The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

-

Hannah Josten

and Friederike Weschenfelder

Abstract

Objectives

This study investigates the relationship between the cerebro-placental ratio (CPR) measured at 40+0 weeks’ gestation and perinatal outcomes to determine a CPR cut-off that may justify induction of labor at term in appropriately grown fetuses (AGA). Although CPR is used for monitoring growth-restricted fetuses, its role in guiding labor induction decisions for AGA pregnancies at term remains unclear.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from 491 singleton pregnancies with intended vaginal deliveries between 2015 and 2021. CPR was assessed at the actual estimated date of delivery (40+0 weeks’ gestation). Adverse pregnancy outcome (APO) as the primary endpoint was defined by admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), umbilical cord blood pH<7.1, 5-min APGAR<7 or interventions-due-to-fetal-distress during labor (IDFD=vaginal-operative delivery or emergency caesarean section).

Results

APO nearly doubled (adjOR 1.7; CI 1.007–2.905) when CPR was below our calculated cut-off of 1.269 (18.4 vs. 32.3 %, p=0.002) and NICU admissions (4.8 vs. 11.1 %, p=0.020) and IDFD (12.5 vs. 21.2 %, p=0.027) significantly increased. The positive predictive value for the presence of APO using our cut-off was 32.4 %, and the negative predictive value 81.6 %.

Conclusions

Our data confirm a predictive value of a reduced CPR at term with impaired perinatal outcome. The cut-off of CPR<1.269 may guide decision-making regarding induction of labor. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

The cerebro-placental ratio (CPR) as the ratio of the middle cerebral artery pulsatility index (MCA PI) and the umbilical artery PI and is a non-invasive way of assessing the intrauterine circulatory conditions of the fetus. A reduced CPR can be attributed either to a reduced resistance of the middle cerebral artery because of fetal brain sparing with relative hypoxemia or to an increasing resistance of the umbilical artery because of increasing placental resistance [1]. Therefore, low CPR values are associated with decreased placental function and adverse perinatal outcome [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. The value of the CPR to diagnose placental insufficiency at term, particularly in uncomplicated pregnancies, is so far unclear.

Previous studies have shown that not only small for gestational age fetuses (SGA) can be affected by impaired fetoplacental perfusion, but also appropriate for gestational age fetuses (AGA), and CPR is helpful in identifying these cases [12], [13], [14].

In a recently published large multicenter study, including pregnancies near term, a significant reduction in neonatal morbidity was achieved by using CPR measurement in addition to standard ultrasound examination to recommend induction of labor at values below the 5th percentile based on Baschat, et al. [15], 16].

Nevertheless, there is no consensus on the extent to which CPR should be included in the decision for or against induction of labor in uncomplicated pregnancies at term with no threshold implemented in current guidelines.

The aim of this study is to investigate the influence of a reduced CPR recorded at the actual estimated date of delivery (EDD) on the immediate perinatal outcome. Additionally, we aimed to determine a threshold value for the CPR justifying induction of labor in uncomplicated pregnancies at term.

Materials and methods

Study design

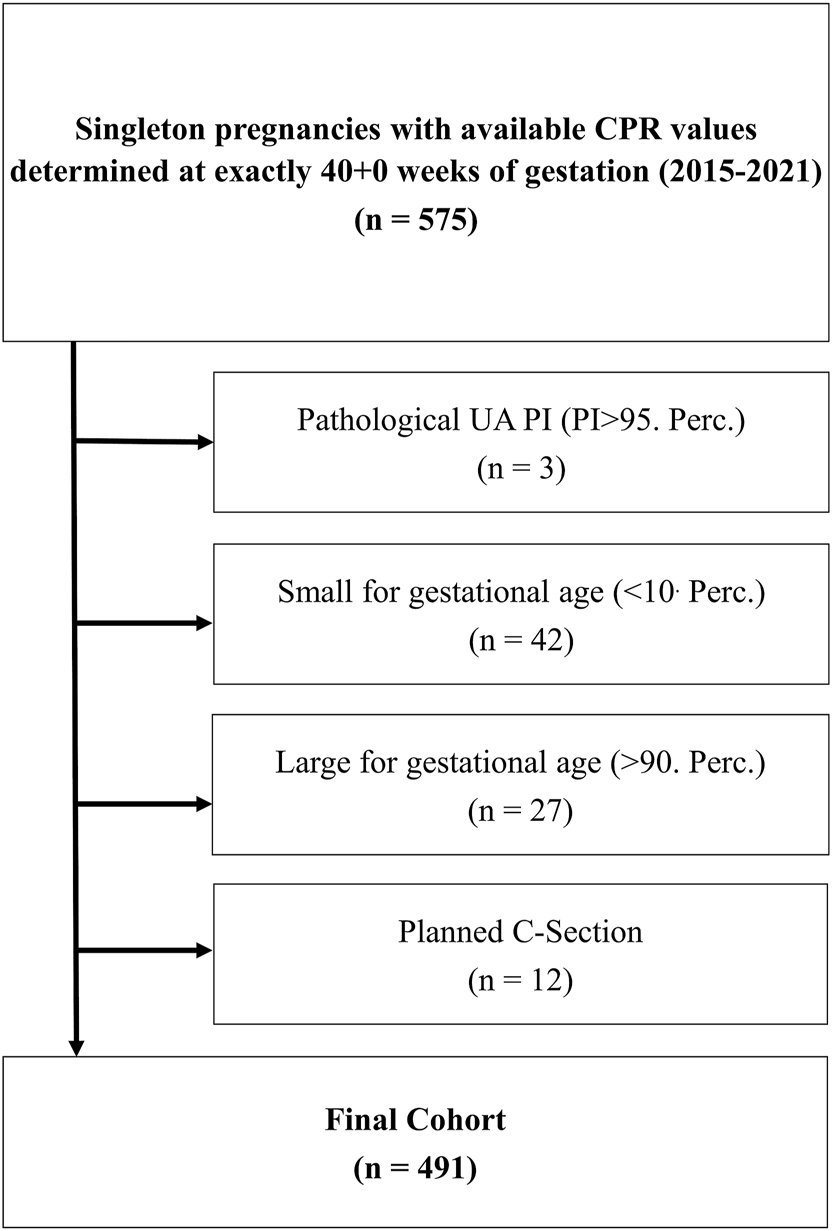

The study we conducted is a retrospective cohort study and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena, Germany (Reg.-Nr. 2022-2678-Daten). The study population (Figure 1) consists of 491 children, born at the Jena University Hospital between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021. The anonymous use of clinical data for research and educational purposes is generally permitted under the governmental regulations of Thuringia, eliminating the need for written consent. Researchers and clinicians are legally authorized to use patient data collected during routine care for scientific and educational presentations, reports, and analyses. The data were accessed for research purposes on July 1, 2022. After this date, the authors no longer had access to any information that could identify individual participants. The ethical approval was obtained in the in the sense of these regulations.

Cohort composition: from a total of n=575 with available cerebro-placental ratios (CPR) at exactly 40+0 weeks of gestation, we were able to finally include n=491 to our final cohort after applying exclusion criteria: planned C-section (n=12), small for gestational age (n=42), umbilical artery pulsatility index >95. Percentile (n=3) and large for gestational age (n=27).

All women with singleton pregnancies who gave birth in our hospital for which CPR was assessed at 40+0 weeks’ gestation (n=575) and for which spontaneous delivery was intended (n=12 with primary caesarean section excluded) were included as consecutive cases. Further exclusion criteria were a pathological umbilical Doppler (umbilical artery PI>95th percentile=1.097 according to Ciobanu et al. (n=3)) as well as expected SGA (n=42) and LGA fetuses (n=27) based on the estimated birth weight (EFD) at 40+0 weeks of gestation using Hadlock’s formula [17], 18]. We used the cut-off defined for the 40th week of pregnancy published by Ciobanu et al. as a comparison to a cut-off determined in our cohort [17].

Data collection

Data were retrieved from the available patient records. Gestational age was determined for all pregnancies based on the measurement of the fetal crown-rump length (CRL) during the first trimester and thus the calculated date of delivery (40+0), which was defined as the inclusion criterion for our cohort. Maternal body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on the height and the documented pre-pregnancy weight. The birth weight was categorized using Voigt’s percentiles [19]. Doppler examination was obtained from 40+0 weeks of gestation according to our clinical guidelines by a constant and trained group of doctors from the Department of Obstetrics at Jena University Hospital using a 2.0–6.0 MHz transabdominal transducer on a GE Voluson E10 (GE Healthcare GmbH, Solingen, Germany). Umbilical artery Doppler were assessed in a free cord loop and MCA Doppler in the proximal third of the origin of the MCA with an angle nearly to zero between direction of blood flow and ultrasound beam according to the current guidelines published by The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology (ISUOG) [20].

Primary outcome

The primary endpoint was adverse pregnancy outcome (APO) defined as one or more of the following criteria: admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), umbilical cord blood pH<7.1, 5-min APGAR score less than 7, obstetric intervention due to fetal distress (IDFD). An IDFD was defined as a need for vaginal-operative delivery or emergency caesarean section due to fetal distress, indicated by non-reassuring heart rate monitoring or in fetal scull blood testing.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. 491 cases were included, which met all inclusion and no exclusion criteria. For categorical data, we applied the Chi2 test or Fisher exact test. As most of the metric data did not have a normal distribution, median and interquartile range were used for data presentation. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed as a non-parametric test for group comparison of the metric data. The significance level was set at α=0.05 (two-sided).

ROC curves (receiver operator characteristic curves) were generated to assess the accuracy of the prediction of APO of the CPR and maternal age. The area under the curve (AUC) with a 95 % confidence interval was used for this purpose.

The cut-offs for CPR and also maternal age in relation to the prediction model was determined using Youden index criteria [21]. Both sensitivity and specificity were determined and used to calculate the positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) for the different CPR cut offs.

Multivariate logistic regression for analyzing the individual effects of the different CPR cut offs, parity, BMI and maternal age on the APO were performed. Adjusted ORs (adjusted for days of gestation at delivery and fetal birth weight) with a 95 % confidence interval (CI) are presented. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance (2-tailed).

Results

Baseline characteristics and perinatal outcome are shown in Table 1. The final study cohort comprised 491 cases.

Baseline and outcome parameters of the entire cohort (n=491) and comparing cases with adverse (n=104) and favorable outcome (n=387).

| Parameter | Entire cohort (n=491) | Adverse perinatal outcome (n=104; 21.2 %) | Favorable outcome (n=387; 78.8 %) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline parameter | Maternal age, years | 31 (28–23) | 32 (30–34.5) | 30 (26–33) | 0.032 |

|

|

|||||

| Parity | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | <0.001 | |

| Nulliparity | 255 (51.9) | 77 (74.0) | 178 (46.0) | <0.001 | |

| Gravidity | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001 | |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 (21.0–27.6) | 23.5 (21.6–27.8) | 23.4 (21.0–27.3) | 0.889 | |

| Obesity, BMI>30 kg/m2 | 71 (14.7) | 15 (14.7) | 56 (14.7) | 0.998 | |

| Smoking | 22 (6.4) | 2 (2.9) | 20 (7.3) | 0.272 | |

| Pre-existing cardiovascular diseases | 29 (5.9) | 7 (6.7) | 22 (5.7) | 0.688 | |

| DM or GDM | 81 (16.5) | 18 (17.3) | 63 (16.3) | 0.802 | |

| Placental insufficiency | 39 (7.9) | 8 (7.7) | 31 (8.0) | 0.915 | |

|

|

|||||

| Ultrasound values at 40+0 | Fetal weight percentile | 41 (25.0–61.5) | 44.0 (28.0–72.5) | 43.0 (24.5–61.0) | 0.472 |

|

|

|||||

| Umbilical PI | 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | 0.76 (0.66–0.88) | 0.76 (0.69–0.86) | 0.469 | |

| ACM PI | 1.28 (1.08–1.49) | 1.16 (1.0–1.47) | 1.23 (1.08–1.45) | 0.072 | |

| CPR | 1.63 (1.33–2.04) | 1.53 (1.21–2.17) | 1.59 (1.35–2.03) | 0.052 | |

| UCR | 0.61 (0.49–0.75) | 0.65 (0.49–0.81) | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) | 0.052 | |

| Uterine mean PI | 0.63 (0.55–0.74) | 0.67 (0.59–0.74) | 0.61 (0.54–0.75) | 0.349 | |

| Oligohydramnion | 13 (2.6) | 2 (1.9) | 11 (2.8) | >0.99 | |

|

|

|||||

| Pregnancy and perinatal outcome | Gestational age at birth, days | 283 (281–287) | 284 (281–289) | 284 (281–288) | 0.525 |

|

|

|||||

| Time interval between Doppler recordings and labor, days | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–8) | 3 (1–7) | 0.812 | |

| Mode of delivery: | |||||

| Spontaneous | 370 (75.4) | 28 (26.9) | 342 (88.4) | <0.001 | |

| Vaginal operative | 42 (8.6) | 34 (32.7) | 8 (2.1) | <0.001 | |

| Emergency C-section | 79 (16.1) | 42 (40.4) | 37 (9.6) | <0.001 | |

| Induction of labor | 279 (56.8) | 65 (62.5) | 214 (55.3) | 0.118 | |

| Gender female | 233 (47.5) | 48 (46.2) | 185 (47.8) | 0.765 | |

| Gender male | 258 (52.5) | 56 (53.8) | 202 (52.2) | 0.765 | |

| Birth weight children, g | 3,545 (3,300–3,815) | 3,480 (3,175–3,754) | 3,560 (3,335–3,835) | 0.013 | |

| SGA at birth (Voigt’s percentiles) | 39 (7.9) | 18 (17.3) | 21 (5.4) | <0.001 | |

| Percentile (voigt) | 44 (23–66) | 38 (16.5–63.5) | 46 (26–67.5) | 0.011 | |

| Umbilical cord pH | 7.22 (7.17–7.28) | 7.16 (7.08–7.24) | 7.22 (7.18–7.27) | <0.001 | |

| Umbilical cord BE | −4.4 (−7.0 to −2.3) | −6.8 (−9.8 to −2.35) | −4.4 (−6.7 to −2.05) | <0.001 | |

| Admission to NICUa | 30 (6.1) | 30 (28.8) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| pH<7.1a | 29 (5.9) | 29 (27.9) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| IDFDa | 70 (14.3) | 70 (67.3) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| APGAR 5<7a | 9 (1.8) | 9 (8.7) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

-

Data are n (%) or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified. Adverse perinatal outcome (APO) was defined as the primary endpoint if at least one of the following criteriaa was met: NICU admission, NApH<7 or interventions-due-to-fetal-distress (IDFD, vaginal delivery or secondary caesarean section). Bold: significant difference between adverse pregnancy outcome and favorable outcome (p<0.05). ACM, arteria cerebri media; CPR, cerebro-placental ratio; DM, diabetes mellitus; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PI, pulsatility index; UCR, umbilicocerebral ratio.

The median time between Doppler recording and delivery was 3 days. 71.3 % of the children were born within one week after Doppler recording (40+0–40+6 weeks of gestation). The mean of recorded CPR values was 1.63 (1.33–2.04). Induction of labor was performed in 56.8 % (n=279). APOs occurred in 21.2 % (n=104) of the cases. 6.1 % (n=30) of the children had to be transferred to NICU, in 14.3 % (n=70) cases an IDFD became necessary. Average gestational age at delivery was 283 days. Women with an adverse outcome were significantly older (32 vs. 30 years, p=0.032) and significantly more likely to be primipara (p<0.001). There were 39 cases of children classified as SGA using the Voigt percentiles postnatally, which were significantly more common in the group with adverse outcomes (17.3 vs. 5.4 %; p<0.001).

CPR values did not differ between the group with APO and the group with favorable outcome (1.53 vs. 1.59, p=0.052). In the descriptive analysis, there were no significant differences concerning any fetal and maternal Doppler parameters including CPR for cases with APO (21.2 %) compared to the ones with favorable outcome (78.8 %) (Table 1).

APO depending on the CPR cut offs

To perform group comparisons between cases with a CPR below a certain threshold and cases within the normal range we used different cut off values. The 10th percentile published by Ciobanu et al. (CPR<1.192), the in clinical routine most commonly used cut-off of a CPR<1.0 and the cut off value we retrieved from the data of this study using statistical analysis (CPR<1.269). The results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Description of the adverse perinatal outcome (n=104) and favorable outcome (n=387) for the various cerebro placental ratios (CPR) cut-offs and maternal age.

| Parameter | Entire cohort (n=491) | Adverse perinatal outcomea (n=104; 21.2 %) | Favorable outcome (n=387; 78.8 %) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-offs | Maternal age>28.5 | 328 (66.8) | 80 (76.9) | 248 (64.1) | 0.014 |

| CPR<1.0 | 11 (2.2) | 4 (3.8) | 7 (1.8) | 0.257 | |

| CPR<1.192 | 69 (14.1) | 23 (22.1) | 46 (11.9) | 0.008 | |

| CPR<1.269 | 99 (20.2) | 32 (30.8) | 67 (17.3) | 0.002 |

-

Bold: significant difference between adverse pregnancy outcome and favorable outcome (p<0.05); CPR, cerebro-placental ratio; aadverse perinatal outcome was defined as the primary endpoint if at least one of the following criteria was met: NICU admission, NApH<7.1 or interventions-due-to-fetal-distress (IDFD, vaginal delivery or secondary caesarean section).

Description and predictive values for adverse perinatal outcome for the different cerebro-placental ratio (CPR) cut-offs.

| Parameter | CPR<1.0 (n=11; 2.2 %) | CPR>1.0 (n=480; 97.8 %) | p-Value | CPR<1.192 (n=69; 14.1 %) | CPR>1.192 (n=422; 85.9 %) | p-Value | CPR<1.269 (n=99; 20.2 %) | CPR>1.269 (n=387; 78.8 %) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APO | 4 (36.4) | 100 (20.8) | 0.257 | 23 (33.3) | 81 (19.2) | 0.008 | 32 (32.3) | 72 (18.4) | 0.002 |

| NICU | 1 (9.1) | 29 (6.0) | 0.504 | 8 (11.6) | 22 (5.2) | 0.054 | 11 (11.1) | 19 (4.8) | 0.020 |

| pH<7.1 | 1 (9.1) | 28 (5.8) | 0.461 | 6 (8.8) | 23 (5.5) | 0.271 | 8 (8.2) | 21 (5.4) | 0.298 |

| IDFD | 3 (27.3) | 67 (14.0) | 0.197 | 17 (24.6) | 53 (12.6) | 0.008 | 21 (21.2) | 49 (12.5) | 0.027 |

| APGAR 5<7 | 0 (0) | 9 (1.9) | >0.99 | 2 (2.9) | 7 (1.7) | 0.362 | 2 (2.0) | 7 (1.8) | >0.99 |

|

|

|||||||||

| Predictive values, % | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Sensitivity | 3.9 | 22.1 | 30.8 | ||||||

| Specificity | 98.2 | 88.1 | 82.7 | ||||||

| PPV | 36.4 | 33.3 | 32.4 | ||||||

| NPV | 79.2 | 80.8 | 81.6 | ||||||

-

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified. Bold: significant if p<0.05; APO, adverse perinatal outcome; CPR, cerebro-placental ratio; IDFD, intervention due to fetal distress; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Comparing the groups with and without APO values below the defined cut off were significantly more frequent in the APO group for the value from Ciobanu et al. (22.1 vs. 11.9 %, p=0.008) and the one retrieved from our data (30.8 vs. 17.3 %, p=0.002), while the cut-off of below 1 did not discriminate the group with APO from the one without (3.8 vs. 1.8 %, p=0.257) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the frequencies of APO in cases with a CPR below the different cut offs. Cases with a CPR<10th percentile according to Ciobanu had significantly more frequent APOs (33.3 vs. 19.2 %, p=0.008) and more IDFDs (24.6 vs. 12.6 %, p=0.008). Cases with a CPR below our cut-off were significantly more likely to have an APO (32.3 vs. 18.4 %, p=0.002), IDFDs (21.2 vs. 12.5 %, p=0.027) and children were significantly more likely to be transferred to NICU (11.1 vs. 4.8 %, p=0.020). There were no significant differences between groups applying a threshold of 1.0. Values for specificity, sensitivity, NPV and PPV are depicted in Table 3.

CPR, age and nulliparity are independent risk factors for APO

Multivariate regression analysis was performed including categorical information on nulliparity, obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2), maternal age cut off >28.5 years and CPR<1.269 adjusted for gestational age at delivery and birth weight (Table 4). Results retrieved a CPR below 1.269 to be a robust risk factor for APO increasing the risk by 1.7-fold (CI: 1.007–2.905).

Multivariate regression for analyzing the individual effects on the combined adverse perinatal outcome.

| Parameter | p-Value | adjORa | CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPR<Cut off (1.269) | 0.047 | 1.711 | 1.007–2.905 |

| Nulliparity | <0.001 | 3.898 | 2.326–6.533 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 0.475 | 1.274 | 0.655–2.476 |

| Age cut off (>28.5 years)b | <0.001 | 2.695 | 1.558–4.663 |

|

|

|||

| CPR<10. Perz. (1.192) | 0.117 | 1.605 | 0.889–2.900 |

| Nulliparity | <0.001 | 3.944 | 2.356–6.603 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 0.495 | 1.260 | 0.649–2.446 |

| Age cut off (>28.5 years)b | <0.001 | 2.732 | 1.582–4.720 |

|

|

|||

| CPR<1 | 0.780 | 1.209 | 0.319–4.584 |

| Nulliparity | <0.001 | 4.072 | 2.438–6.803 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 0.465 | 1.279 | 0.660–2.477 |

| Age cut off (>28.5 years)b | <0.001 | 2.740 | 1.589–4.723 |

-

Adverse perinatal outcome was defined as the primary endpoint if at least one of the following criteria was met: admission to neonatal intensive care unit, NApH<7 or interventions-due-to-fetal-distress (IDFD, vaginal delivery or secondary caesarean section). Bold: significant if p<0.05. aadjOR, adjusted for days of gestation at delivery and fetal birth weight. bAge cut off calculated using Youden Index. BMI, body mass index; CPR, cerebro-placental ratio.

Discussion

Main findings

In this retrospective study of 491 patients with CPR measured directly at term, we were able to establish a CPR cut-off of 1.269 that best discriminated for APO. We demonstrated a significant 1.7-fold increase in the risk of encountering an APO when the CPR measured at term was below our threshold. In contrast the so far applied cut offs for CPR at term both Ciobanu of 1.192 and of just 1 did not reveal to be of robust influence on APO in our multivariate analysis. However, being older than 28.5 years increases the risk for an APO by 2.7-fold and being nulliparous by 4-fold independently (see Table 4).

Comparison to existing literature

The role of antepartum Doppler sonography to identify fetuses at risk for adverse outcomes remains important to detect subclinical placental insufficiency [22]. Fetuses with abnormal antepartum Doppler are supposed to be at higher risk for adverse perinatal outcome [2], [3], [4], [5], [6, 9], 11]. We were able to demonstrate that fetuses with abnormal CPR values at the due date were more likely to experience APOs, including the necessity of an intervention due to fetal distress, admission to NICU and were born with lower birth weights and lower birth weight percentiles (see Table 3 and Supplemental Data).

Like Lu et al. in their prospective study with 384 term pregnancies undergoing induction of labor and the relevance of different clinical parameters prior induction, we were also unable to demonstrate an influence of CPR on fetal blood gas parameters [5]. In contrast, Akolekar et al. were able to demonstrate an association of CPR on blood gas analysis in a rather large cohort of 6,178 singleton pregnancies where CPR was measured at 35–37 weeks’ gestation [23]. The fact that we did not see a significant effect on the 5-min APGAR and the umbilical cord pH can possibly be explained by the fact that our study was a retrospective study and the decision to intervene in the delivery was made early enough to prevent the child from being compromised. However, in comparison to the national perinatal data base (Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen, IQTIG) the rate of fetal acidosis (Umbilical artery pH<7.1) and admission rate to NICU were markedly higher in out cohort (5.9 vs. 2.3 % for acidosis and 6.1 vs. 3.5 % for NICU admission) [24]. This demonstrates, that the rate of fetal compromises might be generally higher in a post due date cohort like the one analysed in our study.

In the multivariate analysis, a significant increase in risk was only found for the threshold value we established on the basis of our study. However, our sample is only suitable for validating this threshold value to a limited extent as it was calculated on this very sample. The value should therefore be tested on a different population to confirm its validity. In contrast to El-Sayed et al. and Ciobanu et al., we were unable to demonstrate a significant influence of maternal BMI on the occurrence of APO or CPR in our multivariate analysis [17], 25].

Our calculated value for gestational age of 280 days (1.269) falls between the values calculated by Ciobanu et al. for the time points of 276 days (1.275) and 283 days (1.192). According to Ciobanu et al. we were able to demonstrate a correlation between nulliparity, increased maternal age and low CPR.

The poor predictive value of CPR for an adverse outcome (we calculated sensitivity 30.8 %, specificity 82.7 %, PPV 32.36 %, NPV 81.64 %) was also shown in other studies [2], [3], [4, 13], [26], [27], [28]. Fiolna et al. reported a sensitivity of 35 % and a specificity of 80 % for the CPR<10th percentile. The sensitivity is thus slightly higher and the specificity slightly lower compared to our cut-off. Fiolna et al. also included LGA fetuses into their study, which have an increased risk for APO compared to AGA fetuses. The higher incidence of APO might have increased the sensitivity in this study sample. Furthermore, while we included all patients admitted for spontaneous delivery, they included only pregnant women with a scheduled induction [2] which might have impaired the incidence of APO in the study sample further. Ortiz et al. also found a sensitivity of only 19 % and a specificity of 84 % for the prediction of an APO for CPR below the 10th percentile, whereby in their study the IDFD represented a separate endpoint for which CPR performed better with a sensitivity of 26 % and a specificity of 87 % [13]. In our study, however, IDFD was a component of the adverse outcome, which is a possible reason the different sensitivity and specificity determined for APO. All studies suggest that using CPR alone as a screening method for adverse outcomes lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity. Fiolna et al. suggested that maternal and pregnancy characteristics, along with the course of labor, may play a more significant role than prenatal fetal oxygenation in the development of fetal stress and associated adverse neonatal outcomes [2].

Strength and limitations

A strength of our study is the measurement of the CPR on the exact estimated date of delivery and the substantial size of the cohort (n=491). Including maternal comorbidities like preexisting cardiovascular diseases or diabetes to establish a cut-off that is broadly applicable can be considered both a strength and also a limitation of our study. Thus, the cut-off is more universally applicable to a broader patient population but can also be significantly altered negatively by a possible higher risk of complications. Weaknesses of our study include primarily verifying the threshold value within the same cohort used for its calculation. To validate our cut-off, it should undergo testing on an independent cohort. By exclusively including cases examined at the EDD (40+0 weeks of gestation), we hoped to improve the predictive power of the calculated value, as CPR fluctuating normal values during pregnancy. Another possible source of bias in our study may be the 39 cases (7.9 %) that were incorrectly classified as AGA by ultrasound. These were also more frequently represented in the group with adverse outcome. This point once again illustrates the relevance but also the over- and underestimation of EFW, especially in SGA but also LGA fetuses, as shown by Dittkrist et al. [29].

Implications

Due to the rather poor discrimination qualities (NPV of our threshold for an APO of 81 %), CPR seems insufficient as a single criterion for a decision in favor of and especially against induction of labor. Nevertheless, fetuses with a CPR below this value were significantly more likely to have an APO, an IDFD and admission to NICU, so it can certainly be assumed that a CPR<1.269 represents a risk factor and could therefore be useful as a supplementary criterion especially in the shared decision-making process with patients at the time of EDD. The extent to which this is weighted should be the aim of further studies.

In a different attempt using Doppler sonographic assessment to predict fetal outcome uterine blood flow at an early stage of labor was determined and showed an independent association of increased mean UtA PI (Uterine Artery PI) with IDFDs and adverse perinatal outcome was shown. However, in this study as well PPV and NPV to predict APO were low (PPV of 0.18 (95 % CI, 0.07–0.33) and NPV of 0.94 (95 % CI, 0.92–0.95)) [22].

Supporting physiological birth is currently becoming more and more important in obstetrics. The ARRIVE study was performed to evaluate the value of induction of labor near term, aiming to reduce the rate of induced labor. The results of the ARRIVE study, showed that elective induction after 39 weeks’ gestation did indeed not improve the composite adverse perinatal outcome. However, fewer maternal interventions such as caesarean sections (18.6 vs. 22.2 %; relative risk (RR), 0.84; 95 % CI, 0.76 to 0.93) and assisted vaginal deliveries (7.3 vs. 8.5 %; RR 0.85; 95 % CI, 0.72–1.01) were necessary in the induction group compared to the expectant-management group [30]. In addition the RATIO37 study with a prospective design and over 9.000 cases included showed that elective labor based on a CPR<5th percentile in addition to estimated fetal weight (EFW) significantly reduced severe neonatal morbidity such as renal or cardiac failure and NICU admission >10 days compared to single use of EFW [15]. Both prospective studies demonstrate, that early term induction even regardless of CPR determination improved neonatal outcome, thus supporting our result, that induction of labor at term in cases with impaired CPR might lead to improved neonatal outcome. However, to prove this conclusion prospective designed studies are mandatory. If we apply the results of the ARRIVE and RATIO37 studies to our data, patients at the EDD who reach the CPR cut-off should be offered elective induction to maybe reduce interventions sub partu and enable them to experience an uncomplicated vaginal delivery.

Conclusions

Predictive qualities for APOs were low for any CPR cut-offs tested but specificity was high. Both the 10th percentile according to Ciobanu et al. and the CPR threshold value determined by us (CPR<1.269) showed a good negative predictive value, but a poor positive predictive value. For the CPR cut-off determined in our study cohort of 491 cases, there was a sensitivity of 30.8 %, a specificity of 82.7 %, a PPV of 32.3 % and an NPV of 81.6 % for the presence of an APO. The frequency of IDFDs nearly doubled regardless of the CPR cut-offs used. However, due to the retrospective design, we were unable to answer the question of whether induction of labor in cases where a certain CPR cut off is hidden induction of labor would decrease the rate of APO, especially IDFDs. However, we showed that a decreasing trend in CPR is an important factor in assessing fetal well-being at term and should be considered in obstetric counseling and decision-making, particularly when aiming for a low-intervention, physiological birth.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the obstetric team for their support and contribution to data collection.

-

Research ethics: This is an observational study. The Study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena, Germany (Reg.-Nr. 2022-2678-Daten, date of approval 28.06.2022).

-

Informed consent: No consent was required for the use of recorded data in research purpose since the protocol for this research project has been approved by the local Ethics Committee.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Project development, Material preparation and data collection were performed by YH, HJ, FW and TG. HJ, FW and TL performed the numerical calculations. TL verified the analytical methods. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HJ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback, helped shaping the research and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Baschat, AA, Gembruch, U, Reiss, I, Gortner, L, Weiner, CP, Harman, CR. Relationship between arterial and venous Doppler and perinatal outcome in fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000;16:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00284.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Fiolna, M, Kostiv, V, Anthoulakis, C, Akolekar, R, Nicolaides, KH. Prediction of adverse perinatal outcome by cerebroplacental ratio in women undergoing induction of labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:473–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20173.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Moreta, D, Vo, S, Eslick, GD, Benzie, R. Re-evaluating the role of cerebroplacental ratio in predicting adverse perinatal outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;242:17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.06.033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Akolekar, R, Ciobanu, A, Zingler, E, Syngelaki, A, Nicolaides, KH. Routine assessment of cerebroplacental ratio at 35–37 weeks’ gestation in the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:65 e1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Lu, J, Jiang, J, Zhou, Y, Chen, Q. Prediction of non-reassuring fetal status and umbilical artery acidosis by the maternal characteristic and ultrasound prior to induction of labor. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:489. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03972-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Mecke, L, Ignatov, A, Redlich, A. The importance of the cerebroplacental ratio for the prognosis of neonatal outcome in AGA fetuses. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2023;307:311–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06596-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Prior, T, Paramasivam, G, Bennett, P, Kumar, S. Are fetuses that fail to achieve their growth potential at increased risk of intrapartum compromise? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:460–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14758.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Vollgraff Heidweiller-Schreurs, CA, De Boer, MA, Heymans, MW, Schoonmade, LJ, Bossuyt, PMM, Mol, BWJ, et al.. Prognostic accuracy of cerebroplacental ratio and middle cerebral artery Doppler for adverse perinatal outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:313–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.18809.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Günay, T, Bilir, RA, Hocaoğlu, M, Bör, ED, Özdamar, Ö, Turgut, A. The role of abnormal cerebroplacental ratio in predicting adverse fetal outcome in pregnancies with scheduled induction of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021;153:287–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13469.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ismail, A, Ibrahim, AL, Rabiu, A, Muhammad, Z, Garba, I. Predictive value of Doppler cerebroplacental ratio for adverse perinatal outcomes in postdate pregnancies in Northwestern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2022;25:406–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_14_21.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Dunn, L, Sherrell, H, Kumar, S. Review: systematic review of the utility of the fetal cerebroplacental ratio measured at term for the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Placenta 2017;54:68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2017.02.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. DeVore, GR. The importance of the cerebroplacental ratio in the evaluation of fetal well-being in SGA and AGA fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Ortiz, JU, Graupner, O, Flechsenhar, S, Karge, A, Ostermayer, E, Abel, K, et al.. Prognostic value of cerebroplacental ratio in appropriate-for-gestational-age fetuses before induction of labor in late-term pregnancies. Ultraschall Med 2023;44:50–5. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1399-8915.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Morales-Rosello, J, Khalil, A, Morlando, M, Papageorghiou, A, Bhide, A, Thilaganathan, B. Changes in fetal Doppler indices as a marker of failure to reach growth potential at term. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;43:303–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13319.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Rial-Crestelo, M, Lubusky, M, Parra-Cordero, M, Krofta, L, Kajdy, A, Zohav, E, et al.. Term planned delivery based on fetal growth assessment with or without the cerebroplacental ratio in low-risk pregnancies (RATIO37): an international, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2024;403:545–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)02228-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Baschat, AA, Gembruch, U. The cerebroplacental Doppler ratio revisited. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003;21:124–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Ciobanu, A, Wright, A, Syngelaki, A, Wright, D, Akolekar, R, Nicolaides, KH. Fetal Medicine Foundation reference ranges for umbilical artery and middle cerebral artery pulsatility index and cerebroplacental ratio. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:465–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hadlock, FP, Harrist, RB, Sharman, RS, Deter, RL, Park, SK. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements – a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;151:333–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(85)90298-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Voigt, M, Fusch, C, Olbertz, D, Hartmann, K, Rochow, N, Renken, C, et al.. Analysis of the neonatal collective in the Federal Republic of Germany 12th report. Presentation of detailed percentiles for the body measurement of newborns. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2006;66:956–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-924458.Search in Google Scholar

20. Khalil, A, Sotiriadis, A, D’Antonio, F, Da Silva Costa, F, Odibo, A, Prefumo, F, et al.. ISUOG practice guidelines: performance of third-trimester obstetric ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2024;63:131–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.27538.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Youden, WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3:32–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3.10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3Search in Google Scholar

22. Dall’asta, A, Figueras, F, Rizzo, G, Ramirez Zegarra, R, Morganelli, G, Giannone, M, et al.. Uterine artery Doppler in early labor and perinatal outcome in low-risk term pregnancy: prospective multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2023;62:219–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.26199.Search in Google Scholar

23. Akolekar, R, Syngelaki, A, Gallo, DM, Poon, LC, Nicolaides, KH. Umbilical and fetal middle cerebral artery Doppler at 35–37 weeks’ gestation in the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14842.Search in Google Scholar

24. IQTIG. Bundesauswertung zum Erfassungsjahr 2021 – Geburtshilfe – Qualitätsindikatoren und Kennzahlen; 2022. Available from: https://iqtig.org/downloads/auswertung/2021/pmgebh/DeQS_PM-GEBH_2021_BUAW_V01_2022-06-30.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

25. El-Sayed, YY, Rice, MM, Grobman, WA, Reddy, UM, Tita, ATN, Silver, RM, et al.. Elective labor induction at 39 weeks of gestation compared with expectant management: factors associated with adverse outcomes in low-risk nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:692–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000004055.Search in Google Scholar

26. Dall’Asta, A, Ghi, T, Rizzo, G, Cancemi, A, Aloisio, F, Arduini, D, et al.. Cerebroplacental ratio assessment in early labor in uncomplicated term pregnancy and prediction of adverse perinatal outcome: prospective multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:481–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.19113.Search in Google Scholar

27. Buca, D, Rizzo, G, Gustapane, S, Mappa, I, Leombroni, M, Bascietto, F, et al.. Diagnostic accuracy of Doppler ultrasound in predicting perinatal outcome in appropriate for gestational age fetuses: a prospective study. Ultraschall Med 2021;42:404–10. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1072-5161.Search in Google Scholar

28. Martin-Alonso, R, Rolle, V, Akolekar, R, de Paco Matallana, C, Fernandez-Buhigas, I, Sanchez-Camps, MI, et al.. Efficiency of the cerebroplacental ratio in identifying high-risk late-term pregnancies. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091670.Search in Google Scholar

29. Dittkrist, L, Vetterlein, J, Henrich, W, Ramsauer, B, Schlembach, D, Abou-Dakn, M, et al.. Percent error of ultrasound examination to estimate fetal weight at term in different categories of birth weight with focus on maternal diabetes and obesity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22:241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04519-z.Search in Google Scholar

30. Grobman, WA, Rice, MM, Reddy, UM, Tita, ATN, Silver, RM, Mallett, G, et al.. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med 2018;379:513–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1800566.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2024-0427).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)