Abstract

Objectives

Recently, phenolic compounds (quercetin, kaempferol, ellagic acid (EA), and myricetin) as natural sources have been suggested to be used for treatment and chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Since rosehip includes the above molecules in high concentration, we set out to investigate possible anti-proliferative effect of rosehip tea on the prostate cancer cell line.

Methods

The flavonol content of rosehip tea prepared at different temperatures and time intervals was determined first and then the antiproliferative effect of tea samples was established by adding tea samples to the prostate cancer cell line (VCaP and LNCaP).

Results

Quercetin was more effective in LNCaP cell than in VCaP cell (IC50 = 20 and 200 μM, respectively). The boiled fruit shredded at minute 7 showed the highest levels of quercetin, EA and kaempferol and the boiled fruit at minute 7 had the highest levels of kaempferol and EA. The tea samples were prepared in concentrations relevant to their IC50 values, added to the VCaP and LNCaP cell lines. The antiproliferative effect of rosehip tea on VCaP cells was slightly greater than that of LNCaP cells.

Conclusion

Each of the flavonols exhibits an antiproliferative effect. Our data clearly indicated that rosehip as a natural source of all flavonols had an antiproliferative effect on androgen-sensitive prostate cancer. Now that it is important to use natural sources in cancer, rosehip seems to be a promising natural product to be used to treat the prostate illness.

Öz

Amaç

Son zamanlarda yapılan çalışmalarda, doğal kaynak olan fenolik bileşiklerin (kuersetin, kemferol, ellagic asit, mirisetin) prostat kanseri tedavisinde ve kemoprevansında kullanılması önerilmiştir. Kuşburnu bu fenolik molekülleri yüksek konsantrasyonda içerdiğinden, kuşburnu çayının olası anti-proliferatif etkisini prostat kanseri hücre hattında araştırmayı amaçladık.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Kuşburnu çayının farklı sıcaklık ve zaman aralığında hazırlanmış örneklerinin flavonol içeriğini belirledik, daha sonra hazırlanan çayların antiproliferatif etkisi, prostat kanseri hücre hattına çay örnekleri eklenerek belirlendi (VCaP and LNCaP).

Bulgular

Hücre kültürü çalışması için en yüksek kuersetin, ellagik asit ve kemferol seviyelerine sahip 7 dakika kaynatılan parçalanmış meyve ve en yüksek kamferol ve ellagik asit seviyelerine sahip 7 dakika kaynatılan taze meyve seçildi. Çay örnekleri, IC50 değerlerine uygun konsantrasyonda hazırlandı, VCaP ve LNCaP hücre hattında çalışıldı. Kuersetin, LNCaP hücresinde VCaP hücresine göre daha etkili olduğu belirlendi (sırasıyla, IC50 = 20 μM ve 200 μM). Kuşburnu çaylarının VCaP hücreleri üzerindeki antiproliferatif etkisi, LNCaP hücrelerinden biraz daha güçlü etkiye sahip olduğu belirlendi.

Sonuçlar

Flavonollerin her biri tek başına anti-proliferatif etki göstermektedir. Verilerimiz tüm flavonollerin doğal bir kaynağı olan kuşburnunun androjene duyarlı prostat kanseri üzerinde anti-proliferatif etkisi olduğunu göstermiştir. Kanser tedavisinde doğal kaynakların kullanılması önemli olduğu için kuşburnu prostat kanseri tedavisinde kullanılabilecek umut verici bir doğal ürün gibi görünmektedir.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the world after lung cancer [1], [2], [3]. Androgen and androgen receptors have been demonstrated to induce the development and progression of cancer. Current treatment protocols have focused on reducing androgen and androgen receptors [1]. Although the ailment has been treated with chemotherapeutics and other invasive protocols, the death rate is relatively high and preventive approaches through the use of dietary substances become more important in controlling it [2]. Recent studies have shown that diet with phenolic acid is associated with a lower risk of prostate cancer [4], [5].

Rosehip, a fruit of the Rose genus of the Rosaceae family, has been widely used for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects across Europe [6], [7]. Different types, especially the most common type Rosa canina is cultivated in the Aegean region of Turkey. Rosehips have been proven to have antiproliferative properties against different types of cancer due to its content of vitamin C and E and phenolic compounds [7], [8].

Experimental studies have shown that rosehip is a rich in flavonols (a class of phenolic phytochemicals in terms of quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and fisetin) and ellagic acid (EA) of phenolic acids. The most abundant flavonoids are quercetin and kaempferol, followed by myricetin [7], [8], [9]. In vitro studies exhibited that flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, or myricetin) could inhibit invasion, migration and signaling molecules involved in cell proliferation in prostate cancer [5]. EA present in fruits and berries is a polyphenolic compound, which has anti-cancer effects in several types of human cancers, i.e., cancers of the esophagus, colon, skin, breast and prostate [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15].

The most common way to use rosehip extract is to prepare tea with hot water. Experimental studies showed that brewing conditions influenced the amount of phenolic compounds extracted from the rosehip fruit [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. İlyasoğlu et al. (2017) suggested that infusion time and water temperature influenced the antioxidant properties of rosehip teas [6].

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of rosehip tea on cell survival in prostate cancer cell lines, which are sensitive to androgen receptors. The major compounds (quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and EA) in rosehip teas were determined at different infusion times and brewing conditions. Moreover, tea samples including the highest amount of flavonols were used to measure the antiproliferative effect of rosehip.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and cell culture

Commercial phenolic compounds quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and EA were purchased from Fluka Co. Ltd., Germany and Sigma Co. Ltd., USA.

Human androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell lines, VCaP and LNCaP bought from The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were used in the study. LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel) containing 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). VCaP cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel) containing 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10% heat inactivated FBS. The cells were cultivated in a humidified incubator in an environment with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Preparation of rosehip tea

Rosehip teas were prepared under the following procedures. Fresh fruit collected from Aegean region of Turkey and dried fruit as commercially available fruit was purchased from local market.

The fresh fruits were both steeped as whole and as a shredded fruit using a knife. Both types of rosehip (1 g) were steeped with 10 mL distilled water for 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 min at different steeping temperatures of 80 °C and 100 °C.

Determination of quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and ellagic acid

Phenolic compound content of the teas were analyzed using LC-MS MS system [11]. The stock standards were prepared at 1 mg/mL concentration as stock and standard mixtures were made ready by dilution of 1/1,000. The DMAE Caffeate as internal standard was added to all samples to determine the loss of phenolic compounds due to matrix effect. Tea samples were diluted by 10 μL with methanol and standard mixtures. A linear gradient method has been used for MetOH/Water mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min with ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) column at 40 °C. The method took 5 min, starting with 100% water and a 1 min wash then gradually increasing the amount of MetOH and continuing 100% MetOH for 3 min. The target phenolic compounds investigated were quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin and EA. The specification of phenolic compounds and their related MRM values was shown in supplementary file (Table 1 in Supplementary file).

Real-time cytotoxicity assay

The xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) DP system (ACEA Biosciences) was employed to determine the cytotoxic effects of EA, kaempferol, myricetin, and quercetin on VCaP and LNCaP cells. The cells were seeded in 96 well e-plate (6.25 × 103 VCaP cells/well, 2.5 × 104 LNCaP cells/well). Twenty four hours later, cells were treated with 100–3.125 μM doubling dilutions of quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and EA, and were monitored every 15 min for 72 h. Calculation of IC50 values was obtained by the RTCA Software v 1.2.1.

Real-time growth inhibition assay

The xCELLigence system was used in order to determine the growth inhibition effects of Rosehip teas on VCaP and LNCaP cells. The cells were seeded in 96 well e-plate (6.25 × 103 VCaP cells/well, 2.5 × 104 LNCaP cells/well). Twenty four hours later, cells were treated with 100, 50 and 25% concentration of Rosehip teas and were monitored every 15 min for 72 h. Growth inhibition effects of Rosehip teas were assessed by the RTCA Software v 1.2.1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). p values were calculated by two-way ANOVA using the Tukey test for multiple comparisons.

Results

LC MS/MS results

The content of phenolic molecules in rosehip teas obtained with boiling and steeping at different time points was presented in supplementary file (Figure 1 in Supplementary file).

The amount of phenolic compounds extracted by boiling was higher than that of steeping. Our data showed that all flavonols were high in commercial boiled tea samples (dry rosehip) regardless of the weather. However, their highest levels in steeped commercial tea were observed in 3rd min. On the other hand, quercetin, EA, and kaempferol levels were maximum in shredded fruit between 5 and 7 min and kaempferol and EA levels were highest in boiled fruit in 7th min in boiling water. Accordingly, cell culture studies selected the four tea samples with the highest phenolic compounds in fruit, by boiling fresh fruit for 7 min, shredded one for 5 min, commercial tea for 7 min and commercial tea steeped for 3 min. Rosehip tea samples were freshly prepared before using for cell growth inhibition tests. Table 1 presents the final concentrations of flavonols in rosehip tea samples to be added to cell culture.

The flavonol concentration of tea samples which were added into cell line (μmol/L).

| Quercetin | Kaempferol | Ellagic acid | Myricetin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boiled fruit tea-7 min | 9.45 | 1.38 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Boiled shredded fruit tea-5 min | 5.42 | 2.68 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Boiled commercial tea-7 min | 51.8 | 2.35 | 1.35 | 1.95 |

| Steeped commercial tea-3 min | 50.4 | 2.21 | 1.2 | 1.85 |

Cytotoxic effects of commercial phenolic compounds on VCaP and LNCaP cells

Cytotoxic effects of quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and EA were determined based on the dose-response curves of the normalized cell index for 24th, 48th, and 72nd h by the RTCA Software. The IC50 values of the calculated commercial phenolic compounds are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and the dose-response curves in supplementary file (Figures 2 and 3 in Supplementary file).

IC50 values for commercial phenolic compounds in VCaP cell culture.

| 24th h | 48th h | 72nd h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quarcetin | 193 μM | 343 μM | 204 μM |

| Kaempferol | 4.17 μM | 5.74 μM | 2.06 μM |

| Miricetin | 17 μM | 24.5 μM | 30.8 μM |

| Ellagic acid | 25.9 μM | 45.4 μM | 11.8 μM |

IC50 values for commercial phenolic compounds in LNCaP cell culture.

| 24th h | 48th h | 72nd h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quarcetin | 14.5 μM | 31.7 μM | 32.2 μM |

| Kaempferol | 33.3 μM | 28.3 μM | 26.2 μM |

| Miricetin | 53.8 μM | 55.3 μM | 54.5 μM |

| Ellagic acid | 23.9 μM | 24.3 μM | 24.7 μM |

The growth inhibition effects of Rosehip teas on VCaP and LNCaP cells

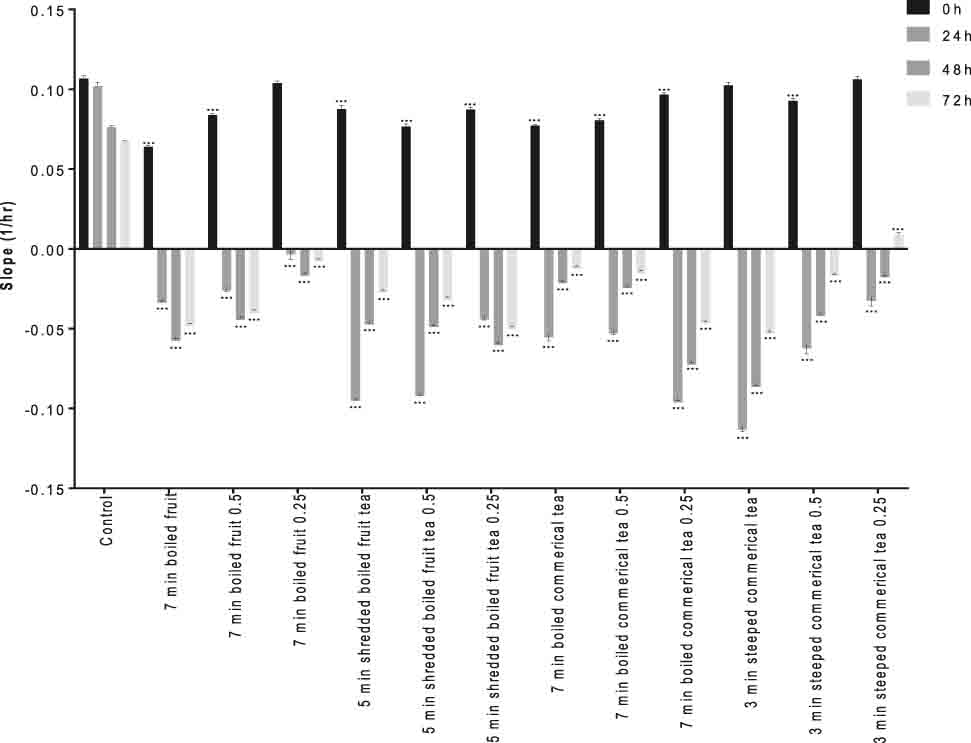

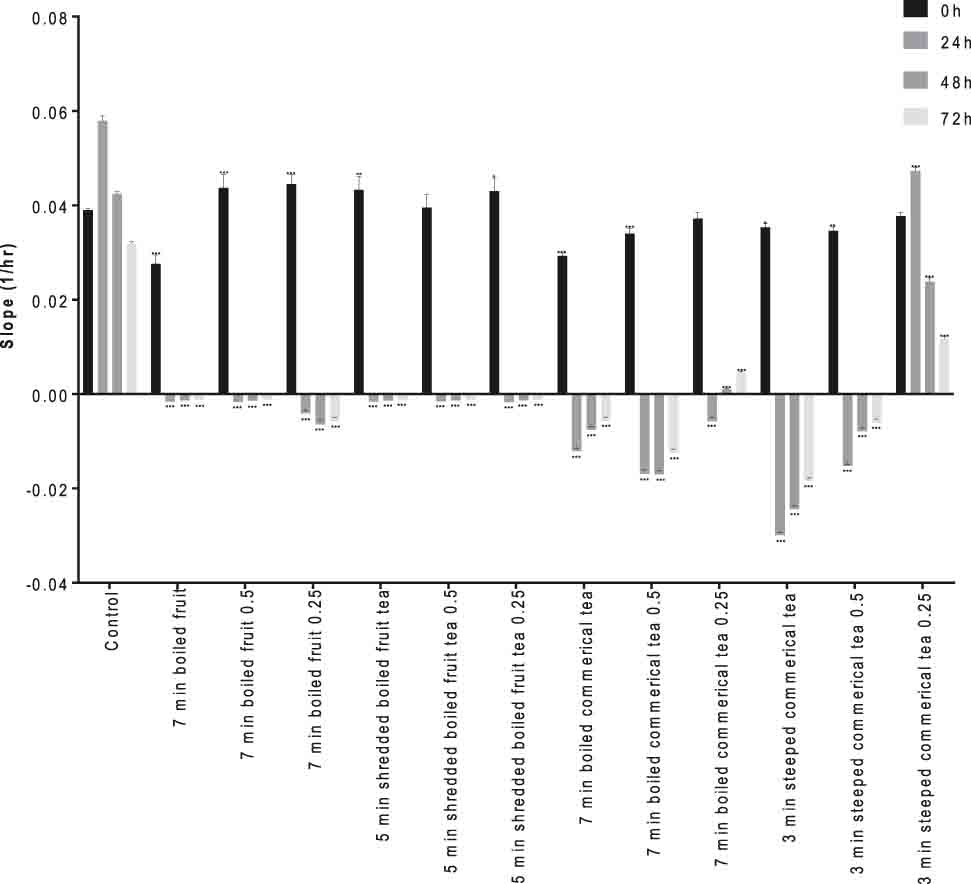

The growth inhibition effects of rosehip tea were studied considering changes in cell index in time and dose-dependent form using RTCA software. The lower slope plots (1/h) presented growth inhibition effects of rosehip teas, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Rosehip tea represses the cell index and proliferation of VCaP cells. The slope (1/h) describes the rate of change of the cell index for cells after rosehip tea treatment (24th h) calculated from period 0–24 h, 24–48 h, 48–72 h and 72–96 h. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *p<0.01, **p<0.001 and ***p<0.0001.

Discussion

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among males. It is estimated that one in six will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime [3]. Therefore, the studies focus on treatment and prevention of prostate cancer. Prostate cancer’s growth, invasion and metastasis have been shown to be inhibited by flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and fisetin), especially the potential use of fisetin to treat androgen-dependent prostate cancer currently under study [1], [4], [5], [12], [13]. The present study investigated the possible anti-proliferative effect of rosehip tea with high amounts of aforementioned flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol, myricetin, and fisetin) on prostate cancer cell line.

Many studies have recently suggested that Rosehip have anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities both in clinical and in-vitro studies [6], [14]. Rosehip extracts were traditionally consumed as tea using hot water. Recent studies have exhibited that brewing conditions affect the phenolic compound content as well as its anti-oxidant capacity [6], [7]. Our study showed that the higher amount of phenolic compound was obtained by boiling than in steeping. However, the levels of phenolic compounds in rosehip tea decreased after boiling more than 7 min.

Concentration of EA increased whereas that of myricetin decreased by boiling extract. We found that the highest myricetin content was acquired in 3 min steeped commercial tea and in 5 min boiled commercial tea. İlyasoğlu et al. observed that total phenolic content (TPC) increased with increasing time up to a certain degree and then changed slightly [6]. While the TPC was highest at times between 5.5 and 10 min and at temperatures between 77 and 86 °C, antioxidant activity (ferric-reducing antioxidant power) was highest at brewing time for 6–8 min and between 84 and 86 °C.

Our data showed that the same concentration of phenolic compounds in every period of time effected cell viability (Tables 2 and 3). We showed that IC50 concentration for myricetin in LNCaP cell culture was higher than that of other phenolic molecules. The trend in VCaP cells was observed to be completely different from LNCaP cells. IC50 concentration of quercetin, kaempferol, and EA at 48 h was higher than at 24 h and 72 h but that of myricetin IC50 at 72 h was maximum (Table 2). The quercetin IC50 concentration related to VCaP cell culture is higher than in other phenolic molecules extracted from rosehip tea.

The tea samples were added to the cell cultures in three different concentrations (direct, ½, and ¼) prepared by diluting them with culture medium and the cell viability monitored in 24, 48, and 72 h after with the addition of the samples. The data of the study was shown in Figure 1 for VCaP cells and in Figure 2 for LNCaP cells.

The results showed that 3 min-steeped commercial tea caused the repression of cell index and proliferation rate of LNCaP cells to be significantly higher than in other experimental groups over 24 h, in particular (Figure 2). No differences exist between 3 min steeped commercial tea (1/4) and control groups. We concluded that 7 min boiled commercial tea, 7 min boiled commercial tea (1/2), 3 min steeped commercial tea, 3 min steeped commercial tea (1/2) and 7 min boiled fruit (1/4) have highest impact on reduction of cell index and proliferation rate of LNCaP cells in comparison with other experimental groups. Seven minutes boiled commercial tea and 3 min steeped commercial tea of highest EA, quercetin, and myricetin content were the most effective ones. Lansky et al. observed that EA inhibited the invasion of human androgen-independent prostate cancer, PC3 cells, in vitro [15]. Since the affinity of EA to prostate is high, EA might accumulate in prostate tissue and is thus proposed as an anticancer agent for prostate.

Rosehip tea represses the cell index and proliferation of LNCaP cells. The slope (1/h) describes the rate of change of the cell index for cells after rosehip tea treatment (24th h) calculated from period 0–24 h, 24–48 h, 48–72 h and 72–96 h. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *p<0.01, **p<0.001 and ***p<0.0001.

EA with inhibitory properties against the collagenase/gelatinase might prevent the metastasis of tumor by reducing the motility and the invasion of the cells LNCaP cell-line is an androgen-responsive prostate cancer cell. The acid expresses androgen receptor and androgen-inducible genes. Quercetin has antiproliferative effect by blocking signal transduction pathways especially Inositol 1,4,5 triphosphate [5], [16]. The study determined that quercetin was more effective in LNCaP cell (IC50 = 20 μM) than VCaP cell line (IC50 = 200 μM). Xing et al. showed that quercetin treatment inhibited the transcription of Androgen receptors in LNCaP cells and down-regulated the androgen related proteins (Prostate specific antigen, Human glandular kallikrein) which regulate tumor cell growth, invasion and osteoblastic metastasis [17]. Although myricetin and EA levels have been found to be the highest in concentration in boiled and steeped commercial tea samples, they are lower than at their IC50 levels. The antiproliferative effect of the tea samples were consequently concluded to be likely to be associated with their quercetin and kaempferol content, which was evidenced by our data to show that the effect of phenolic molecules on VCaP cells (Figure 1 in supplemental file) were slightly stronger than that of LNCaP cells, as compared to their IC50 levels (Table 3). Supplemented Figure 1 shows shredded boiled fruit sample with the same concentration of kaempferol but lower concentration of EA, myricetin, and quercetin with the other tea samples strongly inhibits cell growth in VCaP cells. Kaempferol has been shown to reduce testosterone levels by inhibiting 5α-reductase isoenzyme 2 [5].

It is interesting to note that, the cell index and proliferation rate improved slightly in both cell lines during the time period (from 24 to 72), which could be accounted for by the acquisition of cell resistance in response to phenolic molecules by activating of unknown genes and cell signaling pathways. Another explanation could be that phenolic compounds must have accumulated over time.

No matter what the influence of each flavonol on prostate cancer could be, it can be speculated that the combined effect was stronger than individual effect of each flavonol. It is therefore recommended to use natural sources for treatment strategies rather than artificial molecules.

In conclusion, the results of the study showed that rosehip tea reduced growth and cell proliferation in the line of prostate cancer cells which are sensitive to androgens. Although we did not investigate the case by highlighting the mechanism of inhibition of cell growth in cell levels by flavonols in rosehip, our data clearly indicated that rosehip tea as a natural source of flavonols could be recommended to manage prostate cancer.

Despite the fact that amount extracted from phenolic molecules changes based on the preparation techniques and timing, the optimal conditions are required to be determined for acquisition of the highest possible concentration of flavonols before using for treatment. Further research is needed to determine the value of rosehip tea for treatment of prostate cancer in vivo.

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: AM Özgönül wrote the paper, A.Aşık and R. Aslaminabad performed cell culture study, B.Durmaz prepared tea samples and performed LC MS/MS measurement, C.Gündüz analysed data, EY Sözmen designed the analysis and contributed data.

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest among the authors.

References

1. Chhabra, G, Singh, CK, Ndiaye, MA, Fedorowicz, S, Molot, A, Ahmad, N. Prostate cancer chemoprevention by natural agents: clinical evidence and potential implications. Cancer Lett 2018;422:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2018.02.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Malik, A, Afaq, S, Shahid, M, Akhtar, K, Assiri, A. Influence of ellagic acid on prostate cancer cell proliferation: a caspase–dependent pathway. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2011;4:550–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1995-7645(11)60144-2.Search in Google Scholar

3. Siegel, RL, Miller, KD, Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21442.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Russo, G, Campisi, D, Di Mauro, M, Regis, F, Reale, G, Marranzano, M, et al. Dietary consumption of phenolic acids and prostate cancer: a case-control study in Sicily, Southern Italy. Molecules 2017;22:2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22122159.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Boam, T. Anti-androgenic effects of flavonols in prostate cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2015;9:585. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2015.585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. İlyasoğlu, H, Arpa, TE. Effect of brewing conditions on antioxidant properties of rosehip tea beverage: study by response surface methodology. J Food Sci Technol 2017;54:3737–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-017-2794-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Lantano, C, Rinaldi, M, Cavazza, A, Barbanti, D, Corradini, C. Effects of alternative steeping methods on composition, antioxidant property and colour of green, black and oolong tea infusions. J Food Sci Technol 2015;52:8276–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-015-1971-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Hajiaghaalipour, F, Sanusi, J, Kanthimathi, MS. Temperature and time of steeping affect the antioxidant properties of white, green, and black tea infusions. J Food Sci 2016;81:H246–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.13149.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Kelebek, H. LC-DAD–ESI-MS/MS characterization of phenolic constituents in turkish black tea: effect of infusion time and temperature. Food Chem 2016;204:227–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Sharpe, E, Hua, F, Schuckers, S, Andreescu, S, Bradley, R. Effects of brewing conditions on the antioxidant capacity of twenty-four commercial green tea varieties. Food Chem 2016;192:380–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Castro, C, Mura, F, Valenzuela, G, Figueroa, C, Salinas, R, Zuñiga, MC, et al. Identification of phenolic compounds by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS and antioxidant activity from chilean propolis. Food Res Int 2014;64:873–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.08.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Senthilkumar, K, Arunkumar, R, Elumalai, P, Sharmila, G, Gunadharini, DN, Banudevi, S, et al. Quercetin inhibits invasion, migration and signalling molecules involved in cell survival and proliferation of prostate cancer cell line (PC-3). Cell Biochem Funct 2011;29:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbf.1725.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Cheng, T-C, Lu, J-F, Wang, J-S, Lin, L-J, Kuo, H-I, Chen, B-H. Antiproliferation effect and apoptosis mechanism of prostate cancer cell PC-3 by flavonoids and saponins prepared from Gynostemma pentaphyllum. J Agric Food Chem 2011;59:11319–29. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf2018758.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Tumbas, VT, Canadanovic-Brunet, JM, Cetojevic-Simin, DD, Cetkovic, GS, Ethilas, SM, Gille, L. Effect of rosehip (Rosa canina L.) phytochemicals on stable free radicals and human cancer cells. J Sci Food Agric 2012;92:1273–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4695.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lansky, EP, Harrison, G, Froom, P, Jiang, WG. Pomegranate (Punica granatum) pure chemicals show possible synergistic inhibition of human PC-3 prostate cancer cell invasion across MatrigelTM. Invest New Drugs 2005;23:121–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-005-5856-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Yuan, H, Young, CYF, Tian, Y, Liu, Z, Zhang, M, Lou, H. Suppression of the androgen receptor function by quercetin through protein-protein interactions of Sp1, c-Jun, and the androgen receptor in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2010;339:253–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-010-0388-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Xing, N, Chen, Y, Mitchell, SH, Young, CY. Quercetin inhibits the expression and function of the androgen receptor in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2001;22:409–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/22.3.409.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/tjb-2019-0262).

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Development of new total RNA isolation method for tissues with rich phenolic compounds

- Myofibrillar degeneration with diphtheria toxin

- In vitro and in silico studies on AChE inhibitory effects of a series of donepezil-like arylidene indanones

- In vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of methanolic extract of Asparagus horridus grows in North Cyprus Kuzey Kıbrıs da yetişen Asparagus horridus metanolik ekstraktının in-vitro antioksidan, anti-enflamatuar ve anti-kanser aktivitesi

- Purification and characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Eisenia fetida and effects of some pesticides and metal ions

- Nephroprotective effects of eriocitrin via alleviation of oxidative stress and DNA damage against cisplatin-induced renal toxicity

- The impact of orally administered gadolinium orthovanadate GdVO4:Eu3+ nanoparticles on the state of phospholipid bilayer of erythrocytes

- An anxiolytic drug buspirone ameliorates hyperglycemia and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic rat model

- Effects of mesenchymal stem cell and amnion membrane transfer on prevention of pericardial adhesions

- How potential endocrine disruptor deltamethrin effects antioxidant enzyme levels and total antioxidant status on model organisms

- Antiproliferative effect of rosehip tea phenolics in prostate cancer cell lines

- Investigation of MMP-9 rs3918242 and TIMP-2 rs8179090 polymorphisms in renal cell carcinoma tissues

- Investigation of SR-BI gene rs4238001 and rs5888 polymorphisms prevalence and effects on Turkish patients with metabolic syndrome

- Assessment of the frequency and biochemical parameters of conjunctivitis in COVID-19 and other viral and bacterial conditions

- Short Communication

- Lack of hotspot mutations other than TP53 R249S in aflatoxin B1 associated hepatocellular carcinoma

- Letter to the Editors

- Cornuside, identified in Corni fructus, suppresses melanin biosynthesis in B16/F10 melanoma cells through tyrosinase inhibition

- The extract of male bee and beehive from Bombus terrestris has biological efficacies for promoting skin health

- COVID-19 laboratory biosafety guide

- Retraction note

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Development of new total RNA isolation method for tissues with rich phenolic compounds

- Myofibrillar degeneration with diphtheria toxin

- In vitro and in silico studies on AChE inhibitory effects of a series of donepezil-like arylidene indanones

- In vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of methanolic extract of Asparagus horridus grows in North Cyprus Kuzey Kıbrıs da yetişen Asparagus horridus metanolik ekstraktının in-vitro antioksidan, anti-enflamatuar ve anti-kanser aktivitesi

- Purification and characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Eisenia fetida and effects of some pesticides and metal ions

- Nephroprotective effects of eriocitrin via alleviation of oxidative stress and DNA damage against cisplatin-induced renal toxicity

- The impact of orally administered gadolinium orthovanadate GdVO4:Eu3+ nanoparticles on the state of phospholipid bilayer of erythrocytes

- An anxiolytic drug buspirone ameliorates hyperglycemia and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic rat model

- Effects of mesenchymal stem cell and amnion membrane transfer on prevention of pericardial adhesions

- How potential endocrine disruptor deltamethrin effects antioxidant enzyme levels and total antioxidant status on model organisms

- Antiproliferative effect of rosehip tea phenolics in prostate cancer cell lines

- Investigation of MMP-9 rs3918242 and TIMP-2 rs8179090 polymorphisms in renal cell carcinoma tissues

- Investigation of SR-BI gene rs4238001 and rs5888 polymorphisms prevalence and effects on Turkish patients with metabolic syndrome

- Assessment of the frequency and biochemical parameters of conjunctivitis in COVID-19 and other viral and bacterial conditions

- Short Communication

- Lack of hotspot mutations other than TP53 R249S in aflatoxin B1 associated hepatocellular carcinoma

- Letter to the Editors

- Cornuside, identified in Corni fructus, suppresses melanin biosynthesis in B16/F10 melanoma cells through tyrosinase inhibition

- The extract of male bee and beehive from Bombus terrestris has biological efficacies for promoting skin health

- COVID-19 laboratory biosafety guide

- Retraction note