proved analytically by employing Glimm’s scheme. Furthermore, the Riemann problem for the system (1.1) with the equation of state given by a smooth function p(ρ) and then the Cauchy problem for the system (1.1) with the equation of state obeying the γ law were also considered in [5]. When the perturbation is arbitrarily large, the uniqueness of Riemann solution to the system (1.1) was established by Chen and Li [6] in the class of entropy solutions in L∞ ∩ BVloc by making use of the detailed analysis of the global behavior of shock wave curves in the half-upper (ρ, v) phase space. Li, Feng and Wang [7] made a step further to construct the global entropy solutions to the Cauchy problem for the system (1.1) with a class of large initial data including the interaction between shock waves and rarefaction waves.

The formation of vacuum state and delta shock wave to the Riemann problem for the zero-pressure gas dynamics system [19, 20] was considered initially for the isothermal case [21] with the equation of state given by p(ρ) = cρ and the isentropic case [22] with the equation of state given by p(ρ) = cργ, 1 < γ < 3 by making use of the vanishing pressure limit approach. The result was further extended to the generalized zero-pressure gas dynamics system in [23]. Also see for the other related works [24, 25, 26, 27] and the references cited therein. It is worthwhile to notice that the limits of solutions to the Riemann problems from the various isentropic Chaplygin gas dynamic systems [28, 29, 30, 31, 32] to the zero-pressure gas dynamic system have also been widely investigated in a variety of contents [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38], which are not described in detail any more in the paper.

As for the formation of vacuum state and delta shock wave to the Riemann problem for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5), Yin and Sheng first investigated the vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the Riemann problems about the Euler system of conservation laws consisting of energy and momentum in special relativity for the isothermal [39] and isentropic [40] situations, in which the phenomena of concentration and cavitation can be observed and analyzed in detail. Subsequently, Li and Shao [41] considered the vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the generalized Chaplygin gas where Ai = 0 (i = 1, 2, 3) was taken in (1.2), in which the delta shock wave was also involved in the solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) for the generalized Chaplygin gas when Ai = 0 (i = 1, 2, 3) in (1.2). Yin and Sheng [42] made a step further to generalize the above results to the Euler system consisting of three conservation laws to describe baryon numbers, energy and momentum in special relativity. Furthermore, Yin and Song [43] considered the vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the Riemann problems about the Euler system of conservation laws consisting of baryon numbers and momentum in special relativity for the Chaplygin gas. In addition, Yang and Zhang [44] introduced the flux approximation approach to study the formation of vacuum state and delta shock wave to the Riemann problem for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5).

The paper is arranged as follows. In Section 2, we are mainly concerned with the construction of solutions to the Riemann problems for the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1) associated with the equation of state (1.2) in detail. In addition, we give a brief description of the solutions to the Riemann problem for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5). In Section 3, we shall focus on the vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the Riemann problems from the system (1.1)-(1.2) to the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5) for the case c > v– > v+ > –c when the limit A1, A2, A3, B → 0 is taken, in which the formation of δ-shock wave can be observed and analyzed. In Section 4, we turn back to investigate the formation of vacuum state for the case –c < v– < v+ < c when the limit A1, A2, A3, B → 0 is taken.

2 The Riemann problems for the isentropic and zero-pressure relativistic Euler systems

In this section, we first illustrate the solutions to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1) associated with the equation of state (1.2). Then, we recollect the related results for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5), whose Riemann solution is a delta shock wave solution when c > v– > v+ > –c or a two-contact-discontinuity solution with a vacuum state between them when –c < v– < v+ < c.

2.1 The Riemann problem for the system (1.1) with the equation of state (1.2)

In this subsection, we shall first analyze the properties of elementary waves and then construct the solutions to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) for all kinds of situations. Since the speed of sound

In fact, the above ρ1 and ρ2 can be calculated numerically when all the coefficients A1, A2, A3, B and α are given. More precisely, we can estimate ρ1 and ρ2 simply for sufficiently small A1, A2, A3, B. It can be concluded that the following two inequalities

hold simultaneously, which enables us to have at least

Thus, the physically relevant region of solutions for the fixed A1, A2, A3, B is restricted to

In addition, it is easy to know from (2.1) that

The system (1.1)-(1.2) can be rewritten in the following quasi-linear form

where the matrixes C and D are given respectively by

and

By means of a direct calculation, we can achieve two real and distinct eigenvalues

Corresponding to each λi(i = 1, 2), the right eigenvectors are calculated respectively by

Thus the system (1.1)-(1.2) is strictly hyperbolic [3, 6, 46]. Let us introduce the notion

and

As a consequence, the following can be obtained

in which

Both the characteristic fields of λ1 and λ2 are genuinely nonlinear. That being said, we shall show that the elementary waves for each of the two characteristic fields are either rarefaction waves or shock waves [3, 6, 46].

Let us first consider the rarefaction wave curves. Both the system (1.1)-(1.2) and the Riemann initial data (1.3) are unchanged under the scalable coordinates: (x, t) → (kx, kt)(k > 0 is a constant). Therefore, we want to solve the self-similar solutions of the form

Now, we can use the following boundary value problems of ordinary differential equations to take the place of the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) as follows:

For smooth solutions, (2.11) is reduced to

where

If (dρ, dv) = (0, 0), then it is easy to get the trivial solution that (ρ, v) is a constant state. Otherwise, if (dρ, dv) ≠ (0, 0), by a trivial and tedious calculation, then we can obtain the singular solutions

and

One can obtain ρ1 < ρ < ρ– < ρ2 directly from the requirement λ1(ρ) > λ1(ρ–). Let the left state (ρ–, v–) be fixed, then integrating the second equation in (2.13) from ρ– to ρ enables us to obtain the 1-rarefaction wave curve

By virtue of a straight-forward computation, it is easy to find

By a direct calculation, we find

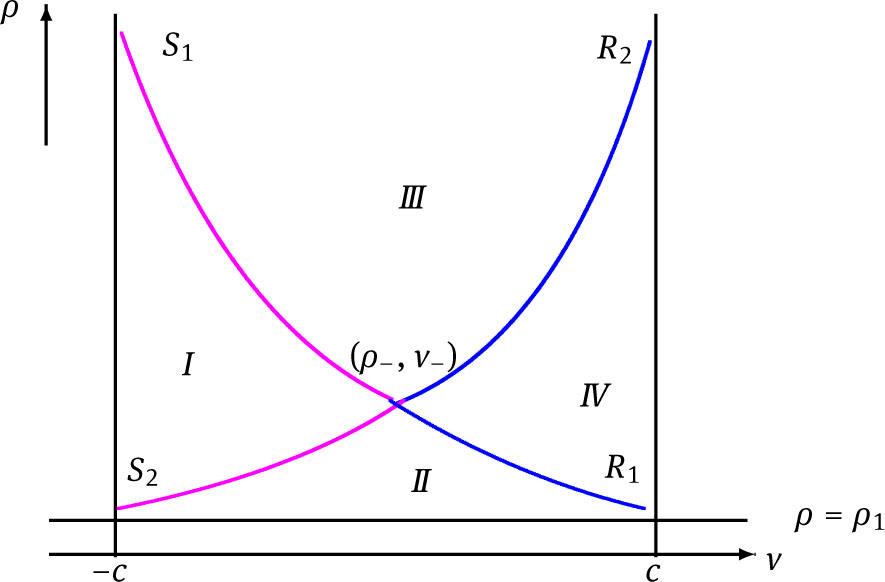

For the 1-rarefaction wave, owing to a tedious but straightforward calculation for the second equation of (2.13), we have vρρ > 0 for all the ρ1 < ρ < ρ2. In other words, the 1-rarefaction wave curve R1 is convex in the half-upper (ρ, v) phase plane. Analogously, we can also have vρρ < 0 for all the ρ1 < ρ < ρ2 from the second equation in (2.14). That is to say, the 2-rarefaction wave curve R2 is concave in the half-upper (ρ, v) phase plane.

From now on, we focus our attention on the shock wave curves. The Rankine-Hugoniot conditions are as follows

where [ρ] = ρ – ρ– denotes the jump across the discontinuity. We call σ the speed of the discontinuity, where

From direct calculation and simplification, (2.18) turns out to be

For the sake of simplicity, we set

As a consequence, (2.19) further reduces to

To sum up for the given left state (ρ–, v–), the two shock waves are shown respectively as

and

From either (2.22) or (2.23), a tedious but straightforward computation shows that

where

It is easy to see that vρ < 0 from ρ2 > ρ > ρ– > ρ1 for the 1-shock curve and vρ > 0 from ρ1 < ρ < ρ– < ρ2 for the 2-shock curve. It follows that v decreases as ρ increases for the curve S1(ρ–, v–) while v increases as ρ increases for the curve S2(ρ–, v–). Comparing with the 1-rarefaction (or 2-rarefaction) curve, similar convexity (or concavity) are to be found in the 1-shock (or 2-shock) curve. The computation is tedious and trivial and thus the details are omitted here.

By combining (2.15), (2.16), (2.22) and (2.23), it is clear that the elementary wave curves R1(ρ–, v–), R2(ρ–, v–), S1(ρ–, v–) and S2(ρ–, v–) emanating from the fixed left state (ρ–, v–) divide the half-upper (ρ, v) phase plane into four regions I, II, III and IV (see Fig.1). Let (ρ–, v–) be fixed, then the solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) is determined uniquely by the above four regions. More precisely, the solution can be expressed as S1 + S2 when (ρ+, v+) ∈ I, R1 + S2 when (ρ+, v+) ∈ II, S1 + R2 when (ρ+, v+) ∈ III or R1 + R2 when (ρ+, v+) ∈ IV respectively. Here and in what follows, the symbol S1 + S2 is adopted to represent a 1-shock wave S1 followed by a 2-shock wave S2, etc.

2.2 The Riemann problem for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5)

In this subsection, we shall briefly summarize the solutions to the Riemann problem for the zero-pressure relativistic Euler system (1.5), which have been well described such as in [39, 40]. The system (1.5) has the two coincident eigenvalues λ1 = λ2 = v, which means that the system (1.5) is non-strictly hyperbolic. The corresponding right eigenvector is

As before, if we look for the self-similar solution (ρ, v)(x, t) = (ρ, v)(ξ), ξ =

In the case v– < v+, the solutions (ρ, v)(ξ) including two contact discontinuities with a vacuum state between them can be written as

Otherwise, in the case v– > v+, a delta shock wave solution is generated due to the overlapping characteristics for the Riemann problem (1.3) and (1.5). It is necessary to introduce the definition of δ–measure [19, 22, 45] in order to depict the delta shock wave solution to the Riemann problem (1.3) and (1.5).

Definition 2.1

Let Γ = {(x(s), t(s)) : a < s < b} be a parameterized smooth curve, then a two-dimensional weighted Dirac delta function ω(t)δΓ with the support on Γ being defined as

for any test function φ(x, t) ∈

For the purpose of completeness, it is necessary to offer the following generalized definition of delta shock wave solution introduced by Danilov et al. [47, 48, 49, 50]. Let I be a finite index set, then we make the assumption that Γ = {γi|i ∈ I} is a graph in the upper-half plane (x, t) ∈ R × R+ involving Lipschitz continuous curves γi for i ∈ I. Later, let I0 be a subset of I, then the curves γi with i ∈ I0 originate from the x–axis. In the end, let

Definition 2.22

Consider the δ-measure type initial data

where ρ̂0, v0 ∈ L∞(R). Then, a pair of distributions (ρ, v) is called a δ–shock wave type solution for the system (1.5) with the initial data (2.29) if and only if the following integral identities

hold for any test function φ ∈

It is clear to see that the Riemann initial data (1.3) is the simplest example of the δ-measure type initial data (2.29) that the graph contains only one arc and the initial strength of δ-measure is zero. In consideration of Definitions 2.1 and 2.2, if v– > v+, then a delta shock wave solution to the Riemann problem (1.3) and (1.5) can be provided in the following form [39, 40]

where

Moreover, the delta shock wave solution (2.32) in comparison with (2.33) obeys the generalized Rankine-Hugoniot conditions listed below

In order to guarantee the uniqueness of solution, it should also obey the over-compressive δ-entropy condition

In addition, the above-constructed delta shock wave solution (2.32) in comparison with (2.33) is satisfied with the system (1.5) in the sense of distributions. In other words, the weak form of the system (1.5) as below

holds for any test function ϕ(x, t) ∈

Here, we have used ρ0 = ρ– + (ρ+ – ρ–)H(x – σt) and v0 = v– + (v+ – v–)H(x – σt), in which H is the Heaviside function. In fact, the generalized Rankine-Hugoniot conditions (2.34) can be derived directly from (2.36) together with (2.37) and (2.38). The process of derivation is completely similar to that for the zero-pressure Euler system in [19], thus the details are omitted here. As a consequence, the existence and uniqueness of delta shock wave solution in the form (2.32) can be checked as in [44] by using the generalized Rankine-Hugoniot conditions (2.34) together with the over-compressive δ-entropy condition (2.35).

It is remarkable that the delta shock wave solution (2.32) together with (2.33) are no longer in the space of BV or L∞ functions. However, the divergences of certain entropy and entropy flux fields are still in the space of Radon measures [22]. It is natural to discuss this problem in the theory of divergence-measure fields and thus the delta shock wave solution (2.32) together with (2.33) can be understood in the form of Tartar-Murat measure solution [51, 52, 53], in which the velocity must take a value at the point of the jump.

3 The formation of delta shock wave as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 when v– > v+

It is easy to know from [22, 26] that if v– > v+, then the solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) consists of two shock waves for sufficiently small positive numbers A1, A2, A3 and B. In this section, we are mainly concerned with the formation of delta shock wave solution from the two-shock Riemann solution to the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1) associated with the equation of state (1.2) as A1, A2, A3 and B tend to zero when the requirements c > v– > v+ > –c and ρ1 < ρ± < ρ2 are satisfied in the Riemann initial data (1.3).

Let (ρ*, v*) be the intermediate state between two shock waves, we obtain the solution which joins (ρ–, v–) and (ρ*, v*) by means of the 1-shock wave S1 with the speed σ1 and then joins (ρ*, v*) and (ρ+, v+) by means of the 2-shock wave S2 with the speed σ2. To be more specific, we have

and

Then, the two second equations in (3.1) and (3.2) can be combined into

In what follows, we shall give some lemmas which are related to the limiting behavior of the solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) as A1, A2, A3 and B →0 when c > v– > v+ > –c.

Lemma 3.1

We can establish the limiting relations

Furthermore, we also have

Proof

Without loss of generality, we suppose

Let

As a result, (3.3) takes the following form

which enables us to have

Then (3.8) reduces to

Furthermore, we have

Squaring both sides of (3.10) and then simplifying, yields

namely

This is a quadratic form of M and can be solved as

Thus, one has

If the negative sign in (3.13) is chosen, then one has

Analogously, one also has

Let v− and v+ be fixed to satisfy c > v− > v+ > −c, then it is easy to know that we can choose ρ− and ρ+ suitably to satisfy either

or

If the Riemann initial data (1.3) satisfy c > v− > v+ > −c and (3.16) at the same time, then we have

which means that (3.7) is not satisfied. Similarly, if the Riemann initial data (1.3) satisfy c > v− > v+ > −c and (3.17) at the same time, then we can also see that (3.7) is still not satisfied. As a consequence, it can be concluded from the above discussion that the negative sign cannot be chosen in (3.13) for the reason that (3.7) does not always hold for any given Riemann initial data (1.3) satisfying c > v− > v+ > −c.

On the other hand, if we choose the positive sign in (3.13), then it yields

and

Thus, it is easy to get

which enables us to see that (3.7) is indeed satisfied. In a word, it can be concluded from the above discussion that

As a consequence, the limiting relation (3.4) can be established.

It is deduced from (3.1) that

such that we have

Substituting (3.6) and (3.20) into (3.22) leads to

On the one hand, it can be clearly seen that

Taking into account

On the other hand, it is easy to see that

Analogously, we have

The proof is completed. □

Lemma 3.2

The limiting relations of mass and momentum between the two shock waves as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 can be established as follows:

in which the jump of ρ is given by [ρ] = ρ+ − ρ−, etc.

Proof

We turn back to consider the Rankine-Hugoniot conditions (2.17). Carrying out the two shock waves S1 and S2 in the first equation of (2.17), one has

which brings about

Then, using the similar way to deal with the second equation of (2.17), one also has

which gives rise to

As a consequence, the limiting relations (3.28) and (3.29) can be established directly from (3.31) and (3.33). □

Theorem 3.3

When −c < v+ < v− < c, let us suppose that (ρ(ξ), v(ξ)) is a two-shock-wave solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) for sufficiently small A1, A2, A3, B, then the limit of solution as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 converges to the δ-shock wave solution (2.32) linked with (2.33) in the sense of distributions, which is identical with that for the pressureless relativistic Euler system (1.5). Besides, the limits of momentums

respectively.

Proof

Given

which should satisfy the following weak forms

and

for any ϕ(ξ) ∈

Splitting the first integral in (3.35), yields

To sum up the first and last terms of (3.37), we obtain

with

where H(ξ) is the normal Heaviside function. For the second part of (3.37), based on Lemma 3.1, we obtain

in which we have used ϕ(ξ) ∈

Moreover, the third and fourth integrals in (3.35) can be split into

and

respectively. By substituting (3.38)-(3.41) into (3.35), it follows that

On the other hand, if the integral equation (3.36) is carried out in the same way as before, then

In the end, we are concerned with the limits of

According to Definition 2.1, the last part of (3.44) is equivalent to 〈ω1(t)δs, ψ(⋅,⋅)〉, in which

In the same way as before, from (3.43), we also obtain

in which

Thus, the conclusion of Theorem 3.3 can be drawn. □

4 The formation of vacuum state as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 when v− < v+

In this section, let us consider the situation −c < v− < v+ < c where the formation of vacuum state from the two-rarefaction Riemann solution to the isentropic relativistic Euler system (1.1) associated with the equation of state (1.2) as A1, A2, A3 and B tend to zero when −c < v− < v+ < c is satisfied in the Riemann initial data (1.3). It is easy to obtain from [22, 26] that the solution of the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) includes two rarefaction waves for sufficiently small positive numbers A1, A2, A3 and B when −c < v− < v+ < c. Let (ρ*, v*) be the intermediate state between the two rarefaction waves, then we can get the 1-rarefaction wave R1 connecting (ρ−, v−) and (ρ*, v*) as well as the 2-rarefaction wave R2 connecting (ρ*, v*) and (ρ+, v+). To be more specific, it can be deduced from (2.15) and (2.16) that

and

Theorem 4.1

When −c < v− < v+ < c, let us suppose that (ρ(ξ), v(ξ)) is a two-rarefaction-wave solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) for sufficiently small A1, A2, A3, B, then the limit of solution to the Riemann problem (1.1)-(1.3) as A1, A2, A3, B → 0 is a two-contact-discontinuity solution with a vacuum state between them in the form (2.27), which is identical with that for the pressureless relativistic Euler system (1.5).

Proof

Taking into account (4.1) and (4.2), we obtain

where ρ* ≤ min(ρ−, ρ+). Thus, it is easy to get that

If we suppose that

Moreover, it is worthwhile to notice that the rarefaction curves R1 and R2 turn out to be the lines of contact discontinuities J1 : v = v− and J2 : v = v+ in the half-upper (ρ, v) phase plane respectively. Therefore, we take a step further to get

It is obvious to see that the rarefaction curves R1 and R2 tend to the contact discontinuities J1 and J2 with the speeds of v− and v+ respectively. The proof is accomplished. □

Acknowledgement

This work is partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (11271176) and STPF of Shandong Province (J17KA161).

References

[1] Anile A., Relativistic Fluids and Magneto-Fluids: with Applications in Astrophysics and Plasma Physics, Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989.10.1017/CBO9780511564130Search in Google Scholar

[2] Taub A.H., Relativistic Rankine-Hugoniot equations, Phys. Rev., 1948, 74, 328-334.10.1103/PhysRev.74.328Search in Google Scholar

[3] Smoller J., Temple B., Global solutions of the relativistic Euler equations, Commun. Math. Phys., 1993, 156, 67-99.10.1007/BF02096733Search in Google Scholar

[4] Marti J.M., Muller E., The analytical solution of the Riemann problem in relativistic hydrodynamics, J. Fluid Mech., 1994, 258, 317-333.10.1017/S0022112094003344Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chen J., Conservation laws for the relativistic p-system, Commun. Partial Differential Equations, 1995, 20, 1605-1646.10.1080/03605309508821145Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chen G., Li Y., Stability of Remiann solutions with large oscillation for the relativistic Euler equations, J. Differential Equations, 2004, 202, 332-353.10.1016/j.jde.2004.02.009Search in Google Scholar

[7] Li Y., Feng D., Wang Z., Global entropy solutions to the relativistic Euler equations for a class of large initial data, Z. Angew. Math. Phys., 2005, 56, 239-253.10.1007/s00033-005-4118-2Search in Google Scholar

[8] Pourhassan B., Kahya E.O., Extended Chaplygin gas model, Results in Physics, 2014, 4, 101-102.10.1016/j.rinp.2014.05.007Search in Google Scholar

[9] Pourhassan B., Extended Chaplygin gas in Horava-Lifshitz gravity, Physics of the Dark Universe, 2016, 13, 132-138.10.1016/j.dark.2016.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[10] Chaplygin S., On gas jets, Sci. Mem. Moscow Univ. Math. Phys., 1904, 21, 1-121.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bento M.C., Bertolami O., Sen A.A., Generalized Chaplygin gas, accelerated expansion, and dark-energy-matter unification, Phys. Rev. D, 2002, 66, Article ID 043507.10.1103/PhysRevD.66.043507Search in Google Scholar

[12] Bilic N., Tupper G.B., Viollier R.D., Unification of dark matter and dark energy: the inhomogeneous Chaplygin gas, Physics Letters B, 2012, 535, 17-21.10.1016/S0370-2693(02)01716-1Search in Google Scholar

[13] Debnath U., Banerjee A., Chakraborty S., Role of modified Chaplygin gas in accelerated universe, Classical Quantum Gravity, 2004, 21, 5609-5618.10.1088/0264-9381/21/23/019Search in Google Scholar

[14] Heydarzade Y., Darabi F., Atazadeh K., Einstein static universe on the brane supported by extended Chaplygin gas, Astrophys Space Sci, 2016, 361, Article ID 250.10.1007/s10509-016-2836-7Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kahya E.O., Khurshudyan M., Pourhassan B., Myzakulov R., Pasqua A., Higher order corrections of the extended Chaplygin gas cosmology with varying G and Λ, Eur.Phys.J.C, 2015, 75, Article ID 43.10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3263-6Search in Google Scholar

[16] Paul B.C., Thakur P., Saha A., Observational constraints on extended Chaplygin gas cosmologies, Pramana J. Phys.,2017, 89, Article ID 29.10.1007/s12043-017-1417-9Search in Google Scholar

[17] Geng Y., Li Y., Non-relativistic global limits of entropy solutions to the extremely relativistic Euler equations, Z.Angew. Math. Phys., 2010, 61, 201-220.10.1007/s00033-009-0031-1Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ding M., Li Y., Non-relativistic limits of rarefaction wave to the 1-D piston problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler equations, J. Math. Phys., 2017, 58, Article ID 081510.10.1063/1.4997873Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sheng W, Zhang T., The Riemann problem for the transportation equations in gas dynamics, Mem.Amer.Math.Soc., 1999, 137, Article ID N654.10.1090/memo/0654Search in Google Scholar

[20] Shen C., Sun M., A distributional product approach to the delta shock wave solution for the one-dimensional zero-pressure gas dynamics system, International Journal of Non-linear Mechanics, 2018, 105, 105-112.10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2018.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li J., Note on the compressible Euler equations with zero temperature, Appl. Math. Lett., 2001, 14, 519-523.10.1016/S0893-9659(00)00187-7Search in Google Scholar

[22] Chen G., Liu H., Formation of Delta-shocks and vacuum states in the vanishing pressure limit of solutions to the isentropic Euler equations, SIAM J. Math.Anal., 2003, 34, 925-938.10.1137/S0036141001399350Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mitrovic D., Nedeljkov M., Delta-shock waves as a limit of shock waves, J. Hyperbolic Differential Equations, 2007, 4, 629-653.10.1142/S021989160700129XSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Chen G., Liu H., Concentration and cavitation in the vanishing pressure limit of solutions to the Euler equations for nonisentropic fluids, Phys. D, 2004, 189, 141-165.10.1016/j.physd.2003.09.039Search in Google Scholar

[25] Shen C., The limits of Riemann solutions to the isentropic magnetogasdynamics, Appl.Math.Lett., 2011, 24, 1124-1129.10.1016/j.aml.2011.01.038Search in Google Scholar

[26] Shen C., Sun M., Formation of delta shocks and vacuum states in the vanishing pressure limit of Riemann solutions to the perturbed Aw-Rascle model, J. Differential Equations, 2010, 249, 3024-3051.10.1016/j.jde.2010.09.004Search in Google Scholar

[27] Sun M., The limits of Riemann solutions to the simplified pressureless Euler system with flux approximation, Math. Methods Appl.Sci., 2018, 41, 4528-4548.10.1002/mma.4912Search in Google Scholar

[28] Wang G., The Remiann problem for one dimensional generalized Chaplygin gas dynamics, J. Math. Anal. Appl., 2013, 403, 434-450.10.1016/j.jmaa.2013.02.026Search in Google Scholar

[29] Shen C., The Riemann problem for the Chaplygin gas equations with a source term, Z. Angew. Math. Mech., 2016, 96, 681-695.10.1002/zamm.201500015Search in Google Scholar

[30] Nedeljkov M., Higher order shadow waves and delta shock blow up in the Chaplygin gas, J. Differential Equations, 2014, 256, 3859-3887.10.1016/j.jde.2014.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[31] Nedeljkov M., Ruzicic S., On the uniqueness of solution to generalized Chaplygin gas, Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., 2017, 37, 4439-4460.10.3934/dcds.2017190Search in Google Scholar

[32] Pang Y., Delta shock wave in the compressible Euler equations for a Chaplygin gas, J. Math. Anal. Appl., 2017, 448, 245-261.10.1016/j.jmaa.2016.10.078Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sheng W., Wang G., Yin G., Delta wave and vacuum state for generalized Chaplygin gas dynamics system as pressure vanishes, Nonlinear Anal. RWA, 2015, 22, 115-128.10.1016/j.nonrwa.2014.08.007Search in Google Scholar

[34] Chen J., Sheng W., The Riemann problem and the limit solutions as magnetic field vanishes to magnetogasdynamics for generalized Chaplygin gas, Commun. Pure Appl. Anal., 2018, 17, 127-142.10.3934/cpaa.2018008Search in Google Scholar

[35] Yang H., Wang J., Concentration in vanishing pressure limit of solutions to the modified Chaplygin gas equations, J. Math. Phys., 2016, 57, Article ID 111504.10.1063/1.4967299Search in Google Scholar

[36] Guo L., Li T., Yin G., The vanishing pressure limits of Riemann solutions to the Chaplygin gas equations with a source term, Commun. Pure Appl. Anal., 2017, 16, 295-309.10.3934/cpaa.2017014Search in Google Scholar

[37] Guo L., Li T., Yin G., The limit behavior of the Riemann solutions to the generalized Chaplygin gas equations with a source term, J. Math. Anal. Appl., 2017, 455, 127-140.10.1016/j.jmaa.2017.05.048Search in Google Scholar

[38] Tong M., Shen C., Lin X., The asymptotic limits of Riemann solutions for the isentropic extended Chaplygin gas dynamic system with the vanishing pressure, Boundary Value Problems, 2018, 2018, Article ID 144.10.1186/s13661-018-1064-1Search in Google Scholar

[39] Yin G., Sheng W., Delta shocks and vacuum states in vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the relativistic Euler equations, Chinese Annals of Mathematics, Series B, 2009, 29, 611-622.10.1007/s11401-008-0009-xSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Yin G., Sheng W., Delta shocks and vacuum states in vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the relativistic Euler equations for the polytropic gases, J. Math. Anal. Appl., 2009, 335, 594-605.10.1016/j.jmaa.2009.01.075Search in Google Scholar

[41] Li H., Shao Z., Delta shocks and vacuum states in vanishing pressure limits of solutions to the relativistic Euler equations for generalized Chaplygin gas, Commun. Pure Appl. Anal., 2016, 15, 2373-2400.10.3934/cpaa.2016041Search in Google Scholar

[42] Yin G., Sheng W., Delta wave formation and vacuum state in vanishing pressure limit for system of conservation laws to relativistic fluid dynamics, Z.Angew. Math. Mech., 2015, 95, 49-65.10.1002/zamm.201200148Search in Google Scholar

[43] Yin G., Song K., Vanishing pressure limits of Riemann solutions to the isentropic relativistic Euler system for Chaplygin gas, J. Math. Anal. Appl., 2014, 411, 506-521.10.1016/j.jmaa.2013.09.050Search in Google Scholar

[44] Yang H., Zhang Y., Flux approximation to the isentropic relativistic Euler equations, Nonlinear Anal. TMA, 2016, 133, 200-227.10.1016/j.na.2015.12.002Search in Google Scholar

[45] Sun M., Singular solutions to the Riemann problem for a macroscopic production model, Z.Angew. Math. Mech., 2017, 97, 916-931.10.1002/zamm.201600171Search in Google Scholar

[46] Xu Y., Wang L., Breakdown of classical solutions to Cauchy problem for inhomogeneous quasilinear hyperbolic systems, Indian J. Pure Appl. Math., 2015, 46, 827-851.10.1007/s13226-015-0156-1Search in Google Scholar

[47] Danilov V.G., Shelkovich V.M., Dynamics of propagation and interaction of δ-shock waves in conservation law systems, J. Differential Equations, 2005, 211, 333-381.10.1016/j.jde.2004.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[48] Danilov V.G., Mitrovic D., Delta shock wave formation in the case of triangular hyperbolic system of conservation laws, J.Differential Equations, 2008, 245, 3704-3734.10.1016/j.jde.2008.03.006Search in Google Scholar

[49] Danilov V.G., Nonsmooth nonoscillating exponential-type asymptotics for linear parabolic PDE, SIAM J. Math. Anal., 2017, 49, 3550-3572.10.1137/15M1053311Search in Google Scholar

[50] Kalisch H., Mitrovic D., Singular solutions of a fully nonlinear 2×2 system of conservation laws, Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society, 2012, 55, 711-729.10.1017/S0013091512000065Search in Google Scholar

[51] Tartar L., Compensated compactness and applications to partial differential equations, in Res. Notes in Math., Vol.39: Nonlinear Analysis and Mechanics: Heriot-Watt Symposium, Vol. IV, Pitman, Boston, MA, 1979, 136-212.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Murat F., Compacit par compensation, Ann. Scuola Norm. Sup. Pisa Cl. Sci., 1978, 5, 489-507.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Panov E.Yu., Long time asymptotics of periodic generalized entropy solutions of scalar conservation laws, Mathematical Notes, 2016, 100, 113-122.10.1134/S0001434616070105Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Zhang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator of orders less than one

- Centralizers of automorphisms permuting free generators

- Extreme points and support points of conformal mappings

- Arithmetical properties of double Möbius-Bernoulli numbers

- The product of quasi-ideal refined generalised quasi-adequate transversals

- Characterizations of the Solution Sets of Generalized Convex Fuzzy Optimization Problem

- Augmented, free and tensor generalized digroups

- Time-dependent attractor of wave equations with nonlinear damping and linear memory

- A new smoothing method for solving nonlinear complementarity problems

- Almost periodic solution of a discrete competitive system with delays and feedback controls

- On a problem of Hasse and Ramachandra

- Hopf bifurcation and stability in a Beddington-DeAngelis predator-prey model with stage structure for predator and time delay incorporating prey refuge

- A note on the formulas for the Drazin inverse of the sum of two matrices

- Completeness theorem for probability models with finitely many valued measure

- Periodic solution for ϕ-Laplacian neutral differential equation

- Asymptotic orbital shadowing property for diffeomorphisms

- Modular equations of a continued fraction of order six

- Solutions with concentration and cavitation to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the extended Chaplygin gas

- Stability Problems and Analytical Integration for the Clebsch’s System

- Topological Indices of Para-line Graphs of V-Phenylenic Nanostructures

- On split Lie color triple systems

- Triangular Surface Patch Based on Bivariate Meyer-König-Zeller Operator

- Generators for maximal subgroups of Conway group Co1

- Positivity preserving operator splitting nonstandard finite difference methods for SEIR reaction diffusion model

- Characterizations of Convex spaces and Anti-matroids via Derived Operators

- On Partitions and Arf Semigroups

- Arithmetic properties for Andrews’ (48,6)- and (48,18)-singular overpartitions

- A concise proof to the spectral and nuclear norm bounds through tensor partitions

- A categorical approach to abstract convex spaces and interval spaces

- Dynamics of two-species delayed competitive stage-structured model described by differential-difference equations

- Parity results for broken 11-diamond partitions

- A new fourth power mean of two-term exponential sums

- The new operations on complete ideals

- Soft covering based rough graphs and corresponding decision making

- Complete convergence for arrays of ratios of order statistics

- Sufficient and necessary conditions of convergence for ρ͠ mixing random variables

- Attractors of dynamical systems in locally compact spaces

- Random attractors for stochastic retarded strongly damped wave equations with additive noise on bounded domains

- Statistical approximation properties of λ-Bernstein operators based on q-integers

- An investigation of fractional Bagley-Torvik equation

- Pentavalent arc-transitive Cayley graphs on Frobenius groups with soluble vertex stabilizer

- On the hybrid power mean of two kind different trigonometric sums

- Embedding of Supplementary Results in Strong EMT Valuations and Strength

- On Diophantine approximation by unlike powers of primes

- A General Version of the Nullstellensatz for Arbitrary Fields

- A new representation of α-openness, α-continuity, α-irresoluteness, and α-compactness in L-fuzzy pretopological spaces

- Random Polygons and Estimations of π

- The optimal pebbling of spindle graphs

- MBJ-neutrosophic ideals of BCK/BCI-algebras

- A note on the structure of a finite group G having a subgroup H maximal in 〈H, Hg〉

- A fuzzy multi-objective linear programming with interval-typed triangular fuzzy numbers

- Variational-like inequalities for n-dimensional fuzzy-vector-valued functions and fuzzy optimization

- Stability property of the prey free equilibrium point

- Rayleigh-Ritz Majorization Error Bounds for the Linear Response Eigenvalue Problem

- Hyper-Wiener indices of polyphenyl chains and polyphenyl spiders

- Razumikhin-type theorem on time-changed stochastic functional differential equations with Markovian switching

- Fixed Points of Meromorphic Functions and Their Higher Order Differences and Shifts

- Properties and Inference for a New Class of Generalized Rayleigh Distributions with an Application

- Nonfragile observer-based guaranteed cost finite-time control of discrete-time positive impulsive switched systems

- Empirical likelihood confidence regions of the parameters in a partially single-index varying-coefficient model

- Algebraic loop structures on algebra comultiplications

- Two weight estimates for a class of (p, q) type sublinear operators and their commutators

- Dynamic of a nonautonomous two-species impulsive competitive system with infinite delays

- 2-closures of primitive permutation groups of holomorph type

- Monotonicity properties and inequalities related to generalized Grötzsch ring functions

- Variation inequalities related to Schrödinger operators on weighted Morrey spaces

- Research on cooperation strategy between government and green supply chain based on differential game

- Extinction of a two species competitive stage-structured system with the effect of toxic substance and harvesting

- *-Ricci soliton on (κ, μ)′-almost Kenmotsu manifolds

- Some improved bounds on two energy-like invariants of some derived graphs

- Pricing under dynamic risk measures

- Finite groups with star-free noncyclic graphs

- A degree approach to relationship among fuzzy convex structures, fuzzy closure systems and fuzzy Alexandrov topologies

- S-shaped connected component of radial positive solutions for a prescribed mean curvature problem in an annular domain

- On Diophantine equations involving Lucas sequences

- A new way to represent functions as series

- Stability and Hopf bifurcation periodic orbits in delay coupled Lotka-Volterra ring system

- Some remarks on a pair of seemingly unrelated regression models

- Lyapunov stable homoclinic classes for smooth vector fields

- Stabilizers in EQ-algebras

- The properties of solutions for several types of Painlevé equations concerning fixed-points, zeros and poles

- Spectrum perturbations of compact operators in a Banach space

- The non-commuting graph of a non-central hypergroup

- Lie symmetry analysis and conservation law for the equation arising from higher order Broer-Kaup equation

- Positive solutions of the discrete Dirichlet problem involving the mean curvature operator

- Dislocated quasi cone b-metric space over Banach algebra and contraction principles with application to functional equations

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator on the open semi-axis

- Differential polynomials of L-functions with truncated shared values

- Exclusion sets in the S-type eigenvalue localization sets for tensors

- Continuous linear operators on Orlicz-Bochner spaces

- Non-trivial solutions for Schrödinger-Poisson systems involving critical nonlocal term and potential vanishing at infinity

- Characterizations of Benson proper efficiency of set-valued optimization in real linear spaces

- A quantitative obstruction to collapsing surfaces

- Dynamic behaviors of a Lotka-Volterra type predator-prey system with Allee effect on the predator species and density dependent birth rate on the prey species

- Coexistence for a kind of stochastic three-species competitive models

- Algebraic and qualitative remarks about the family yy′ = (αxm+k–1 + βxm–k–1)y + γx2m–2k–1

- On the two-term exponential sums and character sums of polynomials

- F-biharmonic maps into general Riemannian manifolds

- Embeddings of harmonic mixed norm spaces on smoothly bounded domains in ℝn

- Asymptotic behavior for non-autonomous stochastic plate equation on unbounded domains

- Power graphs and exchange property for resolving sets

- On nearly Hurewicz spaces

- Least eigenvalue of the connected graphs whose complements are cacti

- Determinants of two kinds of matrices whose elements involve sine functions

- A characterization of translational hulls of a strongly right type B semigroup

- Common fixed point results for two families of multivalued A–dominated contractive mappings on closed ball with applications

- Lp estimates for maximal functions along surfaces of revolution on product spaces

- Path-induced closure operators on graphs for defining digital Jordan surfaces

- Irreducible modules with highest weight vectors over modular Witt and special Lie superalgebras

- Existence of periodic solutions with prescribed minimal period of a 2nth-order discrete system

- Injective hulls of many-sorted ordered algebras

- Random uniform exponential attractor for stochastic non-autonomous reaction-diffusion equation with multiplicative noise in ℝ3

- Global properties of virus dynamics with B-cell impairment

- The monotonicity of ratios involving arc tangent function with applications

- A family of Cantorvals

- An asymptotic property of branching-type overloaded polling networks

- Almost periodic solutions of a commensalism system with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting on time scales

- Explicit order 3/2 Runge-Kutta method for numerical solutions of stochastic differential equations by using Itô-Taylor expansion

- L-fuzzy ideals and L-fuzzy subalgebras of Novikov algebras

- L-topological-convex spaces generated by L-convex bases

- An optimal fourth-order family of modified Cauchy methods for finding solutions of nonlinear equations and their dynamical behavior

- New error bounds for linear complementarity problems of Σ-SDD matrices and SB-matrices

- Hankel determinant of order three for familiar subsets of analytic functions related with sine function

- On some automorphic properties of Galois traces of class invariants from generalized Weber functions of level 5

- Results on existence for generalized nD Navier-Stokes equations

- Regular Banach space net and abstract-valued Orlicz space of range-varying type

- Some properties of pre-quasi operator ideal of type generalized Cesáro sequence space defined by weighted means

- On a new convergence in topological spaces

- On a fixed point theorem with application to functional equations

- Coupled system of a fractional order differential equations with weighted initial conditions

- Rough quotient in topological rough sets

- Split Hausdorff internal topologies on posets

- A preconditioned AOR iterative scheme for systems of linear equations with L-matrics

- New handy and accurate approximation for the Gaussian integrals with applications to science and engineering

- Special Issue on Graph Theory (GWGT 2019)

- The general position problem and strong resolving graphs

- Connected domination game played on Cartesian products

- On minimum algebraic connectivity of graphs whose complements are bicyclic

- A novel method to construct NSSD molecular graphs

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator of orders less than one

- Centralizers of automorphisms permuting free generators

- Extreme points and support points of conformal mappings

- Arithmetical properties of double Möbius-Bernoulli numbers

- The product of quasi-ideal refined generalised quasi-adequate transversals

- Characterizations of the Solution Sets of Generalized Convex Fuzzy Optimization Problem

- Augmented, free and tensor generalized digroups

- Time-dependent attractor of wave equations with nonlinear damping and linear memory

- A new smoothing method for solving nonlinear complementarity problems

- Almost periodic solution of a discrete competitive system with delays and feedback controls

- On a problem of Hasse and Ramachandra

- Hopf bifurcation and stability in a Beddington-DeAngelis predator-prey model with stage structure for predator and time delay incorporating prey refuge

- A note on the formulas for the Drazin inverse of the sum of two matrices

- Completeness theorem for probability models with finitely many valued measure

- Periodic solution for ϕ-Laplacian neutral differential equation

- Asymptotic orbital shadowing property for diffeomorphisms

- Modular equations of a continued fraction of order six

- Solutions with concentration and cavitation to the Riemann problem for the isentropic relativistic Euler system for the extended Chaplygin gas

- Stability Problems and Analytical Integration for the Clebsch’s System

- Topological Indices of Para-line Graphs of V-Phenylenic Nanostructures

- On split Lie color triple systems

- Triangular Surface Patch Based on Bivariate Meyer-König-Zeller Operator

- Generators for maximal subgroups of Conway group Co1

- Positivity preserving operator splitting nonstandard finite difference methods for SEIR reaction diffusion model

- Characterizations of Convex spaces and Anti-matroids via Derived Operators

- On Partitions and Arf Semigroups

- Arithmetic properties for Andrews’ (48,6)- and (48,18)-singular overpartitions

- A concise proof to the spectral and nuclear norm bounds through tensor partitions

- A categorical approach to abstract convex spaces and interval spaces

- Dynamics of two-species delayed competitive stage-structured model described by differential-difference equations

- Parity results for broken 11-diamond partitions

- A new fourth power mean of two-term exponential sums

- The new operations on complete ideals

- Soft covering based rough graphs and corresponding decision making

- Complete convergence for arrays of ratios of order statistics

- Sufficient and necessary conditions of convergence for ρ͠ mixing random variables

- Attractors of dynamical systems in locally compact spaces

- Random attractors for stochastic retarded strongly damped wave equations with additive noise on bounded domains

- Statistical approximation properties of λ-Bernstein operators based on q-integers

- An investigation of fractional Bagley-Torvik equation

- Pentavalent arc-transitive Cayley graphs on Frobenius groups with soluble vertex stabilizer

- On the hybrid power mean of two kind different trigonometric sums

- Embedding of Supplementary Results in Strong EMT Valuations and Strength

- On Diophantine approximation by unlike powers of primes

- A General Version of the Nullstellensatz for Arbitrary Fields

- A new representation of α-openness, α-continuity, α-irresoluteness, and α-compactness in L-fuzzy pretopological spaces

- Random Polygons and Estimations of π

- The optimal pebbling of spindle graphs

- MBJ-neutrosophic ideals of BCK/BCI-algebras

- A note on the structure of a finite group G having a subgroup H maximal in 〈H, Hg〉

- A fuzzy multi-objective linear programming with interval-typed triangular fuzzy numbers

- Variational-like inequalities for n-dimensional fuzzy-vector-valued functions and fuzzy optimization

- Stability property of the prey free equilibrium point

- Rayleigh-Ritz Majorization Error Bounds for the Linear Response Eigenvalue Problem

- Hyper-Wiener indices of polyphenyl chains and polyphenyl spiders

- Razumikhin-type theorem on time-changed stochastic functional differential equations with Markovian switching

- Fixed Points of Meromorphic Functions and Their Higher Order Differences and Shifts

- Properties and Inference for a New Class of Generalized Rayleigh Distributions with an Application

- Nonfragile observer-based guaranteed cost finite-time control of discrete-time positive impulsive switched systems

- Empirical likelihood confidence regions of the parameters in a partially single-index varying-coefficient model

- Algebraic loop structures on algebra comultiplications

- Two weight estimates for a class of (p, q) type sublinear operators and their commutators

- Dynamic of a nonautonomous two-species impulsive competitive system with infinite delays

- 2-closures of primitive permutation groups of holomorph type

- Monotonicity properties and inequalities related to generalized Grötzsch ring functions

- Variation inequalities related to Schrödinger operators on weighted Morrey spaces

- Research on cooperation strategy between government and green supply chain based on differential game

- Extinction of a two species competitive stage-structured system with the effect of toxic substance and harvesting

- *-Ricci soliton on (κ, μ)′-almost Kenmotsu manifolds

- Some improved bounds on two energy-like invariants of some derived graphs

- Pricing under dynamic risk measures

- Finite groups with star-free noncyclic graphs

- A degree approach to relationship among fuzzy convex structures, fuzzy closure systems and fuzzy Alexandrov topologies

- S-shaped connected component of radial positive solutions for a prescribed mean curvature problem in an annular domain

- On Diophantine equations involving Lucas sequences

- A new way to represent functions as series

- Stability and Hopf bifurcation periodic orbits in delay coupled Lotka-Volterra ring system

- Some remarks on a pair of seemingly unrelated regression models

- Lyapunov stable homoclinic classes for smooth vector fields

- Stabilizers in EQ-algebras

- The properties of solutions for several types of Painlevé equations concerning fixed-points, zeros and poles

- Spectrum perturbations of compact operators in a Banach space

- The non-commuting graph of a non-central hypergroup

- Lie symmetry analysis and conservation law for the equation arising from higher order Broer-Kaup equation

- Positive solutions of the discrete Dirichlet problem involving the mean curvature operator

- Dislocated quasi cone b-metric space over Banach algebra and contraction principles with application to functional equations

- On the Gevrey ultradifferentiability of weak solutions of an abstract evolution equation with a scalar type spectral operator on the open semi-axis

- Differential polynomials of L-functions with truncated shared values

- Exclusion sets in the S-type eigenvalue localization sets for tensors

- Continuous linear operators on Orlicz-Bochner spaces

- Non-trivial solutions for Schrödinger-Poisson systems involving critical nonlocal term and potential vanishing at infinity

- Characterizations of Benson proper efficiency of set-valued optimization in real linear spaces

- A quantitative obstruction to collapsing surfaces

- Dynamic behaviors of a Lotka-Volterra type predator-prey system with Allee effect on the predator species and density dependent birth rate on the prey species

- Coexistence for a kind of stochastic three-species competitive models

- Algebraic and qualitative remarks about the family yy′ = (αxm+k–1 + βxm–k–1)y + γx2m–2k–1

- On the two-term exponential sums and character sums of polynomials

- F-biharmonic maps into general Riemannian manifolds

- Embeddings of harmonic mixed norm spaces on smoothly bounded domains in ℝn

- Asymptotic behavior for non-autonomous stochastic plate equation on unbounded domains

- Power graphs and exchange property for resolving sets

- On nearly Hurewicz spaces

- Least eigenvalue of the connected graphs whose complements are cacti

- Determinants of two kinds of matrices whose elements involve sine functions

- A characterization of translational hulls of a strongly right type B semigroup

- Common fixed point results for two families of multivalued A–dominated contractive mappings on closed ball with applications

- Lp estimates for maximal functions along surfaces of revolution on product spaces

- Path-induced closure operators on graphs for defining digital Jordan surfaces

- Irreducible modules with highest weight vectors over modular Witt and special Lie superalgebras

- Existence of periodic solutions with prescribed minimal period of a 2nth-order discrete system

- Injective hulls of many-sorted ordered algebras

- Random uniform exponential attractor for stochastic non-autonomous reaction-diffusion equation with multiplicative noise in ℝ3

- Global properties of virus dynamics with B-cell impairment

- The monotonicity of ratios involving arc tangent function with applications

- A family of Cantorvals

- An asymptotic property of branching-type overloaded polling networks

- Almost periodic solutions of a commensalism system with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting on time scales

- Explicit order 3/2 Runge-Kutta method for numerical solutions of stochastic differential equations by using Itô-Taylor expansion

- L-fuzzy ideals and L-fuzzy subalgebras of Novikov algebras

- L-topological-convex spaces generated by L-convex bases

- An optimal fourth-order family of modified Cauchy methods for finding solutions of nonlinear equations and their dynamical behavior

- New error bounds for linear complementarity problems of Σ-SDD matrices and SB-matrices

- Hankel determinant of order three for familiar subsets of analytic functions related with sine function

- On some automorphic properties of Galois traces of class invariants from generalized Weber functions of level 5

- Results on existence for generalized nD Navier-Stokes equations

- Regular Banach space net and abstract-valued Orlicz space of range-varying type

- Some properties of pre-quasi operator ideal of type generalized Cesáro sequence space defined by weighted means

- On a new convergence in topological spaces

- On a fixed point theorem with application to functional equations

- Coupled system of a fractional order differential equations with weighted initial conditions

- Rough quotient in topological rough sets

- Split Hausdorff internal topologies on posets

- A preconditioned AOR iterative scheme for systems of linear equations with L-matrics

- New handy and accurate approximation for the Gaussian integrals with applications to science and engineering

- Special Issue on Graph Theory (GWGT 2019)

- The general position problem and strong resolving graphs

- Connected domination game played on Cartesian products

- On minimum algebraic connectivity of graphs whose complements are bicyclic

- A novel method to construct NSSD molecular graphs