Abstract

Most researchers associate the beginnings of phraseological studies with Charles Bally (1909) and Soviet studies, especially with V. V. Vinogradov (e.g. 1944; 2001 [1947]), and with English and German studies (e.g. Burger 1973; Rothkegel 1973). However, this article will show that phraseology actually has a centuries-long tradition, at least as far as some languages, including Italian, are concerned.[2] First, I will briefly show what “phraseology” means according to a modern conception, and what it meant originally. The development of the term is traced using some old rediscovered “phraseologiae”, which also have relevance to phraseography and phraseodidactics.

1 “Phraseology” according to a modern conception

In a narrow definition, “phraseology” nowadays usually refers to idiomatic expressions. In a broader sense it refers to phrasemes, which include word combinations such as collocations and idioms. While for some languages such as German and Spanish the terminology is more or less clear, for others such as Italian it still needs to be systematized (cf. Schafroth, Imperiale and Autelli in progress). As far as the German terminology is concerned, Burger’s classification (2015) is one of the best-known. He mainly distinguishes between referential, structural and communicative phrasemes. Referential phrasemes are non- or semi-idiomatic ones, such as collocations (e.g. the alarm clock goes off, to go on foot, happily married, bad tooth), nominal phrasemes that in some languages can correspond to nominal compounds (e.g. bucket hat or contact lenses), phrasal verbs (e.g. call back and fall down), adverbial expressions (e.g. in great hurry), comparative phrasemes (e.g. as busy as a bee) and binomial pairs (e.g. black and white and fish and chips). According to Burger, referential phrasemes further include idiomatic referential phrasemes, such as idiomatic expressions (e.g. add fuel to the fire), idiomatic nominal phrasemes (e.g. honey moon), idiomatic phrasal verbs (e.g. do up or put across), adverbial expressions with idiomatic meaning (e.g. at the end of the day) and cinegrams (e.g. open your eyes). All of the above are distinguished from communicative phrasemes (context-bound or not), which, among others, include routine formulae (e.g. Kind regards; How are you? or How do you do?), famous quotations / authors’ phrasemes (e.g. The die is cast or To be, or not to be? That is the question), pragmatic phrasemes and constructional idioms (e.g. What the hell/fuck are you doing?), but also clichés or catchphrases (e.g. This is the last straw!) and idiomatic phrases (e.g. That’s where the shoe pinches!), as well as structural phrasemes (prepositional, such as with regards to or on behalf of or conjunctional such as as well as, the main characteristics of which are polylexicality, fixedness and idiomaticity), and lastly proverbs (e.g. The early bird gets the worm and A watched pot never boils).

As Burger (2015) sums it up, phraseology has developed over the years. For one thing, nowadays studies are also based on corpora. Furthermore, the importance of collocations in phraseological studies has grown continuously; and there are more and more studies in contrastive linguistics, as well as on less examined figures such as constructional idioms (cf. also Schafroth 2020 for an overview on the terminology), that can be viewed as falling within the realm of phraseology.

Studies on “phraseology” are also associated with many other fields nowadays, including psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, and historical, cultural, pedagogical and translation studies. The term is also used in fields as diverse as law, aeronautics, communication and radiotelephony as well as music. The latter uses it to refer to a certain melodic unit (cf. Autelli in progress). Finally, from a linguistic point of view, phraseology plays an important role in dictionaries and language teaching (see Sections 2.1 and 2.2 on the origins of phraseography and phraseodidactics) and, as we will see, in the past could refer to a style, to quotations or to a certain choice of words or language.

2 The origins of the term “phraseology” (“phraseologia”, “phrasiologia”, “phraséologie”, “Phraseologie”, “fras(e/i)ologia”)

A search of online library catalogues and other online sources[3], as well as the Biblioteca Berio of Genoa and the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale of Florence for “phraseology” and correlated terms, lead to the discovery that the term “phraseology” was already in use in many centuries-old works and titles. Many of the “phraseologiae” I found were written in Italian, but many of them were also in other languages, mostly in Latin, (Italian and) French, but also in German and English.[4]

The term “phraseology” most likely dates back to the Greek phrásis (φράσις) (= ‘the way of speaking/communicating’), or possibly to the late Latin form phrasis (meaning ‘diction’, cf. Harper 2001–2020), but it may also be connected to phrázein (φράζειν), (meaning ‘communicating, showing’, cf. “Phraseologie” in Pfeifer et al. 1993). What is certain is that it developed and partly changed meaning over the centuries. This is why it is important to analyze the examples and terminology found in some historical works including so-called “phraseologiae” or “fraseologie” [phraseological works]. In what follows, I will analyse correlated terms deriving from Greek and Latin (the languages of the classics), from the Germanic languages English and German and from the Romance languages Italian and French, that were often also taught at school in the past (especially in commercial schools).[5]

One can find the Latin term “phraseologia” in many works from the 16th century (e.g. Neander 1558; Guildner 1598), and then more and more in the following centuries (cf. Autelli in progress for more information). Vladeraccus also published so-called “formulae” [formulas] (cf. Vladeraccus and Plantin 1586), referring to phrasemes used by Cicero in his letters. Several “phraseologiae” were published in order to help with oral communication (e.g. Schore 1609; Sorger 1625) and to help with writing (e.g. Fündtler 1622 for the German language). Many contained “phrases” (corresponding to phrasemes of several kinds) taken from religious texts (e.g. Schultheis 1593; Alsted 1626; Clarke 1655; Spadafora 1688) or quotations from important authors. The quotations could represent phrasemes as well as free combinations or sentences: the writers mainly paid attention to the style of the selected author(s). In addition to the term “phraseologia”, the term “phrasiologia” can be found starting from the 17th century (cf. Kohlhans 2020 [1676]).

The term “phrasis” was already present in a 1496 work by Ulsenius, who emphasized medical language. In the 16th century the term mostly meant “the way of speaking or expressing oneself” (“das Sprechen, Ausdruck[sweise]” in Pfeifer et al. 1993). Artopoeus (1534) and Erasmus of Rotterdam (1500–1536 and 1517) listed sayings and quotations, including idioms (not labelled as such, cf. Burger 2018, 23) and making reference to so-called “paraphrasis” (cf. Erasmus 1529). Most of the works containing “phrasis” referred to religious texts (e.g. Gregorius et al. (1520); Brunfels (1528); Westheimer and Setzer (1528); van Campen and Chevallon (1532)). Delle phrasi toscane (Montemerlo 1566) (mentioned also in Fanfani in print) contains a huge collection of religious phrasemes according to the modern conception, including sayings, idioms, collocations and communicative phrasemes albeit not labelled as such. Further “phrasi” were published by Cockburn (2020 [1558]) and by Maier (1618).

There is also the term “phrase”, which can already be found in works from many centuries ago. In the Middle English Dictionary, it meant “combined words or phrases”, which Pecock (1449) named “tọ̄̆geder-wordes” or “togiderewordis”, to be found also as “to gidere wordis”. Alvarez del Marmol (1611) lists (for example on p. 80) many different kinds of phrases, including a lot of collocations and idiomatic expressions (the meanings of which are not explained), such as “La esposa preñada salta de plazer con la cria en el vientre” [lit. ‘The pregnant wife jumps for pleasure with the baby in her belly’] and “En una caña larga anda a caballo” [lit. ‘On a long cane he rides’], but also maxims such as “Son furiosos los que matan a si mismo” [‘Those who kill themselves are furious’]. Smith (1674) listed some “Phrases” and in particular some “pure Gallicisms” (p. 70) that nowadays correspond to communicative phrasemes, with the English equivalents next to them, such as “Comment vous va? How fares it with you? How do things fadge?”. As far as Italian is concerned, the term “fraseologia” is connected to that of “frase” a term that is also found in the different editions of the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca (1612), which also includes the terms “fras[i] latin[e]” [Latin phrases] (1691: 20), “locuzioni” [locutions] (1612, preface and 1691: 20), and “maniere latine” [Latin phraseologias]). For proverbs one can find the labels “proverbi” [proverbs] (1612: preface and 1691: 26), “detti proverbiali” (1691: preface) and “modi proverbiali” [proverbial sayings] (1691: 26).[6] Next to the “modi di dire” [sayings] (1612: preface), one can also find the so-called “modi di favellare” [ways of speaking] (1612, preface). In another work dating back to the 16th century, the Dictionnaire Francoislatin (Estienne 1549), one can also find “mots et manieres” [words and manners] in the preface. According to Pfeifer et al. (1993), in the 18th century, the term “Phrase” (from the French “phrase”) meant “empty” phrase (defined by Pfeifer et al. 1993 as “Phrasen dreschen ‘inhaltloses, leeres Geschwätz vorbringen und wiederholen’” [Phrase-mongering ‘to present and repeat empty chatter with no content’]. As Burger (2012: 13, 17) also points out, quotations were once very important in conversation too. This echoes Linke (1996) in some studies of texts from the 19th century and several other writings such as those of G. Buchmann (cf. Burger 2012: 13).

Several important studies on historical phrasemes have been conducted (cf. for ex. Filatkina et al. 2012), however, the so-called “phraseologiae” found in the past have not yet been much analyzed (for further details on the Italian “fraseologie” cf. also Autelli in progress). The 18th century saw the appearance of the so-called “tesori” (e.g. Buoni 1606) and “frasari” (a kind of “Phrase Book”, referenced by Robertson in 1686). They included those of Malatesta Garuffi (1720), followed by those of AA.VV. (1810), De Mordax (1860), A. F. (1890) and Capra (1874). Such works contained many kinds of phrasemes. Even if not labelled as such, phrasemes were also to be found earlier, for example in the Flos Italicae linguae (Monosini 1604), which documented a great number of phrasemes, including proverbs and the explanation of terms used by certain authors.

The English term “phraseology” once referred to a variety of phrases contained in the Authorized Version of the Bible which then became part of the common English language (cf. also Reynell 1564; Rogers 1582; Burton 1805). One of the first dictionaries containing the word “phraseology” in the title is an English-Welsh dictionary from the 18th century (cf. Richards 1798). Later on, the term was also used in the context of law, e.g. in the House of Representatives. In law, the term probably referred at first to the choice of words, whereas later on and nowadays it still rather refers to the manner, style or diction of legal language, also called “legalese” (cf. also Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary 2010).

The French term “phraseologie” (“phraséologie”) can be found in the title of a multilingual work from the 17th century by Pielat (1673), in a French work by Du Cloux (1678), in the French-German “dictionnaire[s] phraseologique[s]” by Kramer (e.g. 1712); and later in many bilingual works, for example the French-German work by Pignata (1776) and a French-Italian work by Bochet (1846), although works with phraseological content existed much earlier on in French too (cf. for example Les épithètes by Maurice de la Porte of the 16th–17th century, cf. De Giovanni 2014).

Though the German term “Phraseologie” has not always been used, many old phraseological works made reference to it (e.g. Schoensleder 1619). Hederichs (1713: 264) wrote a “Phrasiologia latina” in German, which he defined as “eine Grammaticalische Wissenschaft von den Lateinischen Phrasibus und Redensarten” (“a grammatical science of Latin phrases and sayings”). In it, he explains that “Phrasiologia” was already well known as a scientific field, but that the term was also often applied to collections of phrases. In order to explain the scientific meaning of “Phrasiologia”, he distinguishes between different kinds of phrases. He highlights that the term also covers the meanings of phrases, with their use, their syntax and what he calls “Taxi” (‘order’) (Hederichs 1712: 265).

In the next century, one can also find specific phraseological terminology in B. Schmitz’ publication (1872). He was a teacher and invested a lot of time in creating this work, in which he also highlights the importance of using the mother tongue to learn the phraseology of other languages. In his introduction, Schmitz makes use of terms such as: “stehende Redensart (locution faite, phrase faite)[, e.g.] Anstand nehmen (hésiter)[,] formelhafte Phrase (formule)[),], Phrasen im weiteren Sinne [, e.g.] Fische fangen (prendre du poisson, pêcher)[,] ein Idiom (ein idiom, gesprochen idiôme)[, e.g.] Idiotismen”. He also distinguishes between what he calls grammatical and rhetorical sayings (“Redensarten”), the latter being defined as “bildliche […] oder metaphorische […] Redensarten (phrases figurées)”. In his work, Schmitz also writes about “sprichwörtliche[] Redensart (locution proverbiale)” (p. 2) and divides the phrasemes into morpho-syntactic order. He also adds a rhetorical part focusing on Latin phrases and on phrases taken from the Bible (cf. Autelli in progress).

2.1 Examples of a long-ignored phraseographical tradition

It seems nearly impossible that such a long phraseographical tradition has been so little discussed in the secondary literature: there remains a treasure to be discovered (cf. Autelli in progress for more information). As mentioned in the previous sections, many “phraseologiae” reported “phrases” (of different kinds, consisting of whole sentences or chunks, free or phraseological) written by famous authors or of a religious kind, found in some collections or proper dictionaries. In this chapter, five Italian and bilingual phraseological works from the 17th–20th centuries will be investigated.[7]

Very often such works were written by teachers like Matthias Kramer, who taught Occidental languages and has become an important reference point for language teaching (cf. Häberlein 2020). His dictionaries were addressed to common readers as well as teachers and, as a member of the Royal Academic Society, Kramer dedicated them to the King of Prussia Friedrich I. Kramer’s Italian-German and German-Italian dictionaries (1676a, 1676b, 1678, 1700, and 1724) were some of the first bilingual phraseological dictionaries to appear in the 17th century. His dictionaries, “amplificat[i] di ricchissima fraseologia” [enriched by a vast phraseology] and “da molti desiderat[i]” [desired by many], were mostly formatted in two columns and, independently of the direction of translation, gave great importance to so-called “Phrases”, as one can see in the example in Fig. 1 below, showing the two entries for “Ingegno” [intellect/wit/talent/tool].

![Fig. 1: “Ingegno” [intellect/wit/talent/tool] in Kramer (1676b: 931)](/document/doi/10.1515/phras-2021-0003/asset/graphic/b_phras-2021-0003_fig_001.jpg)

“Ingegno” [intellect/wit/talent/tool] in Kramer (1676b: 931)

Kramer also cites several authors and makes reference to the lexical work of La Crusca. Moreover, as Fig. 3 shows, he distinguishes between lemmas with different meanings, giving the translation of the single lemma first; and then he lists different kinds of what would nowadays be referred to as phrasemes. Amongst them are collocations according to a broad conception. These include morpho-syntactic structures such as N+Adj. (e.g. “ingegno buono, acuto, sottile” [sharp intellect, quick wit] or N+PrepS (e.g. “ingegno da governo” [government tactics]), but also whole sentences (e.g. “vi sono certi esempi bizzarri e bestiali” [there are certain bizarre and “bestial” examples]) and binomial pairs (e.g. “con argani e simili ingegni” [with similar means and tools]).

In the preface to his first edition (1676a), Kramer refers to phraseology (“Phraseologia” and “fraseologia”) as the “uso genuino” [genuine use] of vocabulary and locutions of the two languages, explaining that along with simple words he had included derivates and compounds (“Compositis gedoppelte[] Wörter[]”), but also – under the numerous “Phrases” – idiotisms and idiomatic expressions (“Redarten”) marked with an asterix, “Proverbualische Redarten” [proverbial sayings], “Proverbiorum” [proverbs] and “Sprüchwörter” [sayings]. Several kinds of “phrases” are contained that nowadays would correspond to referential, structural and communicative phrasemes. Finally, Kramer also collected swearwords, which he called “Parole Sporch[he]”.

A large number of religious “phraseologiae” were also published starting from the 16th century, most of them written by bishops or priests like G. Gallicciolli, whose volume was published in the 18th century, during the Industrial Revolution. The main aim of these works was to bring the Bible closer to young readers. Fig. 2 shows an example:

![Fig. 2: “Spina” [thorn] in Gallicciolli (1773: 556)](/document/doi/10.1515/phras-2021-0003/asset/graphic/b_phras-2021-0003_fig_002.jpg)

“Spina” [thorn] in Gallicciolli (1773: 556)

As the reader can see, the lemma “Spina” (Gallicciolli 1773) is followed by the Italian equivalents and by Latin quotations from the Bible with translations or explanations in Italian.

As far as the Italian language is concerned, there seems to have been a boom in the 19th century of so-called “fraseologie” intended as dictionaries of different kinds, perhaps partly as a result of the Unification of Italy in 1861 and the wish to spread a common language:[8] Examples include those of Bartoli (1826), Lissoni (21836), Percolla (1870 and 21889) and Ballesio (1898–1902 and 21898).[9] Ballesio, who mostly focuses on descriptions of lemmas and on style, reports some occasional phrasemes in small capital letters, illustrating them with quotations from important authors, thus construing “phraseology” as a means to achieve elegancy and accuracy, by making reference to the past. Percolla (21889) (see Fig. 3), on the other hand, reports useful “phrases” in Sicilian, including some texts that contain them:

![Fig. 3: “Abbracciare” [to hug] in Percolla (21889, 14–15)](/document/doi/10.1515/phras-2021-0003/asset/graphic/b_phras-2021-0003_fig_003.jpg)

“Abbracciare” [to hug] in Percolla (21889, 14–15)

Next to each lemma Percolla collects what we would nowadays call “phrasemes” (of several kinds). He also uses “modern” expressions, and includes what we nowadays refer to as “collocations”, such as “Abbracciare un partito” [embrace a party], idiomatic expressions such as “Abbracciare Giuda” [lit. embrace Judah, meaning ‘become a traitor’], proverbs such as “Nel mondo son molti che si abbracciano in palese, e poi si tradiscono in segreto” [There are many in the world who embrace in the open and then betray each other in secret], and communicative phrasemes such as “Dari un abbrazzu a l’amicu” [give your friend a hug]. All of the examples are in italics and the meanings of the word combinations are added, creating a kind of “phraseological dictionary” like the ones we know nowadays.

It is also worth mentioning that several regional “phraseologiae” were published in the 19th century, some even earlier, like the Tuscan “phrasi” published by Montemerlo in 1566. For diatopic varieties spoken in Italy one can find, for example, Collina’s (1817) unnamed work on Tuscan phraseology[10]; Sicilian-Tuscan phraseologies by Caglia Ferro Ruibal (1840) and by Castagnola (1863, 1865); the Piccola fraseologia italiana (Percolla 21889) also containing some Sicilian proverbs; and Mutinelli’s (1851 and 1852) works on Venetian phraseology.

As already briefly explained, so-called “phraseologiae” or “fraseologie” are interesting not only because of their structure, but also for their denomination of phrasemes. One of the most representative works for phraseological terminology is the Fraseologia francese[11]- italiana by Elvira Baroschi Soresini (1899),[12] who presents the phrasemes in different categories, as follows:

“Phraséologie familière” [familiar phraseology] (with the subtitle “et tours élégants et figurés de la conversation”), further subdivided into “Désignations – appellations, etc.” [designations – appeals] and “Autres formules, locutions, designations, etc. consacrées par l’usage” [other formulas, locutions, designations etc. listed according to their usage], in alphabetical order;

“Phraséologie grammaticale” [grammatical phraseology], with an extra part on “Phraséologie sur les Synonymes” [phraseology of synonyms];

“Nomenclature et phraséologie commerciale” [nomenclature and commercial phraseology]; and

“Recueil de proverbs” [collection of proverbs], also containing a section dedicated exclusively to so-called “Similitudes et comparisons” [similes and comparisons].

Fig. 4 below shows examples taken from each section.

Different kinds of phraseology in Baroschi Soresini (1899)

The classification adopted by Baroschi Soresini (1899) shares some important features with many modern works. There are, however, also some particularities, for example in the first section it contains “familiar” phrasemes: useful expressions for conversation, both elegant and figurative. This section mostly contains what we would nowadays refer to as collocations and idioms, such as “Nager à la brasse” [swim breaststroke] and “N’avoir ni croix ne pile” [Get neither heads nor tails] (p. 52). However, it also contains compounds such as “mât de cocagne” [cocagne mast (slippery pole)] (p. 83) and occasionally lists sentences that represent other kinds of phrasemes, such as “Oeil pour oeil, dent per dent” [an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth] or “On t’a tendu un piège – tu y as donnée” [You’ve been set a trap and you have fallen into it] (p. 55).

The author also includes a second section on contrastive grammar and usage, where she provides specific examples to underline the differences between French and Italian (for example in the use of tenses and articles and auxiliaries). What we understand as collocations and communicative phrasemes are often contained in these sample sentences.

There is also a separate section for specialized terminology containing mostly single words and compounds in the nomenclature section, such as “Banquier” [banker] and “Bailleur de fonds” [provider of funds] (p. 220), but also collocations and communicative phrasemes such as “Suivant note d’autre part” [in accordance with the other party’s report] (p. 232) in the part concerning commercial phraseology.

The fourth section shows that proverbs were included as part of phraseology. It is interesting that the part on “similes and comparisons” is listed as a subsection of this one, thus in some way belonging to it, perhaps due to the fact that both classes contain plenty of metaphors? The section “similitudes et comparisons” contains exclusively what are now referred to as comparative phrasemes, both idiomatic and non-idiomatic.

Baroschi Soresini’s work, like many other “phraseologiae”, was created to help avoid common language mistakes. The author also published another book (1912) to help use phraseology in conversation. For further details on phraseodidactics, see the next Section.

In the 20th century, a work could still look like the example in Fig. 5, with parts of quotations included to highlight the language of the classics and serve as a stylistic model. Fig. 5 shows a 20th century work in which one can see that the Latin “phrases” included (here corresponding to collocations), are listed in semantic order first and then in alphabetical order, giving the Italian equivalents on the right and the source of the Latin authors below, to the left of centre.

Phraseology taken from famous writers as found in Pirrone (1907: 39), who puts the focus on what we would call collocations

2.2 Examples for some useful phraseodidactics exercises

It is remarkable that most of the so-called “phraseologiae” were explicitly intended for teaching purposes. In this chapter I analyse a few “phraseologiae” published in the 19th and 20th centuries[13], and show bilingual (German-Latin and French-Italian) and monolingual didactic tasks (that focus on Italian and on Dante’s speech), then a multilingual (English, Italian, French, German, Spanish) “manual”.

Most of the works I found were written especially for scholars (e.g. Meissner 1880), and often ordered the “phrases” according to relevant themes. They provided models for the expression of ideas. Some authors wrote “phraseologiae” for primary school children (e.g. Fornier 1868?), or for high school pupils (e.g. Widmer Gotelli 1895 and Probst 1868). Some wrote collections especially for trade schools, such as Barera (1923). Petrini (1888) presented, for example, French texts with footnotes in Italian and also translated polylexical units.

Some “fraseologie” were created to provide translation exercises. For French-Italian see e.g. Zoni (1859), for German-Italian Gatti (1887) and Fornasari-Verce (1833). Fig. 6 shows a translation exercise from German into Latin for high schools, from a volume in which Geist (1835) provided texts followed by comments in footnotes, with “unterlegter Phraseologie, beständiger Verweisung auf [verschiedenen Grammatiken,] grammatischen, stilistischen, synonymischen und antibarbarischen Bemerkungen” [with integrated phraseology, constant reference to [various grammars,] grammar, style, synonymy and anti-barbaric remarks].

Example of a translation exercise (Geist 1835: 110)

“Phraseologiae” were sometimes also written for workers, like that of Pesenti Del Thei (1941), who (as explained in the preface) collected technical phrasemes (that we would nowadays classify as collocations or compounds) for the “lavoratori Agricoli e Meccanici [per] far[s]i intendere e […] comprendere [dai] camerati del Reich amico” [Agricultural and Mechanical Workers [to be] understood and [by] their comrades of the Reich]. The work was later banned from reproduction for political reasons.

Many “phraseologiae” were a kind of anthology or dictionary created to show and explain elegant phrases used by famous authors like Cicero, Virgilio, Dante and Tasso. The phrases corresponded to entire sentences, as in Ferrazzi’s (1865) Fraseologia della Divina Commedia, which lists items according to the meaning of some collocates. Phrases are reported under alphabetically arranged general meanings associated to the collocates, as shown in Fig. 7.

![Fig. 7: Phrases listed under the meaning “Insufficiente” [not enough] in Ferrazzi (1865: 426)](/document/doi/10.1515/phras-2021-0003/asset/graphic/b_phras-2021-0003_fig_007.jpg)

Phrases listed under the meaning “Insufficiente” [not enough] in Ferrazzi (1865: 426)

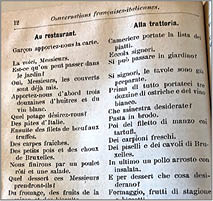

As far as conversation exercises are concerned there were several proposals. Baroschi Soresini (1912) collected some useful French dialogues for standard situations, displaying the Italian translation next to them, as can be seen in Fig. 8.

“Conversations françaises-italiennes” in Baroschi Soresini (1912: 12)

Among the “phraseologiae” found were also some “manuali di fraseologia” [phrase manuals], useful e.g. for travellers (e.g. Milesi and Gotti 1980). These contained lists of useful phrases (nowadays called communicative phrasemes) for different topics, followed by a nomenclature and translated into different languages. Fig. 9 shows an example from Valentini (1993).

![Fig. 9: “In albergo” [at the hotel] in Valentini (1993: 38)](/document/doi/10.1515/phras-2021-0003/asset/graphic/b_phras-2021-0003_fig_009.jpg)

“In albergo” [at the hotel] in Valentini (1993: 38)

As can be seen from the examples given so far, a lot of material for what we would nowadays call “phraseodidactic exercises” has been found. However, this is just a brief overview of some of the discovered materials (which will be discussed further in Autelli in progress). For example, a lot of commercial language resources have been found in works containing the terms “phraseologia” or “fraseologia” [phraseology] in the title. Most of the exercises, usually intended for school pupils, could not nowadays be used in class because of the antiquated language and because most of the publications are no longer on the market. Nonetheless, they could serve as models for modern phraseodidactic materials (cf. also Autelli 2021).

3 Conclusions

The poor, though very famous Charles Bally can probably no longer be referred to as the very first phraseologist for his Traité de stylistique française, as there was already a long and varied tradition before him, albeit the works were mostly of a practical nature as opposed to theoretical essays. Somehow, this fact was ignored for centuries, possibly because many works were written in Italian, and although the modern field of phraseology is attracting more and more attention in Italy, there has not so far been as much awareness of this field of study as there is for other languages. However, other old so-called “phraseologies” published in other languages have barely been analyzed either.

The approaches used in the “phraseologiae” require further analysis (cf. also Autelli in progress), however, it is already clear that they contained several kinds of “phrases”. The term “phraseology” can already be found referring to medical language in the work De pharmacandi comprobata ratione (Ulsenius 1496). Later works, produced towards the 16th century, primarily focused on quotations of famous authors (e.g. Isocrates 1555, cf. also Neander 1558) or of a religious type, mostly taken from the Bible (e.g. Gallicciolli 1773). Next to the term “phraseologia”, the term “phrasiologia” was also found in the 17th century. Regional “phrases” were also presented in works such as Delle phrasi toscane by Montemerlo (1566) that contain several kinds of phrasemes. At that time, it was viewed as extremely important to write and communicate in a proper manner. This is why famous authors were important role models for what was considered to be elegant, correct style. Most of the works were created to help avoid making horrible mistakes, sometimes called “barbarisms”, also in conversation, as many works of the 18th century show. At that time, the first so-called “tesori” [from “thesaurus”] or “frasari” (the latter probably from “Phrase Books”, a term already found in Robertson 1686) appeared, too (cf. Malatesta Garuffi 1720). The “phraseologiae” found are of different kinds: some were meant to assist travellers (for example with “manuali”, e.g. Milesi and Gotti 1980; Valentini 1993) and thus mostly contained phrases that are well-known as communicative phrasemes nowadays; others were proper dictionaries or collections of “phrases”, often divided into different topics and listed in alphabetical order. Kramer’s dictionaries (since 1676) were the first “proper” phraseological Italian-German and German-Italian dictionaries. They serve as a guide on how to create such a work nowadays. In these works, Kramer cited the Accademia della Crusca and several authors: a lot of the earlier “phraseologiae” primarily focused on quotations by famous authors. I also found works destined to help with translation. These likewise contained “phraseology” in the title, but mostly showed texts accompanied by useful vocabulary at the bottom. Most interestingly, I found a significant amount of phraseological terminology from before Charles Bally’s time, which requires further investigation[14]: for example, in Baroschi Soresini’s Fraseologia francese-italiana (1899), she lists several kinds of “phraséologie”, such as “familiar”, “grammatical” “commercial”, and, for example, calls “similes and comparisons” what we nowadays refer to as communicative phrasemes.

It is worth reiterating that the ancient “phraseologiae” found were mainly intended for didactic purposes, which is why they might give us helpful hints about how to teach phraseology nowadays.

This publication was made possible by the research undertaken in two research projects (GEPHRAS and GEPHRAS2, led by Erica Autelli at the University of Innsbruck) financed by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): [P 31321 and P 33303-G]. Many thanks to Christina Scharf and Claire Archibald for proofreading this article.

References

Secondary literature

Autelli, Erica. 2021. Spunti per la fraseodidattica di italiano L2/LS in base al ritrovamento di “fraseologie” storiche italiane. Italiano LinguaDue 13(1), 319–347.10.54103/2037-3597/17126Suche in Google Scholar

Autelli, Erica. In progress. Fraseografia bilingue e delle varietà. Riflessioni diacroniche e sincroniche su esempio di alcune lingue e varietà romanze. Postdoctoral lecturer qualification thesis (Habilitation) at the University of Innsbruck.Suche in Google Scholar

Bally, Charles. 1909. Traité de stylistique française, Heidelberg: Winter.Suche in Google Scholar

Bally, Charles. 1951 [1909]. Traité de stylistique française, vol. II, 2nd edn. Heidelberg: Winter.Suche in Google Scholar

Burger, Harald (unter Mitarbeit von Jaksche, Harald). 1973. Idiomatik des Deutschen. Niemeyer: Tübingen.Suche in Google Scholar

Burger, Harald. 2012. Einleitung. In Natalia Filatkina, Ane Kleine-Engel Ane, Marcel Dräger, Marcel & Harald Burger (eds.), Aspekte der historischen Phraseologie und Phraseographie, 1–20. Heidelberg; Universitätsverlag Winter.Suche in Google Scholar

Burger, Harald. 2015. Phraseologie. Eine Einführung am Beispiel des Deutschen (Grundlagen der Germanistik 36), 5th edn. Berlin: Schmidt.Suche in Google Scholar

Burger, Harald. 2018. Wie weit, wie eng soll der Objektbereich der Phraseologie sein? Beobachtungen eines Zeitzeugen zu Konzeptionen im Wandel. In Filatkina, Natalia, & Stumpf Sören (eds.), Konventionalisierung und Variation. Phraseologische und konstriuktionsgrammatische Perspektiven (Sprache – System und Tätigkeit 71), 19–38. Berlin: Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

De Giovanni, Cosimo. 2014. La synonymie collocationnelle: entre corpus et dictionnaire bilingue. In Vida Jesenšek & Peter Grzybek (eds.), Phraseologie im Wörterbuch und Korpus (Zora 97), 61–74. Maribor: Univerzitet naknjižnica Maribor.Suche in Google Scholar

Fanfani, Massimo. In print. Modi di dire non toscani nel Vocabolario toscano di Pietro Fanfani. In Erica Autelli, Christine Konecny & Stefano Lusito (eds.), Dialektale und zweisprachige Phraseographie – Fraseografia dialettale e bilingue – Fraseografía dialectal y bilingüe (Reihe Sprachkontraste und Sprachbewusstsein). Tübingen: Edition Julius Groos im Stauffenburg-Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Fanfani, Massimo. In progress. Proverbi. In: Elmar Schafroth, Riccardo Imperiale & Erica Autelli (eds.), Manuale di fraseologia italiana. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.Suche in Google Scholar

Filatkina, Natalia, Ane Kleine-Engel, Marcel Dräger & Harald Burger (eds.). 2012. Aspekte der historischen Phraseologie und Phraseographie. Universitätsverlag Winter: Heidelberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Gatti, Giulia. 2016. Insegnare le lingue: storia, teoria e pratica attraverso uno studio di caso sull’inglese. Padua: Master thesis at the University of Padua.Suche in Google Scholar

Häberlein, Mark. 2020. Matthias-Kramer-Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der Geschichte des Fremdsprachenerwerbs und der Mehrsprachigkeit. https://www.uni-bamberg.de/hist-ng/matthias-kramer-gesellschaft/ (accessed 09 May 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Hederichs, M. Benjamins. 1713. Anleitung zu den fürnehmsten philologischen Wissenschaften / Nach der Grammatica, Rhetorica und Poetica, So fern solche insbesonderheit einem / der die Studia zu prosequiren gedendet, nützluch und nätig. Wittenberg: Zimmermann.Suche in Google Scholar

Linke, Angelika. 1996. Sprachkultur und Bürgertum. Zur Mentalitätsgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Stuttgart: Springer.10.1007/978-3-476-03641-4_3Suche in Google Scholar

Mclelland, Nicola. 2012. Français, anglais et allemand: trois langues rivales entre 1850 et 1945. French, English and German: three languages in competition between 1850 and 1945. OpenEdition Journals. 109–124.Suche in Google Scholar

Montoro del Arco, Esteban T. (2012). Fraseología y paremiología. In Alfonso Zamorano Aguilar (ed.), Reflexión lingüística y lengua en la España del XIX: marcos, panoramas y nuevas aportaciones. Lincom: Munich: (Lincom Studies in Romance Linguistics, 70), 173–196.Suche in Google Scholar

Olimpio de Oliveira Silva & María Eugenia (2020). La fraseología en la obra Fraseología o estilística castellana de Cejador y Frauca. In Elena Dal Maso (ed.): De aquí a Lima. Estudios fraseológicos del español de España e Hispanoamérica. Venecia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, 65–86.10.30687/978-88-6969-441-7/004Suche in Google Scholar

Pecock, Reginald. 1449. The repressor of over much blaming of the clergy, by Reginald Pecock. Babington Rolls Series (Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores) 19 (1860–1).Suche in Google Scholar

Rothkegel, Annely. 1973. Feste Syntagmen. Grundlagen, Strukturbeschreibung und automatische Analyse. Tübingen: Niemayer.10.1515/9783111593067Suche in Google Scholar

Schafroth, Elmar. 2020. Fraseologismi a schema fisso – basi teoriche e confronto linguistico. Romanica Olomucensia 32(1), 173–199.10.5507/ro.2020.009Suche in Google Scholar

Schafroth, Elmar, Riccardo Imperiale & Erica Autelli (eds.). In progress. Manuale di fraseologia italiana. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.Suche in Google Scholar

Vinogradov, Viktor Vladimirovic. 1944. Osnovnyje ponjatija russkoj frazeologii kak lingvističeskoj discipliny. Trudy jubilejnoj naučnoj sessii Leningradskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta [Grundkonzepte der russichen Phraseologie als linguistische Disziplin]. Leningrad: Sekcija filologičeskich nauk, 45–69.Suche in Google Scholar

Vinogradov, Viktor Vladimirovic. 2001 [1947]. Russkij jazyk. Grammatičeskoe učenie slova [Die Russische Sprache. Grammatische Wortlehre], 4th edn. Moskva: Russkij jazyk.Suche in Google Scholar

Dictionaries, grammars, corpora, translating programmes and so-called “frasari” and “phraseologiae”

AA.VV. 1810. Frasario italiano-francese ad uso degli Italiani e di tutti coloro che bramano di ben parlare, e di ben scrivere correttamente la lingua francese: coll’aggiunta di alcuni proverbj, e sentenze; il tutto estratto dai piu eccellenti autori, e dal rinomato dizionario di Alberti. Roma: Salomoni.Suche in Google Scholar

A. F. 1890. Frasario comparato italiano francese: raccolta di 1800 frasi, voci, maniere di dire famigliari e popolari italiane e francesi; coll’aggiunta di cento proverbi. Mantova: Stab. Tip. Lit. G. Mondovi.Suche in Google Scholar

Accademia della Crusca. 1612. Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca. Venezia: Giovanni Alberti.Suche in Google Scholar

Accademia della Crusca. 1691. Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, 3rd edn. Firenze: Accademia della Crusca. Firenze: Stamperia dell’Accademia della Crusca.Suche in Google Scholar

Alsted, Johann Heinrich. 1626. Paratitla theologica in quibus vera antiquitas, et phraseologia sacrarum literarum & patrum, sive priscorum ecclesiae doctorum. Opus methodo theologiae antehac in lucem editae praemittendum. Authore Johanne Henrico Alstedio. Francofurti: Sumptibus Conradi Eifridi.Suche in Google Scholar

Alvarez del Marmol, Juan. 1611. Janua Linguarum sive modus maxime accomodatus, quo patefit aditus ad omnes linguas intelligentas. Salamanca: de Cea Tesa.Suche in Google Scholar

Artopoeus, Petrus. 1534. Latinae phrasis elegantiae. Ex potissimis authoribus conscriptae. Vitebergae: Seitzen.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballesio, Giovanni Battista. 1898–1902. Fraseologia italiana. Firenze: R. Bemporad & figli.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballesio, Giovanni Battista. 21898. Fraseologia italiana. Firenze: R. Bemporad & figlio, tip. Landi.Suche in Google Scholar

Barera, Eugenio. 1923. The right phrase in the right place. Fraseologia inglese e correlativa antologia di letture moderne per gli alunni delle scuole medie e commerciali. Milano: Signorelli.Suche in Google Scholar

Baroschi Soresini, Elvira. 1899. Fraseologia francese-italiana. Milano: Hoepli.Suche in Google Scholar

Baroschi Soresini, Elvira. 1912. Conversazione francese-italiana, fraseologia famigliare, grammaticale, commerciale, ecc., 2nd edn. Milano: Hoepli, Tip. Sociale.Suche in Google Scholar

Barthram, Phil. 2008–2018. Old English to Modern English Translator. https://www.oldenglishtranslator.co.uk/index.htm (accessed 04 January 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Bartoli, Daniele. 1826. Fraseologia italiana o sia raccolta di venti mila frasi o modi di dire esposti in altrettante proposizioni colle relative spiegazioni per ordine alfabetico divisati coll’aggiunta di diversi capitoli intorno le parti del discorso ed alcune bellissime descrizioni del P. Daniele Bartoli. Milano: Tipografia Rusconi.Suche in Google Scholar

Bochet, Alexis. 1846. Recueil d’idiotismes, ou nouvelle phraseologie francaise et italienne. Venise : Pierre Naratovich.Suche in Google Scholar

Brunfels, Otto. 1528. Bibliorvm Phrasis Sanctae, Ex Piis Ivxta ac eruditis, tam priscoru[m] quam recentiorum Theologorum lucubrationibus innumeris adcurate, &ad uerbum quidem excerptae, Sectiones Duae. Haganoae: Secerius.Suche in Google Scholar

Buoni, Tomaso. 1606. Nuovo thesoro De’ Proverbi Italiani. Ciotti: Venetia.Suche in Google Scholar

Burton, William. 1805. Researches into the phraseology, manners, history and religion of the ancient Eastern nations, as illustrative of the Sacred Scriptures, and into the accuracy of the English translation of the Bible. Vol. 2. London: Burton.Suche in Google Scholar

Caglia Ferro Ruibal, Antonino. 1840. Nomenclatura familiare siculo-italica: seguita da una breve fraseologia. Compilata per Antonino Caglia da Messina. Messina: Stamp. Tommaso Capra all’insegna di Maurolico.Suche in Google Scholar

Capra, Pietro. 1874. Corso di temi italiano-latini per le classi di terza e quarta ginnasiale, coll’aggiunta di un frasario, ovvero raccolta di bei modi di dire della lingua italiana colla loro corrispondente locuzione latina. Roma et al.: Paravia e C.Suche in Google Scholar

Carini, Zeffirino. 1864. Saggio di frasi italiane. Firenze: Tipografia Calasanziana.Suche in Google Scholar

Castagnola, Michele. 1863. Fraseologia sicolo-toscana. Catania: Stab. tip. C. Galatola.Suche in Google Scholar

Castagnola, Michele. 1865. Replica alle osservazioni del signor Pietro Fanfani sulla Fraseologia sicolo-toscana. Catania: Stab. tip. C. Galatola.Suche in Google Scholar

Clarke, John. 1655. Phraseologia puerilis sive Elegantiae sermonis Latini parites atque Anglicani, capitatim concinnatae, atque in methodum alphabetariam distributae, in usunt scholastici. Or Selected Latine and English Phrases, very Usefulfor Young Latinists, to prevent Barbarism and bald Latine-Making: and to initiate them in Speaking, and Writing elegantly in both Languages, 3rd edn. London: Printed by R.D. for Francis Eglesfield, at the Marigold in St. Paul’s Church-yard.Suche in Google Scholar

Cockburn, Patrick. 2020 [1558]. De vulgari sacrae scripturae phrasi libri II Huic ed. secundae accessit appendix nova et tabula ab ysso authore descripta. Delhi: Pranava.Suche in Google Scholar

Collina, Giuseppe. 1817. Saggio di fraseologia Toscana. Bologna: Tip. Sassi.Suche in Google Scholar

De Mordax, Francesco. 1860. Primo dizionario e frasario di corrispondenza mercantile, italiano tedesco: tratto dai migliori e più recenti autori in questa sfera e corredato da due appendici. Triestem: Libreria G. Schubart.Suche in Google Scholar

Du Cloux, Louis-Charles. 1678. Vocabulaire François avec une phraseologie convenable à tous les mots, Composé en faveur & pour l’usage de la Ieunesse de Strasbourg par Louys Charle du Cloux, Maistre de la Langue Françoise. Strasbourg: Schmuck.Suche in Google Scholar

Erasmus, Desiderius. 1529. Paraphrasis luculenta, iuxta ac brevis in elegantiarii libros Lau. Vallae de lingua latina optime meriti. Coloniae: Gymnich.Suche in Google Scholar

Estienne, Robert. 1549. Dictionnaire Fracoislatin, autement dict Les mots Francois, avec les manieres duser diceulx, tournez en Latin. Paris: Estenne.Suche in Google Scholar

Ferrazzi, Giuseppe Jacopo. 1865. Fraseologia della Divina Commedia e delle liriche di Dante Allighieri: aggiuntavi quella del Petrarca, del Furioso e della Gerusalemme liberata con i confronti comparativi degli altri rimatori del secolo 13. e 14. Sante Pozzato: Bassano.Suche in Google Scholar

Fornasari-Verce, Andra Josef. 1833. Practische Anleitung zum Uebersetzen aus dem Deutschen in das Italienisch, mit beygefügter Phraseologie. Zu Erlangung der nöthigen Gewendtheit im Styl. Wien: Heubner.Suche in Google Scholar

Fornier, Jean August. 1868?. Phraseologie francaise familiere, diplomatique, tours elegants figures et proverbes de la langue francaise se deployant dans toutes ses phases comparatives avec la langue italienne : faisant suite et complement a l‘enseignement elementaire : a l’usage des italiens. Monza : Paleari – Clerici.Suche in Google Scholar

Franciosini, Lorenzo. 1620. Vocabolario italiano, e spagnolo non più dato in luce nel quale con la facilità, e copia che in altri manca, si dichiarano, e con proprietà convertono tutte le voci toscane in castigliano, e le castigliane in toscano ... opera utilissima. Composto da Lorenzo Franciosini fiorentino. Parte prima [-segunda parte]. Roma: a spese di Gio. Angelo Ruffinelli, & Angelo Manni, appresso Gio. Paolo Profilio.Suche in Google Scholar

Fündtler, Holland. 1622. Phraseologia germanica, oder Lustgärtlein, zierlich zureden und zuschreiben durch Holland Fündtlern. Strassburg: Gedruckt bey J. Reppen in Verlegung dess Authoris.Suche in Google Scholar

Gallicciolli, Giambattista. 1773. Fraseologia bibblica ovvero dizionario latino italiano della Sacra Bibbia volgata. Nel quale a modo dei vocabolari scolastici si trovano spiegate nel loro senso literale tutte le parole, frasi, idiotismi e altre locuzioni della S. Bibbia, ed in oltre il volgarizzamento dei passi oscuri e difficili. Venezia: Sansoni.Suche in Google Scholar

Gatti, Garibaldi Menotti. 1887. Deutsches lesebuch: primo libro di lettura tedesca, con traduzione italiana interlineare: fraseologia, prosa, poesia. Roma: Tip. Della R. Accademia Dei Lincei.Suche in Google Scholar

Geist, Eduard (1835): Aufgaben zum Uebersetzen aus dem Deutschen ins Lateinische. für die mittleren und oberen Classen der Gymnasien, entlehnt aus den besten neulateinischen Schriftstellern mit untergelegter Phraseologie, beständiger Verweisung auf die Grammatiken von Zumpt, Ramshorn. Grammatischen, stilistischen, synonymischen und antibarbaristischen Bemerkungen. Heyer: Gießen.Suche in Google Scholar

Gregorius, Thaumaturgus, Johannes Ökolampadius, Petrus Mosellanuset et al. 1520. IN ECCLESIASTEN SOLOMONIS METAphrasis Diui GREGORII Neocęsariẽsis Episcopi, interp̃te OECOLAMPADIO. Ex secunda editione vna cum P. Mosellani Epistola ac ipsius D. Gregorii Vita ex Suida eodẽ P. Mosell. interp̃te. Leipzig: Schumann.Suche in Google Scholar

Guildner, Emanuel. 1598. Officina scholastica, s. Phraseologia Ciceroniana latino-germanica, ex Ant. Scoro enucleata. Frankfurt a. M.: Palthen.Suche in Google Scholar

Harper, Douglas. 2001–2020. “Phrase”. Etymon-line. https://www.etymonline.com/word/phrase (accessed 04 January 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

House of Representatives. 1960. Massachussets. General Court. Santa Barbara: Library of the University of California. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1960-pt1/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1960-pt1-1–2.pdf (accessed 16 February 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Kohlhans, Johann Christoph. 2020 [1676]. Grammatica Hebraea literis hebraicis, punctis absentibus, expressa: Bibliis non-punctatis inserviens, & pueris inculcanda, & aetate provectiorum studiis properanda aptata; cum Vocabulario, Phrasiologia, & Syntaxi, biblicum libellum Ruth repraesentantibus: Hebraica punctis destituta docendi & discendi Methodo parata. Delhi: Pranava.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1676a. Il nuovo dizzionario delle due lingue italiana-tedesca e tedesca-italiana, amplificato di ricchissima fraseologia overo uso genuino e nazio de’ vocaboli, fornito de’ termini e locuzioni proprie di stato, di guerra, mercanzia. Opera compita, utilissima, e da molti desiderata. Distinta in due tomi, compilata con essattissima diligenza e fatica da’ più famosi scrittori. Da Mattia Kramer maestro delle lingue. Norimberga: alle spese di Morizio Wolfango e de gli heredi di Giovann’Andrea Endter, vol. I.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1676b. Del dizzionario italiano-tedesco, parte seconda. Fa parte di: Il nuovo dizzionario delle due lingue italiana-tedesca e tedesca-italiana, amplificato di ricchissima fraseologia overo uso genuino e nazio de’ vocaboli, fornito de’ termini e locuzioni proprie di stato, di guerra, mercanzia. Opera compita, utilissima, e da molti desiderata. Distinta in due tomi, compilata con essattissima diligenza e fatica da’ più famosi scrittori. Da Mattia Kramer maestro delle lingue. Norimberga: alle spese di Morizio Wolfango e de gli heredi di Giovann’Andrea Endter, 1676–1678, vol. 2.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1678. Das neue dictionarium oder wort-buch in teutsch-italianischer sprach: reichlichausgefürt mit allen seinen natürlichen redens-arten, wol versehen mit eigentlichen kunst-wörten in staats-kriegs-handels- und allen andern nahmhafften professionen der gantzen welt. Mit sehr grossem fleiβ und mühe aus den allerberühmtesten scribenten für die liebhaber beyder sprachen zusammengetragen, von Matthia Krämer, sprachmeister. Fa parte di: Il nuovo dizzionario delle due lingue italiana-tedesca e tedesca-italiana, amplificato di ricchissima fraseologia overo uso genuino e nazio de’ vocaboli, fornito de’ termini e locuzioni proprie di stato, di guerra, mercanzia. Opera compita, utilissima, e da molti desiderata. Distinta in due tomi, compilata con essattissima diligenza e fatica da’ più famosi scrittori. Da Mattia Kramer maestro delle lingue. Norimberga: alle spese di Morizio Wolfango e de gli heredi di Giovann’Andrea Endter, 1676–1678, vol. 3.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1691. Praxis Phraseologiae Italicae/Wegweiser zur Italiänischen Übersetz- und Componir-Kunst. Endter: Nürnberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1700. Il *gran dittionario reale, tedesco-italiano cioe tesoro della lingua originale ed imperiale teutonica, o alta-germanica, in duoi tomi distinta. Tale ch’ella viene parlata e scritta hoggidi alla Corte, Camera e Dieta imperiale. Parte prima [-seconda] opera compita, nuova e fondamentale; nella quale si propone, discerne e dichiara primieramente con bell’ordine alfabetico ciascuna radice. Fornita di ricchissima fraseologia, modi e cose considerabili della lingua e sapienza germanica, e toscano-romana. De’ veri e sodi fondamenti di essa nostra lingua tedesca, cioe prononcia e scrittura. Grammatica tedesca; composta con industria da Mattia Cramero. Norimberga: alle spese de’ figliuoli del fu Giovann’Andrea Endter, 1700–1702.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1712. Le vraiment Parafait Dictionnaire Roial, Radical, Etimologique, Sinonimique, Phraseologique & Syntactique François-Allemand pur l’une et l’autre Nation. Première Partie A-E. Nuremberg: Chez le Fils, & les Heritiers de feu Jean André Endter.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer, Matthias. 1724. Neu-ausgefertigtes Italiänisch-Teutsches Sprach- und Wörter-Buch, welches sowol mit allen eigentlich- und natürlichen Red-Arten, als ein vollständiges Werck, ben dieser dritten Auflage von dem Autore selbst. Nürnberg: in berlegung Joh. Andreä Endters Seel. Sohn, und Erben. Tit. parallelo: Il nuovo dittionario reale italiano-tedesco; fornito di richissima fraseologia, overo Uso genuino, proprio, e natio de’ vocaboli. Opera compita, in questa terza editione, dall’autore istesso riveduta, corretta. Compilata dal signor Mattia Cramero, delle lingue occidentali professore. Norimberga: alle spese di Morizio Wolfango e de gli heredi di Giovann’Andrea Endter, 1676–1678.Suche in Google Scholar

Lepri, Luigi. 2009. Bacajèr a Bulåggna. Fraseologia dialettale bolognese. Bologna: Pendagron.Suche in Google Scholar

Lissoni, Antonio. 1836. Frasologia italiana. Seconda Edizione ridotta in Dizionario grammaticale e delle italiane eleganze - Volume II D-L. Rifatta da capo, accresciuta di moltissime leggiadre frasi e specialmente di ogni insegnamento grammaticale venendo a tale oggetto stampata qui la parte più importante della seconda edizione della Grammatica del Signor Canonico Don Ferdinando Bellisomi, 2nd edn. Milano: Pagliani.Suche in Google Scholar

Maier, Michael. 1618. Tripus Aureus, hoc est, Tres Tractatus Chymici Selectissimi, nempe I. Basilii Valentini. Practica una cum 12 clavibus & appendice, ex Germanico; II. Thomae Nortoni, Angli Philosophi, Crede mihi seu Ordinale, ante annos 1400 ab authore scriptum, nunc ex Anglicano manuscriptum in Latinum translatum, phrasi cuiusque authoris ut sententia retenta; III. Cremeri cuiusdam Abbatis Westmonasteriensis Angli Testamentum, hactenus nondum publicatum, nunc in diversarum nationum gratiam editi, & figuris cupro affabre incisis ornati opera & studio. Frankfurt: Paul Jacob for Lucas Jennis.Suche in Google Scholar

Malatesta Garuffi, Giuseppe. 1720. Frasario italiano nuovo, e copioso di varji, ingeniosi e pellegrini traslati, metafore e frasi, con moltissime voci di buona proprietà estratte dal vocabolario della Crusca, per facilitare nel linguaggio italico. Venezia: Poletti.Suche in Google Scholar

MED = The Middle English Dictionary (1100–1550). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary (accessed 05 February 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Montemerlo, Giovanni Stefano. 1566. Delle phrasi toscane libri XII. Fratelli Franceschini: Venetia.Suche in Google Scholar

Meissner, Carl. 1880. Lateinische Phraseologie für die oberen Gymnasialklassen / von Dr. Carl Meißner. Leipzig: Teubner.Suche in Google Scholar

Milesi, Giorgio & Maurizio Gotti. 1980. [English ad hoc] manuale di nomenclatura, fraseologia e conversazioni per l’uso della lingua viva. Per chi viaggia e per chi studia = Manual of Vocabulary, Phraseology and Conversations for the Use of the Living Language. For the tourist and the student. Bergamo: Atlas.Suche in Google Scholar

Monosini, Angelo. 1604. Flos Italicae linguae. Venetiis: Guerrilium.Suche in Google Scholar

Mutinelli, Fabio. 1851. Lessico veneto: che contiene l’antica fraseologia volgare e forense, l’indicazione di alcune leggi e statuti, quella delle varie specie di navigli e di monete, delle spiaggie, dei porti e dei paesi gia esistenti nel Dogado / compilato, per agevolare la lettura della storia dell’antica Repubblica Veneta, e lo studio de’ documenti a lei relativi, da Fabio Mutinelli. Venezia: Andreola.Suche in Google Scholar

Mutinelli, Fabio. 1852. Lessico veneto: compilato per agevolare la storia dell’antica repubblica veneta e lo studio dei documenti ad essa relativo. Venezia: Andreola.Suche in Google Scholar

Neander, Michael. 1558. Phraseologia Isokratike Ellenikolatine. Phraseologia Isocratis Græcolatina: id est, Phraseon sive locutionum, elegantiarum ve Isocraticarum loci, seu indices numerosissimi & copiosissimi græcolatini, ex ipso Isocrate rhetore suavuis. & eloquentissimo observati & collecti. Per Michaelem Neandrum Soraviensem. Basileae: Ioann. Oporinum (Basileae: ex officina Ioannis Oporini).Suche in Google Scholar

Percolla, Vincenzo. 1870. Piccola fraseologia italiana. Catania: s.n.Suche in Google Scholar

Percolla, Vincenzo. 21889. Piccola fraseologia italiana, ovvero scelta di frasi eleganti italiane ad uso della gioventù studiosa, con un elenco di voci e modi erronei da evitarsi nelle scritture italiane. Catania: Concetto Battiato Edit., Tip. Carmelo Galati.Suche in Google Scholar

Petrini, Podalirio. 1888a. Correspondance commerciale suivie d’un grand nombre de thèmes, d’un recueil des termes les plus usités dans le commerce et d’une phraseologie à l’usage des écoles d’Italie. Milan : Galli et Raimondi.Suche in Google Scholar

Pesenti Del Thei, Francesco. 1941. Conversando. Fraseologia italiana-tedesca. Venezia: La Borsa del Libro.Suche in Google Scholar

Pfeifer, Wolfgang, Wilhelm Braun, Gunhild Ginschel, Gustav Hagen, Anna Huber, Klaus Müller, Heinrich Petermann, Gerlinde Pfeifer, Dorothee Schöter & Ulricht Schröter (eds). 1993. Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen (1993), digitalisierte und von Wolfgang Pfeifer überarbeitete Version im Digitalen Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. https://www.dwds.de/wb/etymwb/Phraseologie, (accessed 07 May 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

“Phraseology”. 2021. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/phraseology (accessed 07 May 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Pielat, Barthelemy. 1673. Octoglotton ou phraseologie en huict langues sçavoir en françois, latin, espagnol, portugais, italien, alemand, flamand & anglois. Iacob Velsen. Amsterdam: Voor Jacob Lescailje Boeckerkooper op den Middel-dam.Suche in Google Scholar

Pignata, Giuseppe. 1776. Les avantures de Joseph Pignata das ist Joseph Pignata merkwurdige begebenheiten von unzähligen Druckfehlern gereiniget und zum Behuf der Anfänger in französischer Sprache mit einer zulänglichen Phraseologie versehen. Frankfurt – Leipzig: Monath.Suche in Google Scholar

Pirrone, Nicola. 1907. Fraseologia ciceroniana ad uso delle scuole classiche. Milano – Palermo – Napoli: Sandron.Suche in Google Scholar

Probst, Hermann. 1868. Locutionum latinarum thesaurus oder lateinische Phraseologie, zum Gebrauch bei den Lateinischen Stilübungen in den oberen Gymnasialklassen. Koln: Du Mont-Schauberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary. 2010. “Legal phraseology”. https://www.thefreedictionary.com/phraseology, (accessed 06 December 2020).Suche in Google Scholar

Reynell, Carew W. 1564. Tales, and Quick Answeres: Very Mery, and Pleasant to Read. Chicago: University of Chicago.Suche in Google Scholar

Richards, William. 1798. Geiriadur Saesneg a Chymraeg [microform] An English and Welsh Dictionary, in which the English Words, and sometimes the English idioms and phraseology are accompanied by those which synonomise or correspond with them in the Welsh language. The whole carefully compiled. Carmarthen: J. Daniel.Suche in Google Scholar

Robertson, William. 1686. Phraseologia generalis; continens, quæcunque sunt scitu necessaria, & praxi, usuique studiosorum philologicorum, maxime utilia, in cunctis operibus phraseologicis, anglico-latinis, seu latino-anglicanis, hucúsque, hîc, in lucem editis. A Full, Large, and General Phrase Book; comprehending, Whatsoever is Necessary and most Usefull, in all other Phraseological Books. Cambridge & London: Hayes.Suche in Google Scholar

Rogers, David Morrison. 1582. English Recusant Literature. Vol. 267. Ilkley: The new Testament. Scholar Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Scampuddu, Mario & Maria Demuru 2006. Fraseologia gallurese. Repertorio di locuzioni e modi di dire. Taphros: Olbia (SS): Taphros.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmitz, Bernhard. 1872. Deutsch=französische Phraseologie in systematischer Ordnung. Ein Übungsbuch für jedermann, der sich im freien Gebrauche der französischen Sprache hervorkommen will. Greifswald: Tischer.Suche in Google Scholar

Schoensleder, Wolfgang. 1619. Promtuarium germanico-latinum. Apergeri.Suche in Google Scholar

Schore, Antonius. 1609. Phraseologia linguae Latinae, seu Ratio obseruandorum eorum in auctoribus legendis, quae praecipuarum ac singularem vim aut vsum habent. Cum dialogo doctissimo, Antonio Schoro auctore. Infinita phrasium farragine aucta, polita, & emaculata, a Iacobo Cellario Augustano. Francofurti: E Collegio Musarum Paltheniano, 1609 (Impressum Darmbstadii: per Balthasarem Villicum, sumptibus D. Zachariae Palthenii, bibliop. Francof.).Suche in Google Scholar

Schultheis, Johann. 1593. Phraseologia: Qua Ostenditur, Cum Vocabula, tum modos loquendi vsurpare Caluinistas, in Ecclesia Christi vsitatos: alia tamen significatione, quàm par est, vut imponant incautis. Conscripta, Vt simpliiores abe impostorum hominum Additis testimonijs De orali & impoiorum manducatione. Smalcaldiae: Schmuck.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, J. 1674. Grammatica Quadrilinguis: or brief instructions for the Franch, Italian, Spanish, and English Tongues. With the Proverbs of each Language, fitted for those who desire to Perfect themselves therein. London: Newman.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorger, Jakob. 1625. Phraseologia Homerica ex Iliade & Odyssea, opere humani ingenii, de Alexandri Magni iudicio, longe praeciosissimo, Studio atque opera M. Iacobi Sorgeri Schleusingensis. Ill. Francofurti: Scholae patriae Rectoris Francofurti, sumptibus Ioannis Flitneri.Suche in Google Scholar

Spadafora, Placido. 1688. Phraseologia seu Logodaedalus, vtriusque linguae, Latinae, ac Romanae, adolescentibus, rhetoricae candidatis, facem praeferens, Placidi Spathaphori eSocietate Iesu opera studioque accensam. Panormi: Typis Petri Coppuli impressoris Camer, vol. I.Suche in Google Scholar

Spezia, Endimio. 1899. Terminologia e fraseologia commerciale italiana-francese, colla nomenclatura delle principali merci nelle due lingue: manuale pratico pei commercianti e per le scuole di commercio. Cremona: Leoni.Suche in Google Scholar

Ulsenius, Theodorich. 1496. De pharmacandi comprobata ratione: medicaru[m] simplicium rectificatione, symptomatu[m] purgationis hora supervenientiu[m] eme[n]datione libri II / per Theodoricum Ulsenium carmine conscripti; nunc primum Georgii Pictorij Villingani scholijs illustrati; quibus accedit Q. Sereni Samonici, poëtica phrasi, de omnium morborum cura D. Pictorii commentarijs breviter explanatus. Nürnberg: s.n.Suche in Google Scholar

Valentini, Maria Grazia (ed.). 1993. Blitz: manuale di fraseologia. Allegato al v.: Dizionario multilingue italiano-inglese-francese-tedesco-spagnolo. Selezione dal Readerʼs digest: Milano.Suche in Google Scholar

van Campen, Joannes & Joannes Baptista Pederzanus. 1533. Svccinctissima & quantum phrasis Hebraica permittit, ad litteram proxime accedens, paraphrasis in concionem Salomonis Ecclesiastæ. Venetia: Venetiis ex officina Ioannis baptistæ pederzani.Suche in Google Scholar

Vladerassus, Christophorus & Christophe Plantin. 1586. Formulae Ciceronianae epistolis conscribendis vtilissimae. Antverpiae: Ex officina Christophori Plantini.Suche in Google Scholar

Westheimer, Bartholomäus & Johann Setzer. 1528. Bibliorum phrasis sancta. Ex piis iuxta ac eruditis, tam priscorum quam recentiorum theologorum lucubrationibus innumeris adcurate, & ad uerbum quidem excerptae, sectiones duae. Hagenau: Setzer, Gewendtheit im Styl. Wien: Heubner.Suche in Google Scholar

Widmer Gotelli, Emma. 1895. Saggio di fraseologia tedesca a riscontro dell’italiana: Vade-mecum dello studente di Lingua tedesca. Compilato da Emma Widmer Gotelli e dedicato alle sue alunne della Scuola superiore femminile E. Fuà Fusinato. Roma: Tip. Voghera.Suche in Google Scholar

Zoni, Giulio Cesare. 1859. Prontuario di fraseologia francese: con la traduzione di fronte / operetta compilata da Giulio Cesare Zoni; con aggiunta di locuzioni viziose e gallicismi, di esercizi pratici e mnemonici sopra varie altre difficolta della lingua. Piacenza: Porta.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial (English)

- Editorial (Deutsch)

- Articles

- The origins of the term “phraseology”1

- Morphemic and Syntactic Phrasemes

- “Shall I (compare) compare thee?”

- Ni as the introductory particle for expressions of negation in three dialectal variants of Spanish

- Kommunikative und expressive Formeln des Deutschen in Internettexten: ein diskursorientierter Ansatz

- Phrasal verb vs. Simplex pairs in legal-lay discourse: the Late Modern English period in focus

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews