Abstract

Introduction

Prematurely born males compared to females have greater respiratory morbidiy in childhood, but differences in adolescents and young adults are less clear.

Content

A systematic review was undertaken to determine if there were sex differences in the lung function of prematurely born or very low birth weight born adolescents and adults

Summary

Seven of 1969 studies were included (766 infants). Three found no significant differences, but did not give raw lung function data. Four studies reported lung function data by sex. One found no significant differences and another only reported results for females, which were not lower than the controls. Another found males compared to females aged 16–19 years had lung function z scores indicating a more obstructive pattern [p<0.05]. The males, however, had significantly better exercise tolerance. The fourth reported worse lung function only in preterm born adult males.

Outlook

Male compared to female individuals born prematurely had worse lung function in adulthood, but only in two of seven studies, both reported results from patients born in the era of routine surfactant use. Further research is required to more robustly determine the effect of sex on lung function in adults born prematurely.

Introduction

Individuals who are born very prematurely or with very low birth weight do not reach the full lung growth potential of their term or normal birthweight counterparts [1]. Lung function is further impaired in infants who had bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [2]. In those adults with reduced lung growth, the natural decline in lung function seen in all adults, therefore, leads to a higher likelihood of them developing obstructive lung disease in adulthood such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [3].

There are known structural differences in the lungs between males and females at the time of birth, which is hypothesised to be partially due to androgen receptors in the fetal lung [4]. One animal model demonstrated that exposure of androgen receptors to dihydrotestosterone affects early lung morphogenesis leading to a higher rate of branching morphogenesis and cell proliferation. This leads to a higher number of terminal lung buds but delays the growth arrest required for terminal epithelial differentiation and therefore delays lung maturation [5]. As a result male infants reach surfactant maturity on average 1.4 weeks later than female infants [6]. They have a higher incidence of respiratory distress syndrome [6] and worse respiratory outcomes in infancy [7], 8], including an increased severity of BPD [9] and a higher mortality [10]. In childhood they have an increased incidence of inhaler use and asthma and have more readmissions for respiratory infections [8], 11], 12]. The differences following puberty and adolescence are less clear, with some studies reporting worse respiratory outcomes for males [13], 14], but others highlighting a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms in women [15]. During puberty there is greater thoracic growth in males which may reduce obstructive airway disease. We, therefore, hypothesised that adult lung function would differ between the sexes in those born prematurely or with very low birth weight. A systematic review was undertaken with the primary outcome being sex differences in lung function following preterm birth.

Methodology of the systematic review

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) recommendations, a systematic literature search was undertaken with two databases: PubMed and Embase. The databases were searched from their beginning (1996 and 1947 respectively) until 1st May 2024. The search terms included (respiratory function or lung function or spirometry) and (preterm or low birthweight) and (adult or adolescence). Additionally, manual review of the bibliography of key articles which fulfilled the eligibility criteria and review articles was carried out.

Studies were included if they involved preterm individuals (that is those born at less than 37 weeks of gestational age) or had a birthweight less than 1,500 g. The individuals must have had lung function testing after the age of 16 years and the studies included details or description of lung function by sex. The following types of articles were excluded: duplicates, letters, reviews, editorials, meeting abstracts and commentaries. The study protocol (Long-Term Respiratory Morbidity in Very Low Birth Weight Infants born in the Surfactant Era – A Systematic Review) was registered on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42024510179).

Two authors independently screened all studies, looking at titles, abstracts and full text reviews. They applied the inclusion criteria and assessed methodological quality. If there were discrepancies a third reviewer was called upon. Data extraction was carried out by one person and checked by a second for each study. This included citation information, location of the research, language of the publication, time period of the study, study objective, design of the study, gestational age, birth weight, age at lung function testing, lung function parameters, inclusion and exclusion criteria and the study results.

None of the studies were randomised and all were cohort studies, hence the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [16] was used to assess methodological quality. The NOS scores three areas of a study: selection of the sample (0–4), comparability between the groups (0–2) and outcomes (0–3). This gave a total of nine points. Studies scoring a minimum of six points [1], [2], [3] were classified as good quality, studies scoring a minimum of five points [1], 2] were of fair quality and those with a score less than that were classified as of poor quality.

Quality of the studies

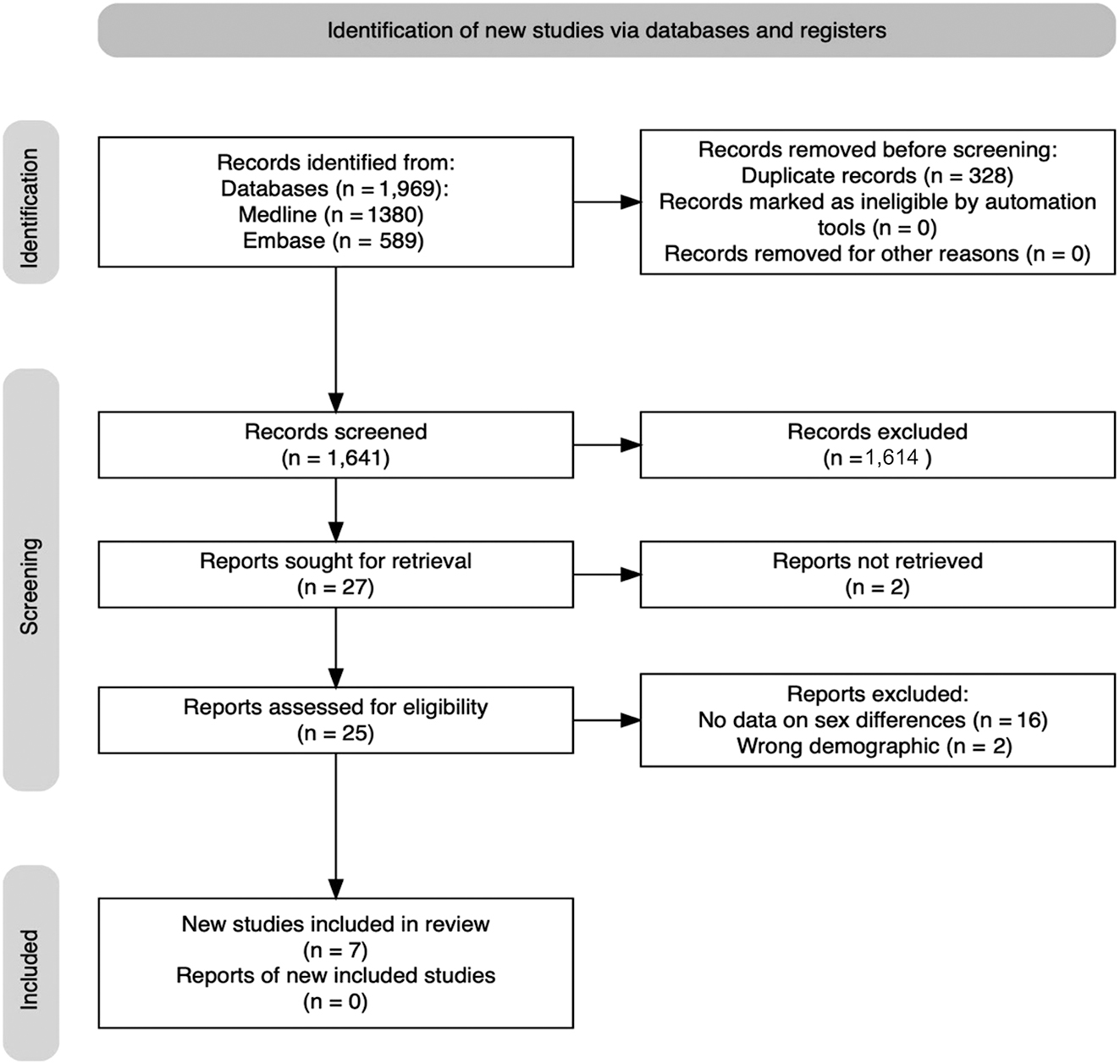

Of the 1969 potentially relevant studies, only seven met the inclusion criteria: [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. The PRISMA flow diagram of the search process is shown in Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale scores ranged from six to nine for the seven studies (Appendix Table A1). Points were lost for the non-representativeness of exposed cohorts, failure to select a non-exposed cohort and inadequacy of follow up. Please see Appendix A for full results.

The included studies evaluated 766 individuals born prematurely or with very low birth weight who had lung function testing as adults. All of the studies were prospective cohort studies (Table 1).

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Name | Country | Sample size | Mean GA, weeks | Mean BW | Inclusion criteria | Surfactant | Numeric sex data or description of lung function findings by sex | Age at follow up, mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doyle et al. [17] | Australia | 147 preterm 37 NBW controls |

With BPD 26.8 Without BPD 29.3 |

909 g 1150 g |

VLBW born between 1977–1982 and had LFT >18 years | No | Description | 18.9 years |

| Duke et al. [20] | USA | 13 preterm 14 controls |

27.8 | 1080 g | 18–31 years born at <32 weeks | No | Description | 20 years |

| Saarenpää et al. [21] | Finland | 166 VLBW 172 controls |

27.9–29.5 | 1126 g | Helsinki Study of VLBW adults. Born between 1978–1985 + <1500 g | Yes but only 4 % received surfactant | Regression co-efficient (male to female) Z score | 21.7–22.5 years |

| Vollsæter et al. [23] | Norway | 45 preterm 39 controls |

27.4 | 1006 g | <28 weeks or <1,000 g born in 1982–1985 in Norway | No | Description | First at 18 years and then at 25 years |

| Kaczmarczyk et al. [22] | Poland | Total 12 | 34.5 standard deviation (1.92) | NA | <37 week, <2,500 g, registered in premature infant group and had lung function testing in 1997, 1998 and 2015 | Unclear | Lung function Z score, females only | 28.08 years |

| Harris et al. [19] | UK | Total 150 | 26.9 | F=882 g M=925 g |

United Kingdom Oscillation study (UKOS) participants (23–28 + 6 weeks requiring intubation + intensive care at birth) | Yes – 97 % received surfactant | Lung function Z scores | 18 years |

| Lundberg et al. [18] | Sweden | 110 preterm 1,895 term controls |

35.1 39.6 |

2592 g 3505 g |

Infants born between 32–37 weeks between 1994–1996 in Stockholm and who attended for lung function testing at 16–24 years. | Yes | Regression co-efficient (term to preterm) Z score | 22.7 years |

Lung function results

Four studies reported differences in lung function data by sex for preterm or low birth weight born adults [18], 19], 21], 22]. Unfortunately, the results were reported differently: lung function z-scores, regression coefficients comparing males to females and regression coefficients comparing preterm males to term males. One study reported lung function z scores but only for females [22]. As a result, it was not possible to perform a metanalysis of the results of the four studies.

Harris et al. [19] found that preterm born adolescent males had reduced lung function compared to females (Table 2).

Lung function by sex, demonstrated as z scores.

| Lung function | Males mean, SD | Females mean, SD | Z score mean adjusted difference (M–F) (95 % [CI]) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEF75 | −1.42 (1.25) | −0.63 (1.16) | −0.60 [−0.97, −0.24] | 0.001 |

| FEF50 | −1.23 (0.98) | −0.74 (1.09) | −0.39 [−0.72, −0.07] | 0.017 |

| FEF25–75 | −1.86 (1.25) | −1.08 (1.20) | −0.62 [−0.98, −0.26] | 0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | −1.55 (1.15) | −0.75 (1.15) | −0.71 [−1.09, −0.34] | <0.001 |

| DLCO | −1.20 (1.05) | −0.83 (1.11) | −0.41 [−0.78, −0.03] | 0.033 |

| DLCO/VA | −2.36 (0.86) | −1.82 (0.87) | −0.57 [−0.86, −0.28] |

-

FEFn %, forced expiratory flow at n % of the vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; DLco, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; VA, alveolar volume. Data are presented as median (IQR) or mean (±standard deviation) (%) or mean difference (95 % CI).

Exercise capacity was significantly better in males than females. Males were able to complete a greater distance during a shuttle sprint test and reported a greater amount of weekly exercise (Table 3).

Exercise outcomes by sex.

| Exercise distance test p<0.001 | Self-reported exercise p=0.016 |

|---|---|

| <100 m: 19 % males vs. 60 % females 1,000–1,249 m: 35 % males vs. 35 % females 1,250–1.500 m: 46 % males vs. 4.8 % females |

None: 26 % males vs. 32 % females Up to 1 h/day: 45 % males vs. 55 % females >1 h/day: 29 % males vs. 12 % females |

Lundberg et al. [18]also reported a sex difference in lung function at adulthood for prematurely born individuals. When comparing preterm born males to term born males they found significantly worse lung function in two parameters (Table 4), but there were no significant differences in the females. They did not compare preterm born males to preterm born females.

Lung function by sex, reported as coefficient change in mean for preterm compared to term.

| Lung function | Adjusted coefficient change in mean (preterm male to term males (95 % [CI])) | p-Value | Adjusted coefficient change in mean (preterm femaleto term females (95 % [CI])) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 | −0.28 [−0.56, −0.01] | 0.05 | 0.04 [−0.18, 0.26] | 0.72 |

| FVC | −0.05 [−0.33, 0.23] | 0.72 | 0.10 [−0.12, 0.32] | 0.36 |

| FEV1/FVC | −0.38 [−0.67, −0.09] | 0.01 | −0.11 [−0.34, −0.13] | 0.37 |

-

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; data are presented as median (IQR).

Additionally, they compared lung function results in adulthood to those of the participants when they were 16 years old. There was an improvement in FEV1 with an increase in the Z-score of 0.18 (0.04–0.32), p=0.01, but only in the females.

Saarenpää et al. [21] used multiple regression and showed that the lung function results were affected by several factors including smoking and obstructive airway disease, but not by sex. The regression coefficients comparing the differences between preterm born adult males and females for FVC [0.16 (−0.17 to 0.49) p=0.34], FEV1 [0.19 (−0.16 to 0.54) p=0.29], FEV1/FVC [-0.04 (0.41–0.34) p=0.85], FEF75 [0.22 (−0.08 to 0.52) p=0.15], FEF25–75 [0.19 (−0.16 to 0.54) p=0.29] revealed that the effect of sex was not significant.

The fourth paper [22] had no male participants. Female preterm born adults were compared to a reference group of term born females, no significant differences were found.

Three of the seven studies referred to sex differences in lung function scores, but did not provide data. Doyle et al. [17] reported that the FEV1/FVC ratio was not significantly affected by sex. Duke et al. [20] described a significant difference between sexes in the following raw lung function results: forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced mid expiratory flow (FEF25-50), slow vital capacity (SVC), inspiratory capacity (IC), expiratory reserve volume (ERV), functional residual capacity (FRC), residual volume (RV), total lung capacity (TLC) and pulmonary diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Once, however, the values were converted into percentage predicted values, which took sex into account, there were no significant differences. Vollsæter et al. [23] measured lung function at 18 and 25 years of age. They reported no significant sex effect in the extremely preterm participants, but did not provide data. They commented that in term born controls, the FEV1/FVC ratio (p=0.024) and FRC (p=0.041) between 18 and 25 years was significantly lower in males compared to females.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that there is insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions about the effect of sex on adult lung function in prematurely born individuals. Whilst four studies demonstrated no difference in lung function in adulthood between the sexes, two large studies by Harris et al. [19] and Lundberg et al. [18] found significant differences between the sexes. Both Harris and Lundberg reported lung function results consistent with obstructive airway disease and found significant reductions in the FEV1/FVC, but no significant difference in FVC. Additionally, Harris et al. [19] reported a lower FEF75 in the males suggesting sex might also affect small airway function. An explanation for the differences in lung function could be that, although there is increased thoracic growth in males through puberty compared to females, there might be an element of acquired dysanapsis. Incongruity between the airway diameter and lung size with smaller airways than would be expected for the size of lung parenchyma would lead to higher resistance [24], 25]. As a result, there would be a lower FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio but no reduction in FVC. This discordance between lung parenchyma and airway size is thought to be affected by sex in the non-preterm born population [26]. If there is existing airflow obstruction, there could be subsequent parenchymal hyperinflation and further dysanapsis described as an ‘acute on chronic’ effect [25].

Harris et al. [19] described no significant difference in reported respiratory symptoms between preterm born adolescent males and females, despite a higher proportion of males having obstructive lung results. Additionally, Harris et al. found that males had better exercise capacity. This is perhaps due to physical fitness being determined by a variety of factors including muscle mass [27] and cardiovascular fitness [28], in addition to lung function.

Brostrom et al. [29] assessed infants born at less than 35 weeks of gestation or with a birth weight of less than 2,000 g for females and 2,100 g for males compared to control infants born between 1925 and 1949. They found in preterm born or low birth weight born females as birth weight and gestational age decreased, there was an increasing risk of obstructive airway disease (asthma and COPD) in adulthood. This association was not found in males. This might suggest that the sex effect on respiratory outcomes continues to change throughout adult life.

The differences in sex-related differences in lung fuction between studies could be explained by surfactant administration. The two studies which reported differences by sex in adult lung function included patients born in the era during which surfactant was routinely used. Harris et al. [19] reported 97 % of their study participants had received surfactant. Lundberg did not specify the percentage of participants who received surfactant, but refers to the study period as the ‘post-surfactant era’. The remaining studies [17], 20], 21], 23], aside from Kaczmarczyk et al. [22] where it is not clearly stated, included individuals born prior to routine surfactant administration. Given the small number of studies available for inclusion in this review, it cannot be determined whether surfactant administration plays a role in the sex differences in lung function.

There are strengths and some limitations to this review. This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, that has looked at sex differences in preterm or low birth weight born adolescents and adults. The search criteria for this review were wide, so we are confident that all relevant papers were screened. The limitations include the inability to conduct a metanalysis due to lack of lung function data presented in a consistent form. This emphasises the importance of consistent reporting in scientific literature. We would recommend the use of z-scores (age-adjusted scoring) for all lung function tests reported in the future. We were unsuccessful in obtaining raw data from the authors, meaning that statistical comparisons could not be made between studies. Additionally, there were only two studies reporting cohorts in the post-surfactant era. Surfactant is known to affect lung function but whether it has an additional sex specific effect could not be assessed.

Conclusions

Male born preterm individuals were reported to have worse lung function at adulthood, but only in two of seven studies. Further research is needed to provide robust data regarding the effect of sex on adulthood lung function.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: EJ conducted the literature search, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AJ conceptualised project, conducted the literature search, reviewed the manuscript. OS contributed to literature search and review of manuscript. GP contributed to conceptualisation, literature search, review of manuscript. TD conceptualised the project and reviewed the manuscript. AG conceptualised the project and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Data is available upon reasonible request.

Newcastle ottowa scale.

| Cohot | Total score | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Selection of Cohorts | Comparability of cohorts | Outcome | ||||||

| Representativeness of exposed cohorts | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome not present at start | On the basis of design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow up long enough for outcome to occur | Adequacy of follow up | ||

| Doyle [17] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Duke [20] | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7 | ||

| Harris [19] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Kaczmarczyk [22] | * | * | ** | * | * | 6 | |||

| Lundberg [18] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Saarenpää [21] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

| Vollsæter [23] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9 |

-

The file shared had this table populated by asterisk. Each asterisk signifies the outcome, as expressed in the column heading, is present. As the 6th column refers to two outcomes (design OR analysis) there are two asterisks to signify both are present. The asterisks add up to the final value in the final column.

References

1. Kotecha, SJ, Edwards, MO, Watkins, WJ, Henderson, AJ, Paranjothy, S, Dunstan, FD, et al.. Effect of preterm birth on later FEV1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2013;68:760–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203079.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Gibson, AM, Reddington, C, McBride, L, Callanan, C, Robertson, C, Doyle, LW. Lung function in adult survivors of very low birth weight, with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015;50:987–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23093.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Doyle, LW, Andersson, S, Bush, A, Cheong, JLY, Clemm, H, Evensen, KAI, et al.. Expiratory airflow in late adolescence and early adulthood in individuals born very preterm or with very low birthweight compared with controls born at term or with normal birthweight: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:677–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30530-7.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Kimura, Y, Suzuki, T, Kaneko, C, Darnel, AD, Akahira, J, Ebina, M, et al.. Expression of androgen receptor and 5alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 in early gestation fetal lung: a possible correlation with branching morphogenesis. Clin Sci 2003;105:709–13. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20030236.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Levesque, BM, Vosatka, RJ, Nielsen, HC. Dihydrotestosterone stimulates branching morphogenesis, cell proliferation, and programmed cell death in mouse embryonic lung explants. Pediatr Res 2000;47:481–91. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200004000-00012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Fleisher, B, Kulovich, MV, Hallman, M, Gluck, L. Lung profile: sex differences in normal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1985;66:327–30.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Ito, M, Tamura, M, Namba, F. Role of sex in morbidity and mortality of very premature neonates. Pediatr Int 2017;59:898–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13320.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Peacock, JL, Marston, L, Marlow, N, Calvert, SA, Greenough, A. Neonatal and infant outcome in boys and girls born very prematurely. Pediatr Res 2012;71:305–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2011.50.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Zysman-Colman, Z, Tremblay, GM, Bandeali, S, Landry, JS. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia - trends over three decades. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/18.2.86.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Townsel, CD, Emmer, SF, Campbell, WA, Hussain, N. Gender differences in respiratory morbidity and mortality of preterm neonates. Front Pediatr 2017;5:6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2017.00006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Elisabeth, R, Elke, G, Vera, N, Maria, G, Michaela, H, Ursula, KK. Readmission of preterm infants less than 32 Weeks gestation into early childhood: does gender difference still play a role? Glob Pediatr Health 2014;1:2333794x14549621. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794x14549621.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Grischkan, J, Storfer-Isser, A, Rosen, CL, Larkin, EK, Kirchner, HL, South, A, et al.. Variation in childhood asthma among former preterm infants. J Pediatr 2004;144:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.029.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Kotecha, SJ, Lowe, J, Kotecha, S. Does the sex of the preterm baby affect respiratory outcomes? Breathe 2018;14:100–7. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.017218.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. He, B, Kwok, MK, Au Yeung, SL, Lin, SL, Leung, JYY, Hui, LL, et al.. Birth weight and prematurity with lung function at ∼17.5 years: “Children of 1997” birth cohort. Sci Rep 2020;10:341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56086-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Vrijlandt, EJ, Gerritsen, J, Boezen, HM, Duiverman, EJ. Gender differences in respiratory symptoms in 19-year-old adults born preterm. Respir Res 2005;6:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-6-117.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Wells, GA, Shea, B, O'Connell, D, Peterson, J, Welch, V, Losos, M, et al.. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. [cited 2024 14th October]. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Doyle, LW, Faber, B, Callanan, C, Freezer, N, Ford, GW, Davis, NM. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight subjects and lung function in late adolescence. Pediatrics 2006;118:108–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2522.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Lundberg, B, Merid, SK, Um-Bergström, P, Wang, G, Bergström, A, Ekström, S, et al.. Lung function in young adulthood in relation to moderate-to-late preterm birth. ERJ Open Res 2024;10. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00701-2023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Harris, C, Lunt, A, Peacock, J, Greenough, A. Lung function at 16-19 years in males and females born very prematurely. Pediatr Pulmonol 2023;58:2035–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.26428.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Duke, JW, Elliott, JE, Laurie, SS, Beasley, KM, Mangum, TS, Hawn, JA, et al.. Pulmonary gas exchange efficiency during exercise breathing normoxic and hypoxic gas in adults born very preterm with low diffusion capacity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;117:473–81. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00307.2014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Saarenpää, HK, Tikanmäki, M, Sipola-Leppänen, M, Hovi, P, Wehkalampi, K, Siltanen, M, et al.. Lung function in very low birth weight adults. Pediatrics 2015;136:642–50. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2651.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Kaczmarczyk, K, Wiszomirska, I, Szturmowicz, M, Magiera, A, Błażkiewicz, M. Are preterm-born survivors at risk of long-term respiratory disease? Ther Adv Respir Dis 2017;11:277–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753465817710595.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Vollsæter, M, Clemm, HH, Satrell, E, Eide, GE, Røksund, OD, Markestad, T, et al.. Adult respiratory outcomes of extreme preterm birth. A regional cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:313–22. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201406-285oc.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Green, M, Mead, J, Turner, JM. Variability of maximum expiratory flow-volume curves. J Appl Physiol 1974;37:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1974.37.1.67.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. McGinn, EA, Mandell, EW, Smith, BJ, Duke, JW, Bush, A, Abman, SH. Dysanapsis as a determinant of lung function in development and disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;208:956–63. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202306-1120pp.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Sheel, AW, Dominelli, PB, Molgat-Seon, Y. Revisiting dysanapsis: sex-based differences in airways and the mechanics of breathing during exercise. Exp Physiol 2016;101:213–8. https://doi.org/10.1113/ep085366.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Perez-Gomez, J, Rodriguez, GV, Ara, I, Olmedillas, H, Chavarren, J, González-Henriquez, JJ, et al.. Role of muscle mass on sprint performance: gender differences? Eur J Appl Physiol 2008;102:685–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-007-0648-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Zeiher, J, Ombrellaro, KJ, Perumal, N, Keil, T, Mensink, GBM, Finger, JD. Correlates and determinants of cardiorespiratory fitness in adults: a systematic review. Sports Med Open 2019;5:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0211-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Broström, EB, Akre, O, Katz-Salamon, M, Jaraj, D, Kaijser, M. Obstructive pulmonary disease in old age among individuals born preterm. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9761-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)