Abstract

The study analyses the use of a bipartite construction that serves as a resource for the ad hoc establishment of personal categories, and thus, for social positioning. In particular, it examines the Spanish construction “hay gente que …” and the German equivalent “es gibt Leute, die …,” which translate into English as “there are people who …”. The first conjunct asserts the existence of a social category, which is then specified attributively in the second conjunct. After a short characterisation of the construction, the analysis focuses on its functions from an interactional-linguistic perspective. Two ways of using the construction for positioning are identified: (1) to relate individuals to categories, i.e. oneself or others can be ‘ascribed to’ or ‘distanced from’ a certain category; (2) to modify presupposed categories by reevaluating or deconstructing them. The study is based on Spanish and German conversation data, taking a cross-linguistic perspective.

1 Introduction

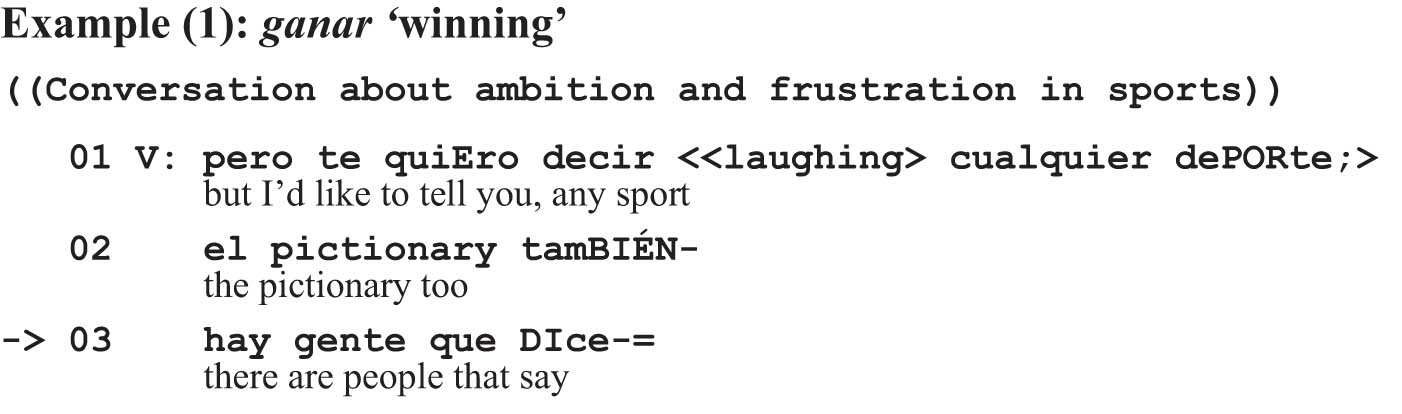

This article examines a bipartite grammatical construction that is part of the family of existential constructions. This bipartite construction invokes a personal category by postulating its existence and then naming its essential characteristics. The construction will be studied in both Spanish and German, and can be represented schematically as follows: hay/es gibt (Engl. ‘there are’) + human mass noun + attributive. In conversation, the social category established with the construction can be used to position oneself, that is, the speaker, or others, namely, the interlocutor(s) or third parties. This interactive work on identity is illustrated by the following two examples. In example 1, ganar, the speaker V distances herself from excessive ambition in sports and games.

The speaker establishes a category of people who are bad at losing. The attribution is made through an instance of typified animated speech with excited exclamations in which this type of player shows a competitive attitude and is very concerned with winning: hay gente que DIce- Ay: diO:s AY::; nos están por gaNAR; ‘there are people that say: oh God oh, they’re about to beat us’ (l. 03–05). In contrast to this negative categorisation of others, V positions herself as someone who does not care about winning or losing, i.e. who is less competitive (l. 06).

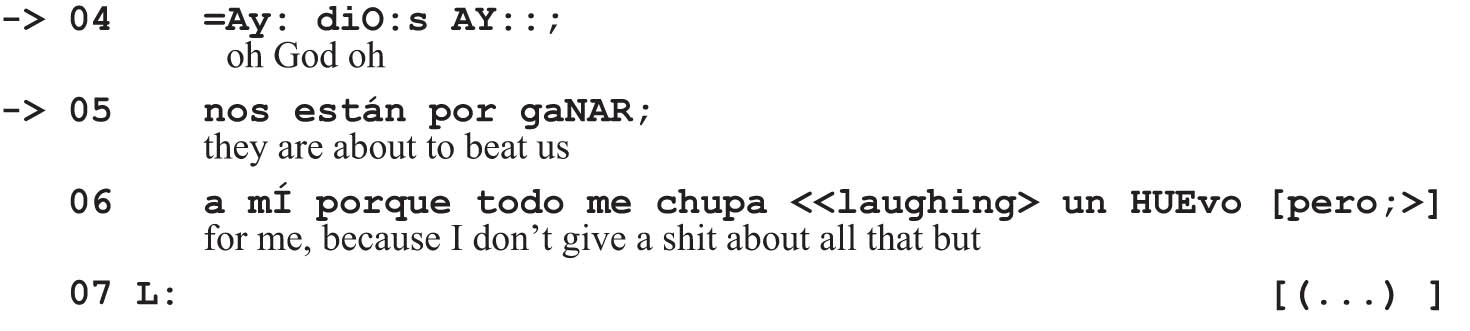

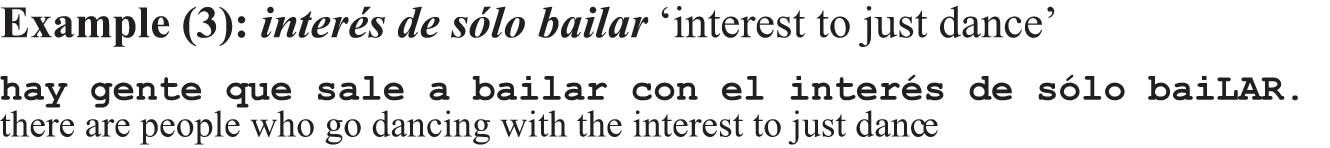

In example 2, the participants discuss the attractiveness of large bust sizes. While the men state that they find them unattractive, Vio doubts their statements in view of the fact that the media is full of images of busty women.

The construction occurs twice here: es gIbt solche typen; die STEHN da drauf; ‘there are such guys they like that’ (l. 02 04) and ja det jIbt schon leute die et MÖgen. ‘yes there are people who like it’ (l. 16). The existence of a category of men who like bustiness is acknowledged, but the participants Ant and Mik personally distance themselves from it by stating that they do not share this preference (e.g. l. 05, 07, 10). In the immediate context of use, an other-positioning of third parties and a self-positioning are simultaneously carried out.

With the purpose of investigating the functional potential of existential-attributive constructions (hereafter ‘EA constructions’) for positioning, a collection of 74 German and Spanish examples was compiled. Our main goal is to answer the following research question: What conversational functions does the construction fulfil, especially in terms of positioning oneself and others? To achieve this aim, we will analyse the context-sensitive use of the construction, based on the theoretical framework of Interactional Linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018).

After having situated the phenomenon in the introduction, in Section 2 the concepts of ‘social categorisation’ and ‘positioning’ are introduced. Section 3 explains the data set on which the study is based and the methodological approach. Section 4 characterizes the construction from the perspective of Construction Grammar. Subsequently, Section 5 presents the analysis of the construction, regarding its use for developing categories and positioning in interaction. The results are summarised and discussed in Section 6. The article ends with a conclusion in Section 7.

2 Social categorisation, identity, and positioning

This study has two conceptual points of reference: positioning and social categorisation. Within conversation analysis, the concept of social categorisation goes back to Harvey Sacks (e.g. Sacks 1972, 1979). The term membership categories (Sacks 1995), coined in the 1960s, covers linguistic forms whose referents imply social affiliations, e.g. mother, child, etc., which are simultaneously integrated into further, higher-level categories (membership categorisation devices). However, the categories are not simply classificatory sets, but are associated with category-bound activities. Sacks uses an example from a short children’s book: The baby cried. The mommy picked it up. Baby and mommy are categorial components of larger units (such as family or genealogy). This leads to the assumption that the short scene described involves the mother of the crying baby, even if the text does not explicitly specify this relationship. The assumption is supported by the category-typical actions mentioned, ‘baby – cry’ and ‘mother – pick up baby,’ in combination with the use of definite articles. Categories have a rather diverse range; according to Sacks, there are basic collections (1995, 41), which allow a categorisation of all members of society, e.g. by age, gender, denomination, nationality, while others are less basic, e.g. car driver, newspaper reader, etc.

Hausendorf (2000a, 4) defines social categorisation as the process of establishing and organising membership (cf. also ‘typification’ according to Berger and Luckmann 1980), and thus focuses on its interactive accomplishment: how membership determination is put into practice linguistically, thereby becoming visible and observable. Categorisation activities become analytically accessible through Hausendorf’s triad ‘assigning, ascribing, evaluating’ (‘Zuordnen, Zuschreiben, Bewerten’; Hausendorf 2000a, 16; see also Hausendorf 2000b). Assigning, the core function of categorisation, concerns the representation of group membership (e.g. by using category names). This is often accompanied by ascribing, e.g. determining group-specific characteristics, and evaluating, e.g. expressing attitudes with regard to group membership and group-specific characteristics (2000a, 23–24). While Hausendorf’s focus is more on the use of established categories (West Germans and East Germans, in particular), the categories and their characteristics analysed here are mainly established, ascribed, and evaluated ad hoc. In the talk preceding or following the use of the EA construction, the categories are negotiated and developed further interactively.

Positioning via categorisation is clearly related to identity work. In conversation analysis, identity is not conceptualised as essential characteristics of an individual but rather as a display of belonging to social groups. This can be determined in a variety of ways, e.g. via the categories of ethnicity, nationality, gender, subculture, milieu, leisure activities, denomination, etc. Antaki and Widdicombe (1998), who studied speakers’ work on identity-relevant categorisation in conversation, conceive of “a person’s identity as his or her display of, or ascription to, membership of some feature-rich category” (Antaki and Widdicombe 1998, 2). Thus, the process of identity construction appears as an interactive achievement in discourse, as a joint product of social practice.

From a similar perspective, the concept of ‘positioning’ considers identity-relevant phenomena (Bamberg 1997, 2008, Bamberg and Georgakopoulou 2008, Georgakopoulou 2006), with a strong focus on narratives. Lucius-Hoene/Deppermann present the following definition (see also Antaki and Widdicombe 1998, Wolf 1999):

Positioning, in the first place, very generally refers to the discursive practices through which people constitute and present themselves and others in verbal interactions in relation to each other as persons, claiming and ascribing roles, qualities, and motives through their actions. These, in turn, are functional to the local construction and representation of identity in talk-in-interaction. (Lucius-Hoene and Deppermann 2004, 168; our translation, OE and KB)

The relevance of social categorisation (in Hausendorf’s sense) for positioning is evident from the quote: a discursive practice for positioning can consist of social categorisation (i.e. assigning and/or ascribing and/or evaluating). Such categorisation can be carried out in relation to oneself and others, e.g. I can categorise myself, the interlocutor(s) or third parties. In fact, categorising others always implies self-categorisation and vice versa. Deppermann (2013b, 62) concludes that “membership categorisation is a core element of positioning” when it comes to “invoking, ascribing and negotiating identities” (ibid.: 63).

The categories considered by Sacks and also Hausendorf are part of the shared knowledge of a community and inferentially available. In contrast, the categories evoked by the EA construction are established ad hoc, explicitly naming their category-constitutive feature(s).

In this study, categorisation is understood in a broad sense as the ‘relating’ of a person to a category. This can consist not only in ascribing oneself or others to a category, but also – as seen in the two introductory examples 1 and 2 – in distancing oneself or others from a category. This study shows that EA constructions serve to postulate social categories that are dynamically adapted to the context and used for the positioning of others and oneself. Such categories are both invoked and modified or contoured locally. In particular, the activity of categorising consists of two (or more) participants establishing categories in a current conversation by ascribing attributes made up of characteristics, actions or dispositions, or a combination of these (Günthner and Bücker 2009, Birkner 2006, Deppermann 2013a, b).

Before a more detailed characterisation of the EA construction (Section 4), the data and methodological approach are presented in Section 3.

3 Data and methodology

The collection was built based on a corpus covering different types of interactions in German and Argentine Spanish: interviews, everyday conversations, and institutional talk. With the help of database and concordance programs [moca] (Ehmer and Martinez 2014), and the Aligned Corpus Toolkit (Ehmer 2023a, b), the corpora were searched for instances of the construction. First, searches were run for the word chains es gibt … die and hay … que.[1] In a second step, instances including a personal mass noun (such as Leute/gente ‘people,’ Menschen ‘men/humans,’ personas ‘persons,’ etc.) were selected.

Human mass nouns have the highest potential for creative category establishment due to their low semantic projection, which is constitutive for the EA construction. Accordingly, we excluded instances with attributes in the first conjunct that perform a restrictive operation on the noun (hay gente grande ‘there are elderly people,’ es gibt viele Leute ‘there are many people,’ hay gente así ‘there are such people,’ es gibt ehrgeizige Menschen ‘there are ambitious people’). Instances with particles and sentence adverbs were included in the analysis, as these modalisations do not impose any semantic restriction on the noun but rather have argumentative-modalising functions. This is clearly illustrated by the above example (2, l. 16) det JIBT schon leute; ‘there are PRT people,’ where the particle schon marks a concession towards the other participant’s opinion but does not perform any restriction on the referent noun.

The assumption that there might be functional differences between uses of the construction in the two languages soon proved inaccurate, and a contrastive perspective was determined to be inappropriate. Therefore, we will present a cross-linguistic characterisation of the construction in both languages.

In total, the study is based on 74 examples (36 in German and 38 in Spanish) that distribute across the different interaction types as follows:

Interviews: 6 instances in German, 24 instances in Spanish

The Spanish interviews were conducted with Argentine tango dancers and teachers; the German interviews originate from a project on dialect intonation. All interviews, especially the German ones, have a strong focus on autobiographical topics.

Everyday conversations: 27 instances in German, 13 instances in Spanish

For the German data, the BigBrother corpus (Birkner 2001) was used, containing video recordings from a German reality TV show. The Spanish data were drawn from the cespla (Ehmer 2008), a corpus of Spanish everyday conversations from Argentina audiorecorded in 2006/2007.

Therapy/counselling conversations: Three instances in German, one instance in Spanish

The German therapy conversations were collected as part of project on the ‘The psychotherapeutic treatment of somatoform disorders in the context of the psychosomatic consultation and liaison service’ at the Freiburg University Medical Centre. During the inpatient stay in an acute somatic hospital, the patients received up to five therapy sessions as part of comprehensive diagnostics to clarify their physical complaints (Birkner and Burbaum 2013). The Argentine radio call-in is comparable to the therapy conversations insofar as it comes from a counselling program in which the callers – usually rather monologically – tell the presenter about current problems and receive advice and encouragement from her.

The construction is common in both Spanish and German but measuring its relative frequency of use in the two subcorpora reveals that it occurs four times more often in Spanish (8.24 instances per 100,000 words vs German 2.06 instances per 100,000 words). This can possibly be explained by the fact that the existential construction hay X ‘there are’ (even without an attributive) is generally very common in Spanish. The relative frequency of the construction also differs according to the type of discourse: in everyday conversations, its use is eight times higher in Spanish than in German (Birkner and Ehmer 2014, 283f). In addition, the construction is used more frequently in both languages in the interviews − and thus in more monologue-based contexts − than in the other types of conversation. However, due to the lack of balanced corpora, differences in frequency of use were not pursued further.

4 Characterisation of the EA construction

In construction grammar, it is assumed that grammatical structures are symbolic form-function units whose meanings are not derived from the sum of the individual components. They are represented cognitively as holistic forms of varying complexity, known as constructions (Östman and Fried 2004, Goldberg 1995, Hoffmann and Trousdale 2013). Constructions can be described on the linguistic levels of syntax, morphology, phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics (cf. in particular, the work of Haiman and Thompson (1988) and Lambrecht (1988, 1994)). The cognitive modelling of grammar is not the main focus here (cf. Langacker 2008, 2009, among others). Instead, the pragmatic aspect of constructions will be considered. The level of pragmatics is still rather underrepresented in most descriptions of construction grammar (but see e.g. Günthner and Imo 2006, Fischer 2006, Deppermann 2006, Ehmer 2022), even though it is clear that grammatical constructions are used by speakers as a resource for the organisation of social lifeworld, amongst other things (see for example, the contributions in Günthner and Bücker 2009). For instance, Birkner (2006) analyses the so-called MENSCH-construction.[2] This is also a bipartite construction used for social categorisation, which is linked to the EA construction in a constructional network (see also Birkner and Ehmer 2014, Diessel 2019).

The bipartite structure of the EA construction was already described in the introduction:

First Conjunct: Hay/Es gibt + Human Mass Noun,

Second Conjunct: Attributive.

The assertion of existence takes place in the first conjunct (C1) through the fixed expression Hay/Es gibt ‘there are.’ A pronoun binds the second conjunct (C2), which semantically fills the still unspecified category by means of a restrictive attribute:

Cf. example (2), l. 16: ja det jIbt schon leute die et MÖgen- ‘yes there are PRT people who like it’

Cf. example (2), l. 02, 04: =ja es GIBT solche typen; die STEHN da drauf; ‘yes there are such guys; they like that’

In German, a change in subordinative syntax can occur, as in l. 04. The semantic specification is realised here with non-subordinative syntax, hence the connector must be analysed not as a relative but as a demonstrative pronoun. This is facilitated by the fact that the connectors are identical on the level of form in German (die relative pronoun vs die demonstrative pronoun).

The following diagram summarises the relations between conjuncts:

The slot of the ‘human mass noun’ is typically filled in German with the lexemes Leute, Menschen, Typen ‘people, humans, guys’ and in Spanish with gente, personas, tipos ‘people, persons, guys’. Leute and gente are the most frequent forms in the corpus (28 occurrences each in German and Spanish), followed by Menschen in German (7 occurrences) and personas in Spanish (4 occurrences).

All other lexemes – for instance Tänzer/bailarines ‘dancers’ or Kinder/chicos ‘kids,’ Mädchen/chicas ‘girls’ – only occur once. Although this less frequent appellatives are human mass nouns, too, they are characterised by a narrower scope of reference compared to Leute/gente, etc. The analysis focuses on examples containing the human mass nouns listed in Diagram 1, which are most frequent and can thus be considered prototypical instanciations of the construction.

Schematic representation of the EA construction

| C1 Existential construction | C2 Attributive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Mass Noun | connector | Actions/Dispositions/Characteristics | ||

| Spanish | Hay | gente, personas, tipos... | que relative pronoun | |

| German | Es gibt | Leute, Menschen, Typen… | die relative-/demonstrative pronoun | |

In C2, the personal category is established through the naming of features which can consist of actions, characteristics, or dispositions. The specification of the category can be realised with varying degrees of complexity, both in terms of syntax and semantic richness. The following examples illustrate typical examples of both languages.

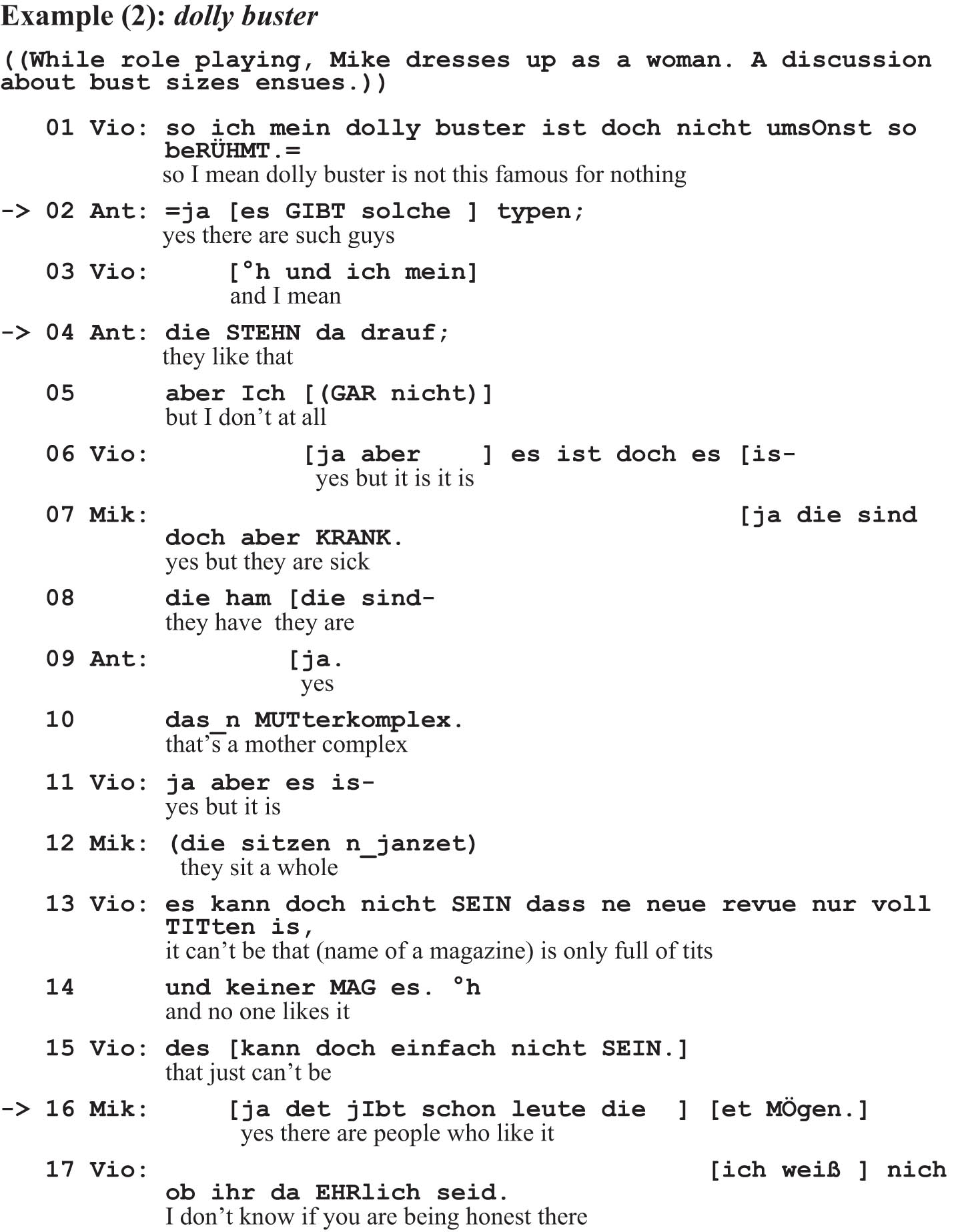

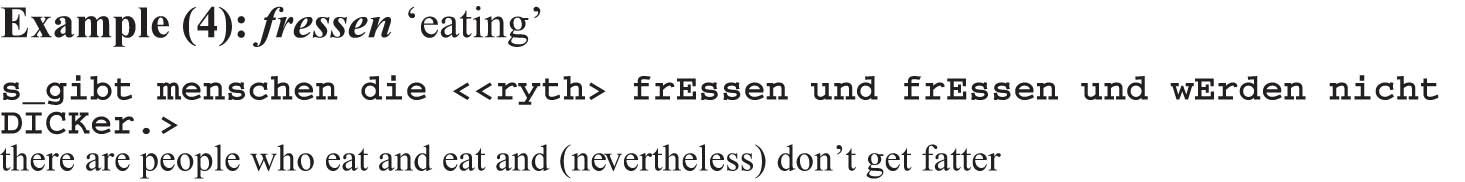

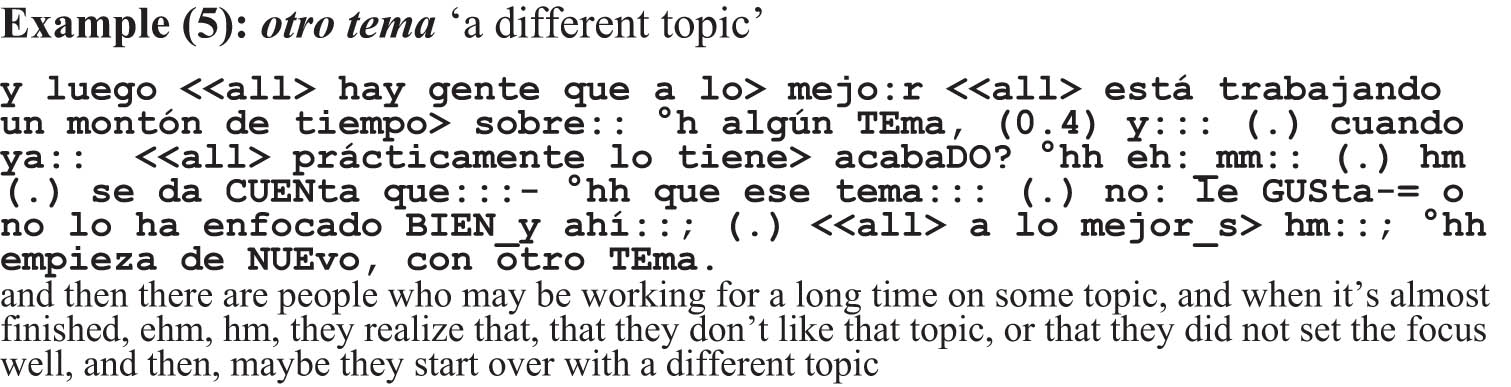

In example (3), the speaker uses a simple clause in C2 to formulate a feature that constitutes the personal category (sale a bailar con el interés de sólo baiLAR. ‘there are people who go dancing with the interest to just dance’). C2 can also be more complex and contain combinations of clauses. In Example (4), two clauses are joined by the connector ‘und’ and (frEssen und frEssen und wErden nicht DICKer. ‘eat and eat and (nevertheless) don’t get fatter’). In the context of the conversation, the two features represent a concessive semantic relation, based on the participant’s presupposition of everyday knowledge that someone who eats a lot usually gets fatter. Going beyond the combination of two propositions, C2 may also contain more complex or even narrative descriptions, such as in example (5). Such scenic developments can also include animated speech (Ehmer 2011), as in example (1) presented in Section 1.

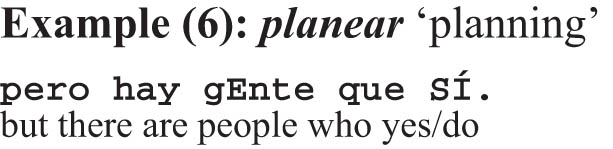

One advantage of establishing categories through animated speech is the possibility of conveying an immediate performative impression of the category-constitutive action. In such performances, the category cannot be semantically traced back to single, clearly formulated features but is rather developed holistically. In addition to the explicit naming of category-constitutive features, there is also the possibility of retrieving them from the preceding conversational context via anaphoric reference. For instance, in example (6), C2 only contains the response particle sí ‘yes.’ What the category-constitutive feature actually consists of only becomes apparent when considering the preceding context. The participants have just agreed that they cannot plan far into the future (they can at most do so until the day after tomorrow). This negated feature is contrastively taken up by the use of the affirmative particle sí ‘yes’ and becomes the category-constitutive feature of the personal category.

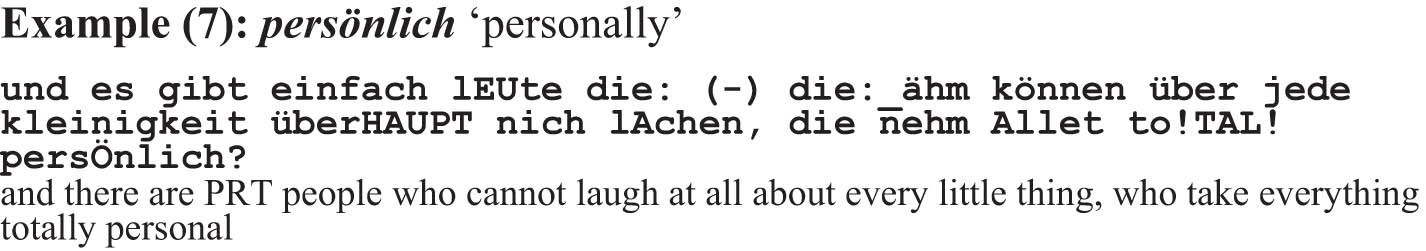

While in this example the complete feature has to be searched for in the preceding context, there are also cases where only part of the semantic specification has to be retrieved from context. In addition to using a single C2, it is also common in our data for speakers to syntactically realise multiple C2’s. For such multiple realisations, speakers make use of the C1 produced shortly before, retracting to the relevant connector (‘structural latency,’ Birkner and Ehmer 2014, Auer 2015). This is the case in Example (7), where the speaker first produces a complete instance of the construction and then reuses the syntactic structure starting with the connector (die nehm Allet to!TAL! persÖnlich? ‘who take everything totally personal’). Thereby he adds a semantic feature and defines the category more precisely. Structural latency can also be used by several participants to jointly develop and negotiate a category. After one speaker establishes the category, a second speaker can take up the structure, retract to the end of C1 and add a matching C2 (cf. 5.2.1 for a detailed analysis).

5 Functional use of the construction in context

This section examines the use of the EA construction in the sequential course of the conversation and its pragmatic functions, focusing specifically on the types of categorisations it achieves. A central aspect of the concept of membership categorisation device developed by Harvey Sacks in the 1960s is that members of social communities ascribe themselves and others to personal categories (Sacks 1995), and that social identity can be established through this process (Section 2). At the same time, a fundamental process of identity construction lies in distancing from ‘others’ (Raible 1998, Hausendorf 2000a), whether these are concrete persons, social groups or even personal categories. We refer to this basic function of EA constructions as relating (5.1), i.e. establishing ad hoc a social personal category to which real persons are related in order to (more or less explicitly) ascribe them to the category (5.1.1) or distinguish them from it (5.1.2).

A second use of EA constructions is that of modifying (5.2). It involves changing a personal category that was made relevant in the course of the conversation. Previously relevant personal categories can be re-evaluated (5.2.1), but they can also be dissolved by using the EA construction to develop a personal category in which characteristics that were explicitly mentioned or merely presupposed earlier in the conversation are combined in an ‘unexpected way’ (5.2.2).

5.1 Relating persons to categories: Ascribing or distancing

This section will show how EA constructions are used to ascribe a person to a category or distance them from it. Starting with explicit and unambiguous ascriptions and distancings, cases in which this occurs more implicitly will also be discussed. In the following example, the EA construction is used to establish a personal category in relation to a particular but absent person.

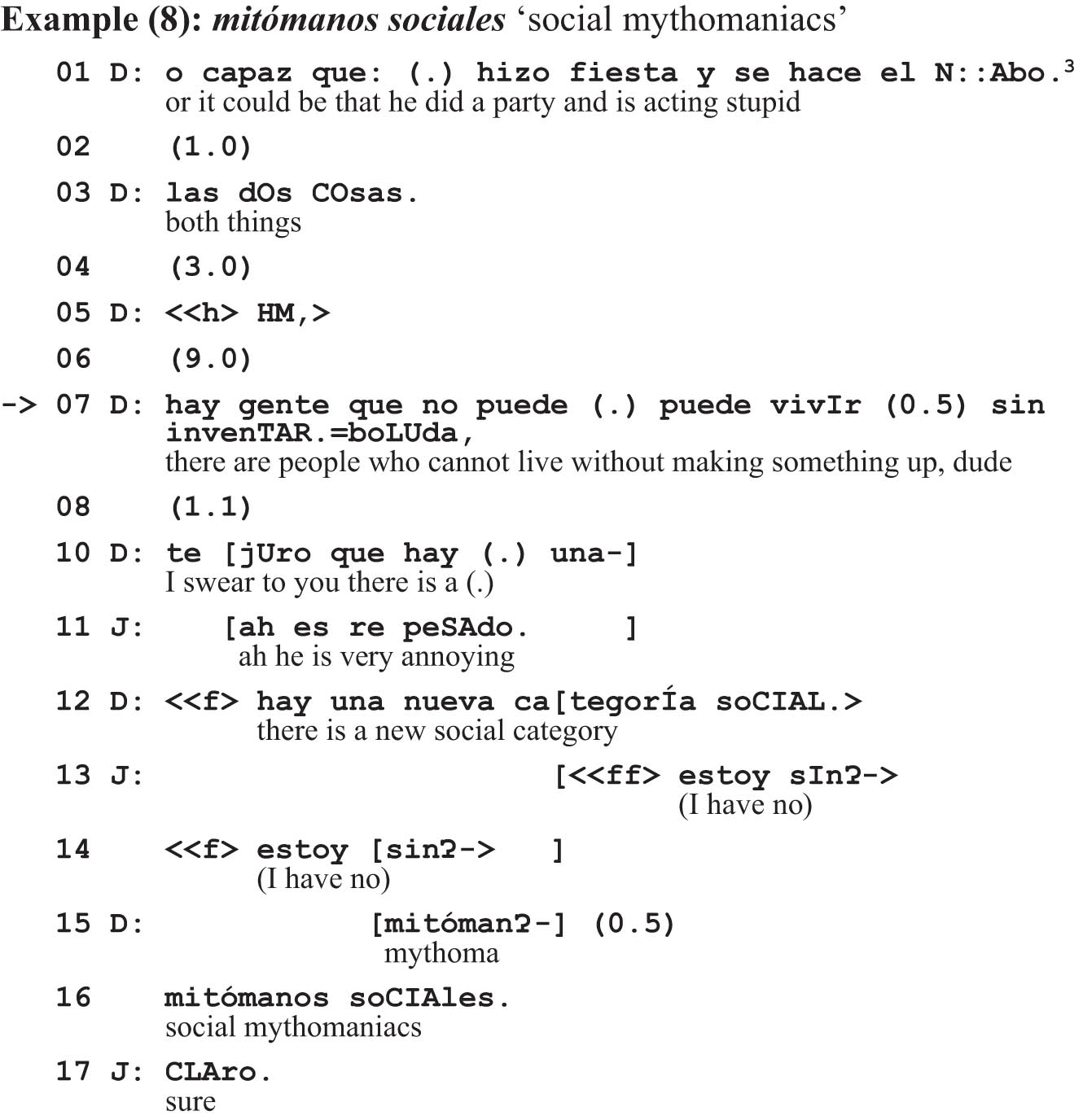

5.1.1 Ascribing oneself or others to a category

Speaker J tells her friend D about an encounter with a fellow student, F, who claimed to have completed his studies. Neither D nor J are able to believe this, partly because they remember him to be a bad student. In response to J’s somewhat insidious question as to why he had not celebrated his graduation (to which they would normally have been invited), F had replied that he had only celebrated in a small circle. J and D also find this hardly credible. D finally speculates that F either did not graduate at all or held a party without inviting them. This is where the transcription begins.

D’s speculations about the situation[3] (l. 01–03) are followed by a pause in the conversation (l. 04). She then signals wonder about it with <<h> HM, > (l. 05), which is followed by another long pause (l. 06). Finally, D takes the floor again and asserts the existence of a category of people with the utterance hay gente que no puede (.) puede vivIr (0.5) sin invenTAR. ‘there are people who cannot live without making something up’ (l. 07). Here, the category is specified by means of the feature (+ not being able to live without making something up) attached to the restrictive attribute of the relative clause. There is no recourse to a common social category, but rather to a generalised type of person who is abstracted from a concrete individual case and given the status of a category.

Looking at the establishment of the category in its sequential context, it becomes clear that the conclusion is based on the previous description of the encounter, i.e. the questionable fellow student is implicitly ascribed to the postulated category. The further continuation is particularly informative: te juro que hay una-: (l. 10) and <<f> hay una nueva categorÍa soCIAL.> ‘I swear to you there is a (.) there is a new social category’ (l. 12). The group of people that D had previously specified attributively with the characteristic of an indomitable urge to make things up is now given a striking label: mitÓmanos soCIAles ‘social mythomaniacs’ (l. 16), who, one may well assume, base their social status on tall tales. At this point, J agrees (CLAro. ‘sure,’ l. 17) and ratifies the category developed by D. This closes the topic and the conversation turns to the network connection of J’s cell phone.

In the passage just analysed, a category formation arises in a specific context. The example shows how two interlocutors jointly perform an explicit other-positioning of a third party (ascribing) as well as an indirect self-positioning (distancing). Subsequently, the designation of the category – explicitly referred to as ‘new’ – with an ad hoc appellative (‘social mythomaniacs’) makes the ongoing categorisation activity particularly evident.

The negative evaluation refers to someone whose behaviour deviates from the social norm (against expectations, the fellow student does not invite others, he lies, etc.). This deviation is made comprehensible by establishing a corresponding personal category in which the behaviour is ‘normal.’ Identity-relevant positioning is carried out with two category assertions: first, by using the EA construction (l. 07) and second, through the use of the ad hoc appellative (l. 16). The common acquaintance is positioned as a representative of the negatively evaluated group. This also implies a self-positioning of the speakers, distancing themselves from the acquaintance and the personal category, he is ascribed to. Categorisation makes the fellow student’s actions understandable by treating them not as inexplicable deviant ‘individual behaviour,’ but as typical for a representative of a social category.

This example elucidates two aspects in particular. First, with the EA construction locally sensitive personal categories can be established ad hoc, and semantic personal characteristics already relevant in previous contexts can be retrieved and condensed. Second, real persons (in this case a person who is not present) can be ascribed to the established category and thus positioned.

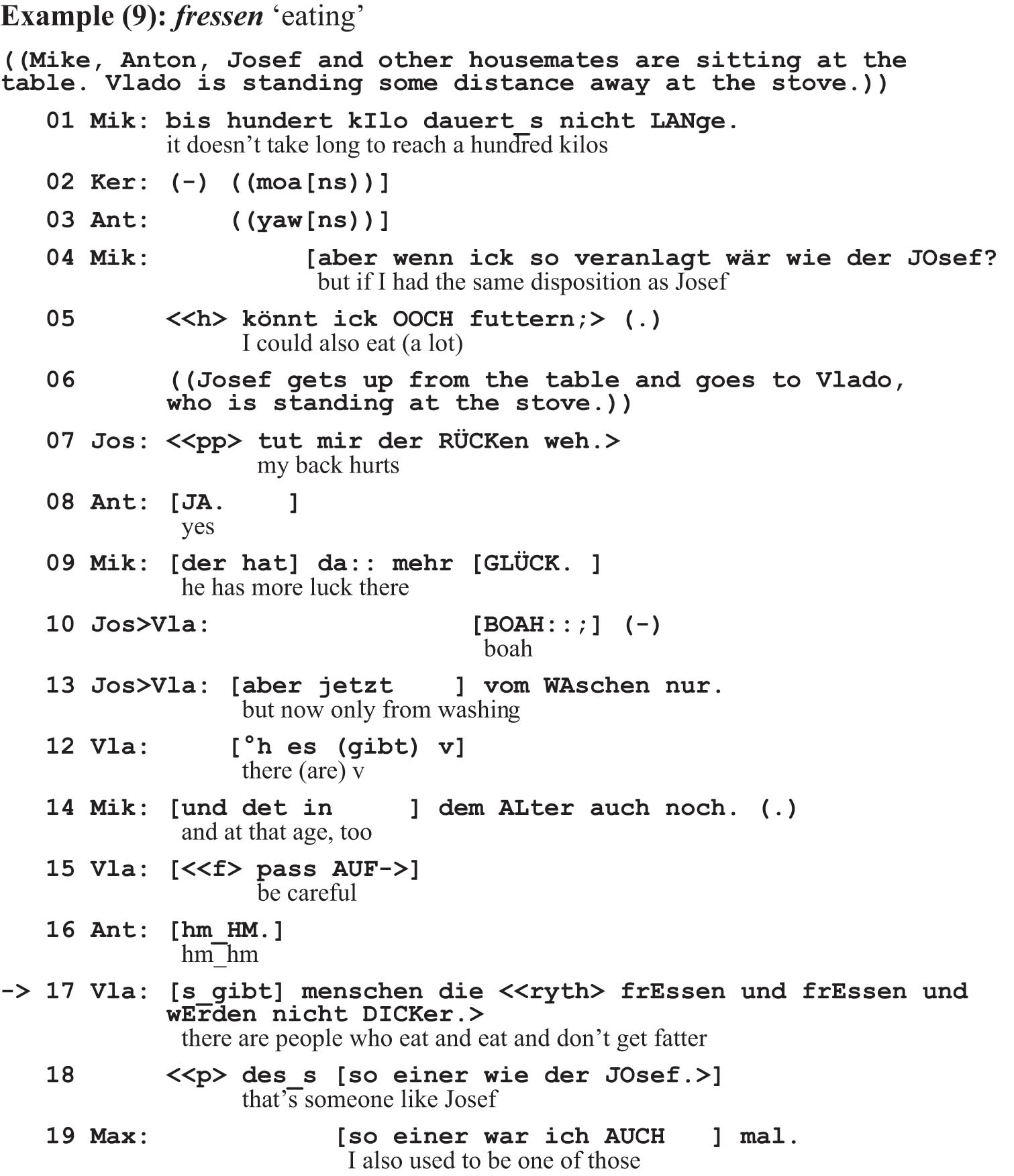

In the next example, a person who is present is ascribed to a category while others who are present are separated from it. The conversation revolves around the unfortunate (and unwanted) predisposition to gain weight quickly. Mik had just regretfully reported that he has to be disciplined about how much he eats to avoid gaining too much weight. This is where the transcript begins.

At the beginning of the sequence, Mik describes himself as someone who has to control the amount of food he eats because he gains weight very quickly (l. 01). He now compares himself to Jos, who is also present and has the opposite disposition: aber wenn ick so veranlagt wär wie der JOsef <<h> könnt ick OOCH futtern;> ‘but if I had the same disposition as Josef I could also eat (a lot)’ (l. 04-05). This assertion follows the logic that genetic predisposition determines whether eating leads to unwanted weight gain or not. Jos picks up on this by postulating a category of people die <<ryth> frEssen und frEssen und wErden nicht DICKer.> ‘who eat and eat and don’t get fatter’ (l. 17). In the next turn, he explicitly ascribes Josef to this category <<p> des_s so einer wie der JOsef.> ‘that’s someone like Josef’ (l. 18).

In this sequence, Mik’s individual juxtaposition of himself and Jos leads to a personal category that is characterised by contradicting the logic of ‘eating a lot leads to gaining weight’ and postulating the validity of the opposite, namely, ‘eating a lot does not lead to gaining weight for some people.’ This can be linked to a number of socially relevant inferences and associated evaluations, e.g. that ‘not gaining weight’ is not necessarily an indication of self-control. Conversely, this characterisation may also provide moral relief to members of the complementary personal category, who do gain weight quickly.[4]

The subsequent course of the interaction is also interesting. In l. 19, Max ascribes herself to this category: so einer war ich AUCH mal. ‘I also used to be one of those.’ Her self-positioning ratifies the ad hoc category that has been established and continues the categorisation in a self-initiated and self-referential way, albeit with the regret that it is not valid any more (category membership can thus also change over the course of time).

5.1.2 Distancing oneself or others from a category

Section 5.1.1 showed that the EA construction is used to establish an ad hoc category to which participants ascribe real persons (including themselves). In the examples discussed, this was often associated with an implicit distancing of persons. The following examples will show how the EA construction is used for the explicit distancing of an individual from a personal category.

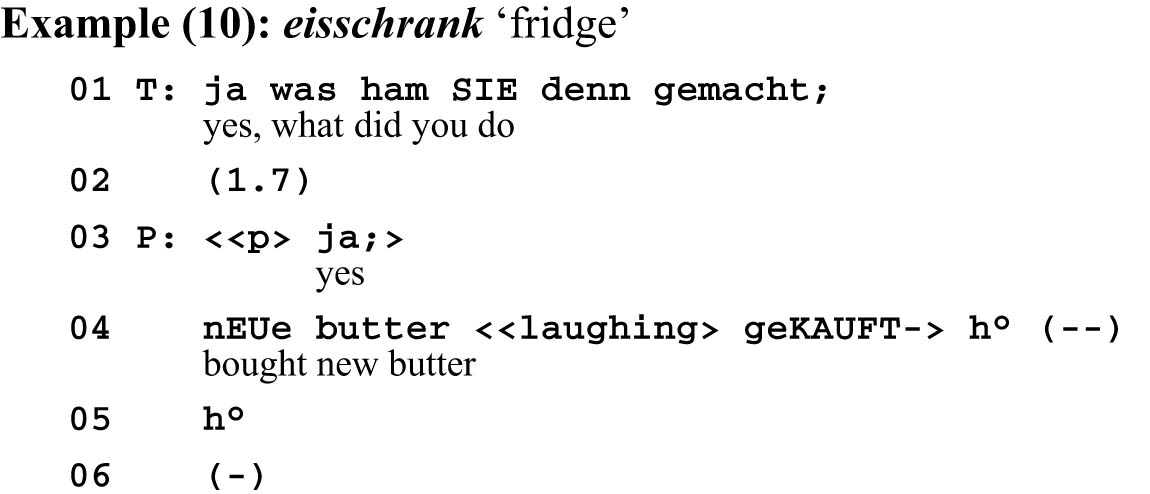

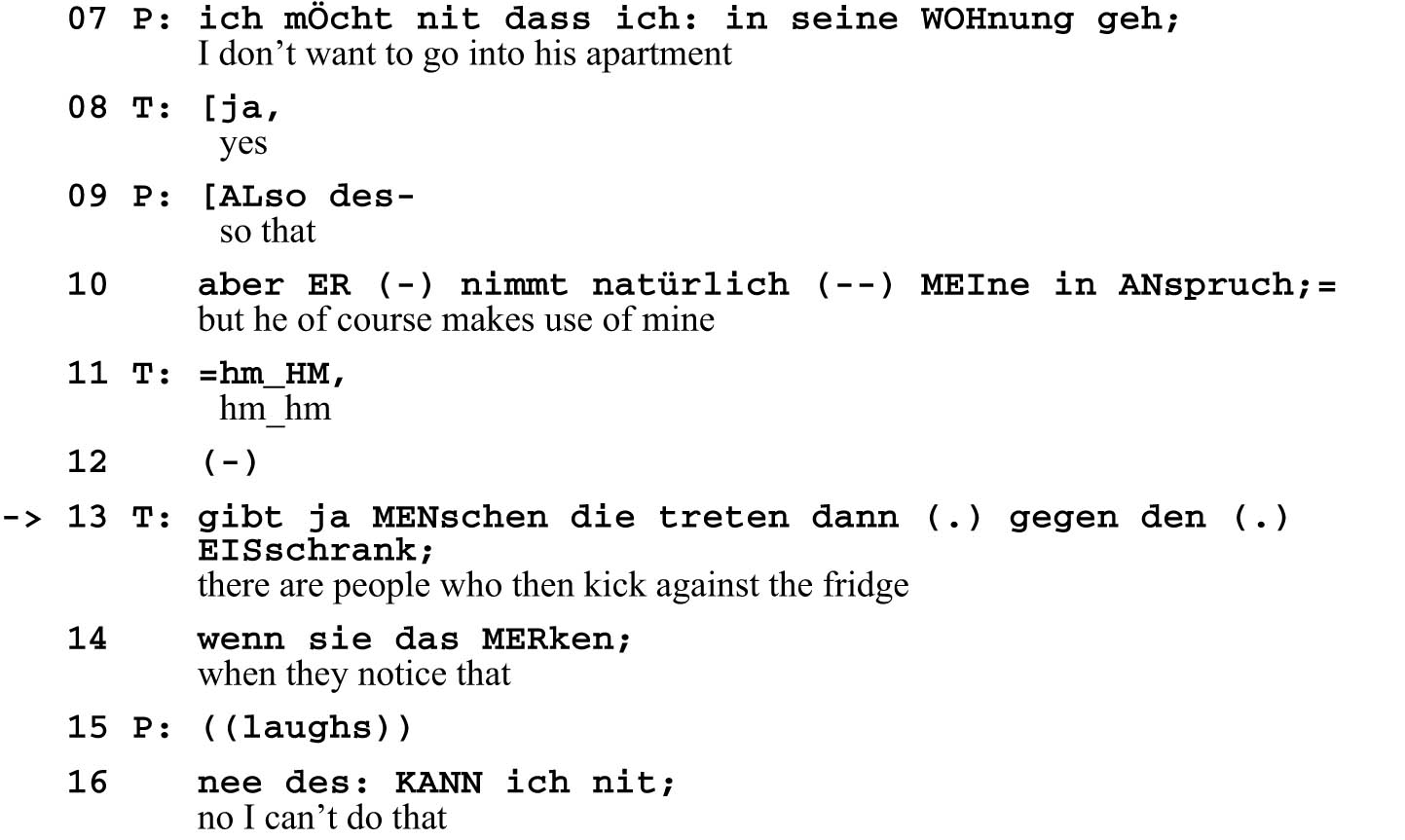

Example 10 originates from a therapy session in which patient P has just told therapist T that her son, who lives in the same house, comes into her apartment and takes the butter dish out of the fridge.

The excerpt begins with P describing her reaction (l. 03–04) in response to T’s question (l. 01), namely, that she bought new butter (and did not criticise her son’s behaviour, get annoyed, or complain). She then mentions her normative orientation, that she does not want to go into her son’s apartment in his absence (l. 7), and contrasts this with his behaviour, which does involve making use of her place. In her next statement, T focuses on P’s potential emotional reaction by asserting that some people would get very angry. She establishes a social category using the EA construction: gibt ja MENschen die treten dann (.) gegen den (.) EISschrank wenn sie das merken; ‘there are people who then kick against the fridge when they notice that’ (l. 13). On the basis of this personal category, an alternative reaction is sketched out (note the anaphoric dann ‘then’ and das ‘that,’ referring to the previous description).[5]

In contrast to the described (socially adapted but conflict-avoiding) behaviour of the patient, T suggests an affective, angry reaction as a model for P, a socially inappropriate but plausible behaviour, which he legitimises by defining it as a personal category. P explicitly distances herself from the category established by T by saying nee des: KANN ich nit; ‘No, I can’t do that’ (l. 16). She thus implicitly acknowledges the existence of the personal category, but claims that she cannot act according to categorical behaviour.

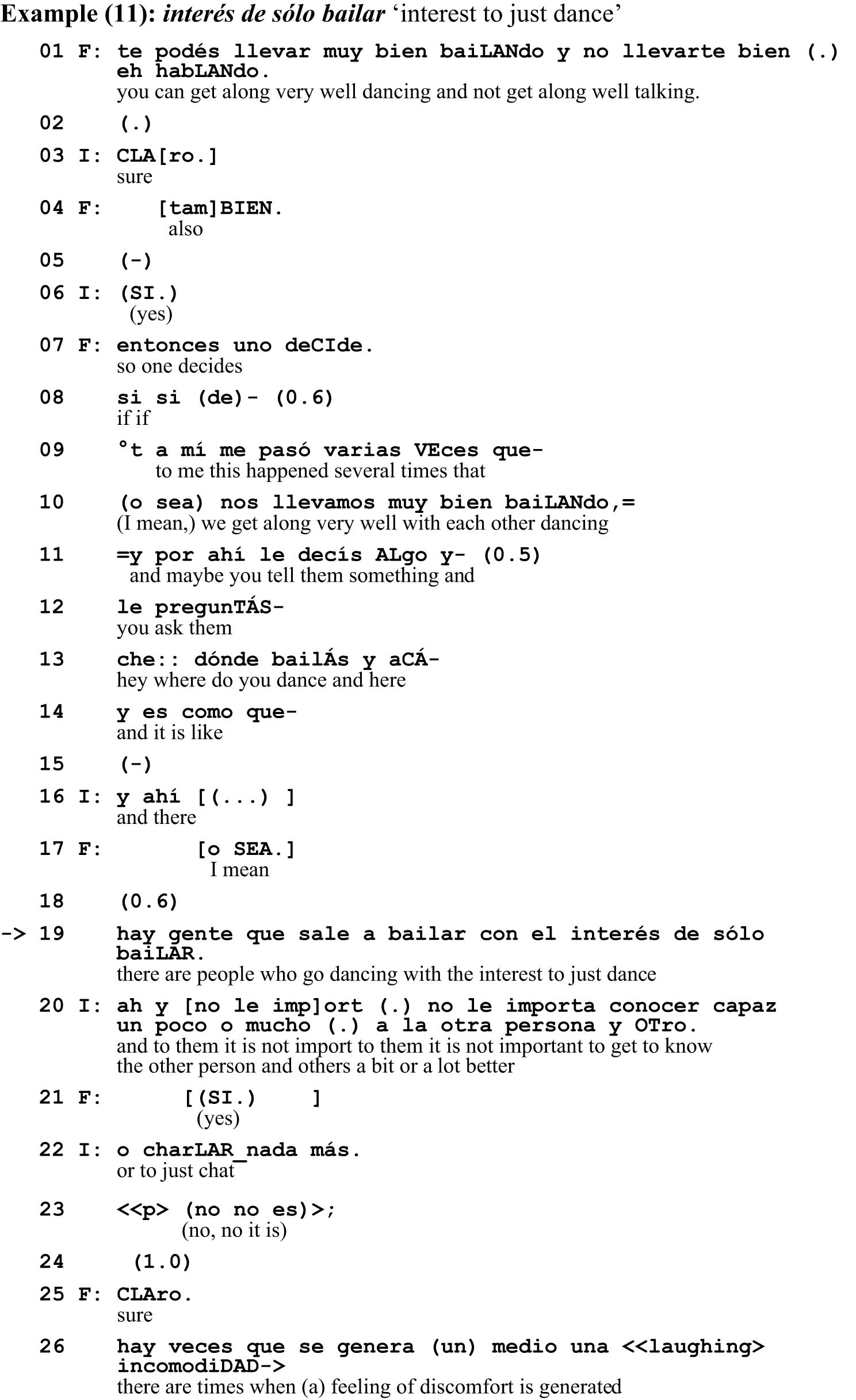

In addition to an explicit distancing from an ad hoc category, relations can also be established more subtly, or even implicitly. This is the case in the next example, which is taken from an interview with a tango dancer. At tango dance events, usually three to four pieces of music are played for dancing, followed by a short break during which there is no dancing. The topic of the interviewer’s question is what the tango dancers – who often do not know each other beforehand – do during these breaks. In his question, the interviewer mentions two candidate answers (Pomerantz 1988): that people may or may not talk to each other. This is where the example begins. F answers that this depends on whether the dancers have ‘the same wavelength,’ as it is not always the case that people who dance well together can also hold a good conversation.

The fact expressed in l. 01 that it can be difficult to have a good conversation with someone even if you dance well together, is subsequently illustrated by F through a generic scenario with animated speech (Ehmer 2011) (l. 09–14). In this scenario, he describes how asking a fairly innocuous question (che:: dónde bailÁs, ‘hey where do you dance,’ l. 13) can lead to a rupture in the situation.[6]

Now F uses the EA construction: hay gente que sale a bailar con el interés de sólo baiLAR ‘there are people who go dancing with the interest just to dance’ (l. 19). He ad hoc establishes a personal category with the constitutive feature of going to dance events exclusively to dance. The focus particle sólo (‘only/exclusively’) expresses that there are no other interests, not even having a conversation.

After using the EA construction, the interviewer signals his understanding by further characterising the ad hoc personal category just established, and now explicitly ascribes characteristics to the members of the category that were previously only implied: that these people have no interest in getting to know their dance partners or even just chatting with them (ah y [no le imp]ort (.) no le importa conocer capaz un poco o mucho (.) a la otra persona y OTro- o charLAR_nada más... ‘and to them it is not import to them it is not important to get to know the other person and others a bit or a lot better’ l. 20, 22). F ratifies this with CLAro. (l. 25) and adds that (therefore) sometimes an unpleasant atmosphere arises during dance breaks. The ad hoc category thus functions as a justification for why conversations during breaks can be difficult.

With regard to the positioning function of the EA construction, in this case no specific real person is explicitly ascribed to the ad hoc category or distanced from it. Instead, speaker F uses the construction to implicitly distance himself from the category by creating a generic scenario in which he interacts with people from this category and subsequently characterising the situation as unpleasant (l. 26). Speakers can make such implicit distancings both for themselves and for others. There can also be nuances in the degree of implicitness/explicitness, e.g. by expressing uncertainty about the categorisation.

5.2 Modifying categories

So far, we have shown that the EA construction can be used to establish categories to which persons are ascribed or from which they are distanced (Section 5.1). In this section, another function is discussed, namely that of modifying categories. More specifically, it will be shown that EA constructions can be used to establish ad hoc categories, which in turn modify categories that have been previously made relevant by the participants. This can serve to ‘re-evaluate’ a previously invoked category (Section 5.2.1) or to question its existence altogether and thus ‘dissolve’ it (Section 5.2.2).

5.2.1 Re-evaluating a category

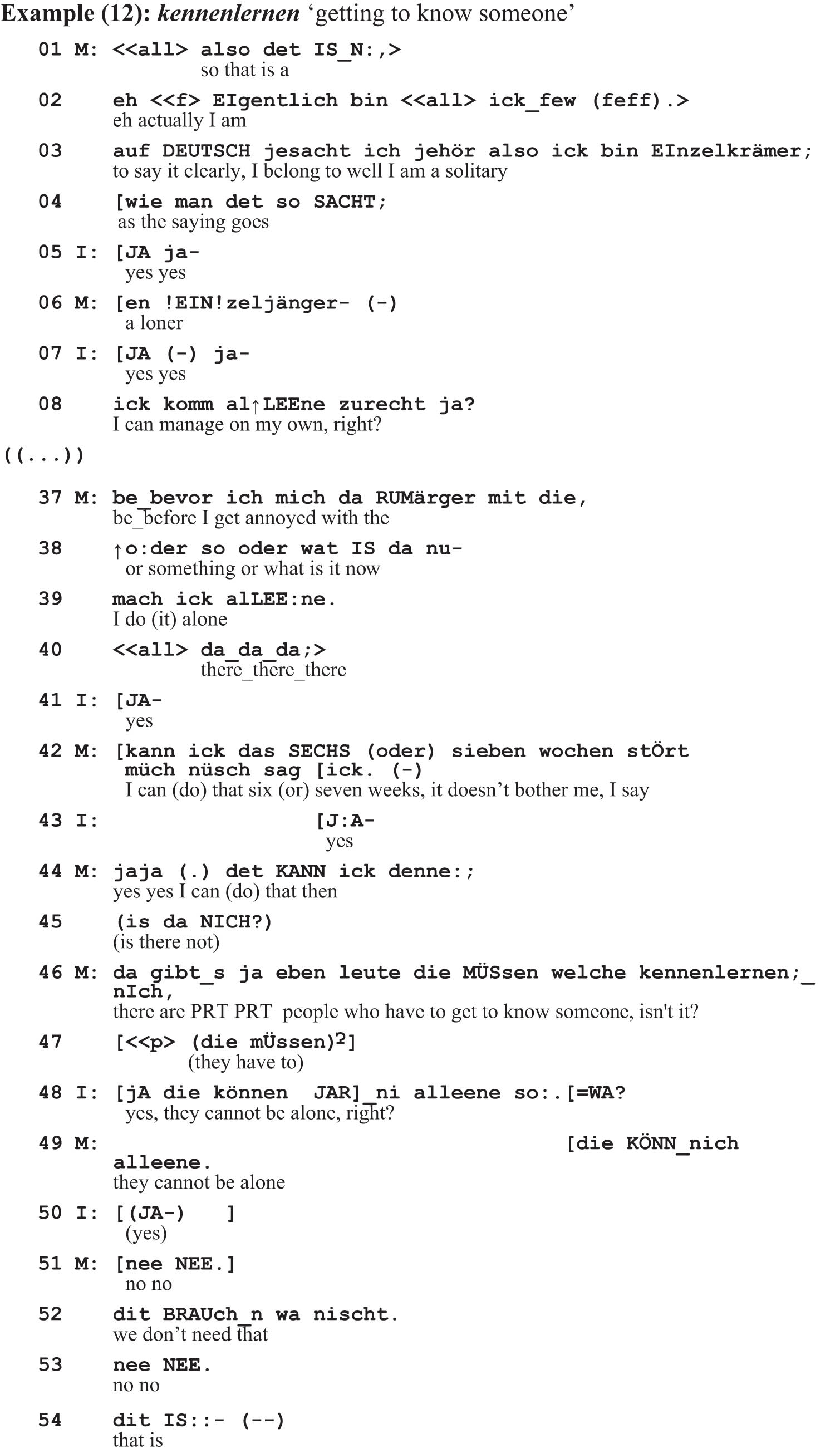

In the following example, the category Einzelkrämer ‘loner,’ which potentially has negative connotations for the participants, is invoked. The EA construction is then used to contrastively develop another category with a strong negative connotation, whereby the category ‘loner’ is reinterpreted positively.

The example was extracted from the dialect interview corpus. As part of the biographical narrative, M talks about his professional career and explains why he has never regretted becoming self-employed, despite the stress involved. The sequence begins after the interviewer has asked M whether he has any regrets about becoming self-employed and M has emphasised that he does not enjoy working with other people.

At the beginning of the sequence, M explicitly ascribes himself to the established social category ‘loner’: also ick bin EINzelkrämer, ‘well I’m a solitary’ (l. 03) and nen EINzeljänger ‘a loner’ (l. 06). Through the use of hedge expressions EIgenlich ‘actually’ (l. 02), wie man det so SACHT ‘as the saying goes’ (l. 04), multiple starts (l. 01–03) and other hesitation phenomena such as pauses, the speaker signals a clear effort at formulation. This may be motivated by the rather negative social evaluation of the established category ‘loner.’ The speaker’s understanding of the category as potentially negative is supported by the fact that he subsequently elaborates on a positive evaluation of being a loner by emphasising his autonomy: ick komm al↑LEEne zurecht ja? ‘I can manage on my own, right?’ (l. 08). He supports his claim with the example that he can go on vacation alone for several weeks without any problem (l. 10–36, omission in transcript). Several positive evaluations (e.g. stört mich NICH ‘doesn’t bother me’; l. 42) follow. In particular det KANN ick denne: ‘I can (do) that then’ (l. 44) emphasises that it is a ‘skill’ to be alone, which is indexed by accentuating the deontically used modal verb können ‘can.’

At this point, the speaker uses the EA construction and establishes a personal category that is characterised by the feature ‘having to get to know someone’: da gibt_s ja eben leute die MÜSsen welche kennenlernen; ‘there are PRT PRT people who have to get to know someone’ (l. 46). By emphasising MÜSsen ‘have to,’ he highlights the deontic aspect of this personal category having no other choice of action. This is taken up by I, who first signals agreement with jA, then takes up this attribute and reformulates the deontic aspect (‘have to get to know’) with: jA die können JAR]_ni alleene so:.[=WA? ‘yes they cannot be alone right?’ (l. 48), using the structural latency of C1. I thus documents his understanding (Deppermann 2008) by naming a concurrent feature of the category that captures the same situation from a complementary perspective: the (negated) attribute ‘being able to be alone’ is complementary to ‘having to get to know’ in the local context. The concurrent feature proposed by I is then ratified by M through repetition: [die] KÖNN nich alleene. ‘they cannot be alone’ (l. 49). Through the collaborative elaboration of the deontic aspect as an ‘inability,’ a negative evaluation of the personal category is achieved: category members are denied agency or autonomy and self-determination. By opposition to these limitations, ‘being alone’ is thus construed as a positively evaluated ability, which the speaker ascribes to himself. After the use of the EA construction and the negotiation of a positive evaluation of being a loner, I changes the subject by asking a question about contact with old friends.

In summary, the speaker first ascribes himself to the conventionally negative social category ‘loner’ and then develops a corresponding (generic) scenario (Brünner and Gülich 2002) to positively re-evaluate this category. For this purpose, he uses the EA construction to ad hoc establish a negatively evaluated personal category, from which he distances himself. This use of the EA construction thus shows a clear parallel to the positioning activities through distancing from a category described in Section 5.1.2. However, the use of the construction presented here clearly goes beyond mere distancing, as the negatively evaluated ad hoc category simultaneously establishes a positive (re)evaluation of the conventionalised category (‘loner’) to which the speaker had already assigned himself earlier in the conversation. Distancing from one category therefore also means ensuring the desired evaluation of the category used for positioning.

Again, the category is developed in a locally sensitive way, by starting from a previously relevant aspect of social behaviour and then setting the ad hoc category apart (being able to be alone vs having to get to know someone). Here the EA construction also appears as a resource for dealing with an already pre-established social category (the ‘loner’). This example further illustrates that personal categories are negotiated and processed collaboratively, e.g. by I’s uptake and reformulation of a characteristic introduced by M.

5.2.2 Dissolving a category

In addition to ‘re-evaluating’ a personal category that is relevant in the context of the conversation, the EA construction can also be used for ‘dissolving’ a category. This function is particularly useful when a category of person is presupposed in the conversation that is not accepted by any of the participants present. The EA construction is then used to assert the existence of other personal categories that contradict and thereby ‘deconstruct’ the presupposed category.

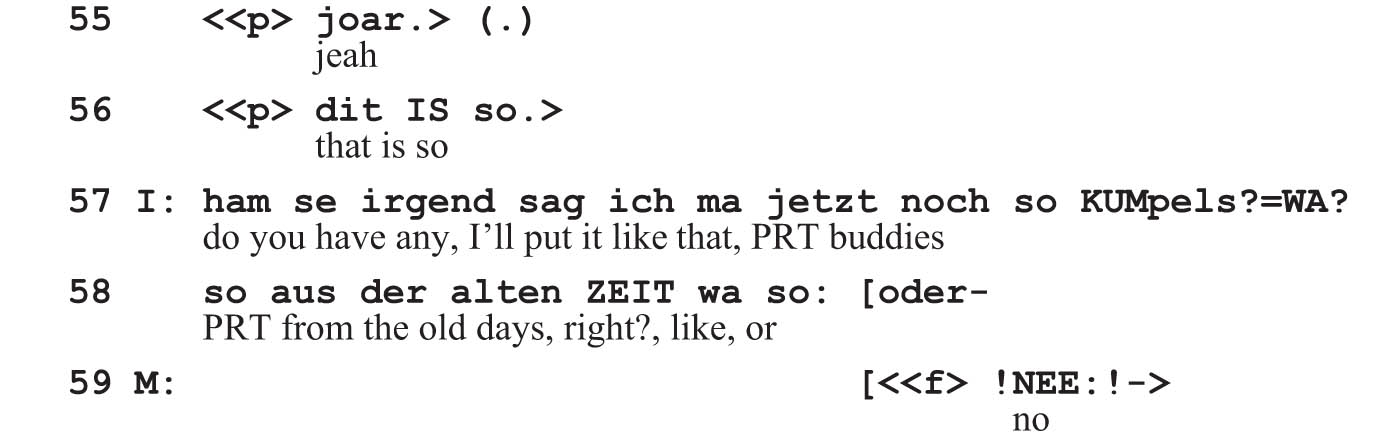

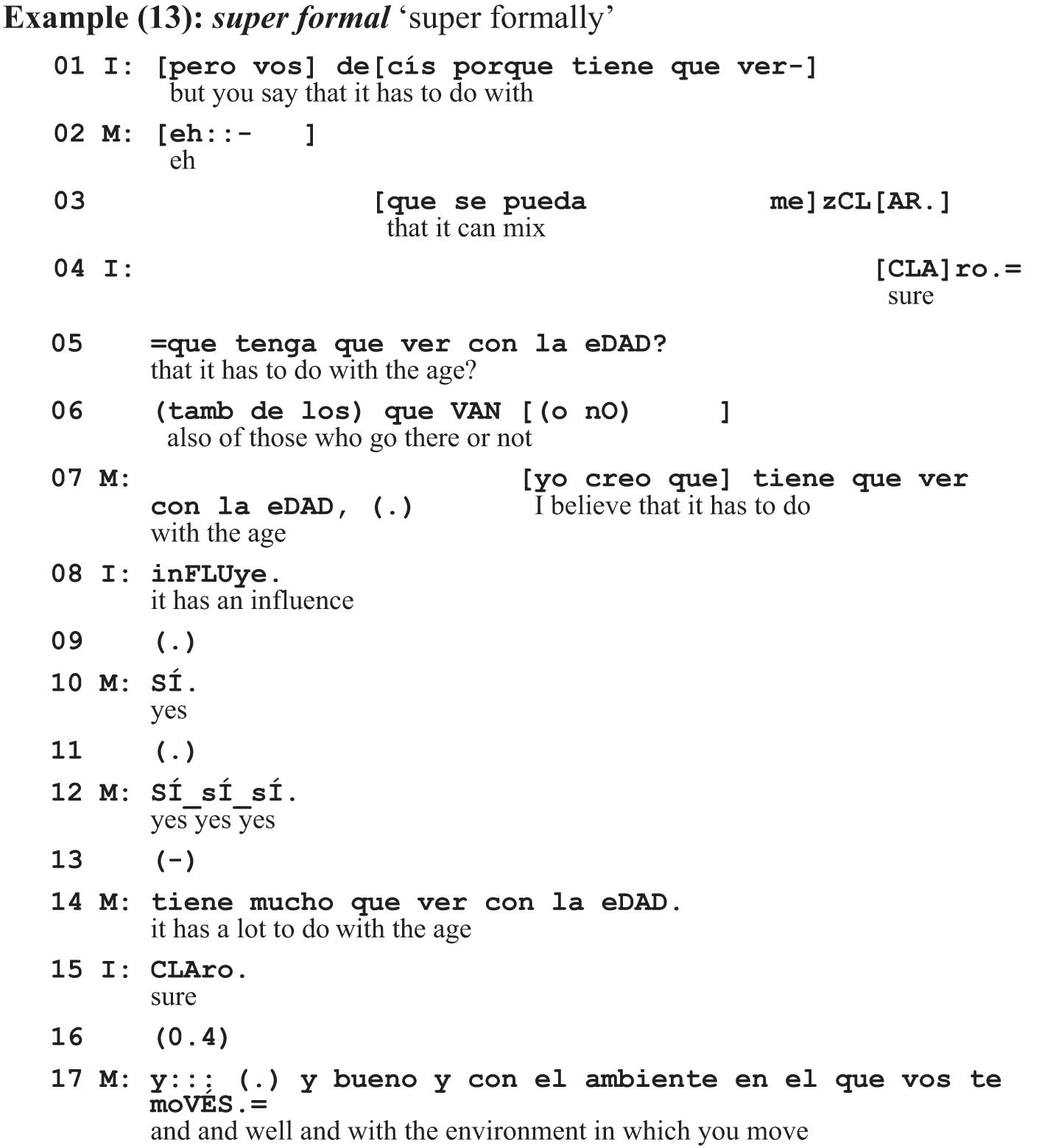

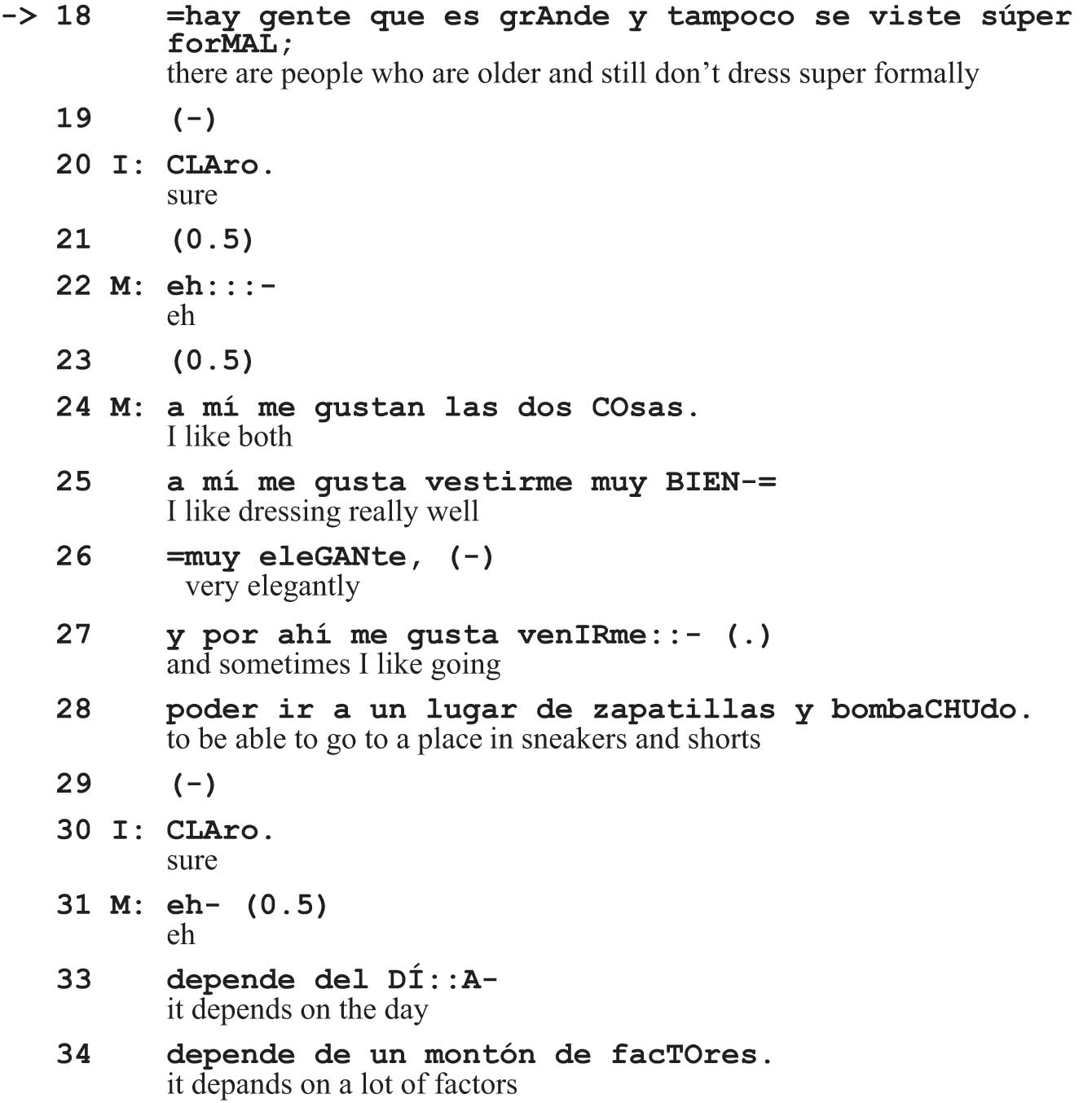

In the following example, a speaker uses the EA construction to deconstruct the locally presupposed personal category ‘tango dancers who dress formally are older people.’ The speaker objects to the assumed category-constitutive connection between dressing formally – something that the speaker herself does – and being of a certain age.

This example comes from an interview. The interviewer asks a tango dancer whether there is a specific dress code for tango dance events (in Spanish, milongas). The dancer explains that people generally dress elegantly, but that this depends on the venue and the type of event. She then gives the example of her own dance event, where the organisers – including the speaker – decided to dress very formally: the men in shirts, jackets, and ties, and the female dancers in the same colour as their dance partners’ shirts. She contrasts this example with a venue where participants dress very informally and also very variedly.

In her description, the speaker adds that the target group of each event is also different, and that visitors at the second venue are younger or ‘lighter’: es gente más JO:ven- gente mucho más LIGHT; (‘it’s younger people, people much more light,’ not in the transcript). The interviewer now asks whether the way of dressing depends on age.

F initially confirms the interviewer’s question (l. 01, 05-06) as to whether there is a connection between age and the way one dresses (l. 07, 10, 12), and explicitly states that age has a major influence (l. 14). Thus, up to this point in the conversation it can be assumed – especially from the interviewer’s question – that there is a direct connection between age and the way one dresses. This combination of two characteristics suggests the existence of two personal categories in the conversation: ‘younger people who dress casually’ and ‘older people who dress formally.’ After her initial confirmation, however, F mentions ‘the environment in which you move’ as a further influencing factor (l. 17).

By using the EA construction, the speaker now relativises the connection between how one dresses and age. She establishes an ad hoc personal category that does not correspond to either of the two previously assumed categories by linking the contextually relevant characteristics in a concessive manner:=hay gente que es grAnde y tampoco se viste súper forMAL; (‘there are people who are older and still don’t dress super formally,’ l. 18). The concessive connection between the characteristics is explicitly signalled by tampoco (here to be translated as: ‘still’).

The ad hoc creation of a personal category thus deconstructs another category that is assumed or presupposed in the context and for which a certain combination of social characteristics is constitutive. This deconstruction of a (presupposed or potential) social category serves to prevent the speaker from being ascribed to such a category, as it becomes clear in the later course of the conversation. After using the EA construction, the speaker emphasises that she herself likes to dress elegantly as well as casually (l. 24–28), which entails that she cannot be ascribed to any of the personal categories mentioned before. Deconstructing the initial categories further protects F from the implicit attribution of ‘being older.’ The ‘danger’ of such an attribution exists, in particular because she dresses very formally at her own event.

In summary, the use of the EA construction can prevent a possible personal category from becoming part of the participant s common ground. The starting point here is the combination of several social characteristics into one personal category. With the EA construction, at least one, but usually several personal categories are then established ad hoc, in which the locally relevant characteristics are combined in a way that deviates from the initial combination. In most cases, this involves a concessive combination of the characteristics previously determined to be relevant.[7]

The deconstruction of ‘possible’ or presupposed personal categories can be relevant to the speakers’ positioning in various ways. For example, it was just seen that speakers can prevent a potentially category-constitutive characteristic (e.g. older age) from being attributed to them on the basis of another characteristic (e.g. style of dress). In addition, a speaker can counteract an undesired, external positioning by deconstructing the unwanted category. In addition, the differentiating development of personal categories allows the speaker to show that they are not starting from overly simple social categories and contexts, but have a differentiated view of the world.

With regard to the local development of the personal category (or categories), the example just analysed also shows how the development of the categories takes place sequentially. Starting from a potential category, which in the local context is associated with a negative evaluation (and an undesirable external positioning of a participant), the existence of other categories is postulated by a recombination previously named (potentially category-constitutive) characteristics. The ad hoc establishment of social categories is thus embedded in sequential processes and emerges from these.

At the same time, the above example makes it clear that positioning is not exclusively tied to the use of the EA construction. Rather, complex positioning activities take place, and the construction serves as a resource amidst these activities. The construction is used at specific points, typically towards the end of such positioning activities. It is associated with the potential to create a sensible or meaningful condensation of features from the social environment. These condensations are then often responded to in a collaborative manner (e.g. through co-constructions) by interlocutors. The use of the construction in the interaction thus also serves as a resource that affords participants a starting point for reassurance about a shared assessment of the lifeworld. This reassurance is a way for the participants to document understanding (Deppermann and Schmitt 2008).

6 Summarising discussion: EA constructions and positioning

Social identity is a central area of investigation in conversation research. Its specific approach lies, among other things, in understanding identity not as a stable, supra-situationally valid phenomenon that is firmly bound to an individual but as a joint achievement of the interactants in which identity parameters are made relevant dynamically and context-sensitively. These parameters are both claimed and ascribed, as well as collaboratively negotiated. Positioning theory, in combination with membership categorisation analysis, provides a productive frame of reference for the analysis of identity as a collaborative achievement. So far, however, this has mainly been applied to narratives (see for example the special issue of Narrative Inquiry 23:1, Deppermann 2013a). This article takes a different approach and focuses on a particular grammatical construction, the EA construction, as a linguistic resource for negotiating identity in interaction (Günthner and Bücker 2009, Birkner 2006).

The EA construction is analysed as a bipartite structure. While C1 asserts the existence of a category, the essential characteristics of the category are specified in C2, which is connected to C1 via a relative connector (Spanish que/German die) or, in German, a demonstrative pronoun (die). The lexical realisation of C1 is relatively fixed, with the verbs Hay/Es gibt and preference for a few, unspecific human mass nouns (typically gente/personas/tipos or Leute/Menschen/Typen ‘people/humans/types’). In contrast, the realisation of C2, where the category-constitutive features are established, is much more varied, and the examples differ regarding the semantic complexity of the category. C2 can contain a single feature, several features – which can be semantically linked in different ways – and complex scenes or character animations to semantically specify the category. Furthermore, category-constitutive features do not have to be explicitly formulated within C2 but may also be integrated from the preceding context, e.g. through anaphoric reference. It is crucial to emphasise that this construction is employed for the development of categories that are yet to be conventionalised through categorial designation. In other words, these categories are formed (more or less) ad hoc.

In the following, the results of the analysis are summarised with regard to how the construction is used for (1) establishing categories and (2) positioning in interaction.

6.1 Establishing categories with the EA construction

The analyses have shown that participants do not use the EA construction to activate pre-established, conventionalised personal categories, but instead allow ad-hoc categories to emerge for local purposes within the conversation. The characteristics that are constitutive of a category are spontaneously ascribed, jointly developed, and negotiated by the participants during the course of talk-in-interaction. It is customary for the construction to incorporate features that have previously been attributed to one or more persons in the preceding discourse in concrete situations. This becomes particularly clear in examples in which C2 consists merely of an anaphoric reference to previously named characteristics without any further specification (e.g. example 6: pero hay gEnte que SÍ. ‘but there are people who yes/do’). The category-constituting features formulated in C2 are thus developed ‘locally’ and in a context-sensitive manner. In the sequential process, the use of the EA construction condenses individual characteristics into a personal category that is claimed to be valid beyond the individual case.

Establishing personal categories is closely linked to collaborative development and/or negotiation. This ranges from minimally explicit ratification to a joint ascription of characteristics and their confirmation and evaluation. The construction cannot open a conversational sequence, since the condensation of features into a category necessarily presupposes previous negotiation. Instead, the use of the construction can mark the conclusion of a topic (e.g. example 8, mitómanos sociales), provide an evaluation of a narrative, summarise arguments, justify actions (one’s own or others), or give reasons for evaluations. Its main role is sometimes stressed by means of a particular rhetorical design; this can be seen in the rhythmisation of example 9 fressen and the animated speech of example 1 ganar. This stylisation often combines with the use of commonplaces, which results in a kind of sentential character. The complexity of reality is summarised in a ‘simple and instantly plausible’ form that can be exploited further for argumentative and interpretative purposes. This summarising process, which aims to reach agreement on shared assessments, makes it possible to document understanding.

6.2 Positioning with the EA construction

The interactive work on category development with the EA construction described above is inherently relevant to establishing identity and closely linked to social self- and other-positioning. Generally speaking, the function of the EA construction is to organise the world into social categories in order to represent it, systematise it, explain it, and make it understandable. These social categories are not conceived as static; they are created in context according to local needs, and they are dynamic, negotiable, and changeable. Through categorisation, the concrete is abstracted, for example by linking an individual case to a category. This has the effect of condensing or abstracting individuals introduced in conversation into categories with a supra-individual or broader scope.

In addition to the general function of negotiating person categories, two more specific uses of the EA construction that are relevant for positioning were analysed. These were defined as ‘relating’ and ‘modifying.’ Relating primarily involves ‘ascribing to’ or ‘distancing from’ a category, i.e. the participants establish a relation between themselves or others and a category (Section 5.1). Not surprisingly, assigning oneself to a category tends to be associated with a positive evaluation of the category. Distancing oneself is often associated with negatively evaluated personal categories; in these cases, reference to the personal category has the function of contrasting one’s (positive) self-image with a clearly negatively evaluated image of others (the ad-hoc negative category).[8] Modifying consists of changing, re-evaluating or dissolving categories (Section 5.2). The relevance of positioning here is that a (possible) ascription to a category is prevented, or at least the evaluation of the category is changed. Both relating and modifying show different degrees of explicitness in the ascription to, distancing from, and evaluating the categories. Moreover, self-positioning interacts with other-positioning in complex ways. In our data, other-positioning activates self-distancing more than self-positioning activates other-positioning.

Of course, it is not being suggested that the identified contextual functions can only be realised using the EA construction; presumably, they can also be accomplished through other linguistic means. However, the construction clearly lends itself to the realisation of these conversational functions. In particular, while the EA construction is not the only way to position someone in a conversation, it is often found at ‘key points’ of positioning activities and it plays an important role in condensing information. By postulating, evaluating or negotiating social norms (Sacks 1984 on ‘doing being ordinary’), it can be understood as a practice of normalisation (Groß and Birkner 2024).

7 Conclusion

Positioning and the creation of social identity are complex, context-sensitive, argumentative activities that are negotiated in everyday conversations as part of moral communication. This dynamic negotiation process serves to develop patterns of orientation, jointly structuring, explaining and evaluating the local lifeworld, and thus creating social reality. Routinised ways of acting make this process easier for those involved, and grammatical constructions – understood as sedimented action formats – are a key resource for social action.

The findings presented in this study are relevant in two respects. From an ethnomethodological point of view, prior analyses had mainly focused on established and basic membership categories, which are assumed to be shared as common ground. This article broadens the scope of the research to ad-hoc category formation. It demonstrates (1) the processes by which categories are constituted locally, negotiated collaboratively, and reassured, modified or, in cases of disagreement, dissolved; (2) the linguistic structure of EA constructions and how participants utilise it in interaction. Syntactic formats such as the EA construction act as linguistic reference points and serve as frames to enable collaborative negotiation.

In construction grammar, pragmatic aspects have often been rather neglected. In contrast, the present analysis shows that constructions are a central resource for social negotiation processes. It also shows that there is no one-to-one relationship between form and function; the same combination of formal features can be used to achieve different positioning functions. In addition to the positioning constructions discussed here, there are others in the languages studied. These also involve particular formal and functional profiles. A comprehensive modelling of a network of constructions that includes decidedly interactional-functional references could be a very profitable endeavour for construction grammar and its holistic claim.

Transcription conventions

Sequences are transcribed using the GAT 2 conventions for German (Selting et al. 2009) and Spanish (Ehmer et al. 2019).

- [ ]

-

overlap and simultaneous talk

- =

-

latching

- (.)

-

micropause (shorter than 0.2 s)

- (2.0)/(2.3)

-

measured pause

- y_eh

-

assimilation of words

- :, ::, :::

-

segmental lengthening, according to duration

- ((laughs))

-

non-verbal vocal actions and events

- SÍlaba

-

focal accent

- sÍlaba

-

secondary stress

- ?

-

pitch rising to high at end of intonation phrase

- ,

-

pitch rising to mid

- -

-

level pitch

- ;

-

pitch falling to mid

- .

-

pitch falling to low

- <<p> >

-

piano, soft

- <<f> >

-

forte, loud

- <<h> >

-

high pitch register

- <<p> >

-

piano, soft

- <<all> >

-

allegro, fast

- °h, °hh, °hhh

-

inbreath, according to duration

- h°, hh°, hhh°

-

outbreath, according to duration

- <<creaky> >

-

commentaries regarding voice qualities with indication of scope

- (creo/pero)

-

assumed wording, with possible alternatives

- PRT

-

particle (German)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on the article.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Both authors have accepted the responsibility for the content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Both authors are equally responsible for all sections.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Antaki, Charles and Sue Widdicombe. 1998. “Identity as an Achievement and as a Tool.” In Identities in Talk, edited by Charles Antaki and Sue Widdicombe, 1–14. London: Sage.10.4135/9781446216958.n1Search in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter. 2015. “The Temporality of Language in Interaction: Projection and Latency.” In Temporality in Interaction, edited by Arnulf Deppermann and Susanne Günthner, 27–56. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/slsi.27.01aueSearch in Google Scholar

Bamberg, Michael. 1997. “Positioning between Structure and Performance.” Journal of Narrative and Life History 7 (1–4): 335–42.10.1075/jnlh.7.1-4.42posSearch in Google Scholar

Bamberg, Michael. 2008. “Twice-told Tales: Small Story Analysis and the Process of Identity Formation.” In Meaning in Action, edited by Toshio Sugiman, Kenneth J. Gergen, Wolfgang Wagner and Yoko Yamada, 183–204. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-4-431-74680-5_11Search in Google Scholar

Bamberg, Michael and Alexandra Georgakopoulou. 2008. “Small Stories as a New Perspective in Narrative and Identity Analysis.” Text & Talk 28 (3): 377–96.10.1515/TEXT.2008.018Search in Google Scholar

Berger, Peter L. and Thomas Luckmann. 1980. Die gesellschaftliche Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit: eine Theorie der Wissenssoziologie. Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.Search in Google Scholar

Birkner, Karin. 2001. Bewerbungsgespräche mit Ost- und Westdeutschen. Eine kommunikative Gattung in Zeiten gesellschaftlichen Wandels. Linguistische Arbeiten. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783110915129Search in Google Scholar

Birkner, Karin. 2006. “(Relativ-)Konstruktionen zur Personenattribuierung: ‚ich bin n=mensch der...’.” In Konstruktionen in der Interaktion, edited by Susanne Günthner and Wolfgang Imo, 205–38. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110894158.205Search in Google Scholar

Birkner, Karin and Christina Burbaum. 2013. “Suchbewegungen im Therapiegespräch. Formen der interaktiven Bearbeitung von Kausalattributionen bei körperlichen Beschwerden ohne Organbefund.” InList: Interaction and Linguistic Studies 53: 1–56.Search in Google Scholar

Birkner, Karin and Oliver Ehmer. 2014. “Existenz-Attributiv-Konstruktion(en) im Deutschen und Spanischen. Strukturlatenz und Repetition.” In Sprache im Gebrauch: räumlich, zeitlich, interaktional. Festschrift für Peter Auer, edited by Pia Bergmann, Peter Gilles, Helmut Spiekermann, and Tobias Streck, 275–96. Heidelberg: Winter.Search in Google Scholar

Brünner, Gisela and Elisabeth Gülich. 2002. “Verfahren der Veranschaulichung in der Experten-Laien-Kommunikation.” In Krankheit verstehen. Interdisziplinäre Beiträge zur Sprache in Krankheitsdarstellungen, edited by Gisela Brünner and Elisabeth Gülich, 17–93. Bielefeld: Aisthesis.Search in Google Scholar

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth and Margret Selting. 2018. Interactional Linguistics. Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781139507318Search in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf. 2006. “Construction Grammar – Eine Grammatik für die Interaktion?” In Grammatik und Interaktion. Untersuchungen zum Zusammenhang von grammatischen Strukturen und Gesprächsprozessen, edited by Arnulf Deppermann, Reinhard Fiehler, and Thomas Spranz-Fogasy, 43–65. Radolfzell: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.Search in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf. 2008. “Verstehen im Gespräch.” In Sprache – Kognition – Kultur. Sprache zwischen mentaler Struktur und kultureller Prägung, edited by Heidrun Kämper and Ludwig M. Eichinger, 225–61. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110970555-012Search in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf. 2013a. “Editorial. Positioning in Narrative Interaction.” Narrative Inquiry 23 (1): 1–15.10.1075/ni.23.1.01depSearch in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf. 2013b. “How to Get a Grip on Identities-in-Interaction: (What) Does ‘Positioning’ Offer more than ‘Membership Categorization’? Evidence from a Mock Story.” Narrative Inquiry 23 (1): 62–88.10.1075/ni.23.1.04depSearch in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf and Reinhold Schmitt. 2008. “Verstehensdokumentationen: Zur Phänomenologie von Verstehen in der Interaktion.” Deutsche Sprache 3 (8): 220–45.10.37307/j.1868-775X.2008.03.03Search in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 2019. The Grammar Network. How Linguistic Structure Is Shaped by Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108671040Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver. 2008. cespla – Corpus de Conversaciones ESpontáneas PLAtenses. http://www.cespla.de.Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver. 2011. Imagination und Animation. Die Herstellung mentaler Räume durch animierte Rede. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110237801Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver. 2022. Makrokonstruktionen. Komplexe Adverbialstrukturen zwischen lokaler Emergenz und Sedimentierung im gesprochenen Französisch. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110666205Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver. 2023a. “act: Aligned Corpus Toolkit.” R package version 1.3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=act.Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver. 2023b. “Arbeiten mit zeitalignierten multimodalen Korpora in R. Vorstellung des Aligned Corpus Toolkit (act).” Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion (www.gespraechsforschung-ozs.de) 24: 67–126.Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver and Camille Martinez. 2014. “Creating a Multimodal Corpus of Spoken World French.” In Best Practices for Spoken Corpora in Linguistic Research, edited by Şükriye Ruhi, Michael Haugh, Thomas Schmidt, and Kai Wörner, 142–61. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Ehmer, Oliver, Luis Ignacio Satti, Angelita Martínez, and Stefan Pfänder. 2019. “Un sistema para transcribir el habla en la interacción: GAT 2.” Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 20: 64–114.Search in Google Scholar

Fischer, Kerstin. 2006. “Konstruktionsgrammatik und Interaktion.” In Konstruktionsgrammatik. Von der Anwendung zur Theorie, edited by Kerstin Fischer and Anatol Stefanowitsch, 133–50. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.Search in Google Scholar

Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. 2006. “Thinking Big with Small Stories in Narrative and Identity Analysis.” Special Issue of Narrative Inquiry 16 (1): 129–37.10.1075/ni.16.1.16geoSearch in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions. A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Groß, Alexandra and Karin Birkner. 2024. “Formen der sprachlich-interaktiven Bezugnahme auf NORMAL und ihre Funktionen in psychosomatischen Therapiegesprächen und neurologischen Telekonsultationen.” In Die kommunikative Konstruktion von Normalitäten in der Medizin: Gesprächsanalytische Perspektiven, edited by Nathalie Bauer, Susanne Günthner, and Juliane Schopf, 23–47. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110761559-002Search in Google Scholar

Günthner, Susanne and Jörg Bücker, eds. 2009. Grammatik im Gespräch. Konstruktionen der Selbst- und Fremdpositionierung. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110213638Search in Google Scholar

Günthner, Susanne and Wolfgang Imo, eds. 2006. Konstruktionen in der Interaktion. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110894158Search in Google Scholar

Haiman, John and Sandra A. Thompson, eds. 1988. Clause Combining in Grammar and Discourse. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.18Search in Google Scholar

Hausendorf, Heiko. 2000a. Zugehörigkeit durch Sprache. Eine linguistische Studie am Beispiel der deutschen Wiedervereinigung. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783110920024Search in Google Scholar

Hausendorf, Heiko. 2000b. “Zuordnen, Zuschreiben und Bewerten: Die Konstruktion kollektiver Identität in Alltagsgesprächen.” In Narrative Konstruktion nationaler Identität, edited by Eva Reichmann, 343–61. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, Thomas and Graeme Trousdale. 2013. The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195396683.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lambrecht, Knud. 1988. “Presentational Cleft Constructions in Spoken French.” In Clause Combining in Grammar and Discourse, edited by John Haiman and Sandra A. Thompson, 135–79. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.18.08lamSearch in Google Scholar

Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Information Structure and Sentence form. Topic, Focus, and the Mental Representations of Discourse Referents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620607Search in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 2008. Cognitive grammar. A basic introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195331967.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 2009. “Cognitive (construction) grammar.” Cognitive Linguistics 20 (1): 167–76.10.1515/COGL.2009.010Search in Google Scholar

Lucius-Hoene, Gabriele and Arnulf Deppermann. 2004. “Narrative Identität und Positionierung.” Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 2005 (5): 166–83.Search in Google Scholar

Östman, Jan-Ola and Mirjam Fried. 2004. “Historical and intellectual background of Construction Grammar.” In Construction Grammar in a Cross-Language Perspective, edited by Mirjam Fried and Jan-Ola Östman, 1–10. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cal.2.01ostSearch in Google Scholar

Pomerantz, Anita M. 1988. “Offering a Candidate Answer. An Information Seeking Strategy.” Communication Monographs 55 (4): 360–73.10.1080/03637758809376177Search in Google Scholar

Raible, Wolfgang. 1998. “Alterität und Identität.” Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik (LiLi) 28: 7–22.10.1007/BF03379114Search in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey. 1972. On the analyzability of stories by children. Directions in sociolinguistics. The ethnography of speaking, edited by J. Gumperz and D. Hymes, 325–45. New York.Search in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey. 1979. Hotrodder: a revolutionary category. Everyday language: studies in ethnomethodology, edited by G. Psathas, 7–14. New York, Irvington.Search in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey. 1984. “On doing ‘being ordinary’.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Maxwell Atkinson and John Heritage, 413–29. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511665868.024Search in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey. 1995. “Lecture Six: The MIR Membership Categorization Device.” In Lectures on Conversation, Volume I, Part I, edited by Gail Jefferson and Emmanuel A. Schegloff, 40–8. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Selting, Margret, Peter Auer, Dagmar Barth-Weingarten, Jörg Bergmann, Pia Bergmann, Karin Birkner, Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen, Arnulf Deppermann, Peter Gilles, Susanne Günthner, Martin Hartung, Friederike Kern, Christine Mertzlufft, Christian Meyer, Miriam Morek, Frank Oberzaucher, Jörg Peters, Uta Quasthoff, Wilfried Schütte, Anja Stukenbrock, and Susanne Uhmann. 2009. “Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2).” Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 10: 353–402.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, Ricarda. 1999. “Soziale Positionierung im Gespräch.” Deutsche Sprache 1/1999: 69–94.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- No three productions alike: Lexical variability, situated dynamics, and path dependence in task-based corpora

- Individual differences in event experiences and psychosocial factors as drivers for perceived linguistic change following occupational major life events

- Is GIVE reliable for genealogical relatedness? A case study of extricable etyma of GIVE in Huī Chinese

- Borrowing or code-switching? Single-word English prepositions in Hong Kong Cantonese

- Stress and epenthesis in a Jordanian Arabic dialect: Opacity and Harmonic Serialism

- Can reading habits affect metaphor evaluation? Exploring key relations

- Acoustic properties of fricatives /s/ and /∫/ produced by speakers with apraxia of speech: Preliminary findings from Arabic

- Translation strategies for Arabic stylistic shifts of personal pronouns in Indonesian translation of the Quran

- Colour terms and bilingualism: An experimental study of Russian and Tatar

- Argumentation in recommender dialogue agents (ARDA): An unexpected journey from Pragmatics to conversational agents

- Toward a comprehensive framework for tonal analysis: Yangru tone in Southern Min

- Variation in the formant of ethno-regional varieties in Nigerian English vowels

- Cognitive effects of grammatical gender in L2 acquisition of Spanish: Replicability and reliability of object categorization

- Interaction of the differential object marker pam with other prominence hierarchies in syntax in German Sign Language (DGS)

- Modality in the Albanian language: A corpus-based analysis of administrative discourse

- Theory of ecology of pressures as a tool for classifying language shift in bilingual communities

- BSL signers combine different semiotic strategies to negate clauses

- Embodiment in colloquial Arabic proverbs: A cognitive linguistic perspective

- Voice quality has robust visual associations in English and Japanese speakers

- The cartographic syntax of Lai in Mandarin Chinese

- Rhetorical questions and epistemic stance in an Italian Facebook corpus during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Sentence compression using constituency analysis of sentence structure

- There are people who … existential-attributive constructions and positioning in Spoken Spanish and German

- The prosodic marking of discourse functions: German genau ‘exactly’ between confirming propositions and resuming actions

- Semantic features of case markings in Old English: a comparative analysis with Russian

- The influence of grammatical gender on cognition: the case of German and Farsi

- Phonotactic constraints and learnability: analyzing Dagaare vowel harmony with tier-based strictly local (TSL) grammar

- Translating the Quranic word ‘Al-ðann’ into English

- Special Issue: Request for confirmation sequences across ten languages, edited by Martin Pfeiffer & Katharina König - Part II

- Request for confirmation sequences in Castilian Spanish

- A coding scheme for request for confirmation sequences across languages

- Special Issue: Classifier Handshape Choice in Sign Languages of the World, coordinated by Vadim Kimmelman, Carl Börstell, Pia Simper-Allen, & Giorgia Zorzi

- Classifier handshape choice in Russian Sign Language and Sign Language of the Netherlands

- Formal and functional factors in classifier choice: Evidence from American Sign Language and Danish Sign Language

- Choice of handshape and classifier type in placement verbs in American Sign Language

- Somatosensory iconicity: Insights from sighted signers and blind gesturers

- Diachronic changes the Nicaraguan sign language classifier system: Semantic and phonological factors

- Depicting handshapes for animate referents in Swedish Sign Language

- A ministry of (not-so-silly) walks: Investigating classifier handshapes for animate referents in DGS

- Choice of classifier handshape in Catalan Sign Language: A corpus study

- Showing language change: examining depiction in Israeli Sign Language

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- No three productions alike: Lexical variability, situated dynamics, and path dependence in task-based corpora

- Individual differences in event experiences and psychosocial factors as drivers for perceived linguistic change following occupational major life events

- Is GIVE reliable for genealogical relatedness? A case study of extricable etyma of GIVE in Huī Chinese

- Borrowing or code-switching? Single-word English prepositions in Hong Kong Cantonese

- Stress and epenthesis in a Jordanian Arabic dialect: Opacity and Harmonic Serialism

- Can reading habits affect metaphor evaluation? Exploring key relations

- Acoustic properties of fricatives /s/ and /∫/ produced by speakers with apraxia of speech: Preliminary findings from Arabic

- Translation strategies for Arabic stylistic shifts of personal pronouns in Indonesian translation of the Quran

- Colour terms and bilingualism: An experimental study of Russian and Tatar

- Argumentation in recommender dialogue agents (ARDA): An unexpected journey from Pragmatics to conversational agents

- Toward a comprehensive framework for tonal analysis: Yangru tone in Southern Min

- Variation in the formant of ethno-regional varieties in Nigerian English vowels

- Cognitive effects of grammatical gender in L2 acquisition of Spanish: Replicability and reliability of object categorization

- Interaction of the differential object marker pam with other prominence hierarchies in syntax in German Sign Language (DGS)

- Modality in the Albanian language: A corpus-based analysis of administrative discourse

- Theory of ecology of pressures as a tool for classifying language shift in bilingual communities

- BSL signers combine different semiotic strategies to negate clauses

- Embodiment in colloquial Arabic proverbs: A cognitive linguistic perspective

- Voice quality has robust visual associations in English and Japanese speakers

- The cartographic syntax of Lai in Mandarin Chinese

- Rhetorical questions and epistemic stance in an Italian Facebook corpus during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Sentence compression using constituency analysis of sentence structure

- There are people who … existential-attributive constructions and positioning in Spoken Spanish and German

- The prosodic marking of discourse functions: German genau ‘exactly’ between confirming propositions and resuming actions

- Semantic features of case markings in Old English: a comparative analysis with Russian

- The influence of grammatical gender on cognition: the case of German and Farsi

- Phonotactic constraints and learnability: analyzing Dagaare vowel harmony with tier-based strictly local (TSL) grammar

- Translating the Quranic word ‘Al-ðann’ into English

- Special Issue: Request for confirmation sequences across ten languages, edited by Martin Pfeiffer & Katharina König - Part II

- Request for confirmation sequences in Castilian Spanish

- A coding scheme for request for confirmation sequences across languages

- Special Issue: Classifier Handshape Choice in Sign Languages of the World, coordinated by Vadim Kimmelman, Carl Börstell, Pia Simper-Allen, & Giorgia Zorzi

- Classifier handshape choice in Russian Sign Language and Sign Language of the Netherlands

- Formal and functional factors in classifier choice: Evidence from American Sign Language and Danish Sign Language

- Choice of handshape and classifier type in placement verbs in American Sign Language

- Somatosensory iconicity: Insights from sighted signers and blind gesturers

- Diachronic changes the Nicaraguan sign language classifier system: Semantic and phonological factors

- Depicting handshapes for animate referents in Swedish Sign Language

- A ministry of (not-so-silly) walks: Investigating classifier handshapes for animate referents in DGS