Abstract

When looking at expressions of negation/rejection in Spanish, the conjunction ni is one of the most prolific words. However, the extent of locutions employing ni has not been widely analyzed. For this reason, we conducted a comparative descriptive examination of discourse markers of rejection and refusal for three different dialectal variants of Spanish: those of Spain, Colombia and Mexico. The participants completed a survey to evaluate their familiarity with some of these pragmatic expressions and to provide new ones. Results show that speakers of these dialectal variants all use the most common markers that start with ni, but also other phrases not recorded in many of the available sources. This paper aims to broaden the horizon of work on phraseological units of negation, which are often difficult to gather and study in depth because of their dialectal variability, colloquial use, and, in some cases, short lifespan.

1 Introduction and theoretical framework

1.1 Phraseology and discourse markers

Penadés (2012) refers to the field of phraseology by stating that:

En las lenguas existen combinaciones de palabras en cuya utilización el hablante carece de libertad para alterar o modificar la sucesión de elementos y para variar los propios elementos que constituyen la combinación.

Phraseology embraces a wide variety of elements, including collocations, locutions and sayings. Among them are also some discourse markers, sufficiently grammaticalized expressions that operate on the pragmatic level. Described by Schiffrin (1987: 32) as “sequentially dependent elements which bracket units of talk”, their form varies greatly: some discourse markers consist of only one word. For instance, in Spanish, the words bueno or pues, are the focus of several in-depth pragmatic studies.[1] However, a very broad group of discourse markers formed by two or more words, intersects with the field of phraseology. Ruiz Gurillo (2010: 176) explains this intersection, referring specifically to Spanish, but his observation is equally applicable to other languages:

Es previsible que, tras una fase intermedia, diversos complementos circunstanciales se gramaticalicen como marcadores del discurso de diversos tipos (…). Algunos de ellos son de carácter complejo, es decir, se definen como unidades fraseológicas.[2]

Corpas (1996) includes a large number of discourse markers in her book Manual de Fraseología Española, mostly under the “locutions” and “routine formulas”[3] sections. Ruiz Gurillo (2001: 45–46) includes a “marker locution” in her organization. However, García-Page (2008: 89) highlights that there are several groups of locutions, not only one, that have a purpose in discourse. There is, therefore, a meeting point where the study of discourse markers and the study of phraseology converge.

Phrases of rejection of a proposition or a statement, such as the ones that start with ni, the focus of this paper, are certainly a part of this group. The word ni has been studied in grammar and discourse studies as a polyvalent particle with scalar value. As Martí (1998: 79) points out, it is not enough to say that it functions as a conjunction that links negative members. The author differentiates the conjunction ni from a modal particle ni. Albelda Marcos and Gras (2011) focus on the discursive value and the scalarity[4] of the word, including a function to introduce a negative answer as a response to a previous intervention while providing an example with the adverbial phrases ni hablar, ni pensarlo, ni soñarlo and ni borracho. Although we do not focus on the scalarity structure in this paper, it constitutes the basis for the continuous creation of new expressions, especially non-canonical ones in negation (Amaral and Schwenter 2009).

1.2 Phrases of negation and rejection

This work focuses on the functions of rejection/negation/refusal/disagreement[5] and the phrases speakers use to express them. There is a wide variety of forms for saying “no” to a statement, a suggestion or a question. In Spanish, some common ones are formed with the conjunction ni followed by an infinitive, like in ni hablar; by a noun phrase, like in ni en sueños; by an adjective, like in ni loco; and sometimes by a verbal phrase, like in ni lo pienses. As Pérez-Salazar (2017: 270) points out:

La renovación de secuencias se produce, en algunos casos, sobre la base sintáctico- semántica de ciertas estructuras; es decir que el español aprovecha modelos fraseológicos para crear fórmulas nuevas (…). Así, puede hablarse, en diacronía, de patrones productivos.

Most of these ni sequences are prototypical of informal speech.[6] They are considered slightly impolite, and are less studied than other discourse markers, for instance, those used in accepting a proposal or making a statement.[7] The context of informal ni expressions is usually a spontaneous conversational dialog, as Holgado Lage and Rojas point out in reference to ni hablar (2016). Fuentes Rodríguez mentions that this particular marker absolutely rejects what another interlocutor said (2009: 226), nevertheless, Holgado Lage and Rojas found that it can also work in a monolog (2016: 114). These contexts also naturally host other ni expressions that have become phraseological units (Pérez-Salazar 2009: 38):

Una vez alcanzada esta condición es mi intención mostrar que han adquirido la capacidad de negar expresivamente constituyendo por sí solas un enunciado (esto es, como enunciados fraseológicos) o bien como elementos oracionales, rasgo éste que se tiene como propio de las locuciones.

When looking at the current literature on expressions of negation with ni, the phrase that appears most regularly is ni hablar and some of its variants. This very common marker is the focus of study in Holgado Lage and Rojas (2016), who, in addition to the habitual function, analyze the marker as a positive response (showing acceptance) in Río de la Plata. Frequently, ni hablar is the only ni phrase recorded in general linguistic works such as Casamiglia and Tuson Valls (1999: 239), Perona (2000: 450) or Landone (2009: 287). In Corpas (1996: 196), the same expression is mentioned along with the variant ni hablar del peluquín, which is falling into disuse.[8]

Some works are a little broader and incorporate other rejection phrases besides the ubiquitous ni hablar. One of the seminal articles in rejection locutions in Spanish, by Pérez-Salazar (2009), analyzes the historical process through which some ni combinations became phraseological units. The author focuses on three particular locutions: Ni hablar, ni pensar, and ni soñar. The same author (Pérez-Salazar 2017) studies negation expressions diachronically, focusing on sequences that are productive, including ni en sueños, ni pensar, ni por lumbres, ni por asomo, and ni por el forro. Ni hablar is also the most detailed ni expression in Santos Río (2003). Olza (2011) studies some phrases of rejection, including ni qué narices, which also starts with ni but requires a different syntactic structure, since it needs to be preceded by the actual object that is being rejected.

Some sources do not incorporate any locutions that start with ni. For instance, Martín Zorraquino and Portolés (1999), contribute to the field with one of the original lists of discourse markers in Spanish, but do not provide expressions of rejection. Their work includes, however, some of the opposite function, for instance desde luego, por supuesto or claro. The Diccionario de Partículas Discursivas del Español[9] (Briz, Pons and Portolés 2004) also does not focus on the function of rejection.

However, there are some other dictionaries of Spanish discourse markers that include a higher number of expressions of rejection.[10] Fuentes Rodríguez (2009) records a list similar to the one mentioned by Pérez-Salazar (2009): ni hablar (del peluquín), ni pensarlo, ni soñarlo. In Holgado Lage (2017) there is a longer list of ni phrases: ni de broma/coña, ni en sueños, ni pensarlo, ni por todo el oro del mundo, ni loco/a, ni soñarlo, ni hablar. Seco et al. (2004) include an ample repertoire of ni expressions in their Diccionario Fraseológico Documentado. Not all of them can be included in the group that is pertinent to this study.[11] The list of expressions that follow the productive pattern used to strongly reject what was said before includes: ni amarrado, ni atado, ni de coña, ni en broma, ni en sueños, ni hablar, ni hablar de eso, ni hablar del asunto, ni hablar del peluquín, ni lo pienses, ni lo sueñes, ni loco, ni pensarlo, ni por broma, ni por pienso, ni por sueños, ni por todo el oro del mundo and ni soñarlo. This is the most exhaustive list we have found in the literature.

Two of the most relevant general dictionaries of Spanish were also consulted, since they are the tool that most speakers would use if they wanted to find a locution. A search in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española (Real Academia Española 2014) shows that there is not one expression of rejection under the word ni.[12] However, one can find some of these locutions when looking by the most relevant word. For instance, ni hablar under “hablar”, ni pensarlo under “pensar”, ni soñarlo under “soñar”, ni en sueños/ni por sueños under “sueño”, ni de broma/ni en broma under “broma”, ni loco under “loco”, ni de coña under “coña”, ni borracho under “borracho” or ni de fundas under “fundas”. It is difficult to know if there are others included (for instance, some outdated ones that are not widely used, or some regional ones) since they are not grouped together anywhere within the dictionary. The second-most renowned general dictionary of Spanish, Diccionario de Uso (Moliner 1966: vol. 2, 507), includes several expressions under the definition of ni: ni por mientes, ni pensarlo, ni por pienso, ni por sombra, ni soñarlo, ni lo sueñes, ni en sueños. And it adds that there might be other ones not included in the list.

While none of the sources mentioned incorporates every one of these expressions[13] – an arduous task, anyhow, since they are constantly appearing (García-Page 2008: 120) – this is also not the main objective of most of them.

2 Research justification and questions

As pointed out in the introduction, a relatively small number of sources incorporate a large number of ni expressions. It would be a complicated task to unify all the ni locutions because of the variability of these phrases (some of them have a very short lifespan), and the orality of the function of negation/rejection.

Given the linguistic relevance of recording and studying these popular markers, and the fact that there are no studies that compare their use in different dialectal variants, we conducted fieldwork[14] in three different geographical areas – Spain, Mexico and Colombia – in order to describe their diatopical variation based on the collected data. The Peninsular variety has been vastly researched, sometimes due to the nationality of the researchers, so the decision was to contrast it with other varieties. The following are the main questions that we were hoping to answer in relation to the usage and the variation of the locutions in these three different dialectal variants:

What expressions with ni are produced and accepted in these three different varieties of Spanish?

Are these expressions often recorded and analyzed in the sources?[15]

Is ni hablar widely used, since it appears frequently in the literature?

Do the sources include expressions from several dialectal variants of the Spanish language?

Does the use of new ni expressions vary depending on the age of the speakers?

Our general hypothesis was that there is a group of ni phrases that are known and frequently used in these three varieties of Spanish but that have been overlooked in the studies, maybe because mostly younger speakers use them in oral interactions. We expected to encounter ni hablar highly frequently in every dialectal variant, and we wanted to contrast the ni expressions from our study with the ones found in the bibliographical sources.

3 Methodology

In order to answer these questions, confirm our hypotheses and reach our objective of broadening the horizon of work on phraseological units of negation, we designed a survey for native speakers of Spanish. The aim was to verify their level of familiarity with some expressions of rejection/negation, while obtaining data about other phrases that the sources did not include. After reviewing the existing literature, we reached the conclusion that it was necessary to add more discourse markers to the survey, so we consulted with competent native Spanish-speakers, to create our own inventory. The list could have been more extensive but we considered that the selection we settled on, including several ni expressions, is representative in the majority of the Spanish-speaking world. Participants were also encouraged to provide new phrases that were not part of the main selection.

The fieldwork was conducted during the Spring/Summer of 2017.[16] Participants (N=223) were adults from three different Spanish speaking countries and they were required to answer some questions, via the anonymous survey, about their use of discourse markers of rejection/negation (a total of eighteen, nine of them ni expressions). Initially participants were recruited through contacts in the selected countries, but eventually more participants were needed from some age groups, so the researchers resorted to campaigning in person in the three countries, mostly around the capital areas: Madrid, Mexico City and Bogota, and handing out the surveys on hardcopy. Afterwards, the results were uploaded manually to the survey system that stored the data from the ones completed online. The goal was to be able to analyze all of the data together. By the time the research was completed, the participants were distributed by country as shown in Tab. 1.

Distribution of participants by country

| Country | Number of participants | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | 90 | 40.36% |

| Mexico | 66 | 29.60% |

| Colombia | 67 | 30.04% |

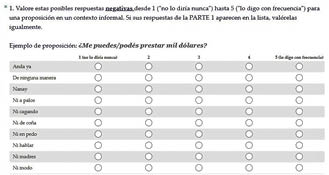

The survey consisted of two parts: In the first, participants evaluated some negation/rejection markers from 1 (I wouldn’t use it) to 5 (I use it frequently). Nine of the expressions started with ni but, as explained above, there were other markers of negation to respond negatively to a proposal, invitation, question or suggestion, in an informal context. An example was provided in order to guide the participants. The restriction of the context was important, as some of these phrases are not considered “polite” in a formal context, a few are even curse words in some dialectal variants. In Fig. 1 there is an extract of this first part of the survey.[17]

Screenshot of first part of the survey

This extract contains some negative expressions, including several that include ni. Some of them were rated very low in every dialectal variant considered in this study[18] so they are not included in the results.[19] The locutions that are pertinent for this study are the following six:

Ni de coña

Ni en pedo

Ni hablar

Ni madres

Ni modo

Ni pensarlo

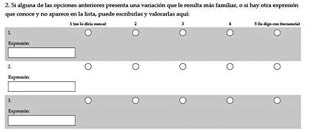

In the second part of the survey, participants had the opportunity to provide variations of the markers above or new locutions that were not listed. Also, they were expected to provide an evaluation of those expressions. There was an option to include three of these variations, as seen in Fig. 2.

Screenshot of second part of the survey

Logically, the participants rated most of the phrases they provided at the highest value. This part of the survey resulted in a list of very innovative expressions that had not been registered before[20] and will AU: Please provide better quality figurebe analyzed in Section 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4. We also looked at the age and gender of the participants providing these new varieties to see if there was a pattern, as summarized in Section 4.5.

4 Results

4.1 General results

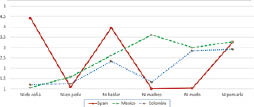

First, we analyzed the ni expressions that appeared in the general survey, contrasting the three varieties. We were expecting to see a preference for some discourse markers above others in the dialectal variants. Fig. 3 shows the average value for each expression (1–5) on the vertical axis. As can be seen, there was a lot of variation between dialectal variants.

Frequency of ni expressions from the survey in the three different varieties

For example, the Peninsular Spanish speakers demonstrate a high level of comfort with ni de coña (value 4.42), and ni hablar (value 3.96). These are the highest values given to any marker in the three dialectal variants, as can be seen in Fig. 3. Ni de coña is rejected by the other two dialectal variants (Mexico 1.07 and Colombia 1.21). The answers from Spain attribute the lowest possible value to ni madres (1) and to ni modo (1.03). The most neutral phrase, according to the chart, would be ni pensarlo, as the three groups of participants all rated it high (3.27 Spain, 3.27 México and a little higher, 2.92 in Colombia). The one phrase that is not known or used on a regular basis by any of the dialectal variants is ni en pedo (rated 1.08 in Spain, 1.58 by the Mexican participants[21] and 1.25 in Colombia).

Ni hablar, although it appeared in almost every source that included ni expressions, and many times was the only one, is not the most preferred expression in any of the dialectal variants, with Mexico rating it at 2.63 and Colombia at 2.35. Ni madres is the most preferred phrase in Mexico (3.62), with a low value in both Spain and Colombia (1.33). Ni modo is given a high value in both Mexico (3.00) and Colombia (2.85), but not as high as others are. This might be because although sometimes used for rejection, the main function of the marker is to express acceptance with resignation, so it is possible that for many speakers, answering ni modo to the example given did not fully mean a strong rejection, as the other expressions did.[22]

In Tab. 2 there is a summary of the values given to every item in the three countries.

Average values given by participants

| Marker/Country | Spain | Mexico | Colombia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni de coña | 4.42 | 1.07 | 1.21 |

| Ni en pedo | 1.08 | 1.58 | 1.25 |

| Ni hablar | 3.96 | 2.63 | 2.35 |

| Ni madres | 1.00 | 3.62 | 1.33 |

| Ni modo | 1.03 | 3.00 | 2.85 |

| Ni pensarlo | 3.27 | 3.27 | 2.92 |

One of the most innovative features of the survey was the opportunity for participants to provide new expressions that were not part of the original list and that they know or use on a regular basis. The differences between dialectal variants were conspicuous as shown in the next three sections.

4.2 Results by country: Spain

As seen in Fig. 3, the prototypical ni expression for the Peninsular dialectal variant is ni de coña (value 4.42), with ni hablar and ni pensarlo ranked really high as well. This is interesting as ni de coña was not listed in most of the sources consulted[23]. The reason could be that it is slightly vulgar. Participants from Spain provided seven different new ways to reject a proposition like the one given as an example. In Tab. 3 is a list of how many times they appear in the results:

New expressions provided by participants from Spain

| Expression | Number of times | Age of participants[24] |

|---|---|---|

| Ni lo sueñes | 2 | 35–44, 55–64 |

| Ni loco/a | 2 | 25–34, 25–34 |

| Ni en sueños | 1 | 35–44 |

| Ni harto/a a vino | 1 | 45–54 |

| Ni borracho/a | 1 | 25–34 |

| Ni lo pienses | 1 | 25–34 |

| Ni de palo | 1 | 25–34 |

As seen in the chart, the phrases ni lo sueñes / ni en sueños (very similar variations) are the most popular, with three instances in total, followed by ni loco/a. Both of these locutions appear in some of the sources consulted.

4.3 Results by country: Mexico

Mexican speakers follow a very similar pattern to that described in 4.2. There is a prototypical expression, ni madres (value 3.62) ranked much higher than in the other two countries. Ni modo also had a high rate[25] along with ni pensarlo. The locution ni en pedo was rated much lower than expected, only 1.58, but another variation was provided three times, as shown in Tab. 4, along with the other new phrases recorded by speakers of the Mexican variety.

New expressions provided by participants from Mexico

| Expression | Number of times | Age of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Ni loco/a | 3 | 45–54, 45–54, 35–44 |

| Ni de pedo | 3 | 35–44, 35–44, 35–44 |

| Ni en broma | 2 | 25–34, 25–34 |

| Ni de broma | 1 | 35–44 |

| Ni sueñes | 1 | 45–54 |

| Ni soñando | 1 | 35–44 |

| Ni de loco/a | 1 | 55–64 |

| Ni borracho/a | 1 | 35–44 |

| Ni de chiste | 1 | 25–34 |

| Ni de desmadre | 1 | 45–54 |

As shown above, some of the answers are very similar to the ones in Peninsular Spanish, especially ni loco/a or ni de loco/a (4 instances in total) and the variations ni sueñes and ni soñando (2 instances in total). Some new discourse markers that do not appear in the other two dialectal variants are ni de pedo (3 instances), which also did not appear in any of the sources, and ni en broma/ni de broma (2 instances).

4.4 Results by country: Colombia

The data collected from participants in Colombia are slightly different from those collected in the other two countries. It appears that there is no prototypical expression generally used in the Colombian area that is valued significantly lower in the other two varieties. Ni pensarlo and ni modo have relatively high values, but at 2.92 and 2.85 they are far from the highest-rated locutions in Spain and Mexico, plus they are also highly accepted in the other two countries. This lack of a high-rated marker translates into a higher rate of responses for expressions that were not a part of the main list: ten additional phrases were provided, some of them similar to the ones from Mexico and Spain, some of them completely new. In Tab. 5 the complete list is included:

New expressions provided by participants from Colombia

| Expression | Number of times | Age of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Ni loco/a | 4 | 25–34, 25–34, 25–34, 55–64 |

| Ni de fundas | 2 | 25–34, 55–64 |

| Ni en sueños | 2 | 25–34, 18–24 |

| Ni a bate | 1 | 35–44 |

| Ni a palo | 1 | 25–34 |

| Ni po’el putas | 1 | 55–64 |

| Ni puel | 1 | >65 |

| Ni de riesgo | 1 | 25–34 |

| Ni en joda | 1 | 18–24 |

| Ni se te ocurra[26] | 1 | 55–64 |

The most common locution provided was ni loco/a (4 instances) which was also used in the other two countries. Ni de fundas appears twice, as does ni en sueños. The latter phrase also appeared in the results from Spain and some variations that included the word verb soñar[27] were recorded in Mexico. However, seven of these expressions only appear in the Colombian surveys (eight if we include ni a palo, for which there is a very similar variety, ni de palo, in Spanish from Spain), which might be an indication of the wide variety of options that the speakers can choose from. This also provides an explanation for the lack of a prototypical phrase that is highly rated in the survey by most speakers.[28]

4.5 Age and gender of participants

4.5.1 Age

One of our research questions was whether the age of the participants was a relevant factor when providing new expressions, since there is a link between young age and innovation in language.[29] On analyzing the data, we found ten new locutions[30] that did not appear in the bibliography or the first part of the survey. Most of them were recorded in Colombia and Mexico.[31] The list includes: ni de palo (Spain), ni de chiste (Mexico), ni de desmadre (Mexico), ni a bate (Colombia), ni a palo (Colombia), ni po’el putas (Colombia), ni puel (Colombia), ni de riesgo (Colombia), ni en joda (Colombia) and ni se te ocurra (Colombia). While it was of great interest to analyze the speakers’ age and gender, the results did not match our hypothesis.

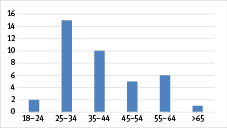

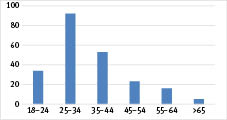

Fig. 4 shows participants per age group who provided new expressions. Thirty-nine participants included some ni expressions in the optional second part of the survey:

Age of participants providing new ni expressions

Only two of the participants were younger than 25 years old, with most of the speakers in the 25–34 and 34–44 sections. While this did not match the proposed theory, the numbers match the age distribution of the entire pool of participants, as seen in Fig. 5:

Age of participants, total

It seems that the participants that decided to provide new expressions with ni were a similar small percentage from every age group.[32] The only exception would be the 55–64 age group. The percentage is slightly higher among the participants that provided new locutions (15%) than among the general pool of participants (7%). Therefore, there is not a reliable age group that provides a higher number of new markers, but every range of age included some participants that took the time to fill out the second part of the survey and were familiar with some ni expressions that were not included in the original list.

4.5.2 Gender

Similarly, the gender of the participants that provided new expressions did not affect our results. In both the total number of respondents and the ones that included new markers, there are more female answers than male. The percentage varies slightly but the difference is not too great, as seen in Tab. 6.

Gender of participants

| Number of participants | Gender | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providing new answers | Male | 16 | 41% |

| Female | 23 | 59% | |

| Total participants | Male | 76 | 34% |

| Female | 147 | 66% | |

5 Discussion

As presented in the Section 2 of the current study, one of the main objectives of this fieldwork was to record a number of expressions of negation (for instance to refuse a proposal, question or suggestion) that start with the particle ni, usually followed by either a noun phrase, adjective or infinitive.[33] Furthermore, we wanted to know how familiar speakers were with some of these existing phrases.

In order to answer the first research question (what expressions with ni are produced and accepted in these three different varieties of Spanish?), we looked at both the evaluation of some markers by speakers of Peninsular, Mexican and Colombian Spanish and the new locutions that they were given the option to incorporate into the form. Results show that preferences vary greatly depending on the geographical area. For instance, in Spain the preferred expressions are ni hablar and ni de coña, in Mexico they are ni madres and ni modo, and in Colombia they are ni pensarlo and ni modo although these were not rated as highly as those preferred in the other two countries. In all three countries, participants included ni loco/a and a phrase or two that included the verb soñar or the noun sueños,[34] along with others, sometimes related to being drunk.[35]

This list leads towards the second question we wanted to answer – are these expressions often registered and analyzed in the best-known sources? – and confirms our hypothesis that there are several ni expressions that were not in any of the inventories of discourse markers of negation consulted in the bibliography. One of the new phrases, ni de pedo, was mentioned more than once in the survey results.

Since ni hablar is the expression that appears in most of the sources consulted for this work, we wanted to examine the extent of its use. Ni hablar had remarkably high scores in Spanish from Spain, but the results were not as strong in Colombian and Mexican Spanish (although most speakers seem to be familiar with it). Taking into consideration that many of the sources mentioned in the Section 1.2 were written and published in Spain, it is logical that it is the one listed with the most frequency. However, it would be useful to include the main ni markers from other dialectal variants in the list to be more linguistically inclusive and adopt a more panhispanic approach. It would also be more sociolinguistically accurate and would help other fields, like Spanish as a Second Language, with a more diverse range of options for the students to choose from when learning these functions.

One of the questions introduced a comparison between the sources consulted and the results from the survey: by looking at the prototypical discourse markers from every dialectal variant, plus the ones provided by the speakers, we could get an idea of whether the sources are representative of several varieties. Results show that most phrases used in the Peninsular variety are included with one noteworthy exception: ni de coña, the preferred phrase for speakers from Spain. This is not found in hardly any of the sources consulted. Conversely, when looking at the locutions provided by Peninsular Spanish speakers, like ni lo sueñes, ni harto/a a vino, ni lo pienses, they make some appearances in the sources consulted, whereas very few of the locutions provided by speakers of Mexico and Colombia are included. Furthermore, the main Mexican marker, ni madres,[36] did not appear in any of the specialized works.

Results pertaining to our last question (does the use of new ni expressions vary depending on the age of the speakers?) did not confirm our hypothesis that young speakers would be the ones providing new example of these markers. In reality, a small percentage from every age range provided new ni phrases, corresponding almost identically with the general distribution by age, so it seems that the whole population is aware of the use of these less common negation phrases, regardless of their age.

6 Conclusion

This study is an initial approach to an ongoing dilemma, which is the recording of innovative discourse markers that represent informal oral language variety of the population of a place in a particular moment in time. One of the obstacles is the difficulty of obtaining oral data, usually done by recording interviews and transcribing them. However, the main setback is probably the brief duration of some of these phrases, sometimes as short as one generation. The focus of this paper specifically is the extension of the usage of phrases that start with ni in Spanish, for instance, ni hablar, to show an effusive–sometimes even not polite–rejection to a proposal, suggestion, statement or question.

After reviewing the existing literature on refusal utterances, we reached the conclusion that many common initiators had not been included. Ni hablar was the marker appearing in most of the sources, often the only one, and sometimes along with the variation ni hablar del peluquín.[37]

For this reason, we decided to create an online survey[38] that included several expressions starting with ni. We sent it to native speakers from Spain, Colombia and Mexico, with 223 of the solicited participants completing the form. Results show that ni hablar is known in all of the three countries but not used to the same degree. Ni de coña is the preferred one in Spain, ni madres in Mexico and ni pensarlo (also used in the other two dialectal variants) in Colombia. Furthermore, participants provided 23 new ni expressions that were not a part of the first section of the survey, some of them repeated in more than one dialectal variant. Most of these were not registered in the main sources consulted, especially the phrases produced in Mexico and Colombia.[39]

The analysis of the results shows the current need for further studies on these discourse markers to give a better overview of the way the different dialectal variants of Spanish function in informal oral situations. Such data would be of relevance to several fields, including the field of phraseology.

References

Albelda Marco, Marta & Pedro Gras. 2011. La partícula escalar ni en español coloquial. In Ramón González Ruiz & Carmen Llamas Saíz (eds.), Gramática y discurso. Nuevas aportaciones sobre partículas discursivas del español. 11–30. Pamplona: EUNSA.Search in Google Scholar

Amaral, Patricia & Scott A. Schwenter. 2009. Discourse and scalar structure in non-canonical negation. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 35(1). 367–378.10.3765/bls.v35i1.3625Search in Google Scholar

Briz, Antonio, Salvador Pons & José Portolés (coords.). 2004. Diccionario de partículas discursivas del español. www.dpde.es (accessed 3 December 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Calsamiglia Blancafort, Helena & Amparo Tusón Valls. 1999. Las cosas del decir. Manual de análisis del discurso. Barcelona: Ariel.Search in Google Scholar

Corpas, Gloria. 1996. Manual de fraseología española. Madrid: Gredos.Search in Google Scholar

Fuentes Rodríguez, Catalina. 2009. Diccionario de conectores y operadores del español. Madrid: Arco/Libros.Search in Google Scholar

Fuentes Rodríguez, Catalina. 2016. Los marcadores de límite escalar: argumentación y ‘vaguedad’ enunciativa. RILCE 32(1). 106–133.10.15581/008.32.2970Search in Google Scholar

García-Page, Mario. 2008. Introducción a la fraseología española: estudio de las locuciones. Barcelona: Anthropos.Search in Google Scholar

Gozalo Gómez, Paula. 2013.The discourse marker bueno. Analysis and didactic proposal. Signos ELE: Revista de Español como Lengua Extranjera.Search in Google Scholar

http://p3.usal.edu.ar/index.php/ele/article/view/1165 (accessed 3 Decembrer 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Guevara, Gloriella. 2015. Funciones del marcador discursivo pues: en un corpus oral. Dialógica: revista multidisciplinaria 12(1). 294–323.Search in Google Scholar

Hidalgo Navarro, Antonio. 2016. Prosodia y (des)cortesía en los marcadores metadiscursivos de control de contacto: aspectos sociopragmáticos en el uso de bueno, hombre, ¿eh? y ¿sabes? In Antonio Miguel Bañón Hernández, María del Mar Espejo Muriel, Bárbara Herrero Muñoz-Cobo & Juan Luis López Cruces (coords.), Oralidad y análisis del discurso: homenaje a Luis Cortés Rodríguez. 309–336. Almería: Editorial Universidad de Almería.Search in Google Scholar

Holgado Lage, Anais. 2017. Diccionario de marcadores discursivos para estudiantes de español como segunda lengua. New York: Peter Lang.10.3726/b11456Search in Google Scholar

Holgado Lage, Anais & Edgardo Gustavo Rojas. 2016. ¡Ni hablar! Estudio contrastivo de dos funciones comunicativas opuestas en las variedades peninsular y rioplatense del español actual. Oralia 19. 111–129.10.25115/oralia.v19i1.6946Search in Google Scholar

Holgado Lage, Anais & Patricia Serrano Reyes. 2020. El uso de los marcadores de aceptación en Colombia, España y México: Un acercamiento descriptivo. In Antonio Messias Nogueira, Catalina Fuentes Rodríguez & Manuel Martí Sánchez (eds.), Aportaciones desde el español y el portugués a los marcadores discursivos. 345–362. Sevilla: Ediciones Universidad de Sevilla.Search in Google Scholar

Landone, Elena. 2009. Los marcadores del discurso y la cortesía verbal en español. Bern: Peter Lang.10.3726/978-3-0351-0103-4Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 2001. Principles of linguistic change, Volume 2: Social Factors. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Martí, Manuel. 1998. Recorrido por ni. Lingüística Española Actual XXI(1). 79–108.Search in Google Scholar

Martín Zorraquino, María Antonia. 2001. Nuevos enfoques de la gramática: Los marcadores del discurso. A propósito de los marcadores que indican evidencias: La expresión del “acuerdo” y la toma de postura por parte del hablante. In Ramón González Cabanach, Ramón, Francisco Crosas López & Javier de Navascués y Martín (coords.), VIII Simposio General de la Asociación de Profesores de Español. 1–14. Pamplona: Newbook Ediciones.Search in Google Scholar

Martín Zorraquino, María Antonia. 2015. De nuevo sobre los signos adverbiales de modalidad epistémica que refuerzan la aserción en español actual: propiedades sintácticas y semánticas y comportamiento discursivos. In Gunnel Engwall & Lars Fant (eds.), Festival Romanistica: Contribuciones lingüísticas – Contributions linguistiques – Contributi linguistici – Contribuições lingüísticas. 37–63. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.10.16993/bac.cSearch in Google Scholar

Martín Zorraquino, María Antonia & José Portolés. 1999. Los marcadores del discurso. In Ignacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (dirs.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española vol. 3. 4051–4213. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez Hernández, Diana. 2016. Análisis pragmaprosódico del marcador discursivo bueno. Verba: Anuario galego de filoloxia 43. 77–106.10.15304/verba.43.1888Search in Google Scholar

Moliner, María. 1966. Diccionario de Uso del Español. Madrid: Gredos.Search in Google Scholar

Muñoz Medrano, María Cándida. 2017. Análisis descriptivo de los valores del marcador discursivo pues en el registro coloquial: aportación de los repertorios lexicográficos. Analecta Malacitana 42. 157–178.Search in Google Scholar

Olza, Inés. 2011. Qué fraseología ni qué narices. Fraseologismos somáticos del español y expresión del rechazo metapragmático, Spanish somatic idioms and metapragmatic negation. In Antonio Pamies Bertrán, Juan de Dios Luque Durán & Patricia Fernández Martín (eds.), Paremiología y herencia cultural. 181–191. Granada: Educatori.Search in Google Scholar

Penadés Martínez, Inmaculada. 2012. La fraseología y su objeto de estudio. Lingüística en la Red X. http://www.linred.es/monograficos_pdf/LR_monografico10-articulo2.pdf (accessed 3 December 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Pérez Salazar, Carmela. 2017. Ni por lumbre: modelo fraseológico para la negación y el rechazo en la historia del español. In Carmen Mellado Blanco, Katrin Berty & Inés Olza (eds.), Discurso repetido y fraseología textual (español y español-alemán). 269–298. Madrid/Frankfurt: Iberoamericana-Vervuert.10.31819/9783954876037-015Search in Google Scholar

Pérez-Salazar, Carmela. 2009. Ni hablar, ni pensar, ni soñar. Análisis histórico de su transformación en unidades fraseológicas. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica LVII(1). 37–64.10.24201/nrfh.v57i1.2398Search in Google Scholar

Perona, José. 2000. La cohesión textual y los enlaces extraoracionales. In Manuel Alvar (dir.), Introducción a la lingüística española. 445–462. Barcelona, Ariel.Search in Google Scholar

Porroche Ballesteros, Margarita. 2011. El acuerdo y el desacuerdo. Los marcadores discursivos bueno, bien, vale y de acuerdo. Español actual: Revista de español vivo 96. 159–182.Search in Google Scholar

Real Academia Española. 2014. Diccionario de la lengua española. https://dle.rae.es (accessed 15 April 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Ruiz Gurillo, Leonor. 2001. Las locuciones en español actual. Madrid: Arco/Libros.Search in Google Scholar

Ruiz Gurillo, Leonor. 2010. Interrelaciones entre gramaticalización y fraseología en español. Revista de filología española XC(1.0). 173–194.10.3989/rfe.2010.v90.i1.201Search in Google Scholar

Sánchez Carranza, Ariel. 2013. An analysis of pues as a sequential marker in Mexican Spanish talk-in-interactions. Spanish in Context 10(2). 284–309.10.1075/sic.10.2.05vazSearch in Google Scholar

Santos Río, Luis. 2003. Diccionario de Partículas. Salamanca: Luso Española de Ediciones.Search in Google Scholar

Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511611841Search in Google Scholar

Seco, Manuel, Olimpia Andrés & Gabino Ramos. 2004. Diccionario fraseológico documentado del español actual: Locuciones y modismos españoles. Madrid: Santillana.Search in Google Scholar

Simpson-Vlach, Rita & Nick C. Ellis. 2010. An academic formulas list: New methods in phraseology research. Applied linguistics 31(4). 487–512.10.1093/applin/amp058Search in Google Scholar

Yus, Francisco. 2011. Cyberpragmatics. Internet-mediated. Communication in Context. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.213Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews