Abstract

The present paper attempts to describe the divergences between nearly synonymous phrasal verb/simplex pairs from court trials dating back to the Late Modern English period (LModE). The intention was to evaluate the effects that each verb form might exert in discourse, interpreting the lexical choice as functionally linked to the contents of the legal-lay discourse, that is the discourse between lay people and professionals in the courtroom (Heffer 2005: xv).

Research to date has highlighted how the choice of one form or another needs to be explained in terms of register and degree of expressiveness (Bolinger 1971: 172; McArthur 1989: 40; Hiltunen 1999: 161; Claridge 2000: 221). However, no studies have yet evaluated the difference between phrasal verbs and simplexes from a phraseological perspective, or reflected on how their use is functionally linked to the communicative needs in courtroom settings.

The study was conducted on the Late Modern English-Old Bailey Corpus (LModE-OBC), a self-compiled corpus that covers the century 1750–1850 and that includes a selection of trials drawn from The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London’s Central Criminal Court.

1 Introduction

The present study examines cases of synonymy between phrasal verbs (hereafter PVs) e.g. to go on and to leave off, and simplex verbs of Romance origin e.g. to continue and to desist, in courtroom discourse of the Late Modern English (LModE) period. I evaluate linguistic differences and the effects that each verb form could exert in discourse, interpreting the lexical choice as functionally linked to the contents and purposes of legal-lay discourse, that is the discourse between lay people and professionals in the courtroom (Heffer 2005: xv).

English has two alternative verb systems. On the one hand, there are PVs which consist of a base verb (to come, to go, to take, to throw, etc.) and a particle (in, out, up, etc.) exhibiting a strong internal cohesion (Quirk et al. 1985: 1150; cf. Biber et al. 1999), which are among the phraseological forms existing in English (Gries 2008: 7). On the other hand, there are simplexes, such as to depart, to return, which are mainly of Romance origin and often provide synonymous alternatives to PVs (Kennedy 1920: 131; Dixon 1982: 3–4; Biber et al. 1999: 403). An immediate consequence is the choice a speaker has to use a simplex or a phraseological form, which differ in terms of origin and etymology (Kennedy 1920: 29–32; Brinton 1996: 191; Thim 2012: 185–192) but that refer to the same conceptual frame. Nevertheless, despite them being very close to each other in semantic terms, a difference may arise “however large or slight it may turn out to be” (Claridge 2000: 228; cf. Kennedy 1920).

Many studies have, indeed, approached the pairs considering phraseological constituency as the major point of difference as it is reflected in the semantics of the verbs. In this respect, Claridge (2000) discussed the alternation between multi-word verbs (including PVs) and Romance verbs in the multi-genre Lampeter corpus covering the century 1640–1740 of the Early Modern English (EModE) period. The study of pairs occurring in texts belonging to the six domains of religion, politics, economy, science, law, and miscellaneous (Claridge 2000: 5) revealed that PVs are characterized by an expressive potential deriving from metaphorical traits that may activate schemata favouring inferences of metalinguistic contents: “one reason for their being used may lie in the speakers’ wish to strengthen or emphasize an idea expressed by the simplex” (Claridge 2000: 233, discussing Kennedy 1920). This is a consequence of the complex semantic characteristics of PVs whose meanings “range on a cline from purely compositional to highly idiomatic” (Thim 2012: 11; cf. Dixon 1982: 9; Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 76–84) and are overall “deviated from the more or less literal sum of the parts” (Bolinger 1971: 97). Some verbs exhibit a completely literal meaning such as to come in, to go back, whereas other instances portray an idiomatic connotation, such as to get by, to give up. In between, there are verbs characterized by a semi-compositional meaning and referred to as aspectual verbs (Thim 2012: 16–19; cf. König 1973), e.g. to bring in, to go on, to work out. In this case, the additional particle operates as an aspectualizer, denoting aspect, i.e. “the speaker’s viewpoint or perspective on a situation” and aktionsart, i.e. “the intrinsic temporal qualities of a situation” (Brinton 1988: 3).[1] The phraseological constituency of PVs is an important feature to examine in the evaluation of the PV/simplex pairs. It is not the only one, however.

On other occasions, the use of PVs has been treated considering the different degrees of formality of texts (McArthur 1989: 40; Hiltunen 1999: 161; Rodríguez–Puente 2016: 69–97). Indeed, their occurrence has been explained by accounting for a sort of ‘division of labour’ between simplexes and PVs, with the former communis opinio treated as more “stylistically elevated” than the latter, which are of Germanic origin (Thim 2012: 40; cf. Hiltunen 1999: 161), and conversely associated with “informal contexts of language use” in the history of English up to modern times (Hiltunen 1999: 161; cf. Claridge 2000: 221; Smitterberg 2008: 283–284; Wild 2010: 234; Rodríguez-Puente 2016: 80–81).

In theory, diverse linguistic effects may be produced in the discourse according to the verb form used, and this, by extension, raises the possibility that lexical choice between the two forms is functionally linked to the specific purposes of the communicative act. If, as claimed in the Neo-Firthian approach, “at each slot, virtually any word can occur” (Sinclair 1991: 109), then the selection of lexical resources can be interpreted as a powerful opportunity to attain specific purposes in communication. This assertion is particularly relevant for the subject-specific domain of legal-lay discourse in the courtroom setting.

Legal-lay discourse is, in fact, a “complex genre”[2] featuring two interrelated planes: that of “the construction of the case (...) and [that of] the reconstruction of the crime” (Heffer 2005: 65). This implies that the treatment of legal-lay discourse should account for aspects that go beyond “just how a particular text is constructed” as the need is to question “how the context surrounding that text influences its production and reception” (Gavins 2007: 8, cited in Zhenhua 2016: 96).

Phraseology plays an important role in legal language (Crystal and Davy 1969) and phraseological forms are frequent in legal settings (Crystal and Davy 1969; Tiersma 1999; Kjær 2007). While this helps to characterize legal-lay discourse, it also reveals its complexity. Legal-lay discourse entails aspects of ordinary language mixed with the formal language of the law and, thus, phraseological forms turn out to belong to different spheres, which embrace forms conventionalized in norms and statutes but also those operating in everyday language (Kjær 2007; Tiersma 2008). In both domains, the lexical choice could be related to the specific function the item performs in interaction with meanings pragmatically negotiated by speakers who are free to choose between alternative lexical forms, like the PV/simplex alternation. The need is to examine alternative forms to evaluate whether and to what extent there are factors that drive the lexical choice by investigating the semantic effects of each verb form in discourse.

The present study was conducted on a self-compiled corpus named the Late Modern English-Old Bailey Corpus (LModE-OBC), which consists of transcripts of court hearings selected from The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London’s Central Criminal Court (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/). The focus is on the part of the LModE period from 1750–1850, when PVs firstly become “well integrated with the language and appear in a wide range of contexts” (Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 14). This makes it well-suited to the purpose of studying cases of rivalry that account for possible divergences in their functional use.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the theoretical background while Section 3 describes the present study and provides details on the data and methodology used. Section 4 is devoted to the discussion of the results whereas Section 5 includes the conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2 Theoretical background

Departing from the conceptualization of phraseology of the East European tradition, which is heavily dependent on idiomaticity and fixedness (Cowie 1988, 1998; Mel’čuk 1998), in this paper PVs are examined from a distributional perspective (Sinclair 1991, 1994). This entails that a PV may be seen as a phraseologism that is “the co-occurrence of a form or a lemma of a lexical item and one or more additional linguistic elements of various kinds which functions as one semantic unit in a clause or sentence” (Gries 2008: 6). In this definition, Gries revisits the traditional approaches to phraseology supported within the cognitive linguistics/construction grammar (CG) frameworks and combines them with the corpus linguistics of the Neo-Firthian tradition (Sinclair 1991, 1994). Acceptance of this integrated perspective has two implications: (i) PVs are a phraseological form even when they are compositional in meaning; (ii) the instances that are not lexicalized can still be examined as extended units of meanings embracing in this way the Neo-Firthian tradition (Sinclair 1991, 1994; Stubbs 2002).

The reason for exploring the use of PVs in legal-lay discourse is that, despite many attempts to “develop comprehensive theories”, phraseological forms in Language for Specific Purposes (LSP) have been consigned to the “periphery of the discipline of phraseology” and have often been considered as partly overlapping with the science of terminology or even treated as a “special case” apart from other disciplines (Kjær 2007: 506–507). As mentioned in Section 1, the specialized language of the courtroom is interspersed with ordinary expressions, and both are influenced by the context of use, including the speakers’ roles and positions, the physical setting, and the subject matter. The context can affect the production and reception of language and may drive lexical choice between alternative forms.

These considerations are closely intertwined with a distinction very recently made by Szcyrbak (2017: 241) in the phraseology of LSP, between two interacting planes: (i) the phraseology of legal language meant as all the elements that portray a “specific judicial meaning”; (ii) legal phraseology, including all multi-word instances belonging to the “phraseological system as a whole” with no specific reference to the law. In other words, items expressing “attitudinal and pragmatic functions” (Tognini-Bonelli 2002: 79) occur side by side with “prefabricated” items that are a specific part of legal discourse (Kjær 2007: 512).

Legal-lay discourse is characterized by a high degree of terminological complexity and, as Kjær (2007) suggests, by various types of phraseological forms. She examines German legal phraseology and notes that there are “norm-conditioned word combinations” that are directly prescribed by law, and others that are part of the ordinary language but that can be used in legal settings as well (Kjær 2007: 510). She further states that “the language of law has no universal validity” and that “non-equivalence is the rule rather than the exception” (Kjær 2007: 508; cf. Kjær 1995). This supports a conceptualization of phraseology in legal texts as being closely connected with the legal system, which determines the language used, the meanings, and the functions of phraseological forms that consequently should be studied as ‘situated’ in that specific area (Kjær 1994, 2007).

Many studies have examined legal phraseology to date, but the focus has mainly been on contrastive analysis undertaken in translation (Goźdź-Roszkowski 2013) and on formulaic expressions and lexical bundles considered as typical features of the language of the law (Crystal and Davy 1969; Coulthard and Johnson 2007). However, no studies have yet evaluated the difference between phrasal verbs and simplexes from a phraseological perspective, or reflected on how their use is functionally linked to the communicative needs in courtroom settings.

3 The present study

3.1 Aims

Starting from the idea that during an interaction, the speaker has a choice between synonymous forms like PV/simplex pairs, the present study aims:

to describe the PV/simplex alternation in legal-lay discourse from the LModE period (1750–1850);

to examine from a phraseological point of view the linguistic differences between alternative forms;

to evaluate the functional uses of PV/simplex alternation in terms of the degree of idiomaticity of verbs;

to interpret the results in the light of the communicative purposes of speakers interacting in legal settings.

3.2 Method

This corpus-based investigation aimed to describe the alternation of some PV/simplex pairs and their functional use, and to interpret the results in the light of the phraseological distributional approach to language use (Sinclair 1991, 1994; Stubbs 2002).

To study the linguistic features of the PV/simplex pairs and their use in interaction, three different aspects were considered: (i) the complex internal constituency of PVs, which can favour shifts in the semantic nuances of instances; (ii) the immediate context of use as a factor contributing both to the linguistic identity of PVs and simplexes and to their semantic divergences; (iii) the lexical environment as an indicator of the functional roles performed by each verb form.

Following Claridge’s work (2000: 223–224), the pairs examined include: to accelerate/to speed up; to advance/to go-come forth; to compile/to heap up; to compose/to draw up; to conceal/to hide away; to conjoin/to join together; to continue/to go on; to delay/to put off; to depart/to go away; to desist/to leave off; to distribute/to give out; to cause-effect/to bring about; to discover/to find out; to erect-establish/to set up; to extinguish/to put out; to import/to bring in; to maintain/to keep up; to omit/to leave out; to remove/to put-take away; to retreat/to draw back; to return/to come back; to revoke/to take back; to separate/to set apart. This list was complemented with other pairs like to arrest/to bring in; to capture/to pick up; to collect/to pick up, which are closely linked to the topics treated in courtroom settings. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was used for information on etymology and to identify the meaning of each verb (https://www.oed.com).

The PV/simplex pairs were retrieved using WordSmith Tools 6.0 (https://www.lexically.net/wordsmith/), an integrated suite of programs including Concordance searches, WordList, and KeyWord analysis. In particular, the Concordance window was set to show the node verb and the surrounding context within a 0:4 span. The following were calculated: Raw frequency (Rf), Normalized frequency (Nf), percentages (%), and percentage points.

3.3 The corpus

The present research was conducted on a self-compiled corpus called the Late Modern English-Old Bailey Corpus (hereafter LModE-OBC). It contains texts selected from The Proceedings of the Old Bailey (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/).[3] The data consist of transcriptions of spoken language known to be accurate records of speech events in the courtroom (Huber 2007; Widlitzki and Huber 2016). Court trials belong to the speech-based genres (Culpeper and Kytö 2010: 17), that is “varieties originating in speech that have been permanently preserved in writing” (Biber and Finegan 1992:689) and that are “based on an actual ‘real-life’ speech event” (Culpeper and Kytö 2010: 17). The Proceedings of the Old Bailey houses texts recorded from 1674 right up to 1913 (Huber 2007), but the corpus used in the present study (the LModE-OBC) was formed with texts selected from the period 1750–1850. The reason for this choice was that from the 1750s onwards the transcripts include accurately recorded direct speech.

The LModE-OBC consists of five subcorpora of approximately 200,000 words each, as shown in Tab. 1, and contains 1,008,234 words overall.

Architecture and size of the Late Modern English-Old Bailey Corpus

| Subc–1 1750s | 1750–1759 1760–1769 |

around 200,000 words per subcorpus |

1,008,234 words |

| Subc–2 1770s | 1770–1779 1780–1789 |

||

| Subc–3 1790s | 1790–1899 1800–1809 |

||

| Subc–4 1810s | 1810–1819 1820–1829 |

||

| Subc–5 1830s | 1830–1839 1840–1849 |

To achieve a representative sample (Biber et al. 1998), 10,000 words of text per year were randomly selected from The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. These were then assembled in decades containing around 100,000 words. The decades were paired to form five subcorpora of around 200,000 words each.

All the texts included in the LModE-OBC contain direct speech transcribed in shorthand (Huber 2007), and they report exchanges between defendants, lawyers, judges, and witnesses. Successive speaking turns, which are sometimes interspersed with confessions rendered as monologues, allow access to the spoken language of past periods and to trial talk, made up of questions and answers with identifiable speakers and shaped on the legal practices of the time.

Despite the corpus being diachronic in structure, it has been treated as a snapshot of the LModE period to obtain a synchronic glimpse into legal-lay discourse as it was used during the period 1750–1850.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Paradigmatic relations and frequency distribution of the PV/simplex pairs

Quantitative study of the selected pairs occurring in the LModE-OBC revealed that PVs are more frequent than simplexes, amounting to 980 occurrences (54% of the total number) (see Tab. 2). This entails that the remaining 46% is accounted for by Romance verbs, making the divergence very limited (0.05 percentage points).

Frequency of the PV/simplex pairs in the LModE-OBC (1750–1850)

| Raw freq. | Normalized freq. (per 1,000 words) |

% | Percentage points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVs | 980 | 0.97 | 54 | +0.05 |

| Simplexes | 835 | 0.82 | 46 | –0.05 |

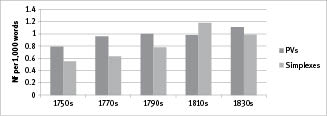

Concerning the respective frequency of the pairs within the decades, Fig. 1 below shows that the discrepancy between PVs and simplexes in terms of normalized frequency (Nf) is not significant, with an average difference between twenty-year periods of no more than 0.13 percentage points. However, the phraseological form is more frequently used in all the twenty-year subcorpora periods, except for the 1810s (see Fig. 1).

Frequency of PV/Simplex pairs in the LModE-OBC subcorpora

The consistency of use attested within the pairs in the years 1750–1850 and the preference for simplexes in the 1810s are points of significance for the description of PV/simplex pairs. Overall, these results have two important implications: (i) the high number of PVs renders legal-lay discourse of the LModE period close to the spoken language; (ii) the increasing number of simplexes could be interpreted as a sign of ongoing decolloquialization of trials during the LModE period as already observed in other works (Rodríguez-Puente 2016, 2019).

The prevalence of PVs in almost all the decades points to the high degree of spokenness of the genre of legal-lay discourse. The rather formal courtroom setting, the nature of the topics, and the purpose of interaction linked as it is to evidence construction (Heffer 2005: 70–82) might, indeed, presuppose a limited number of PVs considered as verbs “typical” of the spoken language (Claridge 2000: 192) and exhibiting a “colloquial character from the EModE period onwards” (Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 215, discussing Visser 1963: section 373).

As for the second point, the increasing use of simplexes over the decades and their prominence in the 1810s might be evidence of the evolution of proceedings during the LModE period towards a more formal register (Rodríguez-Puente 2016: 82, and Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 264–270). In this respect, Rodríguez-Puente (2016) suggested that the reduction in the number of PVs may be associated with the “decolloquialization” of trials and interpreted as the direct effect of “the change from a spontaneous discourse to pre-planned and articulated speech” affecting this register from 1800 onwards and especially after 1850 (Rodríguez-Puente 2016: 83, and Rodríguez-Puente 2019: 268). The overlap between the findings presented here and those of Rodríguez-Puente (2016: 69–97, and 2019: 264–270) suggests that the decolloquialization of trials may in part be attributed to competition within the PV/simplex pairs. Rodríguez-Puente’s (2016) report on decolloquialization concerns PVs alone, not alongside their Romance synonyms, and thus the results obtained here may be seen as evidence of the decolloquialization of trials was also a consequence of the increasing popularity of simplexes. Nonetheless, this does not exclude the existence of “other factors that [may] play a role in the variation” (Hiltunen 1994: 139) beyond register-specific matters and that may influence the speakers’ choice in interaction to favour one or the other form.

The hypothesis that there are other factors beyond the degree of formality of texts is supported by the fact that in the LModE-OBC there are cases where single PVs predominate and others where they do not. For example, to find out is more frequent than to discover, whereas to remove is more popular than to take/put away.

Looking at the semantic features of the pairs, another noticeable trend revealed by the data is that while aspectual PVs are higher in number than simplexes (385 PVs vs 127 simplexes), this is not the case with literal PVs[4] (540 PVs vs 566 simplexes) or with idiomatic PVs (75 PVs vs 141 simplexes). Given the diachronic nature of the data, the factors that may have determined the frequency of PVs are: (i) the decline in the use of the literal particle forth and its substitution with out, which began in the EModE period (Akimoto 1999: 232) and continued during the LModE period; (ii) the limited productivity of the literal particles apart and about as also attested in the EModE period (Claridge 2000: 126); and (iii) the lack of extensive conventionalization of idiomatic combinations, which limited their use.

Without entering into detail on diachronic aspects, the emerging scenario highlights the need for further investigation into the many factors influencing lexical choice or limiting it, to add to those already extensively confirmed to date (Bolinger 1971: 172; McArthur 1989: 40; Hiltunen 1999: 161; Claridge 2000: 221). A direct consequence of the dual nature of legal-lay discourse –the mixture of legal lexis with ordinary language –is that the PV/simplex pairs belong to two categories: (i) PVs/simplexes with no specific legal function or meaning that can be used interchangeably (e.g. to continue/to go on); (ii) PVs/simplexes with a specific legal function and meaning (e.g. to arrest/to bring in), which are not equivalent and cannot be substituted with other expressions that are similar in meaning.

4.2 Linguistic aspects of the PV/simplex pairs

Analysis of the data revealed that the relation of synonymy existing between the phraseological verbs and simplexes of Romance origin can be examined by considering a) the pragmatic force and the semantic enrichment deriving from the phraseological constituency of PVs (see Section 4.2.1); and b) the degree of specificity characterizing these verb forms (see Section 4.2.2). These considerations intertwine with the degree of idiomaticity of PVs, and they are closely connected with the relationship each of the items has within its immediate lexical environment.

4.2.1 Semantic enrichment and pragmatic force

PVs that contain a particle working as an aspectualizer (Brinton 1988: Ch. 4) such as to arrest/to bring in, to capture/to pick up, to continue/to go on, to extinguish/to put out, to retreat/to draw back, tend to exhibit more semantic enrichment and pragmatic force than their simplex counterparts. In these cases, indeed, the phraseological component points towards a durative/iterative (e.g. to go on) or an ingressive/perfective aspect (e.g. to bring in, to pick up), and the particle may contribute to metaphorical extension of the inner meanings of the combination, helping draw “a graphic ‘picture’” (Claridge 2000: 233) of the actions and processes expressed by the base verb itself.

This is exemplified by the pair to continue/to go on in (1)–(2) which share syntactic features while preserving specific semantic peculiarities:

She slept with my children, and continued with me until the 3d. of December. (1810s)

I saw the prisoner shove the beadle down, and went on with the dray. (1750s)

Comparison of the PV with the simplex reveals that these verbs are near-synonyms, at least in terms of their aspectual properties, as they both denote duration of the action. However, further analysis of the instances suggests that, differently from the simplex, the PV emphasizes the aspectual connotation. It seems that the temporal propensities that are incorporated in to continue are visibly expressed in the case of to go on: the acquisition of additional semantic nuances results in the reinforcement of the pragmatic traits.

The context of use is another element to examine in the evaluation of these verbs. While to continue normally occurs in contexts where there is a clear reference to the duration of the action in expressions such as long, many minutes, all day, and till Friday, the whole time, as in (3)–(4), to go on is usually followed by elements specifying manner and place, such as very gently, to the shop, directly, and regularly, to White lion-street, as in (5)–(6). It thus seems that the use of a PV obviates the need for further elements to highlight the durative side of the action. This could suggest that the aspectual particle is in itself an operator sufficient to express temporal relations and to incorporate an intensifying value.

The prisoner came into my service on the 4th of December last, and continued there till Friday the 10th. (1790s)

Did they continue the whole time the prisoner was at breakfast? (1790s)

Yes, till lately; at first he went on regularly. (1770s)

… and the butcher went on to White lion-street. (1830s)

Further corroborating the existence of both similarities and diversities between the verbs is the fact that both can be followed by a to–clause or an –ing clause, as in (7)–(10), although in the data, to continue is more frequently used with these patterns:

It is very much to the credit of the prisoner, rather than the child should go on to perjure herself, as she has done, she confesses it. (1790s)

I went on hearing the conversation about a robbery I had committed; the other two followed me in about five minutes. (1770s)

Then Farthing took his situation, as before, and continued to do so as if he was looking into the shop. (1810s)

Did the hackney coachman continue whipping as the mail coach was passing? (1790s)

Only 6 out of 126 occurrences of to go on are followed by either a to–clause (3 matches) or an –ing clause (3 matches), whereas 23 out of 61 occurrences of to continue were followed by 13 and 10 matches respectively. This means that only 4% of the instances of to go on are used with these patterns, in contrast with 37% for the simplex to continue. The use of the progressive form may be considered the point of departure for comprehension of the degree of ‘aspectuality’ of each of these verbs, in so far as the “aspectual interpretation of a sentence [or a verb in the case under examination here] depends on an interaction between (…) two categories”, i.e. aktionsart and aspect, expressed in the lexicon and by grammar respectively (Brinton 1988: 3). The progressive is one of the best examples of how grammatical modification enhances the perception of a situation as “continuing, ongoing, or developing, at a certain time” (Brinton 1988: 8–9). By extension, the fact that to continue is more frequently followed by the progressive than to go on could suggest that this is due to the linguistic identity of each verb form: it seems that the phraseological verb does not need further specification on the action as it is already expressed in the verb+particle combination.

This means that the simplex verb encodes event structure but that it also requires grammatical/extra-grammatical processes to yield durativity and to unlock its aspectual potential, in a process of ‘reflectivization’ from the context to the verb and viceversa.

Two further illustrative examples show the intensifying effect and the consequent semantic/pragmatic force prompted by the particle at the discourse level: the pairs to arrest/to bring in and to capture/to pick up. As with the pair to continue/to go on, they convey aspectual traits, but they are linked respectively to an ingressive and atelic connotation rather than to duration and continuity in time. Once again, the particles enrich the semantic features of the base verb and contribute to the aspectuality of the whole combination. Nevertheless, while the forms to continue/to go on portray similar meanings and may be used interchangeably, the choice between the PV and simplex of these pairs seems to be constrained by contextual factors.

The verbs to arrest/to bring in, reported in (11)–(14), denote the limitation of freedom and often occur with human subjects such as prisoner, or more generally, the prisoner’s name. On many occasions, the person arrested is rendered with pronouns such as me, as in example (13):

Were they all three brought in by strangers, or did any of the patrol bring them in? (1790s)

I remember the prisoner being brought in. (1770s)

Mr. Clarke, a tailor, arrested me for a bill of my own. (1830s)

I charged her with the theft, she confessed she had pawned them, because she was involved in debt, and was afraid of being arrested. (1770s)

The verb to bring in exhibits an aspectual force emphasizing that the activity expressed is characterized by an ingressive connotation, a meaning evident in the particle in, usually linked to “the beginnings of a prolonged activity” (Curme 1931: 379). Likewise, to arrest is not unrelated to such a connotation, as in (13)–(14) above, as it is linked to the restraint of liberty. The difference lies in the fact that linguistically, while aspectuality conflates with the verb to arrest itself, it is made more evident in to bring in, which is characterized by stronger aspectual properties than the simplex. As suggested, however, the shift from to arrest to the PV to bring in prompts another effect on discourse, as the pairs are not truly interchangeable. The simplex works as a necessary term in the legal domain because it is conventionalized with the specific meaning of ‘limiting the freedom due to the violation of rules’ and thus the choice may also be connected to the need for certainty in the semantic interpretation of discourse in the legal setting.

The conclusion is similar for the verbs to capture/to pick up. These verbs are not frequent in the data (to capture = 3 occurrences; to pick up = 6 occurrences) but due to the closeness they exhibit with to arrest and to bring in they were considered worthy of note. To capture expresses the concept of ‘to take into custody, apprehend; to capture’ (OED), which is similar to that of to pick up. As examples (15)–(16) below show, the effect is that the PV exhibits additional semantic nuances carried by the particle up, which conveys telic connotation:

I do not believe it is a common thing to pick up a man in the long-room. (1830s)

... and tried to make his escape a policeman close on the spot pursued, and very soon captured him. (1830s)

Once again, the members of the pair cannot be substituted without a significant semantic change as to capture exhibits very specific semantic traits that originate from legislative texts although it is also used in spoken interaction. The lexical choice, in other words, may not always be the result of strategic decisions, but might reflect the standardization of specific terms used for the sake of legal certainty.

More importantly, to pick up should also be compared with to collect, as these verbs are equivalent in semantic terms and are also more frequent than to capture/to pick up: to pick up occurs 184 times and to collect 23, in contrast with the 6 and 3 matches of the verbs to pick up and to capture.

Considering some examples of the verb to pick up, as in (17)–(18), and of the verb to collect, as in (19)–(20), once again the divergence between the PV and the simplex resides in the intensifying effect conferred by an aspectual particle. Up, indeed, portrays literal meanings but it can also be used to indicate perfective connotations “manifested in resultant condition” (Bolinger 1971:99). Both verbs possess a connotation linked to the act of ‘bringing’ a thing or a person and entail a sense of completion, but this seems to be more strongly emphasized in the phraseological form:

It was a dark evening; a gentleman picked me up, and brought me to Houndsditch. (1750s)

I stooped and picked the bundle up. (1770s)

I was collecting the poors rates, in New Inn on the 12th of December. (1770s)

I had promised to lend a gentleman some money, and must go and collect some for him. (1750s)

Beyond this similarity in meaning, if the PV is substituted for the corresponding simplex verb, the meaning of to collect remains only in part unchanged as the use of up transmits explicitly the “completive sense” (Fraser 1974: 6), thus contributing to “imagistic-metaphorical properties” of the PV (Hampe 2002: 46) much more than is the case for the simplex. This is not an exclusive feature of the PVs mentioned, as a similar conclusion may be reached from the comparison of other pairs, e.g. to extinguish/to put out and to retreat/to draw back, as in (21)–(24):

The light was not extinguished by our coughing, as I supposed it would be. (1810s)

Did they see you – A. Yes; they put out their lights immediately, they seemed to me to have two lights. (1790s)

The gentleman retreated with all possible speed. (1770s)

I drew back into a dark part of my passage. (1810s)

Examples (21)–(24) show the intensifying effect produced by the aspectual particles and confirm the idea that the use of a PV results in semantic enrichment of the whole utterance. When matching these ideas with the contents and purposes of trials as “evidence construction” (Heffer 2005: 70), it is even possible to interpret the lexical choice as functionally oriented to give an emphatic value to specific aspects of the crime, as the intention was to stress some elements over the others when narrating the crime story.

Overall, this suggests that the semantic enrichment deriving from the phraseological status of PVs and the aspectual connotation of the particle is one of the major points of distinction between PVs and simplexes when they are equivalent in meaning. These additional semantic traits may have an influential effect on lexical choice: PVs may be preferred because of the “intensifying/emphasising force” of aspectual particles (Claridge 2000: 237), and this may be functionally linked to the desire to contribute more effectively to the informational exposition in the courtroom. At the same time, pairs which convey a meaning that is conventionalised in the legal domain do not allow a free choice in interaction: for instance, simplexes which incorporate concepts recalling those included in regulations and norms may be used for the sake of formality and the need for precision. This raises questions about the degrees of precision of courtroom discourse and the extent to which vague language was used in the courtroom of the past.

4.2.2 Semantic generality vs. semantic specificity

Examination of the data showed that literal PVs are slightly less frequent than their simplex alternatives, but this difference only amounts to 0.02 percentage points. The two types of verb differ from each other in use, however, as the phraseological form exhibits a higher degree of specificity. When it comes to idiomatic combinations, however, they are significantly less frequent than simplexes but the semantic divergences are not as significant as for literal and aspectual PVs.

Specifically, except for the pair to discover/to find out (62 and 43 occurrences respectively), idiomatic PVs are rather rare and leave space for the predominance of their simplex counterparts. Indeed, in 6 out of 7 pairs,[5] the simplex alternative is far more frequent than the idiomatic PV synonym, which makes evaluation of the divergences very hard if not speculative. Given the diachronic orientation of the present study, the limited occurrence of idiomatic PVs may have to do with processes of conventionalization rendering non-compositional properties gradually more frequent over time: idiomatic instances develop and become widespread within the system only once the new connotation has been conventionalised in use (Brinton and Traugott 2005: 110).

For the sake of completeness, two examples of idiomatic PV/simplex pairs are presented in (25)–(26) and (27)–(28).

Mary Whitfield came to char for us in consequence of what I discovered. (1830s)

I apprehend it was kept at our office, till we could find out the person who offered it. (1750s)

In about half an hour after the bills were distributed. (1810s)

He gave the guns out at the door. (1810s)

Both pairs, to discover/to find out and to distribute/to give out, are synonymous, and comparison reveals no significant divergences. To distribute conveys the meaning of ‘to spread generally, to scatter’ (OED) which overlaps partly with that of to give out, denoting the meaning of ‘to issue; to distribute’ (OED). On the other hand, the verbs to discover and to find out are used with the meaning of ‘to disclose, reveal, etc., to others or (later) oneself; to find out’ and ‘to discover (a fact, some information, etc.)’ respectively (OED) with apparently no noteworthy difference in semantic/pragmatic terms. This is further corroborated by the closeness they bear in terms of both syntactic patterns and context of use:

No more than if Mr Purcell would take such a person up he was sure to discover who had the property. (1790s)

He ordered him back to Staines as a prisoner, and desired the constable to endeavour to find out who the sheep belonged to. (1790s)

Moving on to the literal PVs, instead, something different emerges. Similar to aspectual PVs, literal PVs exhibit pragmatic nuances and the particles work to convey additional traits to the non-pragmatic propositional contents associated with the base verb. The main point of divergence between literal PV/simplex pairs, indeed, lies in their differing degrees of specificity and generality. On many occasions, the phraseological verb strengthens the meaning of the simplex and works as a more precise alternative to it.

This recalls the idea that particles need to be examined separately given their inner semantic power, but also further highlights the role of PVs as “a means of lexical enrichment” (Bolinger 1971: 97). The adverbial particle seems to give further information on the action expressed by the verbs, emphasising the movement of action in space/time, as seen in to come back/to return reported in (31)–(32):

You did not suspect he meant to rob you? – No, I did not. He never came back. (1770s)

I returned home about twenty minutes past four. (1830s)

The phraseological constituency of the literal combination is once again the cutting edge between PVs and simplexes. The particle seems to work as a device giving a further specification of what is said, which is reflected in the fact that, in the majority of instances, the verb is not followed by other elements helping to enrich the action with details. In particular, the particle back itself emphasizes the fact that somebody has returned from somewhere, no matter with whom or whatever the reason may be. On the other hand, the semantic value of the verb to return seems to depend on the immediate context of use, which further specifies the action. For example, to return is frequently used with phrases as to the prisoner, into the city, or to the room, to the house, to the office, as in (33)–(35):

I afterwards returned to the room, stopped there till the male prisoner came. (1830s)

I took him to the station-house, and returned to the house about an hour after making some inquiry at his father’s. (1830s)

I could not find him, and returned to the office. (1790s)

On other occasions, there is also a sense of reiteration in these verbs, which is evident from the immediate context of use, which features the adverb again, as in (36)–(37). This turns out to reveal a further difference between the verb forms:

They very soon after returned again to Mr. Beckwith’s. (1810s)

When he got up and was gone out of doors, he missed his money and came back again. (1750s)

Specifically, as examples (36) and (37) show, both to return and to come back may be followed by the adverb again working as an intensifying factor that provides a sense of reiteration to the action. However, looking at the frequency of use it emerges that again occurs more consistently with the PV: 0.39Nf (18% of all the instances) compared to 0.16 Nf (3.5%) in the case of to return. Thus, the sense of reiteration is more prominent with the PV than with the simplex.

Another aspect worthy of note is that, among the matches where the simplex is followed by again, 9 hits show the combination back again, as in (38)–(39):

I went down to the Key to see if I could earn a sixpence; and I walked down the Key, and was returning back again. (1790s)

He looked earnestly at the window and returned back again. (1810s)

The adverb back turns out to be a specifying element colouring the simplex with extra nuances that further contribute to the description of the features of the denoted action: it means ‘in the opposite direction in space, to return to the place originally left’ (OED). To return can acquire further semantic nuances but only when followed by back or back again, which are in fact “pleonasms [serving] as a valid means of emphasis and intensification” (Claridge 2000: 219). Overall, this means that to come back, while retaining the same connotation, is a more expressive alternative than to return, with back conveying emphasis on the direction and motion which is absent in the simplex.

Similar considerations apply to the pairs to depart/to go away, characterized by very close meaning but divergent nuances. The PV seems to be anchored to a higher degree of specificity and it occurs in contexts that convey specific topological information:

… I went to his Lordship’s house, who gave me an account of some plate, which I did not like, and therefore departed. (1750s)

I left my name and departed. (1770s)

I left it there when I went away at night; the next morning it was gone. (1810s)

Jones as soon as he see I was stopped, turned round the corner, and went away from me. (1790s)

In this case, however, there is no reference to the reiteration of the action as above, rather it seems that the direction and the idea of movement are the focus of discourse. This is corroborated by the fact that the verb to go away is also used followed by prepositional phrases introduced by the preposition from, as in (43), which implies the direction and reinforces the sense of ‘moving to go elsewhere’.

Another pair that makes a case for a different degree of specificity is to remove/to put-take away. In particular, the verbs to remove/to put-take away[6] usually indicate the act of ‘to take elsewhere, to put something out of one’s hands’ (OED). By only selecting cases where these PVs are equivalent in meaning and comparable with to remove, nevertheless, it is possible to note that behind the close semantic relation, they also differ in many respects. Consider examples (44)–(46):[7]

I was removing my goods; the drawers in which the notes were, were removed on the 22d, between twelve and one o’clock. (1790s)

I had occasion to remove some property last November. (1830s)

After he took away his hand from the window that you saw him break, did you see him hand over anything to the man that you saw lurking? (1770s)

Comparing the verbs in these examples shows that substitution of the simplex for the phraseological verb form seems not to affect significantly, at least prima facie, their semantic connotation which is mainly linked to the activity of ‘removing’. The main aspect to note, again, is that the phrasal alternative entails the particle portraying additional semantic information on the action narrated, and it contributes to a shift in focus from the act of removing to the direction of the action. An interesting feature is that to remove is significantly more frequent (59 occurrences) than to take away/to put away in the data (20 occurrences). The reason this pair has been examined in more detail is that it is an exemplary case where linguistic features intertwine with diachronic aspects to determine the overall frequency. The point is that simplexes probably predominated in this period because they were rather conventionalized during the LMod time. Instead, the extant, more specific connotation of to take away gradually started to intensify during the LMod period, when this verb developed new nuances that even interrupted its equivalence to to remove. Indeed, to take away has been shown to have shifted from the meaning of ‘taking’ in the sense of ‘removing’ to that of ‘removing to take elsewhere’, and this renovated meaning became consolidated (Leone 2019: 259–261). The instances conveying the meaning of ‘removing to take elsewhere’ were not included in the overall count but are an interesting example of the process of semantic renewal and increasing divergences within the pairs which can contribute in the long term to a break in the relation of near-synonymy. This is clear when to remove is used in combination with to take away, showing their use with diverse, not overlapping, meanings:

Nothing was taken out; a table-cloth was removed, but not taken away. (1750s)

All this suggests that the possible answer to the question of the differences between simplex and phraseological synonyms could be that PVs possess a greater degree of specificity but are also more emphatic. Although they access the same semantic domain, compared with simplexes, PVs elicit additional features to the factual reconstruction of crimes, which may explain the lexical choice made by speaker in some cases. This fits well with the idea that “if we want to fully account for what the language is doing or what the speaker is doing through use of language, we have to take account of the context of use and the linguistic choices that are made” (Coulthard and Johnson 2007: 68).

Overall, the similar frequency of simplexes and PVs, including literal PVs, may be seen as a sign of speakers’ sensitivity to the use of lexis according to communicative purposes. At the same time, it further contributes to the conceptualization of legal-lay discourse of the LModE period as a genre where lexical choice is also driven by contextual aspects concerning actions and events narrated in a courtroom setting.

5 Concluding remarks

Analysis of the data revealed a gradual increase in the use of simplexes over time, which may be seen as an important factor confirming the shift in the language of trials during the LModE, towards decolloquialization as shown in other works (Rodríguez-Puente 2016: 69–97). The results indicate that some PVs were used interchangeably with their simplex alternatives, while others, which belong to the legal domain, did not permit free choice by speakers. In both cases, due to their phraseological status, PVs are a more expressive alternative to their simplex synonym. In the setting of the courtroom, the tendency to use PVs suggests the characterization of legal-lay discourse in the LModE period as a genre where lexical choice serves the purpose of exposition of information on crimes.

The results obtained to date are far from being exhaustive and highlight the necessity for further research. In future work, the period under investigation will be extended to include the beginning of the 20th century, in order to consider other relevant pairs. The focus will also be expanded to sociolinguistic aspects to evaluate the differences between the speech of lay people and that of legal practitioners (defendant, judge, victim, witness, etc.).

References

Akimoto, Minoji. 1999. Collocations and idioms in Late Modern English. In Laurel J. Brinton & Minoji Akimoto (eds.), Collocational and idiomatic aspects of composite predicates in the history of English, 207–238. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/slcs.47.65akiSearch in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Edward Finegan. 1992. The linguistic evolution of five written and speech-based English genres from the 17th to the 20th centuries. In Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen & Irma Taavitsainen (eds.), History of Englishes. New methods and interpretations in historical linguistics, 688–704. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110877007.688Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Susan Conrad. 2009. Register, genre, and style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511814358Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Susan Conrad & Randi Reppen. 1998. Corpus linguistics. Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511804489Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad & Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.Search in Google Scholar

Bolinger, Dwight. 1971. The phrasal verb in English. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. & Elizabeth Closs Traugott. 2005. Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511615962Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. 1988. The development of English aspectual systems. Aspectualizers and post-verbal particles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel J. 1996. Attitudes toward increasing segmentalization. Complex and phrasal verbs in English. Journal of English Linguistics 24(3). 186–205.10.1177/007542429602400304Search in Google Scholar

Claridge, Claudia. 2000. Multi-word verbs in Early Modern English. A corpus-based study. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.10.1163/9789004333840Search in Google Scholar

Coulthard, Malcolm & Alison Johnson. 2007. An introduction to forensic linguistics. Language in evidence. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Cowie, Anthony Paul. 1988. Stable and creative aspects of vocabulary use. In Ronald Carter & Michael McCarthy (eds.), Vocabulary and language teaching, 126–137. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Cowie, Anthony Paul. 1998. Introduction. In Anthony Paul Cowie (ed.), Phraseology: Theory, analysis and applications, 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198294252.003.0001Search in Google Scholar

Crystal, David & Derek Davy. 1969. Investigating English style. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Culpeper, Jonathan & Merja Kytö. 2010. Early Modern English dialogues. Spoken interaction as writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Curme, George O. 1931. A grammar of the English language in three volumes. Vol. III. Syntax. Boston: D. C. Heath and Company.Search in Google Scholar

Dixon, Robert Malcolm Ward. 1982. The grammar of English phrasal verbs. Australian Journal of Linguistics 2(1). 1–42.10.1080/07268608208599280Search in Google Scholar

Fraser, Bruce. 1974. The verb-particle combination in English. Tokyo: Taishukan Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Gavins, Joanna. 2007. Text World Theory: an introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.3366/edinburgh/9780748622993.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Goźdź-Roszkowski, Stanislaw. 2013. Exploring near-synonymous terms in legal language. A corpus-based, phraseological perspective. Linguistica Antverpiensia. New Series – Themes in Translation 12. 94–109.10.52034/lanstts.v0i12.236Search in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan Th. 2008. Phraseology and linguistic theory: A brief survey. In Sylvian Granger & Fanny Meunier (eds.), Phraseology. An interdisciplinary perspective, 3–25. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/z.139.06griSearch in Google Scholar

Hampe, Beate. 2002. Superlative verbs. A corpus-based study of semantic redundancy in English verb-particle constructions. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Heffer, Chris. 2005. The language of jury trial. A corpus-aided analysis of legal-lay discourse. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.10.1057/9780230502888Search in Google Scholar

Hiltunen, Risto. 1994. On phrasal verbs in Early Modern English: Notes on lexis and style. In Kastovsky Dieter (ed.), Studies in Early Modern English, 129–140. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110879599.129Search in Google Scholar

Hiltunen, Risto. 1999.Verbal phrases and phrasal verbs in Early Modern English. In Laurel J. Brinton & Minoji Akimoto (eds.), Collocational and idiomatic aspects of composite predicates in the history of English, 133–165. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/slcs.47.45hilSearch in Google Scholar

Huber, Magnus, Magnus Nissel & Karin Puga, 2016. The Old Bailey Corpus 2.0, 1720–1913. Manual. https://www.fedora.clarin-d.uni-saarland.de/oldbailey/downloads/OBC_2.0_Manual%202016-07–13.pdf (accessed 25 March 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Huber, Magnus. 2007. The Old Bailey Proceedings, 1764–1834. Evaluating and annotating a corpus of 18th- and 19th-century spoken English. In Anneli Meurman-Solin & Arja Nurmi (eds.), Annotating Variation and Change (Studies in Variation, Contacts and Change in English 1). Helsinki: University of Helsinki. https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/01/huber/ (accessed 08 November 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Arthur Garfield. 1920. The modern English verb-adverb combination. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kjær, Anne Lise. 1994. Zur kontrastiven Analyse von Nominationsstereotypen der Rechtssprache deutsch-dänisch. In Barbara Sandig (ed.), EUROPHRAS 92. Tendenzen der Phraseologieforschung, 317–348. Bochum: Universitätsverlag Brockmeyer.Search in Google Scholar

Kjær, Anne Lise. 1995. Vergleich von Unvergleichbarem. Zur kontrastiven Analyse unbestimmter Rechtsbegriffe. In Hans-Peder Kromann & Anne Lise Kjær (eds.), Von der allgegenwart der lexikologie. Kontrastive Lexikologie als Vorstufe zur zweisprachigen Lexikographie, 39–56. Tübingen: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110938081.39Search in Google Scholar

Kjær, Anne Lise. 2007. Phrasemes in legal texts. In Harald Burger, Dmitrij Dobrovol’skij, Peter Kühn & Neal R. Norrick (eds.), Phraseologie: ein Internationales Handbuch der Zeitgenössischen Forschung. Vol. I, 506–515. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110171013.506Search in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard. 1973. Englische Syntax. Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum Fischer.Search in Google Scholar

Leone, Ljubica. 2019. Context-induced reinterpretation of phraseological verbs. Phrasal verbs in Late Modern English. In Gloria Corpas Pastor & Ruslan Mitkov (eds.), EUROPHRAS 2019, LNAI vol. 11755, 253–267. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-30135-4_19Search in Google Scholar

McArthur, Tom. 1989: The long-neglected phrasal verb. English Today 5(2). 38–44.10.1017/S026607840000393XSearch in Google Scholar

Mel’čuk, Igor. 1998. Collocations and lexical functions. In Anthony Paul Cowie (ed.), Phraseology, theory, analysis, and applications, 23–53. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198294252.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

OBC. The Old Bailey Corpus. https://fedora.clarin-d.uni-saarland.de/oldbailey/ (accessed 30 June 2020).Search in Google Scholar

OED. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com.Search in Google Scholar

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech & Jan Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Harlow: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Rodríguez-Puente, Paula. 2016.Tracking down phrasal verbs in the spoken language of the past: Late Modern English in focus. English Language and Linguistics 21(1). 69–97.10.1017/S1360674316000095Search in Google Scholar

Rodríguez-Puente, Paula. 2019. The English phrasal verb, 1650–present. History, stylistic drifts, and lexicalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316182147Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John. 1991. Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, John. 1994. Trust the text. In Malcolm Coulthard (ed.), Advances in written text analysis, 12–25. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Smitterberg, Erik. 2008. The progressive and phrasal verbs: Evidence of colloquialization in nineteenth-century English? In Terttu Nevalainen, Irma Taavitsainen, Päivi Pahta & Minna Korhonen (eds.), The dynamics of linguistic variation. Corpus evidence on English past and present, 269–289. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/silv.2.21smiSearch in Google Scholar

Stubbs, Michael. 2002. Words and phrases. Corpus studies of lexical semantics. Malden & Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Szczyrbak, Magdalena. 2017. Verba dicendi in courtroom interaction. Patterns with the progressive. In Stanislaw Goźdź-Roszkowski & Gianluca Pontrandolfo (eds.), Phraseology in legal and institutional settings. A corpus-based interdisciplinary perspective, 240–257. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315445724-14Search in Google Scholar

The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/ (accessed 27 July 2019).Search in Google Scholar

Thim, Stefan. 2012. Phrasal verbs. The English verb-particle construction and its history. Berlin & Boston: Walter de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110257038Search in Google Scholar

Tiersma, Peter. 1999. Legal language. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tiersma, Peter. 2008. The nature of legal language. In John Gibbons & Teresa M. Turell (eds.), Dimensions of forensic linguistics, 7–25. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Tognini Bonelli, Elena. 2002. Functionally complete units of meaning across English and Italian: Towards a corpus-driven approach. In Bengt Altenberg & Sylviane Granger (eds.), Lexis in contrast: Corpus-based approaches, 73–95. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/scl.7.07togSearch in Google Scholar

Visser, Frederick T. 1963. A historical syntax of the English language. Vol. I. Leiden: Brill.Search in Google Scholar

Widlitzki, Bianca & Magnus Huber. 2016. Taboo language and swearing in Eighteenth-and-Nineteenth century English: A diachronic study based on the Old Bailey Corpus. In María José López-Couso, Belén Méndez-Naya, Paloma Núñez-Pertejo & Ignacio M. Palacios-Martínez (eds.), Corpus linguistics on the move. Exploring and understanding English, 313–336. Leiden & Boston: Brill Rodopi.10.1163/9789004321342_015Search in Google Scholar

Wild, Kate. 2010. Attitudes towards English usage in the Late Modern period: The case of phrasal verbs. Glasgow: University of Glasgow Ph.D. thesis.Search in Google Scholar

WordSmith Tools 6.0. https://lexically.net/publications/citing_wordsmith.htm (accessed 30 June 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Zhenhua, Wang. 2016. Legal discourse: An introduction. Linguistics and the Human Sciences 12(2–3). 95–99. https://journals.equinoxpub.com (accessed 22 May 2019).10.1558/lhs.36987Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Ljubica Leone, published by De Gruyter, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews